Abstract

In catamenial epilepsy, seizures exhibit a cyclic pattern that parallels the menstrual cycle. Many studies suggest that catamenial seizures are caused by fluctuations in gonadal hormones during the menstrual cycle, but this has been difficult to study in rodent models of epilepsy because the ovarian cycle in rodents, called the estrous cycle, is disrupted by severe seizures. Thus, when epilepsy is severe, estrous cycles become irregular or stop. Therefore, we modified kainic acid (KA)- and pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus (SE) models of epilepsy so that seizures were rare for the first months after SE, and conducted video-EEG during this time.

The results showed that interictal spikes (IIS) occurred intermittently. All rats with regular 4-day estrous cycles had IIS that waxed and waned with the estrous cycle. The association between the estrous cycle and IIS was strong: if the estrous cycles became irregular transiently, IIS frequency also became irregular, and when the estrous cycle resumed its 4-day pattern, IIS frequency did also. Furthermore, when rats were ovariectomized, or males were recorded, IIS frequency did not show a 4-day pattern. Systemic administration of an estrogen receptor antagonist stopped the estrous cycle transiently, accompanied by transient irregularity of the IIS pattern. Eventually all animals developed severe, frequent seizures and at that time both the estrous cycle and the IIS became irregular. We conclude that the estrous cycle entrains IIS in the modified KA and pilocarpine SE models of epilepsy. The data suggest that the ovarian cycle influences more aspects of epilepsy than seizure susceptibility.

Keywords: seizure, epilepsy, kainic acid, animal model, hormone, women, neuropathology

INTRODUCTION

Women with epilepsy often report that they have seizures which increase in frequency or severity during a certain time of their menstrual cycle, a condition called catamenial epilepsy [1–6]. Typically the exacerbation of seizures occurs at the end of each cycle, the so-called peri-menstrual period, but it can occur mid-cycle, during the peri-ovulatory period, or during anovulatory cycles [7].

The incidence of catamenial epilepsy varies extensively in epidemiological reports but is a substantial clinical issue not only in the U.S. but throughout the world [4,8–11]. Defined as a two-fold or greater increase in average daily seizure frequency during a predefined menstrual phase [4], approximately 1/3 of women with medically-refractory focal epilepsy syndromes would meet the definition [4,7,12]. However, catamenial epilepsy is also difficult to study, limiting the understanding of mechanisms and development of new treatments.

One reason it is difficult to study catamenial epilepsy is the long duration of the menstrual cycle (28 days), making recruitment and retention difficult for a clinical study. Antiseizure drugs (ASDs) make it hard to dissociate underlying mechanisms from potential seizure exacerbation due to waning drug levels at the end of the menstrual cycle. At the end of the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, prior to the time when catamenial seizure exacerbation typically occurs, there are changes in water balance and drug clearance that can lower blood levels of ASDs [13–16].

Rodent models can potentially circumvent these issues. One reason is that rodents have a short ovarian cycle, a 4-day cycle called the estrous cycle. The short cycle makes it possible to evaluate many cycles in a relatively short space of time. Furthermore, concurrent ASDs are not required for animal studies. However, estrous cycles are typically disrupted by severe convulsive seizures. This problem has been documented in the kindling model [17] and after status epilepticus (SE; [18–21]) in rodents. Therefore, we attempted to induce epilepsy in a way that would allow estrous cycles to be maintained.

First we chose SE as the method to induce epilepsy. The reason is that SE causes a syndrome in adult rats that simulates temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), where catamenial epilepsy is common [12,22,23]. Therefore, SE-induced epilepsy might allow the best opportunity to gain insight into catamenial epilepsy. Next we chose a method to modify SE and its consequences so that estrous cycles would be normal after SE. Our approach was based on our observations that SE normally caused substantial neuronal damage in the adult female rat, including the hypothalamus, which is an area that is critical to the estrous cycle because of its role in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. We reasoned that reducing the severity of SE to decrease neuronal damage caused by SE would increase the likelihood that estrous cycles would be preserved after SE.

After the milder form of SE, animals had spontaneous convulsive seizures but in many animals they were rare for the first months after SE. In those animals, estrous cycles were preserved. We report here the results of the studies of the EEG during the time when seizures were rare and estrous cycles were normal. The results show a cyclic pattern of interictal spikes (IIS) that increased in frequency, often dramatically, in parallel to the estrous cycle. The results suggest that a rhythm associated with the estrous cycle occurs in female rodents after SE and greatly influences generation of IIS. The implication is that cyclic changes in brain excitability may be underestimated because most investigators focus only on seizure susceptibility.

METHODS

Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY) or Charles River (Kingston, NY) and bred in-house. They were weaned at 21–23 days of age and then housed with 1–2 others in standard rat cages with corn cob bedding and a 12 hr light:dark cycle (lights on, 7:00 a.m.). Standard rat chow (Purina 5001, W.F. Fisher, Somerville, NJ) and water were provided ad libitum. Animal care and use met the National Institutes of Health and New York State guidelines. All chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated.

Induction of SE

Animals were placed 1/cage at approximately 9:00 a.m. SE was induced either by KA or pilocarpine. For KA-induced SE, only KA (12 mg/kg, s.c.) was administered.

For SE induction using pilocarpine, animals were injected first with the muscarinic cholinergic antagonist atropine methylbromide (1 or 2.5 mg/kg, s.c.) to reduce the peripheral effects of pilocarpine. Pilocarpine hydrochloride (380 mg/kg, s.c.) was injected 30 min after atropine. In some of the animals, the selective estrogen receptor modulator raloxifene hydrochloride (2 mg/kg, s.c.) was injected immediately after atropine, but other procedures were the same. As previously described, raloxifene was used because it decreases the adverse effects of pilocarpine-induced SE on reproductive function in adult female rats [18].

Although pre-treatments were different for the pilocarpine-treated rats, all pilocarpine-treated animals that exhibited regular estrous cycles after SE were similar: these rats showed IIS that had a cyclic pattern that paralleled the estrous cycle. Therefore, the results from pilocarpine-treated rats are presented together in the Results.

A modified Racine scale was used to define behavioral seizures. This 5 stage scale was only modified with respect to stage 3. Instead of the original description by Racine (forelimb clonus [24]), stage 3 was defined as rearing with tonic-clonic movements of one forelimb. There were two reasons for our modification of the Racine stage 3 seizure: 1) forelimb clonus was often difficult to define if forelimbs were under the body; 2) the modified stage 3 always preceded stage 4. In the Results, we use the phrase “severe seizures” to refer to stages 4–5.

SE was defined as the first convulsive seizure that was ≥stage 3 and the animal did not resume normal behavior for at least 5 min. Ten to 20 minutes after the onset of SE, pentobarbital (30 mg/kg, i.p.) was injected to decrease SE severity. All animals were treated with dextrose-lactated Ringer s solution (3 ml s.c.; Henry Schein) 1–4 hrs after the first dose of pentobarbital and the following day.

In most animals, the first dose of pentobarbital led to a supine posture with trembling, i.e. a major reduction in convulsive behaviors, and did so within 30 min. However, in a subset of animals, an additional dose of pentobarbital (15 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered 30 min after the first dose because the first dose did not appear to have an effect. The females in this subset did not continue to show regular estrous cycles after SE so they are not included in the Results section where female rats are discussed that had a 4-day cycle in IIS frequency. Two males were in this subset of animals and they are included in the Results sections when males are discussed that had IIS and chronic seizures.

Electrode implantation

Subjects were initially anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine solution (i.p.) followed by isoflurane by inhalation (Isotec, Surgivet; Dublin, OH). After shaving hair on the scalp (Model 8900; Wahl USA; Sterling, IL), and lubricating eyes (Altalube; Butler Schein, Dublin, OH), animals were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (Model 502603; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) on a heating pad with rectal probe for control of body temperature using a heater with a feedback circuit to maintain temperature at 37°C (Homeothermic temperature controller; Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). A scalp incision was used to expose the dorsal surface of the skull, and holes were drilled (Model C300; Grobet USA, Carlstadt, NJ; 0.7 mm drill bits; Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA) to implant 8 electrodes: 4 epidural electrodes (bone skull screws; Frederick Haer, Bowdoin ME) and 2 bipolar depth electrodes made in-house (twisted 75 μm-diameter Teflon-coated stainless steel wire; California Fine Wire, Grover Beach, CA). Epidural electrodes were placed bilaterally over the frontal cortex (FC) and occipital cortex (OC). Coordinates for FC electrodes were: −1.0 mm posterior to Bregma and 3.0 mm lateral to the midline. For OC electrodes, coordinates were −6.0 mm and 3.0 mm. One ground electrode was implanted 1.0 mm anterior to Bregma and 3.0 mm lateral to the midline. The reference electrode was 1.0 mm posterior to Lambda and 1.5 mm lateral to the midline. Depth electrodes were located in dorsal hippocampus (1/hippocampus) at the following coordinates: −3.5 mm posterior to Bregma, 3.5 mm lateral to the midline, and 3.5 mm below dura. Electrodes were inserted into a 16-pin connector (Digi-key; Thief River Falls, MN), and the connector was fixed to the skull (dental cement; Henry Schein Inc, Melville, NY). Animals were treated with the analgesic buprenorphine and yohimbine i.p. to facilitate recovery from anesthesia immediately after surgery.

Pharmacology

Drugs used for induction of SE

KA (Milestone Pharmatech, New Brunswick, NJ), atropine methylbromide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and pilocarpine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved in 0.9% NaCl. Raloxifene hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich). Pentobarbital was purchased as a solution (50 mg/ml; Nembutal; Henry Schein Inc., Melville, NY), as was diazepam (5 mg/ml; Baxter Healthcare; New Providence, NJ) and stored at room temperature. ICI 182,780 (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) was dissolved in corn oil (vehicle; Mazola, ACH Food Companies, Summit, IL) as a 10 mM stock solution and stored at room temperature in the dark until use.

Drugs used for electrode implantation

Ketamine/xylazine solution (Sigma-Aldrich) was a 80mg/ml ketamine and 6mg/ml xylazine solution and the dose was 0.1 ml/100g. Buprenorphine (Henry Schein) dose was 0.05 mg/kg. Yohimbine (Henry Schein) dose was 2 mg/kg.

Video-EEG recording

Subjects were allowed 1 week to recover from surgery. During recording, animals were allowed to move freely while attached to a transmitter for digital telemetry (Bio-Signal Corp., Brooklyn, NY) plugged into the pin connector on the skull. The transmitter was attached by a cable to a commutator (#SL2C; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) to allow freedom of movement. Recordings were synchronized with a video camera (Axis Systems, Auburn Hills, MI). EEG was acquired at 2 kHz using AcqKnowledge (version 4.1; Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA) or Insight II (Persyst, Prescott, AZ).

Recordings were made for 1–2 hrs during the morning (between 8:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m.). During recordings, an investigator marked the times in the EEG record that were accompanied by exploration, behavioral arrest, or sleep. Exploration was defined by walking (e.g., walking across the cage), sniffing, and other movements associated with exploring the cage. Behavioral arrest was defined as a spontaneous pause in behavior when there was a frozen posture and the eyes were open. For the purposes of this study, spontaneous behavioral arrest is the same as spontaneous immobility. At this time, theta oscillations in hippocampus were reduced or absent, consistent with the emergence of distinct hippocampal EEG patterns during this behavioral state, i.e., sharp-wave ripples (SPW-R), described elsewhere [25–27]. Sleep was defined by closed eyes, absence of movement, with an increase in EEG activity in the epidural electrodes. Occasionally animals that were in behavioral arrest lowered their eyelids slowly; because this behavior suggests a transition to sleep it was defined as sleep if cortical electrodes showed increased EEG activity (e.g., delta rhythm), but defined as behavioral arrest if not.

Between EEG recording sessions, some animals were video-recorded so that convulsive seizures could be monitored. For this purpose, the transmitter was detached and animals were returned to their home cage, with overhead video camera (Axis Systems). Recordings were reviewed post-hoc using a VLC media player (VideoLan Organization; videolan.org). The investigator reviewing the video files was blinded to the estrous cycle stage.

Data analysis of EEG

Terminology

Investigators vary in the use of terms such as spike, IIS, and sharp wave. Because our subjects were rats, and our electrodes included depth electrodes within hippocampus, we avoided the term sharp wave because the term ‘sharp wave’ is used for recordings from rat hippocampus to designate a deflection in the EEG that is sharp (50–100 msec duration) and occurs normally in behavioral arrest or sleep, where it is considered important to memory consolidation (Buzsaki, 1986; 1990). In contrast, IIS are only found in rats between seizures, so they are pathological. They were recorded both in hippocampus and other electrodes. Strictly speaking, IIS were defined as simultaneous rapid (50–200 msec) deflections that occurred in all electrodes and were large (peak to peak amplitude, >5x the amplitude of the baseline noise) in the majority (≥5) of electrodes and in both hemispheres. The term “spike” is not used in this study to avoid confusion.

IIS quantification

To quantify IIS, a blinded investigator manually reviewed the data for each recording session. IIS frequency for a given recording session (typically 1–2 hrs) was determined by dividing the number of IIS for each period of a given behavioral state (e.g., exploration) by the total duration of time spent in that behavioral state.

Whether IIS frequency data exhibited a regular cyclic pattern was tested by fitting the data to the following modified sine wave squared equation, using the Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm:

Where IIS freq. is the number of interictal spikes per minute, d and d0 are the day of the recording and the first day of recording, respectively, A is the predicted IIS frequency maximum and B the predicted wave frequency. We used this equation to fit the data, based on the null hypothesis that IIS might vary in a cylic, regular daily pattern, without ever becoming negative (since IIS frequency can never be less than zero). The sine wave squared equation describes such a relationship. Therefore, we reasoned that if the data did indeed follow a cyclical pattern, we should be able to fit it using this relationship and obtain a statistically significant regression coefficient. If not, then the Marquardt-Levenberg curve fit procedure would not yield a significant regression coefficient and the hypothesis of regular cyclicity would have to be rejected.

The parameters in the curve fit equation were all allowed to vary independently during curve fitting: none were constrained to force fitting to a pre-determined pattern. Regressions were analyzed statistically by ANOVA. Significance limits for the regression analysis were set at p<0.05. All curve fits were carried out using the functions incorporated into Sigmaplot 10 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA).

Ovariectomy (Ovx)

Animals were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and the animal was maintained at 37°C (for details see Electrode implantation, above). With the animal on its abdomen, the lower back was shaved with a small animal shaver (described above) and the area was swabbed with Betadine (Henry Schein). A midline incision was made with a sterile scalpel and the skin deflected from the area just over each ovary. The abdominal wall was cut over each ovary with a ¼″-long incision and each ovary was removed. A sterile suture (Dermalon 3–0, Henry Schein) was used to ligate the ovary at the junction with the uterus. The incision in the abdominal wall was closed with sterile sutures, and the midline incision was closed with wound clips (EZ clip wound closures, Stoelting Co., Wood Dale IL), followed by treatment of the area with Betadine. Animals were placed under a heat lamp until they were ambulatory. No recordings were made for 4–7 days after surgery, to allow for recovery.

The Estrous Cycle

Terminology

For the purposes of this study, the estrous cycle was defined as two days of diestrous [the first called metestrus (or diestrus 1) and the second called diestrus 2, followed by a day called proestrus and then another day called estrus. As shown by measurements every 2 hrs in the Sprague-Dawley rat, the pre-ovulatory surge in 17β-estradiol begins with a slow increase in serum levels of 17β-estradiol during the morning of diestrus 2 and continuing overnight until proestrous morning. Subsequently there is a rapid surge in serum levels of 17β-estradiol during the morning of proestrus [28,29]. Progesterone begins to rise at midday of proestrus, peaks in the evening and then dramatically falls until approximately 5:00 a.m. of estrous morning [28,29]. Therefore, the time of the estrous cycle that is analogous to the periovulatory period in women (day 14 of the 28-day menstrual cycle) is proestrous morning [28]. Although direct comparison is difficult, because the rat does not have a true luteal phase to its cycle, the time of the estrous cycle that is hormonally closest to the perimenstrual period is early estrous morning, immediately after progesterone levels have both fallen [28].

Vaginal cytology

Vaginal cytology was examined as described previously [30] (for additional details see [31,32]) and interpreted based on the hormonal fluctuations accompanying the day-to-day variation in cell types sampled from the vaginal wall. Three types of cells were discriminated, leukocytes (predominant on metestrus and diestrus 2), epithelial cells, and cornified epithelial cells. The latter two cell types dominated the vaginal sample on proestrus and estrus. A typical pattern for proestrous morning was predominantly epithelial cells and a smaller contribution of cornified epithelial cells. A typical pattern for estrous morning was the converse: predominantly cornified epithelial cells, and a smaller contribution of epithelial cells. A 4-day cycle was defined by two days of diestrus when leukocytes were dominant (metestrus) or similar in proportion to other cell types (diestrus 2), followed by two days when epithelial cells and cornified epithelial cells were the primary cell types (proestrus and estrus). Two consecutive 4-day cycles were required before considering an animal for this study. Acyclicity was defined by any other pattern, e.g., only one day where epithelial or cornified epithelial cells were the major cell type, instead of two days. Even if only one cycle failed to meet the 4-day pattern, an animal was defined as acyclic. The reason for the strict definition was based on previous studies of hippocampal slices from female Sprague-Dawley rats, where rats with strict 4-day estrous cycles showed a 4-day pattern in electrophysiological measures of excitability in area CA3 but even a small disruption of the 4-day estrous cycle disrupted the electrophysiological pattern in hippocampus [30]. Importantly, we measured estradiol and progesterone levels in a subset of animals to confirm the predictions of estrous cycle stage based on vaginal cytology [30].

Neuropathology

Animals were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital at a high dose (50 mg/kg, i.p.) and transcardially-perfused with 0.9% NaCl (3 min) followed by fixative (4% paraformaldehdye, pH 7.4) for 5 min. Brains were removed after 2–4 hrs and placed in 4 % paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Using one hemisphere, sections (50 μm) were cut horizontally; every 300 μm, one section was selected for cresyl violet, the next for NeuN immunohistochemistry, and the next for fluorojade B. The other hemisphere was cut in the coronal plane and sections were selected in the same way. Because the coronal sections were transected with electrode tracks, horizontal sections were used for quantification of anatomical findings.

NeuN immunohistochemistry used free-floating sections that were gently mixed on a rotator (Clinical rotator; Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). After treating sections for 30 min with 0.25% Triton-X 100, sections were washed 3 × (5 min each) in 0.1% Triton-X 100 in 0.1M Tris buffer (“Tris A”), and then blocked with 5% normal horse serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 min, followed by washes in Tris A (3 × 5 min) and then “Tris B” (Tris A with 0.05% bovine serum albumin). Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C on a rotator with a mouse monoclonal antibody to NeuN (1:10,000; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) diluted in Tris A followed by washes in Tris A (3 × 5 min) and incubation in biotinylated horse anti-mouse secondary antibody (Vector; 1:400) diluted in Tris A followed by washes in Tris A (3 × 5 min). Sections were then incubated in ABC solution diluted in Tris A according to the Manufacturer s instructions (ABC Standard Kit, Vector) followed by washes in Tris (3 × 5 min) and incubation in diaminobenzidine (0.022%) with 0.2 % ammonium chloride, 0.1% glucose oxidase, 0.8% D(+)-glucose and 5 mM NiCl2 in 0.1 M Tris buffer. To ensure that labeling for NeuN was detected if it was present, sections were allowed to incubate with DAB for a long enough time that the background started to accumulate detectable stain. The reaction was stopped by washing sections in 0.1 M Tris buffer. Sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides, dehydrated in a series of ethanol (Pharmaco-Aaper, Shelbville, KY) solutions (5 min each 70%, 90%, 95%, 100% and then 10 min in fresh 100%, cleared in xylene, and coverslipped in Permount (Fisher Scientific).

Fluorojade B (Histochem Inc., Jefferson, AK) staining was conducted as described elsewhere (www.scharfmanlab.com/Protocols). In brief, sections were mounted on coated slides (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD) and allowed to dry overnight. After immersing in 100% ethanol (3 min), and 70% ethanol (1 min) slides were placed in dH2O for 1 min and then a solution of 0.06% KMnO4 in dH2O, followed by 0.001% fluorojade B. The steps following ethanol were conducted in the dark. After washing in dH2O (3 × 1 min), slides were allowed to dry overnight in the dark, treated with xylene (3 × 1 min) and coverslipped in DPX (Sigma-Aldrich). Slides were stored in the dark at 4°C.

For cresyl violet, sections were mounted on gelatin-treated slides, allowed to dry for 24 hrs, and dehydrated in a series of graded ethanols. Sections were rehydrated by reversing the dehydration steps and then slides were stained with 0.1% (w/v) cresyl violet in dH2O for 1 min. If staining appeared too dark, acetic acid (0.01%; Fisher Scientific) was used to destain (i.e., so that cells were stained and areas with no cells were not). Sections were then dehydrated and slides were cleared in xylene and cover-slipped with Permount.

Slides were viewed on a microscope with brightfield and fluorescence capability (Olympus BX61; Olympus of America, Center Valley, PA). Photographs were taken with a digital camera (RET 2000R-F-CLR-12, Q Imaging, Surrey, BC, Canada) using Q imaging software.

Quantification of NeuN-ir and fluorojade B-stained sections was performed using ImageJ (www.rsd.nih/imagej). Investigators were blinded to condition. First, micrographs were taken at 4x magnification. The same light settings were used for all sections labeled with the same antibody/marker (e.g., NeuN or fluorojade-B). Sections were 300 μm apart and the results from 3 sections per animal through the middle third of the hippocampus were averaged.

For NeuN, micrographs were first converted to 8 bit gray-scale and then binary images. Regions of interest (ROI) were outlined and then the area fraction was calculated. The area fraction was the part of the ROI area above threshold, expressed as a percent of total ROI area. Threshold was selected automatically in Image J to minimize experimenter bias. Notably, the threshold agreed with visual inspection, i.e., NeuN-ir was above threshold and background staining was below threshold.

The ROIs were defined by landmarks that were clear in all sections. For the granule cell layer, the entire cell layer was outlined. For the CA1–CA3 cell layer, the entire cell layer was outlined with the termination in CA1 defined as the location where the cell layer becomes dispersed at the junction with the subiculum. The pre/parasubiculum was the area between the pia, underlying white matter, the subiculum and the medial entorhinal cortex (MEC). The MEC was demarcated by the pia, white matter, parasubiculum and the lateral entorhinal cortex (LEC). These areas were defined based on cytoarchitectonics in an atlas of the adult rat brain [33]. For fluorojade B, the ROIs from adjacent NeuN-stained sections were used because cytoarchitecture was absent in flourojade B-stained sections and areas hard to define as a result. As an alternative method for quantification, ImagePro (Media Cybernetics) was used to count cells that were fluorojade B-positive within the MEC. For this method, a threshold was used so that cells that were fluorojade B-positive were distinguished as objects and counted. Cells that were overlapping were often counted as a single object, leading to an underestimate of cells in areas with extensive neuronal damage. For this reason, the method was secondary.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Student t-tests, Fisher exact tests (when sample size was <10) and Chi-squared tests (when sample size was >10), were conducted using Prism (Graph Pad Software, La Jolla, CA) with a criterion for statistical significance of p<0.05. To compare mean IIS frequency across the 4 days of the estrous cycle, the Box-Cox method was used with an added constant of 1, to correct for inhomogeneity of variance and the fact that some animals exhibited no IIS on some of the days that were recorded. The transformed data were analyzed by ANOVA followed by the Student-Newman Keuls multiple range test.

RESULTS

SE-induced epilepsy in female rats

The majority of animals in this study had KA-induced SE to induce epilepsy. KA was tested in 66 female rats (64.2 ± 0.9 days) and most female rats had SE after KA (57/66 or 86.4%; Figure 1A1-2). Morbidity and mortality were low (Figure 1A1-2). The incidence of SE in females was not significantly different from males (Chi-squared test, p = 0.837; Figure 1A2) and SE incidence did not vary significantly with the cycle stage (Chi-squared test, p=0.648; Figure 1A3).

Figure 1. Kainic acid (KA)- and pilocarpine-induced SE in female rats and its use to study the relationship between the estrous cycle and the EEG.

A. 1–2. KA injection led to a high incidence of SE. Black: animals with SE; grey: animals that had few or no seizures (i.e., they did not have SE); white: animals that died.

3. Incidence of SE at different estrous cycle stages. Numbers above the bars are (numbers of animals with SE)/(total number of animals tested). There were no significant differences (Chi-squared test, p>0.05).

B. Experimental procedures. 1. Females with regular estrous cycles were injected with pilocarpine or KA and electrodes were implanted approximately 1 month later. After 1 week for recovery, animals were recorded daily in the morning and vaginal cytology was used to confirm that estrous cycles were maintained. Mon = month. 2. Ovx females had approximately 1 week for recovery and then were recorded daily. 3. Males were treated like intact females except there was no cytologic examination.

4. Pharmacology followed the same procedures as in D1, except for drug injections at the arrows. The drug injections were made prior to the recording session of that day. 5. A cohort of animals was treated the same as for #1 but were perfusion-fixed 3 days after KA injection.

Pilocarpine-treated rats were used as a second method to induce epilepsy. Although there were no detectable differences between these two methods on the chronic EEG (see below), there were differences in SE. For pilocarpine treatment, 65 female rats were used at a similar time of life as those rats experienced KA treatment (soon after puberty or young adulthood, approximately 2–3 months-old, 86.7 ± 2.8 days). Unlike KA, many female rats that were treated with pilocarpine did not enter SE (51/65 or 78.4%; Supplemental Figure 1A). SE in females was rare regardless of cycle stage (Fisher s Exact test, p=0.946). Notably, females and males were similar in the incidence of SE after KA injection but there were sex differences in response to pilocarpine with lower incidence in females (Supplemental Figure 1A; [34]). The incidence of SE was independent of treatment with raloxifene (Supplemental Figure 1B; (22)). Morbidity and mortality with KA was low so raloxifene was not used.

IIS in rats after SE

In the first months after SE, female rats exhibited spikes that were present simultaneously in all leads and were typically very large in amplitude (e.g., Figure 2A). These spikes were extremely similar morphologically to IIS observed between seizures (6 months after KA). In hippocampal recordings, ripples (80–150 Hz) occurred at the peaks of the IIS, and sometimes high frequency oscillations (HFOs; Supplemental Figure 2). Therefore, IIS were similar to IIS in patients with epilepsy [37–39]. For these reasons, the term IIS is used. However, it is recognized that the “IIS” in some animals where seizures were not detected could be “preictal” rather than interictal. Preictal spikes have been reported before the first spontaneous seizure (i.e., epilepsy) after SE in male rats (Bernard, Staley).

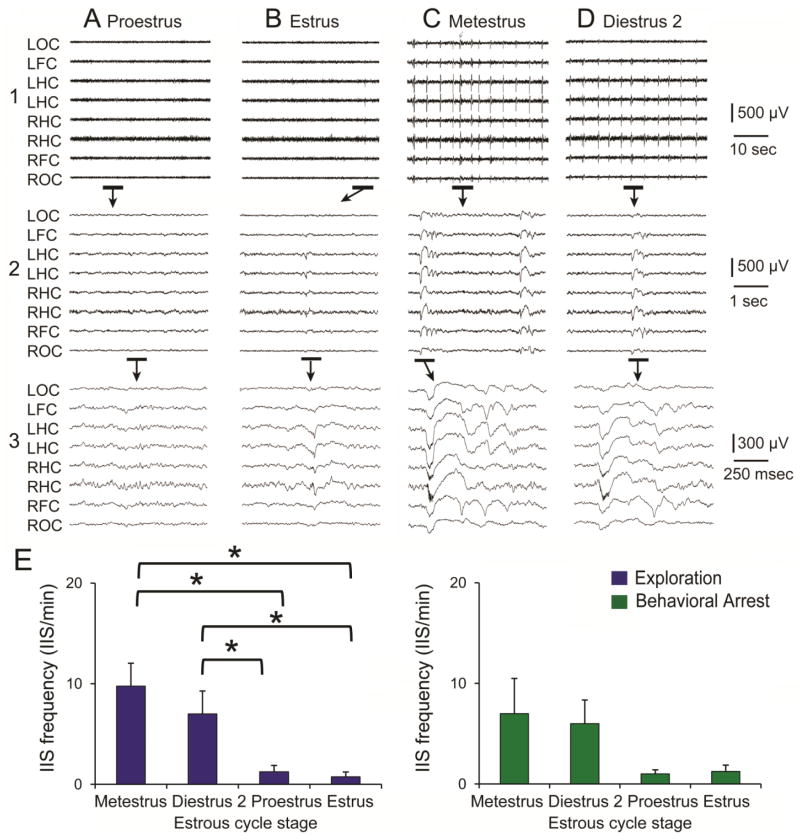

Figure 2. Example of a female rat after KA-induced SE with an increase in IIS frequency on metestrous and diestrous 2 mornings.

A. 1. A sample of the EEG during exploration on proestrous morning shows no IIS. LOC, left occipital cortex; LFC, left frontal cortex; LHC, left hippocampus; RHC, right hippocampus; RFC, right frontal cortex, ROC, right occipital cortex. 2–3. The EEG recordings marked by the bars are expanded as noted by the arrows.

B. The same animal, recorded one day later (on estrous morning). The expanded EEG shows a single, very small spike that was recorded primarily in hippocampal channels and is therefore likely to be a sharp wave.

C. One day later, metestrous morning, numerous spikes are present in the EEG. Expansion of the record in 2–3 shows the large size and duration of IIS that distinguished it from the spike in B3.

D. One day later, diestrous 2 morning, many IIS are also present. The expanded records in D2-3 show that the IIS are similar although smaller and less complex than the previous day, suggesting that IIS frequency as well as amplitude and complexity changed across the estrous cycle. In E, frequency is quantified rather than amplitude and complexity because the latter varies from channel to channel and animal to animal, with a large component of the variance due to electrode location.

E. Mean IIS frequency is plotted for 4 consecutive estrous cycles for exploration (blue bars) and behavioral arrest (green bars). A two-way ANOVA with cycle stage and behavioral state as factors showed a significant effect of cycle stage [F(3,32)4.953, p=0.0062] with no interactions of factors [F(3,32)0.384, p=0.7650]. Cycle stages were significantly different for exploration [one-way ANOVA, F(3,16)3.920, p=0.0284] but not behavioral arrest [F(3,16)1.525, p=0.2463]. For exploration, all pairwise comparisons were significant (Neuman-Keuls multiple range test, asterisks, p<0.05) except metestrus vs. diestrus 3, and proestrus vs. estrus.

IIS frequency follows a 4-day pattern in female epileptic rats

To examine the EEG after SE, electrodes were implanted 4 weeks later (Figure 1B1). Four weeks was chosen because this is a time when the vast majority of neuronal damage caused by SE has passed – typically most neuronal degeneration occurs in the first days after SE [35–37]. One-two weeks as after electrode implantation, animals were recorded daily (9–11 a.m.) to capture EEG activity at the same time of day. EEG was recorded during spontaneous behavior for a sufficient duration (1–3 hrs) that allowed us to sample each of the major behavioral states of the rat: exploration, behavioral arrest and sleep. Vaginal cytology was also examined to monitor estrous cycle stage and determine if cycles were regular.

In all animals that had regular estrous cycles after SE (n=8), there was a rhythmic pattern to the IIS that paralleled the estrous cycle. In Figure 2A–D, examples of recordings are shown for one of the rats; the EEG shows frequent IIS on metestrus and diestrus 2 in this animal. In contrast, IIS were rare on the proestrus and estrus. At higher resolution (Figure 2A3, 2B3, 2C3, 2D3), the IIS were not only most frequent on metestrous morning but also larger and more complex compared to other cycle daya (compare Figure 2C3 to 2B3; see also Supplemental Figures 3–4).

Figure 2E presents quantified data showing that the pattern of IIS exhibited in Figure 2 recurred during consecutive estrous cycles. Figure 2E also shows that that the pattern of IIS occurred during both exploration and behavioral arrest. However, statistical differences between cycle days were only present for exploration (Figure 2E).

In Figure 3, EEG recordings are shown for another rat - this rat also had regular estrous cycles after KA-induced SE, and the example is taken from about the same time after SE as the rat in Figure 2 (8 weeks). IIS frequency follows a 4-day pattern like the animal in Figure 2, but the stage when IIS frequency increased was between estrous morning and metestrous morning. In this animal there were consistent periods of sleep (unlike the animal with recordings shown in Figure 2) and the IIS during sleep showed a pattern similar to exploration and behavioral arrest, increasing on estrus and metestrus (Figures 3E). Thus, all three behavioral states showed a similar cyclical waxing and waning of IIS frequency.

Figure 3. Example of a female rat after KA-induced SE with an increase in IIS frequency on estrous and metestrous mornings.

A. 1. A sample of the EEG during exploration shows no IIS on proestrous morning. 2–3. The parts of the EEG records in A1 that are marked by the bars are expanded.

B. The same animal, recorded 24 hrs later (estrous morning) shows numerous IIS.

C–D. During metestrous and diestrous 2 mornings, IIS were not evident. Note that IIS sometimes occurred on metestrous morning in this animal, but did not occur during this example. The variance is evident in the relatively large standard error bar for metestrous morning (M) in E for exploration.

E. Mean IIS frequency is plotted for 4 consecutive estrous cycles. IIS recorded during exploration (blue bars), behavioral arrest (green), and sleep (gray) show a similar predisposition for estrous and metestrous mornings. A two-way ANOVA with cycle stage and behavioral state as factors showed a significant effect of cycle stage [F(3,36)16.669, p<0.001] with no interactions of factors [F(6,36)1.365, p=0.2550]. For exploration, there was a significant effect of cycle stage by one-way ANOVA [(F(3,12)20.673; p<0.0001)]. Cycle stage was also a significant factor for behavioral arrest [one-way ANOVA: (F(3,12)3.534, p=0.0484)] and sleep [one-way ANOVA: F(3,12)3.532, p=0.0485]. For all behavioral states, the pairwise comparison between diestrus 2 and estrus was significant (Neuman-Keuls multiple range test, p<0.05). For exploration, additional pairwise comparisons were also significant as indicated by the brackets and asterisks (all p<0.05). M= metestrous morning; D= diestrous 2 morning; P= proestrous morning; E= estrous morning.

Of the 8 animals that had regular estrous cycles, 3 rats showed the peak IIS frequency on estrous morning, 1 on either estrous or metestrous morning, 3 during metestrous or diestrous 2 morning and 1 on proestrous and estrous morning. One of the 3 that exhibited high IIS frequency on metestrous and diestrous 2 mornings was not recorded for more than 2 consecutive estrous cycles so it is excluded from the analysis described next.

In the other 8 animals, spontaneous convulsive seizures were frequent even though data were acquired before 6 months had passed after SE. We interpret this result as variability in the animal model. In these animals, both IIS frequency and estrous cycles were irregular.

Do variations in IIS frequency in female rats fit a cyclical wave pattern?

The relationship between the estrous cycle and IIS frequency suggested that IIS frequency changed in a cylical manner. To determine whether the changes in IIS frequency from day to day fit a pattern that conformed to the 4-day estrous cycle (defined by vaginal cytology), data were subjected to sinusoidal regression analysis, with the null hypothesis being that the daily variations in IIS frequency were random, and would preclude successful convergence of the regression model. The parameters in the curve fit equation were all allowed to vary independently during curve fitting: none were constrained, to force fitting to a pre-determined pattern.

Data were analyzed from 7 animals that were recorded daily for more than 2 consecutive regular 4 day-long estrous cycles (again, defined by vaginal cytology). Raw data and curve fits from 2 of these animals are shown in Figure 4A–B and the results of the regression analyses for all 7 animals are shown in Table 1. Figure 4B1 illustrates the data for IIS during exploration and behavioral arrest for 4 consecutive estrous cycles. In red is the sine wave regression line that would be predicted from these data. The regression coefficient (r=0.788; p=0.003) indicated that the data could not be explained simply as random daily variation. Figure 4B2 shows data from another animal where the regression coefficient (r=0.753) also indicated a significant fit to the cyclical model (p=0.004). For these and the other animals (Table 1) there was a mean periodicity (4.0–4.5 days long) similar to the 4 day estrous cycle. There were 3 cases out of 14 where the null hypothesis could not be rejected (Table 1). In these cases, there were relatively few days where there was spontaneous exploration or behavioral arrest, making it more difficult to conclude that there was a significant regression. Therefore, the lack of a statistically significant curve fit cannot necessarily be interpreted as a lack of IIS cyclicity in these animals: we simply did not have a long enough consecutive recording period in these cases.

Figure 4. In KA-treated female rats with regular estrous cycles fluctuations in IIS frequency are cyclic and similar in periodicity to the estrous cycle.

A. IIS frequency is plotted for consecutive estrous cycles with recordings during exploration (1) or behavioral arrest (2). These data were obtained from a single rat and are shown to exemplify variation in IIS frequency in relation to the estrous cycle. M= metestrous morning; D= diestrous 2 morning; P= proestrous morning; E= estrous morning.

B. Sine wave regression analyses for two different animals (one in B1, the other in B2) are shown. In each case, the raw data (IIS/min) for exploration (blue lines) and behavioral arrest (green lines) fit a sine wave pattern (red lines). The r and p values are listed in the upper left corners of each graph.

Table 1.

Characteristics of IIS frequency fluctuations in intact female rats after SE.

| Female # | # of Cycles Analyzed | Frequency (days) | Amplitude IIS/min | Regression Coefficient r | F | d.f | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Explor Beh Arr | 3 | n.s. 4.0 |

n.s. 7.72 |

0.561 0.739 |

2.06 5.41 |

2,9 2,9 |

0.183 0.029 |

| 2 Explor Beh. Arr | 4 | 4.5 4.5 |

9.86 8.38 |

0.803 0.700 |

11.76 6.24 |

2,13 2,13 |

0.001 0.013 |

| 3 Explor. Beh. Arr. | 9 | 4.0 4.0 |

7.90 13.20 |

0.634 0.412 |

8.07 3.41 |

2,24 2,32 |

0.002 0.045 |

| 4 Explor. Beh. Arr. | 3 | 4.0 4.0 |

12.41 14.86 |

0.835 0.861 |

8.04 12.88 |

2,7 2,9 |

0.015 0.002 |

| 5 Explor. Beh. Arr. | 8 | 4.0 4.0 |

11.00 13.40 |

0.542 0.577 |

6.01 7.24 |

2,29 2,29 |

0.007 0.003 |

| 6 Explor. Beh. Arr. | 3 | 4.0 n.s. |

5.75 n.s. |

0.864 0.681 |

10.31 3.45 |

2,7 2,8 |

0.008 0.083 |

| 7 Explor. Beh. Arr. | 5 | n.s. 4.0 |

n.s. 7.61 |

0.520 0.802 |

2.60 12.60 |

2,14 2,14 |

0.109 0.001 |

Modified sine wave regression analyses were performed as described in Methods on the interictal spike (IIS) frequency for the 7 intact female rats that showed at least 3 consecutive regular 4-day estrous cycles. Female # refers to number 1–7 for the 7 female rats. For each female, data are listed first for exploration (Explor.) and then the data are shown for behavioral arrest (Behav. Arr.) on the next line. # Cycles Analyzed refers to the number of consecutive estrous cycles that were analyzed. Frequency is listed only for those data with a significant correlation, and is the number of days of the period in the calculated sine wave pattern of IIS frequency. Amplitude is the mean wave amplitude derived from the regression analyses, and also is shown only for those data where there was a significant correlation. Regression coefficients (r), the corresponding ANOVA F ratios, degrees of freedom, and p values are presented in the four right hand columns, respectively. The results show that where a significant correlation was observed, the calculated sine wave pattern of IIS frequency had a period of 4–4.5 days (column 3), while the mean wave amplitude (column 4) ranged from 5.75–14.86 IIS/min. For all 11 of the 14 regression analyses, statistically significant sinusoidal wave patterns were observed. N.s.= not significant.

Cyclic changes in IIS frequency are related to the estrous cycle

In 4 animals, the regular 4-day pattern of estrous cyclicity transiently stopped during the first 6 months after SE. During this period of acyclicity in vaginal cytology, there was no clear cycle in IIS frequency (Figure 5). When the vaginal cytology had resumed a 4 day pattern, typically after a week, the cyclic pattern of IIS became robust (Figure 5). These data suggest that the cyclic IIS pattern is remarkably consistent, as long as the estrous cycle is maintained, but this consistency is lost when vaginal cytologic patterns become irregular.

Figure 5. Acyclicity reduces the cyclic pattern of IIS frequency after KA-induced SE.

A. IIS frequency is plotted for an animal that had a spontaneous period where there was acyclicity according to the vaginal cytologic data (dotted line). Prior to the acyclicity, IIS frequency increased on proestrous (P) and estrous (E) mornings. During the time when vaginal cycles were acyclic, IIS became acyclic. An arrow points to the first day when IIS frequency did not follow the pattern of increasing in frequency on proestrous or estrous morning. This day occurred prior to the onset of vaginal acyclicity (i.e., defined by vaginal cytology), presumably because the turnover of cells in the vaginal epithelium is 24–36 hrs slower than the changes in the brain. Metestrus, M; diestrus 2, D.

B. Data from the same animal during behavioral arrest. During the period of vaginal acyclicity, IIS frequency decreased (the period of acyclicity corresponds to the dotted line on the X axis). Thus, acyclicity disrupted the cyclic IIS fluctuations and led to a dissociation between IIS in exploration (increasing during acyclicity) and behavioral arrest (decreasing).

C.1. The data for behavioral arrest in B are plotted after sine wave regression analysis to show that the sinusoidal pattern that occurred when the animal had regular vaginal cycles was decreased during acyclicity. In C1 and C2, the acyclic period is indicated by a dotted line. 2. Data from another rat showing a dramatic reduction in IIS when there was acyclicity. The recordings were made during behavioral arrest.

Notably, IIS still occurred when the 4-day vaginal cytology pattern was briefly disrupted (Figure 5C1). However, the periodicity was unclear (Figure 5C1) or completely blocked (Figure 5C2). These data are consistent with the idea that the estrous cycle entrains the EEG, but in the absence of regular ovarian cycles, other rhythms have the potential to affect IIS frequency.

Interestingly, IIS frequency in Figure 5A–B became irregular 1 or more days before the change in the vaginal cytology. One might interpret this result as an indication that IIS actually influence vaginal cytology rather than the opposite, that vaginal cytology affects IIS. However, that interpretation might not be true, because changes in the vaginal epithelium during the estrous cycle occur as a response to hormonal changes that occurred 24–36 hrs earlier. Thus, a rise in estradiol levels on proestrous morning may normally lead to effects on IIS as well as the vaginal epithelium at the same time, but effects on the IIS might be observed sooner than effects on the vaginal epithelium.

Convulsive seizures in female rats

In the female rats with cyclic increases in IIS frequency, convulsive seizures were not observed during the recording session. Therefore, spontaneous seizures did not appear to cause the fluctuations in IIS frequency that were observed. However, seizures could have occurred at other times. Therefore, 2 animals that had regular estrous cycles and showed cyclic fluctuations in IIS frequency were video-monitored when they were not being recorded. In other words, from the end of one morning session to the beginning of the next recording session the next day. We asked whether there were any convulsive seizures during this time, and if they occurred immediately before or after an increase in IIS frequency.

Two spontaneous convulsive seizures were detected in 8 consecutive days for 1 of the animals. In this case, a stage 5 convulsive seizure was observed at 6:36 a.m. on proestrous morning and 6:18 a.m. on metestrous morning (approximately 48 hrs later). IIS frequency rose on estrous morning, about 28 hrs after the first convulsive seizure and about 20 hrs before the next convulsive seizure. The long intervals between convulsive seizures and IIS frequency fluctuations suggest the two were unrelated.

In the second animal the video showed that no convulsive seizures occurred during 8 consecutive 24 hr periods of recordings (video-EEG recordings plus video-monitoring). Therefore, convulsive seizures did not appear to cause the cyclic changes in IIS.

To further address the possibility that spontaneous seizures caused periodic increases in IIS frequency, the spontaneous seizures that occurred >4 months after SE were analyzed. At this time, animals were recorded daily, spontaneous convulsive seizures (Supplemental Figure 5) were frequently observed, and the estrous cycle was irregular. When a convulsive seizure was observed before a recording session (5–10 min before; n=4 rats), robust IIS were only present in 1 of the recording sessions. When convulsive seizures occurred in the 5–60 min after a recording session (n=6 rats), IIS frequency was low (<2/minute) in all but 2 of the recording sessions. Therefore, there was no clear relationship between convulsive seizures and IIS frequency.

In 4 rats, a spontaneous convulsive seizure occurred during a recording session. As shown in Supplemental Figure 5, IIS did not occur in the EEG record in the minutes prior to or after the convulsive seizure. These data support the suggestion that convulsive seizures did not cause the observed changes in IIS frequency. These data are also consistent with weak evidence in the clinical epilepsy literature that IIS are related to seizures, although there are suggestions that an increase in IIS may occur after seizures [38,39]. In epileptic animals, it has been reported that IIS increase during epileptogenesis, prior to the first seizure [40] but the relationship of chronic seizures (after epileptogenesis) to IIS is unclear [41].

Determining the role of the estrous cycle on IIS

Ovx rats were used to determine whether blocking the estrous cycle stopped 4-day patterns in IIS frequency (Figure 1D2). There was no detectable 4-day IIS pattern after Ovx (Figure 6A–B). All of these female rats had cyclic IIS before Ovx. The effect of Ovx on IIS amplitude was variable, in that some animals had IIS that dropped to 0 after Ovx (n=2), whereas in other animals IIS still occurred but the spikes were smaller in amplitude (Figure 6A–B).

Figure 6. Ovx reduces the cyclic pattern of IIS frequency after KA-induced SE.

A–B. 1. IIS are shown for a day when IIS were robust before (A, Pre-Ovx) and 7 days after (B, Post) Ovx. 2. Parts of the EEG recordings in A1 that are marked by a bar are expanded. 3. Parts of the EEG recordings in A2 that are marked by a bar are expanded.

C. Mean IIS frequency is plotted for 12 consecutive days. The first 4 days were numbered 1–4, the next 4 days as 1–4, and the last 4 days as 1–4. Days were assigned a number to test the hypothesis that a 4-day sequence was present. All days assigned 1 were then averaged, those days numbered 2 were averaged, and means for days 3 and 4 were also calculated. Two-way ANOVA, with the day (i.e., 1,2,3, or 4) or behavioral state as factors showed no influence of day [F(3,56)1.396, p=0.2535] but there was a difference in behavioral state [F(2,56) 5.076, p=0.0094], consistent with a dissociation of IIS frequency for exploration and behavioral arrest after Ovx. Thus, there were relatively high IIS frequencies during exploration in Ovx rats but relatively low frequencies during behavioral arrest. IIS were particularly infrequent during sleep. There was no interaction of factors [F(6, 56) 0.699, p=0.6511].

To ask if a 4-day pattern was present after Ovx, the first 4 days of the recording period were assigned numbers 1–4 consecutively, as if they were days of the estrous cycle. In the next 4-day period and the third 4-day period the same numbers (1–4) were assigned to the four days (Figure 6C). When the means for each day of the three 4-day periods were averaged, the results showed that mean IIS frequency for days 1, 2, 3 and 4 were not statistically different (Figure 6C). These data suggested that there was no detectable 4-day pattern of IIS after Ovx.

Ovx also had other effects on IIS. After Ovx, IIS in exploration and behavioral arrest were very different, with increased IIS during exploration and rare IIS in behavioral arrest (Supplemental Figure 6). A similar dissociation was observed in acyclic animals (Figure 5). In contrast, intact cycling rats showed IIS patterns that were similar between behavioral states.

As an alternative approach to Ovx, a nuclear estrogen receptor (ER) antagonist (ICI 182,780) was used to block the effects of estradiol during its preovulatory surge. The rationale for this approach was to prevent the subsequent surge in luteinizing hormone (LH) and ovulation that evening. Using this approach, we could reversibly block the estrous cycle. In these experiments (n=3 rats), vehicle was tested first, and then ICI 182,780 was tested one cycle later (Figure 1D4). Two injections were made, timed for diestrous 2 morning and early on the morning of proestrus respectively. The reason for these two times was that the rise in serum estradiol during this time triggers the later surge in LH and ovulation. Specifically, injections were administered on diestrous 2 morning (8:30–9:00 a.m.) and proestrous morning (8:30–9:00 a.m.); ovulation normally would occur on the evening of proestrus, approximately 12 hrs after the proestrous morning injection (31). A dose of ICI 182,780 was used that previous studies showed was effective in antagonizing nuclear ERs (1 mg/kg; [42,43]).

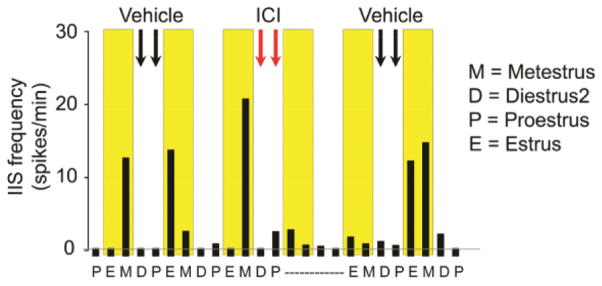

As shown in the example in Figure 10, vehicle had no detectable effect, because the animal continued to show regular estrous cycles and a cyclic increase in IIS - in this animal the cyclic increase in IIS frequency occurred on estrous or metestrous morning. After ICI administration in this animal, there was no evidence of an estrous cycle by vaginal cytology, and no increase in IIS on estrous or metestrous morning (Figure 7). When the cycle of the vaginal epithelium returned, IIS frequency began to cycle again (Figure 7). These data suggest that cyclic IIS depend on the estrous cycle. They also suggest that IIS can be blocked by transient suppression of nuclear ERs.

Figure 10. KA-induced SE on diestrus led to the least neuronal damage in female rats.

A. Sections from 3 animals that were perfused 3 days after KA-induced SE were stained using an antibody to NeuN. Extensive NeuN loss was evident in the male (top, arrows), female that had SE on proestrous morning (center), but not the female that had SE on metestrous morning (bottom). Calibrations for A and B are the same.

1. Hippocampal subfields showing a loss of NeuN are marked by arrows and include the hilus (HIL), CA3, CA1, and the subiculum (Sub).

2. Areas showing loss of NeuN in the entorhinal cortex (EC) were located in the medial and lateral divisions (MEC, LEC). Pre, presubiculum; para, parasubiculum.

3. Quantification of NeuN loss. Each circle represents data from a different animal, which were injected with KA at different cycle stages or were males. Left: The area fraction of NeuN loss showed sparing of the granule cell layer (GCL, close to 0 %). There was NeuN loss in the CA1–CA3 cell layer (CA1–CA3), hilus (HIL) and subiculum (SUB) for all animals. Yellow, SE on metestrus or diestrus 2 morning (n=4); Red, SE on proestrous or estrous morning (n=3); Black, males (n=7). Right: The area fraction (%) is plotted for the pre and parasubiculum (Pre + Para), all layers of the MEC, and just layer III of the MEC. Note layer III of the MEC exhibited the most NeuN loss of all animals, which has been shown for male rats that have SE [50]

B. Adjacent sections to those in A were stained for fluorojade B. The areas corresponding to NeuN loss in A showed positive staining with fluorojade B in most cases, but there were exceptions. For the hilus and entorhinal cortex, females that had SE during diestrus showed weak fluorojade B staining. In these cases, there was damage to neurons (pkynosis using cresyl violet staining) but not death (loss of cells by cresyl violet staining), consistent with a loss of NeuN in response to injury (36).

B. Fluorojade staining in the same animals as A1-2.

1. Hippocampus.

2. Entorhinal cortex.

3. The area surrounded by the box in (2) is expanded to show the fluorojade B-positive cells in the deep and superficial layers of the EC. LD, lamina dissecans. Note that there is extensive fluorojade B staining except for the female that had SE on metestrous morning where fluorojade B cells were evident but only in the most medial part of the EC (arrows).

4. Quantification of fluorojade B-stained cells. Females had similar staining as males except for the females that had SE during diestrus. Because females that had SE during diestrus were the animals which maintained estrous cycles and exhibited cyclic IIS, the data suggest that only those animals without extensive neuronal loss had preservation of their estrous cycles and developed cyclic IIS.

Figure 7. Pharmacological cessation of the estrous cycle reduces cyclic IIS.

IIS frequency during exploration is shown for consecutive days of a rat that had KA-induced SE approximately 3 months earlier. IIS frequency increased on estrous and metestrous mornings in this animal, highlighted in yellow. Two vehicle (black arrows) or two ICI 182,780 (red arrows) injections were made in the early morning of diestrous 2 and proestrous. The injections of ICI were intended to block nuclear estrogen receptors and therefore the actions of estrogen that are critical to ovulation late on proestrous day. Vaginal cytology showed that the estrous cycle had an abnormal pattern on the days after the injection of ICI 182,780 (indicated by a dotted line) but the effect was not detected after vehicle treatment. IIS frequency was low during the period of vaginal acyclicity. Afterwards the estrous cycle resumed and there was a return of the pattern in IIS frequency to the one that was observed before injection of ICI, an increase in IIS frequency during estrous and metestrous mornings.

Similar analyses of IIS frequency were also performed in males (Figures 1D3 and 8; n=4). Eight weeks after SE, there usually were IIS each day (Figure 8). IIS in males exhibited IIS frequencies like females, ranging from as low as 2–3/min and not exceeding 30/min. To ask if a 4-day pattern was present, a similar approach was taken as the one used for Ovx rats. The first 4 days of the recording period were assigned numbers 1–4 consecutively, and the same was done for the next 4-day period and the third 4-day period. Comparing the means for the three 4-day periods showed that mean IIS frequency for days 1, 2, 3 and 4 were not statistically different (Figure 8). Therefore, over a 10–12 day period of recordings, a 4-day pattern was not evident. The irregular frequencies of IIS from day to day in males suggests that a 4-day pattern to IIS frequency is specific to females. In addition, the results indirectly support the idea that there is an estrous cycle dependence of the 4-day pattern in IIS.

Figure 8. Males lack a 4-day IIS frequency pattern after KA-induced SE.

A–D. 1. EEG of a male, 8 weeks after KA-induced SE. Data from 4 consecutive mornings are shown. During these recordings, animals were exploring. IIS occurred each day. 2. Areas of the EEG recordings that are marked by the bars in A–D are expanded.

E. 1–2. Quantification of IIS frequency as in Figure 6, i.e., the first 4 days assigned the numbers 1–4, the next 4 days also assigned numbers 1–4, etc. The means for all of the days assigned 1, 2, 3, or 4 were then compared by two-way ANOVA with day and behavioral state as factors. There was no influence of day [F(3,26)0.794, p=0.5081] or behavioral state [F(1,26)0.063, p=0.8038].

Pilocarpine-treated rats

Although the incidence of pilocarpine-induced SE in females was low, 5 females had SE and maintained regular estrous cycles for up to 2 months after SE. Three of these animals were implanted with chronic electrodes 4 weeks after SE (Figure 1D1) and were compared to 5 others that had pilocarpine, but did not develop SE. As shown in Figure 9, the 3 females that had SE and maintained regular estrous cycles developed cyclic IIS. Animals increased IIS frequency on proestrous or estrous morning (Figure 9). In the 5 females that did not have SE, IIS were extremely rare.

Figure 9. Cyclic IIS occur in female rats after pilocarpine-induced SE, like KA-induced SE.

A–D. 1. An example of a pilocarpine-treated rat that had SE, regular estrous cycles, and cyclic IIS. 2. The parts of the EEG recordings in A–D that are marked by bars are expanded. Note that there are sharp waves in hippocampus but these are not accompanied by spikes in frontal cortex or occipital cortex, which distinguishes sharp waves from IIS.

E. Mean IIS frequencies for 4 consecutive estrous cycles are plotted for exploration, behavioral arrest and sleep. Two-way ANOVA showed that there was an effect of cycle stage [F(3,36)7.770, p=0.004] and behavioral state [F(2,36)3.264, p=0.0498) and no interaction of factors [F(6,36) 0.451, p=0.8392). For exploration, one-way ANOVA followed by pairwise comparisons showed significant differences between all cycle stages except metestrus and diestrus, as indicated by the asterisks (Neuman-Keuls multiple range tests, all p<0.05). There were no significant differences between cycle stages for behavioral arrest and sleep.

Neuropathology

The results showed that 8 of the 16 females that had KA-induced SE had rare convulsive seizures and exhibited cyclic IIS and 4-day estrous cycles. The other 8 animals developed frequent convulsive seizures and had irregular IIS with irregular estrous cycles. We hypothesized that the females with more neuronal damage had the frequent convulsive seizures, and as a result, irregular estrous cycles. To test that hypothesis we evaluated an additional cohort of 7 females and 7 males after KA-induced SE, perfusion-fixed 3 days later (Figure 1D5), because the majority of neuronal loss after SE occurs in the days after SE [35,37]. To evaluate neuronal damage, NeuN immunohistochemistry and fluorojade B histochemistry were conducted. Cresyl violet staining was also performed to confirm that reduced NeuN immunoreactivity corresponded to areas of neuronal loss (data not shown). This confirmation is important because weak NeuN immunoreactivity can occur when neurons are damaged, but not dead [44,45]. The weak immunoreactivity can make it appear that neurons are lost, but cresyl violet staining shows they are present [44,45]. In this case, cellular or oxidative stress to neurons causes phosphorylation of NeuN and the antibody does not recognize the phosphorylated antigen [see discussion in [44,45]].

As shown in Figure 10, males and some females showed a pattern of neuronal damage in hippocampus that is consistent with prior studies using KA-induced SE. This pattern of damage is analogous to human TLE with mesial temporal lobe sclerosis where there is neuronal loss in the hilus, CA1 and CA3, with sparing of the dentate gyrus [46,47]. This pattern of damage is accompanied by a loss of neurons in the entorhinal cortex [48,49]. In rats, similar areas are affected [50–53].

Four females appeared to have much less NeuN loss and much less fluorojade B staining (Figure 10; Supplemental Figures 7–8). In CA1 and CA3, very little cell loss was evident. In the hilus, NeuN loss was evident, but this was not accompanied by fluorojade B staining, suggesting hilar injury but not cell loss. Cresyl violet staining confirmed that cell loss did not occur (data not shown). Like the hilus, NeuN loss was evident in entorhinal cortex, but few cells were fluorojade-B positive (Figure 10; Supplemental Figures 7–8). These 4 females had SE on diestrous morning (either metestrus or diestrus 2; Figure 10). In contrast, the 3 females that had SE on estrous or proestrous mornings were the ones that developed extensive neuronal loss, like males (Figure 10).

Data from an alternate method to judge fluorojade B staining, where each positive profile was counted as an object by computerized thresholding (see Methods) led to similar findings. Thus, for the entorhinal cortex, diestrous females had a significantly lower number of fluorojade B-positive cells compared to males (diestrous females: 190.0 ± 78.6 n=4; males: 446.8 ± 15.3, n=5; Student s t-test, p=0.0438). Fluorojade-positive cells in rats that had SE on proestrous (532 cells) and estrous (558 cells) mornings were comparatively high (Figure 10).

These data support the hypothesis that when SE occurs on diestrus, there is less neuronal damage, convulsive seizures are rare in the first 4 months after SE, and regularity of estrous cycles is preserved. In contrast, animals with more neuronal damage had earlier emergence of severe (convulsive seizures) and estrous cycles were irregular. The results suggest that future studies of the relationship between reproductive function and epilepsy in females can be more readily studied if SE is induced during diestrus.

DISCUSSION

Summary

This study showed that a characteristic feature of the EEG in epilepsy, IIS, waxes and wanes during the estrous cycle of female rats after KA- or pilocarpine-induced SE. This is the first description of a cyclic pattern to the EEG in female rats in models of epilepsy. We found that the EEG fluctuations were primarily evident in IIS frequency. Increased IIS complexity and amplitude often occurred when IIS frequency increased also.

The fluctuations in IIS frequency appeared to be caused by the estrous cycle, because IIS lacked a 4-day pattern when the estrous cycle was transiently irregular. In addition, IIS fluctuations no longer followed a 4-day pattern after Ovx. A similar reduction in the IIS 4-day pattern was observed following antagonism of ER, which stopped the estrous cycle. As one would predict if estrous cycles caused an IIS periodicity, males did not show a pattern to their IIS. After female rats developed severe seizures, estrous cycles were disrupted and IIS patterns were lost. Together these data suggest that there is a striking influence of the estrous cycle on IIS frequency in the female rat after SE.

IIS followed a 4-day pattern after SE in female rats with 4-day estrous cycles

The most striking finding in this study is the association of IIS frequency with the 4-day estrous cycle. This association occurred in all female rats with regular estrous cycles, and none of the female rats without regular estrous cycles. It was found after KA-induced SE or pilocarpine-induced SE. It appeared that IIS waxed and waned in parallel to the estrous cycle independent of behavioral state, i.e., exploration, behavioral arrest and sleep were similar. However, animals did not always have spontaneous periods of sleep, so conclusions about sleep should be made with caution.

These data support the general view that there are substantial changes in neuronal excitability during the estrous cycle [30,54–58]. Generally it has been assumed that one cause of increased excitability, when it occurs during the time when estradiol levels are rising in the serum, is estradiol [59–62]. By numerous mechanisms estradiol increases responses to afferent stimuli, contributes to long-term potentiation, and reduces hyperpolarizing actions of potassium channels [62–66]. In the rat, these mechanisms can explain increased neuronal excitability on proestrous morning, at the end of the preovulatory surge in estradiol. On the other hand, estradiol also has actions that support GABAergic inhibition, such as increasing the levels of the synthetic enzyme responsible for GABA synthesis [67–70]. Therefore, an increase in excitability in response to estradiol and on proestrous morning is not always observed [30].

It is also thought that excitability increases at the time of the estrous cycle when progesterone levels decline, which is early on estrous morning in the rodent [29]. Here the mechanisms that have been suggested primarily are related to allopregnanolone, the metabolite of progesterone that enhances effects of GABAA receptors. As progesterone declines, levels of allopregnanolone do also, reducing inhibition by GABAA receptors. In addition, the decline in progesterone leads to an alteration in the subunits of GABAA receptors, leading to an alteration in inhibition that causes increased excitability [71].

Notably, measures of excitability have not been tested very often in the female rat as it passes through the phases of the estrous cycle in vivo. Most studies have examined different cohorts of rats, and comparisons of proestrous morning, estrous morning and diestrus are rare. Instead, many studies examine the effects of estradiol and progesterone, either in intact or Ovx rats. Studies of seizure susceptibility also have not compared proestrous morning, estrous morning and diestrus. Still, from the data that are available, one would expect that effects of estradiol on proestrous morning would not have as great an effect to increase excitability as the decline of progesterone just before estrous morning. The reason is that estradiol is not always robust in its pro-excitatory effects as mentioned above; in contrast, declining levels of progesterone consistently increase neuronal excitability [71]. Consistent with these findings, the most robust rise in IIS was not on proestrous morning but estrous morning.

IIS also rose on metestrous morning in some animals, which we explain by effects of SE. In brief, SE causes a decrease in normal inhibitory mechanisms that usually occur during diestrus. One normal inhibitory mechanism is related to delta subunits of the GABAA receptor. The delta subunit of the GABAA receptor subunit normally is expressed more during diestrus in the hippocampus of female mice than other stages of the estrous cycle, and delta subunits normally play a role in decreasing seizure susceptibility [54,55,72]. After KA-induced SE, delta subunits are downregulated in hippocampal principal cells and remain at low levels for weeks or months [73]. Therefore, reduced delta-containing GABAA receptors in female rats after SE could explain increased IIS frequency during diestrus. Notably, downregulation of delta subunits in principal cells of the dentate gyrus is accompanied by upregulation of delta subunits in GABAergic interneurons [74] supporting the idea that the local GABAergic neurons are particularly important.

Another normal inhibitory mechanism during diestrus, also compromised by SE, is related to neuropeptide Y (NPY). NPY is normally expressed in a subset of GABAergic neurons in both hippocampal and cortical networks, and most effects of NPY are inhibitory [75]. NPY immunoreactivity peaks in hippocampus during diestrus in the Sprague-Dawley rat [76] presumably an effect caused by the proestrous rise in serum levels of estrogens because estrogens increase NPY expression in the rat [77,78]. Importantly, NPY is anticonvulsant [77–79] and after SE, NPY-expressing neurons are decreased in number and NPY receptors and expression is altered [80,81]. Therefore, normal inhibitory effects of NPY during diestrus may be decreased after SE and lead to a cyclic increase excitability on diestrus which promote IIS.

It is important to note that we assume that IIS frequency rises because of increased excitability. However, from one perspective IIS are inhibitory – because when IIS are frequent they appear to inhibit seizures. The mechanism of inhibition of seizures is thought to be analogous to a stimulus which aborts a subsequent response to the same stimulus by placing neurons in a refractory or inhibited state. The first stimulus may involve transient depolarization and action potential generation of neurons, but causes an inhibited state so that the second stimulus has a small effect. In the case of seizures, IIS appears to place neurons in a state where a seizure is unlikely to be generated, at least in some studies [41,82,83]. Whether this inhibited state is due to ion channels or GABAergic mechanisms or other factors (e.g., glial) is not clear. For this reason, we interpret IIS in our rats to be transient excitatory events, but do not make conclusions about their potential inhibitory effects on seizures.

Cyclic changes in IIS frequency depend on the estrous cycle

The results suggest that cyclic IIS depend on the estrous cycle. Several experimental approaches support this conclusion, summarized above. This conclusion leads one to question how the estrous cycle influences IIS. If we assume that IIS can be caused by transient synchronous excitation of neurons in the forebrain, one would assume that the causes of IIS would be related to pathways that can synchronously influence neurons throughout the forebrain. There are several pathways that are good candidates to cause IIS because they project diffusely to many regions of the forebrain and therefore could synchronize many neuronal populations at one time. Ascending cholinergic and aminergic systems are attractive candidate pathways because concentrations of neurotransmitters (e.g. acetylcholine) change with the estrous cycle; however, effects vary among regions that have been examined, and are complex [84–86].

Besides pathways that extend for long distances, local GABAergic neurons are also important to consider because they regulate synchronization of principal neurons and are influenced by gonadal hormones. Moreover, blocking GABAA receptors has been used to produce IIS-like events in hippocampal slices [87–90]. IIS recordings from hippocampus in vivo have recently been shown to involve GABAergic neurons [91]. Although estrous cycle modulation of IIS has not been studied per se, there are numerous ways that 17β-estradiol [59,92–95], and the progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone [71,74,96–98] could modulate GABAergic inhibition (described above). There are also estrous cycle-dependent changes in glia and vascular factors, some of which are triggered by estrogens [99–101] and progesterone [102,103]. Changes in local GABAergic neurons within forebrain circuits that occur in response to the estrous cycle could interact with changes occurring in ascending brainstem projections to produce IIS; a similar suggestion of interacting intrinsic and subcortical changes that lead to hippocampal disinhibition has already been made for males after lesions of the fimbria-fornix [104].

Neuropathology

Examination of neuropathology in the female and male rats 3 days after SE showed variable degrees of neuronal damage in hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, with the least in diestrous females – that is, when SE was induced on metestrous or diestrous 2 morning. These data are consistent with the view that metestrous and diestrous 2 mornings are times of the estrous cycle when – in normal rats - excitability in hippocampus is low. Reduced excitability is likely to cause reduced excitotoxicity during SE.

Low excitability during diestrus is generally attributed to the relatively low levels of gonadal steroids at this time, and the fact that fluctuations are small. As mentioned above, delta subunits of the GABAA receptor and increased levels of NPY may contribute to low excitability in the normal female rat. Direct assessment of excitability in the different cycle stages in areas such as hippocampus and entorhinal cortex of normal adult female rats have also been made and support this view. Thus, in area CA1 and CA3, the evoked responses to the major afferent inputs were greater on proestrous morning and estrous mornings than diestrous 1 morning in adult female Sprague-Dawley rats [30,105].

The results also show that males were similar to proestrous and estrous females in their degree of neuronal hippocampal and entorhinal cortical damage 3 days after SE. The similarity is surprising for several reasons. First, estrogen is considered to be protective and serum levels of estrogen are high on proestrous morning relative to estrous morning and males. However, estrogen has diverse effects and may not always be protective (as described above). Furthermore, serum levels of estradiol may be less germane to hippocampal damage than hippocampal levels of estradiol. In support of that idea, ER occupancy in the proestrous female brain varies within a range that is similar to the male [106].

The pattern of neuronal damage in the female rat after SE on diestrus showed that there was little evidence of neuronal loss in hippocampus, but other brain areas were adversely affected. These extrahippocampal areas were those that have been shown before to be highly vulnerable to excitotoxicity and SE-induced neuronal loss, such as the entorhinal cortex [50,107]. These data suggest that when SE is decreased in severity, the hippocampus is an area that is protected. However, there is still neuronal loss elsewhere, in extrahippocampal areas. The minimization of neuronal damage may be why the diestrous females were most likely to have regular estrous cycles after SE. In the future, the diestrous stage of the cycle will be useful to further examine the interaction of the estrous cycle and sequelae that follow SE.

KA-induced SE in diestrous female rats to study the epilepsy in cycling female rats

This study provides a method to study the relationship between the ovarian cycle and seizures in rats, particularly diestrous rats as stated in the previous paragraph. Animal models have been used before, but many of these models used Ovx rats. Using intact rats has been difficulty because estrous cycles are usually irregular when severe convulsive seizures develop in female rats [108]. In addition, these rats develop ovarian cysts and elevated androgen levels [18], which contribute to the acyclicity. Despite the fact that ovarian cysts and high androgen levels occur in women with epilepsy and are a clinical issue, and therefore merit analysis, they make it difficult to examine the way that seizures vary with the stage of the estrous cycle.

In the present study, we demonstrated a lack of pilocarpine-induced SE in females that was not evident with KA, which presumably results from an interaction of estrogen with the cholinergic system. It has been known for some time that estrogens inhibit effects of pilocarpine to stimulate drinking [109]. In hippocampus, 17β-estradiol treatment of Ovx rats reduces levels of hippocampal muscarinic receptors [110]. Ovx followed by estradiol replacement also reduces effects of muscarinic receptor activation in hippocampus [111,112]. In rat cortex, muscarinic receptors and affinity decrease in response to estrogens [113]. Thus, suppression of muscarinic receptors is likely to be responsible for the low incidence of pilocarpine-induced SE in females, and serves as a warning to investigators who pool sexes in epilepsy research.