Abstract

The growing burden of Alzheimer’s disease underscores the importance of enhancing current public health efforts to address dementia. Public health organizations and entities have substantial opportunities to contribute to efforts underway and to add innovations to the field. The Alzheimer’s Association and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention worked with a 15-member leadership committee and hundreds of stakeholders to create The Healthy Brain Initiative: The Public Health Road Map for State and National Partnerships, 2013–2018 (Road Map). The actions in the Road Map provide a foundation for the public health community to anticipate and respond to emerging innovations and developments. It will be a challenge to harness the increasingly complex nature of public- and private-sector collaborations. We must strengthen the capacity of public health agencies, leverage partnerships, and find new ways to integrate cognitive functioning into public health efforts.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Healthy Brain Initiative, Road Map, Public health partnerships

1. Introduction

The growing burden of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) underscores the importance of enhancing current public health efforts to address cognitive health and impairment. In 2007, Alzheimer’s and Dementia published a supplemental issue devoted to the factors that influence the maintenance and promotion of cognitive health [1]. That issue compiled a unique collection of articles covering presentations and discussions held during the meeting, The Healthy Brain and Our Aging Population: Translating Science into Public Health Practice [2]. Subsequently, that work provided the scientific foundation for The Healthy Brain Initiative: A National Public Health Road Map to Maintaining Cognitive Health (2007 Road Map [3]). The Road Map, a joint effort and publication of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Healthy Aging Program and the Alzheimer’s Association, clearly delineated the vital role that the public health community has to play in addressing cognitive health. Its 5-year set of priority actions served as a catalyst for numerous important public health actions and accomplishments to address AD and other dementias [4].

To expand and accelerate the public health community’s involvement in addressing and promoting cognitive functioning, in 2013, the Alzheimer’s Association and CDC created and released a new Road Map—The Healthy Brain Initiative: The Public Health Road Map for State and National Partnerships, 2013–2018 [5]. It supports and articulates a comprehensive public health approach [6], focusing on a continuum of efforts at the individual, interpersonal, community, systems, and policy levels to effectively promote cognitive health and address cognitive impairment.

2. The public health imperative and the initial road map

AD is the sixth leading cause of death across all ages in the United States [7]. One in eight adults aged 60 years and older report experiencing “increased confusion or memory loss that is happening more often or is getting worse” in the 12 months preceding the survey, and only 19.3% of this group reported discussing these changes with a health care provider [8]. In 2010, the direct health care expenditures for dementia were significantly higher than cancer and similar to heart disease [9]. The growing personal, family, health care, social, and economic burdens of AD have led to its emergence as a national and international priority[10,11]. The role of public health in addressing these issues has gained visibility among federal agencies, health professionals, and decision makers.

That visibility began in earnest when the CDC received Congressional funding in FY2005 to create an AD segment within CDC’s Healthy Aging Program, subsequently titled The Healthy Brain Initiative [12], and to partner with the Alzheimer’s Association to promote knowledge and awareness about cognitive health and AD as a public health issue. One of the foundational initiatives was the creation and implementation of the 2007 Road Map. This effort also included numerous partners such as the AARP, the Administration on Aging (now within the Administration for Community Living), the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors, and the National Institute on Aging. The creators of the 2007 Road Map envisioned a nation where the public embraces cognitive health as a priority and invests in furthering research and health promotion efforts [13].

The actions of the 2007 Road Map fell under the purview of many organizations and sectors, and there are numerous notable strategic changes that were accomplished during the past 6 years [4]. For example, one of the 10 priority actions was to “Include cognitive health in Healthy People 2020, a set of health objectives for the nation that will serve as the foundation for state and community public health plans” [14]. When the Healthy People 2020 objectives were released in 2010, they included the new topic “Dementias, including Alzheimer’s disease,” with two developmental objectives. Additionally, objectives that include cognition and address caregiver support are included in the “Older Adults” topic [15]. Before this, AD was the only leading cause of death that did not have a designated topic area within Healthy People, the premier public health blue-print for the nation. Other examples of changes resulting from the 2007 Road Map include developing, testing, and implementing questions in the state-based Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS; http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/) concerning perceptions about increased confusion or memory loss [8]; adding a caregiver question [16] to the 2009 BRFSS core survey; supporting states use of the BRFSS optional module on caregiving [17]; helping to advance the understanding of the public’s perceptions about cognition through research [18,19]; and examining the translation of interventions into public health practice through reviews of the literature [20,21].

3. Developing the 2013 Healthy Brain Initiative Road Map

Importantly, the release of inaugural “National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease” in 2012 [22] provided a critical juncture in which these national efforts could be focused on at state and local levels. Public health organizations and entities have substantial opportunities to contribute to efforts already underway and add new innovations to the field. The co-chairs from the Alzheimer’s Association and the CDC worked with a 13-member leadership committee to create the 2013 Road Map, the first effort to focus on the role of public health in states and communities.

The 2013 Road Map reflects the culmination of a yearlong process that solicited the input of hundreds of informed and knowledgeable professionals in public health, aging, and AD who represent national, state, and local agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and academic institutions. From their feedback, the action items in the Road Map were created. The current state of the science on cognition and variability in public health efforts among states shaped the process for developing the Road Map. It was critical to obtain the input of state and local entities to ensure their perspectives were reflected in the final document. As a result, the strategic planning process was organized into three overarching phases, using Trochim’s concept mapping steps as a guide [23]. Concept mapping, which consists of a sequence of phases that yields a snapshot of a shared group of ideas [23], was used to identify action items, form a conceptual framework, and help prioritize the final set of action items that would be included in the 2013 Road Map.

The first phase, project planning, consisted of the formation of the leadership committee and the generation and preparation of ideas in response to the following statement: “A specific action that state or local public health could do— on their own or with other national, state, or local partners— to address or promote cognitive functioning for people living in the community and the needs of care partners is…”. Using snowballing technique, a total of 287 people were identified and subsequently invited to participate in the idea generation phase. About half of the leadership committee and individuals invited to contribute ideas represented state and local entities. Individuals from multiple sectors with various experiences and expertise about cognitive health or impairment were included. Participation was anonymous. A total of 370 ideas were generated. Repetitive ideas and those deemed not to address the focus question were eliminated and with input of the leadership committee, a total of 54 ideas advanced into phase 2.

Phase 2, generating concept maps, consisted of the structure and representation of action items, to sort and rate action items and to construct a series of concept maps. Members of the leadership committee and 64 individuals who represented various sectors were invited to sort the ideas into themes based on similarity of ideas. All individuals originally invited to provide ideas were invited to rate the ideas based on criticality and feasibility. Again, participation was anonymous. Based on unique identifiers, an estimated 53% of those invited to sort completed the task, and about one-third rated the items.

Phase 3, finalizing the map and creating the framework, consisted of the interpretation and utilization of maps and prioritizing action items for inclusion in the Road Map. With guidance from the leadership committee, the action items were grouped into four domains, consistent with the essential services of public health [24], and labeled as follows: monitor and evaluate, educate and empower the nation, develop policy and mobilize partnerships, and assure a competent workforce. Based on the input of the leadership committee, 35 items were selected for inclusion in the Road Map; these were edited for clarity. Examples include:

Promote advance care and financial planning.

Ensure that state public health departments have expertise in cognitive health and impairment.

Promote participation in clinical trials and studies.

Support continuing education efforts to improve providers’ ability to recognize early signs of dementia.

All action items were deemed important, but across the domains, 12 action items were judged by the leadership committee to be issues of particular importance and areas in which movement could be achieved in the near term by groups and entities new to this area.

4. Framework for action and next steps

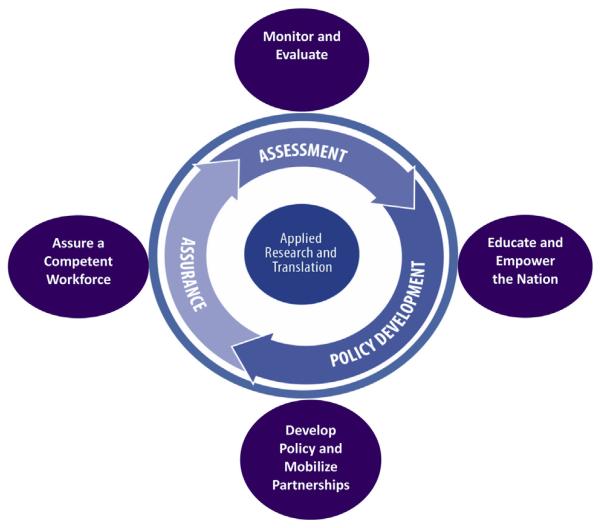

The 2013 Road Map calls attention to the importance of using public health tools to promote cognitive function, address cognitive impairment, and help meet the needs of caregivers, including public health surveillance systems, the translation of research findings, the development of effective public health programs, and the promotion of partnerships such as public health and aging services professionals. The four domains of the Road Map (monitor and evaluate; educate and empower the nation; develop policy and mobilize partnerships; and assure a competent workforce) are in alignment with states carrying out the three core functions of public health [25]: assessment (e.g., collection and analysis of data); policy development (e.g., inform and empower the public on health issues of concern, change knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors; promote partnerships); and assurance (e.g., manage resources, develop organization structures, and provide quality assurance) (Fig. 1). The application of these public health core functions to cognitive health provides public health officials with a framework to address cognitive health and offers hope of achievements similar to those achieved in other areas during the last century [26] and the first decade of the 21st century [27].

Fig. 1.

Healthy Brain Road Map domains linked to core functions of public health.

5. Conclusions

Although public health professionals may at first perceive cognitive health and impairment beyond their traditional scope, public health principles and practices have much to offer to individuals, their families, and society. The actions in the 2013 Road Map provide a foundation for the public health community to anticipate and respond to emerging innovations and developments. Communication tools and technologies can help facilitate interactive conversations among diverse partners, giving public health practitioners the ability to have dialogues with people from affected communities and other partners [28].

The implementation of the action items in the Road Map calls for collaborative action. A challenge will be to harness and navigate the increasingly complex nature of public- and private-sector collaborations and act within the key domains that are critical to promote and implement the actions of the Road Map. To do this, we will have to strengthen the capacity of public health agencies, and leverage strong state and national coalitions [28].

Finally, the 2013 Road Map should be viewed as a living document. The collective understanding of state and national partnerships is only as useful as the evidence on which it is based. During the time span of the Road Map, current and future research will yield new knowledge that will influence and be incorporated into the strategic plans related to the action items in the Road Map. Given current conversations about priorities to address AD, state and community perspectives need to be included in these discussions, and public health actions need to be part of the efforts. The 2013 Road Map provides a solid foundation to guide those actions.

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest or financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this article. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- [1].The healthy brain and our aging population. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2007;3:S1–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Albert MS, Brown DR, Buchner D, Laditka J, Launer JJ, Scherr P, et al. The healthy brain and our aging population: translating science to public health practice. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3:S3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Alzheimer’s Association . The Healthy Brain Initiative: a national public health road map to maintaining cognitive health. Alzheimer’s Association; Chicago, IL: [Accessed January 12, 2014]. 2007. Available at: www.cdc.gov/aging. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . The CDC Healthy Brain Initiative: progress 2006–2011. CDC; Atlanta, GA: [Accessed January 12, 2014]. 2011. Available at: www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/HBIBook_508.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Alzheimer’s Association and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . The Healthy Brain Initiative: The public health road map for state and national partnerships, 2013–2018. Alzheimer’s Association; Chicago, IL: [Accessed January 12, 2014]. 2013. Available at: www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/2013-healthy-brain-initiative.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:590–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Xu J, Kochanek KD, Sherry L, Murphy BS, Tejada-Vera B. National Vital Statistics Reports. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: [Accessed January 12, 2014]. 2010. Deaths: final data for 2007. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_19.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Self-reported increased confusion or memory loss and associated functional difficulties among adults aged ≥60 years—21 states, 2011. MMWR. 2013;62:345–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1326–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].National Alzheimer’s Project Act [Accessed January 13, 2014];Public Law 111–375—Jan. 4. 2011 Available at: www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ375/pdf/PLAW-111publ375.pdf.

- [11].World Health Organization and Alzheimer’s Disease International . Dementia: a public health priority. World Health Organization; [Accessed January 12, 2014]. 2012. Available at: www.who.int/mental_health/publications/dementia_report_2012/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Anderson LA, McConnell SR. Cognitive health: an emerging public health issue. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(S2):3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Day KL, McGuire LC, Anderson LA. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Healthy Brain Initiative: emerging implications of cognitive impairment. Generations. 2009;33:11–7. [Google Scholar]

- [14].U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: [Accessed January 12, 2014]. Dementias, including Alzheimer’s disease. Available at: www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid57. [Google Scholar]

- [15].U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Older adults. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: [Accessed February 19, 2014]. Available at: www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid531. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Anderson LA, Edwards VJ, Pearson WS, Talley RC, McGuire LC, Andresen EM. Adult caregivers in the United States: characteristics and differences in well-being, by caregiver age and caregiving status. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:130090. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bouldin ED, Andresen E. Caregiving across the US. Caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia in Connecticut, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, and Tennessee. Alzheimer’s Association; [Accessed January 12, 2014]. 2010. Available at: www.alz.org/publichealth. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Anderson LA, Day KL, Beard RL, Reed PS, Wu B. The public’s perceptions about cognitive health and Alzheimer’s disease among the U.S. population: a national review. Gerontologist. 2009;49(S1):S3–11. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Friedman DB, Rose ID, Anderson LA, Hunter R, Bryan LL, Wu B, et al. Beliefs and Communication practices regarding cognitive functioning among consumers and primary care providers in the United States, 2009. Prev Chron Dis. 2013;10:120249. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Frederick JT, Steinman LE, Prohaska T, Satariano WA, Bruce M, Bryant L, et al. Community-based treatment of late life depression: an expert panel informed literature review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:222–49. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Snowden M, Steinman L, Mochan K, Grodstein F, Prohaska TR, Thurman DJ, et al. Effect of exercise on cognitive performance in community-dwelling older adults: review of intervention trials and recommendations for public health practice and research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:704–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . National plan to address Alzheimer’s disease. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; [Accessed January 13, 2014]. 2012. Available at: www.aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/napa/NatlPlan.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Trochim W. An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Eval Program Plann. 1989;12(special issue):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- [24].U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service . The public health workforce: an agenda for the 21st century. A report of the Public Health Functions Project. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Institute of Medicine . The future of public health. National Academy Press; Washington (DC): [Accessed January 12, 2014]. 1988. Available at: www.iom.edu/Reports/1988/The-Future-of-Public-Health.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Ten great public health achievements— United States, 1900–1999. MMWR. 1999;48:241–3. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Ten great public health achievements— United States, 2001–2010. MMWR. 2011;60:619–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Frieden TR. Six components necessary for effective public health program implementation. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:17–22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]