Abstract

Subcritical water extraction (SWE) of phenolics was investigated from marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) flower residues. The total phenolics content (TPC), total flavonoids content (TFC) and antioxidant capacities of extracts were determined, furthermore, antioxidant activities of individual compounds were evaluated with on-line HPLC–ABTS•+ system. The optimum SWE time was 45 min, solid-to-liquid ratio was 1:50, and the highest TPC and TFC were obtained at 220 °C respectively. The effect of SWE temperature on TPC and TFC was significant (p < 0.05), and TPC was ranged from 28.42 ± 0.94 to 124.27 ± 1.94 (mg GAE/g), and TFC ranged from 34.21 ± 0.36 to 133.22 ± 1.57 (mg GAE/g) between 80 and 220 °C. On-line HPLC–ABTS•+ profiles revealed that quercetagetin from SWE at 200 °C had nearly twofold radical scavenging activities than that by leaching extraction.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13197-014-1449-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Marigold flower residues, Subcritical water extraction (SWE), Phenolic compounds, Antioxidant activity, On-line HPLC-ABTS·+

Introduction

Marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) flower, including many species, has been usually used as a traditional medicine and a common ornamental plant around the world (Vasudevan et al. 1997). Most studies on marigold flower were focused on the extraction of lutein esters/oleoresin (Campos et al. 2005; Gao et al. 2009; Gong et al. 2011), the residues after extracting oleoresin were usually discarded or only used as a fertilizer and animal feed. Apart from the health-benefiting lutein, some other secondary metabolites, like polyphenols and flavonoids, contribute to the health-promoting activities as well (Lu and Foo 2000). The antioxidant activity of marigold extract was in correlation with the content of polyphenols and flavonoids (Cetkovíc et al. 2004; Li et al. 2007). To investigate the bioactive substances, some research work, such as the isolation of the polyphenols and flavonoids, was carried out (Parejo et al. 2005; Aquino et al. 2002; Gong et al. 2012). The quercetagetin, one of the flavonoids in marigold flowers, exhibited excellent antioxidative capacity on eliminating free radicals (Gong et al. 2012). However, a separation method without organic solvent is appealing for green process and practical manufacturing. Subcritical water extraction (SWE) is such a separation method with outstanding merits of benign to environment and competitive running cost (Ramos et al. 2002).

SWE has been successfully applied to extract volatiles and bioactive substances from plants (Phattarakorn et al. 2008). It has been proved that SWE was an efficient method in extracting phenols such as anthraquinone, xylogen and flavones (Pongnaravane et al. 2006; Anekpankul et al. 2007; Shotipruk et al. 2004; Kim and Mazza 2006; Cacace and Mazza 2006; Rodríguez-Meizoso et al. 2006). He et al. (2012) evaluated the phenolic components extracted by SWE from pomegranate and their antioxidant activities with on-line HPLC-ABTS·+ assay. The results showed that the total phenols content and their antioxidant capacities were remarkably affected by the temperature of subcritical water.

The objectives of this work were to investigate the feasibility of extracting phenolic compounds from marigold flower residues using SWE and to assess the antioxidant activities of phenolic compounds in the extracts prepared by SWE and conventional method

Materials and methods

Materials

Folin-ciocalteu’s phenol reagent (2 N), 6-hydroxyl-2,5,7,8-tetramethyl-chroman-2 -carboxylic acid (Trolox), 2,2′-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), gallic acid, rutin, 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS), D-glucose, and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (5-HMF) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All the HPLC grade solvents were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). All other analytical grade chemicals and solvents were obtained from Beijing Chemical Co. (Beijing, China).

Marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) flower granules were offered by Saite Natural Pigments Co. (Qingdao, China). The marigold flower granules, moisture content of 7.11 %, were firstly crushed into 0.25–0.35 mm particles, and then defatted by n-hexane with Soxhlet-extractor. After the oleoresin was removed, marigold flower residues were obtained and darkly stored at room temperature until used.

Subcritical water extraction (SWE)

The SWE apparatus (300 mL sample capacity, Model CWYF-2, Nantong, China) applied in this study was same as described by He, et al. (2012). Sample of ground marigold flower residues was placed in the stainless steel extraction vessel. The extraction vessel was warmed up with a heating jacket, and the vessel was sealed with stainless steel cap and connected with pressure and temperature sensors. When the temperature of the vessel was heated to the designed value, deionized water was pumped into the extraction vessel at a constant flow via a preheater. At the same time, the nitrogen (N2) was used to maintain an oxygen-free environment and appropriate pressure. Besides, counterbalance valve could regulate the pressure as well. Switching on the magnetic stirrer was to enhance the mass transfer. The desired temperature and pressure were respectively kept within an accuracy of ± 0.5 °C and ± 0.5 MPa.

The experiments were carried out by loading 4.0 g of marigold flower residues and setting the speed of stirrer at 120 rpm. The extraction parameters were temperature from 80 to 260 °C, solid-to-liquid ratio from 1:20 to 1:60 (m/v), and time from 15 to 90 min. The extracts were evaporated to dry under vacuum and re-dissolved in 70 % ethanol solution. After that, the re-dissolved extracts were treated in centrifuge at 3,528 g for 15 min. The total volume of the supernatants was diluted to a graduation of 100 mL. All samples were stored in amber bottle at −18 °C until analysis.

For comparative experiments, 4.0 g of defatted marigold flower residues powder was extracted at 50 °C with 150 mL of water, methanol, ethanol solution (70 % in water, v/v) and acetone solution (60 % in water, v/v) respectively. The comparative extraction experiments included leaching (2 h) with an agitation at 120 r/min and ultrasonic assisted extraction (20 kHz, 650 W, 50 °C, 45 min). After extraction, all the extracts were treated by aforementioned procedures.

Analysis of total phenolics content (TPC)

TPC was determined following the method described by Vatai et al. (2009). Appropriately the diluted extract (0.5 mL) was mixed with Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (2.5 mL, 0.2 N), and 2.0 mL of sodium carbonate (7.5 %, w/v) was added 5 min later. After shaken well, the mixture was kept at ambient temperature for 2 h. The absorbance at 754 nm was recorded with a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800, Tokyo, Japan). A 0.5 mL of the diluted sample was replaced by distilled water in a reagent blank. The result of TPC was expressed in mg gallic acid equivalent per gram of dry weight (mg GAE/g).

Determination of total flavonoids content (TFC)

TFC was measured according to the procedure described by Siddhuraju and Becker (2003). Appropriately the diluted sample (0.5 mL), distilled water (3.5 mL) and sodium nitrite (0.3 mL) were perfectly mixed together in a test tube (10 mL). After 5 min, aluminum chloride solution (3 mL, 1 %, w/v) was added and 6 min later, sodium hydroxide solution (2 mL, 4 %, w/v) was put in with fully shaking, and diluted to 10 mL with distilled water. The absorbance at 510 nm was measured after 15 min. A 0.5 mL of the diluted sample was replaced by distilled water in a reagent blank. The result of TFC was expressed in mg rutin equivalent per gram of dry weight (mg RE/g).

Evaluation of antioxidant capacity

To investigate the antioxidant activity, the first assay was based on the method described by Pellegrini et al. (2001). ABTS (10 mg) was dissolved in potassium persulfate solution (2.6 mL, 2.45 mmol/L) to prepare the stock solution. The mixture was kept in dark place at room temperature overnight. This solution was diluted in methanol to obtain an absorbance of 0.7 ± 0.02 measured at 747 nm. One milliliter of the diluted sample was added with 3.0 mL ABTS·+ solution and kept in dark at room temperature for 1 h. The absorbance was measured at 747 nm.

Another radical scavenging test on DPPH eliminating was carried out according to the method described by Ramadan et al. (2003). The stock solution of DPPH · (1.75 × 10−4 mol/L) was freshly prepared by adding 2 mg DPPH in 50 mL methanol. DPPH solution (2.0 mL) and appropriately diluted sample (2.0 mL) were fully mixed at ambient temperature (ca. 21 °C). The reaction was lasted for 1 h in dark and the absorbance was measured at 517 nm.

In both of the two assays aforementioned, Trolox was used as a standard reference, and the result of the free radical scavenging capacity (also called Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity, TEAC) was expressed in mmol Trolox equivalent per gram of dry weight (mmol TE/g).

Investigation into Maillard reaction products

To analyze the Maillard reaction products in extracts from SWE, the absorbance at 420 nm and 280 nm, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (5-HMF), total reducing sugar and total free amino acids were detected.

Detection of intermediates and final products of Maillard reaction

The intermediate compounds of Maillard reaction were estimated by measuring the absorbance of appropriately diluted extract at 280 nm (A280) (Xu et al. 2008) and the concentration of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (5-HMF) in the extract was analyzed by a high performance liquid chromatography system (HPLC, Agilent 1,100 series, America) following the method described by Damasceno et al. (2008) with minor modification. A 10 μL of the sample was injected and eluted with a solvent system of water (A) and methanol (B). The mobile phase was controlled as an elution (A : B = 85 : 15) and the flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. The temperature of Zorbax SB C-18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm i.d., 5 μm, Agilent, America) was kept at 35 °C. 5-HMF level was monitored at 280 nm and quantification was carried out by an external authentic. The content of 5-HMF was expressed in μg per gram of dry weight (μg/g).

Absorbance at 420 nm (A420), as an indication of the brown polymers formed in advanced stages of non-enzymatic browning reaction, was measured at room temperature by a UV-1800 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, China). All samples were filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane before the measurement.

Measurement of total reducing sugars (TRS) content

The analysis of TRS content was conducted by a method proposed by Miller and Hawthorne (1998) Appropriately the diluted extract (0.5 mL) was added to DNS reagent (0.5 mL) and reacted in boiling water for 5 min. After cooling, distilled water was added to make a constant volume of 5 mL. The absorbance at 540 nm was determined. A 0.5 mL of the diluted sample was replaced by distilled water in a reagent blank. The TRS content was expressed in mg D-glucose equivalent per gram of dry weight (mg DE/g).

Detection of total free amino acids (TAA)

TAA content was estimated according to the method described by Chen et al. (2009). Appropriately the diluted sample (1.0 mL), phosphate buffer (0.5 mL, pH = 8.0) and ninhydrin solution (0.5 mL, 0.2 %, w/v) containing SnCl2 (0.8 mg/mL) were mixed and kept in boiling water (15 min). After cooling and adding distilled water, the total volume was set to 25 mL. The absorbance at 568 nm was measured. A 1.0 mL of the diluted sample was replaced by distilled water in a reagent blank. The TAA content was expressed in mg L-glutamic acid equivalent per 100 g of dry weight (mg/100 g).

On-line HPLC-ABTS·+ assay

The antioxidant activity of individual compounds was monitored by the Agilent 1,100 HPLC-DAD equipment. The extract was separated with a Zorbax SB C-18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm i.d., 5 μm, Agilent, America), which was kept at 40 °C. The mobile phase consisted of acidified water (0.5 % acetic acid in water, v/v, solvent A) and methanol (solvent B). The elution gradient was: Solvent B was initially set 5 %, solvent A was 95 %, then solvent B increased to 15 % in the first 15 min and solvent A decreased to 85 %, then solvent B raised to 45 % and solvent A decreased to 55 % at 30 min, then solvent B raised to 55 % and solvent A decreased to 45 % at 40 min, then solvent B increased to 85 % and solvent A decreased to 15 % at 50 min, then solvent B increased to 100 % and solvent A decreased to zero at 60 min. The flow rate was maintained at 0.7 mL/min and then the elution was linked to a reaction coil (15 m × 0.25 mm), which was dominated by a temperature controller (Waters Corporation, USA). At the same time, ABTS·+ solution described previously was transported via a pump (Waters Corporation, USA) to the reaction coil at 0.5 mL/min. In the reaction coil (40 °C), each fraction in sequence was reacted with the working solution of ABTS·+. Finally, the reaction mixture was delivered into the DAD recording at 280 nm (for positive peaks) and 734 nm (for negative peaks). Agilent Chemistation Software was used for analyzing data.

Statistical analysis

All results were presented as the means ± standard deviation. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance using the SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and the means were determined by Duncans’s multiple range test. The correlations analysis was carried out using the Pearson mode.

Results and discussion

Subcritical water extraction

The influence of the extraction temperature on TPC and TFC

Subcritical water extraction (SWE) of total phenolics and total flavonoids from marigold flower residues was investigated at 80 °C-260 °C for 45 min (solid-to-liquid ration of 1:50, w/v). Fig. 1a shows that TPC was affected by the extraction temperature significantly (p < 0.05). When the extraction temperature was elevated from 80 to 220 °C, a substantial increase of TPC was observed. However, a further rise of extraction temperature from 220 to 260 °C induced a decline of TPC. The minimum and maximum TPC were 28.42 ± 0.94 mg GAE/g at 80 °C and 124.27 ± 1.94 mg GAE/g at 220 °C respectively. The result indicated that total phenolics exhibited a larger solubility at higher temperature in subcritical water. With the elevation of extraction temperature from 80 to 220 °C, the dielectric constant (ε) of the subcritical water was decreased from 61 to 31 (Yang et al. 1998; Miller and Hawthorne 1998). Under this condition, the dielectric constant of subcritical water (ε = 31) was pretty closed to the permittivity of ethanol (ε = 25) or methanol (ε = 33) (Åkerlöf 1932; Fernández et al. 1997). Subcritical water could enhance the solubility of phenolic components just as an organic solvent. At the same time, higher temperature possibly led to further degradation and reactions of some phenolic substances, and the contribution of decreasing dielectric constant to total phenolics extraction was less effective. Therefore, TPC was reduced at the temperature from 220 to 260 °C.

Fig. 1.

Effect of different extraction parameters on TPC and TFC in the extracts from marigold flower residues: (a), temperature, (b) solid-to-liquid ratio and (c) extraction time

Some studies demonstrated that dietary fiber extracted from plant resources was rich in phenolic substances, thus, it has been regarded as a dietary source of antioxidants (Saura-Calixto 1998). SWE was considered as a good technique for increasing solubility of dietary fiber (Wakita et al. 2004). The phenolic compounds might be conjugated with proteins and polysaccharides by ester and ether bonds. Subcritical water could induce hydrolysis of dietary fiber and release of more free phenolics from matrices (Kim and Mazza 2006), which might result in an increase of TPC from 80 to 220 °C. However, the degradation of phenolics was also attributed to higher temperature.

A similar result of TFC was also observed. The only difference was that there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) between data of TFC at 200 and 220 °C.

The influence of solid-to-liquid ratio on TPC and TFC

Fig. 1b shows the effect of solid-to-liquid ratio on TPC and TFC at 200 °C for 45 min, and the solid-to-liquid ratio affects TPC significantly (p < 0.05). TPC and TFC reached the highest level with the ratio of 1:50, and then decreased slightly. This result was different from the phenolics extraction from Inga edulis leaves, which showed lower solid-to-liquid ratio led to higher concentration of the phenolics (Silva et al. 2007). With the consideration of the extraction efficiency and cost, a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:50 was preferred.

The influence of extraction time on TPC and TFC

As shown in Fig. 1c, the effect of SWE time on TPC and TFC was carried out at 200 °C with the solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:50. The highest level of TPC and TFC were 116.61 ± 1.92 mg GAE/g and 138.59 ± 2.03 mg RE/g obtained at 45 min respectively, then decreased with a further extension of extraction time. Figure 1c also shows that the content of phenolics was increased significantly (p < 0.05) in the early extraction stage (0–45 min) and decreased later (45–90 min). It might be owing to the degradation of phenolic compounds with the extension of extraction time (Chirinos et al. 2007). Extraction time was crucial for TPC because it might be controlled by the equilibrium concentration in the extraction process (Spigno et al. 2007). Therefore, it was unsuitable for longer period of extracting phenolics. Previously study revealed that solubility of phenolics, phenolic polymerization and interaction between phenolics and other components could make extraction equilibrium time different (Silva et al. 2007). Finally, the extraction time of 45 min was preferred for SWE of phenolics from marigold flower residues.

Comparison between SWE and other extraction methods

In the preliminary extraction experiments (data not shown), water, methanol, 70 % ethanol solution, and 60 % acetone solution, as solvents, were compared on the extraction of phenolics.

As shown in Table 1, TFC, TPC, DPPH · -TEAC and ABTS∙+-TEAC of extracts from SWE were 11, 11, 17 and 13 times, respectively, higher than those leached using water. TPC, DPPH · -TEAC and ABTS∙+-TEAC of extracts obtained by SWE were similar to those prepared by acetone solution (60 %) leaching, and were significant (p < 0.05) higher than those extracted with methanol and ethanol solution (70 %). The type and polarity of extraction solvents were the foremost factor monitoring extraction efficiency (Ko et al. 2011). Under 200 °C, the dielectric constant of subcritical water could be 35, similar to that of 60 % acetone solution (43), which might dissolve many compounds than normal water (Cacace and Mazza 2006).

Table 1.

TPC, TFC and TEAC of extracts from marigold (Tagetes ereta L.) flower residues with different extraction methods

| Methods | TFC (mg RE/g) | TPC (mg GAE/g) | DPPH · -TEAC (mmol TE/g) | ABTS∙+-TEAC (mmol TE/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaching (50 °C, 2 h) | ||||

| Water | 12.78 ± 0.20a | 10.94 ± 0.69a | 0.14 ± 0.01a | 0.20 ± 0.03a |

| Methanol | 94.81 ± 1.27b | 84.25 ± 0.75cde | 1.51 ± 0.02cde | 1.90 ± 0.03d |

| Ethanol (70 %) | 93.40 ± 2.25bc | 83.37 ± 2.69cd | 1.50 ± 0.05cd | 1.97 ± 0.05de |

| Acetone (60 %) | 127.54 ± 2.46e | 96.66 ± 1.92f | 1.69 ± 0.04d | 2.15 ± 0.01fg |

| Ultrasonic Assisted Extraction (50 °C, 45 min) | ||||

| Water | 13.47 ± 0.30a | 12.17 ± 0.42a | 0.41 ± 0.01ab | 0.48 ± 0.05b |

| Methanol | 94.61 ± 2.13bc | 82.35 ± 2.53c | 1.52 ± 0.02cdef | 2.14 ± 0.04f |

| Ethanol (70 %) | 87.26 ± 1.64f | 73.68 ± 1.43b | 1.32 ± 0.05c | 1.64 ± 0.05c |

| Acetone (60 %) | 118.82 ± 3.67g | 89.02 ± 3.17cdef | 1.61 ± 0.06cdefg | 2.23 ± 0.06fg |

| SWE (200 °C, 45 min) | ||||

| 135.64 ± 1.94h | 116.31 ± 1.94g | 2.42 ± 0.22h | 2.67 ± 0.09h | |

aAll results expressed were means ± standard deviation of at least triplicate experiments, with different superscript letters marked in each column that were significant different (p < 0.05). The concentration of solvents expressed were volume percentage (v/v) in water; the results of TPC were expressed in mg gallic acid equivalent per gram of dry weight (mg GAE/g); the results of TFC were expressed in mg rutin equivalent per gram of dry weight (mg RE/g). Both values of DPPH · -TEAC and ABTS∙+-TEAC were expressed as Trolox equivalent per gram of dry weight (mmol TE/100 g)

There was no significant difference (p > 0.05) of TPC in the extracts obtained with ultrasound assisted extraction and single leaching in Table 1. However, TPC, TFC and antioxidant capacities of extracts with SWE were higher than those obtained by two other extraction methods. In addition, SWE processing time was remarkably shortened (45 min). Therefore, SWE could be considered as a high efficient method for the extraction of phenolic compounds from marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) flower residues.

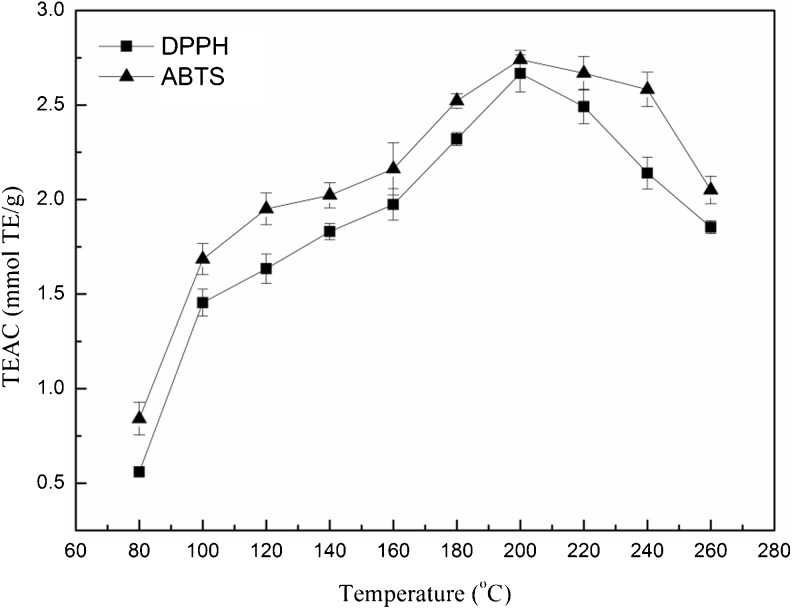

Evaluation of the antioxidant capacities of the extracts

The antioxidant capacities of the extracts from marigold flower residues were evaluated by ABTS and DPPH assays. As shown in Fig. 2, TEAC of the extracts were significantly (p < 0.05) affected by SWE temperature. This result was in agreement with previous studies. In the extraction of pomegranate seed oil and phenolic compounds from parsley, the temperature had a stronger effect on the yield compared to extraction time and solid-to-liquid ratio (Abbasi et al. 2008; Luthria 2008). The highest values of TEAC of extracts from SWE were 2.74 ± 0.05 mmol TE/g (ABTS) and 2.66 ± 0.10 mmol TE/g (DPPH) respectively when the extraction temperature was 200 °C, and the TEAC values were significantly (p < 0.05) higher than those obtained with optimal ethanol solution extraction (Gong et al. 2012). TEAC of the extracts from SWE was increased with the rise of extraction temperature from 80 to 200 °C, and then decreased from 200 to 260 °C.

Fig. 2.

Effect of different extraction temperatures on total antioxidant capacity of the extracts from marigold flower residues

The correlation coefficients (R2) of the TEAC and TPC curves in Figs. 1a and 2 were 0.9315 (ABTS) and 0.9415 (DPPH). These results indicated that the antioxidant capacity of the marigold extracts was related to TPC. Phenolics and flavonoids have been reported as antioxidants in many studies (Bohm and Stuessy 2001; Lu and Foo 2000). In addition, R2 values between 200 and 260 °C were lower than those from 80 to 200 °C, which might imply that some non-phenolic antioxidant substances were generated during the extraction (He et al. 2012).

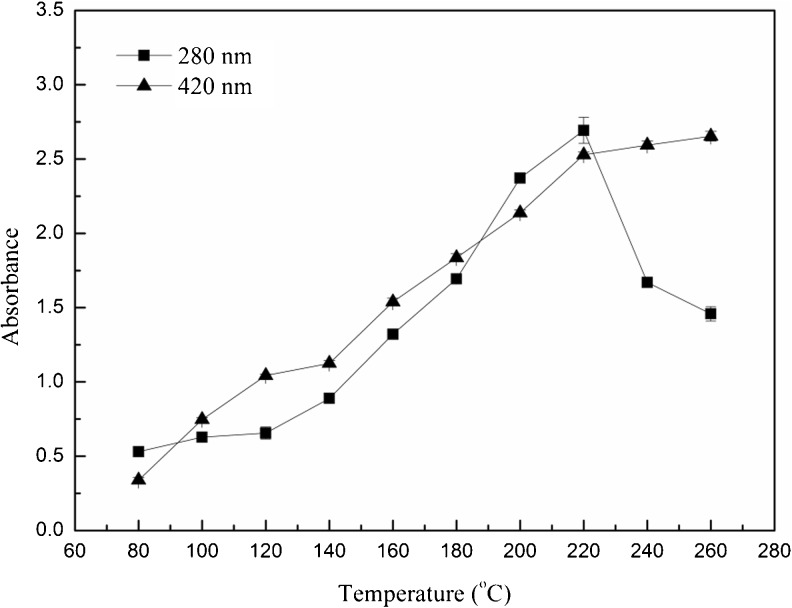

Investigation into Maillard reaction products (MRPs)

It is well known that MRPs with different structures and characteristics exhibited antioxidant capacity. Many studies revealed that MRPs contributed to the total antioxidant activity of thermally processed food. However caramelization products might be generated at high temperature during SWE (Phongkanpai et al. 2006). Analysis of MRPs was necessary for the investigation into the non-phenolic antioxidant components during SWE.

Absorbances at 280 nm (A280) and 420 nm (A420) were usually used to monitor intermediate and final products of Maillard reaction (Xu et al. 2008). As shown in Fig. 3, A280 of the extracts was significantly (p < 0.05) increased at temperatures from 80 to 220 °C and then dropped at higher temperatures (220 °C - 260 °C). This result indicated that intermediate compounds were formed during SWE and decomposed at 220 °C (Kim and Lee 2009). Formation of melanoidins was determined by measuring A420 of browning, which provided a visual estimation of the consequence of Maillard reaction. The intensity of browning namely A420 was increased significantly (p < 0.05) with the rise of extraction temperatures from 80 to 260 °C. This result was in accordance with that reported by He et al. (2012).

Fig. 3.

Effect of different extraction temperatures on A280 and A420 of the extracts from marigold flower residues

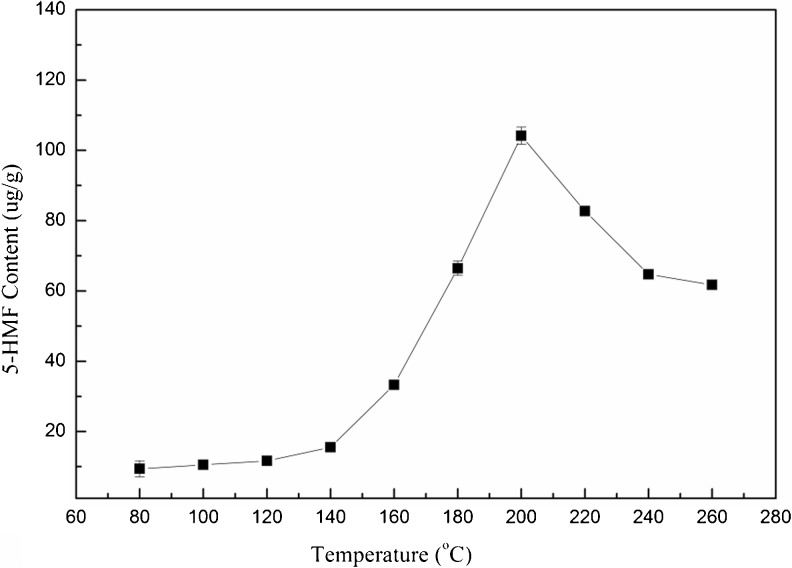

5-HMF, an important intermediate products formed in Amadori rearrangement during Maillard reaction, had a certain antioxidant activity. As shown in Fig. 4, the content of 5-HMF was increased from 9.38 ± 1.22 μg/g to 104.16 ± 2.45 μg/g with the elevation of extraction temperatures from 80 to 200 °C. This result was in agreement with that reported by Capuano et al. (2008). However, the concentration of 5-HMF started to decrease from 200 °C. Polymerization and reaction of 5-HMF with other compounds might contribute to the reduction of 5-HMF (Sasaki et al. 2000).

Fig. 4.

Effect of different extraction temperatures on 5-HMF accumulation in the extracts from marigold flower residues

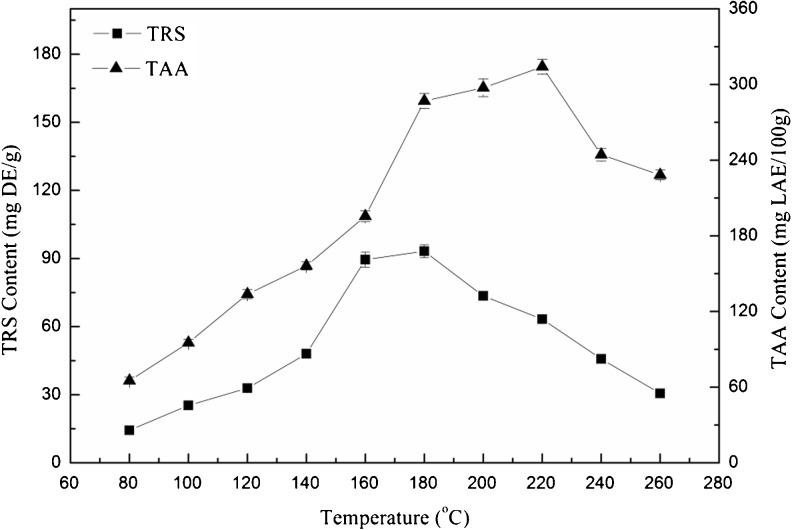

Analysis of total reducing sugars (TRS) and total free amino acids (TAA)

As shown in Fig. 5, TRS and TAA reached the highest value at 180 °C (no difference with TRS value at 160 °C) and 220 °C, respectively. The maximal contents of TRS (93.23 ± 1.84 mg DE/g) and TAA (305.35 ± 5.76 mg GAE/100 g) were lower than those from pomegranate seed residues extracted with subcritical water at 180 °C (He, et al. 2012). The effect of extraction temperature on the contents of TRS and TAA in the extracts might be due to the Maillard reaction and their high solubility in subcritical water. Marigold flower residues were rich in polysaccharide (such as lignin, cellulose) and crude protein (Parejo et al. 2005), while subcritical water had a lower polarity for better dissolving organic bioactive compounds (Ibanez et al. 2003). When the extraction temperature was increased, water ionization constant (Kw) became higher. And it led to high concentration of H+ and OH−, which catalyzed the hydrolysis of polysaccharides and crude proteins into small molecules (such as oligosaccharides, monosaccharides and peptides, amino acids) (Sereewatthanawut et al. 2008). The concentrations of reducing sugars and free amino acids were firstly increased with extraction temperature, meanwhile their participation in the Maillard reaction will ultimately reduced their contents in the extract at temperatures over 180 °C (reducing sugars) and 220 °C (amino acids) respectively.

Fig. 5.

Effect of different extraction temperatures on TRS and TAA contents in the extracts from marigold flower residues

Antioxidant activity evaluation and identification

Bioactive compounds in the extracts obtained by leaching with 60 % acetone solution and subcritical water extraction at 200 °C were evaluated by on-line HPLC-ABTS·+ technique, and the results were presented in Fig. 6 and the numbers of components exhibiting ABTS radical scavenging activities were different. In the extract with 60 % acetone solution, there were six components compared to eight components in that with subcritical water. Peak area of compound 2 in chromatographic profiles was maximal. Compound 1 was indentified as 5-HMF by comparing with authentic reference. Compounds 2, 3, 5, 6 were identified as quercetagetin, 6-hydroxykaempferol-3-O-hexoside, quercetin and patuletin-7-hexoside in accordance with our preciously study (Gong et al. 2011). Fig. 6 shows that compound 2 in the extract by SWE had nearly two fold radical-scavenging activity than that with 60 % acetone solution in traditional way, which meant water in subcritical state had stronger dissolving capacity than 60 % acetone solution (Ramos et al. 2002).

Fig. 6.

On-line HPLC-ABTS•+ chromatographic profiles of extracts obtained by leaching with 60 % acetone solution and SWE at 200 °C

SWE would be an optimal processing for the extraction of phenolics and flavonoids from marigold flower residues, especially for the production of quercetagetin, the strongest scavenging free radical component from marigold flower residues.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOC 170 kb)

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Special Program for International S&T Cooperation and Exchanges (CN-SLO 9-21/2011).

References

- Abbasi H, Rezaei K, Emamdjomeh Z, Ebrahimzadeh Mousavi SM. Effect of various extraction conditions on the phenolic contents of pomegranate seed oil. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2008;110:435–440. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.200700199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Åkerlöf G. Dielectric constants of some organic solvent–water mixtures at various temperatures. J Am Chem Soc. 1932;54:4125–4139. doi: 10.1021/ja01350a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anekpankul T, Goto M, Sasaki M, Pavasant P, Shotipruk A. Extraction of anti-cancer damnacanthal from roots of Morinda citrifolia by subcritical water. Sep Purif Technol. 2007;55:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2007.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aquino R, Cáceres A, Morelli S, Rastrelli L. An extract of Tagetes lucida and its phenolic constituents as antioxidants. J Nat Prod. 2002;65:1773–1776. doi: 10.1021/np020018i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm BA, Stuessy TF. Flavonoids of the sunflower family (Asteraceae) Wien: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cacace JE, Mazza G. Pressurized low polarity water extraction of lignans from whole flaxseed. J Food Eng. 2006;77:1087–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.08.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campos L, Michielin E, Danielski L, Ferreira S. Experimental data and modeling the supercritical fluid extraction of marigold (Calendula offcinalis) oleoresin. J Supercrit Fluid. 2005;34:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2004.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capuano E, Ferrigno A, Acampa I, Ait-Ameur L, Fogliano V. Characterization of the Maillard reaction in bread crisps. Eur Food Res Technol. 2008;228:311–319. doi: 10.1007/s00217-008-0936-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cetkovíc GS, Djilas SM, Canadanovi’c-Brunet JM, Tumbas VT. Antioxidant properties of marigold extracts. Food Res Int. 2004;37:643–650. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2004.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Chen Q, Zhang Z, Wan X. A novel colorimetric determination of free amino acids content in tea infusions with 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene. J Food Compos Anal. 2009;22:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2008.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chirinos R, Rogez H, Campos D, Pedreschi R, Larondelle Y. Optimization of extraction conditions of antioxidant phenolic compounds from mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum Ruíz & Pavón) tubers. Sep Purif Technol. 2007;55:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2006.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damasceno LF, Fernandes FAN, Magalhães MMA, Brito ES. Non-enzymatic browning in clarified cashew apple juice during thermal treatment: kinetics and process control. Food Chem. 2008;106:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.05.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández DP, Goodwin ARH, Lemmon EW, Levelt Sengers JMH, Williams RC. A formulation for the static permittivity of water and steam at temperatures from 238 K to 873 K at pressures up to 1,200 MPa, including derivatives and Debye-Hückel coefficients. J Phys Chem Ref Data. 1997;26:1125–1166. doi: 10.1063/1.555997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Liu X, Xu H, Zhao J, Wang Q, Liu G, Hao Q. Optimization of supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of lutein esters from marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) with vegetable oils as continuous co-solvents. Sep Purif Technol. 2009;71:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2009.11.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Plander S, Xu H, Simandi B, Gao Y. Supercritical CO2 extraction of oleoresin from marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) flowers and determination of its antioxidant components with online HPLC-ABTS·+ assay. J Sci Food Agr. 2011;91:2875–2881. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Hou Z, Gao Y, Xue Y, Liu X, Liu G. Optimization of extraction parameters of bioactive components from defatted marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) residue using response surface methodology. Food Bioprod Process. 2012;90:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2010.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Zhang X, Xu H, Xu C, Yuan F, Knez Z, Novak Z, Gao Y. Subcritical water extraction of phenolic compounds from pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) seed residues and investigation into their antioxidant activities with HPLC-ABTS•+ assay. Food Bioprod Process. 2012;90:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2011.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez E, Kubatova A, Senorans FJ, Cavero S, Reglero G, Hawthrone SB. Subcritical water extraction of antioxidant compounds from rosemary plants. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:375–382. doi: 10.1021/jf025878j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Lee YS. Study of Maillard reaction products derived from aqueous model systems with different peptide chain lengths. Food Chem. 2009;116:846–853. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.03.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Mazza G. Optimization of extraction of phenolic compounds from flax shives by pressurized low-polarity water. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:7575–7584. doi: 10.1021/jf0608221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko MJ, Cheigh CI, Cho SW, Chung MS. Subcritical water extraction of flavonol quercetin from onion skin. J Food Eng. 2011;102:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2010.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Gao Y, Zhao J, Wang Q. Phenolic, flavonoid, and lutein ester content and antioxidant activity of 11 cultivars of Chinese marigold. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:8478–8484. doi: 10.1021/jf071696j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Foo LY. Antioxidant and radical scavenging activities of polyphenols from apple pomace. Food Chem. 2000;68:81–85. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(99)00167-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luthria DL. Influence of experimental conditions on the extraction of phenolic compounds from parsley (Petroselinum crispum) flakes using a pressurized liquid extractor. Food Chem. 2008;107:745–752. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.08.074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DJ, Hawthorne SB. Method for determining the solubility of hydrophobic organics in subcritical water. Anal Chem. 1998;70:1618–1621. doi: 10.1021/ac971161x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parejo I, Bastida J, Viladomat F, Codina C. Acylated quercetagetin glycosides with antioxidant activity from Tagetes maxima. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:2356–2362. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini N, Visioli F, Buratti S, Brighenti F. Direct analysis of total antioxidant activity of olive oil and studies on the influence of heating. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:2532–2538. doi: 10.1021/jf001418j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phattarakorn R, Nuchanart R, Jutamaad S, Motonobu G, Artiwan S. Subcritical water extraction of polyphenolic compounds from Terminalia chebula Retz. fruits. Sep Purif Technol. 2008;66:51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Phongkanpai V, Benjakul S, Tanaka M. Effect of pH on antioxidative activity and other characteristics of caramelization products. J Food Biochem. 2006;30:174–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2006.00053.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pongnaravane B, Goto M, Sasaki M, Anekpankul T, Pavasant P, Shotipruk A. Extraction of anthraquinones from roots of Morinda citrifolia by pressurized hot water: antioxidant activity of extracts. J Supercrit Fluid. 2006;37:390–396. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2005.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan MF, Kroh LW, Mörsel JT. Radical scavenging activity of black Cumin (Nigella sativa L), Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L), and Niger (Guizotia abyssinica Cass.) crude seed oils and oil fractions. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:6961–6969. doi: 10.1021/jf0346713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos L, Kristenson EM, Brinkman UAT. Current use of pressurised liquid extraction and subcritical water extraction in environmental analysis. J Chromatogr A. 2002;975:3–29. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(02)01336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Meizoso I, Marin FR, Herrero M, Seňorans FJ, Reglero G, Cifuentes A, Ibáňez E. Subcritical water extraction of nutraceuticals with antioxidant activity from oregano: chemical and functional characterization. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006;41:1560–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki M, Fang Z, Fukushima Y, Adschiri T, Arai K. Dissolution and hydrolysis of cellulose in subcritical and supercritical water. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2000;39:2883–2890. doi: 10.1021/ie990690j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saura-Calixto F. Antioxidant dietary fiber product: a new concept and a potential food ingredient. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:4303–4306. doi: 10.1021/jf9803841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sereewatthanawut I, Prapintip S, Watchiraruji K, Goto M, Sasaki M, Shotipruk A. Extraction of protein and amino acids from deoiled rice bran by subcritical water hydrolysis. Bioresource Technol. 2008;99:555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shotipruk A, Kiatsongserm J, Pavasant P, Goto M, Sasaki M. Pressurized hot water extraction of anthraquinones from the roots of Morinda citrifolia. Biotechnol Prog. 2004;20:1872–1875. doi: 10.1021/bp049779x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddhuraju P, Becker K. Antioxidant properties of various solvent extracts of total phenolic constituents from three different agroclimatic origins of drumstick tree (Moringa oleifera Lam.) leaves. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:2144–2155. doi: 10.1021/jf020444+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva EM, Rogez H, Larondelle Y. Optimization of extraction of phenolics from Inga edulis leaves using response surface methodology. Sep Purif Technol. 2007;55:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2007.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spigno G, Tramelli L, De Faveri DM. Effects of extraction time, temperature and solvent on concentration and antioxidant activity of grape marc phenolics. J Food Eng. 2007;81:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2006.10.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan P, Kashyap S, Sharma S. Tagetes: a multipurpose plant. Bioresource Technol. 1997;62:29–35. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(97)00101-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vatai T, Skerget M, Knez Z. Extraction of phenolic compounds from elder berry and different grape marc varieties using organic solvents and/or supercritical carbon dioxide. J Food Eng. 2009;90:246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2008.06.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wakita Y, Harada O, Kuwata M, Fujimura T, Yamada T, Suzuki M, Tsuji K. Preparation of subcritical water-treated okara and its effect on blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Food Sci Technol Res. 2004;10:164–167. doi: 10.3136/fstr.10.164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Gao Y, Liu X, Zhao J. Effects of supercritical carbon dioxide on volatiles formation from Maillard reaction between ribose and cysteine. J Sci Food Agr. 2008;88:328–335. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Belghazi M, Lagadec A, Miller DJ, Hawthorne SB. Elution of organic solutes from different polarity sorbents using subcritical water. J Chromatogr A. 1998;810:149–159. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(98)00222-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 170 kb)