Abstract

Purpose

To understand the association between preconception stressful life events (PSLEs) and women's alcohol and tobacco use prior to and during pregnancy, and in the continuation of such use through pregnancy.

Methods

Data were from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort (n=9,350). Data were collected in 2001. Exposure to PSLEs was defined by indications of death of a parent, spouse or previous live born child; divorce or marital separation; or fertility problems prior to conception. Survey data determined alcohol and tobacco usage during the three months prior to and in the final three months of pregnancy. Weighted regressions estimated the effect of PSLEs on alcohol and tobacco use at each time point and on the continuation of use, adjusting for confounders.

Results

Experiencing any PSLE increased the odds of tobacco use prior to (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.23-1.87) and during pregnancy (AOR: 1.57. 95% CI: 1.19-2.07). Women exposed to PSLEs smoked nearly five additional packs of cigarettes in the 3 months prior to pregnancy (97 cigarettes, p=0.011) and consumed 0.31 additional alcoholic drinks during the last three months of pregnancy than unexposed women.

Conclusions

PSLEs are associated with tobacco use before pregnancy and alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy. Alcohol and tobacco screening and cessation services should be implemented prior to and during pregnancy, especially for women who have experienced PSLEs.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Preconception, Life course, Stress, Substance use

Introduction

Alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy are known risk factors for adverse birth outcomes including low birth weight and birth abnormalities, as well as fetal and infant death (Kesmodel et al. 2002; Patra et al. 2011; Rogers 2009). In 2012, 24.6 percent of US women aged 15 to 44 reported using tobacco and more than 50 percent reported drinking alcohol (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2013). While many women discontinue their alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy – perhaps due to the known deleterious consequences or social stigma of substance use during pregnancy - rates of alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy among US women have remained unacceptably high at 8.5% and 15.9% respectively (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2013). Reducing alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy may require the focus of cessation efforts to be shifted upstream to the preconception period, specifically targeted both to preventing the initiation of unhealthy alcohol and tobacco use, as well as to promoting the cessation of use prior to conception (Association of State and Territorial Health Officials 2013; US Surgeon General 2001; US Surgeon General 2005). Therefore, understanding the factors associated with alcohol and tobacco use before and during pregnancy, as well as disparities in alcohol and tobacco cessation during pregnancy, may be critical to improve intergenerational health outcomes.

Maternal stress may be an important factor in predicting substance use in the perinatal period. Theory suggests that some women use alcohol and tobacco to cope with stress (Niaura and Shiffman 1995), and previous clinic-based studies have found associations between perceived stress and tobacco use during pregnancy (Woods et al. 2010). Research has also demonstrated the health importance of exposure to stress across the lifecourse, particularly prior to conception, for both women and their children (Witt et al. 2014a; Witt et al. 2014b). However, no studies have examined how stressful life events prior to conception (PSLEs) influence the use of alcohol and tobacco immediately prior to and during pregnancy.

As such, this study sought to understand whether PSLEs affect women's health behaviors prior to and during pregnancy using a nationally representative, population-based sample. Specifically, this study examined whether and to what extent PSLEs are associated with tobacco or alcohol use in the three months prior to conception and with the continuation of tobacco and alcohol use through the final three months of pregnancy.

Materials and Methods

Data were from the first wave of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), a nationally-representative cohort of children born in 2001 and their parents. The ECLS-B used a clustered, list-frame design to select a probability sample of the approximately four million children born in 2001, with oversampling of children from minority groups, twins, and children born very low birthweight and low birthweight (United States Department of Education 2001). Children born to mothers under 15 years of age, those who were adopted after the birth certificate was issued, and those who did not survive up to 9 months of age were not included in the sampling frame (Snow et al. 2009). Registered births were sampled within primary sampling units (counties or groups of contiguous counties) from the National Center for Health Statistics vital statistics system. Over 14,000 births were sampled and contacted, and the final study cohort (consisting of completed nine month interviews) of 10,700 was formed in 2001 and 2002 when the children were approximately nine months old.

Restricted data was obtained with permission and approval from the Institute for Education Sciences (IES) Data Security Office of the US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). In accordance with NCES guidelines, all reported unweighted sample sizes were rounded to the nearest 50 (United States Department of Education 2001). The University of Wisconsin-Madison Health Sciences institutional review board considered this study exempt from review.

Participants were eligible for this study if the main survey respondent was the infant's biological mother (n=10,550); 450 additional records missing birth certificate data were subsequently excluded. ECLS-B included individual records for each child within twin pairs identified through oversampling; for this analysis, one twin was randomly selected from each pair to retain in the sample. For other multiples in the sample (i.e., not explicitly recruited as part of the oversampling), only one infant from the household was surveyed. The final sample contained 9,350 mother-child dyads, surveyed approximately 9 months after delivery.

Measures

Alcohol and tobacco use

Participants were asked about their alcohol and tobacco usage during the three months prior to pregnancy and in the final three months of pregnancy; responses were dichotomized as “any” versus “none.” Additionally, participants reported the total number of cigarettes smoked in an average day and the number of alcoholic drinks consumed in an average week both before and during pregnancy (alcohol use categories were operationalized ordinally at their midpoint). Continuation of use into pregnancy was derived from these variables.

Stressful life events prior to conception

The date of conception was derived using birth certificate data on the length of gestation and the infant's date of birth. Women were coded as having experienced a PSLE if they indicated that one or more of the following events occurred prior to conception: (1) death of the respondent's mother; (2) death of the respondent's father; (3) death of a previous live born child; (4) divorce; (5) separation from partner; (6) death of a spouse; or (7) fertility problems. All of these experiences were considered or operationalized as stressful life events in previous research (Holmes and Rahe 1967; Witt et al. 2014a; Witt et al. 2014b). Death of a previous live born child was collected from the birth certificate and was assumed to have occurred prior to conception.

Prenatal health and stress

Birth certificate data determined if women had experienced any of the following pregnancy complications: anemia; diabetes; (oligo) hydramnios; hypertension during pregnancy; eclampsia; incompetent cervix; Rh sensitization, uterine bleeding; premature rupture of membranes; placental abruption; or placenta previa. Birth certificate data also identified women who had previously delivered a preterm or small for gestational age (SGA) infant and women with chronic conditions (including: cardiac disease; lung disease; genital herpes; hemoglobinopathy; chronic hypertension; renal disease; or other medical risk factors). Prepregnancy body mass index (BMI [kilograms divided by meters squared]) was calculated from the respondent's measured height and self-reported weight prior to pregnancy (less than 18.5 kg/m2 [underweight]; between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2 [normal]; between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2 [overweight]; 30 kg/m2 or more [obese]; and unknown) (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute 2000). The timing of prenatal care initiation (first trimester; second or third trimester; or did not receive prenatal care) and whether women had a previous live birth (any versus none) was also evaluated. Women were coded as having experienced a stressful life event during pregnancy if they indicated that any of the following events occurred during their pregnancy: (1) death of the respondent's mother; (2) death of the respondent's father; (3) divorce; (4) separation from partner; or (5) death of a spouse.

Maternal sociodemographic factors

Maternal sociodemographic factors included: race/ethnicity (White [non-Hispanic]; Black [non-Hispanic]; Asian/Pacific Islander [non-Hispanic]; Hispanic; or other race [non-Hispanic]); age (15–19; 20–24; 25–29; 30–34; or 35 years or older); marital status at the infant's birth (married or living with partner; separated; divorced; widowed; or never married); health insurance coverage during pregnancy (no health insurance; any publicly funded insurance; or private health insurance coverage only); US region of residence (Northeast; Midwest; South; or West); and socioeconomic status (SES). SES was defined using a 5-category composite index (quintiles) generated by the NCES that incorporated: (1) father's or male guardian's education; (2) mother's or female guardian's education; (3) father's or male guardian's occupation; (4) mother's or female guardian's occupation; and (5) household income (United States Department of Education 2001).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted using survey procedures from SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC) and Stata SE 12 (College Station, TX). The standard errors were corrected due to clustering within strata and the primary sampling unit, and applied survey weights were used to produce estimates that accounted for the complex survey design, unequal probabilities of selection, and survey nonresponse.

Summary statistics were generated to describe sample characteristics; chi-square and Kruskall-Wallis tests determined significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics between women who did and did not experience any PSLE and by alcohol and tobacco use prior to and during pregnancy.

Four separate multivariable logistic regression models examined the impact of maternal exposure to PSLEs on the probability of any alcohol or tobacco use in the three months prior to pregnancy and in the final three months of pregnancy. Multivariable negative binomial regression examined the impact of maternal exposure to PSLEs on the mean number of alcoholic drinks ingested per week, and the mean number of cigarettes smoked per day. Using the results from the negative binomial model, marginal effects were used to estimate the total number of alcoholic drinks ingested and total number of cigarettes smoked during each 3 month period. Standard errors were estimated using the delta method (Agresti 2002).

To identify the predictors of the continuation of alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy, separate multivariable logistic regression models and multivariable negative binomial regression models examined the predictors of continued use of alcohol or tobacco among a subsample of women who used either alcohol or tobacco prior to pregnancy. All models adjusted for concurrent alcohol or tobacco use, maternal chronic conditions, pre-pregnancy BMI, parity, race/ethnicity, age, marital status at birth, health insurance coverage, SES and region of residence. Models examining substance use in the final three months of pregnancy (including those examining continuation of use) also adjusted for exposure to any stressful life event during pregnancy and the initiation of prenatal care.

Results

Alcohol Use

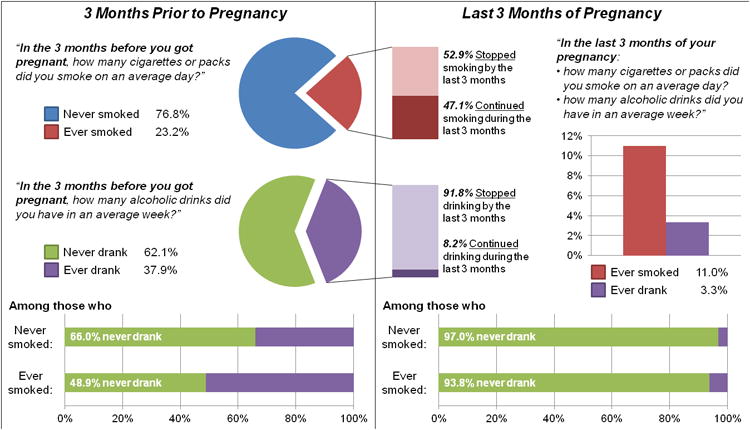

Nearly 38% of women reported any alcohol use in the 3 months prior to pregnancy, while 3.3 % of women reported any alcohol use in the final 3 months of pregnancy (Table 1, Figure 1). Drinking before and during pregnancy was significantly more frequent among women who experienced PSLEs (all p<0.01); however, women who experienced SLEs during pregnancy were less likely to drink during the final three months of pregnancy (p<0.001). Women in the highest SES quintile were the most likely to drink prior to pregnancy (53.3%) and during pregnancy (6.6%); while women aged 35 years and older drank the most drinks on average during pregnancy. Of women who drank prior to pregnancy, those who did not receive prenatal care were the most likely to continue drinking into pregnancy (26.5%).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics by Alcohol Use Prior to and During Pregnancy, Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort.

| Use in Three Months Prior to Pregnancy | Use in Final Three Months of Pregnancy | Continuation of Use in Final Three Months of Pregnancy | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Use | No. of Alcoholic Drinks | Alcohol Use | No. of Alcoholic Drinks | Alcohol Use | No. of Alcoholic Drinks | |||||||||||||||

| Total | None | Any | p-value | Mean | S.D. | p-value | None | Any | p-value | Mean | S.D. | p-value | Total | None | Any | p-value | Mean | S.D. | p-value | |

| TOTAL (weighted) | 3,774,441 | 2,342,509 | 1,431,932 | 12.1 | 31.3 | 3,648,209 | 126,232 | 0.5 | 5.2 | 1,431,932 | 1,314,936 | 1 16,996 | 1.4 | 7.9 | ||||||

| % | 100.0% | 62.1% | 37.9% | 96.7% | 3.3% | 37.9% | 91.8% | 8.2% | ||||||||||||

| TOTAL (unweighted) | 9,350 | 6,150 | 3,200 | 11.1 | 30.2 | 9,100 | 250 | 0.5 | 5.1 | 3,200 | 2,950 | 250 | 1.4 | 8.3 | ||||||

| Stress and Obstetric Factors | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Stressful Life Events Prior to Conception | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.085 | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| None | 80.3% | 63.1% | 36.9% | 11.8 | 31.4 | 97.0% | 3.0% | 0.4 | 3.4 | 78.2% | 92.4% | 7.6% | 1.0 | 5.3 | ||||||

| Any | 19.7% | 58.0% | 42.0% | 13.4 | 30.8 | 95.5% | 4.5% | 1.1 | 9.8 | 21.8% | 89.9% | 10.1% | 2.5 | 14.1 | ||||||

| Stressful Life Events During Pregnancy | 0.607 | 0.054 | <0.001 | 0.496 | 0.371 | 0.335 | ||||||||||||||

| None | 94.2% | 62.0% | 38.0% | 12.1 | 31.1 | 96.6% | 3.4% | 0.6 | 5.3 | 94.4% | 91.7% | 8.3% | 1.4 | 8.0 | ||||||

| Any | 5.8% | 63.2% | 36.8% | 13.2 | 35.4 | 97.7% | 2.3% | 0.3 | 4.2 | 5.6% | 94.1% | 5.9% | 0.8 | 6.9 | ||||||

| Maternal Chronic Conditions | 0.769 | 0.504 | 0.086 | 0.008 | 0.135 | 0.061 | ||||||||||||||

| None | 79.4% | 62.0% | 38.0% | 11.9 | 30.0 | 96.9% | 3.1% | 0.5 | 4.1 | 79.6% | 92.4% | 7.6% | 1.2 | 6.2 | ||||||

| Any | 20.6% | 62.4% | 37.6% | 13.1 | 36.7 | 95.6% | 4.4% | 0.9 | 8.7 | 20.4% | 89.7% | 10.3% | 2.2 | 13.3 | ||||||

| Prepregnancy Body Mass Index | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.016 | 0.027 | 0.013 | 0.016 | ||||||||||||||

| BMI <18.5 | 3.3% | 70.2% | 29.8% | * | 11.5 | 35.6 | 95.2% | 4.8% | 0.9 | 5.7 | 2.6% | 87.0% | 13.0% | 2.7 | 9.4 | |||||

| 18.5 ≤ BMI < 25 | 49.5% | 59.6% | 40.4% | *** | 13.2 | 33.4 | * | 95.9% | 4.1% | ** | 0.8 | 6.8 | ** | 52.7% | 90.3% | 9.7% | ** | 1.8 | 9.8 | |

| 25 ≤ BMI < 30 | 26.8% | 61.9% | 38.1% | 11.3 | 26.1 | 97.1% | 2.9% | 0.3 | 2.1 | ** | 26.9% | 93.1% | 6.9% | 0.8 | 3.2 | |||||

| BMI ≥ 30 | 17.9% | 64.8% | 35.2% | * | 11.8 | 34.1 | 98.1% | 1.9% | ** | 0.3 | 4.0 | * | 16.6% | 95.8% | 4.2% | ** | 0.8 | 6.5 | ||

| Unknown | 2.5% | 83.2% | 16.8% | *** | 3.8 | 14.3 | *** | 97.6% | 2.4% | 0.2 | 1.4 | ** | 1.1% | 85.6% | 14.4% | 1.1 | 3.2 | |||

| Initiation of Prenatal Care | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.049 | 0.286 | 0.073 | 0.064 | ||||||||||||||

| In the first trimester | 95.5% | 61.5% | 38.5% | *** | 12.1 | 30.9 | 96.6% | 3.4% | 0.6 | 5.3 | 96.9% | 91.8% | 8.2% | 1.4 | 8.0 | |||||

| In the second or third trimester | 4.2% | 73.4% | 26.6% | *** | 13.4 | 41.6 | 98.4% | 1.6% | * | 0.4 | 3.4 | 2.9% | 95.2% | 4.8% | 1.3 | 6.3 | ||||

| Did not receive prenatal care | 0.3% | 80.3% | 19.7% | * | 3.5 | 10.7 | *** | 94.8% | 5.2% | 0.3 | 1.8 | 0.2% | 73.6% | 26.5% | 1.7 | 4.2 | ||||

| Previous Live Birth | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.892 | 0.659 | 0.453 | 0.137 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 40.7% | 58.7% | 41.3% | 15.3 | 37.5 | 96.6% | 3.4% | 0.5 | 3.8 | 44.4% | 92.3% | 7.7% | 1.1 | 5.5 | ||||||

| No | 59.3% | 64.4% | 35.6% | 10.0 | 25.9 | 96.7% | 3.3% | 0.6 | 6.0 | 55.6% | 91.4% | 8.6% | 1.6 | 9.5 | ||||||

| Maternal Sociodemographic Factors | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| 15-19 | 7.5% | 82.0% | 18.0% | *** | 6.8 | 30.4 | ** | 99.3% | 0.7% | ** | 0.1 | 1.5 | *** | 3.5% | 96.6% | 3.4% | 0.4 | 3.6 | ||

| 20-24 | 24.2% | 66.4% | 33.6% | *** | 14.5 | 41.8 | ** | 97.9% | 2.1% | ** | 0.2 | 2.0 | *** | 21.5% | 94.7% | 5.3% | * | 0.6 | 3.4 | |

| 25-29 | 26.2% | 63.1% | 36.9% | 9.5 | 24.0 | *** | 97.6% | 2.4% | * | 0.4 | 3.9 | 25.5% | 94.4% | 5.6% | * | 1.0 | 6.0 | |||

| 30-34 | 25.0% | 56.5% | 43.5% | *** | 12.6 | 27.2 | 95.6% | 4.4% | ** | 0.7 | 7.2 | 28.6% | 90.2% | 9.8% | 1.6 | 9.8 | ||||

| 35+ | 17.1% | 53.7% | 46.3% | *** | 14.5 | 30.6 | * | 93.8% | 6.2% | *** | 1.1 | 7.4 | ** | 20.9% | 87.1% | 12.9% | *** | 2.4 | 9.9 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.061 | 0.593 | ||||||||||||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 57.4% | 53.4% | 46.6% | *** | 15.0 | 30.2 | *** | 95.6% | 4.4% | *** | 0.7 | 5.4 | ** | 70.4% | 91.0% | 9.0% | 1.5 | 7.7 | ||

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 14.1% | 70.5% | 29.5% | *** | 8.7 | 27.2 | *** | 98.2% | 1.8% | ** | 0.4 | 5.3 | 11.0% | 94.7% | 5.3% | 1.2 | 9.6 | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic) | 3.5% | 81.5% | 18.5% | *** | 4.3 | 32.6 | *** | 97.9% | 2.1% | * | 0.2 | 4.3 | ** | 1.7% | 90.5% | 9.5% | 1.2 | 9.1 | ||

| Other (non-Hispanic) | 2.5% | 53.5% | 46.5% | ** | 18.5 | 60.8 | * | 95.5% | 4.5% | 0.7 | 8.1 | 3.0% | 94.6% | 5.4% | 1.0 | 9.0 | ||||

| Hispanic | 22.6% | 76.7% | 23.3% | *** | 7.6 | 23.9 | *** | 98.2% | 1.8% | ** | 0.2 | 2.2 | ** | 13.9% | 93.4% | 6.6% | 0.8 | 4.4 | ||

| Marital Status (at birth) | 0.015 | 0.314 | 0.105 | 0.464 | 0.250 | 0.652 | ||||||||||||||

| Married or living with partner | 83.4% | 61.2% | 38.8% | ** | 11.8 | 29.4 | 96.5% | 3.5% | 0.6 | 5.3 | 85.3% | 91.6% | 8.4% | 1.4 | 7.9 | |||||

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 3.1% | 64.5% | 35.5% | 11.8 | 28.8 | 95.8% | 4.2% | 0.4 | 2.7 | 2.9% | 89.0% | 11.0% | 1.1 | 4.4 | ||||||

| Never married | 13.5% | 66.8% | 33.2% | ** | 14.3 | 42.2 | 97.9% | 2.1% | 0.4 | 5.1 | 11.8% | 94.4% | 5.6% | 1.2 | 8.7 | |||||

| Health Insurance Status | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.080 | 0.106 | ||||||||||||||

| Private Only | 59.1% | 55.4% | 44.6% | *** | 13.1 | 29.1 | * | 95.9% | 4.1% | *** | 0.7 | 6.1 | ** | 69.6% | 91.2% | 8.8% | 1.5 | 8.4 | ||

| Any Public | 37.4% | 71.6% | 28.4% | *** | 10.9 | 35.1 | 97.8% | 2.2% | *** | 0.3 | 3.6 | ** | 28.0% | 93.8% | 6.2% | 1.0 | 6.5 | |||

| None | 3.4% | 73.4% | 26.6% | ** | 8.6 | 25.9 | 96.7% | 3.3% | 0.2 | 1.5 | * | 2.4% | 87.6% | 12.4% | 0.9 | 2.7 | ||||

| Socioeconomic Status | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.006 | ||||||||||||||

| First quintile (lowest) | 19.7% | 78.0% | 22.0% | *** | 8.7 | 31.3 | *** | 98.2% | 1.8% | *** | 0.3 | 2.8 | ** | 11.4% | 93.0% | 7.0% | 1.1 | 5.6 | ||

| Second quintile | 20.0% | 69.6% | 30.4% | *** | 11.2 | 35.6 | 97.4% | 2.6% | 0.3 | 2.9 | * | 16.0% | 93.3% | 6.7% | 0.9 | 4.8 | ||||

| Third quintile | 20.1% | 62.7% | 37.3% | 13.0 | 34.5 | 97.9% | 2.1% | * | 0.4 | 4.2 | 19.7% | 95.0% | 5.0% | * | 1.0 | 6.7 | ||||

| Fourth quintile | 20.2% | 53.7% | 46.3% | *** | 13.2 | 26.2 | 96.4% | 3.6% | 0.7 | 7.6 | 24.6% | 92.3% | 7.7% | 1.6 | 10.4 | |||||

| Fifth quintile (highest) | 20.1% | 46.7% | 53.3% | *** | 14.4 | 27.6 | ** | 93.4% | 6.6% | *** | 1.0 | 6.4 | * | 28.2% | 87.9% | 12.1% | ** | 1.8 | 7.6 | |

| Region of Residence | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.035 | <0.001 | 0.200 | 0.007 | ||||||||||||||

| Northeast | 17.1% | 59.4% | 40.6% | 14.4 | 34.1 | * | 94.6% | 5.4% | * | 1.1 | 6.7 | 18.3% | 88.8% | 11.2% | 2.4 | 9.6 | ||||

| Midwest | 22.3% | 52.3% | 47.7% | ** | 14.8 | 33.3 | ** | 96.8% | 3.2% | 0.4 | 3.2 | 28.0% | 93.5% | 6.5% | 0.9 | 4.2 | ||||

| South | 36.9% | 66.1% | 33.9% | *** | 10.2 | 26.9 | ** | 97.5% | 2.5% | 0.3 | 3.2 | * | 32.9% | 92.6% | 7.4% | 1.0 | 5.2 | |||

| West | 23.8% | 66.8% | 33.2% | ** | 11.0 | 3.4 | 96.7% | 3.3% | 0.6 | 7.7 | 20.8% | 91.1% | 8.9% | 1.7 | 12.6 | |||||

Source: 2001 ECLS-B. Data are weighted percentages or means [SDs]. National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) rounding rules applied to unweighted Ns; unweighted subgroup Ns may not add to the total due to rounding error.

Subgroup post-hoc p-values:

P<0.05;

P<0.01;

P<0.001

Figure 1. Prevalence of Alcohol and Tobacco Use Before and During Pregnancy, Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort.

Source: 2001 ECLS-B. Data are weighted percentages.

In multivariable analyses, PSLEs were not significantly associated with the odds of drinking prior to or during pregnancy; however, women who experienced any PSLEs consumed more alcoholic drinks on average during pregnancy (0.31 drinks over 3 months, p=0.033; Table 3) than women without any PSLEs. SLEs during pregnancy were not associated with consumption of alcoholic drinks in the adjusted analyses.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics by Tobacco Use Prior to and During Pregnancy, Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort.

| Use in Three Months Prior to Pregnancy | Use in Final Three Months of Pregnancy | Continuation of Use in Final Three Months of Pregnancy | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarette Use | No. of Cigarettes Smoked | Cigarette Use | No. of Cigarettes Smoked | Cigarette Use | No. of Cigarettes Smoked | |||||||||||||||

| Total | None | Any | p-value | Mean | S.D. | p-value | None | Any | p-value | Mean | S.D. | p-value | Total | None | Any | p-value | Mean | S.D. | p-value | |

| TOTAL (weighted) | 3,774,441 | 2,897,428 | 877,013 | 280.6 | 691.0 | 3,360,625 | 413,816 | 88.4 | 393.8 | 877,013 | 463,673 | 413,339 | 380.2 | 740.3 | ||||||

| % | 100.0% | 76.8% | 23.2% | 89.0% | 11.0% | 23.2% | 52.9% | 47.1% | ||||||||||||

| TOTAL (unweighted) | 9,350 | 7,200 | 2,150 | 277.4 | 710.5 | 8,300 | 1,050 | 92.0 | 395.4 | 2,150 | 1,100 | 1,050 | 399.8 | 746.9 | ||||||

| Stress and Obstetric Factors | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Stressful Life Events Prior to Conception | 0.004 | 0.024 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| None | 80.3% | 77.6% | 22.4% | 269.1 | 672.1 | 89.9% | 10.1% | 80.5 | 388.7 | 77.5% | 55.2% | 44.8% | 358.7 | 759.6 | ||||||

| Any | 19.7% | 73.5% | 26.5% | 327.2 | 765.4 | 85.3% | 14.7% | 120.6 | 413.2 | 22.5% | 44.8% | 55.2% | 454.1 | 664.5 | ||||||

| Stressful Life Events During Pregnancy | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| None | 94.2% | 77.5% | 22.5% | 266.1 | 671.4 | 89.7% | 10.3% | 82.2 | 385.3 | 91.1% | 54.2% | 45.8% | 365.8 | 739.7 | ||||||

| Any | 5.8% | 64.1% | 35.9% | 517.6 | 924.3 | 78.1% | 21.9% | 189.6 | 503.3 | 8.9% | 38.9% | 61.1% | 527.7 | 729.1 | ||||||

| Maternal Chronic Conditions | 0.047 | <0.001 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 0.090 | 0.524 | ||||||||||||||

| None | 79.4% | 77.6% | 22.4% | 263.3 | 636.8 | 89.7% | 10.3% | 85.5 | 399.3 | 76.7% | 54.1% | 45.9% | 381.1 | 765.5 | ||||||

| Any | 20.6% | 73.6% | 26.4% | 347.5 | 887.7 | 86.5% | 13.5% | 99.7 | 361.9 | 23.3% | 48.9% | 51.1% | 377.3 | 613.6 | ||||||

| Prepregnancy Body Mass Index (BMI) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.099 | 0.265 | ||||||||||||||

| BMI <18.5 | 3.3% | 58.9% | 41.1% | *** | 538.6 | 967.9 | *** | 77.3% | 22.7% | *** | 166.6 | 439.4 | ** | 5.9% | 44.9% | 55.1% | 404.9 | 519.8 | ||

| 18.5 ≤ BMI < 25 | 49.5% | 77.3% | 22.7% | 262.1 | 645.6 | * | 88.9% | 11.1% | 82.0 | 361.0 | 48.3% | 51.0% | 49.0% | 361.3 | 671.4 | |||||

| 25 ≤ BMI < 30 | 26.8% | 78.6% | 21.4% | * | 265.2 | 692.9 | 91.4% | 8.6% | *** | 81.8 | 380.3 | 24.7% | 59.9% | 40.1% | 380.8 | 767.3 | ||||

| BMI ≥ 30 | 17.9% | 73.9% | 26.1% | ** | 329.5 | 759.6 | ** | 87.2% | 12.8% | * | 105.9 | 486.9 | 20.1% | 51.2% | 48.8% | 405.5 | 898.7 | |||

| Unknown | 2.5% | 90.6% | 9.4% | ** | 122.0 | 444.3 | *** | 95.4% | 4.6% | * | 58.6 | 290.0 | 1.0% | 51.2% | 48.8% | 625.8 | 773.7 | |||

| Initiation of Prenatal Care | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.075 | 0.201 | ||||||||||||||

| In the first trimester | 95.5% | 77.3% | 22.7% | *** | 272.7 | 681.2 | *** | 89.4% | 10.6% | *** | 84.8 | 391.3 | ** | 93.4% | 53.6% | 46.4% | 373.0 | 744.9 | ||

| In the second or third trimester | 4.2% | 66.4% | 33.6% | *** | 417.0 | 809.8 | ** | 81.2% | 18.8% | *** | 157.7 | 427.6 | ** | 6.0% | 43.9% | 56.1% | 469.3 | 636.2 | ||

| Did not receive prenatal care | 0.3% | 55.1% | 44.9% | * | 883.9 | 1520.9 | 68.5% | 31.5% | * | 275.3 | 607.3 | 0.6% | 29.8% | 70.2% | 613.8 | 676.3 | ||||

| Previous Live Birth | 0.041 | 0.974 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 40.7% | 75.2% | 24.8% | 275.5 | 615.2 | 91.3% | 8.7% | 56.8 | 253.1 | 43.5% | 64.9% | 35.1% | 228.9 | 452.3 | ||||||

| No | 59.3% | 77.8% | 22.2% | 284.1 | 740.0 | 87.5% | 12.5% | 110.2 | 467.4 | 56.5% | 43.6% | 56.4% | 496.6 | 901.2 | ||||||

| Maternal Sociodemographic Factors | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.470 | 0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| 15-19 | 7.5% | 70.4% | 29.6% | ** | 303.7 | 743.2 | 87.8% | 12.2% | 76.2 | 275.8 | 9.5% | 58.9% | 41.1% | 257.5 | 460.6 | ** | ||||

| 20-24 | 24.2% | 64.0% | 36.0% | *** | 439.6 | 790.7 | *** | 83.3% | 16.7% | *** | 132.8 | 516.4 | *** | 37.5% | 53.8% | 46.2% | 368.3 | 814.4 | ||

| 25-29 | 26.2% | 76.5% | 23.5% | 293.2 | 687.4 | 88.7% | 11.3% | 91.0 | 328.8 | 26.5% | 51.9% | 48.1% | 387.9 | 577.7 | ||||||

| 30-34 | 25.0% | 84.6% | 15.4% | *** | 176.9 | 561.3 | *** | 92.8% | 7.2% | *** | 67.2 | 405.9 | * | 16.5% | 53.2% | 46.8% | 435.6 | 938.1 | ||

| 35+ | 17.1% | 86.5% | 13.5% | *** | 177.3 | 643.7 | *** | 92.7% | 7.3% | *** | 57.9 | 297.0 | ** | 9.9% | 45.4% | 54.6% | 430.5 | 680.7 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 57.4% | 70.2% | 29.8% | *** | 380.7 | 675.8 | *** | 85.1% | 14.9% | *** | 124.8 | 397.0 | *** | 73.6% | 50.0% | 50.0% | *** | 417.8 | 675.4 | |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 14.1% | 82.8% | 17.2% | *** | 184.7 | 653.3 | *** | 92.1% | 7.9% | ** | 48.5 | 353.0 | *** | 10.4% | 54.3% | 45.7% | 282.4 | 835.2 | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic) | 3.5% | 92.8% | 7.2% | *** | 66.9 | 756.2 | *** | 98.8% | 1.2% | *** | 5.1 | 142.1 | *** | 1.1% | 82.8% | 17.2% | *** | 71.0 | 465.0 | *** |

| Other (non-Hispanic) | 2.5% | 59.8% | 40.2% | *** | 522.5 | 1648.7 | *** | 77.2% | 22.8% | *** | 217.5 | 1206.7 | * | 4.3% | 43.1% | 56.9% | *** | 541.8 | 1831.7 | |

| Hispanic | 22.6% | 89.1% | 10.9% | *** | 92.4 | 374.8 | *** | 97.0% | 3.0% | *** | 19.7 | 154.0 | *** | 10.6% | 72.2% | 27.8% | 180.9 | 475.2 | *** | |

| Marital Status (at birth) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.015 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Married or living with partner | 83.4% | 78.3% | 21.7% | *** | 263.2 | 676.8 | *** | 89.8% | 10.2% | *** | 85.5 | 389.4 | 78.0% | 53.0% | 47.0% | 393.1 | 748.5 | |||

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 3.1% | 70.2% | 29.8% | 443.1 | 807.3 | *** | 80.1% | 19.9% | *** | 182.9 | 487.4 | * | 3.9% | 33.1% | 66.9% | ** | 613.8 | 805.7 | * | |

| Never married | 13.5% | 68.9% | 31.1% | *** | 351.0 | 738.4 | 86.5% | 13.5% | * | 85.4 | 392.3 | 18.1% | 56.8% | 43.2% | 274.5 | 660.1 | ** | |||

| Health Insurance Status | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Private Only | 59.1% | 83.4% | 16.6% | *** | 180.8 | 555.0 | *** | 93.7% | 6.3% | *** | 53.1 | 362.6 | *** | 42.2% | 61.9% | 38.1% | *** | 320.0 | 810.4 | * |

| Any Public | 37.4% | 65.7% | 34.3% | *** | 445.7 | 857.6 | *** | 81.6% | 18.4% | *** | 144.4 | 436.1 | *** | 55.3% | 46.5% | 53.5% | *** | 420.4 | 659.7 | * |

| None | 3.4% | 83.0% | 17.0% | 197.8 | 535.4 | 90.0% | 10.0% | 87.3 | 381.1 | 2.5% | 42.0% | 58.0% | 509.6 | 815.6 | ||||||

| Socioeconomic Status | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| First quintile (lowest) | 19.7% | 71.4% | 28.6% | *** | 363.0 | 747.7 | *** | 82.7% | 17.3% | *** | 138.4 | 434.4 | *** | 24.2% | 39.5% | 60.5% | *** | 484.5 | 738.8 | ** |

| Second quintile | 20.0% | 65.4% | 34.6% | *** | 448.0 | 893.6 | *** | 82.7% | 17.3% | *** | 155.9 | 580.7 | *** | 29.8% | 50.3% | 49.7% | 449.1 | 925.3 | * | |

| Third quintile | 20.1% | 70.9% | 29.1% | *** | 345.2 | 685.6 | *** | 87.3% | 12.7% | ** | 89.4 | 302.7 | 25.1% | 56.3% | 43.7% | 307.3 | 489.6 | ** | ||

| Fourth quintile | 20.2% | 83.0% | 17.0% | *** | 182.8 | 561.0 | *** | 94.0% | 6.0% | *** | 46.0 | 336.0 | ** | 14.7% | 64.9% | 35.1% | *** | 270.7 | 739.1 | |

| Fifth quintile (highest) | 20.1% | 92.9% | 7.1% | *** | 66.6 | 369.1 | *** | 98.2% | 1.8% | *** | 14.0 | 159.8 | *** | 6.2% | 75.2% | 24.8% | *** | 196.3 | 491.3 | ** |

| Region of Residence | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.033 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Northeast | 17.1% | 74.9% | 25.1% | 298.5 | 673.0 | 88.1% | 11.9% | 84.0 | 287.1 | 18.5% | 52.7% | 47.3% | 334.0 | 482.2 | ||||||

| Midwest | 22.3% | 71.6% | 28.4% | 362.8 | 813.0 | *** | 85.3% | 14.7% | *** | 109.1 | 361.5 | 27.2% | 48.1% | 51.9% | 384.3 | 592.7 | ||||

| South | 36.9% | 76.1% | 23.9% | *** | 295.7 | 669.4 | 88.5% | 11.5% | 106.0 | 486.8 | 37.9% | 51.9% | 48.1% | 443.4 | 935.4 | |||||

| West | 23.8% | 83.9% | 16.1% | *** | 167.2 | 570.6 | *** | 94.1% | 5.9% | *** | 45.0 | 295.9 | *** | 16.4% | 63.0% | 37.0% | * | 279.7 | 685.1 | ** |

Source: 2001 ECLS-B. Data are weighted percentages or means [SDs]. National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) rounding rules applied to unweighted Ns; unweighted subgroup Ns may not add to the total due to rounding error.

Note: Bolded values indicate significantly significant group p-values. Subgroup post-hoc p-values:

P<0.05;

P<0.01;

P<0.001.

Number of cigarettes smoked refers to the number of cigarettes smoked during each 3 month period based on reported daily averages

Concurrent tobacco use was associated with higher odds of drinking both prior to and during pregnancy, as well as higher odds of continuation and a greater number of alcoholic drinks at both time points (Table 2). Women aged 30 years and older had higher odds of drinking during pregnancy and had higher odds of drinking continuation, compared to their younger (25-29 years) counterparts. Black, Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic women all had lower odds of drinking prior to pregnancy; however, only Asian/Pacific Islander women also had lower odds of drinking during pregnancy. Lower SES women had lower odds of drinking prior to and during pregnancy and tended to drink less (on average) than women in the highest SES quintile.

Table 2. Multivariable Regression Predicting Alcohol Use Prior to and During Pregnancy, Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort.

| Use in Three Months Prior to Pregnancy | Use in Final Three Months of Pregnancy | Continuation of Use in Final Three Months of Pregnancy | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Use (Any vs. None) | # of Alcoholic Drinks | Alcohol Use (Any vs. None) | # of Alcoholic Drinks | Alcohol Use (Any vs. None) | # of Alcoholic Drinks | |||||||||||||

| AOR | 95% CI | Mean # | SE | p-value | AOR | 95% CI | Mean # | SE | p-value | AOR | 95% CI | Mean # | SE | p-value | ||||

| Stress and Obstetric Factors | ||||||||||||||||||

| Stressful Life Events Prior to Conception | ||||||||||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Any | 1.09 | 0.92 | 1.29 | 1.12 | 0.97 | 0.250 | 1.14 | 0.82 | 1.60 | 0.31 | 0.14 | 0.033 | 1.07 | 0.74 | 1.54 | 0.63 | 0.36 | 0.083 |

| Stressful Life Events During Pregnancy | ||||||||||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||||

| Any | 0.50 | 0.21 | 1.18 | -0.35 | 0.25 | 0.165 | 0.55 | 0.23 | 1.31 | -0.86 | 0.62 | 0.163 | ||||||

| Concurrent Tobacco Use | ||||||||||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Any | 2.69 | 2.29 | 3.16 | 13.49 | 1.23 | <.001 | 2.99 | 1.80 | 4.97 | 0.81 | 0.20 | <.001 | 2.05 | 1.22 | 3.44 | 1.57 | 0.49 | 0.001 |

| Maternal Chronic Conditions | ||||||||||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Any | 0.93 | 0.83 | 1.06 | 0.05 | 0.85 | 0.950 | 1.30 | 0.89 | 1.90 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.083 | 1.36 | 0.89 | 2.08 | 0.52 | 0.32 | 0.098 |

| Prepregnancy Body Mass Index | ||||||||||||||||||

| BMI <18.5 | 0.67 | 0.46 | 0.98 | -2.71 | 1.99 | 0.175 | 1.43 | 0.64 | 3.24 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.281 | 1.85 | 0.75 | 4.55 | 1.82 | 1.23 | 0.139 |

| 18.5 ≤ BMI < 25 | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| 25 ≤ BMI < 30 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 1.09 | -1.39 | 0.95 | 0.143 | 0.71 | 0.46 | 1.10 | -0.37 | 0.10 | <.001 | 0.69 | 0.44 | 1.07 | -0.89 | 0.25 | <.001 |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 0.81 | 0.68 | 0.95 | -1.25 | 1.32 | 0.344 | 0.48 | 0.28 | 0.82 | -0.33 | 0.14 | 0.018 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.88 | -0.71 | 0.36 | 0.050 |

| Unknown | 0.42 | 0.28 | 0.62 | -7.09 | 2.75 | 0.010 | 0.73 | 0.27 | 1.94 | -0.48 | 0.13 | <.001 | 1.65 | 0.54 | 5.08 | -0.70 | 0.57 | 0.219 |

| Initiation of Prenatal Care | ||||||||||||||||||

| In the first trimester | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||||

| In the second or third trimester | 0.59 | 0.31 | 1.13 | -0.06 | 0.17 | 0.734 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 1.67 | 0.05 | 0.58 | 0.937 | ||||||

| Did not receive prenatal care | 0.66 | 0.03 | 12.75 | -0.37 | 0.31 | 0.236 | 4.70 | 0.41 | 54.26 | 0.43 | 1.22 | 0.722 | ||||||

| Previous Live Birth | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Yes | 0.68 | 0.60 | 0.77 | -4.57 | 0.85 | <.001 | 0.74 | 0.53 | 1.02 | -0.20 | 0.10 | 0.042 | 1.07 | 0.77 | 1.49 | -0.20 | 0.23 | 0.386 |

| Maternal Sociodemographic Factors | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 15-19 | 0.37 | 0.27 | 0.51 | -4.23 | 1.40 | 0.003 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.74 | -0.39 | 0.11 | 0.001 | 0.45 | 0.13 | 1.59 | -0.71 | 0.32 | 0.027 |

| 20-24 | 0.89 | 0.77 | 1.04 | 1.98 | 1.20 | 0.099 | 0.83 | 0.49 | 1.41 | -0.24 | 0.12 | 0.050 | 0.89 | 0.47 | 1.68 | -0.54 | 0.30 | 0.073 |

| 25-29 | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| 30-34 | 1.19 | 0.98 | 1.45 | 3.60 | 1.18 | 0.002 | 1.61 | 1.12 | 2.33 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.112 | 1.61 | 1.08 | 2.41 | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.150 |

| 35+ | 1.33 | 1.04 | 1.72 | 6.23 | 1.78 | <.001 | 2.15 | 1.27 | 3.65 | 0.63 | 0.26 | 0.014 | 2.15 | 1.29 | 3.57 | 1.38 | 0.59 | 0.018 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.98 | -2.23 | 1.51 | 0.138 | 0.64 | 0.36 | 1.13 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.983 | 0.72 | 0.39 | 1.33 | 0.40 | 0.51 | 0.435 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic) | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.31 | -9.01 | 0.85 | <.001 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.60 | -0.38 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.83 | 0.44 | 1.56 | -0.34 | 0.37 | 0.364 |

| Other (non-Hispanic) | 1.25 | 0.97 | 1.61 | 3.77 | 2.81 | 0.179 | 1.13 | 0.42 | 3.02 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.474 | 0.63 | 0.26 | 1.53 | -0.15 | 0.56 | 0.783 |

| Hispanic | 0.68 | 0.56 | 0.83 | -2.97 | 1.08 | 0.006 | 0.69 | 0.40 | 1.17 | -0.13 | 0.13 | 0.304 | 0.99 | 0.58 | 1.71 | -0.03 | 0.37 | 0.938 |

| Marital Status (at birth) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Married or living with partner | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 1.18 | 0.82 | 1.69 | 2.74 | 2.31 | 0.235 | 2.33 | 0.92 | 5.92 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.610 | 2.14 | 0.72 | 6.39 | 0.24 | 0.73 | 0.743 |

| Never married | 1.60 | 1.31 | 1.96 | 6.31 | 2.38 | 0.008 | 1.58 | 0.88 | 2.84 | 0.69 | 0.41 | 0.094 | 1.28 | 0.65 | 2.50 | 1.18 | 0.87 | 0.176 |

| Health Insurance Status | ||||||||||||||||||

| Private Only | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Any Public | 0.76 | 0.66 | 0.88 | -1.14 | 1.19 | 0.341 | 1.01 | 0.63 | 1.60 | -0.05 | 0.14 | 0.710 | 1.05 | 0.63 | 1.77 | -0.07 | 0.38 | 0.858 |

| None | 0.68 | 0.44 | 1.04 | -1.62 | 2.58 | 0.530 | 1.19 | 0.39 | 3.61 | -0.21 | 0.18 | 0.239 | 1.63 | 0.58 | 4.57 | -0.19 | 0.48 | 0.692 |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||||||||||||||||||

| First quintile (lowest) | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.41 | -7.64 | 1.69 | <.001 | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.80 | -0.56 | 0.26 | 0.030 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 1.65 | -0.76 | 0.62 | 0.216 |

| Second quintile | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.52 | -5.71 | 1.79 | 0.001 | 0.52 | 0.29 | 0.93 | -0.46 | 0.24 | 0.059 | 0.72 | 0.38 | 1.37 | -0.61 | 0.51 | 0.230 |

| Third quintile | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.61 | -4.53 | 1.55 | 0.004 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.71 | -0.47 | 0.25 | 0.057 | 0.46 | 0.21 | 0.98 | -0.67 | 0.55 | 0.227 |

| Fourth quintile | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.88 | -2.04 | 1.54 | 0.183 | 0.59 | 0.35 | 0.99 | -0.28 | 0.24 | 0.246 | 0.68 | 0.39 | 1.17 | -0.37 | 0.51 | 0.470 |

| Fifth quintile (highest) | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Region of Residence | ||||||||||||||||||

| Northeast | 1.01 | 0.76 | 1.34 | 0.54 | 1.66 | 0.745 | 1.18 | 0.64 | 2.18 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.251 | 1.07 | 0.54 | 2.10 | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.441 |

| Midwest | 1.34 | 1.01 | 1.77 | 0.85 | 1.56 | 0.587 | 0.75 | 0.47 | 1.19 | -0.17 | 0.16 | 0.289 | 0.69 | 0.42 | 1.11 | -0.62 | 0.40 | 0.116 |

| South | 0.88 | 0.68 | 1.14 | -2.45 | 1.62 | 0.130 | 0.67 | 0.41 | 1.10 | -0.21 | 0.13 | 0.111 | 0.75 | 0.45 | 1.24 | -0.52 | 0.35 | 0.144 |

| West | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

AOR-Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI-Confidence Interval; SE-Standard Error

Data are from the 2001 Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort (ECLS-B). All models account for complex sampling design of the ECLS-B.

Counts of number of alcoholic drinks and their statistical significance (p-values) were estimated using multivariable negative binomial regression. Marginal effects per week were calculated and were then multiplied by 13 to estimate the effect over the full 3 month period. Standard errors were calculated using the delta method and were then multiplied by 13.

Tobacco Use

Over 23% of women reported any cigarette use in the three months prior to pregnancy, while 11.0% of women reported any cigarette use in the final three months of pregnancy (Table 3, Figure 1). Smoking before and during pregnancy was significantly more frequent among women who experienced PSLEs and SLEs during pregnancy (all p<0.01); however, of women who smoked prior to pregnancy, only women who experienced SLEs during pregnancy were more likely to continue smoking into pregnancy (p<0.001). Women who did not receive prenatal care were the most likely to smoke prior to pregnancy (44.9%) and during pregnancy (31.5%); these women also had the highest rate of continuation between the two time points (70.2%) and smoked more cigarettes on average at each time point. The prevalence of smoking before and during pregnancy was lowest for women in the highest SES quintile (7.1%) and for Asian/Pacific Islander women (1.2%), respectively.

Women who experienced any PSLEs had higher odds of ever smoking prior to pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 1.52, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.23-1.87; Table 4) and smoked more prior to pregnancy on average (96.96 cigarettes over 3 months, p=0.011). These women also had higher odds of smoking during the last three months of pregnancy (AOR: 1.57. 95% CI: 1.19-2.07) compared to women who did not experience PSLEs. Women who experienced SLEs during pregnancy had higher odds of smoking during pregnancy (AOR: 2.06, 95% CI: 1.42-2.98) and smoked more during pregnancy on average (84.73 cigarettes over 3 months, p=0.001). Additionally, among women who smoked prior to pregnancy, women who experienced SLEs during pregnancy had higher odds of continuation of smoking into pregnancy (AOR: 1.99, 95% CI: 1.24-3.20) and smoked more on average during pregnancy (171.66 cigarettes over 3 months, p=0.018) compared to women who did not experience SLEs during pregnancy.

Table 4. Multivariable Regression Predicting Cigarette Use Prior to and During Pregnancy, Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort.

| Use in Three Months Prior to Pregnancy | Use in Final Three Months of Pregnancy | Continuation of Use in Final Three Months of Pregnancy | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarette Use (Any vs. None) | # of Cigarettes Smoked | Cigarette Use (Any vs. None) | # of Cigarettes Smoked | Cigarette Use (Any vs. None) | # of Cigarettes Smoked | |||||||||||||

| AOR | 95% CI | Mean # | SE | p-value | AOR | 95% CI | Mean # | SE | p-value | AOR | 95% CI | Mean # | SE | p-value | ||||

| Stress and Obstetric Factors | ||||||||||||||||||

| Stressful Life Events Prior to Conception | ||||||||||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Any | 1.52 | 1.23 | 1.87 | 96.96 | 38.19 | 0.011 | 1.57 | 1.19 | 2.07 | 18.41 | 18.45 | 0.318 | 1.17 | 0.86 | 1.59 | -27.81 | 55.72 | 0.618 |

| Stressful Life Events During Pregnancy | ||||||||||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||||

| Any | 2.06 | 1.42 | 2.98 | 84.73 | 24.99 | 0.001 | 1.99 | 1.24 | 3.20 | 171.66 | 72.79 | 0.018 | ||||||

| Concurrent Alcohol Use | ||||||||||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Any | 2.75 | 2.34 | 3.24 | 260.24 | 31.74 | <.001 | 3.01 | 1.80 | 5.04 | 118.73 | 56.20 | 0.035 | 4.69 | 2.40 | 9.16 | 268.44 | 124.19 | 0.031 |

| Maternal Chronic Conditions | ||||||||||||||||||

| None | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Any | 1.15 | 0.93 | 1.41 | 81.49 | 39.27 | 0.038 | 1.21 | 0.97 | 1.50 | 30.73 | 25.38 | 0.226 | 1.13 | 0.86 | 1.47 | 14.99 | 48.30 | 0.756 |

| Prepregnancy Body Mass Index | ||||||||||||||||||

| BMI <18.5 | 2.03 | 1.46 | 2.82 | 187.26 | 67.60 | 0.006 | 1.77 | 1.25 | 2.50 | 31.92 | 34.55 | 0.356 | 1.21 | 0.69 | 2.14 | 44.67 | 84.24 | 0.596 |

| 18.5 ≤ BMI < 25 | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| 25 ≤ BMI < 30 | 0.96 | 0.81 | 1.14 | 73.62 | 34.65 | 0.034 | 0.70 | 0.56 | 0.88 | -15.76 | 16.41 | 0.337 | 0.73 | 0.52 | 1.04 | -14.27 | 55.25 | 0.796 |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 1.19 | 0.99 | 1.43 | 163.76 | 48.22 | 0.001 | 0.99 | 0.79 | 1.24 | 39.82 | 19.98 | 0.046 | 1.08 | 0.81 | 1.44 | 74.13 | 51.16 | 0.147 |

| Unknown | 0.48 | 0.24 | 0.97 | -85.45 | 63.93 | 0.181 | 0.45 | 0.18 | 1.13 | -18.19 | 47.56 | 0.702 | 1.21 | 0.35 | 4.13 | 424.50 | 441.06 | 0.336 |

| Initiation of Prenatal Care | ||||||||||||||||||

| In the first trimester | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||||

| In the second or third trimester | 1.27 | 0.82 | 1.98 | 30.72 | 31.86 | 0.335 | 1.30 | 0.79 | 2.14 | 84.82 | 75.97 | 0.264 | ||||||

| Did not receive prenatal care | 2.10 | 0.65 | 6.84 | 159.20 | 169.60 | 0.348 | 1.87 | 0.41 | 8.54 | 146.79 | 257.88 | 0.569 | ||||||

| Previous Live Birth | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Yes | 0.97 | 0.82 | 1.15 | 15.45 | 33.22 | 0.642 | 1.50 | 1.15 | 1.95 | 82.25 | 21.72 | <.001 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.67 | 285.45 | 70.27 | <.001 |

| Maternal Sociodemographic Factors | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 15-19 | 1.06 | 0.76 | 1.46 | 12.21 | 55.83 | 0.827 | 0.75 | 0.48 | 1.16 | 3.32 | 29.54 | 0.910 | 0.83 | 0.50 | 1.39 | -51.18 | 72.19 | 0.478 |

| 20-24 | 1.35 | 1.10 | 1.65 | 67.74 | 37.31 | 0.069 | 1.07 | 0.84 | 1.36 | 31.10 | 20.06 | 0.121 | 0.92 | 0.65 | 1.28 | -12.84 | 43.66 | 0.769 |

| 25-29 | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| 30-34 | 0.69 | 0.54 | 0.89 | -51.20 | 40.42 | 0.205 | 0.84 | 0.59 | 1.19 | 3.68 | 20.37 | 0.857 | 1.21 | 0.73 | 2.02 | 119.49 | 86.54 | 0.167 |

| 35+ | 0.61 | 0.44 | 0.84 | -17.02 | 51.06 | 0.739 | 0.89 | 0.58 | 1.35 | 34.26 | 33.22 | 0.302 | 1.75 | 0.95 | 3.23 | 152.80 | 109.56 | 0.163 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.24 | -354.49 | 39.42 | <.001 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.26 | -160.50 | 35.31 | <.001 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.80 | -252.67 | 52.79 | <.001 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic) | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.38 | -342.06 | 39.12 | <.001 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.14 | -178.82 | 30.70 | <.001 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.44 | -376.58 | 39.52 | <.001 |

| Other (non-Hispanic) | 0.90 | 0.70 | 1.16 | 9.54 | 93.34 | 0.919 | 0.94 | 0.67 | 1.31 | 19.76 | 69.19 | 0.775 | 1.05 | 0.62 | 1.75 | 53.39 | 144.34 | 0.711 |

| Hispanic | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.21 | -421.48 | 30.45 | <.001 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.13 | -174.87 | 29.98 | <.001 | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.50 | -254.89 | 56.32 | 0.001 |

| Marital Status (at birth) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Married or living with partner | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 1.07 | 0.72 | 1.60 | 179.56 | 99.79 | 0.072 | 0.68 | 0.45 | 1.01 | 55.25 | 87.97 | 0.530 | 0.97 | 0.39 | 2.39 | 58.70 | 154.56 | 0.704 |

| Never married | 1.20 | 0.94 | 1.52 | 120.42 | 60.33 | 0.046 | 0.91 | 0.69 | 1.19 | 4.28 | 28.77 | 0.882 | 0.74 | 0.52 | 1.06 | -95.80 | 57.36 | 0.095 |

| Health Insurance Status | ||||||||||||||||||

| Private Only | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Any Public | 2.07 | 1.71 | 2.51 | 217.04 | 33.94 | <.001 | 2.15 | 1.63 | 2.85 | 65.69 | 18.67 | <.001 | 1.55 | 1.13 | 2.12 | 81.44 | 50.36 | 0.106 |

| None | 1.31 | 0.84 | 2.04 | -20.50 | 46.29 | 0.658 | 1.76 | 0.95 | 3.26 | 50.29 | 62.99 | 0.425 | 2.13 | 0.93 | 4.85 | 192.16 | 147.84 | 0.194 |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||||||||||||||||||

| First quintile (lowest) | 7.52 | 5.38 | 10.51 | 319.82 | 36.41 | <.001 | 16.73 | 9.20 | 30.42 | 150.20 | 33.28 | <.001 | 6.03 | 2.93 | 12.37 | 399.34 | 72.65 | <.001 |

| Second quintile | 7.73 | 5.49 | 10.89 | 387.04 | 37.86 | <.001 | 11.97 | 6.67 | 21.47 | 164.51 | 26.98 | <.001 | 3.69 | 1.96 | 6.95 | 307.59 | 62.14 | <.001 |

| Third quintile | 5.38 | 3.94 | 7.34 | 274.86 | 26.15 | <.001 | 8.08 | 4.67 | 14.00 | 85.63 | 14.39 | <.001 | 3.01 | 1.62 | 5.56 | 178.69 | 45.35 | <.001 |

| Fourth quintile | 2.56 | 1.89 | 3.47 | 142.65 | 30.49 | <.001 | 3.49 | 2.05 | 5.93 | 44.46 | 16.04 | 0.006 | 1.92 | 0.97 | 3.81 | 93.39 | 71.31 | 0.190 |

| Fifth quintile (highest) | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Region of Residence | ||||||||||||||||||

| Northeast | 1.68 | 1.24 | 2.27 | 119.97 | 53.30 | 0.024 | 1.72 | 1.07 | 2.76 | 10.50 | 27.73 | 0.705 | 1.38 | 0.83 | 2.30 | -25.76 | 82.40 | 0.755 |

| Midwest | 1.42 | 1.09 | 1.85 | 92.01 | 42.06 | 0.029 | 1.86 | 1.22 | 2.82 | 25.91 | 23.25 | 0.265 | 1.67 | 1.06 | 2.65 | 19.02 | 63.52 | 0.765 |

| South | 1.25 | 0.94 | 1.65 | 33.95 | 37.02 | 0.359 | 1.38 | 0.91 | 2.09 | 16.83 | 22.13 | 0.447 | 1.34 | 0.88 | 2.02 | 84.82 | 73.53 | 0.249 |

| West | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

AOR-Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI-Confidence Interval; SE-Standard Error

Data are from the 2001 Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort (ECLS-B). All models account for complex sampling design of the ECLS-B.

Counts of cigarettes and their statistical significance (p-values) were estimated using multivariable negative binomial regression. Marginal effects per day were calculated and were then multiplied by 90 to estimate the effect over the full 3 month period. Standard errors were calculated using the delta method and were then multiplied by 90.

Concurrent alcohol use was associated with higher odds of smoking both prior to and during pregnancy, as well as higher odds of continuation and a greater number of cigarettes smoked at both time points (Table 4). Black, Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic women all had lower odds of smoking both prior to and during pregnancy and smoked less on average compared to their white counterparts, while publicly insured women had higher odds of smoking and smoked more compared to privately insured women. There was a strong inverse relationship between SES and smoking such that lower SES women had substantially higher odds of smoking prior to and during pregnancy, smoked more on average and had higher odds of smoking continuation. Women living in the Northeast and Midwest had higher odds of smoking prior to and during pregnancy compared to women living in the West, but only women living in the Midwest had higher odds of smoking continuation into pregnancy.

Discussion

This is the first population-based study, to our knowledge, to determine if exposure to PSLEs are associated with women's tobacco and alcohol use prior to, during, and continuing into pregnancy. The findings from this study indicate that mothers who experienced any PSLE were more likely to use tobacco before pregnancy and both alcohol and tobacco during pregnancy. Among women who smoked prior to pregnancy, women who experienced SLEs during pregnancy were more likely to continue smoking in the third trimester of pregnancy. Furthermore, concurrent substance use was highly predictive of tobacco and alcohol use prior to, during, and continuing into pregnancy.

In this national study of US women, 37.9% reported using alcohol and 23.2% reported using tobacco in the three months prior to pregnancy. Although prenatal substance use was found to be far less prevalent, the fact that 49.0% of pregnancies in the US in 2001 were unintended (Finer and Henshaw 2006) suggests that many women may have used substances during the early first trimester before realizing they were pregnant, a critical period when many fetal organ systems form (Moore et al. 1988). The preconception period thus provides a crucial opportunity for clinicians to identify substance use in women of childbearing age and intervene before there are deleterious health consequences for women and their babies. A number of validated alcohol screening instruments and evidence-based alcohol and tobacco guidelines have been developed for clinical settings, and studies have shown that brief interventions designed to reduce alcohol and tobacco use in women of childbearing age are both feasible and effective (Floyd et al. 2008; US Surgeon General 2001). Growing evidence also indicates that preconception care can modify women's risky behaviors, such as tobacco and alcohol use (Xaverius and Salas 2013) and it may be advantageous to incorporate PSLEs into existing screening tools.

This study also identifies two important risk factors for the continuation of either alcohol or tobacco use into pregnancy: stressful life events during pregnancy and the concurrent use of both of these substances. These findings, which are corroborated by previous clinic-based studies (Harrison and Sidebottom 2009; Pirie et al. 2000; Zimmerman et al. 1990), suggest that women who report these risk factors may need targeted interventions to achieve cessation. Furthermore, previous clinic-based research has found that these two groups of women are also less likely to respond positively to cessation interventions, suggesting that integrated approaches that address both stress and concurrent substance use may be warranted (Pirie et al. 2000).

It is known that prenatal tobacco and alcohol consumption are important risk factors for adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight, premature birth, sudden infant death syndrome, and fetal alcohol syndrome (Cornelius and Day 2000; Dietz et al. 2010; Landesman-Dwyer 1982; Little and Wendt 1991; Yerushalmy 1971). The neonatal mortality and morbidity associated with these negative maternal health behaviors places a substantial economic strain on the US, both in terms of avoidable medical costs (Adams et al. 2002; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2002) and indirect costs to society (Bouchery et al. 2011). Given these considerable consequences, reducing the burden of alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy is one of the leading public health objectives. In fact, Healthy People 2020 outlines several objectives with the goal of reducing the prevalence of alcohol and tobacco use, particularly among reproductive aged adults and pregnant women (US Department of Health and Human Services and Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion 2013); and the Affordable Care Act requires that health plans provide universal alcohol and tobacco screening and cessation services for all adults, with expanded services for pregnant women (US Department of Health and Human Services 2010). Despite the fact that tobacco use and alcohol misuse screening and cessation counseling are considered to be particularly important and efficacious preventive health actions (The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2011), the prevalence of these negative health behaviors reported here and in other studies suggests that pervasive, long-term cessation among vulnerable populations has not been achieved through current efforts (Tong et al. 2013; US Preventive Services Task Force 2003; US Preventive Services Task Force 2004). As this study identified PSLEs as significant predictors of tobacco and alcohol use during pregnancy, it may be advantageous to incorporate PSLEs into existing screening tools in order to identify women who may require additional behavioral counseling interventions to reduce alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy. Further, as cessation often requires multiple attempts (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013), population-level interventions that are administered universally to reproductive aged women may demonstrate the greatest success at reducing these behaviors during pregnancy; alternatively, the use of PSLEs to identify high-risk reproductive aged women may be a particularly cost-effective way to utilize finite resources to tackle this important public health issue.

Several potential limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, women may have underreported their alcohol and tobacco use (both any use and the amount of use) prior to conception and during pregnancy (Ebert and Fahy 2007; Jacobson et al. 2002). However, the prevalence of alcohol and tobacco use prior to and during pregnancy is similar to other national estimates (Muhuri and Gfroerer 2009; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and Office of Applied Studies 2009). As few women reported using alcohol during pregnancy, these analyses may have been underpowered to detect effects for PSLEs on this health behavior. In addition, the ECLS-B collected categorical, rather than continuous, data on the exact numbers of alcoholic drinks. Therefore, estimates from the negative binomial models may not be precise. Analyses relied on self-reported data for factors like pre-pregnancy BMI, which may have biased the estimates in an unknown direction. The ECLS-B collected limited data on stressful life events and may not have comprehensively captured the spectrum of stressors some women experience, which might have resulted in misclassification.

Conclusion

This nationally-representative study shows that PSLEs are associated with increased tobacco use prior to and during pregnancy, as well as an increased amount of alcohol use during pregnancy among US women. The findings further suggest that the influence of PSLEs on health behaviors can last throughout a woman's pregnancy. Such results lend support for the call to implement alcohol and tobacco screening and cessation services prior to pregnancy, as these services may improve the long-term health of these vulnerable women and their children.

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by a Health Resources and Services Administrative (HRSA) (WPW, LEW, and DC: R40MC23625; PI: WP Witt) grant. Additional funding for this research was provided by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (KM and LEW: T32 HS00083; PI: M. Smith), the Health Disparities Research Scholars Program (FW: T32 HD049302; PI: G. Sarto), the 2012-2013 Herman I. Shapiro Distinguished Graduate Fellowship (LEW), and the Science and Medicine Graduate Research Scholars Fellowship from the University of Wisconsin in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and the School of Medicine and Public Health (ERC). ERC was additionally supported by a National Research Service Award institutional training grant (T32-HD075727) and LEW was supported by an AHRQ training grant (5T32HS000063-21) and the Thomas O. Pyle Fellowship.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams EK, Miller VP, Ernst C, Nishimura BK, Melvin C, Merritt R. Neonatal health care costs related to smoking during pregnancy. Health Econ. 2002;11:193–206. doi: 10.1002/hec.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. 2nd. JohnWiley & Sons; Hoboken: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Smoking Cessation Strategies for Women Before, During, and After Pregnancy: Recommendations for State and Territorial Health Agencies. Association of State and Territorial Health Officials; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchery EE, Harwood HJ, Sacks JJ, Simon CJ, Brewer RD. Economic Costs of Excessive Alcohol Consumption in the U.S., 2006. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs-United States, 1995-1999. MMWR. 2002;51:300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed February 2014];Workplace Health Promotion: Tobacco-Use Cessation. 2013 http://www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/implementation/topics/tobacco-use.html.

- Cornelius MD, Day NL. The effects of tobacco use during and after pregnancy on exposed children. Alcohol Research and Health. 2000;24:242–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz PM, England LJ, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Tong VT, Farr SL, Callaghan WM. Infant morbidity and mortality attributable to prenatal smoking in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert LM, Fahy K. Why do women continue to smoke in pregnancy? Women and Birth. 2007;20:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:90–96. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd RL, et al. The clinical content of preconception care: alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug exposures. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:S333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P, Sidebottom A. Alcohol and Drug Use Before and During Pregnancy: An Examination of Use Patterns and Predictors of Cessation. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:386–394. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0355-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967;11:213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson SW, Chiodo LM, Sokol RJ, Jacobson JL. Validity of maternal report of prenatal alcohol, cocaine, and smoking in relation to neurobehavioral outcome. Pediatrics. 2002;109:815–825. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesmodel U, Wisborg K, Olsen SF, Henriksen TB, Secher NJ. Moderate alcohol intake during pregnancy and the risk of stillbirth and death in the first year of life. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:305–312. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landesman-Dwyer S. Maternal drinking and pregnancy outcome. Appl Res Ment Retard. 1982;3:241–263. doi: 10.1016/0270-3092(82)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RE, Wendt JK. The effects of maternal drinking in the reproductive period: an epidemiologic review. J Subst Abuse. 1991;3:187–204. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(05)80036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KL, Persaud T, Torchia MG. The developing human: clinically oriented embryology. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC. Substance use among women: Associations with pregnancy, parenting, and race/ethnicity. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:376–385. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. The practical guide: identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Niaura R, Shiffman S. Overview of section I: psychological and biological mechanisms. In: Ferting J, Allen J, editors. Alcohol and Tobacco: From Basic Science to Clinical Practice. US Department of Health and Human Services; Public Health Service; National Institutes of Health; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Patra J, Bakker R, Irving H, Jaddoe VW, Malini S, Rehm J. Dose–response relationship between alcohol consumption before and during pregnancy and the risks of low birthweight, preterm birth and small for gestational age (SGA)—a systematic review and meta-analyses. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2011;118:1411–1421. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03050.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirie PL, Lando H, Curry SJ, McBride CM, Grothaus LC. Tobacco, alcohol, and caffeine use and cessation in early pregnancy. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JM. Tobacco and pregnancy. Reprod Toxicol. 2009;28:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow K, et al. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort (ECLS-B)Kindergarten 2006 and 2007 Data File User's Manual (2010-010) National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. The NSDUH report: Substance use among women during pregnancy and following childbirth. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 503: Tobacco Use and Women's Health. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2011;118:746–750. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182310ca9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong VT, Dietz PM, Morrow B, D'Angelo DV, Farr SL, Rockhill KM, England LJ. Trends in Smoking Before, During, and After Pregnancy—Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, United States, 40 Sites, 2000-2010. 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Education. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort, Nine-Month Data Collection. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; Washington, D.C: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed February 2014];Preventive Services Covered Under the Affordable Care Act. 2010 http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts/factsheets/2010/07/preventive-services-list.html.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling, interventions to prevent tobacco use tobacco-caused disease in adults pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement 2003 [Google Scholar]

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and Behavioral Counseling Interventions in Primary Care to Reduce Alcohol Misuse: Recommendation Statement. 2004 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Surgeon General. Women and smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. US Public Health Services, Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- US Surgeon General. Advisory on alcohol use in pregnancy. US Public Health Services, Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Witt WP, Cheng ER, Wisk LE, Litzelman K, Chatterjee D, Mandell K, Wakeel F. Maternal stressful life events prior to conception and the impact on infant birth weight in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2014a;104(Suppl 1):S81–89. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt WP, Cheng ER, Wisk LE, Litzelman K, Chatterjee D, Mandell K, Wakeel F. Preterm birth in the United States: the impact of stressful life events prior to conception and maternal age. Am J Public Health. 2014b;104(Suppl 1):S73–80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SM, Melville JL, Guo Y, Fan MY, Gavin A. Psychosocial stress during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:61.e61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xaverius PK, Salas J. Surveillance of preconception health indicators in behavioral risk factor surveillance system: emerging trends in the 21st century. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22:203–209. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerushalmy J. The relationship of parents' cigarette smoking to outcome of pregnancy—implications as to the problem of inferring causation from observed associations. Am J Epidemiol. 1971;93:443–456. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman RS, Warheit GJ, Ulbrich PM, Auth JB. The relationship between alcohol use and attempts and success at smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 1990;15:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]