Abstract

Cashew apple bagasse is a byproduct of cashew peduncle juice processing. Such waste is a source of carotenoids, but it is usually discarded after the juice extraction. The objective of this work was to study the influence of pectinolytic and cellulolytic enzyme complexes on cashew bagasse maceration in order to obtain carotenoids. It was observed that maceration with the enzymatic complex Pectinex Batch AR showed a higher content of carotenoids, with an overall gain of 79 % over the control carried out without enzyme complex addition.

Keywords: Anacardium, Occidentale, Carotenoids, Maceration, Pectinases, Cellulases

Introduction

Cashew (Anacardium occidentale) is a typical fruit of the Brazilian Northeast and its cultivation has been gaining greater socioeconomic importance. Of the total produced annually in the Northeast, 15 % is utilized for juice manufacture, which is a great waste of raw material, since the weight of the bagasse corresponds to 90 % by weight of cashew (Paiva et al. 1998). The cashew’s peduncle bagasse is a source of polyphenols and carotenoids, compounds with high added value due to their functional properties in foods and power coloring (Abreu 2001), as well as a source of dietary fiber (Rufino et al. 2010).

Research involving antioxidant compounds from natural sources, such as carotenoids, have been developed in various centers of study because of their importance in the prevention of oxidative reactions (Broizoni et al. 2007). Aqueous enzymatic extraction has recently attracted a lot of interest because enzyme complexes, especially the pectinases, have been used for the following purposes: increasing the juice yield due to better packing of fruit: the liquefaction of fruit for the maximum utilization of raw materials; increasing the yield of fatty substance and of those that confer flavor and aroma; the clarification of juices; increasing stability; and breakdown down carbohydrate polymers such as pectins and hemicelluloses (Coelho et al. 2008, Ramadan et al. 2008). The use of enzymes with mixed activities (cellulases, hemicellulases and pectinases, mainly) hydrolyzes the structural polysaccharides of cell walls, releasing the cell contents which include carotenoids (Delgado-Vargas et al. 2000, Dominguez et al. 1995).

In earlier research, developed at Embrapa Tropical Agroindustry Barbosa (2010) studied the enzymatic pectinolytic complex Pectinex Ultra SPL to obtain carotenoids from cashew peduncle bagasse. Given the antioxidant activity of bioactive compounds present in cashew bagasse, such as carotenoids, beyond the power coloring compounds, this study investigating the influence of adding pectinolytic and cellulolytic enzyme complexes to cashew peduncle bagasse to assist in carotenoids obtention.

Materials and methods

Samples, chemical reagents and enzyme preparations

The cashew bagasse was kindly supplied by Brazil Juice industry, located in Pacajus, Ceará state, Brazil. The bagasse was stored in a freezer at −18 °C until processing. Analytical grade hexane, acetone, sodium phosphate dibasic heptahydrate, and sodium acetate were purchased from Impex. The glucose was purchased from Isofar. Citrus pectin and polygalacturonic acid were obtained from Sigma. Sodium hydroxide and dinitosalycilic acid were purchased from Vetec. The microcrystalline cellulose was obtained from Fluka. Pectinex AR Batch, Pectinex Ultra Clear, Pectinex Ultrazyme, Pectinex Smash XXL, Pectinex Ultra AFP, and Celluclast were kindly supplied by Novozymes Latin America LTDA. Pectinex AR Batch, Pectinex Ultra Clear, Pectinex Ultrazyme, Pectinex Smash XXL, and Pectinex Ultra AFP were produced from Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus aculeatus and Celluclast from Trichoderma reesei.

Determination of enzyme activity

Pectinesterase (PE) activity

Pectinesterase’s enzyme activity was determined by the presence of methanol released in the desesterificacion reaction of polygalacturonic acid followed by methodology proposed by Khanna et al. (1981) with modifications. The volume of 6 ml of enzymatic extract was added to 30 ml of 1 % pectin solution in sodium phosphate pH 7.0 buffer. The reaction medium was titrated by using NaOH 0.01 N. The unit of the pectinesterase enzyme was defined as U/ml, with a pectinesterase unit of 1 μmol of methanol released per minute in standard test conditions.

Polygalacturonase (PG) activity

The polygalacturonase enzyme was quantified according to Couri (1993) with modifications, using a rate of 0.1 ml of enzymatic extract in 4 ml of 0.25 % polygalacturonic acid in acetate sodium buffer 0.2 M pH 4.5. The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 35 °C in a Quimis bath model 0360 M2. A volume of 0.1 ml of the mixture was transferred to a tube containing 1 ml of DNS (dinitro-salicylic acid) and next the procedure for determination of reducing sugar according to Miller (1959) was followed. The enzyme activity was expressed as U/ml, with a polygalacturonase unit corresponding to 1 μmol galacturonic acid released per minute in the reaction conditions.

Cellulase activity

Cellulase activity was determined according to Wood and Garcia–Campayo (1990) with modifications. Aliquots of 0.9 ml of 1 % microcrystalline cellulose prepared in 50 mM acetate sodium buffer were acclimated in a water bath at 40 °C for 10 min. An aliquot of 0.1 ml of the enzyme complex was transferred to tubes and incubated at 40 °C for 60 min. A volum of 1 ml DNS (dinitro-salicylic acid) was transferred to each tube and next the reducing sugar was determined according to Miller (1959). The enzyme activity was expressed as U/ml, with a cellulase unit corresponding to 1 μmol glucose released per minute in the reaction conditions.

Enzymatic treatment

The bagasse was thawed at room temperature. Cashew bagasse (50 g) were added to 100 ml of water, which resulted in a ratio of 1:2 (bagasse weight: water weight). A volum of 50 μl commercial enzyme preparations were added to the mixture according to Table 1. The mixture was incubated and homogenized in an orbital shaker at 30 °C at of 150 rpm for 2 h to increase the surface area for efficient enzyme treatment. The time maceration of 2 h was chosen after the observation of instrumental color from extracts obtained by maceration in the times 30 min, 1 and 2 h. After 2 h of enzyme treatment, the mixture was vacuum filtered in a porcelain Buchner funnel with qualitative filter paper. The content of carotenoids in the extract was determined by the spectrophotometric method.

Table 1.

Experiments of maceration with commercial enzyme complex in peduncle cashew bagasse

| Experiment | Comercial enzyme complex |

|---|---|

| 1 | Control - No enzyme |

| 2 | 50 μl Petinex AR Batch |

| 3 | 50 μl Petinex Ultraclear |

| 4 | 50 μl Petinex Ultrazyme |

| 5 | 50 μl Petinex Smash XXL |

| 6 | 50 μl Petinex Ultra AFP |

| 7 | 50 μl Petinex AR Batch + 50 μl de Celluclast |

| 8 | 50 μl Petinex Ultra Clear + 50 μl de Celluclast |

Chemical analysis

Carotenoids

Determination of total carotenoids was performed according to Higby (1962). The extraction was performed using an isopropyl alcohol:hexane (3:1) solution. The content was transferred to a 125 ml separatory funnel wrapped in aluminum foil, where the volume was completed with distilled water. The mixture was left to sit for 30 min, followed by washing phases. This operation was repeated four more times. The content was filtered with cotton sprayed with anhydrous sodium sulphate into a 100 ml volumetric flask wrapped with aluminum foil, to which 5 ml acetone were added and diluted with hexane. The readings were made at 450 nm in a spectrophotometer model Varian Cary 50 and the results were expressed in mg/L.

Reducing sugar

Reducing sugar determination was measured by using the method described by Miller (1959). This method is based on the reduction by heating of 3,5- dinitro-salicylic acid into 3 amino 5 nitrosalicylic acid to the action of reducing sugar resulting in a brown complex which in turn is measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm. The absorbance reading was performed in a spectrophotometer model Varian Cary 50 in a glass bucket. The reducing sugar concentration was calculated from the calibration curve developed from a standard solution of glucose at a concentration of 1 mg/ml.

Color

The instrumental color of the clarified extract obtained after maceration was determined using a Minolta CR-300 colorimeter with values in L*, a* and b*. The Cielab (Commissioned International d’Eclairage) system allows its measurement to be made through the color parameters: L* brightness (0 = black and 100 = white), a*(−80 to zero = green and zero to +100 = red) and b* (−100 to zero = blue and zero to +70 = yellow).

Statistical analysis

The quantification of the carotenoid level for each treatment was performed in duplicate. Each treatment was performed by Tukey’s test (p < 0.05) to compare the efficiency of different enzyme complexes in the extraction of carotenoids. Statistical analyses were performed in the software Statistica version 7.0.

Results and discussion

Pectinesterase (PE), polygalacturonase (PG) and cellulose (CEL) activities of Pectinex AR Batch, Pectinex Ultra Clear, Pectinex Ultrazyme, Pectinex Smash XXL, Pectinex Ultra AFP and Celluclast are listed in Table 2. The enzyme complex that had the highest PE activity was Pectinex Ultra Clear (6.357 U/ml) followed by complex Pectinex Ultra AFP (5.130 U/ml), Pectinex Ultrazyme (4.294 U/ml) and Pectinex AR Batch (3.179 U/ml). The enzyme complex that presented the lowest PE enzymatic activity was Celluclast (808 U/ml). Pectinesterase catalyzes the hydrolysis of the methyl ester of pectin, thus releasing methanol and converting pectin into pactate (Uenojo and Pastore 2007). The highest polygalacturonase activity was found in Pectinex Ultrazyme (608 U/ml) followed by Pectinex Ultra Clear (428 U/ml). According to Uenojo and Pastore (2007), polygalacturonase enzyme hydrolyzes the links of α-1,4- glycosidic between two galacturonic acid residues, being the enzyme with the highest hydrolytic function. The enzyme complex that had the highest cellulose activity was Celluclast (16.5 U/ml) followed by Pectinex ultra Clear (9.0 U/ml) and Pectinex AR Batch (7.0 U/ml). Through treatment with pectinolytic and cellulolytic enzyme preparations, polysaccharides of the plant’s cell walls are partly depolymerized and solubilized to a different extent, releasing the interior contents of the cell (Dongowski and Sembries 2001).

Table 2.

Enzymatic activities of comercial complexes

| Sample | Activity (U/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PE | PG | CEL | |

| Pectinex AR Batch | 3.179 | 270 | 7,0 |

| Pectinex Ultra Clear | 6.357 | 428 | 9,0 |

| Pectinex Ultrazyme | 4.294 | 608 | 5,0 |

| Pectinex Smash XXL | 2.732 | N.D. | 4,0 |

| Pectinex Ultra AFP | 5.130 | 270 | 1,5 |

| Celluclast | 808 | N.D. | 16,5 |

It was observed that maceration with the enzymatic complex Pectinex AR Batch, test number 2, resulted in a higher content of carotenoids, followed by tests number 3 (Pectinex Ultra Clear), 7 (Pectinex AR Batch and Celluclast) and 8 (Pectinex Ultra Clear and Celluclast) Table 3. This was probably due to the action of pectinolytic enzyme complex that hydrolyze the pectin present in cell walls of cashew bagasse and facilitate the expulsion of the higher carotenoid content. The control, which was conducted without addition of enzymes, resulted in a content of 29.2 mg/l of carotenoids. The synergistic action of pectinolytic and cellulolytic enzyme complex used in tests number 7 and 8 also resulted in a gain of 54 and 70 % respectively, compared to the control test. The enzymatic complexes used in tests number 4, 5 and 6 did not show a good performance when applied to cashew bagasse to obtain carotenoids (Fig. 1). This was probably due to less activity related to the cellulose enzyme present in these complexes, hydrolyzing a lesser extent cellulose present in the bagasse and releasing less carotenoids. In previous studies in EMBRAPA, Barbosa (2010) applied 2.000 μl of pectinolytic complex enzyme Pectinex Ultra SPL tob macerated cashew bagasse, and analyzing the resulting extract from the pressing of macerated bagasse, it was observed that there was an overall percentage gain of 30 % in total carotenoids in relation to the control group without enzymes. Based on these results, it became necessary to study the application of other enzymatic compounds to obtain carotenoids from cashew bagasse. The results presented here indicate a better performance of complex Pectinex Ultra Clear and Pectinex AR Batch when applied to bagasse.

Table 3.

Significant difference in the amounts of carotenoids of the enzymatic treatement of cashew bagasse

| Test | Carotenóids Means (mg/L) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 29,2 c |

| 2 | 52,15 a |

| 3 | 47,3 a |

| 4 | 24,95 b, c |

| 5 | 17,8 b, c |

| 6 | 12,85 b |

| 7 | 45,05 a |

| 8 | 49,7 a |

Fig. 1.

Levels of carotenoids in mg/L resulting from the enzymatic maceration crushed cashew stalk with error bars of 5 %

Sun et al. (2006) studied the optimization of enzymatic maceration in pretreatment of carrot juice concentrate by response surface methodology and found the highest content of carotenoids with the application of 0.10 % of pectinase FNP-1 and 0.10 % of Celluclast FNC-1, wich resulted in 54.8 % gain. The result obtained in the present work was higher than the one obtained by that author probably due to the high efficiency of the enzymatic complex.

According to Çinar (2005), cellulase and pectinase hydrolyze pectin and pulp carotenoids releasing plant cell wall and increasing the efficiency of extraction. The author studied the concentration of carotenoids by measuring the absorbance values obtained from carrots, sweet potatoes, and orange peel macerated for 6, 12, 18 and 24 h. For the orange peel samples, the highest yield was achieved by using 5 ml/100 g wet peel pectinase and 0.1 g/100 g cellulase with 12 h extraction. For carrots, the author used a combination of 10 ml/100 g pectinase and 0.5 g/100 g of Celluclast in relation to the sample weight for a maceration time of 24 h and found a gain of 55 %. For sweet potatoes, the author studied the combination of 10 ml/100 g of pectinase and 1.0 g/100 g of cellulase and observed that the gain was 75 % for 18 h of maceration. Similar results were found in the present study, in which the treatment performed with the combination of Celluclast and Pectinex showed a gain of 70 % in the carotenoid content comparison with the control group, conducted without enzymes.

Roman-Salgado et al. (2008) studied the application of enzymes in non-commercial chili to obtain carotenoids by the spectrophotometric method and found values higher than 110 % in the control group. This value was higher than that found in the present work, due to differences in the studied material, the amount of enzymes, and maceration time.

Its was observed that there was not significant diference among treatments number 2, 3, 7 and 8, which showed the highest levels of carotenoids, indicating that in this study the best enzymatic complexes were Pectinex AR batch, Pectinex ultra Clear, and the combination Pectinases Cellulases (trials number 7 and 8). The other treatments did not show high levels of carotenoids (Table 1).

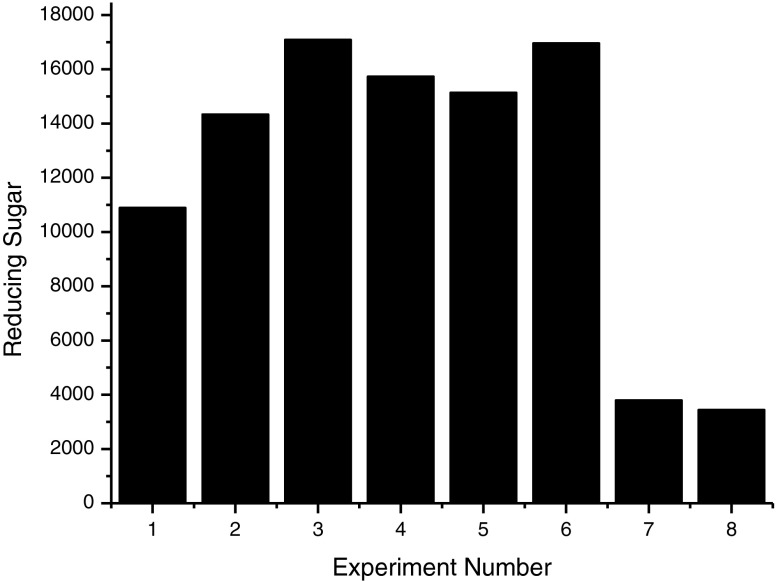

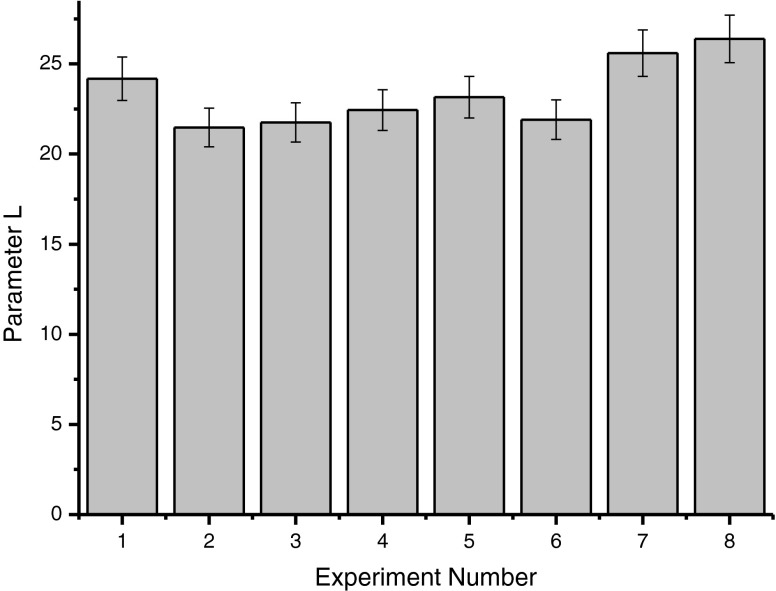

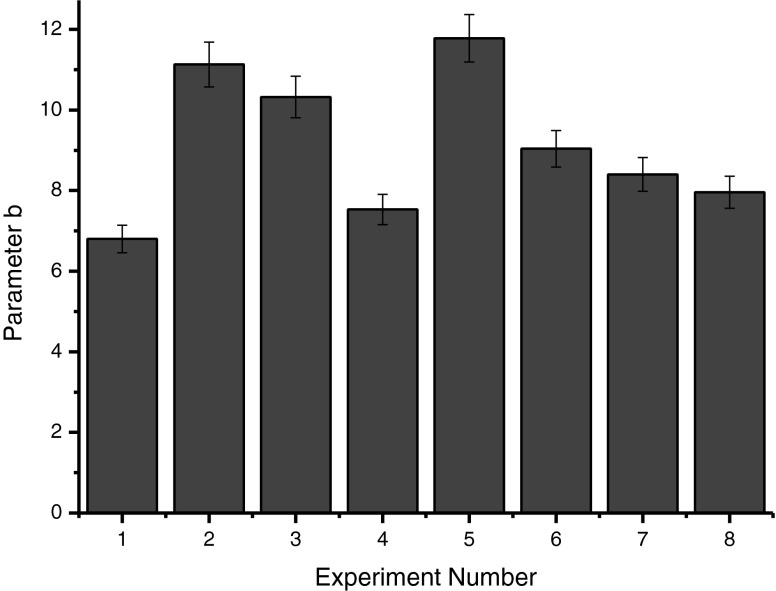

It was found that all tests conducted with enzymes, except for tests number 7 and 8, resulted in higher content of reducing sugar than the control without enzymes, and the highest concentrations of sugars were found in test number 3 (Pectinex Ultra Clear). Probably, there was the action of enzyme complexes on pectin, wich hydrolyzed and increased the amount of reducing sugars in these trials (Fig. 2). It was observed that for all tests the instrumental color parameter L, which indicates the brightness of the samples, was not different for Pectinex Ultraclear and Pectinex Smash XXL, which indicates that there was no sample considerably darker than the other (Fig. 3). The b value was higher in the sample macerated with Pectinex AR Batch, followed by Pectinex Ultraclear and Pectinex Smash XXL. In samples 2 and 3 those levels were higher due to the higher content of carotenoids, which contributed to a more intense yellow color in these samples (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Levels sugar’s reducing in mg/l resulting from the enzymatic maceration of the cashew apple pomace

Fig. 3.

Instrumental parameters L color resulting from enzymatic maceration of the cashew apple pomace with error bars of 5 %

Fig. 4.

Instrumental parameters b color resulting from the enzymatic maceration of the cashew apple pomace

Conclusions

It was observed that the use of enzymes available for the maceration of the stem of cashew bagasse peduncle for the extraction of carotenoid compounds was efficient, because the samples macerated with enzymes showed overall gains of up to 79 % (test number 2) compared to the experiment without the addition of enzymatic complex. The byproduct rich in carotenoids obtained from cashew bagasse presents potential use as a natural dye in food industry.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank INCT-Frutos Tropicais (CNPq) and Embrapa for the financial support of this work.

Contributor Information

Manuella Macedo, Email: manuellamacedoalimentos@yahoo.com.br.

Edy Sousa de Brito, Email: edy.brito@embrapa.br.

References

- Abreu FAP (2001) Extrato de bagaço de caju rico em pigmento. Patente Brasileira, n° PI 0103885–0.

- Barbosa MM. Production of Carotenoids and Flavonoids from the peduncle bagasse Cashew Enzyme for maceration and pressing. Master’s Thesis: Federal University of Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Broizoni PRB, Andrade-Warth ERS, Silva AM O e, Novo AJV, Torres RP, Azeredo HMC, Alves RE, Mancini-Filho J. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds naturally present in the pseudo-products of cashew. Int J Sci and Food Technol. 2007;7:902–908. [Google Scholar]

- Çinar I. Effects of cellulose and pectinase concentrations on the colour yield of enzyme extracted plant carotenoids. Process Biochem. 2005;40:945–949. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2004.02.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho MAS, Salgado AM, Ribeiro BD. Enzyme Technology. 1. Rio de Janeiro: FAPERJ; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Couri S (1993) Efeito de cátions na morfologia do agregado e na produção de poligalacturonase por Aspergillus niger mutante 3T5B8. PhD Thesis. Escola de Química/UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro.

- Delgado-Vargas F, Jiménez AR, Paredes-López O. Natural pigments: carotenoids, anthocyanins and betalains - characteristics, biosynthesis, processing, and stability. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2000;40:173–289. doi: 10.1080/10408690091189257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez H, Núñez MJ, Lema JM. Enzyme-extraction of soya bean assisted hexane oil. Food Chem. 1995;54:223–231. doi: 10.1016/0308-8146(95)00018-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dongowski G, Sembries S. Effects of commercial pectolytic and cellulolytic enzyme preparations on the apple cell wall. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:4236–4242. doi: 10.1021/jf001410+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higby WKA. A simplified method for the determination of some natural carotenoid distribuition in carotene and fortified orange juice. J Food Sci. 1962;27:42–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1962.tb00055.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna PK, Sethi RP, Tewari HK. Production poligalacturonase and pectin methyl esterase by aspergillus niger C1. J Res Punjab Agric Univ. 1981;18:415–420. [Google Scholar]

- Miller GL (1959) Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagents for determination of Reducing sugars. Analytical Chemistry.

- Paiva JR, Alves RE, Barros LM, Cavalcanti JJV, Almeida JHS, Moura CFH. Produção e qualidade de pedúnculos de clones de cajueiro-anão-precoce sob cultivo irrigado. Fortaleza: EMBRAPA-CNPAT; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan MF, Sitohy MZ, Moersel JT. Solvent and enzyme-aided aqueous extraction of gold enberry (Physalis peruviana L.) pomace oil: impact of processing on composition and quality of oil and meal. Eur Food Technol Res. 2008;226:1455–1458. doi: 10.1007/s00217-007-0676-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roman-Salgado M, Botello-Álvarez E, Rico-Martínez R, Jiménez I, Cárdenas-Manríquez M, Navarrete-Bolaños JL. Enzymatic treaetment to improve extraction of capsaicinoids and carotenoids from chili fruits. J of Agri and Food Chem. 2008;56:10012–10018. doi: 10.1021/jf801823m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufino MSM, Pérez-Jiménez J, Tabernero M, Alves RE, Brito ES, Saura-Calixto F. Acerola and cashew apple as sources of antioxidants and dietary fibre. Int Food and Sci & Technol. 2010;45:2227–2233. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2010.02394.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Wang Z, Wu J, Chen F, Liao X, Hu X. Optimising enzymatic maceration in pretreatment of carrot juice concentrate by response surface methodology. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2006;41:1082–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2006.01182.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uenojo M, Pastore GM. Pectinases: aplicações industriais e perspectivas. Quim Nova. 2007;30:388–394. doi: 10.1590/S0100-40422007000200028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wood TM, Garcia–Campayo V. Enzimology of cellulose degradation Biodegradation Dordrecth. 1. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]