Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Growing concern about rising costs and potential harms of medical care has stimulated interest in assessing physicians’ ability to minimize the provision of unnecessary care.

OBJECTIVE

To assess whether graduates of residency programs characterized by low-intensity practice patterns are more capable of managing patients’ care conservatively, when appropriate, and whether graduates of these programs are less capable of providing appropriately aggressive care.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

Cross-sectional comparison of 6639 first-time takers of the 2007 American Board of Internal Medicine certifying examination, aggregated by residency program (n = 357).

EXPOSURES

Intensity of practice, measured using the End-of-Life Visit Index, which is the mean number of physician visits within the last 6 months of life among Medicare beneficiaries 65 years and older in the residency program’s hospital referral region.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

The mean score by program on the Appropriately Conservative Management (ACM) (and Appropriately Aggressive Management [AAM]) subscales, comprising all American Board of Internal Medicine certifying examination questions for which the correct response represented the least (or most, respectively) aggressive management strategy. Mean scores on the remainder of the examination were used to stratify programs into 4 knowledge tiers. Data were analyzed by linear regression of ACM(or AAM) scores on the End-of-Life Visit Index, stratified by knowledge tier.

RESULTS

Within each knowledge tier, the lower the intensity of health care practice in the hospital referral region, the better residency program graduates scored on the ACM subscale (P < .001 for the linear trend in each tier). In knowledge tier 4 (poorest), for example, graduates of programs in the lowest-intensity regions had a mean ACM score in the 38th percentile compared with the 22nd percentile for programs in the highest-intensity regions; in tier 2, ACM scores ranged from the 75th to the 48th percentile in regions from lowest to highest intensity. Graduates of programs in low-intensity regions tended, more weakly, to score better on the AAM subscale (in 3 of 4 knowledge tiers).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Regardless of overall medical knowledge, internists trained at programs in hospital referral regions with lower-intensity medical practice are more likely to recognize when conservative management is appropriate. These internists remain capable of choosing an aggressive approach when indicated.

The inexorable growth of health care utilization and spending within the United States is no longer newsworthy. Although growth has recently slowed from a sustained average of 7% per year,1 the Congressional Budget Office still predicts a near doubling of Medicare and Medicaid spending in the next decade,2 placing an enormous financial burden on individuals, industry,3 and the US government.4 Although health care certainly offers important benefits, a growing body of evidence points to serious problems of overuse and harm. Higher regional spending is not associated with better patient outcomes, satisfaction, or quality of care,5,6 and high spending leads to more rapid growth in spending.7 Understanding the factors contributing to higher health care utilization use has therefore become an increasingly important national priority.

Although physician services represent a fraction of every dollar spent on US health care,4,8 physicians have long been understood to direct most health care decisions.9 Discretionary interventions by primary care physicians have proved to be a strong predictor of community-level health care spending.10 Although differences in physician practice patterns are now the focus of novel efforts to promote more rational use—most notably, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign11—the origins of such differences are poorly understood. One potential source of practice variation is physician training. Given that a residency training program’s subspecialty focus measurably influences residents’ performance,12 we wondered whether a program’s ambient practice style also teaches, inadvertently or not, a conservative or aggressive approach.

A conservative (ie, lower-intensity) practice style requires physicians to forego a wide array of costly medical interventions in favor of management strategies of lesser intensity, such as watchful waiting, a less-expensive intervention, or withdrawal of a therapy. Physicians’ ability to tolerate such an approach appears to vary.13,14 A comparable set of choices is posed to candidates throughout the ABIM certifying examination, which is taken by most internists upon completion of a 3-year residency program. On the examination, a conservative strategy may be the appropriate option (ie, the correct answer). We undertook to use such examination questions to test the hypothesis that physicians’ ability to practice conservatively is related to the residency training environment. Specifically, we evaluated whether graduates of programs characterized by a high-intensity practice environment perform more poorly on certifying examination questions that assess candidates’ ability to identify a conservative approach as the best management strategy. We also posed the analogous question regarding appropriately aggressive management ability.

Methods

Overview

Using the 2007 ABIM certifying examination, we developed an appropriately conservative management (ACM) subscale and a companion appropriately aggressive management (AAM) subscale by identifying all questions for which the correct answer was the most conservative or aggressive, respectively, option presented. We then evaluated the association between scores on these subscales, aggregated by residency training program, and the intensity of practice in the region of the training program’s primary hospital. The project was approved by the institutional review board at Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth College.

The Sample: Residency Programs and Candidates

We identified 401 internal medicine residency programs recognized by the ABIM and, to obtain information about the intensity of practice experienced by residents, determined the primary training hospital for each program using the websites of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the American Medical Association’s Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database (FREIDA), and the residency programs. We excluded programs based in hospitals for which utilization data are unavailable or do not contribute to geographic measures of health care utilization; these included 14 programs in Canada, 8 programs in Puerto Rico, 13 Veterans Affairs–or military hospital–based programs (not counting 1 in Puerto Rico),4programs based in Kaiser hospitals (providing minimal fee-for-service care), and 2 programs based in hospitals that closed during 2007. This process yielded 360 residency programs and 6689 candidates who took the ABIM certifying examination for the first time in 2007. An additional 3 programs were removed because of the exclusion of 3 candidates with invalidated examination scores and 47 candidates who had completed residency training 5 or more years before taking the examination, yielding a final sample of 6639 candidates from357 programs.

Measures

Intensity (Exposure)

We determined the intensity of practice experienced by residents in a given program by measuring per capita health care utilization in the area of the primary training hospital. The measure used, the End-of-Life Visit Index (EOL-VI), is based on the mean number of physician visits (inpatient and outpatient) for Medicare beneficiaries in the last 6 months of life. This measure, calculated for each of 306 US hospital referral regions (HRRs) for Medicare beneficiaries 65 years or older with chronic illness who died between 2003 and 2007, and adjusted for age, sex, race, and chronic condition,15 allows for measurement of health care utilization among a cohort of comparably ill patients, all with a life expectancy of exactly 6 months. We posited that this visit-based measure may reflect residents’ experience of practice intensity more accurately than a direct measure of spending.

Residency programs were assigned to HRRs (on the basis of the zip code of the primary training hospital), which were in turn characterized according to the intensity of practice (EOL-VI) in the HRR. The results are displayed according to the quintile of intensity, with each quintile containing an approximately equal number of residency programs. The median number of visits per capita (EOL-VI) ranged from 23.0 in the lowest-intensity quintile to 49.5 in the highest-intensity quintile (eTable in the Supplement).

In sensitivity analyses, we used 2 alternative intensity measures as the exposure: at the HRR level, we substituted mean per capita 2009 Medicare spending on beneficiaries aged 65 years or older adjusted for age, sex, race, and price. At the level of the primary training hospital, we used our primary exposure (EOL-VI) at the hospital level based on Medicare patients in a chronic illness cohort who had been hospitalized at least once.15

ACM and AAM Scores (Outcomes)

Identification of Questions for Coding

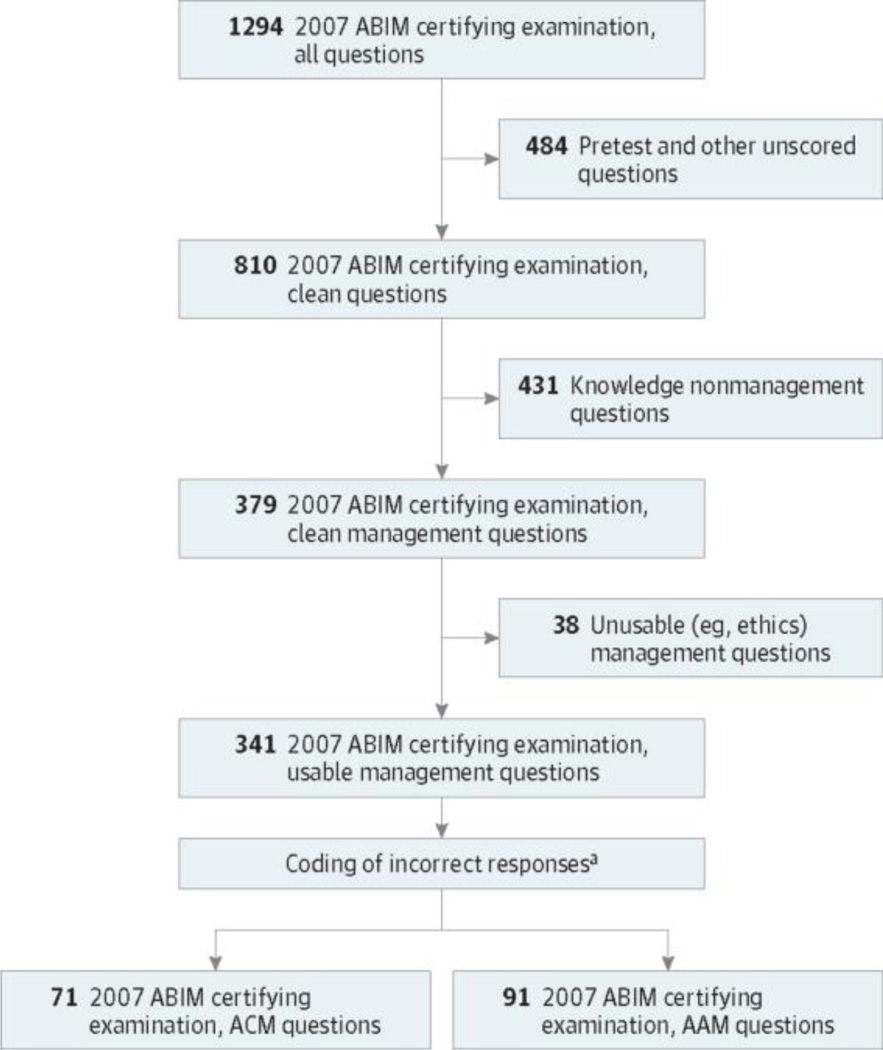

To identify questions for the ACM and AAM subscales (those that would allow us to measure whether newly trained internists are able to practice conservatively or aggressively, respectively, when clinically indicated) we implemented a standardized protocol (Figure 1). First, we excluded questions from the 2007 certifying examination that did not contribute to a candidate’s score (primarily pretest questions). Second, all management questions (those presenting a scenario and asking the candidate to identify the preferred management strategy from among 3–6 response options) were identified; the remaining knowledge questions (testing a candidate’s knowledge without posing a management decision, eg, questioning the most likely diagnosis) were excluded. The 379 resulting questions constituted the pool of unique management questions across the 5 forms of the 2007 ABIM certifying examination.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of the Identification and Coding of 2007 American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Certifying Examination Questions for Subscale Inclusion.

ACM indicates appropriate conservative management; AAM, appropriately aggressive management.

a Most usable management questions did not qualify for inclusion in the ACM or AAM subscale. Coding was performed by the investigators or by trained physician coders overseen by the investigators depending on the stage of the project.

Coding Procedure

For each management question, all incorrect response options were coded as representing a more aggressive, more conservative, or comparably intensive management strategy compared with the correct response. We used conservative and aggressive terminology based on the recommendation of an advisory group of researchers and other content experts from a variety of specialties convened expressly to inform the development and implementation of a clinically meaningful coding system for this project. Conservative management was defined as minimizing a patient’s exposure to medical care. An aggressive strategy was at the other end of a continuum, essentially maximizing a patient’s exposure to medical care.

Coding was accomplished in 2 phases. In phase I, we recruited and trained 9 ABIM-certified physician coders who worked in teams of 3. On each team, coders read and independently coded (as more aggressive, more conservative, or comparable) each incorrect response option from up to 100 management questions, in 10-question blocks. After each block, coders compared their assigned codes and attempted to reconcile any differences, supervised by an investigator/ moderator (including B.E.S. and R.S.L.). Response options were deemed irreconcilable after 5 minutes of discussion.

The temptation of coders to code incorrect response options based on perceived relative wrongness (and associated harm) was the single biggest obstacle to successful coding. This observation led us, after round 1 (of 5) of phase I coding, to clarify coding instructions, directing coders to judge relative aggressiveness solely as a function of resource use rather than perceived harm. To maximize comparability across coding sessions, 2 investigators (B.E.S. and E.S.H.) reviewed selected subsets of coded questions for consistency (particularly vis-à-vis consideration of perceived harm and groups of unique questions testing highly comparable management decisions).

In phase II of the coding process, which was necessary owing to late discovery of a set of management questions inadvertently omitted from those initially provided to the research team, 2 investigators (B.E.S. and E.S.H.) independently coded incorrect response options, reconciling differences by consensus conference.

Of the 379 management questions coded, 268 during phase I and 111 during phase II, 38 (30 from phase I and 8 from phase II) were excluded as unusable (eg, questions presenting the management of an ethics dilemma), yielding 341 usable management questions (Figure 1).

Subscale Development

For 71 of the 341 usable management questions, all incorrect response options were coded as more aggressive than the correct response. These 71 questions, composing the ACM subscale, collectively tested the examination taker’s ability to identify the most conservative management strategy as the preferred option, that is, as the correct answer.

We developed an AAM subscale to address the possibility that a training environment characterized by low-intensity practice would foster a conservative practice style even when an aggressive approach is indicated. This subscale, which included the 91 management questions with all incorrect response options coded as more conservative than the correct response, tested a candidate’s ability to identify the most aggressive management strategy as the best option. Examples of coded questions are presented in the Box.

Subscale Standardization

Because the 2007 ABIM certifying examination was administered using 5 forms, all scores were scaled using the Rasch model16,17 and standardized on a scale of 200 to 800 to ensure that the ACM and AAM scores were comparable across forms. We calculated the ACM and AAM scores for each residency program as the mean score for all graduates who took the examination for the first time in 2007, expressed as a percentile (relative to the mean scores of all other programs).

Knowledge Quartile (Stratifier)

Owing to concern about possible confounding because of high-performing residents clustering in regions of higher health care utilization (and independently scoring well on the examination and subscales, including ACM and AAM), we stratified programs into 4 tiers based on overall resident performance, aiming to compare programs of approximately equal caliber. For our measure of overall performance, we developed a knowledge subscale based on the 431 knowledge questions on the 2007 ABIM certifying examination. Similar to the ACM and AAM scores, the knowledge scores were scaled using the Rasch16,17 model and standardized on a scale of 200 to 800 for comparability across forms.

Statistical Analysis

We examined the relationship between the intensity of practice (EOL-VI) in the HRR of each residency program’s primary hospital and the mean ACM or AAM score of ABIM candidates trained in the program. Tests for trend were based on linear regression, in which the mean ACM or AAM score for a residency program (percentile) was the outcome and the exposure was practice intensity in the region (EOL-VI). Analyses were stratified by quartile into knowledge tiers, representing the overall performance of residents in the program. We conducted sensitivity analyses using different measures of the exposure as described above in the Intensity (Exposure) section. All analyses used analytic weights, equal to the number of candidates from the residency program, and were carried out in Stata, version 13.1 (Stata Corp).

Results

Candidate and Program Characteristics

The 357 internal medicine residency programs based in nonfederal fee-for-service US hospitals were located in 46 states and the District of Columbia; 39% were in the Northeast. The median number of first-time examination takers per residency program was 14. Certifying examination pass rates, by program, ranged from a low of 67% to 100%, the latter rate having been achieved by nearly half (47%) of all programs. The characteristics of the residency programs are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 357 Internal Medicine Residency Programs in the Studya

| Characteristic | Quintile of Intensity, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Lowest) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (Highest) | |

| Range of EOL-VIb | 15.5–26.2 | 26.3–29.2 | 29.3–36.6 | 36.7–45.3 | 45.4–60.5 |

| No. of programs | 74 | 74 | 67 | 72 | 70 |

| No. of residents taking the 2007 ABIM certifying examination |

|||||

| <10 | 28 | 31 | 33 | 21 | 11 |

| 10–14 | 30 | 22 | 27 | 33 | 17 |

| 15–24 | 18 | 24 | 21 | 15 | 41 |

| ≥25 | 24 | 23 | 19 | 31 | 30 |

| ABIM certifying examination (2007) pass ratec |

|||||

| ≤79% | 7 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 1 |

| 80%–89% | 19 | 18 | 15 | 11 | 17 |

| 90%–99% | 31 | 28 | 28 | 35 | 39 |

| 100% | 43 | 47 | 48 | 51 | 43 |

| Geographic region | |||||

| Northeast | 22 | 31 | 16 | 54 | 73 |

| Midwest | 34 | 16 | 34 | 36 | 0 |

| South | 23 | 45 | 34 | 8 | 13 |

| West | 21 | 8 | 15 | 1 | 14 |

Abbreviations: ABIM, American Board of Internal Medicine; EOL-VI, End-of-Life Visit Index.

Percentages are not weighted by number of individuals taking the examination in each program. Programs are stratified according to quintile of the primary exposure, utilization intensity (EOL-VI) in the hospital referred region of the residency program’s primary hospital.

The EOL-VI includes inpatient and outpatient visits.

Pass rate was rounded up to the nearest whole percentage point.

The mean age of the candidates was 32 years; 56% were men and 41%were international medical graduates. The vast majority (87%) had completed residency training the year they took the examination; 95% passed. More than half (55%) were pursuing subspecialty training. The characteristics of the candidates are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 6639 Graduates Taking the ABIM Certifying Examination for the First Time in 2007a

| Characteristic | Quintile of Intensity, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Lowest) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (Highest) | |

| No. of residents | 1267 | 1322 | 1159 | 1377 | 1514 |

| Male sex | 57 | 57 | 57 | 54 | 57 |

| Age, y | |||||

| 25–29 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 21 |

| 30–34 | 57 | 57 | 58 | 55 | 55 |

| 35–39 | 15 | 14 | 12 | 15 | 16 |

| 40–44 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 45–49 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥50 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Born in the United States or Canadab | 60 | 56 | 53 | 36 | 39 |

| International medical graduateb | 32 | 32 | 36 | 54 | 47 |

| Residency completion year relative to examination year |

|||||

| Same | 85 | 84 | 87 | 88 | 92 |

| 1 y Before | 12 | 13 | 10 | 10 | 7 |

| 2–4 y Before | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Subsequent subspecialty training (any) | 50 | 55 | 55 | 56 | 56 |

Abbreviations: ABIM, American Board of Internal Medicine; EOL-VI, End-of-Life Visit Index.

Stratified according to the quintile of the primary exposure, utilization intensity (EOL-VI) in the hospital referral region of their residency program’s primary hospital. EOL-VI included inpatient and outpatient visits.

Denominator is all individuals taking the examination; country of birthplace and medical school graduation were missing for 5% and 4% of the residents, respectively. International medical graduate signifies graduation outside the US and Canada.

ACM Scores

The ACM subscale showed satisfactory reliability across the 5 forms (0.62–0.66), comparable with other subscales routinely reported for ABIM examinations (eg, respiratory disease subscale reliability, 0.68).

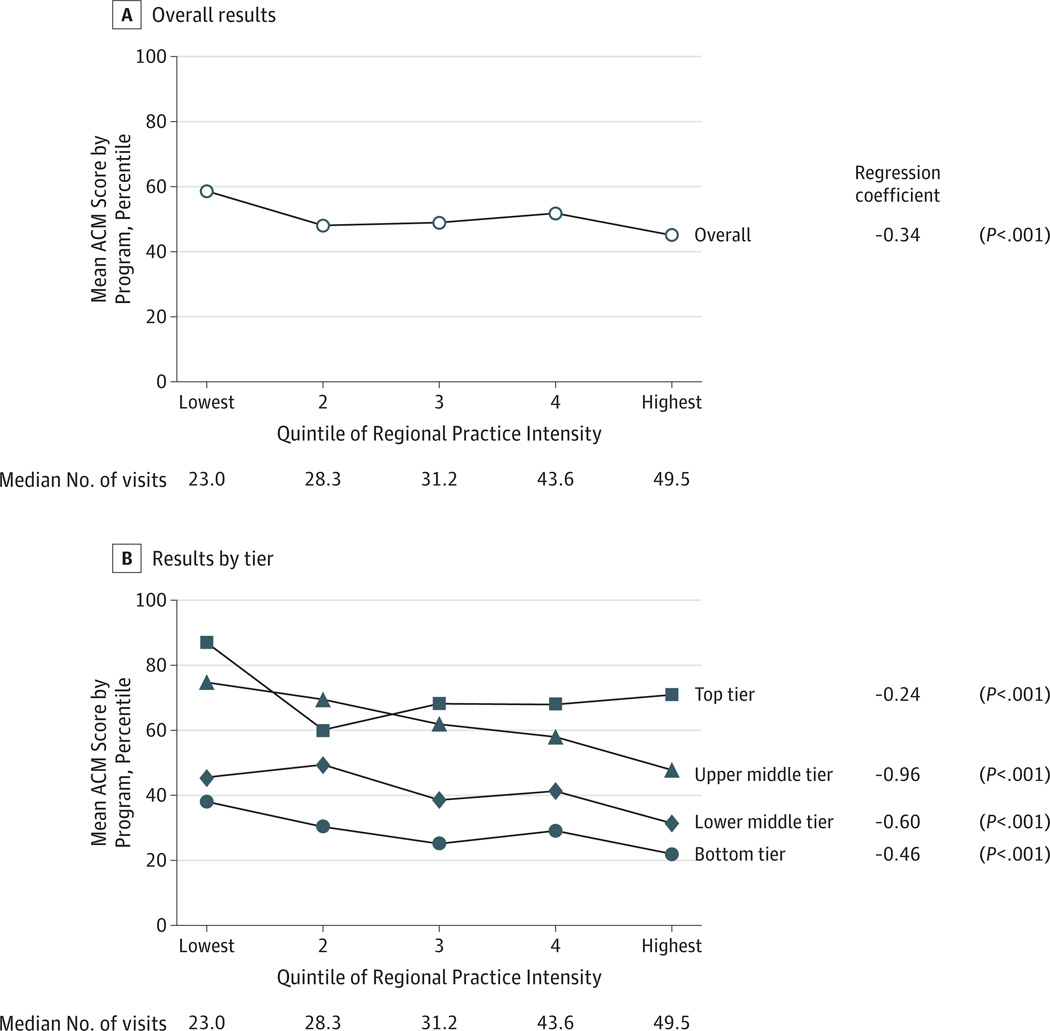

We found that residency programs in the lowest-intensity practice environments graduated residents with the highest (best) scores on the ACM subscale (P < .001); this relationship was observed in the overall analysis (all knowledge tiers combined) despite the likelihood of confounding by program caliber (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Association Between Intensity of Practice in the Region of a Residency Program’s Primary Hospital and Resident Scores on the Appropriately Conservative Management (ACM) Subscale.

A, Overall results. B, Results stratified by tier of residency program based on exam takers’ mean American Board of Internal Medicine certifying exam knowledge scores. Quintiles of regional practice intensity are based on the number of physician visits in the last 6 months of life (End-of-Life Visit Index). Regression coefficient is for the linear regression of the mean program ACM score (continuous) on the regional End-of-Life Visit Index (continuous).

In our primary analyses, stratified by overall caliber of the residency program (knowledge tier), we found strong inverse relationships between intensity of practice in the region (EOLVI) and ACM scores in each of the 4 knowledge tiers (Figure 2B). For example, in knowledge tier 4 (bottom tier), the mean ACM score ranged from the 38th percentile among graduates of programs in regions of lowest health care intensity to the 22nd percentile for programs in the highest-intensity regions, reflecting a mean decline in the ACM score of 0.46 percentile points (95%CI, 0.36–0.56) for each unit increase in EOL-VI. In knowledge tier 2, the mean ACM score ranged from the 75th percentile in the lowest-intensity regions to the 48th percentile in highest-intensity regions, reflecting a decrease of 0.96 percentile points (95%CI, 0.87–1.06) per unit increase in EOL-VI.

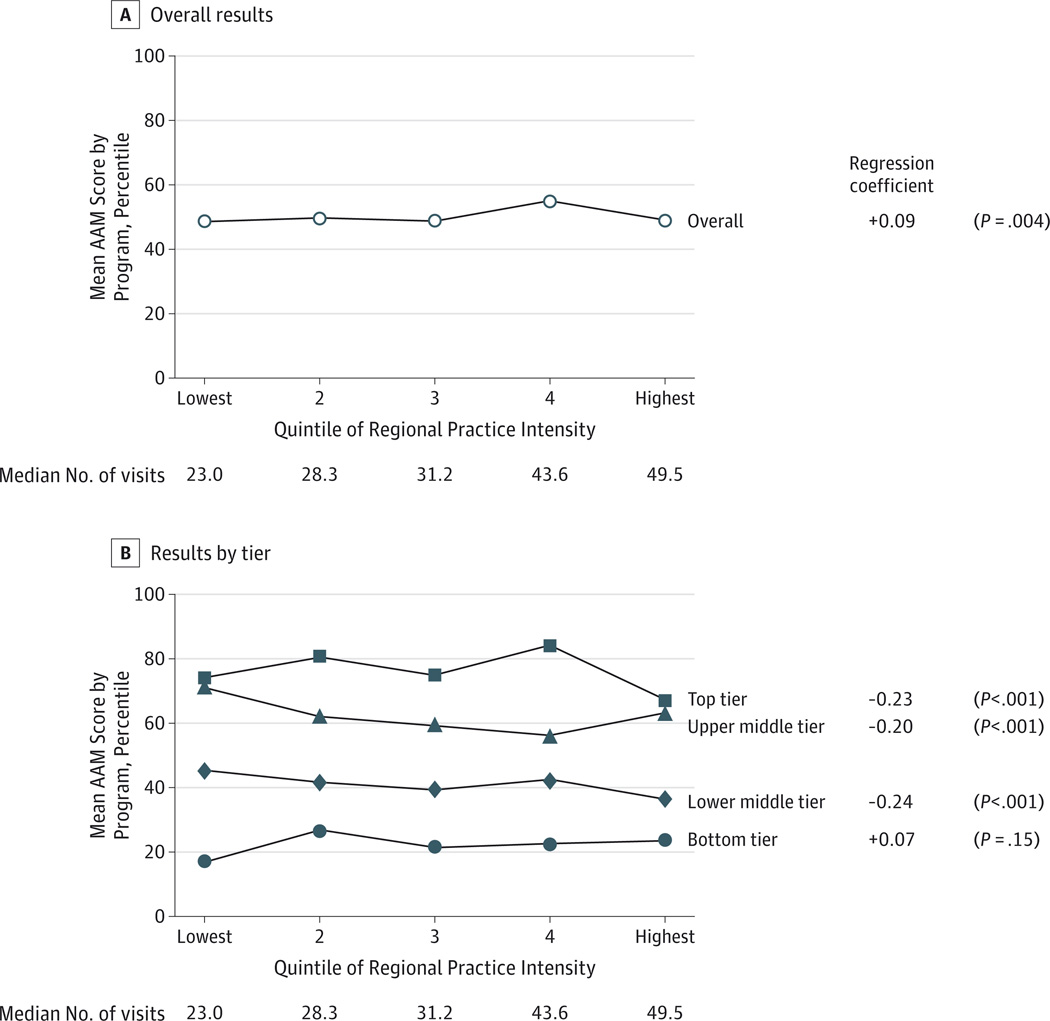

AAM Scores

The AAM subscale also showed satisfactory reliability (0.66–0.71) across the 5 ABIM examination forms. In the overall analysis, we observed a small positive association (P = .004) between EOL-VI and performance on the AAM subscale (Figure 3A). In our primary (stratified) analysis, in 3 of 4 knowledge tiers (all except the bottom tier), we found, paradoxically, that residency programs in the lowest-intensity practice environments graduated residents with the highest (best) AAM scores (Figure 3B). For example, in knowledge tier 2, the mean AAM score ranged from the 71st percentile for programs in the lowest-intensity regions to the 63rd percentile for those in highest-intensity regions, reflecting a mean decline of 0.20 percentile points (95%CI, 0.11–0.30) for each unit increase in EOL-VI. All effects were far smaller than those observed for the ACM subscale.

Figure 3. Association Between Intensity of Practice in the Region of a Residency Program’s Primary Hospital and Resident Scores on the Appropriately Aggressive Management (AAM) Subscale.

A, Overall results. B, Results stratified by tier of residency program based on exam takers’ mean American Board of Internal Medicine certifying exam knowledge scores. Quintiles of regional practice intensity are based on the number of physician visits in the last 6 months of life (End-of-Life Visit Index). Regression coefficient is for the linear regression of the mean program AAM score (continuous) on the regional End-of-Life Visit Index (continuous).

Sensitivity Analyses

We repeated our primary analyses of ACM scores (eFigure 1 in the Supplement) using spending as our measure of regional intensity, with nearly identical results. We then evaluated the intensity of practice (EOL-VI) in the primary training hospital (rather than the HRR) as our exposure. Stratifying by overall program caliber, we found an inverse association between hospital-level intensity and mean ACM score in 3 of 4 knowledge tiers (all except the top tier). The overall effect was null (not shown). For AAM scores, we observed mixed effects; there was no consistent evidence that residents who trained in hospitals with lower-intensity practice performed worse on the AAM subscale (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Using a newly developed subscale based on the ABIM certifying examination, we found that physicians’ ability to practice conservatively is predicted by practice intensity in the residency training environment. Specifically, internal medicine residency programs located in the regions of lowest practice intensity graduated residents whose scores on the appropriately conservative management subscale consistently exceeded, by up to 27 percentile points, those from programs in the regions of highest practice intensity. Residents trained in low-intensity regions were just as capable of practicing aggressively when appropriate. It therefore appears that residency training environment may play an important role in fostering a physician’s ability to recognize circumstances in which unnecessary, and potentially harmful, interventions should be avoided.

Health plans and other organizations have for many years been scrutinizing (via performance measures) whether physicians provide enough services to patients; only recently, however, have efforts begun to focus on the problem of overuse. The National Committee for Quality Assurance within the past decade introduced measures that address inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory infections,18 the Physician Quality Reporting System now includes measures focused on overuse,19 and the General Accounting Office has planned for several years to begin comparing resource use (or efficiency) across physicians.20 The ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely initiative,11 inviting specialty societies and other professional organizations to identify and educate constituents on 5 common interventions often ordered inappropriately, has received widespread endorsement as well as media attention. In the context of increasing recognition that interventional practice styles are associated with higher spending, no better outcomes, and potential harm to patients, such efforts no longer appear to be controversial.

This approach to addressing undesirable practice patterns—the carrot and stick approach epitomized by pay-for-performance schemes—has produced uneven results.21–23 An alternative or complementary approach may be to address individual practice variation at its source— if only we knew the source. Previous work10,24 has identified practice location (and local utilization patterns) as strongly predictive of individual practice tendencies (specifically, how interventional a physician’s practice style is). Other underlying sources of practice variation, implicated or conjectured, include competitive forces within local markets, financial incentive structures, and local malpractice climates. Social relationships and communication with colleagues have been found to be among the most potent influences reported by physicians.25–27 Our findings, which support similar pilot work using the 2002 ABIM certifying examination28 and recent work connecting training and subsequent practice quality,29 support the possibility that such relationships may be active and demonstrably influential during residency training. Specifically, residents who are mentored in the most intensive practice styles may be the least able to recognize when the wisest “intervention” is simply observation.

Our study has several limitations. First, some may question our choice of exposure: precise measurement of the intensity of practice experienced by residents during training is undeniably challenging. Using the common paradigm of claims-based measures to characterize local intensity of health care utilization, we identified physician visits a priori as the measure we believed would best represent residents’ perceptions of practice intensity, anticipating that it would capture the experiences, both inpatient and outpatient, of patients cared for by residents. An end-of-life cohort was used for the purpose of illness adjustment. We measured intensity at the regional rather than hospital level in our primary analysis for 2 reasons. First, because residents generally train at more than 1 hospital (typically in close proximity), area-level utilization may better reflect the intensity of practice to which they are exposed. Second, because patients may self-select at the hospital level, an analysis based on hospital-level utilization would be more subject to confounding by patient selection. We repeated our analyses twice, using an alternative regional measure of intensity (overall Medicare spending) and hospital level utilization as our exposure variable, and attained comparable findings, although coefficients for the hospital-level analyses were smaller in magnitude.

Second, the measurement of our outcome, the ability to practice conservatively, was based on responses to questions on a specialty board–certifying examination rather than on decisions made in practice. Prior work30–32 has shown direct relationships between board-certifying examination scores (pass/fail) and subsequent practice performance in clinical care. Performance on specific subscales of certifying examinations has also been correlated with prescribing and ordering practices of physicians.33,34

Finally, our inference ignores the possibility of selection bias, that is, that certain medical students may seek high-intensity practice environments rather than subsequently being molded by those environments. We are unable to refute this possibility. In analyses not presented, we excluded confounding, at least by measured program and resident characteristics, as an explanation of our findings. As with any observational study, however, unmeasured confounders remain a consideration. The distinction between selection and training effects, however, may largely be academic.35 If, as seems probable, the most likely unmeasured confounder is a graduate’s underlying (preexisting) tendency toward an interventional practice style, the implications for residency training and evaluation may be unchanged.

Conclusions

The residency training environment likely plays an important role in formulating practice style among trainees. When residents experience a certain style of practice—one that they may implicitly accept as correct—they appear to be more likely to adopt that style. Specifically, we observed that a high-intensity practice environment may teach residents to intervene inappropriately, at least on “paper.” In contrast, conservative training environments may promote more thoughtful clinical decision making at both ends (conservative and aggressive) of the spectrum of appropriate practice. We have also shown that appropriately conservative management ability can be measured using a subscale of the ABIM certifying examination. Just as residency programs can tailor the educational components of training to address deficiencies in specialty-specific examination subscales,12 they could also focus on addressing poor conservative management performance. The possibility that high-intensity training environments foster a practice style that may waste resources and harm patients through inappropriate intervention warrants attention. Reporting feedback to programs about residents’ performance on a prospectively designed appropriately conservative management certifying examination subscale might help address the problem of overuse and promote attention to value in medical practice in the United States.

Supplementary Material

Box. Coding of Sample Questions From the American Board of Internal Medicine Certifying Examination.

Correct response options are in boldface type. Incorrect response options that were determined by consensus to be more aggressive than the correct response were assigned a code of +1, response options determined to be more conservative than the correct response assigned a code of −1, and those considered approximately equivalent assigned a code of0. Questions for which all incorrect response options were more aggressive than the correct response qualified for inclusion in the Appropriately Conservative Management (ACM) subscale; those for which all incorrect response options were more conservative than the correct response qualified for inclusion in the Appropriately Aggressive Management (AAM) subscale.

Sample question 1 (ACM)

A 62-year-old woman comes to your office as a new patient for a periodic health evaluation. She has smoked 1 pack of cigarettes daily for over 30 years. She has not had cough, shortness of breath, or wheezing. She has hypertension, for which she takes hydrochlorothiazide. Spirometry shows FEV1 of 1.8 L (80% of predicted) and FVC of 2.4 L (90% of predicted); FEV1/FVC is 75%.

In addition to smoking cessation, which of the following should you recommend?

No additional therapy

Scheduled ipratropium bromide: coded as +1

Scheduled tiotropium: +1

Inhaled albuterol as needed: +1

Inhaled fluticasone as needed: +1

Sample question 2 (AAM)

A 38-year-oldwoman has had vague abdominal bloating and back pain for 2 to 3 months. She has not had dyspareunia or menorrhagia. Menses are occasionally irregular; her last menstrual period was 2 weeks ago. The patient takes no medications. She has one child.

Pelvic examination reveals a nontender right adnexal mass. Physical examination is otherwise normal. Papanicolaou test is normal. Pelvic ultrasonogram shows an irregular 10-cm right adnexal cystic mass with thick walls, septa, and areas of nodularity.

Which of the following is the most appropriate next step?

Repeat ultrasonography in 2 months: coded as −1

Oral contraceptive therapy and repeat ultrasonography in 2 months: −1

Fine-needle aspiration of the mass: −1

Surgical consultation

Sample question 3 (neither)

An asymptomatic 30-year-oldwoman comes to you for an initial health evaluation. At age 16, she had stage I Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the cervical lymph nodes and was treated with radiation therapy to the mantle field. She has been evaluated regularly and has no evidence of recurrence. Her last oncology evaluation was 8 months ago. She takes no medications.

Vital signs are normal. The thyroid gland is asymmetric with a 1.5 × 2.0-cm firm, nontender nodule in the left lobe. The cervical lymph nodes are not enlarged. Physical examination is otherwise normal. Serum thyroid-stimulating hormone is 5.5 U/mL (0.5–4.0), thyroglobulin is 5 ng/dL (less than 20), and free thyroxine (T4) is 1.2 ng/dL (0.8–2.4). Chest radiograph is normal.

Which of the following should you do?

Start l-thyroxine: coded as −1

Refer for total thyroidectomy: +1

Obtain fine-needle aspiration of the nodule

Obtain radioiodine (123i) scan of the thyroid gland: +1

Reassure the patient and reevaluate in 6 months: −1

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging grant PO1 AG19783. Dr Sirovich was supported by a Veterans Affairs Career Development Award in Health Services Research and Development at the time this work was initiated.

Role of the Sponsor: The National Institute on Aging had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional Contributions: The authors gratefully acknowledge the capable assistance of Nancy Rohowyj, BA, of the American Board of Internal Medicine, the thoughtful and wise counsel of Jason Rinaldo, PhD, of the American Board of Family Medicine, and the insistent encouragement and inspiration of Jon Skinner, PhD, of the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice.

Additional Information: All ABIM certifying examination data were processed within ABIM, primarily by Mary Johnston, and subsequently provided to Dr Sirovich, who conducted all analyses.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Sirovich had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Sirovich, Lipner, Holmboe.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Sirovich.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Sirovich, Lipner, Johnston.

Obtained funding: Sirovich.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Lipner.

Study supervision: Lipner.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Previous Presentations: A report of this study using earlier data was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting; April 29, 2006; Los Angeles, California,

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith C, Cowan C, Sensenig A, Catlin A Health Accounts Team. Health spending growth slows in 2003. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(1):185–194. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Congressional Budget Office. [Accessed October 7, 2013];How Have CBO’s projections of spending for Medicare and Medicaid changed since the August 2012 baseline? 2013 Feb 21; http://www.cbo.gov/publication/43947.

- 3.Business Week. [Accessed July 1, 2014];Is the US losing its competitive edge? in the World Economic Forum’s global competitiveness ranking, the US drops from first place to sixth thanks to its deficits and health care. http://www.businessweek.com/stories/2006-09-27/is-the-u-dot-s-dot-losing-its-competitive-edge-businessweek-business-news-stock-market-and-financial-advice.

- 4.US Government Accountability Office. Fiscal and Health Care Challenges. Washington, DC: US Government Accountability Office; 2007. Publication GAO-07-577CG. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending: part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):273–287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending: part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):288–298. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skinner JS, Staiger DO, Fisher ES. Is technological change in medicine always worth it? the case of acute myocardial infarction. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25(2):w34–w47. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.w34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed October 7, 2013];Medicare spending and financing fact sheet. http://kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/medicare-spending-and-financing-fact-sheet/. Published November 14, 2012.

- 9.Eisenberg JM. Physician utilization: the state of research about physicians’ practice patterns. Med Care. 1985;23(5):461–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sirovich BE, Gottlieb DJ, Welch HG, Fisher ES. Variation in the tendency of primary care physicians to intervene. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(19):2252–2256. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.19.2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing Wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801–1802. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haponik EF, Bowton DL, Chin R, Jr, et al. Pulmonary section development influences general medical house officer interests and ABIM certifying examination performance. Chest. 1996;110(2):533–538. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.2.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meredith LS, Cheng WJY, Hickey SC, Dwight-Johnson M. Factors associated with primary care clinicians’ choice of a watchful waiting approach to managing depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(1):72–78. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finkelstein JA, Stille CJ, Rifas-Shiman SL, Goldmann D. Watchful waiting for acute otitis media: are parents and physicians ready? Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1466–1473. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman DC, Esty AR, Fisher ES, Chang C-H. Trends and variation in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with severe chronic illness: a report of the Dartmouth Atlas Project. [Accessed October 7, 2013];Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/reports/EOL_Trend_Report_0411.pdf. Published April 12, 2011. [PubMed]

- 16.Cook L, Eignor D. IRT equating methods. Educ Meas. 1991;10:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolen MJ. Traditional equating methodology. Educ Meas. 1991;7:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS 2006 draft measures focus on overuse: monitoring, follow-up visits also addressed. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; [Accessed July 1, 2014]. http://www.mcnstayalert.com/Alerts/521/NCQA/HEDIS-2006-Draft-Measures-Focus-on-Overuse-of-Health-Care.htm. Published 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed July 1, 2014];US Department of Health and Human Services. 2014 Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) measures list. http://www.apapracticecentral.org/update/2014/01-16/measures-list.pdf. Published December 13, 2013.

- 20.Glendinning D. Medicare could start comparing resource use among doctors in 2008 [published online June 25-2007] [Accessed July 1, 2014];Am Med News. http://www.amednews.com/article/20070625/government/306259967/1/.

- 21.Mandel KE, Kotagal UR. Pay for performance alone cannot drive quality. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(7):650–655. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glickman SW, Ou FS, DeLong ER, et al. Pay for performance, quality of care, and outcomes in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007;297(21):2373–2380. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.21.2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Millett C, Gray J, Saxena S, Netuveli G, Majeed A. Impact of a pay-for-performance incentive on support for smoking cessation and on smoking prevalence among people with diabetes. CMAJ. 2007;176(12):1705–1710. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sirovich B, Gallagher PM, Wennberg DE, Fisher ES. Discretionary decision making by primary care physicians and the cost of US health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(3):813–823. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson J, Jay S. The diffusion of medical technology: social network analysis and policy research. Sociol Q. 1985;26:49–64. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Escarce JJ. Externalities in hospitals and physician adoption of a new surgical technology: an exploratory analysis. J Health Econ. 1996;15(6):715–734. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(96)00501-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freiman MP. The rate of adoption of new procedures among physicians: the impact of specialty and practice characteristics. Med Care. 1985;23(8):939–945. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sirovich BE, Lipner RS, Holmboe ES, Nowak KS, Poniatowski P, Fisher ES. When less is more: a new measure of appropriately conservative management based on the internal medicine certifying exam [abstract] J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:164–165. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asch DA, Nicholson S, Srinivas SK, Herrin J, Epstein AJ. How do you deliver a good obstetrician? outcome-based evaluation of medical education. Acad Med. 2014;89(1):24–26. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pham HH, Schrag D, Hargraves JL, Bach PB. Delivery of preventive services to older adults by primary care physicians. JAMA. 2005;294(4):473–481. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norcini JJ, Lipner RS, Kimball HR. Certifying examination performance and patient outcomes following acute myocardial infarction. Med Educ. 2002;36(9):853–859. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J, Rathore SS, Wang Y, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Physician board certification and the care and outcomes of elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(3):238–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamblyn R, Abrahamowicz M, Brailovsky C, et al. Association between licensing examination scores and resource use and quality of care in primary care practice. JAMA. 1998;280(11):989–996. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamblyn R, Abrahamowicz M, Dauphinee WD, et al. Association between licensure examination scores and practice in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288(23):3019–3026. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asch DA, Epstein A, Nicholson S. Evaluating medical training programs by the quality of care delivered by their alumni. JAMA. 2007;298(9):1049–1051. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.9.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.