Abstract

Marine invertebrates including sponges, soft coral, tunicates, mollusks and bryozoan have proved to be a prolific source of bioactive natural products. Among marine-derived metabolites, terpenoids have provided a vast array of molecular architectures. These isoprenoid-derived metabolites also exhibit highly specialized biological activities ranging from nerve regeneration to blood-sugar regulation. As a result, intense research activity has been devoted to characterizing invertebrate terpenes from both a chemical and biological standpoint. This review focuses on the chemistry and biology of terpene metabolites isolated from the Red Sea ecosystem, a unique marine biome with one of the highest levels of biodiversity and specifically rich in invertebrate species.

Keywords: terpenes, Red Sea, marine ecosystem, marine invertebrates, biomedical leads

1. Red Sea Ecosystem

Marine ecosystems cover nearly 70% of the earth’s surface, averaging almost 4 km in depth and are proposed to contain over 80% of the world’s plant and animal species [1]. Exact marine biodiversity is less certain since between one-third and two-thirds of marine organisms have yet to be described [2]. Worldwide there are approximately 226,000 marine eukaryotes currently reported, while close to a million total species are estimated, based on calculations by marine biologists using statistical predictions [2]. Considering that constituents from higher plants along with metabolites from terrestrial microorganisms have provided a substantial fraction of the natural-product-derived drugs currently used in Western medicine [3], the potential to vastly expand the number and diversity of natural products by mining marine eukaryotes as well as associated prokaryotes from the richly diverse Red Sea ecosystem seems attainable. In fact, just within the past quarter century, the search for new marine metabolites has resulted in the isolation of upward of 10,000 compounds [4], many of which exhibit biological activity. Despite the fact that marine biodiversity far exceeds that of terrestrial ecosystems, research of marine natural products as pharmaceutical agents, is still in its infancy. Factors that contribute to the gap between terrestrial and marine derived natural products include a paucity of ethno-medical history from marine sources as well as impediments associated with collecting, identifying and chemical analysis of marine materials [5].

Notwithstanding, a combination of new diving techniques and implementation of remotely operated pods over the last decade has facilitated the characterization of marine-derived metabolites. This review encompasses secondary metabolites derived from marine invertebrates, a largely diverse group of fixed or sessile organisms, many in a stationary form although some are capable of slow primitive movement. While invertebrates lack physical defences such as a protective shell or spines, they are often rich in defence metabolites that can be utilized to attack prey or defend a habitat.

This review focused on a class of secondary defence metabolites abundant in marine invertebrates, five-carbon isoprenoid-derived terpenes. Extensive speciation from microorganisms to mammals can be attributed, at least in part to a wide range of temperatures (0 to 35 °C in arctic waters versus hydrothermal vents, respectively), pressures (1–1000 atm.), nutrient availabilities (oligotrophic to eutrophic) and lighting conditions that exist in this marine biome [6]. The analysis will be limited to the Red Sea which is considered an epicenter for marine biodiversity with an extremely high endemic biota including over 50 genera of hermatypic coral. Indeed soft coral (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Octocorallia), which are an important structural component of coral reef communities [7,8], are approximately 40% native to the Red Sea [6]. The Red Sea, in which extensive reef formation occurs, is arguably the world’s warmest (up to 35 °C in summer) and most saline habitat (ca. 40 psu in the northern Red Sea) [6]. Despite the Red Sea’s size and diversity of reef-associated inhabitants (for examples, see Figure 1), marine invertebrates in this ecosystem remain poorly studied compared to other large coral reef systems around the world such as the Great Barrier Reef or the Caribbean. This review will cover terpenes isolated from marine invertebrates of the Red Sea (Figure 2) as well as identified biological activities for compounds reported during the time period from 1980 to 2014.

Figure 1.

Samples of marine invertebrate diversity from the Red Sea including (from left to right starting at the top left corner) Sarcophyton glaucum, S. regulare, S. ehrenbergi, Nephthea molle, Acropora humilis, Porites solida, Pocillopora verrucosa, Clothraria rubrinoidis and Cystoseira trinode. Marine species exhibit greater phyta diversity than land species.

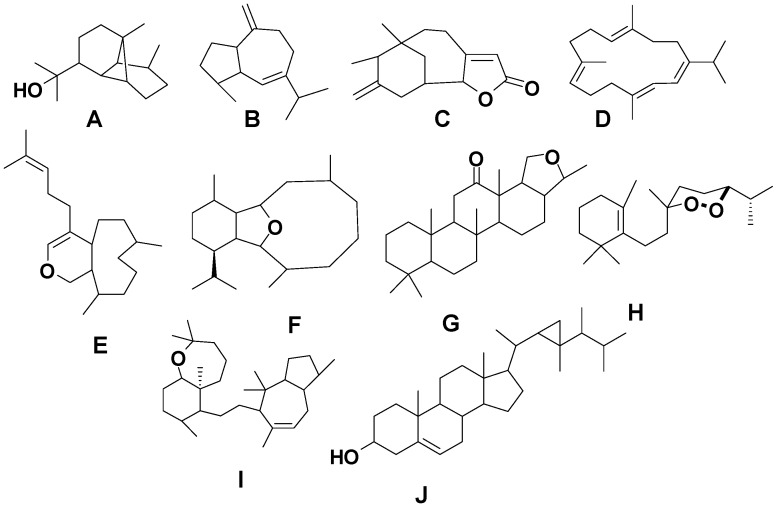

Figure 2.

Terpene skeletal types including ylangene (A), aromadendrane (B), tricycle-[6,7,5]-sesquiterpene (C), cembrane (D), xeniolide and xeniaphyllane (E), eunicellin diterpene (F), sesterterpene (G), norsesterterpene (H), triterpene (I) and steroid (J) types.

2. Sesquiterpenes

Sesquiterpenes are secondary metabolites present in many marine organisms including soft coral (e.g., Dendronephthya sp., Sinularia gardineri, Litophyton arboreum, Sarcophyton trocheliophorum, S. glaucum and Parerythropodium fulvum fulvum) [9,10,11,12,13,14], and sponges (e.g., Hyrtios sp. and Diacarnus erythraenus) [15,16].

2.1. Ylangene-Type Sesquiterpenes

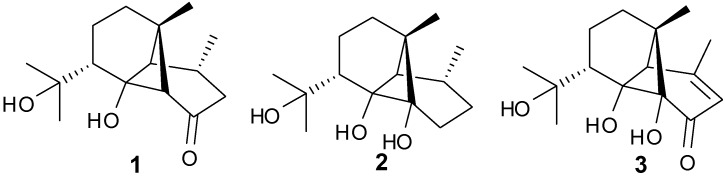

Tricyclo-[4,6,6]-sesquiterpenes, Dendronephthol A–C (1–3) have been isolated from the soft coral Dendronephthya, family Nephtheidae (Figure 3). Cytotoxic activity was observed for 1 and 3 against the murine lymphoma L5187Y cancer cell line with ED50 values of 8.4 and 6.8 μg/mL, respectively [9].

Figure 3.

Representative structures of ylangene-type sesquiterpenes (1–3).

2.2. Aromadendrane-Type Sesquiterpenes

Bicyclico [5,7] sesquiterpenes have been isolated from several different coral with examples shown in Table 1 and Figure 4. Cytotoxicity to murine leukemia (P-388), human lung carcinoma (A-549), human colon carcinoma (HT-29), and human melanoma cells (MEL-28) [11] was observed with exposure to 4. Inhibitory activity against HIV-1 protease (PR) at an IC50 of 7 μM was observed for 5. Compounds 5 and 8 demonstrated cytostatic action with assaying HeLa cells, revealing potential use in virostatic cocktails [11]. Antitumor activity against lymphoma and Ehrlich cell lines was observed for 9 with LD50 in the range of 2.5–3.8 μM; antibacterial and antifungal activities were also observed [12]. Compound 10 showed potent activity against the prostate cancer line PC-3 with an IC50 of 9.3 ± 0.2 μM. Anti-proliferative activity of 9 can be attributed, at least in part, to its ability to induce cellular apoptosis [13]. Compound 12 exhibited a promising IC50 > 1 μg/mL against three cancer cell lines including murine leukemia (P-388; ATCC: CCL-46), human lung carcinoma (A-549; ATCC: CCL-8) and human colon carcinoma (HT-29; ATCC: HTB-38) [15].

Table 1.

Aromadendrane sesquiterpenes, sources and activities.

| No. | Name | Sources | Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Guaianediol [10] | Sinularia gardineri | anti-tumor |

| 5 | Alismol [11] | Litophyton arboreum | cytostatic |

| 6 | Lactiflorenol [17] | Sinularia polydactyla | |

| 7 | 10-O-Methyl alismoxide [11] | L. arboreum | |

| 8 | Alismoxide [11] | L. arboreum | cytostatic |

| 9 | Palustrol [12] | Sarcophyton trocheliophorum | anti-tumor, antibacterial and antifungal |

| 10 | 10(14)-Aromadendrene [13] | Sarcophyton glaucum | anti-tumor, antiproliferative |

| 11 | Fulfulvene [14] | Parerythropodium fulvum fulvum | |

| 12 | O-Methyl guaianediol [15] | Diacarnus erythraenus | cytotoxic |

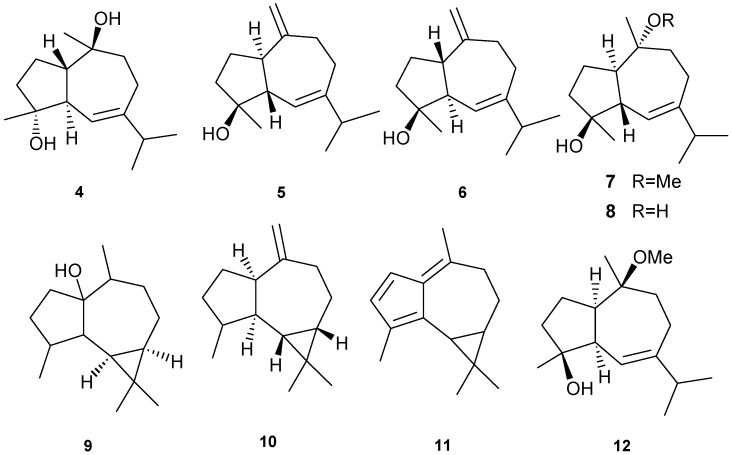

Figure 4.

Representative structures of aromadendrane-type sesquiterpenes (4–12).

2.3. γ-Methoxybutenolide-Type Sesquiterpenes

Tricyclo-[6,7,5]-sesquiterpenes, Hyrtiosenolide A and B have been isolated from the sponge Hyrtios sp., and compounds 13 and 14 exhibit weak antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli [16] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Structures of sesquiterpenes-γ-methoxybutenolides and sesquiterpene derivatives (13–28).

2.4. Miscellaneous Sesquiterpenes

Additional sesquiterpenes have been isolated from several coral genera with examples reported in Table 2 and Figure 5. Compound 28 exhibits cytotoxic activity against human hepatocarcinoma (HepG2) and breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7) [17].

Table 2.

Other sesquiterpenes, sources and activities.

| No. | Name | Sources | Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 5-Hydroxy-8-methoxy-calamenene [14] | Parerythropodium fulvum fulvum | |

| 16 | 5-Hydroxy-8-methoxy-calamenene-6-al [14] | Parerythropodium fulvum fulvum | |

| 17 | Peyssonol A [17] | Peyssonnelia sp. | |

| 18 | Ilimaquinone [18] | Smenospongia sp. | |

| 19 | Avarol [18,19] | Dysidea cinerea | HIV |

| 20 | 3′-Hydroxyavarone [20] | D.cinerea | |

| 21 | 3′,6′-Dihydroxyavarone [20] | D.cinerea | |

| 22 | 6′-Acetoxyavarone [20] | D.cinerea | |

| 23 | 6′- Hydroxy4′-methoxyavarone [20] | D.cinerea | |

| 24 | 6′-Hydroxyavarol [20] | D.cinerea | |

| 25 | 6′-Acetoxyavarol [20] | D.cinerea | |

| 26 | Smenotronic acid [18] | Smenospongia sp. | |

| 27 | Dactyltronic acids [18] | Smenospongia sp. | |

| 28 | (E)-Methyl-3-(5-butyl-1-hydroxy-2,3-dimethyl-4-oxocyclopent-2-enyl)acrylate [21] | Sarcophyton ehrenbergi | cytotoxic (HepG2) (anti-tumor) |

3. Diterpenes

Diterpenoids are widespread in various marine organisms including soft coral (Sarcophyton glaucum, S. trocheliophorum, Sinularia polydactyla, S. gardineri, Litophyton arboreum, Lobophyton sp., Xenia sp. and Cladiella pachyclados) [10,11,12,13,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], and sponges (Leucetta chagosensis) [23].

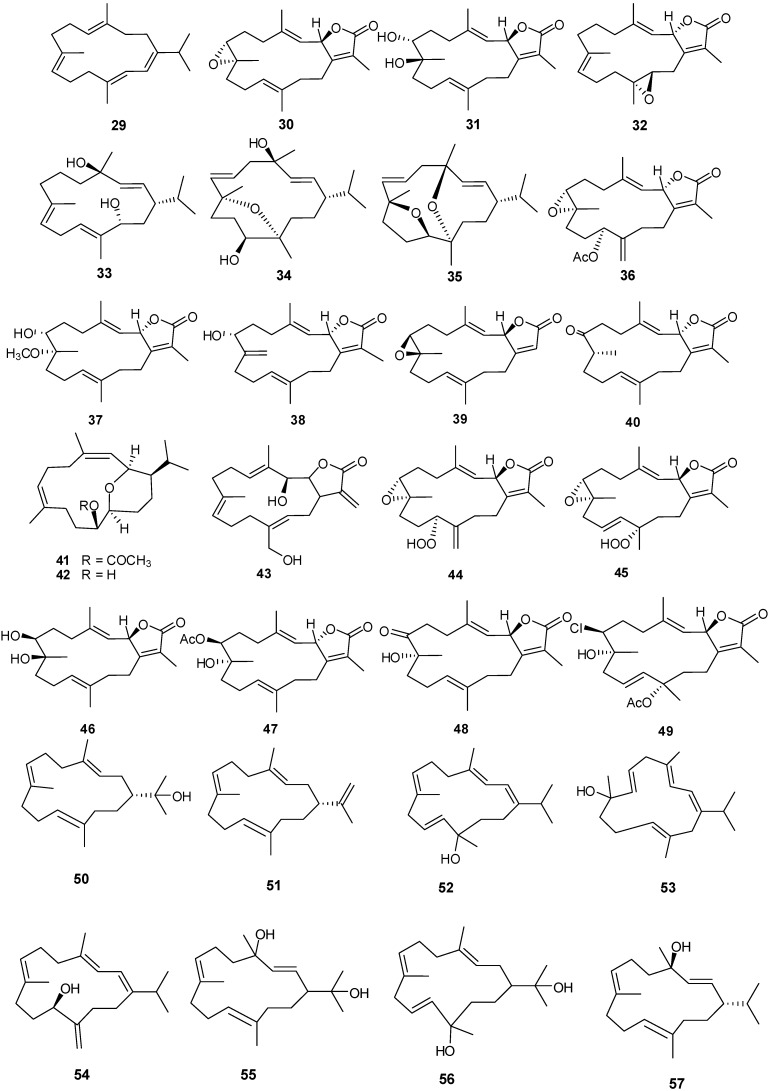

3.1. Cembrane-Based Diterpenes

Fourteen-membered cyclic and bicycle-[5,14]-diterpenes have been isolated from numerous coral genera with examples shown in Table 3 and Figure 6. Compounds 29, 41 and 42 exhibited antibacterial and antifungal activity against Aspergillus flavus and Candida albicans with low μM MIC values [12]. Lack of cytotoxicity against monkey kidney CV-1 cells suggests that 30, 32, and 33 may prove to be good candidate drugs against melanoma and warrant further studies in the development as antitumor agents [19]. Compound 30 exhibits moderate antifungal activity against Cryptococcus neoformans with an IC50 of 20 μg/mL [22]. Compound 43 showed selective cytotoxicity against HepG2 (IC50 1.0 μg/mL) [24]. Compounds 44 and 45 were found to be inhibitors of cytochrome P450 1A activity [25]. Compound 47 exhibits cytotoxic activity against HepG2, HCT-116, and HeLa cells with low IC50 μg/mL values [26]. Cytotoxic activity against human hepatocarcinoma (HepG2) and breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7) cell lines was observed for 48 and 49 [21].

Table 3.

Cembrane diterpenes, sources and activities.

| No. | Name | Source | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 29 | Cembrene-C [12] | Sarcophyton trocheliophorum | anti-fungal, anti-bacterial |

| 30 | Sarcophine [19,22] | S. glaucum | anti-tumor, antifungal |

| 31 | (+)-7α,8β-Dihydroxydeepoxy-sarcophine [22] | S. glaucum | |

| 32 | Sarcophytolide 1 [19,30] | S. glaucum | anti-tumor |

| 33 | (1S,2E,4R,7E,11E,13S)-Cembratrien-4,13-diol [22] | S. glaucum | anti-tumor |

| 34 | (1S,2E,4R,6E,8R,11S,12R)-8,12-Epoxy-2,6-cembradiene-4,11-diol [22] | S. glaucum | anti-tumor |

| 35 | (1S,2E,4R,6E,8S,11R,12S)-8,11-Epoxy-4,12-epoxy-2,6-cembradiene [22] | S. glaucum | anti-tumor |

| 36 | Trochelioid A [23] | S. trocheliophorum | |

| 37 | Trochelioid B [23] | S. trocheliophorum | |

| 38 | 16-Oxosarcophytonin E [23] | S. trocheliophorum | |

| 39 | ent-Sarcophine [23] | S. trocheliophorum | |

| 40 | 8-epi-Sarcophinone [23] | S. trocheliophorum | |

| 41 | Sarcotrocheliol acetate [12] | S. trocheliophorum | anti-tumor |

| 42 | Sarcotrocheliol [12] | S. trocheliophorum | anti-tumor |

| 43 | Durumolide C [24] | Sinularia polydactyla | anti-fungal, anti-bacterial |

| 44 | 11(S)-Hydroperoxylsarcoph-12(20)-ene [22] | S. glaucum | anti-fungal, anti-bacterial |

| 45 | 12(S)-Hydroperoxylsarcoph-10-ene [25] | S. glaucum | cytotoxic HepG2 (anti-tumor) |

| 46 | (2R,7R,8R)-Dihydroxy-deepoxysarcophine [26] | S. glaucum | anti-tumor |

| 47 | 7β-Acetoxy-8α-hydroxy-deepoxysarcophine [26] | S. glaucum | cytotoxic (HepG2)( anti-tumor) |

| 48 | 7-Keto-8α-hydroxy-deepoxysarcophine [21] | S. ehrenbergi | cytotoxic (HepG2) (anti-tumor) |

| 49 | 7β-Chloro-8α-hydroxy-12-acetoxy-deepoxysarcophine [21] | S. ehrenbergi | cytotoxic (HepG2) (anti-tumor) |

| 50 | Nephthenol [27] | Lobophytum pauciflorum | |

| 51 | Cembrene-A [27] | Alcyonium utinomii | |

| 52 | Alcyonol A [27] | A. utinomii | |

| 53 | Alcyonol B [27] | A. utinomii | |

| 54 | Alcyonol C [27] | A. utinomii | |

| 55 | Pauciflorol A [27] | L. pauciflorum | |

| 56 | Pauciflorol B [27] | L. pauciflorum | |

| 57 | Thunbergol [27] | L. pauciflorum | |

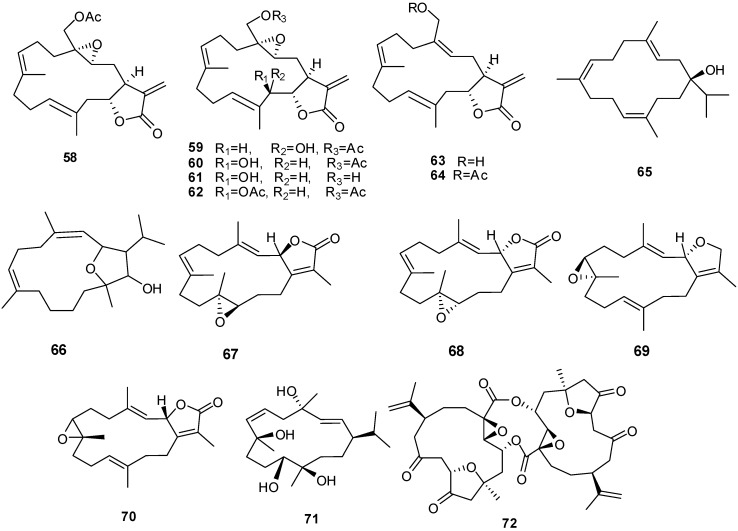

| 58 | Labolide [27] | L. crassum | |

| 59 | 20-Acetylsinularolide B [27] | L. crassum | |

| 60 | 20-Acetylsinularolide C [27] | L. crassum | |

| 61 | Sinularolide C [27] | L. crassum | |

| 62 | Sinularolide C diacetate [27] | L. crassum | |

| 63 | 3-Deoxypresinularolide B [27] | L. crassum | |

| 64 | 3-Deoxy-20-acetylpresinularolide B [27] | L. crassum | |

| 65 | Sarcophytol M [11] | Litophyton arboreum | |

| 66 | Sarcophytolol [13] | Sarcophyton glaucum | cytotoxic HepG2 (anti-tumor) antiproliferative |

| 67 | Sarcophytolide B [13] | S. glaucum | |

| 68 | Sarcophytolide C [13] | S. glaucum | |

| 69 | Deoxosarcophine [13] | S. glaucum | cytotoxic against MCF-7 (anti-tumor) |

| 70 | 2-epi-Sarcophine [31] | S. auritum | cytotoxic |

| 71 | (1R,2E,4S,6E,8R,11R,12R)-2,6-cembradiene-4,8,11,12-tetrol [31] | S. auritum | cytotoxic |

| 72 | Singardin [31] | Sinularia gardineri | anti-tumor |

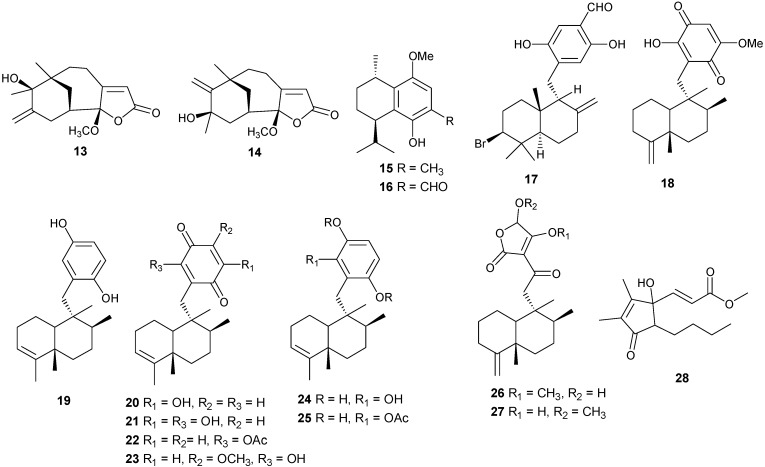

Figure 6.

Structures of cembrane-based diterpenes (29–72).

Compounds 66 and 68 have significant cytotoxic activity against the human hepatocellular liver carcinoma cell line HepG2 with an IC50 of 20 μM while 67 and 68 show activity against the human breast adenocarcinoma cell line MCF-7, also with an IC50 in the low μM range. The anti-proliferative activity of 66 and 68 can be attributed, at least in part, to observed cellular apoptosis activity [13,30]. Compound 70 exhibits cytotoxicity to a variety of cell lines including murine leukemia (P-388), human lung carcinoma (A-549), human colon carcinoma (HT-29) and human melanoma (MEL-28) [31].

3.2. Xenicane Diterpenes

Bicyclo-[6,9]/[4,9]-diterpenes have been isolated from the coral genus Xenia with examples shown in Table 4 and Figure 7.

Table 4.

Xenia diterpenes, sources and activities.

| No. | Name | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 73 | Xenicin [28] | Xenia macrosoiculata |

| 74 | Xenialactol-D [28] | X. obscuronata |

| 75 | Xenialactol-C [28] | X. obscuronata |

| 76 | Xeniolide-E [28] | X. obscuronata |

| 77 | 14(15)-Epoxyxeniaphyllene [28] | X. lilielae |

| 78 | Xeniaphyllene-dioxide [28] | X. lilielae |

| 79 | Xeniaphyllenol-C [28] | X. macrosoiculata |

| 80 | Epoxyxeniaphyllenol-A [28] | X. lilielae, X. macrosoiculata |

| 81 | l4,15-Xeniaphyllandiol-4,5-epoxide [28] | X. macrosoiculata |

| 82 | Xeniaphyllenol-B [28] | X. macrosoiculata |

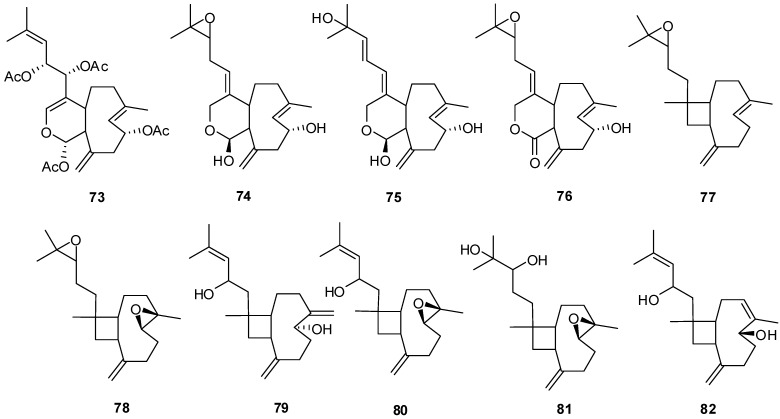

Figure 7.

The structures of Xenicane diterpenes (73–82).

3.3. Eunicellin-Based Diterpenes

Tricyclo-[6,5,10]-diterpenes have been isolated from the soft coral genus Cladiella with examples shown in Table 5 and Figure 8. Eunicellin-based diterpenes display a wide range of bioactivities including anti-inflammatory and antitumor activities [26]. Compounds 83–104 have been evaluated for activity to inhibit growth, proliferation, invasion and migration of a prostate cancer cell line with potent anti-migratory and anti-invasive activities observed. Compounds with exomethylene functionalities at C-7 and C-11 demonstrate low anti-migratory activity, however replacement of the exomethylene moiety at C-7 with a quaternary oxygenated carbon, appreciatively increases the activity, as observed for compounds 93–94 and 96 [29].

Table 5.

Eunicellin diterpenoids, sources and activities.

| No. | Name | Source | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 83 | Pachycladin A [29] | Cladiella pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 84 | Klysimplexin G [29] | C. pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 85 | Pachycladin B [29] | C. pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 86 | Klysimplexin E [29] | C. pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 87 | Pachycladin C [29] | C. pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 88 | Cladiellisin [29] | C. pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 89 | 3-Acetyl cladiellisin [29] | C. pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 90 | 3,6-Diacetyl cladiellisin [29] | C. pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 91 | Pachycladin D [29] | C. pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 92 | Pachycladin E [26] | C. pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 93 | Sclerophytin A [29] | C. pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 94 | Sclerophytin F methyl ether [29] | C. pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 95 | Sclerophytin B [29] | C. pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 96 | (+)-Polyanthelin A [29] | C. pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 97 | Cladiella-6Z,11(17)-dien-3-ol [29] | C. pachyclados | anti-tumor, anti-invasive |

| 98 | Briarein A [32] | Junceella juncea | |

| 99 | Juncins A [32] | J. juncea | |

| 100 | Juncins B [32] | J. juncea | |

| 101 | Juncins C [32] | J. juncea | |

| 102 | Juncins D [32] | J. juncea | |

| 103 | Juncins E [32] | J. juncea | |

| 104 | Juncins [32] | J. juncea |

Figure 8.

The structure of eunicellin-type diterpenes (83–104).

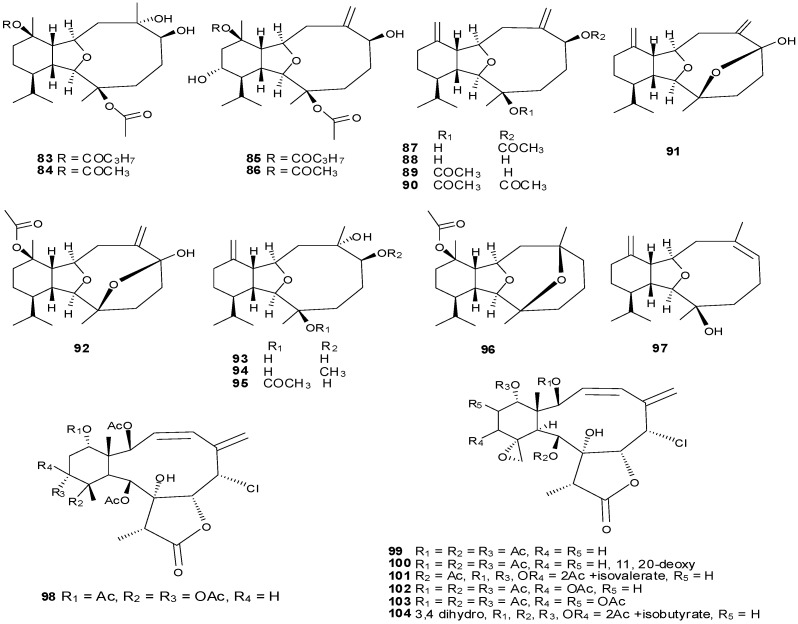

3.4. Miscellaneous Diterpenes

Miscellaneous diterpenes were isolated from three different genus Xenia, Chelonaplysilla and Dysidea. These compounds were classified as: prenylated germacrenes (105), bicyclic diterpenes (108, 109), clerodane diterpenes (107), carbo-tricyclic diterpenes (108) and re-arranged spongian diterpenes (110–113) as shown in Table 6 and Figure 9.

Table 6.

Macrocyclic diterpenes, sources and activities.

| No. | Name | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 105 | Obscuronatin [28] | Xenia obscuronata |

| 106 | Biflora-4,10(19),15-triene [28,33] | X. obscuronata |

| 107 | Chelodane [34] | Chelonaplysilla erecta |

| 108 | Barekoxide [34] | C. erecta |

| 109 | Zaatirin [34] | C. erecta |

| 110 | Norrisolide [35] | Dysidea sp. |

| 111 | Norrlandin [35] | Dysidea sp. |

| 112 | Seco-norrlandin B [35] | Dysidea sp. |

| 113 | Seco-norrlandin C [35] | Dysidea sp. |

Figure 9.

The structure of the macrocyclic type diterpenes (105–113).

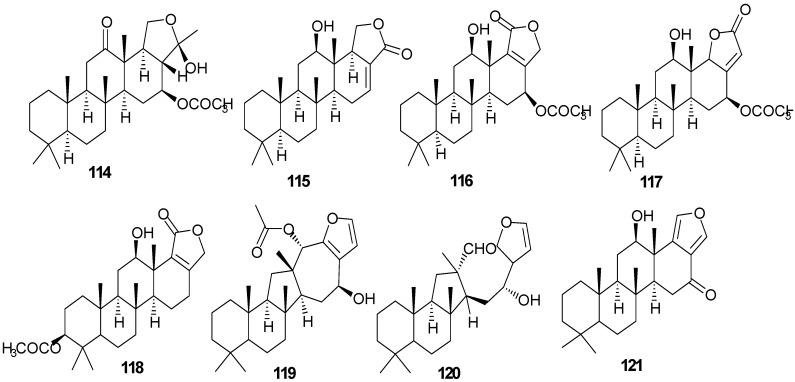

4. Sesterterpenes and Norsesterterpenes

4.1. Sesterterpenes

Pentacyclo-[6,6,6,6,5]-sesterterpenes have been isolated from two different sponges with examples shown in Table 7 and Figure 10. Compound 116 exhibits antimycobacterial inhibition against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (H37Rv) at a concentration of 6 μg/mL while 117–119 displayed moderate to weak inhibitory activity [36]. Compounds 122–123 showed significant cytotoxicity against murine leukemia (P-388), human lung carcinoma (A-549) and a human colon carcinoma (HT-29) [37].

Table 7.

Sesterterpenes, sources and activities.

| No. | Name | Source | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 114 | Scalardysin [18] | Dysidea herbacea | |

| 115 | 25-Dehydroxy-12- epi-deacetylscalarin [36] | Hyrtios erecta | antimycobacterial |

| 116 | Sesterstatin [36] | H. erecta | antimycobacterial |

| 117 | 16-epi-Scalarolbutenolide [36] | H. erecta | antimycobacterial |

| 118 | 3-Acetylsesterstatin [36] | H. erecta | antimycobacterial |

| 119 | Salmahyrtisol A [37] | H. erecta | |

| 120 | Hyrtiosal [37] | H. erecta | |

| 121 | Salmahyrtisol B [37] | H. erecta | cytotoxic (anti-tumor) |

| 122 | 19-Acetyl sesterstatin [37] | H. erecta | cytotoxic (anti-tumor) |

| 123 | Scalarolide [37] | H. erecta | |

| 124 | Salmahyrtisol C [37] | H. erecta | |

| 125 | 16-Hydroxyscalarolide [38] | H. erecta | Cytotoxic, antimycobacterial |

| 126 | 12-O-Deacetyl-12-epi-scalarine [38] | H. erecta | Cytotoxic, antimycobacterial |

| 127 | (−)-Wistarin [39] | Ircinia wistarii | |

| 128 | (+)-Wistarin [39] | I. wistarii | |

| 129 | (−)-Ircinianin [39] | I. wistarii | |

| 130 | Bilosespens A [40] | Dysidea cinerea | Cytotoxic |

| 131 | Bilosespens A [40] | D. cinerea | Cytotoxic |

Figure 10.

Structures of sesterterpenes (114–131).

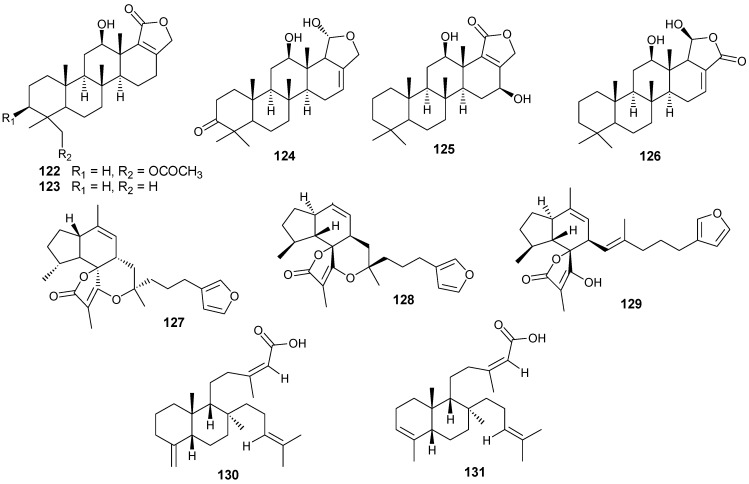

4.2. Norsesterterpenes

Norsesterterpenes have been isolated from the sponge species Diacarnus erythraeanus with examples shown in Table 8 and Figure 11. Antitumor natural peroxide products are known to induce cytotoxicity in cancer cells through the generation of particular reactive oxygen species (ROSs). Compounds 134–135 displayed mean IC50 growth inhibitions less than 10 μM with several tumor cell lines [41]. However, additional studies with 135 established no in vitro selective growth inhibition between normal and tumor cells. In assaying three cancer cells including murine leukemia (P-388), human lung carcinoma (A-549) and human colon carcinoma (HT-29), 140–143 exhibited an IC50 greater than 1 μg/mL [15] while 145 showed lower cytotoxicity against the same lines [42].

Table 8.

Norsesterterpenes, sources and activities.

| No. | Name | Source | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 132 | Nuapapuin A methyl ester [41] | Diacarnus erythraeanus | |

| 133 | Methyl-2-epinuapapuanoate [41] | D. erythraeanus | |

| 134 | (−)-13,14-Epoxymuqubilin A [41] | D. erythraeanus | anti-tumor |

| 135 | (−)-9,10-Epoxymuqubilin A [41] | D. erythraeanus | anti-tumor |

| 136 | (−)-Muqubilin A [41,43] | D. erythraeanus | anti-tumor |

| 137 | Hurghaperoxide [41] | D. erythraeanus | |

| 138 | Sigmosceptrellin B [41] | D. erythraeanus | |

| 139 | Sigmosceptrellin B methyl ester [41] | D. erythraeanus | |

| 140 | Aikupikoxide A [15] | D. erythraeanus | cytotoxic |

| 141 | Aikupikoxide D [15] | D. erythraeanus | cytotoxic |

| 142 | Aikupikoxide C [15] | D. erythraeanus | cytotoxic |

| 143 | Aikupikoxide B [15] | D. erythraeanus | cytotoxic |

| 144 | Tasnemoxide A [42] | D. erythraeanus | cytotoxic (anti-tumor) |

| 145 | Tasnemoxide B [42] | D. erythraeanus | cytotoxic (anti-tumor) |

| 146 | Tasnemoxide C [42] | D. erythraeanus | cytotoxic (anti-tumor) |

| 147 | epi-Sigmosceptrellin B [44] | D. erythraeanus | |

| 148 | Muqubilone [45] | D. erythraeanus | antimalarial |

Figure 11.

Structures of norterpenes (132–148).

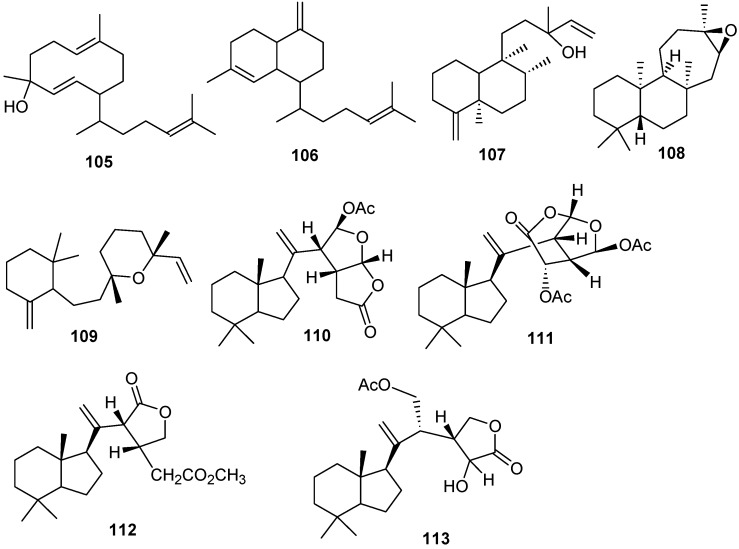

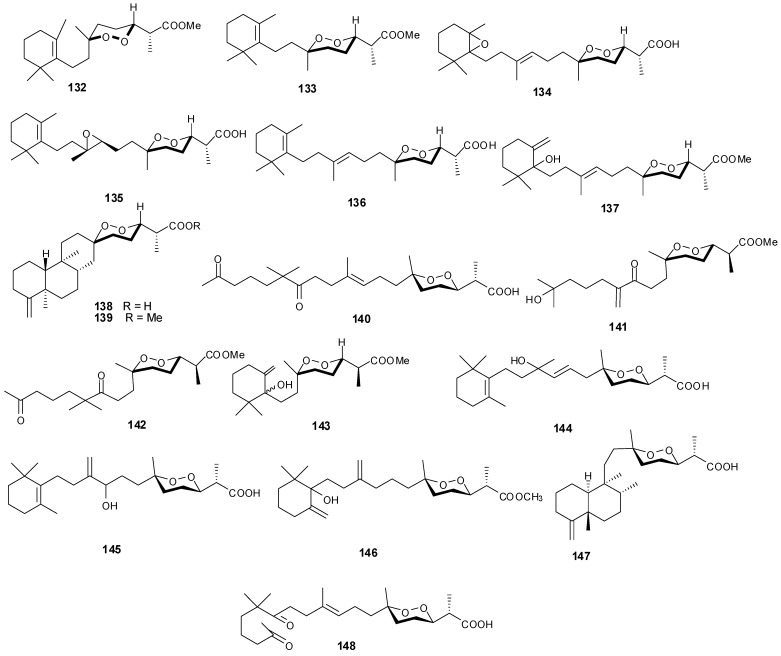

5. Triterpenes

Structurally diverse triterpenes are widespread in Red Sea sponges with examples shown in Table 9 and Figure 12. Compound 149 inhibits growth of human breast cancer cells, MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, BT-474 and T-47D, in a dose-dependent manner [46,47]. Triterpenes have also been studied for their efficacy in reducing the appearance of drug resistance. In the presence of many cytotoxic drugs, resistant cell variants appear, a process referred to as multidrug resistance (MDR). Overexpression of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter ABCB1/P-glycoprotein (P-gp) is one of the most common causes of MDR in cancer cells. P-gp a 170-kD transmembrane glycoprotein functions as a drug efflux pump that extrudes a wide spectrum of compounds including amphipathic and hydrophobic drugs. Sipholane triterpenoids can serve as P-gp inhibitors and are being developed to enhance the effect of chemotherapeutic drugs with MDR cancer cells in vitro and in vivo [33,36]. Compounds 162–163 enhanced cytotoxicity of several P-gp substrate-anticancer drugs, including colchicine, vinblastine and paclitaxel. These sipholane triterpenes significantly reversed the MDR-phenotype in P-gp-over expressing MDR cancer cells, KB-C2, in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, these sipholanes have no effect on the response to cytotoxic agents in cells lacking P-gp expression or expressing MRP1 (ABCC1) or MRP7 (ABCC10) or with the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2). Perhaps most importantly, these sipholanes with a low IC50 of ca. 50 μM are not toxic to the assayed cell lines [48].

Table 9.

Triterpenes, sources and activities.

| No. | Name | Source | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 149 | Neviotine-A [46,47] | Siphonochalina siphonella | |

| 150 | Sipholenol A [47,49,50,51,52,53] | S. siphonella | anti-tumor |

| 151 | SipholenolA-4-O-3′,4′-dichlorobenzoate [49] | S. siphonella | |

| 152 | Shaagrockol B [54] | Toxiclona toxius | |

| 153 | Shaagrockol C [54] | T. toxius | |

| 154 | Sipholenol G [55] | S. siphonella | |

| 155 | Sipholenone D [55] | S. siphonella | |

| 156 | Sipholenol F [55] | S. siphonella | |

| 157 | Sipholenol H [55] | S. siphonella | |

| 158 | Neviotine B [55] | S. siphonella | |

| 159 | Sipholenoside A [55] | S. siphonella | |

| 160 | Sipholenoside B [55] | S. siphonella | |

| 161 | Siphonellinol B [55] | S. siphonella | |

| 162 | Dahabinone A [55] | S. siphonella | |

| 163 | Sipholenone E [51] | S. siphonella | anti-tumor |

| 164 | Sipholenol L [47,51] | S. siphonella | anti-tumor |

| 165 | Sipholenol J [51] | S. siphonella | |

| 166 | (2S,4aS,5S,6R,8aS)-5-(2-((1S,3aS,5R,8aS,Z)-1-hydroxy-1,4,4,6-tetramethyl-1,2,3,3a,4,5,8,8a-octahydroazulen-5-yl)-ethyl)-4a,6-dimethyloctahydro-2H-chromene-2,6-diol [51] | S. siphonella | |

| 167 | Sipholenol K [51] | S. siphonella | |

| 168 | Sipholenol M [51] | S. siphonella | |

| 169 | Siphonellinol D [51] | S. siphonella | |

| 170 | Siphonellinol E [51] | S. siphonella | |

| 171 | Siphonellinol-C-23-hydroperoxide [51] | S. siphonella | |

| 172 | Siphonellinol C [56] | S. siphonella | |

| 173 | epi-Sipholenol I [56] | S. siphonella | |

| 174 | Sipholenol I [51] | S. siphonella | |

| 175 | Sipholenone A [56,47] | S. siphonella | |

| 176 | Sipholenol D [52] | S. siphonella | |

| 177 | Neviotine-C [47] | Siphonochalina siphonella | cytotoxic |

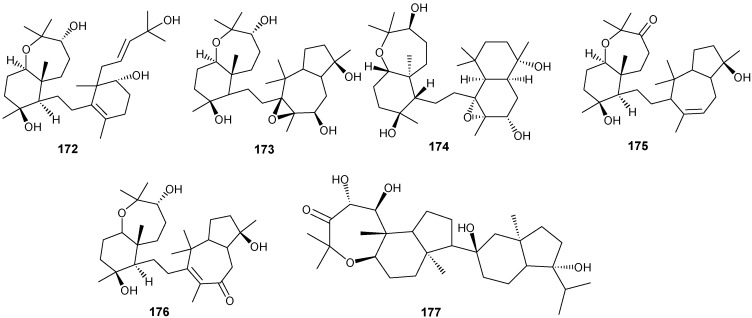

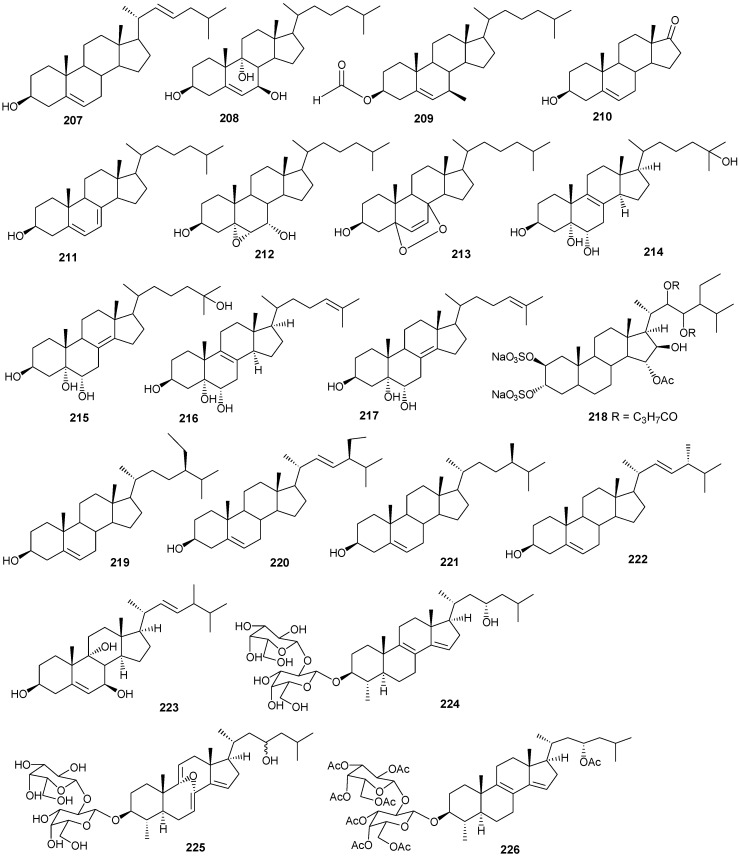

Figure 12.

Structures of triterpenes (149–177).

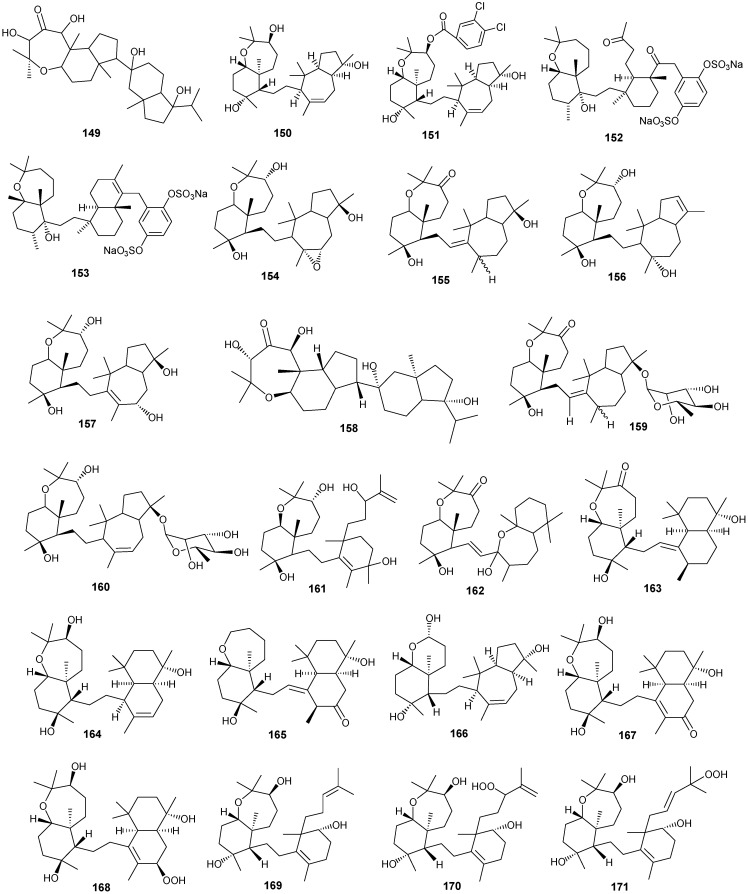

6. Steroids

Steriods are widespread throughout the marine biome with recent chemical reports including soft coral (Sinularia candidula, S. polydactyla, Heteroxenia ghardaqensis, Dendronephthya sp., Lobophytom depressum and Litophyton arboreum) [9,11,24,57,58,59,60], black coral (Antipathes dichotoma) [38,40], and sponges (Echinoclathria gibbosa, Hyrtios sp., Erylus sp., and Petrosia sp.) [18,64,65,66]. Steroid examples are shown in Table 10 and Figure 13.

Table 10.

Steroids, sources and activities.

| No. | Name | Source | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 178 | 3β-25-Dihydroxy-4-methyl-5α,8α-epidioxy-2-ketoergost-9-ene [57] | Sinularia candidula | anti-viral |

| 179 | Gorgosten-5(E)-3β-ol [58] | Heteroxenia ghardaqensis | anti-tumor |

| 180 | Gorgostan-3β,5α,6β,11α-tetraol (sarcoaldosterol A) [58] | H. ghardaqensis | |

| 181 | Gorgostan-3β,5α,6β-triol-11α-acetate [58] | H. ghardaqensis | |

| 182 | 5α-Pregna-3β-acetoxy-12β,16β-diol-20-one [59] | Echinoclathria gibbosa | anti-tumor |

| 183 | β-Sitosterol-3-O-(3Z)-pentacosenoate [59] | E. gibbosa | anti-tumor |

| 184 | Cholesterol [9] | Dendronephthya | |

| 185 | Dendronesterone A [9] | Dendronephthya | |

| 186 | 24-Methylcholestane-3β,5α,6β,25-tetrol-25-monoacetate [24] | Sinularia polydactyla | anti-tumor |

| 187 | 24-Methylcholestane-5-en-3β,25-diol [24] | S. polydactyla | antimicrobial |

| 188 | Lobophytosterol [60] | L. depressum | |

| 189 | 5β,6β-Epoxy-24E-methylchloestan-3β,22(R),25-triol [60] | L. depressum | |

| 190 | Depresosterol [60] | L. depressum | |

| 191 | (22R,24E,28E)-5β,6β-Epoxy-22,28-oxido-24-methyl-5α-cholestan-3β,25,28-triol [60] | L. depressum | |

| 192 | (22R,24E)-24-Methylcholest-5-en-3β,22,25,28-tetraol [60] | L. depressum | |

| 193 | 24-Methylcholesta-5,24(28)-diene-3β-ol [11] | Litophyton arboreum | |

| 194 | 7β-Acetoxy-24-methylcholesta-5-24(28)-diene-3,19-diol [11] | L. arboreum | cytotoxic |

| 195 | 24-Methylcholesta-5,24(28)-diene-3β,7β,19-triol [11] | L. arboreum | |

| 196 | Hyrtiosterol [16] | Hyrtios Species | |

| 197 | Eryloside A [61,62,63] | Genus Erylus | cytotoxic |

| 198 | (22E)-Methylcholesta-5,22-diene-1α,3β,7α-triol [64] | Antipathes dichotoma | anti-bacterial |

| 199 | 3β,7α-Dihydroxy-cholest-5-ene [64] | A. dichotoma | anti-bacterial |

| 200 | (22E,24S)-5α,8α-Epidioxy-24 methylcholesta -6,22-dien-3β-ol [64] | A. dichotoma | anti-bacterial |

| 201 | (22E,24S)-5α,8α-Epidioxy-24-methylcholesta-6,9(11),22-trien-3β-ol [64] | A. dichotoma | anti-bacterial |

| 202 | 3β-Hexadecanoylcholest-5-en-7-one [65] | A. dichotoma | anti-tumor |

| 203 | 3β-Hexadecanoylcholest-5-en-7β-ol [65] | A. dichotoma | anti-tumor |

| 204 | Cholest-5-en-3β-yl-formate [65] | A. dichotoma | anti-tumor |

| 205 | 3β-Hydroxycholest-5-en-7-one [65] | A. dichotoma | |

| 206 | Cholest-5-en-3β,7β-diol [65] | A. dichotoma | |

| 207 | 22-Dehydrocholestrol [65] | A. dichotoma | |

| 208 | 3β,7β,9α-Trihydroxycholest-5-en [66] | Petrosia | cytotoxic (anti-tumor) |

| 209 | Cholest-5-en-7β-methyl-3β-yl formate [66] | Petrosia sp. | cytotoxic (anti-tumor) |

| 210 | Dehydroepiandrosterone [66] | Petrosia sp. | cytotoxic (anti-tumor) |

| 211 | 7-Dehydrocholesterol [66] | Petrosia sp. | cytotoxic (anti-tumor) |

| 212 | 5α,6α-Epoxycholest-8(14)-ene-3β,7α-diol [66] | Petrosia sp. | cytotoxic (anti-tumor) |

| 213 | 5α,8α-Epidioxycholesta-6-en-3β-ol [66] | Petrosia sp. | cytotoxic (anti-tumor) |

| 214 | Cholesta-8-en-3β,5α,6α,25-tetrol [67] | Lamellodysidea herbacea | |

| 215 | Cholesta-8(14)-en-3β,5α,6α,25-tetrol [67] | L. herbacea | |

| 216 | Cholesta-8,24-dien-3β,5α,6α-triol [67] | L. herbacea | anti-fungal |

| 217 | Cholesta-8(14),24-dien-3β,5α,6α-triol [67] | L. herbacea | anti-fungal |

| 218 | Clathsterol [68] | Clathria sp. | |

| 219 | Clionasterol [69] | Dragmacidon coccinea | |

| 220 | Stigmasterol [69] | D. coccinea | |

| 221 | Campesterol [69] | D. coccinea | |

| 222 | Brassicasterol [69] | D. coccinea | |

| 223 | Dendrotriol [70] | Dendronephthya hemprichi | |

| 224 | Erylosides K [62] | Erylus lendenfeldi | |

| 225 | Erylosides L [62] | E. lendenfeldi | |

| 226 | Erylosides B [63] | E. lendenfeldi |

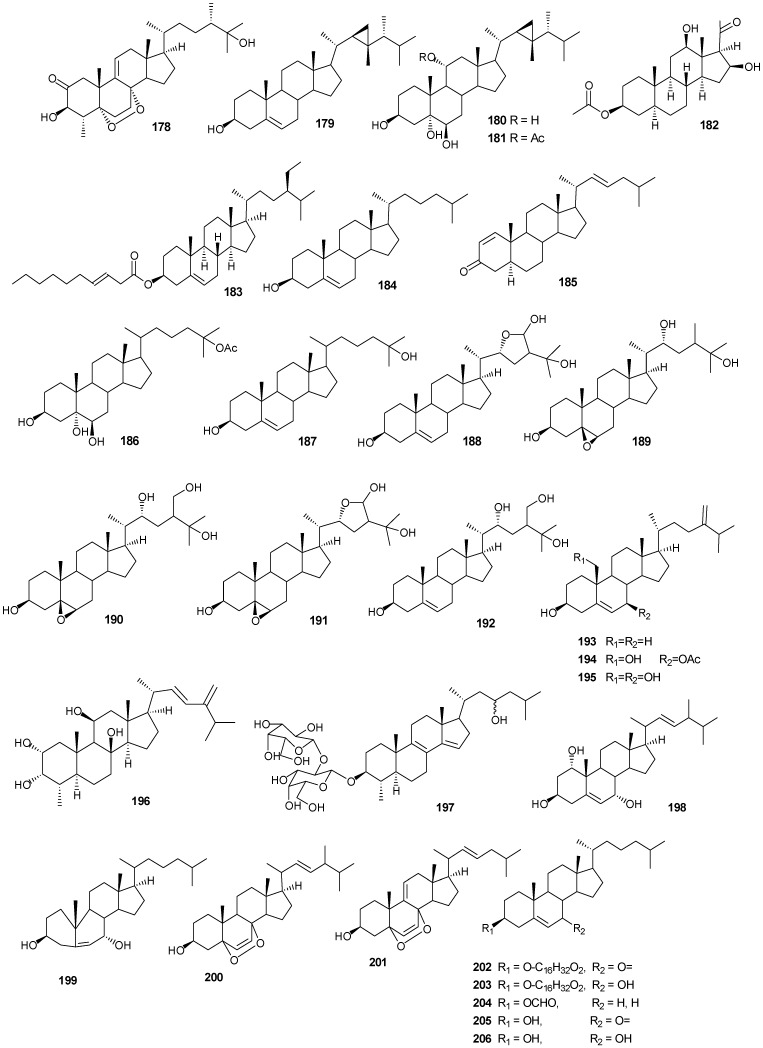

Figure 13.

Steriod structures (178–226).

Moderate growth inhibition for a human colon tumor cell line was observed with 180 [58]. Compounds 184 and 186 exhibited activity against three human tumor cell lines including the lung non-small cell line A549, the glioblastoma line U373 and the prostate line PC-3 [59]. Compound 187 showed an IC50 of 6.1 and 8.2 μg/mL against the human cancer cell lines HepG2 and HCT, respectively [24].

Compounds 204–207 show antibacterial activity against Gram-positive (Bacillus subtilis) and Gram-negative bacteria (Pseudomonas aeruginosa), at a 1 μg/ml concentration [64]. Compounds 208–210 exhibited antitumor activity based on four cancer panels: HepG2, WI 38, VERO, and MCF-7 [65]. Compounds 215–220 exhibited cytotoxic effects in the tumor cell lines, HepG2 and MCF-7 with IC50 in the range of 20-500 μM. Interestingly, 217 showed the highest affinity to DNA with IC50 30 μg/mL [66]. Compounds 223 and 224 showed antifungal activity against Candida tropicalis, with petri dish inhibition at 10 μg/disc [67].

7. Drug Leads

Even though terpenes are the largest group of natural products with over 25,000 structures thus far reported, a small subset of these metabolites have been investigated for biological function and/or activity. Basic biological constituents such as membrane components, hormones, antioxidants and chemical defenses require the isoprenoid building module. Future chemical studies of marine organisms are expected to generate an ensemble of novel terpenes based on progressive knowledge on enzymatic machinery and selective pressures under which such organisms have evolved. The expanding chemo-diversity of marine terpenes is being assisted in part by advanced analytical chemistry methods for structure determination and sophisticated diving techniques for sample collection.

Methods for assaying for in vitro biological activity can be more variable in terms of stardardized protocols. The same positive or native chemical controls are not always utilized making direct comparisons of biological activity between different testing laboratories unreliable or at least not reproducible. Moreover, with the paucity of ethnomedical knowledge from marine sources, the basis for selecting the most promising bioassay can be more of an art than a science. The screening for anti-cancer activity in facilities such as the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Chemotherapeutic Agents Repository operated by Fisher BioServices [71] can provide invaluable, cost-free, sensitive screening of hits against multiple-target 60 cancer cell line panels, broadening the opportunity to conduct more comprehensive and mechanistic studies. In the case where a set of metabolites has already been identified possessing a given biological activity, computational, in silico, and pharmacophore modeling can guide future design of druggable analogues with better biological activity, without expected toxicity, even if the structural characterization of the biological target(s) is/are not feasible. Such virtual models utilizes steric and electronic descriptors to identify pharmacophoric features such as hydrophobic centroids, aromatic rings, hydrogen bonding acceptors/donors and cation/anion interactions to match optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target that triggers or blocks a response. Functional group properties can also be identified for the rational semi-synthetic design of biologically active marine natural scaffolds. Strategies such as the Topliss scheme designate a series of substituents based on lipophilic, electronic and steric properties to generate multiple analogues with slight controlled chemical property differences that can be used for comprehensive structure-activity studies to obtain superior biological activity relative to the parent natural product. While these techniques and tools are not distinct or exclusive for exploring marine sources and marine-derived natural products, such methods can be effective for enhancing biological activity. For example, sipholenol A is a noteworthy example of developing a marine metabolite using medicinal chemistry approaches to generate biologically active analogue libraries [49]. These natural product examples with exceptional biological potency outcomes (IC50 in the low μM range for invasive breast cancer) demonstrate the potential of marine natural products for the discovery of future novel druggable entities useful for the control and management of human diseases.

8. Conclusions

Terpenoids provide a vast array of molecular architectures with the coral community of the Red Sea having added significantly to the structure database over the last thirty years. While marine invertebrates in this ecosystem are still being discovered, interest in both the chemistry and biological activity of Red Sea terpenes has generated many novel structures with promising biological activities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.McCarthy P.J., Pomponi S.A. A search for new pharmaceutical drugs from marine organisms. Mar. Biomed. Res. 2004;22:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appeltans W., Ahyong S.T., Anderson G., Angel M.V., Artois T., Bailly N., Bamber R., Barber A., Bartsch I., Berta A., et al. The magnitude of global marine species diversity. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:2189–2202. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinghorn A.D., Pan L., Fletcher J.N., Chai H. The relevance of higher plants in lead compound discovery programs. J. Nat. Prod. 2011;74:1539–1555. doi: 10.1021/np200391c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuesetani N. In: Drugs from the Sea. Fuesetani M., editor. Karger; Basel, Switzerland: 2000. pp. 1–5. Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faulkner D. Biomedical uses for natural marine chemicals. J. Ocean. 1992;35:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards A.J., Head S.M. Key Environments-Red Sea. Pergamon Press; Oxford, UK: 1987. p. 440. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tursch B., Tursch A. The soft coral community on a sheltered reef quadrat at Laing Island (Papua New Gunea) Mar. Biol. 1982;68:321–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00409597. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McFadden C.S., Sánchez J.A., France S.C. Molecular phylogenetic insights into the evolution of Octocorallia: A review. Int. Comp. Biol. 2010;50:389–410. doi: 10.1093/icb/icq056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elkhayat E.S., Ibrahim S.R.M., Fouad M.A., Mohamed G.A. Dendronephthols A–C, new sesquiterpenoids from the Red Sea soft coral Dendronephthya sp. Tetrahedron. 2014;70:3822–3825. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2014.03.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Sayed K.A., Hamann M.T. A new norcembranoid dimer from the Red Sea soft coral Sinularia gardineri. J. Nat. Prod. 1996;59:687–689. doi: 10.1021/np960207z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellithey M.S., Lall N., Hussein A.A., Meyer D. Cytotoxic, Cytostatic and HIV-1 PR inhibitory activities of the soft coral Litophyton arboretum. Mar. Drugs. 2013;11:4917–4936. doi: 10.3390/md11124917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Footy K.O., Alarif W.M., Asiri F., Aly M.M., Ayyad S.N. Rare pyrane-based cembranoids from the Red Sea soft coral Sarcophyton trocheliophorum as potential antimicrobial antitumor agents. Med. Chem. Res. 2015;24:505–512. doi: 10.1007/s00044-014-1147-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Lihaibi S.S., Alarif W.M., Abdel-Lateff A., Ayyad S.N., Abdel-Naim A.B., El-Senduny F.F., Badria F.A. Three new cembranoid-type diterpenes from Red Sea soft coral Sarcophyton glaucum: Isolation and anti-proliferative activity against HepG2 cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;81:314–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelman D., Benayahu Y., Kashman Y. Variation in secondary metabolite concentration in yellow and grey morphs of the red sea soft coral Parerythropodium fulvum fulvum: Possible ecological implications. J. Chem. Ecol. 2000;26:1123–1133. doi: 10.1023/A:1005423708904. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Youssef D.T.A., Yoshida W.Y., Kelly M., Scheuer P.J. Cytotoxic cyclic norterpene peroxides from a Red Sea sponge Diacarnus erythraenus. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:1332–1335. doi: 10.1021/np010184a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Youssef D.T.A., Singab A.B., van Soest R.W.M., Fusetani N. Hyrtiosenolides A and B, two new sesquiterpene-methoxybutenolides and a new sterol from a Red Sea sponge Hyrtios species. J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:1736–1739. doi: 10.1021/np049853l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaaban M., Shaaban K.A., Ghani M.A. Hurgadacin: A new steroid from Sinularia polydactyla. Steroids. 2013;78:866–873. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondracki M.B., Guyot M. A New Sesquiterpene tetronic acid derivative from the marine sponge Smenospongia sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:3149–3150. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(99)00384-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abad M.J., Berimejo P. Bioactive natural products from marine sources. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2001;25:683–755. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirsch S., Rudi A., Kashman Y., Loya Y. New avarone and avarol derivatives from the marine sponge Dysidea cinerea. J. Nat. Prod. 1991;54:92–97. doi: 10.1021/np50073a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elkhateeb A., El-Beih A.A., Gamal-Eldeen A.M., Alhammady M.A., Ohta S., Paré P.W., Hegazy M.F. New terpenes from the Egyptian soft coral Sarcophyton Ehrenberg. Mar. Drugs. 2014;12:1977–1986. doi: 10.3390/md12041977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abou El-Ezz R.F., Ahmed S.A., Radwan M.M., Ayoub N.A., Afifi M.S., Ross S.A., Szymanski P.T., Fahmy H., Khalifa S.I. Bioactive cembranoids from the Red Sea soft coral Sarcophyton glaucum. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013;54:989–992. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.12.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hegazy M.F., Mohameda T.A., Abdel-Latif F.F., Alsaid M.S., Shahat A.A., Paré P.W. Trochelioid A and B, new cembranoid diterpenes from the Red Sea soft coral Sarcophyton trocheliophorum. Phytochem. Lett. 2013;6:383–386. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2013.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aboutabl E.A., Azzam S.M., Michel C.G., Selim N.M., Hegazy M.F., Ali A.A.M., Hussein A.A. Bioactive terpenoids from the Red Sea soft coral Sinularia polydactyla. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013;27:2224–2226. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2013.805333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hegazy M.F., Gamal Eldeen A.M., Shahat A.A., Abdel-Latif F.F., Mohamed T.A., Whittlesey B.R., Paré P.W. Bioactive hydroperoxyl cembranoids from the Red Sea soft coral Sarcophyton glaucum. Mar. Drugs. 2012;10:209–222. doi: 10.3390/md10010209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hegazy M.F., El-Beihb A.A., Moustafad A.Y., Hamdy A.A., Alhammady M.A., Selim R.M., Abdel-Rehimb M., Paré P.W. Cytotoxic cembranoids from the Red Sea soft coral Sarcophyton glaucum. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2011;6:1809–1812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinamoni Z., Groweiss A., Carmely S., Kashman Y., Loya Y. Several new cembranoid diterpenes from three soft coral of the Red Sea. Tetrahedron. 1983;39:1641–1948. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)88575-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Groweiss A., Kashman Y. Eight new xenia diterpenoids from three soft coral of the Red Sea. Tetrahedron. 1983;39:3385–3396. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)91590-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hassan H.M., Khanfar M.A., Elnagar A.Y., Mohammed R., Shaala L.A., Youssef D.T.A., Hifnawy M.S., El Sayed K.A. Pachycladins A–E, prostate cancer invasion and migration inhibitory eunicellin-based diterpenoids from the Red Sea soft coral Cladiella pachyclados. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:848–853. doi: 10.1021/np900787p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Badria F.A., Guirguis A.N., Perovic S., Steffen R., Müller W.E., Schröder H.C. Sarcophytolide: A new neuroprotective compound from the soft coral Sarcophyton glaucum. Toxicology. 1998;131:133–143. doi: 10.1016/S0300-483X(98)00124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eltahawy N.A., Ibrahim A.K., Radwan M.M., ElSohly M.A., Hassanean H.A., Ahmed S.A. Cytotoxic cembranoids from the Red Sea soft coral, Sarcophyton auritum. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014;55:3984–3988. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isaacs S., Kashman Y. Juncins A–F, six new briarane diterpenoids from Gorogonian Junceella Juncea. J. Nat. Prod. 1990;53:596–602. doi: 10.1021/np50069a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiemer D.F., Meinwald J., Prestwich G.D., Solheim B.A., Clardy J. Biflora-4,10(19),15-triene: A new diterpene from a termite soldier (Isoptera Termitidae Termitinae) J. Org. Chem. 1980;45:191–192. doi: 10.1021/jo01289a048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rudi A., Kashman Y. Chelodane, barekoxids, and Zaatirin-three new diterpenoids from the marine sponge chelonaplysilla erecta. J. Nat. Prod. 1992;55:1408–1414. doi: 10.1021/np50088a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudi A., Kshman Y. Three new norrisolide related rearranged spongians. Tetrahedron. 1990;64:4019–4022. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90536-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Youssef D.T.A., Shaala L.A., Emara S. Antimycobacterial scalarane-based sesterterpenes from the Red Sea sponge Hyrtios erecta. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:1782–1784. doi: 10.1021/np0502645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Youssef D.T.A., Yamaki R.K., Kelly M., Scheuer P.J. Salmahyrtisol A, a novel cytotoxic sesterterpene from the Red Sea sponge Hyrtios erecta. J. Nat. Prod. 2002;65:2–6. doi: 10.1021/np0101853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashour M.A., Elkhayat E.S., Ebel R., Edrada R., Proksch P. Indole alkaloid from the Red Sea sponge Hyrtios erectus. ARKIVOC. 2007;15:225–231. doi: 10.3998/ark.5550190.0008.f22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fontana A., Fakhr I., Mollo E., Cimino G. (−)-Wistarin from the marine sponge Ircinia sp.: The first case of enantiomeric sesterterpenes. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 1999;10:3869–3872. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rudi A., Yosief T., Schleyer M., Kashman Y. Bilosespens A and B: Two novel cytotoxic sesterpenes from the Marine Sponge Dysidea cinerea. Org. Lett. 1999;3:471–472. doi: 10.1021/ol990058m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lefranc F., Nuzzo G., Hamdy N.A., Fakhr I., Banuls L.M.Y., Van Goietsenoven G., Villani G., Mathieu V., van Soest R., Kiss R., et al. In vitro pharmacological and toxicological effects of norterpene peroxides isolated from the Red Sea sponge Diacarnus erythraeanus on normal and cancer cells. Nat. Prod. 2013;76:1541–1547. doi: 10.1021/np400107t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Youssef D.T.A. Tasnemoxides A–C, new cytotoxic cyclic norsesterterpene peroxides from the Red Sea sponge Diacarnus erythraenus. J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:112–114. doi: 10.1021/np0340192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kashman Y., Rotem M. Muqubilin, a new C24—Isoprenoid from a marine sponge. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979;20:1707–1708. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)93630-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo Y., Gavagnin M., Mollo E., Trivellone E., Cimino G. A new norsesterterpene peroxide from a red sea sponge. Nat. Prod. Lett. 1996;9:105–112. doi: 10.1080/10575639608044933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.El Sayed K.A., Hamann M.T., Hashish N.E., Shier W.T., Kelly M., Khan A.A. Antimalarial, antiviral, and antitoxoplasmosis norsesterterpene peroxide acids from the Red Sea sponge Diacarnus erythraeanus. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:522–524. doi: 10.1021/np000529+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carmely S., Kashman Y. Neviotine-A, A new triterpene from the Red Sea sponge Siphonochalina siphonella. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:784–788. doi: 10.1021/jo00356a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ayyad S.N., Angawi R.F., Saqer E., Abdel-Lateff A., Badria F.A. Cytotoxic neviotane triterpene-type from the red sea sponge Siphonochalina siphonella. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2014;10:334–341. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.133292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abraham I., Jain S., Wuc C.P., Khanfar M.A., Dai Y.K.C., Shi Z., Chen X., Fu L., Ambudkar S.V., El Sayed K., et al. Marine sponge-derived sipholane triterpenoids reverse P-glycoprotein (ABCB1)-mediated multidrug resistance in cancer cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;80:1497–1506. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Akl M.R., Foudah A.I., Ebrahim H.Y., Meyer S.A., El Sayed K.A. The marine-derived sipholenol A-4-O-3′,4′-dichlorobenzoate inhibits breast cancer growth and motility in vitro and in vivo through the suppression of Brk and FAK signaling. Mar. Drugs. 2014;12:2282–2304. doi: 10.3390/md12042282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foudah A.I., Sallam A.A., Akl M.R., El Sayed K.A. Optimization, pharmacophore modeling and 3D-QSAR studies of sipholanes as breast cancer migration and proliferation inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;73:310–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jain S., Abraham I., Carvalho P., Kuang Y.H., Shaala L.A., Youssef D.T.A., Avery M.A., El Sayed K.A. Sipholane triterpenoids: Chemistry, reversal of ABCB1/P-Glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance, and pharmacophore modeling. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:1291–1298. doi: 10.1021/np900091y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ayyad S.N., Angawi R.F., Alarif W.M., Saqera E.A., Badriae F.A. Cytotoxic Polyacetylenes from the Red Sea Sponge Siphonochalina siphonella. Z. Naturforschung C. 2014;69:117–123. doi: 10.5560/znc.2013-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shi Z., Jain S., Kim I.W., Peng X.X., Abraham I., Youssef D.T.A., Fu L.W., Sayed K.E., Ambudkar S.V., Chen Z.S. Sipholenol A, a marine-derived sipholane triterpene, potently reverses P-glycoprotein (ABCB1)-mediated multidrug resistance in cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1373–1380. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Isaacs S., Kashman Y. Shaagrockol B and C: Two hexaprenylhydroquinone disulfates from the Red Sea sponge Toxiclona toxius. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:2227–2230. doi: 10.1016/0040-4039(92)88184-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kashman Y., Yosief T., Carmeli S. New triterpenoids from the Red Sea sponge Siphonochalina siphonella. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:175–180. doi: 10.1021/np0003950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jain S., Laphookhieo S., Shi Z., Fu L., Akiyama S., Chen Z.S., Youssef D.T.A., Soest R.W.M., El Sayed K.A. Reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance by sipholane triterpenoids. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:928–931. doi: 10.1021/np0605889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahmed S., Ibrahim A., Arafa A. Anti-H5N1 virus metabolites from the Red Sea soft coral Sinularia candidula. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013;54:2377–2381. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.02.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elshamy A.I., Abdel-Razik A.F., Nassar M.I., Mohamed T.K., Ibrahim M.A., El-Kousy S.M. A new gorgostane derivative from the Egyptian Red Sea soft coral Heteroxenia ghardaqensis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013;27:1250–1254. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2012.724417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mohamed G.A., Abd-Elrazek A.E.E., Hassanea H.A., Youssef D.T.A., van Soes R. New compounds from the Red Sea marine sponge Echinoclathria gibbosa. Phytochemistry Lett. 2014;9:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2014.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carmely S., Kashman Y. Isolation and structure elucidation of Lobophytosterol and three other closely related sterols: Five new C28 polyoxygenated sterols from the red sea soft coral lobophytum depressum. Tetrahedron. 1981;37:2397–2403. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)88896-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goob R., Rudi A., Kshman Y. Three new glycolipids from a Red Sea sponge of the genus Erylus. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:7921–7928. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(96)00363-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fouad M., Al-Trabeen K., Badran M., Wray V., Edrada R., Proksch P., Ebela R. New steroidal saponins from the sponge Erylus lendenfeldi. ARKIVOC. 2004;13:17–27. doi: 10.3998/ark.5550190.0005.d03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carmely S., Michal R., Loya Y., Kashman Y. The structure of eryloside A, a new antitumor and anti fungal 4-methylated steroidal glycoside from the sponge Erylus lendenfeldi. J. Nat. Prod. 1989;52:167–170. doi: 10.1021/np50061a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Al-lihaibi S.S., Ayyad S.N., Shaher F., Alarif W.M. Antibacterial sphingolipid and steroids from the black coral Antipathes dichotoma. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2010;58:1635–1638. doi: 10.1248/cpb.58.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alarif W.M., Abdel-lateff A., AL-lihaibi S.S., Ayyad S.N., Badria F.A., Alsofyani A.A., Abou-Elnaga Z.S. Marine bioactive steryl esters from the Red Sea black coral Antipathes dichotoma. Clean Soil Air Water. 2012;41:1116–1121. doi: 10.1002/clen.201200409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abdel-lateff A., Alarif W.M., Asfour H.Z., Ayyad S.N., Khedr A., Badria F.A., Al-lihaibi S.S. Cytotoxic effects of three new metabolites from Red Sea marine sponge, Petrosia sp. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014;37:928–935. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sauleau P., Bourguet-Kondracki M.L. Novel polyhydroxysterols from the Red Sea marine sponge Lamellodysidea herbacea. Steroids. 2005;70:954–959. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rudi A., Yosief T., Loya S., Hizi A., Schleyer M., Kashman Y. Clathsterol, a Novel Anti-HIV-1 RT Sulfated Sterol from the sponge Clathria species. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:1451–1453. doi: 10.1021/np010121s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abou-Hussein D.R., Badr J.M., Youssef D.T.A. Dragmacidoside: A new nucleoside from the Red Sea sponge Dragmacidon coccinea. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014;28:1134–1141. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2014.915828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shaaban M., Shaaban K.A., Abd-Alla H.I., Hanna A.G., Laatsch H. Dendrophen, a novel glycyrrhetyl amino acid from Dendronephthya hemprichi. Z. Naturforschung. 2011;66:425–432. doi: 10.5560/ZNB.2011.66b0425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fisher BioServices. [(accessed on 11 May 2015)]. Available online: http://www.fisherbioservices.com/company.