Abstract

The present study asks how subliminal exposure to negative stereotypes about age-related memory deficits affects older adults’ memory performance. Whereas prior research has focused on the effect of “stereotype threat” on older adults’ memory for neutral material, the present study additionally examines the effect on memory for positive and negative words, as well as whether the subliminal “threat” has a larger impact on memory performance when it occurs prior to encoding or prior to retrieval (as compared to a control condition). Results revealed that older adults’ memory impairments were most pronounced when the threat was placed prior to retrieval as compared to when the threat was placed prior to encoding or no threat occurred. Moreover, the threat specifically increased false memory rates, particularly for neutral items compared to positive and negative ones. These results emphasize that stereotype threat effects vary depending upon the phase of memory it impacts.

Keywords: stereotype threat, aging, emotional memory, retrieval, encoding

An emerging body of research has demonstrated that age-related memory deficits (reviewed by Kausler, 1994; Kensinger & Corkin, 2003; Light, 1991) are exacerbated when older adults are reminded of general beliefs that aging impairs memory (e.g., Chasteen, Bhattacharyya, Horhota, Tam, & Hasher, 2005; Hess, Auman, Colcombe, & Rahhal, 2003; Hess, Hinson, & Statham, 2004), a phenomenon referred to as stereotype threat (Steele & Aronson, 1995). However, the mechanism by which stereotype threat disrupts older adults’ memory is poorly understood. Specifically, when does stereotype threat impair older adults’ memory, and what mechanisms are disrupted during the threat? Answering these questions will facilitate developing interventions that effectively reduce the pernicious outcomes of threat. In the current study, we investigated when threat affected memory by examining whether stereotype threat had a more pronounced impact on memory performance when it was introduced prior to encoding or when it was introduced prior to retrieval. We also investigated the mechanism by examining whether the threat disrupted automatic or controlled processes engaged in memory.

Stereotype threat refers to the notion that negative stereotypes about one’s social group (e.g., older adults) in a specific domain (e.g., memory performance) impair individual performance on related tasks (e.g., Steele & Aronson, 1995). For instance, when women are reminded of putative gender differences in math ability, they underperform on subsequent math tests (Spencer, Quinn, & Steele, 1999). Importantly, stereotype threat exacerbates older adults’ memory deficits (e.g., Hess et al., 2003; Hess et al., 2004; Thomas & Dubois, 2011). For instance, Hess and colleagues (2003) found that reminding older adults (but not young adults) that aging is associated with memory deficits impaired their subsequent performance on a recall test as compared to a control condition.

A key question that has emerged in stereotype threat and aging research is how stereotype threat disrupts older adults’ memory. Memory can be examined as three key processes: encoding, storage, and retrieval. When an individual fails to accurately remember information, this could be due to the fact that the information was not properly encoded or stored into memory. Alternatively, it could be due to the fact that the individual is unable to retrieve information from memory, despite the fact that it was encoded. Memory research demonstrates that there are distinct processes by which information is encoded and retrieved from memory (e.g., Nyberg, Cabeza, & Tulving, 1996; Tulving, Kapur, Craik, Moscovitz, & Houle, 1994). However, it remains an open question whether stereotype threat impairs memory by disrupting encoding or retrieval processes. The current study investigated this question.

The majority of studies that examine the effect of stereotype threat on older adults’ memory have introduced stereotype threat prior to encoding, and found that it negatively impacts subsequent memory (e.g., Chasteen et al., 2005, Experiment 3; Hess, Emery, & Queen, 2009; Hess et al., 2004). These studies cannot isolate the effects of threat to the encoding phase, however, because activating threat prior to encoding could not only disrupt encoding processes but also continue to disrupt processes at retrieval.

One of the key reasons it may be beneficial to determine whether stereotype threat disrupts encoding or retrieval processes is so that we may identify the mechanism by which threat reduces memory performance. Stereotype threat could impair memory performance in several different ways. For instance, stereotype threat could reduce attention during learning (thereby reducing the strength with which individual items are encoded). Alternatively, stereotype threat could reduce monitoring at retrieval by disrupting controlled processes.

Prior research examining the mechanism by which stereotype threat disrupts older adults’ memory performance has yielded mixed results. For instance, Hess and colleagues (2003) found that stereotype threat disrupted recall performance, and this effect was magnified when older adults were highly invested in their memory ability. The authors suggested that stereotype threat may trigger heightened anxiety or lowered expectations, although it remained an open question on whether those processes would disrupt attention during encoding, or monitoring processes at retrieval. However, emerging theories of stereotype threat suggest that it may disrupt controlled processes by shifting older adults’ mindset and motivations during the task (Barber & Mather, 2013; 2014). A few prior findings are consistent with this interpretation. Hess, Emery, and Queen (2009) found that older adults’ overall recollection declined only when they were given time constraints on the memory task to make their responses. The authors suggested that stereotype threat might disrupt retrieval under a time constraint because this speeded decision-making places increased demands on processing resources. Thus, stereotype threat might divert necessary cognitive resources away from the already cognitively demanding task, thereby resulting in diminished performance. Thomas and Dubois (2011) also presented suggestive evidence that stereotype threat disrupts controlled processes. Specifically, they found that introducing stereotype threat prior to retrieval increased the number of false alarms that older adults made toward lure items on a subsequent test. Because false memories have been widely associated with failures in monitoring (e.g. Kelley & Sahakyan, 2003; Roediger & McDermott, 1995), Thomas and Dubois’ finding suggests that stereotype threat may impair controlled (e.g., monitoring) processes during retrieval. Although these studies suggest that stereotype threat impairs memory by disrupting controlled processes, it remains an open question whether these processes are disproportionately disrupted during encoding or retrieval. Due to the fact that prior studies introduced the threat either prior to encoding (e.g., Hess et al., 2003), or prior to retrieval (e.g., Hess, Emery, & Queen, 2009; Thomas & Dubois, 2011), this question remains unanswered.

If stereotype threat disrupts controlled processes by reducing attention during encoding, then threat prior to encoding should have a larger impact on memory than threat prior to retrieval, and this impact may primarily be on the hit rates to studied items. If, however, stereotype threat disrupts controlled processes by disrupting monitoring processes at retrieval, then threat prior to retrieval should have the larger impact on memory, and this disruption could be revealed as an inflation of false alarm rates (because the threat would disrupt the memory-monitoring processes needed to reduce false alarms; Curran et al., 1997; Kelley & Sahakyan, 2003; Roediger & McDermott, 1995).

We also took an additional approach to examine how stereotype threat may disrupt controlled processes by examining the impact of threat on older adults’ memory for emotional information. Extensive research has demonstrated that emotional memory is relatively preserved with age (for review, see Kensinger, 2008), particularly when the emotional information is positively valenced (Mather & Carstensen, 2005). Older adults’ preferential retention of positive relative to negative information has been linked to controlled processes (Reed & Carstensen, 2012), and so if stereotype threat affects these controlled processes, it could affect older adults’ memory for this emotional information. The effect of the threat could also dissociate depending on whether it occurs prior to encoding or prior to retrieval. When placed prior to encoding, it could disrupt the controlled allocation of attention needed for the enhanced learning of positive relative to negative information (e.g., Mather & Knight, 2006). Alternatively, stereotype threat prior to retrieval could disrupt the processes that sometimes lead older adults to have a bias to endorse positive items as having been studied, which would result in fewer false alarms to positive as compared to negative items (e.g.. Spaniol, Voss, & Grady, 2008; Werheid, Gruno, Kathmann, Fischer, Almkvist, et al., 2010). By examining memory for emotional as well as neutral words, this study also extends previous research on stereotype threat, which has only examined the effect of threat on memory for neutral words (e.g., Hess et al., 2003; Hess et al., 2004; Horton, Baker, Pearce, & Deakin, 2008; Thomas & Dubois, 2011; but see Kang & Chasteen, 2009).

An additional consideration in understanding how stereotype threat disrupts older adults’ memory is the manner in which the threats are introduced (e.g., subliminally or supraliminally). Supraliminal cues may cause participants to actively invoke strategies to counteract the stereotype (e.g., Hess, Hinson, & Statham, 2004), which may make it harder to identify deficits when using that type of threat. Indeed, in the only study directly comparing the impact of supraliminal to subliminal threat cues introduced prior to encoding, Hess and colleagues (2004) found that subliminal threat cues caused greater memory decrements than supraliminal cues (but see Meisner, 2012). The current study therefore investigates the effect of stereotype threat (when introduced using subliminal cues prior to encoding or prior to retrieval) on older adults’ memory for positive, negative, and neutral information both as a function of threat placement and by examining the influence on hit rates and false alarm rates.

Methods

A total of 92 older adults (Mage = 75.1 years, SD = 6.8 years; 60 female) were recruited from the Boston area through newspaper advertisements to participate in the current study. They participated in exchange for monetary compensation. In addition, 77 young adults (Mage = 19.1 years, SD = 1.0 years; 42 female) were recruited from undergraduate populations to participate in the current study.1 All participants underwent a health screening to ensure they did not have a physical affliction that could affect cognitive function (e.g., untreated high blood pressure, history of stroke).

Task design

Threat placement (control, subliminal threat at encoding, and subliminal threat at retrieval) was manipulated between subjects such that each older or young adult completed the task under only one of three threat conditions. Regardless of condition, we assessed young and older adults’ memory for the same set of words (positive, negative, and neutral).

Materials

A total of 120 words were selected for the task. Words were chosen from the ANEW (Bradley & Lang, 1999) database. The list included 40 negative (Mvalence = 2.33, SD = .47), 40 positive (Mvalence = 7.82, SD = .36), and 40 neutral (Mvalence = 5.41, SD = .26) words. All words were matched for frequency and word length, and the positive and negative words were matched for arousal (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean valence and arousal ratings, word length, and frequencies for the positive, negative, and neutral words included in the task. SD in ().

| Valence | Arousal | Word length | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | 7.82 (.36) | 6.49 (.49) | 6.70 (1.54) | 25.25 (16.43) |

| Negative | 2.33 (.47) | 6.63 (.56) | 6.58 (1.36) | 25.08 (22.71) |

| Neutral | 5.41 (.26) | 3.87 (.37) | 6.65 (1.05) | 26.38 (22.30) |

Procedures

Encoding for all conditions

We split the list of 120 words into two lists of 60 words each (20 negative, 20 neutral, and 20 positive), which were created for the encoding task and counterbalanced across participants. The two lists were matched in valence, arousal, word frequency, and word length. None of the negative words were associated with age (e.g., death or bereavement). Prior to encoding in all conditions, participants were told that the task measured ability to process verbal information. During the encoding task, participants viewed each word for 3.5 seconds (see Hess, Emery, & Queen, 2009) in pseudorandom order. For each word, participants were instructed to indicate via buttonpress how frequently they encountered it in every day life (“daily”, “weekly”, “monthly”). All participants completed 10 practice trials with the experimenter prior to beginning the task.

Following the encoding task, participants had an approximate 15-minute delay in which they completed a variety of unrelated filler tasks, or a subliminal priming task that introduced the negative threat (for participants in the threat at retrieval condition only). None of the words presented in the delay tasks were the same as the words in the encoding task. The priming task is described in detail below.

Retrieval task for all conditions

Following the approximate 15-minute delay, participants completed the retrieval task. The retrieval task consisted of 120 words – the 60 words from the list participants had studied at encoding, and the 60 words from the list they had not previously studied. Participants were told that they would see words that they had either seen previously or new words they had not seen previously. Their task was to indicate, by buttonpress, whether a word had not been studied (“new”) or, if studied, whether they recollected details of its presentation (“remember”) or only recognized it as being familiar (“know”). This Remember-Know paradigm asked participants to distinguish memories associated with episodic detail (Remember) from those associated with only familiarity (Know; e.g., Hess, Emery, & Queen, 2009; see Yonelinas, 2002, for a review of this distinction and Kensinger & Corkin, 2003 for discussion of how these processes are affected by emotion).

Participants were given 3.5 seconds to respond to each word (see Hess, Emery, & Queen, 2009). For all participants, a response was recorded for at least 95% of the trials.

Control condition

The main goal of the control task was to ensure that negative age-related stereotypes pertaining to memory were not activated during the task. We took several measures to ensure this. In the older adult condition, we had two older adult volunteers (one male, 69, and one female, 67) recruit and test the majority of the participants in the control task2 in order to reduce the likelihood that we would activate the threat (e.g., Inzlicht & Ben-Zeev, 2000; Kang & Chasteen, 2009; Sekaquaptewa and Thompson, 2003). In the young adults condition, we had three young adult experimenters (all female, ranging from 19 to 23) recruit and test the participants. The task instructions were the same for both older and young adult participants in the control task (see encoding task methods above).

Subliminal priming conditions for either encoding or retrieval

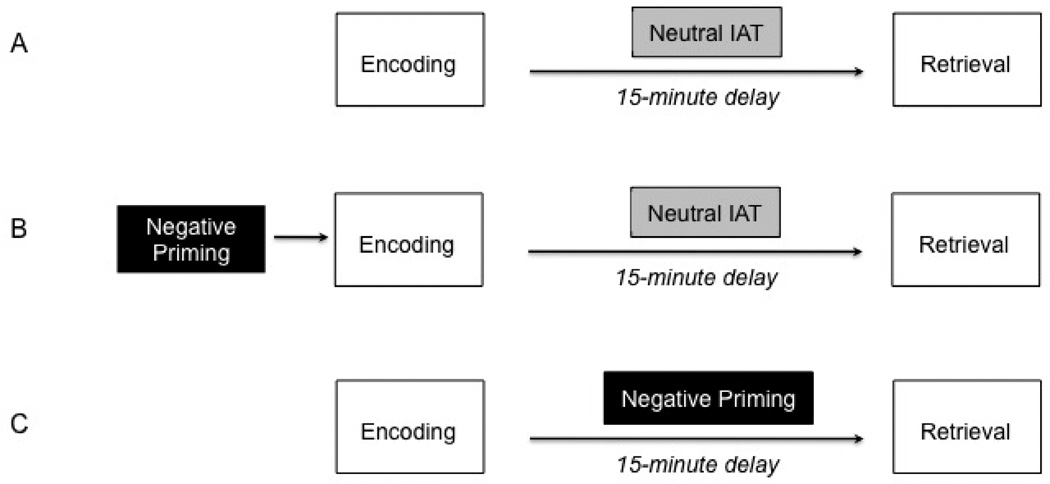

The instructions prior to encoding and retrieval in the subliminal task were the same as those used in the control task. All older adult participants in the subliminal priming conditions were tested by a young adult. Stereotype threat was induced by subliminally presenting participants with negative age-related stereotype words (see below for examples) and pronounceable nonwords (e.g., chugbott; e.g., Hess et al. 2004; Experiment 2). In the subliminal threat at encoding condition, the priming task took place immediately prior to the encoding task. In the subliminal threat at retrieval condition, participants were primed immediately prior to the retrieval task (see Figure 1 for graphical representation of this task).

Figure 1.

A graphical representation of (A) the control task; (B) the subliminal threat at encoding task; and (C) the subliminal threat at retrieval task. The task design was the same for both older and younger participants.

The priming task was the same in the threat at encoding and threat at retrieval conditions. For each trial of the priming task, participants viewed a fixation point (+) in the center of the screen for 1000 ms, followed immediately by a word that was presented anywhere from 17 ms to 50 ms (presentation rates were determined on an individual basis during a pre-test). The word was masked by a string of consonants for 250 ms, and then was replaced by a prompt asking participants if they had just seen a word or a nonword (participants responded via keypress). The priming task consisted of three sets of 30 trials. Each of the three sets consisted of 14 pronounceable nonwords and 16 negative aging-related words (e.g., feeble, complaining, confused, forgot, senile). The first three trials of each set consisted of the words “aged”, “old”, and “senior” in order to facilitate the association between the negative adjectives and aging. Upon completion of the task, the experimenter verified that none of the participants were consciously aware of any of the words they had seen (none were).

Results

Data from 10 older adults were excluded from analyses because they did not make any “know” responses throughout the entire recognition task, which suggested an inability to follow the task instructions. This left 28 older adults and 25 young adults in the subliminal encoding condition, 30 older adults and 25 young adults in the subliminal retrieval condition, and 24 older adults and 27 young adults in the control condition.

Corrected recognition

All responses were transformed to corrected recognition scores, which were computed by subtracting the false alarm rate (saying “remember” or “know” to a new item) from the hit rate (saying “remember” or “know” to an old item). These were calculated separately for each valence condition.

Effect of threat placement on corrected recognition for young and older adults

In order to determine whether threat placement (control, threat at encoding, threat at retrieval) impaired memory for positive, negative, and neutral words, we conducted a 2 (age: young adults or older adults) × 3 (threat placement: control, threat at encoding, threat at retrieval) × 3 (valence: negative, neutral, positive) mixed model ANOVA with valence as a repeated measure and corrected recognition as the dependent variable. Our results demonstrated a main effect of age (F(1,153) = 37.30, p < .001, η2partial = .20), a main effect of valence (F(2,306) = 70.52, p < .001, η2partial = .32), and an age × threat placement interaction (F(2,153) = 5.03, p < .01, η2partial = .06). There was no main effect of threat placement (F(2,153) = 1.61, p = .20, η2partial = .02), nor was there a valence × threat placement interaction (F < 1; η2partial < .01), valence × age interaction (F(2,306) = 1.34, p = .26, η2partial < .01), or valence × threat placement × age interaction (F(2,306) = 1.99, p = .10, η2partial = .03).

The main effect of age emerged because young adults had overall higher corrected recognition as compared to older adults (MYoung adults = .68, SD = .15; MOlder adults = .52, SD = .18; t(157) = 6.12, p < .001). The main effect of valence emerged because, collapsed across groups, neutral and positive words were remembered more accurately than negative words (t(158) = 11.06, p < .001 and t(158) = 8.38, p < .001, respectively).

To more closely examine the age × threat placement interaction, we conducted two linear contrasts (one for young adults and one for older adults) to examine the effects of threat placement (control, threat at encoding, threat at retrieval) on memory performance. Results revealed a significant linear contrast for older adults (F(1,81) = 10.42, p < .005), but not for young adults (F(1,76) = 1.23, p = .27). A closer examination of these results demonstrated that memory performance for older adults was lower in the threat at retrieval condition (M = 0.44, SD = 0.18) as compared to the threat at encoding condition, (M = 0.54, SD = 0.16; t(56) = 2.25, p < .03) or to the control condition (M = 0.59, SD = 0.17; t(52) = 3.13, p < .005).3 See Table 2 for means and SDs.

Table 2.

Corrected recognition, hits, and false alarms for positive, negative, and neutral words for older adults and young adults when there was no threat (control), or the threat was introduced prior encoding or prior to retrieval. SD in ().

| Control | Threat at encoding | Threat at retrieval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older adults | Corrected Recognition | Positive | .64 (.19) | .58 (.19) | .44 (.26) |

| Negative | .47 (.19) | .45 (.20) | .40 (.13) | ||

| Neutral | .66 (.20) | .59 (.20) | .49 (.26) | ||

| Hits | Positive | .78 (.18) | .83 (.13) | .76 (.18) | |

| Negative | .79 (.17) | .79 (.14) | .81 (.12) | ||

| Neutral | .68 (.16) | .68 (.18) | .67 (.21) | ||

| False alarms | Positive | .15 (.15) | .25 (.22) | .33 (.21) | |

| Negative | .31 (.15) | .35 (.19) | .42 (.15) | ||

| Neutral | .09 (.12) | .16 (.14) | .24 (.17) | ||

| Young adults | Corrected Recognition | Positive | .68 (.20) | .71 (.19) | .75 (.12) |

| Negative | .55 (.21) | .59 (.17) | .56 (.18) | ||

| Neutral | .73 (.16) | .75 (.16) | .78 (.10) | ||

| Hits | Positive | .86 (.11) | .86 (.13) | .85 (.10) | |

| Negative | .86 (.11) | .82 (.16) | .80 (.13) | ||

| Neutral | .78 (.14) | .84 (.10) | .85 (.09) | ||

| False alarms | Positive | .18 (.15) | .15 (.17) | .10 (.10) | |

| Negative | .31 (.16) | .24 (.20) | .24 (.15) | ||

| Neutral | .05 (.09) | .10 (.13) | .07 (.06) |

Effect of threat placement on hits and false alarms for young and older adults

Because corrected recognition reflects the subtraction of false alarms from the hit rates, we next examined whether threat placement affected the overall hits and/or the proportion of false alarms.

In order to do this, we first examined whether threat placement affected the hit rate using a 2 (age: young adults or older adults) × 3 (threat placement: control, threat at encoding, threat at retrieval) × 3 (valence: positive, negative, neutral) mixed-model ANOVA. The results revealed a main effect of age (F(1,153) = 19.25, p < .001, η2partial = .11) and valence (F(2,306) = 20.59, p < .001, η2partial = .12), but no main effect of threat placement (F < 1, η2partial < .01). There also was an age × valence interaction (F(2,306) = 12.64, p < .001, η2partial = .08), but no valence × threat placement interaction (F(4,306) = 1.28, p = .28, η2partial < .02) or age × threat placement interaction (F < 1, η2partial < .01). The three-way interaction (F(4,306) = 2.58, p = .04, η2partial = .03) did not meet our modified threshold for significance (p < .03)1.

The main effect of age emerged because older adults had fewer hits than did young adults (MOlder adults = .75, SD = .13; MYoung adults = .83, SD = .10; t(157) = 4.44, p < .001). The effect of valence emerged because, collapsed across all conditions, hits were greater for emotional items (positive and negative) as compared to neutral items (t(158) = 5.94, p < .001; t(158) = 4.46, p < .001, respectively), and memory performance did not differ between positive and negative items (t(158) = 1.01, p = .31). In order to examine the age × valence interaction, we first conducted two separate ANOVAs (one for older adults and one for young adults) with valence (positive, negative, and neutral) as a within subject factor. Results revealed a main effect of valence for older adults (F(2,162) = 26.39, p < .001, η2partial = .25), but not young adults (F(2,152) = 2.50, p = .09, η2partial = .03). Only older adults had a higher hit rate for emotional items (positive and negative) as compared to neutral items (t(81) = 5.95, p < .001 for both), with no difference between positive and negative items (t < 1, p = .76).

Next, we examined whether threat placement affected the proportion of false alarms using a 2 (age: young adults or older adults) × 3 (threat placement: control, threat at encoding, threat at retrieval) × 3 (valence: positive, negative, neutral) mixed-model ANOVA. When the proportion of false alarms was the dependent variable, results revealed a main effect of age (F(1,153) = 19.31, p < .001, η2partial = .11) and valence (F(2,306) = 167.23, p < .001, η2partial = .52), but no main effect of threat placement (F(2,153) = 1.70, p = .19, η2partial = .02). However, we also found an age × threat placement interaction (F(2,153) = 5.90, p < .005, η2partial = .07) and a valence × threat placement interaction (F(4,306) = 2.82, p < .03, η2partial = .04), but no age × valence interaction (F < 1, η2partial < .01). There was a moderate three-way interaction (F(4,306) = 2.26, p = .06, η2partial = .03), but it did not meet our modified threshold for significance (p < .03).1

Overall, older adults had significantly more false alarm than did young adults (MOlder adults = .26, SD = .16; MYoung adults = .16, SD = .12; t(157) = 4.46, p < .001), which resulted in the main effect of age. In order to more closely examine the valence × threat placement interaction, we conducted separate one-way ANOVAs for the false alarms in each of the three valence types (positive, negative, and neutral), collapsed across age group. Results revealed a significant main effect only for neutral words (F(2,158) = 6.33, p < .005), but not negative (F < 1, p = .48) or positive words (F(2,158) = 1.23, p = .29). For neutral words, there were fewer false alarms in the control condition as compared to both threat at retrieval (t(104) = 3.59, p < .005) and threat at encoding (t(102) = 2.41, p < .02); the false alarm rates in the two threat conditions did not differ (t(106) = 1.20, p = .23).

We examined the age × threat placement interaction for false alarms by conducting separate linear contrasts (one for young adults and one for older adults) where threat placement (control, threat at encoding, threat at retrieval) was the between subject variable. Here we collapsed across valence. Results revealed a significant linear contrast as a function of threat placement for older adults (F(1,81) = 12.06, p < .005), but not for young adults (F(1,76) = 1.51, p = .22). For older adults, threat only moderately increased the number of false alarms when placed prior retrieval as compared to when it was placed prior to encoding (t(56) = 1.80, p = .08), but threat before retrieval significantly increased the false alarm rate as compared to the control condition; t(52) = 3.75, p < .001. See Table 2 for means and SDs.

Discussion

Together, these findings are consistent with previous findings that stereotype threat impairs memory for older, but not young, adults (e.g., Hess et al., 2003; Hess et al., 2004; Hess & Hinson, 2006; Horton et al., 2010; Thomas & Dubois, 2011), but extends this line of research by demonstrating that stereotype threat had the most deleterious effect on older adults’ memory when the threat occurred before retrieval, as compared to when it occurred prior to encoding. Consistent with the effect of threat on retrieval processes, the threat increased false memory rates; this was particularly true for neutral items compared to positive and negative ones.

Our findings that memory deficits were driven largely by a higher proportion of false alarms and that these deficits were largest in older adults when the threat was introduced prior to retrieval, suggest that stereotype threat disrupts controlled processes implemented during retrieval. It has been widely shown that increases in false alarms are associated with decreased monitoring at the time of retrieval (e.g., Curran, Schacter, Norma, & Galluccio, 1997; Kelley & Sahakyan, 2003; Roediger & McDermott, 1995). For instance, Curran and colleagues (1997) found that a patient with frontal lobe impairments (which disrupted monitoring) had significantly higher false alarm rates than controls. Indeed, neuroimaging studies have also demonstrated that false memories are attributed to deficits in monitoring processes (in the prefrontal cortex) during retrieval (e.g., Cabeza, Rao, Wagner, Mayer, & Schacter, 2001; Schacter, Buckner, Koustaai, Dale, & Rosen, 1997).

However, despite the fact that introducing threat at retrieval showed the greater disruption to older adults’ memory by increasing the proportion of their false alarms, it did not disproportionately affect older adults’ memory for emotional information. We had hypothesized that when placed prior to retrieval, stereotype threat could reduce older adults’ proportion of false alarms to positive as compared to negative items (e.g.. Spaniol, Voss, & Grady, 2008; Werheid, Gruno, Kathmann, Fischer, Almkvist, et al., 2010). This was not the case. In fact, we did not find a significant age × threat placement × valence interaction for corrected recognition, hits, or false alarms. Indeed, we only found a valence × threat placement interaction for false alarms.3 This effect was driven by the fact that both young and older adults had more false alarms for neutral words in both threat conditions as compared to the control condition. One possible explanation for this finding is that the overall emotional memory enhancement that is generally observed for both young and older adults (for review, see Kensinger, 2008) was relatively unaffected by stereotype threat. This finding is consistent with the fact that threat placement and valence did not affect the overall hits for young and older adults.

The fact that activating negative stereotypes about aging and memory impaired older, but not young, adults’ memory performance is consistent with previous research on the general phenomenon of stereotype threat. Specifically, individual performance is only impaired by stereotype threat if the domain being threatened is directly relevant to the population being tested (e.g., Aronson, Lustina, Good, and Keough, 1999). Thus, since age-related stereotypes about memory ability are not relevant to young adults, their memory performance is not affected when those stereotypes are activated (see also Hess et al., 2003).

It is important to note that an alternate possibility as to why stereotype threat impaired performance at retrieval, but not encoding, relates to encoding specificity effects (Tulving &Thompson, 1973). Retrieval is best when the affective and cognitive state at retrieval matches the state at encoding. When a threat is introduced prior to retrieval, this may lead to a “mismatch” in the participants’ state between encoding and retrieval, and this mismatch could lead to retrieval impairments. Although the contribution of this mismatch cannot be ruled out, it seems unlikely to be the sole contributor to our effects, for two reasons. First, this type of mismatch would be expected to impair retrieval of all items equally, whereas this was not the case in our results. Second, this mismatch should occur regardless of whether the threat preceded encoding but not retrieval, or preceded retrieval but not encoding; yet we found larger effects of threat in the latter condition.

Alternatively, introducing the threat prior to retrieval (but not encoding) may impair older adults’ memory because retrieval processes might be particularly sensitive to anxiety. Indeed, research in other domains of stereotype threat suggest that reminding individuals of domain-relevant negative stereotypes creates anxiety that subsequently impairs performance on that domain (Steele & Aronson, 1995; for review, see Schmader, Johns, and Forbes, 2008). Because retrieval processes measure what individuals remember, older adults may have heightened anxiety during retrieval as compared to encoding. This anxiety may be heightened when they are reminded of negative stereotypes related to their memory ability immediately prior to retrieval. Previous research has demonstrated that older adults who feel anxiety about their memory ability have impaired memory performance (e.g., Jonker, Smits, & Deeg, 1997). Anxiety could also have a disproportionate effect on memory for positive (and possibly) neutral items, while having a lessor effect on memory for the negative items, because the negative items would benefit from mood-congruency. Thus, it is possible that introducing the threat at retrieval created heightened anxiety for participants, thereby eradicating the valence bias they otherwise showed by impairing their memory for positive information while leaving their memory for negative information relatively unaffected. However, an important caveat to this explanation is that previous research examining whether anxiety mediates older adults’ memory decrements in the presence of stereotype threat has been unsuccessful (Hess, et al., 2003; Rahhal, Hasher, & Colbombe, 2001).

Although our findings demonstrated a more pronounced impairment for older adults’ memory when introducing a threat prior to retrieval, we are not suggesting that introducing a threat prior to encoding does not impair memory. Indeed, our linear contrasts demonstrated that older adults’ memory declined when comparing memory performance in the control condition to memory in the threat prior to encoding and then threat prior to retrieval conditions. This finding is consistent with previous research that has demonstrated that reminding older adults of negative age-related stereotypes prior to encoding impairs their subsequent memory performance (e.g., Chasteen et al., 2005; Hess et al., 2003; Hess et al., 2004; Hess & Hinson, 2006; Horton et al., 2008). One explanation for this is that previous research on the effects of stereotype threat on older adults’ memory has primarily measured overall recall, not recognition, performance (but see Hess, Emery, & Queen, 2009). Although the retrieval processes that support recollection are likely similar to those that support recall (see Yonelinas, 2002), optimal recall may require additional encoding processes to organize study material, thereby facilitating its later generation. It may therefore be the case that a threat placed at retrieval may disproportionately affect recognition, whereas a threat placed at encoding may be more likely to affect overall recall. Future research should investigate this possibility. Alternatively, it is possible that by introducing emotional information in our study, the threat effects at encoding were less pronounced since older adults’ showed a memory enhancement for positive as compared to negative information in the threat prior to encoding condition.

Practical Application

The present results emphasize that when older adults are exposed to stereotype threat, the disruption to memory is particularly pronounced if the threat precedes retrieval. One potential implication of these findings is that older adults’ ability to distinguish true from false memories could be negatively impacted if they are reminded of their memory decline, even implicitly, just before they reflect on past events. Because our memories are often building blocks for our decisions and our future prospections (e.g., Schacter, Addis, & Buckner, 2007), changes in the veracity of information remembered by older adults could have even broader consequences. These findings also have important implications for developing effective interventions to overcome the pernicious effects of stereotype threat on older adults’ memory. Specifically, they suggest that interventions should focus on how older adults extract information from memory, not on how they transfer new information into memory.

Negative stereotypes about aging and memory disrupt older adults’ memory

We examine the mechanism by which negative stereotypes disrupt emotional memory

We introduced subliminal negative stereotypes prior to encoding or retrieval

Negative stereotypes prior to retrieval had the greatest disruption on memory

Negative stereotypes therefore may disrupt monitoring processes at retrieval

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jeannette Kensinger, Dale Kensinger, Eunice Lee, Sarah Scott, Haley DiBiase, and Jake Savage for assistance with data collection. Support for this research was provided by a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Ruth Kirschstein National Research Service Award from the National Institute Aging to ACK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

In an earlier version of this manuscript, we reported data that were collected with 69 older adults (Mage = 75.0 years, SD = 5.6 years; 43 female) from the Boston area and 69 young adults (Mage = 19.4 years, SD = 1.2 years; 40 female) from both the Boston area as well as at Indiana University. However, many of our results were not significant at the traditional p < .05 level. Thus, at the suggestion of the reviewers, we collected more data with both young and older adults. We used power analyses to guide our data collection efforts that were based on achieving an estimated effect size similar to those acquired in related stereotype threat and aging research. An important limitation to collecting additional data in order to achieve a significant effect is that this has been widely shown to increase the likelihood of committing a Type I error. Thus, we referred to prior research where sequential stopping rules were used to adjust small sample sizes to achieve significant effects without committing a Type I error (Fitts, 2010). Specifically, in accordance with guidelines by Fitts (2010), we adjusted our significant threshold to p < .03.

A smaller concern about collecting new data was that the first author’s (ACK) location had changed from the time of the original data collection (from Boston to Indiana). We tested the additional older adults in Boston, where the original sample had been collected. For the young adult data, all the data reported here are from Indiana University. Although a small sample of young adults (N = 17) had been tested in Boston on the no-threat control condition, to match the original N for the older adults in the control condition, when we needed to increase the overall N of our older adult samples, we chose to re-collect the data for the young adult control condition at Indiana University, where the encoding and retrieval threat data had been collected. There was no significant difference in corrected recognition performance between the young adults in the two geographic groups (t(42) = 1.47, p = .15). Thus, the analyses reported here only consider the effects of age and condition, not geographic location.

Because additional data were collected in this condition to respond to reviewer concerns, only the original data in the control condition (N = 17) were collected by older adult experimenters. The remaining 7 older adult participants’ data were collected by two young adult experimenters.

Although not the focus of this paper, we also examined whether threat placement disrupted older adults’ memory bias for positive as compared to negative information by subtracting corrected recognition for negative information from corrected recognition for positive information. We entered this difference score into a univariate ANOVA with threat placement (control, threat at encoding, threat at retrieval) and age (young adults or older adults) as the between subject variables. Results revealed no main effect of age (F(1,153) = 1.39, p = .24, η2partial < .01) or threat placement (F < 1, η2partial < .01), but there was an age × threat placement interaction (F(2,153) = 3.41, p = .04, η2partial = .04). This suggests that although older adults’ memory enhancement for positive as compared to negative information was apparent in the control (MOlder adults = 0.17, SD = 0.18) and the threat prior to encoding (MOlder adults = 0.13, SD = 0.18) conditions, it was no longer apparent when the threat was introduced prior to retrieval (MOlder adults = 0.04, SD = 0.27). However, an important caveat to this interpretation is the fact that this interaction did not meet our modified threshold for significance.1 Although this finding may be further evidence that older adults do not show a memory advantage for positive information when controlled processes are disrupted (Mather & Knight, 2005; Reed & Carstensen, 2012), it should be taken with caution given the marginal effects. Future research should examine this question.

References

- Aronson J, Lustina MJ, Good C, Keough K. When white men can’t do math: Necessary and sufficient factors in stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1999;35(1):29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Barber SJ, Mather M. Stereotype threat in older adults: When and why does it occur, and who is most affected? In: Verhaeghen P, Hertzog C, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Emotion, Social Cognition, and Everyday Problem Solving During Adulthood. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barber SJ, Mather M. Stereotype Threat Can Both Enhance and Impair Older Adults’ Memory. Psychological science. 2013;24(12):2522–2529. doi: 10.1177/0956797613497023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Technical report C-1. Gainesville, FL: The Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida; 1999. Affective norms for English words (ANEW): Stimuli, instruction manual and affective ratings. [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, Rao SM, Wagner AD, Mayer AR, Schacter DL. Can medial temporal lobe regions distinguish true from false? An event-related functional MRI study of veridical and illusory recognition memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98(8):4805–4810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081082698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasteen AL, Bhattacharyya S, Horhota M, Tam R, Hasher L. How feelings of stereotype threat influence older adults’ memory performance. Experimental Aging Research. 2005;31(3):235–260. doi: 10.1080/03610730590948177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran T, Schacter DL, Norman KA, Galluccio L. False recognition after a right frontal lobe infarction: Memory for general and specific information. Neuropsychologia. 1997;35(7):1035–1049. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitts DA. Improved stopping rules for the design of efficient small-sample experiments in biomedical and biobehavioral research. Behavior research methods. 2010;42(1):3–22. doi: 10.3758/BRM.42.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM, Auman C, Colcombe SJ, Rahhal TA. The impact of stereotype threat on age differences in memory performance. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2003;58(1):3–11. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.1.p3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM, Hinson JT, Statham JA. Explicit and implicit stereotype activation effects on memory: Do age and awareness moderate the impact of priming? Psychology and Aging. 2004;19(3):495–505. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM, Hinson JT. Age-related variation in the influences of aging stereotypes on memory in adulthood. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:621–625. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.3.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM, Emery L, Queen TL. Task demands moderate stereotype threat effects on memory performance. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences. 2009;64(4):482–486. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton S, Baker J, Pearce GW, Deakin JM. On the malleability of performance: Implications for seniors. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2008;27:446–465. [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht M, Ben-Zeev T. A threatening intellectual environment: Why females are susceptible to experiencing problem-solving deficits in the presence of males. Psychological Science. 2000;11(5):365–371. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonker C, Smits CHM, Deeg DJH. Affect-related metamemory and memory performance in a population0based sample of older adults. Educational Gerontology. 1997;23(2):115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kang SK, Chasteen AL. The moderating role of age-group identification and perceived threat on stereotype threat among older adults. The International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 2009;69(3):201–220. doi: 10.2190/AG.69.3.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kausler DH. Learning and memory in normal aging. Academic Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley CM, Sahakyan L. Memory, monitoring, and control in the attainment of memory accuracy. Journal of Memory and Language. 2003;48(4):704–721. [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Corkin S. Memory enhancement for emotional words: Are emotional words more vividly remembered than neutral words? Memory and Cognition. 2003;31:1169–1180. doi: 10.3758/bf03195800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA. How emotion affects older adults' memories for event details. Memory. 2008;17:1–12. doi: 10.1080/09658210802221425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light LL. Memory and aging: Four hypotheses in search of data. Annual review of psychology. 1991;42(1):333–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.42.020191.002001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and motivated cognition: The positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends Cognitive Science. 2005;9(10):496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Knight M. Goal-Directed Memory: The Role of Cognitive Control in Older Adult's Emotional Memory. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20(4):554–570. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisner BA. A meta-analysis of positive and negative age stereotype priming effects on behavior among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2012;67(1):13–17. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg L, Cabeza R, Tulving E. PET studies of encoding and retrieval: The HERA model. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1996;3(2):135–148. doi: 10.3758/BF03212412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahhal TA, Hasher L, Colcombe SJ. Instructional manipulations and age differences in memory: Now you see them, now you don’t. Psychology and Aging. 2001;16:697–706. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.4.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed AE, Carstensen LL. The theory behind the age-related positivity effect. Frontiers in psychology. 2012;3 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roediger HL, McDermott KB. Creating false memories: Remembering words not presented in lists. Journal of experimental psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1995;21(4):803. [Google Scholar]

- Schmader T, Johns M, Forbes C. An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychological Review. 2008;115(2):336–356. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, Addis DR, Buckner RL. The Prospective Brain: Remembering the past to imagine the future. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8:657–661. doi: 10.1038/nrn2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, Buckner RL, Koutstaal W, Dale AM, Rosen BR. Late onset of anterior prefrontal activity during true and false recognition: an event-related fMRI study. Neuroimage. 1997;6(4):259–269. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekaquaptewa D, Thompson M. Solo status, stereotype threat, and performance expectancies: Their effects on women’s performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2003;39(1):68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Spaniol J, Voss A, Grady CL. Aging and emotional memory: Cognitive mechanisms underlying the positivity effect. Psychology & Aging. 23(4):859–872. doi: 10.1037/a0014218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SJ, Steele CM, Quinn DM. Stereotype threat and women's math performance. Journal of experimental social psychology. 1999;35(1):4–28. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1995;69(5):797. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AK, Dubois SJ. Reducing the burden of stereotype threat eliminates age differences in memory distortion. Psychological Sciences. 2011;22(12):1515–1517. doi: 10.1177/0956797611425932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E, Thomson D. Encoding specificity and retrieval processes in episodic memory. Psychological Review. 1973;80(5):352–373. [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E, Kapur S, Craik FI, Moscovitch M, Houle S. Hemispheric encoding/retrieval asymmetry in episodic memory: Positron emission tomography findings. PNAS. 1994;91:2016–2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werheid K, Gruno M, Kathmann N, Fischer H, Almkvist O, Winblad B. Biased recognition of positive faces in aging and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25(1):1–15. doi: 10.1037/a0018358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonelinas AP. The nature of recollection and familiarity: A review of 30 years of research. Journal of Memory and Language. 2002;46:441–517. [Google Scholar]