Abstract

The c-Src tyrosine kinase co-operates with the focal adhesion kinase to regulate cell adhesion and motility. Focal adhesion kinase engages the regulatory SH3 and SH2 domains of c-Src, resulting in localized kinase activation that contributes to tumor cell metastasis. Using assay conditions where c-Src kinase activity required binding to a tyrosine phosphopeptide based on the focal adhesion kinase SH3-SH2 docking sequence, we screened a kinase-biased library for selective inhibitors of the Src/focal adhesion kinase peptide complex versus c-Src alone. This approach identified an aminopyrimidinyl carbamate compound, WH-4-124-2, with nanomolar inhibitory potency and fivefold selectivity for c-Src when bound to the phospho-focal adhesion kinase peptide. Molecular docking studies indicate that WH-4-124-2 may preferentially inhibit the ‘DFG-out’ conformation of the kinase active site. These findings suggest that interaction of c-Src with focal adhesion kinase induces a unique kinase domain conformation amenable to selective inhibition.

Keywords: Src kinase, focal adhesion kinase, SH3 domain, SH2 domain, kinase inhibitors, cancer drug discovery

The c-Src protein-tyrosine kinase is the prototype of the Src kinase family and is broadly expressed in virtually every mammalian cell type (1). All eight mammalian Src-family kinases (SFKs) share a common regulatory and kinase domain organization (Figure 1A). At the N-terminus is a signal sequence for myristoylation, which localizes c-Src to the cell membrane. Membrane association facilitates interactions of c-Src with binding partners and is essential for function (2). The myristoylation signal is followed by a unique domain, modular SH3 and SH2 domains, an SH2-kinase linker, the kinase domain, and a C-terminal tail with a conserved tyrosine residue essential for negative regulation of kinase activity. The SH3 and SH2 domains, which recognize proline-rich and phosphotyrosine-containing sequences, respectively, are important for kinase regulation as well as interactions with other cellular proteins.

Figure 1.

Structure and domain organization of c-Src and focal adhesion kinase (FAK). (A) Crystal structure of c-Src in the downregulated conformation (PDB ID: 2SRC) showing the SH3 domain, SH3-SH2 connector, the SH2 domain, the SH2-kinase linker, the kinase domain, and the C-terminal tail. Key kinase domain features include the N-lobe, activation loop, αC-helix, and C-lobe. The side chains of the conserved tyrosine residues in the activation loop (Y416) and the tail (pY527) are also shown. Intramolecular interactions between the SH3 domain and the SH2-kinase linker as well as the SH2 domain and the tyrosine-phosphorylated tail are required to maintain the inactive state. The modular domain organization of c-Src is shown below the structure, which includes a myristoylated N-terminal domain not present in the crystal structure. The organization of the recombinant Src-YEEI protein used for this study is also shown, in which the N-terminal unique domain is replaced with a His-tag and the C-terminal tail sequence is modified to encode YEEI. (B) FAK consists of an N-terminal FERM domain, central kinase domain, and a C-terminal FAT domain. The linker connecting the FERM and kinase domains encompasses the binding site for c-Src, consisting of a PxxP motif (SH3 binding) and an autophosphorylation site in the sequence context pYAEI (SH2 binding). The sequence of the pFAK peptide based on this region and used in the inhibitor screen is also shown, with the Src SH3 and SH2 binding sites underlined.

SFKs maintain their inactive state through two intramolecular interactions involving the SH2 and SH3 domains. The SH3 domain interacts with a polyproline type II helix formed by the SH2-kinase linker while the SH2 domain binds to the tyrosine-phosphorylated tail (3). Tail phosphorylation is mediated by the independent regulatory kinase Csk as well as the related kinase, Chk (4,5). These intramolecular regulatory interactions are present in the X-ray crystal structure of c-Src in the downregulated conformation (modeled in Figure 1A) (6).

Multiple mechanisms of SFK activation have been reported, including dephosphorylation of the C-terminal tail tyrosine and subsequent release from the SH2 domain (7) as well as displacement of one or both of the intramolecular interactions in trans (8,9). Based on their amino acid sequences, the SH2-kinase linker and phosphorylated C-terminal tail represent low affinity ligands for their respective target domains. Displacement of these interactions by proteins with higher affinities for the SH3 and/or SH2 domains provides a mechanism for SFK activation by both physiological substrates as well as exogenous proteins expressed as a result of microbial infection. For example, the Nef protein encoded by HIV-1 binds to the SH3 domain of the Src-family member Hck, resulting in linker displacement and constitutive kinase activation (10,11). Alternatively, juxtamembrane autophosphorylation sites on active receptor tyrosine kinases may recruit c-Src through its SH2 domain, resulting in kinase activation through tail displacement. Other cellular protein partners for c-Src contain both SH3- and SH2-binding sequences believed to displace both intramolecular interactions, such as p130Cas (12) and the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (13).

Focal adhesion kinase is a non-receptor protein-tyrosine kinase that localizes to focal adhesions, the intracellular structures formed at sites of cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix (ECM). The domain organization of FAK consists of a protein 4.1/ezrin/radixin/moesin (FERM) domain, followed by binding sites for the c-Src SH3 and SH2 domains (Figure 1B). The kinase domain of FAK is located in the center of the protein, followed by a proline-rich region with binding sites for the SH3 domains of p130Cas and other components of the focal adhesion complex. The C-terminal end of FAK encompasses the focal adhesion targeting (FAT) domain which localizes FAK to focal adhesions in response to integrin stimulation (14–16). Upon recruitment to focal adhesions, FAK undergoes autophosphorylation on Y397, creating a high-affinity binding site for the c-Src SH2 domain. Additionally, the c-Src SH3 domain binds to the proline-rich sequence adjacent to the SH2 binding site. These tandem binding events displace both intramolecular regulatory interactions, leading to c-Src kinase activation. This mechanism integrates relocalization of c-Src to focal contacts with kinase activation, providing an elegant mechanism for spatial and temporal regulation of c-Src function.

Active c-Src phosphorylates FAK at multiple tyrosine residues, including kinase domain activation loop tyrosines important for full FAK kinase activity (17). Coordinated activation of c-Src and FAK stimulates multiple signaling pathways linked to focal adhesion turnover and cell migration, an essential process in embryonic development, wound healing, and the immune response (17). Cells lacking c-Src and FAK show a dramatically reduced rate of migration (18,19) while hyperactivation of these kinases leads to an increased rate of migration that has been implicated in tumorigenesis. Indeed, overexpression and increased activity of both c-Src and FAK have been reported in multiple tumor sites (17,20).

The relationship of the c-Src:FAK complex to cancer progression highlights the potential for c-Src and FAK as targets for cancer therapy (21–24). Multiple inhibitors of both c-Src and FAK have been discovered, and some have progressed into clinical trials. However, the success of these inhibitors, especially as monotherapy, has been limited (20,25). In this study, we hypothesized that binding of FAK to c-Src induces a unique disease-associated conformation of the Src active site that may be amenable to selective inhibitor targeting. In an effort to find a selective inhibitor of c-Src in the FAK-bound state, we first developed screening assay conditions where c-Src activity was entirely dependent on the presence of a phosphopeptide based on the FAK sequences for c-Src SH3/SH2 binding. We then screened a small, kinase-biased inhibitor library and identified several compounds selective for the c-Src: pFAK peptide complex versus c-Src alone. The most promising compound showed a fivefold preference for the active complex in both end-point and kinetic kinase assays and inhibited the complex with nanomolar potency. Computational docking studies suggest that this compound prefers the ‘DFG-out’ conformation of the kinase active site, suggesting that binding of the pFAK peptide induces this c-Src kinase domain conformation. Our results provide an important proof-of-concept result that state-selective ATP-site inhibitors for c-Src can be identified under appropriate screening assay conditions. This approach may provide a new path to the discovery of state and context-selective inhibitors for large kinase families with highly homologous active sites.

Materials and Methods

Expression and purification of recombinant Src-YEEI

A human c-Src cDNA clone was modified on its C-terminal tail to encode the sequence Tyr-Glu-Glu-Ile-Pro (‘YEEI’) as described elsewhere (26). In addition, the N-terminal unique domain was replaced with a hexa-histidine tag. The resulting sequence was used to produce a recombinant baculovirus in Sf9 insect cells using BaculoGold DNA and the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Pharmingen) as previously described (27). Src-YEEI was co-expressed with the Yersinia pestis YopH phosphatase to promote dephosphorylation of the activation loop tyrosine and maintain the downregulated state (28,29). Sf9 cells were grown in monolayer cultures and co-infected with the Src-YEEI and YopH baculoviruses. Cells were harvested 72 h after infection, and Src-YEEI was purified as previously described (27). Purified Src-YEEI protein was stored in 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.3, containing 100 mM NaCl. Kinase protein used in the Z’Lyte in vitro kinase assays also contained 3 mM DTT. The molecular weight of purified Src-YEEI was confirmed by mass spectrometry and determined to be phosphorylated on the YEEI tail but not the activation loop (26), consistent with the structure of the downregulated conformation (6).

Chemical library screen

A library of 586 kinase-biased inhibitors (30,31) was screened using the FRET-based Z’Lyte in vitro kinase assay and Tyr2 peptide substrate (Life Technologies) (32). Assays were performed in quadruplicate in 384-well low-volume, non-binding, black polystyrene microplates (Corning) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as described previously (27,33,34). Briefly, the assay measures phosphorylation of the Tyr2 FRET-peptide substrate which is labeled with coumarin and fluorescein on its Nand C-terminii, respectively, which form a FRET pair. After the kinase reaction, a development step involves site-specific proteolytic cleavage of the unphosphorylated but not the phosphorylated peptide. Peptide cleavage results in loss of the FRET signal. Src-YEEI was first titrated into the assay over a concentration range of 0.5–500 ng/well (0.908–908 nM). Kinase activity was measured in the absence and presence of a 10-fold molar excess of a pFAK peptide with the sequence AAAARALPSIPKLAN NEKQGVRSHTVSVSETDDYPAEIID (13), as well as the control peptides pYEEI (EPQYPEEIPIYL) (35), and VSL12 (VSLARRPLPPLP) (36). All peptides were synthesized by the University of Pittsburgh Genomics and Proteomics Core Laboratories, and the mass and purity of each compound was confirmed by LC-MS. The kinase was preincubated with or without the peptides for 15 min, and the reaction was initiated by the addition of ATP (100 μM) and Tyr2 peptide substrate (1 μM). The kinase reaction was incubated 1 h, followed by addition of the development protease to cleave the unphosphorylated substrate. Coumarin and fluorescein fluorescence were measured 1 h later on a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M5 plate reader. Results are expressed as percent of maximum kinase activity relative to a stoichiometrically phosphorylated positive control peptide and negative control wells where no ATP is present.

Screening assays were performed with Src-YEEI (30 ng) in the presence of a 10-fold molar excess of the pFAK peptide (545 nM pFAK versus 54.5 nM Src-YEEI) or with Src-YEEI alone (125 ng; 227 nM). Each compound was assayed at a final concentration of 10 μM with carrier solvent (DMSO) at 2.5%. Src-YEEI was preincubated with the pFAK peptide for 15 min. Compounds were then added and the mixtures incubated for an additional 30 min before initiating the kinase reaction by the addition of substrate and ATP. The IC50 values for the hit compounds were determined over a concentration range of 3 nM to 30 μM, and the resulting concentration–response curves were best-fit by nonlinear regression analysis to obtain the IC50 values (GraphPad Prism). Results are expressed as percent inhibition, calculated relative to negative control wells without ATP and positive control wells without inhibitor (DMSO only).

Kinetic kinase assays

These studies used the fluorescence-based ADP Quest Assay (DiscoveRx), which monitors the production of ADP in kinase reactions over time (37). All kinase assays were performed in quadruplicate in black 384-well microplates (Corning # 3571), in a final assay volume of 50 μL/well at 25 °C. ATP stocks were prepared in 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.0, and the ATP concentration in each assay was held constant at 100 μM. The SFK substrate peptide, YIYGSFK (Anaspec) (38) was prepared in ADP Quest assay buffer (15 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 20 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 0.02% Tween-20, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/mL bovine γ-globulin). The substrate concentration in the assay was set to the Km value (162 μM). In kinase inhibition assays, the Src-YEEI concentration in the absence of the pFAK peptide was 40 ng/well (14.5 nM) and in the presence of the peptide was 15.6 ng/well (5.7 nM). Kinase reactions were initiated by the addition of ATP. Assay plates were read every 5 min for 3 h on a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M5 microplate reader. Results are expressed as percent of maximum kinase activity relative to the activity of the kinase in the absence of inhibitor. The mass and purity of inhibitors WH-4-124-2 and WH-4-023 were confirmed by LC-MS (>95%). WH-4-023 has been previously described as a potent inhibitor for c-Src and Lck (39).

Computational docking

The binding mode of the inhibitor WH-4-124-2 was modeled to the X-ray crystal structure of the Tyr416-dephosphorylated, imatinib-bound Lck kinase domain (PDB ID: 2PL0) by generating conformers of the compound using OMEGA2 (40) (OpenEye) with default settings. A pharmacophore alignment of each WH-4-124-2 conformer was then performed with the piperazine and aliphatic rings of imatinib in this Lck structure using Pharmer (41). The aligned conformers were energy-minimized using smina (42) with the default minimization parameters and fixed receptor protein. Poses of WH-4-124-2 that showed a low-energy score and a good structural alignment to the carbamate core of a related inhibitor (compound 43) bound in a crystal complex with phosphorylated Lck (PDB ID: 2OFU) (39) in a region with high structural similarity with dephosphorylated Lck were selected for refinement/minimization. Finally, the low-energy-minimized structure, which recovers most of the interactions present in both Lck co-crystal structures, was selected as the best model. The binding mode of WH-4-023 was modeled to the X-ray crystal structures of the Lck kinase domain in the DFG-in (PDB: 2OFU) (39) and DFG-out (PDB: 2PL0) (43) states through pharmacophore alignment and energy minimization.

Results and Discussion

Development of a screening assay for Src:FAK selective inhibitors

To screen for selective inhibitors of the c-Src:pFAK complex, we used a synthetic peptide based on the c-Src SH3/SH2 docking region from FAK (pFAK phosphopeptide; Figure 2) to activate recombinant, downregulated c-Src. Our goal was to model the conformation of active c-Src that results from interaction with FAK in focal adhesions. Previous studies have shown that this pFAK peptide binds to a tandem c-Src SH3-SH2 protein with low nanomolar affinity and is sufficient to activate c-Src via regulatory domain displacement in vitro (13).

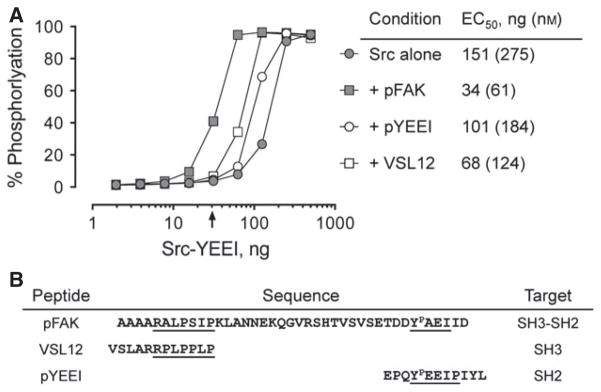

Figure 2.

Activation of Src-YEEI by SH3- and SH2-binding peptides. The activity of Src-YEEI was measured in the Z’Lyte in vitro kinase assay in the absence or presence of peptides that bind to the SH3 domain alone (VSL12), the SH2 domain alone (pYEEI), or to both (pFAK). Recombinant Src-YEEI was titrated into the assay over the range of 2-500 ng as shown, and peptides were added at a 10-fold molar excess at each kinase concentration. The concentration of Src-YEEI required to reach 50% maximal activation (EC50) for each condition is shown on the right. The arrow indicates the Src-YEEI concentration used for the library screen, where Src-YEEI activity is dependent on the pFAK peptide (30 ng kinase input; 54.5 nM). The sequences of the peptides are shown below the graph with the docking sites for the Src SH3 and SH2 domains indicated.

Before initiating the chemical library screen, we first established kinase assay conditions under which c-Src activity was wholly dependent upon binding to the pFAK peptide. The form of recombinant, downregulated c-Src used in these studies has a modified C-terminal tail in which the wild-type sequence, Y527QPGENL, is replaced with YEEI to create a high-affinity SH2-binding sequence. This modification allows the kinase, termed Src-YEEI, to undergo tail autophosphorylation, enabling expression and purification in the downregulated state (26).

We first measured purified Src-YEEI activity over a range of kinase concentrations in the absence or presence of the pFAK peptide, using the Z’Lyte kinase assay (44). As shown in Figure 2A, the extent of substrate phosphorylation increased in sigmoidal fashion as a function of input kinase concentration, with an EC50 value of 151 ng/well (275 nM) in the absence of peptide. When this experiment was repeated in the presence of the pFAK peptide, the activation curve was shifted markedly to the left, yielding an EC50 value of 34 ng/well (61 nM). This result is consistent with the interaction of the pFAK peptide with the Src-YEEI SH3 and SH2 domains, resulting in displacement of the regulatory apparatus from the back of the kinase domain and subsequent activation.

To provide additional evidence that dual engagement of the SH3 and SH2 domains is necessary for maximal activation of Src-YEEI in our assay, we examined the effect of peptides that bind individually to the SH3 domain (VSL12) or the SH2 domain (pYEEI) on kinase activity. The sequences of these peptides are presented in Figure 2B. Both of these peptides also activated Src-YEEI, but to a lesser extent than the pFAK peptide (Figure 2A). The pYEEI peptide, which binds only to the SH2 domain, resulted in an EC50 value for Src-YEEI activation of 101 ng/well (184 nM), while the VSL12 peptide, which exclusively engages the SH3 domain, yielded an EC50 value of 68 ng/well (124 nM). Both values are higher than that obtained with the pFAK peptide, supporting the idea that dual regulatory domain displacement results in maximal kinase activity.

Identification of inhibitors selective for Src-YEEI in complex with the pFAK peptide

For inhibitor screening, we chose a concentration of Src-YEEI that was dependent on the pFAK peptide for activity so as to model the kinase conformation induced by FAK binding. As indicated by the arrow in Figure 2A, Src-YEEI alone was inactive in the assay at 30 ng/well, while addition of the pFAK peptide resulted in 40% of maximal activation at this Src-YEEI concentration. This condition was therefore used for the library screen. We also identified a higher concentration of Src-YEEI alone (125 ng/well) with activity comparable to that of the Src-YEEI:pFAK peptide complex, as a basis of comparison. The ATP concentration was set to 100 μM, which is in excess of published Km values for c-Src (26,45–47) while the peptide substrate concentration was set to 1 μM. Using these assay conditions, we screened a kinase-biased small molecule library of 586 compounds for preferential inhibitors of Src-YEEI in the presence of the pFAK peptide compared with Src-YEEI alone. Most of the compounds in this library were designed to bind kinase domains in the so-called Type II mode and exploit specific ATP-site conformations to impart binding specificity (30,31). Compounds were screened at a final concentration of 10 μM, and the rank order of inhibitory potency for each compound against the Src-YEEI:pFAK peptide complex is presented in Figure 3A.

Figure 3.

Chemical library screen for selective inhibitors of pFAK-dependent Src-YEEI activity. A kinase-biased library of 586 compounds was screened for inhibitors of Src-YEEI activity in the presence of the pFAK peptide using the FRET-based Z’Lyte assay as described in the text. (A) Inhibitory activities of all 586 compounds are ranked by percent inhibition relative to the unphosphorylated substrate peptide control. Ninety-seven compounds inhibited kinase activity by at least 50% (dotted line). (B) A selectivity ratio was determined for compounds showing >50% inhibition of the Src-YEEI:pFAK complex in part A. This ratio was calculated as the percent inhibition of the Src-YEEI: pFAK complex divided by the percent inhibition observed with Src-YEEI alone. Twenty-four compounds exhibited a selectivity ratio >3 (dotted line). The hit compound WH-4-124-2 is indicated in each graph by a red dot, while the control compound WH-4-023 is indicated with a blue dot.

The 97 compounds that showed at least 50% inhibition of the Src-YEEI:pFAK complex at 10 μM were then assessed for inhibition of Src-YEEI alone. Results for each of these compounds were then ranked according to their selectivity ratios, defined as the percent inhibition of the Src-YEEI:pFAK peptide complex divided by the percent inhibition of Src-YEEI alone. Twenty-four compounds with a selectivity ratio >3 (Figure 3B) were selected for further evaluation in concentration–response experiments. Of these, four compounds reproducibly inhibited Src-YEEI in the presence of the pFAK peptide to a greater extent than Src-YEEI alone with selectivity ratios ranging from 5 to almost 20 (data not shown). However, the overall potency for three of these compounds was rather low, with only about 50% inhibition of the kinase:peptide complex at a concentration of 10 μM. For this reason, we did not follow up on these compounds. Instead, we focused on the aminopyrimidinyl carbamate designated WH-4-124-2 (see Figure 4A for structure) because it was the most potent inhibitor of Src-YEEI in the presence of the pFAK peptide. As shown in Figure 4A and Table 1, WH-4-124-2 inhibited the Src-YEEI:pFAK peptide complex with an IC50 value of 0.89 μM in the Z’Lyte assay, as compared to 4.95 μM for Src-YEEI alone.

Figure 4.

Selective inhibition of Src-YEEI by WH-4-124-2 in the presence of the pFAK peptide but not its structural analog, WH-4-023. WH-4-124-2 (A) and WH-4-023 (B) were assayed against Src-YEEI alone (gray circles) and the Src-YEEI:pFAK complex (black circles) over the range of inhibitor concentrations shown using the Z’Lyte end-point assay. All data points were measured in quadruplicate, and the values shown represent the mean ± SE. IC50 values were determined by nonlinear regression analysis and are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

IC50 values for kinase inhibitors WH-4-124-2 and WH-4-023 against Src-YEEI in the presence and absence of the pFAK peptide

| WH-4-124-2

|

WH-4-023

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z’Lyte | ADP Quest | Z’Lyte | ADP Quest | |

| Src-YEEI + pFAKa | 0.89 | 0.114 | 1.36 | 0.025 |

| Src-YEEI alonea | 4.95 | 0.531 | 1.28 | 0.019 |

| Selectivity ratiob | 5.56 | 4.82 | 0.94 | 0.76 |

IC50 values (μM) were generated in the Z’Lyte end-point assay used for the library screen and in the ADP Quest kinetic kinase assay for Src-YEEI in complex with the pFAK peptide versus Src-YEEI alone.

IC50 for inhibition of the Src-YEEI:pFAK peptide complex divided by the IC50 for inhibition of Src-YEEI alone.

WH-4-124-2 is a selective inhibitor of the Src-YEEI:pFAK complex

We next investigated the specific structural features of WH-4-124-2 responsible for its selectivity toward the Src-YEEI:pFAK complex. The compound WH-4-023, which is a substructure of WH-4-124-2 (Figure 4B), inhibited both the Src-YEEI:pFAK peptide complex and Src-YEEI alone by more than 70% in the screening assay (blue data point in Figure 3A). We therefore performed a concentration–response experiment with this compound and found that it inhibited Src-YEEI alone and in complex with the pFAK peptide with an IC50 value of about 1.3 μM (Figure 4B). This result strongly suggests that the methylpiperazinyl trifluoromethylbenzamide substituent present in WH-4-124-2 contributes to inhibitor selectivity.

We next investigated whether displacement of either the SH3 or SH2 domain alone was sufficient to cause the conformational rearrangement responsible for inhibitor selectivity. As shown in Figure 5, activation of Src-YEEI by displacement of either the SH3 domain (with the VSL12 peptide; see Figure 2B) or the SH2 domain (with the pYEEI peptide) both resulted in enhanced inhibition by WH-4-124-2. Interestingly, inhibition of VSL12-activated Src-YEEI (via SH3 domain displacement) was less pronounced than inhibition following activation by either the pFAK or pYEEI peptides. These findings suggest that SH3 displacement alone does not allow the kinase domain to adopt the conformation preferred by this inhibitor.

Figure 5.

Selective inhibition of Src-YEEI by WH-4-124-2 by the pFAK peptide involves displacement of both SH2-tail and SH3-linker interactions. (A) Src-YEEI alone or together with the SH2 peptide ligand pYEEI, the SH3 peptide ligand VSL12, or the pFAK peptide was assayed over the range of inhibitor concentrations shown using the Z’Lyte end-point assay. All data points were measured in quadruplicate, and the values shown represent the mean ± SE. (B) IC50 values were determined by nonlinear regression analysis and are shown in Table 1.

Selective inhibitor discovery and characterization described so far were performed using the Z’Lyte end-point kinase assay, which does not provide direct information about the effect of either the activator peptide or the inhibitors on the kinase reaction rate. We therefore turned to the ADP Quest assay, which measures the progress of the kinase reaction as the accumulation of ADP. We first measured Src-YEEI activity in the absence or presence of the pFAK peptide to establish conditions for testing the compounds (Figure 6A). As with the Z’Lyte assay, these initial experiments identified a Src-YEEI concentration dependent on the presence of the pFAK peptide for activity (15.6 ng/well). ADP production was barely detectable in the absence of the pFAK peptide at this Src-YEEI concentration, but increased to 1.0 pmol ADP produced/min in the presence of the pFAK peptide. Src-YEEI alone at 40 ng/well resulted in the same rate of 1.0 pmol ADP produced/min and was used for comparative purposes.

Figure 6.

WH-4-124-2 exhibits increased potency while maintaining selectivity in a kinetic kinase assay. (A) The activity of Src-YEEI was measured in the ADP Quest kinetic kinase assay in the absence (gray circles) or presence (black circles) of 30 μM pFAK peptide over the range of input kinase concentrations shown. Compounds WH-4-124-2 (B) and WH-4-023 (C) were assayed against Src-YEEI alone (gray circles) and the Src-YEEI: pFAK complex (black circles) in this assay over the range of inhibitor concentrations shown. Reaction rates at each compound concentration were measured in quadruplicate and are presented as the mean ± SE. IC50 values were determined by nonlinear regression analysis and are shown in Table 1.

Both WH-4-124-2 and WH-4-023 inhibited Src-YEEI activity in the ADP Quest assay in a concentration–dependent manner (Figure 6B, C and Table 1). WH-4-124-2 is more potent against Src-YEEI in complex with the pFAK peptide than Src-YEEI alone, with IC50 values of 114 versus 531 nM, respectively. By contrast, WH-4-023 inhibited Src-YEEI alone and in complex with the pFAK peptide with very similar potencies, yielding IC50 values of 19 and 25 nM, respectively (Figure 6C and Table 1). While the IC50 values generated for both inhibitors in the ADP Quest assay are lower than those generated in the Z’Lyte assay, the selectivity for the Src-YEEI:pFAK complex is the same in both. This difference in apparent potency is likely due to the different peptide substrates used as well as the assay types involved (end-point versus kinetic).

Docking studies are consistent with pFAK peptide binding inducing a DFG flip in the c-Src kinase domain that favors WH-4-124-2 binding

Data presented in the previous sections suggest that binding of pFAK to c-Src may induce a conformation of the kinase active site that is stabilized by WH-4-124-2 binding. One well-known determinant of kinase inhibitor specificity relates to the conformation of the highly conserved aspartate–phenylalanine–glycine (‘DFG’) motif at the N-terminal end of the activation loop in the kinase active site (48,49). In the active state, the aspartate in the DFG motif moves into the active site where it contributes to the co-ordination of ATP-Mg++. In the inactive state, however, this aspartate residue moves away from the active site while the phenylalanine side chain moves inward, resulting in the so-called DFG-out conformation. Previous structural studies have shown that inhibitors such as imatinib prefer the DFG-out conformation, which accounts in part for its selectivity toward the Abl kinase domain (48,50). Interestingly, imatinib has also been co-crystallized with both c-Src and Lck, where it binds to a similar DFG-out conformation (43,51). These observations led us to consider whether WH-4-124-2 may exhibit some of its selectivity by inhibiting the DFG-out state of Src-family kinase domains.

Comparison of the chemical structures of WH-4-124-2 and imatinib reveals significant overlap (Figure 7A), allowing us to align WH-4-124-2 with imatinib in the X-ray crystal structure of the Lck kinase domain. This Src-family kinase structure was chosen because all of its kinase domain features are resolved, including the activation loop and autophosphorylation site, which are missing from the c-Src structure with imatinib (51). Binding of imatinib to the kinase domains of both Lck and c-Src stabilizes the DFG-out conformation, similar to what is observed with the Abl kinase domain when bound to this drug (52). In Lck, however, the activation loop and tyrosine autophosphorylation site are extended outward (Figure 7B), whereas in Abl, the equivalent tyrosine residue is hydrogen-bonded to the catalytic aspartate (52). This comparison suggests that in Lck (and by analogy, c-Src), imatinib traps a ‘primed’ or intermediate state between the downregulated and fully active forms of the kinase domain.

Figure 7.

Computational docking of WH-4-124-2 to the X-ray crystal structure of the Lck kinase domain bound to imatinib. (A) Comparison of the structures of WH-4-124-2 and imatinib reveals a shared methylpiperazinylmethyl-N-phenylbenzamide backbone (red). (B) Close-up view of the Lck active site with WH-4-124-2 (carbon atoms in cyan) aligned to imatinib (carbon atoms in yellow). WH-4-124-2 was readily accommodated by this imatinib-binding conformation of the Lck kinase domain. In this structure, the N-terminal portion of the activation loop (blue) adopts the DFG-out conformation, with the autophosphorylation site (Y416) extending outward. The side chains of the catalytic aspartate and the gatekeeper residue (T338) are shown for reference. Docking model was produced using the X-ray crystal structure of the Src-family kinase Lck bound to imatinib (PDB: 2PL0). Residue numbering is based on the crystal structure of c-Src (PDB: 2SRC).

WH-4-124-2 was aligned with imatinib in the Lck kinase domain crystal structure using the docking routine smina (42) a modified version of AutoDock Vina (53) optimized for user-specified custom scoring functions (see Methods for details of the docking approach). WH-4-124-2 was readily accommodated by the crystal conformation of the imatinib-bound Lck active site. Remarkably, no structural rearrangement of the imatinib-bound Lck structure was necessary to obtain the final model presented in Figure 7B, supporting the idea that this inhibitor prefers the DFG-out conformation. A similar docking routine was also performed using the X-ray crystal structure of the c-Src kinase domain bound to imatinib (PDB: 2OIQ) (51). This analysis yielded an almost identical result, although the activation loop is not resolved in this structure (not shown). These docking models suggest that binding of the pFAK peptide and displacement of the SH3-SH2 regulatory subunits allow the kinase to adopt the DFG-out conformation, which in turn is trapped by WH-4-124-2. In contrast, attempts to dock WH-4-124-2 to the kinase domain of Lck in the active conformation (PDB ID: 3LCK) (54) were unsuccessful, resulting in steric clash (not shown). In the active structure, the Lck DFG motif is rotated inward, which is incompatible with compound binding.

Unlike WH-4-124-2, which selectively inhibits the Src-YEEI:pFAK peptide complex, compound WH-4-023 potently inhibited c-Src activity regardless of pFAK peptide binding. This observation suggests that WH-4-023 may inhibit both the DFG-out and DFG-in conformations of the kinase domain. Molecular docking studies support this idea. The 2-aminopyrimidine carbamate backbone in WH-4-023 closely resembles a similar ligand in an X-ray crystal structure of the Lck kinase domain in the DFG-in conformation (compound 43; PDB: 2OFU) (39). Docking of WH-4-023 to this structure recovered the same binding mode found for compound 43 in the co-crystal (Figure 8A). We then docked WH-4-023 in the same pocket of the DFG-out structure of the Lck kinase domain described above (PDB: 2PL0) (43). The binding orientations of WH-4-023 are very similar in the two models (Figure 8B) and match that of the closely related ligand (compound 43) in structure 2OFU. One minor difference between the two docking models involves the orientation of the WH-4-023 dimeth-oxyphenyl ring, which is rotated 180° in the DFG-out binding mode to accommodate the side chain of the DFG phenylalanine (Figure 8B, arrow). However, the very similar binding modes for WH-4-023 to both states of the Lck kinase domain may help to explain the almost identical potencies of this compound for c-Src in the presence and absence of the pFAK peptide.

Figure 8.

Computational docking of WH-4-023 to the X-ray crystal structures of the DFG-in and DFG-out conformations of the Lck kinase domain. (A) View of the Lck active site with WH-4-023 (carbons in green) aligned to the related 2-aminopyrimidine carbamate (compound 43; carbons in yellow) in the crystal structure of the Lck kinase domain in the DFG-in conformation (PDB: 2OFU). In the DFG-in state, the activation loop tyrosine is phosphorylated (pY416). (B) Crystal structure of the Lck kinase domain in the DFG-out conformation (PDB: 2PL0) accommodates WH-4-023 in the same binding pocket as in panel A, with the ligand dimethoxyphenyl moiety rotated to accommodate the phenylalanine side chain of the DFG motif (arrow). In both models, the activation loop is colored in blue with the side chains of the DFG motif, the catalytic aspartate and the gatekeeper residue (T338) shown. Residue numbering is based on the crystal structure of c-Src (PDB: 2SRC).

Docking studies presented above suggest that binding of the pFAK peptide to the SH3-SH2 region of Src allows the kinase domain to adopt the DFG-out conformation preferred by WH-4-124-2. However, kinase activation is associated with movement of the DFG motif into the active site, suggesting that preactivation of c-Src by incubation with ATP before inhibitor addition may interfere with WH-4-124-2 action. To test this idea experimentally, we performed a concentration–response experiment with WH-4-124-2 using Src-YEEI that was preincubated with ATP under conditions previously shown to result in stoichiometric autophosphorylation of the activation loop (26). As shown in Figure 9, autophosphorylation of Src-YEEI did not appreciably influence inhibition by this compound compared to a matched control preincubated under identical conditions in the absence of ATP. Addition of the pFAK peptide to the assay enhanced inhibitor sensitivity as observed previously, regardless of ATP preincubation, providing further evidence that peptide engagement of the regulatory domains is largely responsible for the observed enhancement in inhibitor action.

Figure 9.

Preincubation with ATP does not affect WH-4-124-2 potency for Src-YEEI. Src-YEEI was preincubated in the presence (top panel) or absence (bottom panel) of ATP (at the Km) for 3 h at 25 °C to induce autophosphorylation of Tyr416 in the activation loop as described previously (26). Each kinase preparation was then assayed for sensitivity to WH-4-124-2 in the presence or absence of the pFAK peptide using the Z’Lyte end-point assay. All data points were measured in quadruplicate, and the values shown represent the mean ± SE.

Previous studies have established that the Abl kinase inhibitor imatinib derives its specificity, in part, from its preference for the DFG-out conformation of the Abl kinase domain (48). Docking studies presented in Figure 7 suggest that pFAK peptide binding may induce the DFG-out state of Src, because the preferred docking pose for WH-4-124-2 requires this kinase domain conformation. Taken together, these observations suggest that pFAK peptide binding may also enhance the sensitivity of Src to inhibition by imatinib. To test this idea, we performed concentration–response experiments with imatinib and Src-YEEI in the presence and absence of pFAK as before. As shown in Figure 10, imatinib exhibited very little activity against Src-YEEI alone, consistent with literature reports that imatinib is a very poor Src inhibitor (51). Interestingly, when the experiment was repeated with the Src:pFAK peptide complex, partial inhibition was observed, although only at very high imatinib concentrations (~25% inhibition at 100 μM). This result suggests that the additional methylphenylpiperazine and/or dimethoxybenzyl moieties present in WH-4-124-2 account for its much greater potency against the pFAK:Src complex relative to imatinib (see Figure 7). Nevertheless, these findings support the idea that pFAK peptide binding induces the DFG-out conformation. Interestingly, the presence of the pFAK peptide also resulted in a modest increase in the sensitivity of Src to inhibition by dasatinib (~4 fold; Figure 10), despite its classification as a ‘Type I’ kinase inhibitor (i.e., one that does not sense differences in the position of the DFG motif) (30,55). This observation suggests that SH3-SH2 engagement by the pFAK peptide may induce unique conformational changes in the active site in addition to influencing the status of the DFG motif.

Figure 10.

Inhibition of Src-YEEI by imatinib and dasatinib is influenced by pFAK peptide binding. Src-YEEI alone and the Src-YEEI:pFAK complex were assayed over the range of dasatinib and imatinib concentrations indicated using the Z’Lyte end-point assay. All data points were measured in quadruplicate, and the values shown represent the mean ± SE.

Summary and Conclusions

In this study, we describe a screening strategy that enables discovery of c-Src inhibitors that appear to prefer a specific active site conformation. SFKs are involved in a wide variety of cellular signaling pathways and most cells express multiple members of the Src kinase family, making the search for isoform- and pathway-selective inhibitors difficult. Rather than focusing on the Src kinase domain in isolation, we developed an assay method that models a disease-specific conformation of near-full-length c-Src that is induced by interaction with FAK. Using a synthetic tyrosine phosphopeptide containing the natural FAK sequence known to bind to the tandem SH3/SH2 unit of c-Src, we first identified screening assay conditions where Src-YEEI activity was dependent on the presence of the pFAK peptide. Using pFAK-activated Src-YEEI, we then screened a small library of kinase-biased inhibitors and identified WH-4-124-2, an aminopyrimidinyl carbamate with enhanced potency for Src-YEEI in the presence of the pFAK peptide. This compound exhibited fivefold greater potency for the Src-pFAK peptide complex relative to Src-YEEI alone in both end-point and kinetic kinase assays. Interestingly, a smaller structural analog of WH-4-124-2 showed no preference, supporting the idea that WH-4-124-2 stabilizes a specific conformation of the kinase active site that is induced by interaction with the pFAK peptide.

Docking studies with WH-4-124-2 and the imatinib-bound crystal structures of two Src-family kinase domains (c-Src and Lck) suggest that binding to the pFAK peptide may allow a unique DFG-out conformation that is preferentially inhibited by this compound. In this conformation, the αC-helices of both kinase domains are rotated inward, allowing the formation of the conserved lysine to glutamate salt bridges. The DFG motif at the distal end of the activation loop in each kinase is rotated outward, in the same manner originally observed for imatinib binding to the Abl kinase domain (48). However, in the Lck structure, the autophosphorylation site is extended outward, although the tyrosine is not phosphorylated (this region is not resolved in the c-Src kinase domain structure with imatinib). Using the structural overlap with imatinib as a starting point, WH-4-124-2 was readily docked into this unique Lck kinase domain conformation. This observation with Lck suggests that pFAK peptide binding may induce a similar kinase domain conformation in c-Src, thereby accounting for preferential inhibition by WH-4-124-2 in the presence of the pFAK peptide. Whether or not binding to full-length FAK results in similar changes to the c-Src active site in a cellular context will require further investigation. Nevertheless, these studies support the more general concept that unique disease-state-specific conformations of Src-family kinases exist in cells that may be amenable to selective inhibition with active site inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA169962 to T.E.S. and GM097082 to C.J.C. J.A.M. was supported by the Pittsburgh AIDS Research Training Program (NIH T32 AI065380).

References

- 1.Brown MT, Cooper JA. Regulation, substrates, and functions of Src. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1287:121–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(96)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resh MD. Myristylation and palmitylation of Src family members: the fats of the matter. Cell. 1994;76:411–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boggon TJ, Eck MJ. Structure and regulation of Src family kinases. Oncogene. 2004;23:7918–7927. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chong YP, Ia KK, Mulhern TD, Cheng HC. Endogenous and synthetic inhibitors of the Src-family protein tyrosine kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1754:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong YP, Chan AS, Chan KC, Williamson NA, Lerner EC, Smithgall TE, Bjorge JD, Fujita DJ, Purcell AW, Scholz G, Mulhern TD, Cheng HC. C-terminal Src kinase-homologous kinase (CHK), a unique inhibitor inactivating multiple active conformations of Src family tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32988–32999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu W, Doshi A, Lei M, Eck MJ, Harrison SC. Crystal structures of c-Src reveal features of its autoin-hibitory mechanism. Mol Cell. 1999;3:629–638. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D, Esselman WJ, Cole PA. Substrate conformational restriction and CD45-catalyzed dephosphorylation of tail tyrosine-phosphorylated Src protein. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40428–40433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lerner EC, Smithgall TE. SH3-dependent stimulation of Src-family kinase autophosphorylation without tail release from the SH2 domain in vivo. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:365–369. doi: 10.1038/nsb782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lerner EC, Trible RP, Schiavone AP, Hochrein JM, Engen JR, Smithgall TE. Activation of the Src family kinase Hck without SH3-linker release. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40832–40837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508782200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briggs SD, Sharkey M, Stevenson M, Smithgall TE. SH3-mediated Hck tyrosine kinase activation and fibroblast transformation by the Nef protein of HIV-1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17899–17902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moarefi I, LaFevre-Bernt M, Sicheri F, Huse M, Lee C-H, Kuriyan J, Miller WT. Activation of the Src-family tyrosine kinase Hck by SH3 domain displacement. Nature. 1997;385:650–653. doi: 10.1038/385650a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamoto T, Sakai R, Ozawa K, Yazaki Y, Harai H. Direct binding of C-terminal region of p130Cas to SH2 and SH3 domains of Src kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8959–8965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas JW, Ellis B, Boerner RJ, Knight WB, White GC, Schaller MD. SH2- and SH3-mediated interactions between focal adhesion kinase and Src. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:577–583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi I, Vuori K, Liddington RC. The focal adhesion targeting (FAT) region of focal adhesion kinase is a four-helix bundle that binds paxillin. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nsb755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arold ST, Hoellerer MK, Noble ME. The structural basis of localization and signaling by the focal adhesion targeting domain. Structure. 2002;10:319–327. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00717-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lietha D, Cai X, Ceccarelli DF, Li Y, Schaller MD, Eck MJ. Structural basis for the autoinhibition of focal adhesion kinase. Cell. 2007;129:1177–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao X, Guan JL. Focal adhesion kinase and its signaling pathways in cell migration and angiogenesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63:610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klinghoffer RA, Sachsenmaier C, Cooper JA, Soriano P. Src family kinases are required for integrin but not PDGFR signal transduction. EMBO J. 1999;18:2459–2471. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilic D, Furuta Y, Kanazawa S, Takeda N, Sobue K, Nakatsuji N, Nomura S, Fujimoto J, Okada M, Yamamoto T. Reduced cell motility and enhanced focal adhesion contact formation in cells from FAK-deficient mice. Nature. 1995;377:539–544. doi: 10.1038/377539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao J, Guan JL. Signal transduction by focal adhesion kinase in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:35–49. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim LC, Song L, Haura EB. Src kinases as therapeutic targets for cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:587–595. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang S, Yu D. Targeting Src family kinases in anti-cancer therapies: turning promise into triumph. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLean GW, Carragher NO, Avizienyte E, Evans J, Brunton VG, Frame MC. The role of focal-adhesion kinase in cancer – a new therapeutic opportunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:505–515. doi: 10.1038/nrc1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lieu C, Kopetz S. The SRC family of protein tyrosine kinases: a new and promising target for colorectal cancer therapy. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2010;9:89–94. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2010.n.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puls LN, Eadens M, Messersmith W. Current status of SRC inhibitors in solid tumor malignancies. Oncologist. 2011;16:566–578. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moroco JA, Craigo JK, Iacob RE, Wales TE, Engen JR, Smithgall TE. Differential sensitivity of Src-family kinases to activation by SH3 domain displacement. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e105629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trible RP, Emert-Sedlak L, Smithgall TE. HIV-1 Nef selectively activates SRC family kinases HCK, LYN, and c-SRC through direct SH3 domain interaction. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27029–27038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601128200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seeliger MA, Young M, Henderson MN, Pellicena P, King DS, Falick AM, Kuriyan J. High yield bacterial expression of active c-Abl and c-Src tyrosine kinases. Protein Sci. 2005;14:3135–3139. doi: 10.1110/ps.051750905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iacob RE, Pene-Dumitrescu T, Zhang J, Gray NS, Smithgall TE, Engen JR. Conformational disturbance in Abl kinase upon mutation and deregulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1386–1391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811912106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y, Gray NS. Rational design of inhibitors that bind to inactive kinase conformations. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:358–364. doi: 10.1038/nchembio799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okram B, Nagle A, Adrian FJ, Lee C, Ren P, Wang X, Sim T, Xie Y, Wang X, Xia G, Spraggon G, Warmuth M, Liu Y, Gray NS. A general strategy for creating “inactive-conformation” abl inhibitors. Chem Biol. 2006;13:779–786. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodems SM, Hamman BD, Lin C, Zhao J, Shah S, Heidary D, Makings L, Stack JH, Pollok BA. A FRET-based assay platform for ultra-high density drug screening of protein kinases and phosphatases. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2002;1:9–19. doi: 10.1089/154065802761001266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hellwig S, Miduturu CV, Kanda S, Zhang J, Filippakopoulos P, Salah E, Deng X, Choi HG, Zhou W, Hur W, Knapp S, Gray NS, Smithgall TE. Small-molecule inhibitors of the c-Fes protein-tyrosine kinase. Chem Biol. 2012;19:529–540. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emert-Sedlak L, Kodama T, Lerner EC, Dai W, Foster C, Day BW, Lazo JS, Smithgall TE. Chemical library screens targeting an HIV-1 accessory factor/host cell kinase complex identify novel antiretroviral compounds. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:939–947. doi: 10.1021/cb900195c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eck MJ, Shoelson SE, Harrison SC. Recognition of a high-affinity phosphotyrosyl peptide by the Src homology-2 domain of p56lck. Nature. 1993;362:87–91. doi: 10.1038/362087a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rickles RJ, Botfield MC, Zhou XM, Henry PA, Brugge JS, Zoller MJ. Phage display selection of ligand residues important for Src homology 3 domain binding specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10909–10913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charter NW, Kauffman L, Singh R, Eglen RM. A generic, homogenous method for measuring kinase and inhibitor activity via adenosine 5′-diphosphate accumulation. J Biomol Screen. 2006;11:390–399. doi: 10.1177/1087057106286829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lam KS, Wu J, Lou Q. Identification and characterization of a novel synthetic peptide substrate specific for Src-family protein tyrosine kinases. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1995;45:587–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1995.tb01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin MW, Newcomb J, Nunes JJ, McGowan DC, Armistead DM, Boucher C, Buchanan JL, et al. Novel 2-aminopyrimidine carbamates as potent and orally active inhibitors of Lck: synthesis, SAR, and in vivo antiinflammatory activity. J Med Chem. 2006;49:4981–4991. doi: 10.1021/jm060435i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hawkins PC, Skillman AG, Warren GL, Ellingson BA, Stahl MT. Conformer generation with OMEGA: algorithm and validation using high quality structures from the Protein Databank and Cambridge Structural Database. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50:572–584. doi: 10.1021/ci100031x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koes DR, Camacho CJ. ZINCPharmer: pharmacophore search of the ZINC database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W409–W414. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koes DR, Baumgartner MP, Camacho CJ. Lessons learned in empirical scoring with smina from the CSAR 2011 benchmarking exercise. J Chem Inf Model. 2013;53:1893–1904. doi: 10.1021/ci300604z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobs MD, Caron PR, Hare BJ. Classifying protein kinase structures guides use of ligand-selectivity profiles to predict inactive conformations: structure of lck/imatinib complex. Proteins. 2008;70:1451–1460. doi: 10.1002/prot.21633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emert-Sedlak LA, Narute P, Shu ST, Poe JA, Shi H, Yanamala N, Alvarado JJ, Lazo JS, Yeh JI, Johnston PA, Smithgall TE. Effector kinase coupling enables high-throughput screens for direct HIV-1 Nef antagonists with antiretroviral activity. Chem Biol. 2013;20:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boerner RJ, Barker SC, Knight WB. Kinetic mechanisms of the forward and reverse pp60c-src tyrosine kinase reactions. Biochemistry. 1995;34:16419–16423. doi: 10.1021/bi00050a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barker SC, Kassel DB, Weigl D, Huang X, Luther MA, Knight WB. Characterization of pp60c-src tyrosine kinase activities using a continuous assay: autoactivation of the enzyme is an intermolecular autophosphorylation process. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14843–14851. doi: 10.1021/bi00045a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knight ZA, Shokat KM. Features of selective kinase inhibitors. Chem Biol. 2005;12:621–637. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schindler T, Bornmann W, Pellicena P, Miller WT, Clarkson B, Kuriyan J. Structural mechanism for STI-571 inhibition of abelson tyrosine kinase. Science. 2000;289:1938–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5486.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Treiber DK, Shah NP. Ins and outs of kinase DFG motifs. Chem Biol. 2013;20:745–746. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagar B, Bornmann WG, Pellicena P, Schindler T, Veach DR, Miller WT, Clarkson B, Kuriyan J. Crystal structures of the kinase domain of c-Abl in complex with the small molecule inhibitors PD173955 and imatinib (STI-571) Cancer Res. 2002;62:4236–4243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seeliger MA, Nagar B, Frank F, Cao X, Henderson MN, Kuriyan J. c-Src binds to the cancer drug imatinib with an inactive Abl/c-Kit conformation and a distributed thermodynamic penalty. Structure. 2007;15:299–311. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Panjarian S, Iacob RE, Chen S, Engen JR, Smithgall TE. Structure and dynamic regulation of Abl kinases. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:5443–5450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.438382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamaguchi H, Hendrickson WA. Structural basis for activation of human lymphocyte kinase Lck upon tyrosine phosphorylation. Nature. 1996;384:484–489. doi: 10.1038/384484a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tokarski JS, Newitt JA, Chang CY, Cheng JD, Wittekind M, Kiefer SE, Kish K, Lee FY, Borzillerri R, Lombardo LJ, Xie D, Zhang Y, Klei HE. The structure of Dasatinib (BMS-354825) bound to activated ABL kinase domain elucidates its inhibitory activity against imatinib-resistant ABL mutants. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5790–5797. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]