Abstract

Aims

To assess the relations of menthol cigarette use with measures of cessation success in a large comparative effectiveness trial (CET).

Design

Participants were randomized to one of six medication treatment conditions in a randomized double-blind, placebo controlled clinical trial. All participants received six individual counseling sessions.

Setting

Community-based smokers in two communities in Wisconsin, USA.

Participants

1504 adult smokers who smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day during the past 6 months and reported being motivated to quit smoking. The analysis sample comprised 1439 participants: 814 White non-menthol smokers, 439 White menthol smokers, and 186 African American (AA) menthol smokers. There were too few AA non-menthol smokers (n=16) to be included in the analyses.

Interventions

Nicotine lozenge, nicotine patch, bupropion sustained release, nicotine patch + nicotine lozenge, bupropion + nicotine lozenge, and placebo.

Measurements

Biochemically-confirmed 7-day point-prevalence abstinence assessed at 4, 8, and 26 weeks post-quit.

Findings

In longitudinal abstinence analyses (generalized estimating equations) controlling for cessation treatment, menthol-smoking was associated with reduced likelihood of smoking cessation success relative to non-menthol smoking (model-based estimates of abstinence = 31% vs. 38%, respectively; odds ratio [OR] =0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.59, 0.86). In addition, amongst menthol smokers, AA women were at especially high risk of cessation failure relative to White women (estimated abstinence =17% vs. 35%, respectively; OR=2.63, 95% CI=1.75, 3.96); estimated abstinence rates for AA males and White males were both 30%, OR=1.06, 95% CI=0.60, 1.66).

Conclusion

In the USA, smoking menthol cigarettes appears to be associated with reduced cessation success compared with non-menthol smoking, especially in African-American females.

Introduction

While it is clear that tobacco is addictive and harmful in almost any form [1–3], it is possible that some forms, such as menthol flavored cigarettes, pose heightened risk. Determining the health effects of menthol flavored cigarettes (i.e., menthol-smoking) is important because about 83% of the 5.5 million adult African-American (AA) smokers and about 24% of the 37 million adult White smokers in the US primarily or exclusively smoke menthol cigarettes [4]. The issue of menthol-smoking is timely because the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (H.R. 1256, 111th Congress) gave the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) the authority to regulate tobacco and targeted menthol-smoking for evaluation. Thus, relevant data could have regulatory implications.

Under the 2009 Act, the FDA charged the Tobacco Products Safety Advisory Committee (TPSAC) with evaluating the impact of menthol-smoking on public health. In a March, 2011 report [5], TPSAC concluded that menthol and non-menthol cigarettes produce similarly high rates of morbidity and mortality but that menthol smokers have a more difficult time quitting than do non-menthol smokers, a conclusion that is fairly consistent with other recent reviews [6,7]. The TPSAC reviewed three types of studies to evaluate the relation of menthol-smoking with cessation likelihood: cross-sectional population surveys, longitudinal cohort studies (e.g., community tobacco intervention studies and epidemiological studies of health effects), and cessation clinical trials. They gave greatest weight to the longitudinal studies because participants in such studies are more likely to be representative of the general smoking population. While the longitudinal studies yielded some evidence that menthol-smoking was associated with reduced cessation, the evidence from cessation trials was quite mixed.

Several studies cited in the TPSAC report found no consistent differences in 6-month cessation rates as a function of menthol-smoking [8–10]. However, a few studies reported associations between menthol-smoking and lower 6-month abstinence rates, but the nature of such relations varied across studies [11–14]. For example, in one study, the effect occurred only in smokers provided nicotine replacement therapy (NRT; versus placebo) [13]. Similarly mixed results are reported in menthol-related clinical trials published after the 2011 TPSAC report [15–17]. In sum, menthol effects are inconsistently found in clinical trials, and when found, they are often nested within different populations (e.g., within African-Americans).

Perhaps cessation trials have yielded inconsistent results regarding menthol-smoking because researchers often did not use sensitive indices of cessation (e.g., longitudinal abstinence trajectories) [18]. Further, some studies may have been underpowered to detect menthol effects, especially for within-race contrasts. The present research investigated the relations between menthol-smoking and cessation outcomes in secondary analyses of a large comparative effectiveness trial (CET) [19] by: (a) relating menthol-smoking to longitudinal cessation outcomes; (2) evaluating whether 3rd variables might account for observed relations; (3) determining whether there are subpopulations of smokers for whom menthol-smoking is especially associated with poor cessation outcomes; and (4) determining how cessation pharmacotherapy affects relations between menthol-smoking and cessation outcomes.

Methods

Data Source

Data are from the longitudinal Wisconsin Smokers Health Study (WSHS) conducted at the University of Wisconsin Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention (UW-CTRI) and funded by the National Institutes of Health. This research generated a 2005 evaluation of the safety and efficacy of five smoking cessation pharmacotherapies and placebo [19]. Study procedures were approved by the University of Wisconsin Health Sciences IRB.

A total of 1504 smokers (58.2% female; 16.1% non-White minorities) were randomly assigned to receive either nicotine lozenge (N=260), nicotine patch (N=262), bupropion SR (N=264), nicotine patch plus nicotine lozenge (N=267), bupropion SR plus nicotine lozenge (N=262), or placebo (N=189). All participants received six individual counseling sessions (10–20 minutes each). Exclusion criteria included contraindications for any study medication (see [19]). Results showed that all of the active pharmacotherapies yielded higher biochemically-confirmed abstinence rates than did placebo, and with combination NRT being superior to any monotherapy (p’s < .05) [19].

Analysis Sample

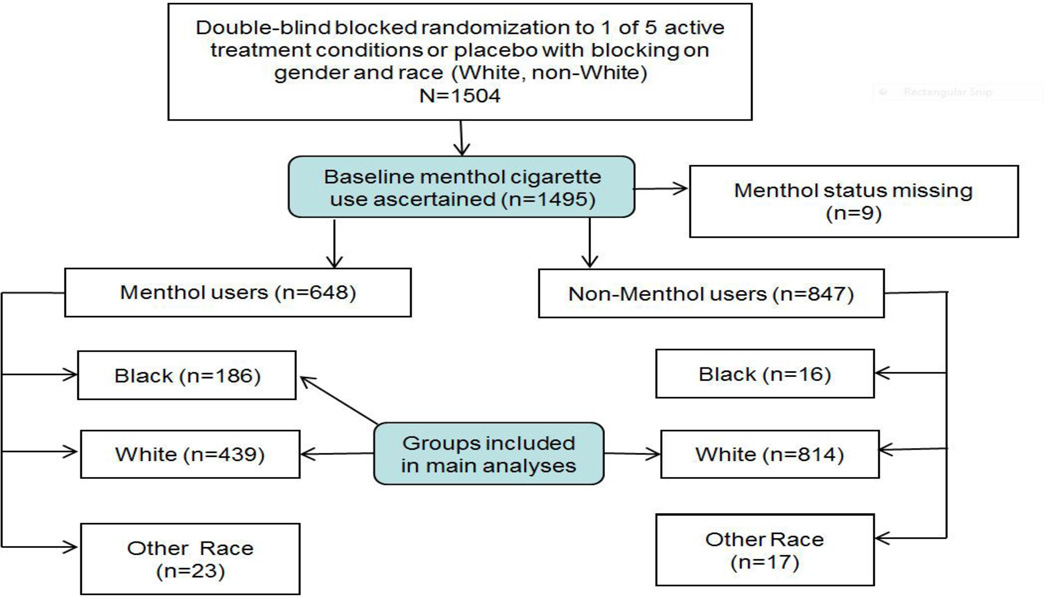

As shown in Figure 1, our analysis sample comprised 1439 participants: 814 White non-menthol smokers, 439 White menthol smokers, and 186 AA menthol smokers. The analysis sample excludes non-White/non-AA (i.e., Other Race) participants because these groups were deemed too small to permit meaningful analysis.

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram for WSHS-1 Menthol-Related Secondary Analyses.

Selected WSHS-1 CET Assessments at Baseline, Intra-treatment, and Follow-up

Participants completed questionnaires during baseline that assessed sociodemographic variables (age, race, etc.) and history of tobacco use. Use of menthol cigarettes was assessed with the baseline question, “Do you smoke menthol cigarettes?” (yes, no). At baseline and post-quit visits, participants completed exhaled-breath carbon monoxide (CO) testing with values < 10 ppm confirming self-reported abstinence. Smoking- and cessation-related data were collected at in-person visits at Weeks 4 (intra-treatment), 8 (end of treatment), and 26 (follow-up). Daily self-reported smoking status was also gathered via the timeline follow-back method [20,21].

Primary Outcome Measure

The primary outcome, which constituted the dependent variable in the longitudinal models, was CO-confirmed 7-day point-prevalence abstinence (PPA) at Weeks 4, 8, and 26 post-quit, observing the intent-to-treat principle (i.e., analyses included all participants in the analysis sample who were randomized to treatment).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical tests were two-tailed with alpha =.05. All analyses were computed using SAS/STAT software, Version 9.3 of the SAS System for Windows, SAS Institute Inc. (Cary, NC). Initial analyses using t-tests and Chi-Square tests (for continuous and categorical variables, respectively) examined baseline differences in sociodemographic and smoking-related variables as a function of menthol-smoking status (non-menthol smokers vs. menthol smokers).

Primary abstinence outcome analyses modeled the effects of menthol status and other covariates on PPA at Weeks 4, 8, and 26 in longitudinal analyses using generalized linear models (GLMs). We used longitudinal models to analyze outcomes comprehensively across the three outcome time points, including effects that change reliably over time (i.e., group by time interactions). Two GLMs were used: (1) marginal or “population average” models that permit inferences about the effects of covariates on population and sub-population means via generalized estimating equations (GEE); and (2) conditional models or “subject-specific” models that permit inferences about an individual’s mean response as a function of within-individual changes in covariates via generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) [22–24]. These GLMs differ in assumptions (e.g., about the source of the correlation amongst the repeated outcomes) and yield somewhat different model parameters resulting from marginal and conditional models (e.g., different odds ratios [ORs] with binary outcomes). Because there is no consensus about which model is optimal for clinical trials [e.g., 25,26], we adopted a strategy of first computing GEE marginal models (using SAS PROC GENMOD) to test the statistical significance of model effects and to generate ORs (and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]). We then computed parallel GLMM conditional models (using SAS PROC GLIMMIX) to compare statistical significance in the two models. For both sets of models, we specified a logit link function and an unstructured covariance matrix to model the correlations amongst the three correlated outcomes [22]. For GLMM models, we specified adaptive quadrature with 50 quadrature points as the method of estimation; only the intercept was specified as a random effect.

Data Analysis Plan

Our longitudinal models involved testing two menthol status and race comparisons with additional covariates such as gender added in successive models. In the first comparison, White Non-Menthol smokers (coded as 0) were contrasted with AA Menthol and White Menthol smokers (combined and coded as 1; designated NMvsM). This comparison tested the menthol effect in all available AA and White participants, albeit the comparison is confounded with race. The second comparison (AAMvsWM) constrasted AA Menthol smokers (coded as 0) versus White Menthol smokers (coded as 1) and, thus, tested for race differences amongst menthol smokers. White Non-Menthol smokers were not included in this comparison.

Additional tests examined moderation of menthol-smoking effects in the above models. In particular, we tested the main and interactive effects of gender and treatment with NMvsM and AAMvsWM. Treatment was coded as a dichotomous variable consisting of placebo (coded as 0) versus active treatments (coded as 1); Breslow-Day tests [27] confirmed homogeneity of ORs of the five treatments (each relative to placebo) supporting the use of a dichotomous treatment variable. We also conducted sensitivity analyses in which we added a set of empirically and theoretically-derived “sensitivity analysis covariates” to the main analysis models to test the robustness of significant menthol effects. These covariates are reliably related to smoking cessation likelihood [28] and include years of education, and three smoking-related variables: Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND) [29] total score, any home resident smoking (0=no, 1=yes); and proportion of smokers in the participant’s social network. A logistic regression analysis that simultaneously tested all four covariates showed that all four significantly predicted 6-month abstinence. Lastly, we repeated all analyses with study site (2 sites) as a covariate; the inclusion of site had little effect on the pattern of results except for Model 3 in Table 5 (discussed in the Results section).

Table 5.

Comparison of White Non-Menthol versus African American+White Menthol (NMvsM): Longitudinal Models of Biochemically-confirmed 7-Day Point-Prevalence Abstinence Rates at Weeks 4, 8, and 26 (N=1439)

| Model | Model Effects | p-value | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

Model-Based Estimated Probability of Abstinence (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMvsM1 | Cessation Treatment | ||||||

| Non-Menthol | Menthol | Placebo | Active | ||||

| 1 | NMvsM1 | .0005 | 0.72 (0.60,0.87) | .45 (.42, .48) |

.37 (.34, .40) |

- | - |

| Time | <.0001 | - | |||||

| NMvsM × Time | .6065 | - | |||||

| 2 | NMvsM | .0003 | 0.71 (0.59, 0.86) | .38 (.34, .42) |

.31 (.27, .35) |

.27 (.21, .33) |

.43 (.41, .45) |

| Time | <.0001 | - | |||||

| Treatment | <.0001 | 2.06 (1.52, 2.79) | |||||

| 3 | NMvsM | .0236 | 0.80 (0.66, 0.97) | .37 (.33, .41) |

.33 (.28, .37) |

.27 (.22, .34) |

.43 (.41, .46) |

| Time | <.0001 | - | |||||

| Treatment | <.0001 | 2.01 (1.48, 2.73) | |||||

| Education | .0002 | - | |||||

| FTND2 | <.0001 | - | |||||

| Living with Smoker3 | .0340 | - | |||||

| Friends Smoking4 | .0110 | - | |||||

White Non-Menthol versus African American+White Menthol;

Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence [29];

Other smokers present in participant’s home; used as indicator of environmental exposure to smoking;

Proportion of smokers in the participant’s social network: 1=none, 2=less than half, 3=about half, 4=more than half, and 5=all.

Results

Baseline Sociodemographic and Smoking-Related Characteristics by Menthol Status

As shown in Table 1, menthol status was associated with demographic differences including race, gender, education, and work status. In addition, in comparison with non-menthol smokers, menthol smokers smoked fewer cigarettes per day, reported fewer pack-years of smoking, and were more motivated to quit smoking. However, menthol smokers also reported higher levels of nicotine dependence (via the FTND), fewer prior quit attempts, and less confidence in being able to quit smoking successfully.

Table 1.

Baseline Sociodemographic Characteristics and Smoking-Related Measures by Menthol-Smoking Groups (N=1439)

| Participant Characteristics | Non-Menthol Cigarette Smokers (N=814) |

Menthol Cigarette Smokers (N=625) |

Group Differences: Test Value (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, % (N) | 51.4% (418) | 68.6% (429) | χ2 (df=1)=43.6 (p<.0001) |

| Race, % (Columns add to 100%) | |||

| • African American (N) | 0.0% (0) | 29.8% (186) | χ2 (df=1)=278.2 |

| • White (N) | 100.0% (814) | 70.2% (439) | (p<.0001) |

| Hispanic, % (N) | 1.1% (9) | 2.4% (15) | χ2 (df=1)=3.6 (p=.0574) |

| Age (years), Mean (SD) | 44.9 (11.5) | 44.4 (10.6) | t(df=1434)=0.93 (p=.3542) |

| Education, % (Columns add to 100%) | |||

| • < High School (N) | 3.4% (28) | 7.6% (47) | χ2 (df=2)=31.4 |

| • High School (N) | 19.7% (160) | 28.5% (177) | (p<.0001) |

| • >High School (N) | 76.9% (625) | 63.9% (397) | |

| Marital Status, % (Columns add to 100%) | |||

| • Married/With Partner (N) | 57.0% (463) | 50.9% (318) | χ2 (df=2)=5.9 |

| • Divorced/Separated/Widowed (N) | 26.3% (214) | 28.5% (178) | (p=.0514) |

| • Never Married (N) | 16.7% (136) | 20.6% (129) | |

| Employment, % (Columns add to 100%) | |||

| • Student/Homemaker/Retired/Disabled (N) | 15.8% (128) | 16.2 (101) | χ2 (df=2)=10.4 (p=.0056) |

| • Working for Wages/Self-Employed (N) | 80.2% (651) | 75.8% (474) | |

| • Out of Work (N) | 4.1% (33) | 8.0% (50) | |

| Cigarettes Smoked Per Day, Mean (SD) | 22.0 (9.3) | 20.8 (8.3) | t(df=1437)=2.53 (p=.0116) |

| Years of Smoking, Mean (SD) | 26.5 (11.7) | 25.9 (10.7) | t(df=1436)=0.94 (p=.3459) |

| Pack-Years of Smoking, Mean (SD) | 30.7 (21.5) | 27.8 (18.4) | t(df=1436)=2.72 (p=.0066) |

| Age at First Cigarette, Mean (SD) | 14.5 (3.6) | 14.6 (4.1) | t(df=1437)= −0.49 (p=.6233) |

| Exhaled Carbon Monoxide (parts per million), Mean (SD) | 26.3 (12.6) | 25.2 (12.0) | t(df=1412)=1.75 (p=.0802) |

| FTND1 Score, Mean (SD) | 5.3 (2.2) | 5.5 (2.1) | t(df=1437)= −2.10 (p=.0357) |

| Number of Previous Quit Attempts, Mean (SD) | 6.1 (9.1) | 4.9 (8.9) | t(df=1432)=2.44 (p=.0150) |

| Motivation to Quit Smoking,2 Mean (SD) | 9.0 (1.1) | 9.2 (1.1) | t(df=1437)=2.66 (p=.0079) |

| Likelihood of Success in Quitting Smoking,3 Mean (SD) | 5.7 (1.3) | 5.5 (1.5) | t(df=1437)=2.90 (p=.0037) |

FTND=Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence [28];

Based on question, “How motivated are you to stop smoking at this time?” rated on 0–10 response scale with 0=”Not at all motivated” and 10=”Extremely motivated”;

Based on question, “If you try to quit smoking within the next 30 days, how likely is it that you will be successful?” rated on 0–7 response scale with 0=”Not at all likely” and 7=”Very likely”.

Baseline Sociodemographic and Smoking-Related Characteristics by Race for Menthol Smokers

As shown in Table 2, AA menthol smokers differed from White menthol smokers in having less education, being less likely to be married or with a partner, being more likely to be unemployed, and having higher motivation to quit. AA menthol smokers also reported somewhat less severe smoking profiles: e.g., smoking fewer cigarettes per day, having lower CO values.

Table 2.

Baseline Sociodemographic Characteristics and Smoking-Related Measures by Race for Menthol Smokers (N= 625)

| Participant Characteristics | African-American Menthol Cigarette Smokers (N=186) |

White Menthol Cigarette Smokers (N=439) |

Group Differences: Test Value (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, % (N) | 65.1% (121) | 70.2% (308) | χ2 (df=1)=1.6 (p=.2084) |

| Hispanic, % (N) | 2.7% (5) | 2.3% (10) | χ2 (df=1)=0.1 (p=.7593) |

| Age (years), Mean (SD) | 45.8 (8.6) | 43.7 (11.2) | t(df=622)=−2.2 (p=.0281) |

| Education, % (Columns add to 100%) | |||

| • < High School (N) | 16.3% (30) | 3.9% (17) | χ2 (df=2)=29.7 |

| • High School (N) | 28.8% (53) | 28.4% (124) | (p<.0001) |

| • >High School (N) | 54.9% (101) | 67.7% (296) | |

| Marital Status, % (Columns add to 100%) | |||

| • Married/With Partner (N) | 35.0% (65) | 57.6% (253) | χ2 (df=2)=27.1 (p=<.0001) |

| • Divorced/Separated/Widowed (N) | 38.7% (72) | 24.2% (106) | |

| • Never Married (N) | 26.3% (49) | 18.2% (80) | |

| Employment, % (Columns add to 100%) | |||

| • Student/Homemaker/Retired/Disabled (N) | 25.8% (48) | 12.1% (53) | χ2 (df=2)=28.4 (p<.0001) |

| • Working for Wages/Self-Employed (N) | 61.8% (115) | 81.8% (359) | |

| • Out of Work (N) | 12.4% (23) | 6.1% 27) | |

| Cigarettes Smoked Per Day, Mean (SD) | 18.7 (7.6) | 21.7 (8.5) | t(df=623)=4.25 (p<.0001) |

| Years of Smoking, Mean (SD) | 26.3 (10.2) | 25.8 (10.9) | t(df=622)=−0.57 (p=.5713) |

| Pack-Years of Smoking, Mean (SD) | 25.3 (16.1) | 28.8 (19.2) | t(df=622)=2.19 (p=.0287) |

| Age at First Cigarette, Mean (SD) | 15.7 (4.9) | 14.1 (3.6) | t(df=623)= −4.47 (p<.0001) |

| Exhaled Carbon Monoxide (parts per million), Mean (SD) | 21.2 (9.3) | 26.7 (12.6) | t(df=610=5.44 (p<.0001) |

| FTND1 Score, Mean (SD) | 5.5 (2.0) | 5.5 (2.1) | t(df=623)=0.42 (p=.6742) |

| Number of Previous Quit Attempts, Mean (SD) | 4.0 (4.1) | 5.3 (10.3) | t(df=620.02)=2.31 (p=.0215)4 |

| Motivation to Quit Smoking,2 Mean (SD) | 9.4 (1.1) | 9.1 (1.0) | t(df=623)=−3.54 (p=.0004) |

| Likelihood of Success in Quitting Smoking,3 Mean (SD) | 5.3 (1.7) | 5.6 (1.3) | t(df=623)=1.73 (p=.0850) |

FTND=Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence [28];

Based on question, “How motivated are you to stop smoking at this time?” rated on 0–10 response scale with 0=”Not at all motivated” and 10=”Extremely motivated”;

Based on question, “If you try to quit smoking within the next 30 days, how likely is it that you will be successful?” rated on 0–7 response scale with 0=”Not at all likely” and 7=”Very likely”.

Based on Satterthwaite approximation for degrees of freedom due to unequal variances.

Abstinence Rates by Menthol Status

Table 3 presents unadjusted biochemically-confirmed 7-day PPA rates for the three key endpoints (i.e., 4, 8, and 26 weeks) by menthol status and treatment condition in the analysis sample of 1439 participants. Table 4 presents unadjusted biochemically-confirmed 7-day PPA rates for the three key endpoints by menthol status and gender in the analysis sample.

Table 3.

Unadjusted Biochemically-confirmed 7-Day Point-Prevalence Abstinence Rates at Weeks 4, 8, and 26 by Treatment Condition and Menthol Status (N=1439)

| Treatment Condition |

Week 4 | Week 8 | Week 26 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Menthol Smokers1 |

Menthol Smokers2 |

Non-Menthol Smokers1 |

Menthol Smokers2 |

Non-Menthol Smokers1 |

Menthol Smokers2 |

|

| Total Sample | 51.4% | 42.7% | 47.9% | 38.9% | 35.9% | 29.9% |

| Placebo | 34.9% | 25.7% | 34.0% | 24.3% | 24.5% | 20.3% |

| Bupropion | 47.4% | 41.4% | 43.0% | 37.9% | 34.1% | 31.0% |

| Nicotine Lozenge | 46.8% | 30.1% | 45.3% | 32.7% | 38.1% | 27.4% |

| Nicotine Patch | 55.9% | 47.2% | 49.7% | 37.7% | 36.6% | 30.2% |

| Bupropion + Lozenge | 59.0% | 53.6% | 53.2% | 49.1% | 35.3% | 32.7% |

| Patch + Lozenge | 59.3% | 53.8% | 58.0% | 47.2% | 43.3% | 34.9% |

| All Active Treatments | 53.8% | 45.0% | 50.0% | 40.8% | 37.6% | 31.2% |

| Monotherapy Treatments3 | 50.1% | 39.4% | 46.1% | 36.1% | 36.3% | 29.6% |

| Combination Therapies4 | 59.2% | 53.7% | 55.7% | 48.2% | 39.5% | 33.8% |

N=814;

N=625;

Bupropion only, Nicotine Lozenge only, and Nicotine Patch only;

Bupropion + Nicotine Lozenge and Nicotine Patch + Nicotine Lozenge

Table 4.

Unadjusted Biochemically-confirmed 7-Day Point-Prevalence Abstinence Rates at Weeks 4, 8, and 26 by Menthol Status/Race Groups and Gender (N=1439)

| CO-Confirmed 7-Day Point-Prevalence Abstinence Rates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Non-Menthol Smokers | White Menthol Smokers | African American Menthol Smokers |

||

| Females | ||||

| 4 Weeks | 211/418=50.5% | 152/308=49.7% | 33/121=27.3% | |

| 8 Weeks | 195/418=46.7% | 139/308=45.1% | 26/121=21.5% | |

| 26 Weeks | 134/418=32.1% | 103/308=33.4% | 23/121=19.0% | |

| Males | ||||

| 4 Weeks | 207/396=52.3% | 53/131=40.5% | 28/65=43.1% | |

| 8 Weeks | 195/396=49.2% | 54/131=41.2% | 24/65=36.9% | |

| 26 Weeks | 158/396=39.9% | 40/131=30.5% | 21/65=32.3% | |

Longitudinal Analyses

Table 5 presents selected results from a set of longitudinal GEE models that tested the effect of menthol status (NMvsM; non-menthol vs. menthol) on PPA. The first model (Model 1) included menthol status, time (4, 8, 26 weeks), and the interaction between NMvsM and time. Both NMvsM and time were statistically significant (p’s < .001); the interaction was not significant (p=.6065) and was omitted from subsequent models. This analysis showed that menthol-smoking was associated with significantly lower abstinence rates across the three follow-up endpoints. Table 5 also shows the OR and corresponding 95%CIs for the menthol status effect (NMvsM): OR=0.72 (0.60, 0.87) and the model-based estimated probability of abstinence for the menthol status groups (i.e., 45% vs. 37% for non-menthol and menthol smokers, respectively).

The next model (Model 2 in Table 5) added cessation treatment (placebo vs. active) to the first model and revealed that, despite a significant treatment effect, the menthol NMvsM effect remained significant (p=.0003; OR=0.71, [0.59, .86]). We tested an additional model in which we added the interaction between menthol status and treatment to Model 2; this interaction effect was non-significant and was not retained in subsequent models. We also added gender to Model 2 as a main effect and as an interaction with menthol status; neither effect was significant and gender was not retained in subsequent models.

The next model (Model 3 in Table 5) added the four sensitivity analysis covariates (Education, FTND, Living with a Smoker, Proportion of Friends Smoking) to Model 2 in order to test the robustness of the menthol status effect. The addition of these covariates reduced the magnitude of the NMvsM effect as reflected in an attenuated OR of 0.80 (0.66, 0.97) and reduced the difference in estimated abstinence probabilities (37% vs 32%), but the effect of menthol status remained significant (p=.0236).* As noted in the Data Analysis Plan section above, we repeated all analyses with study site (2 sites) as a covariate. The inclusion of site did not change the pattern of results in Models 1 or 2. However, when site was included as an additional covariate in Model 3, the NMvsM effect decreased modestly, becoming non-significant (p=.0987).

We repeated all of the models above in GLMMs and obtained the same pattern of effects. Thus, these NMvsM analyses suggest that menthol use is associated with reduced likelihood of abstinence over the first six months of a cessation attempt, and this effect is fairly robust with regards to the modeling of relevant covariates.

Because the first contrast (NMvsM) confounded race with menthol effects, a second set of longitudinal analyses was run that tested abstinence outcomes amongst AA and White Menthol smokers (AAMvsWM). The first model run with this contrast (Model 1 in Table 6) tested AAMvsWM, time, and the AAMvsWM by time interaction; results showed a significant AAMvsWM main effect [p=.0001; OR=0.55(0.40, 0.75)] and a significant time effect (p<.0001) but no interaction between AAMvsWM and time (p=.1733; omitted in subsequent models). We then tested a second model (Model 2 in Table 6) that added cessation treatment. Results for Model 2 showed a significant treatment effect (p=.0011); the AAMvsWM main effect remained statistically significant (p< .0001). We also tested an additional model in which we added the interaction between AAMvsWM and treatment to Model 2; this interaction effect was non-significant and was not retained in subsequent models..

Table 6.

Comparison of African American Menthol versus White Menthol (AAMvsWM): Longitudinal Models of Biochemically-confirmed 7-Day Point-Prevalence Abstinence Rates at Weeks 4, 8, and 26 (N=625)

| Model | Model Effects | p-value | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

Model-Based Estimated Probability of Abstinence (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAMvsWM1 | Cessation Treatment | ||||||

| African American Menthol |

White Menthol |

Placebo | Active | ||||

| 1 | AAMvsWM1 | .0001 | 0.55 (0.40,0.75) | .28 (.23, .33) |

.41 (.37, .45) |

- | - |

| Time | <.0001 | - | |||||

| AAMvsWM × Time | .1773 | - | |||||

| 2 | AAMvsWM | .0001 | 0.54 (0.39, 0.74) | .22 (.16, .28) |

.34 (.28, .40) |

.20 (.13, .29) |

.36 (.32, .40) |

| Time | <.0001 | - | |||||

| Treatment | .0011 | 2.21 (1.37, 3.50) | |||||

| 3 | AAMvsWM | .0039 | 0.62 (0.45, 0.86) | .23 (.17, .30) |

.33 (.27, .39) |

- | - |

| Time | <.0001 | - | - | - | |||

| Treatment | .0011 | 2.22 (1.34, 3.67) | - | - | .20 (.14, .29) |

.36 (.32, .40) |

|

| Gender | .1358 | - | - | - | |||

| AAMvsWM × Gender | .0048 | - | - | - | |||

| Simple Effects: | |||||||

| AAMvsWM for Females | <.0001 | 2.63 (1.75, 3.96) | .17 (.12, .24) |

.35 (.29, .42) |

- - |

- - |

|

| AAMvsWM for Males | .9927 | 1.06 (0.60, 1.66) | .30 (.21, .41) |

.30 (.23, .38) |

- - |

- - |

|

| 4 | AAMvsWM | .0114 | 0.64 (0.46, 0.90) | .24 (.18, .32) |

.34 (.28, .40) |

- | - |

| Time | <.0001 | - | - | - | |||

| Treatment | .0041 | 2.05 (1.23, 3.42) | - | - | .22 (.15, .32) |

.37 (.33, .41) |

|

| Gender | .0907 | - | - | - | |||

| AAMvsWM × Gender | .0051 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Education | .1323 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| FTND2 | .0168 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Living with Smoker3 | .5672 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Friends Smoking4 | .0692 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Simple Effects: | |||||||

| AAMvsWM for Females | <.0001 | 2.53 (1.66, 3.85) | .18 (.13, .25) |

.36 (.29, .43) |

- - |

- - |

|

| AAMvsWM for Males | .8781 | 0.96 (0.57, 1.62) | .32 (.23, .43) |

.31 (.24, .40) |

- - |

- - |

|

African American Menthol versus White Menthol;

Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence [29];

Other smokers present in participant’s home; used as indicator of environmental exposure to smoking;

Proportion of smokers in the participant’s social network: 1=none, 2=less than half, 3=about half, 4=more than half, and 5=all.

The next model (Model 3 in Table 6) added gender to Model 2 as a main effect and as an interaction with AAMvsWM. In this analysis, the AAMvsWM by gender interaction was statistically significant (p=.0048); we then computed simple main effects to unpack the interaction. More specifically, we computed ORs and model-based estimated probabilities of abstinence for AAMvsWM for females and males separately. As shown in Table 6, the AAMvsWM effect in females was statistically significant [p<.0001; OR=2.63 (1.75, 3.96)] whereas the AAMvsWM effect in males was non-significant [p=.9927; OR=1.01 (0.59, 1.74)]. The model-based estimated probability of abstinence for AA Female Menthol smokers was 17% compared to 35% for White Female Menthol smokers, and was 30% for both AA and White Male Menthol smokers. In fact, AA Female Menthol smokers were significantly less likely to be abstinent compared to any of the other three groups (White Female Menthol, AA Male Menthol, and White Male Menthol). Last, a test of the 3-way interaction of AAMvsWM, gender, and treatment was non-significant (results not reported in Table 6).

To test the robustness of the AAMvsWM by gender interaction, we added the sensitivity analysis covariates to Model 3 and found that the interaction remained statistically significant (p=.0051; see Model 4 in Table 6). ORs for the simple main effects (from the AAMvsWM by gender interaction) in Model 4 were very similar to those in Model 3.# Also, we repeated all of the Table 6 models in GLMMs and obtained the same pattern of significant and non-significant effects. Thus, the AAMvsWM by gender interaction appears to be robust, reflecting the especially low abstinence rate of AA females. In fact, the estimated abstinence rate for AA male menthol smokers was quite similar (32%) to that of White male menthol smokers (31%). The inclusion of site as a covariate did not change the pattern of results for any of the AAM vs. WM models.

Discussion

The chief finding of this research is that menthol-smoking is associated with a reduced likelhood of quitting smoking successfully. However, consistent with some prior research, the relapse risk associated with menthol-smoking varied somewhat across different groups of smokers. In one set of analyses, White non-Menthol smokers were compared with White and AA Menthol smokers combined into one group. This comparison showed reduced abstinence levels amongst menthol smokers, an effect that remained after the inclusion of relevant covariates, and that did not interact with treatment or gender.

In an effort to determine if race affected the cessation outcome, AA and White menthol smokers were directly compared in a subsequent set of longitudinal models. These models revealed an interaction between race and gender; specifically, AA female menthol smokers had significantly lower cessation outcomes than did White female menthol smokers, while White and AA male menthol smokers did not differ. Examination of Table 4 reveals that AA female menthol smokers consistently had the lowest cessation outcomes of all other groups formed by race, gender, and menthol-smoking status.

It might be tempting to focus on AA females as the nexus of menthol associated risk. However, a comprehensive analysis of the data challenges this characterization. For instance, the main longitudinal model comparing White non-Menthol smokers with the AA and White menthol smokers did not find a significant menthol status by gender interaction. In addition, an inspection of abstinence rates in Table 4 shows considerably lower abstinence rates for several of the menthol groups relative to White non-menthol smokers; viz. considerably lower rates amongst AA female, AA male, and White male menthol smokers. (Only White female menthol smokers had abstinence rates that were comparable to those of non-menthol smokers.) To ensure that there was a significant menthol effect that was not restricted to AA Menthol smokers, we conducted a secondary, longitudinal model that compared White male non-menthol smokers with White male menthol smokers over the three follow-up data points. This revealed significantly lower values in menthol smokers (OR = 1.52 (1.13, 2.06); p = .0066). In sum, menthol-smoking was associated with a heightened risk of cessation failure and this risk was most pronounced amongst, but not restricted to, AA females (e.g., see Table 4).

A variety of covariates (gender, treatment, education, tobacco dependence, site, and environmental exposure to smoking) tended not to eliminate the relations between menthol status and cessation. The robustness of the obtained effects in covariate-adjusted analyses suggests that the obtained relations may reflect causal actions of menthol-smoking and not just the influence of 3rd variables associated with menthol status. However, strong causal inference cannot be drawn from a single study in which contrasted groups were not randomly determined and which differ on multiple factors. For instance, some evidence showed that AA women who smoked menthol cigarettes were particularly likely to experience difficulty quitting. It would be difficult or impossible to covary out the characteristics of being an AA woman (e.g., stress levels, social and family burdens) so that the effects of menthol-smoking per se could be isolated. Moreover, intensive statistical adjustment of effects associated with menthol status might actually remove important information from the predictive models [30]. For instance, menthol and non-menthol smokers might differ on tobacco dependence, which might then be statistically controlled in prediction models. However, it is possible that such a dependence factor might account both for the appeal of menthol-smoking (explaining in part why a person might smoke them) and also for a heightened vulnerability to relapse. Statistical control over such factors could therefore mask a causal influence of menthol-smoking on cessation outcomes.

Particular strengths of the current study are the relatively large sample and the use of longitudinal analyses; both features permitted good statistical power. Limitations of this research were that: 1) it comprised treatment seeking smokers, so the data may not generalize well to the broad population of smokers, 2) there were too few AA non-menthol smokers and too few non-AA minorities to permit their inclusion in the analyses, and 3) menthol vs. non-menthol-smoking status was determined with a single question. It is possible that a more comprehensive assessment of menthol smoking history might have revealed additional important information.

The current results are consistent with a causal model comprising a general risk associated with menthol-smoking, plus more specific risks that are associated with particular sub-populations of menthol smokers. These results agree with some prior studies that have shown both types of risks [e.g., 14, 31,32]. However, little prior evidence shows an especially heightened risk of menthol-smoking amongst AA women and some studies show no association between menthol-smoking and cessation failure [7]. Clearly more research is needed on this topic.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants P50 DA019706, K05CA139871, and 3R01HL109031-02S1. Medications were provided to study participants at no cost under a research agreement with GlaxoSmithKline (GSK); GSK was not involved in the analyses of study data or the writing of this manuscript. The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all analyses, drafting and editing of the paper, and its final contents.

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest:

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Clinicaltrials.gov Registration #: NCT00332644

We conducted logistic regression analyses of the NMvsM effect for the 6-month outcome for each of the 3 models in Table 5. For model 1 (NMvsM only), the NMvsM effect was statistically significant (p=.0178; model-based estimated abstinence =35.9% for non-menthol smokers vs. 29.9% for menthol smokers; OR=0.76, 95% CI=0.61, 0.95). Model 2 (with covariates NMvsM and treatment) were nearly identical to Model 1. However, for Model 3 (with covariates NMvsM, treatment, and the 4 sensitivity analysis covariates), the NMvsM effect was non-significant (p=.1596; estimated abstinence =34.3% for non-menthol smoking vs. 30.7% for menthol smoking; OR=0.85, 95% CI=0.67, 1.07).

In logistic regression analyses of the AAMvsWM effect for the 6-month outcome, the key AAMvsWM by Gender interaction and simple effect for females remained statistically significant in all 4 models in Table 6. For example, in Model 4, the female AAMvsWM simple effect OR=2.28 (CI=1.28, 3.74); estimated abstinence =15.4% for female AA menthol smokers vs. 28.5% for female White menthol smokers. The corresponding simple effect for males was non-significant, p=.6749, with estimated abstinence =29.7% for male AA menthol smokers vs. 26.8% for male White menthol smokers; OR=0.87, 95% CI=0.45, 1.69).

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged >/=18 years--United States, 2005–2010. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1207–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, Rostrom B, Thun M, Anderson RN, et al. 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:341–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D, Freedman ND, Prentice R, Lopez AD, et al. 50-Year trends in smoking-related deaths in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:361–374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The NSDUH Report: Use of Menthol Cigarettes. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. Menthol cigarettes and public health: review of the scientific evidence and recommendations. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foulds J, Hooper MW, Pletcher MJ, Okuyemi KS. Do smokers of menthol cigarettes find it harder to quit smoking? Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;(Suppl 2):S102–S109. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman AC, Miceli D. Menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation behavior. Tob Induc Dis. 2011;9(Suppl 1):S6. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-9-S1-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cropsey KL, Weaver MF, Eldridge GD, Villalobos GC, Best AM, Stitzer ML. Differential success rates in racial groups: results of a clinical trial of smoking cessation among female prisoners. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:690–697. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu SS, Okuyemi KS, Partin MR, Ahluwalia JS, Nelson DB, Clothier BA, Joseph AM. Menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation during an aided quit attempt. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:457–462. doi: 10.1080/14622200801901914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris KJ, Okuyemi KS, Catley D, Mayo MS, Ge B, Ahluwalia JS. Predictors of smoking cessation among African-Americans enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of bupropion. Prev Med. 2004;38:498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foulds J, Gandhi KK, Steinberg MB, Richardson DL, Williams JM, Burke MV, Rhoads GG. Factors associated with quitting smoking at a tobacco dependence treatment clinic. Am J Health Behav. 2006;30:400–412. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2006.30.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gandhi KK, Foulds J, Steinberg MB, Lu SE, Williams JM. Lower quit rates among African American and Latino menthol cigarette smokers at a tobacco treatment clinic. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:360–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okuyemi KS, Faseru B, Sanderson Cox L, Bronars CA, Ahluwalia JS. Relationship between menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation among African American light smokers. Addiction. 2007;102:1979–1986. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okuyemi KS, Ahluwalia JS, Ebersole-Robinson M, Catley D, Mayo MS, Resnicow K. Does menthol attenuate the effect of bupropion among African American smokers? Addiction. 2003;98:1387–1393. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Silva J, Boyle RG, Lien R, Rode P, Okuyemi KS. Cessation outcomes among treatment-seeking menthol and nonmenthol smokers. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(5) Suppl 3:S242–S248. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faseru B, Nollen NL, Mayo MS, Krebill R, Choi WS, Benowitz NL, et al. Predictors of cessation in African American light smokers enrolled in a bupropion clinical trial. Addict Beh. 2013;38:1796–1803. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rojewski AM, Toll BA, O'Malley SS. Menthol cigarette use predicts treatment outcomes of weight-concerned smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt137. first published online October 10, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J-H, Herzog TA, Meade CD, Webb MS, Brandon TH. The use of GEE for analyzing longitudinal binomial data: A primer using data from a tobacco intervention. Addict Beh. 2007;32:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piper ME, Smith SS, Schlam TR, Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Fraser D, Baker TB. A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of 5 smoking cessation pharmacotherapies. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2009;66:1253–1262. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brigham J, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Javitz HS, McElroy M, Krasnow R, Swan GE. Reliability of adult retrospective recall of lifetime tobacco use. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:287–299. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Cancilla A. Reliability of a timeline method: Assessing normal drinkers' reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. Br J Addict. 1988;83:393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Longitudinal data analysis. New York: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosmer DW, Jr, Lemeshow SA, Sturdivant RX. Applied Logistic Regression. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diggle P, Heagarty P, Liang K-Y, Zeger S. Analysis of longitudinal data. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindsey JK, Lambert P. On the appropriateness of marginal models for repeated measurements in clinical trials. Stat Med. 1998;17:447–469. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980228)17:4<447::aid-sim752>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolt DM, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Japuntich SJ, Fiore MC, Smith SS, Baker TB. The Wisconsin Predicting Patients' Relapse questionnaire. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(5):481–492. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller GA, Chapman JP. Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. J Abnormal Psych. 2001;110:40–48. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stahre M, Okuyemi KS, Joseph AM, Fu SS. Racial/ethnic differences in menthol cigarette smoking, population quit ratios and utilization of evidence-based tobacco cessation treatments. Addiction. 2010;105(suppl. 1):75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trinidad DR, Perez-Stable EJ, Messer K, White MM, Pierce JP. Menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation among racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Addiction. 2010;105(Suppl 1):84–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]