Highlights

-

•

Palliation of dysphagia with esophageal stenosis via esophageal stent placement is an effective procedure.

-

•

Migration is one of the most common complication after stent placement.

-

•

The lumen of stent is often allow to the passage in the intestine, so symptoms may develop much later.

-

•

Intestinal perforation is a rare but serious complication of stent migration.

Keywords: Esophagus cancer, Stent, Migration, Esophagectomy, Endoscopic intervention

Abstract

Introduction

Endoscopic esophageal stent placement is used to treat benign strictures, esophageal perforations, fistulas and for palliative therapy of esophageal cancer. Although stent placement is safe and effective method, complications are increasing the morbidity and mortality rate. We aimed to present a patient with small bowel perforation as a consequence of migrated esophageal stent.

Presentation of case

A 77-years-old woman was admitted with complaints of abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and vomiting for two days. Her past medical history included a pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic tumor 11 years ago, a partial esophagectomy for distal esophageal cancer 6 months ago and an esophageal stent placement for esophageal anastomotic stricture 2 months ago. On abdominal examination, there was generalized tenderness with rebound. Computed tomography showed the stent had migrated. Laparotomy revealed a perforation localized in the ileum due to the migrated esophageal stent. About 5 cm perforated part of gut resected and anastomosis was done. The patient was exitus fifty-five days after operation due to sepsis.

Discussion

Small bowel perforation is a rare but serious complication of esophageal stent migration. Resection of the esophagogastric junction facilitates the migration of the stent. The lumen of stent is often allow to the passage in the gut, so it is troublesome to find out the dislocation in an early period to avoid undesired results. In our case, resection of the esophagogastric junction was facilitated the migration of the stent and late onset of the symptoms delayed the diagnosis.

Conclusion

Patients with esophageal stent have to follow up frequently to preclude delayed complications. Additional technical procedures are needed for the prevention of stent migration.

1. Introduction

Endoscopic esophageal stent placement is used to treat benign strictures, esophageal perforations, fistulas and for palliative therapy of esophageal cancer [1–6]. Although stent placement is safe and effective method, complications are increasing the morbidity and mortality rate. Migration is one of the most common complication after stent placement [7]. The majority of migrations are often asymptomatic but they can cause hazardous issues like tracheoesophageal fistula formation, bleeding, obstruction and perforation. Nevertheless, migrated stents can exit via the rectum or remain in the body without complications.

Intestinal perforation is a rare and potentially lethal complication of stent migration. We presented a patient with small bowel perforation as a consequence of migrated esophageal stent and, to our knowledge, there was five cases previously reported [8–12] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reported cases of small bowel perforation due to a migrated esophageal stent.

| Reference | Age(year)/gender | Diagnosis | Pre-stent surgical procedures | Perforation time after stent placement | Perforation site due to the stent | Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current case | 77/Female | Distal esophageal adenocarcinoma | Esophagogastrectomy and esophagojejunostony | 2 Months | Ileum | Resection of the perforated small intestinal segment including the stent |

| Zhang et al. [12] | 17/Male | Tracheoesophageal fistula | None | 3 Weeks | Two perforations, at the antimesenteric border of the jejunum proximal to the Treitz ligament | Perforations were closed. Stent was left in situ. At 6 days after the laparotomy, stent was expelled per rectum |

| Bay and Penninga [11] | 80/Male | İnoperable distal esophageal adenocarcinoma | None | 3 Months | Jejunal perforation located 50 cm from Treitz's ligament | Resection of perforated small intestinal segment including the stent |

| Reddy et al. [10] | 79/Female | Squamous cell carcinoma of the lower esophagus | None | 12 Months (6 month after insertion the stent had migrated to the stomach; six month after migration intestinal perforation was demonstrated.) | Terminal ileum | Right hemicolectomy |

| Kim et al. [9] | 86/Male | Squamous cell carsinoma in the distal esophagus | None | 2 Months | Duodenal perforation | Percutaneous drainage, no surgical intervention |

| Henne et al. [8] | 52/Female | Squamous cell carcinoma | Esophagectomy and colon interposition | 2 Weeks after insertion of second stent | Anastomotic perforation of the former side-to-side jejunostomy | Resection and reconstruction |

2. Presentation of case

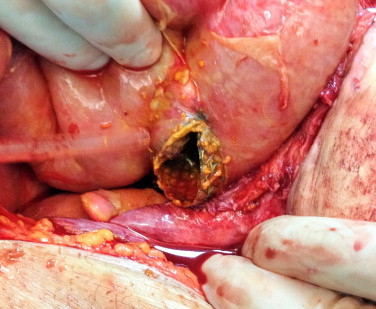

A 77-years-old woman was admitted to our hospital with complaints of abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and vomiting for two days. Her past medical history included a pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic tumor 11 years ago, a partial esophagectomy for distal esophageal cancer 6 months ago and an esophageal stent placement (Niti-S fully covered self-expanding stent, Taewoong Medical, Seoul, Korea) by a gastroenterologist after an unsuccessful dilatation procedure for esophageal anastomotic stricture 2 months ago. The patient has not gone for follow-up appointments which was scheduled. On abdominal examination, there was generalized tenderness with rebound. Computed tomography showed the stent had migrated (Fig. 1). Surgery was performed and laparotomy revealed a perforation localized in the ileum due to the migrated esophageal stent (Fig. 2). The stent was taken out of the abdomen from the perforated area of the intestine. About 5 cm perforated part of gut resected and anastomosis was done. She was admitted to intensive care unit after surgery. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome was diagnosed in postoperative day 3. A multidisciplinary approach was carried out to overcome the progression clinical problems. The patient was exitus fifty-five days after operation due to sepsis.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography revealed the stent in the left inferior of the abdomen.

Fig. 2.

Perforated part of the ileum and migrated esophageal stent.

3. Discussion

Esophageal strictures can be caused by malignant or benign disorders and esophageal stents are the most frequent method used for treatment of esophageal strictures, regardless of etiologic conditions [5,13]. Also stenting is safe and effective procedure to provide continuance of oral nutrition [1]. Ability to swallow only liquids and complete obstruction or presence of tracheoesophageal fistula are indications for stent placement patients with dysphagia [4]. Rarely, esophageal tumors block the airway and result in breathing difficulties. Stent placement may be an option to improve breathing ability and to ease pain and discomfort.

Stent migration is a common strait after stent placement. Additionally, esophageal stent complications include gastroesophageal reflux, bleeding, stent occlusion, tracheoesophageal fistula formation, intestinal obstruction or perforation. There is no optimized stent form or a stent placement technique. Fully covered stents, plastic stents, concurrent chemotherapy or radiotherapy increase the risk of migration [14,15]. An ideal stent should be easy to place, have low migration rates and also insertion and removal should be associated with minimal complications. Researchers are not only developing various types of stents to reduce complications but also exploring new stent fixation procedures to prevent the migration. In our hospital, gastroenterologists perform stent placement procedure and do not use any fixation technique to prevent stent migration.

In general, most stents migrate no further than stomach and remain in the stomach without complications. Thus, small bowel perforation is a rare complication of migrated esophageal stent. Six cases of small bowel perforation due to migrated esophageal stent, including our present case, have been reported in the literature [8–12] (Table 1). Henne et al. [8] reported a case of esophagectomy and colon interposition. Six month later, they revealed a stenosis in the cervical anastomosis and implanted a silicon-coated, wall stent. Six months later from the first stent, they noted a stenosis at the oral end of the stent and inserted a second one and two weeks later, they encountered the patient with small bowel perforation. Our patient had a history of total gastrectomy with esophagojejunostomy. These two cases suggest that resection of the esophagogastric juntion or pylorus may facilitate the migration of esophageal stents into the small bowel.

The other reported cases of small bowel perforation due to a migrated esophageal stent had no pre-stent surgical procedure. Kim et al. [9] described a patient who refused to undergo chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Eight months later, the patient underwent a palliative esophageal stent placement with a modified Gianturco stent (Song stent; Soho Medi-Tec). Because of the tumoral extention to cardia, lower end of stent was projected into fundus. Obligatory position of the stent rolled a potential effect to stent migration in their case. Reddy et al. [10] described a female patient who refused surgery for lower esophageal carcinoma and underwent chemoradiotherapy. She had a covered self-expanding metallic esophageal stent (Choostent; Solco Intermed, Seoul, Korea). Six months after insertion, stent fracture and migration to stomach was noted. Twelve months after insertion, perforation of the terminal ileum was demonstrated. Bay and Penninga [11] reported a case of inoperable distal esophageal adenocarcinoma and stented with a coated self-expanding esophageal stent. Their patient underwent chemoradiotherapy and revealed good response to the treatment. Unfortunately, it is clear that decreased size of the tumor by chemoradiotherapy allowed to stent migration. Zhang et al. [12] described a case with a history of a silicone-covered self expanding metallic esophageal stent (MTN-SE-G-20/80, Nanjing, China) 3 weeks previously for a tracheoesophageal fistula. Plain abdominal radiograph of their patient showed the stent lying in the inferior abdominal cavity and there was no evidence of intestinal obstruction or perforation. After two days of follow up, the patient failed to improve and experienced progressive abdominal pain. At laparotomy, two perforations were identified at the antimesenteric border of the jejunum proximal to the Treitz’s ligament.

A point to be noted is that the lumen of stent is often allow to the passage in the gut, so it is troublesome to find out the dislocation in an early period to avoid undesired results. In our case, resection of the esophagogastric junction was facilitated the migration of the stent and late onset of the symptoms up to mentioned passage delayed the diagnosis. Surgeons should be on the alert to the possibility of stent migration in patient with resection of esophagogastric junction.

If feasible, we prefer endoscopic removal of the stents in the stomach. Additionally, stents in the large bowel mostly move out via the rectum spontaneously. We suggest to observe such cases with migrated stents in the colon. Patients with migrated stents in the small bowel should be observe closely. We have to keep in mind abdominal exploration according to clinical outcomes.

In our hospital, gastroenterologists carry out non-surgical treatment of the esophageal stenosis by balloon dilatation or stent placement. This team does not use a stent fixation method and we understood that further studies are necessary to develop safety techniques for stenting.

4. Conclusion

Patient with esophageal stent have to follow up frequently to preclude delayed complications. There were five cases previously reported in the literature. These cases reveal the importance of elective surgical removal of migrated stents and the necessity of additional technical procedures for the prevention of stent migration.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Not a research study.

Authors contribution

Ali Tardu, Mehmet Ali Yagci and Ismail Ertugrul participated in the care of the patient.

Servet Karagul performed the literature review and drafted the manuscript.

Serdar Kirmizi and Fatih Sumer assisted in the review of the literature and in revising the manuscript.

Cengiz Ara was involved in revising it critically for important intellectual content.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this Journal.

Guarantor

Servet Karagul M.D., servetkaragul@hotmail.com.

Contributor Information

Servet Karagul, Email: servetkaragul@hotmail.com.

Mehmet Ali Yagci, Email: maliyagci@gmail.com.

Cengiz Ara, Email: aracengiz@yahoo.com.

Ali Tardu, Email: tarduali@gmail.com.

Ismail Ertugrul, Email: is_ertugrul@hotmail.com.

Serdar Kirmizi, Email: drserdarkirmizi@hotmail.com.

Fatih Sumer, Email: fatihsumer@outlook.com.

References

- 1.Cordero J.A., Moores D.W. Self-expanding esophageal metallic stents in the treatment of esophageal obstruction. Am. Surg. 2000;66(10):956–958. (discussion 958–959) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma P., Kozarek R. Role of esophageal stents in benign and malign diseases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010;105:258–273. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kochman M.L., McClave S.A., Boyce H.W. The refractory and the recurrent esophageal stricture: a definition. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2005;62:474–475. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conio M., Blanchi S., Filiberti R., De Ceglie A. Self-expanding plastic stent to palliate symptomatic tissue in/overgrowth after self-expanding metal stent placement for esophageal cancer. Dis. Esophagus. 2010;23:590–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madhusudhan C., Saluja S.S., Pal S., Ahuja V., Saran P., Dash N.R., Sahn P., i Chattopadhyay T.K. Palliative stenting for relief of dysphagia in patients with inoperable esophageal cancer: impact on quality of life. Dis. Esophagus. 2009;22:331–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burstow M., Kelly T., Panchani S., Khan I.M., Meek D., Memon B., Memon M.A. Outcome of palliative esophageal stenting for malignant dysphagia: a retrospective analysis. Dis. Esophagus. 2009;22:519–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.00948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoppmann S.F., Langer F.B., Prager G., Zacherl J. Outcome and complications of long-term self-expanding esophagealstenting. Dis. Esophagus. 2013;26:154–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henne T.H., Schaeff B., Paolucci V. Small-bowel obstruction and perforation: a rare complication of an esophageal stent. Surg. Endosc. 1997;11:383–384. doi: 10.1007/s004649900369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim H.C., Han J.K., Kim T.K., Do K.H., Kim H.B., Park J.H., Choi B.I. Duodenal perforation as a delayed complication of placement of an esophageal stent. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2000;11(7):902–904. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61809-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy V.M., Sutton C.D., Miller A.S. Terminal ileum perforation as a consequence of a migrated and fractured oesophageal stent. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2009;3(1):61–66. doi: 10.1159/000210542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bay J., Penninga L. Small bowel ileus caused by migration of oesophageal stent. Ugeskr Laeger. 2010;172(33):2234–2235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W., Meng W.J., Zhou Z.G. Multiple perforations of the jejunum caused by a migrated esophageal stent. Endoscopy. 2011;43(Suppl. 2):UCTN:E145–E146. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Boeckel P.G., Dua K.S., Weusten B.L., Schmits R.J., Surapaneni N., Timmer R., Vleggaar F.P., Siersema P.D. Fully covered self-expandable metal stents (SEMS), partially covered SEMS and self-expandable plastic stents for the treatment of benign esophageal ruptures and anastomotic leaks. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martins Bda C., Retes F.A., Medrado B.F., de Lima M.S., Pennacchi C.M., Kawaguti F.S., Safatle-Ribeiro A.V., Uemura R.S., Maluf-Filho F. Endoscopic management and prevention of migrated esophageal stents. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2014;6(2):49–54. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i2.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pavlidis T.E., Pavlidis E.T. Role of stenting in the palliation of gastroesophageal junction cancer: a brief review. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2014;6(3):38–41. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v6.i3.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]