Abstract

Objective

A hallmark of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the chronic pain that accompanies the inflammation and joint deformation. Patients with RA rate pain relief with highest priority, however, few studies have addressed the efficacy and safety of therapies directed specifically towards pain pathways. The conotoxin MVIIA (Prialt/Ziconotide) is used in humans to alleviate persistent pain syndromes because it specifically blocks the CaV2.2 voltage-gated calcium channel, which mediates the release of neurotransmitters and proinflammatory mediators from peripheral nociceptor nerve terminals. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether block of CaV2.2 can suppress arthritic pain, and to examine the progression of induced arthritis during persistent CaV2.2 blockade.

Methods

Transgenic mice (Tg-MVIIA) expressing a membrane-tethered form of the ω-conotoxin MVIIA, under the control of a nociceptor-specific gene, were employed. These mice were subjected to unilateral induction of joint inflammation using the Antigen- and Collagen-Induced Arthritis (ACIA) model.

Results

We observed that CaV2.2-blockade mediated by t-MVIIA effectively suppressed arthritis-induced pain; however, in contrast to their wild-type littermates, which ultimately regained use of their injured joint as inflammation subsides, Tg-MVIIA mice showed continued inflammation with an up-regulation of the osteoclast activator RANKL and concomitant joint and bone destruction.

Conclusion

Altogether, our results indicate that alleviation of peripheral pain by blockade of CaV2.2- mediated calcium influx and signaling in nociceptor sensory neurons, impairs recovery from induced arthritis and point to the potentially devastating effects of using CaV2.2 channel blockers as analgesics during inflammation.

Keywords: CaV2.2 channels, chronic inflammation, nociceptor

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disorder that affects 1–2% of the worldwide population with a prevalence that increases with age, especially in women. It is characterized by a persistent erosive synovitis that can lead to severe damage, disability and loss of function of the affected joints, and to chronic pain (1). Current treatments aim at reducing inflammation to slow down the irreversible joint damage and to relieve inflammatory pain. Recently it has been hypothesized that sensitization of the nociceptive system may contribute to the intensity and chronicity of the pain accompanying rheumatic diseases (2–4).

The transmission of pain relies on voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, in particular on CaV2.2, which is critically involved in nociceptor sensory transmitter release (5) and is considered a target to control osteoarthritis pain (6). CaV2.2 can be specifically blocked by the ω-conotoxin MVIIA. The synthetic form of the MVIIA conotoxin, commercialized as ziconotide or Prialt®, was approved in 2004 for the treatment of severe chronic pain associated with cancer, AIDS, inflammatory pain and neuropathies and cases of intractable morphine-insensitive pain. Importantly, ziconotide acts synergistically with opioid analgesics without inducing tolerance or addiction (7). However, its use requires intrathecal microinfusion pumps to minimize side effects on central nervous system channels, which can cause psychosis over a certain threshold. Recent efforts to chemically re-engineer conotoxins have lead to more stable cyclic forms that can be administered orally rather than intrathecally (8). If given orally, conotoxins may prove useful in managing pain in chronic inflammatory disorders like arthritis. However, the effect of CaV2.2-blockade on ongoing tissue inflammation in chronic inflammation or autoimmunity has so far not been addressed.

In the present study we investigated the contribution of CaV2.2 to the development of arthritis and the possible side-effects of targeting CaV2.2 in inflammatory pain management. To this end we employed pain-insensitive transgenic mice (Tg-MVIIA) that express ω-conotoxin MVIIA under control of the regulatory regions of the nociceptor-specific Scn10a gene and thus selectively block CaV2.2 channels in nociceptors (9). In the context of our study it was essential to use a preclinical arthritis model that recapitulates the erosive inflammatory joint disease progression, and its autoimmune character, including the development of anti–citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA) that occur in RA patients (10). ACPA are particularly interesting as they might be directly involved in the differentiation of osteoclast precursors into mature bone resorbing cells (11). Therefore, we chose the Antigen- and Collagen-induced arthritis (ACIA) model that unlike commonly used mouse models, effectively mimics the long lasting aspect of erosive synovitis along with autoimmune signs like the presence ACPA (12).

The synovial joint inflammation is to a large extent driven by TNFα (13), which also regulates the expression of RANKL (Receptor Activator of Nuclear factor Kappa-B Ligand; also known as OPGL, ODF and TRANCE), the main mediator of osteoclastogenesis and inflammatory bone resorption (14). In RA, RANKL is expressed by synovial fibroblasts and activated synovial T cells. It triggers osteoclastogenesis and bone loss (15, 16), and promotes arthritis-induced joint destruction in the inflamed synovium (17). Therefore we investigated RANKL expression in the inflamed joints of arthritic wt mice and pain-insensitive Tg-MVIIA mice.

We showed that CaV2.2 blockade effectively suppresses arthritis-induced pain but prolongs the ongoing inflammation leading to drastic joint deformation via the up-regulation of the osteoclast activator RANKL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

For the generation of Tg-MVIIA mice, a BAC clone (RP23-214H2) encompassing the Scn10a gene was modified to include the t-MVIIA expression cassette (9). Mice were backcrossed to the C57BL/6 strain (from Charles River) for 10 generations. All procedures are registered and approved by the appropriate German federal authorities and by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Rockefeller University (protocol 11444).

Antigen- and Collagen-induced Arthritis (ACIA) model

Mice were immunized s.c. with 100 µg mBSA (Sigma-Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany) in PBS emulsified with complete Freund's adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich). One week later mice were immunized s.c. with 50 µg mBSA and 100 µg bovine collagen type II (mdbioproducts, Zurich, Switzerland) emulsified with Freund’s incomplete adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich). In parallel to each immunization step, 200 ng of Bordetella pertussis toxin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) were given i.p. Two weeks later arthritis was induced under inhalational isofluorane anaesthesia (Abbvie, Ludwigshafen, Germany) by intra-articular injection of 50 µg mBSA dissolved in 20 µl of PBS into the left knee joint cavity. Animals were analysed at sequential time points after arthritis induction reflecting different disease stages: acute arthritis (days 1–6), transition phase (day 10), early chronic (3–4 weeks) and late chronic arthritis (6–10 weeks).

Histological analysis and scoring

Knee joints were fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde, decalcified with EDTA for 7–10 days, and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (3–5 µm) were stained with HE for microscopic evaluation. Scoring of the knee sections was performed in a blinded manner with examination of four sections per joint. A multi-parameter scoring system was used (see Table 1) and individual scores were sumed up.

Table 1.

Histological scoring of knee joint sections

| Parameter | Score 1 | Score 2 | Score 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Acute inflammation |

granulocyte exudate | scattered single cells |

patches of granulocytes |

massive exudate |

| infiltration of synovial membrane with granulocytes |

single granulocytes |

small infiltrate |

dense infiltrates |

|

| fibrin exudate | exudate present | - | - | |

|

Chronic inflammation |

synovial hyperplasia | light hyperplasia | moderate hyperplasia |

massive hyperplasia |

| infiltration of synovial membrane by mononuclear cells |

light | moderate | dense infiltrates |

|

| periarticular structures | light fibrosis and small cellular infiltrates |

moderate fibrosis and infiltrates |

massive fibrosis and dense infiltrates |

|

| Destruction | destruction and deformation of articular surface |

minimal | > 10% | > 50% |

| pannus | small pannus | several patches |

excessive | |

Immunohistochemical analysis

Paraffin sections were deparaffinised, pretreated with 5% donkey serum, followed by an anti-RANKL antibody (polyclonal goat anti-mouse IgG, R&D Systems, Minneapolis), and a biotinylated donkey anti-goat antibody and streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (SA-HRP) (both JacksonImmunoResearch, Newmarket, UK). As isotype control we used goat serum as primary antibody. Enzyme reactions were developed with the AEC + Substrate Kit (DAKO, Hamburg, Germany). RANKL expression was quantified using ImageJ (1.48v) software, by measuring the % of the area of the cartilage stained positive for RANKL.

Spinal cord sections of the lumbar region innervating the knee joint (comprising nerve roots L4 and L5) were embedded in TissueTek O.C.T. (Sakura Finetek, Zoeterwoude, The Netherlands), snap frozen and cut using a microtome, dried and dehydrated with ice-cold acetone. For immunohistochemistry, cryosections were rehydrated in Tris buffer and stained with a rabbit anti-substance P antibody (Zymed/Invitrogen, CA), followed by a biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit antibody (JacksonImmunoResearch) and SA-HRP. As isotype control we used rabbit serum. Enzyme reactions were developed as described above.

Detection of antigen-specific immunoglobulins

Anti-MVIIA antibodies were measured by flow cytometry. HEK293 cells transfected with a GFP-MVIIA construct were incubated with serum from wt or Tg-MVIIA mice. MVIIA-specific antibodies were detected by a PE-labelled anti-mouse IgG detection antibody and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was compared. mBSA-specific IgG titres in serum were determined by capture ELISA. Immunosorp microtiter plates (Nunc, Langenselbold, Germany) were coated with mBSA (Sigma-Aldrich). IgG and IgM capture and detection antibodies and standards were purchased from Southern Biotech (Eeling, Germany). For detection of ACPA Anti-MCV (Mutated Citrullinated Vimentin) plates were obtained from Orgentec Diagnostica (Mainz, Germany) and measurements were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Calf thymus DNA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Bound antibodies were detected using peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse antibodies (Southern Biotech) and TMB (tetramethylbenzidine) substrate solution (BD-Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) and analysed at 450 nm.

Cytokine secretion assay

The draining lymph nodes (popliteal and inguinal) were isolated at different disease stages and single cell suspensions were stimulated in vitro for 4h with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)/ Ionomycin and Brefeldin A in RPMI supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were stained for surface expression of CD4 (Biolegend) and intracellular expression of TNFα (Biolegend) and IL-17 (ebiosciences) using the Fix & Perm kit (Invitrogen, California, USA). Flow cytometry analyses were performed on a FACSCantoII (BD Biosciences).

Motor activity, incapacitance test and intra-articular injections

Motor activity was measured as distance covered in open field activity boxes (TSE Systems) for 30 min. Pain was assessed in a blinded manner using an Incapacitance Meter (Harvard Apparatus, MA). Mice were placed in a specific holder with their hind paws positioned on two sensor plates that measure the weight (in g) applied to each paw. The weight born on the inflamed arthritic hind leg was substracted from the weight born on the non-inflamed leg. Weight-bearing measurements were collected at day 0, 3, 10 and 21 days after arthritis induction.

Intra-articular injections were performed every other day starting one day after arthritis induction with 1µM soluble MVIIA (Sigma-Aldrich) into the inflamed knee joint and PBS in the contralateral joint in a volume of 20µl. Incapacitance was measured 3 and 10 days after arthritis induction.

Heart rate measurements

Heart rate measurements were performed in non-anaesthezied mice with the ecgTUNNEL system (emka Technologies, Paris, France).

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Tissues were dissected, collected in Trizol and homogenized. Knee tissue was obtained from the hind limbs of neonatal mice by removing most the diaphysis part of the thighs and shanks. The entire knee joint region including skin, bone and cartilage was snapped frozen and ground in a tissue grinder for RNA extraction. RNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform (treated with DNase I (Invitrogen)) or the RNeasy Plus Microkit (Quiagen). RT-PCR was performed with the RNA SuperScript® III One-Step RT-PCR System (Invitrogen) as described before (9).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed with the non-parametric Mann–Whitney-U-test (Fig. 2B,C), the parametric t-test (Fig. 4A, 5D), the multiple t-test corrected for multiple comparisons (Fig. 5A,B) and the parametric two–way ANOVA test (Fig. 3, 4) with the Sidak’s multiple comparison posthoc test. Results are expressed as dot plots with the arithmetic mean and errors bars illustrating the 95% confidence interval (CI) (Fig. 2), and line (Fig. 3) or bar graphs showing the mean and SEM (Fig. 4,5). Differences with a probability of p<0.05 are indicated with *, p<0.01 with **, p<0.001 with *** and **** p<0.0001. The number of animals per study is indicated in each figure legend. The 95% CI the interaction p values for ANOVA and t-tests are indicated in the results.

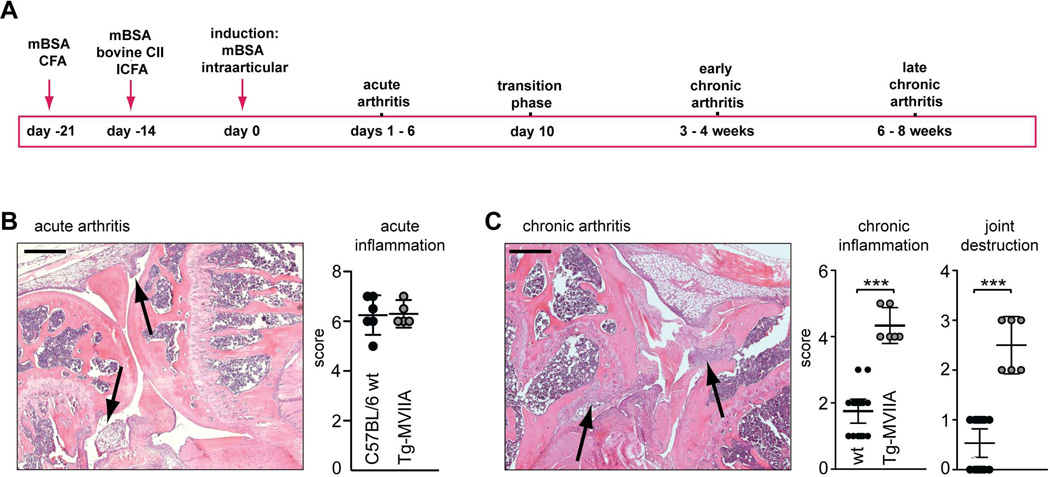

Figure 2.

Aggravated development of induced arthritis in Tg-MVIIA mice. (A) Experimental timeline for the Antigen- and Collagen-induced arthritis (ACIA) model. mBSA: methylated bovine serum albumin, CFA: Complete Freunds’ Adjuvant, CII: bovine Collagen type II. (B,C) Histological assessment of knee joints by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining in the acute (B) and chronic (C) phase of inflammation Arrows indicate cellular infiltrates and fibrinous exudates (in B), and cellular aggregates and synovial hyperplasia (in C). A multi-parameter grading system was used (see Table I), where observation of the indicated individual signs of acute inflammation, chronic inflammation and joint destruction was assigned the indicated score (ranging from 1–3 for each parameter) and scores were summed up. The corresponding scores for wt and Tg-MVIIa mice are indicated in the graph. Statistics: Mann-Whitney-Test, *** p < 0,001, n = 6–16 mice per group. Scale bars: 400 µm.

Figure 4.

Analyses of autoimmune reactivity in Tg-MVIIA mice. (A) Heart rates (bmp: beats per minute) of wt and Tg-MVIIA mice were comparable, n = 5–6. (B) Healthy wt or Tg-MVIIA mice have similar number of CD4+ T cells in the peripheral blood (naive: CD62Lhigh CD44low, effector: CD62Llow CD44high, memory: CD62Lhigh CD44high); n = 4–6. (C, left) Test for autoantibody formation against t-MVIIA toxin in Tg-MVIIA mice. t-MVIIA transfected HEK-293 cells were incubated with serum from wt or Tg-MVIIA mice followed by a PE-labeled anti-mouse IgG detection antibody. Comparison of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for wt and Tg-MVIIA sera did not reveal the presence of MVIIA-specific autoantibodies in Tg-MVIIa mice; n = 4. (C, right) Test for anti double-stranded (ds) DNA antibodies as indicators of autoimmunity. Sera from wt and Tg-MVIIA mice were tested for IgM or IgG antibodies recognizing calf-thymus DNA. The levels of anti dsDNA antibodies were similar in wt and Tg-MVIIA and significantly lower than in the autoimmune-prone RORγt-deficient mice (positive control). n = 6. (D) Development of antibodies against mutated citrullinated vimentin (MCV/ACPA) and the arthritis-inducing antigen mBSA in wt and Tg-MVIIA mice. Sera of wt and Tg-MVIIA mice were analysed at consecutive indicated days after arthritis induction; n = 6–10.

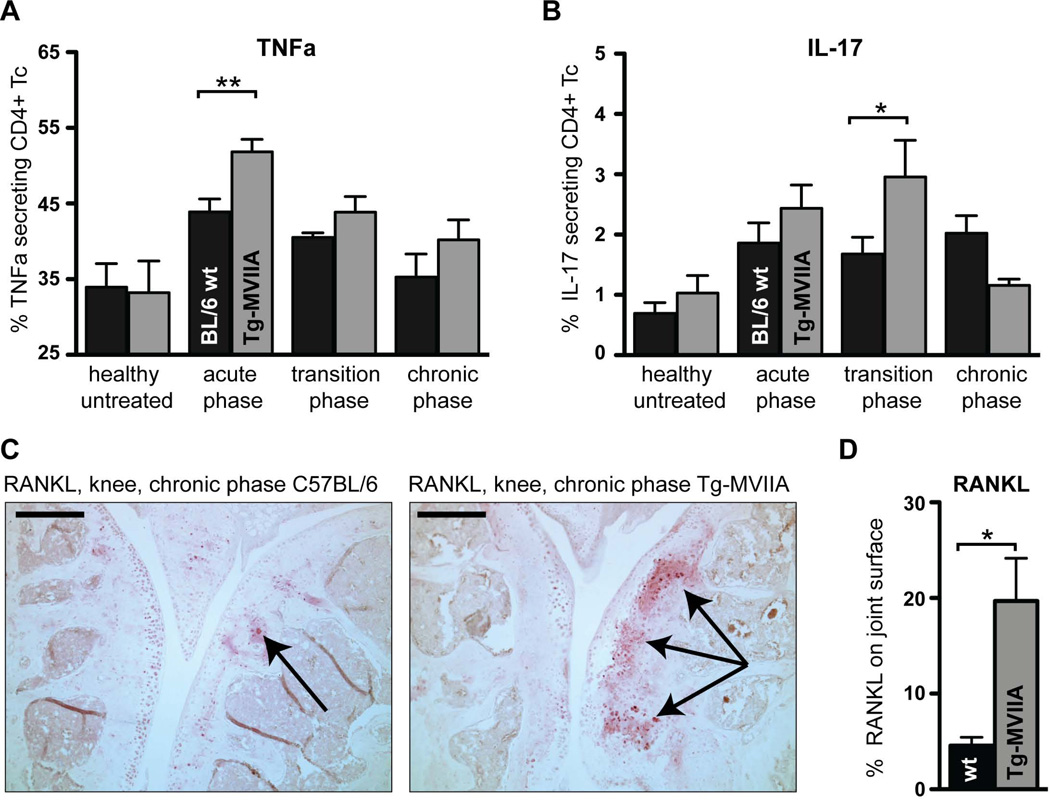

Figure 5.

Tg-MVIIA mice express elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines and of the osteoclast activator RANKL after induced arthritis. (A,B) Cytokine production by CD4+ T cells from lymph nodes draining the knee joint. Single cell suspensions from lymph nodes of wt and Tg-MVIIA mice at different stages of the disease were stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin and subsequently stained for expression of CD4, TNFα, and IL-17. (A) During the acute inflammation phase CD4+ T cells from Tg-MVIIA mice produced significantly more TNFα upon stimulation than CD4+ T cells from wt mice, (B) IL-17 levels were significantly increased in Tg-MVIIA compared to wt mice during the transition phase; n= 5–10 mice per group. (C,D) Enhanced expression of RANKL in arthritic joints of Tg-MVIIA mice. In the chronic phase of the disease, RANKL expression (in red, indicated by black arrows) is far more pronounced in the knee joints of Tg-MVIIA mice than in joints of arthritic wt mice. Scale bars: 500 µm. (D) Quantification of RANKL immunoreactivity. Data is representative for 3 experiments.

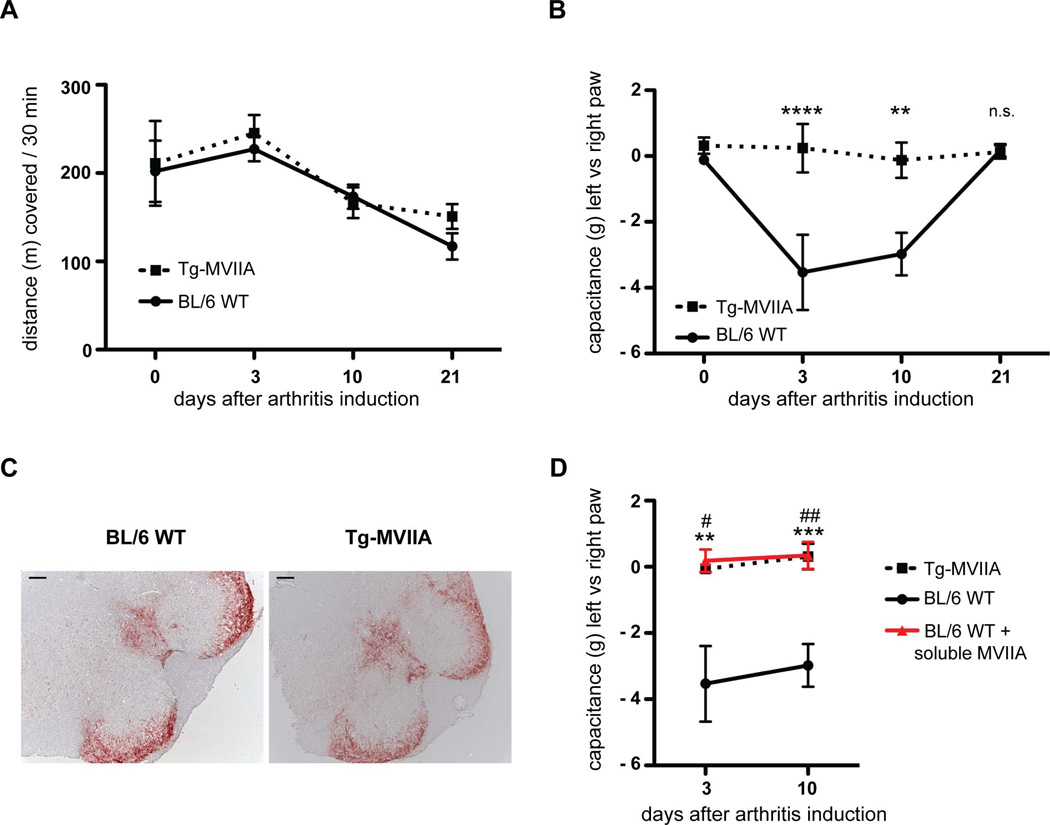

Figure 3.

Pain behaviour after arthritis induction. (A) Motor activity measured in open field activity boxes indicate no differences after arthritis induction, n = 5–9 mice per group. (B) Pain assessed with an Incapacitance Meter for weight-bearing measurements. Squares (wt) or circles (Tg-MVIIA) indicate the weight difference (in g) applied with the inflamed hindlimb minus the non-treated hindlimb. During the acute and transition phases (days 3 and 10) wt mice (black line) bore significantly less weight on their inflamed hindlimb. Tg-MVIIA mice (dashed line) bore the same weight. ** p < 0,01; n = 5–9. (C) Similar Substance P immunoreactivity (red) during acute arthritis in wt and Tg-MVIIA spinal cord regions that innervate the knee joint. Bar 100 µm. (D) Intra-articular injection of soluble MVIIA abrogates pain sensing.in wt mice (red line) similarly to Tg-MVIIA mice (dashed line). Soluble MVIIA was injected into the inflamed knee joint and PBS in the contralateral joint every other day starting day 1 after arthritis induction and incapacitance was measured at day 3 and 10. Statistical differences are indicated by * between wt and Tg-MVIIA, and by # between wt and wt injected with MVIIA. n = 5–12, bars show the mean and SEM.

RESULTS

Expression of conotoxin MVIIA in nociceptors blocks Cav2.2-mediated pain neurotransmission

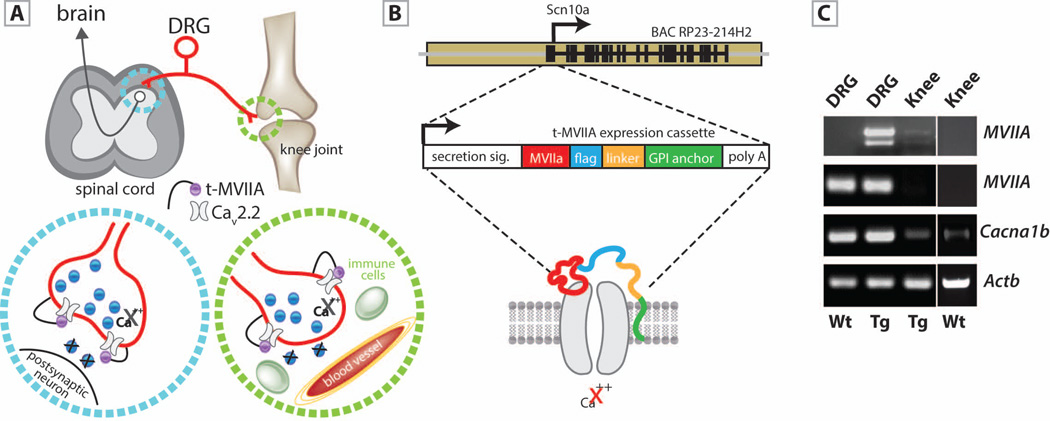

To examine the contribution of CaV2.2 channels to the development of induced inflammatory arthritis we employed the genetic mouse model Tg(Scn10a-MVIIA-G109)Iit, hereafter abbreviated as Tg-MVIIA. This mouse expresses an isoform of the MVIIA conotoxin that is tethered to the cell-membrane and blocks the CaV2.2 channel (Fig. 1A,B) specifically in nociceptive neurons (9). Accurate expression of MVIIA in Tg-MVIIA mice was confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 1C). Dorsal Root Ganglia (DRG), which contain the somata of nociceptive neurons, express MVIIA, Scn10a (BAC driver) and Cacna1b (alpha1B subunit of CaV2.2). MVIIA is also expressed in the knee of Tg-MVIIA mice at small but detectable amounts. Given that CaV2.2 is expressed not only in presynaptic terminals in the spinal cord, but also in the peripheral endings of nociceptors innervating the knee joint ((18) and Fig. 1C), we sought to test whether blocking of CaV2.2 channels in a cell-autonomous manner in nociceptors had an impact on knee joint inflammation in an autoimmune model of arthritis.

Figure 1.

Mouse model for transgenic expression of the conotoxin MVIIA in nociceptors. (A) Scheme illustrating the sites of expression of the tethered conotoxin along the pain circuit. A nociceptor (red) with its soma in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) projects bidirectionally to the spinal cord (blue circle) and to nerve endings in the knee joint (green circle). Tethered t-MVIIA (in purple) binds to CaV2.2 and blocks Ca2+ influx. (B) The BAC of the nociceptor specific Scn10a gene contains the tethered toxin expression cassette : MVIIA neurotoxin (red), flag epitope (light blue), linker (orange) and GPI anchor (green) that targets the molecule to the cell membrane, and restricts its action to receptors that are coexpressed on the cell surface. (C) RT-PCR analyses show MVIIA expression in DRG neurons and at lower levels in the knee of Tg-MVIIA mice and no expression in wt mice. Scn10a (used as BAC driver) is only detected in DRG cell bodies but not in the mouse knee. Cacna1b (encoding the α1B subunit of CaV2.2) was highly expressed in DRG neurons, and at lower levels in knee joint preparations of wt and Tg-MVIIA mice at comparable levels. Actb: actin b used as control.

Joint inflammation in Antigen-Collagen-induced Arthritis (ACIA

Knee joint inflammation was induced using our recently described model of combined Antigen-and Collagen-Induced Arthritis (ACIA) (Fig. 2A). We evaluated the severity of inflammation and joint destruction by semiquantitative scoring of hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stained paraffin sections of the induced knee joint. As shown in Figure 2 and Table 1, this protocol induces a strong initial inflammation (acute arthritis) characterized by fibrin exudates and a severe neutrophil influx into the synovial cavity within the first days after arthritis induction (Fig. 2B). Subsequently, in the transition phase fibrin exudation ceases and mononuclear cells infiltrate the synovial cavity leading to synovial hyperplasia. Three weeks after arthritis induction, (early chronic phase), dense clusters of lymphocyte infiltrates are detected in the synovial and parasynovial tissue, as well as fibrosis and abrasion of cartilage and bone (Fig. 2C). Histological analysis revealed no differences between wt and Tg-MVIIA mice during the acute phase (Fig. 2B). However, in the chronic phase Tg-MVIIA mice showed significantly higher scores for chronic inflammation (Fig. 2C, wt: CI 1.38–2.11; Tg-MVIIA: CI 3.79–4.87), and joint erosion with massive bone deformation (wt: CI 0.24–0.82; Tg-MVIIA: CI 1.9–3.07).

Transgenic mice expressing MVIIA show no deficits in joint capacitance after arthritis induction

Since arthritis in humans often affects weight-bearing joints, we wanted to assess whether our ACIA joint inflammation model would evoke behavioural changes associated with pain, such as reduction in motor activity and differences in weight-bearing of the inflamed versus the non-inflamed hind limb.

The motor activity of wt and Tg-MVIIA mice was tested in open field activity boxes at different days after arthritis induction by comparing the distance covered within 30 min. Both mouse groups travelled equal distances (Fig. 3A, F(3,61)=0.3415, p=0.79), indicating that inflammatory pain induced by the ACIA model does not impair horizontal motor activity

We performed a weight-bearing incapacitance test to assess whether the mice perceive pain from the induced inflammation on the left hind leg vs. the right, control leg. Mice were placed into a holder where the hind paws rest on two separate weight sensor plates. The postural equilibrium reflects a weight-bearing asymmetry, i.e. the level of discomfort in the arthritic knee joint. Before immunization (day 0) we observed no weight-bearing asymmetry in wt and Tg-MVIIA mice as expected (Fig. 3B). During the acute (day 3) and transition (day 10) phases, wt mice bear significantly less weight on their inflamed leg (Fig. 3B, F(3,74)=6.028, p=0.001), while Tg-MVIIA show no weight-bearing asymmetry. This indicates that wt mice perveive pain that is maintained for the first 10 days after arthritis induction. During the chronic arthritis phase (at day 21), we observed no weight-bearing differences in wt mice indicating that pain or discomfort diminishes with time. This is in agreement with the histological findings in wt mice at this later stage (Fig. 2C), that shows that the joint inflammation resolves during the chronic phase. Remarkably, Tg-MVIIA mice showed no signs of weight-bearing asymmetry at any of the examined time points (Fig. 3B); they always bore the same weight on both, induced and non-induced, hind limbs despite ongoing knee inflammation and joint deformation (Fig. 2C).

Several possible mechanisms that may account for this enhanced induced arthritis upon CaV2.2-blockade could be proposed. Since CaV2.2 calcium influx triggers release of neurotransmitters and pro-inflammatory neuropeptides (i.e. substance P and calcitonin-gene related peptide (CGRP)), we analysed spinal cord sections at the level of the lumbar region innervating the knee for Substance P immunoreactivity. This analysis did not reveal apparent differences in the location or amount of substance P between both mouse groups (Fig. 3C). This finding indicates that CaV2.2 neurotransmission at the spinal level might not be the only component in pain transmission. Since MVIIA is also expressed in the knee (Fig.1C), we postulated that the analgesic effect of CaV2.2 blockade might take place locally in the joint. To test this hypothesis we injected soluble MVIIA in the inflamed knee of wt mice after induced arthritis. Interestingly mice no longer showed signs of pain, measured as weight-bearing deficits, both during the acute and transition phase (Fig. 3D, F(2,45)=21.93, p,0.0001). This finding indicates that local activity of CaV2.2 at peripheral nerve endings is critical for pain perception.

Normal immune phenotype in Tg-MVIIA transgenic mice

Tg-MVIIA mice develop a strikingly severe arthritis in the ACIA model in comparison to wt mice. Hence, we checked for a priori malprogramming in the immunological compartment of healthy untreated Tg-MVIIA mice. None of the lymphoid organs of Tg-MVIIA mice showed morphological abnormalities in size, structure or cellular aggregates and no differences were observed in their heart rate (Fig. 4A). The cellular compartment of the adaptive immune system, i.e. B and T cells, did not differ in total numbers or activation state between wt and Tg-MVIIA mice (Fig. 4B, F(3,40)=0.029, p=0.993). Since the presence of the MVIIA conotoxin at the cell-surface of nociceptors could have elicited an anti-MVIIA autoimmune response in these mice, we analysed serum from untreated Tg-MVIIA or wt mice for the presence of anti-MVIIA antibodies. However, MVIIA-specific antibodies were not detectable in the sera of Tg-MVIIA mice (Fig. 4C, autoantibodies: F(1,12)=0.025, p=0.87). In addition, Tg-MVIIA mice are not per se prone to autoimmunity. Basal levels of IgG as well as IgM autoantibodies directed to double-stranded DNA, which contribute to inflammation and tissue damage, do not differ between Tg-MVIIA and wt mice, and are significantly lower than those of autoimmune-prone mice such as RORγt–deficient mice (19)(Fig. 4C IgM: F(2,16)=9.14, p=0.0022; IgG: F(2,16)=52.54, p<0.0001).

Surprisingly, in contrast to the impressive difference in arthritis severity and joint deformation, the induction of ACPA (Anti-Citrullinated Peptide/Protein Antibodies), which are highly specific for RA, did not differ at any of the examined time points between wt or Tg-MVIIA mice (Fig. 4D, ACPA: F(4,64)=0.597, p=0.666), neither did the antibody response to the arthritis-inducing antigen mBSA (Fig. 4D; mBSA: F(4,63)=0.4054, p=0.8041).

These results indicate that Tg-MVIIA mice have no gross defects in immunologic tolerance and that the observed differences in disease chronicity and joint destruction between wt and Tg-MVIIA mice are indeed directly related to MVIIA blockade of CaV2.2 channels and reduced pain neurotransmission in these animals.

Elevated TNFα and RANKL enhance inflammatory arthritis in pain-insensitive mice

We wanted to evaluate whether inhibition of nociceptive neurotransmission interferes with the expression of inflammatory mediators that are involved in inflammation and bone destruction in order to shed some light on the underlying mechanisms that entail the severe destructive phenotype in Tg-MVIIA mice.

Since TNFα is known to regulate the expression of RANKL, the main mediator of osteoclastogenesis and inflammatory bone resorption, we tested the ability of lymphocytes from arthritic mice to produce TNFα upon restimulation. Cells from wt and Tg-MVIIA mice were isolated from the draining lymph nodes in different disease stages and stimulated in vitro with PMA and Ionomycin. Healthy untreated mice showed no difference in the ability of their CD4+ T cells to produce TNFα. However, during the acute phase, CD4+ T cells from Tg-MVIIA mice produced significantly more TNFα upon stimulation than cells from wt mice (Fig. 5A, p=0.006). Similarly, the levels of secreted IL-17 by T cells from Tg-MVIIA mice were significantly increased compared to wt in the transition phase (Fig. 5B, p=0.048). This suggests that increased proinflammatory cytokine production during the acute and transition phases of arthritis may contribute to the enhanced joint deformation in Tg-MVIIa mice.

Given the evidence on the involvement of RANKL in arthritic bone damage, we sought to compare RANKL expression in the chronic stage of our ACIA model. Indeed, immunostaining for RANKL was more prominent in the knee joints of Tg-MVIIA mice compared to wt mice (Fig. 5C,D, p=0.026). Our study for the first time indicates that analgesic treatment by CaV2.2 blockade enhances RANKL expression and joint destruction.

DISCUSSION

The studies presented here establish that the CaV2.2 antagonist, conotoxin MVIIA (ziconotide/prialt), effectively blocks inflammatory pain in a mouse model of induced arthritis, but also reveal that this blockade severely enhances the ongoing joint inflammation and deformation. We show for the first time the deleterious impact of this type of analgesics on ongoing inflammation, suggesting that the activity of CaV2.2 channels in nociceptor neurons that innervate the injured joint is ultimately beneficial to re-establish the levels of proinflammatory cytokines and of the osteoclast-activator RANKL.

In arthritis, as in other inflammatory disorders, pain intensity does not necessarily reflect disease activity, since pain often persists in patients with adequately controlled inflammation. Indeed, inflammation in the joint causes peripheral and central sensitization, which is thought to be the basis of arthritic pain that appears as spontaneous pain and hyperalgesia (20). Our finding adds to the growing evidence that the peripheral nervous and immune systems, traditionally thought to subserve separate functions, form an integrated protective mechanism. Nociceptors are not only highly sensitive to immune mediators, but can also release potent immune-acting mediators, actively modulating and coordinating immune responses (21) in pathological inflammations like colitis, psoriasis, asthma, and arthritis (22–25). It has therefore been suggested to target nociceptors for the treatment of immune disorders (21). However, recent studies on interactions between immune cells and nociceptive neurons reveal contrarious effects. In certain immunopathologies denervation improves inflammation such as blockade of substance P in colitis and psoriasis, which dampens the damage mediated by T cells and other leukocytes (23, 25). In contrast, mice lacking an acid-sensing channel present in nociceptors show signs of elevated inflammation during induced arthritis (26). In line with this study, our results point to devastating consequences of administering CaV2.2 inhibitors to patients suffering from arthritis even if these inhibitors provide pain relief. Our findings are reminiscent of the risks and benefits observed with antibodies against neurotrophin nerve-growth factor (NGF). NGF, similarly to CaV2.2, is a key regulator of peripheral nociception that mediates release of neurogenic molecules such as substance P and CGRP. Clinical studies using anti-NGF antibodies have shown a rapid and sustained pain reduction in patients (27), but long-term treatment has been reported to produce adverse effects in patients with advanced knee and hip osteoarthritis including peripheral edema, joint swelling and progressive osteoarthritis (28). Similarly, in a combined study analysis 21.3% of the ziconotide-treated patients reported abnormal gait as an adverse effect, compared to only 2% in the placebo group (29). This report also states that 9% of the ziconotide-group but none of the placebo-group developed arthralgia, i.e. joint pain. It is, at this point, unclear, if these effects are related to the intrathecal catheter or the actual compound.

The aim of our study was to model the blockade of CaV2.2 specifically in nociceptors during arthritis, rather than to mimic the actual situation of intrathecal administration of ziconotide. This is relevant in view of the future use of more stable cyclic forms of peptide conotoxins that can be administered orally rather than intrathecally (8). In general, the present challenge in pain research is to identify orally active CaV2.2-inhibitors that block the channel in a voltage-dependent manner (i.e. CRMP-2, NMED-160 and CNV2197944) to provide effective blocking only during high-frequency firing, which occurs in hypersensitive pain states (30). These novel use-dependent channel blockers, with oral availability, are now reported to be undergoing clinical evaluation for analgesia in neuropathic and inflammatory pain (30, 31).

Given the role of TNFα and RANKL in osteoclastogenesis, bone loss and joint destruction in arthritis (15–17, 32) we investigated these molecules in our ACIA model with Tg-MVIIA mice. New biological therapies targeting TNFα, e.g. infliximab, adalimumab and etanercept have been successful in severe cases of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) where patients do not show an adequate response to conventional drugs (33). RANKL is regulated by inflammatory cytokines including TNFα, dictates the differentiation, activity and survival of osteoclasts (34) and has been shown to be a marker and mediator of bone loss in rat models of inflammatory arthritis (32). Furthermore, postmenopausal osteoporosis and bone resorption have been reported to be successfully ameliorated by treatment with a monoclonal antibody to RANKL, denosumab (35). In our studies we observed for the first time that analgesic treatment, by CaV2.2 blockade with the conotoxin MVIIA, enhances RANKL-mediated joint destruction and progressive arthritis. This finding is intriguing. Additionally, after arthritis induction T cells from Tg-MVIIA mice were more prone to produce TNFα. Results from the intraarticular injection of soluble MVIIA point to a local, rather than central regulation of the pain blockade and we think that this is also the case for the regulation of RANKL and TNFα. We could not analyse the local, micromilieu (synovial fluid) for key molecules that are up- or down regulated in the absence of pain sensing, therefore we can only speculate on the mechanisms involved. Other studies suggest that CaV2.2 is involved in regulating monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), a cytokine that recruits monocytes, memory T cells, and dendritic cells to the sites of inflammation (36). In this context, CGRP has been shown to inhibit IL-1β-induced endogenous MCP-1 secretion (37). These observations together with our findings point to the possibility that disruption of the local release of peptides by CaV2.2 blockade might trigger an upregulation of RANKL, eventually leading to severe bone damage.

There is clear evidence that the local release of proinflammatory neuropeptides from peripheral terminals of afferent nerve fibers contributes to the development of neurogenic inflammation. However, several studies report tissue-dependent differences regarding the mechanisms engaged by neuropeptides to initiate and maintain the inflammatory response in the target tissue (36, 38). Upregulation of substance P and CGRP has been observed in joints after adjuvant-induced arthritis (39). In contrast, a reduction in the substance P-containing fibres in the synovium has also been reported (40), particularly in joints with heavy inflammatory infiltration, suggesting that the articular expression of nociceptive neuropeptides may be regulated differently at different stages of arthritis (41). It is possible that the basal activity of CaV2.2 is necessary for the proper homeostasis of the system. For instance, it has been speculated that inhibition of Ca2+ currents at sensory nerve endings may directly influence their sensitivity by changing the spike frequency adaptation (42, 43). It is also possible that other signalling events may take place upon reduction of CaV2.2 calcium influx.

In conclusion, blocking CaV2.2 -mediated pain neurotransmission in our arthritis model amplified inflammatory events to such an extent that RANKL expression was enhanced, thus promoting osteoclast differentiation and activation and concomitant bone erosion and deformation. Despite their obvious efficacy, the use of MVIIA peptide toxins and derivatives to alleviate pain in patients with inflammatory arthritis could be very harmful and ought to be assessed with extreme care. Further insight into the role of CaV2.2 channel activity and hyperactivity in the regulation of the complex crosstalk between the immune system and the nociceptive pathways might provide safer analgesic alternatives for the treatment of this most common cause of disability.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Annika Stürzebecher, Sebastian Auer and Monika Schwarz for technical assistance; Arnd Heuser, Martin Taube and Stefanie Schelenz for heart rate measurements, as well as Holger Bang from Orgentec Diagnostika GmbH for the MCV ELISA kits. Dr. C. Loddenkemper from Charité Berlin for expert advice and determination of the multi-parameter arthritis score and Dr. Jessica L. Ables for help with the biostatistics analyses.

Funding:

This work was supported by the Helmholtz Association 31-002 (I.I.-T.), grants from the German Research Foundation (DFG): the Collaborative Research Centres SFB665 (I.I.-T) and SFB 650 (G.M., M.L.), the European Union Sixth Framework Program Grant No. LSHB-CT-2005–518167 (INNOCHEM, M.L.) and the NIH/NIDA 1P30 DA035756 (I.I.-T)

Abbreviations

- AALAC

Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care

- ACIA

Antigen- and Collagen-Induced Arthritis

- ACPA

anti–citrullinated peptide antibodies

- AIDS

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- BAC

bacterial artificial chromosome

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CaV

N-type voltage-gated calcium channel

- CFA

Freund's complete adjuvant

- CGRP

calcitonin-gene related peptide

- DMARD

disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

- DRG

dorsal root ganglia

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- HE

hematoxylin and eosin

- ICFA

Freund's incomplete adjuvant

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

- IL-17

interleukin-17

- mBSA

methylated bovine serum albumin

- MCP-1

monocyte chemotactic protein-1

- MCV

mutated citrullinated vimentin

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- MVIIA

a ω-conotoxin blocking N-type voltage-gated calcium channels

- NGF

nerve-growth factor

- NSAIDs

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PE

phycoerythrin

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- PTx

pertussis toxin

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- RANKL

receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand

- t-MVIIA

tethered MVIIA

- TMB

tetramethylbenzidine

- Tg-MVIIA

transgenice MVIIA mice

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- wt

wild type.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions:

U.B. performed the majority of the experiments S.F. and B.A-F performed RT-PCR experiments and helped with figure preparation J.G. helped with arthritis experiments; I.I.-T., G.M. and M.L supervised experiments. U.B., I.I.-T. and G.M. planned and designed experiments I.I.-T. conceived the project. I.I.-T. and U.B. wrote the manuscript with help from G.M. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Firestein GS. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2003;423(6937):356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature01661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kosek E, Ordeberg G. Abnormalities of somatosensory perception in patients with painful osteoarthritis normalize following successful treatment. European journal of pain. 2000;4(3):229–238. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2000.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kindler LL, Bennett RM, Jones KD. Central sensitivity syndromes: mounting pathophysiologic evidence to link fibromyalgia with other common chronic pain disorders. Pain management nursing : official journal of the American Society of Pain Management Nurses. 2011;12(1):15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee YC, Nassikas NJ, Clauw DJ. The role of the central nervous system in the generation and maintenance of chronic pain in rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia. Arthritis research & therapy. 2011;13(2):211. doi: 10.1186/ar3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snider WD, McMahon SB. Tackling pain at the source: new ideas about nociceptors. Neuron. 1998;20(4):629–632. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dray A, Read S. Arthritis and pain. Future targets to control osteoarthritis pain. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2007;9(3):212. doi: 10.1186/ar2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y-X, Gao D, Pettus M, Phillips C, Bowersox SS. Interactions of intrathecally administered ziconotide, a selective blocker of neuronal N-type voltage-sensitive calcium channels, with morphine on nociception in rats. Pain. 2000;84(2–3):271–281. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carstens BB, Clark RJ, Daly NL, Harvey PJ, Kaas Q, Craik DJ. Engineering of conotoxins for the treatment of pain. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(38):4242–4253. doi: 10.2174/138161211798999401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Auer S, Sturzebecher AS, Juttner R, Santos-Torres J, Hanack C, Frahm S, et al. Silencing neurotransmission with membrane-tethered toxins. Nat Methods. 2010;7(3):229–236. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schellekens GA, Visser H, de Jong BA, van den Hoogen FH, Hazes JM, Breedveld FC, et al. The diagnostic properties of rheumatoid arthritis antibodies recognizing a cyclic citrullinated peptide. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2000;43(1):155–163. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<155::AID-ANR20>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harre U, Georgess D, Bang H, Bozec A, Axmann R, Ossipova E, et al. Induction of osteoclastogenesis and bone loss by human autoantibodies against citrullinated vimentin. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122(5):1791–1802. doi: 10.1172/JCI60975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baddack U, Hartmann S, Bang H, Grobe J, Loddenkemper C, Lipp M, et al. A chronic model of arthritis supported by a strain-specific periarticular lymph node in BALB/c mice. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1644. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldmann M, Maini RN. Discovery of TNF-alpha as a therapeutic target in rheumatoid arthritis: preclinical and clinical studies. Joint Bone Spine. 2002;69(1):12–18. doi: 10.1016/s1297-319x(01)00335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schett G. Review: Immune cells and mediators of inflammatory arthritis. Autoimmunity. 2008;41(3):224–229. doi: 10.1080/08916930701694717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong YY, Feige U, Sarosi I, Bolon B, Tafuri A, Morony S, et al. Activated T cells regulate bone loss and joint destruction in adjuvant arthritis through osteoprotegerin ligand. Nature. 1999;402(6759):304–309. doi: 10.1038/46303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shigeyama Y, Pap T, Kunzler P, Simmen BR, Gay RE, Gay S. Expression of osteoclast differentiation factor in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(11):2523–2530. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11<2523::AID-ANR20>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pettit AR, Walsh NC, Manning C, Goldring SR, Gravallese EM. RANKL protein is expressed at the pannus-bone interface at sites of articular bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2006;45(9):1068–1076. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Just S, Leipold-Buttner C, Heppelmann B. Histological demonstration of voltage dependent calcium channels on calcitonin gene-related peptide-immunoreactive nerve fibres in the mouse knee joint. Neurosci Lett. 2001;312(3):133–136. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wichner K, Fischer A, Winter S, Tetzlaff S, Heimesaat MM, Bereswill S, et al. Transition from an autoimmune-prone state to fatal autoimmune disease in CCR7 and RORgammat double-deficient mice is dependent on gut microbiota. Journal of autoimmunity. 2013;47:58–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaible H-G, Ebersberger A, Von Banchet GS. Mechanisms of Pain in Arthritis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2002;966(1):343–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiu IM, von Hehn CA, Woolf CJ. Neurogenic inflammation and the peripheral nervous system in host defense and immunopathology. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(8):1063–1067. doi: 10.1038/nn.3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caceres AI, Brackmann M, Elia MD, Bessac BF, del Camino D, D’Amours M, et al. A sensory neuronal ion channel essential for airway inflammation and hyperreactivity in asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(22):9099–9104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900591106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engel MA, Leffler A, Niedermirtl F, Babes A, Zimmermann K, Filipovic MR, et al. TRPA1 and substance P mediate colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(4):1346–1358. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine JD, Clark R, Devor M, Helms C, Moskowitz MA, Basbaum AI. Intraneuronal substance P contributes to the severity of experimental arthritis. Science. 1984;226(4674):547–549. doi: 10.1126/science.6208609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ostrowski SM, Belkadi A, Loyd CM, Diaconu D, Ward NL. Cutaneous denervation of psoriasiform mouse skin improves acanthosis and inflammation in a sensory neuropeptide-dependent manner. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(7):1530–1538. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sluka KA, Rasmussen LA, Edgar MM, O’Donnell JM, Walder RY, Kolker SJ, et al. Acid-sensing ion channel 3 deficiency increases inflammation but decreases pain behavior in murine arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(5):1194–1202. doi: 10.1002/art.37862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewin GR, Lechner SG, Smith ES. Nerve growth factor and nociception: from experimental embryology to new analgesic therapy. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2014;220:251–282. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-45106-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seidel MF, Lane NE. Control of arthritis pain with anti-nerve-growth factor: risk and benefit. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012;14(6):583–588. doi: 10.1007/s11926-012-0289-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment Report (EPAR) for Authorized Medicinal Products for Human Use. Scientific Discussion. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winquist RJ, Pan JQ, Gribkoff VK. Use-dependent blockade of Cav2.2 voltage-gated calcium channels for neuropathic pain. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2005;70(4):489–499. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brittain JM, Duarte DB, Wilson SM, Zhu W, Ballard C, Johnson PL, et al. Suppression of inflammatory and neuropathic pain by uncoupling CRMP-2 from the presynaptic Ca2+ channel complex. Nat Med. 2011;17(7):822–829. doi: 10.1038/nm.2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stolina M, Adamu S, Ominsky M, Dwyer D, Asuncion F, Geng Z, et al. RANKL is a Marker and Mediator of Local and Systemic Bone Loss in Two Rat Models of Inflammatory Arthritis. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2005;20(10):1756–1765. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lloyd S, Bujkiewicz S, Wailoo AJ, Sutton AJ, Scott D. The effectiveness of anti-TNF-alpha therapies when used sequentially in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 2010;49(12):2313–2321. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, Kelley MJ, Dunstan CR, Burgess T, et al. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998;93(2):165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewiecki EM. New targets for intervention in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(11):631–638. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tokuhara N, Namiki K, Uesugi M, Miyamoto C, Ohgoh M, Ido K, et al. N-type calcium channel in the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285(43):33294–33306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.089805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li W, Wang T, Ma C, Xiong T, Zhu Y, Wang X. Calcitonin gene-related peptide inhibits interleukin-1beta-induced endogenous monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 secretion in type II alveolar epithelial cells. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 2006;291(3):C456–C465. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00538.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kilo S, Harding-Rose C, Hargreaves KM, Flores CM. Peripheral CGRP release as a marker for neurogenic inflammation: a model system for the study of neuropeptide secretion in rat paw skin. Pain. 1997;73(2):201–207. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garrett NE, Kidd BL, Cruwys SC, Tomlinson DR. Changes in preprotachykinin mRNA expression and substance P levels in dorsal root ganglia of monoarthritic rats: comparison with changes in synovial substance P levels. Brain Res. 1995;675(1–2):203–207. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00066-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Konttinen YT, Hukkanen M, Segerberg M, Rees R, Kemppinen P, Sorsa T, et al. Relationship between neuropeptide immunoreactive nerves and inflammatory cells in adjuvant arthritic rats. Scand J Rheumatol. 1992;21(2):55–59. doi: 10.3109/03009749209095068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keeble JE, Brain SD. A role for substance P in arthritis? Neurosci Lett. 2004;361(1–3):176–179. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mantyh PW, Yaksh TL. Sensory neurons are PARtial to pain. Nat Med. 2001;7(7):772–773. doi: 10.1038/89880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Just S, Heppelmann B. Voltage-gated calcium channels may be involved in the regulation of the mechanosensitivity of slowly conducting knee joint afferents in rat. Exp Brain Res. 2003;150(3):379–384. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1465-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]