Abstract

IMPORTANCE

In 2011, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) approved intensive behavioral weight loss counseling (i.e., approximately 14, 10–15 minute, face-to-face sessions in 6 months) for obese beneficiaries in primary care settings, when delivered by physicians and other CMS-defined primary care practitioners (PCPs).

OBJECTIVE

To conduct a systematic review of behavioral counseling for overweight/obese patients recruited from primary care, as delivered by PCPs working alone or with trained interventionists (e.g., medical assistants, registered dietitians), or by trained interventionists working independently.

EVIDENCE REVIEW

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, and EMBASE for randomized controlled trials (January 1980–June 2014) which: recruited overweight/obese patients from primary care; provided behavioral counseling (i.e., diet, exercise, and behavior therapy) for ≥3 months, with ≥6 months post-randomization follow-up; included ≥15 participants/treatment group and objectively measured weights; and had a comparator, an intention-to-treat analysis, and attrition <30% at 1 year or <40% at longer follow-up.

FINDINGS

Review of 3,304 abstracts yielded 12 trials (with 3,893 total participants) that met inclusion/exclusion criteria and pre-specified quality ratings. No studies were found in which PCPs delivered counseling following CMS guidelines (14 sessions in 6 months). Mean 6-month weight changes (relative to baseline) in the intervention group ranged from −0.3 to −6.6 kg, with corresponding values of +0.9 to −2.0 kg in control group. Weight loss in both groups generally declined with longer follow-up (12–24 months). Interventions that prescribed both reduced energy intake (e.g., ≥500 kcal/day deficit) and increased physical activity (e.g., ≥150 minutes/week of walking), with traditional behavior therapy, generally produced larger weight loss than interventions without all three specific components. In the former trials, more treatment sessions, delivered in person or by phone by trained interventionists, were associated with greater mean weight loss and likelihood of losing ≥5% of baseline weight.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Intensive behavioral counseling can induce clinically meaningful weight loss, but there is little research on PCPs providing such care. The present findings suggest that a range of trained interventionists, who deliver counseling in person or by telephone, could be considered in treating overweight/obesity in patients encountered in primary care.

Obesity has been the subject of increasing professional attention in the past decade, including the American Medical Association’s declaration that it is a disease.1 In 2003 (and again in 2011) the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that primary care practitioners screen all adults for obesity and offer intensive behavioral counseling to affected individuals, either by providing such treatment themselves or by referral.2,3 In 2011, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services approved the provision of intensive behavioral counseling (~14 face-to-face visits in 6 months) to obese beneficiaries in primary care practice, when delivered by physicians and other select practitioners (Box 1).4,5

Box 1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Requirements for Intensive Behavioral Therapy for Obesity.

Treatment Components

|

|

Frequency of Contact A maximum of 22 sessions in a 12-month period, as follows:

|

Eligible Providers

|

Eligible Settings

|

Weight Loss Assessment

|

Note: USPSTF = U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

Services also may be provided by auxiliary personnel incident to a physician or other primary care practitioner’s professional service, when directly supervised by the physician or other practitioner (see reference 5).

The frequency of behavioral counseling prescribed by CMS is generally consistent with conclusions of a review commissioned by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force6 and with recommendations of the recently published Obesity Guidelines.7 The latter guidelines, based on findings of a systematic review, advise primary care practitioners to prescribe overweight/obese individuals a high intensity (i.e., ≥14 sessions in 6 months) comprehensive lifestyle intervention, delivered by a trained interventionist.6 Interventionists in the studies reviewed included registered dietitians, psychologists, exercise specialists, health counselors, medical assistants, and laypersons, all of whom delivered counseling following structured protocols.6 Comprehensive behavioral interventions, as defined by the Obesity Guidelines, include the prescription of: 1) a reduced calorie diet (typically to induce an energy deficit ≥500 kcal/d); 2) ≥150 min/week of aerobic physical activity (typically walking); and 3) the use of behavioral strategies to facilitate adherence to diet and activity recommendations.6,8

The present systematic review examines the evidence to support the behavioral treatment of obesity in patients encountered in primary care settings. The review summarizes the results of randomized controlled trials conducted with patients recruited from primary care, in which CMS-defined primary care practitioners, working alone or with trained interventionists, delivered behavioral weight loss counseling. The review also examines randomized trials of patients recruited from primary care in which trained interventionists (who were not primary care practitioners) delivered behavioral counseling, including by telephone and Internet.8 These latter interventionists are not currently recognized by CMS as independent providers of behavioral counseling, although they may potentially provide services incident to eligible practitioners (see Box 1).5 This review does not include trials such as the Diabetes Prevention Program9 or Look AHEAD study10 in which behavioral counseling was provided to highly-selected volunteers, recruited outside of primary care.

METHODS

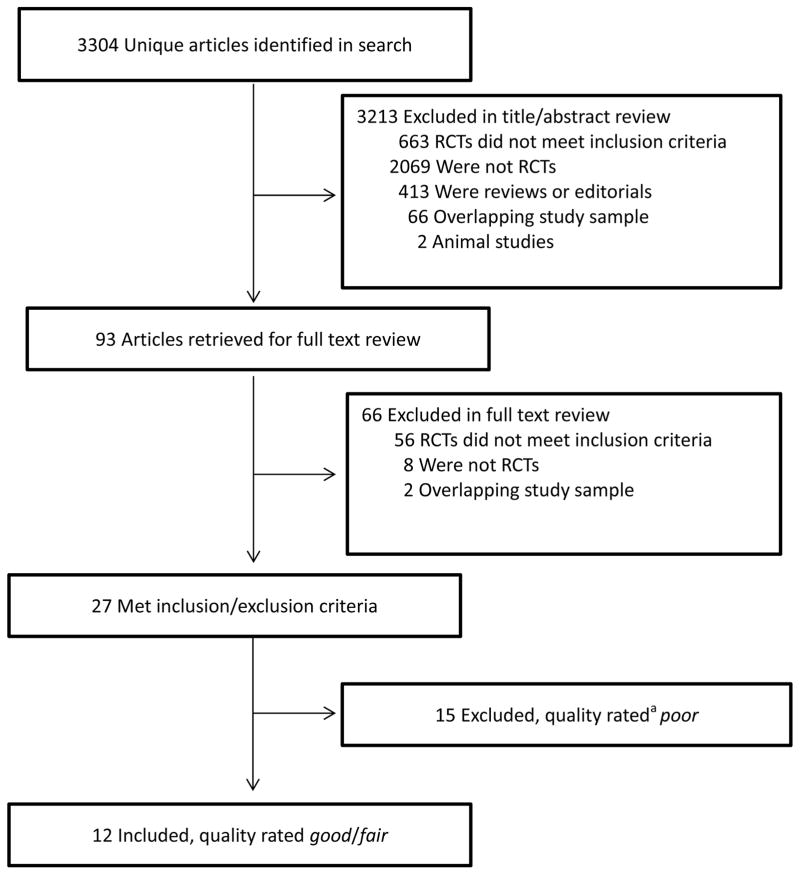

This review used methods similar to those employed in developing the recent Obesity Guidelines6 (which updated those from 199811). The present authors used the PICOTS12 (i.e., population, interventions, comparators, outcomes, timing, setting) approach to establish inclusion/exclusion criteria and searched PubMed, CINAHL, and EMBASE (January 1, 1980–June 30, 2014) using terms including “obesity, primary care, weight loss, counseling, diet, exercise, behavior modification, and lifestyle counseling.” Studies included were randomized trials that were published in the English language and had the following characteristics: 1) overweight or obese adults (i.e., body mass index [BMI] ≥25 kg/m2) recruited from primary care settings; 2) participants received behavioral weight loss counseling (also referred to as lifestyle intervention) consisting of diet, physical activity, and behavioral strategies (all three components);6 3) behavioral counseling ≥3 months, with ≥6 months post-randomization follow-up; 4) intervention delivered by CMS-defined primary care practitioners, working alone or with trained interventionists, or by trained interventionists alone who provided behavioral counseling in person or remotely (e.g., telephone); 5) a comparator intervention was included; 6) outcomes included objectively measured change in weight (reported in kg, BMI units, or % change); and 7) randomized sample size ≥15 per treatment group. (This review did not include trials of weight gain prevention or pharmacologic agents.) The search resulted in 3,304 articles (Figure 1). It was supplemented by examination of prior reviews7,13–15 and a search of Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials.

Figure 1.

Organization and flow of the literature search. a Quality ratings were made following the procedures used by the American Heart Association American College of Cardiology Obesity Society in developing the Guidelines for the Management of Overweight and Obesity.6 Two of the original 14 items (#3 and #4) for quality rating were not used because they were not applicable to behavioral treatment studies. Studies were rated on a 12-point scale comprised of the remaining items. Studies with a score <6 were rated “poor,” those with scores of 6–8 were rated “fair,” and those with scores ≥9 as “good.” A study also was rated “poor” if it had a fatal methodological flaw, as described in the Methods section. RCT = randomized controlled trial.

Titles and abstracts of all papers were reviewed independently by two authors to exclude non-relevant articles. The full text of each remaining article was similarly reviewed to determine if it met inclusion/exclusion criteria. As shown in Figure 1, 27 studies16–42 (3 of which published additional follow-up data43–45) met all criteria and were subjected to quality rating (i.e., poor, fair, or good) by two authors who used criteria similar to those employed by the Obesity Guidelines.6 Fifteen studies were excluded from further consideration because they were rated poor or had one or more fatal flaws: 1) high attrition (average ≥30% at 6 or 12 months or ≥40% thereafter);29,30,33,35,37–39,41,42 2) differential attrition between treatment groups >15% at any time;31,34,36,40 or 3) failure to report results of an intention-to-treat analysis (unless attrition was <10% at the time for which data were reported in a completers-only analysis).28,29,32,37–39,42

The 12 remaining studies, all rated good, were divided into two categories following preliminary examination. The first category was whether the weight loss program prescribed all three components of a comprehensive lifestyle intervention as operationalized by the Obesity Guidelines.6 Seven trials, for example, encouraged participants to change components of their diet but did not specifically prescribe a reduced-calorie diet (i.e., deficit ≥500 kcal/d).21–27 Six21,23–27 of these seven trials similarly did not provide primarily behavioral counseling, as identified by the Obesity Guidelines, but instead included instruction guided principally by motivational interviewing46 or stages of change theory (i.e., the transtheoretical model).47 Motivational interviewing typically is less prescriptive than traditional behavioral weight loss counseling and encourages exploration of ambivalence about change.46 This approach may conflict with more directive behavioral counseling, although some investigators have successfully combined the two interventions.48 (Two studies in this review used elements of motivational interviewing within a primarily behavioral approach.19,22) The stages of change model seeks to match interventions to participants’ readiness to change.47 This approach, like motivational interviewing, often avoids prescribing specific energy intake and expenditure goals on a set schedule. As shown in Table 1, the two different groups of studies are referred to as traditional behavioral counseling (N=5) and alternative behavioral counseling (N=7), respectively.

Table 1.

Participants’ Mean Baseline Characteristics and Mean Changes in Weight (Relative to Baseline Weight) at Month 6 and Follow-Up.

| Study | Sample Characteristics | Interventions, Number (N) Randomized | Number of Treatment Sessions | Mo. of Post-Baseline Follow-Up | Weight Change at Mo. 6, kg (95% Confidence Interval) | Weight Change at Follow-up, kg (95% Confidence Interval) | ≥5% Weight Loss at Follow-Up, no. (%) | Attrition at follow-up, no. (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRADITIONAL BEHAVIORAL COUNSELING | ||||||||

| Primary Care Practitioners/Trained Interventionists | ||||||||

| Kumanyika et al,16 2012 | Age, 47.2 y; BMI, 37.2; 84.3% Women; 18.0% White, 65.0% Black | 1. Basic, N = 137 | 3 | 12 | Not Reported (NR) | −0.6 (−1.4, 0.2)a | 10 (10.2)a | 39 (28.5) |

| 2. Basic Plus, N = 124 | 15 | NR | −1.6 (−2.8, −0.4)a | 20 (22.5)b | 35 (28.2) | |||

| Tsai et al,17 2010 | Age, 49.4 y; BMI, 36.5; 88.0% Women; 20.0% White, 80.0% Black | 1. Control, N = 26 | 4 | 12 | −0.9 (−2.1, 0.3)a | −1.1 (−2.7, 0.5)a | 3 (12.0)a | 1 (3.8) |

| 2. Brief Counseling, N = 24 | 12 | −4.4 (−5.6, −3.2)b | −2.3 (−4.1, −0.5)a | 4 (18.0)a | 2 (8.3) | |||

| Wadden et al,18 2011 | Age, 51.9 yr;** BMI, 38.7;** 79.7% Women;** 59.8% White, ** 37.5% Black;** 2 or more components of metabolic syndrome | 1. Usual Care, N = 130 | 8 | 24 | −2.0 (−3.0, −1.0)a | −1.7 (−3.1, − 0.3)a | 28 (21.5)a | 20 (15.4) |

| 2. Brief Lifestyle Counseling, N = 131 | 33 | −3.5 (−4.5, −2.5)b | −2.9 (−4.3, −1.5)a | 34 (26.0)a | 19 (14.5) | |||

| Trained Interventionists | ||||||||

| Appel et al,19 2011 | Age, 54.0 y; BMI, 36.6; 63.6% Women; 56.1% White, 41.0% Black; ≥ 1 CVD risk factors | 1. Control, N= 138 | 2 | 24 | −1.4 (−2.2, −0.6)a | −0.8 (−2.0, 0.4)a | 24 (18.8) a | 10 (7.2) |

| 2. Remote support, N = 139 | 33 | −6.1 (−7.1, −5.1)b | −4.6 (−6.0, −3.2)b | 50 (38.2) b | 8 (5.8) | |||

| 3. In person support N= 138 | 57 | −5.8 (−7.0, −4.6)b | −5.1 (−6.7, −3.5)b | 55 (41.4) b | 5 (3.6) | |||

| Ma et al,20 2013 Xiao et al,43 2013 | Age, 52.9 y; BMI, 32.0; 46.5% Women; 78.0% White, 17.0% Asian/Pacific Islander; pre−diabetes or metabolic syndrome | 1. Usual Care, N = 81 | 0 | 24 | −0.7 (−2.5, 1.1)a | −2.4 (−4.2, −0.6)a | 17 (25.3)a | 21 (25.9) |

| 2. Coach-led, N = 79 | 12 | −6.6 (−8.2, −5.0)b | −5.4 (−7.2, −3.6)b | 39 (59.1)b | 20 (25.3) | |||

| 3. Self-directed N = 81 | 1 | −4.3 (−5.9, −2.7)b | −4.5 (−6.3, −2.7)b | 26 (43.6)b | 29 (35.8) | |||

| ALTERNATIVE BEHAVIORAL COUNSELING | ||||||||

| Primary Care Practitioners/Trained Interventionists | ||||||||

| Christian et al,21 2011 | Age, 49.6 y; BMI, 34.3;** 68.4% Women; 50.6% White; two or more features of metabolic syndrome | 1. Control, N = 139 | 1 | 12 | NR | 0.15 (−0.65, 0.95)a | 11 (8.5)a | 9 (6.5) |

| 2. Intervention, N = 140 | 2 | NR | −1.5 (−2.5, −0.5)b | 35 (26.3)b | 7 (5.0) | |||

| Trained Interventionists | ||||||||

| Bennett et al,22 2012 | Age, 49.6 y; BMI, 37.0; 68.5% Women; 3.6% White, 71.2% Black; antihypertensive medication use | 1. Usual care, N = 185 | 0 | 24 | −0.1 (−0.8, 0.6)a | −0.5 (−1.3, 0.3)a | 36 (19.5)a | 19 (10.3) |

| 2. Intervention, N = 180 | 30 | −1.3 (−2.1, −0.5)b | −1.5 (−2.3, −0.7)b | 36 (20.0)a | 31 (17.2) | |||

| de Vos et al,23 2014§ | Age, 55.7 y; BMI, 32.4; 100% Women; 92.6% White; 0.6% Black; 1.1 % South American; 1.1% Asian; 4.5% Other | 1. Control, N = 204 | 0 | 12 | 0.9 (0.3, 1.5)a | 0.6 (−0.2, 1.4)a | 20 (11.0)a | 23(11.3) |

| 2. Intervention, N = 203 | 26 | −0.9 (−1.5, 0.3)b | −0.6 (−1.4, 0.2)b | 35 (18.7)b | 16 (7.9) | |||

| Greaves et al,24 2008 | Age, 53.9 y; Weight, 93.0 kg; 63.8% Women; Race/Ethnicity Not reported; without diabetes or heart disease | 1. Control, N = 69 | 0 | 6 | −1.8a*** | NR | 5 (7.2)a | 12 (17.4) |

| 2. Intervention, N = 72 | 11 | −0.3b*** | NR | 17 (23.6)b | 14 (19.4) | |||

| Hardcastle et al,25 2008; Hardcastle et al, 201343 | Age, 50.2 y; BMI, 33.7; Gender Not reported; Race/Ethnicity Not reported; ≥ 1 CVD risk factor | 1. Minimal intervention, N = 131 | 0 | 18 | 0.1 (−0.5, 0.7)a | 1.4a*** | NR | 38 (29.0) |

| 2. Motivational Interviewing, N = 203 | 5 | −0.7 (−1.3, −0.1)b | 0.5a*** | NR | 78 (38.4) | |||

| Logue et al,26 2005 | Ages 40–69 y; BMI ≥ 27 or WHR > 0.95 (men) or > 0.8 (women); 68.5 % Women; Race/Ethnicity not reported | 1. Augmented Usual Care, N = 336 | 4 | 24 | NR | −0.2 (−1.0, 0.6)a | NR | 70 (20.8) |

| 2. Trans-theoretical Model, N = 329 | 28 | NR | −0.4 (−1.2, 0.4)a | NR | 58 (17.6) | |||

| Ross et al,27 2012 | Age, 51.8 y;e BMI, 27–39; 70.2% Women; Race/Ethnicity Not reported; sedentary; abdominally obese | 1. Usual Care, N = 241 | 0 | 24 | −0.7 (−1.3, −0.1)a | −0.6 (−1.4, 0.2)a | NR | 35 (14.5) |

| 2. Behavioral Intervention, N = 249 | 33 | −2.4 (−3.0, −1.8)b | −1.2 (−2.0, −0.4)a | NR | 59 (23.7) | |||

Note: BMI = body mass index, CVD = cardiovascular disease, PI = Pacific Islander, TM-CD = transtheoretical model-chronic disease, NR = not reported.

Values shown for age and BMI are means.

For each study, under “weight change” (at month 6 and at follow-up) values within columns labeled with different letters (a, b) are significantly different from each other at P<.05. For example, in the Tsai et al. study, the mean 6-month weight loss of −0.9 (−2.1, 0.3)a for the control group differs significantly from the −4.4 (−5.6, −3.2)b loss for the brief counseling. Values with the same letter (a) are not significantly different, as for example, with the 12-month control and brief counseling weight losses in the Tsai et al. study.

Within each study, all treatment groups had the same number of months of post-baseline follow-up.

Attrition is defined as the percentage of participants who did not contribute an in-person weight at the end of the study;

Calculated mean;

Variance not reported.

Weights were measured at 30 months but are not included in this review since they were only provided in a figure in the paper. In addition, this paper reported on percentage of participants who lost ≥5kg or ≥5% of baseline body weight.

Within each group of studies, the trials were further divided (i.e., second category) according to whether behavioral counseling was delivered by CMS-defined primary care practitioners (working alone or with a trained interventionist) or by a trained interventionist alone, without personal collaboration with participants’ primary care practitioners. Studies in the former category were more likely to meet current CMS coverage requirements.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

The 12 identified studies included a total of 3,893 participants, with a range of 50–665 persons per study.16–27 Across trials, mean baseline BMIs ranged from 32.0 to 38.5 kg/m2 and ages from 49.4 to 55.7 years. The percentage of female participants ranged from 46.5% to 100% (see Table 1).

Traditional Behavioral Counseling: Primary Care Practitioners/Trained Interventionists

Three studies assessed behavioral counseling delivered in person by CMS-defined primary care practitioners (PCPs), working alone or with trained interventionists.16–18 Kumanyika et al16 compared participants randomly assigned to “Basic” lifestyle intervention (i.e., PCP visits every four months) or “Basic Plus,” which included the PCP meetings plus monthly brief (10–15 minute) individual sessions with a trained interventionist (typically a medical assistant) who delivered counseling following a modified version of the Diabetes Prevention Program9 (see Table 2 for details). At month 12, mean weight losses in Basic and Basic Plus were 0.6 and 1.6 kg, respectively (P=.15) (Table 1). Significantly more participants in the latter group lost ≥5% of baseline weight (10.2% vs 22.5%, P=.022).

Table 2.

Description of Intervention Components and Providers.

| Study | Intervention Group | Intervention Frequency and Provider | Method of Intervention Delivery | Role of Primary Care Provider (PCP) | Components of Diet, Physical Activity (PA), and Behavior Therapy (BT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRADITIONAL BEHAVIORAL COUNSELING | |||||

| Primary Care Practitioners/Trained Interventionists | |||||

| Kumanyika et al,16 2012 | 1. Basic | Counseling every 4 mo with the PCP based on Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) materials. PCPs completed 3 hr training. | On-site visits with PCP. | Provided brief counseling during visits every 4 mo. | Diet: 1200–1499 kcal/day with 30 g fat (if weight <100 kg) or 1500–1800 kcal/day with 40 g fat (≥100 kg); provided calorie counter. PA: 150 min of moderate PA/week, typically walking. BT: Prescribed DPP behavior change program, including self-monitoring of diet and PA; goal setting. |

| 2. Basic Plus | Visits every 4 mo with PCP; 10–15 min monthly individual sessions with a lifestyle coach, usually a medical assistant (MA). MAs completed 3 hr training. | On-site visits with PCP and lifestyle coach. | Same as for Basic. | Diet: Same as for Basic. PA: Same as for Basic. BT: Same as for Basic. |

|

| Tsai et al,17 2010 | 1. Control | Quarterly usual care meetings with PCP (weight management, ~2–3 min). PCPs trained in use of weight loss handouts. | On-site visits with physician. | Regular medical care with weight management as part of visit. PCPs reviewed weight loss handouts at quarterly visits. | Diet: Standard advice to eat healthy diet; provided calorie counter and meal plans. PA: Standard advice to exercise more; provided pedometer. BT: 1–2 page handouts from NIH/Weight-Control Information Network, including healthy behaviors. |

| 2. Brief Counseling | Quarterly usual care meetings with PCP (weight management, ~2–3 min); 8 brief (10–15 min) individual meetings with MAs at weeks 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24. MAs completed 3 hr training. | On-site visits with PCP or MA (with occasional phone counseling by MAs for missed visits). | Same as for Control group. | Received same materials as control group. Diet: 1200–1499 kcal/day (<250 lb) or 1500–1800 kcal/day (≥250 lb). PA: gradual increase to 175 min/week, typically walking. BT: Prescribed DPP behavior change program, including self-monitoring of diet and PA; handouts at each visit; weighed at each visit and reviewed food records with MA. |

|

| Wadden et al,18 2011 | 1. Usual Care | Quarterly usual care visits with PCP (weight management, ~5–7 min). PCP completed 6–8 hr training at baseline. | On-site, routine clinical visits with physician. | Discussed handouts; reviewed participants’ weight change; | Diet: 1200–1500 kcal/day (<113.4 kg) or 1500–1800 kcal/day (≥113.4 kg); received calorie counting book and pedometer. PA: Gradual increase to 180 min/week, typically walking. BT: Handouts from NHLBI’s “Aim for a Healthy Weight”. |

| 2. Brief Lifestyle Counseling | Quarterly usual care visits with PCP (weight management, ~5–7 min); monthly individual meetings (~10–15 min) with a lifestyle coach, usually a MA (with two visits in month 1). MAs completed 8-hr training at baseline and received monthly group supervision thereafter. | On-site, individual visits with PCP and MA. In year 2 counseling visits could be completed every other month by phone. | Same as for Usual Care. | Diet: Same prescription and materials as Usual Care. PA: Same PA prescription as Usual Care. BT: Prescribed DPP behavior change program, including self-monitoring of diet and PA; handouts at each visit; weighed at each visit and reviewed food records with MA. |

|

| Trained Interventionists | |||||

| Appel et al,19 2011 | 1. Control | One session with weight loss coach (a university employee) at randomization and, if desired, one after final data collection visit. | On-site, individual visit with staff member. | None | Received brochures and a list of recommended websites promoting weight loss. |

| 2. Remote Support Only | Individual, 20-min phone calls weekly for 12 weeks, then monthly. Coaches were trained employees from a disease management company. |

Telephone and web-based counseling. | Reviewed progress reports at routine office visits; encouraged participation and engagement in intervention. | Diet: DASH diet with 1200–2200 kcal/day. PA: Increase to 180 min/week of moderate intensity. BT: Self-monitoring of diet and PA; problem solving and social support; study website; motivational interviewing elements. |

|

| 3. In-Person Support | Combination of 9 group (90 min) and 3 individual (20 min) contacts for 12 weeks, then 2–3 such contacts per month. Coaches were trained university employees. |

Off-site counseling (at academic medical center); also telephone and web-based support | Same as for Remote support only. | Diet: Same as for Remote Support Only. PA: Same as for Remote Support Only. BT: Same as for Remote Support Only |

|

| Ma et al,20 2013; Xiao et al,43 2013 | 1. Usual Care | None | None | None | No materials provided. |

| 2. Coach-Led, Intervention | 12 in-person, group sessions (90–120 min) in mo 1–3; contact every 2–4 weeks by e-mail or telephone in mo 4–15. Registered dietitian (certified to deliver the DPP) and a fitness instructor jointly taught all classes. |

On-site, group classes during mo 1–3; e-mail or telephone contacts thereafter. | None | Diet: Low-fat diet to induce 500–1000 kcal/day energy deficit. PA: ≥150 min of moderate PA/week; 30–45 min of supervised PA at weekly class during mo 1–3. BT: DPP Group Lifestyle Balance program; AHA Heart 360 website for physical activity and goal setting; weight scale and pedometer for self-monitoring and goal setting. |

|

| 3. Self-directed DVD intervention | Orientation class in-person plus instruction to watch 12 DPP lifestyle sessions (90–120 min) via DVD at home during mo 1–3; lifestyle coach sent standardized bi-weekly reminder messages during mo 1–15. | On-site orientation session; intervention delivered via home-based DVD; e-mail messages (standardized) during maintenance. | None | Diet, PA, and BT: DPP on DVD; use of AHA Heart 360 website for physical activity and goal setting; given weight scale and pedometer for self-monitoring and goal setting. |

|

| ALTERNATIVE BEHAVIORAL COUNSELING | |||||

| Primary Care Practitioners/Trained Interventionists | |||||

| Christian et al,21 2011 | 1. Control | Clinic staff provided education packet prior to baseline visit. | Written materials. | None | Packet of health education materials at baseline visit addressing diabetes, diet, and exercise. |

| 2. Intervention | Twice-yearly counseling with PCP during routine visits. Clinic staff administered one computer-based assessment session prior to baseline visit and one session at 6 mo. PCP completed 3-hr training in motivational interviewing. | On-site; computer assessment, physician feedback. | Received computer-generated report with summary of each patient’s assessment; patients were provided recommendations for behavior change following stages of change and motivational interviewing. | Diet, PA, and BT: Individualized, computer-generated report addressing participant-identified barriers to making lifestyle changes; motivational interviewing to reduce calorie intake and increase PA; increase self-efficacy to make lifestyle changes; 30-page guide providing general supplemental information on diabetes prevention and achieving dietary and physical activity goals. |

|

| Trained Interventionists | |||||

| Bennett et al,22 2012 | 1. Control | Initial visit with program staff. | Self-help booklet. | None | NHLBI’s “Aim for a Healthy Weight” booklet provided. |

| 2. Intervention | 12 monthly and 6 bimonthly calls (15–20 min); 12 optional, monthly group sessions; 1 brief standardized message from PCP. Trained community health educators. |

Telephone, study website, interactive voice response system | Delivered at least 1 message about importance of intervention; electronic signature included on behavior change prescription. | Diet: Tailored behavior change goals to create an energy deficit. PA: Walk 10,000 steps/day, 20 min/day brisk walking, strength training 2 days/week. BT: Goal prescriptions; self-monitoring; tailored skills training; problem solving; motivational interviewing elements. |

|

| de Vos et al,23 2014 | 1. Control | None | None | None | No materials provided. |

| 2. Intervention | Referral to registered dietitian for up to 4 hr of counseling in year 1; up to 20, 1-hr group exercise classes with physical therapist in first 6 mo. Dietitians trained in motivational interviewing. | Off-site individualized meetings and physical activity courses. | None | Diet: Tailored advice for a low-fat or low-calorie diet. PA: Increased physical activity; physical activity classes offered. BT: Motivational interviewing; goal setting. |

|

| Greaves et al,24 2008 | 1. Control | Written guidelines at study outset; 2 individual sessions with counselors at study end; clinic staff. | Received standardized information packet promoting diet and physical activity. | None | Diet, PA, and BT: British Heart Foundation health-promotion materials; National Health Service Smoking Cessation Service ‘Green Book;’ locally produced information on ‘walk and talk’ activities. |

| 2. Intervention | Up to 11 individual visits (~30 min) in-person or by telephone for 6 mo. Health promotion counselors, including one nurse and three postgraduate students, completed 2-day course in motivational interviewing. |

On-site, individual consultations and telephone contacts. | None | Diet: Reduce calories, fat, and portion size; increase fiber. PA: Increase overall physical activity within existing lifestyle. BT: Motivational interviewing; relapse prevention; self-monitoring. |

|

| Hardcastle et al,2008;25 201344 | 1. Minimal Intervention | Clinic staff provided written materials. | Written materials | None | Diet: Written materials encouraging increased fruit and vegetable intake and reduced fat. PA: Written materials encouraging 30 min/day of PA. BT: None |

| 2. Motivational Interviewing | One consultation with PA specialist or registered dietitian with opportunity to meet 4 more times (20–30 min) following 6 mo. PA specialist and registered dietitian participated in two 4 hr training sessions focused on MI. | On-site, individual consultation. | None | Diet: Motivational interviewing to improve diet. PA: Motivational interviewing to increase physical activity. BT: Motivational interviewing integrated with a stage-matched approach; agenda setting; exploration of the pros and cons, importance and confidence rulers, strengthening commitment to change and negotiating a change plan. |

|

| Logue et al,262005 | 1. Augmented Usual Care | Semi-annual meeting with registered dietitian for 10-min sessions based on the USDA Food Guide Pyramid or a Soul Food Guide Pyramid. | On-site, individual meeting. | None | Diet: Recommendations based on dietary recalls and standard dietetic practice (Dietary Guidelines for America). PA: Recommendations based on exercise recalls. BT: Counseling based on either USDA Food Guide Pyramid (Dietary Guidelines for Americans) or a Soul Food Guide Pyramid; Behavioral self-monitoring. |

| 2. Trans-theoretical Model | Same dietitian visits as Usual Care; monthly 15-min telephone calls with a weight-loss advisor, conducted “stage-of-change” (SOC) assessments for five target behaviors every month; mailed SOC and target behavior-matched workbooks. Weight loss advisor trained in SOC, supervised by psychologist. |

On-site, individual meeting, mailings, telephone support. | Discussion with patient during routine visits, facilitated by SOC pocket card; received periodic reports summarizing patient progress with respect to target behaviors. | Diet: Counseling based on standard dietetic practice (Dietary Guidelines for America). PA: Counseling to increase physical activity. BT: SOC assessment every 2 mo for target behaviors; stage- and behavior-matched workbooks; assessment for depression, anxiety, and binge eating disorder every 6 mo. |

|

| Ross et al,27 2012 | 1. Usual Care | Routine visit with physician. | Usual schedule of meetings with physicians. | Provide general advice during routine office visit (typically once a year). | Diet, PA, and BT: Advice regarding benefits of PA for obesity reduction; at end of intervention, patients Invited to attend workshop on strategies to integrate PA and healthy eating into lifestyle. |

| 2. Behavioral Intervention | Health educators (in kinesiology) provided 15, 1 hr sessions during mo 1–6; monthly, 30–60 min sessions during mo 7–24, based on participants’ progress. | On-site, individual, tailored counseling. | None | Diet: Promote daily consumption of whole-grain foods, fruits, vegetables, legumes, and low-fat dairy products. PA: 45–60 min/day of moderate PA. BT: Motivational interviewing (mo 1–6); individually tailored counseling based on transtheoretical model and social cognitive theory; goal setting. |

|

BT= behavior therapy; MA= medical assistant; PA= physical activity; PCP= primary care provider; SOC= stage of change; NHLBI= National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Tsai et al17 randomly allocated participants to Usual Care (quarterly medical visits with a PCP) or Brief Counseling, which included PCP visits plus 8 brief individual counseling visits with a trained interventionist (i.e., medical assistant) during the first 6 months. Brief Counseling produced significantly greater mean weight loss than Usual Care at month 6 (4.4 vs 0.9 kg), with 47.8% and 0% of participants, respectively, losing ≥5% of baseline weight (P<.0001 for both outcomes). Neither mean nor categorical weight losses differed significantly at month 12 after a no-treatment follow-up period. Building on the prior study, Wadden et al18 compared Usual Care (i.e., quarterly PCP visits) to Brief Lifestyle Counseling, consisting of PCP visits plus brief monthly individual sessions with a trained interventionist (medical assistant). (The trial included a third group, Enhanced Brief Lifestyle Counseling, which is not described here because it included pharmacotherapy as a treatment option.) At month 6, participants in Usual Care and Brief Lifestyle Counseling lost a mean of 2.0 and 3.5 kg, respectively (P<.05). Weight losses at month 24 (1.7 and 2.9 kg, respectively) did not differ significantly.

Summary

No studies were found in which PCPs, working alone or with trained interventionists, provided intensive behavioral counseling as recommended by CMS (i.e., 14 sessions in 6 months). Trials by Tsai et al17 and Wadden et al18 both provided 3 PCP visits combined with 8 counseling sessions with a trained interventionist during the first 6 months. The interventions produced mean weight losses of 4.4 and 3.5 kg, respectively, at this time, which would meet CMS’s 3-kg criterion on average. Both studies used a modified version of the Diabetes Prevention Program protocol,9 included prescriptions for reduced calorie intake and ≥150 minutes/week of activity, and instructed participants to monitor these goals daily (Table 2). Kumanyika et al16 used a similar protocol but achieved a smaller mean weight loss, which may have been attributable, in part, to the study’s inclusion of primarily African-American women, who typically lose less weight in the first year than non-Hispanic white females.49–50 All three studies found that quarterly or less frequent behavioral counseling by PCPs alone induced mean losses of only 0.6 to 1.7 kg in 6 to 24 months.16–18

Traditional Behavioral Counseling: Trained Interventionists

In two trials,19,20 behavioral counseling was delivered by trained interventionists who (with one exception) were not employees of the primary care practices from which participants were recruited and who had limited or no direct collaboration with patients’ PCPs (Table 2). The studies differed in the frequency of intervention contact, as well as in the method of treatment delivery (i.e., face-to-face vs. remote delivery). Appel et al19 compared three interventions: Control; Remote-Support Only; or In-Person Support. Participants in Remote-Support Only initially were provided 12 brief weekly individual telephone sessions with trained interventionists (lifestyle coaches at a disease-management call center), followed by monthly calls through month 24 (i.e., total of 33 calls). Those assigned to In-Person Support were offered 12 weekly group or individual meetings the first 3 months, delivered by trained interventionists off-site (at an academic medical center) followed by an additional 45 meetings (some potentially by phone) through month 24 (Table 2). Participants in the two intervention groups also were provided a web-based program that included a curriculum of behavior change and encouraged self-monitoring of food intake and physical activity. Mean weight losses at month 6 were 0.4, 6.1, and 5.8 kg, respectively, with 14.2%, 52.7%, and 46.0% of participants, respectively, losing ≥5% (P<.001 for both interventions versus control for both outcomes). Weight losses were generally well maintained at month 24 (Table 1).

Ma et al20 randomly assigned participants to: Usual Care; a Coach-Led version of the Diabetes Prevention Program,9 delivered in weekly group sessions the first 3 months by a trained registered dietitian and a fitness instructor (with monthly to twice monthly phone or e-mail support thereafter); or a Self-Directed version of the same program in which participants were given 12 DVD sessions of the Diabetes Prevention Program. Mean weight losses at month 6 were 0.7, 6.6, and 4.3 kg, respectively, with 8.2%, 65.0%, and 44.5% of participants, respectively, losing ≥5% of baseline weight (P<.001 for both intervention groups versus Usual Care for both outcomes). Similar weight losses were maintained at month 24.43

Summary

Both Appel et al19 and Ma et al20,43 employed trained interventionists to provide high-intensity behavioral counseling during the first 6 months, either in person or by telephone. Both interventions appeared to meet the 14 treatment contacts (in 6 months) proposed by CMS (and the Obesity Guidelines6), were delivered following well-established behavioral protocols (e.g., Diabetes Prevention Program), and produced mean 6-month weight losses >5 kg that were generally well maintained at month 24. (In the Appel et al study, the potential contribution of the web-based program to the favorable results cannot be determined.) In both trials, the trained interventionists worked largely independently of the patients’ PCPs and were not, at least in one study,19 at the same physical location as PCPs. These practices likely would prevent coverage of the services under current CMS regulations.

Alternative Behavioral Counseling: Primary Care Practitioners/Trained Interventionists

The seven trials21–27 that follow did not prescribe both a reduced calorie diet (≥500 kcal/d deficit) and physical activity ≥150 minutes/week.6 In addition, in six21,23–27 of seven studies, behavioral counseling was guided principally by motivational interviewing46 or stages of change.47

A trial by Christian et al21 was the only one of the seven in which PCPs delivered behavioral counseling. The study allocated participants to usual medical care or to a computer-based assessment that obtained diet and physical activity histories, assessed patients’ motivations for weight loss, and provided a tailored report for patients and PCPs to review during two counseling visits (Table 2). At month 12, the control group gained a mean of 0.2 kg and the intervention group lost 1.5 kg (P=.002), with 8.5% and 26.3% of participants, respectively, losing ≥5% (P<.01).

Alternative Behavioral Counseling: Trained Interventionists

Bennett et al22 assigned participants to usual care or a behavioral intervention that was delivered by trained interventionists (i.e., community health educators) using brief monthly telephone calls the first year and bi-monthly calls in year 2. Participants were encouraged to monitor their progress using a study website or a telephone-based interactive voice response system. At month 6, usual care participants gained an average of 0.1 kg, compared with a loss of 1.3 kg in the intervention (P<.05). Similar weight changes were observed at month 24 (Table 1). de Vos et al23 compared participants assigned to a control group or to a tailor-made intervention that provided up to 4 hours of individual counseling with a registered dietitian (trained in motivational interviewing) and up to 20 1-hour group exercise classes, supervised by a physical therapist. (Patients were referred to these interventionists in the community.) At month 12, the control group gained an average of 0.6 kg, compared with a loss of 0.6 kg in the intervention (P=.014), with significantly more participants in the latter group losing ≥5% (11.0% vs. 18.7%, P<.027).

Greaves et al24 allocated participants to a control group or a motivational-interviewing-based intervention that provided up to 11 individual counseling sessions, delivered by a combination of in-person and telephone contacts. Trained interventionists included a registered nurse and graduate students in exercise science. At month 6, mean weight losses in the control and intervention groups were 1.8 and 0.3 kg, respectively (P<.05 in favor of the control group). However, more intervention than control participants lost ≥5% of baseline weight (7.2% vs 23.6%, P<.05). Hardcastle et al25 compared usual care to a motivational-interviewing-based intervention that offered up to five in-person, individual sessions with a trained exercise specialist or registered dietitian. At month 6, usual-care participants gained an average of 0.1 kg, compared with a loss of 0.7 kg in the intervention group (P<.05). At month 18 (following 12 months of no-treatment follow-up), both groups exceeded their baseline weight (by 1.4 kg and 0.5 kg, respectively; P>.05).25

Logue et al26 compared augmented usual care (i.e., control), which included four in-person semi-annual meetings with a trained registered dietitian over 24 months, to a more intensive program based on a transtheoretical model-chronic disease approach. The latter intervention included the four dietitian meetings plus monthly brief (15 minute) phone calls with a trained weight loss adviser (supervised by a psychologist) who reviewed participants’ stage of change with each of five targeted behaviors for the month. At month 24, participants in control and intervention groups lost a mean of 0.2 and 0.4 kg, respectively (P=.5).

Ross et al27 randomly assigned participants to usual care or a motivational-interviewing- based intervention that included 15 1-hour, in-person individual sessions in the first 6 months, 6 additional sessions from months 7–12, and variable contact from months 13–24 (based on participants’ needs). The intervention, delivered by trained exercise specialists, focused principally on increasing energy expenditure rather than restricting intake. Mean losses at month 6 were 0.7 and 2.4 kg, respectively (P<.002) and at month 24 were 0.6 and 1.2 kg, respectively (P=.33).

Summary

None of the trials of alternative behavioral counseling achieved a mean 6-month weight loss ≥3 kg, despite the provision during this time in one study27 of 15 in-person, 1 hour individual sessions. The provision of low intensity (< monthly) counseling2,3 in two trials21,25 and approximately moderate intensity (monthly) in a third,26 may have contributed to the small mean losses observed in these studies.

Intervention Effects and Relation of Treatment Intensity to Weight Loss

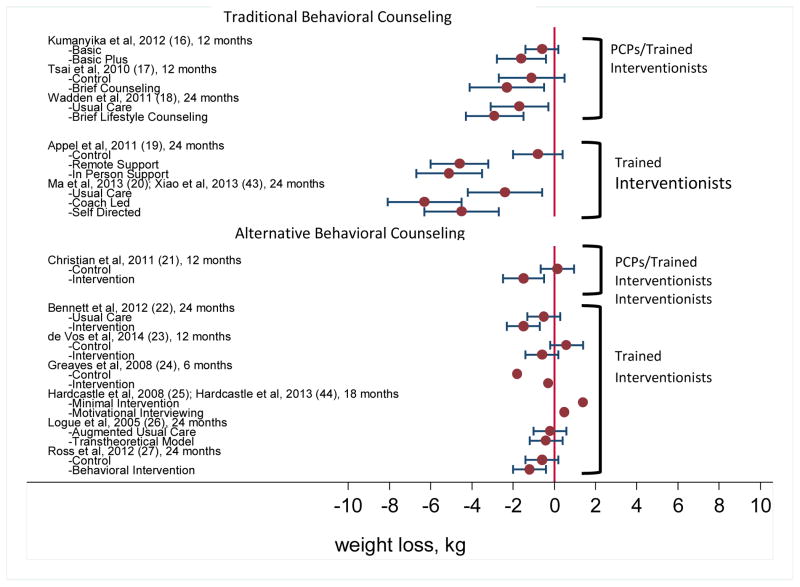

Across all 12 studies, the difference in weight loss between treatment and control groups (i.e., treatment – control) ranged from −1.5 kg (i.e., 1.5 kg greater weight loss in the control group) to 4.3 kg. The weight losses (relative to baseline) in each group of each trial are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The figure shows mean weight losses (in kg, with 95% confidence intervals) for intervention and control groups in each trial, as measured at the final assessment. Values to the left of “0” indicate weight loss. PCPs = primary care practitioners as defined by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Citations for each study, (Shown in parentheses) may be found in the references.

Four studies of traditional behavioral counseling prescribed participants an energy-restricted diet and specific physical activity goals (as recommended by the Obesity Guidelines6), were delivered using person-to-person counseling (i.e, face-to-face or by telephone), and reported weight losses at month 6.17–20 These trials are the most relevant for evaluating the intensity of treatment recommended by CMS (and the Obesity Guidelines6) during the first 6 months. The provision of more counseling sessions appeared to be associated with greater weight loss, ranging from 3.5 kg with 8 sessions18 to 6.6 kg with 15 contacts.20 The alternative behavioral counseling trials that provided 6-month data did not reveal as clear a dose-response relationship.

DISCUSSION

This review found no studies that evaluated the efficacy of intensive behavioral weight loss counseling (14 in-person sessions in 6 months) delivered by physicians and other CMS-eligible PCPs. Three trials16–18 provided approximately monthly brief counseling visits, which were delivered by trained medical assistants in collaboration with PCPs. Mean weight losses at 6 months ranged from 3.5 to 4.4 kg,17,18 with 48% of participants in one study losing ≥5% of baseline weight.17 Mean weight losses in these two trials17,18 declined over follow-up, and smaller 12-to 24-month losses (−0.6 to −1.7 kg) were observed when PCPs, working alone, provided quarterly or less frequent weight loss counseling.16–18

Two trials strongly supported the frequency of intervention contact recommended during the first 6 months by both CMS and the Obesity Guidelines6. Ma et al20 found that 12 weekly (face-to-face) group lifestyle modification sessions, followed by phone or e-mail contact every 2 to 4 weeks, produced a 6-month loss of 6.6 kg, with 65% of participants losing ≥5% of baseline weight. Appel et al19 observed that 15 brief phone sessions (with trained interventionists at a call center) yielded a loss of 6.1 kg at 6-months, with 52.7% of participants losing ≥5% weight, outcomes comparable to those produced by a more intensive face-to-face intervention. The Obesity Guidelines6 preferentially recommend face-to-face counseling, given its large evidence base of support.6 However, a growing literature suggests that telephone-delivered counseling is generally as effective as traditional face-to-face contact,51–53 potentially is more convenient and less costly for patients, and can reach more individuals in underserved areas.51

Results of this review also confirm the prescription of a comprehensive lifestyle intervention, recommended by the Obesity Guidelines,6 which includes a reduced calorie diet (e.g., ≥500 kcal/day deficit), ≥150 minutes/week of physical activity (e.g., brisk walking), and behavioral strategies to reach these targets.6,8–10 Smaller weight losses generally were observed in trials21–27 in this review that did not provide specific recommendations for both reducing energy intake and increasing expenditure, as well as offer behavioral strategies to achieve these goals. While alternative counseling approaches, such as motivational interviewing, have been shown to enhance weight loss when added to traditional behavioral counseling,48 results of this review underscore the importance of providing patients specific goals for energy restriction and expenditure.

There is a pressing need to identify the professional qualifications and training needed to provide effective behavioral weight loss counseling in primary care and other settings. Controlled trials are needed to compare the efficacy and costs of having behavioral counseling delivered by PCPs, other primary care staff (e.g., medical assistants, nurses), registered dietitians, other health professionals (e.g., health counselors, exercise specialists, psychologists), and potentially evidenced-based commercial programs.52,54 The Obesity Guidelines observed that behavioral weight loss counseling could be provided by trained interventionists (following structured protocols) from a variety of educational backgrounds.6 A recent initiative from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute55 should advance practice in this area by assessing different methods (including community-based programs) of providing behavioral counseling to overweight/obese patients encountered in primary care. This research likely will include the use of web- or smartphone-based applications,56,57 as well as cellular-connected smart scales,58 data from which potentially could be integrated into patients’ electronic health records.5,8

The CMS decision to provide intensive behavioral counseling for obese beneficiaries in primary care settings is a major advancement in the treatment of a disease that has long been overlooked. While this review found limited data to support the delivery of intensive behavioral weight loss counseling by physicians and other PCPs, these health professionals will continue to play a critical role in diagnosing obesity, evaluating its causes (including medications associated with weight gain), assessing and treating weight-related co-morbid conditions, and monitoring changes in health that occur with weight loss (including the need for medication adjustment). PCPs undoubtedly can learn to provide intensive behavioral counseling, like the other trained interventionists described in this review. However, ever increasing demands on PCPs’ time may favor their referring patients for behavioral counseling, an option suggested by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.2,3 This review, along with the Obesity Guidelines,6 has identified options for referring patients to trained interventionists who work in primary care, as well as a variety of other settings.

Acknowledgments

Role of the Sponsor: Thomas Wadden’s work on this project was supported, in part, by grant DK-65018 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Disease. The National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data, preparation of the manuscript for publication, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The authors would like to thank Alyssa Minnick, M.S., for editorial assistance, and Drs. Jun Ma and Lan Xiao for providing additional data (percentage of participants losing >5% of initial weight) from their 24-month follow-up study.43 This report is dedicated to the memory of Albert J. Stunkard, M.D.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs. Thomas Wadden, Meghan Butryn, and Adam Tsai had full access to all study data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: T. Wadden and A. Tsai. Acquisition of data: T. Wadden, M. Butryn, P. Hong, A. Tsai. Analysis and interpretation of data: T. Wadden, M. Butryn, P. Hong, A. Tsai. Drafting of the manuscript: T. Wadden, M. Butryn, A. Tsai. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: T. Wadden, M. Butryn, P. Hong, A. Tsai. Statistical analysis: M. Butryn, A. Tsai. Administrative, technical, or material support: P. Hong.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Thomas A. Wadden serves on advisory boards for Nutrisystem, Novo Nordisk, and Orexigen. He has received grant support, on behalf of the University of Pennsylvania, from these organizations and from Weight Watchers International. He also serves as an adviser to Johns Hopkins University on a proprietary weight loss program (Innergy) developed by university investigators. Meghan Butryn has received grant support, on behalf of Drexel University, from Shire Pharmaceuticals. Patricia Hong has no disclosures. Adam Tsai reports receiving donations of food products from Nutrisystem for a research study.

References

- 1.American Medical Association (AMA) Annotated reference committee reports. Reference Committee D; [Accessed on July 15, 2014]. Business of the American Medical Association Host of Delegates 2013 Annual Meeting. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/news/news/2013/2013-06-18-new-ama-policies-annual-meeting.page. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for obesity in adults: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):930–932. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moyer VA U S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for and management of obesity in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(5):373–378. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-5-201209040-00475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed December 14, 2013];Decision memo for intensive behavioral therapy for obesity (CAG-00423N) Available at: http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?&NcaName=Intensive%20Behavioral%20Therapy%20for%20Obesity&bc=ACAAAAAAIAAA&NCAId=253&.

- 5.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed on July 15, 2014];Services and supplies incident to a physician’s professional services: Conditions. 42 CFR § 410.26. 2011 http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2011-title42-vol2/pdf/CFR-2011-title42-vol2-sec410-26.pdf.

- 6.LeBlanc ES, O’Connor E, Whitlock EP, Patnode CD, Kapka T. Effectiveness of primary care-relevant treatments for obesity in adults: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(7):434–447. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-7-201110040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Donato KA, et al. Executive summary: Guidelines (2013) for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/America Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society Published by The Obesity Society and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Based on a systematic review from The Obesity Expert Panel, 2013. Obesity. 2014;22(25 Suppl 2):S5–39. doi: 10.1002/oby.20821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wadden TA, Webb VL, Moran CH, Bailer BA. Lifestyle modification for obesity: new developments in diet, physical activity, and behavior therapy. Circulation. 2012;125(9):1157–1170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.039453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knowler WC Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Look AHEAD Research Group. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):145–154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institutes of Health. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults – The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 3):51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haynes BR. Forming research questions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(9):881–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao G, Burke L, Spring B, et al. New and emerging weight management strategies for busy ambulatory settings. Circulation. 2011;124(10):1182–1203. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31822b9543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ali MK, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Williamson DF, et al. How effective were lifestyle interventions in real-world settings that were modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program? Health Aff. 2012;31(1):67–75. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoong SL, Carey M, Sanson-Fisher R, et al. A systematic review of behavioural weight-loss interventions involving primary-care physicians in overweight and obese primary-care patients (1999–2011) Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(11):2083–2099. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012004375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumanyika SK, Fassbender JE, Sarwer DB, et al. One-year results of the Think Health! study of weight management in primary care practices. Obesity. 2012;20(6):1249–1257. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai AG, Wadden TA, Rogers MA, et al. A primary care intervention for weight loss: results of a randomized controlled pilot study. Obesity. 2010;18(8):1614–1618. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer DB, et al. A two-year randomized trial of obesity treatment in primary care practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):1969–1979. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appel LJ, Clark JM, Yeh HC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):1959–1968. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma J, Yank V, Xiao L, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program lifestyle intervention for weight loss into primary care: a randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(2):113–121. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christian JG, Byers TE, Christian KK, et al. A computer support program that helps clinicians provide patients with metabolic syndrome tailored counseling to promote weight loss. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(1):75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett GG, Warner ET, Glasgow RE, et al. Obesity treatment for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients in primary care practice. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7):565–574. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Vos BC, Runhaar J, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Effectiveness of a tailor-made weight loss intervention in primary care. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53(1):95–104. doi: 10.1007/s00394-013-0505-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greaves CJ, Middlebrooke A, O’Loughlin L, et al. Motivational interviewing for modifying diabetes risk: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(553):535–540. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X319648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardcastle SJ, Taylor A, Bailey M, Castle R. A randomised controlled trial on the effectiveness of a primary health care counselling intervention on physical activity, diet and CHD risk factors. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Logue E, Sutton K, Jarjoura D, Smucker W, Baughman K, Capers C. Transtheoretical model-chronic disease care for obesity in primary care: a randomized trial. Obes Res. 2005;13(5):917–927. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross R, Lam M, Blair S, et al. Trial of prevention and reduction of obesity through active living in clinical settings. Arch Int Med. 2012;172(5):414–424. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christian JG, Bessesen DH, Byers TE, et al. Clinic-based support to help overweight patients with type 2 diabetes increase physical activity and lose weight. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(2):141–146. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ely AC, Banitt A, Befort C, et al. Kansas primary care weighs in: a pilot randomized trial of a chronic care model program for obesity in 3 rural Kansas primary care practices. J Rural Health. 2008;24(2):125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jebb SA, Ahern AL, Olson AD, et al. Primary care referral to a commercial provider for weight loss treatment versus standard care: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1485–1492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61344-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin PD, Rhode PC, Dutton GR, et al. A primary care weight management intervention for low-income African American women. Obesity. 2006;14(8):1412–1420. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Molennar EA, van Ameijden EJ, Vergouwe Y, et al. Effect of nutritional counselling and nutritional plus exercise counselling in overweight adults: a randomized trial in multidisciplinary primary care practice. Fam Pract. 2010;27(2):143–150. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore H, Summerbell CD, Greenwood DC, et al. Improving management of obesity in primary care: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2003;327(7423):1–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7423.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munsch S, Biedert E, Keller U. Evaluation of a lifestyle change programme for the treatment of obesity in general practice. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003;133(9–10):148–154. doi: 10.4414/smw.2003.10109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nanchahal K, Power T, Holdsworth E, et al. A pragmatic randomised controlled trial in primary care of the Camden Weight Loss (CAMWEL) programme. BMJ Open. 2012;2(3):1–17. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pritchard DA, Hyndman J, Taba F. Nutritional counselling in general practice: a cost effective analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(5):311–316. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.5.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ridgeway NA, Harvill DR, Harvill LM, et al. Improved control of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a practical education/behavior modification program in a primary care clinic. South Med J. 1999;92(7):667–672. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199907000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan DH, Johnson WD, Myers VH, et al. Nonsurgical weight loss for extreme obesity in primary care settings. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(2):146–154. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinstock RS, Trief PM, Cibula D, et al. Weight loss success in metabolic syndrome by telephone interventions: results from the SHINE Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(12):1620–1628. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2529-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whittemore R, Melkus G, Wagner J, et al. Translating the diabetes prevention program to primary care. Nurs Res. 2009;58(1):2–12. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31818fcef3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willaing I, Ladelund S, Jorgensen T, et al. Nutritional counselling in primary health care: a randomized comparison of an intervention by general practitioner or dietician. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11(6):513–520. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000152244.58950.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yardley L, Ware LJ, Smith ER, et al. Randomised controlled feasibility trial of a web-based weight management intervention with nurse support for obese patients in primary care. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(67):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao L, Yank V, Wilson SR, Lavori PW, Ma J. Two-year weight-loss maintenance in primary care-based Diabetes Prevention Program lifestyle interventions. Nutr Diabetes. 2013;3(e76):1–3. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2013.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hardcastle SJ, Taylor AH, Bailey MP, Harley RA, Hagger MS. Effectiveness of a motivational interviewing intervention on weight loss, physical activity and cardiovascular disease risk factors: a randomised controlled trial with a 12-month post-intervention follow-up. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10(40):1–16. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin PD, Dutton GR, Rhode PC, et al. Weight loss maintenance following a primary care intervention for low-income minority women. Obesity. 2008;16(11):2462–2467. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Evers KE. The transtheoretical model and stage of change. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1997. pp. 60–84. [Google Scholar]

- 48.West DS, DiLillo V, Bursac Z, Gore SA, Greene PG. Motivational interviewing improves weight loss in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1081–1087. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.West DS, Prewitt T, Bursac Z, Felix HC. Weight loss of black, white, and Hispanic men and women in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Obesity. 2008;16(6):1413–1420. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wadden TA, West DS, Neiberg RH, et al. One-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with success. Obesity. 2009;17(4):713–722. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perri MG, Limacher MC, Durning PE, et al. Extended-care programs for weight management in rural communities: the treatment of obesity in underserved rural settings (TOURS) randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(21):2347–2354. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.21.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rock CL, Flatt SW, Sherwood NE, Karanja N, Pakiz B, Thomson CA. Effect of a free prepared meal and incentivized weight loss program on weight loss and weight loss maintenance in obese and overweight women: a randomized control trial. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1803–1810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Donnelly JE, Goetz J, Gibson C, et al. Equivalent weight loss for weight management programs delivered by phone and clinic. Obesity. 2013;21(10):1951–1959. doi: 10.1002/oby.20334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heshka S, Anderson JW, Atkinson RL, et al. Weight loss with self-help compared with a structured commercial program: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289(14):1292–1298. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. [Accessed on July 31, 2014];PCORI to invest $20 million in studies to compare obesity treatment options for low-income, rural, and minority adults. Available at: http://www.pcori.org/2014/pcori-to-invest-20-million-in-studies-to-compare-obesity-treatment-options-for-low-income-rural-and-minority-adults/

- 56.Harvey-Berino J, West D, Krukowski R, et al. Internet delivered behavioral obesity treatment. Prev Med. 2010;51(2):123–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bacigalupo R, Cudd P, Littlewood C, et al. Interventions employing mobile technology for overweight and obesity An early systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2013;14(4):279–71. doi: 10.1111/obr.12006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steinberg DM, Tate DF, Bennett GG, et al. The efficacy of a daily self-weighing weight loss intervention using smart scales and email. Obesity. 2013;21(9):1789–1797. doi: 10.1002/oby.20396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]