Abstract

Although many of the effects of estrogens on the brain are mediated through estrogen receptors (ERs), there is evidence that neuroprotective activity of estrogens can be mediated by non-ER mechanisms. Herein, we review the substantial evidence that estrogens neuroprotection is in large part non-ER mediated and describe in vitro and in vivo studies that support this conclusion. Also, we described our drug discovery strategy for capitalizing on enhancement in neuroprotection while at the same time, reducing ER binding of a group of synthetic non-feminizing estrogens. Finally, we offer evidence that part of the neuroprotection of these non-feminizing estrogens is due to enhancement in redox potential of the synthesized compounds.

Keywords: Estrogens, non-feminizing estrogens, neuroprotection, stroke, hormone therapy, estrogen receptors

1. Introduction

Increased risks for cardiovascular disease, stroke, blood clots, breast cancer, and dementia in women on estrogen therapy resulted in the early termination of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). We have since struggled to reconcile these results with the numerous epidemiological, experimental, and clinical studies showing hormone therapy (HT) to be protective against a wide variety of pathological diseased states such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD), cerebrovascular stroke, and cardiovascular diseases (for review see Simpkins et al., 2009). Reevaluations of the WHI and other clinical trials and cohort studies, such as the Nurses’ Health Study, suggest that effects of HT are dependent on post-menopausal stage and the extent of preexisting neurodegenerative or cardiovascular disease at the onset of HT (Dumas et al., 2008; Grodstein et al., 2006; Harman, 2004; Hodis et al., 2003; Sontag et al., 2004). These assessments indicate that younger women may derive neuro- and cardiovascular protection from HT, whereas the initiation of such therapy in older individuals is ineffective or even detrimental (Coker et al., 2009; Dubey et al., 2005; Maki, 2006; Manson et al., 2007; Resnick et al., 2009; Salpeter et al., 2006).

Sex differences in the incidence and outcome of stroke in human subjects suggest that hormonal factors may influence stroke occurrence and damage (Finucane et al., 1993; Paganini-Hill and Henderson, 1996). The severity of ischemic damage in spontaneously hypertensive rats is dependent upon estrogen status (Carswell et al., 2000a,b). While a few studies have shown neutral or negative effects of estrogens (Bingham et al., 2005; Harukuni et al., 2001; Santizo et al., 2002), exogenously administered 17β-estradiol (βE2) is also able to reduce ischemic lesions in animals subjected to middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) (Simpkins et al., 1997a; Dubal et al., 1998; Shi et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2000); estradiol-mediated protection against cerebral ischemia is seen in young (Liao et al., 2001; Simpkins et al., 1997a), middle-aged (Dubal and Wise, 2001), and diabetic rats (Toung et al., 2000), as well as in mice (Dubal et al., 2001) and gerbils (Shughrue and Merchenthaler, 2003). Injury due to MCAO is decreased in rats with either pretreatment with physiological levels of βE2 (Dubal et al., 1998) or with pharmacological post-treatment methods (McCullough et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2000).

The mechanisms of the neuroprotective actions of estrogen are characterized by classical estrogen receptor (ER)-dependent genomic and non-genomic actions. Estrogens have been shown to have an intrinsic antioxidant structure that lies in the phenolic ring of the compounds, which provide the antioxidant/ redox cycling activity in neurons (Prokai et al., 2003a,b). In addition, we have shown that both feminizing and non-feminizing estrogens potentiate L-type VGCC activity (Sarkar et al, 2008). As such, estrogens can have profound effects on neurons that are not dependent on ER interactions.

Many of chronic HT side-effects are most likely due to peripheral effects of orally administered estrogen preparations acting via known ERs (Coker et al., 2009; Dubey et al., 2005; Maki, 2006; Resnick et al., 2009; Salpeter et al., 2006). Several strategies have been undertaken to capitalize on the potent neuroprotective effects of estrogens, while avoiding the side effects of chronic peripheral ER activation. First, selective estrogen receptor modulators are compounds that act as agonists on one ER and antagonists at the other ER (Zandi et al., 2002). This strategy has attempted to enhance ERβ agonist activity while antagonizing ERα (Brinton, 2004; Shelly et al. 2008). The rationale for this approach is that chronic activation of ERα, which is highly expressed in breast, uterus and liver, may account for the known side effects of chronic estrogen administration to post-menopausal women.

An alternative strategy that our laboratory is pursued for nearly two decades is the use of estrogen analogues that do not bind to ERs. This strategy is based on our seminal finding that the ER-α/β ligand βE2 and its presumed inactive diastiomer, αE2, which binds to these ER-isoforms with an approximately 40-fold lower affinity (Perez et al., 2005a,b), were equally potent in protecting neuronal cells and the effects were not blocked by an estrogen antagonist (Green et al., 1997a). This observation prompted a closer evaluation of the structural requirements for neuroprotection among steroids (Behl et al., 1997; Green et al., 1997b), which suggested that estrogen analogues with little ER binding affinity were just as protective as βE2; therefore, we reasoned that a substantial portion of the neuroprotective activity of estrogens was ER-independent.

2. Methods of assessing the estrogen receptor dependence of estrogen effects

There are at least 4 methods that can be used to assess the ER-dependence of effects of estrogens on neuroprotection.

First, the use of a pan-ER antagonist, such as ICI182,780 (ICI), should inhibit compound effects if they are mediated through ERs. ICI has an IC50 of 0.29 nM, and as such is a potent ER antagonist. In many studies, it is used at concentrations 1000-times or greater than its IC50. We observed that ICI 182,780 is extremely neurotoxic to primary cortical neurons, HT-22 cells and SK-N-SH with the lowest dose neurotoxicity seen at 0.3, 0.01 and 0.01 μM in the three cell types, respectively (Perez, et al., Unpublished observations). In view of these data and the low nM IC50 of ICI for ERs, ICI should not be used to assess the ER-dependence of neuronal estrogen responses at concentrations greater than 100 nM, especially when neuroprotection is the measured estrogen response. In addition, ICI has been shown to be neuroprotective (Richardson and Simpkins, 2011; Zhao et al, 2006), complicating the interpretation of data suggesting effects of estrogens are antagonized by ICI.

Second, given that the ED50 of estradiol for both ERα and ERβ is about 2-4 nM, ER-mediated neuroprotection should be seen at compound concentrations at or slightly above this concentration. In most studies, much higher concentrations of βE2 are required to achieve neuroprotection.

For ER-mediated effects, structure-activity relationship studies should reveal that neuroprotection is correlated closely with ER binding for ER-mediated neuroprotection. This is not the case in multiple studies (See Behl et al.1997, Green et al. 1997b, Moosmann and Behl, 1999 and Perez et al, 2005b for example).

Finally, ER-mediated neuroprotection should not be observed in cell types that lack ERs.

3. In vitro evidence for neuroprotection by non-feminizing estrogens

We (Green et al., 1997b) and others (Behl et al., 1997; Moosmann and Behl, 1999) have determined that the phenolic nature of the estradiol molecule is essential for neuroprotection. Therefore, we synthesized estrogen analogues to perform structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies using rationally designed compounds in βE2-neuroprotection assays. Over 70 compounds were tested in HT-22 (murine hippocampal) cells for their ability to inhibit cytotoxicity against glutamate and iodoacetic acid. The EC50 (or IC50) values for neuroprotection, ER binding, and protection against lipid peroxidation were determined to ascertain potency comparisons with βE2 (Perez et al., 2005b). The structures of some of the compounds tested fro neuroprotection are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structures of 17β-estradiol (E2) and several phonic and non-phenolic estrogens assessed fro neuroprotective effects.

Neuroprotective estratrienes that have electron donating constituents increases the redox potential of the phenoxy radical, providing better neuroprotective properties (Perez, et al., 2005b). The donated hydrogen radical can quench free radicals formed in oxidative stress conditions. A-ring derivatives with electron donating constituents that stabilized the phenoxy radical were more potent than βE2 in protecting these cells from oxidative stress-induced toxicity. Our primary synthetic strategy was to replace the hydrogen with a bulky alkyl group at the 2- or 4-positions of the A-ring. For those compounds that included the addition of a single group to the 2-carbon position of the A-ring or 4-carbon position of the A-ring, there was an increase in potency by approximately ~2- to 170-fold as compared to the parent compounds, βE2 and estrone. When two groups flanked the 3-OH position, neuroprotection was enhanced, with approximately 9- and 4-fold decrease in EC50 values for protection against neurotoxicity, respectively. However, C3 methoxy ether analogues of the addition of a single group to the 2-carbon position of the phenolic A-ring that lack an additional phenol substituent, failed to protect cells against toxicity induced cell death. Switching the hydroxyl group to the 2-position and adding bulky groups (1-adamantyl or tert-butyl to the 3-position greatly improved neuroprotective potencies of the parent compound (Perez et al., 2005b).

Introducing conjugated double bonds into the B- or C-rings of estratrienes is another way to increase the stability of the phenoxy radical. Compounds with these modifications were approximately 180- and 490-fold more potent than βE2 against glutamate and IAA toxicity, respectively. Steroids having an aromatic B-ring, similar to conjugated equine estrogens, with intact phenolic hydroxyl groups were more potent against IAA toxicity, but performed equally as well against glutamate toxicity as compared to βE2 (Perez et al., 2005b). Polar groups attached to the B- and C-rings disrupted estrogen’s ability to protect cells from oxidative stress. These hydroxyl groups, which impart hydrophilicity to the molecule, added to the middle of the structure influence the way these steroids fit into the center, hydrophobic lipid bilayer and thus its ability to react with lipid oxidation events. Opening of the B ring causes decreased rigidity of the molecule, but had no effect on the ability of βE2 to protect against IAA-induced cell death and decreased βE2’s ability to protect against glutamate induced cell death by approximately 6- to 12-fold. Producing a nonplanar conformation, such that the A- and B rings lie perpendicular to the C- and D-rings, had no effects on neuroprotection.

D-ring substituents alter lipophilicity; however, the addition of norpregna, norcholesta, benzoate and methylethers to the 17-position did not result in better neuroprotection, instead decreased the potency of the parent compound. Introduction of the side chain found in 25-hydroxycholesterol, a 2-hydroxy-1-methylethyl side chain, spirocyclopentyl groups to the C-16 position did not enhance neuroprotection, possibly due to the fact that the spiro group lies orthoganol to the A-, B-, C-, D-rings and alters the position of the estratriene in the lipid membrane. However, complete removal of a 17-substituent enhanced neuroprotection (Perez et al., 2005b).

These results indicate that protection against toxicity requires a phenolic hydroxyl group. The hydroxy-phenol group does not have to be part of the A-ring since the addition of a hydroxyphenol group to the 3-position was equally or more protective against glutamate and/or IAA-induced toxicities. This and the fact that the nonsteroidal compounds with phenolic groups are still protective demonstrate that the position of the hydroxyl phenol group is not restricted to the 3-position of the steroid backbone. In concert with glutathione, estrogens were also potent neuroprotectants (in the nanomolar range) againstAβ(25–35) toxicity in SK-N-SH (Gridley et al., 1998) and HT-22 cells (Green et al., 1998). All of these structure-activity studies found that the phenolic A-ring was an absolute requirement for neuroprotection, as compounds such as mestranol and quinestrol did not have protect effects. That EC50 values seen with some of the more potent compounds were in the low nanomolar range is the key for therapeutic purposes.

Other estrogen-like substances, such as conjugated equine estrogens (Zhao et al., 2003), phytoestrogens (Gelinas and Martinoli, 2002; Roth et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2001), and estrogen metabolites (2-OHestradiol) (Teepker et al., 2003) were also found to be neuroprotective, although not as potent as the compounds screened in our studies.

In summary, a critical feature of the estradiol structure and the stabilization of the phenoxy radical state has been identified that increased the potency against oxidative stress damage; thus, advancing our understanding of estrogen-mediated neuroprotection.

4. Estrogen Protection in a Friedreich’s Ataxia Model

Recently, we have shown that estrogen-like compounds, including a group of non-feminizing estrogens, can protect an in vitro Friedreich’s Ataxia (FRDA) cell model against oxidative stress (Richardson et al., 2011). In this model, human FRDA skin fibroblasts are treated with L-buthionine (S,R)-sulfoximine (BSO) to inhibit de novo glutathione (GSH) synthesis, increasing the susceptibility of the cells to oxidative damage induced by naturally occurring reactive oxygen species (ROS). Previous studies have shown that FRDA fibroblasts are especially vulnerability to this treatment, while normal fibroblasts are not (Jauslin et al., 2002; Jauslin et al., 2003). Our results demonstrate that in this cell type, estrogens act in a manner independent of any known ER to produce their potent protective effects. Consistent with previous reports (Behl et al., 1997; Green et al., 1997b; Moosmann and Behl, 1999; Perez et al., 2005b; Prokai et al., 2003a), the potency and efficacy of these estrogen-like compounds was dependent on the presence of at least one phenol ring in its structure, and in this cell model the potency seems to be directly correlated to the number of phenol rings in the compound (Richardson et al., 2011).

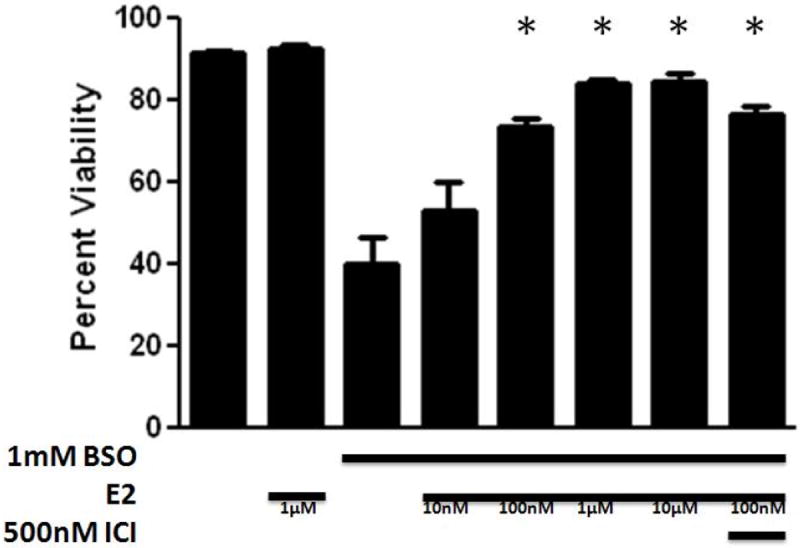

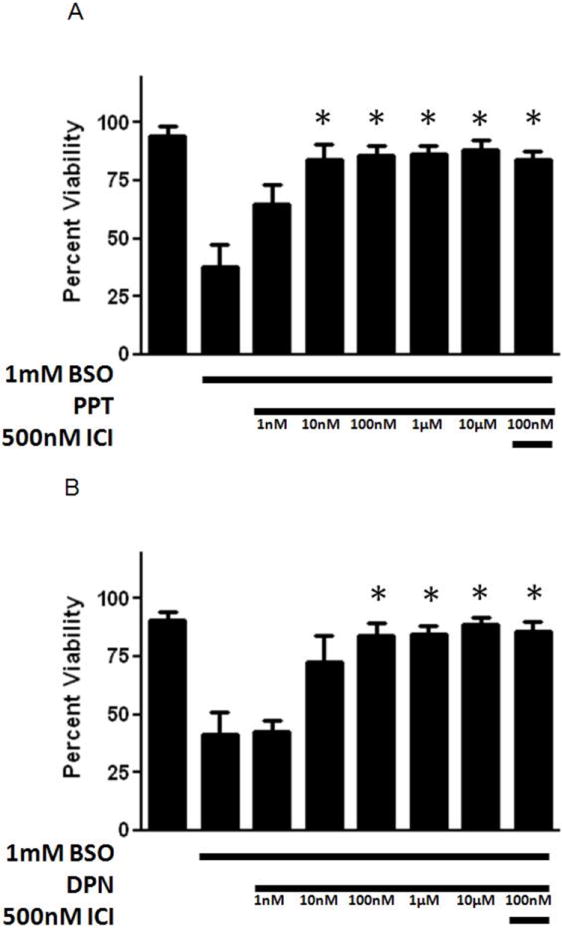

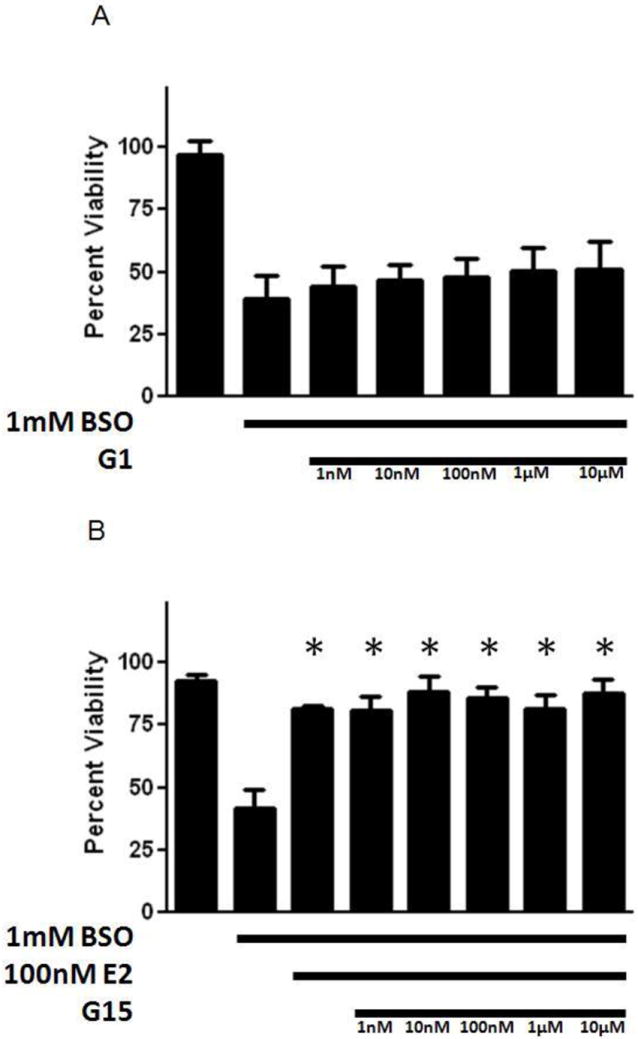

βE2, which contains a single phenol ring (Fig. 1), provided protection across a wide range of concentrations (Fig. 2) with an EC50 of 15.5 nM, and this effect was not significantly inhibited by the co-application of ICI. The 3 phenol ring containing ERα selective agonist 4,4’,4’-(4-Propyl-[1H]-pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl)trisphenol (PPT) and the 2 phenol ring containing ERβ selective agonist diarylpropionitrile (DPN) similarly provided protection in the very low nM range, with EC50 values of 4.6 nM and 9.3 nM, respectively (Fig. 3). Again, these compounds were not antagonized by ICI. The non-feminizing estrogen 2-(1-adamantyl)-4-methylestrone (ZYC-26; Fig. 1), a compound with one phenol ring, but no ER binding ability due to the presence of an adamantyl group, was also potently cytoprotective in this system, with an EC50 of 23.1 nM (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the non-feminizing estrogen 2-adamantyl, 3-O-methyl estradiol (ZYC-23; Fig. 1), which is very similar in structure to ZYC-26, with the phenol group replaced by an O-methyl group, had no significant protective effect (Fig. 4B). In addition, the membrane ER (mER) G protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30) agonist, G1, had no significant protective effect (Fig. 5A) and the GPR30 antagonist G15 over a concentration range of 1nM – 10 μM was unable to inhibit the protective effect of 100 nM βE2 (Fig. 5B). These results are consistent with data showing that the level of ROS attenuation in this FRDA cell system is directly correlated to the presence and number of phenol rings present in the compound, substantiating the hypothesis that in the FRDA fibroblast model it is the phenol ring and its antioxidant potential that is the essential part of the estrogen molecule in terms of neuroprotection (Richardson et al., 2011).

Figure 2.

Effects of 17β-estradiol (E2) on cell viability in BSO-treated FRDA fibroblasts. Depicted are mean ± 1 SD for n= 8 per group. * indicated p<0.05 versus BSO alone-treated cells. ICI indicated ICI 182,780. Republished from Richardson et al., 2011, with permission.

Figure 3.

Effects of an ERα preferring agonist, PPT (A), and an ERβ preferring agonist DPN, (B) on cell viability in BSO-treated FRDA fibroblasts. Depicted are mean ± 1 SD for n= 8 per group. * indicated p<0.05 versus BSO alone-treated cells Republished from Richardson et al., 2011, with permission.

Figure 4.

Effects of non-feminizing estrogens on cell viability in BSO-treated FRDA fibroblasts. Depicted are mean ± 1 SD for n= 8 per group. * indicated p<0.05 versus BSO alone-treated cells. ICI indicates ICI 182,780. ZYC-26 (A) indicates 2-adamantyl, 4 methyl estrone. ZYC-23 (B) indicates 2-adamantyl, 3-0-methyl estradiol. Republished from Richardson et al., 2011, with permission.

Figure 5.

Effects of the membrane ER-preferring agonist, G1 (A), on cell viability in BSO-treated FRDA fibroblasts, and effects of the membrane ER-preferring antagonist, G15 (B), on E2-induced enhancement of cell viability in BSO-treated FRDA fibroblasts. Depicted are mean ± 1 SD for n= 8 per group. * indicated p<0.05 versus BSO alone-treated cells. Republished from Richardson et al., 2011, with permission.

These data clearly indicate that βE2 and estrogen-like drugs are capable of acting independently of ERα, ERβ or GPR30, as long as at least one phenol ring is present in the molecular structure in this cell model. All tested phenolic estrogens were able to protect the FRDA fibroblasts from BSO-induced oxidative stress, ultimately preventing significant cell death, while the non-phenolic estrogens tested were not. This cell model provides evidence and support for the use of non-feminizing estrogens to potently protect cells and tissues from stressors commonly associated with neurodegenerative diseases.

5. In vivo evidence for neuroprotection by non-feminizing estrogens

Both endogenous and exogenous βE2 administration attenuate infarct volume and are neuroprotective against the pathological events seen in experimental animal models of cerebral ischemia (Green et al., 1996, 1997a,b, 1998; Gridley et al., 1997; Alkayed et al., 1998; Dubal et al., 1998; Green and Simpkins, 2000; Green et al., 2001; Simpkins et al., 2005; Sudo et al., 1997; Yang et al., 2000). We selected several of our estratrienes for in vivo assessment against a routinely used model of cerebral ischemia, transient MCAO, in ovariectomized rats. To date, we have assessed eight compounds in this model, including βE2, estrone, αE2, ent-E2, enantiomer of 17-desoxyestradiol (ZYC-13), 2-(1-adamantyl) estrone (ZYC-3), 2-(1-adamantyl)-4-methylestrone (ZYC-26), and 3-O-methyl analog of (17beta)-2-(1-adamantyl)estradiol (ZYC-23). Consistent with our in vitro studies, βE2, estrone, αE2, ent-E2, enantiomer of 17-desoxyestradiol (ZYC- 13), 2-(1-adamantyl) estrone (ZYC-3), and 2-(1-adamantyl)-4- methylestrone (ZYC-26) exert potent neuroprotective effects in focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury (Fan et al., 2001; Green et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2002; Simpkins et al., 1997b, 2004). Subcutaneously implantation of αE2 24 hours before MCA occlusion showed neuroprotective effects (Simpkins et al., 1997b) even though αE2 binds to ER-isoforms with an approximately 40-fold lower affinity (Perez et al., 2005a). Two-hour pretreatment with E1 before the onset of transient MCA occlusion significantly reduced infarct volume compared with vehicle control following 24-hour reperfusion in ovariectomized rats. The quinol-conjugated E1 was equipotent with the parent estrogen in reducing lesion. Ent-E2, which has shown to be less than one-eighth as active as βE2 in competitive bind assays for human recombinant ERα and ERβ, is as effective as βE2 in reducing infarct size after MCA occlusions. There was no evidence of metabolic conversion of ent-E2 to βE2 in ovariectomized rats and no uterotropic response to 3 days of administration (Green et al., 2001). These data suggests that non-feminizing enantiomers of estrogens can be potently neuroprotective from human ischemic brain damage. ZYC-3 showed no binding to either ERα or ERβ in competitive binding assays but was 6-times more potent than βE2 in a test for neuroprotection against glutamate toxicity. Further, in our in vivo model of transient MCA occlusion, ZYC-3 performed better than βE2 without affecting physiological parameters (Liu et al., 2002). The placement of a bulky adamantly group in the 2-position of the A-ring of the estrone eliminates estrogenicity, enhances antioxidant potential (Perez et al., 2005b), and enhances the potent neuroprotective activity of estrogens against ischemic brain damage. ZYC-26 has an adamantly moiety on the 2-carbon and a methyl group on the 4 carbon of estrone. ZYC-23 is similar, but the phenolic nature of the A-ring is eliminated through O-methylation of the 3-carbon, a chemical change that completely eliminate neuroprotection of estrogens (Simpkins et al., 2004). Neither of these compounds binds to either estrogen receptor. Similar to our in vitro study, ZYC-26 reduced lesion volume. As expected, no protective effects of ZYC-23 were seen in vitro or after transient MCA occlusion.

6. Future Directions

Having been extensively tested in in vitro and in vivo models for stroke, there is a need to conduct pharmacokinetic assessments of one or more of the most potent estrogen analogues and to begin to formulate these compounds for future clinical studies. Since these activities are not competitive for NIH funding, pharmaceutical support for a drug development program on non-feminizing estrogens for neuroprotection is needed.

7. Summary and conclusions

We are actively pursuing the optimization of estrogen analogues that do not bind ERs, but which are more potent neuroprotectants than βE2. This program has demonstrated that estrogen analogues with large bulky groups at the 2 and/ or 4 carbon of the phenolic A ring eliminate ER binding but enhance neuroprotective potency in cell culture screening systems. These A-ring derivatives work in part by increased electron donating capacity that stabilized the phenoxy radical. Our estrogen analogues are also potent neuroprotectants in an animal model of cerebral ischemia. Studies are in progress to understand the mechanism by which these analogues are neuroprotective. The discovery of these non-feminizing estrogens opens the possibility of making these compounds more “drug-able” and thereby producing nonfeminizing estrogens that can achieve the beneficial effects of estrogens without the unwanted side-effect related to interaction with ERs. Such an achievement could markedly change our approach to postmenopausal HT, as well as treatment of brain injuries.

Highlights.

Estrogens have been shown to have an intrinsic antioxidant structure that lies in the phenolic ring of the compounds, which provide the antioxidant/ redox cycling activity in neurons.

We and others have determined that the phenolic nature of the estradiol molecule is essential for neuroprotection.

Synthetic neuroprotective estrogens that have electron donating constituents increases the redox potential of the phenoxy radical, providing better neuroprotective properties.

We have shown that estrogen-like compounds, including a group of non-feminizing estrogens, can protect an in vitro Friedreich’s Ataxia (FRDA) cell model against oxidative stress.

Both endogenous and exogenous estradiol administration attenuates infarct volume and is neuroprotective against the pathological events seen in experimental animal models of cerebral ischemia.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants P01 AG10485, P01 AG22550 and P01 AG27956. TER is support by NIA training Grant T32 AG020494

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alkayed NJ, Harukuni I, Kimes AS, London ED, Traystman RJ, Hurn PD. Gender-linked brain injury in experimental stroke. Stroke. 1998;29:159–165. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behl C, Skutella T, Lezoualc’h F, Post A, Widmann M, Newton CJ, Holsboer F. Neuroprotection againstoxidative stress by estrogens: structure–activity relationship. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:535–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham D, Macrae IM, Carswell HV. Detrimental effects of 17β-oestradiol after permanent middle cerebral artery occulsion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:414–420. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton RD. Requirements of a brain selective estrogen: advances and remaining challenges for developing a NeuroSERM. J Alzheimers Dis. 2004;6:S27–S35. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6s607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carswell HV, Anderson NH, Morton JJ, McCulloch J, Dominiczak AF, Macrae IM. Investigation of estrogen status and increased stroke sensitivity on cerebral blood flow after a focal ischemic insult. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000a;20:931–936. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200006000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carswell HV, Dominiczak AF, Macrae IM. Estrogen status affects sensitivity to focal cerebral ischemia in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000b;278:H290–H294. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.1.H290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker LH, Hogan PE, Bryan NR, Kuller LH, Margolis KL, Bettermann K, Wallace RB, Lao Z, Freeman R, Stefanick ML, Shumaker SA. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and subclinical cerebrovascular disease: the WHIMS-MRI Study. Neurology. 2009;72:125–134. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000339036.88842.9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal DB, Kashon ML, Pettigrew LC, Ren JM, Finklestein SP, Rau SW, Wise PM. Estradiol protects against ischemic injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:1253–1258. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal DB, Wise PM. Neuroprotective effects of estradiol in middle-aged female rats. Endocrinology. 2001;142:43–48. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.1.7911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal DB, Zhu H, Yu J, Rau SW, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, Kindy MS, Wise PM. Estrogen receptor alpha, not beta, is a critical link in estradiol-mediated protection against brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1952–1957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041483198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey RK, Imthurn B, Barton M, Jackson EK. Vascular consequences of menopause and hormone therapy: importance of timing of treatment and type of estrogen. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas J, Hancur-Bucci C, Naylor M, Sites C, Newhouse P. Estradiol interacts with the cholinergic system to affect verbal memory in postmenopausal women: evidence for the critical period hypothesis. Horm Behav. 2008;53:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan T, Perez EJ, Eberst KL, Covey DF, Chen HX, Day AL, Simpkins JW. ZYC-13, the enantiomer of 1, 3, 5(10)-estratriene 3-ol, exerts neuroprotective effects in vitro and in vivo. Society for Neuroscience. 2001 Abstract A 27. [Google Scholar]

- Finucane FF, Madans JH, Bush TL, Wolf PH, Kleinman JC. Decreased risk of stroke among postmenopausal hormone users. Results from a national cohort. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:73–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelinas S, Martinoli MG. Neuroprotective effect of estradiol and phytoestrogens on MPP+-induced cytotoxicity in neuronal PC12 cells. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:90–96. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PS, Gridley KE, Simpkins JW. Estradiol protects against beta-amyloid (25-35)-induced toxicity in SK-N-SH human neuroblastoma cells. Neurosci Lett. 1996;218:165–168. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PS, Bishop J, Simpkins JW. 17 alpha-estradiol exerts neuroprotective effects on SK-N-SH cells. J Neurosci. 1997a;17:511–515. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00511.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PS, Gordon K, Simpkins JW. Phenolic A ring requirement for the neuroprotective effects of steroids. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1997b;63:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(97)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PS, Gridley KE, Simpkins JW. Nuclear estrogen receptor-independent neuroprotection by estratrienes: a novel interaction with glutathione. Neuroscience. 1998;84:7–10. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00595-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PS, Simpkins JW. Neuroprotective effects of estrogens: potential mechanisms of action. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2000;18:347–358. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(00)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PS, Yang SH, Nilsson KR, Kumar AS, Covey DF, Simpkins JW. The nonfeminizing enantiomer of 17beta-estradiol exerts protective effects in neuronal cultures and a rat model of cerebral ischemia. Endocrinology. 2001;142:400–406. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.1.7888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley KE, Green PS, Simpkins JW. Low concentrations of estradiol reduce beta-amyloid (25-35)-induced toxicity, lipid peroxidation and glucose utilization in human SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. 1997;778:158–165. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley KE, Green PS, Simpkins JW. A novel, synergistic interaction between 17 beta-estradiol and glutathione in the protection of neurons against beta-amyloid 25-35-induced toxicity in vitro. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:874–880. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.5.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodstein F, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ. Hormone therapy and coronary heart disease: the role of time sincemenopause and age at hormone initiation. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15:35–44. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall ED, Pazara KE, Linseman KL. Sex differences in postischemic neuronal necrosis in gerbils. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1991;11:292–298. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman SM. What do hormones have to do with aging? What does aging have to do with hormones? Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1019:299–308. doi: 10.1196/annals.1297.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harukuni I, Hurn PD, Crain BJ. Deleterious effect of 17β-estradiol in a rat model of transient forebrain ischemia. Brain Res. 2001;900:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Lobo RA. Randomized controlled trial evidence that estrogen replacement therapy reduces the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in healthy postmenopausal women without preexisting cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2003;108:e5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080080.76333.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauslin ML, Wirth T, Meier T, Shoumacher F. A cellular model for Friedreich Ataxia reveals small-molecule glutathione peroxidase mimetics as novel treatment strategy. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:3055–3063. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.24.3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauslin ML, Meier T, Smith RA, Murphy MP. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants protect Friedreich Ataxia fibroblasts from endogenous oxidative stress more effectively than untargeted antioxidants. FASEB J. 2003;17:1972–1974. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0240fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao S, Chen W, Kuo J, Chen C. Association of serum estrogen level and ischemic neuroprotection in female rats. Neurosci Lett. 2001;297:159–162. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01704-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Yang SH, Perez E, Yi KD, Wu SS, Eberst K, Prokai L, Prokai-Tatrai K, Cai ZY, Covey DF, Day AL, Simpkins JW. Neuroprotective effects of a novel non-receptor-binding estrogen analogue: in vitro and in vivo analysis. Stroke. 2002;33:2485–2491. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000030317.43597.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki PM. Potential importance of early initiation of hormone therapy for cognitive benefit. Menopause. 2006;13:6–7. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000194822.76774.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson JE, Allison MA, Rossouw JE, Carr JJ, Langer RD, Hsia J, Kuller LH, Cochrane BB, Hunt JR, Ludlam SE, Pettinger MB, Gass M, Margolis KL, Nathan L, Ockene JK, Prentice RL, Robbins J, Stefanick ML. Estrogen therapy and coronary-artery calcification. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2591–2602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough LD, Alkayed NJ, Traystman RJ, Williams MJ, Hurn PD. Postischemic estrogen reduces hypoperfusion and secondary ischemia after experimental stroke. Stroke. 2001;32:796–802. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.3.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosmann B, Behl C. The antioxidant neuroprotective effects of estrogens and phenolic compounds are independent from their estrogenic properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8867–8872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paganini-Hill A, Henderson VW. Estrogen replacement therapy and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2213–2217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez E, Liu R, Yang SH, Cai ZY, Covey DF, Simpkins JW. Neuroprotective effects of an estratriene analog are estrogen receptor independent in vitro and in vivo. Brain Res. 2005a;1038:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez E, Cai Zu, Covey Yun, Douglas F, Simpkins James W. Neuroprotective effects of estratriene analogs: structure–activity relationships and molecular optimization. Drug Dev Res. 2005b;66:78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Prokai L, Prokai-Tatrai K, Perjesi P, Zharikova AD, Perez EJ, Liu R, Simpkins JW. Quinol-based cyclic antioxidant mechanism in estrogen neuroprotection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003a;100:11741–11746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2032621100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokai L, Prokai-Tatrai K, Perjesi P, Zharikova AD, Simpkins JW. Quinol-based metabolic cycle for estrogens in rat liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003b;31:701–704. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SM, Espeland MA, Jaramillo SA, Hirsch C, Stefanick ML, Murray AM, Ockene J, Davatzikos C. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and regional brain volumes: the WHIMS-MRI Study. Neurology. 2009;72:135–142. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000339037.76336.cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson TE, Yang SH, Wen Y, Simpkins JW. Estrogen protection in Friedreich’s ataxia skin fibroblasts. Endocrinology. 2011;152:2742–2749. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A, Schaffner W, Hertel C. Phytoestrogen kaempferol (3, 4′, 5, 7-tetrahydroxyflavone) protects PC12 and T47D cells from beta-amyloid-induced toxicity. J Neurosci Res. 1999;57:399–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salpeter SR, Walsh JM, Greyber E, Salpeter EE. Brief report: Coronary heart disease events associated with hormone therapy in younger and older women. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:363–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santizo RA, Xu HL, Ye S, Baughman VL, Pelligrino DA. Loss of benefit from estrogen replacement therapy in diabetic ovariectomized female rats subjected to transient forebrain ischemia. Brain Res. 2002;956:86–95. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03484-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Huang R-Q, Logan S, Dillon GH, Simpkins JW. Estrogens directly potentiate neuronal L-type Ca2 channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2008;105:15148–15153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802379105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelly W, Draper MW, Krishnan V, Wong M, Jaffe RB. Selective estrogen receptor modulators: an update on recent clinical findings. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2008;63:163–181. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e31816400d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Bui JD, Yang SH, He Z, Lucas TH, Buckley DL, Blackband SJ, King MA, Day AL, Simpkins JW. Estrogens decrease reperfusion-associated cortical ischemic damage: an MRI analysis in a transient focal ischemia model. Stroke. 2001;32:987–992. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I. Estrogen prevents the loss of CA1 hippocampal neurons in gerbils after ischemic injury. Neuroscience. 2003;116:851–861. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00790-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkins JW, Green PS, Gridley KE, Singh M, de Fiebre NC, Rajakumar G. Role of estrogen replacement therapy in memory enhancement and the prevention of neuronal loss associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Med. 1997a;103:19S–25S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkins JW, Rajakumar G, Zhang YQ, Simpkins CE, Greenwald D, Yu CJ, Bodor N, Day AL. Estrogens may reduce mortality and ischemic damage caused bymiddle cerebral artery occlusion in the female rat. J Neurosurg. 1997b;87:724–730. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.5.0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkins JW, Yang SH, Liu R, Perez E, Cai ZY, Covey DF, Green PS. Estrogen-like compounds for ischemic neuroprotection. Stroke. 2004;35:2648–2651. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000143734.59507.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkins JW, Wang J, Wang X, Perez E, Prokai L, Dykens JA. Mitochondria play a central role in estrogen-induced neuroprotection. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2005;4:69–83. doi: 10.2174/1568007053005073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkins JW, Perez E, Wang X, Yang S, Wen Y, Singh M. The potential for estrogens in preventing Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2009;2:31–49. doi: 10.1177/1756285608100427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontag E, Luangpirom A, Hladik C, Mudrak I, Ogris E, Speciale S, White CL., III Altered expression levels of the protein phosphatase 2A ABalphaC enzyme are associated with Alzheimer disease pathology. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:287–301. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudo S, Wen TC, Desaki J, Matsuda S, Tanaka J, Arai T, Maeda N, Sakanaka M. Beta-estradiol protects hippocampal CA1 neurons against transient forebrain ischemia in gerbil. Neurosci Res. 1997;29:345–354. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(97)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teepker M, Anthes N, Krieg JC, Vedder H. 2-OH-estradiol, an endogenous hormone with neuroprotective functions. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:517–523. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toung TK, Hurn PD, Traystman RJ, Sieber FE. Estrogen decreases infarct size after temporary focal ischemia in a genetic model of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Stroke. 2000;31:2701–2706. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.11.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CN, Chi CW, Lin YL, Chen CF, Shiao YJ. The neuroprotective effects of phytoestrogens on amyloid beta protein-induced toxicity are mediated by abrogating the activation of caspase cascade in rat cortical neurons. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5287–5295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006406200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SH, Shi J, Day AL, Simpkins JW. Estradiol exerts neuroprotective effects when administered after ischemic insult. Stroke. 2000;31:745–749. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.745. discussion 749-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandi PP, Carlson MC, Plassman BL, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Mayer LS, Steffens DC, Breitner JC. Hormone replacement therapy and incidence of Alzheimer disease inolder women: the Cache County Study. JAMA. 2002;288:2123–2129. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, O’Neill K, Brinton RD. Estrogenic agonist activity of ICI 182,780 (Faslodex) in hippocampal neurons: implications for basic science understanding of estrogen signaling and development of estrogen modulators with a dual therapeutic profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:1124–1132. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.109504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]