Abstract

Background

We compared performance of validated laparoscopic tasks on four commercially available single site access (SSA) access devices (AD) versus an independent port (IP) SSA set-up.

Methods

A prospective, randomized comparison of laparoscopic skills performance on four AD (GelPOINT™, SILS™ Port, SSL Access System™, TriPort™) and one IP SSA set-up was conducted. Eighteen medical students (2nd–4th year), four surgical residents, and five attending surgeons were trained to proficiency in multi-port laparoscopy using four laparoscopic drills (peg transfer, bean drop, pattern cutting, extracorporeal suturing) in a laparoscopic trainer box. Drills were then performed in random order on each IP-SSA and AD-SSA set-up using straight laparoscopic instruments. Repetitions were timed and errors recorded. Data are mean ± SD, and statistical analysis was by two-way ANOVA with Tukey HSD post-hoc tests.

Results

Attending surgeons had significantly faster total task times than residents or students (p< 0.001), but the difference between residents and students was NS. Pair-wise comparisons revealed significantly faster total task times for the IP-SSA set-up compared to all four AD-SSA’s within the student group only (p<0.05). Total task times for residents and attending surgeons showed a similar profile, but the differences were NS. When data for the three groups was combined, the total task time was less for the IP-SSA set-up than for each of the four AD-SSA set-ups (p < 0.001). Similarly,, the IP-SSA set-up was significantly faster than 3 of 4 AD-SSA set-ups for peg transfer, 3 of 4 for pattern cutting, and 2 of 4 for suturing. No significant differences in error rates between IP-SSA and AD-SSA set-ups were detected.

Conclusions

When compared to an IP-SSA laparoscopic set-up, single site access devices are associated with longer task performance times in a trainer box model, independent of level of training. Task performance was similar across different SSA devices.

Keywords: Single incision laparoscopy, skills training

INTRODUCTION

Single-site access laparoscopic surgery (SSA) has developed rapidly in the last 3–4 years as an alternative to scarless natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery (NOTES).[1, 2] This technique has now been applied to virtually every laparoscopic abdominal procedure,[3–9] and the number of publications on this technique has grown exponentially.[10] A recent systematic review by Ahmed et al[11] identified 102 clinical studies of SSA or laparo-endoscopic single site surgery (LESS) in general, urologic and gynecologic surgery, most of which were conducted within the last five years. However, most of the current SSA literature consists of case reports and case-series, with relatively little objective evidence of benefits beyond improved cosmesis.[12–14]

As a result of the rapid expansion of research and clinical interest in SSA, several medical device manufacturers have designed single-site access devices to facilitate performance of SSA or LESS procedures. These devices combine various numbers of access ports for a camera and two or three instruments into a single integrated port. However, to our knowledge, only one study has evaluated skills performance on one of these devices in a simulated setting.[15] Previous work from our group revealed differences in skill acquisition time between traditional laparoscopy and SSA using a trainer box setup and various simulated laparoscopic skills tasks, with longer times and more repetitions required to achieve proficiency on an SSA set-up than with a traditional multi-port laparoscopic model.[16] However, the skills acquired during SSA training transferred readily to multi-port laparoscopy.

We hypothesized that SSA devices might confer advantages over an independent-port SSA set-up, particularly for more complex tasks such as laparoscopic suturing. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to compare performance of validated laparoscopic tasks on an independent port (IP) SSA set-up to four commercially available SSA access devices (AD) in a skills laboratory setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and Study Design

Thirty-seven subjects agreed to participate in the study. These consisted of 12 second-year medical students with no prior laparoscopic surgical experience, 12 third-year medical students, 3 fourth-year medical students, 5 general surgery residents in clinical years PGY-3 to PGY-5,, and 5 expert laparoscopic surgeons (four attendings and one advanced Minimally Invasive Surgery [MIS] fellow). Eleven of the third year medical students had participated in a previous study of laparoscopic skills acquisition carried out by our group.[16] The study was carried out under a protocol approved by the institutional review board of Washington University School of Medicine.

Medical student participants with no prior laparoscopic skills experience attended a training session where an attending laparoscopic surgeon (LMB and JEV) provided instruction on proper use of laparoscopic equipment and performance of four standard laparoscopic drills using a multi-port set-up. Following the training session, each medical student participant practiced each task on a standard multi-port set-up until they reached proficiency targets for that task. Participants who did not require participation in a training session because of prior experience with these drills (general surgery residents and attendings) were timed and tested on the standard multi-port set-up to verify baseline proficiency prior to participation in the SSA portion of the study. After reaching (or verifying) proficiency targets, participants performed each task on all five single-incision laparoscopy setups in a random order. These tasks were then repeated on each device for a total of three sets of all 4 tasks on all five SSA set-ups for every participant. Each repetition was timed and recorded by one of the investigators (MRS).

Training Set-ups and Equipment

A standard multi-port laparoscopy setup, an independent-port single-incision setup, and four single-incision devices were used as shown in Fig. 1. The single-incision devices included the GelPOINT™ (Applied Medical Resources Corporation, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA), the SILS™ Port (Covidien, Manchester, MA), the SSL Access System™ (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH), and the Olympus TriPort™ (Advanced Surgical Concepts, Bray, Ireland). In the standard multi-port setup, the 5mm ports (Ethicon Endosurgery, Cincinnati, OH) were placed in standard instrument port positions triangulated with the camera port. For the independent-port single-incision setup, the camera port was placed in the midline position and low profile instrument ports (Covidien, Manchester, MA) were placed at the same access site in an equilateral triangle configuration with each of the ports 2–2.5 cm apart.

Fig. 1.

Photographs of various port set-ups. A) multiport; B) multiple independent single site ports; C) GelPOINT™; D) SILS™ Port; E) SSL Access System™; and F) TriPort™.

Drills

Four standard laparoscopic drills were used for the study: peg transfer, bean drop, pattern cutting and suturing with extracorporeal knot tying. The peg transfer, pattern cutting, and extracorporeal tasks are from the SAGES Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery tasks and were performed as previously described.[16, 17] The bean drop task as described by Rosser[18] consisted of transfer of beans into a 1.2cm hole in an inverted cup over 90 seconds. Further details of the set-up of these tasks for the SSA approach were as previously reported by our group.[16]

The peg transfer and bean drop tasks were selected as two basic tasks, pattern cutting as an intermediate task, and suturing with extracorporeal knot tying as an advanced task. A stationary camera was used for all tasks except the bean drop in which case the participant also controlled the laparoscope. Extracorporeal suturing was chosen instead of intracorporeal suturing because the movements required inside the training box are less complex, and because it was felt that intracorporeal tying would be too difficult to accomplish in the SSA set-up, especially given the wide range of experience of the participants.

Statistical Analysis

All data are mean ± SD. Analysis of data including means between and within groups was by two-way ANOVA with Tukey HSD post-hoc tests, with p <0.05 considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 2.11.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

RESULTS

Of the original participants recruited to take part in the study, the protocol was completed by 18 medical students (8 second-years, 8 third-years, and 2 fourth-years), 4 general surgery residents, and 5 attending surgeons. Participants who were unable to complete the protocol failed to do so primarily because of the time involved and/or inability to reach proficiency targets. The mean age of study participants was 27 ± 5.8 years.

The total times required to complete the four tasks for the various groups are shown in Table 1. Medical students’ total times using the independent-port set-up were significantly faster than their times on all four access devices. When the second-year medical students’ times and the third- and fourth-year medical students’ times were compared, no significant differences in their performance on any task using any port set-up was observed (data not shown). Although total task times averaged ≥90 seconds longer for each of the access device set-ups vs independent SSA set-up for both resident and attending surgeons groups, the differences were not significant.

Table 1.

Total Times for Completion of All Four Tasks for Various SSA Device Set-ups for the Study Groups

| SSA Laparoscopic Port Set-up |

Students (n=18) | Residents (n=4) | Attendings (n=5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | 428.0 ± 65.9 | 409.1 ± 79.3 | 317.1 ± 42.5 |

| GelPOINT™ | 573.0 ± 99.2 * | 530.2 ± 30.5 | 417.6 ± 85.0 |

| SILS™ Port | 569.2 ± 110.4 * | 523.2 ± 57.5 | 407.6 ± 94.5 |

| SSL Access System™ | 599.6 ± 102.7 * | 622.4 ± 145.8 | 429.8 ± 47.0 |

| TriPort™ | 618.6 ± 108.6 * | 562.2 ± 117.3 | 434.0 ± 83.0 |

Denotes p<0.05 compared with independent port set-up within each group. SSA = single site access laparoscopy.

Regardless of the port used, surgeons performed the tasks significantly faster than medical students or residents (p < 0.001), but the difference between medical students and residents was not significant. When all participants were analyzed together, total task times were significantly faster for the independent-SSA set-up than for each of the four AD-SSA set-ups (p<0.05).

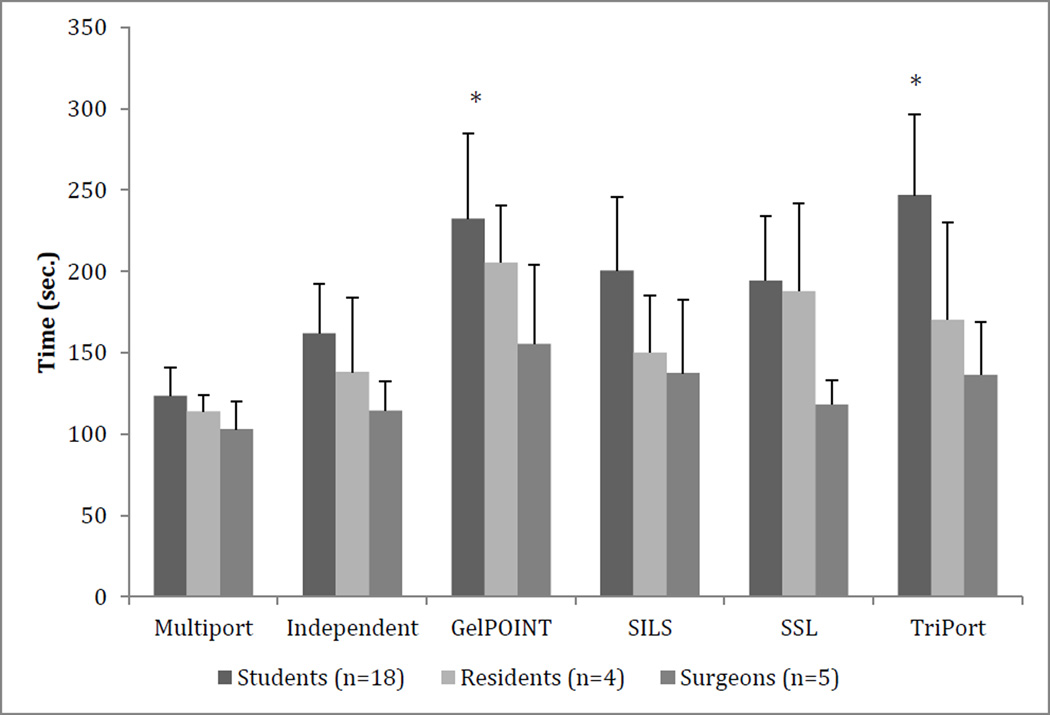

The mean times required for the various study groups (medical students, residents, attendings) to complete each individual task (peg transfer, bean drop, pattern cutting, and extracorporeal suturing) are shown in Figs. 2–5, respectively. The only significant differences between independent port and the AD times by level of trainee were in the medical student group. As shown in the figures, medical student IP-SSA times were significantly faster versus 2 of 4 access devices for peg transfer, none for bean drop, 4 of 4 for pattern cutting, and 2 of 4 for suturing. However, when task time data for all three groups were combined for each task (eg, combined student, resident, and attending data into one group), task performance times on the independent SSA set-up were significantly faster than the AD-SSA set-ups for 3 of 4 devices for peg transfer, 4 of 4 devices for pattern cutting, and 3 of 4 devices for extracorporeal suturing, but 0 of 4 for the bean drop task (p<0.05).

Fig. 2.

Peg transfer times for each group. * denotes p < 0.05 compared with the independent port set-up.

Fig. 5.

Suturing times for each group. * denotes p < 0.05 compared with the independent port set-up.

DISCUSSION

Despite the increased application of single site approaches to laparoscopic surgery clinically, there has been very little work done to evaluate performance characteristics of SSA approaches in a simulated environment. SSA laparoscopy differs from conventional multiport in a number of respects, including the loss of triangulation, instrument paths that are an in-line almost parallel configuration, and close proximity of the working instruments and camera/laparoscope unit which may restrict freedom of movement and lead to clashing of instruments.[19] As a result, simulation may be a useful step to gain understanding about performance of basic and advanced laparoscopic tasks in an SSA type set-up before carrying out these procedures clinically.

The initial approaches to single incision laparoscopy utilized independent low profile ports placed through an open 1.5–2cm incision, usually located at the umbilicus.[20] In some cases, ancillary instruments have been placed directly through the fascia without a port. In order to facilitate the performance of these procedures and provide some standardization, a number of medical device companies have designed single site access port devices in which the device is placed through an open 1.5–2cm fascial incision. These devices have been designed either with multiple fixed low profile ports or channels for instruments housed within the device or with a gel type barrier that allows some degree of customization of the number and location of the ports and instruments. However, while a number of procedures have been performed in which these devices were preferentially utilized,[13, 21] no comparative data exist on how these devices perform clinically or in a simulated setting. In one recent review, no clearly defined advantages were identified for any one existing port set-up over the other.[22]

Our group previously reported results of a comparative analysis of standard multiport (MP) versus single site access for laparoscopic skills training in surgically naïve medical students.[16] In this study, students were randomized into two groups, one of which underwent training to proficiency in a standard multiport set-up and the other were trained and tested initially on an independent single port SSA set-up using no specialized access devices. Performance on four tasks was assessed: peg transfer, rope drill, bean drop, and pattern cutting. Not surprisingly, the students in the multiport group reached proficiency in less time and with fewer repetitions than those in the single-site access group. The students in each group then crossed over to the other set-up. The skills development in the SSA trained group transferred well to the multi-port set-up and, in fact, many students were automatically proficient in the MP tasks. Multiport training also transferred to some extent to the SSA set-up, but students in that group still needed almost 2 hours of practice time and an average of 86 repetitions to reach proficiency, compared to only 38 minutes and 27 repetitions for the SSA trained group to achieve proficiency when they crossed over to the MP set-up.

Santos and colleagues[15] recently compared FLS task performance using a standard multi-port versus SILS™ platform. Inexperienced (medical students and PGY-1 residents), laparoscopy experienced (PGY2-5 residents) and SSA experienced surgeons were tested. Overall FLS scores were significantly lower in the SILS™ set-up across all groups tested. For individual tasks, this effect was similar for peg transfer, pattern cutting and endoloop tasks. For suturing tasks, the inexperienced group actually performed better on the SILS™ platform while the experienced laparoscopy group performed better on the standard set-up. Suture performance in the SSA experienced group was similar with the two approaches. Of note is that suturing in this study was performed using an articulating grasper and articulating suturing instrument.

Laparoscopic intracorporeal suturing performance was assessed by Rieder and asociates[23] in a novel single port triangulating surgical platform. All participants were proficient in intracorporeal suturing in a standard laparoscopic set-up. However, performance decreased by more than 50% when a single site approach using one straight and one articulating instrument was employed. With the single port triangulating system, which allowed insertion of two articulating instruments with true-right and true-left maneuvering, performance improved significantly, although not quite to the level of the standard laparoscopic approach.

In the present study, we sought to extend our prior work and investigate the performance of various levels of trainees from naïve to expert using four commercially available SSA access devices. We included both surgically naïve 2nd year medical students as well as students from the 3rd and 4th years who participated in the previous SSA skills study or had rotated on our MIS service. R3–R5 categorical general surgery residents were included as an intermediate level group and compared to attending surgeons in the Section of Minimally Invasive Surgery. Since an advantage of the commercial access devices might be in the performance of more complex tasks and procedures, we included four different tasks that we considered to reflect basic (peg transfer and bean drop), intermediate (pattern cutting), and advanced (extracorporeal suturing) laparoscopic skills.

Our results show that single-site access devices are associated with longer task performance times than an independent-port single-site set-up in a skills lab setting. A difference of over 100 seconds was observed between medical students’ independent-SSA and access device-SSA total task times. Similar time differences were seen between resident/attending IP vs access device times, although the differences were not significant due to the small number of participants in each of those groups. For each individual task, mean task times were significantly longer than the independent-port set-up for two devices for peg transfer, all four devices for pattern cutting, and two devices for suturing. Regardless of the port used, surgeons performed the tasks significantly faster than medical students or residents, but the difference between medical students and residents was not significant, which was likely due to the small number of residents participating in the study.

When all participants were analyzed together, the independent SSA set-up was significantly faster than the AD-SSA set-ups for 3 of 4 devices for peg transfer, 4 of 4 devices for pattern cutting, and 3 of 4 devices for extracorporeal suturing but none of 4 for the bean drop task. Subjectively, we observed increased difficulty performing tasks with commercial access devices due primarily to the close proximity or sword-fighting of instruments, and increased torque across the instruments and devices more so than the lack of triangulation. These observations likely explain why there was no difference in outcomes for the bean drop task when only two instruments were used (camera and one grasper) in contrast to the other tasks which all required the camera port plus two other instruments. Some participants adapted by learning to place the suture with a single hand, as close apposition of the grasper to the needle driver was often difficult or impossible with the AD. The need for increased torque against the AD port set-up when reaching deep into the field, such as the movements required to cut the distal part of the circle pattern was also a common concern with the access devices.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size in the resident and surgeon groups was too small to detect a significant difference between the access device SSA and independent SSA set-ups. We intentionally limited attending participation to those with prior SSA experience clinically. Moreover, participation in the study was voluntary and time consuming, as one cycle through all five device set-ups took approximately 1–1.5 hours to perform and had to be repeated one to two times, which limited broader participation by residents on clinical rotations. We sought to minimize the learning curve effect in this study by ensuring that all participants were trained and/or tested to proficiency on a standard multiport set-up before beginning the SSA task trial. In addition, all tasks were repeated 2–3 times on each SSA device set-up in random order so that the learning curve effect on performance was spread out over the entire range of devices.

A second limitation of this study is that we have not studied whether these findings are transferable to performance in the operating room. Although the drills used for this study are validated and are commonly used for training, the drills have also not been validated for use in a single-incision model. Third, we did not take advantage of articulating instruments and/or flexible tip cameras and other technical advances that facilitate single-incision laparoscopic surgery and potentially improve performance on an SSA platform.[24] However, because of the range of flexible shaft instruments designs and the different experience level of participants, it was felt that this would introduce another variable, the impact of which would be difficult to gauge.

Finally, there are many characteristics of single-site access devices that are important in clinical practice that we did not evaluate; these include durability, maintenance of pneumoperitoneum, biocompatibility, and cost. For more advanced laparoscopic cases in which a fascial incision of 2.5cm or more is going to be made for reasons of specimen extraction (eg laparoscopic colectomy or lap band placement), an access device may allow greater freedom of movement than we observed in the trainer box model. Thus, although our results describe the performance characteristics of single-site access devices in a skills lab setting, they may not be applicable to all clinical scenarios. Further studies are needed to better elucidate the optimal characteristics of an access device for single-site laparoscopy, which include ease of assembly, ability to effectively maintain pneumoperitoneum, minimization of clashing and smudging, ability to limit excessive torque, and accommodation of both standard and articulating laparoscopic instruments.

In summary, we have shown that SSA access devices confer no performance advantages over an independent-port set-up in a trainer box model. Surgeons who intend to use these devices for advanced laparoscopic cases may find it helpful to first gain experience and understand the device benefits and limitations in a simulation model such as we have described herein before using them in the operating room. Furthermore, we would argue that manufacturers of these devices should incorporate access device specific skills training into their educational programs on SSA surgery. Further studies will be needed to determine whether our findings translate into clinical performance.

Fig. 3.

Bean drop times for each group. None of times were significantly different between groups.

Fig. 4.

Pattern cutting times for each group. * denotes p < 0.05 compared with the independent port set-up.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the Washington University Institute for Minimally Invasive Surgery and a grant from Donald M. Sher for support of this study. Matthew R. Schill was supported by NIH grant T35 DK074375.

J. Esteban Varela receives consulting fees from Ethicon Endo-Surgery. Margaret M Frisella receives consulting fees from Atrium Medical. L. Michael Brunt has received grant support from Ethicon Endo-Surgery and fees for speaking and teaching from Lifecell Corp, neither of which relate to the content of this study.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures:

Matthew R. Schill has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Chamberlain R, Sakpal S. A comprehensive review of single-incision laparoscopic surgery(SILS) and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) techniques for cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1733–1740. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0902-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romanelli J, Roshek T, III, Lynn D, Earle D. Single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: initial experience. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1374–1379. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0781-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podolsky E, Curcillo P. Single port access (SPA) surgery- a 24-month experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:759–767. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vidal O, Valentini M, Ginesta C, Marti J, Espert JJ, Benarroch G, Garcia-Valdecasas JC. Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:686–691. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0661-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeong B, Park Y, Han D, KIm H. Laparoendoscopic single-site and conventional laparoscopic adrenalectomy: a matched-case-control study. J Endourol. 2009;23:1957–1960. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen N, Slone J, Reavis K. Comparison study of conventional laparoscopic gastric banding versus laparoendoscopic single site gastric banding. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:503–507. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gandhi D, Ragupathi M, Patel C, Ramos-Valadez D, Bartley Pickron T, Haas E. Single-incision versus hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy: a case-matched series. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1875–1880. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1355-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Filipovic-Cugura J, Kirac I, Kulis T, Jankovic J, Bekavac-Beslin M. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) for totally extraperitoneal (TEP) inguinal hernia repair:first case. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:920–921. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0318-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Targarona EM, Pallares J, Balague C, Rodriguez Luppi C, Marinello F, Hernandez P, Martinez C, Trias M. Single incision approach for splenic diseases: a preliminary report on a series of 8 cases. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2236–2240. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0940-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfluke J, Parker M, Stauffer J, Paetau A, Bowers SP, Asbun H, Smith C. Laparoscopic surgery performed through a single incision:a systematic review of the current literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed K, Wang T, Patel V, Nagpal K, Clark J, Ali M, Deeba S, Ashrafian HDA, Athanasiou T, Paraskeva P. The role of single-incision laparoscopic surgery in abdominal and pelvic surgery: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:378–396. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canes D, Berger A, Aron M, Brandina R, Goldfarb DA, Shoskes D, Desai M, Gill I. Laparo-endoscopic single site(LESS) versus standard laparoscopic left donor nephrectomy:matched-pair comparison. European Urology. 2010;57:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marks J, Tacchino R, Roberts K, Onders R, Denoto G, Paraskeva P, Rivas H, Soper NJ, Rosemurgy AS, Shah S. Prospective randomized controlled trial of traditional laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: report of preliminary data. Am J Surg. 2011;201:369–373. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garey C, Laituri C, Ostlie D, St. Peter S. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery and the necessity for prospective evidence. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2010;20:503–506. doi: 10.1089/lap.2009.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santos B, Enter D, Sopher N, Hungness E. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery(SILS) versus standard laparoscopic surgery: a comparison of performance using a surgical simulator. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:483–490. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox D, Zeng W, Frisella MM, Brunt LM. Analysis of standard multiport versus single-site access for laparoscopic skills training. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1238–1244. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1349-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SAGES. Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons Fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery (FLS) program. 2010 http://flsprogram.org. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosser JC, Rosser LE, Savalgi RS. Skill acquisition and assessment for laparoscopic surgery. Arch Surg. 1997;132:200–204. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430260098021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rawlings A, Hodgett S, Matthews BD, Strasberg SM, Quasebarth MA, LM B. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: initial experience with critical view of safety dissection and routine intraoperative cholangiography. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curcillo P, Wu A, Podolsky E, Graybeal C, Katkhouda N, Saenz A, Dunham R, Fendley S, Neff M, Copper C, Bessler M, Gumbs A, Norton M, Iannelli A, Mason R, Moazzez A, Cohen L, Mouhlas A, Poor A. Single-port -access (SPA) cholecystectomy: a multi-institutional report of the first 297 cases. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1854–1860. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0856-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varela JE. Single-site laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: preclinical use of a novel multi-access port device. Surg Innov. 2009;16:207–210. doi: 10.1177/1553350609345489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khanna R, White MA, Autorino R, Laydner HK, Isac W, et al. Selection of a port for laparoendoscopic single-site surgery. Curr Urol Rep. 2011;12:94–99. doi: 10.1007/s11934-011-0174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rieder E, Martinec D, Cassera M, Goers T, Dunst C, Swanstrom L. A triangulating operating platform enhances bimanual performance and reduces surgical workload in single-incision laparoscopy. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rimonda R, Tang B, Brown S, Cuschieri A. Ergonomic performance with crossed and uncrossed instruments in single-port laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 24:S493–S494. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2379-0. (20120) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]