Abstract

Objective:

To examine the effect of selenium supplementation on CD4+ T-cell counts, viral suppression, and time to antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation in ART-naive HIV-infected patients in Rwanda.

Methods:

A multicenter, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial was conducted. Eligible patients were HIV-infected adults (≥21 years) who had a CD4+ cell count between 400 and 650 cells/μl (ART eligibility was ≤350 cells/μl throughout the trial), and were willing to practice barrier methods of birth control. Patients were randomized to receive once-daily 200 μg selenium tablets or identical placebo. They were followed for 24 months with assessments every 6 months. Declines in CD4+ cell counts were modeled using linear regressions with generalized estimating equations and effect modification, and the composite outcome (ART eligible or ART initiation) using Cox proportional-hazards regression, both conducted with intention to treat.

Results:

Of the 300 participants, 149 received selenium, 202 (67%) were women, and median age was 33.5 years. The rate of CD4+ depletion was reduced by 43.8% [95% confidence interval (CI) 7.8–79.8% decrease] in the treatment arm – from mean 3.97 cells/μl per month to mean 2.23 cells/μl per month. We observed 96 composite outcome events – 45 (47%) in the treatment arm. We found no treatment effect for the composite outcome (hazard ratio 1.00, 95% CI 0.66–1.54) or viral suppression (odds ratio 1.18, 95% CI 0.71–1.94). The trial was underpowered for the composite outcome due to a lower-than-anticipated event rate. Adverse events were comparable throughout.

Conclusions:

This randomized clinical trial demonstrated that 24-month selenium supplementation significantly reduces the rate of CD4+ cell count decline among ART-naive patients.

Keywords: CD4+ cells, HIV/AIDS, randomized clinical trial, selenium

Introduction

HIV infection compromises the nutritional status of the infected individuals, and poor nutritional status can accelerate progression of the disease [1]. The relationship between immune function and nutritional supplementation has been well described [2–5]. Studies have reported high rates of nutrient deficiencies early in the course of HIV infection [6–8].

Among HIV-infected persons not receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART), observational studies have shown that low or deficient serum concentrations of several micronutrients, including the trace mineral selenium, are associated with low CD4+ T-cell counts, advanced HIV-related diseases, faster disease progression, or HIV-related mortality [9–23]. Selenium is incorporated into a number of biologically active selenoproteins and is an essential element of glutathione peroxide (GPX), which plays an important role in endogenous antioxidant defense [24,25]. Selenium is also an essential factor in maintaining host immune competence, and it has been shown that optimal levels decrease the host's susceptibility to viral pathogenesis [26–30]. Selenium deficiency, as indicated by low plasma selenium concentrations, is common in HIV-infected individuals [31,32], particularly in areas of the world with low selenium levels in the soil, as is true in many regions of sub-Saharan Africa [33–35].

Evidence of the effect of selenium supplementation from clinical trials is limited in both developed and developing countries. Three randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have been conducted to assess the individual association of selenium supplementation on HIV viral load and CD4+ T-cell count [36–38]. The first trial, conducted in Miami by Hurwitz et al.[37], found that selenium supplementation of 200 μg daily significantly suppressed the progression of HIV viral burden and indirectly improved CD4+ T-cell count after 9 months of treatment. The second trial, conducted in Tanzania by Kupka et al.[38], found that selenium supplementation of 200 μg daily provided to HIV-infected pregnant women before and after pregnancy (between 12 and 27 weeks of gestation and 6 months after birth) had no significant effect on HIV viral load or CD4+ T-cell count, but did significantly lower the risk of infant death. A third trial, a factorial design by Baum et al.[36] in Botswana, found no significant effect of selenium supplementation on the rate of depletion to 200 cells/μl among patients starting with a CD4+ T-cell count above 350 cells/μl. The authors did, however, find a significant event rate decrease when combined with multivitamins [36].

It is important to recognize the inherent differences in their design, setting, and populations of these trials when drawing inferences. Additional evidence from other settings and populations is required to more accurately determine the effect of selenium supplementation on HIV progression in HIV-infected individuals. Therefore, we conducted an RCT to examine the effect of selenium supplementation on CD4+ T-cell counts, viral suppression, and time to ART initiation in HIV-infected patients who are not yet on ART. We conducted our trial in Rwanda.

Methods

The present study is a 24-month, multicenter, patient and provider-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial, involving 300 pre-ART HIV-infected patients in Rwanda. We a priori calculated our sample size by assuming a 20% reduction in CD4+ T-cell count depletion. This trial has been registered with ClinicalTrials.gov under the registration number NCT01327755.

Patients were recruited at two health facilities that offer care and treatment for HIV/AIDS patients in Rwanda. These facilities were chosen due to the feasibility of recruiting all patients within a short period and the feasibility of coordination. Patient eligibility was restricted to: HIV-infected adults (21 years of age and older at study enrollment), who were not yet ART-eligible based on Rwanda guidelines for ART initiation, had a CD4+ T-cell count between 400 and 650 cells/μl, were willing to practice barrier methods of birth control at all times, and be able to provide written informed consent. The CD4+ cell count at baseline was considerably above the Rwanda guidelines for initiation of ART (≥350 cells/μl as of 2012). Eligible patients were identified from pre-ART registers. Participants were enrolled and followed for 2 years. Study assessments occurred at baseline, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months.

Patients were excluded if they intended on transferring out of the clinic catchment area before the study ended and/or if they were scheduled to start ART. Patients with psychiatric health concerns and pregnant women were also excluded.

Randomization

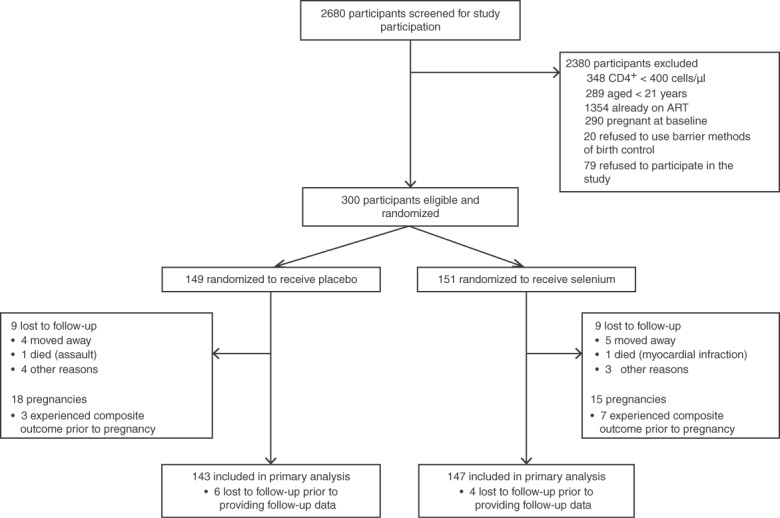

The randomization flowchart is shown in Fig. 1. Participants were randomized using a simple randomized block design to receive either selenium or an identically appearing placebo to be taken once daily for 24 months. The research department of the treatment supplier prepared the randomization schedule. Study participants were identified by unique study identification numbers and were assigned a specific allocation number. An unblinded list was provided to the treatment provider and to the independent statistician for the drug safety monitoring board.

Fig. 1.

Randomization flowchart.

Intervention

The trial intervention consisted of once-daily tablets containing 200 μg of selenium in the form of selenomethionine containing selenium yeast. The control arm received an identical placebo. To ensure optimal adherence, participants received adherence counseling at baseline and when picking up refills on a monthly basis. Additional adherence counseling was provided to patients who had sub-optimal adherence.

The Rwandan Ministry of Health recommends the use of cotrimoxazole – a sulfonamide antibiotic combination of trimethoprium and sulfamethoxazole used for the treatment of a variety of bacterial infections – for all HIV-infected patients. Therefore, all participants also received cotrimoxazole, irrespective of experimental assignment. Participants who did not return to the clinic as scheduled were followed up at home and received optimal adherence counseling.

Outcomes and study measures

The primary outcome measures for this study was change in CD4+ T-cell counts, and a composite of CD4+ T-cell depletion to 350 cells/μl (as confirmed by two consecutive measures), or start of ART, or the emergence of a documented CDC+-defined AIDS-defining illness. For analyses of the CD4+ T-cell count changes, patients were censored after ART initiation. Women who initiated ART through prevention of mother-to-child transmission programs prior to reaching other endpoints the composite outcome were censored at time of pregnancy because pregnancy is a mechanism by which ART is initiated independent of immunological failure. Secondary outcomes included: viral suppression; mortality; and adverse events. This study used the standard level of expedited adverse event reporting as defined in the Division of AIDS (DAIDS) of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Manual for Expedited Reporting of Adverse Events (Version 2.0, January 2010). Adverse event follow-up was reported on a standardized form during the protocol-defined reporting period. After the end of the protocol-defined adverse event-reporting period, sites were asked to report serious, unexpected, clinical suspected adverse drug reactions or if the study site staff becomes aware of the event on a passive basis (e.g. from publicly available information).

Trained nurses used structured questionnaires to collect data on patient demographics at baseline. Additionally, at baseline and at each follow-up visit, a questionnaire was used to collect information on psychosocial factors, access to care and treatment, attitudes towards and experiences with the supplementation, quality of life, self-efficacy, nutrition, opportunistic infections, and adherence to the study protocol. The questionnaire was available in both English and Kinyarwanda. Nurses also collected clinical data at baseline and at each follow-up visit, including information on height, weight, and blood.

Analysis

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were tabulated and compared using Fisher's exact test for dichotomous outcomes and Wilcoxon's rank-sum test for continuous outcomes. Statistical significance was assessed at the two-sided 5% level unless otherwise indicated. All analyses were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) approach using the randomized treatment assignment. All available data were used and missing data were removed.

To examine the effect of selenium supplementation on CD4+ T-cell decay, we used linear regression to model change from baseline (i.e. all patients were assigned a change of 0 at baseline). The model included both time in study and treatment group, with an effect modification on time-by-treatment group. Generalized estimating equations (GEEs) were used to account for the repeated-measures nature of the data. Assumptions for linear regression, including homogeneity and normality of residuals, were assessed graphically and met.

Both time-to-event analyses and simpler contingency table analyses were used to determine whether selenium supplementation could delay the initiation of ART. Survival analysis was carried out by way of Cox proportional-hazards and Kaplan–Meier curves. Only two models were considered. The first was a simple model by which the only explanatory variable was treatment, and the second was an explanatory model with the addition of self-reported adherence to treatment (measured as all pills taken). As self-reported adherence was measured over time, we used it as a time-varying covariate. Moreover, we used baseline CD4+, age, sex, viral load, and other measures of adherence to generate multiple imputations to overcome the missingness in the adherence. These analyses were then repeated for unadjusted events (a single CD4+ cell count event). All conditions for survival analysis were verified using tests based on the Schoenfeld residuals and all assumptions were met.

For this secondary outcome of viral load, we considered observed suppression as a measured viral load less than 20 copies/μl. Missing viral loads were considered ‘not observed as suppressed’ (missing equals failure). Viral loads were measured at three time points: baseline, 12 months, and 24 months. Given that there were only two follow-up points, logistic regression was favored over survival analysis. As such, we used GEEs to account for repeated measurements on the same individual. Finally, we removed observation following ART initiation, as this would clearly interfere with the effects of selenium supplementation on viral suppression. Two models were fit – one with only treatment as a predictor and the other with time of measurement.

All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (Cary, North Carolina, USA) and in R version 3.0.2 (Vienna, Austria).

Ethics

The present trial received approval from the institutional review boards of the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine and Wilfred Laurier University in Canada, and the National Ethics Committee (NEC) in Rwanda.

Results

Between September 2010 and January 2011, 300 patients were identified as eligible and randomized in this study. The study was conducted between January 2011 and June 2014 (24 months follow-up). Figure 1 shows the randomization, loss to follow-up, and censoring due to pregnancy over the study period. Selenium supplements were provided to 151 participants. Over the 24-month study period, 18 patients were lost to follow-up – nine within 6 months of study initiation, four more between 6 and 12 months into the study, three more in the next 6-month period, and finally two in the final 6 months. Reasons for loss to follow-up included accidental death, moving outside the study area, and unknown. The loss to follow-up counts did not include women who became pregnant and initiated ART through prevention of mother-to-child transmission programs. Pregnancy was nonetheless used as a censoring mechanism. Only two deaths were experienced, one in each arm, and neither appeared to be treatment-related.

Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of the study participants. There were 202 (67%) women, and the median age among participants was 33.5 years. The median baseline CD4+ cell count was 540 cells/μl with an interquartile range (IQR) from 468 to 627 cells/μl. The base 10 logarithm of viral load at baseline was 3.87 (IQR 3.15–4.45). In total, 84 (28%) patients reported not using barrier methods of birth control, which explains the 33 pregnancies observed over the 24-month study period. The duration of follow-up was 24 months for all but 19 patients.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and risk factors.

| Variable | Values | Total | Active count (%) or median (IQR) | Placebo count (%) or median (IQR) | P value |

| Sex | Male | 98 | 44 (29.1%) | 54 (36.2%) | 0.151 |

| Female | 202 | 107 (70.9%) | 95 (63.8%) | ||

| Age | 300 | 33.0 (28.0–39.0) | 35.0 (28.0–41.0) | 0.418 | |

| Marital status | Married or living with partner | 180 | 90 (60.8%) | 90 (60.4%) | 0.916 |

| Single | 26 | 15 (10.1%) | 11 (7.4%) | ||

| Widowed | 32 | 15 (10.1%) | 17 (11.4%) | ||

| Separated | 41 | 19 (12.8%) | 22 (14.8%) | ||

| Divorced | 18 | 9 (6.1%) | 9 (6%) | ||

| Employment | No | 132 | 65 (43.3%) | 67 (45.3%) | 0.585 |

| Yes | 165 | 84 (56%) | 81 (54.7%) | ||

| Refused | 1 | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| BMI at baseline | 266 | 21.5 (19.8–23.7) | 21.6 (20.0–24.3) | 0.379 | |

| CD4+ at baseline | 300 | 552 (470–636) | 527 (465–610) | 0.126 | |

| Viral load (log of) | 268 | 3.8 (3.0–4.5) | 3.9 (3.3–4.4) | 0.324 | |

| Has had sex in past month | No | 110 | 50 (33.3%) | 60 (40.3%) | 0.214 |

| Yes | 189 | 100 (66.7%) | 89 (59.7%) | ||

| Number of partners in past 30 days | NA (skipped) | 110 | 50 (33.3%) | 60 (40.5%) | 0.390 |

| 1 | 185 | 98 (65.3%) | 87 (58.8%) | ||

| 2 | 3 | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (0.7%) | ||

| Condom use in past 30 days | NA (skipped) | 110 | 50 (33.3%) | 60 (40.5%) | 0.233 |

| Always | 104 | 59 (39.3%) | 45 (30.4%) | ||

| Sometimes | 30 | 12 (8%) | 18 (12.2%) | ||

| Never | 54 | 29 (19.3%) | 25 (16.9%) |

IQR, interquartile range; NA, not available.

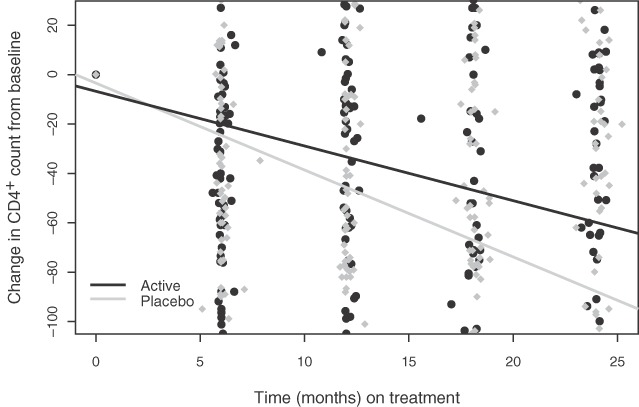

Changes in CD4+ T-cell counts were heterogeneous, with a SD of 120.3 cells/μl. Table 2 summarizes the linear regression with GEEs used to model change in CD4+ according to the treatment group. The average rate of CD4+ decline among patients using placebo was 3.97 cells/μl per month [95% confidence interval (CI) 3.03, 4.91]. The rate of CD4+ decline was reduced by 43.8% (95% CI 7.8–79.8) among patients using selenium supplementation. Figure 2 presents the estimated regression lines for each treatment group and suggests a difference of approximately 40 cells in decline at the end of the study period in favor of the treatment group over the placebo group.

Table 2.

Linear regression with generalized estimating equations.

| Variable | Average CD4+ change (95% confidence interval) | P value |

| Treatment | ||

| Active vs. placebo | −4.37 (−13.78, 5.04) | 0.363 |

| Time (per month) | −3.97 (−4.91, −3.03) | <0.001 |

| Time adjustment | ||

| Active vs. placebo | 1.74 (0.31, 3.17) | 0.017 |

Fig. 2.

Rate of CD4+ T-cell count decline across treatment groups.

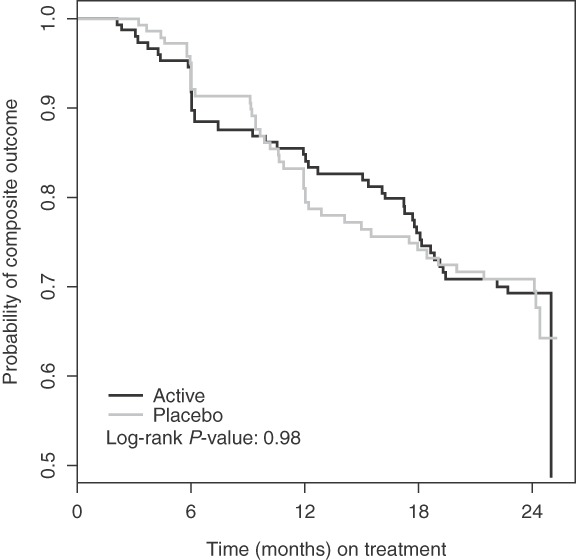

For the composite endpoint, a total of 86 events were observed after censoring for pregnancy (Table 3). None of the outcomes were an AIDS-defining illness. Most were CD4+ cell count depletion to below 350 cells/μl. Slightly more events occurred in the treatment group (51.2%), leading to a Fisher's exact P value of 0.899. When the definition of the composite outcome was relaxed to single measurement below 350 cells/μl, to account for missing second CD4+ measurements, a total of 115 composite outcomes were observed and 52 (45.2%) occurred in the selenium group. However, this comparison was also not statistically significant, with a Fisher's exact P value of 0.192. Figure 3 shows the Kaplan–Meier estimates for reaching the composite endpoint. Table 4 shows the results of the Cox proportional-hazards regressions. In the analysis using the two consecutive low CD4+ measurements in the composite outcome, the hazard ratio comparing the treatment group to the placebo group was 1.00 (95% CI 0.66–1.53). The result was consistent when accounting for adherence. The sensitivity analysis using a relaxed definition for the CD4+ event led to similar results, but with a lower estimate hazard ratio (0.93) and a larger hazard ratio for being nonadherent.

Table 3.

Contingency tables for composite outcome.

| Treatment | Total | No | Yes | P value |

| Composite outcome | ||||

| Active | 151 | 107 (50%) | 44 (51.2%) | 0.899 |

| Placebo | 149 | 107 (50%) | 42 (48.8%) | |

| Total (n) | 300 | 214 | 86 | |

| Use only a single CD4+ measurement below 350 as event | ||||

| Active | 151 | 99 (53.5%) | 52 (45.2%) | 0.192 |

| Placebo | 149 | 86 (46.5%) | 63 (54.8%) | |

| Total (n) | 300 | 185 | 115 | |

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier plot of time to composite outcome results.

Table 4.

Survival analysis for the composite outcome.

| Variable | Protocol data hazard ratio (95% CI) | Unadjusted dataa hazard ratio (95% CI) |

| Simple model | ||

| Active vs. placebo | 1.00 (0.66–1.53) | 0.93 (0.66–1.31) |

| Adjusted model | ||

| Active vs. placebo | 1.00 (0.66–1.54) | 0.94 (0.66–1.33) |

| Less-adherent vs. adherent | 1.17 (0.70–1.96) | 1.31 (0.85–2.02) |

CI, confidence interval.

This represents a sensitivity analysis by which a CD4+ event only required a single CD4+ below 350 cells/μl.

For the secondary outcome of viral suppression, the effect of treatment in the unadjusted model was an odds ratio (OR) of 1.18 (95% CI 0.71–1.93) in favor of selenium. During the trial, the only serious adverse event (SAE) reported was a myocardial infarction, resulting in death in the treatment group. There was no evidence to suggest that this SAE was directly related to the treatment. With respect to the self-reported adverse events collected at every 6 months, there was minimal evidence of statistical differences between the treatment groups. The comparisons across treatment groups are presented in Table A1 (Supplemental Digital Content 1) of the ‘Web Appendix’. Patients taking the placebo were more likely to be anxious (P = 0.035). Patients taking selenium supplementation were more likely to report that sleep symptoms bothered them a lot, but less likely to report that it bothered them a little (P = 0.011). Both groups reported having no symptoms, with approximately equal probability. When adjusting for multiple testing, none of these results were statistically significant at the 0.05 significance level. Overall, selenium and placebo supplements were very well tolerated, helping explain the high percentage of study completers.

Discussion

The present RCT on selenium supplementation in pre-ART HIV-positive patients in Rwanda provides evidence of the benefits of selenium supplementation with respect to reduced rates of CD4+ declines. Our study found a significant decrease in CD4+ depletion rates, but not on the combined composite events, including reaching a CD4+ point of less than 350 cells/μl, AIDS-defining illness, or death.

Our study has strengths and limitations. The strengths include our recruitment of patients with higher CD4+ levels than previous trials that provide evidence for supplementation at an earlier stage and prior to the use of antiretrovirals. Moreover, we monitored adherence and high retention rate as a result of a strong commitment to the study on the part of the site nurses. Limitations include that the event rate for the composite outcome was much lower than the 60% used for our power calculations. This resulted in an underpowered analysis for this outcome. Moreover, only eight women were censored due to pregnancy in the placebo group compared to 15 in the treatment group. This unbalanced censoring may have biased the results in favor of the placebo treatment. This was the only observed factor by which the treatment groups differed following randomization. The different rates of censoring are not believed to have affected the CD4+ and viral load analyses.

Although the Miami trial provided strong evidence for suppression of viral burden and an indirect improvement of CD4+, Ross et al.[39] pointed out that these sub-analyses did not retain the original randomized treatment allocation. As such, these findings may be subject to bias not identified by Hurwitz et al. Particularly, analyses were performed in which participants in the selenium group who showed a large increase in serum selenium concentration ('selenium responders’: defined as a change in serum selenium concentration between baseline and 9 months of above 3 SDs more than the mean change in the placebo group) were compared with ‘selenium nonresponders’ and with those allocated to placebo. Our findings were most closely observed in the Botswana trial, where selenium supplementation was shown to significantly reduce CD4+ decline, but with no impact on viral burden.

The outcome of this study provides further evidence of the benefit of low-cost micronutrient supplementation to HIV-positive patients. This is particularly important for patients living in resource-limited settings such as much of Africa. Although assistance has been received from international funding agencies in order to make the antiretroviral drugs available for widespread distribution and treatment of HIV/AIDS patients, it is still a major financial burden to these countries. This financial burden is compounded by escalating healthcare costs associated with a rise in noncommunicable diseases [33,40]. In a period of worldwide financial uncertainty, any low-cost treatment that will slow the progression of the disease prior to the requirement for pharmacological intervention should be welcomed.

A growing concern in the treatment of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa is the increase in drug resistance among those being treated for HIV/AIDS, particularly in regions where there had been an early roll out of ART [41]. A delay in progression of the disease brought about by low-cost micronutrient supplementation would be advantageous in modifying the rate of drug resistance at least at the level of the individual.

The HIV disease burden in sub-Saharan Africa is still important, in terms of incidence, social impact, and healthcare costs. On the basis of the outcome of this study, micronutrient supplementation with the trace mineral selenium may be something to consider in the overall treatment plan for HIV-positive patients in the pre-ART phase of care.

Acknowledgements

The present trial was sponsored by Global Benefit Canada. We also thank CanAlt Labs and Seroyal – a nutraceutical company – for supplying the supplement.

Rwanda Selenium Trial Authorship Group. Additional authors: Richard Smyth∗; Heather Fay∗; Donatille Habarurema∗; Veneranda Mukarukundo∗; Alice Umurerwa∗; Cara Silva∗; Dugald Seely – Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine, North York, Ontario, Canada; Douglas J. McCready – Department of Economics, School of Business and Economics, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada; Steve Kanters – School of Population and Public Health, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; Edward J. Mills – Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford School of Medicine, Stanford, California, USA; Don Warren∗. ∗Indicates members of Rwanda. Selenium Supplementation Clinical Trial Team, Kigali, Rwanda.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Semba RD, Tang AM. Micronutrients and the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br J Nutr 1999; 81:181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross RL, Newberne PM. Role of nutrition in immunologic function. Physiol Rev 1980; 60:188–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendich A. Micronutrients and immune responses. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1990; 587:168–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beisel WR. Single nutrients and immunity. Am J Clin Nutr 1982; 35 (suppl):417–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beisel WR. Vitamins and the immune system. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1990; 587:5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baum M, Cassetti L, Bonvehi P, Shor-Posner G, Lu Y, Sauberlich H. Inadequate dietary intake and altered nutrition status in early HIV-1 infection. Nutrition 1994; 10:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beach RS, Mantero-Atienza E, Shor-Posner G, Javier JJ, Szapocznik J, Morgan R, et al. Specific nutrient abnormalities in asymptomatic HIV-1 infection. AIDS 1992; 6:701–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baum MK, Shor-Posner G, Zhang G, Lai H, Quesada JA, Campa A, et al. HIV-1 infection in women is associated with severe nutritional deficiencies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1997; 16:272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abrams B, Duncan D, Hertz-Picciotto I. A prospective study of dietary intake and acquired immune deficiency syndrome in HIV-seropositive homosexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1993; 6:949–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang AM, Graham NM, Kirby AJ, McCall AD, Willett WC, Saah AJ. Dietary micronutrient intake and risk progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected homosexual men. Am J Epidemiol 1993; 138:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrenpreis ED, Carlson SJ, Boorstein HL, Craig RM. Malabsorption and deficiency of vitamin B12 in HIV-infected patients with chronic diarrhea. Dig Dis Sci 1994; 39:2159–2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allavena C, Dousset B, May T, Dubois F, Canton P, Belleville F. Relationship of trace element, immunological markers, and HIV1 infection progression. Biol Trace Elem Res 1995; 47.:133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baum MK, Shor-Posner G, Lu Y, Rosner B, Sauberlich HE, Fletcher MA, et al. Micronutrients and HIV-1 disease progression. AIDS 1995; 9.:1051–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang AM, Graham NM, Saah AJ. Effects of micronutrient intake on survival in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Am J Epidemiol 1996; 143:1244–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang AM, Graham NM, Semba RD, Saah AJ. Association between serum vitamin A and E concentrations and HIV-1 disease progression. AIDS 1997; 11:613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang AM, Graham NM, Chandra RK, Saah AJ. Low serum vitamin B-12 concentrations are associated with faster human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) disease progression. J Nutr 1997; 127:345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baum MK, Shor-Posner G. Nutritional status and survival in HIV-1 disease. AIDS 1997; 11:689–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baum MK, Shor-Posner G, Lai S, et al. High risk of HIV-related mortality is associated with selenium deficiency. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1997; 15:370–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haug CJ, Aukrust P, Haug E, Morkrid L, Muller F, Froland SS. Severe deficiency of 1,25-dihydrovitamin D3 in human immunodeficiency virus infection: association with immunological hyperactivity and only minor changes in calcium homeostasis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998; 83:3832–3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campa A, Shor-Posner G, Indacochea F, Zhang G, Lai H, Asthana D, et al. Mortality risk in selenium-deficient HIV-positive children. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1999; 20:508–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Visser ME, Maartens G, Kossew G, Hussey GD. Plasma vitamin A and zinc concentrations in HIV-infected adults in Cape Town, South Africa. Br J Nutr 2003; 89:475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olmsted L, Schrauzer G, Flores-Arce M, Dowd J. Selenium supplementation of symptomatic human immunodeficiency virus infected patients. Biol Trace Elem Res 1988; 20:59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dworkin BM, Rosenthal WS, Wormser GP, Weiss L, Nunez M, Joline C, Herp A. Abnormalities of blood selenium and glutathione peroxidase activity in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and aids-related complex. Biol Trace Elem Res 1988; 15:167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lei X, Cheng W, McClung J. Metabolic regulation and function of glutathione peroxidase-1. Ann Rev Nutr 2007; 27:41–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jurkovič S, Osredkar J, Marc J. Molecular impact of glutathione peroxidases in antioxidant processes. Biochem Med 2008; 18:162–174. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arthur J, McKenzie R, Beckett G. Selenium in the immune system. J Nutr 2003; 133:1457S–1459S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck M. Regulation of cellular immune responses by selenium. Proc Nutr Soc 1999; 58:707–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck M, Levander O, Handy J. Selenium deficiency and viral infection. J Nutr 2003; 133:1457S–1459S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gill H, Walker G. Selenium, immune function and resistance to viral infections. Nutr Diet 2008; 65 (Suppl 3):S41–S47. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kiremidjian-Schumacher L, Roy M, Wishe H, Cohen M. Regulation of cellular immune responses by selenium. Biol Trace Elem Res 1992; 33:23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiremadjian-Schumacher L, Roy M, Wishe HI, Cohen MW, Stotzky G. Supplementation with selenium augments the function of natural killer and lymphokine-activated killer cells. Biol Trace Elem Res 1996; 52:227–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spallholz JE, Boylan LM, Larsen HS. Advances in understanding selenium's role in the immune system. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1990; 587:123–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harvard School of Public Health News. Costly noncommunicable diseases on rise in developing world. [Online]. Available at: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/hsph-in-the-news/global-health-noncommunicable-diseases-bloom/ [Accessed on: April 6, 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Courtman C, Ryssen Jv, Oelofse A. Selenium concentration of maize grain in South Africa and possible factors influencing the concentration. South Afr J Anim Sci 2012; 42:454–458. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hurst R, Siyame E, Young S, Chillimba A, Joy E, Black CR, et al. Soil-type influences human selenium status and underlies widespread selenium deficiency risks in Malawi. Sci Rep 2012; 3:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baum MK, Campa A, Lai S, Sales Martinez S, Tsalaile L, Burns P, et al. Effect of micronutrient supplementation on disease progression in asymptomatic, antiretroviral-naive, HIV-infected adults in Botswana: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 310:2154–2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hurwitz BE, Klaus JR, Llabre MM, Gonzalez A, Lawrence PJ, Maher KJ, et al. Suppression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral load with selenium supplementation: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:148–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kupka R, Mugusi F, Aboud S, Msamanga GI, Finkelstein JL, Spiegelman D, Fawzi WW. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of selenium supplements among HIV-infected pregnant women in Tanzania: effects on maternal and child outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 87:1802–1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ross DA, Cousens S, Wedner SH, Sismanidis C, et al. Does selenium supplementation slow progression of HIV? Potentially misleading presentation of the results of a trial. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:1555–1556 [author reply 1557]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim S, Vos T, Flaxman A, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380:2224–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamers R, Kityo C, Lange J, Wit TRd, Mugyenyi P. Global threat from drug resistant HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ 2012; 344:e4159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.