Abstract

In myelinated axons, action potential conduction is dependent on the discrete clustering of ion channels at specialized regions of the axon, termed nodes of Ranvier. This organization is controlled, at least in part, by the adherence of myelin sheaths to the axolemma in the adjacent region of the paranode. Age-related disruption in the integrity of internodal myelin sheaths is well-described and includes splitting of myelin sheaths, redundant myelin, and fluctuations in biochemical constituents of myelin. These changes have been proposed to contribute to age-related cognitive decline since in previous studies of monkeys, myelin changes correlate with cognitive performance. In the present study, we hypothesize that age-dependent myelin breakdown results in concomitant disruption at sites of axoglial contact, in particular at the paranode and that this disruption alters the molecular organization in this region. In aged monkey and rat optic nerves, immunolabeling for voltage-dependent potassium channels of the Shaker family (Kv1.2), normally localizing in the adjacent juxtaparanode, were mislocalized to the paranode. Similarly, immunolabeling for the paranodal marker, caspr, reveals irregular caspr-labeled paranodal profiles, suggesting there may be age-related changes in paranodal structure. Ultrastructural analysis of paranodal segments from optic nerve of aged monkeys shows that in a subset of myelinated axons with thick sheaths, some paranodal loops fail to contact the axolemma. Thus, age-dependent myelin alterations affect axonal protein localization and may be detrimental to maintenance of axonal conduction.

Keywords: aging, monkey, paranode, juxtaparanode, caspr, channels

Introduction

Regular interruptions in myelin at specialized regions of the axolemma, termed nodes of Ranvier, facilitate saltatory conduction. Clustered nodal voltage-gated sodium (NaV) channels are integral to this process. Two distinct axonal regions flank the node: the paranode where myelin loops make contact with the axon, and the juxtaparanode, the axonal region adjacent to the paranode wrapped by the compact myelin sheath. The node, paranode, and juxtaparanode are easily distinguished, each having a unique structural and molecular composition (Kazarinova-Noyes and Shrager, 2002). Various inherited or demyelinating neuropathies lead to changes in the molecular organization of the nodal axolemma, suggesting that myelin sheath integrity is necessary for maintenance of nodal structure.

Paranodes are particularly important to preserve molecular segregation of nodal proteins, presumably via the interaction of the axon and myelin membranes resulting in the formation of a septate-like junction. This interface is thought to consist of a tripartite adhesion complex, including contactin, contactin-associated protein (caspr), and neurofascin-155 (NF155), though the exact nature of the interaction remains unclear (Gollan et al., 2003; Marcus and Popko, 2002; Poliak et al., 2001). Mice deficient in the paranodal proteins contactin or caspr do not develop the normal septate-like junctions characteristic of paranodes and have mislocalized juxtaparanodal proteins (e.g., voltage-gated potassium channels (Kv), Kv1.1, Kv1.2, Kvß2, and caspr2) (Boyle et al., 2001; Rios et al., 2003). These mice exhibit tremor, ataxia, and motor paresis in association with decreased peripheral nerve conduction velocity (Bhat et al., 2001). Furthermore, cgt- and cst-null mice, deficient in galactolipid production, demonstrate similar paranodal abnormalities (Dupree et al., 1998; Ishibashi et al., 2002). In Plpjimpy mice, Plpmyelin-deficient rats, and Mbpshiverer mice, all with varying degrees of CNS demyelination with or without oligodendrogliopathy, there is disruption or absence of paranodal structure and Kv1.1/Kv1.2 localize immediately adjacent to NaV clusters (Arroyo et al., 2002; Ishibashi et al., 2003; Rasband et al., 1999).

Likewise, acquired demyelination shows similar mislocalization of axonal proteins. Experimental demyelination of rats results in disruption of juxtaparanodal Kv1.2 clusters (Rasband et al., 1998). Kv channels and caspr disperse along injured axons following spinal cord injury (Karimi-Abdolrezaee et al., 2004), multiple sclerosis (Wolswijk and Balesar, 2003) and EAE (Craner et al., 2003). Myelin also alters axonal protein expression and localization during development evidenced by the myelination-dependent switch of NaV isoforms (from NaV1.2 to NaV1.6) present at the node in retinal ganglion cells (Boiko et al., 2001). Thus, the presence or absence of myelin induces molecular reorganization of nodal domains.

Changes in myelin structure and composition have been noted throughout aging rat (Knox et al., 1989; Sugiyama et al., 2002), monkey (Peters, 2002; Sloane et al., 2003), and human (Albert, 1993) brains and these changes are hypothesized to mediate age-related cognitive decline. The changes include, but are not limited to, splitting of myelin along the major dense line or along the intraperiod line, the formation of redundant myelin sheaths, and fluctuations in myelin content, proteins, and protease activity (Hinman et al., 2004; Sloane et al., 2003; Sugiyama et al., 2002). In 31 month old rats, Sugiyama et al (2002) report age-dependent alterations in paranodal structure illustrating paranodal loops that fail to reach the axon. In addition, with age, an increase in paranodal profiles and the presence of short, thin internodal lengths of myelin in area 17 and 46 of the rhesus monkey have been reported, suggesting the aged CNS may attempt to remyelinate itself (Peters and Sethares, 2003).

Based on results supporting age-related changes in myelin, coupled with alterations in nodal proteins following acute or genetic demyelination, we hypothesized that age-related changes in nodal protein expression levels or localization induced by myelin pathology may contribute to cognitive decline. Aside from modest axonal loss, there is no current description of axonal changes that can functionally account for the observed reduction in cognitive ability. In this study, we determined the effects of age on NaV channel, caspr, and Kv1.2 channel localization and expression at nodes of Ranvier and the adjacent paranodal and juxtaparanodal regions. In this report, we used the aged rat and monkey optic nerves as models for age-related changes in myelin (Sandell and Peters, 2001) to assess age-related alterations in these critical axonal proteins. In the optic nerve, aging results in mislocalization of Kv1.2 in paranodes and disorganization of paranodal proteins (e.g. caspr), in the presence of ultrastructurally abnormal paranodes with extra paranodal loops. Together these changes may underlie the axonal conduction failure presumed to account for age-related cognitive decline.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All chemicals and reagents were purchased from either Sigma Co. or American Bioanalytical, unless otherwise noted. All antibodies used to label axonal regions including and surrounding the node of Ranvier have been previously described in detail and citations provided. Appropriate controls performed in the absence of primary antibody were performed to judge the ability of the antibodies to label nodal, paranodal, and juxtaparanodal regions (Supplemental Figure 1). Antibodies used to identify the region of the node include monoclonal anti-pan-NaV (1:500 IF) generated against a conserved sequence present in all vertebrate NaV1 isoforms (TEEQKKYYNAMKKLGSKK) and recognizing several bands >250 kDa m.w. corresponding to the various NaV isoforms expressed in brain (Rasband et al., 1999). These antibodies robustly label nodes of Ranvier and axon initial segments, regions highly enriched in voltage-gated Na+ channels. Monoclonal anti-NaV1.2 (1:500 IF) and polyclonal anti-NaV1.2 (1:200 IF) were generated against a unique peptide sequence (CYKKDKGKEDEGTPIKE) in the NaV1.2 C-terminus and recognize a single band of ~250 kDa m.w. (Gong et al., 1999). During early developmental myelination these antibodies have been shown to label nodes of Ranvier (Boiko et al., 2001). Monoclonal anti-NaV1.6 (1:600 IF) and polyclonal anti-NaV1.6 (1:500 IF) were generated against a unique peptide sequence (CSEDAIEEEGEDGVGSPRS) located in the large intracellular domain I-II loop of NaV1.6 and recognizing a single band of ~250 kDa m.w. These antibodies robustly label mature nodes of Ranvier and axon initial segments. Antibodies used to identify the region of the paranode include polyclonal anti-caspr (1:2000 IB) (Rasband et al., 2003), monoclonal anti-caspr IgG (1:400 IF) (Rasband and Trimmer, 2001), monoclonal anti-caspr IgM (neat IF) (Schafer et al., 2004), all generated against a GST fusion protein containing the entire cytoplasmic domain of caspr (Peles et al., 1997). Polyclonal anti-Kv1.2 (1:500 IF, 1:2000 IB) was generated against a synthetic peptide (CGVNNSNEDFREENLKTAN) corresponding to amino acids 463–480 of the Kv1.2 polypeptide. This antibody recognizes a prominent band of 98 kDa m.w. and robustly labels the juxtaparanodal region of myelinated nerve fibers (Rasband and Trimmer, 2001; Rhodes et al., 1995). Monoclonal anti-CNPase, raised against purified human brain CNPase and recognizing both the 48 kDa and 46 kDa m.w. forms of CNPase (Chemicon MAB326, 1:2000) was used as a loading control for total myelin protein. We thank Dr. James Trimmer for his generosity in providing antibodies.

Subjects

Twenty-two rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were acquired from the colony of the Yerkes National Primate Research Center. These monkeys were selected according to strict critera which excluded monkeys with health, enviromental or experimental histories that could affect the brain or behavior. As summarized in Table 1, the birth dates were known for all monkeys. Young monkeys are defined as between the ages of 4 and 10 years of age; old monkeys defined as greater than 19 years of age. After entry into the program, all monkeys were behaviorally tested on a battery of tasks assessing learning, memory and executive function as described below at both the Yerkes National Primate Research Center and subsequently at the Laboratory Animal Science Center at Boston University School of Medicine. Both facilities are fully accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) of both institutions and complied with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources Commission on Life Sciences’ Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Table 1.

Monkey Subjects Used in Study

| AM ID | Age (yrs) | Tissue Used |

|---|---|---|

| 121 | 30.29 | Optic nerve |

| 149 | 19.84 | Optic nerve |

| 159 | 19.81 | Optic nerve |

| 161 | 19.19 | Optic nerve |

| 162 | 22.36 | Optic nerve |

| 177 | 20.97 | Optic nerve |

| 179 | 23.67 | Optic nerve |

| 180 | 29.61 | Optic nerve |

| 128 | 7.93 | Optic nerve |

| 188 | 6.54 | Optic nerve |

| 53# | 9.53 | Optic nerve |

| 65# | 32.48 | Optic nerve |

| 91# | 31.08 | Optic nerve |

| 41# | 31.50 | Optic nerve |

| 160* | 20.68 | Optic nerve/Corpus callosum |

| 127* | 7.38 | Optic nerve/Corpus callosum |

| 148* | 7.35 | Optic nerve/Corpus callosum |

| 163* | 10.17 | Optic nerve/Corpus callosum |

| 164* | 24.56 | Optic nerve/Corpus callosum |

| 165* | 22.63 | Optic nerve/Corpus callosum |

| 131* | 6.68 | Optic nerve/Corpus callosum |

| 126* | 21.0 | Optic nerve/Corpus callosum |

- indicates animal was perfused with Krebs buffer and tissue used for immunoblot studies.

- indicates animal was perfused with 1.25% glutaraldehyde/1.0% paraformaldehyde and tissue used for electron microscopy. All other animals were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde and tissue used for light microscopy.

At the conclusion of testing, all monkeys were deeply anaesthetized and then perfused through the heart with 4 liters of perfusate to ensure optimal preservation of the brain. Three types of perfusate were used: (1) Krebs-Heinseleit buffer, pH 7.4 (6.41 mM Na2HPO4, 1.67 mM NaH2CO3, 137 mM NaCl, 2.68 mM KCl, 5.55 mM Glucose, 0.34 mM CaCl2, 2.14 mM MgCl2), (2) 4% paraformaldehyde in 100 mM Na2HPO4 buffer, pH 7.4, or (3) 1% paraformaldehyde and 1.25% glutaraldehyde in 100 mM Na2HPO4 buffer, pH 7.4 (see Table 1).

Tissue processing

For monkeys perfused with Krebs buffer, the brain was quickly removed, weighed, dissected, and then flash-frozen in −70°C isopentane and after which tissue was stored at −80°C (Rosene and Rhodes, 1990) until used for membrane preparation. For animals perfused with 4% PF, the optic nerves were removed supraorbitally and cryoprotected stepwise in 20% and 30% sucrose and stored at −20°C until sectioning for light microscopy. Optic nerves from animals perfused with paraformaldehyde/glutaraldehyde were removed and fixed further by immersion in cold 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 100 mM Na2HPO4 buffer, pH 7.4, and cut into 2 mm segments. The segments were then osmicated, dehydrated in ethanol, and embedded in Araldite. Longitudinally oriented thin sections were taken for electron microscopy, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined in a JEOL100 microscope.

The brains and optic nerves of Fischer 344 rats of varying ages were acquired from the NIA Aging Rodent Colonies (more information on animal maintenance and tissue processing available at http://www.nia.nih.gov/research/tissuebank.htm). Brains were dissected into left and right hemispheres, flash frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until use. Optic nerves were dissected and fixed for 30 min in ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in 100 mM Na2HPO4 buffer, pH 7.4 and cryoprotected stepwise in 20% and 30% sucrose and stored at –20°C until sectioning.

Cognitive assessment of monkeys

Monkeys were tested on a battery of different tasks. These included first acquisition of the delayed non-match to sample task (DNMS-Acq), a test of rule learning. This was followed by tests of DNMS with longer delay intervals to assess recognition memory. Monkeys were then tested on the delayed recognition span task (DRST) which is given in both spatial and object modes and assesses working memory capacity. This was followed by a test of simple attention and then acquisition of a three choice discrimination task to assess associative learning. Finally, monkeys were tested on the cognitive set shifting task, an analog of the Wisconsin Card Sort Test which assesses executive function. The details of these tests are further described in Herndon et al. (1997) and Moore et al. (2003). From the DNMS and DRST tasks, a composite score for generalized cognitive ability, designated the Cognitive Impairment Index (CII), was derived based on principal components analysis of the scores of these tests (Herndon et al., 1997). This analysis indicated that the overall level of impairment was best predicted by a weighted average of each subject's standardized score on each of three tests (DNMS acquisition; DNMS, at a 2 minute delay and the spatial condition of the DRST, spatial). Raw scores were standardized (converted to z scores) on each task using a reference group of 40 young adults (5–10 years of age). The CII was then computed as a simple average of the three standardized scores adjusted so that positive numbers indicate increasing levels of impairment relative to the reference group of young adults.

Membrane preparation and immunoblotting

This was performed as described previously (Rasband and Trimmer, 2001). In brief, left hemispheres of rat brains and dissected monkey brain areas were weighed and homogenized on ice in 1 ml/100 mg tissue of 320 mM sucrose in 5 mM Na2HPO4 buffer, pH 7.4 with 2 µg/ml aprotinin, 1 µg/ml leupeptin, 10 µg/ml benzamidine and 0.5 mM PMSF, using ten strokes of a drill homogenizer. Homogenates were spun at 489 × g (2500 rpm in SS-34 rotor) for 10 min at 4°C. Brain membranes were collected by centrifugation at 25000 × g (18,000 rpm in SS-34 rotor) for 90 min at 4°C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in a small volume of buffer and stored at –80°C until use. Protein concentrations were determined by BCA analysis (Pierce). Samples representing 30–50 µg total protein were diluted in sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970), analyzed by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore). Blots were blocked for 1 hr in 5% nonfat milk prepared in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST) at room temperature (RT). Primary antibody dilutions were prepared in milk as indicated in Materials. Depending on primary antibody type, antibody/antigen complexes were identified by peroxidase-linked goat anti-mouse IgG or goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000; KPL) and visualized using the ECL system (Amersham Biosciences).

Immunofluorescence

Monkey and rat optic nerve tissue was sectioned on a Hacker/Brights cryostat at 6 µm, and thaw-mounted on 1% gelatin coated slides, rapidly dried and stored at –80°C until immunostaining. Non-specific staining was blocked by incubation in 10% normal goat serum in 100 mM Na2HPO4 buffer, pH 7.4 with 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBTGS). All antibody preparations were diluted in PBTGS as indicated in Materials and all incubations were performed at room temperature. Appropriate AlexaFluor (Molecular Probes) secondary antibodies were selected according to immunoglobulin isotype.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

In order to quantify mislocalized paranodal Kv1.2, we used NaV/Kv1.2 double-stained sections, stained simultaneously to control for batch variability, and the region representing the paranode, marked by the abrupt decrease in Kv1.2 labeling and the clear labeling of nodal NaV, was outlined using OpenLab v3.1.2 software. Roughly one-hundred paranodes were selected for quantification per animal, with the only criterion for selection being that the paranodal segment was entirely within the plane of section being imaged. Using a constant 400 msec camera exposure time, the pixel intensity of Kv1.2 staining in each outlined paranodal segment was measured. A ratio of Kv1.2 pixel intensity per unit area was generated for each measured paranodal segment and plotted as a function of age. In all cases, repeated paranodal measurements were taken from multiple sections from both left and right optic nerves from each animal in the study. Statistical significance was determined using a student’s t-test with p<0.05.

Digital Image Production

Microscopic images were acquired using a digital CCD camera affixed to a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope powered by OpenLab v3.1.2 software. Single channel fluorescent images were exported into Adobe® Photoshop v6.0 software where image histogram adjustments were made equally to reduce contribution of background fluorescence. Images were cropped, calibrated, and re-sized for presentation.

Results

Nodal NaV isoforms do not change with age

Previous reports have indicated that upon myelination, optic nerve axons switch from expressing NaV1.2 at nodes to NaV1.6 (Boiko et al., 2001) and there is evidence that in the CNS intact paranodes are required for NaV1.6 retention at mature nodes (Rios et al., 2003; Suzuki et al., 2004). Initially, we hypothesized that age-related changes in myelin might affect the NaV isoform expressed in axons, inducing a reversal back to NaV1.2 localization at nodes in at least a subset of axons. However, all identifiable nodes in optic nerve sections from both young (4 months old) and old (28 months old) Fischer 344 rats were negative for NaV1.2 staining, labeled using monoclonal antibodies directed against NaV1.2 (Figure 1A and 1C, arrows), though were labeled clearly with NaV1.6 (Figure 1B and 1D, arrows). NaV1.2 staining was obtained in the axonal initial segment of a hippocampal neuron (Figure 1E). Furthermore, few abnormalities in nodal structure, such as wide nodes or binary nodes, were noted in aged rats or monkeys. Age-related changes in myelin appear to have minimal effects on the expression or organization of NaV channels at nodes of Ranvier.

Figure 1.

Nodal NaV isoforms do not change with age. Labeling for NaV1.2 and NaV1.6 expression at nodes was examined in 6 µm sections of 4 month old (A and B) and 28 month old (C and D) rat optic nerve using monoclonal anti-NaV1.2 antibodies and polyclonal NaV1.6 antibodies. NaV1.2 expression is absent in both age groups (arrows, A and C) though NaV1.6 expression is abundant at nodes in young and old rats (arrows, B and D). NaV1.2 staining was obtained in the axon initial segment of a rat hippocampal neuron (E). Scale bars in A–D = 2 µm; E = 10 µm.

Kv1.2 increases in paranodal regions with age

Sections of monkey optic nerve immunostained for nodal NaV and juxtaparanodal Kv1.2 revealed an age-related increase in the number of axons with Kv1.2 abnormally localized to the paranodal region (Figure 2A–F, arrows point to paranodes). While the presence of Kv1.2 in paranodal regions was highly variable, it was most notable in larger caliber axons. Immunostaining of monkey optic nerve sections with paranodal caspr and Kv1.2 confirmed localization of Kv1.2 to the paranode in animals of increasing age (Figure 2G–I, arrows). Within individual paranodes, in many instances it appeared that Kv1.2 was detected in regions with minimal caspr staining, supporting the idea that the localization of the two molecules is mutually exclusive.

Figure 2.

Paranodal Kv1.2 staining increases with age. NaV (red) and Kv1.2 (green) expression were analyzed in 6 µm sections of monkey optic nerve in 7.9 yo (A), 19.8 yo (B) and 30.3 yo (C) animals. Kv1.2 localization in paranodal regions was absent in young paranodes (D, arrow), while easily detected in paranodes from older animals (E, F, arrow). Double staining with caspr (red) and Kv1.2 (green) confirmed the paranodal localization of Kv1.2 in older animals compared to young (G–I, arrow). Scale bar = 10 µm in A–C; 2 µm in D–I.

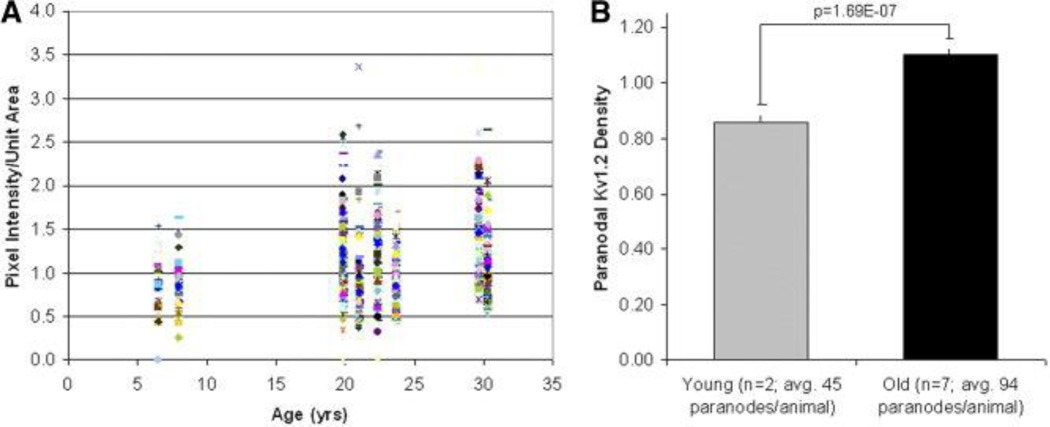

To quantify the changes in localization of Kv1.2 we measured pixel intensity within selected paranodal regions in monkey optic nerve as a function of age and in relationship to cognitive impairment. Ratios of pixel intensity/unit area (paranodal density of Kv1.2) were measured and plotted as a function of age (Figure 3A). Cumulative averages of pixel intensity/unit area from young subjects versus old are presented in Figure 3B and were significantly different as indicated. On the assumption that the optic nerve provides a model for changes throughout the forebrain, we attempted to correlate the age-related increase in paranodal Kv1.2 density with results from behavioral testing of monkeys. These results were suggestive but did not produce any statistically significant results.

Figure 3.

Quantification of age-related increase in paranodal Kv1.2. Kv1.2 pixel intensity/unit area in paranodal regions is plotted as a function of age (A). Paranodal regions with elevated Kv1.2 density increase with age. Grouped analysis of the average paranodal density of Kv1.2 demonstrates a statistically significant difference with age (B).

Caspr staining reveals altered paranodal appearance with age

In addition to confirming the age-related paranodal localization of Kv1.2, double immunostaining of monkey optic nerve sections with caspr (red) and Kv1.2 (green), revealed abnormalities in paranodal structure (Figure 4). The characteristic compartmentalization of paranodal caspr and juxtaparanodal Kv1.2 as seen in young animals (Figure 4A) was frequently disrupted in aged animals resulting in the irregular appearing paranodes pictured (arrows, Figure 4B–D). Individual labels for caspr and Kv1.2 highlight the normal paranodal organization in seen in young monkeys (Figure 4E–F) and the disrupted compartmentalization in the paranodal region encountered with age (Figure 4G–H). These paranodes had a highly variable size and shape compared to that of the young, often appearing longer and extending much further along the axolemma than should be expected. This staining appeared different than the spiral of caspr staining which can be visualized in confocal images of intact paranodes in the sciatic nerve (Arroyo et al., 2001). The significance of these abnormalities in paranodal regions is not known but may reflect a breakdown of the normal paranodal axoglial junction.

Figure 4.

Caspr staining reveals altered paranodal structure with age. Paranodal structure was examined in 6 µm sections of monkey optic nerve in young (A) and old (B–D) animals by staining for Kv1.2 (green) and caspr (red). Paranodes in young animals have the characteristic compartmentalization of paranodal caspr (E) and juxtaparanodal Kv1.2 (F). In older animals, paranodes with irregular separation of caspr (G) and Kv1.2 (H) appear more frequently (arrows in B–D). Scale bar = 1 µm.

Changes in node of Ranvier organization in aging rats

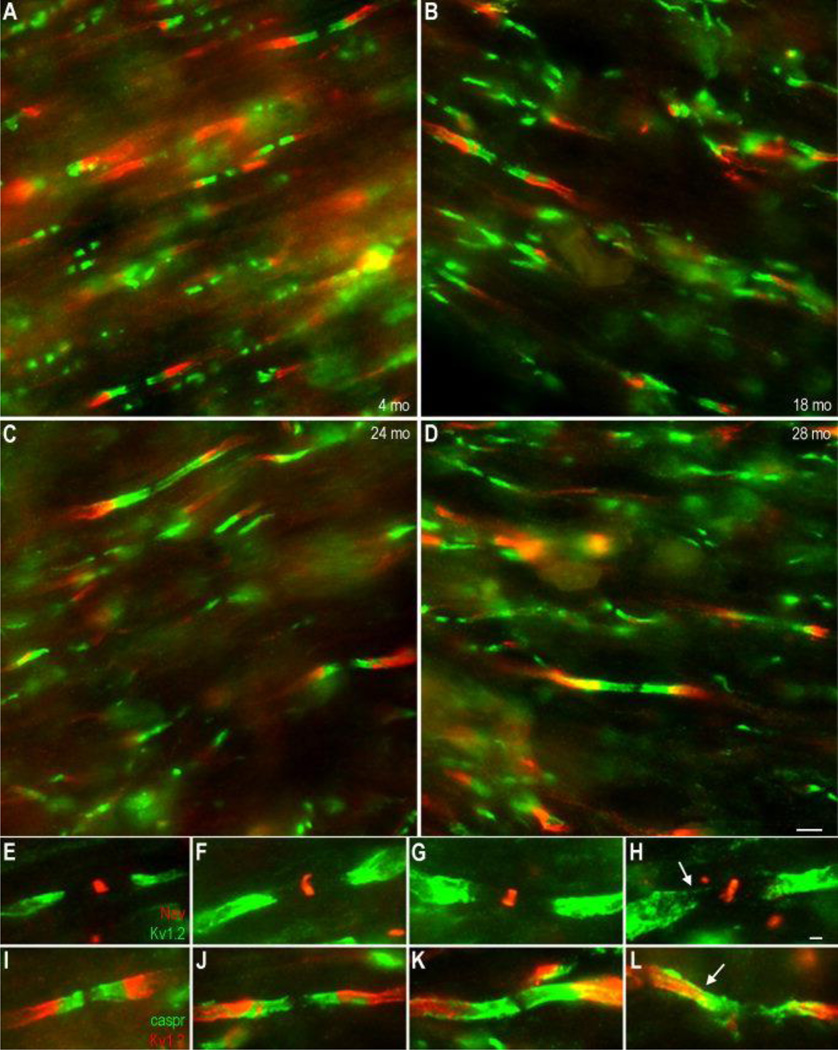

To confirm observations of age-related molecular reorganization noted in the monkey, similar studies were carried out using Fischer 344 rats of varying ages (4, 18, 24, and 28 months). In these animals, paranodes showed increasing axonal disorganization with age in the same fashion observed in the monkey, indicated here by caspr (green) and Kv1.2 (red) double staining (Figure 5A–D). Double immunofluorescence for Kv1.2 (green) and NaV (red) revealed an age-dependent increase in the paranodal localization of Kv1.2, which became apparent in 24 and 28 month old animals, while being only occasionally present at 18 months (Figure 5E–H, arrow). Double immunofluorescence for caspr (green) and Kv1.2 (red) demonstrated age-related abnormalities in the maintenance of the paranodal-juxtaparanodal junction (Figure 5I–L, arrow). In some instances, caspr and Kv1.2 signals were seen to co-localize, and in virtually all large caliber axons in aged rats, the usually distinct separation of caspr-positive paranodes and Kv1.2-positive juxtaparanodes, seen in young rats (Figure 5I), was absent. Unlike the presence of paranodal Kv1.2, these abnormalities in caspr staining were present in rats beginning at 18 months and included the majority of paranodes by 28 months.

Figure 5.

Paranodal Kv1.2 and irregular paranodes increase in Fischer 344 rats of increasing age. Paranodal integrity was examined in 6 µm sections of optic nerve from 4 month (A, E, and I), 18 month (B, F, and J), 24 month (C, G, and K), and 28 month old rats (D, H, and L) by double immunofluorescence for either caspr (green) and Kv1.2 (red) (A–D; I–L) or NaV (red) and Kv1.2 (green) (E–H). With age, Kv1.2 became detectable in the paranodal region (E–H) while caspr paranodal profiles appeared increasingly irregular (arrows, I–L). Scale bar = 2 µm in A–D; 1 µm in E–L.

Kv1.2 expression levels remain constant with age

Immunoblot analyses of membrane fractions of axon-rich monkey tissues, including the optic nerve and corpus callosum indicate Kv1.2 levels do not change with age (Figure 6A–B, upper panels). This suggests that the increased detection of Kv1.2 in paranodal regions with age is a change in protein localization, not increased expression. Thus, paranodal Kv1.2 most likely occurs focally in individual axonal regions most affected by myelin damage. This result is consistent with observations in knockout mice (caspr2, caspr, contactin, etc.) demonstrating increased paranodal Kv1.2 in the presence of myelin abnormalities.

Figure 6.

Kv1.2 protein levels do not change with age. Immunoblot analysis of membrane fractions isolated from monkey optic nerve (A), corpus callosum (B) and rat brain hemispheres (C) for Kv1.2 (upper panels) and caspr (middle panels) demonstrated no change in cumulative levels of nodal proteins with age. SDS-insoluble caspr-immunoreactive aggregates (arrowheads in A, C) did show some variation with age, particularly increasing in aged rat brain. Kv1.2 aggregates can also be detected. CNP (lower panels) levels were included as a loading control for myelin protein.

In the monkey optic nerve and corpus callosum, there also appeared to be no change in caspr levels with age (Figure 6A–B, middle panels). However, there was an appreciable level of variability from animal to animal in caspr levels particularly in optic nerve samples, presumably a result of the variable number of paranodes present in each sample. This may also be an indication of age-related axon loss, which has been documented in the optic nerve though not in the corpus callosum (Peters and Sethares, 2002; Sandell and Peters, 2001). In addition to caspr, a high molecular weight band (~ 300–400 kDa) was detected using the caspr polyclonal antibody and was most consistently detected in samples from aged animals (arrowhead). This high molecular weight band immunoreactive for caspr most likely represents SDS-stable aggregates of contactin and caspr (unpublished data). The significance of the increase in this band with age is unclear. Immunoblots for the myelin protein CNPase, served as loading controls for total protein in this preparation (Figure 6, lower panels).

Comparative analysis of membrane fractions isolated from entire rat brain hemispheres also demonstrated that Kv1.2 levels do not change with age (Figure 6C, upper panel). Immunoblots for caspr (Figure 6C, middle panel), however, indicated a subtle age-dependent increase in this molecule as well as the detection and age-related increase in a high molecular weight band similar to that observed in the monkey (arrowhead). Increases in caspr were not observed in monkey tissues, however, this result in the rat is reflective of changes occurring in the entire CNS rather than in specific sites such as the optic nerve and corpus callosum and may be indicative of an overall increase in paranodes resulting from attempts at remyelination or result from caspr expression besides that in the axon.

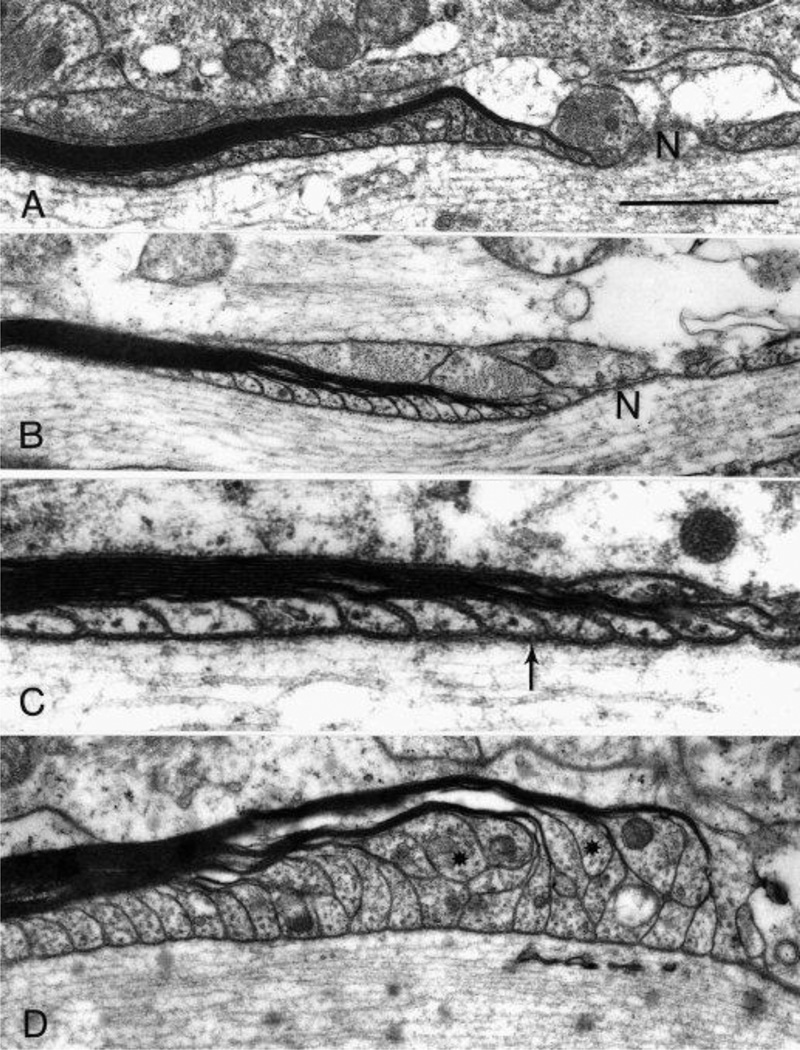

Variations in paranodal ultrastructure with age

Longitudinal sections of monkey optic nerve tissue examined with the electron microscope reveal two different populations of paranodes. Sections from young animals all show the normal arrangement of paranodal loops of the myelin sheath, in which all of the paranodal loops come into contact with the axon (Figure 7A). In aged animals, most of the paranodes also appear normal (Figure 7B) and have identifiable transverse bands (arrow, Figure 7C). However, in old monkeys, some of the paranodes of thick myelin sheaths are abnormal (Figure 7D) in that profiles of the paranodal loops are piled up on one another. Consequently some of the paranodal loops (asterisks in Figure 7D), ones arising from the outer lamellae of the myelin sheaths, fail to reach the axolemma.

Figure 7.

Electron microscopy of paranodal segments in monkey optic nerve. In young monkeys (A, AM53 shown here), the paranodal loops reach the axon membrane in an orderly progression and the paranodal loop from the outermost lamella of the sheath is nearest to the node (N). The majority of paranodes in old monkeys (B, AM91) are similar to the young, with all the paranodal loops abut the axon membrane and the outermost lamella being nearest to the node. High magnification of the paranodal region from a 30 year old animal, AM65 (C) shows the septate junctions (arrow) between the paranodal membrane and the axolemma. Some paranodes of thick myelin sheaths in older animals (D, AM41) demonstrate paranodal loops that appear piled up, so that a number of loops arising from the outer lamellae of the sheath (asterisks) do not reach the axon. Scale bar = 1 µm in A, B, and D; 0.4 µm in C.

Discussion

Age-dependent changes in myelin structure and composition have been proposed to contribute to age-related cognitive decline (Peters, 2002; Sloane et al., 2003). What effect these changes have on axonal integrity and neuronal function is not known, but it is presumed that myelin changes alter conduction velocity and thus slow the inter-neuronal connectivity required for higher level cognitive function. The data described here indicate that age-related changes in myelin do indeed result in alterations in the molecular architecture at the node of Ranvier, which may have functional consequences. The partial mislocalization of Kv1.2 into paranodal regions and the disorganized pattern of caspr staining in both older rats and monkeys suggest that axonal function at the node may be compromised with age.

The ultrastructural changes in internodal myelin with age include such phenomena as splitting at the major dense line to accommodate electron dense cytoplasm; splitting of the intraperiod line to produce fluid filled balloons; an increased occurrence of sheaths with redundant myelin resulting in sheaths too large for the enclosed axon; and some unusually thick myelin sheaths (Peters, 2002; Peters et al., 2001). It appears to be these thick sheaths that give rise to the paranodes with piled-up paranodal loops. Similar piled-up paranodes have been reported in electron microscopic analysis of 31 month old rats, in which some of the paranodal loops also fail to reach the axon and do not show junctional specialization (Sugiyama et al., 2002). Molecular reorganization at the paranode should, in theory coincide with ultrastructural change as one function of this region is to facilitate NaV clustering and node formation, however the axon-glia interactions are not completely understood. Thus, considering the present study examines only one proposed component of the paranodal axoglial complex, changes in caspr localization may not manifest at the ultrastructural level. This idea is evidenced in part by Sugiyama et al (2002) who report a profound loss of the 21.5 kDa isoform of myelin basic protein (MBP) together with subtle changes in paranodal structure.

The splitting of myelin sheaths in internodal myelin and the presently described paranodal alterations, particularly alterations in caspr localization, a known participant in the paranodal septate-like junction (Einheber et al., 1997), suggest an age-related deficiency in the ability of myelin to maintain adhesive junctions. Detailed analysis on the turnover of proteins involved in adhesive junctions and signaling complexes, particularly those in myelin, are scarce. The turnover of other myelin proteins such as myelin basic protein (MBP) and proteolipid protein (PLP) has been reported in the range of 40–100 days (Fischer and Morell, 1974; Sabri et al., 1974), and is 40% of the rate of whole brain (Lajtha et al., 1977) indicating a slow turnover. Therefore, maintenance of these complexes over time may present a unique challenge for myelin and the oligodendrocyte.

Implications of paranodal Kv1.2

Voltage-gated, Shaker-type delayed rectifying K+ channels, such as Kv1.1, Kv1.2, and Kv1.4, expressed along the length of myelinated axons normally localize to the juxtaparanode beneath internodal myelin sheaths (Chiu and Ritchie, 1980; Wang et al., 1993). The physiologic function of these heteromultimeric channels is not entirely clear. During PNS development, Kv1 channels localize in the nodal and paranodal regions and reduce the duration and refractory period of the action potential (Vabnick et al., 1999). Application of 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), a Kv channel antagonist, to myelinated fibers in the CNS increases the amplitude and duration of the action potential (Devaux et al., 2002), while application of 4-AP to myelinated fibers in the PNS has no effect on conduction (Rasband et al., 1998). In varying conditions of demyelinating injury and remyelination, Kv1 channels can mislocalize into paranodal and nodal regions and the application of 4-AP restores conduction (Bostock et al., 1981; Nashmi et al., 2000; Rasband et al., 1998; Targ and Kocsis, 1985; Targ and Kocsis, 1986), suggesting mislocalized Kv1 channels may stabilize membrane voltage at the K+ equilibrium potential (Rasband, 2004), which would serve to impede action potential conduction (Chiu, 1991). Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 mislocalize into the paranode in contactin, caspr, and cgt-null mice, and these animals all demonstrate slowed action potential conduction, which is at least partially rescued by 4-AP (Bhat et al., 2001; Boyle et al., 2001; Dupree et al., 1998). Though in the work presented here the effect of paranodal Kv1.2 on conduction in the optic nerve was not assessed, studies of transcallosal evoked compound action potentials measured in monkeys from the same population as those described in this study, indicate a decrease in amplitude of the P1 wave (fastest, myelinated fibers) with age (Rosene and Luebke, unpublished results), suggesting conduction abnormalities do exist elsewhere in the aged CNS.

What effect the application of 4-AP would have on nerve conduction in aged monkeys is not clear. The effects of mislocalized Kv channels in normal aging may constitute both pathogenic and/or compensatory processes. While inhibiting action potential propagation might seem counterproductive to neuronal function, in the case of aging, paranodal localization of Kv1 channels might recapitulate events of early development (Vabnick et al., 1999) and dampen the hyperexcitability of nerve fibers with damaged myelin, in exchange for increased axonal longevity and preserving cognitive performance. Indeed, increased action potential firing rates of pyramidal neurons in the prefrontal cortex of aged monkeys has been reported and an intermediate increase in firing rate correlates with cognitive performance (Chang et al., 2004). However, the long-term axonal effects of inhibiting Kv1 channels with 4-AP have not been studied.

While we investigated possible relationships between age-related changes in Kv channels in the optic nerve and behavioral impairments, it is clear the behavioral changes must reflect more central changes in the CNS. Hence, the lack of strong statistically significant correlations between paranodal Kv1.2 in axons of the optic nerve and global assessments of CNS behavior is not necessarily surprising. However, if Kv1.2 is mislocalized to paranodes throughout the aging CNS, as it is in the optic nerve, then it is likely that mislocalized paranodal Kv1.2, rather than simply indicating myelin damage, may alter conduction properties. Future studies examining changes in nodal organization, electrophysiology, and cognitive performance in the same animal using cognitively relevant tissues are an attractive frontier.

Maintenance of nodal NaV integrity with age

The lack of compact myelin structure in the Shiverer optic nerve results in diffuse NaV1.2 expression with few nodal profiles and little expression of NaV1.6 (Boiko et al., 2001). Sodium channel clustering is also altered in multiple sclerosis and dispersion of sodium channels throughout the length of demyelinated axons is thought to restore conduction and account for clinical remissions (Felts et al., 1997; Waxman, 2001). These studies suggested to us that the myelin changes incurred with aging might also alter sodium channel clustering. Despite this evidence, no significant change with age in either NaV expression or nodal structure could be detected in the rat optic nerve. Unfortunately, similar data for the monkey does not exist as monkey-specific antibodies for some NaV isoforms are not available. The absence of an age-related change in NaV channel expression is not necessarily surprising considering the vital role of NaV clusters in conduction. It appears that even in the face of age-related paranodal alterations, nodal structure and NaV channel integrity remains intact, suggesting additional mechanisms exist to regulate NaV over time and any age-related changes in conduction are the result of alterations in other ion channels, such as Kv1.2.

Axon versus myelin changes, which comes first?

One question that remains unanswered is whether myelin changes lead to axonal modifications or if the reverse is true. Our understanding of the axoglial relationship is changing daily, though it appears fairly reciprocal. Mice with myelin lipid abnormalities (cgt and cst-null mice) show similar axonal alterations as mice lacking neuronally expressed caspr and contactin (Boyle et al., 2001; Dupree et al., 1998; Ishibashi et al., 2002; Rios et al., 2003). Likewise, Cnp1-null mice lacking the exclusively oligodendrocyte-expressed enzyme, CNPase, show evidence of neurodegeneration and axonal swelling (Lappe-Siefke et al., 2003), suggesting evidence of intimate axoglial crosstalk. Perturbations in the biochemical composition of myelin are known to occur in middle-aged monkeys (Sloane et al., 2003) prior to any evidence of cognitive impairment. In studies of the anterior commissure of the rhesus monkey, myelin abnormalities appear to precede evidence of axon loss (Sandell and Peters, 2003) suggesting whatever abnormalities exist in nerve fibers with age are a result of myelin perturbations. The in vivo use of new advances in gene expression control such as RNAi, has the potential to address this question by altering single gene expression in a fully formed system of nodes. Whichever proves antecedent, axonal change or myelin, understanding molecular reorganization in the region of the node has the potential to clarify mechanisms of age-related cognitive decline.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

JDH acknowledges the National Institute of Aging (AG00115-18) and the American Federation for Aging Research for support. Additional support was provided by NIA P01-AG00001 and DNCCR P51-RR-000165. We thank all those who participated in behavioral assessment of monkeys.

Literature Cited

- Albert M. Neuropsychological and neurophysiological changes in healthy adult humans across the age range. Neurobiol Aging. 1993;14(6):623–625. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(93)90049-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo EJ, Xu T, Grinspan J, Lambert S, Levinson SR, Brophy PJ, Peles E, Scherer SS. Genetic dysmyelination alters the molecular architecture of the nodal region. J Neurosci. 2002;22(5):1726–1737. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01726.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo EJ, Xu T, Poliak S, Watson M, Peles E, Scherer SS. Internodal specializations of myelinated axons in the central nervous system. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;305(1):53–66. doi: 10.1007/s004410100403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat MA, Rios JC, Lu Y, Garcia-Fresco GP, Ching W, St Martin M, Li J, Einheber S, Chesler M, Rosenbluth J, Salzer JL, Bellen HJ. Axon-glia interactions and the domain organization of myelinated axons requires neurexin IV/Caspr/Paranodin. Neuron. 2001;30(2):369–383. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boiko T, Rasband MN, Levinson SR, Caldwell JH, Mandel G, Trimmer JS, Matthews G. Compact myelin dictates the differential targeting of two sodium channel isoforms in the same axon. Neuron. 2001;30(1):91–104. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostock H, Sears TA, Sherratt RM. The effects of 4-aminopyridine and tetraethylammonium ions on normal and demyelinated mammalian nerve fibres. J Physiol. 1981;313:301–315. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle ME, Berglund EO, Murai KK, Weber L, Peles E, Ranscht B. Contactin orchestrates assembly of the septate-like junctions at the paranode in myelinated peripheral nerve. Neuron. 2001;30(2):385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YM, Rosene DL, Killiany RJ, Mangiamele LA, Luebke JI. Increased Action Potential Firing Rates of Layer 2/3 Pyramidal Cells in the Prefrontal Cortex are Significantly Related to Cognitive Performance in Aged Monkeys. Cereb Cortex. 2004 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu SY. Functions and distribution of voltage-gated sodium and potassium channels in mammalian Schwann cells. Glia. 1991;4(6):541–558. doi: 10.1002/glia.440040602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu SY, Ritchie JM. Potassium channels in nodal and internodal axonal membrane of mammalian myelinated fibres. Nature. 1980;284(5752):170–171. doi: 10.1038/284170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craner MJ, Lo AC, Black JA, Waxman SG. Abnormal sodium channel distribution in optic nerve axons in a model of inflammatory demyelination. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 7):1552–1561. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaux J, Gola M, Jacquet G, Crest M. Effects of K+ channel blockers on developing rat myelinated CNS axons: identification of four types of K+ channels. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87(3):1376–1385. doi: 10.1152/jn.00646.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupree JL, Coetzee T, Blight A, Suzuki K, Popko B. Myelin galactolipids are essential for proper node of Ranvier formation in the CNS. J Neurosci. 1998;18(5):1642–1649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01642.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einheber S, Zanazzi G, Ching W, Scherer S, Milner TA, Peles E, Salzer JL. The axonal membrane protein Caspr, a homologue of neurexin IV, is a component of the septate-like paranodal junctions that assemble during myelination. J Cell Biol. 1997;139(6):1495–1506. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.6.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felts PA, Baker TA, Smith KJ. Conduction in segmentally demyelinated mammalian central axons. J Neurosci. 1997;17(19):7267–7277. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07267.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer CA, Morell P. Turnover of proteins in myelin and myelin-like material of mouse brain. Brain Res. 1974;74(1):51–65. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan L, Salomon D, Salzer JL, Peles E. Caspr regulates the processing of contactin and inhibits its binding to neurofascin. J Cell Biol. 2003;163(6):1213–1218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon JG, Moss MB, Rosene DL, Killiany RJ. Patterns of cognitive decline in aged rhesus monkeys. Behav Brain Res. 1997;87(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)02256-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinman JD, Duce JA, Siman RA, Hollander W, Abraham CR. Activation of calpain-1 in myelin and microglia in the white matter of the aged rhesus monkey. J Neurochem. 2004;89(2):430–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2004.02348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi T, Dupree JL, Ikenaka K, Hirahara Y, Honke K, Peles E, Popko B, Suzuki K, Nishino H, Baba H. A myelin galactolipid, sulfatide, is essential for maintenance of ion channels on myelinated axon but not essential for initial cluster formation. J Neurosci. 2002;22(15):6507–6514. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06507.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi T, Ikenaka K, Shimizu T, Kagawa T, Baba H. Initiation of sodium channel clustering at the node of Ranvier in the mouse optic nerve. Neurochem Res. 2003;28(1):117–125. doi: 10.1023/a:1021608514646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi-Abdolrezaee S, Eftekharpour E, Fehlings MG. Temporal and spatial patterns of Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 protein and gene expression in spinal cord white matter after acute and chronic spinal cord injury in rats: implications for axonal pathophysiology after neurotrauma. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19(3):577–589. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2004.03164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazarinova-Noyes K, Shrager P. Molecular constituents of the node of Ranvier. Mol Neurobiol. 2002;26(2–3):167–182. doi: 10.1385/MN:26:2-3:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox CA, Kokmen E, Dyck PJ. Morphometric alteration of rat myelinated fibers with aging. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1989;48(2):119–139. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227(259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajtha A, Toth J, Fujimoto K, Agrawal HC. Turnover of myelin proteins in mouse brain in vivo. Biochem J. 1977;164(2):323–329. doi: 10.1042/bj1640323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappe-Siefke C, Goebbels S, Gravel M, Nicksch E, Lee J, Braun PE, Griffiths IR, Nave KA. Disruption of Cnp1 uncouples oligodendroglial functions in axonal support and myelination. Nat Genet. 2003;33(3):366–374. doi: 10.1038/ng1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus J, Popko B. Galactolipids are molecular determinants of myelin development and axo-glial organization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1573(3):406–413. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TL, Killiany RJ, Herndon JG, Rosene DL, Moss MB. Impairment in abstraction and set shifting in aged rhesus monkeys. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(1):125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashmi R, Jones OT, Fehlings MG. Abnormal axonal physiology is associated with altered expression and distribution of Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 K+ channels after chronic spinal cord injury. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12(2):491–506. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peles E, Nativ M, Lustig M, Grumet M, Schilling J, Martinez R, Plowman GD, Schlessinger J. Identification of a novel contactin-associated transmembrane receptor with multiple domains implicated in protein-protein interactions. Embo J. 1997;16(5):978–988. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A. Structural changes in the normally aging cerebral cortex of primates. Prog Brain Res. 2002;136:455–465. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)36038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Sethares C. Aging and the myelinated fibers in prefrontal cortex and corpus callosum of the monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2002;442(3):277–291. doi: 10.1002/cne.10099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Sethares C. Is there remyelination during aging of the primate central nervous system? J Comp Neurol. 2003;460(2):238–254. doi: 10.1002/cne.10639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Sethares C, Killiany RJ. Effects of age on the thickness of myelin sheaths in monkey primary visual cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435(2):241–248. doi: 10.1002/cne.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliak S, Gollan L, Salomon D, Berglund EO, Ohara R, Ranscht B, Peles E. Localization of Caspr2 in myelinated nerves depends on axon-glia interactions and the generation of barriers along the axon. J Neurosci. 2001;21(19):7568–7575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07568.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband MN. It's "juxta" potassium channel! J Neurosci Res. 2004;76(6):749–757. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband MN, Kagawa T, Park EW, Ikenaka K, Trimmer JS. Dysregulation of axonal sodium channel isoforms after adult-onset chronic demyelination. J Neurosci Res. 2003;73(4):465–470. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband MN, Trimmer JS. Subunit composition and novel localization of K+ channels in spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 2001;429(1):166–176. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000101)429:1<166::aid-cne13>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband MN, Trimmer JS, Peles E, Levinson SR, Shrager P. K+ channel distribution and clustering in developing and hypomyelinated axons of the optic nerve. J Neurocytol. 1999;28(4–5):319–331. doi: 10.1023/a:1007057512576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband MN, Trimmer JS, Schwarz TL, Levinson SR, Ellisman MH, Schachner M, Shrager P. Potassium channel distribution, clustering, and function in remyelinating rat axons. J Neurosci. 1998;18(1):36–47. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00036.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KJ, Keilbaugh SA, Barrezueta NX, Lopez KL, Trimmer JS. Association and colocalization of K+ channel alpha- and beta-subunit polypeptides in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1995;15(7 Pt 2):5360–5371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05360.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios JC, Rubin M, St Martin M, Downey RT, Einheber S, Rosenbluth J, Levinson SR, Bhat M, Salzer JL. Paranodal interactions regulate expression of sodium channel subtypes and provide a diffusion barrier for the node of Ranvier. J Neurosci. 2003;23(18):7001–7011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-18-07001.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosene DL, Rhodes KJ. Cryoprotection and freezing methods for controlling ice crystal artifact in frozen sections of fixed and unfixed brain tissue. In: Conn PM, editor. Methods in Neuroscience. New York: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 360–385. [Google Scholar]

- Sabri MI, Bone AH, Davison AN. Turnover of myelin and other structural proteins in the developing rat brain. Biochem J. 1974;142(3):499–507. doi: 10.1042/bj1420499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandell JH, Peters A. Effects of age on nerve fibers in the rhesus monkey optic nerve. J Comp Neurol. 2001;429(4):541–553. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010122)429:4<541::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandell JH, Peters A. Disrupted myelin and axon loss in the anterior commissure of the aged rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2003;466(1):14–30. doi: 10.1002/cne.10859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer DP, Bansal R, Hedstrom KL, Pfeiffer SE, Rasband MN. Does paranode formation and maintenance require partitioning of neurofascin 155 into lipid rafts? J Neurosci. 2004;24(13):3176–3185. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5427-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloane JA, Hinman JD, Lubonia M, Hollander W, Abraham CR. Age-dependent myelin degeneration and proteolysis of oligodendrocyte proteins is associated with the activation of calpain-1 in the rhesus monkey. J Neurochem. 2003;84(1):157–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama I, Tanaka K, Akita M, Yoshida K, Kawase T, Asou H. Ultrastructural analysis of the paranodal junction of myelinated fibers in 31-month-old-rats. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70(3):309–317. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Hoshi T, Ishibashi T, Hayashi A, Yamaguchi Y, Baba H. Paranodal axoglial junction is required for the maintenance of the Nav1.6-type sodium channel in the node of Ranvier in the optic nerves but not in peripheral nerve fibers in the sulfatide-deficient mice. Glia. 2004;46(3):274–283. doi: 10.1002/glia.20008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targ EF, Kocsis JD. 4-Aminopyridine leads to restoration of conduction in demyelinated rat sciatic nerve. Brain Res. 1985;328(2):358–361. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targ EF, Kocsis JD. Action potential characteristics of demyelinated rat sciatic nerve following application of 4-aminopyridine. Brain Res. 1986;363(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vabnick I, Trimmer JS, Schwarz TL, Levinson SR, Risal D, Shrager P. Dynamic potassium channel distributions during axonal development prevent aberrant firing patterns. J Neurosci. 1999;19(2):747–758. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00747.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Kunkel DD, Martin TM, Schwartzkroin PA, Tempel BL. Heteromultimeric K+ channels in terminal and juxtaparanodal regions of neurons. Nature. 1993;365(6441):75–79. doi: 10.1038/365075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman SG. Acquired channelopathies in nerve injury and MS. Neurology. 2001;56(12):1621–1627. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.12.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolswijk G, Balesar R. Changes in the expression and localization of the paranodal protein Caspr on axons in chronic multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 7):1638–1649. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.