Abstract

Background

The presence of multiple molecular aberrations in patients with breast cancer may correlate with worse outcomes.

Case Presentations

We performed in-depth molecular analysis of patients with estrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, hormone therapy-refractory breast cancer, who achieved partial or complete responses when treated with anastrozole and everolimus. Tumors were analyzed using a targeted next generation sequencing (NGS) assay in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments laboratory. Genomic libraries were captured for 3,230 exons in 182 cancer-related genes plus 37 introns from 14 genes often rearranged in cancer and sequenced to high coverage. Patients received anastrozole (1 mg PO daily) and everolimus (5 or 10 mg PO daily). Thirty-two patients with breast cancer were treated on study and 5 (16 %) achieved a partial or complete response. Primary breast tissue was available for NGS testing in three of the responders (partial response with progression free survival of 11 and 14 months, respectively; complete response with progression free survival of 9+ months). The following molecular aberrations were observed: PTEN loss by immunohistochemistry, CCDN1 and FGFR1 amplifications, and PRKDC re-arrangement (NGS) (patient #1); PIK3CA and PIK3R1 mutations, and CCDN1, FGFR1, MYC amplifications (patient #2); TP53 mutation, CCNE1, IRS2 and MCL1 amplifications (patient #3). Some (but not all) of these aberrations converge on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, perhaps accounting for response.

Conclusions

Patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer can achieve significant responses on a combination of anastrozole and everolimus, even in the presence of multiple molecular aberrations. Further study of next generation sequencing-profiled tumors for convergence and resistance pathways is warranted.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12885-015-1439-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Genomic aberrations, Next generation sequencing

Background

Gene aberrations including, but not limited to, mutations, amplifications and rearrangements drive tumor growth. Aberrations are common in breast cancer in genes such as HER2 (ERBB2), BRCA, PIK3CA, TP53, GATA3, PTEN and others [1–6]. The presence of multiple gene abnormalities may also serve as an indicator of genetic instability and therefore of poor patient prognosis [7, 8].

Hormone therapy is the treatment of choice for estrogen (ER) and progesterone (PR)-positive breast cancer, but acquired resistance is a significant challenge. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway becomes activated and utilized by cancer cells to bypass the effects of endocrine therapy [9–11]. While investigating the combination of anastrozole (an aromatase inhibitor that blocks estrogen production) and everolimus (an mTOR inhibitor), we noted partial or complete responses (PR or CR) with progression-free survival (PFS) of at least 9 months in five patients with breast cancer of 32 treated [12]. We performed next-generation sequencing (NGS) on three of the responders with available tissue. In depth analysis revealed that, despite their responses, their tumors demonstrated multiple aberrations in genes including CCND1, CCNE1, FGFR1, MYC, IRS2, MCL1, PIK3CA, PIK3R1, PRKDC, and TP53. The implications of these diverse aberrations for understanding response and resistance are discussed.

Case Presentations

At the time of analysis, 32 patients with advanced breast cancer were treated with anastrozole and everolimus, and five attained PR or CR with PFS of at least nine months [12]. In depth analysis was performed using NGS on three responders with available tissue (number of prior therapies = 2, 4, and 7, respectively, in the metastatic setting) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics and Responses of Super-Responders Treated with Anastrozole and Everolimus

| Patient No. | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Treatment (years) | 38 | 48 | 44 |

| Date of Diagnosis | August 2009 | September 2007 | September 2010 |

| Date of Biopsy | August 2009 | September 2007 | August 2010 |

| Histology | Ductal | Ductal | Ductal |

| ER Status | 90 % Positive | 95 % Positive | 95 % Positive |

| PR Status | 60 % Positive | 80 % Positive | Negative |

| HER2/neu Status | Negative (FISH) | Negative (FISH) | Negative (IHC) |

| Prior Treatment in Metastatic Setting | Paclitaxel (3 months) 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide (1 month) Tamoxifen (3 months) Capacitabine ( 3 months) | Tamoxifen (2 months) Paclitaxel, bevacizumaba Vinorelbinea Fulvestrant (3 months) Ixabepilonea Docetaxel (9 months) Docetaxel, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide (3 months) | Tamoxifen, zoledronic acid (6 months) Letrozole (4 months) |

| Prior Treatment with Aromatase Inhibitor in Metastatic Setting (Duration) | No | No | Yes (4 months) |

| Molecular alterations (Please reference Additional file 1: Table S1) | |||

| Progression Free Survival (months) | 11 | 14 | 9+ |

| Best Response (%) | −56 % | −38 % | −100 % |

aUnknown duration of treatment

FISH Fluorescent in-situ hybridization, IHC Immunohistochemistry

Patient #1 is a 38-year old woman with ER-positive (90 %), PR-positive (60 %), HER2-negative, invasive ductal carcinoma diagnosed in August 2009. The patient was referred to the Clinical Center for Targeted Therapy at MD Anderson Cancer Center in February 2011. Previous therapies in the metastatic setting included: (1) paclitaxel; (2) 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide; (3) tamoxifen; and (4) capecitabine. Immunohistochemistry revealed complete nuclear PTEN loss. NGS of left breast tumor tissue dated August 2009 revealed amplifications in CCDN1 and FGFR1 in addition to a rearrangement in PRKDC.

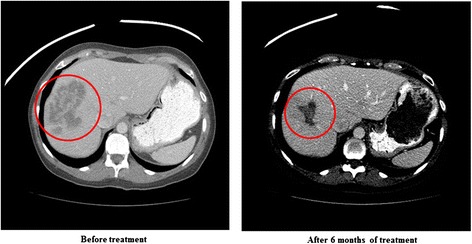

The patient was treated with anastrozole 1 mg PO daily and everolimus 5 mg PO daily beginning March 2011. She attained a PR (56 % decrease in liver metastases) (Fig. 1) and remained on study for 11 months.

Fig. 1.

Patient #1 CAT scans of the abdomen show a partial response (56 % decrease in hepatic disease) after 6 months of treatment. Patient received treatment for 11 months before progressing

Patient #2 is a 48-year old woman with ER-positive (95 %), PR-positive (80 %), HER2- negative, invasive ductal carcinoma diagnosed in September 2007. At that time, metastatic disease was found in the pleura and bones. The patient was referred to our clinic in March 2011. Previous therapies in the metastatic setting included: (1) tamoxifen; (2) paclitaxel with bevacizumab; (3) vinorelbine; (4) fulvestrant; (5) ixabepilone; (6) docetaxel; and (7) docetaxel, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. Immunohistochemistry showed PTEN to be present. NGS of malignant tissue from the left breast dated September 2007 revealed mutations in PIK3CA and PIK3R1 in addition to amplifications in CCDN1, FGFR1 and MYC.

The patient was treated with anastrozole 1 mg PO daily and everolimus 5 mg PO daily starting March 2011. She achieved a PR (38 % decrease in measureable disease). After 14 months on study, she showed signs of progression. At that time, a third agent, fulvestrant (an estrogen receptor antagonist) was added as per protocol for triple combination therapy. Five months later, she continues on this triple-agent treatment.

Patient #3 is a 44-year old woman with ER-positive (>95 %), PR-negative, HER2-negative, invasive ductal carcinoma diagnosed in September 2010. The patient was referred to our clinic in October 2011. Previous therapies in the metastatic setting included: (1) tamoxifen with zoledronic acid and (2) letrozole (progression free survival = 4 months). Immunohistochemistry showed intact PTEN. NGS of tissue from the primary left breast tumor at the time of diagnosis revealed a mutation in TP53 and amplifications in CCNE1, IRS2 and MCL1.

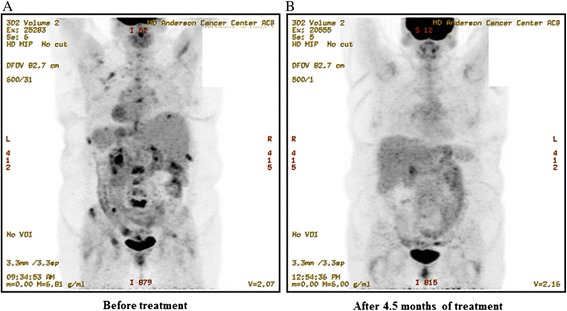

The patient was treated with anastrozole 1 mg PO daily and everolimus 10 mg PO daily. At the time of treatment her metastatic disease was only in bone. She achieved a CR noted on PET/CT (Fig. 2) (time on study = 9+ months).

Fig. 2.

Patient #3 PET scans show metastatic bone disease that attained a complete metabolic response after 4.5 months of treatment. Patient remained on treatment after 9 months at the time of this analysis

We present an in-depth analysis of three patients with advanced, refractory breast cancer who attained remarkable responses despite the fact that their tumors harbored multiple gene alterations (Additional file 1: Table S1). Of interest, in each case, despite the complexity of aberrations revealed by NGS, many of the molecular abnormalities can be shown to converge, at least in part, on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis, perhaps accounting for the responses. On the other hand, some of the genes involved also modulate other pathways, and this fact may explain why two of the patients attained only partial responses, and eventually relapsed.

In patient #1, who had ER/PR-positive disease, abnormalities included: PTEN loss; CCDN1 and FGFR1 amplifications and a re-arrangement in PRKDC. Yet, she achieved a durable PR on anastrozole and everolimus. PTEN loss is known to activate the PI3K pathway [13], which might easily explain the response to the mTOR inhibitor everolimus. Of interest, however, the other aberrant genes detected in this patient’s tumor might also affect this pathway. For instance, CCND1, also known as BCL1, is down regulated by mTOR inhibition [14, 15]. FGFR1 encodes a tyrosine kinase receptor belonging to fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) family; this gene is amplified in 9 to 15 % of breast cancers [16–18]. Activation of FGFR induces PI3K and AKT pathway activity through recruitment and tyrosine phosphorylation of the docking protein Gab [19]. Finally, PRKDC was rearranged in patient #1. This gene is a member of the PI3K family and encodes the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK). It functions with the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer protein in DNA double strand break repair and recombination [20]. Overall, though there were several different aberrations in this patient, each has some impact on PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. Yet, some of the aberrations (e.g., FGFR1) also activate other signaling pathways such as MAP kinase [21], which might explain why complete response was not attained and/or the eventual progression that developed after 11 months.

In patient #2, who also achieved a durable PR (14 months) on anastrozole and everolimus, multiple aberrations were seen as well. NGS of malignant tissue revealed mutations in PIK3CA and PIK3R1, in addition to amplifications in CCDN1, FGFR1 and MYC. Responses of patients with PIK3CA-mutant breast, gynecologic and other tumors to mTOR inhibitors has been previously reported [3, 22–26]. The crosstalk between CCND1 and FGFR1 (both amplified in this patient) and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway has been discussed above. MYC encodes a transcription factor with multiple functions,[27] including interaction with the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis as evidenced by the observation that MYC-induced proliferation and transformation require AKT-mediated phosphorylation of FoxO proteins [28]. Of interest, both this patient and patient #1 harbored FGFR1 aberrations and, as mentioned, FGFR1 can activate both PI3K and MAPK signals, hence potentially explaining both initial response to everolimus (via PI3K activation) and eventual resistance (via MAPK). MYC might also play a role in limiting the response of this patient to less than a CR, since MYC regulates expression of a broad array of genes via its functions as a transcription factor, transcriptional repressor, and regulator of global chromatin structure by means of recruitment of histone acetyltransferases [29].

Patient #3, who attained a CR on therapy, demonstrated a mutation in TP53 and amplifications in CCNE1, IRS2 and MCL1. TP53 is a regulator of PTEN, which is in itself a negative regulatory of PIK3CA [30]. CCNE1 degradation is regulated by GSK-3β, which is directly phosphorylated by AKT [31, 32]. Insulin receptor substrates (IRS) serve as downstream messengers from activated cell surface receptors to numerous signaling pathway cascades including PI3K [33]. Finally, mTORC1 promotes survival in part through translational control of MCL-1 [34]. Previous studies have demonstrated up-regulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway as a mechanism of resistance to hormone therapy [35–40], and clinical trials combining hormone therapy with mTOR inhibitors have shown promise in breast and endometrial cancers [41–43]. Further, the combination of exemestane (an aromatase inhibitor) and everolimus was FDA approved for metastatic breast cancer. Other possibilities for the response in this patient may be the effect of anastrazole or the development of new molecular alterations since the primary diagnosis as molecular profiling was done on primary breast tissue.

In our study of anastrozole and everolimus in hormone receptor-positive breast cancers we observed salutary activity in patients with multiple gene aberrations. Patient #1 and Patient #2 demonstrated direct alterations in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (PTEN loss and PIK3CA mutation, respectively) in addition to multiple gene amplifications and additional rearrangements or mutations. It is therefore plausible that these patients responded because their tumors maintained dependence on or addiction to the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis despite the presence of additional gene alterations. Recently, Hortobagyi et al. [25] reported that patients treated on the Phase 2 BOLERO-2 study had a greater treatment effect if they had no or only 1 genetic alteration in PI3K or FGFR pathways or CCND1. Some of the additional molecular alterations demonstrated by NGS in our patients may however also modulate the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis, as noted above, explaining our findings. Systems biology approaches that map convergence pathways may therefore enhance treatment for patients [5, 6, 44, 45]. Alternatively, an eventual relapse (and in patients #1 and #2, partial, rather than complete, response) could be the result of the actions of the additional molecular alterations. Of interest, at the time of progression, fulvestrant, an estrogen receptor antagonist, was added to anastrozole and everolimus in patient #2, with a 5+ month disease stabilization. This strategy (adding an agent rather than changing regimens) is consistent with observations in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer that continuation of trastuzumab beyond progression can be beneficial [46] as well as our observations on resistance and retreatment [47]. The mechanism is unclear but could relate to residual sensitive tumor cells that co-exist with the emerging resistant clone.

Methods

Patients

As part of a dose escalation study of the aromatase inhibitor anastrozole and the mTOR inhibitor everolimus (NCT01197170), we performed NGS on patients who had attained PR or CR (and had a PFS of at least nine months) and available tissue. NGS testing was not a part of standard care, but was done retrospectively after responses were seen. Research involving human subjects (including human material or human data) that is reported in this study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the MD Anderson Internal Review Board, and patients signed informed consent for all experimental therapeutic interventions and for the deposit of NGS results.

Evaluation of HER2/neu amplification, estrogen and progesterone receptor status

Under CLIA conditions, immunohistochemistry was used to measure of HER2/neu, estrogen and progesterone receptors. Estrogen and progesterone receptors were assessed using antibody 6 F11 (Novocastra Laboratories, Ltd., Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK). Alternatively, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was used to measure the copy number of HER2/neu.

Next-generation sequencing

Molecular analysis using NGS was performed on archival formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Genomic libraries were captured for 3230 exons in 182 cancer-related genes plus 37 introns from 14 genes often rearranged in cancer and sequenced to average median depth of 734× with 99 % of bases covered >100× (Foundation Medicine, Cambridge, MA, USA).

Evaluation of PTEN expression

PTEN expression was assessed using a Dako antibody (Carpinteria, CA, USA) as previously published [49, 50].

Evaluation of response

Responses were assessed after three cycles (about 12 weeks) or earlier at the discretion of the treating physician. All radiological tests were assessed by an MD Anderson radiologist. In addition, results were reviewed in a departmental tumor measurement clinic and by the attending physician. RECIST criteria were used for progressive disease (PD), stable disease (SD), partial and complete responses (PR and CR).

Conclusions

In each of these “super-responders,” tumor tissue that was derived from diagnosis was analyzed by NGS. It is conceivable that the number of aberrations increased by the time the patient was treated in our clinic, which was between one and 3.5 years after diagnosis, especially since each of these patients had received multiple intervening therapies, and now had advanced metastatic disease. Despite these limitations, NGS on tissue from diagnosis was informative, and revealed abnormalities that were actionable, similar to an earlier report by Kalinsky et al. [48]. Optimizing future studies probably requires fresh biopsies at the time of each relapse. However, in their absence, tumor tissue derived from an earlier point in time still yields useful information. Our observations suggest that NGS can help unravel the mechanisms of response and resistance, and warrants additional investigation as a clinical tool to optimize treatment.

Consent

Ethical approval of this study was obtained from the MD Anderson Internal Review Board. Each patient willingly provided written informed consent for all treatment related activities, including the publication of individual outcomes, accompanying images and the deposit of NGS data into an institutional database.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a grant from Foundation Medicine.

Additional file

Molecular Alterations of Super-Responders Treated with Anastrozole and Everolimus.

Footnotes

Competing interests

RY and PJS are employees and stock holders of Foundation Medicine.

Authors’ contributions

JJW conceived the study and helped draft the manuscript. JTA provided data acquisition and analysis and helped draft the manuscript. FJ and SLM assisted in coordination of study. RY and PJS carried out molecular genetic studies. RK participated in the design and coordination of the study and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jennifer J. Wheler, Email: jjwheler@mdanderson.org

Johnique T. Atkins, Email: jtatkins@mdanderson.org

Filip Janku, Email: fjanku@mdanderson.org.

Stacy L. Moulder, Email: smoulder@mdanderson.org

Roman Yelensky, Email: ryelensky@foundationmedicine.com.

Philip J. Stephens, Email: pstephens@foundationmedicine.com

Razelle Kurzrock, Email: rkurzrock@ucsd.edu.

References

- 1.Kallioniemi OP, Kallioniemi A, Kurisu W, Thor A, Chen LC, Smith HS, et al. ERBB2 amplification in breast cancer analyzed by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(12):5321–5325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gretarsdottir S, Thorlacius S, Valgardsdottir R, Gudlaugsdottir S, Sigurdsson S, Steinarsdottir M, et al. BRCA2 and p53 mutations in primary breast cancer in relation to genetic instability. Cancer Res. 1998;58(5):859–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janku F, Wheler JJ, Westin SN, Moulder SL, Naing A, Tsimberidou AM, et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors in patients with breast and gynecologic malignancies harboring PIK3CA mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(8):777–782. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold JM, Choong DY, Thompson ER, Waddell N, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE, et al. Frequent somatic mutations of GATA3 in non-BRCA1/BRCA2 familial breast tumors, but not in BRCA1-, BRCA2- or sporadic breast tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119(2):491–496. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu T, Li C. Convergence between Wnt-beta-catenin and EGFR signaling in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:236. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Augello MA, Burd CJ, Birbe R, McNair C, Ertel A, Magee MS, et al. Convergence of oncogenic and hormone receptor pathways promotes metastatic phenotypes. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(1):493–508. doi: 10.1172/JCI64750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuny M, Kramar A, Courjal F, Johannsdottir V, Iacopetta B, Fontaine H, et al. Relating genotype and phenotype in breast cancer: an analysis of the prognostic significance of amplification at eight different genes or loci and of p53 mutations. Cancer Res. 2000;60(4):1077–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Kuraya K, Schraml P, Torhorst J, Tapia C, Zaharieva B, Novotny H, et al. Prognostic relevance of gene amplifications and coamplifications in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64(23):8534–8540. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jegg AM, Ward TM, Iorns E, Hoe N, Zhou J, Liu X, Singh S, Landgraf R, Pegram MD: PI3K independent activation of mTORC1 as a target in lapatinib-resistant ERBB2+ breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Nicholson RI, Hutcheson IR, Hiscox SE, Knowlden JM, Giles M, Barrow D, et al. Growth factor signalling and resistance to selective oestrogen receptor modulators and pure anti-oestrogens: the use of anti-growth factor therapies to treat or delay endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12(Suppl 1):S29–S36. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao S, Chen X, Lu X, Yu Y, Feng Y. Epidermal growth factor receptor signaling enhanced by long-term medroxyprogesterone acetate treatment in endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105(1):45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wheler J, Moulder S, Naing A, Janku F, Piha-Paul SA, Falchook G, Zinner R, Tsimberidou AM, Fu S, Hong DS et al.: A dose-escalation study of anastrozole and everolimus in patients with advanced gynecologic and brest malignancies: tolerance, biological activity, and moleculer alterations in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Cancer Res 2013, 73(8): Abstract 3514.

- 13.Arcaro A, Guerreiro AS. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in human cancer: genetic alterations and therapeutic implications. Current genomics. 2007;8(5):271–306. doi: 10.2174/138920207782446160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aguirre D, Boya P, Bellet D, Faivre S, Troalen F, Benard J, et al. Bcl-2 and CCND1/CDK4 expression levels predict the cellular effects of mTOR inhibitors in human ovarian carcinoma. Apoptosis. 2004;9(6):797–805. doi: 10.1023/B:APPT.0000045781.46314.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinonen H, Nieminen A, Saarela M, Kallioniemi A, Klefstrom J, Hautaniemi S, et al. Deciphering downstream gene targets of PI3K/mTOR/p70S6K pathway in breast cancer. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:348. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elbauomy Elsheikh S, Green AR, Lambros MB, Turner NC, Grainge MJ, Powe D, et al. FGFR1 amplification in breast carcinomas: a chromogenic in situ hybridisation analysis. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(2):R23. doi: 10.1186/bcr1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eswarakumar VP, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16(2):139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Letessier A, Sircoulomb F, Ginestier C, Cervera N, Monville F, Gelsi-Boyer V, et al. Frequency, prognostic impact, and subtype association of 8p12, 8q24, 11q13, 12p13, 17q12, and 20q13 amplifications in breast cancers. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:245. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ong SH, Hadari YR, Gotoh N, Guy GR, Schlessinger J, Lax I. Stimulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase by fibroblast growth factor receptors is mediated by coordinated recruitment of multiple docking proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(11):6074–6079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111114298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei F, Yan J, Tang D, Lin X, He L, Xie Y, et al. Inhibition of ERK activation enhances the repair of double-stranded breaks via non-homologous end joining by increasing DNA-PKcs activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(1):90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chikazu D, Hakeda Y, Ogata N, Nemoto K, Itabashi A, Takato T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2 directly stimulates mature osteoclast function through activation of FGF receptor 1 and p42/p44 MAP kinase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(40):31444–31450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910132199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janku F, Wheler JJ, Naing A, Falchook GS, Hong DS, Stepanek VM, et al. PIK3CA mutation H1047R is associated with response to PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway inhibitors in early-phase clinical trials. Cancer Res. 2013;73(1):276–284. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsimberidou AM, Iskander NG, Hong DS, Wheler JJ, Falchook GS, Fu S, et al. Personalized medicine in a phase I clinical trials program: the MD Anderson Cancer Center initiative. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(22):6373–6383. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moroney J, Fu S, Moulder S, Falchook G, Helgason T, Levenback C, et al. Phase I study of the antiangiogenic antibody bevacizumab and the mTOR/hypoxia-inducible factor inhibitor temsirolimus combined with liposomal doxorubicin: tolerance and biological activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(20):5796–5805. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hortobagyi GN, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Rugo HS, Burris HA, Campone M, Noguchi S, Perez A, Deleu I, Shtivelband M, Provencher L et al.: Correlation of molecular alterations with efficacy of everolimus in hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer: Results from BOLERO-2. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(18_suppl): LBA509.

- 26.Moroney JW, Schlumbrecht MP, Helgason T, Coleman RL, Moulder S, Naing A, et al. A phase I trial of liposomal doxorubicin, bevacizumab, and temsirolimus in patients with advanced gynecologic and breast malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(21):6840–6846. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, Olopade OI. MYC in breast tumor progression. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008;8(10):1689–1698. doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.10.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouchard C, Marquardt J, Bras A, Medema RH, Eilers M. Myc-induced proliferation and transformation require Akt-mediated phosphorylation of FoxO proteins. EMBO J. 2004;23(14):2830–2840. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dang CV. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell. 2012;149(1):22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stambolic V, MacPherson D, Sas D, Lin Y, Snow B, Jang Y, et al. Regulation of PTEN transcription by p53. Mol Cell. 2001;8(2):317–325. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang F, Lee JT, Navolanic PM, Steelman LS, Shelton JG, Blalock WL, et al. Involvement of PI3K/Akt pathway in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and neoplastic transformation: a target for cancer chemotherapy. Leukemia. 2003;17(3):590–603. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welcker M, Singer J, Loeb KR, Grim J, Bloecher A, Gurien-West M, et al. Multisite phosphorylation by Cdk2 and GSK3 controls cyclin E degradation. Mol Cell. 2003;12(2):381–392. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metz HE, Houghton AM. Insulin receptor substrate regulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(2):206–211. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuo ML, Chuang SE, Lin MT, Yang SY. The involvement of PI 3-K/Akt-dependent up-regulation of Mcl-1 in the prevention of apoptosis of Hep3B cells by interleukin-6. Oncogene. 2001;20(6):677–685. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cavazzoni A, Bonelli MA, Fumarola C, La Monica S, Airoud K, Bertoni R, et al. Overcoming acquired resistance to letrozole by targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in breast cancer cell clones. Cancer Lett. 2012;323(1):77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giuliano M, Schifp R, Osborne CK, Trivedi MV. Biological mechanisms and clinical implications of endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Breast. 2011;20(Suppl 3):S42–S49. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9776(11)70293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller TW, Balko JM, Arteaga CL. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and antiestrogen resistance in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(33):4452–4461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.4879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller TW, Hennessy BT, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Fox EM, Mills GB, Chen H, et al. Hyperactivation of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase promotes escape from hormone dependence in estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(7):2406–2413. doi: 10.1172/JCI41680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanchez CG, Ma CX, Crowder RJ, Guintoli T, Phommaly C, Gao F, et al. Preclinical modeling of combined phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase inhibition with endocrine therapy for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(2):R21. doi: 10.1186/bcr2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Tine BA, Crowder RJ, Ellis MJ. ER and PI3K independently modulate endocrine resistance in ER-positive breast cancer. Cancer discovery. 2011;1(4):287–288. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, Burris HA, 3rd, Rugo HS, Sahmoud T, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(6):520–529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baselga J, Semiglazov V, van Dam P, Manikhas A, Bellet M, Mayordomo J, et al. Phase II randomized study of neoadjuvant everolimus plus letrozole compared with placebo plus letrozole in patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(16):2630–2637. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slomovitz BM, Brown J, Johnston TA, Mura D, Levenback C, Wolf J, Adler KR, Lu H, Coleman RL: A phase II study or everolimus and letrozole in patients with recurrent endometrial carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29(suppl; abstr 5012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Saini KS, Loi S, de Azambuja E, Metzger-Filho O, Saini ML, Ignatiadis M, et al. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and Raf/MEK/ERK pathways in the treatment of breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39(8):935–946. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Axelrod M, Gordon VL, Conaway M, Tarcsafalvi A, Neitzke DJ, Gioeli D, et al. Combinatorial drug screening identifies compensatory pathway interactions and adaptive resistance mechanisms. Oncotarget. 2013;4(4):622–635. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petrelli F, Barni S. A Pooled Analysis of 2618 Patients Treated with Trastuzumab Beyond Progression for Advanced Breast Cancer. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naing A, Kurzrock R. Chemotherapy resistance and retreatment: a dogma revisited. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2010;9(2):E1–E4. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2010.n.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalinsky K, Heguy A, Bhanot UK, Patil S, Moynahan ME. PIK3CA mutations rarely demonstrate genotypic intratumoral heterogeneity and are selected for in breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129(2):635–643. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1601-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stemke-Hale K, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Lluch A, Neve RM, Kuo WL, Davies M, et al. An integrative genomic and proteomic analysis of PIK3CA, PTEN, and AKT mutations in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68(15):6084–6091. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Janku F, Broaddus R, Bakker R, Hong D, Stepanek V, Naing A, Falchook G, Fu S, Wheler JJ, Piha-Paul SA et al.: PTEN assessment and PI3K/mTOR inhibitors: Importance of simultaneous assessment of MAPK pathway aberrations. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30:suppl; abstr 10510.