Abstract

Chemokines are small proteins that function as immune modulators through activation of chemokine G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs). Several viruses also encode chemokines and chemokine receptors to subvert the host immune response. How protein ligands activate GPCRs remains unknown. We report the crystal structure at 2.9 angstrom resolution of the human cytomegalovirus GPCR US28 in complex with the chemokine domain of human CX3CL1 (fractalkine). The globular body of CX3CL1 is perched on top of the US28 extracellular vestibule, whereas its amino terminus projects into the central core of US28. The transmembrane helices of US28 adopt an active-state–like conformation. Atomic-level simulations suggest that the agonist-independent activity of US28 may be due to an amino acid network evolved in the viral GPCR to destabilize the receptor’s inactive state.

G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) engage a wide range of ligands, from small molecules to large proteins. The structures of GPCR complexes with small molecules and peptides have taught us much about recognition and activation mechanisms, including those of two human chemokine receptors bound to small molecules (1–4). However, proteins represent a substantial fraction of GPCR ligands for which there is currently a dearth of structural information.

Chemokines are protein GPCR ligands that function in immune modulation, wound healing, inflammation, and host-pathogen interactions, primarily by directing migration of leukocytes to inflamed or infected tissues (5, 6). One strategy that viruses use to evade the host immune response is to hijack mammalian chemokine GPCRs (7). Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) encodes US28, a class A GPCR with 38% sequence identity to human CX3CR1 (8). An unusually promiscuous receptor, US28 binds chemokines from different families including CX3CL1 (fractalkine), which is tethered to endothelial cell membranes through an extended stalk (9).

Here we present two crystal structures of US28 in complex with the chemokine domain of human CX3CL1. Both structures (one bound to an alpaca nanobody at a resolution of 2.9 Å and the other without a nanobody at 3.8 Å) reveal a paradigm for chemokine binding that is applicable to chemokine-GPCR interactions more generally. Furthermore, the structure of US28 in both crystal forms suggests that this viral GPCR has evolved a highly stable active state to achieve efficient agonist-independent constitutive signaling.

Overall structure of the US28-CX3CL1 complex

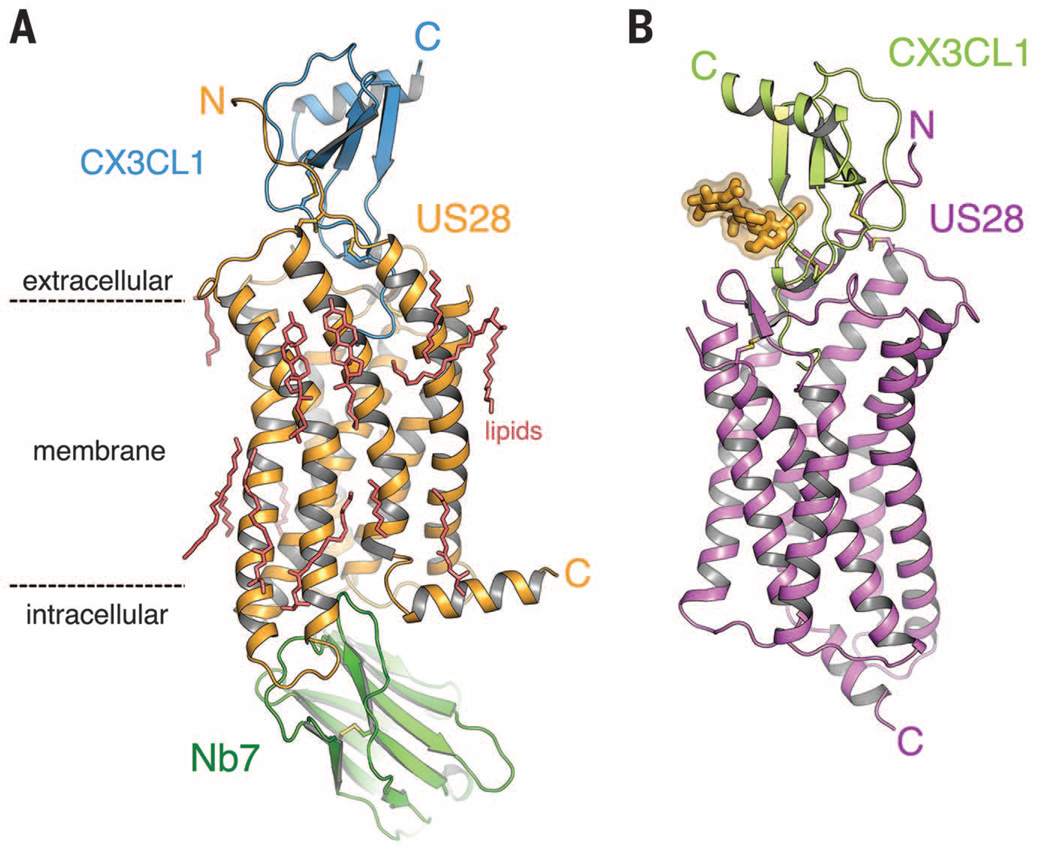

The structure of US28 bound to the 77-amino acid chemokine domain of CX3CL1 is essentially identical with (Fig. 1A) and without (Fig. 1B) bound nanobody 7 (Nb7), with a carbon-α root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.42 Å. Nb7, which was selected from an immunized alpaca cDNA library (fig. S1), binds to the intracellular surface of US28 by projecting its three CDR loops into a central cavity between the transmembrane (TM) helices (fig. S2). The only major difference between these US28 structures is the orientation of helix 8, which runs parallel to the membrane in the nanobody-bound structure. In the nanobody-free structure, crystal packing prevents helix 8 from assuming this orientation (fig. S3).

Fig. 1. Structure of US28 in complex with CX3CL1.

(A) Ternary complex of CX3CL1 (blue), US28 (orange), and nanobody (green) at 2.9 Å. (B) Binary complex of US28 (magenta) bound to CX3CL1 (light green). Asn-linked glycans are shown in yellow. C, C terminus; N, N terminus.

The body of CX3CL1 sits perched above the extracellular US28 vestibule, whereas its N terminus projects deeply into the central cavity of US28 and occupies the ligand binding pocket, burying a surface area of ~1600 Å2 (Fig. 1, A and B, and table S1). US28 accommodates this protein ligand by using its extracellular loops as “landing pads” upon which CX3CL1 sits. The CX3CL1 C terminus, truncated before the membrane-anchoring stalk, projects away from the complex. The globular body of CX3CL1 is less tightly constrained than its N-terminal peptide. Comparison of the two structures shows an ~2 Å wobble of CX3CL1 between the two crystal forms (fig. S4A), which may be rationalized by differences in crystal packing (fig. S4B).

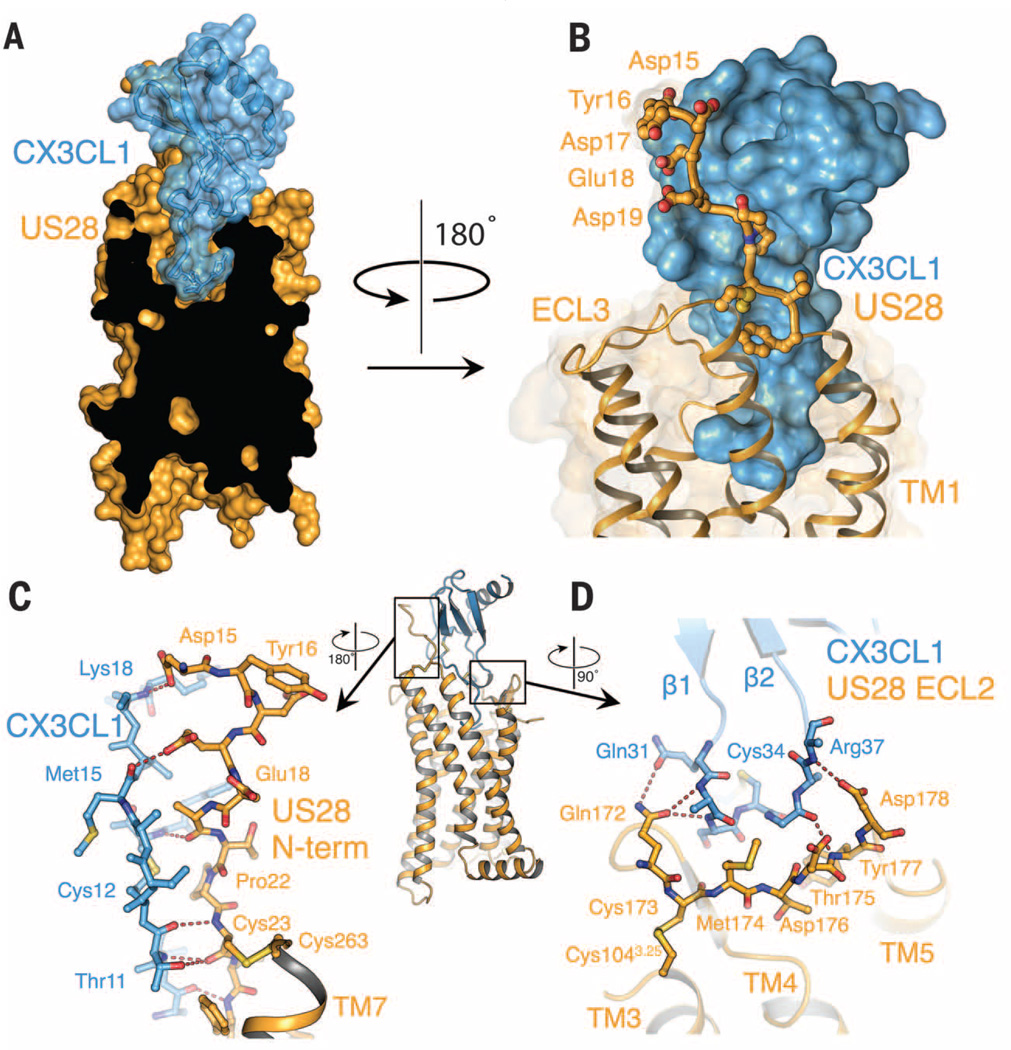

Engagement of a chemokine by US28

In the structure of the US28-CX3CL1 complex, the globular chemokine body interacts with the receptor N terminus and extracellular loops (ECLs) (site 1), whereas the chemokine N terminus enters the helical core of the receptor (site 2), in accord with a two-site model (10). Site 1 is occupied by the bulkiest region of CX3CL1, with its C-terminal α helix completely outside the extracellular vestibule of the receptor (Fig. 2A). In site 2, the N-terminal peptide of CX3CL1 (residues 1 to 7) reaches to the bottom of the extracellular cavity, occupying the site that accommodates small molecules in many GPCR structures (Fig. 2A).

The site 1 interaction accounts for most of the contact between US28 and CX3CL1, burying ~775Å2 with 13 hydrogen bonds and 44 van der Waals interactions (Fig. 2, B and C, fig. S5, and table S1). The principal feature of site 1 is the N terminus of US28 winding along an extended groove on the surface of CX3CL1 formed in the junction between the β sheet and the N loop (Fig. 2, B and C). A similar binding cleft is apparent in the structures of several other chemokines (fig. S6) (11). The disulfide bond from receptor Cys23 to the third extracellular loop aligns the receptor’s N terminus with the chemokine’s binding cleft. The preceding US28 residue, Pro22, introduces a kink in the receptor N-terminal peptide that enhances its shape complementarity to the chemokine. Contacts between the US28 N terminus and CX3CL1 involve some side chains but are primarily interactions between their peptide backbones (Fig. 2C and table S1). The extensive main-chain contacts may enhance the ligand cross-reactivity of US28. Another important site 1 contact exists between a short mini-helix of CX3CL1 and ECL2 of US28 (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2. Interaction of the US28 N terminus with CX3CL1 (site 1).

(A) Cutaway surface representation of CX3CL1 (blue) bound to US28 (orange). (B) The N-terminal region of US28 forms a large contact surface with CX3CL1. Side chains of US28 interacting with CX3CL1 are shown as sticks. (C) Amino acid interactions between CX3CL1 and US28 at chemokine binding site 1. The entire US28-CX3CL1 complex is shown for reference with the nanobody removed for clarity. (D) Amino acid interactions between US28 ECL2 and the β1–β2 loop of fractalkine.

Tyr16 is the second US28 N-terminal residue modeled into electron density (fig. S7B), and corresponds to the position of a sulfated tyrosine found in some chemokine receptors, although it is unclear whether US28 Tyr16 is sulfated. Many chemokines, including CX3CL1, contain strongly basic patches that are proposed to interact with sulfotyrosine in GPCR N-termini (fig. S6) (12, 13). However, Tyr16 is poorly ordered in US28 and does not appear to make specific contacts with CX3CL1.

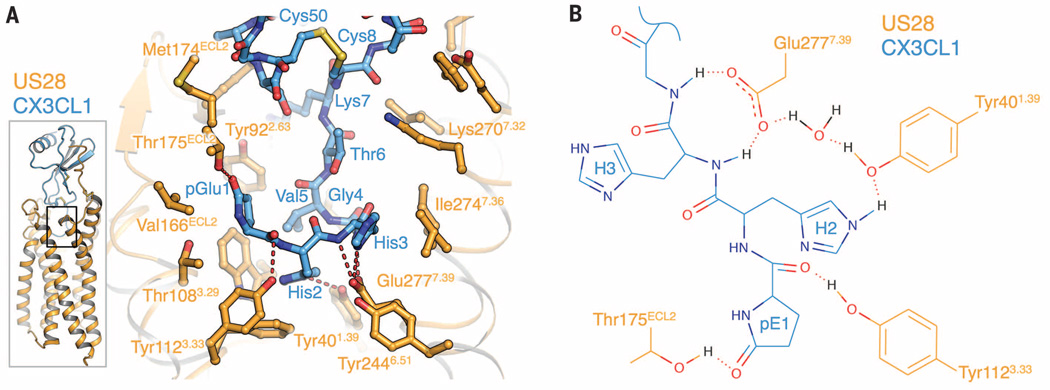

As with other chemokines, the CX3CL1 N terminus was found to be highly flexible in previous structural studies (14). In contrast, we find that the N terminus of receptor-bound CX3CL1 is well ordered, extending to the bottom of the US28 ligand binding pocket and burying 623 Å2 of surface area (Fig. 3A and fig. S7C). Residues 1 to 4 form a hooklike conformation at the base of the pocket, with residues 5 to 7 extending outward to link the N-terminal “hook” to the globular core of CX3CL1. CX3CL1 residue Gln1 is cyclized to form pyroglutamate (pGlu1) (Fig. 3, A and B), which is apparent both in the electron density map and by mass spectrometry (figs. S7C and S8). The CX3CL1 N-terminal hook contacts residues on TM1, TM3, TM7, and ECL2, with Tyr401.39, Tyr1123.33, Thr175ECL2, and Glu2777.39 of US28 participating in hydrogen bonds with pGlu1, His2, His3, and Gly4 of CX3CL1 (Fig. 3, A and B) [superscripts refer to Ballesteros-Weinstein nomenclature (15)]. Glu2777.39 may also form a salt bridge with CX3CL1 His3. The extensive interactions of Glu2777.39 with CX3CL1 provide a structural basis for the observation that Glu7.39 is important for chemokine receptor signaling (16).

Fig. 3. Interaction of the CX3CL1 N terminus with the US28 ligand binding pocket (site 2).

(A) Side chain contacts between CX3CL1 site 2 region (blue) and US28 (orange). (B) Two-dimensional plot of side-chain contacts between the CX3CL1 N-terminal hook and US28.

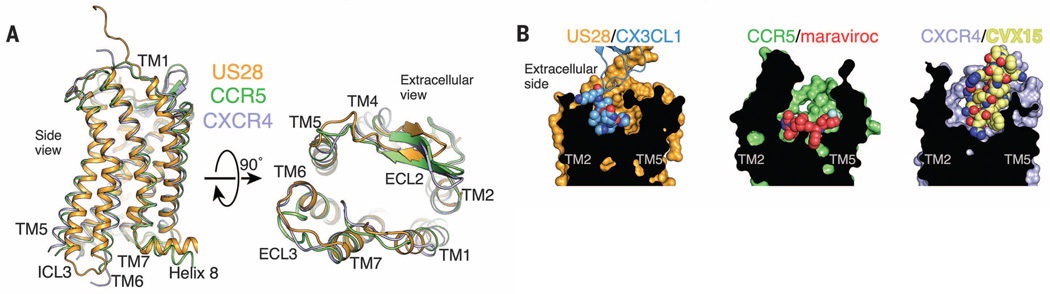

Comparison of the CX3CL1 binding mode with CXCR4 and CCR5 inhibitors

Human chemokine receptor structures have been previously reported as complexes with small-molecule (CCR5-maraviroc, CXCR4-IT1t) and peptide (CXCR4-CVX15) antagonists (2, 3). The overall helical structure of US28 superimposes closely with these structures (1.7 and 2.3 Å RMSD for CCR5 and CXCR4, respectively) (Fig. 4A). In the ligand binding pocket, maraviroc stretches across CCR5 from TM1 to TM5, whereas CX3CL1 occupies a smaller region of the ligand binding pocket concentrated toward TM1, TM2, TM3, and TM7 (Fig. 4B). The bonding chemistry of the maraviroc-CCR5 interaction grossly mimics the binding mode of CX3CL1 to US28, with the tropane and carboxamide nitrogens of maraviroc substituting for the His3 backbone amide and the His2 tau nitrogen of CX3CL1. The compact structure of CX3CL1’s N-terminal hook suggests a potential pharmacophore that could be mimicked by small molecules. Several small-molecule inhibitors of US28 signaling have been developed (17, 18). One of these, VUF2274, is a four-ring structure with strong benzhydryl character that could conceivably mimic the N-terminal hook peptide of CX3CL1. The structure of CXCR4 bound to the cyclic peptide CVX15 also presents an instructive comparison with US28-CX3CL1 (3). Like CX3CL1, CVX15 fills almost the entire extracellular vestibule of its receptor and makes multiple contacts with ECL2 but leans toward the opposite side of the receptor vestibule near TM4, TM5, and TM6 (Fig. 4B, right panel).

Fig. 4. Comparison of US28-CX3CL1 with chemokine receptor small-molecule and peptide complexes.

(A) Overall superposition of the US28 (orange), CCR5 (green; PDB ID: 4MBS), and CXCR4 (purple; PDB ID: 3ODU) TM helices from the side (left) and as viewed from extracellular space (right). (B) Surface cutaway side views comparing ligand binding modes for US28-CX3CL1 (orange-blue), CCR5-maraviroc (green-red; PDB ID: 4MBS), and CXCR4-CVX15 (purple-yellow; PDB ID: 3OE0).

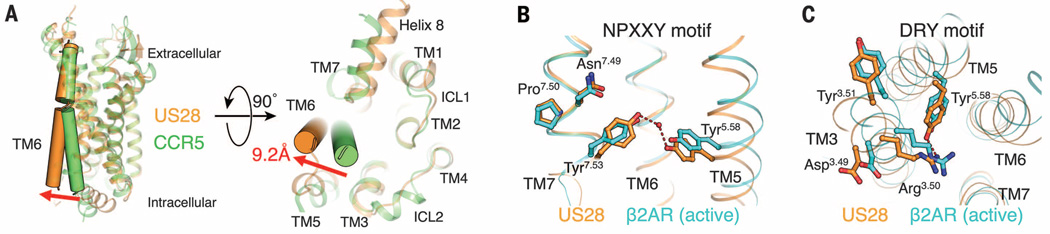

US28 TM conformations and implications for the active state

US28 has been shown to exhibit agonist-independent activity, with CX3CL1 reportedly diminishing signaling as an inverse agonist (19). We find that both the nanobody-bound and -free US28-CX3CL1 complexes bear the structural hallmarks of an active state, as seen in previous structures (20). Nb7 appears to recognize a preformed active-state conformation of US28 present in the nanobody-free US28-CX3CL1 complex. This finding suggests that the CX3CL1-bound form of US28 is indeed active, although it may occupy an activation state distinct from unliganded US28.

The conformation of TM6 in US28 is typical of an active-state GPCR (20). Compared with the inactive-state CXCR4 and CCR5 structures, US28 exhibits an outward movement (~9 Å) at the intracellular end of TM6 (Fig. 5A). Other conserved structural motifs also display signatures of receptor activation (20). These include the DRY motif (Asp1283.49, Arg1293.50, and Tyr1303.51) located at the intracellular side of TM3 and the NPXXY motif (Asn2877.49, Pro2887.50, and Tyr2917.53) in TM7. US28 Arg1293.50 of the DRY motif extends inward toward the center of the TM bundle, similar to the position seen in the active-state structure of the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) and contrasting with the corresponding arginine in the inactive CCR5 structure that projects away (Fig. 5C) (2, 21). The DRY motif can stabilize the inactive conformation of some GPCRs by participating in a salt bridge between Arg3.50 and an acidic residue at position 6.30, in what is known as the “ionic lock” (20, 22). US28 lacks an acidic residue at position 6.30, so absence of this contact could be one factor contributing to stabilization of the active state in the absence of ligand.

Fig. 5. Active-state hallmarks of US28 bound to CX3CL1.

(A) Comparison between the TM6 conformations of US28 (orange) and CCR5 (green; PDB ID: 4MBS). (B) The NPXXY motif of US28 (orange) forms side-chain contacts resembling the active-state conformation of β2AR (light blue; PDB ID: 3SN6). (C) The DRY motif of US28 (orange) forms side-chain contacts resembling the active-state conformation of β2AR (light blue).

Further structural evidence for the active state of US28 is demonstrated by the intracellular half of TM7, which is shifted toward the center of the TM bundle (Fig. 5A). This is seen in the active-state β2AR but not the inactive CCR5 structure (2, 21). The inward movement of TM7 results in Tyr2917.53 of the NPXXY motif shifting 7 Å toward the center of the TM bundle, which is close enough to TM5 and TM3 to form hydrogen bonds with Tyr2085.58 and Ile1223.43 through a water molecule (Fig. 5B). Tyr2085.58, in turn, forms a hydrogen bond with Arg1293.50 of the DRY motif (Fig. 5C). This completes a hydrogen bond network connecting TM3, TM5, and TM7 that has been seen in previously solved active-state structures (20, 21).

CX3CL1 has been shown to exhibit both agonist and inverse agonist activities in US28 signaling assays. This apparent discrepancy has been explained by CX3CL1 being a “camouflaged agonist” that signals but exhibits diminished agonist activity due to ligand-induced internalization and degradation (23). These structures support an interpretation that CX3CL1 is an agonist, not an inverse agonist, because it does not induce an inactive state of the receptor. CX3CL1 binding may either stabilize the ligand-independent active state of US28 or alter the active conformation to induce a slightly different signaling outcome from the unliganded state.

Structural basis for constitutive activity and ligand action

Constitutive activity is a common property of viral GPCRs that enhances viral pathogenesis (18) and is also seen to varying degrees in some mammalian GPCRs (24, 25). Although structures of certain constitutively active rhodopsin mutants are available (26, 27), the mechanistic basis through which viral GPCRs have gained this evolutionarily advantageous constitutive activity has remained unclear.

To address this question, we performed atomic-level molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of US28, both with and without bound CX3CL1 (see supplementary materials and methods). Atomic-level simulations have provided mechanistic insight into important functional properties of other GPCRs (28, 29). Because the crystal structures of US28 with and without the nanobody exhibit essentially identical conformations of the TM helices, we initiated our simulations from the 2.9 Å structure but omitted the nanobody.

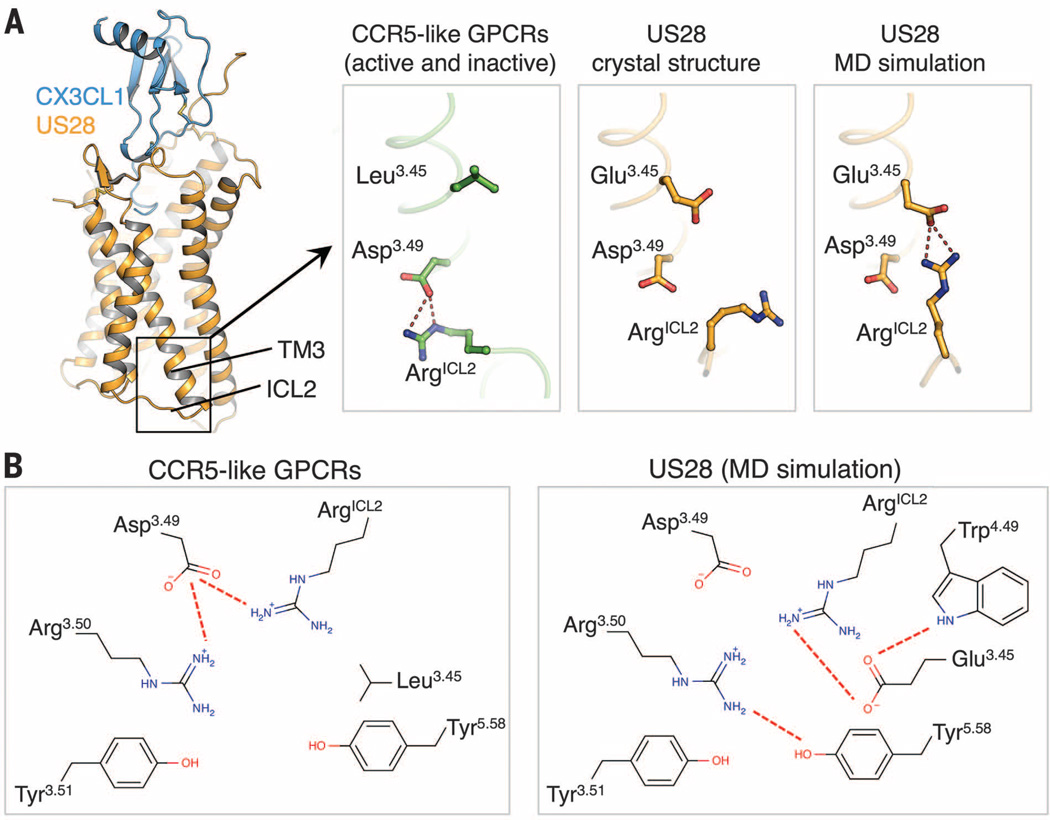

Using integrated analysis of sequence, structure, and simulations of US28, we uncovered molecular features of US28 that may lead to its constitutive activity. In particular, we found that US28 has evolved a distinctive structure environment around Asp1283.49, near the cytoplasmic end of TM3, that probably results in a destabilization of the receptor’s inactive state (Fig. 6). Asp3.49 is part of the conserved DRY motif, which plays an important role in the conformational transition between active and inactive states of class A GPCRs (20). An ionic interaction between Asp3.49 and the neighboring Arg3.50 generally stabilizes the inactive state of these receptors and is broken upon G protein coupling (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 6. Structural basis for the constitutive activity of US28.

(A) Conformations of ArgICL2 in CCR5 (green; PDB ID: 4MBS; left), the US28 crystal structure (orange; center) and the US28 MD simulations (orange; right). (B) Schematic diagram of the network of side-chain interactions surrounding the DRY motif in CCR5 (left panel) and US28 (MD simulation; right).

In many previously published GPCR structures, including all those of chemokine receptors, Asp3.49 engages in a polar interaction with another arginine residue separate from the DRY motif on the second intracellular loop (ICL2); this arginine residue points toward the interior of the TM helical bundle (Fig. 6A, left panel). Mutation of this arginine has been associated with constitutive activity (30), suggesting that this residue is important for stabilizing the inactive state. In the US28 crystal structure, the corresponding arginine, Arg139ICL2, is pointing outward, probably as a result of the crystal lattice contacts it forms (Fig. 6A and fig. S9).

In MD simulations of US28 embedded in a lipid bilayer, Arg139ICL2 immediately reorients toward the center of the bundle and assumes its most favored rotamer, but instead of contacting Asp1283.49, it forms an ionic interaction with Glu1243.45 (Fig. 6 and fig. S9B). This glutamate residue appears to function as an “ionic hook” that pulls Arg139ICL2 upward, preventing it from interacting with Asp1283.49 and, thus, potentially destabilizing the inactive state of the receptor (Fig. 6). Notably, the presence of a glutamate residue at position 3.45 is exclusive to the viral GPCR US28; it is not observed in any human class A GPCR. Together, these changes create a different constellation of interactions centered on the DRY motif that favors the formation and stabilization of an active conformation.

Several other distinctive features of US28 may also contribute to the environment of Asp1283.49 and destabilization of the inactive state. First, the ionic hook Glu1243.45 is held in place by a hydrogen bond to Trp1514.49 (Fig. 6B, right panel). Like Glu1243.45, the tryptophan residue at this position is also absent from all human class A GPCRs. Second, ICL2 is shorter by four residues in US28 than in most class A GPCRs, which appears to prevent the formation of an α helix in ICL2. When such an α helix does form in other GPCRs, it appropriately positions the ICL2 arginine to interact with Asp3.49, so the lack of ICL2 secondary structure in US28 may be providing Arg139ICL2 the flexibility required to adopt different structural states. Finally, in most other class A GPCR structures, including those of chemokine receptors, Asp3.49 engages in a hydrogen bond with the residue at position 2.39 in TM2. In US28, this residue is replaced by a glycine, which is incapable of forming such an interaction, while a serine introduced at the neighboring position 2.38 engages in a hydrogen bond with Asp1283.49; this shift appears to alter the side-chain conformation of Asp1283.49.

Other viral GPCR systems might have adopted a similar strategy to achieve constitutive activity. In US27 from HCMV, the position equivalent to the US28 ionic hook Glu3.45 is an asparagine residue, which is also absent from human class A GPCRs. In the Kaposi’s sarcoma–associated herpesvirus GPCR ORF74, Asp3.49 is mutated to Val3.49, preventing any ionic interaction with Arg3.50. Molecular tinkering with the GPCR regions important for conformational switching, such as the DRY motif and its immediate environment, may thus represent a common evolutionary strategy in viruses to achieve constitutive activity and enhance viral pathogenesis.

Summary

The structure of the human CX3CL1 chemokine domain bound to HCMV US28 serves as a model for other mammalian and viral chemokine GPCR-ligand complexes. The viral origins of US28 have allowed us to gain insight into the evolutionary strategies that viruses use to tune GPCR signaling properties to promote their survival and propagation. Furthermore, these viral-derived structural insights shed light on the mechanisms of ligand signal-tuning and constitutive activity of mammalian GPCRs as a whole. The tunability of US28, and perhaps other viral GPCRs, suggests that chemokine ligand-engineering strategies to elicit differential and biased signaling from GPCRs may be a productive way to create new agonistic and inhibitory ligands.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank B. Kobilka and members of the Kobilka lab for advice and discussions; S. Kim, N. Latorraca, and A. Sanborn for assistance with MD simulations and analysis; J. Spangler for helpful discussions; E. Özkan for assistance with data collection; and H. Axelrod for advice on refinement strategies. We also acknowledge beamline resources and staff of Advanced Photon Source GM/CA beamlines 23-ID-B and 23-ID-D and Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource beamline 12-2. We acknowledge support from the Cancer Research Institute (J.S.B.), Howard Hughes Medical Institute (K.C.G.), the Keck Foundation Medical Scholars Program (K.C.G.), NIH RO1 GM097015 (K.C.G.), a Terman Faculty Fellowship (R.O.D.), Swiss National Science Foundation (A.A.), NIH Pioneer award (H.L.P.), and Ludwig Foundation for Cancer Research (A.A.).

Footnotes

The data in this paper are tabulated in the main manuscript and in the supplementary materials. Structure factors and coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with identification (ID) numbers 4XT1 and 4XT3.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencemag.org/content/347/6226/1113/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S10

Tables S1 and S2

References (31–66)

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Katritch V, Cherezov V, Stevens RC. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013;53:531–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-032112-135923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan Q, et al. Science. 2013;341:1387–1390. doi: 10.1126/science.1241475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu B, et al. Science. 2010;330:1066–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.1194396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenbaum DM, Rasmussen SG, Kobilka BK. Nature. 2009;459:356–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charo IF, Ransohoff RM. Engl. N. J. Med. 2006;354:610–621. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proudfoot AE. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:106–115. doi: 10.1038/nri722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sodhi A, Montaner S, Gutkind JS. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:998–1012. doi: 10.1038/nrm1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chee MS, Satchwell SC, Preddie E, Weston KM, Barrell BG. Nature. 1990;344:774–777. doi: 10.1038/344774a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bazan JF, et al. Nature. 1997;385:640–644. doi: 10.1038/385640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thiele S, Rosenkilde MM. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014;21:3594–3614. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666140716093155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szpakowska M, et al. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012;84:1366–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Millard CJ, et al. Structure. 2014;22:1571–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veldkamp CT, et al. Sci. Signal. 2008;1:ra4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1160755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizoue LS, Bazan JF, Johnson EC, Handel TM. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1402–1414. doi: 10.1021/bi9820614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H. Methods Neurosci. 1995;25:366–428. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brelot A, Heveker N, Montes M, Alizon M. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:23736–23744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casarosa P, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:5172–5178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210033200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vischer HF, Siderius M, Leurs R, Smit MJ. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:123–139. doi: 10.1038/nrd4189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vischer HF, Leurs R, Smit MJ. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2006;27:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venkatakrishnan AJ, et al. Nature. 2013;494:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nature11896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasmussen SG, et al. Nature. 2011;477:549–555. doi: 10.1038/nature10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palczewski K, et al. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waldhoer M, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:19473–19482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilliland CT, Salanga CL, Kawamura T, Trejo J, Handel TM. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:32194–32210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.503797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han X. Adv. Pharmacol. 2014;70:265–301. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-417197-8.00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deupi X, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:119–124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114089108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Standfuss J, et al. Nature. 2011;471:656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature09795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dror RO, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:18684–18689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110499108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dror RO, et al. Nature. 2013;503:295–299. doi: 10.1038/nature12595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burstein ES, Spalding TA, Brann MR. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:24322–24327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]