Abstract

Omega-3 fatty acid imparted good evidence of health benefits. Flaxseed oil, being the richest vegetarian source of alpha linolenic acid (omega-3 fatty acid), was incorporated in cookies by replacing shortening at level of 5 %, 10 %, 20 %, 30 %, 40 % and 50 %. Effect of shortening replacement with flaxseed oil on physical, textural and sensory attributes were investigated. Spread ratio and breaking strength of cookies increased as flaxseed oil level increased. Sensory score was not significantly affected up to 30 % shortening replacement with flaxseed oil as compared with the control cookies. Above 30 % flaxseed oil, sensory score was adversely affected. Fatty acid profile confirmed the enhancement of omega-3 fatty acid from 0 (control) to 14.14 % (30 % flaxseed oil cookies). The poly-unsaturated to saturated fatty acid ratio (P/S) increased from 0.088 (control) to 0.57 while ω – 6 to ω -3 fatty acid ratio of flaxseed oil cookies decreased from 4.51 (control) to 0.65 in the optimized cookies. The data on storage characteristics of the control and 30 % flaxseed oil cookies showed that there was significant change in the moisture content, Peroxide value (PV) and overall acceptability (OAA) up to 28 days of storage at 45 °C packed in polyethylene bags. Flaxseed oil cookies were acceptable up to 21 days of storage and afterwards noticeable off flavour was perceived.

Keywords: Breaking strength, Flaxseed oil, Linolenic acid, Linoleic acid, PV, Spread ratio, P/S ratio, ω-6/ω-3 fatty acid ratio

Introduction

Cookies are one of the important segments of biscuit market share and relished by all age groups owing to its taste and crisp texture. Shortening is one of the major ingredients in cookies formulation which imparts lubricity, acceptable texture and flavour (Maache-Rezzoug et al. 1998). Generally, bakery shortening contains saturated fatty acids like palmitic, oleic and stearic acid. Consumption of saturated fatty acids in higher amount leads to health disorders like obesity, cardiovascular and other metabolic diseases. On the other side, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) have been associated with various health benefits relating to treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (Rennie et al. 2003), improving blood pressure control and preserve renal function even in hypertensive heart transplant recipients (Holm et al. 2001) and coronary artery disease (Freeman 2000). Therefore, replacement of saturated fatty acid with PUFA for the protection against metabolic disorders and diseases can be a more practical solution for healthy and nutritious food product development. In last two decade, flaxseed has emerged as one of the functional ingredient in food product development owing to its high alpha-linolenic acid (ALA ω-3 PUFA), dietary fiber, lignan and protein content (Rajiv et al. 2012; Chetana 2010; Madhusudhan et al. 2000; Chen et al. 1994). Flaxseed is the richest vegetarian source of ALA (Ganorkar and Jain 2013), comprising of 57 % of total fat content (Morris 2007). Use of whole flaxseed or defatted flaxseed in cookies formulation were explored by researchers (Gambus et al. 2004; Masoodi and Bashir-Khalid 2012; Rajiv et al. 2012). But on replacement of bakery shortening with flaxseed oil seemed to be limited. Therefore, in the present investigation attempts were made to develop cookies with replacement of shortening with flaxseed oil and its effect on physical, sensory, fatty acid profile and storage attributes were studied.

Materials and methods

Raw materials

Refined wheat flour (Brand Uttam), hydrogenated vegetable oil (Brand Raag), sugar, custard powder (Brand Weikfield), vanilla flavor (Brand Blue Bird) and leavening agent (Brand Blue Bird) were procured from the local market. Flaxseed oil was purchased from Hakim Chichi Pharma, Surat, Gujarat. Analyticalcal grade chemicals and reagents of Qualigens and S.D. fine chemicals were used in the analysis.

Proximate composition

Moisture, ash, fat, protein and crude fiber content were estimated according to standard methods (AOAC 2000). Carbohydrate content was estimated by difference method.

Oil analysis

Acid value, iodine value, oil density and PV were estimated as per ISI methods (IS: 1011–1981).

Fatty acid profile

Fatty acid profile analysis was carried out by Gas Chromatography (GC) instrument (Make – Perkin Elmer, Model – Auto System XL) according to the method suggested by Petrovic et al. (2010). In case of cookies, fat was extracted by using soxhlet apparatus with petroleum ether as extracting solvent. Homogenized oil sample was weighed and dried for 1 h at 105 °C. The sample was cooled in desiccators. Lipids were extracted with petroleum ether by soxhlet apparatus for 4 h on heating mentle. After extraction, petroleum ether was evaporated and the flask was dried at 105 °C, cooled in desiccators and then weighed. Lipids were converted to fatty acid methyl esters by trans-esterification. Sample (60 mg) was dissolved in 4 ml of isooctane in test tube and 200 μl of methanolic potassium hydroxide solution (2 mol/l) was added. Solution was shaken vigorously for about 30 s. The solution was neutralized by addition of 1 g of sodium hydrogen sulphate monohydrate. After the salt has settled, 1 ml of upper phase was transferred into 5 ml vial and analyzed. Analyses were performed on GC instrument equipped with flame ionization detector and spilt/splitless injector. Injection temperature was 180 °C and samples were injected manually (1 μl). Column was packed with 12.5 % diethylene glycol solution. Column temperature 220 °C, detector temperature 230 °C and carrier gas nitrogen at 15 ml/min were maintained. 30 min run time in every analysis was maintained. The peaks were identified by comparing retention time with those of authentic standards and represented as relative percentage.

Cookie preparation

Cookie was prepared as per the formulations given by Matz (1992) with some modifications. Dry ingredients i.e. refined wheat flour (250 g), salt (2.5 g) and baking powder (1.5 g) were thoroughly mixed and sieved twice for uniform blend. Shortening (100 g) and ground sugar (100 g) were creamed together manually for 10 min. to get bright and fluffy mass. Milk (60 ml) and vanilla essence (1 ml) was added in the mass and mixed for another 5 min. Finally, dry ingredient blend flour was slowly added to the above creamed mass and mixed for 2 min. Flaxseed oil was incorporated by replacing shortening at 5 %, 10 %, 15 %, 20 %, 25 %, 30 %, 35 %, 40 %, 45 % and 50 % level. The cookie dough was sheeted to 8 mm thickness and cut into circular shape using 42 mm diameter cutter. The cookies were then baked at 180 °C for 15 min. The cookies were cooled for 10 min, then wrapped in aluminum foil and packed in polyethylene bag.

Physical analysis of cookies

Three cookies of each treatment were weighed on balance and mean value was reported as weight of cookie (g). Diameter (D), thickness (T) and spread ratio were analyzed as physical characteristics for control and cookies with flaxseed oil according to the method suggested by Gomez et al. (1997). For the determination of cookies diameter (D), six cookies were placed edge to edge. The total diameter of the six randomly selected cookies was measured in mm by using a ruler. The cookies were rotated at an angle of 90° for duplicate reading. The average diameter was reported in mm. To determine the thickness (T), six cookies were placed on top of another. The total height was measured in mm with the help of ruler. This was repeated thrice to get an average value and results are reported in mm. Spread ratio was determined with the help of following formula:

| 1 |

Textural analysis of cookies

Break strength of prepared cookies were assessed by Lloyd texture analyzer (Model TA plus) using three point bend rig setup according to the method of Gaines (1991). The sample was rested on two supporting beams spread at a distance of 3 cm. Another beam connected to moving part was brought down to break the cookies at a crosshead speed of 10 mm/min and load cell of 100 N.

Sensory evaluation of cookies

Sensory evaluation was carried out by a panel of ten judges. Hedonic rating test was employed using 9-point hedonic scale (from dislike extremely −1 to like extremely −9). Sensory parameters such as color, taste, texture and overall acceptability were evaluated (Ranganna 2000). Mean values of three replicates were reported.

Storage stability of optimized cookies

The optimized cookies (with flaxseed oil) and control cookies (without flaxseed oil) were packed in polyethylene bags (Thickness 60 μm). Packed cookies were placed in incubator at 45 °C for 1 month. At an interval of 7 days, each sample was analyzed for moisture content, PV and overall OAA score.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed with Daniel’s XL Toolbox Version 5.08 using one – way analysis of variances (ANOVA) with tukey comparison of means values. Differences between mean values with probability p ≤ 0.05 were recognized as statistically significant differences.

Results and discussion

Physico-chemical analysis of flaxseed oil

Oil density of 0.927 ± 0.002 g/ml, iodine value of 176 ± 2.6, acid value of 2.1 ± 0.6 were estimated. These results are well in agreement with the results reported by Nagaraj (1995) for flaxseed oil. Flaxseed oil peroxide value of 0.4 meq/kg of fat was found. Freshly deodorized oil should have zero peroxide value, but in most cases, for the product to have acceptable storage stability the peroxide value of oils used should be less than 5 (Rudan-Tasic and Klofutar 1999) and can be tolerable up to 10. This indicated that flaxseed oil was having satisfactory quality attributes and could be used in the further study.

Fatty acid profile of flaxseed oil

Fatty acid profile of flaxseed oil was represented in Table 4. Linolenic acid (ω-3 fatty acid) was found in the range of 52.09 %, the major fatty acid in the flaxseed oil followed by oleic acid (21.93 %) and ω-6 linoleic acid (14.14 %). Similar results are reported by Hettiarachchy et al. (1990), Morris (2007) and Canadian Grain Commission (2009). Some variations in the content can be attributed to variety, growing environment, seed processing and method of analysis (Daun et al. 2003). It is quite evident that the level of linolenic acid is by far the largest component of the fatty acid profile of flaxseed oil and undesirable saturated fatty acids are very low. Flaxseed oil may be considered a functional food ingredient because its high content of linolenic acid may contribute in promoting good health as well as preventing diseases.

Table 4.

Fatty acid profile of cookies*

| Fatty acids | Flaxseed oil | Control cookie | Optimized cookie (30 % Flaxseed oil) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myristic acid | - | 1.28 | 0.79 |

| Palmitic acid | 6.02 | 43.02 | 32.96 |

| Palmitoleic acid | - | 0.43 | - |

| Stearic acid | 5.58 | 7.09 | 6.57 |

| Oleic acid | 21.93 | 38.45 | 34.67 |

| Linoleic acid (ω-6) | 14.14 | 4.51 | 9.13 |

| Linolenic acid (ω-3) | 52.09 | - | 14.12 |

| Unknown fatty acid | 0.24 | 5.22 | 1.76 |

| Σ PUFA | 66.23 | 4.51 | 23.25 |

| Σ SFA | 11.60 | 51.39 | 40.32 |

| P/S ratio | 5.71 | 0.08 | 0.57 |

| ω-6/ω-3 ratio | 0.27 | 4.51 | 0.65 |

*Relative percentage of fatty acid on the basis of fat were reported

PUFA – Polyunsaturated fatty acids, SFA – Saturated fatty acid, P/S ratio – PUFA/SFA

Effect of shortening replacement with flaxseed oil on physical characteristics of cookies

The physical characteristics of cookies made using flaxseed oil at different proportions are shown in Table 1. Significant increase in the weight of cookies was observed at 30 % shortening replacement with flaxseed oil and above. This can be attributed to the dough density, which depends upon the type of fat used. The hydrogenated fat has the ability to form beta crystals which does not support aeration (Knightly 1981). Less aerated dough is denser than aerated dough resulting in higher weight. The solid content of the fat while mixing affects dough density, dough with lower solid fat has higher density (Baltsavias et al. 1997). As the flaxseed oil content increased, significant increase in cookies diameter and thickness were observed. The lowest diameter of 48.13 ± 0.14 and thickness of 12.0 ± 0.18 were observed in control while the highest diameter of 54.23 ± 0.18 and thickness of 12.60 ± 0.11 were found in 50 % flaxseed oil cookies. Consequently, lowest spread ratio of 4.00 ± 0.05 in control cookies while the highest spread ratio of 4.30 ± 0.05 were observed at 50 % shortening replacement with flaxseed oil. Abboud et al. (1985) reported that fat type did not affect cookie spread. But in the present investigation, cookies containing hydrogenated fat had significantly less spread as compared with flaxseed oil cookies. Partial hydrogenation helps to produce vegetable shortening having desirable plastic character (Given 1994). The plastic nature of the shortening is influenced by factors such as amount of solid material present, size and form of the individual crystals. Viscosity of the cookie dough in the oven is known to affect the spread of cookies (Tsen et al. 1975). The cookie dough containing flaxseed oil continued to spread because the dough was not sufficiently viscous to stop the spread. Similar results are reported for sunflower oil cookies by Jacob and Leelavathi (2007).

Table 1.

Effect of shortening replacement with flaxseed oil on the physical characteristics of cookies

| Parameters | Control | Sample T1 (5 %) | Sample T2 (10 %) | Sample T3 (20 %) | Sample T4 (30 %) | Sample T5 (40 %) | Sample T6 (50 %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (g) | 15.50 ± 0.53c | 15.66 ± 0.50c | 16.02 ± 0.40cb | 16.73 ± 0.60ac | 17.39 ± 0.45ab | 17.76 ± 0.60a | 17.96 ± 0.57a |

| Diameter (mm) | 48.13 ± 0.14f | 48.69 ± 0.23e | 49.54 ± 0.15d | 51.23 ± 0.15c | 51.64 ± 0.19c | 52.81 ± 0.16b | 54.23 ± 0.18a |

| Thickness (mm) | 12.0 ± 0.18c | 12.15 ± 0.13bc | 12.28 ± 0.15abc | 12.39 ± 0.11abc | 12.50 ± 0.17ab | 12.53 ± 0.12ab | 12.60 ± 0.11a |

| Spread ratio | 4.00 ± 0.05c | 4.00 ± 0.02c | 4.03 ± 0.06c | 4.13 ± 0.04bc | 4.13 ± 0.07bc | 4.21 ± 0.04ab | 4.30 ± 0.05a |

Reported values are the mean of three determinations with standard deviation (±SD)

Values followed by the same superscript alphabet in the same row are not significantly different (p ≤ 0.05)

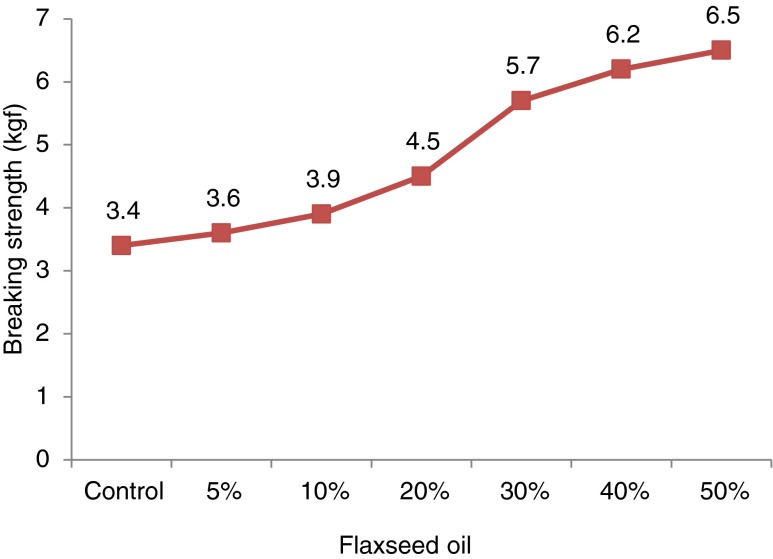

Effect of shortening replacement with flaxseed oil on breaking strength of cookies

Breaking strength of cookies (Fig. 1) showed that cookies containing more flaxseed oil were the hardest. Cookies containing shortening had the lowest breaking strength of 3.4 kgf while cookies containing 50 % flaxseed oil replaced with shortening had the highest breaking strength of 6.5 kgf. Subjective evaluation at the time of cookies dough preparation showed that the hardness of cookies dough containing shortening only was hardest than other cookies dough which contained flaxseed oil replaced with shortening. But, this trend was changed after baking. More Plastic and smooth textured fat greater its shortening power (Greethead 1969). Plasticity in fats is required since during the creaming process they entrap and retain considerable volumes of air resulting in an important leavening effect. On the other hand, liquid oils are dispersed upon mixing throughout the dough in the form of globules that are less effective in their shortening and aerating actions (Hartnett and Thalheimer 1979). Even if large amounts of air can be incorporated into liquid oil, it cannot be retained in the system (Kamel 1994) and this gives insight behind the hard texture of the cookies at higher flaxseed oil incorporation. Jacob and Leelavathi (2007) also reported that sunflower oil cookies texture was harder than hydrogenated fat cookies. The equation obtained, showing the effect of shortening replacement with flaxseed oil (x) on breaking strength (y) of cookies is as follows.

| 2 |

Fig. 1.

Effect of shortening replacement with flaxseed oil on breaking strength of cookies

Effect of shortening replacement with flaxseed oil on sensory evaluation of cookies

Sensory evaluation of control and flaxseed oil cookies were carried out by ten panelists on 9 point hedonic scale presented in Table 2. No significant change in appearance attribute was observed. However, subjective evaluation of appearance attributes revealed that surface cracking increased as flaxseed oil content increased. This may be attributed to higher spread of flaxseed oil cookies. No significant change in texture, taste and overall acceptability was observed up to 30 % flaxseed oil replacement with shortening as compared with the control cookies. Decrease in the texture score might be attributed to the increase in the breaking strength of the cookies containing higher flaxseed oil. Panel members perceived flaxseed oil cookies (at 40 % and 50 %) harder than control cookies. Flaxseed oil taste was dominantly noticeable at 40 % and 50 % flaxseed oil cookies. Therefore, it consequently affected on taste sensory score. OAA score indicated that up to 30 % shortening replacement with flaxseed oil was well comparable with control cookies. On this basis, 30 % flaxseed oil (on shortening basis) cookies was optimized.

Table 2.

Effect of shortening replacement with flaxseed oil on sensory attributes of cookies

| Cookies | Appearance | Texture | Taste | Overall acceptability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 7.9 | 7.4 ± 0.52a | 8.2 ± 0.63a | 8.0 ± 0.67a |

| 5 % | 7.9 | 7.3 ± 0.67a | 8.1 ± 0.57a | 7.8 ± 0.42a |

| 10 % | 8.0 | 7.1 ± 0.87ab | 7.8 ± 0.42a | 7.6 ± 0.52a |

| 20 % | 7.8 | 7.0 ± 0.82ab | 7.7 ± 0.48a | 7.5 ± 0.53a |

| 30 % | 7.9 | 6.9 ± 0.87ab | 7.6 ± 0.52a | 7.4 ± 0.52a |

| 40 % | 7.6 | 6.1 ± 0.73bc | 6.3 ± 0.82b | 6.6 ± 0.52b |

| 50 % | 7.6 | 5.5 ± 0.71c | 5.6 ± 1.26b | 5.7 ± 0.67c |

Reported values are the mean of scores ± SD given by ten semi trained panel members

Values followed by the same superscript alphabet in the column are not significantly different (p ≤ 0.05)

Proximate composition and fatty acid profile of cookies

Proximate composition of control and optimized flaxseed oil cookies are presented in Table 3. No significant change in the composition of flaxseed oil cookies was observed as compared with the control cookies. Insignificant increase in the fat content of flaxseed oil cookies was observed. Significant increase in the PV of lipids extracted from flaxseed oil cookies was observed as compared with control cookies lipids. It can be reasoned here that flaxseed oil contained more linolenic and linoleic acid (polyunsaturated fatty acids) which are more prone to oxidation that led to increase in the PV of flaxseed oil cookies. Fatty acid profile of cookies (Table 4) showed that myristic acid, palmitic acid, and stearic acid (saturated fatty acids) decreased or disappeared while unsaturated fatty acids (linoleic and linolenic acid) increased in the flaxseed oil cookies except oleic acid. This can be attributed to the dilution of cookies shortening with the flaxseed oil. Rajiv et al. (2012) also reported similar results for cookies after incorporation of roasted flaxseed flour. Linolenic acid (omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid) content was found to be 14.12 % in the optimized flaxseed oil cookies while it was not detected in control cookies. This confirmed the enrichment and stability of omega-3 fatty acid in flaxseed oil cookies. Chen et al. (1994) reported that ground flaxseed does not lose significant amount of linolenic acid during baking in muffin mixes and the ground flaxseed readily absorbs oxygen under typical baking conditions but this did not markedly affect its fatty acid composition.

Table 3.

Proximate composition of cookies

| Parameters | Control cookies | Flaxseed oil cookies |

|---|---|---|

| Ash content (%) | 0.8 ± 0.2a | 1.00 ± 0.2a |

| Moisture content (%) | 4.0 ± 0.4a | 3.7 ± 0.3a |

| Protein content (%) | 1.02 ± 0.3a | 0.9 ± 0.2a |

| Fat content (%) | 21.5 ± 1.5a | 23.1 ± 1.3a |

| Crude fibre content (%) | 0.13 ± 0.08a | 0.15 ± 0.6a |

| Carbohydrate content (%)* | 72.55 | 71.15 |

| Peroxide value (meq/kg of fat) | 3.13 ± 0.32a | 3.85 ± 0.20b |

Reported values are the mean values ± SD of three determinations

*Carbohydrate content was estimated by the difference method

Peroxide value and FFA content were estimated for extracted lipid from the respective cookies

Values followed by the same superscript alphabet in the same row are not significantly different (p ≤ 0.05)

The two main parameters currently used to assess nutritional quality of the lipid fraction of foods are the ratios between polyunsaturated and saturated (P/S) and between ω-6 and ω-3 fatty acids. Accordingly, to improve the health status of the population, the nutritional authorities have recommended regulating the consumption of foods rich in ω-3 PUFAs, in such a way that a ω - 6/ω -3 PUFA ratio of less than 4 can be achieved and that the P/S ratio is higher than 0.4 (Wood et al. 2004). ω – 6 to ω -3 fatty acid ratio of flaxseed oil cookies decreased from 4.51 (control) to 0.65 while P/S ratio of flaxseed oil cookies increased from 0.088 (control) to 0.57. Similar results are reported by Pelser et al. (2007) for dutch style fermented sausages after incorporation of flaxseed oil and canola oil.

Storage characteristics of cookies

The control and cookies with 30 % shortening replaced with flaxseed oil were evaluated at 0, 7, 14, 21 and 28 days of storage at 45 °C by determining the moisture content, PV and OAA score. The results (Table 5) showed that there was significant increase in the moisture content of cookies at and after 14 days of storage. The moisture content percent increased from 3.7 ± 0.3 to 7.8 ± 0.3 in the flaxseed oil cookies and from 4.0 ± 0.4 to 7.2 ± 0.4 in the control cookies. PV value of extracted lipids demonstrated that flaxseed oil cookies showed higher increase in PV as compared with the control cookies. This might be attributed to the higher amount of unsaturated fatty acids (linolenic and linoleic acid) present in flaxseed oil cookies. Unsaturated fatty acids are more susceptible for oxidation and PV value is measure of oxidation in oil. OAA score decreased from 7.4 to 5.9 on 28th day of storage in the flaxseed oil cookies. This can be attributed due to formation of hydro-peroxides and short chain fatty acids which have imparted off flavour to cookies. However, panel members did not perceive noticeable off flavour up to 21 days of storage. Cookies stored up to 21 days were acceptable as no significant change in OAA score was observed. Pelser et al. (2007) also reported that lipid oxidation increased during storage in flaxseed oil incorporated dutch style fermented sausages.

Table 5.

Storage characteristics of cookies

| Storage Days | Moisture content (%) | PV (meq/kg of fat) | OAA Score* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Optimized | Control | Optimized | Control | Optimized | |

| 0 | 4.0 ± 0.4d | 3.7 ± 0.3d | 3.13 ± 0.32d | 3.85 ± 0.20e | 8.0 ± 0.67a | 7.4 ± 0.52a |

| 7 | 4.3 ± 0.2d | 3.9 ± 0.3d | 3.40 ± 0.44cd | 4.65 ± 0.48d | 8.0 ± 0.40a | 7.3 ± 0.48a |

| 14 | 5.4 ± 0.4c | 5.8 ± 0.4c | 5.23 ± 0.82c | 7.84 ± 0.90c | 7.5 ± 0.37a | 7.1 ± 0.32a |

| 21 | 6.3 ± 0.3b | 6.6 ± 0.3b | 7.13 ± 0.73b | 9.45 ± 0.52b | 7.4 ± 0.67ab | 7.0 ± 0.52a |

| 28 | 7.2 ± 0.4a | 7.8 ± 0.3a | 9.33 ± 0.62a | 13.85 ± 1.03a | 7.1 ± 0.54b | 5.9 ± 0.62b |

Reported values are the mean of three determinations ± SD

*Overall Acceptability score – the mean value of ten panel members score on hedonic scale

Values followed by same superscript alphabet in the column are not significantly different (p ≤ 0.05)

Conclusion

The replacement of shortening with flaxseed oil from 0 to 50 % level demonstrated an increase in weight, diameter, thickness, spread ratio and breaking strength of cookies. Beyond 30 % shortening replacement with flaxseed oil in cookies adversely affected the quality. Thus, acceptable quality of cookies with omega-3 fatty acid can be prepared by fortifying 30 % flaxseed oil. The use of emulsifier may enhance the appearance and textural attribute of the flaxseed cookies. The control cookies had negligible content of linolenic acid whereas cookies with 30 % flaxseed oil had 14.14 % linolenic acid. The incorporation of flaxseed oil progressively increased the P/S ratio and decreased the ω - 6/ω -3 ratio resulting to close desirable values. Omega-3 fatty acid enrichment by the use of flaxseed oil in food products can be explored as functional foods. Storage characteristics of flaxseed oil cookies revealed that shelf life of products containing flaxseed oil will be limiting factor. Use of appropriate antioxidants in food system and appropriate packaging may be explored to enhance shelf life of food products containing flaxseed oil. ω -3 fatty acid enriched food product is better strategy to meet the body’s metabolic needs as compared with the oral dietary supplements.

Acknowledgments

Authors gratefully acknowledge the financial and infrastructural facility extended by A.D. Patel Institute of Technology, New Vallabh Vidya Nagar, Anand, Gujarat, India. Authors are also thankful to Dr. V.S. Patel, Director, Sophisticated Instruments Centre for Applied Research and Testing (SICART), Vidya Nagar, Anand for providing gas chromatography analysis facility.

References

- Abboud AM, Rubenthaler GL, Hoseney RC. Effect of fat and sugar in sugar snap cookies and evaluation of tests measure cookie flour quality. Cereal Chem. 1985;62:124–129. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . The official methods of analysis. 17. Washington: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baltsavias A, Jurgens A, Van Vliet T. Rheological properties of short doughs at small deformation. J Cereal Sci. 1997;26:289–300. doi: 10.1006/jcrs.1997.0133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Grain Commission (2009) Quality of western Canadian flaxseed, export quality data, July 2009. http://www.grainscanada.gc.ca/flax-lin/harvest-recolte/2009/hqf09-qrl09-eng.htm Assessed on 10/08/2013

- Chen ZY, Ratnayake WMN, Cunnane SC. Oxidative stability of flaxseed lipids during baking. JAOCS. 1994;71:629–632. [Google Scholar]

- Chetana RSYR. Preparation and quality evaluation of peanut chikki incorporated with flaxseeds. J Food Sci Technol. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0177-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daun JK, Barthet VJ, Chornick TL, Duguid S. Structure, composition, and variety development of flaxseed. In: Thompson LU, Cunnane SC, editors. Flaxseed in human nutrition. 2. Champaign: AOCS Press; 2003. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman MP (2000) Omega-3 fatty acids in psychiatry - A review. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 12:159–165 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gaines CS. Instrumental measurement of the hardness of cookies and crackers. Cereal Food World. 1991;36(991–994):996. [Google Scholar]

- Gambus H, Mikuleci A, Gambus F, Pisulewski P (2004) Perspectives of linseed utilization in baking. Polish J Food and Nutri Sci 13/54 (1): 21–27

- Ganorkar PM, Jain RK. Flaxseed – a nutritional punch. Int Food Res J. 2013;20:519–525. [Google Scholar]

- Given PS. Influence of fat and oil – physicochemical properties on cookie and cracker manufacture. In: Faridi H, editor. The science of cookie and cracker production. New York: Champan and Hall; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez MI, Obilana AB, Martin DF, Madzvamuse M, Monyo ES (1997) Manual of laboratory procedures for quality evaluation of sorghum and pearl millet. p. 59 International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, Patancheru, Andhra Pradesh, India

- Greethead GF. The role of fats in bakery products. Food Technol in Aust. 1969;21:228–230. [Google Scholar]

- Hartnett DI, Thalheimer WG. Use of oil in baked products – Part I: background and bread. JAOCS. 1979;56:944–947. [Google Scholar]

- Hettiarachchy NS, Hareland GA, Ostenson A. Chemical composition of 11 flaxseed varieties grown in North Dakota. Proc of Flax Inst. 1990;53:36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Holm T, Andreassen AK, Aukrust P, Anderson K, Geiran OR, Kjekshus J, Simonsen S, Gullestad L. Omega-3 fatty acids improve blood pressure control and preserve renal function in hypertensive heart transplant recipients. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:428–436. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob J, Leelavathi K. Effect of fat type on cookie sough and cookie quality. J Food Eng. 2007;79:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2006.01.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamel BS. Creaming, emulsions, and emulsifiers. In: Faridi H, editor. The science of cookie and cracker production. New York: Chaman and Hall; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Knightly WH. Shortening systems: fat, oils and surface-active agents – present and future. Cereal Chem. 1981;58:171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Maache-Rezzoug Z, Bouvier JM, Allaf K, Patras C. Effect of principal ingredients on rheological behaviour of biscuit dough and on quality of biscuits. J Food Eng. 1998;35:23–42. doi: 10.1016/S0260-8774(98)00017-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madhusudhan B, Wiesenborn D, Schwarz J, Tostenson K, Gillespie J. A Dry mechanical method for concentrating the lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside in flaxseed. Lebensm -Wiss u-Technol. 2000;33:268–275. doi: 10.1006/fstl.2000.0652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masoodi L, Bashir-Khalid VA. Fortification of biscuit with flaxseed: biscuit production and quality evaluation. J Environ Sci, Toxicol and Food Technol. 2012;1:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Matz SA. Bakery technology and engineering. New York: Springer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Morris DH. Flax – a health and nutrition primer. 4. Winnipeg: Flax Council of Canada; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj G (1995) Quality and utility of oilseeds. Directorate of Oilseeds Research (Indian Council of Agricultural Research), Hyderabad. p. 44–46

- Pelser WM, Linssen JPH, Legger A, Houben JH. Lipid oxidation in ω- 3 fatty acid enriched Dutch style fermented sausages. Meat Sci. 2007;75:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic M, Kezic N, Bolanca V. Optimization of the GC method for routine analysis of the fatty acid profile in several samples. Food Chem. 2010;122:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajiv J, Indrani D, Prabhasankar P, Rao GV. Rheology, fatty acid profile and storage characteristics of cookies as influenced by flaxseed. J Food Sci Technol. 2012;49:587–593. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0307-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganna S. Hand book of analysis and quality control for fruit & vegetable products. New Delhi: Tata McGraw Hill Publication; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rennie KL, Hughes J, Lang R, Jebb SA. Nutritional management of rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the evidence. J Human Nutri Diet. 2003;16:97–109. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-277X.2003.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudan-Tasic D, Klofutar C. Characteristics of vegetable oils of some slovene manufacturers. Acta Chim Slov. 1999;46:511–521. [Google Scholar]

- Tsen CC, Bauck LJ, Hoover WJ. Using surfactants to improve the quality of cookies made from hard wheat flours. Cereal Chem. 1975;52:629–637. [Google Scholar]

- Wood JD, Richardson RI, Nute GR, Fisher AV, Campo MM, Kasapidou E, Sheard PR, Enser M. Effects of fatty acids on meat quality: a review. Meat Sci. 2004;66:21–32. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(03)00022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]