Abstract

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa nosocomial pneumonia (Pa-NP) is associated with considerable morbidity, prolonged hospitalization, increased costs, and mortality.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of adult patients with Pa-NP to determine 1) risk factors for multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains and 2) whether MDR increases the risk for hospital death. Twelve hospitals in 5 countries (United States, n = 3; France, n = 2; Germany, n = 2; Italy, n = 2; and Spain, n = 3) participated. We compared characteristics of patients who had MDR strains to those who did not and derived regression models to identify predictors of MDR and hospital mortality.

Results

Of 740 patients with Pa-NP, 226 patients (30.5%) were infected with MDR strains. In multivariable analyses, independent predictors of multidrug-resistance included decreasing age (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.91, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.96-0.98), diabetes mellitus (AOR 1.90, 95% CI 1.21-3.00) and ICU admission (AOR 1.73, 95% CI 1.06-2.81). Multidrug-resistance, heart failure, increasing age, mechanical ventilation, and bacteremia were independently associated with in-hospital mortality in the Cox Proportional Hazards Model analysis.

Conclusions

Among patients with Pa-NP the presence of infection with a MDR strain is associated with increased in-hospital mortality. Identification of patients at risk of MDR Pa-NP could facilitate appropriate empiric antibiotic decisions that in turn could lead to improved hospital survival.

Introduction

Recent trends show an increase in the prevalence of nosocomial pneumonia (NP) caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria, most commonly Pseudomonas aeruginosa with documented resistance to β-lactams, carbapenems, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones [1-3]. Consequently, the therapeutic effectiveness of current therapies for bacterial NP is becoming increasingly limited, emphasizing the need for development of new and effective antimicrobials as well as novel strategies to prevent resistance emergence [4,5].

Nosocomial pneumonia due to P. aeruginosa (Pa-NP) is associated with considerable morbidity, prolonged hospitalization, increased costs, and mortality [6-8]. P. aeruginosa is one of the few pathogens independently associated with increased mortality among patients with sepsis or pneumonia in the ICU setting [6,9]. The mortality associated with Pa-NP is further increased when inappropriate initial antibiotic therapy (IIAT) is prescribed, usually due to the presence of MDR pathogens [10-13]. The overall impact of Pa-NP on clinical outcomes and healthcare costs underscores the importance of this nosocomial infection. Therefore, we performed a multinational study with the following objectives: first, to evaluate the prevalence of MDR Pa-NP and to identify clinical risk factors associated with MDR Pa-NP; second, to evaluate the influence of MDR status on patient outcomes.

Methods

Study design and ethical standards

We conducted a retrospective study in 12 hospitals in 5 countries (United States, n = 3; France, n = 2; Germany, n = 2; Italy, n = 2; and Spain, n = 3). Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years consecutively admitted for their index hospitalization within 36 months prior to study initiation in 2013. All eligible patients met a clinical diagnosis of NP defined as new or progressive infiltrates consistent with pneumonia on chest radiograph or computed tomography and either a temperature >38.3°C or leukocytosis >10,000 cells/mm3 or both. To be eligible, patients had to have P. aeruginosa cultured from at least one of the following respiratory specimens, including sputum, pleural fluid, flexible bronchoscopy with protected specimen brush, bronchoalveolar (BAL), transbronchial biopsy, nonbronchoscopic BAL, or tracheobronchial aspirate in intubated patients. Microbiologic cultures (qualitative or quantitative) had to be obtained within the 12-hour window before or the 12-hour window after the initiation of antibiotic(s) targeting P. aeruginosa. Each investigator obtained approval and a waiver of patient consent from an Independent Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board at their institution before commencing the study. The list of all ethical bodies that approved the study can be found in the Acknowledgements section.

Endpoints and covariates

The primary endpoints examined were multidrug-resistance and hospital mortality. We collected important covariates including demographics, comorbidities (heart failure, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, hematologic malignancy, solid tumor, HIV/AIDS, and dementia). In addition, important process-of-care variables, including ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, vasopressor administration, and the appropriateness of initial antibiotic therapy, were collected.

Definitions

To be classified as MDR, the P. aeruginosa isolate had to be non-susceptible to one or more agents in three or more of the following antimicrobial categories, as determined by the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): aminoglycosides, antipseudomonal carbapenems, antipseudomonal cephalosporins, antipseudomonal fluoroquinolones, antipseudomonal penicillins plus β-lactamase inhibitors, monobactams, phosphonic acids, and polymixins. To be classified as extensively drug-resistant (XDR), the P. aeruginosa isolate had to be non-susceptible to one or more agents in all but two or more of the aforementioned antimicrobial categories [14]. Antimicrobial treatment was deemed to be appropriate (AIAT) if at least one of the initially prescribed antibiotics was active against the identified P. aeruginosa isolate based on in vitro susceptibility testing and this antibiotic was administered within 24 hours after collection of the respiratory specimen [15].

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Microbiology laboratories performed antimicrobial susceptibility testing of isolates using disk diffusion or automated testing methods according to guidelines and breakpoints established by the Clinical Laboratory and Standards Institute (CLSI) [16] and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [17].

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were reported as means with standard deviation or the median and interquartile range from non-normally distributed data. Differences between continuous variables were tested using Student’s t-test or the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-test. Categorical data were summarized as proportions, and the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for small samples was used to examine differences between groups. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were constructed to identify clinical risk factors associated with multidrug-resistance. All variables that showed a significant result in the univariate analysis (≤0.10) were included in the corresponding multivariate logistic regression analysis. All variables entered into the models were examined to assess for co-linearity, and interaction terms were tested. The model’s calibration was assessed with the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. A Cox proportional hazards model was constructed to determine variables independently associated with hospital mortality. This test was selected to exclude the influence of time-dependent covariates on hospital mortality and to adequately control for imbalances in baseline and clinical characteristics when constructing a survival curve. All tests were two-tailed, and a P-value <0.05 was deemed a priori to represent statistical significance. All analyses were performed with SPSS software, version 19.0 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Seven hundred and forty patients with Pa-NP met the inclusion criteria and were enroled in the study: 258 (34.9%) from the United States, 141 (19.1%) from France, 120 (16.2%) from Germany, 113 (15.3%) from Spain and 108 (14.6%) from Italy. The prevalence of multidrug resistance was 30.5%. The patients’ baseline and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients with pneumonia caused by MDR strains of P. aeruginosa were significantly younger and were more likely to be admitted to the hospital from an inpatient rehabilitation facility compared to patients infected with non-MDR strains. Patients with MDR strains were significantly more likely to have received antibiotics in the 30 days prior to the diagnosis of pneumonia and were also more likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes mellitus. A significantly higher proportion of patients who were infected with an MDR strain received IIAT (37.9% versus 19.2%, P <0.001) and required ICU admission (79.6% versus 71.4%, P = 0.019) compared to those with a non-MDR strain.

Table 1.

Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of multidrug (MDR) and non-multidrug resistant patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia

| Characteristic | Percent missing (of total 740) | MDR N = 226 | Non-MDR N = 514 | P -value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 0.5%a | 53.5 ± 17.5 | 62.1 ± 15.5 | <0.001 |

| Male | 0% | 142 (62.8%) | 361 (70.2%) | 0.047 |

| Location prior to admission | 1.1% | |||

| Community | 101 (44.7%) | 286 (55.6%) | 0.006 | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 17 (7.5%) | 37 (7.2%) | 0.876 | |

| Long-term care facility | 7 (3.1%) | 20 (3.9%) | 0.596 | |

| Assisted living | 4 (1.8%) | 3 (0.6%) | 0.125 | |

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 27 (11.9%) | 20 (3.9%) | <0.001 | |

| Other | 66 (29.2%) | 144 (28.0%) | 0.741 | |

| Past medical history | ||||

| Hospitalized in the previous 6 months | 13.1% | 126 (60.6%) | 245 (56.3%) | 0.307 |

| Antibiotics in the previous 30 days | 27.6% | 100 (57.5%) | 163 (45.0%) | 0.007 |

| Heart failure | 9.6% | 49 (23.2%) | 131 (28.6%) | 0.145 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 9.2% | 102 (48.8%) | 173 (37.4%) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8.6% | 79 (37.8%) | 137 (29.3%) | 0.029 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 9.3% | 55 (26.3%) | 118 (25.5%) | 0.832 |

| Chronic liver disease | 11.9% | 38 (18.5%) | 70 (15.7%) | 0.359 |

| Hematologic malignancy | 9.9% | 20 (9.4%) | 40 (8.8%) | 0.807 |

| Solid tumor | 10.3% | 18 (8.7%) | 81 (17.7%) | 0.002 |

| HIV/AIDS | 10.5% | 3 (1.5%) | 6 (1.3%) | 0.885 |

| Dementia | 12.6% | 6 (3.0%) | 36 (8.1%) | 0.015 |

| Charlson score, mean ± SD | 2.6% | 3.1 ± 2.6 | 3.0 ± 2.6 | 0.869 |

| Pneumonia category | 0% | |||

| Community-onset, healthcare-associated | 74 (32.7%) | 167 (32.5%) | 0.946 | |

| Hospital-onset | 152 (67.2%) | 347 (67.5%) | 0.946 | |

| Hospital-acquired | 50 (22.1%) | 112 (21.8%) | 0.919 | |

| Ventilator-associated | 102 (45.1%) | 235 (45.7%) | 0.883 | |

| ICU admission | 0% | 180 (79.6%) | 367 (71.4%) | 0.019 |

| Length of ICU stay, days, median (IQR) | 0% | 18.9 (11.4, 32.5) | 16.1 (8.7, 29.1) | 0.058 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0% | 197 (87.2%) | 440 (85.6%) | 0.571 |

| Length of mechanical ventilation, days, median (IQR) | 0% | 17.0 (9.1, 34.1) | 13.1 (6.5, 26.0) | 0.006 |

| Vasopressor administration | 0% | 146 (64.6%) | 308 (59.9%) | 0.229 |

| Bacteremia | 0% | 53 (23.5%) | 128 (24.9%) | 0.672 |

| Inappropriate initial antibiotic therapy | 1.5% | 83 (37.9%) | 98 (19.2%) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality | 0% | 101 (44.7%) | 163 (31.7%) | 0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay, days, median (IQR) | 0% | 27.0 (14.0, 56.3) | 25.0 (13.0, 46.0) | 0.090 |

aFour patients aged >90 years (one MDR, three non-MDR) were not included in the calculation.

Susceptibility to all antibiotic classes tested was significantly lower in patients infected with MDR strains (Table 2). Antibiotic susceptibility by country is found in Table 3. Germany (44.2%) and Spain (43.4%) were found to have the highest prevalence of MDR, followed by France (33.3%), Italy (22.2%) and the United States (20.5%). Table 4 shows the results of a multivariable logistic regression model that identified the variables associated with pneumonia caused by MDR strains of P. aeruginosa. Decreasing age in increments of one year, diabetes mellitus, and ICU admission were independently associated with MDR P. aeruginosa pneumonia.

Table 2.

Antibiotic susceptibility

| Antibiotic class | Multidrug-resistant (n = 226) | Non-multidrug-resistant (n = 514) | P -value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycosides | 226 (29.2%) | 505 (91.1%) | <0.001 |

| Antipseudomonal carbapenems | 226 (15.0%) | 508 (84.6%) | <0.001 |

| Antipseudomonal cephalosporins | 226 (26.5%) | 504 (93.7%) | <0.001 |

| Antipseudomonal fluoroquinolones | 222 (21.5%) | 502 (88.4%) | <0.001 |

| Antipseudomonal penicillins + | 221 (22.2%) | 502 (89.0%) | <0.001 |

| β-lactamase inhibitors | |||

| Monobactams | 158 (13.9%) | 208 (81.2%) | <0.001 |

| Phosphonic acids | 86 (40.7%) | 105 (81.0%) | <0.001 |

| Polymyxins | 159 (97.5%) | 215 (92.1%) | 0.025 |

Data presented as number of isolates tested (% susceptible). Multidrug-resistant: non-susceptible to one or more agents in three or more antibiotic classes.

Table 3.

Antibiotic susceptibility by country

| Antibiotic class | France | Germany | Italy | Spain | United States |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycosides | 141(76.6) | 120 (58.3) | 101 (75.2) | 112 (58.9) | 257 (80.2) |

| Antipseudomonal carbapenems | 139 (60.4) | 119 (52.1) | 107 (57.9) | 112 (47.3) | 257 (79.0) |

| Antipseudomonal cephalosporins | 140 (77.1) | 120 (60.8) | 101 (74.3) | 111 (59.5) | 258 (81.4) |

| Antipseudomonal fluoroquinolones | 138 (66.7) | 118 (61.0) | 100 (75.0) | 111 (52.3) | 257 (75.9) |

| Antipseudomonal penicillins + | 141 (64.5) | 118 (46.5) | 108 (70.3) | 110 (63.6) | 253 (82.6) |

| β-lactamase inhibitors | |||||

| Multidrug-resistant | 141 (33.3) | 120 (44.2) | 108 (22.2) | 113 (43.4) | 258 (20.5) |

| Extensively drug-resistant | 141 (17.7) | 120 (34.2) | 108 (2.8) | 113 (13.3) | 258 (3.5) |

Data presented as number of isolates tested (% susceptible). Multidrug-resistant: non-susceptible to one or more agents in three or more antibiotic classes. Extensively drug-resistant: non-susceptible to one or more agents in all but two or fewer antibiotic classes.

Table 4.

Significant univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of predictors for multidrug-resistant (MDR) Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia

| Univariate | Multivariate a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P -value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P -value |

| Age (decreasing increments of 1) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | <0.001 |

| Male | 0.72 (0.52, 0.99) | 0.047 | ||

| Residence in a community setting prior to admission | 0.64 (0.47, 0.88) | 0.006 | ||

| Residence in an inpatient rehabilitation facility prior to admission | 3.35 (1.84, 6.11) | <0.001 | ||

| Antibiotics in the previous 30 days | 1.65 (1.15, 2.38) | 0.007 | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.60 (1.15, 2.22) | 0.005 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.46 (1.04, 2.06) | 0.030 | 1.90 (1.21, 3.00) | 0.006 |

| Solid tumor | 0.44 (0.26, 0.76) | 0.003 | ||

| Dementia | 0.35 (0.15, 0.85) | 0.020 | ||

| ICU admission | 1.57 (1.08, 2.28) | 0.019 | 1.73 (1.06, 2.81) | 0.028 |

aHosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, P = 0.72.

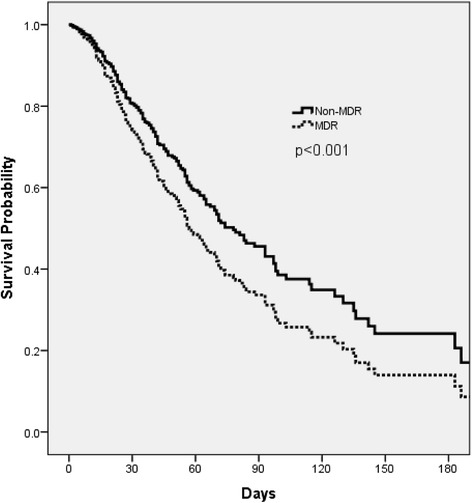

The overall, hospital mortality was 35.7% (n = 264). Mortality was significantly different between the United States and European countries: United States, 22.5%; France, 37.6%; Germany, 41.7%; Spain, 46.9%; and Italy, 46.3%. Patients with MDR strains had a significantly higher in-hospital mortality rate compared to non-MDR infected patients (Table 1). A Cox proportional hazards model confirmed MDR status as an independent predictor of mortality (hazard ratio (HR) 1.39, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.83, P = 0.021) along with increasing age, heart failure, concomitant bacteremia, mechanical ventilation, and patients residing in Germany, Italy, and Spain (Table 5). Cox model-adjusted survival curve analysis controlling baseline and clinical imbalances confirmed the influence of MDR on in-hospital mortality (Figure 1).

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazards model of significant predictors for in-hospital mortality

| Variable | Hazards ratio (95% CI) | P -value |

|---|---|---|

| Heart failure | 1.88 (1.39, 2.52) | <0.001 |

| Age (increasing increments of 1 year) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) | 0.001 |

| Country of origin, Germany | 3.05 (1.87, 4.96) | <0.001 |

| Country of origin, Italy | 2.38 (1.41, 4.02) | 0.001 |

| Country of origin, Spain | 1.91 (1.16, 3.14) | 0.011 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1.88 (1.02, 3.48) | 0.044 |

| Bacteremia | 1.67 (1.20, 2.31) | 0.002 |

| Multidrug resistance | 1.39 (1.05, 1.83) | 0.021 |

| No vasopressors | 0.61 (0.43, 0.87) | 0.006 |

| Healthcare associated pneumonia | 0.50 (0.35, 0.73) | <0.001 |

Variables excluded from the model for co-linearity: aminoglycoside resistance, carbapenem resistance, fluoroquinolone resistance, penicillin-β-lactamase inhibitor resistance (co-linear with multidrug resistance); country of origin - United States (co-linear with France, Germany, Italy, and Spain). Variables included but not retained in the model at P <0.05: ICU admission, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, country of origin - France.

Figure 1.

Cox proportional hazards model curve comparing patients with multidrug-resistant (MDR)-Pseudomonas aeruginosa and those with non-MDR P. aeruginosa nosocomial pneumonia.

Discussion

This international investigation representing the largest cohort study of Pa-NP demonstrated high prevalence of MDR at 30.5%. Infection caused by MDR P. aeruginosa was found to be an important determinant of hospital mortality, thus, it is critical for clinicians to identify patients at risk of MDR from the onset of infection. Our analysis suggests that the patient’s age, comorbid conditions specifically diabetes, and the severity of infection as indicated by the need for ICU admission predicts infection with a MDR strain of P. aeruginosa.

The prevalence of MDR Pa-NP is variable depending on the type of study performed and the participating institutions. A recent large epidemiologic study from the United States identified 205,526 P. aeruginosa isolates (187,343 pneumonia; 18,183 bloodstream infection (BSI)) and 95,566 Enterobacteriaceae specimens (58,810 pneumonia; 36,756 BSI) associated with infection [1]. Prevalence of MDR P. aeruginosa (MDR Pa) was approximately 15-fold greater than carbapenem-resistant-Enterobacteriaceae in both infection types. A net rise in MDR Pa as a proportion of all P. aeruginosa infections occurred from 2000 to 2009. Likewise, data from the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) in the United States revealed an increased prevalence of MDR Pa VAP from the period 2007 to 2008 to the period 2009 to 2010, but, it should be noted the overall prevalence of MDR Pa was 17.7% in the latter time period, markedly less than our study [3]. The international composition of the participants is the most likely explanation for the higher prevalence of MDR strains in our study.

The literature also varies with respect to the outcomes of patients with MDR Pa-NP. Peña et al. examined a Spanish cohort of 91 episodes of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) in 83 patients, 31 caused by susceptible P. aeruginosa and 60 by MDR Pa strains [18]. These investigators found that susceptible P. aeruginosa infections were more likely than MDR Pa episodes to receive AIAT and definitive antimicrobial therapy, and in a logistic regression model IIAT was identified as an independent risk factor for early mortality. A recent meta-analysis supports these findings by demonstrating that MDR status is an important determinant of mortality due to nosocomial infections attributed to Gram-negative bacteria, where P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter species were the most common isolates [19]. Di Pasquale et al. recently found MDR status was not associated with a higher rate of ICU or hospital mortality in patients with ICU-acquired pneumonia. However, unlike our study, the etiology of infection was a mix of Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens and there was a small number of MDR Pa cases (n = 18) [20].

Increasing antimicrobial resistance in P. aeruginosa infections seems to be the most important predictor of outcome. In a recent Brazilian study of P. aeruginosa bacteremia isolates from 120 patients [21], 45.8% were resistant to carbapenems, and 23.3% expressed a metallo-β-lactamase gene, blaSPM-1 (57%) or blaVIM-type (43%). Cefepime-resistance, MDR status and XDR isolates were independently associated with IIAT, which was an important predictor of mortality. These studies support the importance of appropriate and timely antibiotic therapy as a potential determinant of outcome for serious infections attributed to P. aeruginosa. Given the association of antibiotic resistance with increasing administration of IIAT and greater hospital mortality, several strategies have been developed to improve upon the appropriateness of empiric therapy in patients at risk of infection with P. aeruginosa and other antibiotic-resistant pathogens.

A number of investigations have identified risk factors and scoring systems for infection with MDR pathogens, including MDR Pa [22-25]. Major limitations of such approaches are that the potential for IIAT remains, although potentially diminished, and the resultant overuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics in many patients because of the non-specificity of the scoring systems. Novel methods to improve early identification of pathogens and antibiotic susceptibilities are also entering the diagnostic arena. Such diagnostic technology advances offer the potential to maximize administration of appropriate antibiotic therapy while minimizing unnecessary antibiotic exposure. These approaches include the use of molecular methods (for example, polymerase chain reaction electrospray ionization mass spectrometry and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF), as well as advanced automated microscopy techniques that allow the identification of bacterial species, the presence of antibiotic resistance genes, and bacterial killing by specific antibiotics within 4 to 6 hours using direct specimen inoculation [26,27].

Our study has a number of limitations. As a retrospective cohort, it is prone to several forms of bias, most notably selection bias. We attempted to mitigate this by enroling consecutive patients fitting the predetermined enrolment criteria. Although we adjusted for known confounders, the possibility exists that some residual confounding remains, particularly confounding by indication. Another important limitation is the potential for patients to be enroled who did not have true pneumonia. Our use of clinical criteria along with microbiologic confirmation was an attempt to maximize the number of patients with Pa-NP in our cohort. Additionally, antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed at the local hospital level. Therefore, the determination of MDR status may have varied more than if a single reference laboratory was used to determine the presence or absence of drug resistance. It is also important to note that although our results strongly suggest that the association of MDR status with increased risk of death is mechanistically related to the risk of receiving inappropriate empiric therapy, we cannot rule out that MDR Pa-NP may exert its lethal effect directly due to higher virulence, as has been suggested with other pathogens exhibiting higher minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) to certain antimicrobials [28,29]. Because we examined hospital mortality rather than the more standard 28-day mortality as the primary outcome for our study, we may have overestimated the magnitude of this outcome. Last, individual antibiotics are commonly part of a regimen for the treatment of nosocomial pneumonia, therefore, independent analysis of the impact on AIAT may not represent the true prescribing practice at each site.

Conclusions

In summary, our study sheds light on variables associated with to MDR Pa-NP; namely decreasing age, diabetes mellitus and ICU admission. In addition, MDR status is an independent predictor of hospital mortality in patients with Pa-NP. Given the high rates of MDR Pa-NP, advances in rapid diagnosis and susceptibility analysis are needed to direct antibiotic treatment and potentially improve outcomes.

Key messages

Among patients with Pa-NP, presence of infection with MDR strains is an important independent predictor for hospital mortality.

Independent predictors of MDR strains of P. aeruginosa in this study included decreasing age, diabetes, and ICU admission.

Advances in rapid diagnostics and antibiotic susceptibility analysis are needed to direct antibiotic treatment and potentially improve outcomes of patients infected with MDR strains of P. aeruginosa.

Acknowledgements

We recognize Erin N Frazee, PharmD and Heather A Personett, PharmD at the Mayo Clinic for their contributions to data collection and review of the manuscript. The following Independent Ethics Committees or Institutional Review Boards approved the study: St Louis College of Pharmacy, Washington University in St Louis, Northwestern University, Mayo Clinic (United States); Conseil National de l’Ordre des Médecins, Conseil National de l’Informatique et des Libertés, (France); Ethik-Kommission der Medizinischen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians Universität, Ethik-Kommission der Medizinischen Hochschule Hannover, (Germany); Comitato Etico Dell’ Universita’ Cattolica Del Sacro Cuore - Policlinico Universitario, Comitato Etico Toscana Area Vasta Nord Est, (Italy); CEIC Hospital Mutua de Terrassa, CEIC H Vall d Hebron, CEIC Hospital Clinic i Provincial de Barcelona, (Spain). The study was supported by a grant from Cubist Pharmaceuticals. Employees of the sponsor had a role in the study design and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and were responsible for the content of the manuscript and the decision to submit for publication.

Abbreviations

- AIAT

appropriate initial antibiotic therapy

- AOR

adjusted odds ratio

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- BSI

bloodstream infection

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CLSI

Clinical Laboratory and Standards Institute

- ECDC

European Center for Disease Prevention and Control

- ESBLs

extended spectrum β-lactamases

- EUCAST

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- HR

hazard ratio

- IIAT

inappropriate initial antibiotic therapy

- MALDI-TOF

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight

- MDR

multidrug-resistant

- NP

nosocomial pneumonia

- Pa-NP

Pseudomonas aeruginosa nosocomial pneumonia

- XDR

extensively drug-resistant

Footnotes

Competing interests

STM has received research funding from Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, Forest, Theravance, Tetraphase and Pfizer. MHK has served as a consultant to and/or received research funding from Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, Pfizer, Forest, Cardeas, the Academy of Infection Management and Theravance. JR has served as a consultant to and/or received research funding from Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Basilea and the Academy of Infection Management. VM is an employee and stockholder of Cubist Pharmaceuticals.

The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

STM, MHK, and CC participated in conception, design, analysis and interpretation of the data and drafting of the manuscript. They are accountable for data accuracy as well as the analytic and reporting integrity of the study. They take responsibility for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved and have given final approval for the version to be published. RGW, JR, JC, MA, TW, BC, HO, EC, AT, FM, GES, and VM participated in conception and study design. They were involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Each author takes responsibility for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Contributor Information

Scott T Micek, Email: scott.micek@stlcop.edu.

Richard G Wunderink, Email: r-wunderink@northwestern.edu.

Marin H Kollef, Email: mkollef@dom.wustl.edu.

Catherine Chen, Email: cxchen@dom.wustl.edu.

Jordi Rello, Email: jrello@crips.es.

Jean Chastre, Email: jean.chastre@psl.aphp.fr.

Massimo Antonelli, Email: m.antonelli@rm.unicatt.it.

Tobias Welte, Email: welte.tobias@mh-hannover.de.

Bernard Clair, Email: Bernard.clair@rpc.ap-hop-paris.fr.

Helmut Ostermann, Email: helmut.ostermann@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Esther Calbo, Email: ecalbo@mutuaterrassa.es.

Antoni Torres, Email: ATORRES@clinic.ub.es.

Francesco Menichetti, Email: menichettifrancesco@gmail.com.

Garrett E Schramm, Email: schramm.garrett@mayo.edu.

Vandana Menon, Email: Vandana.Menon@cubist.com.

References

- 1.Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF. Prevalence of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae among specimens from hospitalized patients with pneumonia and bloodstream infections in the United States from 2000 to 2009. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:559–63. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Croughs PD, Li B, Hoogkamp-Korstanje JA, Stobberingh E, Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Group Thirteen years of antibiotic susceptibility surveillance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from intensive care units and urology services in the Netherlands. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32:283–88. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1741-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, Schneider A, Patel J. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Team and Participating NHSN Facilities, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009–2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:1–14. doi: 10.1086/668770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nathan C, Cars O. Antibiotic resistance - problems, progress, and prospects. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1761–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1408040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kollef MH, Micek ST. Rational Use of Antibiotics in the ICU: Balancing stewardship and clinical outcomes. JAMA. 2014;312:1403–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL, Ranieri VM, Reinhart K, Gerlach H, et al. Sepsis Occurrence in Acutely Ill Patients Investigators. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:344–53. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000194725.48928.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker CM, Kutsogiannis J, Muscedere J, Cook D, Dodek P, Day AG, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant organisms or Pseudomonas aeruginosa: prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. J Crit Care. 2008;23:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crouch Brewer S, Wunderink RG, Jones CB, Leeper KV., Jr Ventilator-associated pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chest. 1996;109:1019–29. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.4.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kollef MH, Chastre J, Clavel M, Restrepo MI, Michiels B, Kaniga K, et al. A randomized trial of 7-day doripenem versus 10-day imipenem-cilastatin for ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care. 2012;16:R218. doi: 10.1186/cc11862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garnacho-Montero J, Sa-Borges M, Sole-Violan J, Barcenilla F, Escoresca-Ortega A, Ochoa M, et al. Optimal management therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia: an observational, multicenter study comparing monotherapy with combination antibiotic therapy. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1888–95. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000275389.31974.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muscedere JG, Shorr AF, Jiang X, Day A, Heyland DK, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group The adequacy of timely empiric antibiotic therapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia: an important determinant of outcome. J Crit Care. 2012;27:322. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung DR, Song JH, Kim SH, Thamlikitkul V, Huang SG, Wang H, et al. High prevalence of multidrug-resistant nonfermenters in hospital-acquired pneumonia in Asia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1409–17. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201102-0349OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Micek ST, Reichley RM, Kollef MH. Health care-associated pneumonia (HCAP): empiric antibiotics targeting methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa predict optimal outcome. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011;90:390–5. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318239cf0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kollef MH. Broad-spectrum antimicrobials and the treatment of serious bacterial infections: getting it right up front. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:S3–13. doi: 10.1086/590061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Nineteenth Informational Supplement 2009; M100-S19. Wayne, PA: CLSI.

- 17.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Versions 1.3 and 2.0. http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/. Accessed 25 August 2014.

- 18.Peña C, Gómez-Zorrilla S, Oriol I, Tubau F, Dominguez MA, Pujol M, et al. Impact of multidrug resistance on Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia outcome: predictors of early and crude mortality. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32:413–20. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1758-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vardakas KZ, Rafailidis PI, Konstantelias AA, Falagas ME. Predictors of mortality in patients with infections due to multi-drug resistant Gram negative bacteria: the study, the patient, the bug or the drug? J Infect. 2013;66:401–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Pasquale M, Ferrer M, Esperatti M, Crisafulli E, Giunta V, Li Bassi G, et al. Assessment of Severity of ICU-Acquired Pneumonia and AssociationWith Etiology. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:303–12. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a272a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dantas RC, Ferreira ML, Gontijo-Filho PP, Ribas RM. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: independent risk factors for mortality and impact of resistance on outcome. J Med Microbiol. 2014;63:1679–87. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.073262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maruyama T, Fujisawa T, Okuno M, Toyoshima H, Tsutsui K, Maeda H, et al. A new strategy for healthcare-associated pneumonia: a 2-year prospective multicenter cohort study using risk factors for multidrug-resistant pathogens to select initial empiric therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1373–83. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shindo Y, Ito R, Kobayashi D, Ando M, Ichikawa M, Shiraki A, et al. Risk factors for drug-resistant pathogens in community-acquired and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:985–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201301-0079OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Reichley R, Kan J, Hoban A, Hoffman J, et al. Validation of a clinical score for assessing the risk of resistant pathogens in patients with pneumonia presenting to the emergency department. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:193–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aliberti S, Cilloniz C, Chalmers JD, Zanaboni AM, Cosentini R, Tarsia P, et al. Multidrug-resistant pathogens in hospitalized patients coming from the community with pneumonia: a European perspective. Thorax. 2013;68:997–9. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burnham CA, Frobel RA, Herrera ML, Wickes BL. Rapid ertapenem susceptibility testing and Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase phenotype detection in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates by use of automated microscopy of immobilized live bacterial cells. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:982–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03255-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laffler TG, Cummins LL, McClain CM, Quinn CD, Toro MA, Carolan HE, et al. Enhanced diagnostic yields of bacteremia and candidemia in blood specimens by PCR-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:3535–41. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00876-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beyrouthy R, Robin F, Cougnoux A, Dalmasso G, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Mallat H, et al. Chromosome-mediated OXA-48 carbapenemase in highly virulent Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:1558–61. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruhn KW, Pantapalangkoor P, Nielsen T, Tan B, Junus J, Hujer KM, et al. Host fate is rapidly determined by innate effector-microbial interactions during Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:1296–305. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]