Abstract

Bispecific T cell engagers are a new class of immunotherapeutic molecules intended for the treatment of cancer. These molecules, termed BiTEs, enhance the patient’s immune response to tumors by retargeting T cells to tumor cells. BiTEs are constructed of two single chain variable fragments (scFv) connected in tandem by a flexible linker. One scFv binds to a T cell-specific molecule, usually CD3, while the second scFv binds to a tumor-associated antigen. This structure and specificity allows a BiTE to physically link a T cell to a tumor cell, ultimately stimulating T cell activation, tumor killing and cytokine production. BiTEs have been developed that target several tumor-associated antigens for a variety of both hematological and solid tumors. Several BiTEs are currently in clinical trials for their therapeutic efficacy and safety. This review examines the salient structural and functional features of BiTEs as well as the current state of their clinical and preclinical development.

Keywords: BiTE, blinatumomab, bispecific antibodies, T cell re-targeting

Introduction

In the last six decades, medicine has seen dramatic improvements its arsenal for treating cancer. The traditional trifecta of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy has been expanded to include the rapidly growing field of immunotherapy, which aims to enhance the immune system’s ability to eradicate tumors. Within immunotherapy there are multiple strategies for achieving anti-tumor activity, one of which is immune effector cell retargeting. In effector cell retargeting, cells such as natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, and cytotoxic T lymphocytes are brought into contact with target tumor cells through one of their activating receptors to allow cytotoxic responses to be triggered. Although retargeting NK cells or macrophages has definite benefits, T cell retargeting may have the greatest potential as anti-neoplastic therapy. The extensive expansion these cells undergo upon activation and their ability to activate host immunity give T cells particular therapeutic power. Furthermore, by directing T cells to tumors, these potent effectors can target tumor cells specifically with a precision that standard chemotherapy and radiation cannot.

Multiple methodologies exist for directing T cells to tumor cells. These include cell-based therapies, such as the highly potent chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-expressing T cell therapies (reviewed in 1, 2), and a rapidly growing body of antibody-derived molecules that passively link target and effector cells. These cell-linking antibodies belong to a class of antibodies known as bispecifics. Unlike standard antibodies that have specificity for a single antigen, bispecific antibodies have dual antigen specificity, allowing them to bind to two unique antigens at once and thereby facilitate cell-to-cell interactions. While bispecific antibodies take several forms, the following review will examine a particular bispecific format that has been developed specifically for the purpose of T cell retargeting: the bispecific T cell engager, or BiTE. Herein, the salient structural and functional elements of BiTEs as well as the current state of their clinical development will be reviewed.

Retargeting T-cells: An old idea coming into its own

The concept of using T cell retargeting for cancer therapy stretches back to the 1970s. Unlike macrophages, dendritic cells, and other accessory cells, T cells are present in copious numbers, expand rapidly upon activation, give robust and durable cytotoxic responses, and have the potential to generate immunologic memory. Furthermore, T cells have been found to attack tumors from the outside as well as infiltrating into the tumor. These features make T cells optimal therapeutic effectors for cancer. T cell redirection does suffer one significant challenge, which is the requirement of a second stimulatory signal to achieve full T cell activation and prevent anergy. Multiple bispecific formats have been developed to meet or circumvent this requirement.

Practical use of bispecific antibodies to retarget T cells began in the 1980s with the production of the first T cell-engaging trispecific antibodies.3–5 These molecules were generated using the hybrid-hybridoma (quadroma) method, yielding antibodies with a unique antigen binding specificity in each arm as well as a complete Fc domain capable of binding Fc receptors. Although these original trispecifics suffered significant problems with production, the format was perpetuated thanks to improved production methods developed by Lindhofer et al.5, 6 Lindhofer’s improved quadroma method utilized hybridomas of two distinct forms—mouse IgG2a and rat IgG2b—to generate triomabs that were both easy to isolate and which would bind preferentially to activating Fc receptors. With these molecules, secondary T cell stimulation was provided by macrophages and other accessory cells, which bound to the triomab’s Fc domain and were themselves activated. While triomabs were and continue to be successful both in vitro and in vivo, concern has been placed on the possibility that Fc receptor interactions could lead to undesirable effects, such as dampening of immune responses by M2-macrophage-produced IL-10.5, 7 As a result, effort has been made to develop T cell-targeting bispecifics that lack Fc receptors. This has contributed particularly to the development of bispecific T cell engagers.

Structure and physiology of bispecific T cell engagers

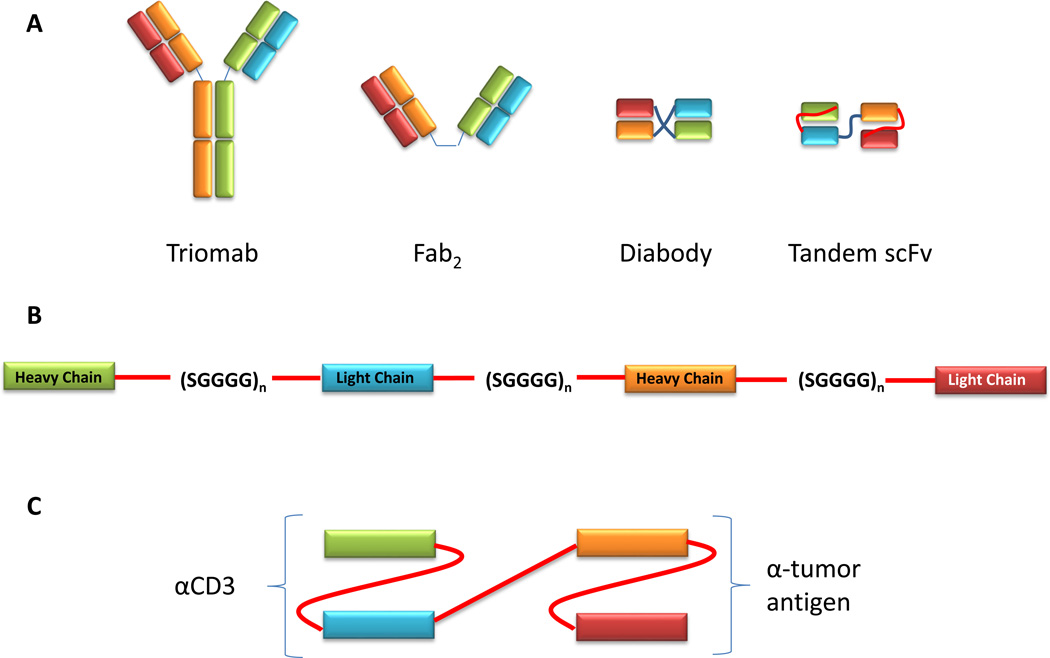

As noted, BiTEs are members of the bispecific class of antibodies. This class consists of antibodies or derived proteins that have multiple binding sites each with a unique antigen specificity (Figure 1). This configuration allows the bispecific antibody to physically bridge two or more cells, with one binding region binding to an antigen on one cell and another binding region associating with an antigen on a different cell.

Figure 1.

Overall BiTE structure. (A) Bispecific antibodies can take a variety of formats, which vary in size and complexity. Triomabs are full sized antibodies generated from the fusion of two hybridomas. Fab2 consist of two unique antigen full Fab binding fragments, which are physically linked together. Diabodies and tandem single chain variable fragments utilize only variable fragments to bind cognate antigens. Diabodies and tandem scFvs differ in how the heavy and light chains are connected to one another, with diabodies linking heavy and light chains from opposing Fvs while tandem scFvs connect heavy and light chains linearly as a single molecule. (B) Layout of a tandem scFv. The heavy and light chains of the two Fvs are linked by short serine-glycine linkers. This linkage results in the formation of a single polypeptide that incorporates both Fvs. (C) Bispecific T cell engager. A bispecific T cell engager (BiTE) is a type of tandem scFv in which one scFv is capable of binding to a T cell. Often, this scFv recognizes the CD3 subunit of the T cell receptor. The second scFv binds to an antigen on tumor cells.

In BiTEs, the dual specificity is achieved in a structure that is much smaller than a traditional antibody molecule. These BiTE molecules are known as tandem scFvs and are composed of two single chain variable fragments (scFv) each with a unique antigen specificity (Figure 1). Each scFv is generated by connecting the heavy and light chains of each Fv with a serine-glycine linker sequence. The linker is generally constructed of three or more SGGGG repeats, making the peptide sufficiently long and flexible to allow the heavy and light chains to associate in a normal conformation. A similar SGGGG repeat linker connects the two scFvs. The length of this linker determines the flexibility of movement between the two scFvs and can be adjusted by including more or fewer repeats to optimize binding to both target cells. The entire BiTE molecule consists of one continuous polypeptide. The complete BiTE molecule is approximately 55 kDa in size and approximately 11 nm in length.8

Distinguishing BiTEs from other tandem scFvs is their specificity for binding to the T cell receptor (TCR) complex. In these molecules, one scFv often targets the CD3 subunit of the TCR. Specificity for CD3 is what allows a BiTE to activate T cells through TCR complex stimulation. The second scFv in a BiTE targets a selected tumor antigen. As with other types of antibody-mediated therapies, a primary goal in selecting the target antigen is to choose one with cell surface expression on tumor cells but minimal expression on normal tissues. This strategy minimizes the likelihood of unintended on-target off-tumor responses while optimizing the likelihood of effective tumor-specific targeting.

Although the mechanism by which BiTEs promote T cell killing of tumor cells is not fully understood, several features of this process have been described. Foremost, the linkage of T cells to tumor cells is central to the BiTE’s cytotoxic mechanism. BiTEs must bind simultaneously to both the T cell and the tumor-associated antigen to elicit cytotoxic activity from the T cell. It has been shown that activation of T cells by BiTEs is strictly dependent upon target cell binding. Brischwein and colleagues reported that T cells could be activated to lyse tumor cells by an epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM)-specific BiTE but not in the absence of target cells or when the target cells expressed a binding-incompetent ligand.9 Lack of dual binding also prevented expression of cytokines—including interferon gamma, tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-6, and IL-10—that were upregulated when T cells and tumor cells simultaneously bound the BiTE.9 Single-sided binding of BiTE molecules to T cells is insufficient to either activate T cells9 or to induce anergy.10 This strict dependence on simultaneous T cell-tumor cell binding circumvents the issue of undesired T cell activation and makes BiTE molecules exquisitely selective for target cells.

Another key observation informing BiTE’s cytotoxic mechanism is that BiTEs can induce the formation of cytolytic immunological synapses. Offner and colleagues used confocal immunofluorescence to examine the formation of immunological synapses between T cells and tumor cells in the presence of EpCAM-specific BiTEs.11 Synapses formed between erbB2-specific CD8-positive T cells and EpCAM+ tumor cells in the presence of a EpCAM-specific BiTE displayed both central and peripheral supramolecular activation clusters, with central localization of perforin, PKCθ, Lck, and CD3 and peripheral localization of CD11A/LFA1.11 These BiTE-dependent synapses were compared to synapses formed between erbB2 peptide-specific SuHie7 T cells and erbB2 peptide-bearing tumor cell lines and found to be identical in structure and molecular composition. The formation of these synapses suggests that cytotoxity results from degranulation of T cells at these junctures. Consistent with the presumption, it has been reported that chelation with EGTA to block calcium-dependent degranulation prevents BiTE-dependent cytotoxicity.12, 13 Dependence of BiTE-mediated cytotoxicity on perforin and/or granzyme, however, has not been demonstrated in vivo.

A unique feature of BiTE-mediated T cell activation is a lack of dependence upon T cell costimulation. Studies of BiTEs with a variety of specificities have demonstrated that BiTEs induce significant cytotoxicity by T cells in the absence of costimulation, such as through anti-CD28 antibodies and IL-2.9, 14–17 Among bispecific antibodies, this characteristic is unique to BiTEs, as other bispecific formats have been found to require the presence of costimulation for cytotoxic activity.18–20 Although the reason for this lack of requisite costimulation is unclear, it likely reflects an alternate mechanism of T cell activation. One possibility is that many TCRs cluster within the induced immunological synapse, triggering signaling. Another potential explanation is that memory T cells, which require less stimulation to be fully activated, may be the predominant effector cells in BiTE-mediated cytotoxicity. Consistent with this hypothesis, it has been observed that BiTE-mediated cytotoxicity preferentially occurs through previously primed T cells. Dreier and colleagues reported that CD8+/CD45A+ naïve T cells did not mediate tumor cell lysis in the presence of BiTE while CD8+/CD45O+ memory T cells had robust lysis.14 Clarifying how BiTEs elicit cytotoxicity without costimulation will require further investigation of how TCRs interact when bound to tumor cells through BiTEs, the timing of T cell activation following binding, and requirement for various cytolytic molecules for cytotoxicity.

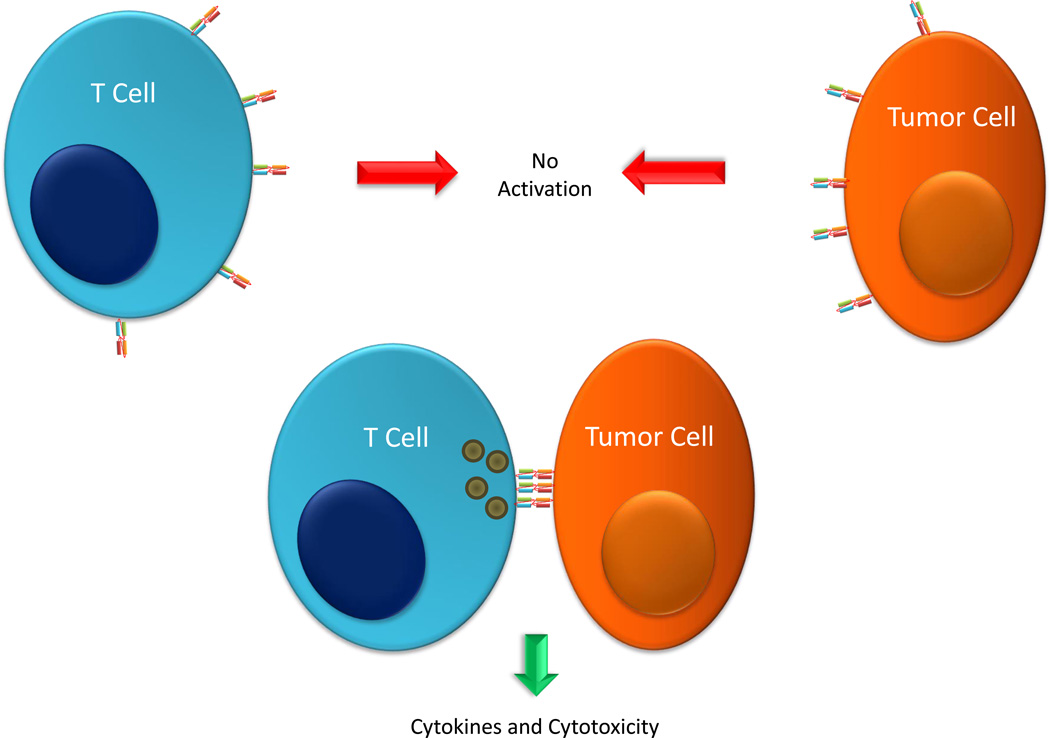

These observations of dual-binding dependence, lack of costimulation, and synapse formation inform the development of a model of BiTE-mediated cytotoxicity. In such a model, multiple BiTE-mediated binding events occur between a T cell and a tumor cell promoting clustering of T cell receptors. This clustering precipitates the formation of an immunological synapse, stimulation of the T cell, and release of cytotoxic molecules and cytokines, resulting in tumor cell lysis and immune activation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Activation of T cells by BiTEs. To induce activation of and cytotoxic activity by a T cell, a BiTE protein must engage both a T cell and a tumor cell simultaneously, so single cell binding to a T cell or a tumor cell causes no activation. Simultaneous binding of multiple BiTE molecules to both T cell and tumor cell promotes the formation of an immunological synapse leading to T cell activation and release of cytokines and cytotoxicity of the tumor cell.

BiTE pharmacology

From a pharmacologic perspective, BiTEs bear a number of features that are advantageous as well as potentially disadvantageous. Foremost among their advantages is the high efficacy with which BiTEs elicit biological responses. These molecules have been found to be highly potent both in vitro and in vivo. In vitro studies have demonstrated the ability of BiTEs to direct T cell activity. Hoffmann et al. reported that addition of 50 ng/mL of BiTE to a co-culture of T cells and target tumor cells caused the T cells to home to the tumor cells.21 Furthermore, BiTEs have been shown to promote cytokine production from T cells when co-cultured with target tumor cells.22 Additional studies with various types of target cancer cells have demonstrated the ability of exceptionally low amounts of BiTEs to induce tumor cell lysis. Mack et al. reported ~50 percent specific lysis with as little as 1.6 ng/mL at a 20:1 E:T ratio.23 Consistent studies with anti-CD3 x anti-PSCA and anti-CD3 x anti-PSMA BiTEs in prostate cancer lines report ≧ 50 percent specific lysis at 30 pmol/mL at 1:1 E:T and 1 ng/mL at 5:1 E:T, respectively.24, 25 The findings reveal not only the ability of exquisitely small amount of a BiTE to promote cell killing, but also demonstrate the efficacy of these molecules at low E:T ratios.

The efficacy of BiTEs as therapeutics has also been demonstrated in a variety of animal models and in humans. Studies of MT110, an anti-EpCAM x anti-CD3 BiTE, in mouse xenograft models have shown that microgram doses of this agent are able to suppress the establishment and promote tumor regression of colorectal cancer cell line xenografts as well as promoting tumor regression in primary ovarian cancer explants.22, 26 More recent studies have shown that this BiTE can prevent growth of tumors from CD133+ cancer stem cells using microgram doses.26, 27 The use of small doses of BiTEs has also been observed in the clinic, with markedly low amounts of BiTE able to induce complete and partial responses. In a phase I trial of blinatumomab, an anti-CD3 x anti-CD19 BiTE, complete and partial responses were observed at doses of 15, 30, and 60 ug/m2 per day in non-Hodgkin B cell lymphoma patients.28 These observations highlight the potency of these agents. This feature also has practical benefit, as it places less demand on manufacturing to produce the needed quantities of protein.

The pharmacokinetic properties of BiTEs present both benefits and challenges to their clinical use. Unlike full antibody molecules, whose persistence in the blood is maintained by an FcR-mediated recycling mechanism29, 30, small antibody-based proteins like BiTEs have a relatively short serum half-life. Kinetic studies of these molecules reveal distribution and elimination half-lives on the order of hours. A report based on murine experiments described a half-life of approximately 8 hrs,25 while studies in a chimpanzee reported approximately 2 hrs,31 and human clinical studies found BiTE half-lives with an average of 1.25 hrs.32 While reflecting clearance from the serum, these half-life values may not reflect the amounts of BiTE bound to cells, thus underestimating the persistence of these molecules in the immune system. The short protein half-life presents a therapeutic challenge, as the rapid dissipation makes it difficult to maintain serum levels with bolus or intermittent infusion. This challenge has been met by the use of constant infusion pumps.33 While posing a challenge, it has been noted by many that these short serum half-lives allow for precise control of BiTE levels within the patient,34, 35 enhancing their potential safety.

Understanding the safety of BiTEs is still developing as information from clinical trials is gathered. To date, much of what is known about BiTE safety comes from trials of blinatumomab, an anti-CD19 BiTE. Phase I and II studies of blinatumomab have reported major adverse events as seizures and cerebellar effects, which were completely reversible.28, 33 Many patients experienced less severe side effects such as fever and chills. Additional major toxicities of lymphopenia and leukopenia may be blinatumomab-specific due to the nature of targeting CD19, which is expressed on all B lymphocytes. Cytokine release syndrome can occur and has been observed in pediatric patients.36 As additional BiTEs progress through clinical trials a more complete picture of the toxicity profile of these molecules will be developed.

BiTEs in development and the clinic

The great specificity and efficacy of BiTEs has made this platform an attractive system for treating cancer. Accordingly, BiTEs targeting a variety of tumor-associated antigens have been generated and investigated. BiTEs have been developed to target a number of different malignancies, including both solid and hematologic tumors (Table 1).

Table 1.

BiTEs in clinical and preclinical assessment

| Target | Name | Target Disease | Clinical Status | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD19 | Blinatumomab/MT-103/MEDI-538 | NHL, ALL | Phase I/II/III | 13, 28, 32, 33, 40, 41 |

| EpCAM | MT110 | Solid tumors | Phase I | 22, 26, 27, 43 |

| CEA | MT111/MEDI-565 | GI adenocarcinoma | Phase I | 12, 15 |

| PSMA | BAY2010112/AMG112 | Prostate | Phase I | 25 |

| CD33 | AML | Preclinical | 49, 50 | |

| EGFR | Colorectal cancer | Preclinical | 16 | |

| Her2 | Preclinical | 46 | ||

| EphA2 | bscEphA2xCD3 | Multiple solid tumors | Preclinical | 38 |

| MCSP | MCSP-BiTE | Melanoma | Preclinical | 17 |

| ADAM17 | A300E | Prostate cancer | Preclinical | 39 |

| PSCA | Prostate cancer | Preclinical | 24 | |

| 17-A1 | Preclinical | 23 | ||

| NKG2D ligands | Multiple solid and liquid tumors | Preclinical | 48 |

Most of the BiTEs reported to date have displayed similar anti-tumor properties. The first BiTE was reported by Mack et al. in 1995 and targeted the epithelial antigen 17-1A, which was thought to be a marker for residual colorectal cancer.23, 37 This molecule was shown in vitro to promote killing of 17-1A-bearing colorectal cancer cells by human T cells.23 Subsequently, molecules targeting epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM),11, 22 epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR),16 carcinoembrionic antigen (CEA),12 ephrin type-A receptor 2 (EphA2),38 and other antigens have been developed with an aim for treating solid malignancies. Like the 17-1A-targeting BiTE, these molecules display in vitro cytotoxicity against tumor cells,23–25, 39 and they have shown the ability to restrain tumor growth and reduce tumor burden in murine models.22, 26 Collectively, these molecules represent what may be an impressive addition to the anti-cancer arsenal.

Blinatumomab (MT-103)

The BiTE most advanced in clinical trials to date is blinatumomab that targets CD19+ malignancies. Developed by Micromet (Amgen), this molecule was the first BiTE to reach clinical trial in the mid-2000s. Blinatumomab is designed to target B cell-derived malignancies including non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). The salient features of the molecule were first described by Loffler, wherein the ability of the BiTE to direct unstimulated T cells to CD19-positive cell lines was demonstrated13 and was later demonstrated to facilitate elimination of B cells from chronic lymphocytic leukemia patient samples.40 The first data from a phase I clinical trial with blinatumomab came in 2008. The study reported an acceptable toxicity profile and found the molecule to be highly potent, with patients showing complete and partial remission of tumors after being treated with as little as 15 ug/m2/day.28 A further phase II trial examined the ability to blinatumomab to eliminate minimal residual disease in adult ALL.33 In this case, 15 ug/m2/day blinatumomab was able to eliminate disease in 16 of 20 patients and provide a durable remission out to 33 months.41 At present additional phase II as well as phase III trials are underway to investigate the efficacy of blinatumomab against adult ALL, diffuse large B cell lymphoma, Philadelphia chromosome- and BCR-ABL-positive ALL, and childhood ALL (Table 2).

Table 2.

Current Clinical Trials*

| Phase | Name | Target Disease | NCT# |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Blinatumomab | Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma | NCT00274742 |

| I | MT111/MEDI-565 | Gastrointestinal Adenocarcinomas | NCT01284231 |

| I | BAY2010122 | Prostatic neoplasms | NCT01723475 |

| I | MT110 | Solid tumors | NCT00635596 |

| I | Blinatumomab | B-cell and Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma | NCT00538096 |

| I/II | Blinatumomab | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (child and adolescent) | NCT01471782 |

| I/II | Blinatumomab | Chronic lymphocytic Leukemia | NCT00676871 |

| II | Blinatumomab | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | NCT00560794 |

| II | Blinatumomab | Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma | NCT01741792 |

| II | Blinatumomab | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | NCT01466179 |

| II | Blinatumomab | Philadelphia Chromosome Negative and Positive Adult Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | NCT02143414 |

| II | Blinatumomab | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | NCT01207388 |

| II | Blinatumomab | B-ALL | NCT01209286 |

| II | Blinatumomab | Philadelphia Positive B-precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | NCT02000427 |

| III | Blinatumomab | Relapsed/Refractory B-precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | NCT02013167 |

| III | Blinatumomab | B-cell Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia; Philadelphia Chromosome-Negative Adult Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | NCT02003222 |

| III | Blinatumomab | B-cell Adult Lymphoblastic Leukemia; B-cell Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | NCT02101853 |

| Blinatumomab | Relapsed/Refractory B-Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | NCT02187354 |

Listing accurate as of July 31, 2014.

Major toxicities reported for blinatumomab thus far include seizures, cerebellar effects, lymphopenia, and leukopenia.28, 33 These effects were reversible upon drug discontinuation. Notably, cytokine release syndrome has been observed only in children treated with this BiTE.36, 42 In this case, the syndrome was dominated by IL-6 and remedied by administration of an IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilicumab.42 The side effects that may be specific to blinatumomab will become more evident as additional BiTEs are examined in the clinic.

MT-110

MT-110 is an anti-EpCAM x anti-CD3 BiTE also developed by Micromet. Targeting the epithelial marker EpCAM, MT-110 is aimed for solid malignancies of epithelial origin, including breast, colon, pancreatic, and ovarian tumors.22, 26, 27, 43 Several in vitro studies have indicated the efficacy of this molecule. An in vitro model of the human SW480 colon cancer cell line xenografted into non-obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice showed that MT110 was able to direct unstimulated human PBMCs to kill tumor cells, resulting in suppression of tumor growth.22 Similar findings were made using colorectal primary tumor initiating cells in NOD/SCID mice.26 An in vitro study using primary breast malignant pleural effusates, it was demonstrated that MT110 could direct autologous T cells within the effusates themselves to lyse malignant cells with high efficacy.43 More recently, MT110 has been reported to suppress the growth of primary pancreatic cancer cells and cancer cell lines in vitro.27 Complementing this preclinical data, a phase I clinical study is underway to assess safety and tolerability of MT110 in patients with solid malignancies.

MT-111

Targeting carcinoembrionic antigen (CEA), MT111 is the third BiTE to enter clinical trials. CEA is an immunoglobulin superfamily glycoprotein that is expressed on a variety of solid tumors44 and on various portions of the gastrointestinal tract, sweat glands, and prostate epithelium in adults.15 MT111 has been assessed preclinically in models of colon cancer.12, 15 In a SCID mouse model, administration of MT111 was able to suppress growth of a colon cancer cell line co-implanted with human T cells.15 Consistently, the BiTE was markedly cytotoxic to cells from colorectal cancer explants.12 A phase I clinical trial of MT111 against gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma is underway.

BAY2010112 (AMG112)

BAY2010112 is intended to treat prostate cancer. Its target, prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), is a membrane protein found in all prostate tissues.45 Pre-clinically, this BiTE has shown promising activity in vitro and in murine tumor systems. The molecule was able to induce specific lysis of a variety of human prostate cell lines with EC50s less than 5 ng/mL.25 Additionally, BAY2010112 suppressed formation of tumors from PSMA-positive human cell lines in mice.25 The molecule was also found to cross-react with PSMA from a non-human primate.25 A phase I trial of BAY2010112 is currently recruiting participants.

Preclinical BiTEs

To date, several BiTEs have been reported in the literature that have not yet progressed to clinical trials (Table 1). These molecules are targeted to a variety of antigens and malignancies. Notable among these molecules are BiTEs targeting receptor tyrosine kinases. BiTEs targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) were produced from the monoclonal antibodies cetuximab and panitumumab.16 These molecules were capable of eliminating colorectal cancer cells in vitro, and the cetuximab-based BiTE was found to be superior to cetuximab in a xenograft model, with the BiTE suppressing growth of two human colorectal tumor lines to a greater extent than cetuximab in a NOD/SCID mouse model.16 A BiTE targeting EphA2 also has been reported.38 This molecule promoted potent lysis of EphA2-positive SW480 colorectal cancer cells in vitro and suppressed growth of SW480 tumors in a NOD/SCID mouse model.38 In addition to the EGFR and EphA2 BiTEs, a BiTE targeting Her2 was generated by converting the monoclonal trastuzumab to the BiTE platform,46 but its characteristics have not yet been reported.

Several BiTEs under investigation target solid tumors, particularly prostate cancer and melanoma. The BiTE A300E is being studied for its effects in prostate cancer. The molecule targets a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17 (ADAM17), a protease required for activation of EGFR.39, 47 A300E has been shown to enhance specific lysis of ADAM17-positive cells by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro.39 A second prostate-focused BiTE targets prostate stem cell antigen (PSCA)., This BiTE dose-dependently promoted elimination of target-positive cell lines and has been found to suppress tumor growth in xenograft mouse models.24 Another BiTE targets melanoma. This BiTE recognizes melanoma-associated chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (MCSP). The MCSP-specific BiTE was found to redirect autologous T cells to lyse patient-derived melanoma cells.17

A novel molecule amongst the group is anti-CD3-NKG2D. This molecule has a non-traditional BiTE structure, in which the tumor-specific scFv has been replaced with the extracellular domain of the NK cell receptor NKG2D. This allows the BiTE to target not just a single tumor antigen but to target any of the eight know NKG2D ligands, markedly increasing its range of targeted tumors. In an in vivo model, scFv-NKG2D treatment improved survival of mice given ligand-positive RMA/RG lymphoma cells and obvious signs of toxicity were absent.48 The functionality of a receptor-based BiTE offers a way to increase the range of targeted antigens‥

Concluding Remarks

Immunotherapy is a rapidly growing field that has the potential to augment or replace traditional cancer therapies. Of the various immunotherapies, bispecific antibodies, and BiTEs in particular, have exceptional potential as cancer therapeutics. Comprised of a minimalist structure of two unique scFvs joined by a flexible linker, BiTEs are able to bind two unique antigens, with one commonly being CD3. By simultaneously binding to their specific antigens, BiTEs are able to bridge cytotoxic T cells with tumor cells, resulting in T cell activation and tumor cell lysis. Their requirement for dual antigen binding has proven effective at preventing undesired T cell activation while avoiding anergy. The efficiency and exceptional potency of these molecules has been demonstrated in both the basic laboratory and clinical settings.

At present, blinatumomab is the most advanced and is now entering phase III clinical trials for B cell-derived malignancies. Targeting solid tumors, MT110, MT111, and BAY2010112 have also entered phase I trials. In addition to these molecules, several other BiTEs are currently being developed pre-clinically, including molecules targeting prostate cancer, melanoma, and other solid tumors. Veering away from the traditional BiTE design, molecules like scFv-NKG2D explore the possibility of expanding BiTE specificity. It will be interesting to see how these forthcoming BiTEs will perform clinically.

There is much further knowledge to be gained as the field of BiTEs moves forward. Foremost, a great deal more clinical data needs to be collected to further characterize the effects of BiTEs in patients. At present, understanding of BiTE pharmacology in patients is based on studies with blinatumomab. Not until additional studies are done with other BiTEs will there be a better understanding of how BiTEs are processed by the body and of what toxicities may appear during BiTE therapy. In addition to learning more about BiTEs as single agents, it will be necessary to examine BiTEs in combination with other therapies. In particular, it will be interesting to see how BiTEs perform in association with immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as programmed cell death 1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 inhibitors, which allow for greater T cell activation. Such a combination could enhance BiTE efficacy by maintaining T cell activity within the tumor microenvironment. As with most new therapeutics, BiTEs will need to make a case for themselves as useful therapies. A variety of immunotherapies are being developed for the treatment of cancer, and it will be interesting to see how BiTEs sit apart from other new therapeutics and prove themselves uniquely clinically useful. In sum, BiTEs represent a promising platform for cancer therapy, and their further development may lead to highly efficacious therapies for cancer.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Elizabeth Flory for her assistance in collecting resource materials.

Financial Support

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health CA164178 and from the Immunology Training Program T32 A1007363.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Dr. Sentman and Dartmouth College have filed for patent protection for the scFv-NKG2D protein mentioned in this article.

References

- 1.Maus MV, Grupp SA, Porter DL, June CH. Antibody-modified T cells: CARs take the front seat for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2014;123:2625–2635. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-492231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chmielewski M, Hombach AA, Abken H. Antigen-Specific T-Cell Activation Independently of the MHC: Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Redirected T Cells. Front Immunol. 2013;4:371. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez P, Hoffman RW, Shaw S, Bluestone JA, Segal DM. Specific targeting of cytotoxic T cells by anti-T3 linked to anti-target cell antibody. Nature. 1985;316:354–356. doi: 10.1038/316354a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staerz UD, Kanagawa O, Bevan MJ. Hybrid antibodies can target sites for attack by T cells. Nature. 1985;314:628–631. doi: 10.1038/314628a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindhofer H, Hess J, Ruf P. Trifunctional Triomab Antibodies for Cancer Therapy. In: Kontermann RE, editor. Bispecific Antibodies. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindhofer H, Mocikat R, Steipe B, Thierfelder S. Preferential Species-Restricted Heavy/Light Chain Pairing in Rat/Mouse Quadromas Implications for a Single-Step Purification of Bispecific Antibodies. The Journal of Immunology. 1995;155:219–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiner GJ, Kostelny SA, Hillstrom JR, Cole MS, Link BK, Wang SL, et al. The role of T cell activation in anti-CD3 x antitumor bispecific antibody therapy. J Immunol. 1994;152:2385–2392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein JS, Gnanapragasam PNP, Galimidi RP, Foglesong CP, Anthony P, West J, Bjorkman PJ. Examination of the contributions of size and avidity to the neutralization mechanisms of the anti-HIV antibodies b12 and 4E10. PNAS. 2009;106:7385–7390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811427106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brischwein K, Parr L, Pflanz S, Volkland J, Lumsden J, Klinger M, et al. Strictly target cell-dependent activation of T cells by bispecific single-chain antibody constructs of the BiTE class. J Immunother. 2007;30:798–807. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318156750c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amann M, D'Argouges S, Lorenczewski G, Brischwein K, Kischel R, Lutterbuese R, et al. Antitumor activity of an EpCAM/CD3-bispecific BiTE antibody during long-term treatment of mice in the absence of T-cell anergy and sustained cytokine release. J Immunother. 2009;32:452–464. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181a1c097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Offner S, Hofmeister R, Romaniuk A, Kufer P, Baeuerle PA. Induction of regular cytolytic T cell synapses by bispecific single-chain antibody constructs on MHC class I-negative tumor cells. Mol Immunol. 2006;43:763–771. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osada T, Hsu D, Hammond S, Hobeika A, Devi G, Clay TM, et al. Metastatic colorectal cancer cells from patients previously treated with chemotherapy are sensitive to T-cell killing mediated by CEA/CD3-bispecific T-cell-engaging BiTE antibody. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:124–133. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loffler A, Kufer P, Lutterbuse R, Zettl F, Daniel PT, Schwenkenbecher JM, et al. A recombinant bispecific single-chain antibody, CD19 x CD3, induces rapid and high lymphoma-directed cytotoxicity by unstimulated T lymphocytes. Blood. 2000;95:2098–2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dreier T, Lorenczewski G, Brandl C, Hoffmann P, Syring U, Hanakam F, et al. Extremely potent, rapid and costimulation-independent cytotoxic T-cell response against lymphoma cells catalyzed by a single-chain bispecific antibody. Int J Cancer. 2002;100:690–697. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lutterbuese R, Raum T, Kischel R, Lutterbuese P, Schlereth B, Schaller E, et al. Potent control of tumor growth by CEA/CD3-bispecific single-chain antibody constructs that are not competitively inhibited by soluble CEA. J Immunother. 2009;32:341–352. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31819b7c70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lutterbuese R, Raum T, Kischel R, Hoffmann P, Mangold S, Rattel B, et al. T cell-engaging BiTE antibodies specific for EGFR potently eliminate KRAS- and BRAF-mutated colorectal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12605–12610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000976107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torisu-Itakura H, Schoellhammer HF, Sim MS, Irie RF, Hausmann S, Raum T, et al. Redirected lysis of human melanoma cells by a MCSP/CD3-bispecific BiTE antibody that engages patient-derived T cells. J Immunother. 2011;34:597–605. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3182307fd8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bohlen H, Manzke O, Patel B, Moldenhauer G, Dorken B, von Fliedner V, et al. Cytolysis of leukemic B-cells by T-cells activated via two bispecific antibodies. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4310–4314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manzke O, Titzer S, Tesch H, Diehl V, Bohlen H. CD3 x CD19 bispecific antibodies and CD28 costimulation for locoregional treatment of low-malignancy non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1997;45:198–202. doi: 10.1007/s002620050432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kipriyanov SM, Moldenhauer G, Schuhmacher J, Cochlovius B, Von der Lieth CW, Matys ER, et al. Bispecific tandem diabody for tumor therapy with improved antigen binding and pharmacokinetics. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:41–56. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann P, Hofmeister R, Brischwein K, Brandl C, Crommer S, Bargou R, et al. Serial killing of tumor cells by cytotoxic T cells redirected with a CD19-/CD3-bispecific single-chain antibody construct. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:98–104. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brischwein K, Schlereth B, Guller B, Steiger C, Wolf A, Lutterbuese R, et al. MT110: a novel bispecific single-chain antibody construct with high efficacy in eradicating established tumors. Mol Immunol. 2006;43:1129–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mack M, Riethmuller G, Kufer P. A small bispecific antibody construct expressed as a functional single-chain molecule with high tumor cell cytotoxicity. PNAS. 1995;92:7021–7025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feldmann A, Arndt C, Töpfer K, Stamova S, Krone F, Cartellieri M, et al. Novel Humanized and Highly Efficient Bispecific Antibodies Mediate Killing of Prostate Stem Cell Antigen-Expressing Tumor Cells by CD8+ and CD4+ T Cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2012;189:3249–3259. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedrich M, Raum T, Lutterbuese R, Voelkel M, Deegen P, Rau D, et al. Regression of Human Prostate Cancer Xenografts in Mice by AMG 212/BAY2010112, a Novel PSMA/CD3-Bispecific BiTE Antibody Cross-Reactive with Non-Human Primate Antigens. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2012;11:2664–2673. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrmann I, Baeuerle PA, Friedrich M, Murr A, Filusch S, Ruttinger D, et al. Highly Efficient Elimination of Colorectal Tumor-Initiating Cells by an EpCAM/CD3-Bispecific Antibody Engaging Human T Cells. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cioffi M, Dorado J, Baeuerle PA, Heeschen C. EpCAM/CD3-Bispecific T-cell engaging antibody MT110 eliminates primary human pancreatic cancer stem cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:465–474. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bargou R, Leo E, Zugmaier G, Klinger M, Goebeler M, Knop S, et al. Tumor regression in cancer patients by very low doses of a T cell-engaging antibody. Science. 2008;321:974–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1158545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brambell FWR, Hemmings WA, Morris IG. A Theoretical Model of γ-Globulin Catabolism. Nature. 1964;203:1352–1355. doi: 10.1038/2031352a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weir ANC, Nesbitt A, Chapman AP, Popplewell AG, Antoniw P, Lawson ADG. Formatting antibody fragments to mediate specific therapeutic functions. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2002;30:512–516. doi: 10.1042/bst0300512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schlereth B, Quadt C, Dreier T, Kufer P, Lorenczewski G, Prang N, et al. T-cell activation and B-cell depletion in chimpanzees treated with a bispecific anti-CD19/anti-CD3 single-chain antibody construct. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:503–514. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0001-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klinger M, Brandl C, Zugmaier G, Hijazi Y, Bargou RC, Topp MS, et al. Immunopharmacologic response of patients with B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia to continuous infusion of T cell-engaging CD19/CD3-bispecific BiTE antibody blinatumomab. Blood. 2012;119:6226–6233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-400515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Topp MS, Kufer P, Gokbuget N, Goebeler M, Klinger M, Neumann S, et al. Targeted therapy with the T-cell-engaging antibody blinatumomab of chemotherapy-refractory minimal residual disease in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients results in high response rate and prolonged leukemia-free survival. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2493–2498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baeuerle PA, Reinhardt C. Bispecific T-Cell Engaging Antibodies for Cancer Therapy. Cancer Research. 2009;69:4941–4944. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chames P, Baty D. Bispecific antibodies for cancer therapy: The light at the end of the tunnel? mAbs. 2009;1:539–547. doi: 10.4161/mabs.1.6.10015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schlegel P, Lang P, Zugmaier G, Ebinger M, Kreyenberg H, Witte KE, et al. Pediatric posttransplant relapsed/refractory B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia shows durable remission by therapy with the T-cell engaging bispecific antibody blinatumomab. Haematologica. 2014;99:1212–1219. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.100073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kufer P, Mack M, Gruber R, Lutterbuse R, Zettl F, Riethmuller G. Construction and biological activity of a recombinant bispecific single-chain antibody designed for therapy of minimal residual colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1997;45:193–197. doi: 10.1007/s002620050431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hammond SA, Lutterbuese R, Roff S, Lutterbuese P, Schlereth B, Bruckheimer E, et al. Selective Targeting and Potent Control of Tumor Growth Using an EphA2/CD3-Bispecific Single-Chain Antibody Construct. Cancer Research. 2007;67:3927–3935. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto K, Trad A, Baumgart A, Huske L, Lorenzen I, Chalaris A, et al. A novel bispecific single-chain antibody for ADAM17 and CD3 induces T-cell-mediated lysis of prostate cancer cells. Biochem J. 2012;445:135–144. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loffler A, Gruen M, Wuchter C, Schriever F, Kufer P, Dreier T, et al. Efficient elimination of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia B cells by autologous T cells with a bispecific anti-CD19/anti-CD3 single-chain antibody construct. Leukemia. 2003;17:900–909. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Topp MS, Gokbuget N, Zugmaier G, Degenhard E, Goebeler ME, Klinger M, et al. Long-term follow-up of hematologic relapse-free survival in a phase 2 study of blinatumomab in patients with MRD in B-lineage ALL. Blood. 2012;120:5185–5187. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-441030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teachey DT, Rheingold SR, Maude SL, Zugmaier G, Barrett DM, Seif AE, et al. Cytokine release syndrome after blinatumomab treatment related to abnormal macrophage activation and ameliorated with cytokine-directed therapy. Blood. 2013;121:5154–5157. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-485623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witthauer J, Schlereth B, Brischwein K, Winter H, Funke I, Jauch KW, et al. Lysis of cancer cells by autologous T cells in breast cancer pleural effusates treated with anti-EpCAM BiTE antibody MT110. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117:471–481. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hammarstrom S. The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) family: structures, suggested functions and expression in normal and malignant tissues. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 1999;9:67–81. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1998.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang SS. Overview of Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen. Reviews in Urology. 2004;6:S13–SS8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lutterbuese R, Wissing S, Amann M, Baeuerle P, Kufer P, editors. Conversion of Cetuximab and Trastuzumab into T cell-engaging BiTE antibodies creates novel drug candidates with superior anti-tumor activity. 99th AACR Annual Meeting; San Diego, CA. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodland KD, Bollinger N, Ippolito D, Opresko LK, Coffey RJ, Zangar R, et al. Multiple mechanisms are responsible for transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor in mammary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31477–31487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800456200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang T, Sentman CL. Cancer immunotherapy using a bi-specific NK receptor- fusion protein that engages both T cells and tumor cells. Cancer Research. 2011;71:2066–2076. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laszlo GS, Gudgeon CJ, Harrington KH, Dell'Aringa J, Newhall KJ, Means GD, et al. Cellular determinants for preclinical activity of a novel CD33/CD3 bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE) antibody, AMG 330, against human AML. Blood. 2014;123:554–561. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-527044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friedrich M, Henn A, Raum T, Bajtus M, Matthes K, Hendrich L, et al. Preclinical characterization of AMG 330, a CD3/CD33-bispecific T-cell-engaging antibody with potential for treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:1549–1557. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]