Highlights

-

•

Gangrenous cholecystitis has been seen more commonly in elderly subjects due to their asymptomatic nature, and many present to the emergency room later and had more complications due to delay in care.

-

•

Risk factors for gangrenous cholecystitis include age and WBC, thickened gallbladder wall on ultrasound and lack of mucosal enhancement. On physical exam, lack of Murphy’s sign, secondary to denervation from gangrenous changes can also increase the index of suspicion.

-

•

Presence of gangrenous cholecystitis can also increase patients’ postoperative complications, morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Gangrenous cholecystitis, Acute cholecystitis

Abstract

Introduction

Acute cholecystitis is a common surgical condition, but not many are aware of the serious complication of gangrenous cholecystitis (GC). Presence of GC increases patients’ postoperative complications, morbidity and mortality. Predictive factors for GC include age >45, male gender, white blood cell count >13,000/mm3 and ultrasound findings of a negative Murphy’s sign.

Case presentation

(1) GW, 83 male with dull right upper quadrant pain and a negative Murphy’s sign with further imaging showing a thickened septated gallbladder suggestive of GC. Patient’s surgery was difficult and he received a cholecystostomy tube for drainage. (2) PH, 75 male with minimal right upper quadrant pain, equivocal ultrasound with a negative Murphy’s sign and computer tomography (CT) showing acute cholecystitis. Patient was taken to the operating room for cholecystectomy, with pathology consistent with gangrenous cholecystitis.

Discussion

Multiple laboratory findings and imaging patterns have been found to be highly predictive of GC. Along with age and WBC, thickened gallbladder wall and lack of mucosal enhancement have been predictive of GC. On physical examination, lack of Murphy’s sign secondary to denervation from gangrenous changes also increases the index of suspicion for GC.

Conclusion

GC is a serious complication of acute cholecystitis with increased morbidity and mortality. There should be a high index of suspicion for GC if the above unique physical and laboratory findings are present.

1. Introduction

Acute cholecystitis is a commonly occurring entity that general surgeons encounter in their practice. Though the management of acute cholecystitis is commonplace, one must still be aware of the somewhat rare but serious complication of gangrenous cholecystitis (GC). Gangrenous cholecystitis occurs when increased distension in the gallbladder causing ischemia and necrosis [2,8]. While the treatment of gangrenous cholecystitis is similar to that of acute cholecystitis, the presence of GC increases the risk of postoperative complications, morbidity and mortality [1]. Here are two case presentations of patients who on history and physical examination had symptoms of “simple” acute cholecystitis, but in the operating room were found to have gangrenous changes, resulting in a more complicated intraoperative and postoperative course. These cases bring to light many of the risk factors to predict GC, in hopes to increase the suspicion for GC pre-operatively and avoid some of the complications noted postoperatively. Though an extensive literature search, some of the predictive factors for GC include age >45, male gender, which blood count (WBC) >13,000/mm3 and ultrasound/CT findings of negative Murphy’s sign, increased gallbladder wall thickening and lack of mucosal enhancement [1,3,5,6].

2. Case presentation

2.1. Patient 1

Mr. GW was an 83 year old man with a history of hypothyroidism, hyperlipidemia and osteoarthritis, who presented with 1–2 day history of nausea, non-bilious vomiting, and non-localized abdominal pain. He had complained of generalized weakness and malaise and had noticed he had darker urine. He denied fever or chills prior to presentation to the emergency room.

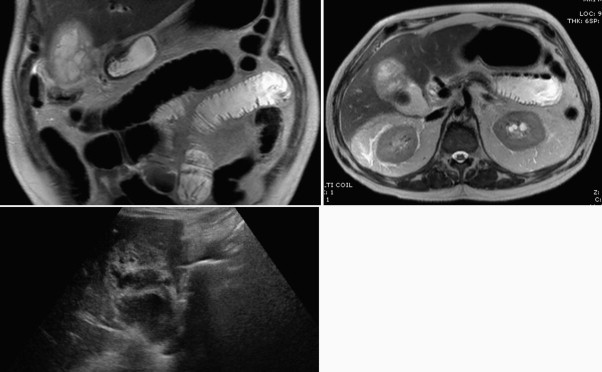

On physical exam he had a temperature of 37.8 °Celsius (C) and was hemodynamically stable. His abdominal examination revealed mild tenderness over the right upper quadrant with no signs of rebound or guarding. He was also noted to have a negative clinical Murphy’s sign. His admission laboratory testing showed WBC of 16,400/ mm3 with a left shift, and normal liver function tests except indirect bilirubinemia of 2.4 mg/dL. A right upper quadrant ultrasound was preformed and showed gallbladder dilation with wall thickness of 13 mm with septations, common bile duct of 7 mm, and sludge and stones suggestive of acute cholecystitis with a negative sonographic Murphy’s sign. Subsequent magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed a distended heterogeneous gallbladder with thickened trabeculated wall, with findings suggestive of gangrenous gallbladder (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Left to right: MRCP and ultrasound imaging from Mr. GW. #1 and #2: MRCP showing thickened gallbladder wall, lack of wall enhancement and septated surface with diffuse inflammation. #3: Ultrasound showing thickened wall, maximally dilated at 1.2 cm with multiple septations.

Patient was started on Ampicillin–Sulbactam empirically for acute cholecystitis, and on hospital day 2 patient remained clinically asymptomatic with a temperature of 38 °C. His WBC was trending down and patient taken for laparoscopy cholecystectomy. In the operating room (OR) there was found to be dense adhesions with the omentum covering the gallbladder, along with a walled off gangrenous gallbladder. Upon further visualization and dissection greyish liquefied necrotic material drained from the gallbladder. The dissection was difficult due to the edema and dense adhesions of omentum over liver and gallbladder surfaces so a cholecystostomy tube was inserted along with a second drain over the gallbladder bed. Postoperatively the patient did well, had no further complications and was able to tolerate a regular diet. He remained afebrile, had normalized WBC and was discharged home on postoperative day 4 with the drains in place and augmentin for 7 days. The patient was monitored closely postoperatively with frequent office visits, with the plan to have a definitive cholecystectomy in 4–6 months.

2.2. Patient 2

Mr. PH was a 75 year old male with history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia, who presented to the ER with a 2 h history of chest pain and abdominal discomfort radiating to the back. Patient was initially found to have a Mobitz type I heart block, and once he was medically stabilized, underwent workup for his abdominal pain.

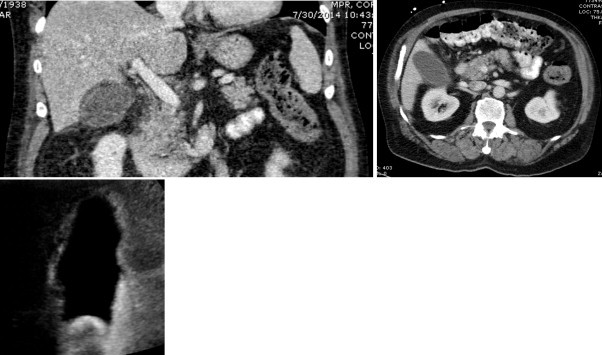

On physical exam he was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 220/102 mmHg which came down to 137/65 mmHg with appropriate intervention. His heart rate remained 60–75 and his abdominal examination was benign with no signs of tenderness or discomfort. The patient was tolerating food prior to arrival and had no nausea or vomiting episodes. On admission his laboratory findings showed normal WBC of 5400 mm3 and normal liver function tests. Right upper quadrant ultrasound was preformed showing cholecystitis with an irregular gallbladder wall, no pericholecystic fluid, negative sonographic Murphy’s sign and normal caliber common bile duct. Due to questionable ultrasound findings, computer tomography (CT) of the abdomen was preformed which showed mild gallbladder distension, gallstones and pericholecystic fluid suggestive of acute cholecystitis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

From left to right: Mr. PH, CT and ultrasound findings. #1 and #2: CT showing a distended gallbladder wall with decreased contrast enhancement of the wall and pericholecystic fluid. #3: Ultrasound showing normal mild gallbladder wall thickening with irregular appearance of the gallbladder.

With the ultrasound and CT findings confirming the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis, the patient was taken to the OR for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy on hospital day 2. In the OR he was found to have a markedly distended and tense gallbladder with friable tissues. The dissection was difficult due to the friable nature of the gallbladder but it was successful and the gallbladder was sent to pathology. The pathology showed signs of acute inflammation and areas of hemorrhage concerning for gangrenous changes. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and he was successfully discharged home the following day.

3. Discussion

Gangrenous cholecystitis (GC) is a rare but serious complication of acute cholecystitis. The pathophysiology is secondary to gallbladder distension, causing increased tension and pressure on the gallbladder wall. This distension later leads to ischemic changes and necrosis of the gallbladder [8].

The incidence of GC ranges from 2% to 30% in all patients with acute cholecystitis [7], and has been seen commonly in elderly patients [8]. Searching though the literature, it has been seen that the risk of GC is increased in patents older than age 50, with admission variables of heart rate >90 beats per minute, temperature >37.2 °C and WBC >14,000/mm3 [6]. Other articles have also included variables of serum sodium 135 mg/dL or less and hyperbilirubinemia as being statistically significant in the development of GC [2,6]. In the past there have been articles published identifying variables predictive of GC, including an article by Fagan, Merriam and Yacoub showing that male gender, leukocytosis and tachycardia can be predictive of GC [6]. In a more recent large retrospective study done in 2013, statistically significant factors that were significantly associated with GC included age >45, WBC > 13,000/mm3, gallbladder wall thickening >4 mm and heart rate > 90 beats per minute [1]. The risk of GC was also increased in patients with a history of diabetes [9].

An article by Contini et al. showed that 67% of patients with GC had mild complaints at initial presentation, and later developed more severe clinical presentations [10], which was very similar to our case presentations of elderly males with relatively benign physical examinations but intra-operatively were found to have surgically difficult gallbladders with signs of ischemia and necrosis. This finding of relatively asymptomatic to mildly symptomatic patients later having GC has been cited in the past and this finding is noted to be more common in elderly subjects. Due to their asymptomatic nature patients with GC tend to present to the emergency room later and are at higher risk of developing more complications due to delay in care [2]. It was also found that in elderly patients, the classical clinical presentation of acute cholecystitis was less frequent and more of them had underlining GC [2].

Alongside laboratory findings, there have been various articles looking at CT and ultrasound findings which can predict GC. Ultrasound findings predictive of GC include increased wall thickness along with elevated WBC [7]. Positive predictive finding of GC include findings of discontinuous and/ or irregular mucosal enhancement pattern, and it was found that the lack of mural enhancement was statistically significant correlating to GC along with gallbladder distension and wall thickening of >4.0–4.5 mm [3]. These two findings were present in both the case presentations, with patient 2’s pathology consistent with GC. Other CT and ultrasound findings that help predict GC include perfusion defect of the gallbladder wall, pericholecystic stranding and a negative Murphy’s sign [5], which was found in both of the patients as well. The reasoning for a negative Murphy’s sign could be due to denervation of the gallbladder, decreasing the suspicion for a more pathological process which is indeed present [7]. Due to the transmural necrosis of the gallbladder wall the afferent nerves die and the inflammation spreads to the parietal peritoneum, leading to generalized abdominal pain [7].

In our case presentations both men were over the age of 45 with thickened gallbladder wall >4 mm, had negative Murphy’s signs and CT or MRCP showing decreased gallbladder wall enhancement predictive of GC. These findings are noted retrospectively, but knowing that these patients were at risk for GC could have changed their preoperative course. Patients with GC are at increased risk of operative complications, including need for open cholecystectomy conversion and emergent surgical management including the need for a cholecystostomy tube [3]. In previous retrospective studies it has been found that patients with GC had a six-fold increase in risk of requiring conversion from laparoscopic to open, with an increased risk of severe blood loss, increased risk of bile duct injury and overall post-operative complication rate [1]. Though GC has a higher morbidity and mortality, laparoscopic cholecystectomy can still be safely preformed as long as there is a high index of suspicion prior to going into the operating room [4].

4. Conclusion

GC is a severe form of acute cholecystitis and is associated with increase morbidity, mortality and worse postoperative outcomes. Here are two case reports of elderly gentlemen with a presumed diagnosis of acute cholecystitis and near benign abdominal examinations with absence of a clinical or radiological Murphy’s signs. Both men were noted to have all the risk factors for GC including age > 45, male gender, WBC > 13,000/mm3, ultrasound and CT findings of irregular gallbladders with lack of mural enhancement, and were later found to have GC. Though the finding of GC does not change the surgical management of this disease, knowing that a patient is at increased risk of GC should prompt earlier surgical intervention to prevent some of the known complications from this disease.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

None needed.

Consent

No identifiable images are used in this case report (all are X-rays/ CT with no identifiable information). I have obtained written consent from the patients, and if needed, it can be provided.

Author contribution

Teena Dhir – main author.

Dr. Schiowitz – editor.

Guarantor

None.

References

- 1.Wu B., Buddensick T., Ferdosi H., Narducci D., Sautter A. Predicting gangrenous cholecystitis. Hepato-Pancreato-Billary Assoc. 2014;16:801–806. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikfarjam M., Niumsawatt V., Sethu A., Fink M., Muralidharan V. Outcomes of contemporary management of gangrenous and non-gangrenous acute cholecystitis. Hepato-Pancreato-Billary Assoc. 2011;13:551–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00327.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh A., Sagar P. Gangrenous cholecystitis: prediction with CT imaging. Abdom. Imaging. 2005;30:218–221. doi: 10.1007/s00261-004-0217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stefanidis D., Bingener J., Richards M., Schwesinger W., Dorman J. Gangrenous cholecystitis in the decade before and after the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J. Soc. Laparoscopic Surg. 2005;9:169–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu C., Chen C., Wang C., Wong Y., Wang L. Discrimination of gangrenous from uncomplicated acute cholecystitis: accuracy of CT findings. Abdom. Imaging. 2011;36:174–178. doi: 10.1007/s00261-010-9612-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falor A., Zobel M., Kaji A., Neville A., Virgilio C. Admission variables predictive of gangrenous cholecystitis. Am. Surg. 2012;78:1075–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teefey A., Dahiya N., Middleton W., Bajaj S., Dahiya N. Acute cholecystitis: do sonographic findings and WBC count predict gangrenous changes? Gastrointest. Imaging. 2013;200:363–369. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaudhry S., Hussain R., Rajasundaram R., Corless D. Gangrenous cholecystitis in an asymptomatic patient found during an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2011;5:199–201. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fagan S., DeBakey M. Prognostic factors for the development of gangrenous cholecystitis. Am. J. Surg. 2003;186:481–485. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Contini S., Corradi D., Busi N., Alessandri L., Pezzarossa A. Can gangrenous cholecystitis be prevented? A plea against a ‘wait and see’ attitude. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2004;38:710–716. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000135898.68155.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]