Abstract

Objective

To assess age differences between first parental concern and first parental discussion of concerns with a health care provider, among children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) versus intellectual disability/developmental delay (ID/DD), and to assess whether provider response to parental concerns is associated with delays in ASD diagnosis.

Study design

Using nationally-representative data from the 2011 Survey of Pathways to Diagnosis and Treatment, we compared child age at parent’s first developmental concern with age at first discussion of concerns with a provider, and categorized provider response as proactive vs. reassuring/passive, among 1420 children with ASD and 2098 children with ID/DD. Among children with ASD, we tested the association between provider response type and years of diagnostic delay.

Results

Compared with children with ID/DD, children with ASD were younger when parents first had concerns and first discussed those with a provider. Parents of children with ASD were less likely than parents of children with ID/DD to experience proactive responses to their concerns and were more likely to experience reassuring/passive responses. Among children with ASD, those with more proactive provider responses to concerns had shorter delays in ASD diagnosis. In contrast, children with ASD having passive/reassuring provider responses had longer delays.

Conclusions

Although parents of children with ASD have early concerns, delays in diagnosis are common, particularly when providers’ responses are reassuring or passive, highlighting needs for targeted improvements in primary care.

Keywords: Autistic Disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Behavioral Problems, Child Development Disorders, Pervasive, Communication, Developmental Disabilities, Developmental Problems, Delayed Diagnosis, Intellectual Disability, Health Services Accessibility, Parents“ concerns

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a common neurodevelopmental condition of early childhood which is associated with atypical social communication and interaction as well as restricted and repetitive behaviors.(1) ASDs affect between 1 and 2 percent of U.S. children,(2–4) and the condition is becoming more prevalent,(2,3) making early identification an important public health consideration. Early signs of ASD can be recognized by a trained professional earlier than age two years,(5) and early identification is associated with improved long-term developmental and family outcomes.(6–10) Because the lifetime cost of treating an individual with ASD exceeds $1 million in the US, efforts to identify promptly and treat ASD symptoms and comorbidities may also affect long-term costs.(11–13) Unfortunately, however, many children with ASD are not diagnosed until school age,(14–17) and poor, minority, and less-severely impaired children are often diagnosed even later.(15,18–21)

How health care providers elicit and respond to early parent developmental concerns may influence age of ASD detection. Parents are likely to mention developmental concerns first to a pediatric health care provider because providers have frequent early contact with families. However, studies suggest that many providers do not effectively elicit parent developmental concerns,(22,23) even when a child is at risk for developmental delay.(22) To bolster early identification of ASD and other delays, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends standardized primary care-based screening for ASD and/or other developmental problems.(5,24) Nonetheless, many primary care providers do not follow screening guidelines,(25–27) and even when they do follow guidelines, many do not feel comfortable identifying children at risk for ASD.(28)

Additionally, because obtaining an ASD diagnosis typically requires specialty referral,(5) health care providers may serve as gatekeepers in access to diagnostic and treatment services. Previous research shows that parents experience long delays between initial evaluation and ASD diagnosis,(20) and that providers often inappropriately reassure families who need ASD specialty consultation.(29) However, no studies have examined how provider response to parent developmental concerns relates to age of ASD diagnosis. Furthermore, no studies have examined whether provider responses differ among children with ASD compared with children who have other early developmental conditions, such as developmental delay (DD) or intellectual disability (ID), which are more common (30) and may have similar presenting symptoms.

Therefore, this study aimed in a nationally-representative dataset to assess how health care providers responded to parents’ early developmental concerns, whether responses differed among children who developed ASD versus other developmental conditions, and whether the quality of the provider response was associated with timeliness of ASD diagnosis.. Our specific research questions were: (1) Did child age at first parent concern and first parent conversation with provider differ among children eventually diagnosed with ASD compared with those diagnosed with DD or ID?; (2) Did provider response to concerns differ among these conditions?; and (3) Among children with ASD, was a more proactive/less reassuring provider response to parent concerns associated with earlier ASD diagnosis?

Methods

Data came from the 2011 Survey of Pathways to Diagnosis and Services (herein called Pathways Survey), a nationally-representative, parent-reported survey of children ever diagnosed with ASD, ID, and/or DD and who also qualified as children with special health care needs (CSHCN) as assessed by the CSHCN Screener, a non-condition-specific measure.(31) The Pathways Survey was as a follow-up to the 2009/10 National Survey of CSHCN (NS-CSHCN). Parents or guardians who completed the NS-CSHCN, who reported that their child was ever diagnosed with ASD, ID, and/or DD, and whose child was age 6–17 years in 2011, were re-contacted to participate in the Pathways Survey. 71% were successfully re-contacted; 87% of those contacted agreed to participate (n = 4032).(32) In the survey, a parent or guardian (herein called “parent”) was interviewed about one randomly-selected CSHCN with ASD, ID, and/or DD per household.

We compared CSHCN with ASD (herein called “children with ASD”) to CSHCN with ID and/or DD (herein called “children with ID/DD”). Children with ASD were defined as CSHCN whose parent stated in the NS-CSHCN that the child was diagnosed by a doctor or health care provider with “autism, Asperger’s disorder, pervasive developmental disorder, or other autism spectrum disorder,”(33) who had the condition at the time of the NS-CSHCN survey, and who still had it when re-contacted for the Pathways Survey.(32)

Children with ID were defined as CSHCN whose parent stated the child was diagnosed by a doctor or health care provider with “intellectual disability or mental retardation” and had the condition at the time of the NS-CSHCN survey and when re-contacted for the Pathways Survey. Children with DD were defined as CSHCN whose parent stated that the child was diagnosed with “a developmental delay that affects [his/her] ability to learn” and had the condition at the time of the NS-CSHCN survey(33) and when re-contacted for the Pathways Survey.(32) Children with ID and/or DD were grouped for analytic purposes. To assess comorbidity between ASD and ID/DD, we analyzed children with ASD overall (regardless of ID/DD comorbidity; called “ASD overall”), and subgroups of children having both conditions (“ASD with co-existing ID/DD”), and those having ASD without ID/DD (“ASD only”). Children who had ASD, ID, and/or DD in the past but not currently, were excluded (12.7%; n = 514).

Measures

We studied three time-points in a child’s diagnostic history. The first time-point was age of first parental concerns, defined as the child’s age when the parent “first wondered if there might be something not quite right with [the child]’s development.” If parent concerns were present since birth, age was coded as 0 years. Another time-point was the age when the parent “first talked with a doctor or health care provider about [their] concerns.” The third time-point, assessed only among children with ASD, was age of ASD diagnosis. This was assessed by asking, “How old was your child when you were first told that [he/she] had autism or autism spectrum disorder [by a health care provider]?” For all age-related variables we assessed in the Pathways survey, parents provided age in years and months up to age 36 months and in years after 36 months. To standardize findings across younger and older age ranges, and because many of the ages and age-related intervals studied spanned the 36-month age time point, we rounded down months to whole completed years (e.g. 6 months or 11 months = 0 years, 15 months or 23 months = 1 year), so that measures would be comparable across the entire age span.

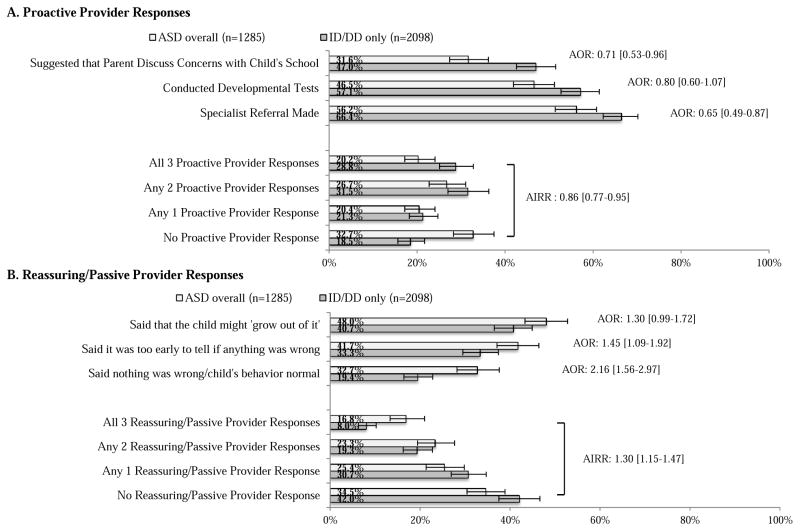

We also assessed provider’s response to parents’ first concerns via yes/no report of six provider actions. These actions, which were developed for the Pathways Survey from the Pennsylvania Autism Needs Assessment (34), could be categorized into two domains. Proactive provider responses included three possible actions: “conducting developmental tests,” “making a referral to a specialist; such as a developmental pediatrician, child psychologist, occupational, or speech therapist,” and “discussing concerns with the child’s school.” Reassuring/passive provider responses also included three possible actions: saying “nothing was wrong, the behavior was normal,” that “it was too early to tell if anything was wrong,” or that “the child might ‘grow out of it.’ “ We also enumerated cumulative proactive and reassuring/passive responses to see if multiple proactive or reassuring/passive responses had an additive effect (Figure; available at www.jpeds.com).

Figure 1. Weighted Proportions, 95% Confidence Intervals and Adjusted ORs of Provider Responses among US CSHCN Age 6–17 Years, by Current ASD Status.

Adjusted odds ratio [AOR] estimated with multivariable logistic regression, comparing odds of the selected provider response in ASD overall versus ID/DD only. Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratios [AIRR] estimated with Poisson regression models and indicate the rate of proactive or reassuring passive provider responses among CSHCN with ASD compared to the rate for CSHCN with ID/DD only.

Because child and family factors could confound the relationships between parent concerns, provider response, and delays in ASD diagnosis, we measured child and family socio-demographic factors previously associated with differences in health status,(35) health care quality and access(36–39), or severity of developmental disorders.(37,40) Child-level covariates included child age, sex, race/ethnicity, presence of functional limitations, and health insurance type. Family-level covariates included U.S. region of residence, household income, parental educational level, and family structure (Table I).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics among CSHCN Age 6–17 years, by Current ASD, DD and ID Status

| Variable | ASD overall (n=1420) | ASD with co-existing ID/DD (n = 924) | ASD only (n = 496) | ID/DD only (n= 2098) | P value ASD overall versus ID/DD onlya | P value ASD with co-existing ID/DD versus ID/DD onlya | P value ASD only versus ID/DD onlya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted Proportion (estimated number of CSHCN age 6–17 years who currently have ASD, DD, and/or ID)b | 36.2% (653,041) | 24.0% (434,000) | 12.2% (220,000) | 63.8% (1.15 million) | |||

| Child Characteristics | |||||||

| Age (y) | |||||||

| 6–8 (n=632) | 20.9% | 19.6% | 23.6% | 17.8% | P =.03 | P = .19 | P = .12 |

| 9–11 (n=1089) | 33.7% | 36.0% | 29.3% | 30.2% | |||

| 12–14 (n= 992) | 25.6% | 23.6% | 29.7% | 26.5% | |||

| 15–17 (n= 805) | 19.7% | 20.9% | 17.3% | 25.5% | |||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male (n=2436) | 82.1% | 79.0% | 88.2% | 62.8% | P <.001 | P < .001 | P < .001 |

| Female (n=1079) | 17.9% | 21.0% | 11.8% | 37.2% | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic (n=313) | 13.0% | 12.9% | 13.2% | 13.5% | P =.05 | P = .06 | P = .06 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic (n=305) | 10.7% | 11.4% | 9.3% | 18.5% | |||

| Other Race, Non-Hispanic (n=358) | 10.1% | 12.5% | 5.3% | 8.3% | |||

| White, Non-Hispanic (n=2513) | 66.2% | 63.2% | 72.2% | 59.7% | |||

| Functional Limitations | |||||||

| Yes (n=1994) | 64.6% | 73.0% | 47.9% | 51.1% | P <.001 | P < .001 | P = .49 |

| No (n=1524) | 35.4% | 27.0% | 52.1% | 48.9% | |||

| Health Insurance Type | |||||||

| Public Insurance Only (n=1169) | 32.1% | 37.9% | 20.9% | 51.7% | P <.001 | P < .001 | P < .001 |

| Any Private Insurance (n= 2139) | 67.9% | 62.1% | 79.1% | 48.3% | |||

| Family Characteristics | |||||||

| Region of Residence | |||||||

| West (n=1014) | 20.3% | 20.2% | 20.4% | 21.4% | P =.31 | P = .65 | P = .53 |

| Midwest (n=810) | 24.5% | 22.1% | 29.4% | 24.9% | |||

| South (n=1037) | 33.8% | 36.1% | 29.4% | 34.8% | |||

| Northeast (n=657) | 21.4% | 21.6% | 20.8% | 18.8% | |||

| Household Income Level | |||||||

| 0%–99% FPL(n=635) | 16.9% | 19.9% | 11.0% | 30.9% | P <.001 | P = .004 | P < .001 |

| 100%–199% FPL (n=727) | 20.5% | 21.5% | 18.4% | 22.1% | |||

| 200%–399% FPL (n= 1127) | 32.7% | 33.0% | 32.1% | 26.5% | |||

| ≥400% FPL (n= 1029) | 29.9% | 25.6% | 38.4% | 20.5% | |||

| Highest Parental Education Level | |||||||

| High school or less (n= 699) | 23.4% | 28.2% | 13.8% | 51.1% | P <.001 | P = .02 | P < .001 |

| >High school (n=2819) | 76.6% | 71.8% | 86.2% | 48.9% | |||

| Family Structure | |||||||

| Single mother (n=677) | 22.6% | 22.0% | 23.7% | 30.7% | P <.001 | P = .003 | P = .02 |

| Other (n=668) | 16.9% | 17.8% | 15.1% | 21.8% | |||

| 2 parent biological or adopted (n= 2152) | 60.5% | 60.2% | 61.2% | 47.5% | |||

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CSHCN, children with special health care needs; DD, developmental delay; FPL, federal poverty level; ID, intellectual disability.

Omnibus Pearson chi-square test P-value considering all groups in the category,

A total of 3518 CSHCN were reported to currently have ASD, DD, and/or ID during the 2011 Survey of Pathways to Diagnosis and Treatment, representing the non-institutionalized population of CSHCN age 6–17 years currently with these three conditions. CSHCN who were not reported to currently have any of these three conditions (n=514) were excluded from this analysis.

Data analyses

Analyses were performed in STATA 13.1 (College Station, Texas). All analyses were adjusted using sampling weights from the NS-CSHCN and the Pathways survey, which compensate for the probability of being selected for the survey, non-response, and incomplete information on ineligibility, among other factors. Weighted results are representative of the US non-institutionalized population of children age 6–17 years diagnosed with ASD, intellectual disability, and/or developmental delay (41).

We used descriptive statistics and weighted chi-square tests to compare socio-demographic characteristics between ASD and ID/DD only, and among ASD subgroups. We computed mean child age at first parent developmental concerns and mean child age at first parent discussion with provider, using two-sample t-tests, comparing ASD (both overall, and with or without comorbid ID/DD) versus ID/DD only groups. We computed mean age of ASD diagnosis for the ASD groups only (Table II). We then computed two time intervals: (1) time between first parent concerns and first provider conversation (assessed in all groups), and (2) time between first provider conversation and age of ASD diagnosis (assessed in ASD groups only). We used weighted t-tests to compare time from concerns to provider conversation in children with ID/DD versus children with ASD (with and without comorbid ID/DD; Table II).

Table 2.

Diagnostic Experiences among CSHCN Age 6–17 Years, by Current ASD, DD and ID Status

| Mean Times Based on Child’s Age in Years (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD overall | ASD with co-existing ID/DD | ASD only | ID/DD only | |

| Mean child age in years of first parent concerns about child’s development (n= 3424)a | 2.1 (1.9–2.3) | 1.9 (1.7–2.2) | 2.5 (2.2–2.8) | 3.0 (2.6–3.4) |

| Mean child age in years of parent’s first discussion of concerns with a health care provider (n= 3233) | 2.3 (2.2–2.5) | 2.0 (1.8–2.2) | 3.0 (2.6–3.3) | 3.2 (2.9–3.6) |

| Mean child age in years when parent was first told the child had ASD (n=1414) | 5.2 (4.9–5.5) | 4.8 (4.5–5.1) | 6.0 (5.5–6.5) | — |

| Mean time in years between first parental concerns about child’s development and first discussion of concerns with provider (n=3158) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.1 (−0.1–0.3) | 0.4 (0.2–0.5) | 0.3 (0.1–0.4) |

| Mean time in years between first discussion of concerns with a provider and age of ASD diagnosis (n=1282) | 2.7 (2.5–3.0) | 2.6 (2.3–2.9) | 3.0 (2.5–3.5) | — |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CI, confidence interval; CSHCN, children with special health care needs; DD, developmental delay; ID, intellectual disability.

Children whose parents indicated that they had concerns about the child’s development since birth were coded as having concerns since the child was age 0.

— Indicates the data are not available.

P values were computed using Adjusted Wald Tests that compared weighted means between the indicated condition subgroups.

Because ASD can be confidently diagnosed before age 3 years,(5) we created a dichotomous outcome reflecting a diagnostic delay that would be considered long regardless of age: delay between provider conversation and age of ASD diagnosis ≥ 3 years. We computed the percent of children with ASD experiencing this delay.

Provider response to parent concerns

We computed the frequency of each proactive and each reassuring/passive provider response in ASD overall and in ID/DD. We then compared proactive and reassuring/passive provider responses in ID/DD to ASD overall using weighted chi-square tests and multivariable logistic regression. We also compared the count and adjusted incidence rate ratio (AIRR) of proactive versus reassuring/passive responses for the two condition groups, using weighted chi-square tests and Poisson regression respectively, where ID/DD was the referent group (Figure). Descriptive statistics computed for the proactive and reassuring/passive provider response counts indicated the equidispersion assumption was met. Finally, we compared each of the ASD subgroups (ASD with co-existing ID/DD and ASD only) to ID/DD only using similar statistical methods (Table III; available at www.jpeds.com). Regression models adjusted for all socio-demographic covariates listed above.

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios and relative risk ratios of proactive or reassuring/passive provider responses in ADHD+ID, ADHD-ID, and ID no ASD

| Percentage in category with provider response (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratios or Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD with co-existing ID/DD | ASD only | ID/DD only | ASD with co-existing ID/DD | ASD only | ID/DD only | |

| Proactive Responses | ||||||

| Suggested that parent discuss concerns with school | 30.1% (25.0–35.7) | 35.0% (27.6–43.1) | 47.0% (42.7–51.5) | .69 (.48 – .98)b | .77 (.51 – 1.17)b | 1.00 |

| Conducted developmental tests | 49.3% (43.5–55.1) | 40.8% (33.3–48.8) | 57.1% (52.7–61.4) | .92 (.66 – 1.28)b | .59 (.39 – .90)b | 1.00 |

| Specialist referral made | 57.6% (51.6–63.3) | 53.3% (45.2–61.2) | 66.4% (62.4–70.2) | .69 (.50 – .97)b | .57 (.38 – .85)b | 1.00 |

| No Proactive Provider Response | 31.6% (26.2–37.6) | 35.0% (27.6 – 43.2) | 18.5% (15.6 – 21.7) | 0.88 (0.78–0.98)c | 0.81 (0.69–0.94)c | 1.00 |

| Any 1 Proactive Provider Response | 20.6% (16.7 – 25.1) | 20.1% (14.9 – 26.6) | 21.3% (18.2 – 24.7) | |||

| Any 2 Proactive Provider Responses | 27.1% (22.4 – 32.4) | 25.8% (19.0 – 33.9) | 31.5% (27.0 – 36.3) | |||

| All 3 Proactive Provider Responses | 20.7% (16.4 – 25.8) | 19.1% (13.9 – 25.8) | 28.8% (25.1 – 32.8) | |||

| Reassuring/Passive Responses | ||||||

| Said the child might “grow out of it” | 46.7% (40.9–52.6) | 50.7% (42.7–58.7) | 40.7% (36.5–44.9) | 1.27 (.93 – 1.74)b | 1.37 (.93 – 2.02)b | 1.00 |

| Said it was too early to tell if anything was wrong | 38.3% (32.8–44.0) | 48.8% (40.8–56.9) | 33.3% (29.5–37.4) | 1.29 (.94 – 1.77)b | 1.85 (1.25 – 2.75)b | 1.00 |

| Said nothing was wrong/child’s behavior normal | 31.5% (26.0–37.7) | 35.1% (27.7–43.4) | 19.4% (16.43–22.8) | 2.00 (1.39 – 2.89)b | 2.49 (1.62 – 3.85)b | 1.00 |

| No Reassuring/Passive Provider Response | 36.5% (31.5 – 41.9) | 30.4% (23.8 – 38.0) | 42.0% (37.5 – 46.6) | 1.25 (1.08–1.43)c | 1.41 (1.19–1.66)c | 1.00 |

| Any 1 Reassuring/Passive Provider Response | 26.2% (21.1– 32.1) | 23.6% (17.9 – 30.4) | 30.7% (26.9 – 34.7) | |||

| Any 2 Reassuring/Passive Provider Responses | 21.5% (17.0 – 26.7) | 27.0% (20.2 – 35.2) | 19.3% (16.3 – 22.8) | |||

| All 3 Reassuring/Passive Provider Responses | 15.8% (11.8 – 20.9) | 19.0% (13.0 – 27.0) | 8.0% (6.3 – 10.2) | |||

All models adjusted for child age, sex, race/ethnicity, household income, insurance type, functional limitations, family structure and highest parental education level.

Adjusted odds ratio from multivariable logistic regression model compares the odds of the selected provider response among CSHCN with ASD+ID/DD or CSHCN+ASD only versus CSHCN with ID/DD only

Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratios were estimated with Poisson regression models and indicate the rate of proactive or reassuring passive provider responses among CSHCN with ASD+ID/DD or CSHCN with ASD is compared to the rate for CSHCN with ID/DD only.

Associations between provider response and diagnostic delay

In the ASD group only, we tested whether provider response type was associated with diagnostic delay by modeling mean diagnostic delay as well as the dichotomous probability of ≥ 3 years diagnostic delay. Tobit regression was used to model mean diagnostic delays according to each provider response because the sample distribution of diagnostic delays was left-censored at 0 (n = 223) and age values were standardized to years in the entire sample.(42) To fit parsimonious models, stepwise regression using backward elimination was used in which mean diagnostic delay was regressed on all socio-demographic variables and presence of functional limitations, maintaining variables with coefficients significant at p <.10. The variables retained were child age, household income, health insurance type, and region. To assess whether ASD with comorbid ID/DD significantly modified associations between provider response type and diagnostic delay, ID/DD status as well as interaction terms between ID/DD status and each provider response were modeled, but were found not to have any significant effect, and were therefore eliminated from final analyses.

To assess whether provider response type was associated with the probability of ≥ 3 years of diagnostic delay, multivariable logistic regression was used with the same covariates included in Tobit regression models. To assess multicollinearity, variance inflation factors were calculated for all models; all variance inflation factors were <10, suggesting multicollinearity did not substantially bias model estimates.

Results

Of the 4,032 CSHCN sampled in the Pathways Survey, 2098 (63.8% of the sample) were identified as having current ID/DD, and 1420 (36.2%) had current ASD. Of those with ASD, 924 (65.1%) had co-existing ID/DD, and 496 (34.9%) had ASD only. Compared with children with ID/DD only, children with ASD overall were more likely to be younger, male, have higher household income, be privately insured, have higher parental education, live in a 2-parent family, and have functional limitations. Among ASD subgroups, children with ASD only had similar proportions of functional limitations compared with ID/DD, whereas children with ASD and co-existing ID/DD had significantly higher rates of functional limitations than children with ID/DD only (Table I).

Initial concerns and discussion with provider

Compared with children with ID/DD only, those with ASD overall had a lower age of initial parental concern (2.1 versus 3.0 years) and initial discussion of concerns with a provider (2.3 versus 3.2 years). Time between first parent concerns and first discussion of concerns with provider was similar (Table II).

Among the ASD subgroups, ASD with co-existing ID/DD had lower age of first concerns (1.9 years) compared with ASD only (2.5 years) and ID/DD only (3.0 years). Age of discussion with provider was significantly earlier in ASD with co-existing ID/DD (2.0 years) compared with ID/DD only (3.2 years). The ASD only group was similar to the ID/DD only group. Time between first concerns and first provider discussion was similar in both ASD subgroups compared with ID/DD (Table II).

Provider response to early parent concerns

Bivariate results showed children with ASD overall were less likely than those with ID/DD only to have each proactive provider response to parent concerns (Figure). They were also significantly less likely than children with ID/DD to have all 3 proactive provider responses. Controlling for covariates, significant differences between the ASD and ID/DD groups persisted for all items, except “provider conducted developmental tests,” which neared significance (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.80 [95% CI 0.60–1.07]; Figure). Overall, children with ASD had 14% fewer proactive provider responses than children with ID/DD, adjusting for covariates (adjusted incidence rate ratio [AIRR] 0.86 [95% CI: 0.77–0.95]).

Likewise, children with ASD overall were significantly more likely than those with ID/DD only to have each reassuring/passive provider response, and were significantly more likely to have all 3 reassuring/passive responses (Figure). Findings persisted after adjusting for covariates, except “said child might ‘grow out of it,’” which neared significance (AOR 1.30 [95% CI: 0.99–1.72]; Figure). Overall, children with ASD had 30% more reassuring/passive provider responses than children with ID/DD, controlling for covariates (AIRR 1.30 [95% CI: 1.15–1.47]).

Comparing the ASD subgroups, there was no consistent trend as to whether provider responses were more proactive in ASD with co-existing ID/DD versus ASD only, and differences between the two groups were slight. Both groups showed trends toward lower rates of proactive provider responses and higher rates of reassuring/passive responses compared with ID/DD only (Table III).

ASD diagnostic delays

On average, children with ASD were diagnosed at 5.2 years. Children with ASD and co-existing ID/DD were diagnosed earlier (4.8 years) compared with ASD only (6.0 years). Mean delay between first conversation with provider and ASD diagnosis was 2.7 years overall, which did not significantly vary by the presence of co-existing ID/DD (Table II). Overall, 44.0% of CSHCN with ASD experienced ≥3 year delay between first provider conversation and ASD diagnosis.

Relationship of provider response to concerns and diagnostic delay

Bivariate and multivariate analysis results showed each proactive provider response to parents’ concerns was associated with reduction in the mean delay between first conversation and ASD diagnosis by at least 1 year. Proactive responses appeared to have a cumulative effect, where having more proactive responses was associated with greater decreases in mean diagnostic delay. Additionally, the odds of a ≥3 year diagnostic delay between first provider conversation and ASD diagnosis was significantly reduced for each proactive response type, and decreased monotonically with the number of proactive responses (Table IV).

Table 4.

Weighted Tobit and Logistic Regression Model Results for Delay between Parent’s First Conversation with Provider and Child’s Initial ASD Diagnosis in Relationship to Provider Responses, Among all Children with ASD

| Unadjusted mean years of delay (SE)b | Adjusted mean years of delay (SE)a,b | Weighted proportion with response having ≥ 3 years delay | AOR of ≥ 3 years delay (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proactive Provider Responses | ||||

| Provider Conducted Developmental Tests | −1.3 (0.3) | −1.2 (0.3) | 35.8% | 0.57 (0.38 – 0.84) |

| Provider Made Referral to Specialist | −1.6 (0.3) | −1.4 (0.3) | 34.4% | 0.47 (0.31 – 0.69) |

| Provider Suggested that Parent Discuss Concerns with Child’s School | −1.3 (0.4) | −1.4 (0.3) | 32.0% | 0.47 (0.30 – 0.72) |

| Any 1 Proactive Provider Response | −0.9 (0.4) | −0.8 (0.3) | 43.4% | 0.60 (0.36–0.99) |

| Any 2 Proactive Provider Responses | −1.6 (0.4) | −1.4 (0.4) | 36.8% | 0.45 (0.26–0.77) |

| All 3 Proactive Provider Responses | −2.3 (0.4) | −2.2 (0.3) | 29.2% | 0.31 (0.17–0.54) |

| Reassuring/Passive Provider Responses | ||||

| Provider said nothing was wrong/child’s behavior was normal | 1.4 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.3) | 54.5% | 1.79 (1.16 – 2.77) |

| Provider said it was too early to tell if anything was wrong | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.3) | 49.9% | 1.66 (1.11 – 2.47) |

| Provider said that the child might ‘grow out of it’ | 1.3 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.3) | 53.0% | 2.02 (1.36 – 3.01) |

| Any 1 Reassuring/Passive Provider Response | 1.7 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.4) | 50.5% | 2.44 (1.46 – 4.07) |

| Any 2 Reassuring/Passive Provider Responses | 2.2 (0.4) | 2.2 (0.4) | 55.3% | 2.35 (1.39 – 4.00) |

| All 3 Reassuring/Passive Provider Responses | 2.1 (0.4) | 2.0 (0.4) | 54.2% | 3.06 (1.63 – 5.75) |

Abbreviations: AOR, Adjusted odds ratio; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CI, confidence interval; CSHCN, children with special health care needs; DD, developmental delay; ID, intellectual disability; SE, standard error.

After using a backwards stepwise elimination procedure the following covariates were adjusted for given their statistically significant partial coefficients at the P < .10 level: child age (years), household income level, health insurance type and region of residence.

Partial coefficent p-values <0.001 for all provider responses in both adjusted and unadjusted models.

Conversely, reassuring/passive provider responses were associated with ≥ 1 year increases in delay between first provider conversation and ASD diagnosis. In addition, having 2 or 3 resassuring/passive responses was associated with longer ASD diagnostic delays than was having only 1 reassuring/passive response. Likewise, the odds of having a ≥ 3 year diagnostic delay increased with each reassuring/passive response type, and having all three reassuring/passive responses was associated with the highest odds of this delay (Table IV).

Discussion

In this nationally-representative sample of children with ASD, we found that despite early parental concerns, ASD diagnosis was delayed by nearly 3 years after a parent’s first conversation with a provider. Additionally, despite evidence suggesting that parent concerns strongly predict child developmental risk both overall and for ASD in particular,(43–45) more than half of children with either ASD or ID/DD had passive/reassuring provider responses to their parents’ concerns. Finally, among children with ASD, diagnostic delays were longer when the child’s provider had a reassuring/passive response to parents’ early developmental concerns.

Although literature suggests that early signs ASD may be difficult for parents to detect,(5) this analysis shows that parents of children with ASD reported earlier concerns than parents of children with ID/DD, had earlier provider conversations about these concerns, but were more likely than children with ID/DD to have reassuring/passive provider responses to parents’ concerns. This finding suggests that the particular presenting characteristics of ASD may predispose affected children to longer diagnostic delays. Because the longest delay between initial parent concerns and ASD diagnosis occurred after the first provider conversation about parent concerns, the health care system in general and health care providers specifically may play a substantial role in these delays.

Providers may have different reasons for not acting on parents’ developmental concerns: they may not elicit these concerns in the first place,(22,23) or they may underestimate the importance of concerns parents raise (46). Providers may also share parents’ concerns but lack screening, referral, or diagnostic resources overall, or may experience significant delays in attempting to access such resources (28). Although children with ASD were younger than those with ID/DD at initial concern, analyses controlled for age, so differential provider response cannot solely be explained by age differences. However, children with ASD versus ID/DD may have differed in content of parental concern or in provider observations of the child. For instance, some ID/DD-related conditions are apparent at or before birth, allowing providers and parents to enter into early conversations with more information.

A strength of this study is its large, nationally-representative sample. The study has several limitations. Because the survey assessed children age 6–17, events may have occurred more than 10 years prior, may be subject to recall bias, and may not reflect current practice. Although parents are generally valid reporters of children’s health care quality and experiences,(47,48) some outcomes may reflect parents’ feelings about their child’s health care quality overall rather than specific actions the provider took or failed to take in response to their concerns. Because all ID, DD, and ASD diagnoses were parent-reported, there is no way to assess their validity. Because data were cross-sectional, they do not show a causal relationship between parent concerns, provider response, and diagnostic delays.

Due to limitations in age reporting in the Pathways Survey (age was recorded in months up to 36 months but in years thereafter), we calculated age in years only. This was the only way to treat age data consistently, which seemed important because mean age of ASD diagnosis was >36 months, and many of the diagnostic intervals we studied spanned the 36-month age time-point. Even if age in months had been available for the full age span, it likely would have been unreliable, because many parents of the school-age children in this survey might have had trouble recollecting the exact month of events among children older than three. We recognize that calculating age in years limits precision of outcomes in this study, and additionally recognize that there was no way to separate parents who experienced no diagnostic delay from parents who experienced very short delays.

Because the study aimed to assess children who ultimately developed chronic conditions, children who did not qualify as CSHCN were not assessed, and children with past but not current ID, DD, or ASD were excluded. ID and DD were analyzed jointly because the conditions present similarly in early childhood, and because the survey contained only 46 children with ID and not DD. Because children with ID or ID/DD likely had more severe symptoms than DD alone, grouping ID with DD likely biased findings about age of concerns earlier, or more similar to ASD, suggesting that findings may underestimate differences. We did not analyze ID/DD diagnosis, because we judged ID/DD-related conditions to be quite heterogeneous in age of presentation. Finally, the sample consisted of parents responding to both NS-CSHCN and Pathways survey and may be subject to non-response bias from either survey.(33)

Despite these limitations, these data imply that providers’ responses to parents’ early concerns may be an important contributor to diagnostic delays in ASD, and that children with ASD may be at particular risk of having a reassuring or passive response when compared with other children with developmental delays. As a result, providers may need greater education about validity of early parent developmental concerns in ASD. Payors and policymakers may need to make the next proactive steps more apparent to providers and easier to take. Care coordination in the primary care setting may be particularly important for enabling access to diagnostic and therapeutic services. Programs such as Healthy Steps,(49) or the Help Me Grow initiative,(50) which link primary care with community resources, may help providers better identify and refer at-risk children. Incentivizing developmental screening through enhanced payment(51) or requiring it through policy mandate,(52) have also been shown to improve screening rates and developmental referrals. Finally, because many children may not be able to access ASD diagnostic services via health care providers, routine developmental evaluation and referral in community(53) or early education settings may be beneficial.

In conclusion, despite early parent concerns, children with ASD have less proactive provider responses to their concerns than children with ID/DD. Less proactive/more passive provider responses are associated with diagnostic delays in ASD. These findings highlight the need for stakeholders and policyholders to provide more support to front-line health care providers, so that children with ASD receive early access to evidence-based care.

Acknowledgments

Funded by the Medical Research Foundation of Oregon. K.Z. was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (1K23MH095828).

We acknowledge Benjamin Zablotsky, PhD at the Centers for Disease Control for his helpful review of initial findings and drafts of this manuscript. We also acknowledge Julie Robertson, MSW MPH and Christina Bethell, PhD MBA MPH at the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative for their assistance with study design and statistical analysis.

Abbreviations

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- ASD

autism spectrum disorder

- CSHCN

children with special health care needs

- DD

developmental delay

- ID

intellectual disability

- NS-CSHCN

National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2010 Principal Investigators. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014 Mar 28;63( Suppl 2):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumberg SJ, Bramlett MD, Kogan M, Schieve LA, Jones JR, Lu MC. Changes in parent-reported prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in school-aged U.S. children: 2007 to 2011–12. 2013. Nat Health Stat Rep. 2013;65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012 Mar 30;61:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson CP, Myers SM American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children with Disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007 Nov;120:1183–1215. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Committee on Children With Disabilities. Technical report: the pediatrician’s role in the diagnosis and management of autistic spectrum disorder in children. Pediatrics. 2001 May;107:E85. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.5.e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landa RJ, Kalb LG. Long-term outcomes of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders exposed to short-term intervention. Pediatrics. 2012 Nov;130( Suppl 2):S186–90. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0900Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace KS, Rogers SJ. Intervening in infancy: implications for autism spectrum disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010 Dec;51:1300–1320. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers SJ, Estes A, Lord C, Vismara L, Winter J, Fitzpatrick A, et al. Effects of a brief Early Start Denver model (ESDM)-based parent intervention on toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012 Oct;51:1052–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kogan MD, Strickland BB, Blumberg SJ, Singh GK, Perrin JM, van Dyck PC. A national profile of the health care experiences and family impact of autism spectrum disorder among children in the United States, 2005–2006. Pediatrics. 2008 Dec;122:e1149–58. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson JW, Mulick JA. System and cost research issues in treatments for people with autistic disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000 Dec;30:585–593. doi: 10.1023/a:1005691411255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buescher AV, Cidav Z, Knapp M, Mandell DS. Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2014 Aug 1;168:721–728. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peacock G, Amendah D, Ouyang L, Grosse SD. Autism spectrum disorders and health care expenditures: the effects of co-occurring conditions. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012 Jan;33:2–8. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31823969de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandell DS, Morales KH, Xie M, Lawer LJ, Stahmer AC, Marcus SC. Age of diagnosis among Medicaid-enrolled children with autism, 2001–2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2010 Aug;61(8):822–829. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.8.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandell DS, Novak MM, Zubritsky CD. Factors associated with age of diagnosis among children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2005 Dec;116:1480–1486. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinto-Martin J, Levy SE. Early diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2004 Sep;6:391–400. doi: 10.1007/s11940-996-0030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bethell C, Reuland C, Schor E, Abrahms M, Halfon N. Rates of parent-centered developmental screening: disparities and links to services access. Pediatrics. 2011 Jul;128:146–155. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandell DS, Wiggins LD, Carpenter LA, Daniels J, DiGuiseppi C, Durkin MS, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in the identification of children with autism spectrum disorders. Am J Public Health. 2009 Mar;99:493–498. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandell DS, Listerud J, Levy SE, Pinto-Martin JA. Race differences in the age at diagnosis among Medicaid-eligible children with autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002 Dec;41:1447–1453. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200212000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiggins LD, Baio J, Rice C. Examination of the time between first evaluation and first autism spectrum diagnosis in a population-based sample. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006 Apr;27:S79–87. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200604002-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daniels AM, Mandell DS. Explaining differences in age at autism spectrum disorder diagnosis: A critical review. Autism. 2013 Jun 20;18:583–597. doi: 10.1177/1362361313480277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuckerman KE, Boudreau AA, Lipstein EA, Kuhlthau KA, Perrin JM. Household language, parent developmental concerns, and child risk for developmental disorder. Acad Pediatr. 2009 Mar-Apr;9:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guerrero AD, Rodriguez MA, Flores G. Disparities in provider elicitation of parents’ developmental concerns for US children. Pediatrics. 2011 Nov;128:901–909. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Council on Children With Disabilities, Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Bright Futures Steering Committee, Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the Medical Home: An algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006 Jul 1;118:405–420. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radecki L, Sand-Loud N, O’Connor KG, Sharp S, Olson LM. Trends in the use of standardized tools for developmental screening in early childhood: 2002–2009. Pediatrics. 2011 Jul 01;128:14–19. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guerrero AD, Garro N, Chang JT, Kuo AA. An update on assessing development in the pediatric office: has anything changed after two policy statements? Acad Pediatr. 2010 Nov-Dec;10:400–404. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daniels AM, Mandell DS. Children’s compliance with American Academy of Pediatrics’ well-child care visit guidelines and the early detection of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013 Dec;43:2844–2854. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1831-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuckerman KE, Mattox K, Baghaee A, Batbayar O, Donelan K, Bethell C. Pediatrician identification of Latino children at risk for autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2013;132:445–453. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howlin P, Asgharian A. The diagnosis of autism and Asperger syndrome: findings from a survey of 770 families. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999 Dec;41:834–839. doi: 10.1017/s0012162299001656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. [Accessed November 20, 2014];Exploring Health Conditions in the 2009/10 NS-CSHCN. Available at: Exploring Health Conditions in the 2009/10 NS-CSHCN. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bethell CD, Read D, Stein RE, Blumberg SJ, Wells N, Newacheck PW. Identifying children with special health care needs: development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambul Pediatr. 2002 Jan-Feb;2:38–48. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0038:icwshc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed November 20, 2014];Survey of Pathways to Diagnosis and Services. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/spds.htm.

- 33.National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed November 20, 2014];2009–10 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/slaits/NS_CSHCN_Questionnaire_09_10.pdf.

- 34.Autism Services, Education, Resources and Training Collaborative (ASERT) [Accessed November 20, 2014];Pennsylvania Autism Needs Assessment: A Survey of Individuals and Families Living with Autism. Available at: http://www.paautism.org/resources/CaregiversorParents/ResourceDetails/tabid/142/language/en-US/Default.aspx?itemid=280.

- 35.Gadow KD, Devincent C, Schneider J. Predictors of psychiatric symptoms in children with an autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008 Oct;38:1710–1720. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0556-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montes G, Halterman JS. White-black disparities in family-centered care among children with autism in the United States: evidence from the NS-CSHCN 2005–2006. Acad Pediatr. 2011 Jul-Aug;11:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.King MD, Bearman PS. Socioeconomic status and the increased prevalence of autism in California. Am Sociol Rev. 2011 Apr 1;76:320–346. doi: 10.1177/0003122411399389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fountain C, King MD, Bearman PS. Age of diagnosis for autism: individual and community factors across 10 birth cohorts. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011 Jun;65:503–510. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.104588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knapp C, Woodworth L, Fernandez-Baca D, Baron-Lee J, Thompson L, Hinojosa M. Factors associated with a patient-centered medical home among children with behavioral health conditions. Matern Child Health J. 2012 Oct 30; doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008 Aug;47:921–929. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed November 20, 2014];Frequently asked questions: 2011 Survey of Pathways to Diagnosis and Services. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/slaits/PathwaysFAQ.pdf.

- 42.Long JS. Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glascoe FP. Parents’ evaluation of developmental status: how well do parents’ concerns identify children with behavioral and emotional problems? Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2003 Mar;42:133–138. doi: 10.1177/000992280304200206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ozonoff S, Young GS, Steinfeld MB, Hill MM, Cook I, Hutman T, et al. How early do parent concerns predict later autism diagnosis? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009 Oct;30:367–375. doi: 10.1097/dbp.0b013e3181ba0fcf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glascoe FP, Macias MM, Wegner LM, Robertshaw NS. Can a broadband developmental-behavioral screening test identify children likely to have autism spectrum disorder? Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2007 Nov;46:801–805. doi: 10.1177/0009922807303928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bailey DB, Raspa M, Bishop E, Holiday D. No change in the age of diagnosis for fragile X syndrome: Findings from a national parent survey. Pediatrics. 2009 Aug 01;124:527–533. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garwick AW, Kohrman C, Wolman C, Blum RW. Families’ recommendations for improving services for children with chronic conditions. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998 May 1;152:440–448. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.5.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Homer CJ, Marino B, Cleary PD, Alpert HR, Smith B, Crowley Ganser CM, et al. Quality of care at a children’s hospital: The parents’ perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999 Nov 1;153:1123–1129. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.11.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guyer B, Hughart N, Strobino D, Jones A, Scharfstein D. Assessing the impact of pediatric-based development services on infants, families, and clinicians: challenges to evaluating the Health Steps Program. Pediatrics. 2000 Mar;105:E33. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Children’s Trust Fund. [Accessed November 20, 2014];Help Me Grow. Available at: http://www.ct.gov/ctf/cwp/view.asp?a=1786&q=296676.

- 51.Wegner LM, Macias MM. Services for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: payment issues. Pediatr Ann. 2009 Jan;38:57–61. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20090101-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuhlthau K, Jellinek M, White G, Vancleave J, Simons J, Murphy M. Increases in behavioral health screening in pediatric care for Massachusetts Medicaid patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011 Jul;165:660–664. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roux AM, Herrera P, Wold CM, Dunkle MC, Glascoe FP, Shattuck PT. Developmental and autism screening through 2-1-1: reaching underserved families. Am J Prev Med. 2012 Dec;43:S457–63. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]