Abstract

Background

Geriatric syndromes such as falls, frailty, and functional impairment are multifactorial conditions used to identify vulnerable older adults. Limited data exists on these conditions in older HIV-infected adults and no studies have comprehensively examined these conditions.

Methods

Geriatric syndromes including falls, urinary incontinence, functional impairment, frailty, sensory impairment, depression and cognitive impairment were measured in a cross-sectional study of HIV-infected adults age 50 and older who had an undetectable viral load on antiretroviral therapy (ART). We examined both HIV and non-HIV related predictors of geriatric syndromes including sociodemographics, number of co-morbidities and non-antiretroviral medications, and HIV specific variables in multivariate analyses.

Results

We studied 155 participants with a median age of 57 (IQR 54-62); (94%) were men. Pre-frailty (56%), difficulty with instrumental activities of daily living (46%), and cognitive impairment (47%) were the most frequent geriatric syndromes. Lower CD4 nadir (IRR 1.16, 95% CI 1.06-1.26), non-white race (IRR 1.38, 95% CI 1.10-1.74), and increasing number of comorbidities (IRR 1.09, 95%CI 1.03-1.15) were associated with increased risk of having more geriatric syndromes.

Conclusions

Geriatric syndromes are common in older HIV infected adults. Treatment of comorbidities and early initiation of ART may help to prevent development of these age related complications. Clinical care of older HIV-infected adults should consider incorporation of geriatric principles.

Keywords: Aging, Frailty, Function

Introduction

With modern antiretroviral drug regimens, HIV-infected adults are living longer and HIV has transformed into a chronic illness. 1 Therapy does not fully restore health, however, as HIV-infected adults with well controlled HIV have excess risk for a number of co-morbidities such as cardiovascular and bone disease,2,3 along with resultant multimorbidity and polypharmacy.4-7 In the general population of HIV-uninfected older adults facing multimorbidity, comprehensive geriatric assessment including assessment of geriatric syndromes is used to identify the most vulnerable older adults.

Geriatric syndromes are defined as multifactorial conditions that result from deficits in multiple domains including clinical, psychosocial and environmental vulnerabilities. 8,9 Geriatric syndromes are a fundamental construct in gerontology that provide evidence of aging and predict clinically important outcomes such as healthcare utilization and mortality.10,11 Given the multiple organ derangements and complicated social and environmental factors associated with HIV infection and its treatment, it is reasonable to hypothesize that geriatric syndromes may be common in HIV-infected adults even at relatively younger ages than those traditionally considered to be geriatric. Supporting this hypothesis, geriatric syndromes are described at relatively younger ages in adults living with chronic conditions such as diabetes or facing psychosocial challenges such as homelessness.12, 13 Studies have also suggested that risk factors for the development of geriatric syndromes in more middle aged adults overlap with risk factors for adults 65 and older.14,15 Limited data exists on the association of geriatric syndromes at younger ages with outcomes such as health care utilization16 but studies in HIV-infected adults have shown that syndromes such as frailty even in younger ages can independently predict mortality suggesting that geriatric syndromes are an important construct to examine.17,18 Prior studies in older HIV-infected adults have primarily focused on frailty17,19 and no comprehensive assessment of geriatric syndromes in older HIV adults has been reported. The purpose of this study was to describe the frequencies of geriatric syndromes in HIV-infected adults age 50 and older with virologic control (undetectable viral load for at least three years) and to explore factors associated with the presence of geriatric syndromes.

Methods

Participants

All participants were enrollees in the University of California San Francisco SCOPE cohort, a study of HIV-infected adults age 18 and over. SCOPE participants were primarily recruited from the San Francisco General Hospital HIV clinic, a safety-net clinic, and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center Infectious Diseases Clinic. To be included in this study, SCOPE participants had to be age 50 or older, have an undetectable plasma viral load (HIV RNA <40 copies/mL) for at least three years prior to enrollment, and be taking antiretroviral therapy. We chose age fifty as a cut-off for this study as this is the most commonly employed definition of “older” in the current HIV literature. The criterion of an undetectable viral load for three years has been used in prior SCOPE translational studies. We recruited participants through fliers provided at the time of routine SCOPE appointments and by SCOPE staff referrals, creating a consecutive sample of the overall SCOPE cohort. If a potential enrollee agreed to participate, additional consent was then obtained for participation in a one hour geriatric visit. Participants received $20 payment for participation, consistent with general SCOPE visit payment policies. The University of California San Francisco and the San Francisco VA Medical Center committees on human research approved this study.

Data Collection

We collected data using questionnaires and brief physical assessments during the one hour geriatric study visit and also utilized existing data from SCOPE questionnaires collected during routine SCOPE visits. Specifically, demographic data, HIV history (including estimated duration of infection and HIV transmission risk), substance abuse history and antiretroviral medication history were extracted from existing SCOPE data. We also extracted participant self-report of antiretroviral exposure prior to study enrollment which is collected at the baseline SCOPE visit. Medical records are requested and chart review performed where possible to verify the self-report of pre-enrollment antiretroviral medications. All participants completed a general SCOPE visit including CD4 and viral load laboratory measurements (Abbott Real Time HIV-1 Viral load Assay) within one month of the geriatric visit. During the geriatrics study visit, co-morbid conditions and non-antiretroviral medications were measured by self-report. Co-morbid conditions assessed included comorbidities from the Charlson comorbidity index20 as well as more HIV-specific conditions such as Hepatitis C infection and peripheral neuropathy. Non-antiretroviral medications included all prescription, over the counter and herbal medications. We verified self-report of co-morbid conditions and non-antiretroviral medications by medical record review for participants who receive primary care from UCSF affiliated clinical sites.

Geriatric Syndromes

The geriatric syndromes assessed included falls, urinary incontinence, functional and mobility impairment, sensory impairment, depression, cognitive impairment, and frailty. These syndromes and measurements were chosen after a literature review which examined geriatric syndromes included in national cohort studies, syndromes described in HIV-infected adults, and syndromes relevant to an outpatient setting.19,21-24 We measured falls by self-report to the question “Have you fallen in the past year? – A fall can include a slip or trip in which you lost your balance and landed on the floor or ground or lower level?” This measurement was based on the Prevention of Falls Network Europe (ProFaNE) definition which defines falls as “an unexpected event in which the participants come to rest on the ground, floor, or lower level.” 25,26 We measured urinary incontinence using the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ) which is scored from 0-21 with higher scores indicating greater severity of incontinence and the presence of urinary incontinence defined as a score ≥1.27 The ICIQ was chosen as it is validated in men and women and had been utilized in another study of geriatric syndromes in a more middle aged population. 13 Our measure of functional impairment was self-report of six activities of daily living (ADLs) including bathing and dressing and nine instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) including medication management and housework. ADLs and IADLs were assessed in a two part question: “Do you have any difficulty with (each activity)?” and “If yes, do you need the help of another person to (perform each activity)?” Mobility was also assessed as a two part question about ability to walk “a quarter mile or 2-3 blocks.” The two part questions allowed us to examine categories of independence (no difficulty), difficulty, and dependence (need help) with ADLs, IADLS and mobility. Asking specifically about “difficulty with” is employed in other large cohort studies and allows for earlier detection of disability (i.e. detecting difficulty prior to full dependence) which may be more amenable to intervention.21,28 We measured hearing impairment by self-report of hearing loss and by abnormal Whispered Voice Test, with inability to identify more than half of whispered stimuli in either ear on the Whispered Voice Test used to define hearing impairment.29,30 Similarly, we measured visual impairment by both self-report of difficulty seeing even while wearing corrective lenses and by objective measurement of visual acuity using a Snellen chart.31 Visual impairment was defined as vision of 20/40 or worse on Snellen acuity testing. For both measures of sensory impairment, frequencies using the objective testing criteria alone were compared to a definition of sensory impairment including either self-report of sensory impairment or an abnormal objective test, which has been utilized in other studies.13

We measured depression using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) with cut-off scores of 16-26 for mild-moderate depression and scores of ≥27 for severe depression.32 The CES-D was chosen because it has been utilized in other studies of HIV-infected adults and is also a component of the Fried frailty measure.17,33,34 Cognitive impairment was measured using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA).35 MOCA scores range from 0-30 with a score of <26 often used as a cut-off for impairment. An additional point is added to the total score for participants with less than high school education. The MOCA has been proposed as a useful test given the inclusion of both sub-cortical and cortical domains which are affected in HIV Associated Neurocognitive Disorders (HAND) and neurodegenerative processes such as Alzheimer's disease, respectively.36 The MOCA was recently validated in a HIV-infected cohort of adults age 60 and older in San Francisco and the traditional MOCA cut-point of <26 was found to be the optimal cut-point for HAND.37 To define frailty and pre-frailty, we used the Fried criteria which includes unintentional weight loss, self-report of exhaustion (using 2 items from the CES-D), low physical activity (using the Minnesota Leisure Time activity questionnaire), slow walking speed, and weakness (measured by hand grip strength).33,38 Participants were classified as frail if they met 3 or more of the 5 criteria and were classified as pre-frail if they met 1 or 2 of the criteria. While several different definitions of frailty exist, the Fried frailty measure has been used in large cohort studies of HIV-infected adults and in other studies of frailty in relatively younger adults.13,17,19,39

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to examine participant characteristics and frequencies of geriatric conditions. To determine frequencies of geriatric syndromes we generated dichotomous variables for each syndrome. Functional impairment was dichotomized to report of at least difficulty with one or more ADLs and one or more IADLs. Cognitive impairment was dichotomized based on the traditional cut-off MOCA score of <26 and depression was dichotomized to a score of ≥16. Additionally, we used descriptive statistics to describe the number of falls, total scores on ICIQ for urinary incontinence, and total MOCA scores.

As individual geriatric syndromes may share similar risk factors,8,40 we examined factors associated with geriatric syndromes as a composite outcome of increasing number of geriatric syndromes. We first focused on measures that are most consistently described as syndromes: falls, urinary incontinence, functional impairment and frailty. To assess the association between potential risk factors and counts of these geriatric syndromes, we utilized multivariate Poisson models to account for the distribution of the count data. We included demographic, HIV and general health variables hypothesized a priori as being predictive for geriatric syndromes based on literature review. Tests for colinearity of all predictor variables were performed. Counts of geriatric syndromes have been described before,14,21 but to confirm our findings we also examined the geriatric syndrome outcome as a dichotomous outcome of presence of 2 or more syndromes and as an ordinal logistic model which has been used before to analyze numbers of geriatric syndromes.14 We also examined counts of all ten syndromes in a multivariate Poisson model. All statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.3 and STATA version 12.

Results

Participants

179 SCOPE participants were approached for participation and 156 enrolled in this study. We excluded one participant from analysis when it was revealed during his study visit that he had recently stopped his antiretroviral medications. The final 155 participants were primarily male (n=145, 93.6%), Caucasian (98, 63.2%) and had a median age of 57 (IQR 54-62) (Table 1). Most acquired HIV through MSM contact (124, 80.0%). Participants reported being infected with HIV for a median of 21 years (IQR 16-24, range 4-32 years) and had a median CD4 T-lymphocyte count of 537 (IQR 398-752) cells/mm3. Participants had a median of 4 (IQR 3-6) comorbidities and were taking a median of 9 (6-12) non-antiretroviral medications. Common co-morbidities were hyperlipidemia (97, 62.6%), hypertension (78, 50.3%), and peripheral neuropathy (62, 40.0%). Of the 24 participants who were approached but did not participate in this study, there were no statistically significant differences in demographic variables (age, gender, ethnicity, education, HIV transmission) compared to those who enrolled, except for CD4 T-lymphocyte count (mean 461.9 cells/mm3 vs. 585.6 cells/mm3 in enrolled, p =0.02).

Table 1. Characteristics of Study Participants.

| Characteristic | N (%) or Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

| N=155 | ||

|

| ||

| Age | 57 (IQR 54-62) | |

|

| ||

| Age (quartiles) | 50-54 | 40 (25.8) |

| 55-59 | 61 (39.4) | |

| 60-64 | 24 (15.5) | |

| 65+ | 30 (19.4) | |

|

| ||

| Male | 145 (93.6) | |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 98 (63.2) | |

| African American | 28 (18.1) | |

| Other | 29 (18.7) | |

|

| ||

| Educationa | ||

| High School or Less | 32 (20.7) | |

| Some College | 64 (41.3) | |

| College Degree/ Any Graduate | 59 (38.1) | |

|

| ||

| Employed in past year | 47 (33.8) | |

|

| ||

| Annual Income | ||

| ≥24,000 | 36 (29.3) | |

| 12,00-24,000 | 39(31.7) | |

| ≤12,000 | 48 (39.0) | |

|

| ||

| HIV transmissionb | ||

| MSM | 124 (80.0) | |

| Heterosexual | 23(14.8) | |

| IVDU | 18(11.6) | |

| Other | 13(8.4) | |

|

| ||

| Length of HIV infection (years) | 21 (16-24) | |

|

| ||

| CD4 count cells/mm3) | 567 (398-752) | |

|

| ||

| CD4 nadirc (cells/mm3) | 174 (51-327) | |

|

| ||

| Exposure to DDI/DDC/D4T/AZTd | 115 (74.2) | |

|

| ||

| Number of comorbidities | 4 (3-6) | |

|

| ||

| Number of non-antiretroviral medications | 9 (6-12) | |

|

| ||

| Current Smokere | 35 (22.6) | |

|

| ||

| Alcohol Usee | 96 (62.8) | |

|

| ||

| IVDUe | 7 (4.5) | |

Education measured at enrollment visit,

Participants could report more than one mode of transmission, percentages do not sum to 100%,

based on self-report,

DDI=didanosine, D4T=stavudine, DDC=zalcitabine, AZT=zidovudine,

in last 4 months

Geriatric Syndromes

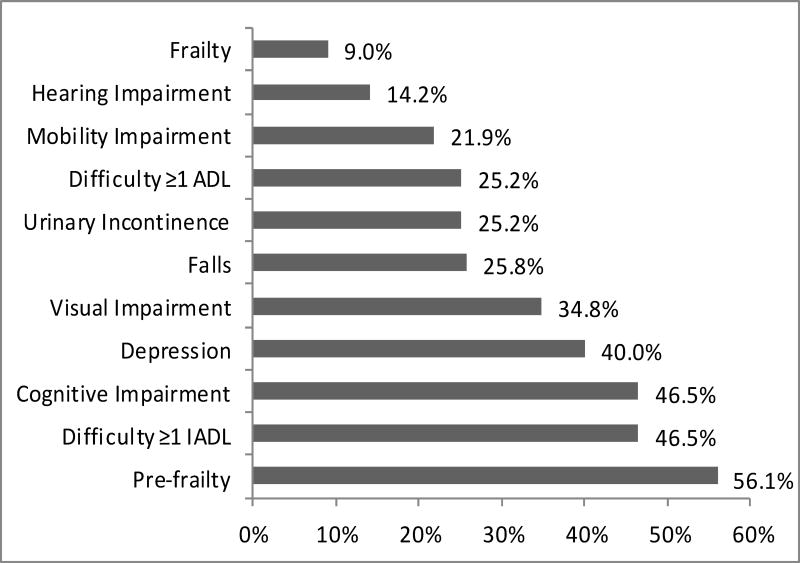

83 participants (53.6%) had two or more geriatric syndromes. Figure 1 shows the frequencies of individual syndromes. The most frequent conditions were pre-frailty (n=87, 56.1%), difficulty with one or more IADLs (72, 46.5%), and cognitive impairment (72, 46.5%). Pre-frailty (1 or 2 of the Fried criteria) was found in 56.1% of participants and was more common than frailty (3 or more Fried criteria) which was only seen in 9.0% of participants. 25.8% of participants reported at least one fall in the past year. Among participants who reported falls, the median number of falls was 2 (IQR 1-4) and 12.5% reported an injurious fall that required seeking medical attention. Among the 25.2% reporting urinary incontinence, the median score on the ICIQ was 6 (IQR 4-8). With regards to functional impairment, 39 (25.2%) participants reported difficulty with one or more ADLs, and 15 (10%) reported dependence. 46.5% of participants reported difficulty with one or more IADLS and 46 (29.6%) reported dependence in one or more IADLs. Of those who reported functional impairment, the median number of ADL difficulties was 1 (IQR 1-2) and the most frequent ADL impairments were transfers (15.5%), walking across a room (8.4%) and dressing (8.4%). The median number of IADL difficulties was 2 (IQR 1-3) with heavy housework (33.5%), light housework (12.9 %), and shopping (11.0%) the most frequently reported. When the definitions for hearing impairment and visual impairment were expanded from an abnormal test result to include either self-report or an abnormal test result, the frequencies increased from 14.2% to 41.3% for hearing impairment and 34.8% to 49.7% for visual impairment. Figure 1 shows participants with at least mild depressive symptoms (scores of 16 or higher on the CES-D), of which 33 (21.6%) had mild depressive symptoms (score 16-26) and 28 (18.3%) had moderate-severe depressive symptoms (score 27 or higher). The median MOCA score was 26 (IQR 22-28).

Figure 1. Frequencies of Geriatric Syndromes.

Each bar reflects the percentage of participants with each geriatric syndrome. Actual percentages are shown at the end of each bar. Horizontal axis only shown to 60%. ADL= Activities of Daily Living, IADL= Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

Factors Associated with Geriatric Syndromes

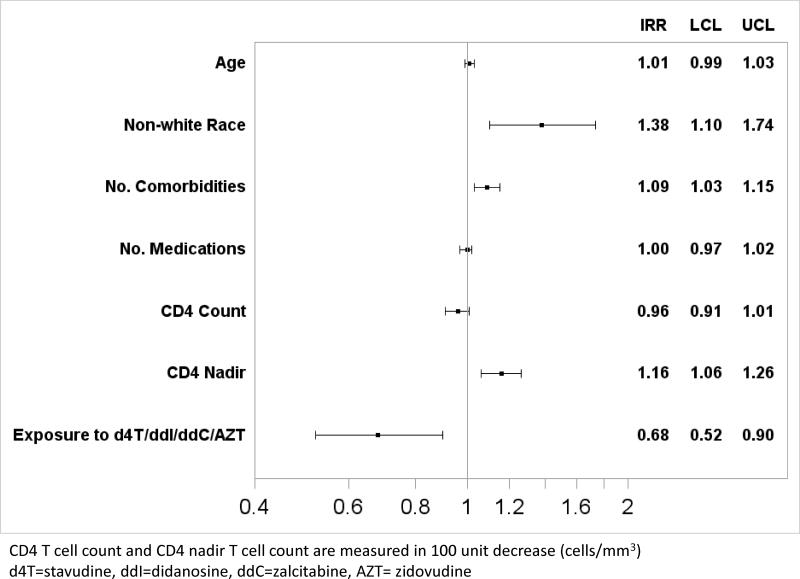

In the multivariate analysis of the composite outcome of five geriatric syndromes (falls, urinary incontinence, frailty, difficulty with ADLs, difficulty with IADLs), non-white race (IRR 1.38, 95% CI 1.10-1.74), increasing number of comorbidities (IRR 1.09 per condition, 95% CI 1.03-1.15), and lower CD4 nadir (100 unit decrease in CD4 nadir) (IRR 1.16, 95% CI 1.06-1.26) were associated with increased risk of having more geriatric syndromes. Exposure to the nucleoside agents stavudine, didanosine, zalcitabine, or zidovudine (d4T/DDI/DDC/AZT) was associated with a decreased risk of having more geriatric syndromes (IRR 0.68, 95% CI 0.52-0.90). These results are summarized in Figure 2 and comparative models confirming our findings are shown in the Supplemental Materials. We also constructed a multivariate model examining all ten geriatric syndromes, and found the same statistically significant associations with non-white race, increasing number of comorbidities, lower CD4 nadir and exposure to early nucleoside agents.

Figure 2. Demographic and Clinical Factors Associated with Increasing Numbers of Geriatric Syndromes.

Vertical axis shows each variable in the multivariate Poisson model. Horizontal bars reflect the Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR) with 95% Confidence Interval which are also listed on the right hand side of the figure (IRR, upper (UCL) and lower (LCL) 95% confidence intervals).

Discussion

The development of geriatric syndromes, multifactorial health conditions that impact morbidity, mortality and utilization of services, is one of the fundamental clinical manifestations of aging. A combination of risk factors for geriatric syndromes including psychosocial factors, such as social isolation and substance use, multimorbidity and polypharmacy as well as chronic inflammation, are common among older HIV-infected adults,41-44 which has raised concern about how to decrease age related complications in this population.5 Based on these concerns, and findings from other studies identifying increased risk for frailty17,19 we undertook a comprehensive study of geriatric syndromes in middle-aged and older antiretroviral-treated adults. As hypothesized, we identified a frequent occurrence of geriatric syndromes, with pre-frailty, difficulty with IADLs, and cognitive impairment particularly common even amongst participants with well controlled HIV. A combination of both HIV -related factors (CD4 nadir) and non HIV-related factors (comorbidities, non-white race) were associated with increased risk of having more geriatric syndromes.

Our study supports findings from other HIV cohorts that have found evidence of clinical aging in adults who were younger than the typical “geriatric” population (65 and older) and adds to the understanding of other less frequently studied syndromes in this population. As reported in cohort studies such as MACS, WIHS, and ALIVE we found that HIV-infected adults have evidence of frailty even in middle age.17,19,39 Consistent with findings from the Research on Older Adults with HIV study (ROAH), we found that depression was common in older HIV-infected adults.45 We also identified a high frequency of cognitive impairment that is similar to that reported in other studies among antiretroviral treated adults.46,47

With regards to less commonly examined syndromes, we found that falls were present in one quarter of participants, supporting data from a published study of falls in older HIV-infected adults which showed a 30% fall rate.23 We are unaware of other studies examining urinary incontinence in HIV-infected adults and we found that 25% of participants reported incontinence. The high frequency of urinary incontinence may seem surprising, although it is known that patients frequently do not report incontinence unless asked, and the ICIQ scores suggest that the majority of participants are experiencing only mild symptoms. We did find a history of benign prostatic hypertrophy was associated with reporting urinary incontinence, consistent with a prior study showing that HIV-infected men experience more lower urinary tract symptoms compared to HIV-uninfected men.48

In comparison, reported rates of falls and incontinence from the general population of community dwelling adults age 65 and older are 30% and 22% (for older men) respectively. 49,50 Estimates of frailty depend on the definition, but using the Fried phenotype definition, estimates range from 7% (original Fried article) to 10-14%.33,51,52 These data suggest that HIV-infected adults may experience similar rates of geriatric syndromes at relatively younger ages and emphasizes the critical need for appropriate HIV-negative comparison groups to put these findings into further context.

In our examination of factors contributing to geriatric syndromes, both HIV-related factors and non-HIV-related factors were associated with geriatric syndromes, which is consistent with the known multifactorial etiology of geriatric syndromes. Also importantly, the association with comorbidities and lower CD4 nadir suggest possible targets of intervention. Our results are consistent with a study of HIV status, age and daily function which also demonstrated an association of CD4 nadir and comorbidities with functional impairment.53 Prior studies have shown that advanced HIV disease increases the odds of syndromes such as frailty17,39 and the fact that we did not see an association with current CD4 count may be reflective of our study sample having well controlled HIV. Although we did not see an association with polypharmacy and geriatric syndromes, given the high prevalence of polypharmacy in this population, this likely remains an important target of intervention for the aging population.6,7,54 Similarly, we did not have information about psychosocial risk factors such as social isolation, but this remains another area for which interventions are needed. 34

We unexpectedly found that exposure to didanosine, stavudine, zalcitabine, or AZT was associated with a decreased risk of geriatric syndromes since we had hypothesized that exposure to these medications would increase the risk either through direct toxicity or mediation by contributing to comorbidities. This finding may be explained by the fact that those who received early antiretroviral therapy and survived may be more resilient and have other healthy lifestyle factors that could minimize risk of developing age related complications. Similarly, it is also possible that CD4 nadir may be more important for long term survivors of HIV/AIDS, and may not be as important for future aging populations who could have earlier access to treatment.

There are several limitations to our study. First, our study population was predominately men who have sex with men (MSM) who have been infected with HIV for a median of 21 years indicating these are patients who have aged (and survived) with HIV. Our findings may not extend to women or adults who have been infected for a shorter period of time, especially as we did see evidence of a possible survivorship effect in part of our analysis. Patients who are chronically infected may have different health issues than older adults who are more recently infected. While steps are taken to minimize recall bias of pre-enrollment antiretroviral exposure, recall bias remains a possibility. However, our findings including frequencies of falls and other syndromes are consistent with other studies. 23 We recruited a consecutive sample of SCOPE participants, however no statistically significant differences between the demographics of our participants and the demographics of all SCOPE participants age 50 or older were found. This is also a cross-sectional study and we cannot make any statements about causality of geriatric syndromes.

Our findings suggest that even in middle aged HIV-infected adults with well controlled HIV, the burden of geriatric syndromes is important and will need to be addressed clinically to minimize age related complications for this population. The association with lower CD4 nadir suggests that earlier antiretroviral treatment initiation may help to prevent aging related complications and the association with increasing number of comorbidities suggests that treatment and prevention of other comorbid conditions is equally important to management of HIV in the aging HIV population. Consideration of how to incorporate assessment of geriatric syndromes into HIV care and development of targeted interventions for risk factors of geriatric syndromes is needed as the HIV-infected population continues to age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the SCOPE study participants and SCOPE staff. We would also like to thank Monica Mattes, BS, University of Central Florida College of Medicine for her assistance at the Veterans Affairs site and Melissa T. Assenzio, MPH, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, UCSF for her assistance with SCOPE data queries.

Source of Funding: This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, University of California, San Francisco-Gladstone Institute of Virology & Immunology Center for AIDS Research, P30-AI027763, the S.D Bechtel Jr. Foundation Program for the Aging Century, NIAID (K24AI069994), the UCSF Clinical and Translational Research Institute Clinical Research Center (UL1 RR024131), and the CFAR Network of Integrated Systems (R24 AI067039).

Footnotes

This paper was presented in poster format and in a themed discussion session at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) in Boston, MA on March 5, 2014 and as an encore oral presentation at the American Geriatrics Society national meeting in Orlando, FL on May 16, 2014.

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Greene receives salary support from the National Institutes of Health (5-T32-AG000212). Drs. Deeks, Martin and Covinsky each currently hold grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Valcour currently holds grants from the National Institutes of Health, and has served as a consultant and paid lecturer for IAS-USA. For the remaining authors no conflicts of interest were declared.

References

- 1.Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. The Lancet. 2013;382(9903):1525–1533. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61809-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA internal medicine. 2013 Apr 22;173(8):614–622. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown TT, Qaqish RB. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis: a meta-analytic review. AIDS (London, England) 2006 Nov 14;20(17):2165–2174. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801022eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salter ML, Lau B, Go VF, Mehta SH, Kirk GD. HIV infection, immune suppression, and uncontrolled viremia are associated with increased multimorbidity among aging injection drug users. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America Dec. 2011;53(12):1256–1264. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greene M, Justice AC, Lampiris HW, Valcour V. Management of human immunodeficiency virus infection in advanced age. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013 Apr 3;309(13):1397–1405. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene M, Steinman MA, McNicholl IR, Valcour V. Polypharmacy, drug-drug interactions, and potentially inappropriate medications in older adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014 Mar;62(3):447–453. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edelman EJ, Gordon KS, Glover J, McNicholl IR, Fiellin DA, Justice AC. The next therapeutic challenge in HIV: polypharmacy. Drugs & aging. 2013 Aug;30(8):613–628. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0093-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007 May;55(5):780–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flacker JM. What is a geriatric syndrome anyway? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003 Apr;51(4):574–576. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kane RL, Talley KMC, Shamliyan T, Pacala JT. Common Syndromes in Older Adults Related to Primary and Secondary Prevention. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2011. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang SY, Shamliyan TA, Talley KM, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Not just specific diseases: systematic review of the association of geriatric syndromes with hospitalization or nursing home admission. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics. 2013 Jul-Aug;57(1):16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cigolle CT, Lee PG, Langa KM, Lee YY, Tian Z, Blaum CS. Geriatric conditions develop in middle-aged adults with diabetes. Journal of general internal medicine. 2011 Mar;26(3):272–279. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1510-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown RT, Kiely DK, Bharel M, Mitchell SL. Geriatric syndromes in older homeless adults. Journal of general internal medicine. 2012 Jan;27(1):16–22. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1848-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown RT, Kiely DK, Bharel M, Mitchell SL. Factors associated with geriatric syndromes in older homeless adults. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2013 May;24(2):456–468. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardener EA, Huppert FA, Guralnik JM, Melzer D. Middle-aged and mobility-limited: prevalence of disability and symptom attributions in a national survey. Journal of general internal medicine. 2006 Oct;21(10):1091–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown RT, Kiely DK, Bharel M, Grande LJ, Mitchell SL. Use of acute care services among older homeless adults. JAMA internal medicine. 2013 Oct 28;173(19):1831–1834. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piggott DA, Muzaale AD, Mehta SH, et al. Frailty, HIV infection, and mortality in an aging cohort of injection drug users. PloS one. 2013;8(1):e54910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desquilbet L, Jacobson LP, Fried LP, et al. A frailty-related phenotype before HAART initiation as an independent risk factor for AIDS or death after HAART among HIV-infected men. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2011 Sep;66(9):1030–1038. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desquilbet L, Jacobson LP, Fried LP, et al. HIV-1 infection is associated with an earlier occurrence of a phenotype related to frailty. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2007 Nov;62(11):1279–1286. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.11.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of chronic diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cigolle CT, Langa KM, Kabeto MU, Tian Z, Blaum CS. Geriatric conditions and disability: the Health and Retirement Study. Annals of internal medicine. 2007 Aug 7;147(3):156–164. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-3-200708070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huisingh-Scheetz M, Kocherginsky M, Schumm PL, et al. Geriatric Syndromes and Functional Status in NSHAP: Rationale, Measurement, and Preliminary Findings. The journals of gerontology Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2014 Nov;69(Suppl 2):S177–190. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erlandson KM, Allshouse AA, Jankowski CM, et al. Risk factors for falls in HIV-infected persons. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2012 Dec 1;61(4):484–489. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182716e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erlandson KM, Allshouse AA, Jankowski CM, et al. Association of functional impairment with inflammation and immune activation in HIV type 1-infected adults receiving effective antiretroviral therapy. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2013 Jul 15;208(2):249–259. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamb SE, Jorstad-Stein EC, Hauer K, Becker C Prevention of Falls Network E, Outcomes Consensus G. Development of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: the Prevention of Falls Network Europe consensus. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005 Sep;53(9):1618–1622. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hauer K, Lamb SE, Jorstad EC, Todd C, Becker C Group P. Systematic review of definitions and methods of measuring falls in randomised controlled fall prevention trials. Age and ageing. 2006 Jan;35(1):5–10. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, Shaw C, Gotoh M, Abrams P. ICIQ: a brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2004;23(4):322–330. doi: 10.1002/nau.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Health Interview Survey. [Accessed November 14, 2014]; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm.

- 29.Bagai A, Thavendiranathan P, Detsky AS. Does this patient have hearing impairment? JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2006 Jan 25;295(4):416–428. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pacala JT, Yueh B. Hearing deficits in the older patient: “I didn't notice anything”. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012 Mar 21;307(11):1185–1194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chou R, Dana T, Bougatsos C. Screening older adults for impaired visual acuity: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of internal medicine. 2009 Jul 7;151(1):44–58. w11–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-1-200907070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2001 Mar;56(3):M146–156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grov C, Golub SA, Parsons JT, Brennan M, Karpiak SE. Loneliness and HIV-related stigma explain depression among older HIV-positive adults. AIDS care. 2010 May;22(5):630–639. doi: 10.1080/09540120903280901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.http://www.mocatest.org/default.asp. Accessed March 25, 2014.

- 36.Valcour VG. Evaluating cognitive impairment in the clinical setting: practical screening and assessment tools. Topics in antiviral medicine. 2011 Dec;19(5):175–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milanini B, Wendelken LA, Esmaeili-Firidouni P, Chartier M, Crouch PC, Valcour V. The Montreal cognitive assessment to screen for cognitive impairment in HIV patients older than 60 years. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2014 Sep 1;67(1):67–70. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor HL, Jacobs DR, Jr, Schucker B, Knudsen J, Leon AS, Debacker G. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. Journal of chronic diseases. 1978;31(12):741–755. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terzian AS, Holman S, Nathwani N, et al. Factors associated with preclinical disability and frailty among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in the era of cART. Journal of women's health (2002) 2009 Dec;18(12):1965–1974. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, Doucette JT. Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1995 May 3;273(17):1348–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green TC, Kershaw T, Lin H, et al. Patterns of drug use and abuse among aging adults with and without HIV: a latent class analysis of a US Veteran cohort. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2010 Aug 1;110(3):208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shippy RA, Karpiak SE. The aging HIV/AIDS population: fragile social networks. Aging & mental health. 2005 May;9(3):246–254. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331336850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ershler WB, Keller ET. Age-associated increased interleukin-6 gene expression, late-life diseases, and frailty. Annual review of medicine. 2000;51:245–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferrucci L, Harris TB, Guralnik JM, et al. Serum IL-6 level and the development of disability in older persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1999 Jun;47(6):639–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karpiak SE, Shippy RA, Cantor MH. Research on Older Adults with HIV. New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010 Dec 7;75(23):2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tozzi V, Balestra P, Bellagamba R, et al. Persistence of neuropsychologic deficits despite long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV-related neurocognitive impairment: prevalence and risk factors. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2007 Jun 1;45(2):174–182. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318042e1ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Breyer BN, Van den Eeden SK, Horberg MA, et al. HIV status is an independent risk factor for reporting lower urinary tract symptoms. The Journal of urology. 2011 May;185(5):1710–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hazzard's Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, 6e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tinetti ME, Kumar C. The patient who falls: “It's always a trade-off”. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2010 Jan 20;303(3):258–266. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kane RL, K T, Shamliyan T, Pacala JT. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment 87. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Jul, 2011. Common Syndromes in Older Adults Related to Primary and Secondary Prevention. AHRQ Publication No. 11-05157-EF-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cigolle CT, Ofstedal MB, Tian Z, Blaum CS. Comparing models of frailty: the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009 May;57(5):830–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morgan EE, Iudicello JE, Weber E, et al. Synergistic effects of HIV infection and older age on daily functioning. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2012 Nov 1;61(3):341–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826bfc53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marzolini C, Elzi L, Gibbons S, et al. Prevalence of comedications and effect of potential drug-drug interactions in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Antiviral therapy. 2010;15(3):413–423. doi: 10.3851/IMP1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.