Abstract

Pancreatic metastases are rare, ranging from 2% to 5% of pancreatic malignancies. Differentiating a primary pancreatic malignancy from a metastasis can be difficult due to similarities on imaging findings, but is crucial to ensure proper treatment. Although transabdominal ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging provide useful images, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with fine needle aspiration (FNA) is often needed to provide a cytologic diagnosis. Here, we present a unique case of malignant melanoma with pancreatic metastases. It is important for clinicians to recognize the possibility of melanoma metastasizing to the pancreas and the role of EUS with FNA in providing cytological confirmation.

Keywords: Endoscopic ultrasound, endoscopic ultrasound-fine needle aspiration, melanoma, metastatic melanoma, pancreatic metastasis

INTRODUCTION

Isolated pancreatic metastases are rare, accounting for approximately 2% of pancreatic tumors.[1,2] The most common primary sites are renal, lung, breast, and colon cancer, with soft tissue sarcoma and melanoma observed less commonly.[2,3] Differentiating metastases from a primary pancreatic malignancy, such as a ductal or neuroendocrine tumor, can be challenging. With endoscopic ultrasound, neuroendocrine tumors appear as well-defined masses in the pancreas,[4] and can resemble pancreatic metastases. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with fine-needle aspiration (FNA) plays an important role in providing cytological confirmation for diagnosis.

CASE REPORT

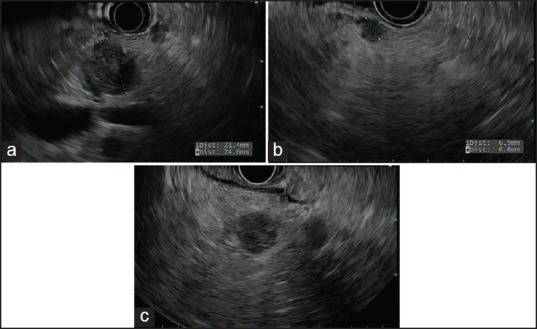

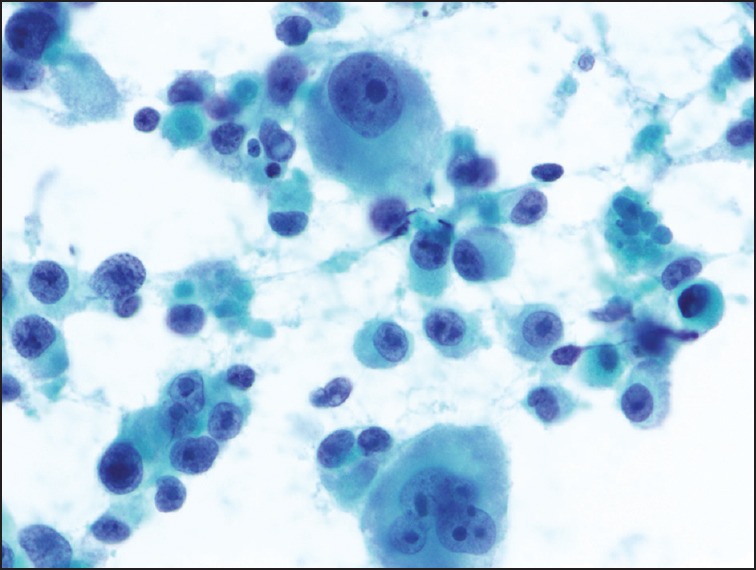

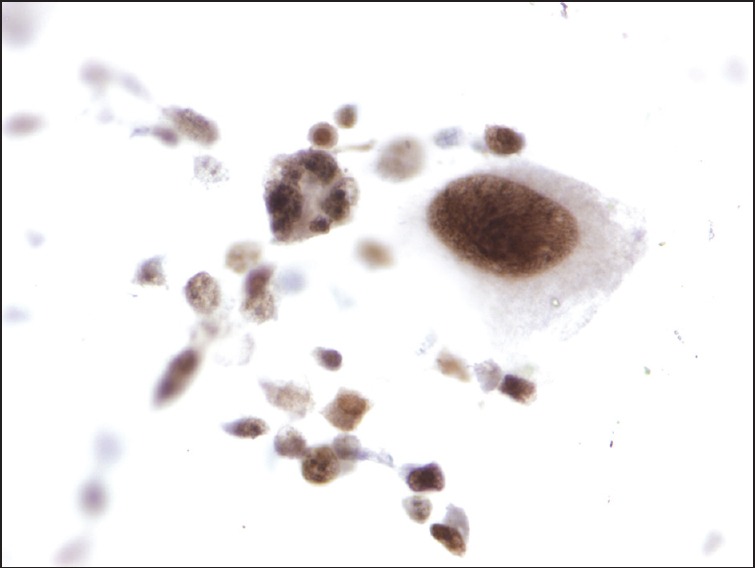

A 75-year-old man with a history of metastatic melanoma presented for routine surveillance studies. His history was significant for the diagnosis of malignant melanoma of the right chest with lymphatic spread to the right axilla 1 year prior. He had right mastectomy and sentinel node biopsy at that time, and there was no visceral organ involvement. At the time of our evaluation, he was asymptomatic, and there were no suspicious skin lesions or palpable lymphadenopathy. Vital signs were normal. Complete blood cell count, metabolic panel, and coagulation studies were within normal limits. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (CT) showed increased metabolic activity in the proximal pancreas, with standardized uptake value of 10.36. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen revealed a 1.7 cm focal pancreatic mass and a large left upper retroperitoneal lymph node. Before the patient was referred to us for EUS and possible FNA, there was concern from the patient's oncologist about a new pancreatic neoplasm. It was discussed that management would be dramatically different if this was a new primary pancreatic neoplasm versus a metastatic lesion to the pancreas from his melanoma that would be occurring approximately a year after the initial resection of the index melanoma lesion. EUS revealed several hypoechoic, rounded, well-defined masses. The dominant lesion was a 24.6 mm × 21.4 mm mass in the body of the pancreas [Figure 1a]. There was also a 6.9 mm × 6.6 mm nodule in the body [Figure 1b] and 14.1 mm × 11.7 mm and 10.6 mm × 7.2 mm masses [Figure 1c] in the pancreatic head. EUS-guided FNA of the pancreatic head [Figure 2] lesions was performed with a 25-gauge needle. Aspirate smears showed a dispersed population of pleomorphic malignant cells with large hyperchromatic nuclei and prominent nucleoli [Figure 3], consistent with a history of melanoma. The tumor cells were immunoreactive for Sox-10 [Figure 4], confirming the diagnosis. He subsequently underwent stereotactic gamma knife radiosurgery for a solitary brain metastasis and will be receiving immunotherapy to treat his pancreatic metastases.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic ultrasound images revealing multiple well-demarcated, hypoechoic pancreatic lesions ((a) 24.6 mm × 21.4 mm mass in the body of the pancreas, (b) 6.9 mm × 6.6 mm nodule in the body, and (c) 14.1 mm × 11.7 mm and 10.6 mm × 7.2 mm masses in the pancreatic head)

Figure 2.

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of pancreatic head lesion

Figure 3.

Aspirate smear showing a dispersed population of pleomorphic tumor cells with prominent nucleoli and occasional multinucleation, consistent with metastatic melanoma (Papanicolaou stain)

Figure 4.

Aspirate tumor cells reactive for Sox-10, supporting a diagnosis of metastatic melanoma (immunohistochemical stain)

DISCUSSION

Pancreatic tumors are commonly primary in origin (90% ductal and 5% neuroendocrine).[5] Isolated pancreatic metastases are rare, accounting for approximately 2% of pancreatic tumors,[1,2] with pancreatic metastases from melanoma being reported in 50% of cases of disseminated disease.[1] The most common primary sites are renal, lung, breast, and colon cancer, with soft tissue sarcoma and melanoma observed less commonly.[2,3] While patients with pancreatic metastases can present with jaundice, abdominal pain, and weight loss,[6]50-83% have no organ-specific complaints when metastases are incidentally discovered on imaging studies.[7]

Differentiating pancreatic metastases from a primary pancreatic malignancy can be challenging. Accurate diagnosis is essential for optimal treatment and can influence whether surgical or non-operative management is pursued.[8] Useful diagnostic tools include CT, MRI, and EUS with FNA biopsy,[6] but imaging alone cannot distinguish benign or primary pancreatic tumors from metastatic lesions.[8] In the case of our patient, EUS showed hypoechoic, rounded, and well-defined masses in the pancreas. From this imaging finding, we were unable to make a conclusive diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumor versus pancreatic metastases, thus prompting use of EUS-FNA to obtain histological confirmation.

Metastatic involvement of the pancreas may appear as a solitary lesion, which makes differentiation from a single primary tumor difficult.[6] CT imaging with evidence of a pancreatic mass with significant peripheral enhancement of the lesion and a low attenuation on the central area suggests metastasis,[1,6] but may not be accurate for distinguishing from a neuroendocrine tumor, which is seen as an enhancing or hypervascular lesion on early and late arterial phase images.[9] On MRI, neuroendocrine tumors generally appear hypointense on T1-weighted sequences and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, when compared with the liver parenchyma.[9] Similarly, pancreatic metastases appear hypointense on T1-weighted images and demonstrate heterogeneous or moderate hyperintense signal on T2-images.[6]

Compared with CT and MRI, EUS has the advantage of being able to detect small lesions (as small as 2-3 mm in diameter) within the pancreas and duodenal wall.[9] Studies have shown that EUS has a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 92% in the evaluation of solid pancreatic masses,[5] although malignancy can still be missed, especially in the setting of acute or chronic pancreatitis.[10] With endoscopic ultrasound, neuroendocrine tumors typically appear as homogenous, hypoechogenic, hypervascular solid lesions that have well-delimited borders.[4] Pancreatic metastases have many similar characteristics. In general, pancreatic metastases on EUS have regular margins and appear as homogenous structures that are hypoechoic compared to the surrounding pancreas.[3] EUS findings of primary pancreatic cancer and malignancy are similar with regards to consistency, echogenicity, location, and tumor size.[6,8] However, in a study of 24 patients with pancreatic metastases and 80 with primary pancreatic malignancy, pancreatic metastases were more likely to have well-defined tumor margins than primary pancreatic cancer (46% vs. 4%).[8] In previous case reports, DeWitt et al. and Minoguchi et al. demonstrated that pancreatic metastases from metastatic melanoma appear hypoechoic, heterogeneous, lobular, and round. In these cases, conclusive diagnosis was made with immunohistochemical staining.[11,12]

Our case and previous studies indicate that neuroendocrine tumors and pancreatic metastases may be indistinguishable based on initial imaging studies. In such cases, cytology with EUS-guided FNA can be instrumental in establishing a definitive diagnosis.

For EUS-guided FNA to be accurate in distinguishing pancreatic metastases from a primary carcinoma, effective sampling and immunocytochemistry are needed.[6,8] While there are no dedicated published studies on the overall efficacy of EUS FNA specifically for the diagnosis of pancreatic metastases from metastatic melanoma, Atiq et al. have reported a 91.3% diagnostic accuracy for pancreatic metastases, including one case of melanoma.[13] Sox-10 immunohistochemical staining has been shown to be useful in identifying melanoma metastases[14] and in our case, was used to establish a definitive cytologic diagnosis of malignant melanoma with pancreatic metastases.

Here, we present a unique case of pancreatic metastases from malignant melanoma that was conclusively proven with EUS-FNA. It is important for clinicians to consider a broad differential diagnosis when faced with inconclusive imaging studies of pancreatic tumors. In these cases, EUS with FNA may be useful in providing a definitive diagnosis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Portale TR, Di Benedetto V, Mosca F, et al. Isolated pancreatic metastasis from melanoma. Case report. G Chir. 2011;32:135–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goyal J, Lipson EJ, Rezaee N, et al. Surgical resection of malignant melanoma metastatic to the pancreas: Case series and review of literature. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:431–6. doi: 10.1007/s12029-011-9320-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fusaroli P, d’Ercole MC, De Giorgio R, et al. Contrast harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography in the characterization of pancreatic metastases (with video) Pancreas. 2014;43:584–7. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gornals J, Varas M, Catalá I, et al. Definitive diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors using fine-needle aspiration-puncture guided by endoscopic ultrasonography. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2011;103:123–8. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082011000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eloubeidi MA, Tamhane AR, Buxbaum JL. Unusual, metastatic, or neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas: A diagnosis with endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration and immunohistochemistry. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:99–105. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.93810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Triantopoulou C, Kolliakou E, Karoumpalis I, et al. Metastatic disease to the pancreas: An imaging challenge. Insights Imaging. 2012;3:165–72. doi: 10.1007/s13244-011-0144-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scatarige JC, Horton KM, Sheth S, et al. Pancreatic parenchymal metastases: Observations on helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:695–9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.3.1760695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeWitt J, Jowell P, Leblanc J, et al. EUS-guided FNA of pancreatic metastases: A multicenter experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:689–96. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung D, Schwartz L. Imaging of neuroendocrine tumors. Semin Oncol. 2013;40:109–19. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhutani MS, Gress FG, Giovannini M, et al. The No Endosonographic Detection of Tumor (NEST) Study: A case series of pancreatic cancers missed on endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 2004;36:385–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeWitt JM, Chappo J, Sherman S. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of melanoma metastatic to the pancreas: Report of two cases and review. Endoscopy. 2003;35:219–22. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minoguchi M, Yanagawa N, Ishikawa C, et al. Pancreatic metastasis of malignant melanoma diagnosed by EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2007;104:1082–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atiq M, Bhutani MS, Ross WA, et al. Role of endoscopic ultrasonography in evaluation of metastatic lesions to the pancreas: A tertiary cancer center experience. Pancreas. 2013;42:516–23. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31826c276d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jennings C, Kim J. Identification of nodal metastases in melanoma using sox-10. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:474–82. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182042893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]