SUMMARY

OBJECTIVES

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) patients experience significant deficits in category-related object recognition and naming following standard surgical approaches. These deficits may result from a decoupling of core processing modules (e.g., language, visual processing, semantic memory), due to “collateral damage” to temporal regions outside the hippocampus following open surgical approaches. We predicted stereotactic laser amygdalohippocampotomy (SLAH) would minimize such deficits because it preserves white matter pathways and neocortical regions critical for these cognitive processes.

METHODS

Tests of naming and recognition of common nouns (Boston Naming Test) and famous persons were compared with nonparametric analyses using exact tests between a group of nineteen patients with medically-intractable mesial TLE undergoing SLAH (10 dominant, 9 nondominant), and a comparable series of TLE patients undergoing standard surgical approaches (n=39) using a prospective, non-randomized, non-blinded, parallel group design.

RESULTS

Performance declines were significantly greater for the dominant TLE patients undergoing open resection versus SLAH for naming famous faces and common nouns (F=24.3, p<.0001, η2=.57, & F=11.2, p<.001, η2=.39, respectively), and for the nondominant TLE patients undergoing open resection versus SLAH for recognizing famous faces (F=3.9, p<.02, η2=.19). When examined on an individual subject basis, no SLAH patients experienced any performance declines on these measures. In contrast, 32 of the 39 undergoing standard surgical approaches declined on one or more measures for both object types (p<.001, Fisher’s exact test). Twenty-one of 22 left (dominant) TLE patients declined on one or both naming tasks after open resection, while 11 of 17 right (non-dominant) TLE patients declined on face recognition.

SIGNIFICANCE

Preliminary results suggest 1) naming and recognition functions can be spared in TLE patients undergoing SLAH, and 2) the hippocampus does not appear to be an essential component of neural networks underlying name retrieval or recognition of common objects or famous faces.

Keywords: epilepsy surgery, naming and recognition, cognitive outcome, famous faces, laser interstitial thermal therapy, LITT

INTRODUCTION

MRI-guided stereotactic laser amygdalohippocampotomy (SLAH) is a novel, minimally invasive, approach to epilepsy surgery. SLAH holds promise for reducing procedure duration and hospital stay,1 has cosmetic advantages, involves less pain and discomfort, and may minimize post-surgical cognitive decline associated with standard resections. Initial experience with SLAH for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) demonstrates that it can eliminate seizures in well-selected patients,2-3 but cognitive outcomes have not yet been reported.

Decreased naming ability, often more pronounced for proper nouns (e.g., famous faces, landmarks), commonly occurs after language dominant (typically left-sided) anteromedial TL resection.4-7 Further, we have demonstrated meaningful declines in recognition of famous faces and select object categories (e.g., landmarks and animals but not common object recognition) following right anteromedial TL resection.5, 7, 8 Since assessment of these functions is not a routine component of pre-operative evaluation at most epilepsy centers, these declines in famous face and object recognition have not been widely appreciated. Nevertheless, naming and recognition deficits can cause social, vocational, and academic difficulty. Duffau and colleagues demonstrated that even a subtle decline in naming response speed in patients undergoing tumor surgery involving the anterior TL region predicted a poor outcome in terms of returning to work.9 Fortunately, the effects of face and object recognition deficits on daily life in some patient groups are becoming increasingly recognized.10

Naming and recognition deficits may reflect temporal stem white matter (WM) damage sustained during access to, rather than direct resection of, mesial TL structures.7 Indeed, naming and recognition deficits characteristic of semantic dementia result from pathology of bilateral temporal poles and lateral inferior temporal gyri, initially sparing mesial TL.11 Nevertheless, many researchers, particularly in the setting of epilepsy, consider the hippocampus critical for naming and recognition based on (i) its activation during functional neuroimaging studies of object and face naming,12 (ii) volumetric studies associating smaller hippocampal volume with poorer naming,13 and (iii) observations that naming deficits always occurred when the hippocampus was included in the resection despite patients undergoing cortical stimulation mapping.14 However, open resections including the hippocampus typically affect broader anteromedial TL regions and white matter, making it difficult to attribute such declines solely to this structure.

Research involving congenital prosopagnosic patients unable to recognize familiar persons provides a working hypothesis of declines in famous face recognition following right TLE surgery. Patients with congenital prosopagnosia experience defects in their bilateral inferior visual processing stream (including the inferior lateral fasciculus [ILF] and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus [IFOF]), with dysfunction of these pathways in the right hemisphere correlating with poor face recognition performance.15 Most open anteromedial TL resections affect one or both of these WM pathways, with the IFOF comprising the posterior two-thirds of the WM running through the temporal stem.16 Additionally, some open resections also encroach upon the fusiform gyrus, which has been implicated in the processing of faces.17

Therefore, we examined the relationship between hippocampal resection and outcome for naming and recognition as a function of whether collateral tissue was spared. Our primary hypotheses were: 1) A greater frequency of dominant TL patients undergoing open anteromedial resection will experience significant naming declines on either famous faces or common objects than will dominant TL patients undergoing SLAH; 2) A greater frequency of nondominant TL patients undergoing open anteromedial resection will experience significant recognition declines for famous faces than will nondominant TL patients undergoing SLAH; and 3) No patients undergoing anteromedial resection or SLAH will experience recognition declines for common objects (as prior work has related decline in this area to posterior TL lesions).18

METHODS

Subjects

We present pre- and postsurgical data for 39 patients undergoing traditional open anteromedial TL resections at either Emory University or the University of Washington, and 19 patients undergoing SLAH at Emory only. IRB approval for this study was obtained at both universities, and all patients provided informed consent. Patients were at least 18 years of age and native English speakers. All patients were left hemisphere dominant for language with the exception of two SLAH patients. One left SLAH patient was exclusively right language dominant by Wada testing, and one right SLAH had bilateral language dominance by Wada testing (left > right). Both patients were included in the nondominant resection group (see Table 1 for demographic data). Two additional patients underwent SLAH at Emory University during the same time period. One was excluded due to age (< 18 years) and one was not assessed cognitively before undergoing a subsequent open resection. Seizure outcome data (Engel classifications) are presented both with and without these patients, as seizure freedom rates help to interpret the potential effect of ongoing epileptiform activity on cognitive performance and demonstrate the broader clinical outcomes offered by both surgical approaches. Detailed patient characteristics, details of the SLAH approach, and seizure outcome for the SLAH sample are also presented in a recent technical paper.3

Table 1.

Demographic, Disease-Related Variables, and Surgical Characteristics by Surgical Group.

| Standard Open Resections | Stereotactic Laser Amygdalohippocampotomy |

Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Side of Surgery | 22 Dominant /17 Nondominant | 10 Dominant/9 Nondominant | n.s. | ||

| Dominant | Nondominant | Dominant | Nondominant | ||

| X SD | X SD | X SD | X SD | ||

| Age (years) | 36.0 11.4 | 36.5 11.4 | 38.2 17.1 | 36.2 13.3 | n.s. |

| Education | 12.1īū 2.5 | 15.7īà 3.1 | 12.6ýà 3.3 | 15.4ūý 1.9 | F(3, 54)=7.2, p<.01 |

| Age of Onset | 16.7 12.9 | 13.9 9.3 | 12.4 12.1 | 15.4 1.9 | n.s. |

| Number of AEDs | 2.1 0.8 | 2.0 0.8 | 2.5 0.9 | 1.6 0.5 | n.s. |

| MTS | 10/22 | 9/17 | 7/10 | 3/9 | n.s. |

Note. Standard resections included both standard and tailored anterior TL resections and selective amygdalohippocampectomies. Statistical analysis included Fisher exact test comparisons for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous data. Matching subscripts indicate that differences between subgroups are significant. MTS = mesial temporal sclerosis; AEDs = antiepileptic drugs.

Patients were classified by surgery type (open resection vs. SLAH) and side (dominant vs. nondominant resection). Groups did not differ significantly in age of seizure onset, age at surgery, or number of antiepileptic drugs. Education level was higher for the nondominant resection group regardless of surgery type. Because our primary outcome measures involve individual level change by surgery type, these analyses are not confounded by education differences across seizure onset laterality. More specifically, individual performances are contrasted across surgical approach within dominant and nondominant patients, and laterality effects are not investigated (see statistical plan). Antiepileptic drug regimens did not differ significantly across assessments, as most patients are left on their presurgical regimen for 1 to 2 years post-surgically in our epilepsy programs.

All patients completed presurgical neuropsychological evaluation and a 3T brain MRI. Seizure onset was determined using video-EEG monitoring, and additional invasive electrode monitoring in 6/39 patients undergoing open resection and 4/19 undergoing SLAH. The 4 SLAH patients had strip and depth electrode placement that implicated the hippocampus. All Emory University patients underwent positron emission tomography (PET) and many University of Washington patients underwent ictal single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). Nearly all patients underwent Wada assessment to determine language laterality. Six patients, three undergoing SLAH, underwent fMRI only to determine language laterality (all of these patients were right-handed patients undergoing right TL resections).

Once the SLAH procedure became available at Emory University, patients with focal unilateral MTL seizure onset were offered open resection or SLAH. Anyone eligible for open surgery was eligible for SLAH, without exclusion. Therefore, while not a randomized trial, patients self-selected one procedure versus the other. There was no known systematic bias introduced into treatment assignment by the researchers. Most patients chose SLAH after being presented with both options (i.e., 20 of the last 23 patients during the current study time frame).

Initial cognitive outcome was assessed at approximately 6 months after surgery for the SLAH patients. Open resection patients were evaluated 1-year post operatively based upon standard clinical protocol. Engel seizure classifications are presented for both 6-month and 1-year post-surgical time points for this group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Change in Cognitive Function by Surgery Type, Laterality of Procedure, and Seizure Outcome.

| Dominant TL Procedures | Cognitive Outcome - Same or Improved |

Cognitive Outcome - Declined |

|---|---|---|

| Engel I | SLAH=7; Open=1 | SLAH=0; Open=10 |

| Engel II | SLAH=1; Open=0 | SLAH=0; Open=5 |

| Engel III | SLAH=2; Open=0 | SLAH=0; Open=3 |

| Engel IV | SLAH=0; Open=0 | SLAH=0[ Open=3 |

| Nondominant TL Procedures |

Cognitive Outcome - Same or Improved |

Cognitive Outcome - Declined |

|---|---|---|

| Engel I | SLAH=4; Open=5 | SLAH=0; Open=8 |

| Engel II | SLAH=0; Open=0 | SLAH=0; Open=2 |

| Engel III | SLAH=2; Open=1 | SLAH=0; Open=1 |

| Engel IV | SLAH=3; Open=0 | SLAH=0; Open=0 |

Note. TL = temporal lobe; SLAH = selective laser amygdalohippocampotomy. In this study, cognitive outcome is limited to object and face recognition and naming.

Surgical parameters

All MRI-guided SLAH procedures were performed at Emory University. This consists of stereotactic occipital insertion of an optical fiber assembly (saline-cooled cannula with optic fiber) under general anesthesia, targeting the amygdala and the hippocampus from the pes to mid-body (mean hippocampal ablation length was 2.5 cm).3 Laser induced thermal energy was delivered during continuous MR imaging (Visualase, Inc., Houston, TX). Ablation extent was determined in real-time from temperature-sensitive images of estimated thermal damage. Figure 1 includes a depiction of the laser fiber assembly, the ablation process, and an MRI image of the resulting ablation zone.

Figure 1.

Depiction of the Optical Fiber, the Ablation Process, and Pre- and Post-Ablation MRI Images in an Axial Plane.

Open resections included tailored (n=18) or standard (n=4) anterior temporal lobectomy followed by mesial temporal resection, or selective transcortical amygdalohippocampectomy (SAH) [n=17], variously affecting several temporal lobe regions (e.g., parahippocampal gyrus, enthorhinal cortex, fusiform gyrus, temporal stem and pole) and WM paths (e.g., uncinate fasciculus, ILF, IFOF).

TLE surgical patients at the University of Washington typically underwent a tailored temporal lobectomy (n=18: 11 dominant/7 nondominant),19 with electrocorticography and speech mapping20, 21 to determine extent of lateral (superior, middle, inferior), basal temporal cortex, and hippocampal resection. Superior temporal gyrus resection was avoided other than the anterior 1 cm included in the temporal pole. When minimal lateral cortex was involved in the pathology, or in cases not using electrocorticography, only the anterior 3-4 cm of middle and inferior temporal cortex was resected to allow entry into the temporal horn of the lateral ventricle. The lateral amygdala was resected to the roof of the ventricle and the inferior uncus was resected in a subpial fashion. On average, extent of lateral resection in the tailored procedures, was 3.2 cm (SD = 0.8; range = 1.7 to 4.8 cm), with only one nondominant resection exceeding 4 cm. Basal temporal lobe was resected including parahippocampus and the hippocampal/parahippocampal resection was taken posteriorly to the tectal plate, or less aggressively if indicated by focal pathology or electrocorticography.

Seventeen patients (9 dominant/8 nondominant) underwent SAH at Emory University. This procedure involved exposure to the temporal horn of the lateral ventricle through the inferior temporal sulcus to preserve as much of the temporal stem as possible. While the lateral TL is broached to gain access to the mesial TL region with this procedure, there is no resection of lateral TL. Four patients underwent standard anteromedial TL resection at Emory University (2 dominant/2 nondominant), which involved the resection of lateral TL 3.5 cm from the temporal tip, superiorly limited by the superior pia of the middle temporal gyrus and inferiorly generally including the fusiform gyrus. In both SAH and ATL procedures, the hippocampal and parahippocampal gyrus resections were carried posteriorly to the level of the tectal plate. MRI images from typical ATL resections completed at Emory University and the University of Washington are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

MRI scans demonstrating surgical resections: a) Tailored anterior temporal lobectomy (ATL) performed at the University of Washington – representative coronal, sagital, and axial slices in a patient undergoing left ATL; b) selective amygdalohippocampectomy performed at Emory University – representative coronal, sagital, and axial slices in a patient undergoing a right temporal lobe resection.

Naming and Recognition Tests

Famous face recognition and naming was assessed with the modified Iowa Famous Faces Test.7, 22 Common object naming was tested using the Boston Naming Test (BNT),23 which includes primarily man-made objects, and is a commonly employed clinical test in the presurgical evaluation of epilepsy patients. If an object or famous face could not be named, recognition was established based upon verbal description with sufficient detail to demonstrate knowledge. Detailed procedural information for administration and scoring is included in prior publications.5, 7

Statistical Analysis

We first examined each subject’s scores to determine if significant change between baseline and post-operative performance on each measure, which we considered the most clinically significant analysis. We used available reliable change indices (RCI) to determine meaningful change on the BNT.24 Impairment on the Iowa Famous Faces Test was based upon a 1 SD decline relative to healthy controls.

Fisher’s exact test was then used to compare the two surgical groups on frequency of cognitive change on both naming and recognition tasks. These analyses were completed without regard to side of surgery to examine the rate of significant decline on one or both of the measures. These analyses were repeated after the patients were grouped by each combination of surgery type and surgery laterality (dominant/nondominant) for each of the four conditions (2 cognitive tasks: naming and recognition; and 2 types of stimuli: famous faces and common objects).

Next, we examined baseline performance on the two naming and recognition tasks after grouping the patients by surgical type (SLAH vs. open resection) and side of surgery, using nonparametric analyses (e.g., Kruskal-Wallis Test, Mann-Whitney U Test) because data from these measures are not normally distributed.7 Exact tests were used to calculate p values. Because performance scores were reported as percentages, we treated these as proportions and carried out an arcsine-root transformation. This transformation controls for possible violations of the assumptions underlying the calculation of p-values and confidence limits that can be introduced when using a count or proportion as a dependent variable.25 For the BNT, we analyzed the same number of test items for each patient, making it unnecessary to use weighted proportions. We did not correct for multiple comparisons, as it would be worse to not recognize baseline differences if they did in fact exist in this study (i.e., baseline differences could confound our primary aim of determining if cognitive outcome differs by surgery type).

We created a percent change score on each measure for each patient based on their own baseline performance. We used correlational analysis to determine if any disease-related or demographic variables were associated with these percentage change scores, again treating each score as a transformed proportion as described above. These correlational analyses were intended to identify covariates, potentially affecting our primary outcome measures, for subsequent group level analyses.26 Despite no significant correlations being found, we used MTS status and age of seizure onset as covariates due to their presumed importance for naming among some researchers.27-29 We used Quade’s rank analyses of covariance to examine post-surgical change at the subgroup level for each naming and recognition task by type and side of surgery.30 This essentially serves as a nonparametric version of an analysis of covariance, allowing us to explore the possible effect of any potential mediating variables (e.g., MTS status).

RESULTS

Individual Level Analysis – Does Decline Occur Following Open Resection or SLAH?

Individual level classification revealed that most open resection patients declined on one or more naming or recognition tasks but those undergoing SLAH did not (32/39 vs. 0/19 patients) [p<.0001, Fisher’s exact test]. Only dominant TLE patients undergoing open resection declined on naming tasks, while all but one patient who declined on famous face recognition underwent nondominant open resection. One dominant patient declined significantly on both naming and recognition. However, her compromised recognition score appeared to be due to severe naming deficits experienced following surgery. For example, she had great difficulty providing verbal descriptions of any of the famous faces due to severely compromised language. Twenty-one of 22 dominant TLE patients undergoing open resection declined on at least one naming task, while none of 10 declined on either task after dominant SLAH, which is a highly significant difference [p<.001, Fisher’s exact test]. The proportion of dominant TLE patients declining on naming tasks by open resection type was 10/11 (90.9%) following tailored approaches, 2/2 (100%) after standard ATL, and 9/9 (100%) after SAH. Eleven of 17 (64.7%) nondominant TLE patients declined on famous face recognition after open resection, while none of 9 declined on this task after nondominant SLAH [p<.01, Fisher’s exact test]. The proportion of nondominant TLE patients declining on recognition of famous faces by open resection type was 4/6 (66.7%) after tailored resections, 1/2 (50%) following standard ATL, and 6/9 (66.7%) after SAH procedures. No patients exhibited significant baseline recognition deficits on the common object naming and recognition task (BNT), and no individuals experienced any post-operative decline in recognition of common objects following any surgery type.

Secondary Exploration of Relevant Disease-Related and Demographic Variables on Performance Change

We explored potential correlations between several disease-related (age of seizure onset, MTS status, and extent of lateral TL resection), outcome (post-surgical seizure freedom), and demographic variables (education) and performance change on the naming and recognition measures (See Table 2). We found no significant correlations between performance change and any of these variables in our sample. In contrast, naming outcome correlated strongly with side of surgery and type of surgery for both object types, and recognition of famous faces correlated with type of surgery. Table 3 shows the breakdown between post-surgical seizure status, laterality of seizure onset, and performance outcome, again highlighting that continued seizures do not explain performance differences.

Table 2.

Correlational Matrix for Naming and Recognition Outcomes (percent change) and Relevant Disease-Related, Demographic, and Treatment Variables for all Subjects (N=58).

| MTS Status |

Age of Seizure Onset |

Extent of Lateral Resection |

Post-Surgical Seizure Freedom (Engels) |

Type of Surgery (open vs. SLAH) |

Education | Side of Surgery |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston Naming Test – % Change |

r = −0.01 p = .98 |

r = −0.04 p = 0.76 |

r = −0.14, p = 0.40 |

r = −0.15, p = 0.28 |

r = 0.39, p < 0.01** |

r = 0.22, p = 0.15 |

r = 0.64, p = <.001** |

| Famous Faces – Naming – % Change |

r = 0.05, p = 0.74 |

r = −0.12, p = 0.37 |

r = −0.10, p = 0.73 |

r = −0.21, p = 0.16 |

r = 0.42, p = <.01** |

r = 0.25, p= 0.09 |

r = 0.38, p < 0.01** |

| Famous Faces – Recognition - % Change |

r = −0.06, p = 0.65 |

r = −0.06, p = 0.69 |

r = −0.14 p = 0.42 |

r = −0.001, p = 0.99 |

r = 0.36, p = <0.01** |

r = −0.10 p = 0.48 |

r = −0.21, p = 0.17 |

Note. Significant findings are highlighted with one (<.05) or two (<.01) asterisks. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were calculated for continuous variables. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were calculated for comparisons of ordinal and continuous variables.

Group Level Analyses – Exploring the Magnitude of Change

Baseline performance scores for both naming and recognition measures are presented in Table 4. For the BNT (common objects), no group exhibited baseline recognition deficits. Baseline naming performance for both common objects and famous faces was worse for both dominant TLE surgical groups as compared to the nondominant comparison groups. However, there was no significant baseline difference between the dominant TLE patients based on surgery type for naming on either task. Famous face recognition was poorer in both left and right TLE groups relative to healthy controls, with no significant differences observed related to surgical group assignment.

Table 4.

Presurgical Performance on Naming and Recognition Tasks by Object Type, Surgical Group, and Side of Surgery.

| Dominant Surgeries | Nondominant Surgeries | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Resection (n=22) |

SLAH (n=10) |

Open Resection (n=17) |

SLAH (n=9) |

||

| Mean SD (Range) |

Mean SD (Range) |

Mean SD (Range) |

Mean SD (Range) |

Significance | |

| BNT Naming (common objects) |

76.6ì 14.5 (31.7 to 95.0) |

70.3đĥ 22.4 (26.7 to 96.7) |

92.7ìđ 7.0 (78.3 to 100) |

85.6ĥ 11.1 (68.7 to 96.7) |

Χ2 (3, 54)= 18.2, p<.001 |

| BNT Recognition (common objects) |

92.9 10.2 (88.3 to 100) |

93.8 8.3 (88.3 to 100) |

94.7 11.7 (90 to 100) |

96.6 2.1 (91.7 to 100) |

n.s. |

| Famous Face Naming |

69.9ír 21.2 (18.5 to 97.4) |

67.0ࢠ23.6 (21.2 to 100) |

89.7í‡ 6.9 (79.1 to 100) |

89.9¢r 6.0 (79.5 to 96.5) |

Χ2 (3, 54)=16.8, p<.001 |

| Famous Face Recognition |

66.1 15.2 (40.0 to 90.8) |

72.9 16.7 (42.5 to 92.3) |

76.0 18.8 (32.8 to 95.4) |

74.0 16.6 (57.7 to 98.5) |

n.s. |

Note. Standard resections included both standard and tailored open ATL resections and selective amygdalohippocampectomies. All scores are presented as percent accuracies. Matching subscripts indicate that differences between subgroups are significant. Statistical analyses included a Kruskal-Wallis Test using transformed proportions followed by pairwise comparisons using the Mann-Whitney U Test for each measure (all with exact tests). SLAH = Stereotactic laser amygdalohippocampotomy; BNT = Boston Naming Test.

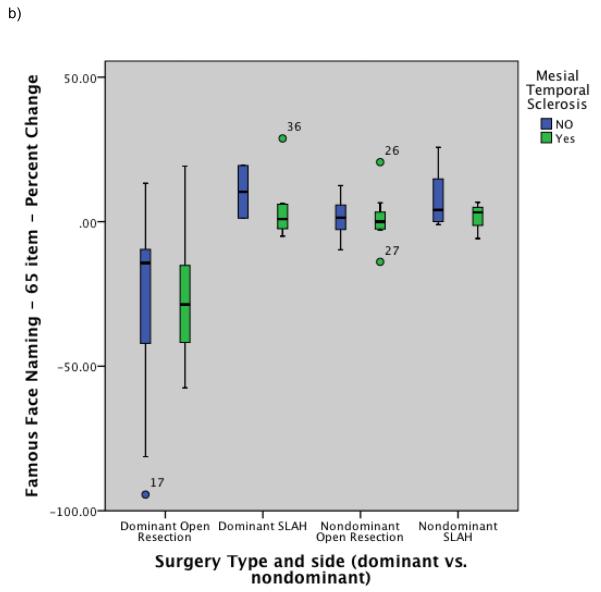

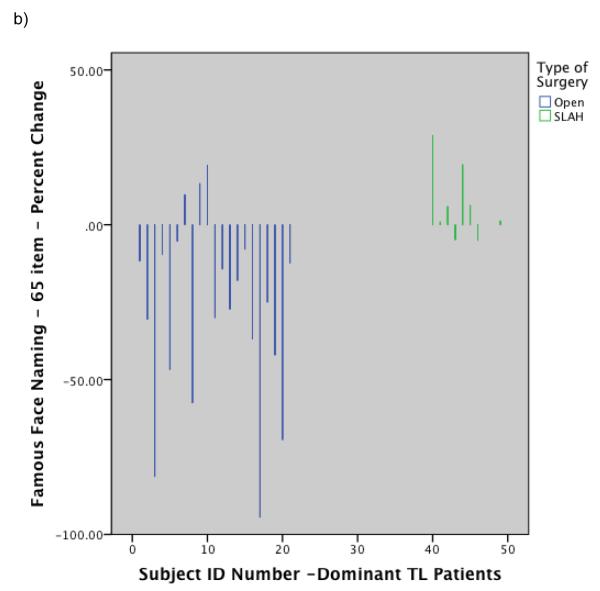

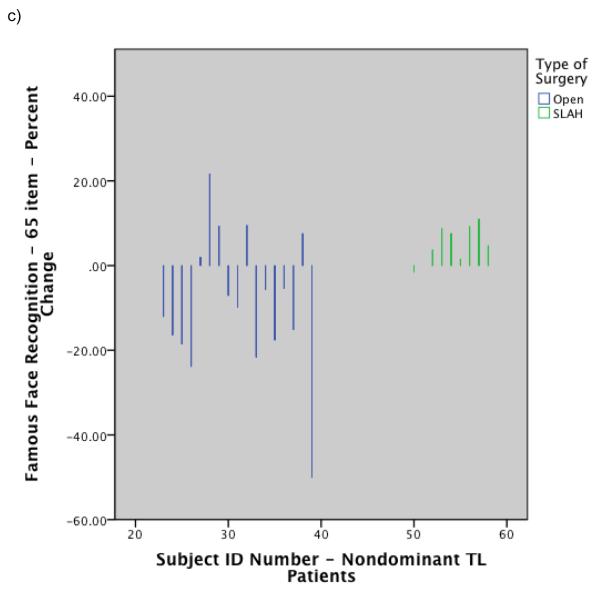

Group level comparisons of change in naming ability were completed using Quade’s rank analysis of covariance test with age of seizure onset and MTS used as covariates. This revealed that the dominant open resection patients performed significantly worse than all others post-surgically for both common objects (BNT) and famous faces (rank analysis of covariance: F=24.3, p<.0001, η2=.57, & F=11.2, p<.001, η2=.39, respectively). The effect size for the interaction of surgery type and side of surgery on naming outcome was large for both naming tests. All subgroups other than the dominant open resection group showed at least mild improvement on all naming measures, including the dominant SLAH subgroup. See Table 5 and Figure 3 for percentage change scores for all relevant performance measures. Additionally, Figure 4 contains histograms of change by surgery type at the individual level in order to highlight the magnitude and frequency of decline occurring in the open resection group versus the relative stability of the SLAH patients on these tasks. A table of raw scores for the BNT is also available for the dominant TLE patients online (online Table 1), further highlighting that significant decline occurred in the open resection group across all levels of baseline performance from impaired to normal.

Table 5.

Postsurgical Percent Change in Naming and Recognition by Object Type, MTS status, and Surgical Group.

| Dominant TL Surgeries | Nondominant TL Surgeries | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Resection (n=22) |

SLAH (n=10) |

Open Resection (n=17) |

SLAH (n=9) |

||

| Mean SD | Mean SD | Mean SD | Mean SD | ||

| BNT Naming Percent Change (common objects) |

Group (Range) |

−23.6† 17.6 (−62.0 to 4.7) |

8.6 25.7 (−7.1 to 75.0) |

1.9 4.8 (−6.7 to 11.5) |

3.2 3.7 (−1.9 to 9.8) |

| MTS+ | −20.1 13.7 | 8.2 29.6 | 2.4 5.2 | 2.1 3.4 | |

| MTS− | −25.6 20.1 | 9.6 18.3 | 1.4 4.7 | 3.7 4.0 | |

| Famous Face Naming Percent Change |

Group (Range) |

−28.3† 30.5 (−94.2 to 19.2) |

9.4 12.5 (−4.9 to 28.8) |

1.4 8.1 (−13.9 to 20.6) |

7.6 12.6 (−5.8 to 25.7) |

| MTS+ | −26.2 24.0 | 4.6 11.5 | 1.3 9.2 | 1.4 6.4 | |

| MTS− | −28.3 33.9 | 10.3 12.8 | 1.5 7.2 | 7.9 10.4 | |

| Famous Face Recognition Percent Change |

Group (Range) |

0.5 13.2 (−22.7 to 25.0) |

4.2 5.5 (−3.0 to 15.8) |

−9.0 16.5 (−50.0 to 21.6) |

5.0 4.9 (−1.5 to 11.0) |

| MTS+ | −1.3 16.2 | 2.0 3.2 | −6.3 11.5 | 6.6 5.8 | |

| MTS− | 1.6 11.4 | 11.9 5.6 | −12.0 21.3 | 3.7 4.0 | |

| Seizure Outcome | Engel I: 11 (10) Engel II: 5 (4) Engel III: 3 (4) Engel IV: 3 (4) |

Engel I: 7 Engel II: 1 Engel III: 2 Engel IV: 0 |

Engel I: 13 (12) Engel II: 2 (2) Engel III: 2 (2) Engel IV: 0 (1) |

Engel I: 4 Engel II: 0 Engel III: 2 Engel IV: 3 |

|

Note. Open resections included both standard and tailored open ATL resections and selective amygdalohippocampectomies. MTS+ = presence of mesial temporal sclerosis; MTS− = absence of mesial temporal sclerosis; BNT = Boston Naming Test.

Results for the standard open resections represent 1-year post-surgical follow-up, while results from the laser ablation group reflect 6-month follow-up.

- Engel’s classification ratings are provided at 6 month and 1 year for the standard resections (1 year data included in parentheses).

- Analysis of covariance and subgroup comparison using studentized t-tests demonstrates that subgroups with marked with a superscript significantly differs from all other subgroups at the specified level of significance (p<.001).

Figure 3.

Post-surgical percent change on naming and recognition tests by surgical group and MTS status: a) Naming performance on Boston Naming Test (common objects); b) Naming performance on modified Iowa Famous Faces Test; c) Recognition performance on modified Iowa Famous Faces Test. Note. MTS+ = patients with mesial temporal sclerosis based on neuroimaging; MTS− = patients without mesial temporal sclerosis based on neuroimaging. SLAH = stereotactic laser amygdalohippocampotomy.

Figure 4.

Histograms showing individual level performance change by type of surgery: a) Change in BNT raw score for dominant temporal lobe cases by surgery type; b) Change in Famous Face naming performance on modified Iowa Famous Faces Test for dominant temporal lobe cases by surgery type; c) Change in Famous Face recognition performance on modified Iowa Famous Faces Test for nondominant temporal lobe cases by surgery type. Note. SLAH = stereotactic laser amygdalohippocampotomy; BNT = Boston Naming Test; TL = Temporal Lobe.

A direct comparison of the two surgical groups on change in recognition of famous faces following anteromedial TL resection was also significant using a rank analysis of covariance with age of seizure onset and MTS status as covariates (rank analysis of covariance: F=3.9, p<.02, η2=.19). The effect size was small to medium for this finding. Of note, while the majority (11/17) of right anteromedial TL surgical patients undergoing open resection declined on famous face recognition (percent change: X= −17.0, SD=9.5) several patients improved on the task post-operatively (percent change: X=7.4, SD=8.9). With this surgical group having two distinct cognitive outcomes, the overall group mean appears to obscure a decline present in a substantial number of patients. The differential outcome between the two right TL surgical techniques is therefore easier to appreciate in the individual level analyses. Left anteromedial TL surgical patients tended to improve slightly on famous face recognition regardless of surgery type. There was no significant decline in recognition of common objects from the BNT for any subgroup. See Table 5 and Figure 3 for percent change scores for famous face recognition. Figure 4 includes a histogram reflecting magnitude of change on Famous Face recognition at the individual level by surgery group.

As shown in Table 3, presence of MTS does not appear to be significantly related to naming and recognition performance, as confirmed with a series of non-significant Mann Whitney U Tests. Engel I classifications were similar for SLAH and standard resection patients (57.9% vs. 61.5%, respectively) at 6 month follow-up. There was no significant co-variation between seizure freedom and task performance, demonstrating that the absence of decline in SLAH patients did not result from failure to ablate sufficient medial TL volume. Of note, when including the 2 SLAH patients excluded from this study, the seizure freedom rate was 52.4% (11/21) at 6 months after surgery.

DISCUSSION

TLE patients undergoing stereotactic laser amygdalohippocampotomy had better outcomes for naming and recognition of famous faces and naming of common objects than those receiving standard resections (tailored or open ATL or SAH). The majority of patients in the open resection group experienced a decline in either naming or recognition functions, depending on side of surgery (dominant resections affected one or more naming task and nondominant resections affected famous face recognition). Conversely, performance accuracy remained unchanged or improved in all patients in the SLAH group. Although this is a small series of SLAH patients, the initial cognitive outcome difference between groups is striking. These preliminary data suggest that SLAH may preserve important category-related recognition and naming abilities, cognitive functions that are often affected by open resection procedures for mesial TLE surgery.

Differences in naming and object recognition outcome were not explained by associations with post-surgical seizure freedom status, presence or absence of MTS, educational differences, or extent of lateral TL resection. Additionally, worse performance in the open resection group was not driven by any one type of open surgical approach. Significant performance declines were just as likely to occur following the SAH and standard ATL procedures performed at Emory as they were after the tailored ATL resections performed at the University of Washington. It is sometimes assumed that the resections in the latter group exceed the resection parameters of the standard (Spencer) resection. Yet in the current sample, only one of 16 tailored resections exceeded the 3.5 - 4 cm lateral extent of the standard resection (i.e., one nondominant case was extended 4.8 cm, while the average for the 18 patients was 3.2 cm for the dominant resections and 3.3 cm for the nondominant resections).

There were no baseline differences in task performance between patients undergoing each surgery type to potentially explain outcome differences. Of note, patients undergoing each surgical procedure in the current study ranged from severely impaired to average at baseline on the assessed tasks. Significant decline occurred with the open resection patients across all range of performance, while patients undergoing SLAH tended to remain stable or showed slight improvement. The SLAH sample included several individuals who were employed in high-level professions (e.g., physician, school teacher) who underwent dominant hippocampal ablations. These patients were considered to be at a high risk of decline with standard ATL surgery based on their baseline level of function. Finally, significant changes in performance, even in the patients at the low end of the spectrum of functioning have measurable life impact. For example, one mildly intellectually disabled individual who experienced significant gains on naming measures was described as “better able to communicate” by his family, and began to participate in a full-time sheltered workshop for the first time in his life.

Since SLAH and standard resections both ablate the hippocampus (pes and posteriorly at least to the level of the mid-body), but result in different outcomes for naming and recognition of objects and famous faces, the hippocampus does not appear to be an essential component of neural networks underlying these functions. More specifically, the SLAH in this series ablates the amygdala and hippocampus, variably sparing the parahippocampal structures beyond the subiculum. Moreover, the occipital trajectory of the cannula completely spares temporal stem WM pathways. In contrast, the standard resections in this series, whether anteromedial temporal lobectomy or SAH, incorporate parahippocampal gyrus, and sometimes more lateral gyri (e.g., fusiform), into the resection. Significant damage also occurs to the temporal stem WM in gaining access to the mesial structures during open resections, albeit in a different pattern depending on the type of open surgery. In sum, while indirect evidence has linked the hippocampus to naming and recognition (e.g., fMRI activation patterns, correlation of volumetric and behavioral data), we present the first direct evidence that the hippocampus proper may not be an essential component of the neural networks underlying these functions. We believe that it may have a minimal role in these processes, although more work is needed to determine if this relates to misconceptions about the function of the hippocampus or whether it may reflect a reorganization of function in epilepsy patients. Such functions may have become reorganized in the brains of epilepsy patients prior to surgery, or, alternatively, leaving more brain regions and WM pathways intact may provide a better substrate for functional recovery after surgery. Of note, substantial research completed in semantic dementia and congenital prosopagnosic patients has highlighted the importance of the lateral TL regions for both naming and recognition processes and the relative lack of involvement of mesial TL structures in these processes.11, 15, 31

This is also the first study to present pre- and post-surgical data involving famous face naming and recognition in the same patient cohort, directly establishing declines in these areas as potential adverse surgical complications. Prior work has been restricted to cross-sectional data, comparing different samples of pre- and post-surgical patients to one another,5-7, 32-33 or small case series with a small number of patients assessed before and after surgery.8, 34 When assessing more than one object category, nearly every open resection patient experienced significant naming declines following left (dominant) anteromedial TL surgery. Reports in other patient populations have linked adverse naming outcome to poor functional recovery, including decreased success in returning to work.9 Future work needs to examine naming speed and performance on even broader categories of objects in TLE surgery, and to relate these functions to performance in other cognitive domains and functional recovery.

Object recognition of any type has rarely been documented in TLE patients,5-8, 32 and such functions are not routinely assessed in clinical practice. A few prior studies have shown that presurgical right (nondominant) TLE patients may experience baseline deficits in famous face recognition.5, 32-33 However, the current findings demonstrate that declines in famous face recognition occur in a large number of patients following right (nondominant) TL resection. While group level differences were present favoring SLAH over open resection in this regard, outcome for the right post-surgical open resection group was bivariate in nature (11 patients exhibited significant decline while 6 exhibited no change or significant improvement). Future studies are needed to determine if identifiable surgical distinctions may underlie these differential outcomes. For example, it may be that key brain regions, such as the fusiform gyrus or WM pathways, are spared in those with better outcome. Such studies will benefit greatly from detailed structural volumetric and diffusion tensor imaging tractography data in order to elucidate potential key brain-behavior relationships. We have suggested that famous face recognition deficits may reflect a selective “prosopagnosia” in right TLE patients that results from disrupting one or more aspects of a larger neural network involving the temporal pole, fusiform gyrus, and ventral visual processing stream.7 This would fit with recent work in patients with congenital prosopagnosia, which demonstrates that their poor face processing abilities correlate with DTI abnormalities involving their ventral visual processing streams (particularly of the right hemisphere).15 Preliminary work from our group using DTI parameters also suggests a relationship between nondominant ventral visual pathways and famous face recognition performance both pre- and post-surgically, with decline in function related to decrements in connectivity of specific right hemisphere pathways.35 Overall, deficits in face processing can compromise social and vocational functioning by making it difficult to recognize familiar individuals and to learn perceptual-semantic/linguistic relationships (e.g., face-name learning), and need to be recognized and explored as a potential area of decline in some open resections.

The seizure freedom rate for our open resection group is below what is often cited for anterior TL resections. Standard anterior temporal lobectomy has been reported to result in seizure freedom rates of 70% or better,36-37 while outcome of SAH was reported to be about 8% lower in a recent meta-analysis.38 Although our rate of approximately 62% seizure freedom in the open resection sample would appear slightly lower than expected, our numbers reflect a “real-world” approach, including all patients who underwent surgery in our programs (intent-to-treat), rather than highly selected samples. Many of our patients from both the open and SLAH samples would have been excluded from the seizure outcome papers reported previously. Such excluded patients would include those with MRI evidence of abnormalities outside of the temporal lobes and/or not restricted to a single temporal lobe, patients without MRI evidence of MTS, patients experiencing epilepsy in the context of head trauma or broader neurological disease (e.g., encephalitis), and a few patients with bitemporal seizure onset in both open and SLAH surgical groups. Therefore, seizure freedom rates would be expected to be higher in both surgical groups if stricter inclusion and exclusion criteria were used. We have shown that the potential for cognitive decline appears greater in patient cohorts that tend to be excluded from many studies.39 Having real-world estimates of seizure freedom rates and possible cognitive decline appear much needed in clinical practice. Of note, seizure freedom rates for SLAH need to be extended at least to a 2-year post-surgical follow-up span to be meaningfully compared to available open resection data.

We chose not to initially focus on episodic memory outcome, as our research protocol has been more heavily focused on naming and recognition paradigms. Nevertheless, our preliminary data in this area also suggests outcome may be more favorable following SLAH than open resection.40 Future research is needed to establish if there are differential advantages in episodic memory outcome with SLAH, and to establish the mechanisms by which such differences may occur.

Limitations

As current data are preliminary, due to small sample sizes and a short follow-up period for seizure classification, additional research in larger cohorts is warranted. Extension of this work to other cognitive domains is needed (particularly episodic memory), along with studies of efficacy for seizure control, quality of life, and relative costs of health care utilization. While the post-surgical Engel seizure classification rates were derived at 6-month follow-up for both the open resection and SLAH samples, naming and recognition assessment was compared from different time points (e.g., 6-month follow-up for SLAH and 1-year follow-up for open resection). This allowed more time for functional recovery for the open resection group, which should have biased the studied towards finding better outcome in the open resection group. Instead, our findings favor the SLAH sample in all areas. In contrast, one might wonder if the shorter follow-up time span led to greater practice effects for the SLAH sample. Of note, however, as baseline neurocognitive assessment occurred an average of 2-months prior to surgery, the actual time between assessments was typically 8-9 months in the majority of cases. Additionally, we have more recently started assessing all patients at 6-month and 1-year intervals, and the open resection patients are already demonstrating deficits at this earlier time point.

Finally, future research needs to assess the clinical significance of declines in famous face recognition and naming. At present, there are no RCI or standard based regression scores for these measures. Future studies also need to follow patients undergoing SLAH for longer durations to determine if seizure freedom will persist. Even with open resections, seizure improvement rates sometimes decline over time in a subset of patients, suggesting the possibility that the procedure disrupted a network but likely failed to remove it altogether. Nevertheless, initial seizure freedom rates are promising, and for those not rendered seizure free by SLAH, open resection can still be pursued without any increased surgical difficulty.

Conclusions

Our initial experience with SLAH suggests that it is a promising surgical approach that appears to minimize aspects of the cognitive morbidity associated with open surgical resection. The highly selective nature of this procedure also allows for careful study of brain-behavior relationships that should enable us to better elucidate the neural networks of the TL regions in a manner never before possible in humans. Future research with larger cohorts of patients is required to definitively determine the relative cognitive impact of SLAH to open resection. If cognitive outcome is shown to be better with SLAH, we believe this approach will be appealing to many patients who are currently reluctant to undergo invasive surgery to control their seizures due to fears of compromised post-surgical function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Dr. Drane has received two grants from the NIH/NINDS, which have partially supported his work on this project at both Emory University and the University of Washington (K23 NSO49100 & K02 NS070960). These grants provided salary support for Dr. Drane and his laboratory staff, and covered the cost of neuroimaging and other study related expenses. Funding was also provided to Emory University by way of a clinical study agreement from Visualase, Inc., which develops products related to the research described in this paper. These funds assisted with some of the study-related costs of the patients undergoing the SLAH procedure only.

Our thanks and appreciation is extended to our study coordinator, Gloria Novak, and a number of research assistants and psychometricians who provided support for the project (Natasha Ramsey, Paul Woody, Gail Rosenbaum, Tom Erickson, Nathan Hantke, Jaclyn Tucker, Brie Sullivan, Eric Samuelson, and Greg Tesnar). We would also like to thank Robert Smith for his assistance with MRI acquisition at Emory University.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Drane has received three grants from the NIH/NINDS, which have supported his work in this area at both Emory University and the University of Washington (K23 NSO49100, K02 NS070960, R01NS088748). These grants provided salary support for Dr. Drane and his laboratory staff, and covered the cost of neuroimaging and other study related expenses.

Funding was provided to Emory University by way of a clinical study agreement from Visualase, Inc., which develops products related to the research described in this paper. These funds assisted with the study-related costs of the patients undergoing the SLAH procedure only. In addition, Dr. Gross serves as a consultant to Visualase and receives compensation for these services. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by Emory University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

Dr. Gross also receives consulting fees from Medtronic, Eli Lilly, Neuropace, St. Jude Medical Corp., Deep Brain Innovations, and Duke University.

Dr. Loring reports receiving consulting fees from NeuroPace and Supernus and current grant support from PCORI and NIH; receives royalties from Oxford University Press; serves on the Professional Advisory Board for the Epilepsy Foundation, and sits on the editorial boards for Epilepsia, Epilepsy Research, and Neuropsychology Review. He also receives funds related to neuropsychological assessment of patients with epilepsy including Wada testing.

Dr. Meador reports active grants included NIH/NINDS 2U01-NS038455-11A1, NIH R01 NS076665-01A1, PC0RI 527 and a UCB Pharma grant; other grants include money from: NIH Epilepsy Foundation, Cybertronics, GSK, Eisai, Marius, Myriad, Neuropace, Pfizer, SAM Technology, Schwartz Bioscience (UCB Pharma) and UCB Pharma; consultancies: Epilepsy Study Consortium which received money from multiple pharmaceutical companies: Eisai, Neuropace, Novartis, Supernus, Upsher Smith Laboratories, UCB Pharma and Vivus Pharmaceuticals; funds from consulting were paid to his university; travel support from Sanofi Aventis to a lecture in 2010; clinical income from EEG procedures and care of neurological patients.

Dr. Miller receives research funding from the NIH, CDC, Pfizer, UCB Pharma, and Sunovion. He is on the editorial boards for Neurology® and Epilepsy Currents.

No other co-investigators have any financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to report related to this project.

References

- 1.Helmers SL, Gross RE, Willie JT. Short-term healthcare utilization in stereotactic MRI-guided laser ablation for treatment of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2013;54(Suppl. 3):190.P602. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curry DJ, Gowda A, McNichols RJ, Wilfong AA. MR-guided stereotactic laser ablation of epileptogenic foci in children. Epilepsy and Behavior. 2012;24:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.04.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willie JT, Laxpati NG, Drane DL, et al. Real-time magnetic resonance-guided stereotactic laser amygdalophippocampotomy (SLAH) for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurosurgery. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000343. Epub 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saykin AJ, Stafiniak P, Robinson LJ, et al. Language before and after temporal lobectomy: Specificity of acute changes and relation to early risk factors. Epilepsia. 1995;33:1071–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drane DL, Ojemann GA, Aylward E, et al. Category-specific naming and recognition deficits in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:1242–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glosser G, Salvucci AE, Chiaravalloti ND. Naming and recognizing famous faces in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2003;61:81–86. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073621.18013.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drane DL, Ojemann JG, Phatak V, et al. Famous face identification in temporal lobe epilepsy: Support for a multimodal integration model of semantic memory. Cortex. 2013;49:1648–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drane DL, Ojemann GA, Ojemann JG, et al. Category-specific recognition and naming deficits following resection of a right anterior temporal lobe tumor in a patient with atypical language lateralization. Cortex. 2009;45:630–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moritz-Gasser S, Herbet G, Maldonado IL, Duffau H. Lexical access speed is significantly correlated with the return to professional activities after awake surgery for low-grade gliomas. Journal of Neurooncology. 2012;107:633–641. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0789-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fine DR. A life with prosopagnosia. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 2012;29:354–359. doi: 10.1080/02643294.2012.736377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mummery CJ, Patterson K, Price CJ, et al. A voxel-based morphometry study of semantic dementia: Relationship between temporal lobe atrophy and semantic memory. Annals of Neurology. 2000;47:36–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonelli SB, Powell R, Thompson PJ, et al. Hippocampal activation correlates with visual confrontational naming: fMRI findings in controls and patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Research. 2011;95:246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seidenberg M, Geary E, Hermann B. Investigating temporal lobe contribution to confrontational naming using MRI quantitative volumetrics. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2005;11:358–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamberger MJ, Seidel WT, McKhann GM, Goodman RR. Hippocampal removal affects visual but not auditory naming. Neurology. 2010;74:1488–1493. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dd40f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas C, Avidan G, Humphreys K, et al. Reduced structural connectivity in ventral visual cortex in congenital prosopagnosia. Nature and Neuroscience. 2009;12:29–31. doi: 10.1038/nn.2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarubbo S, De Benedictis A, Maldonado IL, et al. Frontal terminations for the inferior fronto-occipital fascicle: Anatomical dissection, DTI study and functional considerations on a multi-component bundle. Brain Structure and Function. 2013;218:21–37. doi: 10.1007/s00429-011-0372-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun MM. The fusiform face area: A module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:4302–4311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04302.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tranel D, Damasio H, Damasio AR. A neural basis for the retrieval of conceptual knowledge. Neuropsychologia. 1997;35:1319–1327. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silbergeld DL, Ojemann JG. The tailored temporal lobectomy. Neurosurgical Clinics of North America. 1993;4:273–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKhann GM, 2nd, Schoenfeld-McNeill J, Born DE, et al. Intraoperative hippocampal electrocorticography to predict the extent of hippocampal resection in temporal lobe epilepsy surgery. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2000;93:44–52. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.1.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ojemann G, Ojemann J, Lettich E, Berger M. Cortical language localization in left, dominant hemisphere. An electrical stimulation mapping investigation in 117 patients. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1989;71:316–326. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.71.3.0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Damasio H, Grabowski TJ, Tranel D, et al. A neural basis for lexical retrieval. Nature. 1996;380:499–505. doi: 10.1038/380499a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. Boston Naming Test. Lea and Febiger; Philadelphia: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin R, Sawrie S, Gilliam F, et al. Determining reliable cognitive change after epilepsy surgery: Development of reliable change indices and standardized regression-based change norms for the WMS-III and WAIS-III. Epilepsia. 2002;43:1551–1558. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.23602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zar JH. Biostastistical analysis. Prentice Hall; New Jersey: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pocock SJ, Assmann SE, Enos LE, Kasten LE. Subgroup analysis, covariate adjustment and baseline comparisons in clinical trial reporting: Current practice and problems. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21:2917–2930. doi: 10.1002/sim.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hermann BP, Wyler AR, Somes G. Language function following anterior temporal lobectomy: Frequency and correlates. Neurosurgery. 1991;35:52–57. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.74.4.0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stroup ES, Langfit JT, Berg M, et al. Predicting verbal memory decline following anterior temporal lobectomy. Neurology. 2003;60:1266–1273. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000058765.33878.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin RC, Kretzmer T, Palmer C, et al. Risk to verbal memory following anterior temporal lobectomy in patients with severe left-sided hippocampal sclerosis. Archives of Neurology. 2002;59:1895–1901. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.12.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quade D. Rank analysis of covariance. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1967;62:1187–1200. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snowden JS, Thompson JC, Neary D. Knowledge of famous faces and names in semantic dementia. Brain. 2004;127:860–872. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seidenberg M, Griffith R, Sabsevitz D, et al. Recognition and identification of famous faces in patients with unilateral temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:446–456. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benke T, Kuen E, Schwarz M, Walser G. Proper name retrieval in temporal lobe epilepsy: Naming of famous faces and landmarks. Epilepsy and Behavior. 2013;27:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukatsu R, Fujii T, Tsukiura T, et al. Proper name anomia after left temporal lobectomy: A patient study. Neurology. 1999;52:1096–1099. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.5.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drane DL, Glasser MF, Voets NL, et al. Key pathways for visual naming and object recognition revealed by diffusion tensor imaging probabilistic tractography in epilepsy surgery patients. Neurology. in press. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tellez-Zenteno JF, Dhar R, Wiebe S. Long-term seizure outcomes following epilepsy surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain. 2005;128:1188–1198. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiebe SB, Girvin JP, Eliasziw M. A randomized controlled trial of surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:311–318. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108023450501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Josephson CB, Dykeman J, Fiest KM, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of standard vs selective temporal lobe epilepsy surery. Neurology. 2013;80:1669–1676. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182904f82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drane DL, Stroup ES, Ojemann JG, et al. Dominant TLE patients exhibit worse post-surgical naming outcome when neuroimaging is normal or reflects diffuse injury rather than classic mesial temporal sclerosis. Epilepsia. 2006;47:96. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drane DL, Loring DW, Voets NL, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy surgical patients undergoing MRI-guided sterotactic laser ablation exhibit better episodic memory outcome as compared to standard surgical approaches. Epilepsy Currents. 2014;14(Suppl. 1):468.B07. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.