Abstract

Purpose

To develop novel positron emission tomography (PET) agents for visualization and therapy monitoring of bacterial infections.

Procedures

It is known that maltose and maltodextrins are energy sources for bacteria. Hence, 18F-labelled maltose derivatives could be a valuable tool for imaging bacterial infections. We have developed methods to synthesize 4-O-(α-D-glucopyranosyl)-6-deoxy-6-[18F]fluoro-D-glucopyranoside (6-[18F]fluoromaltose) and 4-O-(α-D-glucopyranosyl)-1-deoxy-1-[18F]fluoro-D-glucopyranoside (1-[18F]fluoromaltose) as bacterial infection PET imaging agents. 6-[18F]fluoromaltose was prepared from precursor 1,2,3-tri-O-acetyl-4-O-(2′,3′,-di-O-acetyl-4′,6′-benzylidene-α-D-glucopyranosyl)-6-deoxy-6-nosyl-D-glucopranoside (5). The synthesis involved the radio-fluorination of 5 followed by acidic and basic hydrolysis to give 6-[18F]fluoromaltose. In an analogous procedure, 1-[18F]fluoromaltose was synthesized from 2,3, 6-tri-O-acetyl-4-O-(2′,3′,4′,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-glucopyranosyl)-1-deoxy-1-O-triflyl-D-glucopranoside (9). Stability of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and human and mouse serum at 37 °C was determined. Escherichia coli uptake of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose was examined.

Results

A reliable synthesis of 1- and 6-[18F]fluoromaltose has been accomplished with 4–6 and 5–8 % radiochemical yields, respectively (decay-corrected with 95 % radiochemical purity). 6-[18F]fluoromaltose was sufficiently stable over the time span needed for PET studies (~96 % intact compound after 1-h and ~65 % after 2-h incubation in serum). Bacterial uptake experiments indicated that E. coli transports 6-[18F]fluoromaltose. Competition assays showed that the uptake of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose was completely blocked by co-incubation with 1 mM of the natural substrate maltose.

Conclusion

We have successfully synthesized 1- and 6-[18F]fluoromaltose via direct fluorination of appropriate protected maltose precursors. Bacterial uptake experiments in E. coli and stability studies suggest a possible application of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose as a new PET imaging agent for visualization and monitoring of bacterial infections.

Keywords: Bacterial infection, Imaging, Positron emission tomography, Maltose

Introduction

Although there are significant developments in microbial biology, bacterial infections are on the rise throughout the world [1]. Due to poor diagnosis of bacterial infections and the development of drug resistance, bacterial infections continue to remain a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. It is important to distinguish bacterial infection from nonbacterial inflammation [2]. Although imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide excellent structural images, they are unable to discriminate these two conditions [3]. Molecular imaging modalities such as single-photon emission computer tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET) with suitable radiotracers allow the differential diagnoses of bacterial infections. Furthermore, SPECT and PET may be used for the early detection and monitoring of the treatment with antibiotics. Ciprofloxacin is a very effective antibiotic which is active against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. 18F-Ciprofloxacin has been synthesized and evaluated for imaging bacterial infection. However, PET infection imaging in patients with [18F]ciprofloxacin was unsuccessful [4, 5]. The use of 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose (18FDG) for imaging bacterial infection via glucose metabolism of activated white blood cell mechanism has been reviewed by Sasser et al. [6] and Petruzzi et al. [7]. However, 18FDG imaging cannot distinguish infection from inflammation. 1-(2′-Deoxy-2′-fluoro-β-D-arabinofuranosyl)-5-[124I]iodouracil (FIAU) is a very promising bacterial infection imaging candidate reported by Diaz et al. [8]. FIAU is a substrate for bacterial thymidine kinase. FIAU is also a substrate for mammalian mitochondrial thymidine kinase and results in nonspecific uptake in certain tissues. Ning et al. [9] reported fluorescent bacterial infection imaging probes named maltodextrin-based probes (MDPs). These probes made of maltohexose conjugated to fluorophore were able to detect as little as 105 CFU (colony forming unit) of bacteria. It is well known that maltose and maltodextrins are energy source for bacteria [10]. Maltose and maltodextrins are taken up by bacteria via the maltose transporter system which is not present in mammalian cells [11]. We therefore hypothesize that 18F-labelled maltose derivatives would be ideal PET tracers for imaging bacterial infection.

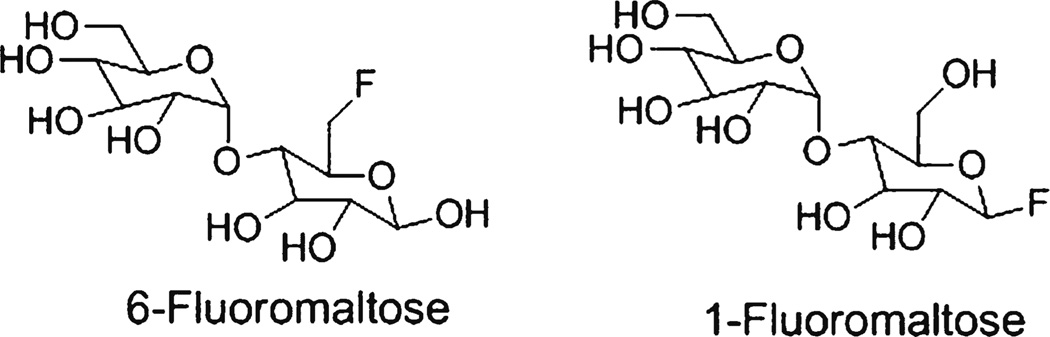

Although the syntheses of 1-fluoromaltose [12–15] and 6-fluoromaltose [12, 16–18] (Fig. 1) has been described, the preparation of an 18F-labelled fluoromaltose derivative has not been reported yet. Here, we report the synthesis of 4-O-(α-D-glucopyranosyl)-6-deoxy-6-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucopyranoside (6-[18F]-fluoromaltose, 7) and 4-O-(α-D-glucopyranosyl)-1-deoxy-1-[18F]fluoro-D-glucopyranoside (1-[18F]fluoromaltose, 11) as potential bacterial infection PET imaging agents and then perform pilot studies to show that 6-[18F]fluoromaltose is taken up by bacteria.

Figure 1.

Fluorinated maltose derivatives.

Materials and Methods

General

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). 6-Floro- and 1-fluoromaltose were synthesized according to literature procedures [12–18] (Fig. 1). 6-[18F]fluoromaltose was prepared from precursor 1,2,3-tri-O-acetyl-4-O-(2′,3′,-di-O-acetyl-4′,6′-benzylidene-α-D-glucopyranosyl)-6-deoxy-6-nosyl-D-glucopranoside (5) (Schemes 1 and 2). Likewise, 1-[18F]fluoromaltose was synthesized from 2,3, 6-tri-O-acetyl-4-O-(2′,3′,4′,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-glucopyranosyl)-1-deoxy-1-O-triflyl-D-glucopranoside (9), the 1-[18F]fluoromaltose precursor (Scheme 3). 6-[18F]- and 1-[18F]fluoromaltose purifications were performed on a Dionex HPLC system (Dionex Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA) equipped with a Dionex P680 quaternary gradient pump and Knauer K-2001 UV detector (Berlin, Germany) set at 254 nm and radioactivity detector (Carroll & Ramsey Associates, model 105S, Berkeley, CA). Semipreparative HPLC reverse phase column (Phenomenex, Gemini, Hesperia, CA, C18, 5 µm, 10×250 mm) with the mobile phase water/acetonitrile (99:1) and flow rate of 3 ml/min under isocratic condition was used. Radioactivity measurements were performed by a CRC-15R PET dose calibrator (Capintec Inc., Ramsey, NJ). Radio-TLC chromatographs were done on a Bioscan AR-2000 model. Analytical HPLC was carried out using Dionex Ultimate 3000 system with diode array detector equipped with Ultimate 3000 autosampler and radioactivity detector (Carroll & Ramsey Associates, model 105S, Berkeley, CA). Analytical HPLC reverse phase column (Phenomenex, Gemini, Hesperia, CA, C18, 5 µm, 4.6×250 mm) with the mobile phase 2 mM ammonium formate, 0.1 % HCOOH, pH 5.6–5.7/methanol (98:2) or H2O/CH3CN (99:1) and flow rate of 1 ml/min under isocratic condition was used for analysis of 1- and 6-[18F]fluoromaltose.

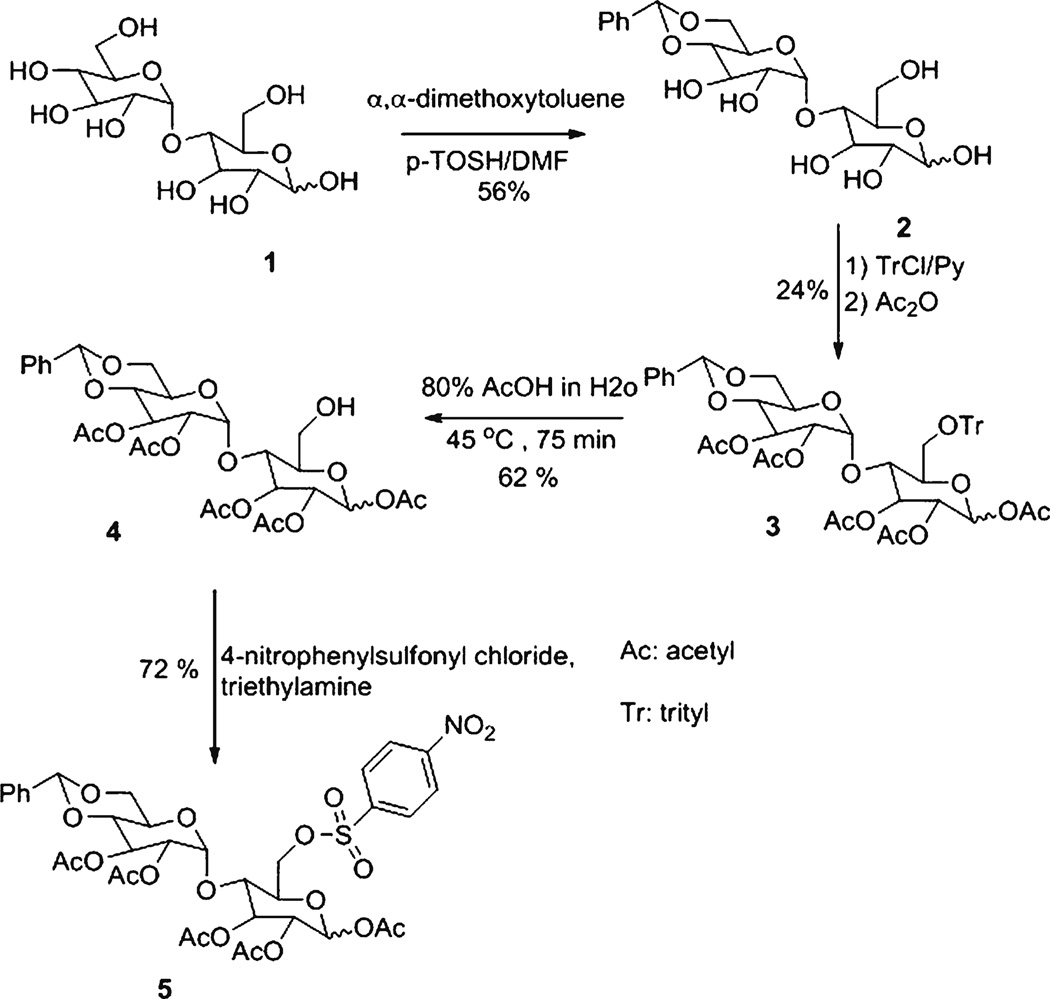

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 1,2,3-tri-O-acetyl-4-O-(2′,3′,-di-O-acetyl-4′,6′-benzylidene-α-D-glucopyranosyl)-6-deoxy-6-O-nosyl-D-glucopranoside (5), the 6-[18F]fluoromaltose precursor

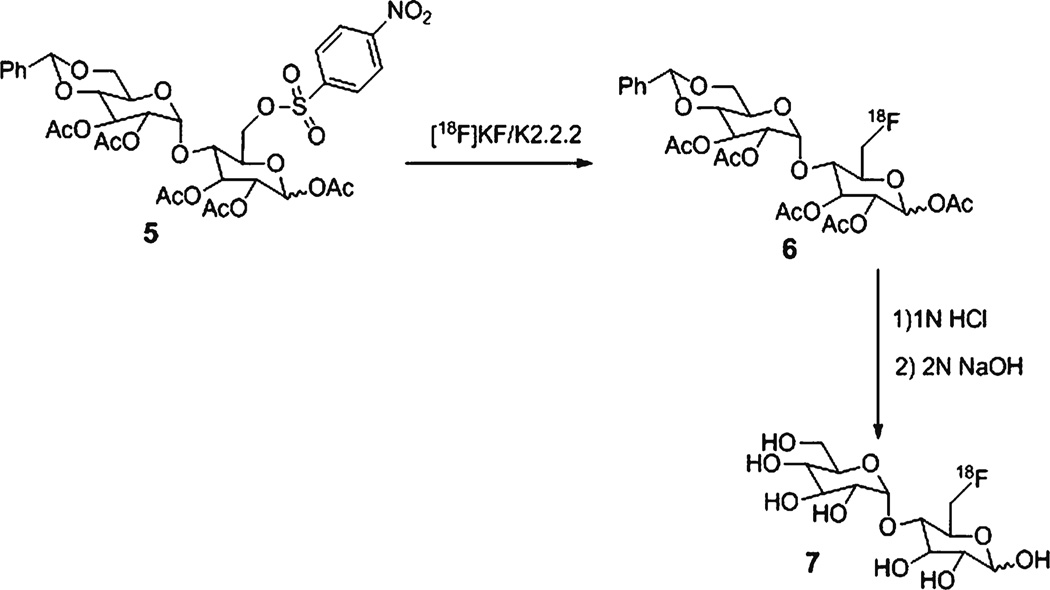

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 4-O-(α-D-glucopyranosyl)-6-deoxy-6-[18F]fluoro-D-glucopyranoside (6-[18F]fluoromaltose, 7)

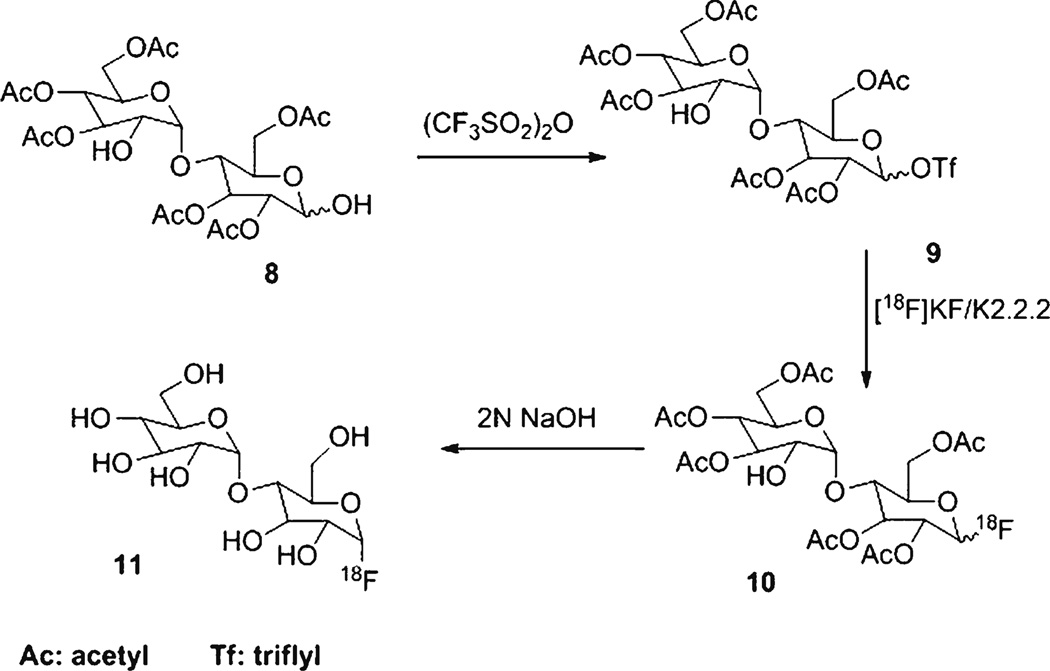

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 4-O-(α-D-glucopyranosyl)-1-deoxy-1-[18F]fluoro-D-glucopyranoside (1-[18F]fluoromaltose, 11)

1H and 19F NMR spectra were done on Mercury 400 MHz spectrometer. Electron spray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry was performed by Vincent Coates Foundation Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, Stanford University.

No-carrier-added [18F]fluoride was prepared by the 18O(p, n)18F nuclear reaction on a GE PET tracer cyclotron. [18F]Fluoride processing and synthesis of 6 (Scheme 2) and 2,3,6-tri-O-acetyl-4-O-(2′,3′,-di-O-acetyl-4′,6′-benzylidene-α-D-glucopyranosyl)-1-deoxy-1-[18F]fluoro-D-glucopranoside (10) (Scheme 3) were completed in the GE TRACER lab FX-FN synthesis module (GE Medical System, Milwaukee, WI).

1,2,3-Tri-O-Acetyl-4-O-(2′,3′,-Di-O-Acetyl-4′,6′-Benzylidene-α-D-Glucopyranosyl)-6-Deoxy-6-O-Trityl-D-Glucopranoside (3)

A solution of 4′,6′-benzylidene-α-D-glucopyranosyl-D-glucopranoside [12, 16] (2,187 mg, 0.43 mmol) in dry pyridine (1.5 ml) containing trityl chloride (184 mg, 0.66 mmol) was stirred at room temperature for 7 h. After addition of acetic anhydride (1.5 ml), the reaction mixture was stirred in room temperature for 24 h. Finally, the reaction mixture was evaporated under vacuum and the residue was co-evaporated with toluene. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (silica gel) using 70:30 ethyl acetate and hexane as the eluent to afford 91 mg (24 %) of 3 as a foam with α/β=0.7/1. α-Anomer, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm: 7.15–7.44 (m, 20 H, H-phenyl), 6.33 (d, J=3.8 Hz, 1H, H-1), 5.49 (broad t, J=9.2 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.39 (s, 1H, CH-phenyl), 5.21–5.29 (m, 4H, H-1’, H-2, H-2′ and H-3′), 4.99–5.05 (m, 1H, H-6′a), 4.79–4.80 (m, 1H, H-4), 3.98–4.07 (m, 1H, H-6a), 3.69–3.80 (m, 1H, H-5′), 3.54–3.62 (m, 2H, H-6b and H-5), 3.41–3.51 (m, 2H, H-6′b and H-4′), and 2.20–2.21 (5 s, 15H, CH3); β-anomer, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm: 7.15–7.44 (m, 20 H, H-phenyl), 5.75 (d, J=7.6 Hz, 1H, H-1), 5.39 (s, 1H, CH-phenyl), 5.21–5.29 (m, 5H, H-1′, H-2, H-2′, H-3 and H-3′), 4.99–5.05 (m, 1H, H-6′a), 4.79–4.80 (m, 1H, H-4), 3.98–4.07 (m, 1H, H-6a), 3.69–3.80 (m, 1H, H-5′), 3.54–3.62 (m, 1H, H-6b), 3.41–3.51 (m, 2H, H-6′b and H-4′), 3.24–3.31 (m, 1H, H-5), and 2.00–2.21 (5 s, 15H, CH3).

1,2,3-Tri-O-Acetyl-4-O-(2′,3′,-Di-O-Acetyl-4′,6′-Benzylidene-α-D-Glucopyranosyl)-D-Glucopranoside (4)

Compound 3 (76 mg, 0.086 mmol) in 2 ml of aqueous acetic acid (80 % in water) was stirred for 75 min at 45 °C [19]. The mixture was concentrated under vacuum and the crude benzylidene 4 purified by column chromatography (silica gel) using 94:6 chloroform and methanol (90 % in water) as the eluent to afford 34 mg (62 %) of 4 as colorless viscous oil with α/β=1.1/1. α-Anomer, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm: 7.32–7.46 (m, 5 H, H-phenyl), 6.25 (d,1H, J=4.0 Hz, H-1), 5.56 (t, J=9.6 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.50 (s, 1H, CH-phenyl), 5.44–5.52 (m, 1H, H-5′), 5.42 (d, J=4.4 Hz, 1H, H-1′), 5.33 (t, J=9.2Hz, 1H, H-2), 4.84–5.00 (m, 3H, H-2′, H-5 and H-6a′), 4.31–4.38 (m, 1H, H-6a), 4.2 (t, J=9.4 Hz, 1H, H-3′), 3.85–4.00 (m, 2H, H-4, H-6b), 3.69–3.77 (m, 1H, H-6′b), 3.60–3.68 (m, 1H, H-4′), and 1.99–2.21 (5 s, 15H, CH3); β-anomer, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm: 7.32–7.46 (m, 5 H, H-phenyl), 5.73 (d, J=8.4Hz, 1H, H-1), 5.56 (t, J=9.6 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.50 (s, 1H, CH-phenyl), 5.44–5.52 (m, 1H, H-5′), 5.42 (d, J=4.4 Hz, 1H, H-1′), 5.33 (t, J=9.2Hz, 1H, H-2), 4.84–5.00 (m, 2H, H-2′ and H-6a′), 4.31–4.38 (m, 1H, H-6a), 4.2 (t, J=9.4 Hz, 1H, H-3′), 3.85–4.00 (m,3H, H-4, H-5, H-6b), 3.69–3.77 (m, 1H, H-6′b), 3.60–3.68 (m, 1H, H-4′), and 1.99–2.21 (5 s, 15H, CH3). ESI-MS: Calcd for [C29H36O16]: 640.59: found: [M + Na] 663.59

1,2,3-Tri-O-Acetyl-4-O-(2′,3′,-Di-O-Acetyl-4′,6′-Benzylidene-α-D-Glucopyranosyl)-6-Deoxy-6-O-Nosyl-D-Glucopranoside (5)

4-Nitrophenylsulfonyl chloride (98 mg, 0.442 mmol) was added to a solution of 4 (54 mg, 0.084 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1.0 ml) containing triethylamine (84 µl) [20]. The mixture was stirred for 70 min at 0–5 °C and concentrated under vacuum. The crude nosylate 5 was purified by column chromatography (silica gel) using 1:1 ethyl acetate and hexane as the eluent to afford 50 mg (72%) of 5 as colorless viscous oil with α/β=1.1/1. α-Anomer, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm: 8.24 (d, J=9.2 Hz, 2H, H-nitrophenyl), 8.10 (d, J=9.00 Hz, 2H, H-nitrophenyl), 7.36–7.48 (m, 5 H, H-phenyl), 6.03 (d, 1H, J=3.7 Hz, H-1), 5.52 (s, 1H, CH-phenyl), 5.42–5.49 (m, 1H, H-3), 5.33–5.42 (m, 2H, H-1′ and H-3′), 5.22 (t, J=9.2 Hz, 1H, H-2), 4.87 (dd, J=10 Hz, J=4.1 Hz, 1H, H-2′), 4.86 (dd, J=9.6 Hz, J=4.2 Hz, 1H, H-6a′), 4.77 (t, J=9.0 Hz, 1H, H-4), 4.68 (dd, J=10 Hz, J=3.8 Hz, 1H, H-6a), 4.38–4.49 (m, 2H, H-5′ and H-5), 4.00–4.08 (m, 1H, H6b), 3.69–3.80 (m, 2H, H-4′ and H-6′b), and 1.96–2.17 (5 s, 15H, CH3); β-anomer, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm: 8.20 (d, J=9.0 Hz, 2H, H-nitrophenyl), 8.10 (d, J=9.00 Hz, 2H, H-nitrophenyl), 7.36–7.48 (m, 5 H, H-phenyl), 5.63 (d, 1H, J=8.1 Hz, H-1), 5.52 (s, 1H, CH-phenyl), 5.33–5.42 (m, 2H, H-1′ and H-3′), 5.22 (t, J=9.2 Hz, 1H, H-2), 4.87 (dd, J=10 Hz, J=4.1 Hz, 1H, H-2′), 4.86 (dd, J=9.6 Hz, J=4.2 Hz, 1H, H-6a′), 4.77 (t, J=9.0 Hz, 1H, H-4), 4.68 (dd, J=10 Hz, J=3.8 Hz, 1H, H-6a), 4.38–4.49 (m, 2H, H-3, H-5′), 4.00–4.08 (m, 1H, H6b), 3.69–3.80 (m, 2H, H-4′ and H-6′b), 3.61–3.68 (m, 1H, H-5), and 1.96–2.17 (5 s, 15H, CH3). High-resolution MS: Calcd. MNa + for C35H39NaO20NS: 848.1687: found: 848.1694.

4-O-(α-D-Glucopyranosyl)-6-Deoxy-6-[18]fluoro-D-Glucopyranoside (6-[18F]Fluoromaltose, 7)

No-carrier-added [18F]fluoride trapped on a QMA cartridge was eluted with a solution of K2CO3 (3.5 mg) and kryptofix 2.2.2 (15 mg) in water (0.1 ml) and acetonitrile (0.9 ml). The solvent was removed under vacuum at 65 °C, and to the anhydrous residue was added a solution of nosylate precursor 5 (4–5 mg) in acetonitrile (0.8 ml). The mixture was heated for 10 min at 80 °C. After cooling to room temperature, 10 ml of water was added and the solution passed through a light C-18 Sep-pak cartridge (Water) and the crude protected 6-[18F]fluoromaltose (6) eluted by passing 3 ml of acetonitrile trough the cartridge. After passing a solution of 6 in acetonitrile through a light neutral alumina Sep-pack, it was concentrated and hydrolyzed first by 1 N HCl at 110 °C for 10 min then by 2 N NaOH in room temperature for 4 min to afford crude 6-[18F]fluoromaltose 7. The neutral solution of 7 was injected onto a C18 reverse phase semipreparative HPLC column. The product 6-[18F]fluoromaltose (7) was collected at 6 min. After evaporation of solvent, the residue was constituted in saline. The radiochemical purity of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose was determined by reverse phase analytical HPLC method and was more than 95 % pure. Also, radio-TLC of 7 (silica gel plate, CH3CN/H2O; 70:30, Fig. 2) gave an Rf value of 0.5. The radio synthesis time was 120 min and the radiochemical yield was 5–8 % (decay-corrected).

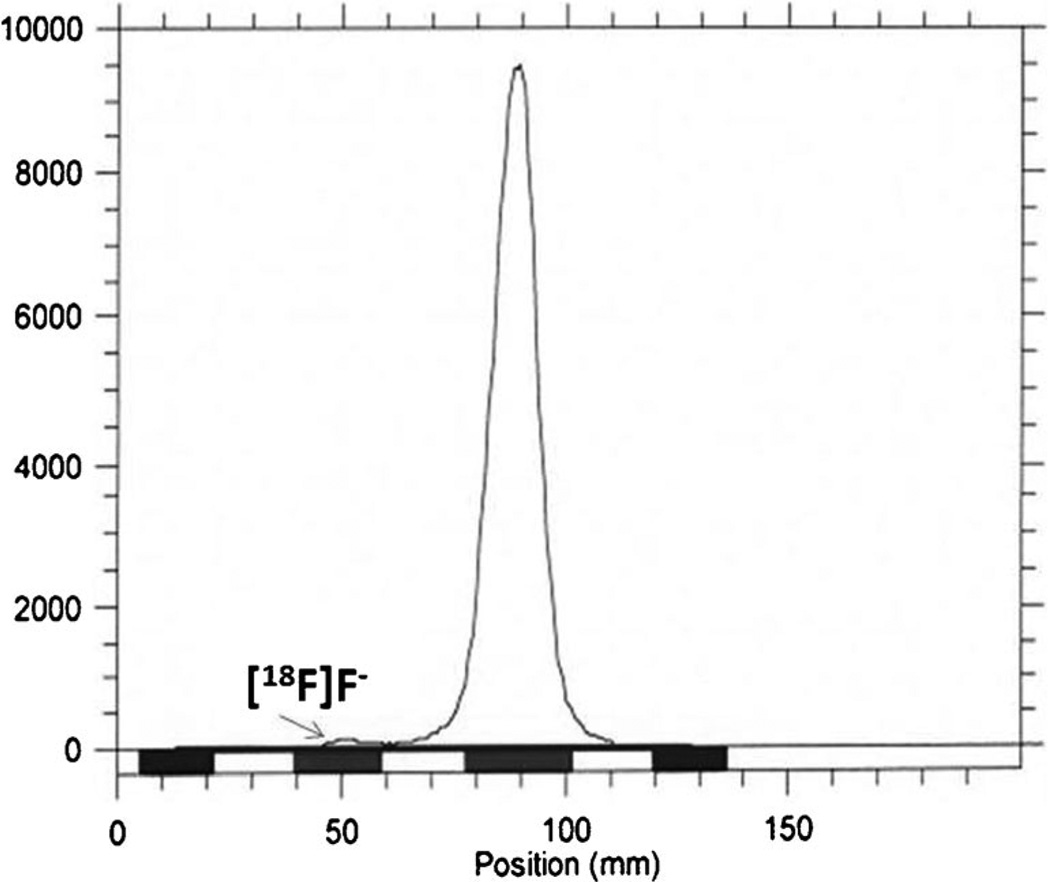

Figure 2.

Radio-TLC of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose7 (silica gel plate, CH3CN/H2O; 70:30) gave an Rf value of 0.5.

2,3,6-Tri-O-Acetyl-4-O-(2′,3′,4′, 6′-Tetra-O-Acetyl-α-D-Glucopyranosyl)-1-Deoxy-1-O-Triflyl-D-Glucopranoside (9)

Trifuorometanesulfonic anhydride (12 µl, 0.071 mmol) was added into a solution of 8 [12, 13] (40 mg, 0.063 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (0.17 ml) containing pyridine (12 µl, 0.148 mmol) at 0–5 °C. The mixture was stirred for 3 h at room temperature and diluted with 1.5 ml of CH2CL2. The CH2Cl2 solution was successively washed with cold saturated NaHCO3 (1.5 ml) and cold water (1.5 ml). The organic layer was dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated under vacuum and the crude triflate 9 was purified by column chromatography (silica gel) using 1:1 ethyl acetate and hexane as the eluent to afford 14.5 mg (30 %) of 9 as colorless foam with α/β=1/3. α-Anomer, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm: 6.40 (d, J=3.8 Hz, 1H, H-1), 5.68 (dd,, J=9.6 Hz, J=8.6 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.44 (d, 1H, J=4.1 Hz, H-1′), 5.32–5.39 (m, 1H, H-3′), 4.97 (dd, J=9.2 Hz, J=8.2 Hz, 1H, H-4′), 4.86–4.90 (m, 1H, H-2′), 4.78 (dd, 1H, J=9.8 Hz, J=3.7 Hz, 1H, H-2), 4.45 (dd, J=12.4 Hz, J=2.3 Hz, 1H, H-6a), 4.19–4.26 (m, 3H, H-5, H-6′a and H-6b), 4.00–4.10 (m, 1H, H4), 3.90–3.95 (m, 1H, H-6′b), 3.80–3.86 (m, 1H, H5′), and 2.00–2.26 (7 s, 21H, CH3); and 19F NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: −75.1 (s). β-anomer, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm: 5.74 (d, J=8.2 Hz, 1H, H1), 5.41 (d, J=4.1 Hz, 1H, H1′), 5.35 (t, J=9.9 Hz, 1H, H3), 5.29 (t, J=9.0 Hz, 1H, H-3′), 5.06 (t, J=10 Hz, 1H, H-4′), 4.86 (dd, J=10.5 Hz, J=4.1 Hz, 1H, H-2′), 4.78 (dd, 1H, J=9.8 Hz, J=3.7 Hz, 1H, H-2), 4.45 (dd, J=12.4 Hz, J=2.3 Hz, 1H, H-6a), 4.19–4.26 (m, 3H, H-5, H-6′a and H-6b), 4.00–4.10 (m, 1H, H4), 3.90–3.95 (m, 1H, H-6′b), 3.80–3.86 (m, 1H, H5′), and 2.00–2.26 (7 s, 21H, CH3); and 19F NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: −75.1 (s). High-resolution MS: Calcd. MNa+ for C27H35O20SF3Na: 791.1287: found: 791.1318.

4-O-(α-D-Glucopyranosyl)-1-Deoxy-1-[18F] Fluoro-D-Glucopyranoside (1-[18F] Fluoromaltose, 11)

No-carrier-added [18F]fluoride trapped on a QMA cartridge was eluted with a solution of K2CO3 (3.5 mg) and kryptofix 2.2.2 (15 mg) in water (0.1 ml) and acetonitrile (0.9 ml). The solvent was removed under vacuum at 65 °C, and to the anhydrous residue was added a solution of triflate precursor 9 (4–5 mg) in acetonitrile (0.8 ml). The mixture was heated for 10 min at 80 °C. After cooling to room temperature, 10 ml of water was added and the solution passed through a light C-18 Sep-pak cartridge (Water) and the crude protected 1-[18F]fluoromaltose (10) eluted by passing 3 ml of acetonitrile trough the cartridge. The crude 10 was concentrated and hydrolyzed by 0.5 ml of 2 N NaOH in room temperature for 4 min to afford crude 1-[18F]fluoromaltose 11. After addition of 1 ml of 1 N HCl, the neutral solution of 11 was injected onto a C18 reverse phase semipreparative HPLC column. The product 1-[18F]fluoromaltose (11) was collected at 7 min. After evaporation of solvent, it was reconstituted in saline. The radiochemical purity of 1-[18F]fluoromaltose was determined by reverse phase analytical HPLC method and was more than 95 %. Also, radio-TLC of 11 (silica gel plate, CH3CN/H2O; 70:30) gave an Rf value of 0.46. The radio synthesis time was 110 min and the radiochemical yield was 4–6 % (decay-corrected).

Stability of 6-[18F]Fluoromaltose in Serum

Serum (human or mouse) was centrifuged at 4 °C, with speed of 13,000 rpm for 10 min. Supernatant (330 µl) was transferred to an Eppendorf vial containing 20 µl of formulated radiolabeled 6-[18F]fluoromaltose (50–100 µCi). For control, the same volume of radiolabeled compound in 330 µl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was used. After vortexing the radiolabeled mixtures, 70-µl aliquots were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and incubated at 37 °C. At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, and 60 min), 140 µl of ice-cold methanol was added to corresponding samples to stop metabolism. After vortexing and centrifuging samples (10 min, 13,000 rpm), the supernatants were transferred to HPLC vials for HPLC analysis.

In Vitro Uptake Assays

A strain of Escherichia coli (ATCC33456) and a mammalian cell line (EL4) were exposed to 1-[18F]fluoromaltose, 6-[18F]fluoromaltose, or [14C]maltose. The uptake studies were done in Hank’s buffered saturated solution (HBSS) which has a physiological level of glucose (5 mM). All bacteria and cells were then washed in 1× PBS and lysed using a bacterial lysis solution (Bug Buster, EMD), and radioactivity of each well was determined by gamma counter for 18F and liquid scintillation counting for 14C samples. All experiments were performed in triplicate and uptake is expressed in percent uptake per microgram of protein. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad software. For blocking experiments, radiolabeled compounds were co-incubated with 1 mM of maltose or 1 mM of 1-fluoromaltose.

Results

Chemistry

Scheme 1 shows the synthesis of 1,2,3-tri-O-acetyl-4-O-(2′,3′,-di-O-acetyl-4′,6′-benzylidene-α-D-glucopyranosyl)-6-deoxy-6-O-nosyl-D-glucopranoside (5), the 6-[18F]fluoromaltose precursor. Treatment of benzylidene 2 [12] with trityl chloride followed by acetylation produced 1, 2, 3-tri-O-acetyl-4-O-(2′,3′,-di-O-acetyl-4′,6′-benzylidene-α-D-glucopyranosyl)-6-deoxy-6-O-trityl-D-glucopranoside (3) in 24 % yield. Selective de-protection of 3 resulted 4 in 62 % yield. 4 was nosylated (standard nosylation procedure) [20] at 0–5 °C to afford 5 in 72 % yield. We applied synthesis of FDG precursor procedure [21] for synthesis of triflate 8. Scheme 3 shows the synthesis of 2,3, 6-tri-O-acetyl-4-O-(2′,3′,4′,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-glucopyranosyl)-1-deoxy-1-O-triflyl-D-glucopranoside (9), the 1-[18F]fluoromaltose precursor. Treatment of hepta-peracetyl-1-hydroxymaltose 8 [12, 13] with trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride produced 9 in 30 % yield.

Radiochemistry

Fluorine-18-labeled maltose derivative 6 (Scheme 2) was prepared by nucleophilic displacement of the nosylate group in 5 by [18F]fluoride ion in acetonitrile at 80 °C for 10 min. Initial purification of [18F]6 was performed via a light C-18 Sep-pak cartridge. After passing the solution of [18F]6 in acetonitrile through a light neutral alumina Sep-pack, it was concentrated and smoothly hydrolyzed by acid (1 N HCl) at 110 °C for 10 min. After removal of the solvent under vacuum, the remaining acetyl groups in 6 were hydrolyzed by base (2 N NaOH) at room temperature for 4 min to yield 6-[18F]fluoromaltose 7. The radiochemical yield was 5–8 % (decay-corrected, n=8). Radio-TLC of 7 (Fig. 2) gave an Rf value of 0.5 which is identical to the Rf value of 6-fluoromaltose [12] under the same TLC condition. Likewise, 1-[18F]-labelled maltose derivative 10 (Scheme 3) was prepared by nucleophilic displacement of the triflate group in precursor 9 by [18F]fluoride ion in acetonitrile at 80 °C for 10 min. 10 was purified by C-18 Sep-pak and de-protected with 2 N NaOH to afford 4-O-(α-D-glucopyranosyl)-1-deoxy-1-[18F]fluoro-D-glucopyranoside (1-[18F]fluoromaltose, 11). However, only the α-anomer was stable under the purification conditions. It has been reported that only the α-anomer of cold 1-fluoromatose is stable in room temperature [12].

Stability of 6-[18F]Fluoromaltose in Serum

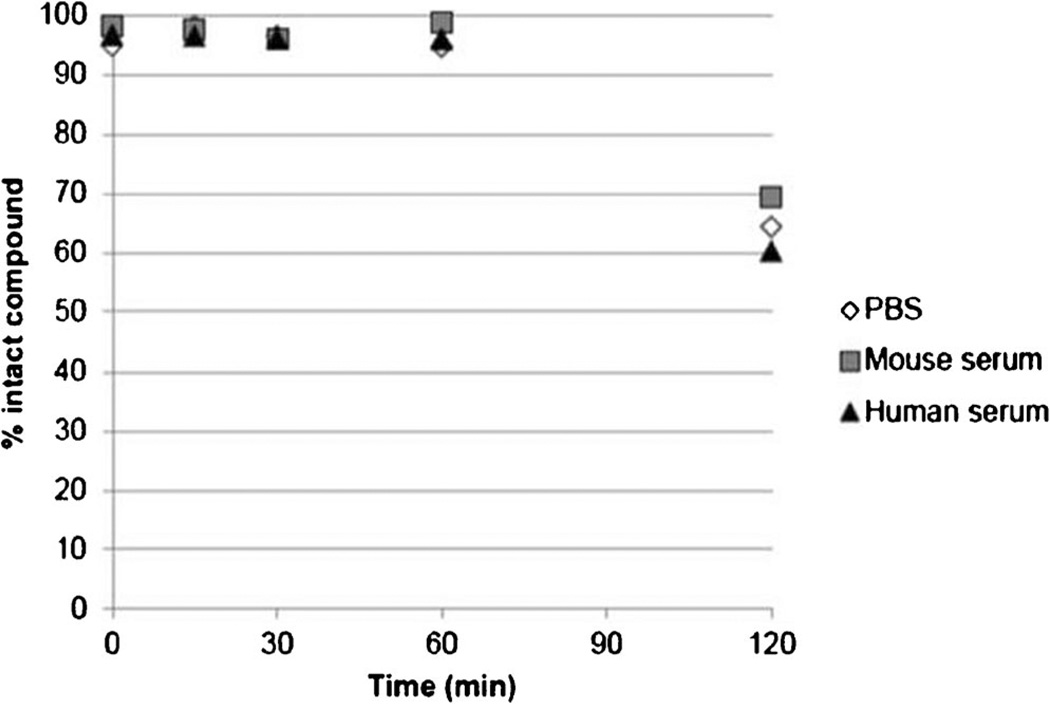

The percentage of intact 6-[18F]fluoromaltose in PBS and human and mouse serum at 37 °C was determined by HPLC. Figure 3 shows that the amount of intact 6-[18F]fluoromaltose decreased from 96 % at 1-h incubation to 65 % after 2 h. Also, one can determine the stability by using radio-TLC to demonstrate the presence of [18F]F− (Fig. 2).

Figure 3.

Stability of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose 7 in PBS and mouse and human serum at 37 °C.

In Vitro Uptake Assays

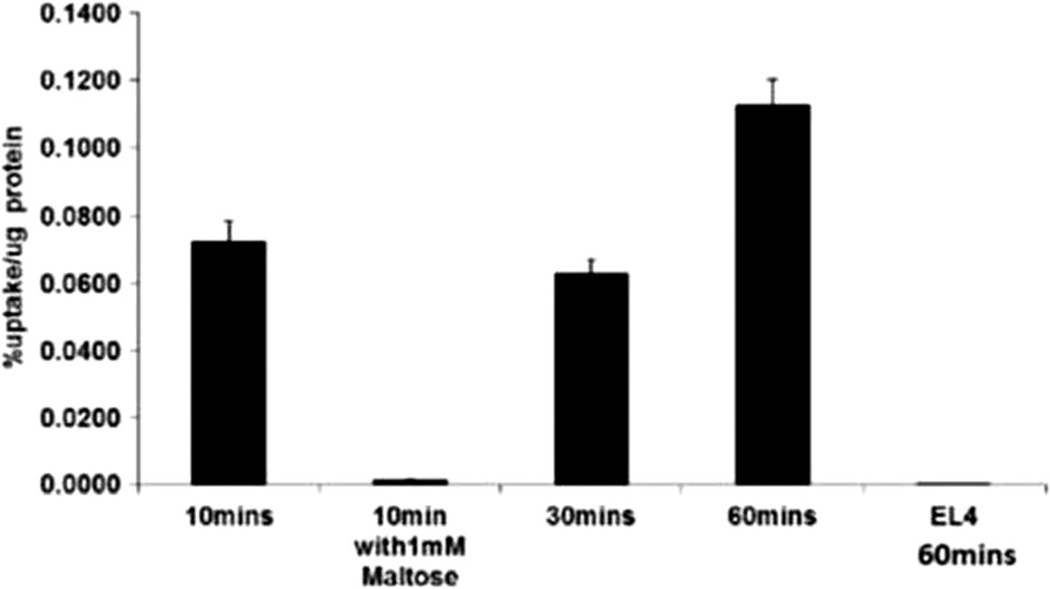

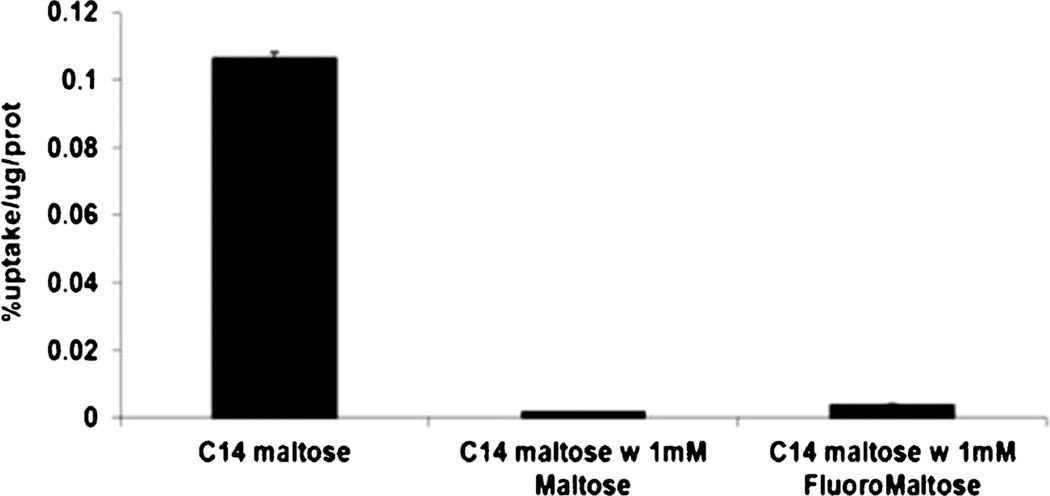

To evaluate the ability of bacteria and cells to take up 6-[18F]fluoromaltose (7), a strain of E. coli and a mammalian cell line (EL4) were exposed to 7. Figure 4 shows that the uptake of 7 by E. coli is time dependent. In EL4 cells, uptake was minimal after 60-min incubation with tracer. The uptake in E. coli could also be blocked by co-incubation with 1 mM of maltose, the natural substrate of the transporter (98 % blocking, p<0.0003). Likewise, 14C-maltose uptake in E. Coli was blocked with both 1 mM maltose and 1-fluoromaltose (Fig. 5). Here we allowed bacteria to take up 14C-labeled maltose for 10 min. In a second set of bacterial samples, we co-incubated the 14C-labeled maltose with 1 mM maltose which completely blocked the uptake of the radiolabeled maltose. In a third set of samples, we co-incubated the 14C-labeled maltose with 1-fluoromaltose which also completely blocked the uptake of the 14C-labeled maltose similar to the natural maltose.

Figure 4.

Uptake of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose in vitro in Escherichia coli and a mammalian cell line EL4 at the indicated times.

Figure 5.

Maltose and 1-fluoromaltose effectively compete with [14C]maltose uptake by Escherichia coli.

Discussion

It has been reported that after intravenous injection of maltose in a human subject, maltose is slowly degraded in the lung with a limited urinary excretion [22]. The pharmacokinetics of a maltose-base PET tracer should be compatible with the clinical development. Therefore, 18F-labelled maltose derivatives could be ideal PET tracers for imaging bacterial infections. It is difficult to predict which anomer of 1-substituted maltose has high affinity for bacteria. It is well known that the methyl alpha maltoside has higher affinity for bacteria than maltose [23]. In cells, glucose transporters (GLUTs) could be an issue by taking up 1-F-Gluc or 6-F-Gluc from in vivo metabolism of fluoromaltose and therefore increasing the background signal. The OH group at C6 seems to not make a hydrogen bond with GLUT1, and bulky substitutions at this position are tolerated. However, bulky substitutions at C1 are not tolerated [24]. So it makes sense to try first the 1-F-maltose to avoid a cellular uptake of 1-F-Gluc in case of in vivo metabolism. Unfortunately, this compound is not stable in vivo. The maltodextrin transporter in bacteria is more flexible and seems to be not very sensitive to substitution (9).

Majority of fluorinated sugars are synthesized via DAST reagent. Due to difficult synthesis and long reaction time of [18F]DAST, it is not practical to use for the preparation of 18F-labelled sugar. We have developed a way to synthesize 4-O-(α-D-glucopyranosyl)-6-deoxy-6-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucopyranoside (6-[18F]fluoromaltose, 7) as a novel bacterial infection PET imaging agent. 6-[18F]fluoromaltose was prepared from precursor 1,2,3-tri-O-acetyl-4-O-(2′,3′,-di-O-acetyl-4′,6′-benzylidene-α-D-glucopyranosyl)-6-deoxy-6-nosyl-D-glucopranoside (5). Scheme 1 describes the synthesis of 5. Compound 5 was characterized by high-resolution mass spectrometry and NMR. High-resolution MS showed a mass peak of 848.1694 (M + Na). The NMR spectrum showed new sets of doublet peaks in the aromatic region with an integration of 2H each. Similar NMR patterns were observed in the synthesis of 3-hydroxy-3-phenylpropyl 4-nitrobenzenesulfonate [20]. To the best of our knowledge, for the first time, we have synthesized 6-[18F]fluoromaltose (7, Scheme 2) via a direct fluorination of 5 with anhydrous [18F]KF/Kryptofix 2.2.2 in 5–8 % radiochemical yield (decay-corrected). This radiochemical yield is based on our optimization yield obtained in DMF, DMSO, and acetonitrile as a solvent at temperature range of 70–120 °C. We found that with 6-nosyl-maltose precursor and acetonitrile or DMF as a solvent at 80 °C, we can obtain 6-[18F]fluoromaltose in 5–8 % radiochemical yield. Similarly, 1-[18F]fluoromaltose (11, Scheme 3) was prepared by nucleophilic displacement of triflate group in precursor 9 by [18F]fluoride ion in 4–6 % radiochemical yield (unoptimized, decay-corrected). However, only the α-anomer was stable under purification conditions. In fact, it has been reported that only the α-anomer of cold 1-fluoromaltose is stable in the room temperature [12].

6-[18F]Fluoromaltose was sufficiently stable over the time necessary for PET studies (~96 % intact compound after 1-h and ~65 % after 2-h incubation in serum, Fig. 3). The instability at the longer time could be due to slow defluorination of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose at 2 h.

Figure 4 shows the uptake of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose by E. coli and a mammalian cell line (EL4) and confirms that the uptake of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose in bacteria is time dependent. However, for EL4, the uptake was minimal after 60-min post-incubation with tracer. The uptake in E. coli could also be blocked by co-incubation with 1 mM of cold maltose (98 % blocking, p<0.0003), the natural substrate of the transporter. The rapid uptake is necessary if 6-[18F]fluoromaltose with an isotope half-life of 110 min is eventually going to prove efficacious as a PET tracer. The uptake studies were done in Hank’s buffered saturated solution (HBSS) which has physiological levels of glucose (5 mM). So we are accounting for the presence of glucose in our tracer uptake studies. In vivo, the tracer will compete with glucose (mice could have been fasted before in vivo imaging to limit glycemia variation), but glucose will probably not saturate the maltodextrin transporter in bacteria. More biological data including in vivo studies of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose have been reported by us [25]. Also, we tested 1-fluoromaltose in a competition assay as shown in Fig. 5. This suggested that 1-fluoromaltose was recognized and transported by the bacteria in a manner identical to maltose itself. However, we found that α-anomer of 1-[18F]fluoromaltose is not stable in vivo and de-fluorinated rapidly which resulted in high uptake of [18F]fluoride ion by the bones (data not shown).

Conclusion

We have successfully synthesized both 6- and 1-[18F]fluoromaltose via a direct fluorination of an appropriate protected maltose precursor. Preliminary bacteria uptake experiments done in E. coli bacteria suggest possible applicability of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose as a new PET imaging agent for detection and monitoring of disease of bacterial infection origin. In the future, we will further examine tracer uptake and metabolism in bacteria and determine the efficacy of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose in imaging bacterial infection for various mouse models. These data should lay a foundation for the use of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose as an imaging agent in human bacterial infection disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by NCI In vivo Cellular Molecular Imaging Center (ICMIC) grant P50 CA114747 (SSG). We also thank the cyclotron facility at Stanford for [18F]fluoride production and modification of a GE TRACERlab FX-FN synthetic module for radiosynthesis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Palestro CJ. Radionuclides imaging of infection: in search of the grail. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:671–673. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.058297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corstens FHM, van der Meer JWM. Nuclear medicine’s role in infection and inflammation. Lancet. 1999;354:765–7670. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar S, Basu S, Torigian D, et al. Role of modern imaging techniques for diagnoses of infection in the area of 18F-fluordeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:209–224. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00025-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langer O, Mitterhauser M, Brunner M, Zeitlinger M, Wadsak W, Mayer BX, Kletter K, Muller M. Synthesis of [18F]ciprofloxacin for PET studies in humans. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:285–291. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00444-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langer O, Brunner M, Zeitlinger M, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of [18F]ciprofloxacin for the imaging infection with PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:143–150. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1646-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasser TA, Van AVermaete AE, White A, et al. Bacterial Infection Probes and Imaging Strategies in Clinical Nuclear Medicine and Preclinical Molecular Imaging. Current Topic. Med Chem. 2013;13:479–487. doi: 10.2174/1568026611313040008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petruzz IN, Shanthly N, Thakur M. Recent trend in soft tissue infection imaging. Semin Nucl Med. 2009;39:115–123. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diaz LA, Foss CA, Thornton K, et al. Imaging of musculoskeletal bacterial infection by [124I]FIAU-PET/CT. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ning X, Lee S, Wang Z, et al. Maltodextrine-based imaging probes detect bacteria in vivo with high sensitivity and specificity. Nat Mater. 2011;10:602–607. doi: 10.1038/nmat3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahl MK, Manson MD. interspecific reconstitution of maltose transport and chemotaxis in Escherichia coli with maltose binding protein from various enteric bacteria. J Bactriol. 1985;164:1037–1063. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.3.1057-1063.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gopal S, Berg D, Hagen N, et al. Maltose and maltodextrine utilization by listeria monocytogenes depend on an inducible ABC transporter which is repressed by glucose. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braitsch M, Kahlig H, Kontaxis G, et al. Synthesis of fluorinated maltose derivatives for monitoring protein interaction by 19 F NMR. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2012;8:448–455. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.8.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Excoffier G, Gagnaire D, Utille J-P. Coupure selective par 1 hydrozine des groupments acetyles anomeres de residus glycosyles acetyls. Carbohydr Res. 1975;39:368–373. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toshima K. Glycosyl fluorides in glycosidations. Carbohydr Res. 2000;327:15–26. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(99)00325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lal GS, Pez GP, Pasaresi RJ, et al. Bis (2-methyl) aminosulfur trifluoride: a new broad spectrum deoxofluorinating agent with enhanced thermal stability. J Org Chem. 1999;64:7048–7054. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeo K, Shinmitsu K. A convenient synthesis of 6′-C-substituted b-maltose heptaacetates and of panose. Carbohydr Res. 1984;133:135–145. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye S, Rezende MM, Deng W-P, Herbert B, Daly JW, Johnson RA, Kirk KL. Synthesis of 2′, 5′-dideoxy-2-fluoroadenosine and 2′, 5′-dideoxy-2′,5′-difluoroadenosine: potent P-site inhibitors of adenylyl cyclase. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1207–1213. doi: 10.1021/jm0303599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Best WM, Stick RV, Tilbrook DMG. The synthesis of some epoxyalkyl-deoxyhalo-β-cellobiosides. Aust J Chem. 1997;50:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dutton GGS, Slessor KN. Synthesis of 6′-Substituted Maltose. Cana J Chem. 1966;44:1069. [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Castro KA, Rhee H. Selective nosylation of 1-phenylpropane-1,3-diol and perchloric acid mediated Friedel-Crafts alkylation: key steps for the new and straightforward synthesis of Toletero dine. Synthesis No. 12 P. 2008:1841–1844. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tyokuni T, Kumar JSD, Gunawan P, et al. Practical and reliable synthesis of 1, 3, 4, 6-tetra-O-acetyl-2-O-trifluoromethanesulffonyl-β-D-mannopyranosyl, a precursor of 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose. Mol Imaging Biol. 2004;6:417. doi: 10.1016/j.mibio.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young SJM, Weser E. The metabolism of circulating maltose in man. J Clin Inves. 1971;50:986–9891. doi: 10.1172/JCI106592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferenci T. Methyl-α-maltoside and 5-thiomatose: analogs transported by escherichia coli maltose transported system. J Bacteriol. 1980;144:7–11. doi: 10.1128/jb.144.1.7-11.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carruthers A, DeZutter J, Ganguly A, Devaskar SU. Will the original glucose transporter isoform please stand up! Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E836–E848. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00496.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gowrishankar, et al. Investigation of 6-[18F]fluoromaltose as a novel PET tracer for imaging bacterial infection. PLos One. 2014 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107951. (accepted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]