Summary

Long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA) are added to infant formula but their effect on long-term growth of children is under studied. We evaluated the effects of feeding LCPUFA-supplemented formula (n=54) compared to control formula (n=15) throughout infancy on growth from birth-6 years. Growth was described using separate models developed with the MIXED procedure of SAS® that included maternal smoking history and gender. Compared to children fed control formula, children who consumed LCPUFA supplemented formula had higher length-/stature-/and weight-for-age percentiles but not body mass index (BMI) percentile from birth to 6 years. Maternal smoking predicted lower stature (2-6 years), higher weight-for-length (birth-18 months) and BMI percentile (2-6 years) independent of LCPUFA effects. Gender interacted with the effect of LCPUFA on stature, and the relationship between smoking and BMI, with a larger effect for boys. Energy intake did not explain growth differences. A relatively small control sample is a limitation.

Keywords: LCPUFA, infant, DHA, child, BMI, growth

1. Introduction

It has been more than 10 years since long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), specifically docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid (ARA), were added to infant formulas in the US and worldwide in an effort to support vision and brain health. While more optimal growth was not the rationale for their addition to infant formula, weight and length (to 18 mo) or stature (beyond 2 years of age) are reported in many studies of LCPUFA supplemented term and preterm infants. The intent was primarily to determine if there were adverse effects of LCPUFA on growth. Recently, however, perinatal LCPUFA exposure has been linked to body composition in childhood [1-3]. Given that overweight and obesity are significant health concerns in the pediatric population and infants have been exposed to formulas with DHA and ARA since 2012, there is a need to understand if formula DHA and ARA fed to infants have either a positive or negative effect on growth or weight status.

Studies have compared actual or normalized weight and length assessments of LCPUFA-supplemented term infants to those of unsupplemented infants at various ages to 2 years but not observed differences in weight or length [4-8]. Only Auestad et al. [9] and de Jong et al. [6] report size after 3 years of age in children who were fed LCPUFA-supplemented compared to control formula as infants, but, again, they did not measure growth reporting a single measure of stature and weight at 39 mo and 9 years, respectively, and no effect.

None of these studies compared actual growth of LCPUFA supplemented and control term infants or controlled for differences in growth trajectories among children that may obscure treatment effects although growth has been measured in preterm infants [10, 11]. Serial measurements of weight and length in individual children are required to determine growth; and the growth trajectories of each child must be normalized to control for differences in growth among children before groups of children can be compared. Maternal smoking is associated with reduced linear growth [12, 13] and higher risk of overweight and obesity [12-15] in childhood and could obscure effects of supplementation on growth and weight status. Again, however, maternal smoking has not been accounted for in analyses for effects of LCPUFA.

The goal of the present study was to determine if there were differences in growth and weight status through 6 years of age in children fed LCPUFA or control formula from birth to12 months of age. We used data from a cohort of children for whom we had serial assessments of weight and length/stature to 6 years of age, maternal smoking history, child gender and dietary assessments. We controlled for the variation in growth within and among children.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Subjects

Healthy, singleton, term (37-42 weeks gestation), formula-fed infants were eligible for the study if they weighed between 2490 and 4550 grams at birth. All were born between September 2003 and October 2005. Only one child per family could participate. Infants were excluded if they were older than 9 days, had received human breast milk within 24 hours of randomization or if there were newborn health conditions known to interfere with normal growth and development or cognitive function (e.g., intrauterine growth restriction, congenital anomalies or established genetic disorders associated with intellectual disability). Infants were also excluded if they previously demonstrated any evidence of cows' milk formula intolerance or if born to mothers with physician-documented chronic illness (e.g., HIV, renal or hepatic disease, type 1 or 2 diabetes, alcoholism or other substance abuse). The research protocol and informed consent forms adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki (including the October 1996 amendment) and were approved by the Institutional Review Board/ethics committee at the University of Kansas Medical Center (HSC #9198 and #10205).

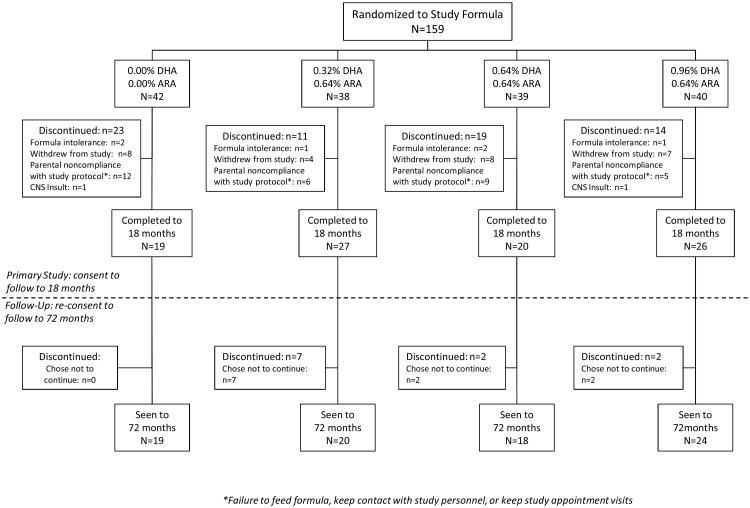

A total of 159 term infants enrolled into the original trial, DHA intake and measurement of neural development (DIAMOND) (16). At 18 months, the child's parents were invited to enroll for follow-up of their growth and development. A total of 81 parents consented to follow-up [16] and 69 children of these had anthropometric assessments at regular defined intervals from birth-6 years. These children constitute the sample evaluated for growth. Participant flow is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Participant flow in the primary and follow-up studies. Children who enrolled for followup were included in the present study, but their anthropometric data from birth to 6 years was included in the analysis.

Demographic data and maternal characteristics were collected through interviews and questionnaires. Mothers of infants enrolled in the study reported maternal weight, stature, education level, race and ethnicity, smoking before and during pregnancy, pack years (packs per day × years) of cigarette smoking before pregnancy and packs per day of cigarettes smoked during pregnancy among other information (Table 1). A high percentage of mothers of infants enrolled in the study smoked at some time before (n=73, 45.9%) or during (n=49, 30.8%) pregnancy. Characteristics of the enrolled trial sample, the follow-up sample and the 4 randomized groups were not statistically different [16].

Table 1. Participant Characteristics (no significant testing per CONSORT guidelines)1.

| Control (n=15) | LCPUFA supplemented (n=54) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Maternal race, % | ||||

| Black | 87 | 59 | ||

| Not black | 13 | 41 | ||

| Maternal ethnicity, % | ||||

| Hispanic | 0 | 9 | ||

| Not Hispanic | 100 | 91 | ||

| Maternal education, y | 12.1 | 1.8 | 11.9 | 1.4 |

| Maternal age, y | 22.9 | 4.1 | 23.7 | 4.4 |

| BMI at initial prenatal visit, kg/m2 | 29.1 | 7.3 | 29.0 | 7.1 |

| Pre-pregnancy weight status2, % | ||||

| Underweight | 0 | 2 | ||

| Normal | 33 | 33 | ||

| Overweight | 27 | 27 | ||

| Obese | 40 | 38 | ||

| History of smoking, % | 47 | 46 | ||

| History of smoking, pack yrs3 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 4.4 | 4.3 |

| Smoked during pregnancy, % | 20 | 31 | ||

| Cigarettes, per day | 5.0 | 2.6 | 6.2 | 7.0 |

Means and SDs were determined using EXCEL 2013 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA);

Compared to Institute of Medicine guidelines (15);

years smoked × packs per day

2.2 Design and randomization

Infants were stratified by gender and randomly assigned to one of four ready-to-feed formulas from birth to 12 months. The formulas varied only in LCPUFA content (DHA/ARA = 0/0%, 0.32/0.64%, 0.64/0.64%, and 0.96/0.64% of total fatty acids) [17] and were provided by Mead Johnson Nutrition. Formulas were blinded to both the investigator and participant by use of an eight colored labeling scheme and provided to participants by courier monthly or more frequently as needed.

2.3 Anthropometric and dietary assessments

Weight, length/stature and 24-hour dietary recalls were obtained at 6-weeks, 4, 6, 9 and 12 months and at 6-month intervals from 12 months to 6 years by trained registered dietitians. Birth weight and length were obtained from hospital records. Body weight was recorded without clothing or diaper to the nearest gram on a pediatric scale until 18 months and in the lightest layer of clothing to the nearest 0.1 kg on an electronic scale from 2 to 6 years. Length and stature were measured without shoes to the nearest 0.1 cm on a length board or a stadiometer from 0 to18 months and 2 to 6 years, respectively. All anthropometric data were converted percentiles using The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Epi Info™ version 3.5.4 (CDC, Atlanta, GA, USA).

A three-pass procedure originally developed by the US Department of Agriculture to improve the quality of self-report was used for 24-hour dietary recall assessment [18]. Dietary recalls were entered into NDS-R® version 4.06 (University of Minnesota, MN, USA) to obtain energy intake and checked by another dietitian. Mean daily energy intakes were generated for each child.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Growth among the three LCPUFA supplemented groups did not differ, thus groups were collapsed as LCPUFA supplemented (n=54) and compared to infants not supplemented with LCPUFA (n=15). Weight-for-age, length (or stature)-for-age, and weight-for-length percentiles from birth to18 months or BMI and BMI-for-age percentiles from 2 to 6 years, and energy intake were analyzed using the MIXED procedure of SAS® version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). This allowed for use of incomplete observations and missing data. Linear models were developed using a restricted maximum-likelihood estimation approach. An autoregressive covariance structure with homogeneous variances was incorporated into each model. Maternal smoking at any time prior to or during pregnancy was a dichotomous covariate used in analyses. Maternal smoking during pregnancy generally yielded similar estimates but less powerful comparisons between subclasses. Maternal age and years of education were excluded based on analyses indicating no relationship with childhood growth after adjusting for other covariates.

Growth was reported separately for birth to 18 months (Table 2) and 2 to 6 years (Table 3) in accordance with current CDC recommendations [19]. For each dependent variable a random coefficients model was used to incorporate the effect of age in the model with both random intercepts and slopes (linear effect only or linear and quadratic effects) being estimated for each subject and simultaneously estimating the fixed or mean effects of age (linear effect only or linear and quadratic effects), LCPUFA supplementation, maternal smoking, gender, and the two- and three-way interaction effects between/among the classification covariates and the two-way interactions between the continuous and classification covariates. All interactions among classification covariates that were not significant were removed from the respective models. None of the interaction effects involving age were statistically significant, indicating that the assumption of a common slopes model was valid. For length-for-age percentiles from birth to18 months, the quadratic effect of age was added to the model. Least-squares means for main effects and interaction effects were compared using five planned contrasts. No adjustment to the alpha level was made for these contrasts.

Table 2. Anthropometric status of study subjects from birth - 18 months (mean±SD).

| Birth | 6 wk | 4 mo | 6 mo | 9 mo | 12 mo | 18 mo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight, kg | 3.4±0.4 | 4.8±0.5 | 6.7±0.7 | 7.8±0.8 | 8.9±0.9 | 9.8±1.1 | 11.5±1.3 |

| Length, cm | 50.0±1.7 | 55.3±2.0 | 63.0±2.6 | 67.1±2.6 | 71.2±2.7 | 75.3±2.8 | 83.3±3.6 |

| Weight-for-length, %ile* | 51.6±29.0 | 55.9±27.4 | 54.1±26.8 | 53.2±29.5 | 59.9±28.5 | 56.3±29.9 | 52.0±32.6 |

Weight-for-length percentile calculated based on the 2000 CDC growth chart

Table 3. Anthropometric status of study subjects (mean±SD) or number (%) from 2 - 6 years.

| 2 yr | 2.5 yr | 3 yr | 3.5 yr | 4 yr | 4.5 yr | 5 yr | 5.5 yr | 6 yr | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight, kg | 12.8±1.5 | 14.0±1.8 | 15.2±2.4 | 16.5±2.8 | 17.6±3.0 | 19.1±3.6 | 20.3±4.0 | 21.7±4.4 | 23.3±5.0 |

| Length, cm | 88.2±3.6 | 92.7±3.7 | 96.4±4.5 | 99.3±4.7 | 102.2±5.2 | 106.1±5.2 | 109.6±5.4 | 112.9±5.7 | 116.2±5.5 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 16.5±1.6 | 16.2±1.6 | 16.4±1.8 | 16.6±1.8 | 16.7±1.9 | 16.9±2.3 | 16.8±2.2 | 16.9±2.3 | 17.1±2.5 |

| BMI %ile* | 46.3±27.9 | 50.3±30.5 | 56.6±30.3 | 66.5±27.3 | 70.9±28.2 | 71.1±27.7 | 69.9±26.5 | 71.6±27.3 | 71.3±25.5 |

| Overweight, n (%)† | 1 (1.5) | 9 (13.4) | 5 (7.2) | 12 (17.6) | 18 (26.5) | 12 (17.6) | 11 (16.2) | 16 (23.5) | 10 (14.5) |

| Obese, n (%)† | 7 (10.3) | 4 (6.0) | 8 (11.6) | 9 (13.2) | 12 (17.6) | 16 (23.5) | 16 (23.5) | 14 (20.6) | 16 (23.2) |

BMI percentile calculated based on the 2000 CDC growth chart

Overweight and obese defined as >85th and >95%ile, respectively (CDC)

3. Results

3.1 Weight status and energy intake of the cohort

We determined the proportion of children who were overweight and obese at 6 month intervals from 2 to 6 years of age using the CDC classification systems for overweight and obesity (Table 3). Approximately 40% of the children in this cohort were overweight or obese after 4 years of age. The total percent changed little but the ratio of obese to overweight appeared to increase between 4 and 6 years of age. Energy intake was unrelated to LCPUFA supplementation (P = 0.78), mother ever smoking (P = 0.32), gender (P = 0.24), and age (P = 0.39) (Table 4).

Table 4. Estimates of the least-squares means and standard errors of the main effects of LCPUFA supplementation and maternal smoking at any time on growth percentiles during infancy/toddlerhood and early childhood of 69 children, after controlling for other variables in the modelsa.

| Dependent Variable | LCPUFA supplementation | Maternal smoking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| No | Yes | P-value | No | Yes | P-value | |

| Birth-18 month | ||||||

| Weight-for-age percentile | 50.0±3.8 | 54.5±2.6 | 0.26 | 55.8±3.0 | 48.6±3.5 | 0.08 |

| Length-for-age percentile | 53.1±3.7 | 61.8±2.4 | 0.04 | 62.0±2.9 | 52.9±3.3 | 0.03 |

| Weight-for-length percentile | 57.7±3.5 | 54.2±2.1 | 0.39 | 51.3±2.6 | 60.6±3.1 | 0.02 |

| 2-6 years | ||||||

| Weight-for-age percentile | 49.8±12.0 | 68.0±10.8 | 0.02 | 58.9±11.2 | 58.9±11.7 | 0.99 |

| Stature-for-age percentile | 46.5±4.6 | 59.1±3.5 | 0.001 | 60.8±3.8 | 44.8±4.3 | 0.001 |

| BMIb | 16.6±0.4 | 16.9±0.4 | 0.38 | 16.4±0.4 | 17.2±0.4 | 0.02 |

| BMIb-for-age percentile | 61.2±4.8 | 67.8±3.2 | 0.20 | 57.8±3.8 | 71.2.±4.4 | 0.01 |

| Average energy intake (kcal) | 1536±81 | 1563±48 | 0.78 | 1503±60 | 1596±73 | 0.33 |

Each statistical model contained the fixed effects of LCPUFA supplementation, maternal smoking at any time, gender, the two- and three-way interactions of supplementation, gender, and smoking, the linear (or linear and quadratic) effect of age, and the random effect of child nested within supplementation-smoking-gender subclasses; random coefficients for the intercept and slope(s) were estimated for each child. Degrees of freedom = 61, reflecting the degrees of freedom associated with the pooled between child estimated variance.

BMI is body mass index.

3.2 Weight-for-age percentiles

From birth to 18 months, weight-for-age percentiles were independent of LCPUFA supplementation (P = 0.26), smoking at any time (P = 0.07) and age (P = 0.50), but significantly higher for girls than for boys (59.5 ± 2.9 vs. 44.9 ± 3.6, P=0.0005). From 2 to 6 years, children who consumed LCPUFA supplemented formula as infants had higher weight-for-age percentiles compared to those who consumed the control formula (68.0 ± 10.8 vs 49.8 ± 12.0; P = 0.02) (Table 2) while maternal smoking history and gender did not affect weight-for-age percentiles.

3.3 Length/Stature-for-age percentiles

Children supplemented with LCPUFA were longer than unsupplemented children from birth to18 months (P = 0.033) and taller from 2 to 6 years (P = 0.007). In contrast, maternal smoking was associated with a lower length-for-age percentile from birth to18 months (P = 0.03) and a lower stature-for-age percentile from 2 to 6 years (P = 0.0007) (Table 4). In the LCPUFA supplemented group, children of women who had ever smoked had lower length-for-age percentile (56.8 ± 3.4 vs. 66.7 ± 2.7, P = 0.015) and shorter stature-for-age percentile (49.7 ± 4.4 vs. 68.4 ± 3.7, P = 0.0001) compared to children whose mothers never smoked. Girls length and stature-for-age percentiles were greater than those of boys from birth to18 months (P = 0.0002) and from 2 to 6 years (P = 0.02). The only statistically significant interaction was between LCPUFA and gender from birth to18 months (P=0.03), which indicated a larger effect of LCPUFA in boys compared to girls.

From birth to 18 months, the average child's length percentile remained relatively constant (P = 0.10); however, from 2 to 6 years the stature percentile of the average child decreased by 3.5% per year (P<0.0001) (Table 5).

Table 5. Estimates of the mean effect of age and standard errors on growth percentiles during infancy and early childhood of 69 children, after controlling for LCPUFA supplementation and maternal smokinga.

| Dependent Variable | Age | Estimate | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth-18 month | |||

| Weight-for-age percentile | Linear | -0.19±0.28 | 0.50 |

| Length-for-age percentile | Linear | 0.43±0.26 | 0.11 |

| Weight-for-length percentile | Linear | 1.27±0.69 | 0.08 |

| Weight-for-length percentile | Quadratic | -0.07±0.04 | 0.09 |

| 2-6 years | |||

| Weight-for-age percentile | Linear | 1.42±2.64 | 0.60 |

| Stature-for-age percentile | Linear | -3.47±0.73 | <0.0001 |

| BMI percentile | Linear | 0.19±0.09 | <0.05 |

| BMI-for-age percentile | Linear | 6.47±0.73 | <0.0001 |

| Average energy intake (kcal) | Linear | -14.59±16.51 | 0.38 |

Each statistical model contained the fixed effects of LCPUFA supplementation, gender, maternal smoking at any time, the two- and three-way interactions of supplementation, gender and smoking, the linear (or linear and quadratic) effect of age, and the random effect of child nested within supplementation-smoking subclasses; random coefficients for the intercept and slope(s) were estimated for each child. Thus, the fixed effects of age are the estimates of the mean regression coefficients. Degrees of freedom = 68, reflecting the degrees of freedom associated with the pooled within child estimated variance.

3.4 Weight-for-length and BMI-for-age percentiles

From birth to18 months, weight-for-length was independent of LCPUFA supplementation (P = 0.83); however, maternal smoking was associated with a higher infant weight-for-length compared with non-smoking (60.6 ± 3.1 vs 51.3 ± 2.6; P = 0.02) (Table 4). This same trend was observed in the subgroups that consumed LCPUFA (57.3 ± 3.2 vs. 51.2 ± 2.5, P=0.12) and in the subgroups that consumed the control formula (63.9 ± 5.2 vs. 51.4 ± 4.5, P=0.08).

From 2 to 6 years, BMI was independent of LCPUFA supplementation (P = 0.38) and gender (P = 0.11) but maternal smoking was associated with higher BMI (P = 0.02) (Table 4). Similarly, BMI-for-age percentiles from 2 to 6 years were not influenced by LCPUFA supplementation (P = 0.20) or gender (P = 0.15) but maternal smoking was associated with higher BMI percentiles (P = 0.01). Infants fed the control formula whose mothers smoked also had a higher mean BMI percentile than that of mothers who did not smoke (72.2 ± 6.9 vs. 50.3 ± 6.0, P=0.02) but maternal smoking did not significantly influence BMI percentile in the group fed LCPUFA. There was a significant interaction between maternal smoking and gender indicating that maternal smoking had a larger impact on boys' BMI percentile compared with that of girls (P = 0.004). For every year's increase between 2 to 6 years, BMI increased by about 0.2±0.1 units (P< 0.05) and BMI-for-age percentile increased by 6.5 ± 0.7% (P<0.0001) (Table 5).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In the first 18 months of life, infants fed LCPUFA-supplemented formula had higher linear growth than controls but their weight-for-age was not greater in agreement with others [4-8, 17, 20] suggesting they were somewhat leaner than controls. From 2 to 6 years of age, however, LCPUFA-supplemented infants had greater stature-for-age and weight-for-age percentiles than controls but similar BMI or BMI percentile-for-age. Although these results indicate children fed LCPUFA are larger, they suggest that their weight and stature growth is proportional; i.e., that LCPUFA does not predispose them to be overweight. Males compared to females had a greater increase in stature with LCPUFA supplementation. The differences in growth with LCPUFA were not explained by estimated energy intake.

Past studies have not found an effect of LCPUFA-supplementation on growth, but a closer examination of the methods used for analysis reveals that what is described as growth is typically a comparison or series of comparisons of groups' weight and length at different ages. This appears to be the analysis even when sequential measures of weight and length are available to develop a growth trajectory and control for differences in growth trajectories among children. Thus previous findings of “no effect” could be attributed to limitations in the analyses. Additionally, these studies typically do not follow children beyond 2 years of age when early effects of programming might emerge (1-3). Only two prior randomized LCPUFA studies in infancy have reported weight and length in childhood (6, 9) again finding no effect of LCPUFA possibly because of the same limitations as studies done in younger children.

Based on our results, studies designed to look at growth should stratify for maternal smoking because maternal smoking is associated with reduced length/stature, an outcome counter to the effects of LCPUFA. Because smoking was not related to lower weight-for-age percentile or energy intake, children of smoking mothers had higher BMI. The positive relationship between maternal smoking and BMI favored males over females. As a whole, this cohort of children has a high incidence of overweight and obese weight status based on BMI, with 23% obese by 4.5 years of age. Some of that appears to be attributable to maternal smoking but it is generally believed that many factors contribute to the high incidence of obesity in US children. We anticipated lower linear growth and higher BMI in children of smokers based on previous reports [4, 12-15]. Maternal smoking has been associated with shorter length at birth and reduced stature to age eight (12, 13), and several studies find maternal smoking during gestation associated with risk of becoming overweight or obese later in childhood or later in life (12-15). The effects of LCPUFA and maternal smoking were independent, i.e., there was no interaction between LCPUFA and maternal smoking on any assessment of growth or weight status.

A major strength of the study was the number of longitudinal assessments of weight and length/stature that we obtained from birth to 6 years, which allowed us to determine the growth trajectory of each child for every outcome variable and each child to serve as his/her own control [10, 11]. This is in contrast to previous studies that have compared growth at different ages and not controlled for child, maternal smoking or gender when comparing LCPUFA supplemented to unsupplemented term infants. We were able to show that the effects of maternal smoking on stature were independent of the effects of LCPUFA, and that they had opposite effects. A limitation of the study was the relatively small number of children who were fed the control formula. Thus a type 1 error could account for the finding that LCPUFA supplementation increased weight- and length-for-age percentiles; and a type 2 error could account for the finding that BMI percentile was not affected by LCPUFA supplementation.

In summary, LCPUFA-supplementation in infancy predicted higher length in infancy and higher weight and stature-for-age percentiles from 2 to 6 years but no increase in BMI or BMI-for-age percentile. Our results do not suggest that LCPUFA supplementation has an adverse effect on child growth or weight status. If anything, they suggest that LCPUFA could have positive effects on stature without negative effects on weight status; and that LCPUFA could mitigate lower stature and higher BMI associated with maternal smoking, particularly in boys. Maternal smoking likely modifies the effects of LCPUFA supplementation on growth and should be considered as a stratifying variable in future studies of growth and body composition.

Highlights.

Infants fed LCPUFA formula were larger birth-6 years but BMI was not different

Maternal smoking predicted shorter stature and higher BMI without interaction

Maternal smoking should be a stratifying variable in studies of LCPUFA and growth

Estimated energy intake did not account for any differences in growth observed

Acknowledgments

We thank Mead Johnson Nutrition for funding, numerous Dietetics and Nutrition Department MS students who assisted with data collection and entry and the parents of our participants. SEC and JC designed the parent study with Mead Johnson Nutrition. The data were the MS thesis for LMC. EAT did the final statistical analysis. LMC, EAT and SEC wrote the paper and SEC and EAT had primary responsibility for the final content. DKS had primary responsibility for dietary assessment. JMT and EHK coordinated the study and had primary responsibility for day-to-day management of the study including all nutritional assessments, data entry and management and supervision of MS students. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

List of abbreviations

- ARA

arachidonic acid

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- BMI

body mass index

Footnotes

Supported by Mead Johnson Nutrition and a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HD047315).

Clinical trial registry: clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00753818

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Donahue SM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Gold DR, Jouni ZE, Gillman MW, Oken E. Prenatal fatty acid status and child adiposity at age 3 y: results from a US pregnancy cohort. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2011;93:780–788. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.005801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moon RJ, Harvey NC, Robinson SM, Ntani G, Davies JH, Inskip HM, Godfrey KM, Dennison EM, Calder PC, Cooper C. Maternal plasma polyunsaturated fatty acid status in late pregnancy is associated with offspring body composition in childhood. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;98:299–307. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen AD, Michaelsen KF, Hellgren LI, Trolle E, Lauritzen L. A randomized controlled intervention with fish oil versus sunflower oil from 9 to 18 months of age: exploring changes in growth and skinfold thicknesses. Pediatric research. 2011;70:368–374. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318229007b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makrides M, Neumann MA, Simmer K, Gibson RA. Dietary long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids do not influence growth of term infants: A randomized clinical trial. Pediatrics. 1999;104:468–475. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.3.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birch EE, Castaneda YS, Wheaton DH, Birch DG, Uauy RD, Hoffman DR. Visual maturation of term infants fed long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid-supplemented or control formula for 12 mo. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2005;81:871–879. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.4.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Jong C, Boehm G, Kikkert HK, Hadders-Algra M. The Groningen LCPUFA study: No effect of short-term postnatal long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in healthy term infants on cardiovascular and anthropometric development at 9 years. Pediatric research. 2011;70:411–416. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31822a5ee0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auestad N, Halter R, Hall RT, Blatter M, Bogle ML, Burks W, Erickson JR, Fitzgerald KM, Dobson V, Innis SM, Singer LT, Montalto MB, Jacobs JR, Qiu W, Bornstein MH. Growth and development in term infants fed long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids: a double-masked, randomized, parallel, prospective, multivariate study. Pediatrics. 2001;108:372–381. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Auestad N, Montalto MB, Hall RT, Fitzgerald KM, Wheeler RE, Connor WE, Neuringer M, Connor SL, Taylor JA, Hartmann EE. Visual acuity, erythrocyte fatty acid composition, and growth in term infants fed formulas with long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids for one year. Ross Pediatric Lipid Study. Pediatric research. 1997;41:1–10. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199701000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Auestad N, Scott DT, Janowsky JS, Jacobsen C, Carroll RE, Montalto MB, Halter R, Qiu W, Jacobs JR, Connor WE, Connor SL, Taylor JA, Neuringer M, Fitzgerald KM, Hall RT. Visual, cognitive, and language assessments at 39 months: a follow-up study of children fed formulas containing long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids to 1 year of age. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e177–183. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.e177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson SE, Cooke RJ, Werkman SH, Tolley EA. First year growth of preterm infants fed standard compared to marine oil n-3 supplemented formula. Lipids. 1992;27:901–907. doi: 10.1007/BF02535870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson SE, Werkman SH, Tolley EA. Effect of long-chain n-3 fatty acidsupplementation on visual acuity and growth of preterm infants with and without bronchopulmonary dysplasia. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1996;63:687–697. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen A, Pennell ML, Klebanoff MA, Rogan WJ, Longnecker MP. Maternal smoking during pregnancy in relation to child overweight: follow-up to age 8 years. International journal of epidemiology. 2006;35:121–130. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koshy G, Delpisheh A, Brabin BJ. Dose response association of pregnancy cigarette smoke exposure, childhood stature, overweight and obesity. European journal of public health. 2011;21:286–291. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendez MA, Torrent M, Ferrer C, Ribas-Fito N, Sunyer J. Maternal smoking very early in pregnancy is related to child overweight at age 5-7 y. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2008;87:1906–1913. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fasting MH, Oien T, Storro O, Nilsen TI, Johnsen R, Vik T. Maternal smoking cessation in early pregnancy and offspring weight status at four years of age. A prospective birth cohort study. Early human development. 2009;85:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colombo J, Carlson SE, Cheatham CL, Shaddy DJ, Kerling EH, Thodosoff JM, Gustafson KM, Brez C. Long-term effects of LCPUFA supplementation on childhood cognitive outcomes. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2013;98:403–412. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.040766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birch EE, Carlson SE, Hoffman DR, Fitzgerald-Gustafson KM, Fu VL, Drover JR, Castaneda YS, Minns L, Wheaton DK, Mundy D, Marunycz J, Diersen-Schade DA. The DIAMOND (DHA Intake And Measurement Of Neural Development) Study: a double-masked, randomized controlled clinical trial of the maturation of infant visual acuity as a function of the dietary level of docosahexaenoic acid. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2010;91:848–859. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanton CA, Moshfegh AJ, Baer DJ, Kretsch MJ. The USDA Automated Multiple-Pass Method accurately estimates group total energy and nutrient intake. The Journal of nutrition. 2006;136:2594–2599. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.10.2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Wei R, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital and health statistics Series 11, Data from the national health survey. 2002:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makrides M, Duley L, Olsen SF. Marine oil, and other prostaglandin precursor, supplementation for pregnancy uncomplicated by pre-eclampsia or intrauterine growth restriction. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2006:Cd003402. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003402.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]