Abstract

Systemic 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment ameliorating murine inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) could not be applied to patients because of hypercalcemia. We tested the hypothesis that increasing 1,25(OH)2D3 synthesis locally by targeting delivery of the 1α-hydroxylase gene (CYP27B1) to the inflamed bowel would ameliorate IBD without causing hypercalcemia. Our targeting strategy is the use of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes as the cell vehicle and a macrophage-specific promoter (Mac1) to control CYP27B1 expression. The CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes migrated initially to inflamed colon and some healthy tissues in dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) colitis mice; however, only the migration of monocytes to the inflamed colon was sustained. Adoptive transfer of Gr1+ monocytes did not cause hepatic injury. Infusion of Mac1-CYP27B1-modified monocytes increased body weight gain, survival, and colon length, and expedited mucosal regeneration. Expression of pathogenic Th17 and Th1 cytokines (interleukin (IL)-17a and interferon (IFN)-α) was decreased, while expression of protective Th2 cytokines (IL-5 and IL-13) was increased, by the treatment. This therapy also enhanced tight junction gene expression in the colon. No hypercalcemia occurred following this therapy. In conclusion, we have for the first time obtained proof-of-principle evidence for a novel monocyte-based adoptive CYP27B1 gene therapy using a mouse IBD model. This strategy could be developed into a novel therapy for IBD and other autoimmune diseases.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease are the two major inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), which affect more than 3.6 million people in the United States and Europe alone.1,2 The incidence of IBD, especially UC, has significantly increased in the traditionally low-risk areas, such as Asia and southern Europe.3 IBD is not only a common disease but also reoccurring and incurable, leading to significant morbidity and even death at advanced stages. Current IBD managements include the use of anti-inflammatory drugs (5-aminosalicylic acid), immuno-suppressants (glucocorticoids, azathioprine, and 6-mercaptopurine), and the most recently biological drugs, such as anti-tumor necrosis factor-α monoclonal antibody (infliximab).4 These drugs have limitations due to their various severe side effects.3,4,5,6 Of particular concern is the use of anti-immunity-based drugs because they can increase the risk of serious infection that has already been a problem in IBD patients. Thus, an effective and safe therapy for IBD remains to be an important unmet need.

IBD has been viewed as an autoimmune disease, in which mucosal immune system shows an aberrant response towards luminal antigens, such as dietary factors and/or commensal bacteria, in genetically susceptible individuals.7 Thus, agents with both anti-immune and anti-microbial properties are likely to be better candidates for IBD treatment than those with either function alone. One of the agents falling into this category is 1,25(OH)2D3, the active form of vitamin D3. Although the classical function of this hormone is to regulate calcium homeostasis, studies in the past two decades have provided compelling evidence for an important role of 1,25(OH)2D3 in suppressing autoimmune inflammation.8,9,10 It appears that 1,25(OH)2D3 exerts this action via regulating the development/function of essentially all types of cells involved in innate and adoptive immunity.11,12,13,14,15 1,25(OH)2D3, unlike traditional immunosuppressive molecules, does not promote, but in fact may reduce, infection by promoting antimicrobial peptide production.16,17,18 Moreover, it improves mucosal barrier function, which is compromised in IBD, by enhancing synthesis of tight junction proteins.19,20,21

The therapeutic benefits of 1,25(OH)2D3 in autoimmune disorders was first demonstrated in 1991 in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model of human multiple sclerosis.22 Subsequently, systemic treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 was shown to be effective in treatment of IBD in mice.23,24,25,26 Unfortunately, the optimal therapeutic efficacy could not be achieved unless hypercalcemic doses of 1,25(OH)2D3 were utilized, regardless of the types of the diseases.14,16,22,23,24,25,27 Thus, until the issue of hypercalcemia is satisfactorily addressed, this promising therapy is unlikely to be used in clinical settings.

One way to achieve the therapeutic benefit but also circumvent the systemic hypercalcemic adverse effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 is to increase the synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3 locally in the inflamed bowel. It is known that the rate of 1,25(OH)2D3 synthesis in the body is determined by the hydroxylation of 25(OH)D3 in the kidney as well as in extra-renal tissues; a reaction that is catalyzed by the 1α-hydroxylase encoded by the CYP27B1 gene.28 We reasoned that, if a strategy could be developed to target expression of this enzyme locally to the inflamed bowel, therapeutically adequate concentration of 1,25(OH)2D3 could be obtained locally to treat intestinal lesions without causing hypercalcemia.

To test the aforementioned hypothesis, we developed a strategy to target the 1α-hydroxylase gene based on the physiological phenomena that macrophages are recruited to the inflamed bowel, and that the Mac1 promoter is activated in the recruited activated macrophages. We selected a subtype of monocytes/macrophages, which specifically migrate to inflamed tissues, and engineered these cells to overexpress the 1α-hydroxylase gene under the control of the promoter of the Mac1 gene, which is expressed at high level upon macrophage activation.29 We found that a single adoptive transfer of the CYP27B1 gene-modified monocytes/macrophages effectively ameliorated acute IBD induced by the dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) insult in mice. Importantly, this therapy did not cause hypercalcemia as it occurs during systemic 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment.

Results

Development of a novel strategy to target expression of CYP27B1 locally at the site of inflamed bowel

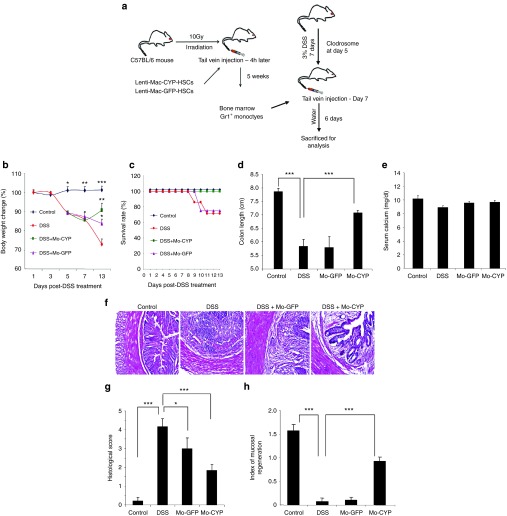

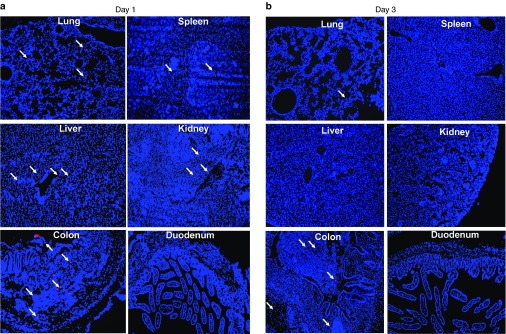

Development of the adoptive CYP27B1 gene therapy requires at least three key elements: (i) an optimal cell vehicle to deliver the CYP27B1 gene to the inflamed bowel, (ii) a suitable promoter to restrict the CYP27B1 expression in activated macrophages, and (iii) production of adequate amounts of 1,25(OH)2D3 in the CYP27B1 gene-modified cells. We selected the CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes as the cell vehicle because previous study has shown that Gr1+, but not Gr1−, monocytes preferably traffic to inflamed tissues in other disease model.30 In addition, our pilot experiments in the DSS-colitis model have confirmed that there was inefficient recruitment of Gr1− monocytes to the inflamed colon (data not shown). Although CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes were able to improve the DSS-induced colitis and CD14+ blood monocytes were recruited to the inflamed bowel of IBD patients,31,32 distribution of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes and their specificity of trafficking to the inflamed colon have not yet been fully investigated in the IBD model. To address this important issue, we injected fluorescence-labeled CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes and evaluated their tissue distribution profile by fluorescence microscopy. We chose to use far-red dye to label the monocytes, because this fluorescent dye has essentially no auto fluorescence in frozen tissue sections and has been used to evaluate trafficking of mesenchymal stem cells in mice with DSS-induced colitis.33 At 1 day postinjection, labeled monocytes were present not only in the inflamed colon but also in the lung, kidney, spleen, and liver of the injected animals (Figure 1a). Interestingly, no labeled cells were detected in the duodenum, which is the primary site of active Ca absorption, and which is not inflamed following the DSS insult (Figure 1a). At 3 days post-cell injection, substantial amounts of cells remained in the inflamed colon, while those labeled monocytes, which initially migrated to other tissues, all disappeared (Figure 1b). These data suggest that CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes require an inflammatory environment to survive or engraft, thereby representing a suitable cell vehicle for use to target CYP27B1 gene expression at the inflamed bowel.

Figure 1.

Engraftment of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes at the inflamed colon of mice with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis. (a and b) DSS colitis in 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice was induced as described in Materials and Methods. Gr1+ monocytes were isolated from C57BL/6 mice, labeled with far-red dye and injected, via tail vein, into colitis mice (5 × 106 cells per mouse) at day 7 of the DSS treatment. At day 8 or 10 (1 or 3 days post-cell infusion), mice were perfused with phosphate-buffered saline and the tissue samples were collected for imaging. (a) Ex vivo imaging of far-red dye labeled monocytes in frozen tissue sections at day 1 post-cell infusion. (b) Ex vivo imaging of far-red dye labeled monocytes in frozen tissue sections at day 3 post-cell infusion. Arrows indicate labeled monocytes in organs of injected mice. Images show ×100 original magnifications.

It has previously been reported that hepatic damages in mice treated with carbon tetrachloride was attenuated in CCR2 knockout mice, which had reduced number of Gr1+ monocytes in the injured liver.34 These data suggest indirectly that G1+ monocyte may enhance liver damage under certain conditions. Thus, we also evaluated if adoptive transfer of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes could potentially cause liver damage in mice with DSS-induced colitis. Treatment of mice with DSS alone or together with the monocyte transfer had no significant effect on liver expression of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-6 (Supplementary Figure S1a,b). Expression of tumor necrosis factor-α and IFN-α in liver was very low and did not differ significantly among treatment groups (data not shown). The activity of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), a commonly used serum marker of liver damage, was also not affected by either the DSS treatment or the monocyte infusion (Supplementary Figure S1c). Collectively, our data suggest that the CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes purified under our defined conditions are not likely to have negative effects on the liver function in mice of this acute IBD model.

While the use of inflammation-specific CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes as the cell vehicle may be adequate to target expression of exogenous CYP27B1 gene to the inflamed bowel, the use of a tissue-specific promoter, such as the Mac1 promoter, which is highly active only in activated macrophages35 can further restrict CYP27B1 expression to activated macrophages. The activity and specificity of the Mac1 promoter to drive marker gene green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression was assessed in vivo using mice transplanted with hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) that had been transduced with a lentiviral vector expressing the GFP gene driven by the Mac1 promoter (Figure 2a). As anticipated, the majority of peritoneal cells of these mice are macrophages, and they expressed Mac1-driven GFP (data not shown). Further activation of these macrophages by treatment with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate in vitro yielded much stronger expression of Mac1-driven GFP (Figure 2b). On the other hand, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-treated spleen cells, which contain donor HSCs-derived monocytes, showed very low level of GFP expression (Figure 2b). To further evaluate the relative activity of the Mac1 promoter in macrophages versus resting monocytes, Gr1+ monocytes isolated from bone marrow transplants were treated with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) to induce differentiation of monocytes to M2 macrophages. The level of GFP signal was very weak in resting monocytes (data not shown) or at day 3 following M-CSF treatment (Figure 2c). However, at day 7, when monocytes were fully differentiated into M2 macrophages, the GFP expression was clearly evident. These data suggest that the activity of the Mac1 promoter is weak in monocytes, but it becomes highly activated after the monocytes are differentiated into macrophages.

Figure 2.

Mac1 promoter was able to yield high levels of transgene expression in activated macrophages. (a) The lentiviral vector contains a central polypurine tract (cPPT) for efficient nuclear entry, and self-inactivating deletion in the U3 region of the LTRs. The cis-acting partial Gag sequence (Gag) and Rev-response element (RRE) sequences are also indicated. WPRE (woodchuck hepatitis post-transcriptional regulatory element) element is included to enhance marker gene expression. (b) Sca1+ HSCs were isolated from bone marrow cells of C57BL/6 mice, transduced with the lentiviral vector Mac1-GFP-PGK-mCherry, and injected via tail vein into recipient mice. Five weeks post-bone marrow transplantation, peritoneal macrophages and splenocytes were isolated and further treated with 50 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate for 16 hours. Expression of the marker gene, GFP, was visualized under fluorescent microscopy (×200 magnification). (c) Bone marrow CD11b+Gr1+ monocytes were isolated from the bone marrow transplants and then treated with macrophage colony-stimulating factor for 7 days. Expression of the GFP marker gene was visualized under fluorescent microscopy at day 3 and day 7 (×200 magnification).

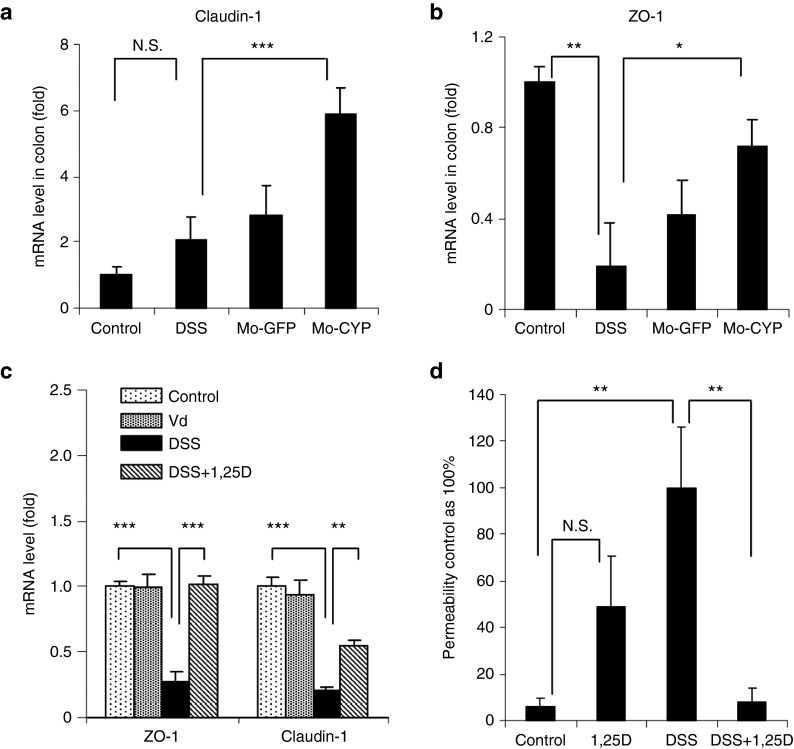

Adoptive transfer of Gr1+ monocytes or M2 macrophages overexpressing CYP27B1 effectively ameliorated DSS-colitis without causing hypercalcemia

We next evaluated if the gene targeting strategy developed above could deliver the therapeutic CYP27B1 gene to the inflamed colon to treat DSS-induced colitis. Because lentiviral vectors transduce Gr1+ monocytes very poorly and ineffectively, we chose an alternative approach to obtain proof-of-principle evidence for the efficacy of our therapy by using monocytes isolated from bone marrow transplants overexpressing CYP27B1 under the control of the Mac1 promoter as the cell vehicle. The design of this experiment was illustrated in Figure 3a. Sca1+ HSCs were transduced with either Mac1-CYP27B1-PGK-GFP lentiviral vector (therapeutic vector) or Mac1-GFP-PGK-mCherry (control vector). fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis revealed that ~70% of HSCs were transduced by the lentiviral vectors (Supplementary Figure S2a). Five weeks after transplantation with the transduced HSCs, CD11b+Gr1+ monocytes were isolated from bone marrow of the transplant recipients. Essentially all of the purified monocytes were positive for both CD11b and Gr1 (~97%, Supplementary Figure S2b) and more than 60% of these monocytes expressed the GFP transgene (Supplementary Figure S2c).

Figure 3.

Adoptive transfer of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes overexpressing CYP27B1 ameliorated dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis without causing hypercalcemia. (a) Six-week-old C57BL/6 mice were transplanted with Sca1+ HSCs transduced with the Mac1-CYP (Mac1-hCYP27B1-PGK-mCherry) or the Mac1-GFP (Mac1-GFP-PGK-mCherry) lentiviral vector. At the age of 8 weeks, each recipient mouse was treated with DSS to induce colitis. At day 7 of the DSS treatment, mice were injected via tail vein with 4 × 106 Gr1+ monocytes that were isolated from the bone marrow transplants. (b) Body weights were recorded during disease induction and recovery period. (c) Survival rate was recorded daily. (d) At day 13 (6 days post-monocytes infusion), mice were sacrificed and the colon length was measured. (e) Serum concentrations of calcium were measured 6 days post-monocytes infusion. Data from one of the two independent experiments are shown as means ± SEM (n = 5–7). (f) Representative H&E staining of distal colon cross-sections. All images are shown at 20× magnification. (g) Histological score was measured in cross-sections of the distal colon. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 10–12) pooled from two independent experiments. (h) Mucosal regeneration index was determined at cross-sections of the distal colon (Material and Methods). Data of the representative of the two independent experiments are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4–5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, or ***P < 0.001 versus DSS-treated mice. Mo, monocytes.

Adoptive transfer of Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing Gr1+ monocytes obtained from bone marrow transplants not only prevented further loss in body weight but also regained some of the lost body weight during the disease induction phase (Figure 3b). Approximately 20% of DSS-colitis mice receiving no treatment or infused with GFP-expressing control monocytes died before the end of the experiment (Figure 3c). In contrast, no mortality occurred in mice treated with Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing monocytes (Figure 3c). There was also a significant increase in colon length in mice treated with Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing monocytes compared to mice receiving no treatment or Mac1-GFP-expressing monocytes (Figure 3d; Supplementary Figure S3a), indicating that the treatment also effectively reversed the DSS-induced shrinkage of the colon. Importantly, serum Ca level did not differ significantly among the test groups (Figure 3e). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the colon cross-sections revealed robust regeneration of the lost crypts, accompanied by attenuated inflammatory cell infiltration (Figure 3f; lower magnification is shown in Supplementary Figure S3b). Accordingly, histological score and mucosal regeneration index were significantly improved by the therapy (Figure 3g,h). Mice with DSS-induced colitis infused with Mac1-GFP-expressing monocytes showed only moderate improvement in body weight loss (Figure 3b). Moreover, this cell vehicle treatment alone (without the Mac1-CYP27B1 transgene) produced little benefits in terms of reducing mortality (Figure 3c), reducing DSS-induced shrinkage of colon (Figure 3d), or enhancing mucosal regeneration (Figure 3f–h; Supplementary Figure S3a,b).

After establishing the proof-of-principle for our therapy using Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing monocytes generated by the bone marrow transplantation approach, we sought to develop a clinically relevant strategy to engineer monocytes to overexpress Mac1-CYP27B1 for the IBD treatment. We found that, in contrast to monocytes in suspension, attached macrophages generated from Gr1+ monocytes treated with M-CSF were efficiently transduced with lentivial vectors (~70%, Supplementary Figure S4a). FACS analysis revealed that ~85% of the macrophages remained Gr1-positive (Supplementary Figure S4b). While level of CD11b expression remained unchanged (Supplementary Figure S4c), expression of the M2 macrophage marker, CD206, in these macrophages was high (Supplementary Figure S4d). This result indicates that the macrophages prepared under our defined conditions belong to the immunosuppressive M2 macrophages. Interestingly, compared to monocytes, these M2 macrophages expressed high levels of chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) (Supplementary Figure S4e), which is essential for the homing of monocytes to inflammatory sites.36

Next, experiments were performed to evaluate if M2 macrophages transduced with the Mac1-CYP27B1 lentiviral vector was able to ameliorate DSS-induced colitis. M2 macrophages transduced with the Mac1-CYP27B1 lentiviral vector led to high levels of CYP27B1 expression and the consequent synthesis of large amounts of 1,25(OH)2D3 from the substrate, 25(OH)D3 (Figure 4a,b). Similar to the treatment with Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing Gr1+ monocytes, a single adoptive transfer of Mac1-CYP27B1 gene modified M2 macrophages to mice with DSS-induced colitis (Supplementary Figure S5a) prevented further loss in body weight and reduced mortality without significantly elevating serum Ca levels (Supplementary Figure S5b–d). These benefits were accompanied with a remarkable improvement in histopathology (Figure 4c–e; low-magnification data are shown in Supplementary Figure S5e).

Figure 4.

Adoptive transfer of CD11b+/Gr1+ M2 macrophages overexpressing CYP27B1 improved IBD pathology. (a and b) M2 macrophages were transduced with the indicated lentiviral vectors and were incubated with 2.5 μmol/l 25(OH)D3 for 20 hours (Materials and Methods). (a) Human CYP27B1 mRNA level was measured by real-time qRT-PCR. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 4). ***P < 0.001. (b) 1,25(OH)2D3 concentration in the conditioned media pooled from triplicate samples was measured by radioimmunoassay. (c) Colitis induction in 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice and M2 macrophages adoptive transfer were performed described in Material and Methods. On day 13 (6 days post-macrophages infusion), mice were sacrificed, and the colon samples were collected. Representative H&E staining images of the frozen distal colon sections were shown. All images are shown at 20× magnification. (d) Histological score of colon sections was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 5). (e) Mucosal regeneration index was determined as described in Material and Methods. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4–5). **P < 0.01, or ***P < 0.001 versus dextran sulfate sodium-treated mice. M2Ø, M2 macrophages.

Notably, while adoptive transfer of Mac1-GFP-expressing control M2 macrophages alone, reduced further body weight loss moderately (Supplementary Figure S5b), it did not significantly improve the mucosal histopathology (Figure 4c–e). These results indicate that M2 macrophages can be used in place of Gr1+ monocytes as the cell vehicle for our therapy.

Evidence that Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing monocytes interacted with immune cells and epithelial cells to reduce inflammation and to increase mucosal regeneration

Toward understanding the mechanism by which adoptive transfer of Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing monocytes ameliorates IBD, we evaluated the effect of recruitment of Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing monocytes to inflammatory sites on immune cells and epithelial cells. The pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by infiltrating macrophages and dendritic cells (tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-23) were all increased dramatically by the DSS insult and these increases were significantly suppressed by adoptive transfer of the Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing monocytes (Figure 5a). Similarly, adoptive transfer of Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing monocytes significantly suppressed the DSS-induced expression of pathogenic Th1 and Th17 cytokines (IFN-α and IL-17a) (Figure 5b,c). Infusion of control Mac1-GFP-expressing monocytes alone did not significantly reduce the expression of inflammatory cytokines except for IL-6 and IFN-α (Figure 5a,b). The expression of protective Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13) in both the colon (Figure 6a) and lymph nodes (Figure 6b) was increased significantly by infusion of Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing monocytes but not the Mac1-GFP-expressing monocytes. However, in contrast to the other Th2 cytokines examined, the expression of IL-10 was increased (rather than decreased) in the inflamed colon and this increase was attenuated by the Mac1-CYP27B1 monocyte transfer (Figure 6a).

Figure 5.

Adoptive transfer of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes overexpressing CYP27B1 reduced the expression of inflammatory cytokines in the colon of mice with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis. The experimental design was described in Figure 3. (a) Real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis of the mRNA levels of proinflammatory cytokines produced mainly by macrophages/dendritic cells. (b) Real-time qRT-PCR analysis of the mRNA level of IFN-γ, a pathogenic Th1-specific cytokine in the colon. (c) Real-time qRT-PCR analysis of the mRNA level of IL-17a, a pathogenic Th17-specific cytokine in the colon. Data of a representative experiment of two independent experiments are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4–6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, or ***P < 0.001 versus DSS-treated mice. Mo, monocytes.

Figure 6.

Adoptive transfer of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes overexpressing CYP27B1 significantly increased expression of the protective Th2 cytokines. The experimental design was described in Figure 3. Colon and lymph node samples were collected 6 days post-monocytes infusion. (a) mRNA levels of Th2 cytokines in colon were measured by real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). (b) mRNA levels of Th2 cytokines in lymph nodes were measured by real-time qRT-PCR. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4–6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus dextran sulfate sodium-treated mice. Mo, monocytes.

We also evaluated the effect of Mac1-CYP27B1 monocyte infusion on gene expression of claudin-1 and “zonula occludens” protein-1 (ZO-1), which are important epithelial tight junction proteins. Consistent with the results obtained using systemic 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment,20 adoptive transfer of Mac1-CYP27B1 monocytes significantly increased the mRNA levels of these two genes (Figure 7a,b). Next, we determined whether the increased expression of the tight junction genes in the inflamed colon is a secondary effect resulting from the recovery of colon inflammation or a direct effect of the locally produced 1,25(OH)2D3 on epithelial cells. Treatment of Caco-2 epithelial cells with DSS reduced mRNA level of these two genes. Such decrease was either completely or partially abolished by the 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment (Figure 7c). Consistent with this data, treatment of Caco-2 cell monolayers with 1,25(OH)2D3 functionally prevented the DSS treatment-induced monolayer leakage (Figure 7d). Thus, it is very likely that 1,25(OH)2D3 produced locally by Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing monocytes could promote mucosal regeneration in part through direct actions on epithelial cells to promote expression of tight junction genes.

Figure 7.

Evidence that adoptive transfer of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes overexpressing CYP27B1 ameliorated dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in part through restoring epithelial barrier function. (a and b) The experimental design was described in Figure 3. Colon tissues were collected 6 days post-monocytes infusion. (a,b) The mRNA level of two tight junction genes, claudin-1 and ZO-1, in colon was measured by real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4–6). (c) Monolayers of Caco-2 cells were pretreated with or without 10 nmol/l 1,25(OH)2D3 for 48 hours. 5% DSS was then added to the media for 10 hours before the analysis of gene expression. The mRNA level of ZO-1 and claudin-1 in cultured epithelial cells was determined by real-time qRT-PCR. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4). (d) The effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on paracellular permeability of epithelial cell monolayers. Epithelial monolayers were obtained by culturing Caco-2 cells on filters in transwells and were treated as described in panel c. The permeability to fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated dextran is presented as % of the value in cells treated with DSS only. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, or ***P < 0.001 versus DSS-treated group.

Discussion

The therapeutic benefit of 1,25(OH)2D3 in treatment of autoimmune inflammatory diseases was established in animal models more than two decades ago.22,23,24,25,26 However, little progress has been made toward translation of this invention to the treatment of human diseases, due to lack of a strategy to overcome the attending hypercalcemia. Herein, we have obtained proof-of-principle evidence for a novel biologic therapy, which is 1,25(OH)2D3-based but is entirely different from the systemic 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment. This therapy, which involves adoptive transfer of inflammation-specific monocytes engineered to locally synthesize 1,25(OH)2D3, was capable of ameliorate IBD without causing hypercalcemia.

The proof-of-principle evidence for this experimental therapy was obtained using the DSS-induced colitis mouse IBD model that faithfully reproduces many of the immunological disturbances observed in human IBD.37 Recent data suggest that microbiota plays an important role in maintaining homeostasis in the gut and dysbiosis is often associated with human IBD.38 In this regard, although DSS-induced colitis may not represent the entire pathogenic process of human IBD, the DSS-induced colitis faithfully simulates the biological consequences as a result of dysbiosis and is therefore highly relevant to human IBD.

The gross and local pathological changes in DSS-induced colitis include hematochezia, body weight loss, colon shrinkage, mucosal ulcers, and inflammatory cells infiltration.37 All of these pathologies were remarkably improved by a single i.v. infusion of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes overexpressing CYP27B1 controlled by the Mac1 promoter. Zhang et al.31 reported recently that CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes were induced in the spleen of mice with DSS-induced colitis, and that adoptive transfer of splenic CD11b+/Gr1+ cells derived from the diseased mice improved DSS-induced colitis.31 These monocytes are referred to inflammatory monocytes with immunosuppressing function and can be quickly recruited into inflammation sites. In this regard, the biological characteristics and function of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes are not unique to the DSS-induced colitis model.

We found that infusion of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes overexpressing GFP moderately reduced body weight loss and marginally improved colon histological score. However, these monocytes did not significantly increase colon length or reduce mortality under our experimental conditions. In contrast, treatment with CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes overexpressing CYP27B1 significantly improved the majority of disease parameters with the most pronounced effect observed on crypt sprouting. The incomplete restoration of mucosal architecture is likely due to the extremely severe mucosal damages obtained using our protocol as well as the short duration of the treatment. It is important to point out that the therapeutic benefit might have been underestimated, as some severely diseased colitis mice and colitis mice treated with marker gene-expressing monocytes alone did not survive and were excluded from histopathological analysis. Taken together, our findings clearly demonstrate that the combination of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes cell therapy and CYP27b1 gene therapy could effectively ameliorate DSS-induced colitis.

Past studies suggest that Th1 and Th17 adaptive immune responses play a major role in the pathogenesis of DSS-induced colitis.39 The gut is a unique tissue, in that it has developed its own complex immune system, the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT).40 The GALT consists of Peyer's patches (the lymphoid aggregates in the submucosa) and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) in the intestinal wall.40 As our therapy is local, it is important to examine if recruited Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing monocytes interacted with immune cells in the inflamed colon. Our results demonstrate that the expression of protective T cell subtype (Th2) cytokines was increased whereas the expression of the pathogenic effector T cell (Th1 and Th17) cytokines was decreased in the colon of colitis mice treated with CYP27B1 gene-modified monocytes (Figures 5 and 6).

Interestingly, the colonic expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was decreased rather than increased following the adoptive transfer of Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing monocytes in mice with DSS-induced colitis. It is well known that IL-10 is an immunoregulatory cytokine that efficiently blocks the in vivo production of proinflammatory cytokines in colitis. IL-10-deficient mice spontaneously develop chronic colitis due to an aberrant immune response to commensal bacteria.41 However, several studies have shown that the production of IL-10 significantly increased in the colon of mice with DSS-induced colitis and peaked at late stages of the disease.39,42,43 In addition, production of IL-10 by lamina propria mononuclear cells was significantly enhanced in colon of mice with DSS-induced colitis.44 Thus, our findings that colonic expression of IL-10 was increased upon the DSS insult are consistent with previous reports. These data suggest that endogenous IL-10 may participate in a self-regulatory circuit that counteracts the inflammatory process in this animal model. Moreover, neutralizing IL-10 modestly augmented tissue damage in DSS-induced colitis, suggesting that the endogenous IL-10 is inadequate to suppress DSS-induced colitis in the presence of excessive amounts of inflammatory cytokines.42 Taken together, the therapy developed in our study does not seem to act directly via modulating the local production of IL-10 in the inflamed colon. The reduced colonic expression of IL-10 following this therapy could be the secondary effect resulting from the recovery of colonic inflammation. Overall, our findings support our premise that this therapy attenuates intestinal inflammation in part through skewing the development of T cell differentiation locally in the colon in favor of anti-inflammation and immunological tolerance (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

A proposed model of the mechanism by which adoptive CYP27B1 gene therapy acts to ameliorate dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Infused exogenous Gr1+ monocytes or M2 macrophages overexpressing CYP27B1 guided by the Mac1 promoter are recruited to the inflamed colon, where they are activated to express exogenous CYP27B1 to synthesize 1,25(OH)2D3 locally. 1,25(OH)2D3 produced by the activated exogenous macrophages then acts on T cells to cause a switch from the pathogenic Th1-Th17 response to the protective Th2 response. 1,25(OH)2D3 also acts on infiltrating macrophages leading to reduced expression of proinflammatory cytokines. As a result of the reduced inflammation, mucosal regeneration is expedited. In addition, 1,25(OH)2D3 also promotes mucosal regeneration via increasing epithelial tight junction protein synthesis and restoring epithelial barrier function.

Intestinal barrier breaching contributes to further aggravation of the disease as a result of bacterial infection.45 Therefore, maintaining the mucosal barrier function and integrity could provide potential benefits in the treatment of IBD.46 An important determinant of the mucosal barrier function/integrity is the synthesis of epithelial tight junction proteins. It is possible that increased expression of these two junction proteins by our therapy is a secondary effect of mucosal recovery. However, our finding that 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment of epithelial cells attenuated the negative effect of DSS on the expression of tight junction gene and the integrity of the epithelial monolayer (Figure 7) supports our model that 1,25(OH)2D3 produced by the Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing monocytes acts directly on proliferating epithelial cells to promote tight junction gene expression (Figure 8).

The therapeutic benefit of the adoptive CYP27B1 gene therapy is not unexpected, as systemic 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment is known to ameliorate DSS-induced colitis, and our therapy is designed to promote local 1,25(OH)2D3 synthesis in the inflamed colon. The significant impact of our study is that, while this therapy is at least as effective as the systemic 1,25(OH)2D3 therapy, it does not cause hypercalcemia, which is a significant safety issue that creates severe short- and long-term health problems.24 The successful elimination of hypercalcemia is a direct result of our carefully designed CYP27B1 gene targeting strategy. We found that CD11b+Gr1+ monocytes do not traffic to duodenum that is not inflamed in mice with DSS-induced colitis (Figure 1). Because duodenum is one of the primary sites of active calcium absorption, the inability of the Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing monocytes to migrate to this region of the gut helps to avoid a large increase in the intestinal calcium absorption, which is the primary cause of 1,25(OH)2D3-induced hypercalcemia. We did observe that the Gr1+ monocytes migrated to other tissues; however, their presence is transient and is unlikely to yield significant adverse side effects (Figure 1). On the other hand, sustained presence of G1+ positive monocytes was seen in the inflamed colon. Past studies, using CCR2 knockout mice, have clearly demonstrated that CCR2 via binding to its ligand MCP-1 present in the inflamed sites is essential for recruitment of Gr+ positive monocytes to the inflamed tissues.47 The high level of CCR2 expression in both CD11b+Gr1+ monocytes and their derived macrophages that we observed could explain the relative specificity of the CD11b+Gr1+ monocytes homing to inflamed colon.

The use of Mac1 promoter to control CYP27B1 expression may have also contributed to the prevention of hypercalcemia. Mac1 promoter was only weakly active in monocytes but its activity was significantly increased in differentiated/activated macrophages35 (Figure 2b). Therefore, the use of the Mac1 promoter may have served as a secondary mechanism to ensure that active expression of the exogenous CYP27B1 occurs only after infused monocytes/macrophages have become activated macrophages in the local intestinal lesion.

We acknowledge that our therapy is still in its infant stage and the long-term safety and efficacy of this novel therapy needs to be thoroughly evaluated before it can be advanced to translational studies. One of the concerns of using CD11+/Gr1+ monocytes or their M2 macrophages derivatives as the cell vehicle could be that these cells are immunotolerigenic, thereby exhibiting general immunosuppressive activity. Such activities could potentially lead to suppression of the immune system that may increase the chances of infection or tumor growth. It is possible that such potential risk could be prevented or minimized by the 1,25(OH)2D3 synthesized by the Mac1-CYP27B1-expressing macrophages. 1,25(OH)2D3 is a regulator and not merely a suppressor of the immune system. 1,25(OH)2D3 can enhance production of antibacterial peptides to fight against pathogenic bacteria. Also, 1,25(OH)2D3 has been shown to effectively treat various cancers in both experimental animals and humans.48 Our idea that a combination of M2 macrophage and CYP27B1 could be relatively safer than M2 macrophages alone or other immunosuppressants need to be confirmed experimentally.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of plasmid constructs. The 1.6-kb C-terminally Myc-tagged human CYP27B1 cDNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a plasmid containing the human CYP27B1 cDNA (OriGene, Rockville, MD). The amplified hCYP27B1 cDNA fragment with a 5′ KOZAK ribosome entry sequence and the 1.7-kb human Mac1 promoter were cloned into the pRRL-SIN.cPPt.PGK-GFP.WPRE lentiviral vector (Addgene, Cambridge, MA), in which the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter had been deleted. The resulting construct was designated the Mac1-CYP-PGK-GFP. This bicistronic plasmid expresses CYP27B1 that is controlled by the macrophage-specific Mac1 promoter and GFP that is controlled by the tissue nonspecific PGK promoter. Similarly, a bicistronic vector expressing GFP under the control of the Mac1 promoter and mCherry under the control of PGK promoter (Mac1-GFP-PGK-mCherry) was also prepared as a control.

Lentiviral vectors. Lentiviral vectors were produced in HEK-293T cells as previously described.49 Briefly, HEK-293T cells were transfected with the indicated transgene plasmids together with CMV-VSVG and PAX2 plasmids using calcium phosphate method. Supernatants were collected 48 hours after transient transfection and viral particles were concentrated by centrifugation for 24 hours at 6,000 × g at 4 °C. After removal of the supernatant, viral particles were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 5% glycerol and stored at −80 °C. The biological titers were ~5 × 107 particles/ml, as determined by FACS analysis of GFP+ cells in 293T cells transduced with various doses of the concentrated vectors.

Animals. Female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were kept in pathogen-free environments at Loma Linda University Animal Care Facility and all experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Loma Linda University.

Induction of DSS colitis. Colitis was induced in C57BL/6 mice by providing the animals with 3% DSS (MP Biomedicals, molecular weight = 36–50 kDa, OH) in drinking water for 7 days ad libitum. Mortality and body weight of each animal were recorded daily.

Preparation of bone marrow monocytes and macrophages. After lysis of the red blood cells, bone marrow nucleated cells were collected and used for isolation of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes using the MACS technology. Gr1+ cells were positively selected using APC-conjugated anti-Gr1 antibody and anti-APC MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). To obtain M2 macrophages, the isolated bone marrow CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes were cultured in RPMI medium 1640 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and 40 ng/ml of mouse M-CSF (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 5 days.

Adoptive transfer of monocytes or macrophages. Mice were injected i.v. with 100 μl clodrosome-containing liposomal clodronate (Encapsula NanoSciences, Nashville, TN) to deplete endogenous monocytes on day 5 post-DSS treatment. For monocytes adoptive transfer, CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes, isolated from bone marrow cells, were injected via tail vein into mice with DSS-induced colitis 2 days later. For macrophages adoptive transfer, M2 macrophages were transduced with indicated lentiviral vectors twice at a multiplicity of infection of 3 and injected via tail vein into mice on day 7 of the DSS treatment.

Ex vivo fluorescent imaging. Bone marrow CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes were labeled with 10 ìmol/l CellTrace Far Red (DDAO-SE; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol and a previous report.33 Labeled monocytes were injected into mice with DSS-induced colitis via tail vein (5 × 106 cells/mouse), which was pretreated the Clodrosome. Mice were sacrificed. The lungs, spleens, livers, kidneys, colon, and duodenum were isolated from the treated mice and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Frozen tissue sections were prepared, counter stained with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, and observed with a fluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) equipped with a near infrared wavelength filter.

Bone marrow transplantation. Sca1-positive HSCs were isolated from bone marrow cells using Sca-1 MicroBeads kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, human TPO (R&D Systems), mouse SCF (R&D Systems), human FL (R&D Systems), human G-CSF (R&D Systems), and human IL-3 (R&D Systems), each at 100 ng/ml. After overnight culture, cells were transduced with the indicated lentiviral vectors at an multiplicity of infection of 3. After 24 hours, cells were transduced again and harvested for transplantation. Five-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were injected via tail vein with transduced Sca1-positive HSCs (1 million cells per mouse) 2 hours after receiving a lethal dose of gamma irradiation (10Gy). Engraftment was assessed by FACS analysis of the percentage of GFP+ cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells 4–5 weeks post-transplantation.

Preparation of peritoneal macrophages. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 2 ml of 4% thioglycolate medium (Difco, Detroit, MI). Animals were sacrificed 3 days later, and thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages were harvested by lavage of the peritoneal cavity. Cells were seeded in 24-well plates (2 × 106 cells/well) and allowed to adhere to the culture plate for 4 hours at 37 °C. After gentle rinsing to remove nonadherent cells, the adherent cells were collected as peritoneal macrophages for in vitro experiments.

Flow cytometry. Transduced Sca1-positive cells or peripheral blood mononuclear cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and analyzed for GFP expression on a FACSAria II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for mouse CD11b, Gr1, or F4/80 were purchased from BD or eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Cells were stained with respective fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies, and then analyzed by flow cytometer.

In vitro evaluation of CYP27B1 transgene expression and activity. M2 macrophages were transduced with either Mac1-CYP27B1 or Mac1-GFP lentiviral vector at a multiplicity of infection of 3. After 2 days, the cells were seeded at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells/ml in 12-well plate, and the final concentration of 2.5 μmol/l of 25(OH)D3 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was added. After 20 hours incubation, cells were harvested for total RNA isolation, and the relative mRNA level of CPY27B1 was measured by real-time PCR. 1,25(OH)2D3 concentration in the conditioned media was determined by radioimmunoassay by the Heartland Assays (Ames, IA).

Histological analysis. After flushing with cold phosphate-buffered saline, the distal colon tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Eight micrometers-thick frozen sections were stained with H&E (Sigma-Aldrich). Sections were examined blindly and scored by a pathologist according to widely used criteria as previously described.50 Mucosal regeneration index was defined as the length of epithelial layer of the regenerated mucosa divided by the length of muscularis mucosa.

ALT activity assay. The serum level of ALT was measured using the ALT Activity Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Measurement of serum calcium. Serum calcium levels were measured using the Calcium Colorimetric Assay Kit (BioVision, Milpitas, CA).

Caco-2 cell culture and paracellular permeability assay. Human colonic Caco-2 epithelial cell lines, obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mmol/l glutamine, 100 µg/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin in humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Caco-2 cell monolayer was incubated with or without 10 nmol/l 1,25(OH)2D3 for 48 hours, and 5% DSS was then added to the medium for 10 hours. Paracellular permeability was determined by measuring the flux of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated dextran (4 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich) across Caco-2 monolayers. Briefly, monolayers were gently washed with Hank's balanced salt solution twice and transferred to 600 ml Hank's balanced salt solution. Apical chamber were gently aspirated and replaced with 100 ìl of 1 mg/ml fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated dextran in Hank's balanced salt solution. The monolayers were incubated at 37 °C for 2 hours. A volume of 100 ìl sample was removed from the basal chamber, and the fluorescence was measured using a fluorescent plate reader (excitation 485 nm, emission 520 nm, Synergy HT; Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Total RNA was isolated from cell and tissue samples using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was prepared using the superscript III cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen), according to instructions. Real-time PCR was performed with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) in 7500 Fast Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The data were normalized to GAPDH mRNA as a reference and presented as fold change relative to control samples. Specific primers for each gene of interest were given in Supplementary Table S1.

Statistical analysis. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM and statistically analyzed by Student's T-test or one-way analysis of variance. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Adoptive transfer of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes did not cause hepatic injury in mice with DSS-induced colitis. Figure S2. Transduction efficiency of Sca1+ HSCs with a lentiviral vector, and engraftment efficiency of exogenous HSCs in recipient mice. Figure S3. Adoptive transfer of CD11b+/Gr1+ monocytes overexpressing CYP27B1 decreased DSS-induced colonic inflammation, and reduced shrinkage and improved overall integrity of the colon of mice with DSS-induced colitis. Figure S4. Characterization of Gr1+ monocyte-derived M2 macrophages. Figure S5. Adoptive transfer of CD11b+/Gr1+ M2 macrophages overexpressing CYP27B1 increased body weight gain without causing hypercalcemia in mice with DSS-induced colitis. Table S1. Real-time qRT-PCR primer sets used in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Deb Chandra for characterization of the DSS-induced colitis model, Fatima Rajaallah for assistance with lentivirus production and the animal work, Penelope Garcia for excellent technical help, and Peter Gifford for his technical support in cryostat. This study was supported by funding from the Stewart Bainum Fund and Walter E. Macpherson Endowed Chair (to D.J.B.), the GI Foundation of Loma Linda University (to M.H.W.) and the Department of Medicine, Loma Linda University School of Medicine and US Department of Veterans Affairs (to X.Q.). Several of the authors (D.J.B., K.-H.W.L., and X.Q.) have declared conflict of interest as two US patents (US8,647,616 and US8,669,104) based in part on the findings of this study have been awarded to D.J.B., K.-H.W.L., and X.Q.

Supplementary Material

References

- Loftus EV., Jr Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504–1517. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrinton LJ, Liu L, Lafata JE, Allison JE, Andrade SE, Korner EJ, et al. Estimation of the period prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease among nine health plans using computerized diagnoses and outpatient pharmacy dispensings. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:451–461. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel MA, Neurath MF. New pathophysiological insights and modern treatment of IBD. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:571–583. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzoni G, Roda G, Belluzzi A, Roda E, Bagnara GP. Inflammatory bowel disease: Moving toward a stem cell-based therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4616–4626. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targan SR. Current limitations of IBD treatment: where do we go from here. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1072:1–8. doi: 10.1196/annals.1326.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantorna MT, Zhu Y, Froicu M, Wittke A. Vitamin D status, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, and the immune system. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80 suppl. 6:1717S–1720S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1717S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andoh A, Yagi Y, Shioya M, Nishida A, Tsujikawa T, Fujiyama Y. Mucosal cytokine network in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5154–5161. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg M, Lubel JS, Sparrow MP, Holt SG, Gibson PR. Review article: vitamin D and inflammatory bowel disease–established concepts and future directions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:324–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CY, Leung PS, Adamopoulos IE, Gershwin ME. The implication of vitamin D and autoimmunity: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013;45:217–226. doi: 10.1007/s12016-013-8361-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolders J, Damoiseaux J, Menheere P, Hupperts R. Vitamin D as an immune modulator in multiple sclerosis, a review. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;194:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg M, Lubel JS, Sparrow MP, Holt SG, Gibson PR. Review article: vitamin D and inflammatory bowel disease–established concepts and future directions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:324–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantorna MT. Vitamin D and its role in immunology: multiple sclerosis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2006;92:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penna G, Roncari A, Amuchastegui S, Daniel KC, Berti E, Colonna M, et al. Expression of the inhibitory receptor ILT3 on dendritic cells is dispensable for induction of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Blood. 2005;106:3490–3497. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger WW, Laban S, Kleijwegt FS, van der Slik AR, Roep BO. Induction of Treg by monocyte-derived DC modulated by vitamin D3 or dexamethasone: differential role for PD-L1. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:3147–3159. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeloe S, Nanzer A, Ryanna K, Hawrylowicz C. Regulatory T cells, inflammation and the allergic response-The role of glucocorticoids and Vitamin D. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;120:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantorna MT, Humpal-Winter J, DeLuca HF. Dietary calcium is a major factor in 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. J Nutr. 1999;129:1966–1971. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.11.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TT, Nestel FP, Bourdeau V, Nagai Y, Wang Q, Liao J, et al. Cutting edge: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. J Immunol. 2004;173:2909–2912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, Wenzel L, Tan BH, Krutzik SR, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita H, Sugimoto K, Inatomi S, Maeda T, Osanai M, Uchiyama Y, et al. Tight junction proteins claudin-2 and -12 are critical for vitamin D-dependent Ca2+ absorption between enterocytes. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1912–1921. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-09-0973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, Zhang Z, Musch MW, Ning G, Sun J, Hart J, et al. Novel role of the vitamin D receptor in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G208–G216. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00398.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Zhang H, Wu H, Li H, Liu L, Guo J, et al. Protective role of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 in the mucosal injury and epithelial barrier disruption in DSS-induced acute colitis in mice. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemire JM, Archer DC. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 prevents the in vivo induction of murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1103–1107. doi: 10.1172/JCI115072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantorna MT, Munsick C, Bemiss C, Mahon BD. 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol prevents and ameliorates symptoms of experimental murine inflammatory bowel disease. J Nutr. 2000;130:2648–2652. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.11.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll R, Matfin G. Endocrine and metabolic emergencies: hypercalcaemia. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2010;1:225–234. doi: 10.1177/2042018810390260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Mahon BD, Froicu M, Cantorna MT. Calcium and 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 target the TNF-alpha pathway to suppress experimental inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:217–224. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryz NR, Patterson SJ, Zhang Y, Ma C, Huang T, Bhinder G, et al. Active vitamin D (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) increases host susceptibility to Citrobacter rodentium by suppressing mucosal Th17 responses. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G1299–G1311. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00320.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff JP, Koszewski NJ, Haynes JS, Horst RL. Targeted delivery of vitamin D to the colon using β-glucuronides of vitamin D: therapeutic effects in a murine model of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G460–G469. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00156.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JS, Hewison M. Extrarenal expression of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1-hydroxylase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;523:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziennis S, Van Etten RA, Pahl HL, Morris DL, Rothstein TL, Blosch CM, et al. The CD11b promoter directs high-level expression of reporter genes in macrophages in transgenic mice. Blood. 1995;85:319–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Ito S, Nishio N, Cheng Z, Suzuki H, Isobe KI. Dextran sulphate sodium increases splenic Gr1(+)CD11b(+) cells which accelerate recovery from colitis following intravenous transplantation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;164:417–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04374.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm MC, Pullman WE, Bennett GM, Sullivan PJ, Pavli P, Doe WF. Direct evidence of monocyte recruitment to inflammatory bowel disease mucosa. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;10:387–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1995.tb01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko IK, Kim BG, Awadallah A, Mikulan J, Lin P, Letterio JJ, et al. Targeting improves MSC treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1365–1372. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlmark KR, Weiskirchen R, Zimmermann HW, Gassler N, Ginhoux F, Weber C, et al. Hepatic recruitment of the inflammatory Gr1+ monocyte subset upon liver injury promotes hepatic fibrosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:261–274. doi: 10.1002/hep.22950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beschorner R, Nguyen TD, Gözalan F, Pedal I, Mattern R, Schluesener HJ, et al. CD14 expression by activated parenchymal microglia/macrophages and infiltrating monocytes following human traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathol. 2002;103:541–549. doi: 10.1007/s00401-001-0503-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S. Targeting a monocyte subset to reduce inflammation. Circ Res. 2012;110:1546–1548. doi: 10.1161/RES.0b013e31825ec26d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurjus AR, Khoury NN, Reimund JM. Animal models of inflammatory bowel disease. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2004;50:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard CL, Elson CO, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. Reciprocal interactions of the intestinal microbiota and immune system. Nature. 2012;489:231–241. doi: 10.1038/nature11551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alex P, Zachos NC, Nguyen T, Gonzales L, Chen TE, Conklin LS, et al. Distinct cytokine patterns identified from multiplex profiles of murine DSS and TNBS-induced colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:341–352. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowat AM. Anatomical basis of tolerance and immunity to intestinal antigens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:331–341. doi: 10.1038/nri1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellon RK, Tonkonogy S, Schultz M, Dieleman LA, Grenther W, Balish E, et al. Resident enteric bacteria are necessary for development of spontaneous colitis and immune system activation in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5224–5231. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5224-5231.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomoyose M, Mitsuyama K, Ishida H, Toyonaga A, Tanikawa K. Role of interleukin-10 in a murine model of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:435–440. doi: 10.1080/00365529850171080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Kolachala V, Dalmasso G, Nguyen H, Laroui H, Sitaraman SV, et al. Temporal and spatial analysis of clinical and molecular parameters in dextran sodium sulfate induced colitis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi A, Sato T, Kamada N, Mikami Y, Matsuoka K, Hisamatsu T, et al. A single strain of Clostridium butyricum induces intestinal IL-10-producing macrophages to suppress acute experimental colitis in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:711–722. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasano A, Shea-Donohue T. Mechanisms of disease: the role of intestinal barrier function in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal autoimmune diseases. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:416–422. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering NA, Fromm M, Schulzke JD. Determinants of colonic barrier function in inflammatory bowel disease and potential therapeutics. J Physiol. 2012;590 Pt 5:1035–1044. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.224568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacke F, Randolph GJ. Migratory fate and differentiation of blood monocyte subsets. Immunobiology. 2006;211:609–618. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman D, Krishnan AV, Swami S, Giovannucci E, Feldman BJ. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:342–357. doi: 10.1038/nrc3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Baylink DJ, Sheng M, Wang H, Gridley DS, Lau KH, et al. Erythroid promoter confines FGF2 expression to the marrow after hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy and leads to enhanced endosteal bone formation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagishetty V, Misharin AV, Liu NQ, Lisse TS, Chun RF, Ouyang Y, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in mice impairs colonic antibacterial activity and predisposes to colitis. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2423–2432. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.