Abstract

After central nervous system (CNS) injury, inhibitory factors in the lesion scar and a poor axon growth potential prevent axon regeneration. Microtubule stabilization reduces scarring and promotes axon growth. However, the cellular mechanisms of this dual effect remain unclear. Here, delayed systemic administration of a blood-brain barrier permeable microtubule stabilizing drug, epothilone B, decreased scarring after rodent spinal cord injury (SCI) by abrogating polarization and directed migration of scar-forming fibroblasts. Conversely, epothilone B reactivated neuronal polarization by inducing concerted microtubule polymerization into the axon tip, which propelled axon growth through an inhibitory environment. Together, these drug elicited effects promoted axon regeneration and improved motor function after SCI. With recent clinical approval, epothilones hold promise for clinical use after CNS injury.

An ideal treatment to induce axon regeneration in the injured central nervous system (CNS) will have at least three features. It should reduce scarring (1) and growth inhibitory factors at the lesion site (2-4), reactivate the axon growth potential (5) and be administrable as a medication after injury. Recently, a number of combinatorial approaches have led to axon regeneration (6, 7). These approaches, however, involve multiple drugs, enzymes and interventions rendering a clinical translation difficult. Moderate microtubule stabilization by the anti-cancer drug Taxol promotes axon regeneration by reducing fibrotic scarring and increasing axon growth (8, 9). However, it remains elusive how microtubule stabilization induces such divergent effects. Moreover, Taxol is infeasible for clinical CNS intervention, because it does not cross the blood-brain barrier (10).

We aimed to target microtubule stabilization in the injured CNS in a clinically feasible way and to decipher its distinct cellular actions. Therefore, we used epothilones, a class of FDA approved blood-brain-barrier permeable microtubule stabilizing drugs (11, 12). Mass spectrometry confirmed that after intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection in adult rats, epothilone B was rapidly absorbed into the CNS and remained at comparable levels for at least 6 days (Fig. 1A). Rats i.p. injected with 0.75 mg epothilone B per kg body weight at day 1 and 15 post-injury showed increased levels of detyrosinated and acetylated tubulin in lesion site extracts 4 weeks after thoracic spinal cord dorsal hemisection (Fig. 1B) indicating increased microtubule stability (13). The dosage used was well tolerated presenting no obvious adverse side effects, such as reduced animal weight or decreased white blood cell counts (fig. S1, A and B).

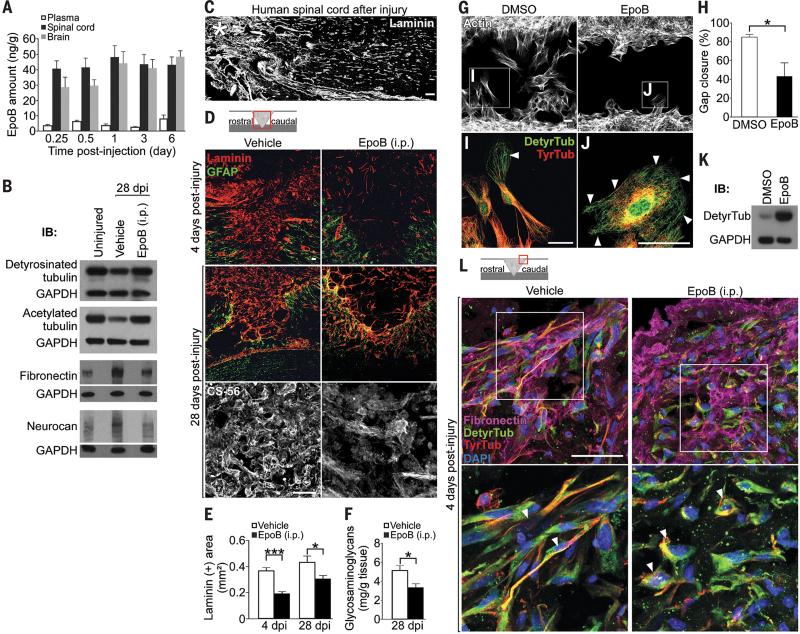

Fig. 1. Epothilone B increases microtubule stabilization, reduces fibrotic scar tissue and CSPG deposition after SCI by inhibiting meningeal fibroblast migration.

(A) Mass spectrometric analysis of CNS tissue and blood plasma after a single epothilone B intraperitoneal injection, n = 4 animals per time-point. (B) Western blots (WB) of indicated proteins in pooled spinal cord (lesion) extracts, n = 3 animals per group. (C) Human spinal cord 42 years after injury (asterisk), laminin immunolabeling. (D) Immunolabeling for laminin, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) or chondroitin sulfates (CS-56) after rat spinal cord hemisection. (E) Laminin-immunopositive (+) area at the lesion site, n = 7 to 8 animals per group. (F) Glycosaminoglycan amounts in spinal cord lesion extracts, n = 8 animals per group. (G) Cultured meningeal fibroblasts migrating into a cell free area in wound healing assays. (H) Percentage of the area shown in (G) occupied with cells after 48 hours of migration, n = 3 experiments. (I and J) High magnification of the boxed areas in (G) showing tyrosinated (TyrTub) and detyrosinated tubulin (DetyrTub, white arrowheads). (K) Western blots of detyrosinated tubulin and GAPDH in dissociated meningeal fibroblasts 48 hours after indicated treatment. (L) Immunolabeling of fibronectin, detyrosinated and tyrosinated in the meninges at a rat spinal cord injury site. Bottom panel, high magnification of meningeal fibroblasts (arrowheads) in top panel.

dpi, days post-injury. Schemes shown in (D) and (L) indicate lesion and displayed region (red box). Scale bars, 50 μm. Values are plotted as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Fibrotic scar tissue rich in fibronectin and laminin forms at the lesion site after SCI in rodents (8) and was also found in human post-mortem tissue from spinal cord injured patients (Fig. 1C; table S1). This scar tissue poses a key impediment to regenerating axons, because it contains axon growth inhibitory factors, including chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) (1, 8). Adult rats systemically treated with epothilone B, starting 1 day after spinal cord dorsal hemisection, showed a significant reduction of fibronectin (Fig. 1B) and of laminin-positive fibrotic scar tissue even 4 weeks after injury (Fig. 1D and E). We found a comparable decrease of fibrotic scarring when epothilone B was locally delivered to the injury site via an intrathecal catheter (fig. S2, A and B) (8). Importantly, reduction of fibrotic scar tissue by systemic epothilone B administration was associated with a decrease of CSPG deposition at the injury site, including neurocan and NG2 (14), as assessed by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1D and fig. S3), biochemical analysis (Fig. 1F) and western blotting (Fig. 1B). Astrogliosis (fig. S1C) and lesion area (fig. S1D) were similar between treated and control animals indicating that the neuroprotective glial sealing of the injury site (15) was not affected by the treatment.

The scar reducing effect of epothilone B resulted neither from decreased cell proliferation nor from increased apoptosis (fig. S4) but from a migratory defect of scar-forming meningeal fibroblasts (16). In wound healing assays, epothilone B inhibited migration of meningeal fibroblasts (Fig. 1, G and H and movies, S1 and S2) by drastically changing their microtubular network. Control cells polarized by forming a leading edge enriched in stable detyrosinated microtubules and a trailing edge containing dynamic, tyrosinated microtubules (Fig. 1I), both hallmarks of directed cell migration (17). In contrast, epothilone B treated fibroblasts were round and nonpolar (Fig. 1J) with elevated levels of detyrosinated microtubules (Fig. 1K) evenly distributed throughout the cell (Fig. 1J). Similarly, systemic administration of epothilone B after dorsal hemisection prevented the polarization of meningeal fibroblasts at the lesion site into a bipolar, migratory shape (Fig. 1L), which reduced scar formation (Fig. 1D and E).

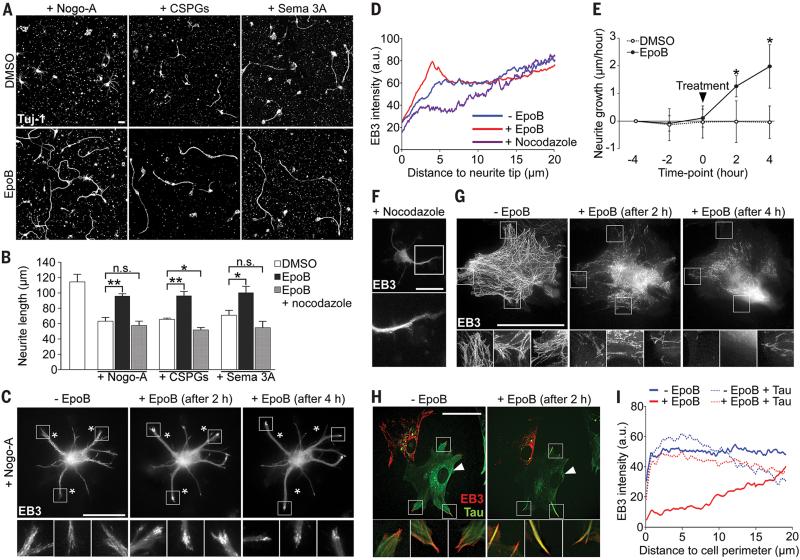

Interestingly, in co-cultures of meningeal fibroblasts and postnatal cortical neurons epothilone B perturbed fibroblast polarization while enhancing axon growth (fig. S5). Moreover, epothilone B restored axon growth when these neurons were confronted with the inhibitory molecules Nogo-A, CSPGs and Semaphorin3A, abundant at the spinal cord lesion site (Fig. 2, A and B) (2-4, 18). The underlying mechanism of enhanced axonal growth was revealed by video microscopy of neurons expressing fluorescently-tagged microtubule plus-end binding protein 3 (EB3-mCherry), a protein that specifically labels polymerizing microtubules (19). Epothilone B induced a rapid and concerted microtubule polymerization into the neurite tips (Fig. 2, C and D and movie S3), which caused axon elongation despite inhibitory Nogo-A (Fig. 2E and movie S3). Consistent with this effect, low doses of the microtubule destabilizing drug nocodazole, which abolished microtubule protrusion in neurites (Fig. 2, D and F), abrogated the growth promoting effect of epothilone B (Fig. 2B). Epothilone B also promoted axon growth of human cortical neurons under growth permissive as well as non-permissive conditions (fig. S6). In meningeal fibroblasts however, epothilone B prevented microtubule polymerization towards the cell edges (Fig. 2G) contrasting with the microtubule dynamics found in neurons. Thus, on the one hand, epothilone B promotes microtubule protrusion and axon elongation in neurons by exploiting the mechanism that controls axon growth during neuronal polarization (20). On the other hand, in scar-forming fibroblasts the drug dampens microtubule dynamics in the cell periphery, critical for structural polarization and directed cell migration (21). This dichotomy was attributed to the neuron-specific microtubule associated protein tau (fig. S7), which regulates microtubule dynamics and bundling as well as binding of microtubule stabilizing agents to tubulin (22-24). In fibroblasts, ectopically expressing tau, epothilone B induced an accumulation of bundled polymerizing microtubules that protruded into the cell edge (Fig. 2, H and I), hence mimicking the effect observed in neurons.

Fig 2. Epothilone B promotes microtubule protrusion and axon elongation in neurons while dampening microtubule dynamics in scar-forming fibroblasts.

(A) Beta-3 tubulin (Tuj-1) immunolabeling of neurons growing on inhibitory substrates (CSPGs, chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans; Sema 3A, Semaphorin 3A). (B) Neurite length of cortical neurons after 48 hours with (+) or without (-) indicated treatments, n = 3 to 4 experiments. (C) EB3-mCherry localization in a neuron cultured with Nogo-A, before and after epothilone B treatment. Bottom panels, high magnification of boxed areas in top panels. Asterisks, stable landmarks across time-points. (D) EB3-mCherry fluorescence intensity in neurites under indicated conditions, n = 9 to 16 neurons. (E) Neurite growth rates on Nogo-A before and after indicated treatment, n = 12 to 15 neurons. Black arrowhead, time of treatment. (F) EB3-mCherry localization in neurons treated with nocodazole. Bottom picture, high magnification of boxed area in top picture. (G and H) EB3- mCherry localization in cultured meningeal fibroblasts before and after epothilone B treatment. (G) Control cell, (H) control and tau-expressing (arrowhead) cells. Bottom panels, high magnification of boxed areas in top panels. (I) EB3-mCherry fluorescence intensity in fibroblast periphery under indicated conditions, n = 20 cells/condition.

Scale bars, 25 μm. Values are plotted as means (+ SEM in (B) and (E)). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. n.s., not significant.

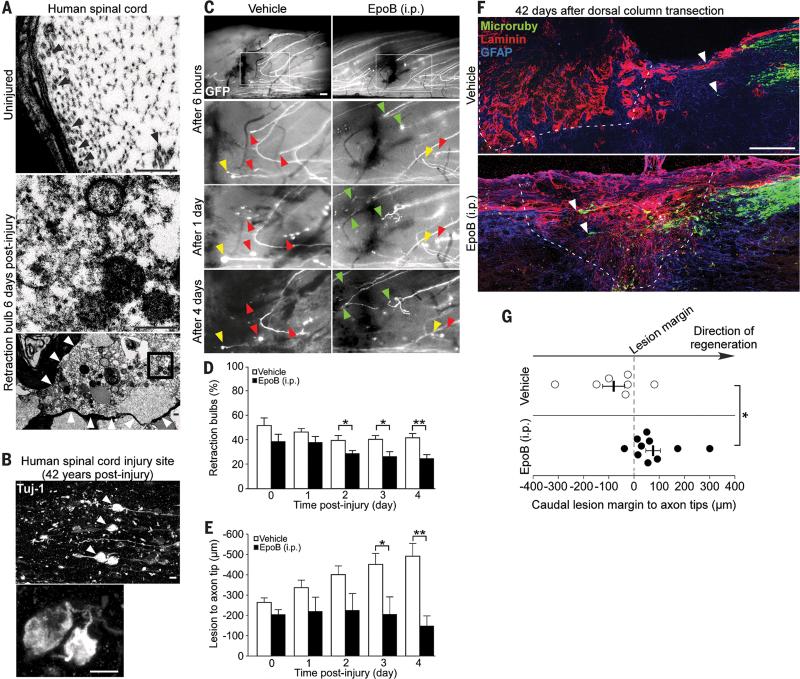

Injured axons in the rodent CNS form dystrophic retraction bulbs instead of regenerative growth cones, a consequence of microtubule depolymerization and disorganization (25, 26). Similarly, damaged axons after human SCI formed microtubule-depleted retraction bulbs (Fig. 3A), which remained at the injury site for decades (Fig. 3B and table S2). As epothilone B induced microtubule polymerization and axon growth in cultured neurons, we assessed its ability to promote axon regeneration after rodent SCI. In vivo imaging of adult transgenic mice, expressing GFP in spinal cord dorsal column axons (26, 27), revealed that transected axons of epothilone B injected animals exhibited significantly fewer retraction bulbs (Fig. 3, C and D), reduced axonal dieback and increased regenerative growth (Fig. 3, C and E). Moreover, dorsal column tracing revealed axon regeneration 6 weeks after complete dorsal column transection in adult mice systemically and post-injury treated with epothilone B whereas injured axons of control animals stalled at the caudal lesion margin (Fig. 3, F and G and movie S4).

Fig. 3. Epothilone B reduces dystrophy and promotes regeneration of injured spinal cord axons.

(A) Electron microscope images of human spinal cord after injury. Top panel, undamaged axon containing microtubules (black arrowheads). Bottom panel, retraction bulb without microtubules (boxed area as high magnification in middle panel). Scale bars, 500 nm. (B) Beta-3 tubulin immunolabeling of retraction bulbs in chronic human SCI. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Lesioned GFP-positive spinal cord axons forming retraction bulbs (yellow arrowheads), dying back (red arrowheads) or regenerating (green arrowheads) over time. Boxed area in top panel outlines the displayed region of the panels below. Scale bars, 100 μm. (D and E) Percentage of injured axons forming retraction bulbs (D) and distance of the lesioned, proximal axon tip to the injury site (E), n = 8 animals per group. (F) Mouse spinal cord after injury, Microruby-traced dorsal column axons (white arrowheads), laminin and GFAP immunolabeling (dashed line, lesion border). Scale bar, 100 μm. (G) Average distance between the caudal lesion margin and the axonal tips in each animal, n = 7-10 animals per group. Values are plotted as means + SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

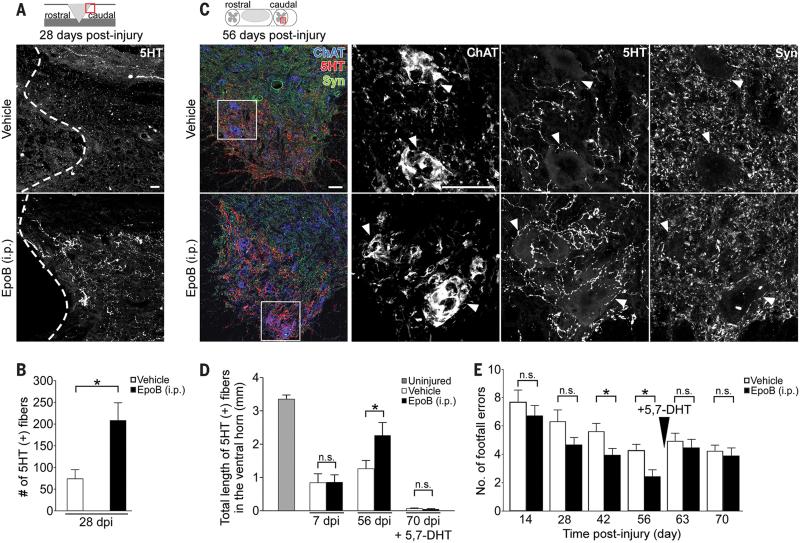

We then tested whether the treatment also promotes axon regrowth of descending axons important for locomotion. Indeed, 4 weeks after dorsal hemisection in adult rats systemic post-injury injections of epothilone B induced a 3-fold increase of serotonergic fibers caudal to the injury site (Fig. 4, A and B). Increased serotonergic innervation strongly correlates with recovery of motor function after SCI (28-30). Therefore, we asked whether the treatment improves walking of adult rats that underwent a moderate, mid-thoracic spinal cord contusion, a clinically relevant SCI model (31). Animals treated with epothilone B at 1 and 15 days post-injury showed a substantial reduction of fibrotic scar tissue (fig. S8, A and B) while serotonergic axon regrowth in the caudal spinal cord was enhanced (Fig. 4, C and D). Automated footprint analysis revealed that epothilone B treatment increased stride length and gait regularity, and reduced external rotation of the hind paws (fig. S9, A to C) indicating improved walking balance and coordination. Accordingly, epothilone B treated animals showed a 50% reduction of foot misplacements on the horizontal ladder compared to injured controls (Fig. 4E and movies, S4 and S5). Ablation of serotonergic innervation with 5,7-Dihydroxytryptamine (Fig. 4D) (28) abrogated the functional improvements of epothilone B treated animals (Fig. 4E and movies, S6 and S7). Thus, epothilone B treatment promotes recovery of walking functions after spinal cord contusion injury, at least in part by restoring serotonergic innervation.

Fig. 4. Epothilone B promotes regeneration of serotonergic spinal axons and enhances functional recovery of walking after spinal cord contusion.

(A) Serotonin (5HT) immunolabeling (dashed line, lesion border) and (B) number of 5HT-labeled (+) fibers caudal to a rat spinal dorsal hemisection, n = 7-8 animals per group. (C) Coronal sections of the rat lumbar spinal cord after contusion injury. Left panel, coimmunostaining of 5HT, synaptophysin (Syn) and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT). Right panels, high magnification images of each marker in the boxed area (left panel) visualizing serotonergic innervation of motor neurons (arrowheads). (D) Total length of 5HT-immunopositive fibers in the spinal cord ventral horn after indicated treatments and time-points (5,7-DHT = 5,7-Dihydroxytryptamine), n = 4 (uninjured), 6 (7dpi) and 11-12 animals (56 and 70 dpi) per group, respectively. (E) Number of footfalls on the horizontal ladder, n = 10-11 animals per group.

dpi, days post-injury. Schemes in (A) and (C) indicate lesion and displayed region (red box).

Scale bars, 50 μm. Values are plotted as means + SEM. *P < 0.05. n.s., not significant.

Microtubules are fundamental for numerous cellular processes, including cell migration, signal integration, proliferation and axon growth (8, 17, 20, 32). The finding that the stabilization of microtubules inhibits cell division established the usage of systemic microtubule stabilizing agents as a therapeutic standard for the treatment of cancer (33). Here, our work shows that systemic administration of the microtubule stabilizing agent epothilone B promotes functional recovery after SCI. Our approach differs from other experimental regenerative paradigms (1-7) by pharmacologically focusing on a single molecular target, the microtubules, yet overcoming multiple pathological obstacles at once. This is possible due to distinct effects of pharmacological microtubule stabilization on microtubule dynamics and, thereby, polarization of neurons and meningeal fibroblasts. This dual effect and the efficacy after systemic and post-injury administration, give epothilones a promising translational perspective for treatment of the injured CNS.

Supplementary Material

One sentence summary.

Systemic administration of epothilone B promotes functional axon regeneration after spinal cord injury by controlling the polarization of neurons and meningeal fibroblasts.

Acknowledgements

Material and methods and other supporting materials are available in the online version of the paper.

We thank L. Meyn, K. Weisheit, D. Fleischer and N. Thielen for technical assistance and animal care and Dr. C. Hill for teaching the spinal cord contusion injury model. We also thank C. Laskowski, C.H. Coles, A. Kania, W. Jackson and G. Tavosanis for critically reading and discussing the manuscript. We are grateful for the support from the Human Spinal Cord Tissue Bank and the electron microscopy core at the Miami Project as well as Professor B. Kakulas, University of Western Australia and Royal Perth providing anonymized post mortem sections following human spinal cord injury. This work was supported by NIH, IRP, WfL and DFG.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References and Notes

- 1.Klapka N, et al. Suppression of fibrous scarring in spinal cord injury of rat promotes long-distance regeneration of corticospinal tract axons, rescue of primary motoneurons in somatosensory cortex and significant functional recovery. Eur J Neurosci. 2005 Dec;22:3047. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GrandPre T, Li S, Strittmatter SM. Nogo-66 receptor antagonist peptide promotes axonal regeneration. Nature. 2002;417:547. doi: 10.1038/417547a. 05/30/print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradbury EJ, et al. Chondroitinase ABC promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature. 2002 Apr 11;416:636. doi: 10.1038/416636a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schnell L, Schwab ME. Axonal regeneration in the rat spinal cord produced by an antibody against myelin-associated neurite growth inhibitors. Nature. 1990;343:269. doi: 10.1038/343269a0. 01/18/print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu K, et al. PTEN deletion enhances the regenerative ability of adult corticospinal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1075. doi: 10.1038/nn.2603. 09//print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alilain WJ, Horn KP, Hu H, Dick TE, Silver J. Functional regeneration of respiratory pathways after spinal cord injury. Nature. 2011;475:196. doi: 10.1038/nature10199. 07/14/print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu P, et al. Long-Distance Growth and Connectivity of Neural Stem Cells after Severe Spinal Cord Injury. Cell. 2012;150:1264. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hellal F, et al. Microtubule stabilization reduces scarring and causes axon regeneration after spinal cord injury. Science. 2011 Feb 18;331:928. doi: 10.1126/science.1201148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sengottuvel V, Fischer D. Facilitating axon regeneration in the injured CNS by microtubules stabilization. Communicative & integrative biology. 2011 Jul;4:391. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.4.15552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fellner S, et al. Transport of paclitaxel (Taxol) across the blood-brain barrier in vitro and in vivo. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2002 Nov;110:1309. doi: 10.1172/JCI15451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lechleider RJ, et al. Ixabepilone in combination with capecitabine and as monotherapy for treatment of advanced breast cancer refractory to previous chemotherapies. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2008 Jul 15;14:4378. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballatore C, et al. Microtubule stabilizing agents as potential treatment for Alzheimer's disease and related neurodegenerative tauopathies. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2012 Nov 8;55:8979. doi: 10.1021/jm301079z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janke C, Bulinski JC. Post-translational regulation of the microtubule cytoskeleton: mechanisms and functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011 Dec;12:773. doi: 10.1038/nrm3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cregg JM, et al. Functional regeneration beyond the glial scar. Experimental Neurology. 2014;253:197. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.12.024. 3// [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faulkner JR, et al. Reactive astrocytes protect tissue and preserve function after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2004 Mar 3;24:2143. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3547-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carbonell AL, Boya J. Ultrastructural study on meningeal regeneration and meningo-glial relationships after cerebral stab wound in the adult rat. Brain Res. 1988 Jan 26;439:337. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91491-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gundersen GG, Bulinski JC. Selective stabilization of microtubules oriented toward the direction of cell migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Aug;85:5946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasterkamp RJ, et al. Expression of the gene encoding the chemorepellent semaphorin III is induced in the fibroblast component of neural scar tissue formed following injuries of adult but not neonatal CNS. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999 Feb;13:143. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flynn KC, et al. ADF/cofilin-mediated actin retrograde flow directs neurite formation in the developing brain. Neuron. 2012 Dec 20;76:1091. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Witte H, Neukirchen D, Bradke F. Microtubule stabilization specifies initial neuronal polarization. J Cell Biol. 2008 Feb 11;180:619. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Etienne-Manneville S. Microtubules in cell migration. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2013;29:471. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosik KS, Crandall JE, Mufson EJ, Neve RL. Tau in situ hybridization in normal and Alzheimer brain: localization in the somatodendritic compartment. Ann Neurol. 1989 Sep;26:352. doi: 10.1002/ana.410260308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drubin DG, Kirschner MW. Tau protein function in living cells. J Cell Biol. 1986 Dec;103:2739. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rouzier R, et al. Microtubule-associated protein tau: a marker of paclitaxel sensitivity in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Jun 7;102:8315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408974102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradke F, Fawcett JW, Spira ME. Assembly of a new growth cone after axotomy: the precursor to axon regeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012 Mar;13:183. doi: 10.1038/nrn3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erturk A, Hellal F, Enes J, Bradke F. Disorganized microtubules underlie the formation of retraction bulbs and the failure of axonal regeneration. J Neurosci. 2007 Aug 22;27:9169. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0612-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laskowski CJ, Bradke F. In vivo imaging: A dynamic imaging approach to study spinal cord regeneration. Experimental Neurology. 2013;242:11. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.07.007. 4// [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaneko S, et al. A selective Sema3A inhibitor enhances regenerative responses and functional recovery of the injured spinal cord. Nat Med. 2006 Dec;12:1380. doi: 10.1038/nm1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JE, Liu BP, Park JH, Strittmatter SM. Nogo-66 receptor prevents raphespinal and rubrospinal axon regeneration and limits functional recovery from spinal cord injury. Neuron. 2004 Oct 28;44:439. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sławińska U, et al. Grafting of fetal brainstem 5-HT neurons into the sublesional spinal cord of paraplegic rats restores coordinated hindlimb locomotion. Experimental Neurology. 2013;247:572. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.02.008. 9// [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wrathall JR, Pettegrew RK, Harvey F. Spinal cord contusion in the rat: production of graded, reproducible, injury groups. Exp Neurol. 1985 Apr;88:108. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(85)90117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glotzer M. The 3Ms of central spindle assembly: microtubules, motors and MAPs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:9. doi: 10.1038/nrm2609. 01//print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dumontet C, Jordan MA. Microtubule-binding agents: a dynamic field of cancer therapeutics. Nature reviews. Drug discovery. 2010;9:790. doi: 10.1038/nrd3253. 10//print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheff SW, Rabchevsky AG, Fugaccia I, Main JA, Lumpp JE., Jr. Experimental modeling of spinal cord injury: characterization of a force-defined injury device. J Neurotrauma. 2003 Feb;20:179. doi: 10.1089/08977150360547099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carta M, Carlsson T, Kirik D, Bjorklund A. Dopamine released from 5-HT terminals is the cause of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in parkinsonian rats. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2007 Jul;130:1819. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bates M, Puzis R, Bunge M. In: Animal Models of Movement Disorders. Lane EL, Dunnett SB, editors. Vol. 62. Humana Press; 2011. pp. 381–399. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buss A, et al. Growth-modulating molecules are associated with invading Schwann cells and not astrocytes in human traumatic spinal cord injury. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2007 Apr;130:940. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fleming JC, et al. The cellular inflammatory response in human spinal cords after injury. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2006 Dec;129:3249. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amit M, et al. Clonally derived human embryonic stem cell lines maintain pluripotency and proliferative potential for prolonged periods of culture. Developmental biology. 2000 Nov 15;227:271. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi Y, Kirwan P, Smith J, Robinson HP, Livesey FJ. Human cerebral cortex development from pluripotent stem cells to functional excitatory synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2012 Mar;15:477. doi: 10.1038/nn.3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.