Abstract

Childhood maltreatment has lasting negative effects throughout the lifespan. Early intervention research has demonstrated that these effects can be remediated through skill-based, family-centered interventions. However, less is known about plasticity during adolescence, and whether interventions are effective many years after children experience maltreatment. This study investigated this question by examining adolescent girls’ ability to make advantageous decisions in the face of risk using a validated decision-making task; performance on this task has been associated with key neural regions involved in affective processing and executive functioning. Maltreated foster girls (n = 92), randomly assigned at age 11 to either an intervention designed to prevent risk-taking behaviors or services as usual (SAU), and non-maltreated age and SES-matched girls living with their biological parent(s) (n = 80), completed a decision-making task (at age 15–17) that assessed risk-taking and sensitivity to expected value, an index of advantageous decision-making. Girls in the SAU condition demonstrated the greatest decision-making difficulties, primarily for risks to avoid losses. In the SAU group, frequency of neglect was related to greater difficulties in this area. Girls in the intervention condition with less neglect performed similarly to non-maltreated peers. This research suggests that early maltreatment may impact decision-making abilities into adolescence and that enriched environments during early adolescence provide a window of plasticity that may ameliorate these negative effects.

Keywords: Maltreatment, adolescence, females, risky decision-making, intervention, plasticity

Numerous studies have documented that, compared to other developmental periods, adolescents and young adults exhibit an increased prevalence of risk behaviors such as substance use, health-risking sexual behavior, and criminality (Arnett, 1992; Reyna & Farley, 2006; Steinberg, 2004). Increases in these behaviors have been linked to neurodevelopmental changes that co-occur with pubertal onset and continue into emerging adulthood (Crone & Dahl, 2012). Adolescents who have been involved in the child welfare system due to maltreatment are a particularly vulnerable population for engaging in such risk-taking behaviors (Garland et al., 2001). Overall, these youth have elevated rates, and earlier initiation, of delinquent acts, participation in HIV-risk behaviors (e.g., sex with multiple partners without protection), drug/alcohol use, and psychopathology (e.g., Aarons, Brown, Hough, Garland, & Wood, 2001; Cobb-Clark, Ryan, & Sartbayeva, 2012; Gramkowski et al., 2009).

Although maltreated youth of both genders show elevated rates of risk behaviors, girls with abuse histories tend to be at particular risk for a wide range of poor proximal and distal physical, social, and mental health outcomes that are linked to poor decision making (Cauffman, Feldman, Waterman, & Steiner, 1998; Leve & Chamberlain, 2005; Leve, Fisher, & DeGarmo, 2007; Teplin, Abram, McClelland, Dulcan, & Mericle, 2002). For example, studies consistently indicate that rates of childhood sexual and physical abuse are significantly higher for girls in the juvenile justice system than for boys, with rates from 3.5 to 10 times higher for girls than for boys (Johansson & Kempf-Leonard, 2009; Leve & Chamberlain, 2005). Moreover, the risk-taking decisions often made by maltreated girls (e.g., unprotected sex) can contribute to an increased prevalence of teen pregnancy, teen parenting, and deficits in parenting their own children, thus perpetuating the intergenerational transmission of risk behaviors (Leve, Kerr, & Harold, 2013). As a consequence of these behaviors, a growing amount of national and state public health costs are annually expended for mental health, educational, and justice system services (Fang, Brown, Florence, & Murphy, 2012). Notably, however, a considerable number of maltreated children exhibit resilience in the face of early adversity, evidence that maltreatment does not have a completely deterministic effect on outcomes (Cicchetti, 2013). One implication of this is that systematic interventions applied during sensitive periods of development may have potential to alter neurobiological pathways associated with problem behaviors, and have a sustained impact on improving outcomes for youth who experienced early maltreatment. For maltreated girls, such interventions may be particularly beneficial during adolescence, given their increased engagement in risk-taking behaviors during these years.

A key link in understanding pathways from early maltreatment to adolescent psychopathology versus adjustment is identifying how maltreated youth process decisions involving risks, and whether these decision-making processes can be modified. Such information could be instrumental in informing intervention strategies to reduce engagement in health-risking behaviors. The current study addresses this important gap, with a focus on adolescence as a potential sensitive period where neurocognitive processes such as decision making may be malleable.

Guided by past research in child maltreatment and behavioral decision theory, we compared how adolescent girls with prior maltreatment histories differed from their non-maltreated peers in how they made choices in the face of uncertain, or risky, outcomes (i.e., choosing an option with high outcome variability), including both risky decision-making to achieve gains and to avoid losses. We also examined the degree to which individuals effectively compared and utilized the expected value of each choice option, which can signal whether to approach or avoid a choice, to guide their choices (Weller, Levin, Shiv, & Bechara, 2007). Second, we assessed the effects of an earlier intervention designed to reduce risk-taking behaviors (e.g., unprotected sex) on decision-making abilities. Early childhood intervention research has demonstrated that some of the harmful effects of maltreatment on neurocognitive development can be remediated through skill-based, family-centered interventions (Dozier, Peloso, Lewis, Laurenceau, & Levine, 2008; Fisher, Gunnar, Dozier, Bruce & Pears, 2006; Gunnar, Fisher,& The Early Experience, Stress, and Prevention Network, 2006). However, less is known about neural plasticity later in development, and whether similar interventions are effective many years after children experience maltreatment. Finally, we tested the degree to which the frequency of neglect moderated the effects of the intervention. If the neglect experiences result in less plasticity (reduced intervention effects), this would suggest that interventions for neglected populations need to be delivered earlier in development, when malleability of neurocognitive functions may be more feasible.

Neurocognitive Development During Adolescence and Associations With Risky Decision-Making

Theories bridging typical neurodevelopmental patterns with decision-making research have suggested that the spike in risk-taking behaviors observed during adolescence may, in part, be related to the functioning of still-developing neural systems. These theories have focused on the development of two primary neural systems: the limbic system (especially the ventral striatum and amygdala) and a cognitive control system involving the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (Crone & Dahl, 2012). Specifically, imaging studies have found increased activation in the ventral striatum and amygdala, areas implicated in tying emotional salience to stimuli, in response to both threat and reward stimuli (e.g., Galvan, Hare, Voss, Glover, & Casey, 2006; Guyer et al., 2008) during adolescence. These findings suggest that adolescence is typically a time of increased emotion processing, which has implications for the valuation, and subsequent comparison, of choice options. For instance, using a task involving an opportunity to accept (vs. not accept) a 50/50 gamble to win a certain amount (otherwise lose), Barkley-Levenson and Galvan (2014) found adolescents, compared to adults, demonstrated increased bilateral activation in the ventral striatum as the expected value of the choice increased, suggesting a hyper-activated reward component of a broader neural valuation system (Bartha, McGuire, & Kable, 2013).

This increased emotional intensification may present issues for a developing cognitive control system, which is vital for inhibitory control and goal-directed behaviors (Casey, Jones, & Somerville, 2011; Crone & Dahl, 2012). Immature executive function components in adolescence, such as inhibitory control, in part, are believed to account for increased sensitivity to both losses and gains (Ernst et al., 2005; Galvan et al., 2006; Huizenga, Crone, & Jansen, 2007). Inhibitory control has been shown to be associated with increased risk taking behaviors, and as a consequence, poorer social, academic, and health outcomes (Romer, 2010). Moreover, lower reported inhibitory control has been associated with lower ability in following decision rules to arrive at an answer and a greater miscalibration between one’s knowledge of a topic and one’s confidence level of that knowledge (Weller, Levin, Rose, & Bossard, 2012).

Maltreatment Experiences and Neurocognitive Development

The experience of childhood maltreatment (e.g., abuse and neglect) has been shown to have long-term effects on neurocognitive functioning and emotional regulation (Beers & De Bellis, 2002; Cicchetti, Rogosch, Howe, & Toth, 2010; Lewis, Dozier, Ackerman, & Sepulveda-Kozakowski, 2007; Pollack, 2010). Additionally, maltreated children frequently demonstrate dysregulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, a system that mediates reactions to environmental stressors (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2001). Chronic dysregulation of the HPA axis is believed to have profound structural and functional neurological impacts on the developing brain (Gunnar, et al., 2006; Pechtel & Pizzagalli, 2011). Specifically, early maltreatment experiences in humans have been associated with structural and functional deficits in brain areas with bi-directional connections with the HPA system, including the amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus, and the medial and lateral prefrontal cortex (e.g., Fisher, Stoolmiller, Gunnar, & Burraston, 2007; Gunnar et al., 2006). For instance, researchers have found evidence for more diffuse brain activation on executive functioning tasks in maltreated children (Fisher, Bruce, Abdullaev, Mannering, & Pears, 2011). Also, child maltreatment is associated with smaller hippocampal volumes and decreased cortical volumes, both white and gray matter, in the prefrontal cortex (Carrion et al., 2001; Carrion, Weems, Richert, Hoffman, & Reiss, 2010; De Bellis et al., 2002). In another study, McCrory et al. (2011) found that maltreated children increased activation of the anterior insula, which is believed to support interactions between perceived threat signals mediated by amygdala activity and arousal that lead to subjective emotionality (Craig, Chen, Bandy, & Reiman, 2000) in response to threat stimuli. Teicher, Anderson, Ohashi, and Polcari (2013) found that the insula may be a central neural communication hub for adults who reported experiencing childhood maltreatment.

Risky Decision Making in Maltreated Youth

These functional and structural neurocognitive differences observed in individuals with prior maltreatment experiences are especially important because the integrity and maturity of these neural structures are believed to be vital for making advantageous decisions in the face of uncertain outcomes (Bartha et al., 2013; Levin et al., 2012; Mohr, Biele, & Heekeren, 2010). For example, lesions to the medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala have been shown to result in alterations in decision-making abilities on laboratory tasks (Bechara, Damasio, Demasio, & Lee, 1999; Weller, et al., 2007). Additionally, the insula is believed to hold a prominent role in the processing of risky decisions, especially ones that involve potential losses (Mohr et al., 2010; Rolls, McCabe, & Redoute, 2008; Singer, Critchley, & Presuchoff, 2009; Weller, Levin, Shiv, & Bechara, 2009).

Despite the abundance of studies suggesting an association between early adversity and risk behaviors, to date, very few studies have examined the decision-making abilities of maltreated children. In one study, Guyer et al. (2006) used a “Wheel of Fortune” task (Ernst et al., 2004), which asked participants to make a choice between a lower-reward/high probability win and a greater reward with a lower probability of success found. Although they found that maltreated children (8–14 years) showed similar behavioral decision-making processes (i.e., the choices that were made) as same-age non-maltreated youth, maltreated youth were quicker to select a risky option, suggesting a possible alteration in the reward processing system.

In a prior study by our research group on this same topic, Weller and Fisher (2013) found evidence that risk-taking tendencies may be a function of whether the choice involved achieving a potential gain or avoiding a potential loss. In particular, using the “Cups” Task paradigm, a task that has been shown to be sensitive to lesions of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, anterior insula, and amygdala (Weller, et al., 2007, 2009), Weller and Fisher found no behavioral differences between children (10–12 years) with maltreatment histories and non-maltreated peers when the risks involved potential gains. In contrast, they found that maltreated children showed elevated risk taking when presented with decisions involving avoiding a potential loss. Importantly, the maltreated children demonstrated a lower ability to make choices based on the relative expected value between choice options (referred to hereafter as EV Sensitivity) in loss-related risk taking, but no differences in EV sensitivity for potential gains. Notably, these deficits in EV sensitivity were found to result from a relative insensitivity to increases in the magnitude of the potential loss, which should reduce risk-tendencies, rather than insensitivity to changes in the likelihood that a negative outcome would be realized (i.e. probability level). This finding provides support for the notion that the observed decision-making differences were not due to general deficits in knowledge about probabilities. From a process-oriented perspective, we also found that maltreated children were slower to make a choice, highlighting the possibility that maltreated children may have greater difficulty disengaging from the heightened emotional arousal associated with uncertainty. Together, these findings suggest that the neurocognitive systems involved in decision making are affected by maltreatment experiences early in development, but it is unknown whether such effects persist into later adolescence, and whether they can be remediated via intervention.

Risky Decision Making: A Behavioral Decision-Making Perspective

Although clinical and lay definitions of the term “risk” often connote a behavior that involves danger or likelihood of a negative outcome, risk-taking can indeed be beneficial in certain circumstances; for instance, risks sometimes present opportunities for personal growth. Thus, an empirical investigation of risk must consider not only one’s propensity to take risks, but also incorporate one’s ability to discern when it is advisable to take, and when to avoid, a risk.

One metric to help guide decisions is to choose the option with the more favorable expected value (EV), expressed as the product of the probability of an outcome occurring and the magnitude of that outcome. Choosing such options will lead to better outcomes over the long-run according to normative models of rationality (von Neumann & Morgenstern, 1947). Thus, greater EV sensitivity reflects a tendency to select a risky option when its EV is favorable to that of the sure option, and to avoid taking a risk when the EV favors the sure option. Across the lifespan, the ability to make EV-sensitive judgments is believed to follow an inverted-U pattern which gradually increases until adulthood and then declines in the elderly (Weller, et al., 2011).

However, the ability to make choices based on EV may be especially difficult for decisions involving potential losses. A robust finding in the behavioral decision literature has been that individuals prefer risk-averse choices when a risk involves potential gains, and are risk-seeking when the choice involves avoiding a potential loss of an equal amount (Kahneman and & Tversky, 1979). In this sense, losses are believed to “loom larger than gains.” Put differently, negative information tends to be over-weighted relative to positive information, which may lead to neglect for the probability that the negative outcome may actually occur (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, 2001; Rottenstreich & Hsee, 2001).

From a developmental perspective, sensitivity to loss appears have a later and/or slower course. For example, Weller et al. (2011) found that 8–11 year old children took more risks to achieve gains than adults, but showed no differences in their ability to distinguish advantageous risks from disadvantageous ones. However, for decisions involving potential losses, the children showed a reduced ability to make EV-based decisions to avoid losses, suggesting that EV sensitivity to avoid losses may develop later than EV sensitivity for potential gains (Schlottmann & Tring, 2005). This discrepancy between the two EV sensitivity domains also introduces the possibility that there may be different sensitive periods and malleability for these two facets of neurocognitive development.

Yechiam and Hochman’s (2013) Attention Allocation model proposes a potential explanation for these differences in EV domain. Risks involving potential losses have been shown to increase autonomic arousal, generate more perceived conflict, and increase cortical activation (Gehring & Willoughby, 2002; Sokol-Hessner et al., 2009). The Attention Allocation model is consistent with emerging work in decision neuroscience suggesting that potential losses may recruit a more complex neural system than for choices that involve potential gains (Mohr et al., 2010; Kuhnen & Knutson, 2007).

The Attention Allocation model has direct implications for maltreated adolescents’ decision making. If losses loom larger than gains in terms of their emotional impact, they may present a greater potential for affective engagement and as a result, more strongly orient an adolescent to the potential magnitude of the loss. To make an EV-based judgment when considering potential losses, the ability to disengage from the emotional information and approach the problem more deliberatively, presumably mediated by the cognitive control system, becomes vital. Given that maltreated children often demonstrate functional difficulties in the cognitive control system (Bryck & Fisher, 2012; Fisher et al., 2011; Merz, McCall, & Groza, 2013; Span et al., 2012), this ability may be especially compromised, and lead to less EV-based choices.

The Potential for Plasticity During Adolescence

Although the adverse effects of maltreatment have been widely documented, numerous studies have documented that strength-based interventions can improve behavioral and neurodevelopmental outcomes for youth who have experienced maltreatment (Leve et al., 2012). A review of evidence-based intervention for youth in foster care identified three effective interventions for this population in early childhood, four in middle childhood, and one in adolescence (Leve et al., 2012), with numerous other promising programs across development. All three of the early childhood interventions have demonstrated effects on neurobiological systems in maltreated samples (Dozier et al., 2008; Fisher & Stoolmiller, 2008; Fox, Almas, Degnan, Nelson & Neanah, 2011). In addition, there is strong evidence from the English-Romanian adoption study that neurobiological systems are more malleable when a child is removed from an orphanage and adopted into a family within the first years of life (Rutter, 2010). In contrast to the literature on early childhood interventions, we are not aware of any middle childhood or adolescent randomized intervention trial that has shown evidence of malleability in complex cognitive abilities such as decision-making, which are presumed to be dependent on the integrity of the same neurobiological systems, for maltreated youth. This raises the critical question as to the degree to which the effects of maltreatment on neurocognitive development are possible if systematic interventions and supports are not implemented until middle childhood or adolescence.

Despite the dearth of research examining this question, there may be potential for a sensitive period in neuroplasticity during the transition to middle school, because periods of transition and change can offer opportunities for resilience (Cicchetti, 2013; Rutter, 2000, 2007). Middle school is a challenging period for students in general; decreases in academic achievement, positive peer relations, self-esteem, perceived competence, and school liking, and increases in psychological distress have often been documented across middle school (e.g., Cantin & Boivin, 2004; Chung, Elias, & Schneider, 1998; Fenzel, 2000). Children who perform poorly across both elementary school and middle school are at the highest risk for negative outcomes in future years, such as dropping out of school (Alexander, Entwisle, & Kabbini, 2001). The middle school period also coincides with the onset of puberty, which has been associated with increases in sensation-seeking tendencies (Steinberg, 2008; Forbes & Dahl, 2010). Numerous studies have documented that youth who experience pubertal timing at an earlier age are at increased risk for a host of psychopathological outcomes during adolescence, including increased delinquency (Ge, Natsuaki, Jin, & Biehl, 2011). Poor outcomes associated with pubertal timing may be particularly pronounced among maltreated girls (e.g., Mendle, Leve, Van Ryzin, Natsuaki, & Ge, 2011; Natsuaki, Leve, & Mendle, 2011).

Resilience occurs through ordinary processes involving the operation of basic human adaptational systems, even in the face of adversity (Masten, 2001). These adaptational systems include family-level characteristics, such as close relationships with involved and caring adults. Through adaptational systems such as involved caregiving, interventions could enhance child resilience by directly adding sufficient positive experiences to the child’s life to offset the adversity (Cicchetti, 2013; Garmezy, Masten, & Tellegen, 1984; Masten, 2001). An earlier study using the same sample of girls as in the current study provided support for this assertion: A family-based, skill building intervention lowered maltreated girls’ substance use at age 14 (Kim & Leve, 2011). The current study extends this work to age 16 and examines decision-making skills as the outcome of interest, drawing on evidence that decision-making skills are mediated by underlying neural processes believed to be altered by the experience of maltreatment. We include a focus on the impact of neglect because, compared to physical and sexual abuse, neglect is more pervasive among maltreated samples, and has comparable deleterious effects on physical, cognitive, and mental well-being (Lissau & Sorenson, 1994; Johnson, Cohen, Kasen, Smailes, & Brook, 2001; Montgomery, Bartley, & Wilkenson, 1997; Trickett & McBride-Chan, 1995).

This Study

In this study, we examined the plasticity of neurocognitive functioning by comparing the decision-making performance in three groups of adolescent girls: (1) a maltreated sample who was randomly assigned to receive a family-based, skill-focused foster care intervention; (2) a maltreated sample who was randomly assigned to receive foster care services-as-usual (SAU); and (3) a non-maltreated, low-income community comparison sample matched for age with the maltreated girls. The inclusion of a low-income comparison group (versus a middle-income group) provides an advantage by demonstrating that the effects of maltreatment may be separable from the adverse conditions that low socioeconomic status may have on decision-making (Cicchetti, 2013). To measure risky decision-making, we used the expanded Cups Task paradigm (Weller et al., 2007). The Cups task separately measures risky decision-making to achieve gains and risk-taking to avoid losses. Because of its design, the Cups Task allows for the assessment of EV sensitivity for both types of risky choices.

Based on past research and theory, we first hypothesized that the maltreated girls would show greater levels of overall risk taking compared to the non-maltreated community girls. Second, to examine neural plasticity during the adolescent period, we hypothesized that the intervention that occurred in early adolescence would attenuate differences between maltreated girls and their non-maltreated peers approximately 5 years later. Specifically, we hypothesized that girls randomly assigned to a traditional foster care condition (SAU) would demonstrate greater risk taking and lower sensitivity to the relative expected values between choice options than girls who received the foster care intervention. In contrast, we predicted that girls randomly assigned to the foster care intervention condition would demonstrate a pattern similar to that observed in their non-maltreated peers. Third, to examine the boundaries around the potential for neural plasticity, we hypothesized that the effectiveness of the intervention would be moderated by the degree of neglect that the adolescent had experienced during early childhood. Specifically, we predicted that girls in the SAU condition who experienced greater levels of neglect would show the greatest decision-making impairments.

Method

Participants

Adolescent girls (median age = 16.47 years; n = 92) with a history of maltreatment and prior involvement in the Child Welfare System in the state of Oregon were recruited as part of an ongoing longitudinal study. Girls had been originally recruited into the study 5 years prior, when they were transitioning to middle school (Chamberlain, Leve, & Smith, 2006). To be successfully recruited for the original study, the caseworker, the foster family, and the child had to consent/assent for participation. Additional recruitment details are provided elsewhere (Kim & Leve, 2011).

On average, the girls were first placed in foster care at age 7.63 years (SD = 3.14), and had an average of 5.84 (SD = 5.01) prior placements based on official child welfare records. Overall, 56% of girls in the sample had a documented history of physical abuse, 67% sexual abuse, and 78% neglect. Approximately, 40% of girls had a documented history of both physical and sexual abuse, and 32% reported all three types of maltreatment. The ethnicity breakdown of the sample was 63% European American, 9% African American, 10% Latino, 4% Native American, and 14% multiracial.

Additionally, at-risk girls from the community were recruited as a non-maltreated, low income, community comparison (CC) group. They were age- and SES matched to the maltreated girls. To ensure comparability with the maltreatment sample, the CC sample was recruited in the same two counties as the maltreated girls, through flyers posted in public places, inserts in the local newspapers, ads on Craigslist, and contacts with local youth groups and community organizations. A five-minute telephone screening was conducted to determine eligibility for the study: (1) age-matched to the maltreatment sample; (2) total annual household income $40,000 or less; (3), parent education less than a college degree; and (4) no history of child welfare system involvement in the family. Of 85 CC girls who met the recruitment criteria and completed a baseline assessment, 80 participated in the present study. The ethnicity breakdown of the CC girls was 58% European American, 7% African American, 17% Latino, 12% multiracial and 2% other.

Intervention Condition

Participants were randomly assigned to foster care services-as-usual (SAU) or the Middle School Success intervention (MSS). The MSS intervention began during the summer prior to middle school entry, with the goal of preventing risk-taking behaviors such as delinquency, substance use, and related problems (Chamberlain, Price, et al., 2006). The intervention consisted of three primary components: (a) six sessions of group-based caregiver management training for the foster parents prior to middle school entry, (b) six sessions of group-based skill-building sessions for the girls prior to middle school entry, and (c) weekly group-based caregiver management training for the foster parents and weekly one-on-one skills training for the girl during the first year of middle school. Prior to middle school, the groups met twice a week for 3 weeks, with approximately seven participants in each group. The caregiver sessions were led by one facilitator and one co-facilitator. The girl group sessions were led by one facilitator and three assistants to allow a high staff-to-girl ratio (1:2) for individualized attention, one-on-one modeling/practicing of new skills, and frequent reinforcement of positive behaviors. The follow-up intervention services (i.e., ongoing training and support during the first year of middle school) were provided to the caregivers and girls in the intervention group once a week for two hours (foster parent meeting; one-on-one session for girls). The interventionists were supervised weekly, where videotaped sessions were reviewed and feedback was provided to maintain the fidelity of the clinical model (Chamberlain, Price et al., 2006).

The curriculum for the foster parent groups focused on developing a behavioral reinforcement system to encourage adaptive behaviors across home, school, and community settings. Weekly home practice assignments were provided to encourage foster parents to apply new skills. On average, participants completed 5.62 of the 6 summer sessions (SD = .99) and 20 weekly follow-up sessions (SD = 10.4). When a participant missed a session, the interventionist either went to the families’ home to deliver the content in person or delivered the content via a telephone call. The curriculum for the summer group sessions for girls were designed to prepare the girls for the middle school transition by increasing their social skills for establishing and maintaining positive relationships with peers, increasing their self-confidence, and decreasing their receptivity to initiation from deviant peers. The group structure typically included an introduction to the session topic, role plays, and a game or activity during which girls practiced the new skill. Participation rates mirrored those of their caregivers. The individual skills coaching sessions during the first year of middle school continued to focus on establishing and maintaining positive peer relations, increasing knowledge of accurate norms for problem behaviors, and increasing self-competence in academic and social areas. Approximately 40 sessions were offered and the average attendance rate was 56.4% (SD = 28.5%). Additional information regarding the intervention can be found elsewhere (Kim & Leve, 2011).

Control Condition

The girls and caregivers in the SAU control condition received the usual services provided by the child welfare system, including services such as referrals to individual or family therapy, parenting classes for biological parents, and case monitoring. Sixty two percent of girls in the control condition received individual counseling, 20% received family counseling, 22% received group counseling, 30% received mentoring, 37% received psychiatric support, and 40% received other counseling or therapy services (e.g., school counseling, academic support) during the 1st year of middle school. Note that many girls received more than one service, and therefore the percentages listed above exceed 100%. Child welfare caseworkers managed each case and were responsible for making all decisions on referrals to community resources, including individual and family therapy and parenting classes.

Measures

Decision-making task

Risky decision making for gains and losses were measured using the Cups Task paradigm (Levin & Hart, 2003; Weller et al., 2007; see for detailed illustration of the task, see Weller & Fisher, 2013, Figure 1). In this task, participants see two arrays of “Cups” on each side of the screen. One array is identified as the sure side, in which one quarter will be gained/lost for whichever cup is selected (i.e. “You will win [lose] $.25 for sure). The other array involves a “risky” choice option: The selection of one cup will lead to a designated number of quarters gained/lost and the other cups will lead to no gain/loss (i.e., You may win [lose] “$X” or nothing. The risky option always involves the opportunity to win [lose] more money than if the participant chooses the sure option. For each gain trial, participants are asked to make a choice between the sure option and the risky option. Participants select a cup from either side and are given feedback on the result of their choice, indicated by the addition, or subtraction of coins from a “bank” depicted at the bottom of the screen; at the beginning of each trial, the bank clears, and thus, running total indicating cumulative performance throughout the task is not provided. To both avoid ending up with negative scores and to increase the salience of potential losses, participants start each loss trial with enough quarters in their bank to ensure a positive balance (presented at the bottom of the screen).

Figure 1.

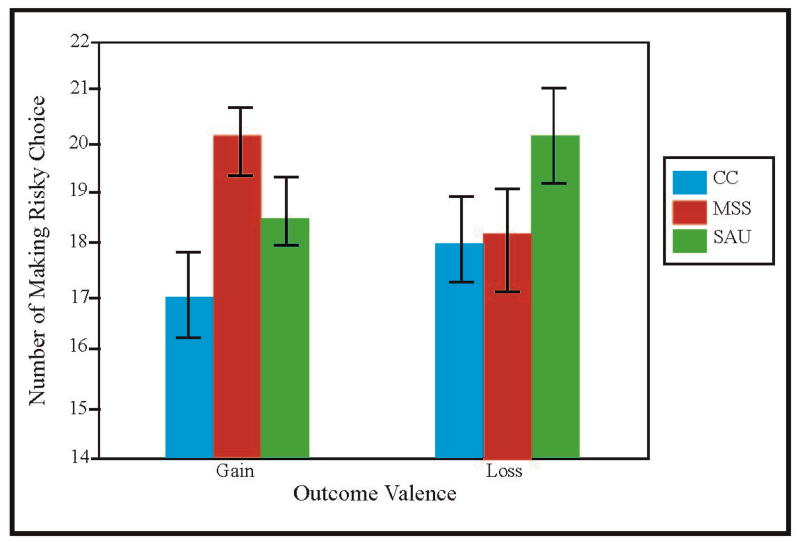

Domain-specific Risk-Taking Differences between Maltreated Girls and Community Controls.

The task consists of 54 trials representing three trials each of all combinations of two domains (gain/loss), probability level (i.e., 2/3/5 cups) and outcome magnitude for the risky option (2/3/5 quarters). The gain and loss trials are presented as blocks, counterbalanced in order across all participants. Within each domain, each probability X outcome combination block is randomly presented. A random process with p = 1/(number of cups) determines whether the risky choice led to a gain/loss. When the participant completes all 54 trials, the total amount won appears on the screen. Participants receive a final score at the end of the task indicating how much they earned, and were then compensated for their task performance by receiving a small cash bonus.

For correlation analyses, risk-taking for gains and losses were calculated by adding the number of risky choices made for each domain, leading to a maximum possible score of 27 in each domain. However, in the main analyses, risk-taking is conceptualized as a binary variable indicating whether the participant chose the risky option on an individual trial (0 = safe, 1= risky choice). Similarly, for correlational analyses, EV Sensitivity for each domain was calculated by subtracting the proportion of risky choices made when the EV actually favored the sure choice (i.e., a Risk-disadvantageous trial) from the proportion of risky choices made on trials in which the EV favored the risky option (i.e., a Risk-Advantageous trial). Zero values reflected equal EV between choice options. Thus, more positive EV values reflected more favorable long-term consequences (i.e., EV sensitivity = 1.0 would indicate that a participant always selected the option that had the greater expected value).1 In the main analysis, EV level is treated as a covariate; each individual choice is associated with the corresponding relative EV between choice options ascribed to it, calculated by the equation, EV = outcomerisky X probabilityWin(loss) - $.25 (or + $.25 for the loss domain).

Motivation check

After completing the Cups Task, participants were asked to complete four items that assessed motivation to perform well on the task (e.g., “Doing well [on the task] was important to me”). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1= strongly agree, 5= strongly disagree). We created a summed composite variable (α=.81).

Covariates

Crystallized intelligence

To control for the effects of verbal intelligence on decision-making performance, girls completed the Vocabulary subscale of the Shipley Institute of Living Scale (Shipley, 1940). This measure contains 40 multiple-choice items that involved matching a target word with its synonym, with items becoming more difficult as the task progressed. Despite its age and short length, the Shipley Vocabulary strongly correlates with more modern intelligence measures (Zachary, Paulson, & Gorsuch, 1985). We used the raw Vocabulary scores as an index of vocabulary knowledge (α =.79; Mcorrect = 22.17, SD = 5.81; range = 9 to 35 correct).

Age of menarche

Because of the multi-wave nature of this project, we were able to report the age of menarche as a measure of pubertal timing for both maltreated groups. Research has suggested that pubertal timing may predict increased risk taking more precisely than chronological age (Steinberg, 2008). Because this variable was unavailable for the CC girls, we include this variable as a covariate only when we compared the two maltreated groups. The median age of reported menarche was 12 years.

Frequency of neglect

The girls’ cumulative maltreatment experiences at enrollment into the original study (age 11) were drawn from child welfare case records that were coded using a modified version of the Maltreatment Classification System (MCS; Barnett, Manly, & Cicchetti, 1993). We also confirmed via child welfare records that no girls in the CC group had a maltreatment incident on record. Coders examined child welfare case records to identify incidents of maltreatment, which (1) had to match the MCS definitions of maltreatment and (2) had to be reported by a mandatory reporter or verified by the child welfare system caseworker. Case files included all information on incidents of childhood maltreatment and family history available to child welfare at the time of the study. Training in the use of the MCS was initially conducted by one of its authors (Manly). Because of the complexity of the coding system, two-thirds of the cases were double coded and then discussed to attain a final consensus rating. Interrater reliability was computed from the 67% of files that were double-coded (prior to consensus discussions). The average percent agreement for the number of neglect incidents was acceptable (82%). In addition, coders attained high levels of agreement (81%) about the total number of incidents per case. For each girl, we used the number of incidences of neglect, calculated as the number of incidences of emotional abuse, failure to provide care, lack of supervision, and moral/legal maltreatment. Overall, the mean number of reported neglect incidents prior to study entry was 7.07 (SD = 4.32). 78% of girls had at least one incident of neglect.

Intervention condition

Treatment groups were dummy-coded in the main analyses, with the CC group as the reference group. When comparing MSS and SAU groups only, we used contrast coding (MSS = 1, SAU = −1).

Results

Group-Level Differences for Vocabulary Scores, Maltreatment Experiences, and Task Motivation

We present the group-level descriptive statistics for the variables of interest in Table 1. A one-way ANOVA found no group differences on Shipley Vocabulary scores, F (2, 169) = 2.05, p =.13. For the SAU and MSS groups, we observed no significant differences in reported age of menarche t (85) = .03, p = .27. However, there was a significant difference between groups with respect to the number of reported neglect incidents. Those in the SAU group had experienced more neglect (M = 8.49, SD = 4.63) than the MSS group (M = 5.10, SD = 3.20), t (90) = 4.03, p <.001. There were no significant differences between intervention groups on the number of prior placements, t (90) =.69, p =.49, or the presence of prior sexual abuse, χ2(1) =.20, p =.82, or prior physical abuse, χ2 (1) = 1.10, p =.40.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Variables of Interest

| Variable Names | CC | SAU | MSS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age (median years) | 16.24 | 1.18 | 16.34 | .93 | 16.68 | .70 |

| Vocabulary | 22.95 | 5.74 | 20.85 | 5.54 | 22.38 | 5.67 |

| Frequency of Neglect | – | 8.49 | 4.63 | 5.13 | 3.20 | |

| Age of Menarche | – | 12.00 | .98 | 11.99 | 1.00 | |

Note. CC = Community comparison group; SAU = Foster care services as usual; MSS = Middle School Success Intervention group

Motivation check

We also tested whether if there were motivational differences to perform well on the Cups task between the CC, SAU, and MSS groups. A one-way ANOVA revealed no significant motivational differences between groups, F (2,169) = 1.72, p >.10. There were no differences in motivation between SAU (M = 8.28, SD =3.44) and MSS (M = 8.51, SD = 3.10), d =.07.

Correlations Between Covariates and Risky-Decision Making Indices

Next, we tested the correlations between the study covariates and the indices of risky decision-making (Risk-taking and EV Sensitivity). As shown in Table 2, we did not find a significant association between Vocabulary scores and domain-specific risk taking, but found that greater Vocabulary scores were associated with greater EV sensitivity. For the MSS and SAU girls, neither age of menarche onset nor the number of reported neglect experiences significantly correlated with risk-taking or EV sensitivity in either domain.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations Between Study Variables

| Variable Names | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Shipley Vocabulary | – | ||||||

| 2. Age of Menarche | −.06 | – | |||||

| 3. Frequency of Neglect | −.10 | .12 | – | ||||

| 4. Risk Taking Gains | −.08 | .11 | −.03 | – | |||

| 5. Risk Taking Losses | .08 | −.17 | .06 | .23** | – | ||

| 6. EV Sensitivity – Gains | .20** | −.01 | .01 | −.22** | .08 | – | |

| 7. EV Sensitivity – Losses | .15* | .04 | −.13 | −.16* | −.01 | .15* | – |

Note. Ns ranged from 92–172. Age of menarche and frequency of neglect were only assessed for the maltreated sample of girls.

p<.10.

p < .05.

p < .01 (2-tailed).

Risky Decision Making

To test group differences in risky decision making, we conducted a Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE; Liang & Zeger, 1986) analysis that allows for a within-subjects analysis of participants’ decision behavior for each trial. We fit a binomial response model using a logit-link function using each choice (0 = safe, 1 = risky) as the dependent measure. An exchangeable covariance matrix was used, which assumes non-zero homogeneous within-subject correlations across responses. Parameter estimates were achieved using hybrid maximum likelihood estimation. We began the analyses with a full-factorial model regressing choice on domain (gain/loss), EV, and dummy-coded treatment groups (SAU/MSS/CC). EV was mean-centered. Shipley vocabulary scores were included as a covariate in the model.

As shown in Table 3, we found a main effect for domain; participants took more risks to avoid losses than to achieve gains regardless of the group status, consistent with the “reflection” or “preference shift” effects (Levin, Gaeth, Schreiber, & Lauriola, 2002; Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). Additionally, we found a main effect for EV level; individuals were more likely to make a risky choice as its EV became more favorable relative to the EV of riskless option. As with other studies using the Cups Task, we observed a significant EV level X Domain interaction, in which participants demonstrated greater EV sensitivity for decisions involving risky gains (vs. risky losses). Shipley scores did not account for variance in overall risk-taking.

Table 3.

Group Differences in Cups Task Performance-GEE Models

| Parameter | 95% Wald Confidence Interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Lower | Upper | Wald χ2 | |

| Vocabulary | .03 | .02 | −.02 | .07 | 1.60 |

| SAU Group | .32 | .08 | .16 | .48 | 14.77** |

| MSS Group | .02 | .08 | −.14 | .18 | .07 |

| Domain | −.31 | .07 | −.44 | −.18 | 21.83** |

| EV | 1.91 | .29 | 1.33 | 2.48 | 42.27** |

| Domain X EV | 1.97 | .46 | 1.08 | 2.87 | 18.61** |

| SAU Group X domain | −.04 | .11 | −.26 | .18 | .12 |

| SAU Group X EV | −1.26 | .50 | −2.25 | −.28 | 6.29** |

| MSS Group X domain | .54 | .11 | .32 | .76 | 22.34** |

| MSS Group X EV | −.15 | .49 | −1.11 | .81 | .10 |

| SAU Group X Domain X EV | 1.10 | .78 | −.43 | 2.63 | 1.99 |

| MSS Group X Domain X EV | −1.07 | .78 | −2.59 | .46 | 1.88 |

Note.

p < .01.

Irrespective of domain, the SAU girls demonstrated greater overall risk-taking. In comparison, we did not find a significant main effect on risk-taking for the MSS group. However, we observed a significant Domain X MSS Group interaction revealed that the MSS group was more likely to take risks to achieve gains than the CC group (see Figure 1).

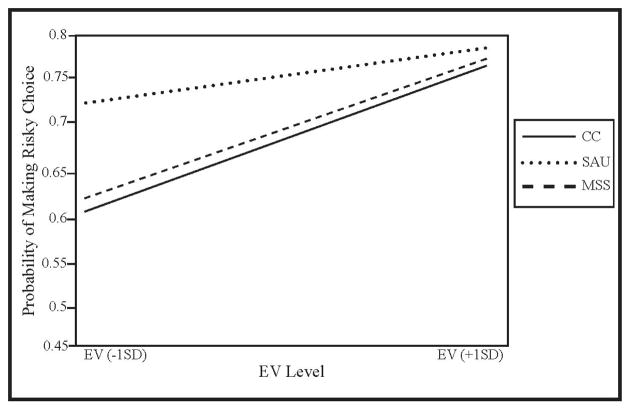

As illustrated in Figure 2, we found a significant EV X SAU Group interaction. That is, SAU girls were less able to adjust their choices as the EV of the risky option became less favorable, leading to excessive risk-taking when the EV signaled to avoid the risks. We did not observe a similar effect for the MSS Group. The three-way Domain X EV X Group interactions were not significant.

Figure 2.

Overall EV-Sensitivity Differences between Maltreated Girls and Community Controls. Model-based estimates are represented.

Comparison of Treatment Groups’ Sensitivity to Probability Level and Outcome Magnitude

As suggested in Figures 1 and 2, the SAU group demonstrated greater risk-taking and lower EV sensitivity than the MSS group, especially for risks involving potential losses. Because group status was dummy-coded in the prior analysis, we did not directly compare treatment groups. To further confirm and explain the potential mechanisms for these differences, we examined how SAU and MSS girls differentially utilized probability and outcome information for risks involving potential gains and losses. This analysis served to replicate Weller and Fisher’s (2013) results suggesting that EV differences observed in maltreated youth were related to insensitivity to changes in outcome magnitude especially in the loss domain. Thus, we predicted that SAU girls would demonstrate lower sensitivity to outcome magnitude than MSS girls. To test this hypothesis, we conducted two parallel GEE analyses in which regressed choice on probability of choosing the winning or losing cup, outcome magnitude of the risky choice, group status (SAU = −1; MSS = 1), vocabulary scores, and age of menarche. Probability level and outcome magnitude were mean-centered.

The results of these analyses are shown in Table 4. For both the gain and loss domain, neither covariate significantly accounted for variance in choice, holding other variables constant. As expected for decisions involving risky gains, as the probability level increased from a 20% chance to win (i.e., 5 cups were presented) to a 50% chance (i.e. 2 cups presented), participants were more likely to choose the risky option, holding other variable constant. Also, as the outcome magnitude of the risky choice increased, participants were more likely to make a risky choice. The higher-order interactions were not significant.

Table 4.

Effects of Probability and Outcome Magnitude on Risky Decision Making as a Function of Intervention Group

| Parameter | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | Lower | Upper | Wald χ² | |

| Gain Domain | |||||

| Age of Menarche | .09 | .10 | −.10 | .29 | 0.83 |

| Vocabulary | −.03 | .10 | −.23 | .17 | 0.00 |

| Group(MSS=1; SAU = −1) | .11 | .10 | −.10 | .31 | 1.01 |

| Probability | 2.72 | .37 | 2.00 | 3.44 | 54.78** |

| Outcome | 1.16 | .15 | .88 | 1.45 | 61.40** |

| Group Probability | −.54 | .37 | −1.26 | .18 | 2.17 |

| Group x Outcome | −.16 | .15 | −.45 | .13 | 1.44 |

| Loss Domain | |||||

| Age of Menarche | −.20 | .14 | −.47 | .07 | 2.08 |

| Vocabulary | .17 | .14 | −.11 | .45 | 1.48 |

| Group | −.15 | .14 | −.42 | .12 | 1.18 |

| Probability | −.50 | .31 | −1.11 | .10 | 2.65* |

| Outcome | .63 | .12 | .39 | .87 | 26.43** |

| Group x Probability | −.20 | .31 | −.80 | .41 | 0.40 |

| Group x Outcome | .34 | .12 | .10 | .57 | 7.71** |

p = .05,

p < .01

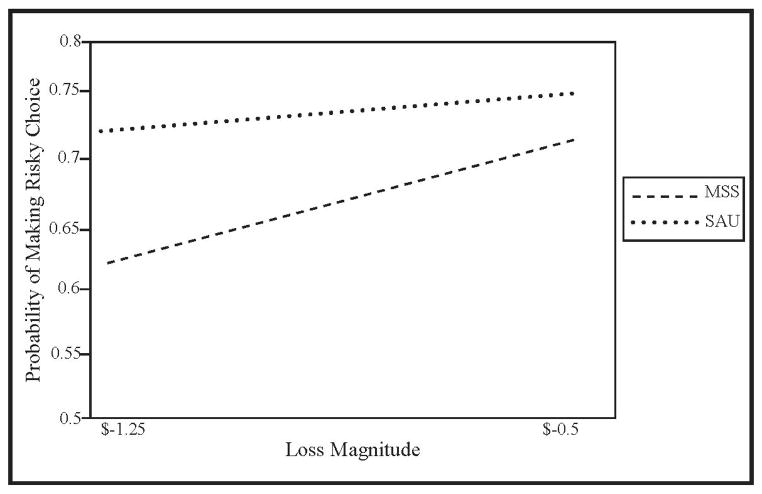

For risky losses, we found a significant effect for probability level. On average, participants made fewer risky choices as the probability of not choosing the losing cup became greater. Also, we found that as the potential loss associated with the risky option became greater, participants were more likely to avoid taking risks. However, a Group X Outcome Magnitude interaction (see Figure 3) demonstrated that the MSS group was more sensitive to relative changes in the outcome magnitude of the risky choice. In contrast, SAU girls were relatively insensitive to these differences. The Group X Probability interaction was not significant.

Figure 3.

Proportion of risky choices as a function of outcome magnitude and intervention group status. Model-based estimates are represented.

Neglect as a Moderator of Intervention Effects

As a final analysis, we tested the degree to which frequency of neglect incidences may impact the long-term efficacy of this intervention on decision-making performance. In this analysis, we regressed choice on EV level, domain, the number of reported neglect incidences, vocabulary scores (and interactions with Cups Task), and age of menarche (see Table 5 for results).

Table 5.

Effects of neglect as a moderator of Foster Group Treatment Status on Risky Decision-making

| Parameter | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Lower | Upper | Wald χ² | |

| Age of Menarche | −.15 | .10 | −.34 | .04 | 2.30 |

| Vocabulary | .05 | .10 | −.14 | .25 | .27 |

| Neglect (# of reports) | .04 | .12 | −.20 | .28 | .11 |

| Group (SAU/MSS) | −.08 | .11 | −.31 | .14 | .50 |

| EV | .96 | .30 | .37 | 1.55 | 10.06** |

| Domain | −.04 | .07 | −.17 | .10 | .26 |

| Domain X EV | 2.34 | .48 | 1.40 | 3.28 | 23.92** |

| Neglect x Group | −.13 | .12 | −.36 | .11 | 1.10 |

| Domain x Neglect | −.06 | .07 | −.20 | .08 | .73 |

| Domain X Group | .19 | .07 | .06 | .32 | 7.61** |

| EV X Neglect | −.44 | .32 | −1.06 | .18 | 1.90 |

| EV X Group | .45 | .30 | −.14 | 1.04 | 2.28 |

| Domain X EV X Group | −1.28 | .48 | −2.22 | −.34 | 7.14** |

| Domain X EV X Neglect | .13 | .50 | −.84 | 1.10 | .07 |

| Domain X Neglect X Group | −.01 | .07 | −.15 | .13 | .02 |

| EV X Neglect X Group | −.66 | .32 | −1.28 | −.04 | 4.32* |

| Neglect x Group x EV Level x Domain | .67 | .50 | −.31 | 1.64 | 1.81 |

p <. 05.

p < .01.

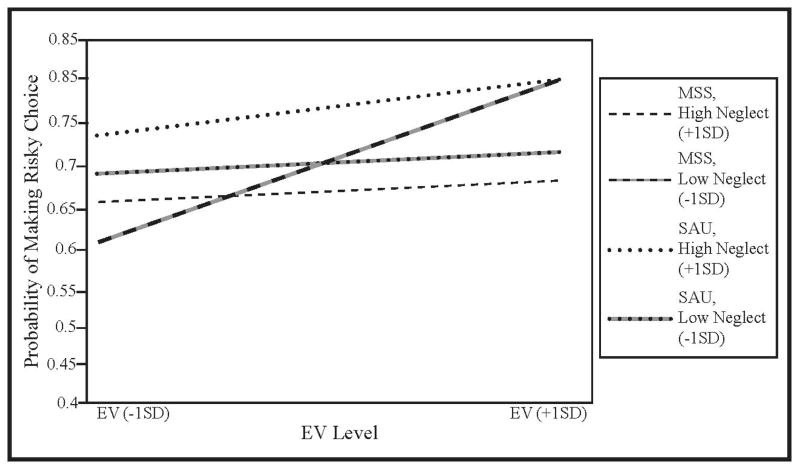

Foremost, the Group X EV level X Domain effect observed in the prior analyses remained significant, even with the inclusion of pubertal timing and neglect frequency. As illustrated in Figure 4, we observed a three-way Group X Neglect X EV Level interaction. SAU girls who had greater neglect histories showed increased risk-taking and lower overall EV Sensitivity. In contrast, MSS girls with less extensive histories of neglect demonstrated a pattern of decision-making similar to that of the CC group.

Figure 4.

Interaction Effect between Neglect and Intervention Group Status on Overall EV Sensitivity

Discussion

This study contributes to the extant literature on sensitive periods for neural plasticity in three main ways. First, we found specific aspects of adolescent decision-making abilities are affected by exposure to childhood maltreatment, suggesting sustained effects of maltreatment on neurocognitive functioning. Second, we identified the potential for plasticity via an intervention effect on risk-taking decisions to avoid losses: only those girls in traditional foster care (vs. those in the intervention condition—i.e., SAU vs. MSS) took more risks to avoid losses. Additionally, EV sensitivity, an index of advantageous decision-making, was especially impaired for risks involving potential losses in girls in the SAU, but not the MSS condition. Our results suggest that these differences may result from a lesser ability to adjust for changes in the outcome magnitude of the risky option, which signals increasing negative consequences. Third, our results suggest that the chronicity of reported neglect experienced during childhood moderated the effects of the intervention, suggesting the limits of plasticity. As hypothesized, girls in the SAU who reported more instances of neglect demonstrated the greatest amount of risk-taking and lowest degree of EV sensitivity. Conversely, the MSS girls reporting fewer instances of neglect most closely resembled the decision-making tendencies of non-maltreated, low SES peers.

Although past research has suggested neurocognitive deficits as a function of maltreatment status, less research has focused on the decision-making abilities of these youth. In this regard, this study reinforces and extends the results presented in Weller and Fisher (2013), which reported significant differences in risky decision-making between maltreated pre-adolescents (10–12 years) and non-maltreated cohorts using the same paradigm. Specifically, the prior study found that maltreated youth were more likely to take risks to avoid losses, but did not differ from the comparison group when taking risky gains. Similarly, we found that the girls in the SAU condition demonstrated increased risk-taking to avoid losses, and lower sensitivity to relative EV between choice options. However, we also demonstrated that some aspects of decision making are modifiable, and that the sensitive period for improving neurocognitive function extends to adolescence: girls randomly assigned to the MSS intervention demonstrated a pattern of decision-making that more closely resembled that of non-maltreated peers, especially with respect to EV sensitivity. Moreover, the differences in EV sensitivity between the MSS and SAU groups appeared to be more closely related to an insensitivity to changes in the outcome magnitude of the risky choice, rather than insensitivity to the probability that the event will occur. Considering that these effects were obtained controlling for a measure of crystalized intelligence, it suggests that the observed differences are not due simply to cognitive ability or basic understanding of probability rules.

These results are consistent with Yechiam and Hochman’s (2013) Attention-Allocation model that suggests that losses elicit greater attention than an equal gain. Applying this model to the effects of maltreatment, we propose that maltreated children and adolescents may have more difficulty effectively making decisions for potential losses due to both increased attentional biases towards potential losses and the inability to subsequently disengage from its emotional arousal to conduct a more compensatory evaluation of the choice options. Both animal research (i.e., rodents) investigating variations in maternal caregiving and studies focusing on child maltreatment have indicated also that the experience of early adversity is related to heightened attention to threat stimuli (Cameron et al., 2005; Pollak & Tolley-Schell, 2003). Additional research is needed to further test this model from a neurocognitive developmental perspective within the context of maltreatment.

In contrast to Weller and Fisher’s study that focused on preadolescent maltreated children, we found that maltreated girls to take more risks for decisions involving potential gains during adolescence. Neurodevelopmental research has suggested adolescence may be a time of increased emotional reactivity in terms of sensitivities to both rewards and punishments (Cauffman et al., 2010; Crone & Van der Molen, 2004; Ernst et al., 2005; Huizenga et al., 2007). Although comparing raw data across independent samples has obvious limitations, it is notable that maltreated girls, regardless of intervention condition, appeared to demonstrate a peak in risk-taking for potential gains, compared to the younger maltreated children studied in Weller and Fisher (2013). We speculate that the confluence of puberty and potential dysregulation of the HPA system, which is observed in many maltreated children (Cicchetti et al., 2010; Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2001; Gunnar et al., 2006), may contribute to an increase in reward-related risk taking during adolescence in our maltreated sample (Crone & Dahl, 2012; Mather & Lighthall, 2012).

This increased sensitivity may make adolescence a period of potential plasticity. Crone & Dahl (2012) posit that these neurodevelopmental changes may contribute to either a positive growth trajectory that emphasizes personal growth and adaptive exploration of the social environment, or a negative trajectory in which adolescents demonstrate excess motivation to engage in health-risking behaviors such as drug use and unprotected sex with multiple partners. This study suggests that early adolescence is an important inflection point for which trajectories ultimately may be realized. Given the appropriate interventions, we propose that the former can be more likely. Interventions targeting reward sensitivity around risks to attain gains may be more effective when implemented earlier in development. In the absence of an early intervention, the observation that overall risk propensity to achieve gains may be less malleable during adolescence implies that interventions initiated later in life might focus on leveraging these tendencies towards taking risks that promote personal growth and social competence, rather than solely aiming to reduce overall reward sensitivity.

Notably, we did show evidence of plasticity in some areas of decision making. Specifically, MSS girls demonstrated similar EV sensitivity to that of non-maltreated girls, whereas the SAU girls showed deficits in EV sensitivity. The ability make EV-sensitive judgments not only requires the ability to subjectively value each option by tying emotional salience to the choice options, but also to compare each option, accurately judge which option will maximize happiness (or minimize pain), and then act based on those predictions. In this sense, making EV-sensitive judgments involves resources related to executive function and cognitive control, facets of behavior that our MSS intervention targeted through intervention components such as goal-setting, planning, and emotion regulation coaching. In general, however, adolescents’ abilities to automatically recruit resources related to cognitive control may not be fully developed (see Crone & Dahl, 2012 for a recent review). A decreased tendency to automatically engage cognitive control strategies may lead even typically-developing adolescents to have difficulties disengaging from emotionally-arousing contexts. This disengagement may preclude the ability to conduct a more deliberative decision analysis, considering and appropriately integrating all relevant information. The positive effect of the MSS intervention on EV sensitivity suggests that the neurocognitive systems related to executive function and cognitive control may continue to be malleable into adolescence, reinforcing the proposition that neural plasticity may extend into early adolescence.

However, there are also limits to the plasticity in neurocognitive functions related to decision making. Our analyses examining the impact of severity of neglect on intervention effects suggested that girls who experienced a greater number of neglect incidents had poorer decision making than the community control girls, regardless of whether they received the MSS intervention or not. That is, MSS girls with high levels of neglect were not able to fully rebound and show decision making capacities similar to non-maltreated girls. However, the SAU girls with high levels of neglect showed the poorest decision making skills, suggesting that although the MSS intervention did fully improve the abilities to that observed for non-maltreated peers, it did yield some improvements even among those girls who experienced the highest levels of neglect. Although their EV sensitivity did not change, they nonetheless took fewer risks overall than the girls who experienced greater levels of neglect in the SAU group. Nonetheless, these results suggest that pervasive neglect experiences may affect neurocognitive development in ways that are difficult to remediate once a youth reaches adolescence, and interventions implemented earlier in development may be needed to increase effectiveness among youth exposed to high levels of neglect.

Future Directions and Limitations

This study provides preliminary evidence for plasticity during adolescence in a key ability domain (with relatively well-understood underlying neural correlates) that is associated with important health and life course outcomes. This point is especially noteworthy because our focus population is a high-adversity group known to demonstrate disparities in these areas. Although prior research has shown similar plasticity in younger high adversity children, this study begins to extend the scientific knowledge base into adolescence.

It is important to acknowledge that the present study focuses only on behavioral measures of risk taking in maltreated adolescent girls. Although we described the associations between behavioral measures and underlying neural systems in the limbic and prefrontal areas of the brain, an essential direction for future research in this area is to directly measure the activation of regions of interest in these areas via studies of tasks like the Cups Task in a neuroimaging environment (see Xue et al., 2009 for an fMRI study using a modified Cups Task). Such research has the potential to greatly expand our understanding of the role of these regions (and the connections between the regions) in decision making. It also carries with it the potential to determine the similarity between high-adversity adolescents and others in the neural circuitry subserving components of risky decision making. Similar circuitry would suggest that interventions for high-adversity adolescents might need to be increased in magnitude, but similar in approach to those found to be effective for the general population. In contrast, different circuitry would suggest that adaptations of existing strategies, or development of novel ones, might be required to maximally improve decision-making abilities in child welfare and other high-adversity populations.

A limitation of this study was that we did not assess the community comparison group on pubertal timing. Although pubertal timing has been associated with increased risk-taking more than chronological age (Steinberg, 2008), we did not find significant correlations between age of pubertal onset and decision-making. Without the assessment of menarche onset in the community group, we cannot fully assess the impact of pubertal timing in this study. Future research needs to be conducted to more explicitly answer this question.

Although part of the screening procedure and maltreatment records were examined, there also always exists a possibility of unreported maltreatment in all groups. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that some of the community comparison girls experienced maltreatment; however, the number of such instances likely would have been small, based on estimated base rates of abuse/neglect in the general population and the absence of a documented case of abuse/neglect. Nonetheless, in the event that some of the community comparison group had experienced unreported neglect, it likely would have attenuated our results. Further, unreported maltreatment would likely occur in all groups, and it would be difficult to explain how unreported maltreatment cases would impact the observed interaction effects.

We feel that this study offers unique insights into the development of decision-making preferences in the face of uncertain outcomes. However, this study only included a measure of risk-taking in which the participants explicitly knew the potential outcomes and the associated probabilities in which they occur. This information is frequently ambiguous in many of the decisions that are faced on a day-to-day basis, leading to subjective valuations of outcomes and probabilities. Additionally, real-world risks are often cumulative, such that the more one engages in a behavior, the more likely it is to result in harm (e.g., Weinstein, Slovic, Waters, & Gibson, 2004). Future research should involve the assessment of how maltreatment impacts risky decision-making in a more dynamic context.

Finally, an unanswered question is the degree to which laboratory-based assessments of risk-taking to avoid losses and to achieve gains may differentially predict health-risking behavior. This question spans beyond the focus of this article. Based on the current results and Yechiam and Hochman’s (2012) Attention Allocation model, we predict that risk-taking to avoid losses may be more likely to be associated with real-life risk behaviors. In support, Yechiam and Telpaz (2013) found evidence that risks involving potential losses predicted self-reported risk propensity across several domains (e.g., health/safety, financial, ethical, and social). Follow-up studies that address this question in a maltreatment context are needed.

Given the adverse effects that maltreatment bears upon its victims, as well as the societal and economic costs incurred, gaining a deeper understanding of how maltreatment impacts neurocognitive processes and when in development malleability is feasible become important goals. Our results highlight the negative impact of maltreatment on decision making skills during adolescence, as well as the potential for partial recovery via a family and skill-based intervention delivered during early adolescence. Conceptualizing how maltreatment impacts decision processes at different developmental periods and how the negative effects of maltreatment can be remediated can inform future researchers as to intervention approaches to help curtail decision-making deficits and the subsequent health-risking behaviors that are frequently observed in maltreated youth. This study provides an important step in this regard.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Weller and Leve (R21 DA027091). In addition, support was provided by P30 DA023920, P50 DA035763, and MH054257. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Patricia Chamberlain for her leadership in the original study, Danielle Guerrero for her project coordination of the current project, Michelle Baumann for editorial assistance, and the youth and families who participated in this project.

Footnotes

We remind the reader that “more favorable” can also indicate “less negative” when considering choices when all options involve a potential loss.

Contributor Information

Joshua A. Weller, Decision Research and Idaho State University

Leslie D. Leve, University of Oregon and Oregon Social Learning Center

Hyoun K. Kim, Oregon Social Learning Center

Jabeene Bhimji, Idaho State University.

Philip A. Fisher, University of Oregon

References

- Aarons GA, Brown SA, Hough RL, Garland AF, Wood PA. Prevalence of adolescent substance use disorders across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:419–426. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR, Kabbini NS. The dropout process in life course perspective: Early risk factors at home and school. Teachers College Record. 2001;103:760– 882. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. Reckless behavior in adolescence: A developmental perspective. Developmental Review. 1992;12:339–373. doi: 10.1016/0273-2297(92)90013-R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley-Levenson E, Galván A. Neural representation of expected value in the adolescent brain. 2014;111:1646–1651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319762111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Child abuse, child development, and social policy. Norwood, NJ: 1993. pp. 7–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ablex Bartra O, McGuire JT, Kable JW. The valuation system: A coordinate-based meta-analysis of BOLD fMRI experiments examining neural correlates of subjective value. NeuroImage. 2013;76:412–427. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD. Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology. 2001;5:323–370. [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR, Lee GP. Different contributions of the human amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex to decision-making. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:5473–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05473.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers SR, De Bellis MD. Neuropsychological function in children with maltreatment-related posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:483–486. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryck RL, Fisher PA. Training the brain: Practical applications of neural plasticity from the intersection of cognitive neuroscience, developmental psychology, and prevention science. American Psychologist. 2012;67:87–100. doi: 10.1037/a0024657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantin S, Boivin M. Change and stability in children’s social network and self-perceptions during transition from elementary to junior high school. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2004;28:561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Carrion VG, Weems CF, Eliez S, Patwardhan A, Brown W, Ray RD, Reiss AL. Attenuation of frontal asymmetry in pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;50:943–951. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrion VG, Weems CF, Richert K, Hoffman BC, Reiss AL. Decreased prefrontal cortical volume associated with increased bedtime cortisol in traumatized youth. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:491–493. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Jones RM, Somerville LH. Braking and accelerating of the adolescent brain. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:21–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron NM, Champagne FA, Parent C, Fish EW, Ozaki-Kuroda K, Meaney MJ. The programming of individual differences in defensive responses and reproductive strategies in the rat through variations in maternal care. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005;29:843–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauffman E, Feldman SS, Waterman J, Steiner H. Posttraumatic stress disorder among female juvenile offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1209–1216. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199811000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauffman E, Shulman EP, Steinberg L, Claus E, Banich MT, Graham S, Woolard J. Age differences in affective decision making as indexed by performance on the Iowa Gambling Task. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:193–207. doi: 10.1037/a0016128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Leve LD, Smith DK. Preventing behavior problems and health-risking behaviors in girls in foster care. International Journal of Behavioral and Consultation Therapy. 2006;2:518–530. doi: 10.1037/h0101004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price JM, Reid JB, Landsverk J, Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M. Who disrupts from placement in foster and kinship care? Child Abuse and Neglect. 2006;30:409–424. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Reid JB. Parent observation and report of child symptoms. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Chung H, Elias M, Schneider K. Patterns of individual adjustment changes during middle school transition. Journal of School Psychology. 1998;36:83–101. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(97)00051-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. Annual research review: Resilient functioning in maltreated children - past, present, and future perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2013;54:402–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. The impact of child maltreatment and psychopathology on neuroendocrine functioning. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:783–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Howe ML, Toth SL. The effects of maltreatment on neuroendocrine regulation and memory performance. Child Development. 2010;81:1504–1519. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb-Clark DA, Ryan C, Sartbayeva A. Taking Chances: The effect that growing up on welfare has on the risky behavior of young people. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics. 2012;114:729–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9442.2012.01704.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD, Chen K, Bandy D, Reiman EM. Thermosensory activation of insular cortex. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:184–90. doi: 10.1038/72131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone E, van der Molen MW. Developmental changes in real life decision making: Performance on a gambling task previously shown to depend on the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2004;25:251–279. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2503_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone EA, Dahl RE. Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2012;13:636–650. doi: 10.1038/nrn3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD, Keshavan MS, Shifflett H, Iyengar S, Beers SR, Hall J, Moritz G. Brain structures in pediatric maltreatment-related posttraumatic stress disorder: A sociodemographically matched study. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:1066–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Peloso E, Lewis E, Laurenceau JP, Levine S. Effects of an attachment-based intervention on the cortisol production of infants and toddlers in foster care. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:845–859. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Dickstein DP, Munson S, Eshel N, Pradella A, Jazbec S, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Reward-related processes in pediatric bipolar disorder: a pilot study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82(Suppl 1):S89–S101. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Nelson EE, Jazbec S, McClure EB, Monk CS, Leibenluft E, Pine DS. Amygdala and nucleus accumbens in responses to receipt and omission of gains in adults and adolescents. Neuroimage. 2005;25:1279–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Brown DS, Florence CS, Mercy JA. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2012;36:156–65. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenzel LM. Prospective study of changes in global self-worth and strain during the transition to middle school. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2000;20:93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Bruce J, Abdullev Y, Mannering AM, Pears KC. The effects of early adversity on the development of inhibitory control: Implications for the design of preventive interventions and the potential recovery of function. In: Bardo MT, Fishbein DH, Milich R, editors. Inhibitory Control and Abuse Prevention: From Research to Translation. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 229–247. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Gunnar M, Dozier M, Bruce J, Pears KC. Effects of a therapeutic intervention for foster children on behavior problems, caregiver attachment, and stress regulatory neural systems. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1094:215–225. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M. Intervention effects on foster parent stress: associations with child cortisol levels. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:1003–1021. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M, Gunnar MR, Burraston BO. Effects of a therapeutic intervention for foster preschoolers on diurnal cortisol activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:892–905. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, Dahl RE. Pubertal development and behavior: hormonal activation of social and motivational tendencies. Brain and Cognition. 2010;72:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Almas AN, Degnan KA, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH. The effects of severe psychosocial deprivation and foster care intervention on cognitive development at 8 years of age: Findings from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;59:919–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan A, Hare T, Voss H, Glover G, Casey BJ. Earlier development of the accumbens relative to orbitofrontal cortex might underlie risk taking behavior in adolescents. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:6885–6892. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1062-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N, Masten AS, Tellegen A. The study of stress and competence in children: A building block for developmental psychopathology. Child Development. 1984;55:97–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]