Abstract

Background

Previous studies demonstrated conflicting results about the association of sleep duration and hypertension. Given the potential relationship between sleep quality and hypertension, this study aimed to investigate the interaction of self-reported sleep duration and sleep quality on hypertension prevalence in adult Chinese males.

Methods

We undertook a cross-sectional analysis of 4144 male subjects. Sleep duration were measured by self-reported average sleep time during the past month. Sleep quality was evaluated using the standard Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure level ≥140/90 mm Hg or current antihypertensive treatment. The association between hypertension prevalence, sleep duration, and sleep quality was analyzed using logistic regression after adjusting for basic cardiovascular characteristics.

Results

Sleep duration shorter than 8 hours was found to be associated with increased hypertension, with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of 1.25 (95% CI, 1.03–1.52) for 7 hours, 1.41 (95% CI, 1.14–1.73) for 6 hours, and 2.38 (95% CI, 1.81–3.11) for <6 hours. Using very good sleep quality as the reference, good, poor, and very poor sleep quality were associated with hypertension, with odds ratios of 1.20 (95% CI, 1.01–1.42), 1.67 (95% CI, 1.32–2.11), and 2.32 (95% CI, 1.67–3.21), respectively. More importantly, further investigation of the association of different combinations of sleep duration and quality in relation to hypertension indicated an additive interaction.

Conclusions

There is an additive interaction of poor sleep quality and short sleep duration on hypertension prevalence. More comprehensive measurement of sleep should be performed in future studies.

Key words: sleep duration, sleep quality, hypertension

INTRODUCTION

The association between sleep disorders and hypertension has aroused the attention of cardiologists for a long time. Many prospective studies have suggested a robust relationship between short sleep duration and hypertension risk.1–5 However, sleep consists of both qualitative and quantitative aspects, and two previous studies suggested that maybe it is not enough to evaluate sleep only by measuring sleep duration when investigating the potential relationship between sleep and hypertension.6,7 In recent years, the potential associations between sleep quality and several cardiovascular risk factors have been explored in several cross-sectional studies, and the results suggested that sleep quality was associated with prevalence of metabolic syndrome and obesity.8–12 Poor sleep quality was also found to have an adverse effect on fasting blood glucose control.13,14 Hypertension shares many common potential mechanisms with cardiometabolic disorders,15 but the specific association of sleep quality and hypertension prevalence is still inconclusive.4,16 In addition, considering the fact that people with short sleep duration often have a high prevalence of poor sleep quality,17 it is necessary to preclude the potential interactively confounding effects of both sleep duration and sleep quality and confirm the specific and separate roles of sleep quality and duration in hypertension prevalence.

In this study, we investigated the potential association of self-reported sleep duration and quality in relation to hypertension prevalence in adult Chinese males using the data from a cross-sectional survey. Further, the interaction of sleep duration and quality on hypertension prevalence was explored.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

This study was designed as a cross-sectional study and was conducted from September to December 2013 in Fangezhuang, Tangshan, Lvjiatuo, and Qianjiaying communities located in the northern China city of Tangshan, which is approximately 180 km southeast of the capital of China. Subjects aged 18 years or older in the 4 communities were invited to participate in this study. Critical exclusion criteria included those with a previous diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) or restless legs syndrome (RLS), as well as those who reported snoring by themselves or roommates. The contents and purposes of this study were thoroughly explained to the participants prior to the study, and written consent was obtained. The study protocol was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical approval was obtained from the Science and Technology Committee of Tangshan City.

Citizens in the Fangezhuang, Tangshan, Lvjiatuo, and Qianjiaying communities are mainly employees of the Kailuan Group, a large-scale comprehensive enterprise that mainly manages coal products and has a higher male to female ratio than the general Chinese population. Only 571 female citizens were enrolled in this study, a sample size too small for subsequent statistical analysis; we therefore only presented the relevant results from male participants in the current report.

Anthropometric measurements

Doctors and nurses were trained in the standard protocol of measurement before the survey. Height and weight were measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg, respectively, when the subjects stood upright and were barefoot in light clothes. Two separate measurements were performed for each subject, and the average was used for analysis. BMI was calculated as the ratio of weight (kg) to height (m) squared (kg/m2). Blood pressure was measured in a sitting position with calibrated standard mercury sphygmomanometer (Yuyue Medical Equipment & Supply Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China), and an average of two readings was used in the present study. If the two readings differed by more than 5 mm Hg, a third reading was taken, and the average of three readings was used. Hypertension was defined according to the 7th edition report of the American Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of Hypertension18 as SBP ≥140 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥90 mm Hg on average of measurements or by current antihypertensive treatment according to hospital records.

Blood test

Subjects were asked to fast overnight before venous blood sample collection. Plasma samples were prepared by centrifuging at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes within 4 hours of blood collection for determination of total cholesterol (TC) and fasting blood glucose (FBG) in the central laboratory of Kailuan Hospital on automatic biochemical analyzers (Hitachi 717; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Questionnaire

A structured questionnaire was administered face to face to each subject and recorded on paper to obtain demographic and behavior-associated information, including age, gender, smoking status, drinking status, educational level, physical activity, sleep duration, and sleep quality. Smoking and drinking status were classified using self-reported information as “never”, “former”, or “current”. Subjects who consumed more than 175 grams of alcohol per week in the past half year were defined as current drinkers. Physical activity was evaluated from responses to questions about the type and frequency of physical activity during leisure time. Individuals were classified as “active” and “inactive” according to whether or not at least 30 minutes aerobic exercise for at least 5 days per week was attained. Educational level was assessed by responses to questions regarding the final degree attained, and senior high school or higher was defined as well-educated. Sleep duration was evaluated from the responses to questions about average sleep duration in the past month, and participants were reminded that time spent awake in bed was not included. Sleep duration was categorized into “<6 hours”, “6 hours”, “7 hours”, “8 hours”, and “>8 hours”. Sleep quality was evaluated using the standard Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), which is a widely used measure of sleep quality,19 and sleep quality was classified as “very good” (score <3 on PSQI), “good” (score 3 to <6 on PSQI), “poor” (score of 6 to <9 on PSQI), and “very poor” (score ≥9 on PSQI). The English version of the PSQI and the scoring system are provided in eAppendix 1.

In addition, considering the frequent comorbidity of sleep disorders with anxiety and depression, anxiety and depression status of participants was evaluated using the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9 scales, respectively. GAD-7 is a seven-question inventory for self-assessment and is one of the most common instruments for measuring severity of anxiety.20 PHQ-9 is a widely used nine-question inventory for self-assessment of depression.21

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean (standard error [SE]) and categorical variables as frequency (proportion). Continuous variables were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnetts’s post-hoc test, and categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. The association between sleep duration, sleep quality, and hypertension prevalence was investigated by logistic regression analysis, and we adjusted for plausible confounders, including age, BMI, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, educational level, and anxiety and depression scores. Further, to investigate the interaction of sleep duration and sleep quality on hypertension prevalence, participants were divided into groups of different combinations of sleep duration and sleep quality. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of each group were calculated using multiple logistic regression analysis, with the group of 8 hours’ sleep duration and very good sleep quality as the reference. For all comparisons, the level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 (two-sided). SPSS 19.0 (IBM, New York, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Basic characteristics

A total of 6120 citizens (98.9%) responded to our invitation, and 1926 (31.4%) of them were excluded due to report of OSAS (n = 351, 5.7%), RLS (n = 43, 0.7%), or snoring (n = 1532, 25.0%). A total of 4144 male subjects were finally enrolled in this study, and the basic characteristics of them are presented in Table 1 and Table 2 according to sleep duration and sleep quality. The numbers of subjects with sleep duration of <6 hours, 6 hours, 7 hours, 8 hours, and >8 hours were 356 (8.6%), 1021 (24.6%), 1446 (34.9%), 1082 (26.1%), and 239 (5.8%), respectively. The numbers of subjects with sleep quality of very good, good, poor, and very poor were 2369 (57.2%), 1146 (27.7%), 468 (11.3%), and 191 (4.6%), respectively. The average anxiety and depression scores and the percentage of current smokers, current drinkers, active exercisers, and well-educated subjects were significantly different in groups with different sleep durations or qualities.

Table 1. Basic characteristics of participants according to sleep duration in adult Chinese males.

| Sleep duration (hours) | |||||||

| <6 (n = 356) | 6 (n = 1021) | 7 (n = 1446) | 8 (n = 1082) | >8 (n = 239) | Total (n = 4144) | P | |

| Age (years) | 47.91 (0.37) | 46.84 (0.23) | 46.92 (0.18) | 46.98 (0.41) | 47.47 (0.42) | 47.04 (0.14) | 0.33 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.45 (0.19) | 25.17 (0.11) | 25.44 (0.10) | 25.19 (0.10) | 25.05 (0.19) | 25.28 (0.06) | 0.16 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 130.61 (0.71) | 129.79 (0.47) | 129.96 (0.38) | 129.62 (0.44) | 131.84 (0.81) | 130.02 (0.22) | 0.18 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 85.87 (0.47) | 85.9 (0.31) | 85.80 (0.25) | 85.71 (0.30) | 86.86 (0.55) | 85.88 (0.15) | 0.50 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.85 (0.05) | 4.88 (0.03) | 4.85 (0.02) | 4.92 (0.03) | 4.85 (0.05) | 4.88 (0.01) | 0.48 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mmol/L) | 5.57 (0.08) | 5.41 (0.05) | 5.43 (0.04) | 5.50 (0.05) | 5.29 (0.07) | 5.45 (0.02) | 0.08 |

| Score of anxiety | 4.40 (0.28) | 3.35 (0.15) | 1.63 (0.08) | 1.51 (0.09) | 1.93 (0.30) | 2.27 (0.06) | 0.00 |

| Score of depression | 5.06 (0.32) | 3.29 (0.16) | 2.02 (0.10) | 1.63 (0.10) | 2.25 (0.32) | 2.48 (0.07) | 0.00 |

| Current smoker (%) | 215 (60.5) | 611 (59.8) | 781 (54.0) | 576 (53.2) | 133 (55.8) | 2316 (55.9) | 0.00 |

| Current drinker (%) | 115 (32.2) | 289 (28.3) | 320 (22.1) | 285 (26.2) | 62 (25.9) | 1071 (25.8) | 0.00 |

| Active exercise habit (%) | 109 (30.6) | 311 (30.5) | 508 (35.1) | 392 (36.2) | 59 (24.6) | 1379 (33.3) | 0.00 |

| Well educated (%) | 140 (39.4) | 415 (40.6) | 450 (31.1) | 413 (38.2) | 92 (38.7) | 1510 (36.4) | 0.00 |

BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

Table 2. Basic characteristics of participants according to sleep quality in adult Chinese males.

| Sleep quality | ||||||

| Very good (n = 2369) | Good (n = 1146) | Poor (n = 468) | Very poor (n = 191) | Total (n = 4144) | P | |

| Age (years) | 47.20 (0.14) | 46.38 (0.40) | 47.48 (0.36) | 47.34 (0.52) | 47.01 (0.14) | 0.06 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.26 (0.08) | 25.33 (0.11) | 25.41 (0.18) | 25.01 (0.23) | 25.29 (0.06) | 0.58 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 130.53 (0.30) | 129.16 (0.42) | 130.16 (0.69) | 128.32 (1.04) | 130.01 (0.23) | 0.02 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 86.24 (0.20) | 85.32 (0.28) | 85.69 (0.48) | 85.38 (0.7) | 85.89 (0.15) | 0.05 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.90 (0.02) | 4.88 (0.03) | 4.77 (0.04) | 4.89 (0.06) | 4.88 (0.01) | 0.06 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mmol/L) | 5.47 (0.03) | 5.44 (0.05) | 5.38 (0.06) | 5.42 (0.10) | 5.45 (0.02) | 0.68 |

| Score of anxiety | 1.15 (0.06) | 3.06 (0.12) | 4.54 (0.26) | 6.4 (0.43) | 2.27 (0.06) | 0.00 |

| Score of depression | 1.21 (0.06) | 3.54 (0.13) | 4.60 (0.26) | 7.9 (0.53) | 2.48 (0.07) | 0.00 |

| Current smoker (%) | 1279 (54.0) | 662 (57.8) | 256 (54.7) | 119 (62.2) | 2316 (55.9) | 0.04 |

| Current drinker (%) | 572 (24.1) | 289 (25.2) | 132 (28.3) | 78 (40.8) | 1071 (25.8) | 0.00 |

| Active exercise habit (%) | 785 (33.1) | 416 (36.3) | 126 (26.9) | 52 (27.2) | 1379 (33.3) | 0.00 |

| Well educated (%) | 811 (34.2) | 452 (39.4) | 162 (34.7) | 85 (44.4) | 1510 (36.4) | 0.00 |

BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

Prevalence of hypertension

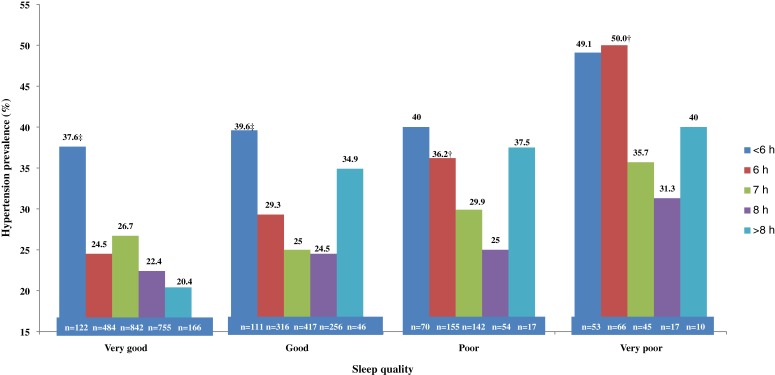

The prevalence of hypertension in subjects with different combinations of sleep duration and sleep quality are presented in Figure. Generally, a U-shaped relationship could be observed between sleep duration and hypertension prevalence. With the exception of those with very good sleep quality, subjects with sleep duration of 8 hours had the lowest prevalence of hypertension, and participants with both less and more sleep time had increased hypertension prevalence. However, the trend was not statistically significant. Figure also shows that hypertension prevalence increased with worsening sleep quality in those with different sleep duration, but this trend was also not statistically significant.

Figure. Hypertension prevalence in participants with different combinations of sleep duration and sleep quality.

Association of sleep duration or sleep quality in related to hypertension prevalence

The association between sleep duration or quality and hypertension prevalence was analyzed using logistic regression, and the results are presented in Table 3. With sleep duration of 8 hours as the reference, less sleep time was found to be associated with the prevalence of hypertension among Chinese males after adjustment of confounders, with an odds ratio of 1.25 (95% CI, 1.03–1.52) for 7 hours, 1.41 (95% CI, 1.14–1.73) for 6 hours, and 2.38 (95% CI, 1.81–3.11) for less than 6 hours. In contrast, no significant relationship was found between sleep duration of more than 8 hours and hypertension prevalence. In comparison to those with very good sleep quality, the ORs for subjects with good, poor, and very poor sleep quality were 1.20 (95% CI, 1.01–1.42), 1.67 (95% CI, 1.32–2.11) and 2.32 (95% CI, 1.67–3.21), respectively.

Table 3. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of sleep duration and sleep quality for hypertension prevalence in adult Chinese males.

| n | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | P | ||

| Sleep duration (hours) |

<6 | 356 | 2.40 (1.86–3.11) | 0.00 | 2.41 (1.85–3.18) | 0.00 |

| 6 | 1021 | 1.37 (1.13–1.67) | 0.00 | 1.39 (1.14–1.69) | 0.00 | |

| 7 | 1446 | 1.24 (1.03–1.49) | 0.02 | 1.22 (1.02–1.47) | 0.00 | |

| 8 | 1082 | Reference | — | Reference | — | |

| >8 | 239 | 0.88 (0.64–1.20) | 0.42 | 0.84 (0.61–1.17) | 0.38 | |

| n | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | P | ||

| Sleep qualitya |

Very good | 2369 | Reference | — | Reference | — |

| Good | 1146 | 1.16 (0.99–1.36) | 0.08 | 1.15 (1.08–1.23) | 0.04 | |

| Poor | 438 | 1.65 (1.33–2.06) | 0.00 | 1.66 (1.32–2.09) | 0.00 | |

| Very poor | 191 | 2.16 (1.59–2.93) | 0.00 | 2.30 (1.68–3.17) | 0.00 | |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

aSleep quality was evaluated by standard Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and is categorized based on total score.

bAdjusted for age, body mass index, status of smoking and drinking, exercise habit, educational level, score of anxiety and depression.

Association of different combinations of sleep duration and sleep quality in relation to hypertension prevalence

The unadjusted and adjusted ORs for hypertension prevalence according to different combinations of sleep duration and sleep quality are presented in Table 4. In comparison to the those with 8 hours sleep duration and very good sleep quality (the reference group), subjects in the following groups had increased hypertension prevalence after adjusting for the basic cardiometabolic characteristics: <6 hours sleep duration combined with any sleep quality (OR 2.27 [95% CI, 1.46–3.53] for very good; OR 2.54 [95% CI, 1.60–4.04] for good; OR 3.42 [95% CI, 2.21–5.30] for poor or very poor), 6 hours sleep duration combined with good, poor, or very poor sleep (OR 1.53 [95% CI, 1.10–2.13] for good; OR 2.40 [95% CI, 1.65–3.49] for poor or very poor), and 7 hours sleep duration combined with poor or very poor sleep (OR 1.68 [95% CI, 1.13–2.51]).

Table 4. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for hypertension prevalence according to different combinations of sleep duration and quality in adult Chinese males.

| Sleep duration (hours) | |||||||||

| <6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | |

| Sleep qualitya |

Very good | 122 | 2.09 (1.38–3.16) | 484 | 1.27 (0.99–1.60) | 842 | 1.13 (0.86–1.48) | 755 | Reference |

| Good | 111 | 2.28 (1.49–3.49) | 316 | 1.44 (1.07–1.94) | 417 | 1.16 (0.87–1.54) | 256 | 1.13 (0.80–1.58) | |

| Poor or very poor | 123 | 3.25 (2.18–4.83) | 221 | 2.35 (1.70–3.25) | 187 | 1.58 (1.10–2.27) | 71 | 1.25 (0.71–2.20) | |

| Adjustedb | n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | |

| Sleep qualitya |

Very good | 122 | 2.27 (1.46–3.53) | 484 | 1.27 (0.98–1.63) | 842 | 1.18 (0.88–1.58) | 755 | Reference |

| Good | 111 | 2.54 (1.60–4.04) | 316 | 1.53 (1.10–2.13) | 417 | 1.21 (0.89–1.64) | 256 | 1.14 (0.79–1.66) | |

| Poor or very poor | 123 | 3.42 (2.21–5.30) | 221 | 2.40 (1.65–3.49) | 187 | 1.68 (1.13–2.51) | 71 | 1.39 (0.76–2.54) | |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

aSleep quality was evaluated by standard Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and is categorized based on total score.

bAdjusted for age, body mass index, status of smoking and drinking, exercise habit, educational level, score of anxiety and depression.

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional study, we investigated the separate and combined association of sleep duration and sleep quality with the prevalence of hypertension in adult Chinese males. Shorter sleep duration than normal was found to be associated with hypertension prevalence, but not longer sleep duration. In addition, poor sleep quality was also associated with hypertension prevalence. The present study investigated the association of different combinations of sleep duration and sleep quality in relation to hypertension prevalence, and the results indicated an additive interaction between sleep quality and duration and hypertension prevalence.

It has been argued that the relationship between sleep and hypertension maybe gender-specific. Two prospective studies conducted in English and Korean populations22,23 and several cross-sectional studies22,24–26 have demonstrated that short sleep duration was associated with hypertension incidence only in women. The underlying mechanisms that explain sex-specific correlation of short sleep duration and hypertension are still unknown, although sex differences in hormone secretion, stress responses, inflammatory reaction, and changes in sympathetic nerve activity have been suggested.27–30 Though the current literature supports a more robust correlation between short sleep duration and hypertension in women than men, one cross-sectional study by Fang et al indicated the possibility of a complex association between sleep duration and hypertension.31 The present cross-sectional study adds new evidence concerning the association between sleep duration and hypertension in men. However, we still hold a cautious attitude towards the gender-specific association mentioned above because we think only measuring sleep duration in the previous studies is not sufficient to assess the global sleep status, and results are somewhat unreliable.

Two previous studies have suggested a U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and hypertension in adults and adolescents, which meant not only short but also long sleep duration was related to hypertension prevalence and incidence.32,33 In the current study, we also observed a U-shaped trend between sleep duration and hypertension prevalence, but it failed to reach statistical significance. One of the findings of the current study was that sleep duration and quality were additively related to hypertension. Neglecting the potential role of sleep quality may explain the conflicting results, but we must note that the small sample size of subjects with longer sleep duration may make our results less persuasive.

Sleep has both qualitative and quantitative aspects. Two studies have demonstrated that short sleep duration only failed to increase hypertension risk, but a combination of sleep duration and other sleep disorders did increase risk, which indicated that evaluation of sleep only by measuring sleep duration was not sufficient.6,7 This viewpoint was supported by the current study. Sleep quality was measured by the PSQI in this study, and the results show that sleep quality was also significantly correlated with hypertension risk. Bruno et al investigated the relationship between sleep quality assessed by the PSQI and resistant hypertension, and their results were consistent with ours.34 Another study also indicated a relationship between sleep quality and blood pressure level, although sleep quality was assessed by overnight polysomnography in that study.35

We must note that people with sleep insufficiency often have poor sleep quality. Therefore, to preclude the interactively confounding effect of sleep duration and quality in the current study, the separate and combined associations of sleep duration and sleep quality in relation to hypertension were explored. The results demonstrated that the association of sleep duration and sleep quality with hypertension was an additive relationship. For example, no category of sleep quality was found to be related to hypertension prevalence among those with normal sleep duration. However, among those with sleep duration less than 6 hours, each category of sleep quality was related to hypertension prevalence. In contrast, for those with 7 hours sleep, only poor or very poor sleep quality was found to be associated with hypertension. The current study suggests an approximately equal contribution of sleep quality and sleep duration to hypertension prevalence. Failing to pay attention to the effect of sleep quality may explain the conflicting results among previous studies about the relationship between sleep duration and hypertension prevalence or development.1,22,36–38

OSAS and RLS are possible confounding factors in the relationship between sleep status and hypertension prevalence,39,40 and it was necessary to preclude the potential effects of these conditions in the current study. The diagnosis of OSAS was based on the results of polysomnography, but the test was very difficult to perform for each subject due to the limited funds and time. Therefore, we adopted a comparatively easy way to preclude OSAS according to whether or not the subject snored during sleep, which was reported by the subjects themselves or by their roommates. It has been reported that snoring has a high sensitivity (87%) for detecting OSAS.41 In addition, RLS was excluded on the basis of self-reported (roommate-reported) symptoms, considering that the clinical diagnosis of RLS was mainly based on self-reported symptoms.42

In the current study, we paid attention to several potential confounders for the association between sleep and hypertension, such as educational level, anxiety, and depression, which were rarely controlled for in previous studies. Socio-economic status is a well-known risk factor for hypertension.43 Recently, mental status, such as anxiety and depression, has also been suggested to be related to onset and control of hypertension.44,45 Considering the frequent comorbidity of anxiety and depression in sleep disorders and the effect of educational level on sleep,5 it is necessary to control for the confounding effect of these factors, as we have done in the present study.

Possible mechanisms accounting for the association between sleep and hypertension have been reported in a couple of previous studies, although they are far from being fully elucidated. Most of those studies support that sympathetic overactivity due to sleep deprivation was associated with elevated blood pressure level.46–48 Additionally, as a contributor to psychological stress, sleep insufficiency could also induce sodium retention, proinflammatory responses, and endothelial dysfunction through the activation of the neuroendocrine system.28,48,49

Due to the cross-sectional design of the present study, we cannot assess the causal relationship between the two sleep aspects and hypertension prevalence. However, the hypothesis that sleep deprivation is involved in the development and sustainment of hypertension has been better established than the opposite cause-effect link. Although it is possible that living with hypertension, which acts as a mental stressor, may disturb sleep homeostasis directly or through drug treatments (such as diuretics) that are often prescribed for hypertensive patients, rare relevant evidence is available in the current literature.50,51 In addition, Bruno et al analyzed the association of sleep quality and the most frequently prescribed antihypertensive agents and found no relationship between them.34

Our study has several limitations. First of all, it has been reported that logistic analysis used in cross-sectional study may overestimate the prevalence ratio, although it is still the most frequently used method in studies with a similar design to ours.52 Second, there are no standard cut-off values to judge good or poor sleep quality, and the cut-off values used in this study were based on previous reports and our experience. Third, eating habit is one important meditating factor in the relationship between sleep disorders and increased prevalence of hypertension, but we did not investigate this because we did not have suitable questionnaires about eating habits.

Despite the above limitations, this cross-sectional study demonstrates for the first time that both short sleep duration and poor sleep quality are associated with hypertension prevalence in adult Chinese males. More importantly, the current study suggests that the association of sleep duration and quality with hypertension is an additive relationship.

ONLINE ONLY MATERIAL

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was founded by grants from the 12th Five-year Science and Technology Support Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant No. 2013BAI06B02). We thank the staff of the Kailuan Study for their work in data collection.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, Buijs RM, Kreier F, Pickering TG, et al. Short sleep duration as a risk factor for hypertension: analyses of the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hypertension. 2006;47:833–9. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000217362.34748.e0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gangwisch JE, Feskanich D, Malaspina D, Shen S, Forman JP. Sleep duration and risk for hypertension in women: results from the nurses’ health study. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26:903–11. 10.1093/ajh/hpt044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wells JC, Hallal PC, Reichert FF, Menezes AM, Araújo CL, Victora CG. Sleep patterns and television viewing in relation to obesity and blood pressure: evidence from an adolescent Brazilian birth cohort. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32(7):1042–9. 10.1038/ijo.2008.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suka M, Yoshida K, Sugimori H. Persistent insomnia is a predictor of hypertension in Japanese male workers. J Occup Health. 2003;45:344–50. 10.1539/joh.45.344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assari S, Moghani Lankarani M, Kazemi Saleh D, Ahmadi K. Gender modifies the effects of education and income on sleep quality of the patients with coronary artery disease. Int Cardiovasc Res J. 2013;7:141–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bansil P, Kuklina EV, Merritt RK, Yoon PW. Associations between sleep disorders, sleep duration, quality of sleep, and hypertension: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005 to 2008. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13:739–43. 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00500.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Shaffer ML, Vela-Bueno A, Basta M, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration and incident hypertension: the Penn State Cohort. Hypertension. 2012;60:929–35. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.193268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okubo N, Matsuzaka M, Takahashi I, Sawada K, Sato S, Akimoto N, et al. Relationship between self-reported sleep quality and metabolic syndrome in general population. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:562. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hung HC, Yang YC, Ou HY, Wu JS, Lu FH, Chang CJ. The association between self-reported sleep quality and metabolic syndrome. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54304. 10.1371/journal.pone.0054304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Logue EE, Scott ED, Palmieri PA, Dudley P. Sleep duration, quality, or stability and obesity in an urban family medicine center. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10:177–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee J, Choi YS, Jeong YJ, Lee J, Kim JH, Kim SH, et al. Poor-quality sleep is associated with metabolic syndrome in Korean adults. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2013;231:281–91. 10.1620/tjem.231.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hung HC, Yang YC, Ou HY, Wu JS, Lu FH, Chang CJ. The association between self-reported sleep quality and overweight in a Chinese population. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:486–92. 10.1002/oby.20259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lou P, Chen P, Zhang L, Zhang P, Chang G, Zhang N, et al. Interaction of sleep quality and sleep duration on impaired fasting glucose: a population-based cross-sectional survey in China. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004436. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iyer SR. Sleep and type 2 diabetes mellitus- clinical implications. J Assoc Physicians India. 2012;60:42–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falkner B, Cossrow ND. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and obesity-associated hypertension in the racial ethnic minorities of the United States. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16:449. 10.1007/s11906-014-0449-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips B, Bůzková P, Enright P; Cardiovascular Health Study Research Group . Insomnia did not predict incident hypertension in older adults in the cardiovascular health study. Sleep. 2009;32(1):65–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bliwise DL, Holm-Larsen T, Goble S. Increases in duration of first uninterrupted sleep period are associated with improvements in PSQI-measured sleep quality. Sleep Med. 2014;15:1276–8. 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–52. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donker T, van Straten A, Marks I, Cuijpers P. Quick and easy self-rating of Generalized Anxiety Disorder: validity of the Dutch web-based GAD-7, GAD-2 and GAD-SI. Psychiatry Res. 2011;188:58–64. 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Ting R, Lam M, Lam J, Nan H, Yeung R, et al. Measuring depressive symptoms using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in Hong Kong Chinese subjects with type 2 diabetes. J Affect Disord. 2013;151:660–6. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cappuccio FP, Stranges S, Kandala NB, Miller MA, Taggart FM, Kumari M, et al. Gender-specific associations of short sleep duration with prevalent and incident hypertension: the Whitehall II Study. Hypertension. 2007;50:693–700. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.095471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SJ, Lee SK, Kim SH, Yun CH, Kim JH, Thomas RJ, et al. Genetic association of short sleep duration with hypertension incidence—a 6-year follow-up in the Korean genome and epidemiology study. Circ J. 2012;76:907–13. 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-0713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stang A, Moebus S, Möhlenkamp S, Erbel R, Jöckel KH; Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study Investigative Group . Gender-specific associations of short sleep duration with prevalent hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;51(3):e15–6; author reply e17. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.108456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stranges S, Dorn JM, Shipley MJ, Kandala NB, Trevisan M, Miller MA, et al. Correlates of short and long sleep duration: a cross-cultural comparison between the United Kingdom and the United States: the Whitehall II Study and the Western New York Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:1353–64. 10.1093/aje/kwn337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stranges S, Dorn JM, Cappuccio FP, Donahue RP, Rafalson LB, Hovey KM, et al. A population-based study of reduced sleep duration and hypertension: the strongest association may be in premenopausal women. J Hypertens. 2010;28:896–902. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328335d076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sowers MR, La Pietra MT. Menopause: its epidemiology and potential association with chronic diseases. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17:287–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meerlo P, Sgoifo A, Suchecki D. Restricted and disrupted sleep: effects on autonomic function, neuroendocrine stress systems and stress responsivity. Sleep Med Rev. 2008;12:197–210. 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsukawa T, Sugiyama Y, Watanabe T, Kobayashi F, Mano T. Gender difference in age-related changes in muscle sympathetic nerve activity in healthy subjects. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R1600–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohayon MM, Zulley J. Correlates of global sleep dissatisfaction in the German population. Sleep. 2001;24:780–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang J, Wheaton AG, Keenan NL, Greenlund KJ, Perry GS, Croft JB. Association of sleep duration and hypertension among US adults varies by age and sex. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:335–41. 10.1038/ajh.2011.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo X, Zheng L, Li Y, Yu S, Liu S, Zhou X, et al. Association between sleep duration and hypertension among Chinese children and adolescents. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:774–81. 10.1002/clc.20976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gottlieb DJ, Redline S, Nieto FJ, Baldwin CM, Newman AB, Resnick HE, et al. Association of usual sleep duration with hypertension: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2006;29:1009–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruno RM, Palagini L, Gemignani A, Virdis A, Di Giulio A, Ghiadoni L, et al. Poor sleep quality and resistant hypertension. Sleep Med. 2013;14:1157–63. 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hannon TS, Tu W, Watson SE, Jalou H, Chakravorty S, Arslanian SA. Morning blood pressure is associated with sleep quality in obese adolescents. J Pediatr. 2014;164:313–7. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bjorvatn B, Sagen IM, Øyane N, Waage S, Fetveit A, Pallesen S, et al. The association between sleep duration, body mass index and metabolic measures in the Hordaland Health Study. J Sleep Res. 2007;16(1):66–76. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi KM, Lee JS, Park HS, Baik SH, Choi DS, Kim SM. Relationship between sleep duration and the metabolic syndrome: Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey 2001. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32:1091–7. 10.1038/ijo.2008.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopez-Garcia E, Faubel R, Guallar-Castillon P, Leon-Muñoz L, Banegas JR, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. Self-reported sleep duration and hypertension in older Spanish adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(4):663–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02177.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, Abraham WT, Costa F, Culebras A, et al. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/American College Of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council On Cardiovascular Nursing. In collaboration with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Center on Sleep Disorders Research (National Institutes of Health). Circulation. 2008;118:1080–111. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.189420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Batool-Anwar S, Malhotra A, Forman J, Winkelman J, Li Y, Gao X. Restless legs syndrome and hypertension in middle-aged women. Hypertension. 2011;58:791–6. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.174037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pedrosa RP, Drager LF, Gonzaga CC, Sousa MG, de Paula LK, Amaro AC, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea: the most common secondary cause of hypertension associated with resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;58(5):811–7. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.179788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toro BE. New treatment options for the management of restless leg syndrome. J Neurosci Nurs. 2014;46:227–32. 10.1097/JNN.0000000000000068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colhoun HM, Hemingway H, Poulter NR. Socio-economic status and blood pressure: an overview analysis. J Hum Hypertens. 1998;12:91–110. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Almas A, Patel J, Ghori U, Ali A, Edhi AI, Khan MA. Depression is linked to uncontrolled hypertension: a case-control study from Karachi, Pakistan. J Ment Health. 2014;23(6):292–6. 10.3109/09638237.2014.924047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stein DJ, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Bruffaerts R, de Jonge P, Liu Z, et al. Associations between mental disorders and subsequent onset of hypertension. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:142–9. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chouchou F, Pichot V, Pépin JL, Tamisier R, Celle S, Maudoux D, et al. ; PROOF Study Group . Sympathetic overactivity due to sleep fragmentation is associated with elevated diurnal systolic blood pressure in healthy elderly subjects: the PROOF-SYNAPSE study. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(28):2122–31, 2131a. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogawa Y, Kanbayashi T, Saito Y, Takahashi Y, Kitajima T, Takahashi K, et al. Total sleep deprivation elevates blood pressure through arterial baroreflex resetting: a study with microneurographic technique. Sleep. 2003;26:986–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Light KC, Koepke JP, Obrist PA, Willis PW 4th. Psychological stress induces sodium and fluid retention in men at high risk for hypertension. Science. 1983;220(4595):429–31. 10.1126/science.6836285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Hyperarousal and insomnia: state of the science. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:9–15. 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hayase M, Shimada M, Seki H. Sleep quality and stress in women with pregnancy-induced hypertension and gestational diabetes mellitus. Women Birth. 2014;27:190–5. 10.1016/j.wombi.2014.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yontar OC, Erdem A, Yilmaz MB. Sleep quality in patients with hypertension: additional negative effect of drug therapy. Sleep Med. 2009;10:1168; author reply-9. 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:21. 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.