Highlights

-

•

Ulcerative colitis has a peak incidence which coincides with the childbearing age of females.

-

•

Acute fulminant colitis during pregnancy is rare, but requires mandatory surgical colectomy which carries a significant risk to both mother and fetus.

-

•

We recommend that female patients planning to conceive with a known diagnosis of ulcerative colitis have an optimised medical regimen by liaising with their obstetricians and gastroenterologists to prevent exacerbations and the development of toxic megacolon.

-

•

Should surgical intervention become required, this can be performed with favourable outcomes for mother and child as demonstrated in this report.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, Toxic megacolon, Pregnancy, Colectomy

Abstract

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis is an idiopathic inflammatory bowel condition whose peak incidence coincides with fertility in female patients. In pregnancy, acute fulminant colitis is rare, and, when it becomes refractory to maximum medical therapy, emergency colectomy is mandated. Over the past quarter century, there have been few reports of this rare event in the literature.

Presentation of case

We report a 26 year old primigravida female who presented with toxic megacolon during the third trimester of pregnancy, unresponsive to medical therapy. She subsequently underwent an urgent low transverse caesarean section with a total colectomy. Both mother and child made a satisfactory recovery post operatively.

Discussion

Although the fetus is at higher risk than the mother in such a circumstance, morbidity and mortality rates are still noticeably high for both, and therefore, prompt diagnosis is key.

Conclusion

It is imperative that female patients planning to conceive with a known diagnosis of ulcerative colitis liaise with their obstetricians and gastroenterologists early to optimise medical treatment to prevent the development of a toxic megacolon and that conception is planned during a state of remission. Should surgical intervention become required, this can be performed with favourable outcomes for mother and child, as demonstrated in this report.

1. Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) was first described by the British physician Sir Samuels Wilks in 1859 [1]. It is an idiopathic inflammatory bowel condition, depicted as a chronic, relapsing disease whose intestinal manifestations are restricted to the colon [1,2], although a subset of patients may also develop ileal inflammation or so-called ‘backwash ileitis’ [2,3]. It has been estimated that between 30 and 50% of female patients with UC will have an exacerbation during pregnancy or in the early postpartum period [4–7]. Patients with active disease at the time of conception may have an increased risk of spontaneous abortion. Rates of preterm delivery, low birth weight (<2500 g), and congenital anomalies are also increased [8]. A rare but potentially fatal complication of UC is toxic megacolon. This condition is characterised pathologically by severe, transmural inflammation with infiltration of the colonic wall by neutrophils, lymphocytes, histiocytes and plasma cells [9]. The most significant risk of toxic megacolon is perforation into the surrounding peritoneal cavity which holds a considerable mortality rate due to the sequalae of sepsis [10–12]. The development of toxic megacolon during pregnancy is an unusual occurrence. Only seven authors with a combined eleven cases have been described in the literature (Table 1) [11–17]. Here, we illustrate a case report of a 26 year old female that developed toxic megacolon at 31 weeks gestation.

Table 1.

Summary of reported cases of toxic megacolon in pregnancy.

| Authors | Year | n | Maternal gestation (weeks)a | Maternal mortality (%) | Fetal mortality (%) | Pooled fetal and maternal mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marshak et al. [15] | 1960 | 1 | 24 | 0 | 100 | 50 |

| Peskin and Davis [16] | 1960 | 1 | 24 | 0 | 100 | 50 |

| Holzbach [17] | 1969 | 2 | 22,30 | 50 | 100 | 75 |

| Becker [12] | 1972 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cooksey et al. [13] | 1985 | 1 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anderson et al. [14] | 1987 | 3 | 33,34,37 | 0 | 33 | 17 |

| Ooi et al. [11] | 1985 | 2 | 10,16 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | – | 11 | – | – | – | – |

Represents the gestational period at which the diagnosis of toxic megacolon was established.

2. Case report

A 26 year old primigravida female with an eight year history of ulcerative colitis presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain, fever, bloody diarrhoea, and generalised weakness. At this initial presentation, the patient was at 26 weeks gestation and had poorly controlled colitis requiring tri-modal therapy with mesalazine, 6-mercaptopurine and prednisolone. The patient was stabilised initially with conservative management including analgesia, intravenous fluids and intravenous steroids and was subsequently discharged. She was then readmitted at 31 weeks gestation with systemic signs of sepsis, including tachycardia, hypotension and a pyrexia of 38.3 °C. Physical examination demonstrated a distended abdomen consistent with pregnancy, which was exquisitely tender on palpation and percussion with positive rebound tenderness indicative of peritonitis. Plain film abdominal X-ray demonstrated severe colonic distension without free air (Fig. 1). The patient underwent an emergent caesarean section via an infra-umbilical midline incision. The fetus was successfully delivered with apgar (appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, respiration) scores of 9 at one minute and 9 at five minutes; weight 1.474 kg and height 36.2 cm. Immediately after delivery, the midline incision was extended approximately 2 cm cephalad and a total abdominal colectomy with end ileostomy was performed. Total operative time for the combined procedures was 96 min and estimated blood loss was 250 ml. The patient was discharged nine days postoperatively in stable condition; while the neonate was stabilised in the intensive care unit, where, ventilator support was initially required. He was weaned off of the ventilator, transitioned to a neonatal progressive care unit and eventually discharged home two weeks after birth. Pathologic examination of the surgical specimen confirmed the diagnosis of toxic megacolon with transmural inflammation and erosion of the bowel wall in regions (Fig. 2). Four weeks post-operatively, the patient underwent completion proctectomy and creation of an ileal reservoir with construction of an ileoanal anastomosis and diverting ileostomy. The reason for accelerating the procedure was based on patient choice and the fact that she had recovered very well from her emergency colectomy. Operative time was 177 min and estimated blood loss was 200 ml. The loop ileostomy was reversed three months later (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Preoperative plain film abdominal radiograph of a 26 year old lady with suspected toxic colitis. The single frontal supine view demonstrates a diffusely distended transverse colon with displacement by the gravid uterus.

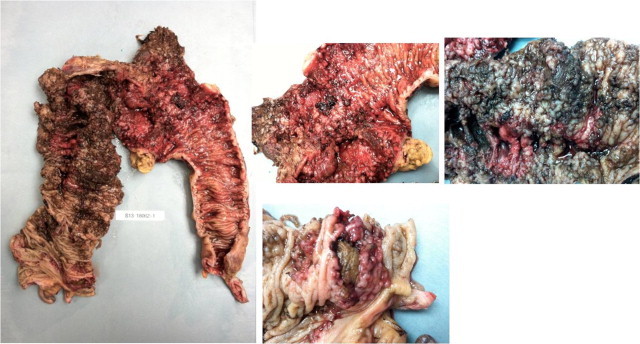

Fig. 2.

Macroscopic aspect of the colonic mucosa after total colectomy. A disruption on the wall of the ascending colon was noted as well as profuse haemorrhage and areas of intramural inflammation, with sparing of the ileocaecal valve and ileum.

Fig. 3.

Infraumbilical laparotomy and closure of ileostomy scars two months after ileostomy reversal.

Two months following the loop ileostomy reversal the patient was seen in clinic reporting 2–3 bowel movements a day, constitutionally well with optimal healing of her surgical wounds. The effect of reduced fertility due to the ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) formation in the future was explained during the consultation. The neonate measured between 40 and 50th centile in all his growth assessments and he also made a satisfactory recovery from the procedure.

3. Discussion

Although ulcerative colitis has a peak incidence which coincides with females of childbearing age, it does not affect fertility in women unless they have undergone curative treatment in the form of a proctocolectomy plus IPAA [18]. Several meta-analyses have found that IPAA conferred a two to three fold increased risk of infertility compared with medical management [19,20] The most likely mechanisms for impaired fertility following surgery are higher rates of hydrosalpinx, destruction of fimbria and tubal obstruction due to adhesions and scarring [21].

Studies have shown that disease status at the time of conception plays a vital role in predicting disease activity during pregnancy and also on the outcome of the pregnancy [22]. When conception occurs during a period of remission in inflammatory bowel disease then the risk of relapse during pregnancy is one-third and these patients are more likely to have quiescent disease activity during pregnancy [23]. This is the same risk of relapse in non-pregnant patients with Crohn’s disease. Conversely, women with UC or Crohn’s have a twofold risk of developing exacerbations during pregnancy if during conception they had active disease [24,25]. The underlying cause for the increased risk is not clearly understood.

In addition, active inflammatory bowel disease at the time of conception and during pregnancy has been shown to be associated with a high risk pre-term birth, low birth weight and small for gestational age birth compared with women with IBD whose disease is in remission during conception and during the course of the pregnancy [26–28]. Other predictors of adverse pregnancy outcomes include family history of IBD, disease localisation and IBD surgery [26–28].

Females that have an exacerbation of ulcerative colitis during their pregnancy (most likely first trimester [13]) or early postpartum period, are initially treated medically. Ulcerative colitis during pregnancy that is refractory to medical therapy can lead to the development of toxic megacolon. Over the past quarter of a century, there have been no reports of this rare event. This is perhaps because of improvements in the medications used to treat inflammatory bowel disease, including new classes of medicines – most notably recombinant monoclonal antibodies which target TNF-alpha (e.g. Infliximab). Previous literature demonstrates that different surgical options have been applied to the pregnant patient with a toxic megacolon [11–17]. Despite these variances is surgical approach, the objective is twofold: (a) save the mother by removing the diseased organ and (b) deliver the fetus, if at a viable gestation age. It is clear that fetal mortality is higher than maternal mortality, particularly when toxic megacolon occurs in the second trimester (Table 1) but morbidity and mortality rates are still noticeably high for both [14].

4. Conclusion

Ulcerative colitis refractory to medical therapy during pregnancy is rare however mandatory surgical intervention carries significant morbidity and mortality for both mother and fetus. Therefore, it is imperative that female patients planning to conceive with a known diagnosis of ulcerative colitis have an optimised medical regimen to prevent exacerbations and the development of toxic megacolon. Should surgical intervention become required, this can be safely performed with favourable outcomes for mother and child, as demonstrated in this report.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Sources of funding

None.

Ethical approval

None.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Authors contribution

Ayyaz Quddus, Henry Schoonyoung and Beatriz Martin Perez – wrote the article. Matthew Albert and Sam Atallah alongside Henry Schoonyoung – participated in the diagnosis and treatment of the present case. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Guarantor

Dr. Sam Atallah and Ayyaz Quddus.

References

- 1.Baumgart D.C., Carding S.R. Inflammatory bowel disease: cause and immunobiology. Lancet. 2007;369:1627–1640. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60750-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgart D.C., Sandborn W.J. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369:1641–1657. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60751-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford A.C. Ulcerative colitis: clinical review. BMJ. 2013;346:f432. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willoughby C.P., Truelove S.C. Ulcerative colitis and pregnancy. Gut. 1980;6:469–474. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.6.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korelitz B.I. Inflammatory bowel disease and pregnancy. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 1998;1:213–224. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen K.O., Juul S., Berndtsson I., Oresland T., Laurberg S. Ulcerative colitis: female fecundity before diagnosis, during disease, and after surgery compared with a population sample. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:15–19. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dozois E.J., Wolff B.G., Tremaine W.J., Watson W.J., Drelichman E.R., Carne P.W. Maternal and fetal outcome after colectomy for fulminant ulcerative colitis during pregnancy: case series and literature review. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2006;49:64–73. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornish J., Tan E., Teare J., Teoh T.G., Rai R., Clark S.K. A meta-analysis on the influence of inflammatory bowel disease on pregnancy. Gut. 2007;56:830–837. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.108324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheik R.A., Shagufta Y., Prindiville T. Toxic megacolon a review. JK Practioner. 2003;10:176–178. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheth S.G., Lamont J.T. Toxic megacolon. Lancet. 1998;351:509–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ooi B.S., Remzi F.H., Fazio V.W. Turnbull-Blowhole colostomy for toxic ulcerative colitis in pregnancy: report of two cases. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2003;46:111–115. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker I.M. Pregnancy and toxic dilatation of the colon. Am. J. Digest. Dis. 1972;17:79–84. doi: 10.1007/BF02239267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooksey G., Gunn A., Wotherspoon W.C. Surgery for acute ulcerative colitis and toxic megacolon during pregnancy. Br. J. Surg. 1985;72:547. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson J.B., Turner G.M., Williamson R.C. Fulminant ulcerative colitis in late pregnancy and the puerperium. J. Soc. Med. 1987;80:492–494. doi: 10.1177/014107688708000812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshak R.H., Korelitz B.J., Klein S.H. Toxic dilatation of the colon in the course of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1960;38:165–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peskin G.W., Davis A.V.O. Acute fulminating ulcerative colitis with colonic distension. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1960;110:269–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holzbach R.T. Toxic megacolon in pregnancy. Am. J. Digest. Dis. 1969;14:908–910. doi: 10.1007/BF02233212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alstead E.M. Inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy. Postgrad. Med. J. 2002;78:23–26. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.915.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajaratnam S.G., Eglinton T.W., Hider P., Fearnhead N.S. Impact of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis on female fertility: meta-analysis and systematic review. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:1365–1374. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1274-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waljee A., Waljee J., Morris A.M., Higgins P.D. Threefold increased risk of infertility: a meta-analysis of infertility after ileal pouch anal anastomosis in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2006;55:1575–1580. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.090316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oresland T., Palmblad S., Ellström M., Berndtsson I., Crona N., Hultén L. Gynaecological and sexual function related to anatomical changes in the female pelvis after restorative proctocolectomy. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 1994;9:77–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00699417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siddiqui A.A., Mahboob A., Ansari M., Alam I., Bashir B., Ahmed S. Effects of pregnancy on disease activity in Ulcerative Colitis. J. Postgrad. Med. Inst. 2011;25:314–317. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Woude C.J., Ardizzone S., Bengtson M.B., Fiorino G. The second European evidenced-based consensus on reproduction and pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohns Colitis. 2014:107–124. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jju006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oron G., Yogev Y., Shkolnik S., Hod M. Inflammatory bowel disease: risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcome and the impact of maternal weight gain. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2012;25:2256–2260. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.684176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abhyankar A., Ham M., Moss A.C. Meta-analysis the impact of disease activity at conception on disease activity during pregnancy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013;38:460–466. doi: 10.1111/apt.12417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin H.-C., Chiu C.-C.J., Chen S.-F., Lou H.-Y., Chiu W.-T., Chen Y.-H. Ulcerative colitis and pregnancy outcomes in an Asian population. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010;105:387–394. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hakimian K., Kane S.S., Corley D.A. Pregnancy outcomes in women with inflammatory bowel disease: a large community-based study from Northern California. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1106–1112. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oron G., Yogev Y., Shkolnik S. Inflammatory bowel disease: risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcome and the impact of maternal weight gain. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2012;25:2256–2260. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.684176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]