Abstract

Introduction

Vascular malformations have devastating cosmetic effects in addition to being associated with pain and bleeding. Sclerotherapy has been used as an effective therapeutic modality for the management of vascular malformations. The purpose of this case series is to describe our clinical experience of using sodium tetradecyl sulphate (STS) 3 % in the treatment of venous malformation lesions of head and neck.

Materials and Methods

Thirteen patients were included in this study (three male and ten female; age range between 8 months and 54 years; mean age 18.2 years, ±SD 15.71). The patients were treated by 3 % STS intralesional injections. Of the thirteen patients treated, complete resolution occurred in four patients (28.57 %), a good response occurred in five patients (35.7 %), a moderate response in two patients (14.28 %), a mild response in two patients (14.28 %) and no response in one patient (7.14 %). The side effects encountered in all patients were pain and edema after injection which was controlled by oral analgesics and an intramuscular injection of dexamethasone. In addition, two patients developed a superficial ulceration (11.76 %) which healed uneventfully, and one patient developed ecchymosis after injection (5.88 %).

Conclusion

Sclerotherapy with 3 % STS is a simple, safe, and effective modality for the treatment of venous malformations.

Keywords: Sotradecol, STS, Venous malformation (VnM), Vascular malformations (VM), Sclerotherapy, Head and neck

Introduction

The classification of vascular malformations has undergone tremendous modifications in recent years. A modified scheme (Table 1), described by Neville [1] divides vascular malformations into: (a) simple (capillary, venous, lymphatic, arteriovenous) or (b) a combination of two or more of the previous categories. Others classify vascular malformations as low flow (capillary, venous and lymphatic malformations or a combination of them) and high flow (arterial and arteriovenous shunt) [1–3]. Previous literature reports an incidence of 14–65 % of vascular malformations occurring in the head and neck region [4]. Vascular malformations (VM) are characterized by thin non-proliferating endothelial wall surrounded by a thin smooth muscle layer. These lesions normally don’t involute, but continue to increase in size in proportion with body size, often reaching enormous volumes [4]. In contrast, Hemangiomas are active proliferating tumors which demonstrate a characteristic pattern of rapid postnatal growth followed by slow involution [2, 3]. Although the serendipitous discovery of the therapeutic efficacy of propranolol in the management of infantile hemangiomas has revolutionized the care and outcomes of these lesions [5, 6], there is no standard treatment protocol for the management of VM. Treatment options of low flow VM include simple observation, minimally invasive interventions such as sclerotherapy or embolization [7, 8], laser ablation [9], cryotherapy [10], or more aggressive surgical resection. Management of these lesions varies according to the patient’s age, size of the lesion, location, type of the lesion, as well as surgeon experience. VMs of the head and neck region can have a huge impact on cosmesis as well as function. Lesions of the peri-oral area can be associated with bleeding and discomfort during simple daily activities such as eating.

Table 1.

classification of vascular anomalies by Neville

| Vascular tumors | Vascular malformations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemangiomas of Infancy | Superficial | Simple | Capillary |

| Deep | Venous | ||

| Mixed | Lymphatic | ||

| Arteriovenous | |||

| Congenital hemangiomas | NICH | Combined | |

| RICH | |||

| Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma | |||

| Tufted Angioma | |||

| Pyogenic Granuloma | |||

NICH non involution congenital hemangioma, RICH rapid involution congenital hemangioma

Sclerotherapy is a viable option for the management of VMs due to its safety, ease of administration, and acceptable aesthetic and functional outcomes. By using sclerotherapy, surgical intervention can often be avoided or at least minimized. Sodium tetradecyl sulphate, 3 % STS (Sotradecol® [11], Fibro-Vein®) [12], has been widely used as sclerosing agent since 1946. STS is used commonly in the treatment of small varicose veins of the legs, as well as venous and lymphatic malformations [13, 14]. The mechanism of action of STS is to produce maximum endothelial damage with minimal thrombus formation leading to fibrosis of the lesion [12] which leads to shrinkage. The vascular luminal obliteration may or may not be permanent [15].

In our case series, STS was used for the treatment of Venous malformations (VnM) of the head and neck region. Our endpoints included patient satisfaction and objective evaluation of the lesions’ size.

Patients and Methods

After obtaining the Institutional Review Board approval, a series of 13 consecutive patients, who were properly informed of the risks and benefits, were evaluated and treated at the Maxillofacial Unit of Surgical Specialties Hospital, Medical City, Baghdad, for venous malformations of the head and neck in the period between May 2009 and May 2010 (Table 2). The pre-treatment evaluation consisted of a clinical assessment, a thorough history and physical examination, and imaging studies. Imaging of the VnM was performed by Doppler ultrasonography and/or computerized tomography (CT) scan with intravenous contrast. Three patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), whereas three other patients were assessed using conventional angiography. The following parameters were recorded: age at presentation, chief complaint, previous treatment, size (largest diameter in cm), location of the lesion, and presence or absence of phleboliths. All patients’ VnM were treated by percutaneous and/or permucosal sclerotherapy with 3 % STS solution. The number of sclerotherapy injections and post-treatment responses, assessed by clinical examination, were recorded.

Table 2.

Patient information for current series

| Patient | Age (years) | Gender | Site | Size of lesion (cm) | No. of sessions | Respond to treatment | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | M | Upper lip midline | 1.5 | 1 | Moderate | Edema |

| 2 | 43 | F | Two lesions: left buccal mucosa, left lateral border of the tongue | 1, 2 respectively | 2 for each | Complete resolution | Edema, pain |

| 3 | 6 | F | Three lesions: left buccal mucosa, ventral surface of the tongue and submandibular region | 1, 2 and 4 respectively | 1 | No response | Edema |

| 4 | 16 | F | Multiple lesions on left lateral border of the tongue | 3 collectively | 2 | Complete resolution | Edema, pain and ulcer |

| 5 | 21 | F | Right side of lower lip and labial mucosa | 1.5 | 3 | Good | Edema, pain |

| 6 | 20 | M | Left parotid region | 8 | 2 | Moderate | Edema, pain |

| 7 | 54 | F | Right buccal mucosa | 2.5 | 1 | Complete resolution | Edema, pain |

| 8 | 7 | F | Left buccal and upper labial mucosa | 2 | 1 | Good | Edema, pain, ecchymosis and ulcer |

| 9 | 8 months | M | Right lateral border of the tongue | 4 | 2 | Good | Edema |

| 10 | 17 | F | Two lesions: right retro-mandibular trigon, lateral border of tongue | 1, 1.5 respectively | 1 | Good | Edema, pain |

| 11 | 19 | F | Left lateral border of tongue | 2 | 1 | Complete resolution | Edema, pain and ulcer |

| 12 | 7 | F | Right cheek | 2 | 1 | Mild | Edema, pain |

| 13 | 25 | F | Left cheek | 3 | 1 | Good | Edema, pain |

| Average | 18.20769 | 3.2307692 | 1.46153 | ||||

| ±SD | 15.71286 | 2.0270605 | 0.66022 |

Each patient received an intralesional injection of STS 3 % solution under aseptic technique and without local or general anesthesia, except for children under 2 years of age where general anesthesia was used during the injections. The 3 % Sotradecol® solution was injected into each lesion using an insulin syringe and 26-gauge needle. The agent was delivered without radiological guidance. After introducing the needle, the plunger was withdrawn to look for backflow of blood and to confirm appropriate entry of the needle into the center of the vascular space. The sclerosing agent was then injected until the lesion blanched. Larger lesions were treated by multiple injections. A minimum of 0.5–2 ml of the agent was injected into each lesion (at a ratio of 0.5 ml for each 2 cm of lesion size) or a quarter the lesion volume [20]. A compression dressing was applied for at least 2 h post injection. Each milliliter of 3 % STS contains 30 mg of sodium tetradecyl sulfate, 0.02 ml of benzyl alcohol, and 9.0 mg of dibasic sodium phosphate, anhydrous in water for injection at a pH of 7.9; monobasic sodium phosphate and/or sodium hydroxide were added, if needed for pH adjustment [10].

All the patients received an oral analgesic and a single postoperative dose of intramuscular (gluteal) injection of dexamethasone (4 mg) for adults and 0.2 mg/kg for children to decrease the inflammation and pain post injection. Follow up of each patient was scheduled every 2 weeks, and therapy was repeated after 4 weeks if there was no response or only a partial response.

The response to the treatment was graded as follows: no response (no change in size after injection), mild response (25 % decrease in the size after injection), moderate response (50 % decrease in size after injection), good response (75 % decrease in size after injection), and complete response of the lesion (100 % shrinkage of the lesion with normal appearing skin and/or mucosa). Response to treatment was assessed clinically and by using photographic assessment at each visit with follow up that ranged between 6 and 12 months.

Results

Data was collected from 13 patients (ten female and three male; mean age 18.2 years, ±SD 15.71, age range between 8 months and 54 years). All patients except one reported that the VnM was present at birth. One patient had the lesion develop at age of 40 years. The lesions involved the following locations (Table 2): lips (n = 1), cheek (n = 3), buccal mucosa (n = 2), tongue (n = 3), combined lesions of labial and buccal mucosa (n = 2), combined lesions of buccal mucosa and tongue (n = 2) and left parotid region (n = 1). The patient’s chief complaint mostly centered on the cosmetic disfigurement caused by the lesion. No prior therapeutic interventions were recorded except in one patient who reported undergoing intralesional steroid injection. The size of the vascular malformations ranged from 1 to 8 cm in its widest diameter with an average size of 3.2 cm. The number of injections of STS per lesion ranged from one to three at different visits with a typical dose of 0.5–2 ml per injection, well under the maximum recommended dose of 0.5 ml/kg [11]. An average of 0.5 ml of STS for each 2 ml volume of lesion was administered [20]. Among the 13 patients, the responses to treatment were complete response in four patients (30.8 %), good response in 4 patients (30.8 %), moderate response in two patients (15.4 %), mild response in two patients (15.4 %) and no response in 1 patient (7.7 %). (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4) No hypersensitivity reactions were observed.

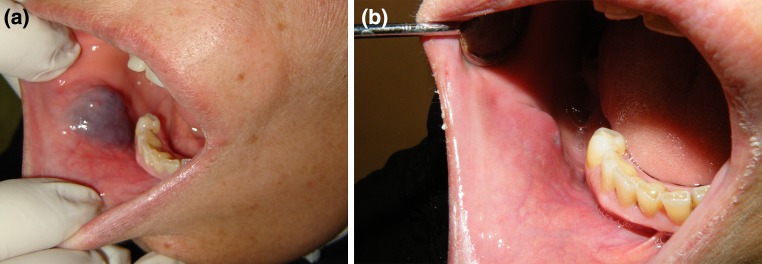

Fig. 1.

49 year old female with VnM of the buccal mucosa. a Pre-op demonstrating submucosal bluish and fluctuant lesion. b Post-op after a single dose of STS

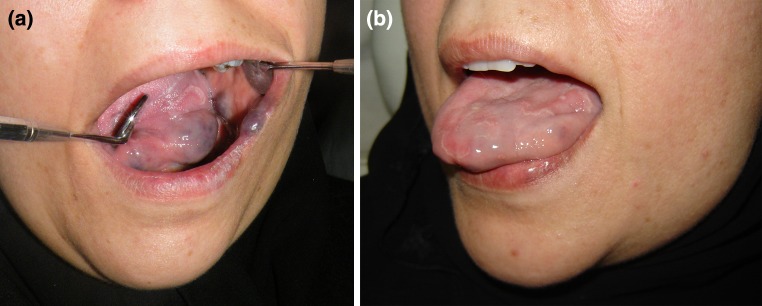

Fig. 2.

45 year old female with VnM of the lateral border of the tongue and buccal mucosa. a Pre-op. b Post-op after two doses of STS

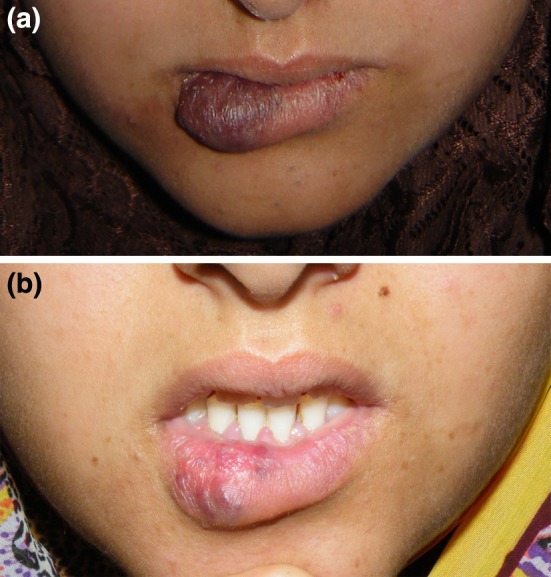

Fig. 3.

21 year old female with LF/VM of the lower lip and labial mucosa. a Pre-op. b Post-op after 4 injections of STS

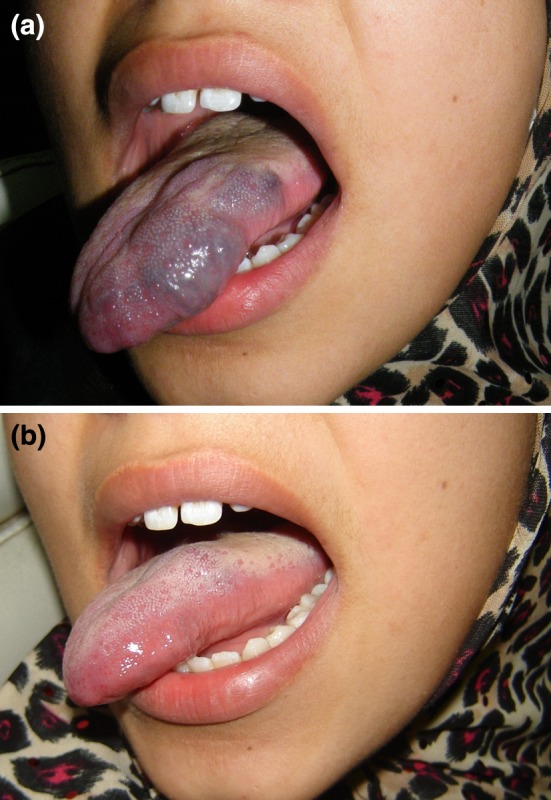

Fig. 4.

16 year old female with VnM of the lateral border of the tongue. a Pre-op. b Post-op after receiving two doses of STS

The side effects encountered in all patients were pain and edema after injection. Two patients had a superficial ulceration (15.4 %) which healed without scarring. One patient had mild ecchymosis after the injection (7.7 %).

Discussion

Management of VnM is dependent on size, location, and often surgeon preference and comfort. Small VnM’s can be completely excised. However, complete surgical eradication of extensive oral or facial venous malformation is rarely possible without jeopardizing function or causing additional disfigurement [9] and/or severe hemorrhage [16]. Other modalities of treatments includes the use of Nd:YAG laser therapy. The disadvantage of this treatment is due to its limited use for superficial cutaneous lesions and the risk of damaging the close vital structures in the face [9]. Sclerotherapy is a safe and effective treatment with minimal morbidity. There are many other agents used for sclerotherapy: sodium morrhuate, bleomycin, ethanolamine oleate, ethanol, hypertonic saline, and various combinations of these medications [8]. The most common side effects were skin necrosis and ulceration, hypersensitivity, and swelling. STS is a widely used sclerosant agent which has been available in Canada and Europe for many years and is primarily used in the treatment of varicose veins. STS has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration FDA for sclerotherapy of varicose veins [17, 18].

In this case series, our clinical experience with the use of STS 3 % solution tends to validate STS as a minimally invasive, safe, and effective treatment of head and neck VnM. The responses to therapy were very satisfactory in 61.6 % of the treated patients who showed good to complete response. The best response to STS injection was demonstrated clearly in VnM smaller than 2.5 cm due to the fact that the efficacy of the sclerosis depends on the caliber of the feeder vessels and the blood flow. Alternatively, the lower efficacy of sclerotherapy of larger caliber or faster flow lesions was seen as a result of less sclerosant agent making contact with the endothelial cells of the lesional walls. The conclusions for this study are consistent with the previous literature in which the best results were obtained with low volume lesions. Stimpson et al. [21] used 3 % STS foam to treat 12 patients who had VnM in the head and neck. They found that a single treatment may be adequate for small lesions, but the injections may be safely repeated until a satisfactory result is obtained in large lesions.

The patients in this case series were treated in an office setting without any radiological guidance. Similarly, Khandpur et al. [19] reported 90–100 % regression in the size of lesions by direct intralesional injection of 3 % STS without radiological guidance into VnM and lymphatic malformations (Table 3).

Table 3.

Review of studies examined the role of percutaneous and per-mucosal intralesional STS injection alone of venous malformations of head and neck

| Studies | Sclerosant agent | Number of patients | Average age | Median and range of follow-up duration | Average no. of injection | Type of study (controlled vs. uncontrolled) | Method of drug preparation (foaming vs. direct) | Results | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kok 2012 (21) | 3 % STS | 51 | 10.9 | 2.7 years | 1.45 | Retrospective uncontrolled | Foaming | 23 % excellent results 60 % improved | Skin necrosis |

| Stimpson, 2012 (20) | 3 % STS | 12 | 7 | 28 months | 4 | Retrospective uncontrolled | Foaming | 33 % complete resolution improve 50 % | Minor bleeding |

| Bajpai 2012 (23) | 3 % STS | 8 | 15 | 2–3 years | 5 | Prospective comparative | Direct | Overall RR: 62.5 % | Blister, ulcer |

| Siniluoto TM 1997 (8) | 33–67 % STS mixed with CM | 38 | 28 | NR | 2.2 | Uncontrolled | Direct | Excellent or good in 23 patients (68 %) | Edema, infection, scarring and transient facial nerve paresis |

| O’Donovan 1997 (24) | 3 % STS | 5 | NR | 24 months | NR | Retrospective | Direct | Improve | NR |

| Current study | 3 % STS | 13 | 18.2 | 6.6 months | 3.1 | Prospective case studies | Direct | Complete resolution in 30.8 % and improvement in 61.6 % | Pain, edema, ulceration and ecchymosis |

NR not reported

The findings of this case series demonstrated excellent to good results in 61.6 % of the patients, and moderate to mild results in 30.8 % of the patients with direct percutaneous and permucosal intralesional injections of the 3 % STS solution. In this series, one patient who was previously treated by intralesional steroid injections showed no response to therapy; these results were comparable to those results which were obtained from the use of a foam technique (Tessari’s method) [20] in which the sclerosing agent foam was formed using a three-way stopcock and two syringes, mixing air with liquid sodium tetradecyl sulfate to create a foam. The optimal formulation was found to be one part sclerosant solution to four parts air. The aim of this method was to verify the safety, feasibility, and efficacy of different doses and concentrations of a sclerosing drug; variations in the preparation of the foam according to several variables, such as dilution, and volume of syringes. The concentrations used ranged from 0.1 to 3 % of STS depending on the caliber of the veins, with the larger caliber lesion, the higher concentration of STS used. The advantage of this method is minimal extravasation of sclerosant foam making it less harmful than the liquid solutions. Tessari’s foaming method had been originally used for sclerotherapy of varicose veins of lower limbs where increased hydrostatic pressure might enhance extravasation of the sclerosant agent. Foaming reduces extravasation related side effects and provides sclerosant rich milieu resulting in severe intimal damage. From the authors’ perspective however, foaming is not required in preparation of a sclerosant agent for head and neck low flow VM due to relatively low hydrostatic pressure in the head and neck vessels compared to lower limb vessels. Furthermore, to provide a sclerosant-rich milieu inside the lesions, our approach was to increase the concentration of the injected drug and the application of a compression dressing after intralesional injection.

Follow up of the patients was scheduled every 2 weeks and repeated injections were scheduled after 4 weeks in those patients with unsatisfactory results. Four of the patients in this series had two or more repeated injections. The results were monitored by clinical observation, documented and compared by serial photographs as well as clinical measurements. Unfortunately, the continuity of treatment varied among patients due to limited availability of the sclerosant agent, poor patient compliance with the regular follow up, and in some cases the patient’s satisfaction with their results.

In the present study, the reported side effects were mild in nature and healed spontaneously. In this series, no serious complications occurred such facial nerve palsy [8] and blindness [7] which have been reported by others. Post injection inflammatory reactions and pain were recorded in all patients. One patient developed a small ulceration at the injection site and another patient developed ecchymosis. Soft-tissue swelling generally increases in the region of the malformation immediately after the injections. Subsequently, necrosis and inflammation induced by the sclerosis subsides with fibrous tissue formation, culminating in progressive reduction in the lesion size. The complete clinical effect of the therapy may not be evident for several months. Patients and their families must be informed about these expected side effects and outcomes so the patient has realistic expectations.

Conclusion

Sclerotherapy with direct intralesional injection of 3 % STS solution is simple, safe, and effective therapy for managing head and neck VnM that can be done as an office procedure. Smaller lesions have a more favorable response. Further controlled studies need to be performed to determine the overall efficacy of STS in the management of VnM of the head and neck, as well as long term follow-up to observe results.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Ariadne E. González BS for her expert assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Requena L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous vascular anomalies. Part I. Hamartomas, malformations, and dilation of preexisting vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(4):523–549. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(97)70169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitehead KJ, Smith MC, Li DY. Arteriovenous malformations and other vascular malformation syndromes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3(2):a006635. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burrows PE, Mulliken JB, Fellows KE, Strand RD. Childhood hemangiomas and vascular malformations: angiographic differentiation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;141(3):483–488. doi: 10.2214/ajr.141.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi K, Nakao K, Kishishita S, Tamaruya N, Monobe H, Saito K, et al. Vascular malformations of the head and neck. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2013;40(1):89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naouri M, Schill T, Maruani A, Bross F, Lorette G, Rossler J. Successful treatment of ulcerated haemangioma with propranolol. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(9):1109–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Storch CH, Hoeger PH. Propranolol for infantile haemangiomas: insights into the molecular mechanisms of action. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(2):269–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siniluoto TM, Svendsen PA, Wikholm GM, Fogdestam I, Edstrom S. Percutaneous sclerotherapy of venous malformations of the head and neck using sodium tetradecyl sulphate (sotradecol) Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1997;31(2):145–150. doi: 10.3109/02844319709085481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee CH, Chen SG. Direct percutaneous ethanol instillation for treatment of venous malformation in the face and neck. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58(8):1073–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scherer K, Waner M. Nd:yAG lasers (1,064 nm) in the treatment of venous malformations of the face and neck: challenges and benefits. Lasers Med Sci. 2007;22(2):119–126. doi: 10.1007/s10103-007-0443-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornelis F, Neuville A, Labreze C, Kind M, Bui B, Midy D et al (2012) Percutaneous cryotherapy of vascular malformation: initial experience. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Angiodynamics (2008) Sotradecol. In: Angiodynamics (ed). Queensbury

- 12.Pharmaceuticals S. (2012) Fibero-Vein. In: Pharmaceuticals S (ed). Hereford

- 13.Odeyinde SO, Kangesu L, Badran M. Sclerotherapy for vascular malformations: complications and a review of techniques to avoid them. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66(2):215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Candamourty R, Venkatachalam S, Babu MR, Reddy VK. Low flow vascular malformation of the buccal mucosa treated conservatively by sclerotherapy (3% sodium tetradecyl sulfate) J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2012;3(2):195–198. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.101921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frullini A. New technique in producing sclerosing foam in a disposable syringe. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26(7):705–706. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng JW, Yang XJ, Wang YA, He Y, Ye WM, Zhang ZY. Intralesional injection of Pingyangmycin for vascular malformations in oral and maxillofacial regions: an evaluation of 297 consecutive patients. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(10):872–876. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan KT, Kirby J, Rajan DK, Hayeems E, Beecroft JR, Simons ME. Percutaneous sodium tetradecyl sulfate sclerotherapy for peripheral venous vascular malformations: a single-center experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18(3):343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2006.12.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dietzek CL. Sclerotherapy: introduction to solutions and techniques. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2007;19(3):317–324. doi: 10.1177/1531003507305884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khandpur S, Sharma VK. Utility of intralesional sclerotherapy with 3% sodium tetradecyl sulphate in cutaneous vascular malformations. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(3):340–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tessari L, Cavezzi A, Frullini A. Preliminary experience with a new sclerosing foam in the treatment of varicose veins. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27(1):58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stimpson P, Hewitt R, Barnalle A, Roebuck DJ, Hartley B (2012) Sodium tetradecyl sulfate sclerotherapy for treating venous malformations of the oral and pharygeal regions in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 76(4):569–573 [DOI] [PubMed]