Abstract

The current study examined school-level victimization as a moderator of associations between peer victimization and changes in two types of self-blaming attributions (characterological and behavioral) across the first year in middle school. These associations were tested in a large sample (N=5,991) of ethnically diverse adolescents from Fall to Spring of the sixth grade year across 26 schools. Consistent with hypotheses, the results of multilevel modeling indicate that victimized youth showed greater increases in characterological self-blaming attributions (e.g., ‘my fault and cannot change it’) in schools where victimization was less common. In contrast, victimization was associated with increases in behavioral self-blame (e.g., ‘I should have been more careful’) for bullied students in schools with relatively higher levels of victimization. Underscoring the psychological consequences of person-context mismatch, the results suggest that when schools manage to decrease bullying, the few who remain victimized need additional support to prevent more maladaptive forms of self-blame.

Keywords: peer victimization, characterological self-blame, behavioral self-blame, person-context fit, adolescence

Although it is well established that victims of bullying experience distress, recent findings indicate that their emotional pain varies across school contexts (Bellmore, Witkow, Graham, & Juvonen, 2004; Huitsing, Veenstra, Sainio, & Salmivalli, 2012). When victimization is less common in classrooms or schools, bullied youth show higher levels of anxiety and depression and are more disliked by peers, compared to youth who are bullied in classrooms with higher overall levels of victimization (Bellmore et al., 2004; Huitsing et al., 2012; Sentse, Scholte, Salmivalli, & Voeten, 2007). Such findings are disconcerting because typical antibullying efforts aim to decrease the overall levels of bullying and victimization in schools (see Ttofi & Farrington, 2011 for meta-analysis), which may, ironically, worsen the plight of those who remain victimized. To understand such potentially paradoxical effects of a person-environment mismatch (Wright, Giammarino, & Parad, 1986), the goal of the current study was to examine underlying attributional processes of victims and how such attributions are shaped by the school victimization context. This is a novel approach insofar as it considers how social cognitions are influenced by both individual differences in peer experiences (i.e., victimization) and school-level characteristics.

Causal attributions provide insight into why victimization is related to emotional pain. The assumption of attribution theory is that when individuals confront a negative experience, they try to understand why it happened, and their subjective interpretations in turn account for their emotional reactions (Weiner, 1985). For example, we know that victims of bullying endorse self-blaming attributions, which puts them at increased risk for internalizing distress (Graham & Juvonen, 1998; Prinstein, Cheah, & Guyer, 2005). However, there are important distinctions between specific types of self-blaming attributions that differentially relate to adjustment. In particular, characterological self-blame, perceptions that negative experiences are attributable to internal, stable, and uncontrollable causes (e.g., ‘something about who I am and cannot change it’), can be contrasted with behavioral self-blame, perceptions that such experiences are due to unstable and controllable causes. Characterological self-blame has been associated with low self-worth and depressive symptoms (Graham & Juvonen, 1998), as well as risk for future victimization (Schacter, White, Chang, & Juvonen, 2014). In the original research distinguishing different types of self-blaming attributions, Janoff-Bulman (1976) showed that compared to characterological self-blame, behavioral self-blame is less maladaptive, inasmuch as it captures the idea that “things won't always be like this and I can change” (see also Graham & Juvonen, 1998). Although behavioral self-blaming attributions are internal, they are more controllable and temporally unstable, implying there is something one can do to avoid being bullied, for example.

With few exceptions (e.g., Graham et al., 2009), attributions are typically examined in a social vacuum; that is, the social context and its potential impact on attributions are not taken into account. Yet, for early adolescents, the psychological meaning of being pushed around or made fun of should vary depending on how typical such experiences are in any one school. When hardly anyone is ridiculed, those who are may feel very targeted and more easily conclude that it is something about them personally causing the peer mistreatment. In contrast, when there are others also being bullied, it would be easier to determine that one's behavior put him/her at risk (e.g., “I was in the wrong place at the wrong time”). Although young children may not be able to tune into how common some social experiences are among classmates, by early adolescence social comparisons become increasingly salient (Eccles & Midgley, 1989; Ruble et al., 2004), especially in new settings (Simmons & Blyth, 1987).

The current study was designed to examine the effects of school-level victimization on self-blaming attributions across the first year in middle school. Transitioning to a new school is stressful in itself, and peer victimization experiences during the first year may be especially powerful in shaping adolescents’ expectancies about future social interactions and school enjoyment. Therefore, examining attributions of these early negative experiences is particularly meaningful. Relying on data from the Fall and Spring of sixth grade, we tested whether grade-level victimization (referred to herein as ‘school-level victimization’) moderates the association between personal (i.e., student-level) victimization and changes in the two types of self-blaming attributions across the school year. Finally, although there are known gender and ethnic differences in mental health outcomes (e.g., depression), little is known about gender or ethnic differences in self-blame. Therefore, we control for these demographic factors in the current analyses and consider their effects on characterological and behavioral self-blame.

We hypothesized that being in schools with lower levels of victimization would strengthen victims’ sense that “it's me and I cannot do anything about it” (i.e., characterological self-blame). In contrast, we expected that when peer victimization is not rare, bullied youth would be increasingly likely to attribute their experience to their behaviors (e.g., “being in the wrong place at the wrong time”). The proposed moderator effects of school context were tested by modeling cross-level interactions between self-perceived victimization and school-level victimization (self-perceived victimization aggregated by participant school) as predictors of characterological and behavioral self-blame in the Spring of students’ first year in the new school. These analyses were conservative inasmuch as we controlled for baseline levels (Fall of 6th grade) of self-blame.

This study contributes over and above previous research in several specific ways. First, we extend the study of person-context (mis)match to investigate the interaction between individual and school-level victimization by examining self-blaming attributions. As such, we hope to shed light on previous findings suggesting that victims are more distressed in environments where few others are victimized. By examining victim self-blame as a function of the broader social environment, we seek to understand attributions as contextualized social cognitions. Second, we differentiate the more maladaptive attribution of characterological self-blame from behavioral self-blame—a distinction that has not been made in most past victimization research (e.g., Perren et al., 2013). This distinction is critical inasmuch as the idea that ‘one cannot change the way one is’ makes characterological attributions particularly maladaptive. Third, to examine the contextual variations in self-blame, we focus on a developmentally critical period of early adolescence when social comparisons are salient, especially as youth are adjusting to a new school setting.

Method

The current data were collected as part of a large, longitudinal study of adolescents’ social, emotional, and academic experiences in the middle school years. The sample (N=5,991) was recruited from 26 urban public schools in California, selected to systematically vary in their ethnic compositions.

All school districts provided permission to conduct the study, and during recruitment all students and families received informed consent and informational letters. Students who returned signed consent forms were entered into two separate raffles (to win an Apple iPod and a $50 grocery store gift card). Parental consent rates averaged 81.4% and student assent rates averaged 83.1% across the schools. Only students who turned in signed parental consent and provided written assent participated.

Sample and Procedure

The current sample consisted of 5,991 sixth grade students (51.6% female). Based on self-reported ethnicity, 31.5% were Latino, 19.6% White, 13.3% East/Southeast Asian, 12.0% African American/Black, 13.9% multiethnic/biracial, and 9.7% Other (e.g., Middle Eastern, Pacific Islander). The proportion of students eligible for free/reduced lunch price (a proxy for school SES) ranged from 18.3% to 86.3% (M=47.56, SD= 18.30) across the 26 schools.

Students completed written questionnaires in the Fall and Spring of the sixth grade year within a classroom setting. Prior to completing the questionnaires, students were informed about confidentiality and reminded that participation was voluntary. Researchers read all instructions and questionnaires aloud as students followed along and provided written responses within a protected space. After completing the survey, students received $5 in cash or gift certificate in both the Fall and Spring.

Measures

Perceived peer victimization

Perceptions of peer victimization were measured using four items from an instrument (Neary and Joseph, 1994) designed to reduce social desirability effects (Harter, 1982). For each item, students read two statements separated by the word “but” and were asked first to choose one of these options (e.g., some kids are often picked on but other kids are not picked on). After selecting one statement, students rated if it was “really true” or “sort of true”, such that each item was rated on a 4-point scale. The three other items asked about being called names, being the target of gossip, and being pushed around by others. All four items were averaged (α=.78).

School-level victimization

We calculated a school-level score of victimization based on participants’ self-reports at the beginning of sixth grade. Participants’ self-perceived victimization scores were summed and averaged within each of our 26 schools1, and school-level victimization ranged from 1.55 to 2.35 on the 4-point scale (M=1.94, SD=.20), suggesting that the mean levels were never exceedingly high.

Attributions for victimization

Attributions for victimization experiences were assessed through vignettes; students responded to a different hypothetical victimization incident at each time point (see Graham & Juvonen, 1998). In the Fall, students were presented with a scenario in which they are humiliated in front of their peers at lunch. In the Spring, students read that they are the target of a nasty rumor. For each of the scenarios, students rated on a 5-point scale (1=“Definitely would not think” to 5=“Definitely would think”) how much they agreed with 17 statements assessing different types of causal attributions. Here we specifically focused on six items capturing characterological self-blame (e.g., “more likely to happen to me than to other kids”; “know this will happen to me again”) and three items capturing behavioral self-blame (e.g., “was in wrong place at wrong time”; “should have been more careful”). Confirmatory factor analysis verified the independence of the two factors (CFI=.97, RMSEA=.05). Each set of items were averaged into the two composites, with higher scores indicating greater characterological self-blame (α= .80) and behavioral self-blame (α= .71), respectively.

Results

Below we outline our analysis strategy and report the results of multilevel models. Correlations between the main variables in the Fall (victimization, self-blame) and Spring (self- blame) of 6th grade are presented in Table 1. As shown in the table, characterological self-blame was more highly correlated with victimization and more stable over time than behavioral self-blame. Characterological and behavioral self-blame were moderately correlated, indicating that there was some overlap between the two types of (internal) attributions.

Table 1.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations of Characterological and Behavioral Self-Blame, Self-Perceived Victimization, and School-Level Victimization

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fall Self-Perceived Victimization | -- | |||||

| 2. Fall School-Level Victimization | .249 | -- | ||||

| 3. Fall Characterological Self-Blame | .346 | .129 | -- | |||

| 4. Spring Characterological Self-Blame | .315 | .104 | .515 | -- | ||

| 5. Fall Behavioral Self-Blame | .048 | .097 | .322 | .152 | -- | |

| 6. Spring Behavioral Self-Blame | .091 | .100 | .209 | .377 | .345 | -- |

| Mean | 1.93 | 1.94 | 2.61 | 2.57 | 2.87 | 2.72 |

| Standard deviation | .80 | .20 | .93 | .92 | 1.03 | 1.00 |

Note. All correlations were significant at p<.001.

Multilevel Analysis Strategy

Data were analyzed using maximum likelihood estimation multilevel modeling in SAS PROC MIXED to account for students nested within 26 middle schools. In all analyses we controlled for gender (1=boy, 0=girl) and ethnicity (reference group=Latino, as the largest ethnic group) using dummy coded variables. In both models, we also controlled simultaneously for baseline levels of characterological and behavioral self-blame. This more conservative approach allowed us to examine change in self-blame between the Fall and Spring of the 6th grade. All continuous predictors were grand-mean centered to facilitate interpretation, with the exception of self-perceived victimization. Following centering recommendations for models containing cross-level interactions, we group-mean centered individual-level victimization in order to differentiate within- and between-group effects (see Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

All models included a random intercept, allowing the mean outcome of interest to vary randomly across schools. Following recommended procedures (Hox, 2010), for each set of analyses we first tested a null, intercept-only model to determine the amount of variance predicted by differences among schools in the two outcomes: characterological self-blame and behavioral self-blame. Our second model for each outcome included all main effects, and the third (final) model included the cross-level interaction between self-perceived victimization and school-level victimization. With the addition of each model, we examined differences in deviance values (-2 log likelihood) to compare model fit (Hox, 2010). The comparison of deviance values of the second and third models (i.e., without and with the interaction) allowed us to estimate the effect size of our cross-level interaction of primary interest (i.e., the degree to which its inclusion improved model fit; Peugh, 2010).

Characterological Self-Blame

For characterological self-blame the intraclass correlation (ICC) was .02, suggesting that the majority of variance in characterological self-blame was between individuals (.828) rather than across schools (.017), as expected. Table 2 presents the fixed effects, standard errors, and t-test values for the two subsequent models. As shown in the left column of Table 2, higher levels of Fall victimization and characterological self-blame were significantly associated with subsequent increases in characterological self-blame. There was no overall effect of school-level victimization on change in self-blame. The main effects model showed significantly better fit than our intercept-only model (χ2=3,115.20, df=10, p<.001).

Table 2.

Individual-Level and School-Level Effects of Victimization on Spring Characterological Self-Blame.

| Fall Predictors | Main Effects Model |

Final Model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | t value | Estimate | SE | t value | |

| Intercept | 2.570 | 0.029 | 87.86*** | 2.570 | 0.030 | 87.85*** |

| Sex | −0.007 | 0.021 | −0.31 | −0.007 | 0.021 | −0.31 |

| African American/Black | −0.051 | 0.038 | −1.36 | −0.054 | 0.038 | −1.42 |

| East/Southeast Asian | −0.003 | 0.037 | −0.08 | −0.004 | 0.037 | −0.10 |

| White/Caucasian | −0.025 | 0.033 | −0.76 | −0.023 | 0.033 | −0.71 |

| Multiethnic/Biracial | −0.005 | 0.035 | −0.13 | −0.006 | 0.035 | −0.16 |

| Other | 0.090 | 0.042 | 2.16* | 0.090 | 0.042 | 2.17* |

| Fall Behavioral Self-Blame | −0.010 | 0.011 | −0.91 | −0.009 | 0.011 | −0.86 |

| Fall Characterological Self-Blame | 0.462 | 0.013 | 35.73*** | 0.460 | 0.013 | 35.57*** |

| Fall Self-Perceived Victimization | 0.178 | 0.015 | 12.20*** | 0.182 | 0.015 | 12.39*** |

| Fall School-Level Victimization | 0.175 | 0.104 | 1.68 | 0.176 | 0.104 | 1.69 |

| Self-Perceived | −0.176 | 0.068 | −2.59** | |||

| Victimization X School-Level Victimization | ||||||

| Deviance | 11959.70 | 11953.00 | ||||

| Deviance Change | χ2(10)=3115.20*** | χ2(1)=6.70** | ||||

Note. Sex, 0=girls, 1=boys; Ethnicity reference group=Latino

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05

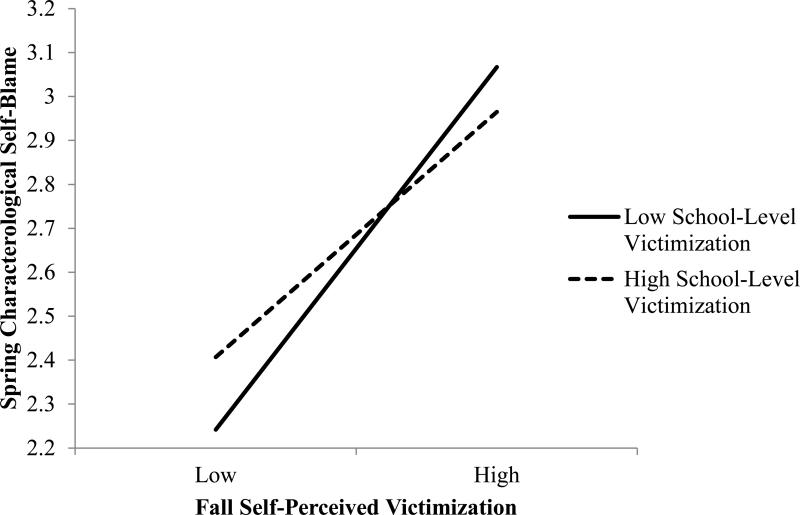

To test our moderator hypothesis about the effect of school-level victimization, we added the cross-level interaction between school-level and student-level victimization. As shown in the right column of Table 2, there was a significant interaction between self-perceived victimization and school-level victimization, b=-.175, p=.010. To probe this interaction, follow-up tests of simple slopes were conducted for individuals attending schools that were either high (1 SD above the mean) or low (-1 SD below the mean) on overall victimization. As seen in Figure 1, for individuals in schools with lower levels of overall victimization, the relationship between Fall victimization and Spring characterological self-blame (b=.217, p<.001) was significantly stronger than for students in schools with higher levels of victimization (b=.146, p<.001). Consistent with our hypotheses, victims come to endorse increasing levels of characterological self-blame when their plight was more unique in their school. In contrast, victims attending a school with higher overall victimization showed weaker increases in characterological self-blaming attributions. Compared to main effects only model, inclusion of the cross-level interaction significantly improved model fit, (χ2=6.70, df=1, p=.010).

Figure 1.

School-Level Victimization Moderates the Association Between Fall Self-Perceived Victimization and Subsequent Characterological Self-Blame

Behavioral Self-Blame

For behavioral self-blame, the intraclass correlation was .03, suggesting that the majority of variability in behavioral self-blame was between individual students (.978) as opposed to between schools (.026).

Similar models were tested as for characterological self-blame. As seen in the left column of Table 3, Latino students reported significantly higher levels of behavioral self-blame compared to Asian, White, or multiethnic students, and both Fall behavioral and characterological self-blame predicted Spring behavioral self-blame (ps<.001). Fall individual- and school-level victimization did not predict change in Spring behavioral self-blame. The main effects model showed significantly better fit than our intercept-only model (χ2=2116.00, df=10, p<.001).

Table 3.

Individual-Level and School-Level Effects of Victimization on Spring Behavioral Self-Blame.

| Fall Predictors | Main Effects Model |

Final Model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | t value | Estimate | SE | t value | |

| Intercept | 2.804 | 0.033 | 84.31*** | 2.804 | 0.033 | 84.26*** |

| Sex | −0.007 | 0.026 | −0.26 | −0.007 | 0.026 | −0.25 |

| African American/Black | 0.001 | 0.046 | 0.02 | 0.003 | 0.046 | 0.07 |

| East/Southeast Asian | −0.101 | 0.044 | −2.28* | −0.100 | 0.044 | −2.26* |

| White/Caucasian | −0.224 | 0.040 | −5.62*** | −0.226 | 0.040 | −5.66*** |

| Multiethnic/Biracial | −0.163 | 0.043 | −3.82*** | −0.162 | 0.043 | −3.80*** |

| Other | −0.047 | 0.050 | −0.94 | −0.047 | 0.050 | −0.94 |

| Fall Characterological Self-Blame | 0.095 | 0.016 | 6.05*** | 0.096 | 0.016 | 6.15*** |

| Fall Behavioral Self-Blame | 0.291 | 0.013 | 21.85*** | 0.290 | 0.013 | 21.81*** |

| Fall Self-Perceived Victimization | 0.034 | 0.018 | 1.92 | 0.031 | 0.018 | 1.73 |

| Fall School-Level Victimization | 0.072 | 0.114 | 0.63 | 0.071 | 0.114 | 0.62 |

| Self-Perceived Victimization X School-Level Victimization | 0.175 | 0.082 | 2.13* | |||

| Deviance | 13904.9 | 13900.4 | ||||

| Deviance Change | χ2(10)=2116.0*** | χ2(1)=4.5* | ||||

Note. Sex, 0=girls, 1=boys; Ethnicity reference group=Latino

p<.001

p<.05

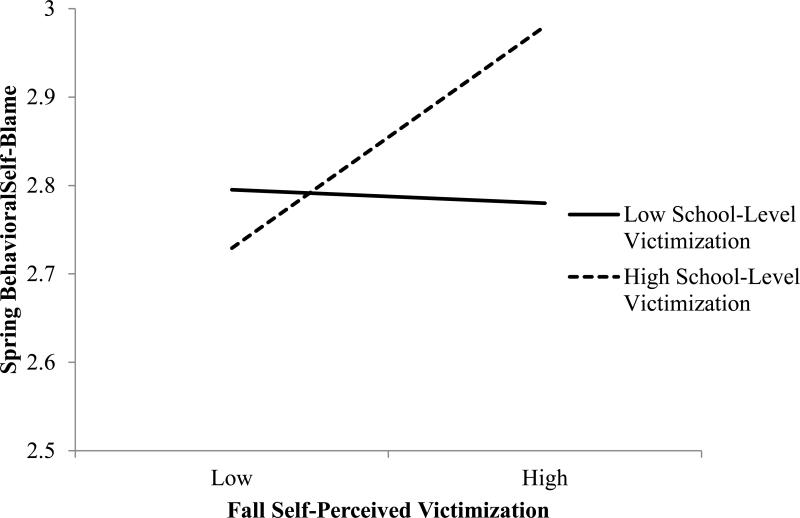

The results of the final model are shown in the right column of Table 3. Again, a significant cross-level interaction between self-perceived victimization and school-level victimization was found, b=.175, p=.033. As seen in Figure 2, for individuals in schools with high levels of overall victimization (1 SD above mean), Fall victimization was related to increases in Spring behavioral self-blame (b=.066, p=.005). In contrast, for students in schools with low levels of overall victimization (1 SD below the mean), victimization was unrelated to subsequent behavioral self-blame (b=-.004, p=.860). That is, consistent with our hypotheses, when victimization was more common at school, victims were more likely to come to blame their behavior. For victims attending a school with less overall victimization, victimization was unrelated to changes in subsequent behavioral self-blame. Compared to the model with main effects only, inclusion of the cross-level interaction significantly improved model fit, (χ2=4.50, df=1, p=.034).

Figure 2.

School-Level Victimization Moderates the Association Between Fall Self-Perceived Victimization and Subsequent Behavioral Self-Blame

Discussion

The current study extends past research on the effects of person-environment mismatch (Stormshak et al., 1999; Wright et al., 1986) by focusing on peer victimization and self-blame. Our findings demonstrate that victimization experiences can come to take on different meanings for youth, depending on the broader school context in which they are interpreted. To be able to understand attributional processes as a function of context, it was critical to differentiate between two types of self-blame: one that implicates one's character and is less controllable and more temporally stable, compared with the other, which implicates one's behavior only. Although self-blame is often discussed as a singular psychological construct, our analyses further support that distinctions between the two types of self-blame are critical (Janoff-Bulman, 1979). The fact that victims who attend schools with lower levels of victimization blame their character (rather than their behavior) also has important implications for antibullying intervention approaches that aim to reduce rates of victimization and do not provide any additional (e.g., attributional) support for victims.

Our findings suggest that in general, being bullied is predictive of heightened characterological, but not behavioral, self-blaming attributions across the 6th grade school year. However, these associations are moderated by the school victimization context; victims’ beliefs that ‘it's all my fault’ are exacerbated in schools with overall lower rates of victimization, whereas victims’ attributions to more unstable and controllable self-related factors only increase when overall victimization is high. In schools with less victimization, bullied students are likely to feel “different” and singled out. The finding that targets of bullying in lowvictimization, compared to higher-victimization, schools show steeper increases in characterological self-blame is also concerning, given the long-term cyclical associations between this maladaptive attributional style and adjustment. In addition to being related to depressive thoughts and feelings of low self-worth (Graham & Juvonen, 1998), characterological self-blaming attributions—by fostering negative expectancies for the future and negative affect—can promote continued victimization and peer rejection (Coyne, 1976; Schacter et al., 2014). As such, in future studies it will be important to consider how chronicity of victimization over time relates to both types of self-blame, as well as the school social context.

Our large, diverse sample and the short-term longitudinal analyses across the first year of middle school are strengths of the current study. By examining attributional data from both Fall and Spring we were able to examine changes in the two types of self-blame across sixth grade. Studying these processes longitudinally across the first year of middle school is also conceptually important. Specifically, we presumed that causal attributions may be particularly sensitive to school context when young adolescents are acclimating to a new school. School transitions present opportunities for social reorganization and status enhancement; youth's attentiveness to peer behavior and norms may therefore be heightened when making sense of their own experiences (Eccles et al., 1993). The transition to middle school is also a time when bullying peaks (Pellegrini & Long, 2002), and experiencing victimization during this time can shape students’ expectations for the future. Believing that one's plight is due to unstable and controllable behavioral factors, compared to uncontrollable and stable characteristics, may set students on distinctly different adjustment paths. This is evidenced by research showing that maladaptive beliefs about the self and one's abilities during the middle school transition predict later school-related stress and depression (Rudolph, Lambert, Clark, & Kurlakowsky, 2001). As such, it is important to understand the conditions under which adolescents make characterological versus behavioral self-blaming attributions during times of change.

In terms of limitations, the effect sizes were small in magnitude, and as such the current results must be interpreted with some caution. Notably, however, our analyses were conservative insofar as they examined associations between Fall and Spring of the same school year by controlling for baseline levels of both characterological and behavioral self-blame. It should also be noted that there were no main effects of school-level victimization on self-blame, perhaps due to the low degree of between-school variability in attributions (i.e., interpretations of personal experiences). As such, future research should continue exploring distinct person-level predictors that can account for variability self-blame (e.g., depressive symptoms, social experiences prior to middle school) and contextual moderators of these links. Given the distinctly different patterns of findings for characterological versus behavioral self-blame, it will also be important to reconsider the findings of past studies that analyze ‘self-blame’ more generally. For example, in a sample of early adolescents, Perren and colleagues (2013) found no relationship between self-blame and victimization or internalizing symptoms across the 6th grade by relying on this general index of self-blame. It will also be important to examine how the school context influences other types of victim attributions; supplemental analyses from the current study (not reported here) indicated that victims were not only more likely to endorse characterological self-blaming attributions in schools with less overall victimization, but also less likely to make external, luck-related attributions (e.g., “Stuff happens, it was just one of those days”) in these contexts. That is, schools with lower levels of bullying increase the likelihood that the remaining victims interpret their plight as their own fault, and decrease the likelihood that they endorse psychologically adaptive explanations.

We focused on one specific feature of the school context; however, past research shows that attributions can be shaped by other contextual characteristics, such as school ethnic composition. For example, Graham and colleagues (2009) found that students endorsed more characterological self-blame when victimized in schools with more same-ethnic peers. That is, being bullied when one's ethnic group was in (numerical) power, as opposed to belonging to a numerical minority at school, resulted in blaming one's character. These results are consistent with the current findings, inasmuch as one would presume that belonging to a numerical majority, much like attending a school with less overall victimization, should be a protective factor. Thus, school-level victimization is not the only contextual factor contributing to heightened characterological self-blame among bullied youth.

Conclusions

Most school-wide interventions aim to reduce overall levels of bullying and victimization (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011). Although school personnel likely experience relief when bullying rates drop, it is precisely under these conditions that victims may feel more helpless and liable for their own mistreatment. Given that interventions will never be able to eliminate bullying altogether, the collective and individual gains of such efforts may be inversely related. Overall reductions in victimization do not lessen its emotional impact among the ones who continue to get bullied; as such, interventions must attend to the specific needs of the victimized and understand their contextualized social cognitions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (No. 1R01HD059882-01A2) and National Science Foundation (No. 0921306). This material is also based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-1144087. Any opinion, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or National Science Foundation. The authors would also like to thank all members of the UCLA Middle School Diversity Project for their ongoing assistance with the study, as well as Ariana Bell, Daisy Camacho, Sandra Graham, Leah Lessard, and Danielle Smith for their comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Based on the high rates of participation in all of our schools, we consider the average of grade-level victimization scores at each school to be a good estimate of school-level victimization.

Contributor Information

Hannah L. Schacter, Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles

Jaana Juvonen, Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles.

References

- Bellmore AD, Witkow MR, Graham S, Juvonen J. Beyond the individual: The impact of ethnic context and classroom behavioral norms on victims' adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40(6):1159–1172. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1159. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85(2):186–193. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.2.186. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.85.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Midgley C. Stage/environment fit: Developmentally appropriate classrooms for early adolescents. In: Ames R, Ames C, editors. Research on motivation in education. Academic Press; New York: 1989. pp. 139–181. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Midgley C, Wigfield A, Buchanan CM, Reuman D, Flanagan C, Iver DM. Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist. 1993;48(2):90–101. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.2.90. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/index.cfm?fa=buy.optionToBuy&id=1993-21234-001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Juvonen J. Self-blame and peer victimization in middle school: An attributional analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(3):587. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.3.587. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Bellmore A, Nishina A, Juvonen J. “It must be me”: Ethnic diversity and attributions for peer victimization in middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(4):487–499. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9386-4. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development. 1982;53(1):87–97. doi: 10.2307/1129640. [Google Scholar]

- Hox JJ. Multilevel Analyses. Techniques and applications. Routledge; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Huitsing G, Veenstra R, Sainio M, Salmivalli C. “It must be me” or “It could be them?”: The impact of the social network position of bullies and victims on victims’ adjustment. Social Networks. 2012;34(4):379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2010.07.002. [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R. Characterological versus behavioral self-blame: Inquiries into depression and rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37(10):1798–1809. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.37.10.1798. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.10.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary A, Joseph S. Peer victimization and its relationship to self-concept and depression among school-girls. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994;16(1):183–186. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(94)90122-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD, Long JD. A longitudinal study of bullying, dominance, and victimization during the transition from primary school through secondary school. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2002;20(2):259–280. doi: 10.1348/026151002166442. [Google Scholar]

- Perren S, Ettekal I, Ladd G. The impact of peer victimization on later maladjustment: Mediating and moderating effects of hostile and self-blaming attributions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54(1):46–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02618.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peugh JL. A practical guide to multilevel modeling. Journal of School Psychology. 2010;48(1):85–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2009.09.002. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Cheah CS, Guyer AE. Peer victimization, cue interpretation, and internalizing symptoms: Preliminary concurrent and longitudinal findings for children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34(1):11–24. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_2. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd ed. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Alvarez JM, Bachman M, Cameron JA, Fuligni AJ, Garcia Coll C, Rhee E. The development of a sense of ‘we’: The emergence and implications of children’s collective identity. In: Bennett M, Sani F, editors. The development of the social self. Psychology Press; East Sussex, England: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Lambert SF, Clark AG, Kurlakowsky KD. Negotiating the transition to middle school: The role of self-regulatory processes. Child Development. 2001;72(3):929–946. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00325. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter HL, White SJ, Chang VY, Juvonen J. “Why Me?”: Characterological self-blame and continued victimization in the first year of middle school. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology (ahead-of-print) 2014 doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.865194. doi:10.1080/15374416.2013. 865194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentse M, Scholte R, Salmivalli C, Voeten M. Person–group dissimilarity in involvement in bullying and its relation with social status. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35(6):1009–1019. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9150-3. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons RG, Blyth DA. Moving into adolescence: The impact of pubertal change and school context. Aldine; New York, NY: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Bierman KL, Bruschi C, Dodge KA, Coie JD. the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. The relation between behavior problems and peer preference in different classroom contexts. Child Development. 70(1):169–182. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00013. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ttofi MM, Farrington DP. Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2011;7(1):27–56. doi: 10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B. An attributional theory of motivation and emotion. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Wright JC, Giammarino M, Parad HW. Social status in small groups: Individual–group similarity and the social “misfit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50(3):523. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.523. [Google Scholar]