Abstract

N-[2-(5-hydroxy-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]-2-oxopiperidine-3-carboxamide (HIOC) is a potent activator of the TrkB receptor in mammalian neurons and of interest because of its potential therapeutic uses. In the absence of a commercial supply of HIOC, we sought to produce several grams of material. However, a synthesis of HIOC has never been published. Herein we report the preparation of HIOC by the chemoselective N-acylation of serotonin, without using blocking groups in the key acylation step.

Keywords: amide, synthesis, chemoselectivity, decarboxylation, kinase, activation, serotonin

1. Introduction

Tropomyosin related kinase B (TrkB) is a neuronal transmembrane receptor protein in humans and other mammals. Small proteins such as brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF) bind to the extracellular portion of TrkB, triggering autophosphorylation of tyrosine residues in its intracellular domain. This phosphorylation then initiates cascade-signaling pathways known to promote neuronal differentiation and survival. Several small molecules have been identified as agonists of Trk receptors,2 including N-acetylserotonin (NAS, 2, Figure 1) as a TrkB activator.3 In the course of investigating the TrkB activity of other serotonin derivatives, N-[2-(5-hydroxy-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]-2-oxopiperidine-3-carboxamide (HIOC, 3) has displayed greater activation of TrkB, and exhibits a longer in vivo half-life than NAS.4 HIOC has also demonstrated protective activity in an animal model for light-induced retinal degeneration, and can pass the blood-brain and blood-retinal barriers.4 Thus, HIOC is a compound with high therapeutic potential, provided that this compound can be reliably prepared on a scale suitable for animal studies.

Figure 1. Structures of serotonin and derivatives, including HIOC (3).

Although HIOC (3) is described in patents,5 a method for its preparation has not been disclosed. Moreover, this compound is not consistently commercially available. Herein we describe a method for the gram-scale synthesis of HIOC.

At first glance, HIOC would appear to be trivially prepared from the N-acylation of serotonin (Figure 2). In practice, there are a number of plausible challenges:

serotonin can undergo acylation at three sites;

the carboxylic acid synthon 4 may potentially undergo decarboxylation upon standing; and

serotonin-HCl 1 and the carboxylic acid 4 both exhibit poor solubility in most organic solvents.

Figure 2. Retrosynthesis of HIOC.

2. Results and Discussion

Carboxylic acid synthon 4 was prepared by basic hydrolysis of the commercially available ethyl ester 5.6,7 However, the literature did not provide a method for isolating this water-soluble compound. After some optimization we found that treatment of ester 5 with KOH in water, followed by addition of concentrated HCl and saturation of the aqueous layer with solid NaCl allowed for extraction of the desired acid 4 with a solvent mixture of chloroform and isopropanol (Scheme 1).8

Scheme 1. Preparation and isolation of 2-oxo-3-piperidinecarboxylic acid (4).

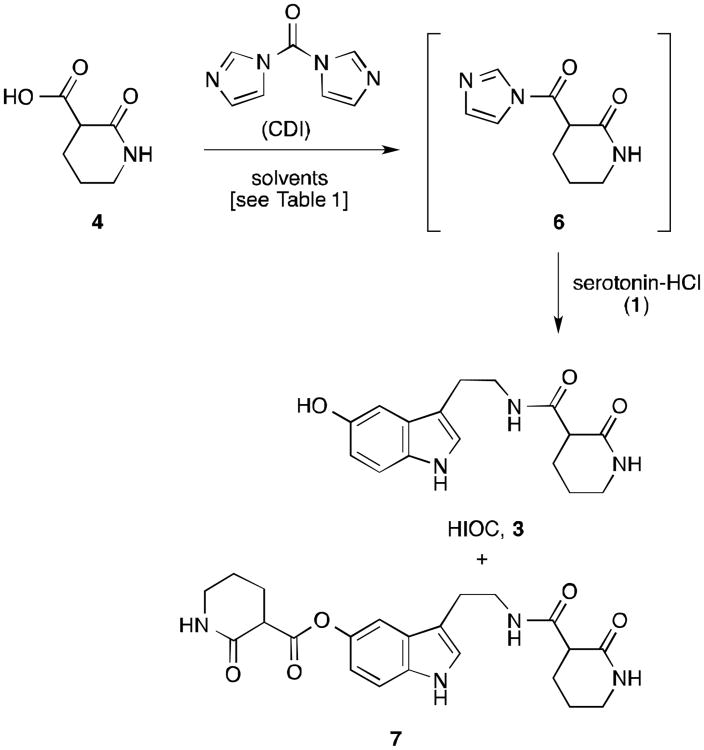

We initially attempted to couple the carboxylic acid 4 with serotonin-HCl (1) by activating the acid using carbodiimide reagents9 as well as through mixed anhydride formation.10 In the case of the carbodiimide reagents, a small amount of HIOC was detected via LC-MS, but could not be isolated. Attempts to activate 4 with methyl chloroformate furnished the methyl ester of 4 as the only identifiable product. Efforts using pivaloyl chloride were also unsuccessful, resulting only in pivaloylation of the primary amine of serotonin. After screening additional methods we found that the carboxylic acid could be activated with carbonyl diimidazole (CDI).11 Addition of CDI to an opaque suspension of carboxylic acid 4 in dichloromethane provided complete conversion to the soluble N-acyl imidazole derivative 6 (Scheme 2). Addition of serotonin-HCl (1) to intermediate 6 gave some conversion to the desired amide 3. This acylation procedure was plagued by the poor solubility of serotonin-HCl in CH2Cl2, and N,O-bisacylated product 7 was often observed from these heterogeneous reaction conditions, along with some recovered unacylated serotonin. However, dimethylformamide (DMF) solubilized all reaction components, giving 66% conversion to HIOC (3) after 3 hours, along with only 6% of the bisacylated product 7 (Table 1, entry 1). The product 3 was very difficult to extract from an aqueous acidic workup of the reaction mixture, so we sought an alternative to DMF as the solvent.

Scheme 2. Acylation of serotonin with carboxylic acid 4.

Table 1. Optimization of Reaction Conditions.

| Entry | solvents | conversion by 1H NMR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| serotonin-HCl (1) | HIOC (3) | 7 | ||

| 1 | DMFa | 25% | 66% | 6% |

| 2 | 1 : 1 CH2Cl2 : Et3Nb | 68% | 29% | 3% |

| 3 | 1 : 1 CH2Cl2 : pyridineb | 33% | 66% | <1% |

CDI was added to a 0.3 M solution of 4 in DMF. After 30 min, another volume of DMF was added followed by 1 equiv of 1.

CDI was added to a 0.3 M suspension of 4 in CH2Cl2. After aging 30 min, an equal volume of base (triethylamine or pyridine) was added, followed by 1 equiv of 1.

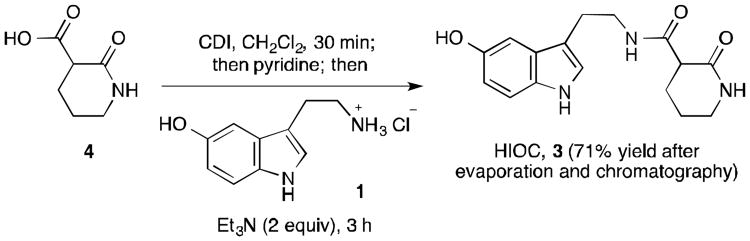

Adding an equal volume of triethylamine to the reaction mixture in CH2Cl2 prior to the addition of serotonin-HCl (1) gave some conversion to product, however the serotonin-HCl was not completely solubilized, leading to a small amount of bisacylated product 7 (entry 2). On the other hand, addition of an equal volume of pyridine (∼40 equivalents prior to addition of serotonin-HCl 1) resulted in a completely homogeneous reaction mixture (entry 3). After 3 hours, the reaction had proceeded to 66% conversion and high chemoselectivity favoring HIOC (3), with only a trace amount of N,O-bisacylated product detected by NMR.12 The addition of 2 equivalents of triethylamine helped to push the reaction to completion over the course of 3 hours, bringing the conversion up to ∼85% (Scheme 3). Isolation of the product from the reaction mixture was non-trivial. Concentration of the reaction mixture followed by dry loading of the unwieldy crude onto a silica gel column allowed for chromatographic separation with ethyl acetate/methanol (9 : 1) as eluent. The resulting solid was washed with hot diethyl ether to remove remaining imidazole impurities to furnish HIOC (3) in 71% yield (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Optimized acylation for the synthesis of HIOC (3).

In summary, we have developed a short, scalable, and highly reproducible synthesis of HIOC without the need for protective groups. The key discovery was the utility of the additional volume of pyridine to the acyl-imidazole species, which helped to solubilize the serotonin hydrochloride and also may have behaved as a nucleophilic catalyst.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by DoD W81XWH-12-1-0436, NIH R01EY004864, R01EY014026, P30EY006360, the Abraham J. and Phyllis Katz Foundation, and Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB). PMI is a recipient of the RPB Senior Scientific Investigator Award. We also thank Dr. Brooke Katzman (Emory University) for assistance with LC/MS.

Footnotes

In fond memory of Prof. Harry Wasserman, recognizing his humanity, scholarship, and service.

DoD Non Endorsement Disclaimer: The views, opinions and/or findings contained in this research are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Defense and should not be construed as an official DoD/Army position, policy or decision unless so designated by other documentation. No official endorsement should be made.

Supplementary Material: Experimental procedures, characterization data, 1H and 13C NMR spectra for 2-oxopiperidine-3-carboxylic acid (4) and HIOC (3).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.(a) Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:381–391. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:677–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Obianyo O, Ye K. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834:2213–2218. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Webster NJG, Pirrung MC. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9(Suppl 2):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-S2-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jang SW, Liu X, Pradoldej S, Tosini G, Chang Q, Iuvone PM, Ye K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3876–3881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912531107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen J, Ghai K, Sompol P, Liu X, Cao X, Iuvone PM, Ye K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:3540–3545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119201109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Tkachenko SE, Okun IM, Rivkis SA, Kravchenko DV, Khvat AV, Ivashchenko AV. Russ Pat. 2007 RU 2303597 C1 (CAN 147:181575) [Google Scholar]; (b) Ran R. Faming Zhuanli Shenqing. 2012 CN 102816103 A (CAN 158:105451) [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Shapiro D, Abramovitch RA. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:6690–6691. [Google Scholar]; (b) Narayanan K, Cook JM. J Org Chem. 1991;56:5733–5736. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Compound 4 (2-oxo-3-piperidinecarboxylic acid) is listed in the Sigma-Aldrich catalog, CBR01770. We determined that a commercial sample (lot# B00037799) was merely valerolactam, corresponding to decarboxylation of compound 4.

- 8.Continuous extraction of the salted aqueous layer with dichloromethane was also investigated, but tended to give reduced yields.

- 9.Basarab GS, Jordan DB, Gehret TC, Schwartz RS. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:4143–4154. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamada K, Teranishi S, Miyashita A, Ishikura M, Somei M. Heterocycles. 2011;83:2547–2562. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul R, Anderson GW. J Am Chem Soc. 1960;82:4596–4600. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The diminished yield of bisacylated product 7 relative to HIOC (3) may arise from pyridine-promoted transacylation of serotonin-derived esters, although this has not been proven.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.