Abstract

This work proposes the exploitation of under-utilized, non-expensive rapeseed press-cake as a source for producing high yield of protein, having superior whiteness and emulsion properties, and reduced level of residual phytate content. The chosen response parameters are relevant to food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries. Improvement in functional properties (emulsion properties) along with reduction in dark colour and toxic phytic acid level is expected to make rapeseed protein safer and commercially more viable for various applications. A multi-objective optimization technique based on Response surface methodology (RSM) has been presented. Using Derringer function, an optimum and feasible experimental condition was obtained with high composite desirability. The calculated regression model proved suitable for the evaluation of extraction process, whose adequacy was confirmed by Anderson-Darling Normality tests, Relative Standard Error of the Estimate (RSEE) and also by means of additional experiments performed at derived feasible experimental condition. The proposed simple alkaline protein extraction process, from defatted partially dephenolized rapeseed meal, under feasible optimal condition, was found to be suitable and potent for the recovery of high-quality vegetable protein.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13197-014-1299-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Rapeseed press-cake, Response Surface Methodology, Multiple responses, Protein

Introduction

Currently rapeseed ranks the third leading source of oil meal (after soy and cotton). The under-utilized meal or cake, the solid waste remaining after cold pressing of rapeseed to produce vegetable oil, is being generated in bulk quantity from oil processing industries. Isolation of valuable materials from this waste, such as protein, is crucial for its optimal use. In the course of harnessing this industrial waste, its protein production volume (overall yield), consumer relevance, possible technical application and associated harmful compounds derived along with protein (if any), are pertinent for food or pharmaceutical or any other related industries. The recuperation of proteins present in rapeseed meal, making it feasible for use in human food, is important due to its balanced amino acids composition (Sadeghi et al. 2006), and excellent techno-functional properties which are comparable with those of soy, sunflower and other leguminous proteins (Dong et al. 2011). However compared to soy protein industry, the rapeseed/canola protein has not had as much opportunity or volume to develop, mainly due to its poor dark brown-black appearance, caused by association of oxidized or polymerized polyphenolic compounds with protein, especially during conventional alkaline extraction. In this connection, several attempts have been made for the production of oilseed protein with reduced colour, using membrane-based extraction, ultrafiltration, diafiltration, ion-exchange and protein micellar mass methods (Bérot et al. 2005; Xu et al. 2003). However, all these processes failed to make any noticeable improvement in either the colour of the isolate or the protein content (Marnoch and Diosady 2006). An effective search for efficient and cheap means for obtaining light-coloured rapeseed protein still remains a challenge.

For rapeseed protein to occupy a good position in the commercial chain like other vegetable proteins, extraction steps need to be followed up and improved. As alkaline protein extraction is the most widely used technique among the authors, so simple feasible changes need to be incorporated in specific parts of the process. In particular, attention must be paid to those parts of the extraction protocol which may conceal sources of pitfalls, thereby deteriorating the product quality. In practice, attention is now being focused on the production and use of protein concentrates/isolates from partially dephenolized meal (González-Pérez et al. 2002) because recovery of vegetable proteins, devoid of co-extracted polyphenols, from the rapeseed/canola meal is not possible due to the strong covalent bond of polyphenol-protein complex (Xu and Diosady 2002). Also, very low level of polyphenol-protein complex seems to have beneficial effects in imparting superior techno-functional properties (Balange and Benjakul 2009; Rubino et al. 1996), without imparting much negative effect on the colour of the resulting protein concentrate/isolate. Perusal of literature reveals that variation of physicochemical parameters such as pH, ionic strength, temperature, extraction time and solid-to-liquid ratio influence protein extraction efficiency. There is a multitude of references related to the solubilisation of vegetable proteins in water or NaCl solution with widely varying pH levels (controlled by the addition of NaOH or HCl), with or without the presence of reducing agent such as sodium sulfite or ascorbic acid (Green 2006; Green et al. 2010). Although the effects of all those process parameters on protein extraction from different plant sources have been assessed separately, a systematic study of their concerted application is still lacking. Subsequent retrieval of protein by acidic isoelectric precipitation is very common. Recently, this traditional isoelectric precipitation method has been found to impart adverse effects on extraction yield (due to multiple isoelectric points of oilseed proteins) (Dong et al. 2011; Sadeghi et al. 2006) and on functional properties of the protein isolate (Liu et al. 2011). Therefore, protein recovery should be maximized by use of alternative precipitation methods in order to maximize the overall protein yield and its functional properties. In this perspective, protein precipitation by ammonium sulphate is preferable since it allows precipitation of maximum amount of dissolved proteins (Alsohaimy et al. 2007; Chen and Rohani 1992). It is also of particular interest in the field of proteomics, because this salt does not cause any adverse denaturation to the resulting isolate, thereby granting an extra asset to the product (Liu et al. 2011).

Only scant attention has been paid to the optimization of protein extraction from oilseed meal. When exploring the suitability of aforementioned factors for their potential use in rapeseed protein extraction, it would be rational to select an extraction system, which would efficiently extract high yield of whiter protein, having higher emulsification activity and lower phytate level. Protein emulsions are encountered in many areas including cosmetics, food, pharmaceutics, etc. Optimization of emulsification ability of a vegetable protein is advantageous because protein emulsions, due to their satisfactory stability over a certain storage time and high bioavailability, have attained particular interest as delivery systems for bioactive substances (Yin et al. 2012). Proteins are preferred over low molecular weight surfactants for emulsification purposes in foods (Damodaran 2005). Liu et al. (2011) showed that the peanut protein obtained during isoelectric precipitation gave poorer functional properties than those obtained by ammonium sulphate precipitation, particularly those related with emulsifying properties. Manamperi et al. (2011) optimized the effect of solubilisation and precipitation pH values on the yield and functional properties of canola protein isolate, wherein the authors found that emulsification property of canola protein is sensitive to solubilisation pH, giving better results at high alkaline pH. Nonetheless, no work has been reported regarding the emulsification properties of rapeseed protein, extracted using alkaline dissolution and ammonium sulphate precipitation. In the same way, optimization of extraction conditions for phytate reduction from rapeseed protein has also been overlooked. Presence of phytate in rapeseed and its products has greatly maligned its application as functional food additive. Phytate is present in canola meal at levels as high as 5–7 % (McCurdy 1990). Even if the work of Harland and Morris (1995) suggests that phytic acid may have some positive anticarcinogenic and antioxidant effects, it is also well established that phytic acid, being an anti-nutritional factor, acts as a strong chelator, forming protein and mineral-phytic acid complexes; the net result being reduced protein and mineral bioavailability. In addition, it inhibits the action of gastrointestinal tyrosinase, trypsin, pepsin, lipase and amylase (Akande et al. 2010). For reducing phytates from soy or rapeseed protein, few authors have suggested the use of ultrafiltration (Okubo et al. 1975), bipolar membranes electrodialysis (Ali et al. 2011) or phytase enzyme (Serraino and Thompson 1984); however application of enzymes or sophisticated membrane technologies at an industrial scale is challenging due to their high cost (Long et al. 2011). As such, it is of interest to develop alternative extraction process for the production of rapeseed protein with low phytic acid.

While numerous articles have mentioned the usefulness of rapeseed press-cake as a potent source of high-quality edible protein; but none of the study till date has proposed an optimization strategy for simultaneous improvement in yield, whiteness, phytate reduction as-well-as emulsification capacity of the recuperated protein. The present investigation attempts such a methodical approach.

Materials and methods

Materials

Rapeseed press-cake was procured from Assam Khadi and Village Industries Board, Guwahati, Assam, India. The press-cake was ground to pass through 60 mesh size sieve, and then stored at −18 °C for further analysis. All solvents and reagents were obtained from Merck® (India), of analytical grade. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was procured from Sigma Chemicals Co. (St. Louis, MO, US).

Preparation of defatted, partially dephenolized meal (treated meal)

Ground meal was defatted using hexane:diethyl ether (1:1 v/v) solvent mixture for reducing the lipid content to <0.1 % (by Soxhlet method). Since the dark colour of oilseed protein is mainly caused by its phenolic compounds, as a result of the removal of them the colour of the product is expected to become lighter. So, defatted meal was extracted with acidified methanol:acetone (1:1 v/v) mixture at a meal-to-solvent ratio of 1:20 (w/v) by mixing the suspension at 200 rpm for 2 h (at 25 °C) in an orbital shaker (Sartorius Stedin Biotech, CERTOMAT® IS). Suspension was then centrifuged (SIGMA 3–18 K Centrifuge) at 10,000 rpm for 20 min (at 4 °C), and the residue (treated meal) was dried in a vacuum oven under reduced pressure (150 mmHg) at 35 ± 2 °C for 42 h and was ground again to pass through a 60 mesh sieve to obtain fine powder and then stored at −18 °C until use.

Analyses

Relative protein yield

Rapeseed protein was extracted with selected 31 combinations of independent variables such as extraction time (1–5 h), solvent:meal ratio (10:1–30:1 v/w), NaCl concentration (0–0.2 M) and sodium sulfite concentration (0–0.4 %) as per CCD (Table 1). Meal extracts were prepared by constant mixing of treated meal-solvent mixture in an orbital shaker set at 200 rpm (25 °C). The solvent consisted of an alkaline solution of pH 11, to which sodium chloride and sodium sulfite were added at each of the indicated concentrations in the design (Mune et al. 2010; Wanasundara and Shahidi 1996). Subsequently, the slurry was centrifuged at 7,000 rpm for 20 min (at 4 °C). The supernatant was filtered and the volume of clarified extract was noted. Ammonium sulfate was added into the supernatant to 85 % saturation (Liu et al. 2011) and the mixture was kept in ice bath for 3 h with gentle stirring and then centrifuged at 9,000 rpm for 30 min (at 4 °C). The obtained protein precipitate was re-dispersed in Milli-Q water (Millipore Water Purification System, Model-Elix, USA), the dispersion was adjusted to pH 7 and dialyzed. A known aliquot of this protein solution was analyzed for protein content by the Lowry method, using BSA as standard. Relating the protein amount of the extract to that of the rapeseed meal used (44.8 % of dry matter, determined by Kjeldahl method), protein extractability was calculated as relative protein yield (%), as it is of importance in overall protein turn-over of the production process as a whole (Pickardt et al. 2009).

Table 1.

Central Composite design at various protein extraction conditions from rapeseed press-cake, defined through the independent variables along with the observed values of the dependent variables

| Std Order | Uncoded and coded (between parentheses) values of independent variables | Responses (dependent variables) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction time (h) (XA) | Solvent:meal ratio (vol/wt) (XB) | NaCl conc. (M) (XC) | Sodium sulfite conc. (%) (XD) | Relative protein yield (%) (Y1) | Whiteness Index (WStensby) (Y2) | Phytate content (mg Na-phytate equivalent/100 g protein) (Y3) | Emulsion capacity (%) (Y4) | Emulsion stability (%) (Y5) | |

| Factorial points | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 (−1) | 15 (−1) | 0.05 (−1) | 0.1 (−1) | 19.799 ± 0.528a | 51.730 ± 1.711a | 1.185 ± 0.117a | 47.986 ± 1.311a | 50.367 ± 1.264abf |

| 2 | 4 (+1) | 15 (−1) | 0.05 (−1) | 0.1 (−1) | 24.391 ± 0.248bc | 44.595 ± 0.276ab | 0.945 ± 0.115ab | 49.029 ± 1.373ac | 50.211 ± 1.117abf |

| 3 | 2 (−1) | 25 (+1) | 0.05 (−1) | 0.1 (−1) | 25.269 ± 0.049bc | 66.457 ± 2.400c | 0.649 ± 0.021bc | 46.972 ± 0.746a | 50.846 ± 1.549abf |

| 4 | 4 (+1) | 25 (+1) | 0.05 (−1) | 0.1 (−1) | 23.715 ± 0.311bcd | 65.214 ± 2.428c | 0.520 ± 0.051c | 48.389 ± 0.864ac | 48.824 ± 0.832ab |

| 5 | 2 (−1) | 15 (−1) | 0.15 (+1) | 0.1 (−1) | 23.123 ± 0.306cd | 46.710 ± 0.707ab | 1.024 ± 0.041ab | 48.279 ± 0.312a | 49.029 ± 1.373ab |

| 6 | 4 (+1) | 15 (−1) | 0.15 (+1) | 0.1 (−1) | 25.463 ± 1.151bc | 50.761 ± 1.725a | 1.063 ± 0.103abd | 50.693 ± 1.766ac | 55.662 ± 0.229c |

| 7 | 2 (−1) | 25 (+1) | 0.15 (+1) | 0.1 (−1) | 25.724 ± 0.157bc | 57.405 ± 1.181ad | 0.655 ± 0.035c | 52.530 ± 0.665b | 44.269 ± 1.118d |

| 8 | 4 (+1) | 25 (+1) | 0.15 (+1) | 0.1 (−1) | 26.322 ± 0.217b | 66.461 ± 0.524c | 0.551 ± 0.022c | 51.368 ± 1.601bc | 47.974 ± 1.294ae |

| 9 | 2 (−1) | 15 (−1) | 0.05 (−1) | 0.3 (+1) | 19.779 ± 0.500a | 56.885 ± 2.737a | 1.067 ± 0.057ab | 48.529 ± 0.666a | 47.250 ± 1.061ae |

| 10 | 4 (+1) | 15 (−1) | 0.05 (−1) | 0.3 (+1) | 21.268 ± 1.606ad | 40.935 ± 3.599b | 0.706 ± 0.011bc | 51.317 ± 1.280bc | 45.229 ± 1.424de |

| 11 | 2 (−1) | 25 (+1) | 0.05 (−1) | 0.3 (+1) | 31.258 ± 0.200f | 64.470 ± 1.287cd | 0.458 ± 0.082c | 47.559 ± 0.957a | 49.279 ± 0.312ab |

| 12 | 4 (+1) | 25 (+1) | 0.05 (−1) | 0.3 (+1) | 23.861 ± 1.281bc | 61.565 ± 1.167cd | 0.561 ± 0.048c | 49.445 ± 0.786abc | 47.353 ± 0.915ae |

| 13 | 2 (−1) | 15 (−1) | 0.15 (+1) | 0.3 (+1) | 23.334 ± 0.573ce | 55.015 ± 0.417a | 0.822 ± 0.099bc | 47.083 ± 0.589a | 50.677 ± 1.789abf |

| 14 | 4 (+1) | 15 (−1) | 0.15 (+1) | 0.3 (+1) | 22.735 ± 0.280ce | 52.890 ± 0.863a | 0.831 ± 0.144bc | 47.353 ± 0.915a | 52.655 ± 0.842f |

| 15 | 2 (−1) | 25 (+1) | 0.15 (+1) | 0.3 (+1) | 33.380 ± 0.883f | 55.795 ± 4.702a | 0.531 ± 0.009c | 47.222 ± 0.786a | 48.595 ± 1.155ab |

| 16 | 4 (+1) | 25 (+1) | 0.15 (+1) | 0.3 (+1) | 24.475 ± 0.000bc | 63.790 ± 4.667cd | 0.566 ± 0.095c | 45.903 ± 0.491a | 50.000 ± 0.000abf |

| Axial points | |||||||||

| 17 | 1 (−24/4) | 20 (0) | 0.10 (0) | 0.2 (0) | 26.843 ± 2.427bc | 58.310 ± 2.999a | 0.753 ± 0.153bc | 47.404 ± 0.489a | 47.418 ± 0.508ae |

| 18 | 5 (+24/4) | 20 (0) | 0.10 (0) | 0.2 (0) | 26.452 ± 0.904bc | 59.405 ± 1.577cd | 0.752 ± 0.028bc | 48.421 ± 1.489ac | 49.389 ± 0.864ab |

| 19 | 3 (0) | 10 (−24/4) | 0.10 (0) | 0.2 (0) | 20.614 ± 0.674ae | 39.322 ± 0.916b | 1.618 ± 0.069d | 48.029 ± 1.373a | 51.316 ± 0.136bf |

| 20 | 3 (0) | 30 (+24/4) | 0.10 (0) | 0.2 (0) | 27.233 ± 0.145b | 66.145 ± 1.266d | 0.566 ± 0.038c | 48.945 ± 0.079ac | 50.389 ± 0.550bf |

| 21 | 3 (0) | 20 (0) | 0.00 (−24/4) | 0.2 (0) | 25.409 ± 0.048bc | 60.460 ± 1.570cd | 0.578 ± 0.126c | 47.974 ± 1.294a | 49.333 ± 0.471ab |

| 22 | 3 (0) | 20 (0) | 0.20 (+24/4) | 0.2 (0) | 25.923 ± 1.164bc | 54.815 ± 4.448a | 0.711 ± 0.037bc | 49.065 ± 1.174ac | 49.487 ± 0.019ab |

| 23 | 3 (0) | 20 (0) | 0.10 (0) | 0.0 (−24/4) | 24.278 ± 0.521bc | 63.810 ± 2.475cd | 0.803 ± 0.137bc | 54.905 ± 1.078b | 48.059 ± 0.000ab |

| 24 | 3 (0) | 20 (0) | 0.10 (0) | 0.4 (+24/4) | 25.053 ± 1.900bc | 60.670 ± 3.239cd | 0.462 ± 0.126c | 51.905 ± 1.196bc | 48.677 ± 0.624ab |

| Centre points | |||||||||

| 25 | 3 (0) | 20 (0) | 0.10 (0) | 0.2 (0) | 26.055 ± 0.552bc | 59.196 ± 1.843cd | 0.629 ± 0.073c | 47.529 ± 0.666a | 49.398 ± 1.894ab |

| 26 | 3 (0) | 20 (0) | 0.10 (0) | 0.2 (0) | 26.435 ± 1.691bc | 56.904 ± 0.663ad | 0.748 ± 0.100bc | 47.529 ± 0.666a | 50.471 ± 0.666abf |

| 27 | 3 (0) | 20 (0) | 0.10 (0) | 0.2 (0) | 26.686 ± 1.205b | 58.154 ± 2.212ad | 0.636 ± 0.079c | 47.105 ± 1.265a | 49.431 ± 0.963ab |

| 28 | 3 (0) | 20 (0) | 0.10 (0) | 0.2 (0) | 25.330 ± 1.383bc | 57.926 ± 2.138ad | 0.699 ± 0.053bc | 47.471 ± 2.080a | 49.389 ± 0.864ab |

| 29 | 3 (0) | 20 (0) | 0.10 (0) | 0.2 (0) | 26.532 ± 0.742bc | 56.398 ± 3.138ad | 0.592 ± 0.021c | 47.654 ± 0.842a | 48.252 ± 0.273ab |

| 30 | 3 (0) | 20 (0) | 0.10 (0) | 0.2 (0) | 27.091 ± 0.307b | 57.992 ± 1.472ad | 0.618 ± 0.138c | 47.333 ± 0.943a | 48.240 ± 0.256ab |

| 31 | 3 (0) | 20 (0) | 0.10 (0) | 0.2 (0) | 27.076 ± 1.345b | 56.560 ± 1.165ad | 0.653 ± 0.214c | 47.597 ± 1.630a | 49.706 ± 0.416abf |

Duplicate set of each experimental run was performed and analyzed twice (i.e. n = 2 × 2 = 4). Values are means ± standard deviation of n = 4 analyses (subjected to Tukey test). Means with the same letter within one column were not statistically different (p > 0.05). Each experimental value after the 3rd decimal place has been rounded off

All factors were encoded (XA―XD), using −2 for the lowest level of a factor (−α) and +2 for the respective maximum (+α) with equidistant intermediate stages [XA = (Xt − 3)/1; XB = (Xs/m − 20)/5; XC = (XNaCl − 0.1)/0.05; ]

Whiteness index (based on Stensby formula)

All the precipitated protein isolates displayed a similar off-white colour. However, upon dissolution in water, their solutions showed light brown colours of different intensities; an observation that was consistent with previous report on canola protein isolates (Xu and Diosady 2002). Therefore, following the protocol of Xu and Diosady (2002), colorimetric evaluations were performed by scanning their aqueous solution.

Briefly, aliquots of different protein solutions were diluted with Milli-Q water to give a concentration of 2 mg/ml (determined by Lowry method), which was done so that same level of protein could be directly compared (Park and Bean 2003). Solutions were filled into a rectangular glass cell (6.5 cm length, 1 cm width, 6.5 cm height). The colour intensity of the sample was measured using Hunter Lab Colorimeter (Ultrascan, VIS-Hunter Associates Lab., USA), fitted with a large area port (2.5 cm diameter aperture). The instrument (including 65°/0° geometry, D25 optical sensor, 10° observer, specular light) was calibrated using white and black reference tiles provided by the manufacturer. Measurements of Hunter-L (absolute lightness = 100; absolute darkness = 0), Hunter-a (+a = redness; −a = greenness) and Hunter-b (+b = yellowness; −b = blueness) values were taken. The average of three measurements was taken. Whiteness Index proposed by Codex Alimentrius (WI = L − 3b) is biased on blue-yellow dimension. As such, it was calculated using Stensby equation (WStensby = L + 3a − 3b) (Zarubica et al. 2005).

Estimation of phytates

Definite aliquots of known protein concentration were used for phytate determination using Wade reagent, according to method described by Bhandari and Kawabata (2006). Results were expressed as sodium phytate equivalent in mg per 100 g protein.

Emulsion capacity and stability

Emulsion properties were studied according to the method described by Hassan et al. (2010).

Statistical analyses

Data from CCD were approximated to a second-order polynomial equation and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was generated. Statistical analysis was performed using STATISTICA (version 7, StatSoft, Oklahoma), MINITAB (version 15, Minitab Inc., US) and Design-Expert (version 6, Stat-Ease Inc., MI, USA) softwares. Effects of variables on responses were discussed by evaluation of one-factor plots, Response surface contour plots and Standardized Pareto charts. Relative standard error of the estimate (RSEE), observed between the experimental and predicted results was determined from Eq. (1).

| 1 |

where, Yexp and Ymod are the values obtained from experiments and from the model, respectively. n is the number of points at which measurements were carried out (Bup et al. 2009).

Result and discussion

Modeling the effects by Response Surface Regression Analysis (RSREG) and diagnostic checking of the fitted models

The CCD matrix and the response values obtained for the combination of 4-factors at 5-level each are given in Table 1. The estimated coefficients of each model are presented in Table 2. RSREG procedure was employed to fit the quadratic polynomial equation to the experimental data. To develop the fitted response surface model equations, all insignificant terms (p > 0.05) were eliminated and the fitted models are shown in Table 3. The high values of coefficient of determination (R2 and adjusted-R2) (>0.8) suggest that the quadratic models can explain most of variabilities in the observed data, and thus can be considered as valid models. Good correlation existed between observed and predicted values (Supplementary Fig. S1). All regression models were highly significant (p ≤ 0.000) and p-values for lack-of-fit test were large (p > 0.05), which prove that the models are adequate for predicting the responses. Only response Y4 (Emulsion capacity) showed R2 lesser than 0.8, which can be considered satisfactory for data of techno-functional properties (Tan et al. 2010). So, accuracy of the models was further evaluated by RSEE (Bup et al. 2009) and by a normality test (Anderson-Darling normality test) for error terms (Cho et al. 2005; Tabarestani et al. 2010) using standardized residuals of all dependent variables. Smaller Anderson-Darling (AD) values along with p-values greater than 0.05, indicate that the distribution fits the data better. The error terms of all dependent variables had the normal distribution in the Anderson-Darling normality test within 95 % prediction band (Supplementary Fig. S2), meaning that these models are sufficiently accurate for predicting the relevant response(s). Additionally, a model can be considered acceptable if RSEE is <10 %; this condition was also satisfied for all the responses (Table 3).

Table 2.

Regression coefficients for the response surface models in terms of coded and uncoded units, along with the associated probability (p value)

| Term | Y1 (Relative protein yield) | Y2 (WStensby) | Y3 (Phytate content) | Y4 (Emulsion capacity) | Y5 (Emulsion stability) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | ||||||

| Coded | Uncoded | Coded | Uncoded | Coded | Uncoded | Coded | Uncoded | Coded | Uncoded | ||||||

| Constant | 26.4577 | −18.9466 | 0.000* | 57.5898 | 28.6206 | 0.000* | 0.653470 | 4.61518 | 0.000* | 47.4599 | 43.1901 | 0.000* | 49.2693 | 54.1259 | 0.000* |

| Extraction time | −0.4275 | 9.30165 | 0.019* | −0.2528 | −12.6565 | 0.472 | −0.027117 | −0.37189 | 0.081 | 0.3903 | 2.8643 | 0.020* | 0.4806 | 1.70117 | 0.003* |

| Solvent:meal | 1.9728 | 2.16127 | 0.000* | 6.4700 | 3.56239 | 0.000* | −0.219066 | −0.25089 | 0.000* | 0.0394 | 0.02074 | 0.808 | −0.6581 | −0.37715 | 0.000* |

| NaCl | 0.6768 | 68.6734 | 0.000* | −0.5965 | −63.4765 | 0.094 | 0.009119 | −2.92019 | 0.552 | 0.1411 | 27.8880 | 0.387 | 0.4087 | −7.30883 | 0.011* |

| Sodium sulfite | 0.3264 | 20.9521 | 0.068 | −0.1778 | 37.1732 | 0.612 | −0.072168 | −2.07069 | 0.000* | −0.7015 | −17.3252 | 0.000* | −0.2045 | −28.8043 | 0.193 |

| Extraction time × Extraction time | −0.0537 | −0.05369 | 0.739 | 0.0544 | 0.054389 | 0.865 | 0.021068 | 0.021068 | 0.138 | −0.0289 | −0.0289 | 0.846 | −0.2156 | −0.21557 | 0.135 |

| Solvent:meal × Solvent:meal | −0.7349 | −0.02940 | 0.000* | −1.4765 | −0.05906 | 0.000* | 0.105970 | 0.004239 | 0.000* | 0.1147 | 0.00459 | 0.442 | 0.3966 | 0.01586 | 0.007* |

| NaCl × NaCl | −0.2991 | −119.622 | 0.068 | −0.2505 | −100.219 | 0.436 | −0.005891 | −2.35643 | 0.675 | 0.1228 | 49.1269 | 0.411 | 0.0360 | 14.4199 | 0.800 |

| Sodium sulfite × Sodium sulfite | −0.5493 | −54.9266 | 0.001* | 0.9001 | 90.0076 | 0.007* | −0.008879 | −0.88792 | 0.527 | 1.3441 | 134.413 | 0.000* | −0.2245 | −22.4539 | 0.120 |

| Extraction time × Solvent:meal | −1.5674 | −0.31347 | 0.000* | 2.1288 | 0.425762 | 0.000* | 0.028751 | 0.005750 | 0.130 | −0.3558 | −0.0712 | 0.078 | −0.3294 | −0.06588 | 0.089 |

| Extraction time × NaCl | −0.2311 | −4.62122 | 0.286 | 2.8881 | 57.7612 | 0.000* | 0.037778 | 0.755561 | 0.048* | −0.4332 | −8.66484 | 0.034* | 1.2405 | 24.8093 | 0.000* |

| Extraction time × Sodium sulfite | −1.3368 | −13.3681 | 0.000* | −1.1070 | −11.0700 | 0.013* | 0.013903 | 0.139033 | 0.459 | −0.0055 | −0.05507 | 0.978 | −0.5452 | −5.45208 | 0.006* |

| Solvent:meal × NaCl | −0.2263 | −0.90520 | 0.296 | −1.5929 | −6.37150 | 0.001* | 0.017430 | 0.069718 | 0.355 | 0.5070 | 2.02781 | 0.014* | −1.2769 | −5.10747 | 0.000* |

| Solvent:meal × Sodium sulfite | 1.1002 | 2.20050 | 0.000* | −1.3653 | −2.73063 | 0.002* | 0.033267 | 0.06653 | 0.081 | −0.4641 | −0.92817 | 0.023* | 0.7984 | 1.59686 | 0.000* |

| NaCl × Sodium sulfite | 0.0189 | 3.77218 | 0.930 | 0.6434 | 128.688 | 0.138 | −0.002179 | −0.43589 | 0.907 | −1.2363 | −247.264 | 0.000* | 1.0080 | 201.600 | 0.000* |

*Significant at p < 0.05

Table 3.

Response surface models for extracting protein from defatted partially dephenolized rapeseed meal

| Response | Quadratic polynomial model (coefficients in uncoded units) | p | R2 | R2 (predicted) | R2 (adjusted) | Lack-of-Fit (p value) | RSEE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative protein yield (%) | 0.000 | 0.86859 | 0.7494 | 0.82945 | 0.241 | 3.51999 | |

| Whiteness Index (WStensby) | 0.000 | 0.91327 | 0.8306 | 0.88743 | 0.088 | 2.95625 | |

| Phytate content (mg Na-phytate equivalent/100 g protein) | 0.000 | 0.86923 | 0.7561 | 0.83027 | 0.428 | 9.08175 | |

| Emulsion capacity (%) | 0.000 | 0.78563 | 0.5900 | 0.72178 | 0.155 | 1.72419 | |

| Emulsion stability (%) | 0.000 | 0.80869 | 0.6475 | 0.75171 | 0.503 | 1.70378 |

Effects of the extraction factors on the responses: Standardized Pareto chart, one-factor and contour plots analyses

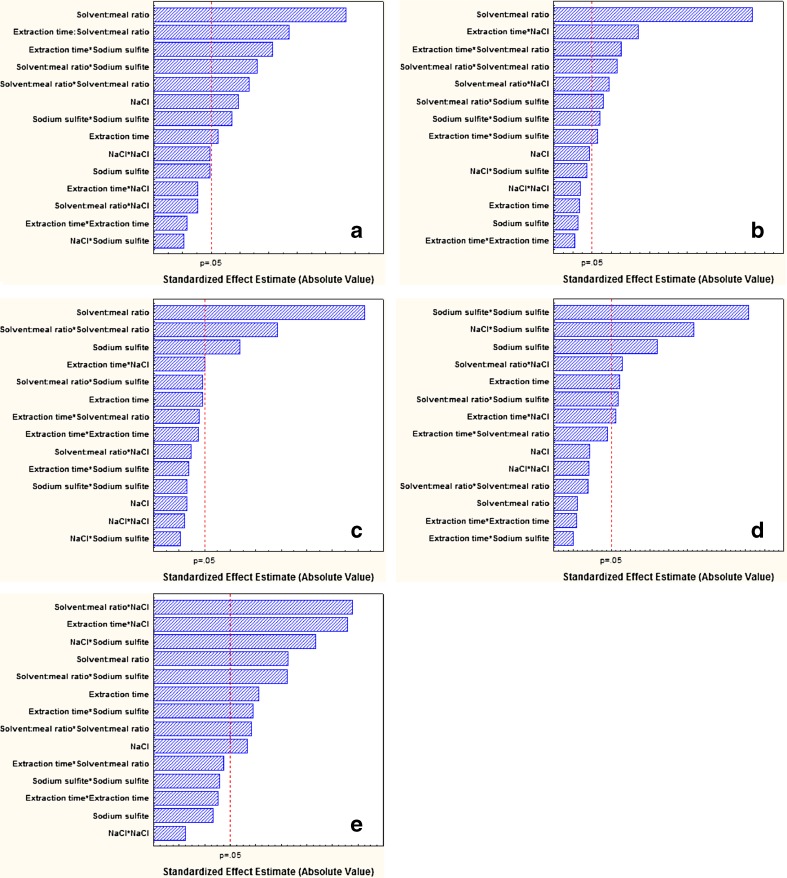

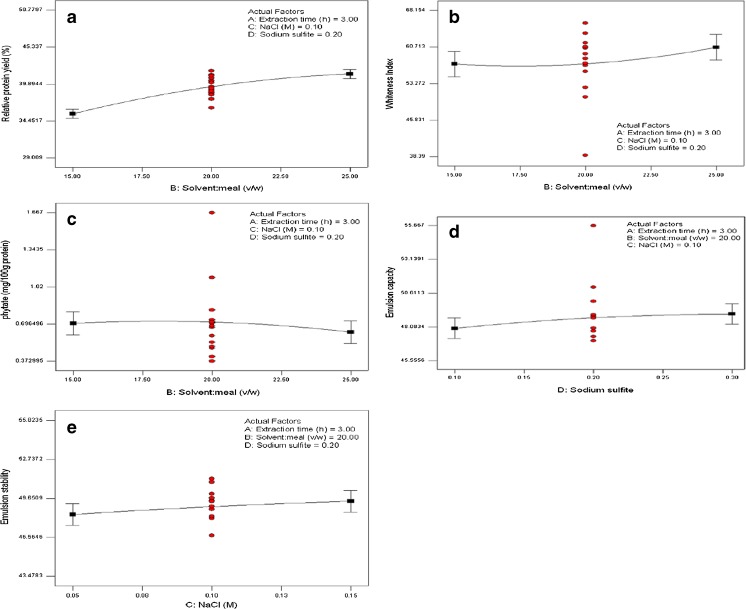

Among the factors studied, the solvent:meal ratio had the highest impact on Relative protein yield (factor contribution = 22.3 %), WStensby (35 %) and phytate content (35 % by linear term; 19.6 % by quadratic term) of the recuperated protein (Fig. 1a–c). This factor had a more limited influence on emulsion stability (9.47 % by linear term; 6.23 % by quadratic term) (Fig. 1d) and least on emulsion capacity (quadratic term contribution = 2.28 %; linear term contribution = 0.72 %) (Fig. 1e). Solvent:meal ratio (both linear and quadratic terms) showed a significant effect on all the evaluated parameters, except emulsion capacity. The yield and whiteness increased profoundly with increasing solvent:meal ratio (Fig. 2a–b). Solvent:meal ratio has been reported as one of the prime factor affecting protein yield from various plant sources. When the percentage of solvent in a solid–liquid reaction system increases, the reaction proceeds as a result of liquid diffusing, or otherwise penetrating into the interior of the reacting solid. The availability of more liquid increases the driving force of protein out of the meal (Koocheki et al. 2009), and hence the yield increases. Within the experimental region, relative protein yield ranged from 19.4 to 34 %, which is much higher than the overall rapeseed protein yield (≈28 %) reported by Manamperi et al. (Manamperi et al. 2011). Thus, we were successful in optimizing and increasing the overall protein yield from rapeseed meal better than those reported by earlier authors. The dissolved pigments (polyphenols) in higher solvent-to-solid ratio, did not reach to the saturation level and thus the colour parameters (whiteness) seemed to improve (Koocheki et al. 2009). Another probable reason for less development of colour in proteins extracted at high solvent:meal ratio may be that the colour-forming polymeric phenols such as tannins are hydrophobic in nature and less extracted from meal in presence of high water content (Karacabey and Mazza 2010; Xu 1999).

Fig. 1.

Pareto charts for the standardized main and interactions in the central composite design for the a Relative protein yield, b WStensby, c phytate content, d Emulsion capacity, and e Emulsion stability. Vertical dotted line indicates the statistical significance (p = 0.05) of the effects

Fig. 2.

One factor plot showing the main effect of a solvent:meal ratio on Relative protein yield, b solvent:meal ratio on WStensby, c solvent:meal ratio on phytate content, d sodium sulfite on Emulsion capacity, and e NaCl on Emulsion stability

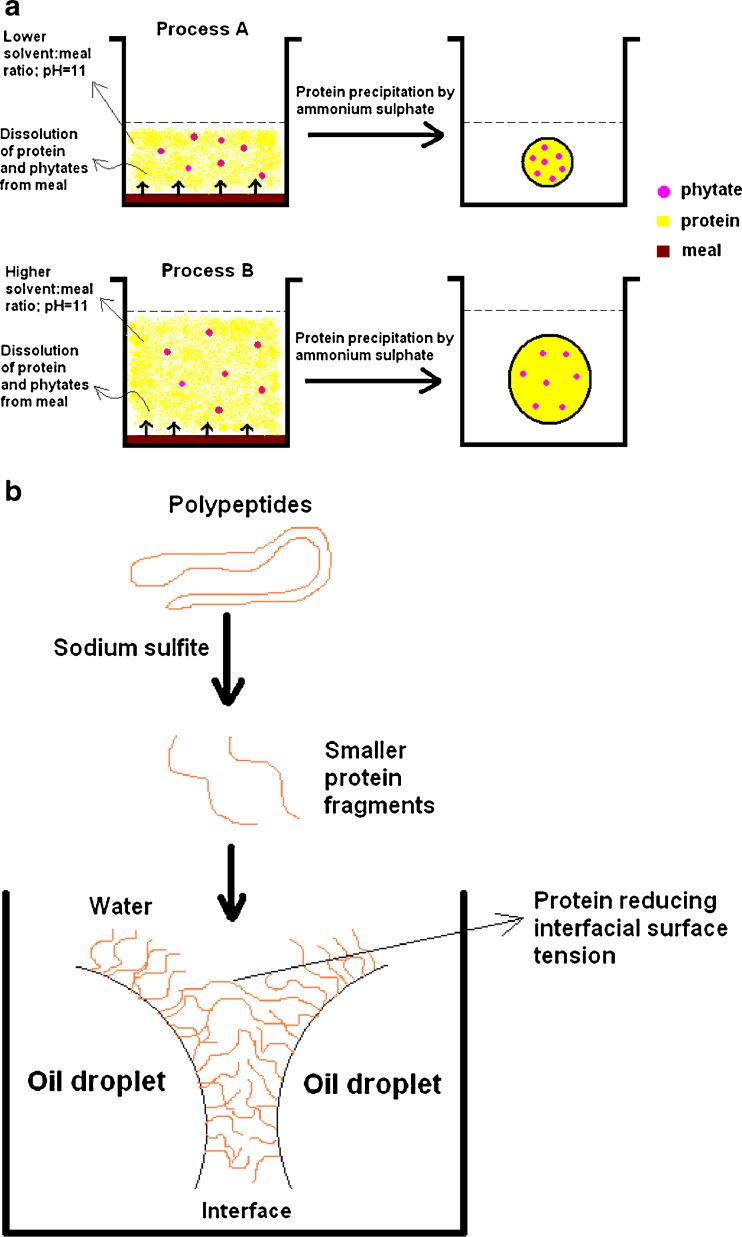

The greatest effect of solvent:meal ratio was on phytate content, which can be attributed to the higher solubility of phytates in water. Maga (1982) considered phytates as an impurity in the isolation of protein and stated that when isolation of protein by means of isoelectric precipitation is used, a certain amount of phytates would also precipitate with the protein; extend of binding increases with decreasing pH, especially in low acid pH. Generally binding of phytate with protein at high alkaline pH is very less or negligible (Maga 1982). In the current investigation, the use of high alkaline pH might have resulted in lesser leaching of phytates from the meal, and hence accounts for lower presence of phytate in the resulting protein. During recuperation of protein, the added ammonium sulphate did not make the solution acidic and as such, less phytates from the extractant solution might have precipitated along with the protein. This recommends a clear advantage of using ammonium sulphate precipitation over isoelectric precipitation. Figure 2c indicates that increase in solvent:meal ratio decreases the phytate content in the protein. This observation can be explained by the following example (Fig. 3a): Pictorially, let us consider two extraction processes from this study: one process having lower solvent:meal ratio (A) and the other having higher solvent:meal ratio (B). The remaining three extraction factors are held constant at their zero level of CCD matrix. Since the extractability of phytates from the meal is known to be dependent on the pH of the solution (Maga 1982), which is constant (pH 11) in both the processes, we can presume that a definite quantity of phytates (say ‘x’ moles) will leach out at constant pH, in both A and B. However, higher solvent:meal ratio will result in more protein dissolution i.e., protein yield will be higher in B (‘y’ moles) than A (‘z’ moles) (i.e., y > z). After recuperation of protein by ammonium sulphate, the amount of phytates precipitated with protein of unit mass, will differ in two processes; explicitly, the phytate content present in per mg of protein extracted in process A, will be higher than that present in per mg of protein extracted in process B. Thus, the protein extracted at higher solvent:meal ratio, will tend to have lesser phytate. Few workers (Serraino and Thompson 1984) have suggested the use of salts like NaCl or CaCl2 or both in extraction medium for reducing phytates from vegetable proteins. Although NaCl is being used in the current investigation, it failed to show any significant effect (p > 0.05) on the phytate level, probably due to very low concentration of NaCl investigated herein. Ca2+ ions can induce phytate dissociation only at low pH (Maga 1982), meanwhile higher concentration of NaCl may reduce the protein yield by causing salting out effect (Pickardt et al. 2009). Hence, these parameters were not tested.

Fig. 3.

a Diagrammatic illustration showing the plausible mechanism and the role of extraction parameters in reducing phytate level in precipitated protein, and b A diagram to explain the role of protein in oil–water emulsion

Presence of sodium sulfite in the extraction medium had the second greatest impact. This is evident from the high impact that this factor had on emulsion capacity (26.77 % by quadratic term; 12.8 % by linear term) and phytate content (12.21 %) (Fig. 1c–d). The interaction term of sodium sulfite and solvent:meal also showed good influence on relative protein yield (10.15 %) and WStensby (6.07 %) (Fig. 1a–b). This is because sulphite helps in enhancing protein solubilisation (Adel et al. 1981; Liadakis et al. 1998) and also prevents oxidation of polyphenols, and thus limits reactions between proteins and oxidized polyphenols that are responsible for dark colour formation (Lqari et al. 2002).

The impact of NaCl was found to be comparatively low; but it significantly affected the yield (7.65 %). Addition of salts enhances protein extractability due to the increase of ionic force promoted by the added NaCl mainly on globulin protein of oilseeds (Pickardt et al. 2009). The predominant effect of salts can be seen on emulsion properties (Fig. 2d–e). Protein acts as a macromolecular surfactant by adsorbing to and orienting itself at the oil–water interface, in such a way that its non-polar (hydrophobic) segment is partitioned into the oil phase and its hydrophilic segment exposed to the aqueous phase. In this regard, small molecular-weight surfactants usually perform better than macromolecular surfactants, owing to their high diffusivity. This might be the plausible reason for the increase in emulsion capacity with increasing concentration of Na2SO3 (Fig. 2d). This is because Na2SO3 is known for its innate quality of breaking up certain disulfide linkages in protein molecules (Kim et al. 2000; Li et al. 2012). These smaller fragments of protein then easily orient themselves at the newly created interfaces during emulsification process (Fig. 3b). It is worth to note that linear or quadratic term of Na2SO3 did not play a significant role in emulsion stability (Fig. 1e). This changed behaviour can be explained by the fact that Na2SO3 give rise to small molecular protein fragments, which in-turn can easily form emulsion; however large-sized protein-stabilized emulsions are generally more stable than those formed by smaller surfactants, due to their ability to form a strong visco-elastic film around oil droplets via non-covalent interactions, and the arrangement of the protein chain configurations in the form of “loops and trains” in the film, introduce additional forces that help formation of stable emulsion (Damodaran 2005). In other words, when a protein contains sulfhydryl and disulfide groups, conformational changes in the protein at the interface promote polymerization via the sulfhydryl-disulfide interchange reaction (Fig. 3b). This steric force, which is a major factor against droplets coalescence (related to emulsion stability) does not exist in emulsions created by smaller protein fragments or surfactants (Damodaran 2005).

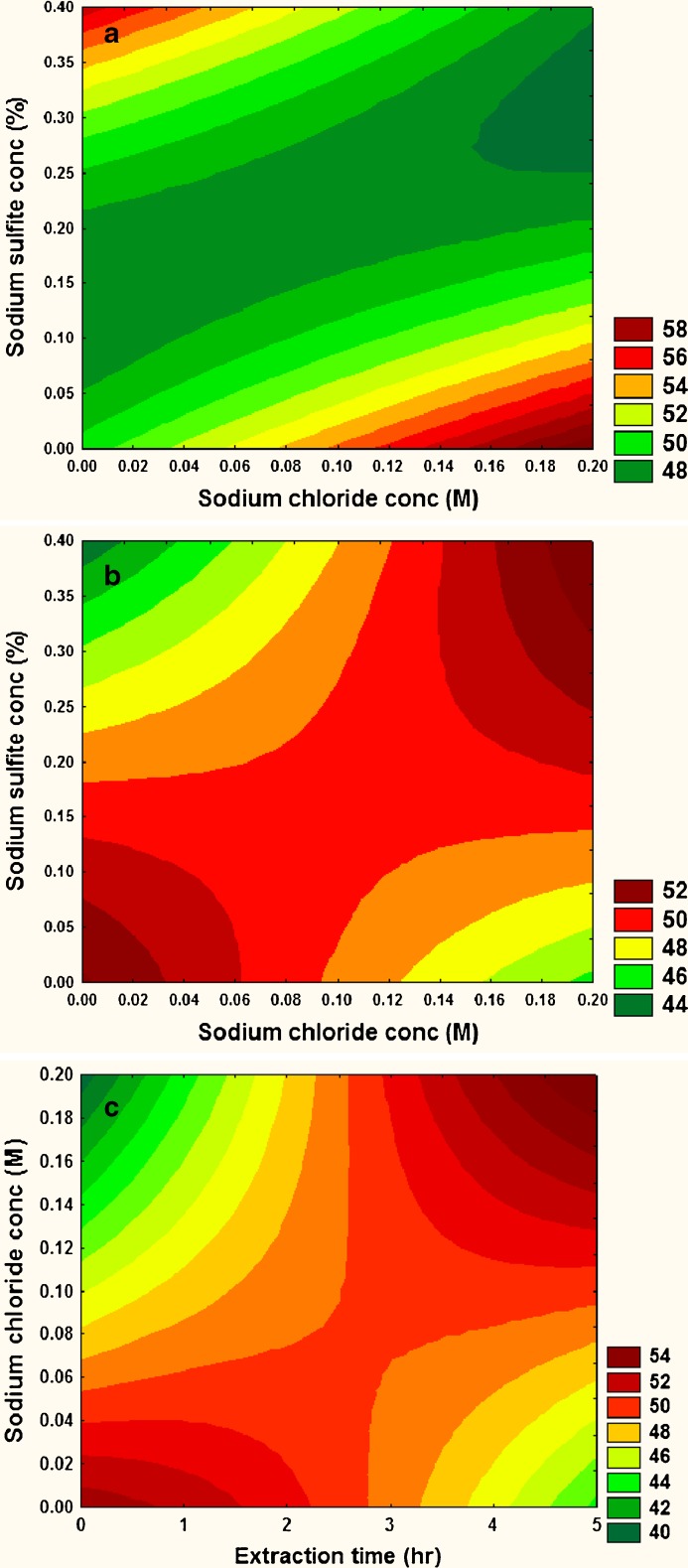

The role of interaction term is more evident on emulsification properties (Fig. 1d–e). The interaction between Na2SO3 and NaCl and its effect on emulsion capacity is shown in Fig. 4a. Increase in Na2SO3, albeit in presence of lower concentration of NaCl, tends to increase the emulsion capacity of the extracted protein. This may be attributed to the formation of smaller protein fragments by Na2SO3, as explained above. This explanation may also be the probable reason for the enhanced emulsion stability observed in Fig. 4b, especially in presence of low Na2SO3 concentration. Rapeseed storage proteins contain two major fractions: globulin and albumin. During emulsification, the protein components of the mixture adsorb preferentially to the interface. The composition of the protein film formed at the interface is dependent on relative surface activities of various protein components of the mixture. Compact and highly ordered proteins possess poorer surface activity and emulsifying activity (Damodaran 2005). Incidentally, the presence of salts like NaCl in the extractant, favours the dissolution of globulin protein from the meal. In rapeseed, globulin is larger, has less rigid structural integrity and exhibit greater decrease in interfacial surface tension, compared with the albumin (Krause and Schwenke 2001). So, it can be inferred that the presence of globulin constituent in protein isolate favours the formation and stability of emulsion, and this above-described principle aptly explains the enhanced emulsion properties at higher NaCl concentration. This rationalization may be partly extended to the observed emulsion stability at higher concentration of NaCl and extended extraction time (Fig. 4c). Long extraction duration supports the dissolution of non-protein soluble components like polysaccharides, lignin, etc. from the meal along with protein under alkaline condition. These polysaccharides complexes with NaCl-extracted globulin rich protein isolate, at the interface, enabling the formation of stable emulsion. This result corroborates with the findings of Harnsilawat et al. (2006).

Fig. 4.

Estimated contour plots for the effect of a NaCl and sodium sulphite on Emulsion capacity, b NaCl and sodium sulphite on Emulsion stability, and c NaCl and extraction time on Emulsion stability

Conditions for optimum responses

The model proposed for each response Y is given as:

| 2 |

where b0 is the offset term; b1, b2, b3 and b4 are related to the linear terms; b5, b6, b7 and b8 are connected to the quadratic effects; b9, b10, b11, b12, b13, b14 are associated with the interaction effects. To optimize the process, the optimum point for each response of Eq. (2) was defined as the point where the first partial derivative of the function equals zero (Bup et al. 2009; Peričin et al. 2008; Quanhong and Caili 2005).

| 3 |

Thus, using the partial derivatives of regression equation of each response, given in Table 3, optimal condition of each dependent variable was obtained and the results are given in Table 4. Though the critical values of four independent variables for all five responses ranged within the experimental region, except XD value of Y2 response (beyond α value), the suggested optimal conditions showed considerable differences among the four responses (Table 4). Thus, unlike Cho et al. (2005) solutions from partial derivatives of polynomial regression equations did not present a reasonable alternative for handling the present problem.

Table 4.

Optimal conditions for protein extraction obtained by partial derivatives of regression equations

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | Critical value | Predicted value | Stationary point | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncoded | Coded | ||||

| Y1 (Relative protein yield; %) | XA | 3.729 | 0.729 | 39.59865 | Saddle point |

| XB | 20.131 | 0.0262 | |||

| XC | 0.141 | 0.82 | |||

| XD | 0.145 | −0.55 | |||

| Y2 (Whiteness Index; WStensby) | XA | 3.704 | 0.704 | 63.82141 | Saddle point |

| XB | 29.825 | 1.965 | |||

| XC | 0.0731 | 0.538 | |||

| XD | 0.421 | 2.21 | |||

| Y3 (Phytate content; mg/100 g protein) | XA | 2.373 | −0.627 | 0.596007 | Saddle point |

| XB | 26.799 | 1.3598 | |||

| XC | 0.159 | 1.18 | |||

| XD | 0.015 | −1.85 | |||

| Y4 (Emulsion capacity; %) | XA | 3.225 | 0.225 | 47.36744 | Saddle point |

| XB | 25.003 | 1.0006 | |||

| XC | 0.102 | 0.04 | |||

| XD | 0.245 | 0.45 | |||

| Y5 (Emulsion stability; %) | XA | 3.177 | 0.177 | 49.08115 | Saddle point |

| XB | 22.957 | 0.5914 | |||

| XC | 0.095 | −0.1 | |||

| XD | 0.213 | 0.13 | |||

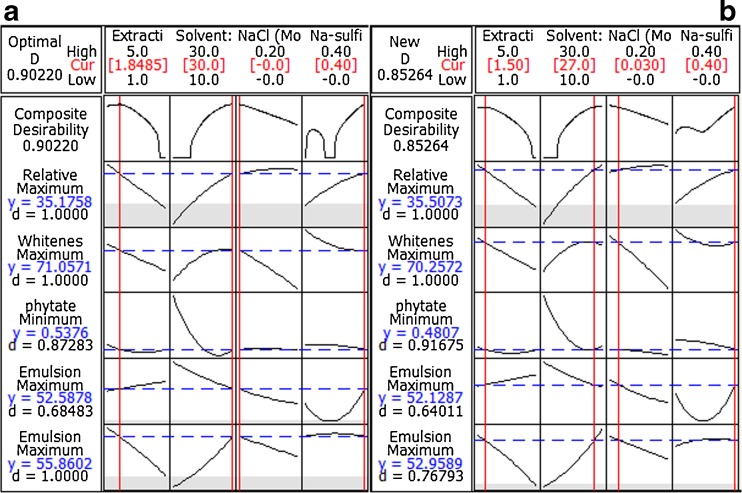

When various responses have to be considered at the same time, it is necessary to find optimal compromises between the total numbers of responses taken into account. Depending on whether a particular response is to be maximized, minimized or assigned a target value, different desirability functions can be used. So, in order to optimize five responses simultaneously, Derringer function or desirability function (d) was used because it is the most currently used multi-criteria methodology in optimization procedures. The optimization and individual desirability of each response variable was obtained by specifying the goals and boundaries (Table 5). The composite desirability was then combined with the individual desirability of all responses into a single measure by geometric mean (Tan et al. 2010). The predicted responses and individual desirability are presented in Table 5. The behaviour of the predicted responses was generated from the optimized factors of 1.9 h of extraction time, 30.0 v/w of solvent:meal ratio, 0.0 M of NaCl concentration and sodium sulfite level of 0.4 % (Fig. 5a). In order to make these parameters feasible in experimental runs in conjugation with our earlier report (unpublished data), these observed optimum parameters were drawn to the optimum factor level settings obtained in our previous report (i.e., 1.5 h of extraction time, 27 v/w of solvent:meal ratio, 0.03 M of NaCl concentration and sodium sulfite level of 0.4 %). The behaviour of the predicted responses from a feasible experimental run at new factor level settings was also generated (Fig. 5b) and compared with Fig. 5a. We used this technique of optimization from a recently published work by Tan et al. (2010). From these new factor levels, the individual desirability value of Relative protein yield and phytate content increases, because their corresponding predicted values become more suitable for the overall process, i.e., the new predicted response value for Relative protein yield increased and that for phytate content decreased. The new predicted values of the remaining responses and their individual desirabilities slightly decreased, compared to those of the original suggested optimal factors. The composite desirability (D) slightly reduced to 0.853 from 0.902 (Fig. 5). This is due to the described converse effects of several responses, i.e. unfeasible conformance to all requirements (Pickardt et al. 2009).

Table 5.

Multi-Response optimization and individual desirability obtained by Derringer function

| Response | Goal | Lower | Target | Upper | Predicted responses | Desirability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1 (Relative protein yield; %) | Maximum | 19.426 | 34.004 | 34.004 | 35.1758 | 1.000000 |

| Y2 (Whiteness Index; WStensby) | Maximum | 38.390 | 68.154 | 68.154 | 71.0571 | 1.000000 |

| Y3 (Phytate content; mg/100 g protein) | Minimum | 0.373 | 0.373 | 1.667 | 0.5376 | 0.872828 |

| Y4 (Emulsion capacity; %) | Maximum | 45.556 | 55.824 | 55.824 | 52.5878 | 0.684826 |

| Y5 (Emulsion stability; %) | Maximum | 43.478 | 55.824 | 55.824 | 55.8602 | 1.000000 |

Fig. 5.

Overall optimum conditions and response behaviour predicted from a the observed optimum condition and b feasible experimental condition

Verification of predicted values

To verify these predicted results, extraction experiments were conducted at the new process condition, which is envisaged from a feasible experimental run. The observed experimental values (mean of 4 measurements) were compared to the predicted values (Table 6). The predicted values could realistically be achieved within a 95 % confidence interval of experimental values or at least within 99.95 % confidence interval, an observation similar to that of Pickardt et al. (2009). The obtained experimental values for all responses, in the new feasible condition, were quite close to the predicted optimum values and are in reasonable agreement within the said confidence intervals for these optimized conditions. The closeness between the experimental and predicted values of the quality parameters also indicated the suitability of the corresponding polynomial models. Thus, we were successful in developing an extraction procedure that can produce rapeseed protein, with high yield, acceptable whiteness, improved emulsion properties and reduced level of harmful phytates, better than those reported by earlier authors.

Table 6.

Confirmatory trials of the optimal conditions by comparison of experimental and predicted values at observed optimum and feasible condition

| Response | Predicted value from optimum condition | New Predicted value from feasible condition | Observed experimental value* | Confidence Interval (95 %) | Confidence Interval (99.95 %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1 (Relative protein yield; %) | 35.1758 | 35.5073 | 46.2087 ± 1.9621 | (43.087, 49.331) | (30.192, 62.225) |

| Y2 (Whiteness Index; WStensby) | 71.0571 | 70.2572 | 72.3125 ± 3.7192 | (66.37, 78.25) | (41.85, 102.78) |

| Y3 (Phytate content; mg/100 g protein) | 0.5376 | 0.4807 | 0.27334 ± 0.0339 | (0.2194, 0.3272) | (0.0032, 0.5499) |

| Y4 (Emulsion capacity; %) | 52.5878 | 52.1287 | 49.1505 ± 0.9561 | (47.629, 50.672) | (41.346, 56.955) |

| Y5 (Emulsion stability; %) | 55.8602 | 52.9589 | 50.9478 ± 3.8913 | (44.76, 57.14) | (19.18, 82.71) |

*Each experimental value represents the means ± standard deviation from four replicates (n = 4)

Conclusion

In this work, multi-response surface methodology along with composite desirability function was successfully employed to model and optimize the conditions to obtain rapeseed press-cake protein with improved yield, whiteness, technical properties (emulsification) and reduced level of residual phytates. The optimal factor combination (1.5 h of extraction time, 27 v/w of solvent:meal ratio, 0.03 M of NaCl concentration and sodium sulfite level of 0.4 %) reflects a compromise between the partially conflicting natures of a set of responses. Predicted values under the identified feasible condition were experimentally verified to be in general agreement with the predicted values under optimal condition (95 % or 99.95 % confidence interval). The outcomes of this study can prove productive for food, drug or cosmetic industries.

Electronic supplementary material

The fitted line plot indicating the closeness between observed response values and predicted response values for (a) Relative protein yield, (b) WStensby, (c) phytate content, (d) Emulsion capacity, and (e) Emulsion stability. (DOC 97.5 kb)

Normal Probability plots (by Anderson-Darling Normality test within 95 % prediction band) using standardized residuals of the dependent variable (a) Relative protein yield, (b) WStensby, (c) phytate content, (d) Emulsion capacity, and (e) Emulsion stability. (DOC 108 kb)

(JPEG 120 kb)

Acknowledgments

MDP would like to thank DST-INSPIRE Programme, DST (India).

References

- Adel A, Shehata Y, Thannoun MM. Extractability of Nitrogenous constituents from Iraqi Mung Bean as affected by pH, salt type, and other factors. J Agric Food Chem. 1981;29:53–57. doi: 10.1021/jf00103a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akande KE, Doma UD, Agu HO, Adamu HM. Major antinutrients found in plant protein sources: their effect on nutrition. Pak J Nutr. 2010;9(8):827–832. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2010.827.832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali F, Mondor M, Ippersiel D, Lamarche F. Production of low-phytate soy protein isolate by membrane technologies: impact of salt addition to the extract on the purification process. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2011;12:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2011.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alsohaimy SA, Sitohy MZ, El-Marsy RA. Isolation and partial characterization of chickpea, lupine and lentil seed proteins. World J Agric Sci. 2007;3(1):123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Balange AK, Benjakul S. Effect of oxidised phenolic compounds on the gel property of mackerel (Rastrelliger kanagurta) surimi. Lebensm Wiss Technol. 2009;42:1059–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2009.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bérot S, Compoint JP, Larré C, Malabat C, Guéguen J. Large scale purification of rapeseed proteins (Brassica napus L.) J Chromatogr B. 2005;818(1):35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari MR, Kawabata J. Cooking effects on oxalate, phytate, trypsin and a-amylase inhibitors of wild yam tubers of Nepal. J Food Compos Anal. 2006;19:524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2004.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bup DN, Abi CF, Tenin D, Kapseu C, Tchiegang C. Optimisation of the cooking process of Sheanut kernels (Vitellaria paradoxa Gaertn.) using the Doehlert experimental design. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Rohani S. Recovery of canola meal proteins by precipitation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1992;40(1):63–68. doi: 10.1002/bit.260400110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SM, Gu YS, Kim SB. Extracting optimization and physical properties of yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) skin gelatin compared to mammalian gelatins. Food Hydrocoll. 2005;19:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2004.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damodaran S. Protein stabilization of emulsions and foams. J Food Sci. 2005;70(3):R54–R66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb07150.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X-Y, Guo L-L, Wei F, Li J-F, Jiang M-L, Li G-M, Zhao Y-D, Chen H. Some characteristics and functional properties of rapeseed protein prepared by ultrasonication, ultrafiltration and isoelectric precipitation. J Sci Food Agric. 2011;91:1488–1498. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Pérez S, Merck KB, Vereijken JM, van Koningsveld GA, Gruppen H, Voragen AGJ. Isolation and characterization of undenatured chlorogenic acid free sunflower (helianthus annuus) proteins. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:1713–1719. doi: 10.1021/jf011245d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BE (2006) Colour reduction in canola protein isolate. United States Patent No US20060281904A1. Available at: http://www.google.com.br/patents/US20060281904

- Green BE, Xu L, Milanova R, Segall KI (2010) Colour reduction in canola protein isolate. United States Patent No US7678392B2. Available at: http://www.google.co.in/patents/US7678392

- Harland BF, Morris ER. Phytate: a good or a bad food component? Nutr Res. 1995;15(5):733–754. doi: 10.1016/0271-5317(95)00040-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harnsilawat T, Pongsawatmanit R, McClements DJ. Stabilization of model beverage cloud emulsions using protein-polysaccharide electrostatic complexes formed at the oil–water interface. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:5540–5547. doi: 10.1021/jf052860a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan HMM, Afify AS, Basyiony AE, Ahmed Ghada T. Nutritional and functional properties of defatted wheat protein isolates. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2010;4(2):348–358. [Google Scholar]

- Karacabey E, Mazza G. Optimisation of antioxidant activity of grape cane extracts using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2010;119:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.06.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IH, Hancock JD, Hines RH. Influence of processing methods on ileal digestibility of nutrients from soybeans in growing and finishing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2000;13(2):192–199. [Google Scholar]

- Koocheki A, Taherian AR, Razavi SMA, Bostan A. Response surface methodology for optimization of extraction yield, viscosity, hue and emulsion stability of mucilage extracted from Lepidium perfoliatum seeds. Food Hydrocoll. 2009;23:2369–2379. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2009.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krause J-P, Schwenke KD. Behaviour of a protein isolate from rapeseed (Brassica napus) and its main protein components—globulin and albumin—at air/solution and solid interfaces, and in emulsions. Colloids Surf B. 2001;21:29–36. doi: 10.1016/S0927-7765(01)00181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Qi G, Sun XS, Stamm MJ, Wang D. Physicochemical properties and adhesion performance of canola protein modified with sodium bisulfite. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2012;89:897–908. doi: 10.1007/s11746-011-1977-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liadakis GN, Tzia C, Oreopoulou V, Thomopoulos CD. Isolation of tomato seed meal proteins with salt solutions. J Food Sci. 1998;63(3):450–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1998.tb15762.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhao G, Ren J, Zhao M, Yang B. Effect of denaturation during extraction on the conformational and functional properties of peanut protein isolate. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2011;12:375–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2011.01.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long J-J, Fu Y-J, Zu Y-G, Li J, Wang W, Gu C-B, Luo M. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of flaxseed oil using immobilized enzymes. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102:9991–9996. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.07.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lqari H, Vioque J, Pedroche J, Millán F. Lupinus angustifolius protein isolates: chemical composition, functional properties and protein characterization. Food Chem. 2002;76:349–356. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00285-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maga JA. Phytate: its chemistry, occurrence, food interactions, nutritional significance, and methods of analysis. J Agric Food Chem. 1982;30(1):1–9. doi: 10.1021/jf00109a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manamperi WAR, Wiesenborn DP, Chang SKC, Pryor SW. Effects of protein separation conditions on the functional and thermal properties of canola protein isolates. J Food Sci. 2011;76(3):E266–E273. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marnoch R, Diosady LL. Production of mustard protein isolates from oriental mustard seed (Brassica juncea L.) J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2006;83(1):65–69. doi: 10.1007/s11746-006-1177-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCurdy SM. Effects of processing on the functional properties of canola/rapeseed protein. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1990;67(5):281–284. doi: 10.1007/BF02539677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mune MAM, Mbome IL, Minka SR. Optimization of protein concentrate preparation from Bambara bean using response surface methodology. J Food Process Eng. 2010;33:398–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4530.2008.00281.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okubo K, Waldrop AB, Iacobucci GA, Myers DV. Preparation of low-phytate soybean protein isolate and concentrate by ultrafiltration. Am Assoc Cereal Chem. 1975;52:263–271. [Google Scholar]

- Park S-H, Bean SR. Investigation and optimization of the factors influencing sorghum protein extraction. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:7050–7054. doi: 10.1021/jf034533d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peričin D, Radulović L, Trivić S, Dimić E. Evaluation of solubility of pumpkin seed globulins by response surface method. J Food Eng. 2008;84:591–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2007.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pickardt C, Neidhart S, Griesbach C, Dube M, Knauf U, Kammerer DR, Carle R. Optimisation of mild-acidic protein extraction from defatted sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) meal. Food Hydrocoll. 2009;23:1966–1973. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2009.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quanhong L, Caili F. Application of response surface methodology for extraction optimization of germinant pumpkin seeds protein. Food Chem. 2005;92:701–706. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.08.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino MI, Amfield SD, Nadon CA, Bernatsky A. Phenolic protein interactions in relation to the gelation properties of canola protein. Food Res Int. 1996;29(1):653–659. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(97)89643-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi MA, Appu Rao AG, Bhagya S. Evaluation of mustard (Brassica juncea) protein isolate prepared by steam injection heating for reduction of antinutritional factors. Lebensm Wiss Technol. 2006;39:911–917. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2005.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serraino MR, Thompson LU. Removal of phytic acid and protein-phytic acid interactions in rapeseed. J Agric Food Chem. 1984;32:38–40. doi: 10.1021/jf00121a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabarestani HS, Maghsoudlou Y, Motamedzadegan A, Sadeghi Mahoonak AR. Optimization of physico-chemical properties of gelatin extracted from fish skin of rainbow trout (Onchorhynchus mykiss) Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:6207–6214. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan MC, Chin NL, Yusof YA. A Box–Behnken design for determining the optimum experimental condition of cake batter mixing. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Wanasundara PKJPD, Shahidi F. Optimization of Hexametaphosphate-assisted extraction of flaxseed proteins using response surface methodology. J Food Sci. 1996;61(3):604–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1996.tb13168.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L (1999) The removal of phenolic compounds for the production of high-quality canola protein isolates. PhD Thesis. Department of Chemical Engineering and Applied Chemistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. Available at: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/12593/1/NQ45652.pdf

- Xu L, Diosady LL. Removal of phenolic compounds in the production of high-quality canola protein isolates. Food Res Int. 2002;35:23–30. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00159-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Lui F, Luo H, Diosady LL. Production of protein isolates from yellow mustard meals by membrane processes. Food Res Int. 2003;36:849–856. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(03)00082-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin B, Deng W, Xu K, Huang L, Yao P. Stable nano-sized emulsions produced from soy protein and soy polysaccharide complexes. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;380:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarubica AR, Miljković MN, Purenović MM, Tomić VB. Colour parameters, whiteness indices and physical features of marking paints for horizontal signalization. Facta Univ Ser Phys Chem Technol. 2005;3(2):205–216. doi: 10.2298/FUPCT0502205Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The fitted line plot indicating the closeness between observed response values and predicted response values for (a) Relative protein yield, (b) WStensby, (c) phytate content, (d) Emulsion capacity, and (e) Emulsion stability. (DOC 97.5 kb)

Normal Probability plots (by Anderson-Darling Normality test within 95 % prediction band) using standardized residuals of the dependent variable (a) Relative protein yield, (b) WStensby, (c) phytate content, (d) Emulsion capacity, and (e) Emulsion stability. (DOC 108 kb)

(JPEG 120 kb)