Abstract

The stress response is characterized by the coordinated engagement of central and peripheral neural systems in response to life-threatening challenges. It has been conserved through evolution and is essential for survival. However, the frequent or continual elicitation of the stress response by repeated or chronic stress, respectively, results in the dysfunction of stress response circuits, ultimately leading to stress-related pathology. In an effort to best respond to stressors, yet at the same time maintain homeostasis and avoid dysfunction, stress response systems are finely balanced and co-regulated by neuromodulators that exert opposing effects. These opposing systems serve to restrain certain stress response systems and promote recovery. However, the engagement of opposing systems comes with the cost of alternate dysfunctions. This review describes, as an example of this dynamic, how endogenous opioids function to oppose the effects of the major stress neuromediator, corticotropin-releasing hormone, and promote recovery from a stress response and how these actions can both protect and be hazardous to health.

Introduction

In response to perceived life-threatening stimuli, several physiological processes—including the following: glucocorticoid release into the circulation to mobilize energy resources and modulate immune reactions; increases in heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration; changes in gastrointestinal motility; increases in arousal; and modification of behavior—are synchronized in an effort to best cope with the challenge. This complex yet finely coordinated acute stress response is necessary for survival and has been conserved throughout evolution. A built-in component of this response that is essential for health is the ability to terminate the processes once the stressor is no longer present.

Stress exposure is associated with many neuropsychiatric diseases, including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance abuse, and Alzheimer's disease as well as medical conditions, including obesity, cardiovascular disease, inflammatory disorders, and irritable bowel syndrome [1–8]. The clinical impact of stress derives from the ability of repeated or chronic stressors to produce enduring dysfunctions in stress response systems or stress neuromediators such that they become overactive or are not counter-regulated. Given the prevalence of stressors in the dynamic environment of an animal, mechanisms that limit activity of stress response systems and promote fast recovery to pre-stress levels are essential. Feedback inhibition of paraventricular hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) neurons by rising levels of glucocorticoids is a classic example of an acute stress recovery mechanism [9]. However, in the face of either repeated or chronic stress, other systems or neuromodulators that oppose “pro-stress” systems or neuromediators may be engaged. Examples of opposing factors that have been identified are neuropeptide Y, endocannabinoids, urocortins, and endogenous opioids [6,10–16]. Here, we describe the opposing interactions between the CRH system that initiates many components of the stress response and endogenous opioids that restrain the effects of CRH on a major stress response system, the brain norepinephrine system. The importance of a balance between these two neuromodulators and the implications of this for individual vulnerability to stress-related disorders are emphasized. Finally, the idea that systems that oppose the stress response can be the basis for alternate pathologies is discussed.

Corticotropin-releasing hormone: initiating the stress response

A major advance in stress neurobiology was the isolation and characterization by Vale and colleagues [17] (1983) of CRH as the paraventricular hypothalamic neurohormone that is released into the median eminence to initiate anterior pituitary adrenocorticotropin secretion into the general circulation, a response that is generally considered a hallmark of stress. This discovery opened a portal that allowed the generation of new hypotheses for how the brain organizes the multicomponent acute response to stressors and how the mechanisms by which it does this underlie stress-related pathology. Anatomical, electrophysiological, and behavioral studies from numerous laboratories provided convergent evidence for a parallel function of CRH as a neuromodulator that is released by stressors in brain regions underlying autonomic, behavioral, and cognitive responses to stress [18,19]. For example CRH-containing axon terminals and CRH receptors were identified in the dorsal vagal complex and brainstem regions that regulate autonomic function and in limbic regions such as the central nucleus of the amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis that are involved in emotional output [20,21]. Central CRH administration was demonstrated to mimic many of the autonomic and behavioral aspects of the stress response even in hypophysectomized rats [22–32]. Importantly, many stress-elicited effects were demonstrated to be prevented or reversed by administration of CRH antagonists or were found to be absent in animals with genetic deletions of CRH receptors [16,33–44]. Together, the findings led to the compelling notion that coordinated CRH release in specific neural circuits integrates the different limbs of the stress response. Although the autonomic and behavioral processes initiated by CRH are adaptive in responding to life-threatening challenges, if they were engaged in the absence of such a challenge or if they persisted long after the challenge was terminated, this would be considered pathological. Consistent with this, many stress-related disorders, including depression, PTSD, and irritable bowel syndrome, have been attributed to excessive CRH that is not counter-regulated [6,45–47].

Endogenous opioids: opposing the stress response

The endogenous opioids and their receptors were discovered and characterized by several different groups in the early 1970s [48–53]. Four major families that derive from precursors that are encoded by distinct genes have been identified: preproopiomelanocortin, preproenkephalin, preprodynorphin, and proorphanin [52,54–59]. The active peptides that are cleaved from these precursors produce their effects primarily through actions on μ-opioid receptors, κ-opioid receptors, δ-opioid receptors and ORL-1 G-protein coupled receptors [60,61]. Opioids are best recognized for their analgesic activity. In addition to inhibiting sensation, opioid analgesia involves a blunting of the negative affective component of pain [62]. Pain shares characteristics with other stressors in that it signals physical threat, alters autonomic function, increases arousal, redirects attention, induces avoidance behaviors, and generates negative affect [63]. The ability of endogenous opioids to counter cognitive and affective components of pain may represent a more global function to counteract these components of the response to stressors in general. Notably, these opioid actions are attributed primarily to the μ-opioid receptor (MOR), for which β-endorphin, endomorphin, and enkephalins are more selective [64–66]. In contrast, aversive effects that in some ways resemble stress have been attributed to the dynorphin-κ-opioid receptor system [67]. An anti-stress function of endogenous opioids is further supported by substantial evidence that stressors of different modalities elicit their release. For example, many stressors, including those that are non-noxious, elicit an analgesia that is cross-tolerant with morphine and is antagonized by naloxone [68–71]. In subjects with PTSD, combat-related stimuli elicit naloxone-sensitive analgesic responses [72,73]. Repeated social stress releases sufficient endogenous opioids to create a state of opioid dependence that is expressed as withdrawal signs when naloxone is administered (see below). Finally, stressors have also been demonstrated to increase preproenkephalin mRNA in certain brain regions or β-endorphin in plasma [74–78].

The distribution of enkephalin overlaps that of CRH in brain regions that mediate endocrine, behavioral, and autonomic components of the stress response, including the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus, central amygdalar nucleus, bed nucleus of stria terminalis, parabrachial nucleus, and nucleus tractus solitaries [21,66,79]. Taken with their opposing “pro-stress” and “anti-stress” effects, respectively, the anatomical overlap between CRH and endogenous opioids in the brain positions these neuromodulators to work in concert to fine-tune neuronal activity in response to stressors. In this situation, an imbalance favoring either neuromodulator may have pathological consequences. A specific example of this is seen with brain locus coeruleus (LC)-norepinephrine (NE) neurons, which are targeted by both CRH and enkephalin inputs that have opposing actions that are engaged during stress [80–82].

The locus coeruleus-norepinephrine stress response system

The LC-NE system is activated by stressors in parallel with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and this activation plays an integral role in initiating and maintaining arousal and facilitating certain behavioral and cognitive responses to stress [83]. The LC is a compact pontine nucleus of norepinephrine-containing neurons [84,85]. Through an extensive axonal projection system, the LC serves as the primary source of brain norepinephrine [86]. The physiological characteristics of LC neurons have implicated this system in arousal, particularly in response to salient stimuli [87–89]. LC neurons exhibit different patterns of firing that are associated with different cognitive states [90,91]. For example, a phasic pattern of LC neuronal discharge, when the overall rate is moderate but the cells are highly activated by sensory stimuli, is associated with focused attention and staying on-task. In contrast, a high tonic mode of LC discharge is characterized by high-frequency spontaneous discharge and minimal activation by discrete sensory stimuli and is associated with scanning attention and behavioral flexibility, a mode of activity that would be adaptive in coping with a stressor. The ability of LC neurons to switch between phasic and tonic modes of discharge facilitates rapid behavioral adjustments in a dynamic environment.

Co-regulation of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system by opposing CRH and opioid influences: a fine balance

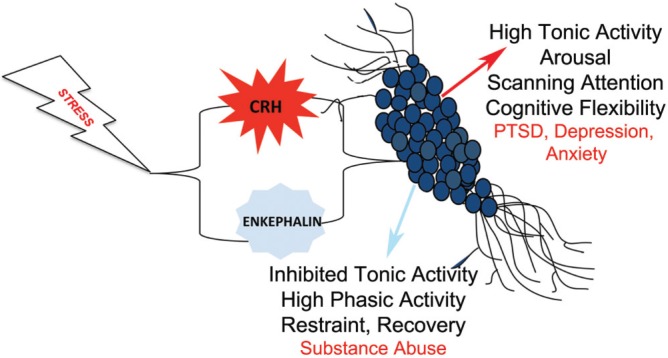

LC neurons are poised for co-regulation by CRH and enkephalin because they receive convergent input from CRH- and enkephalin-containing axon terminals [80,81]. Activation of CRH1 and MOR on LC neurons has opposing electrophysiological effects. CRH1 signaling increases LC neuronal discharge frequency and favors a high tonic mode of activity [92,93], whereas MOR signaling inhibits LC neurons and favors a phasic mode of activity [94] (Figure 1). Acute stressors, such as a hypotensive challenge or exposure to predator odor, mimic the electrophysiological effects of CRH on LC neurons [95–98]. The increased arousal and cognitive flexibility associated with a shift toward high tonic LC activity would be adaptive in coping with a life-threatening stimulus. Administration of a CRH antagonist into the LC during stress blocks stress-induced LC activation, indicating that it is mediated by CRH neurotransmission [95–98]. Moreover, it reveals a prominent inhibition that can be prevented by opioid antagonists [95,97]. In the presence of opioid antagonists alone, stressors produce an enhanced LC activation and one that takes longer to recover to baseline after stressor termination [95,97]. These findings indicate that stressors engage both CRH and opioid inputs to the LC (Figure 1). The net effect of acute stress on LC activity is dominated by CRH excitation and this is adaptive in the acute situation. The co-release of endogenous opioids serves to restrain stress-induced excitation and also promotes recovery when the stressor is no longer present (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic depicting the consequences of opposing corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)-opioid interactions on locus coeruleus (LC) neurons.

Stress engages both CRH and enkephalin inputs that converge on LC neurons. CRH increases tonic and decreases phasic LC discharge and this is associated with increased arousal, a shift from focused to scanning attention, and enhanced cognitive flexibility, effects that would be adaptive in response to an acute stressor. Activation of μ-opioid receptors on LC neurons inhibits LC tonic discharge and facilitates phasic activity. These opposing effects serve to restrain the effects of CRH and facilitate recovery after the stressor is terminated. Shifts in the CRH-opioid balance can promote different pathology. An imbalance in favor of CRH would increase vulnerability to stress-related disorders characterized by hyperarousal. An imbalance in favor of endogenous opioids would increase vulnerability to substance abuse. Abbreviations: PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

The opposing influences of CRH and endogenous opioids on LC activity must be finely tuned for the system to maintain homeostasis. An imbalance between CRH and opioid influences can have different clinical consequences and this may be a basis for individual resilience/vulnerability to stress. For example, a decreased opioid influence in this circuit would be expressed as an exaggerated and more enduring arousal response to stressors. Consistent with this, in rats that are morphine-dependent and presumably tolerant, acute stress produced a greater excitation of LC neurons and an enhanced behavioral response to a stressor [81]. Because many stress-related psychiatric disorders are characterized by symptoms of hyperarousal, conditions that decrease opioid function would render individuals more vulnerable to these disorders. This could occur as a result of opioid tolerance from chronic use or an innate low sensitivity to opioids because of polymorphisms in the MOR gene [99]. The lower sensitivity of females to MOR agonists [100–102] implicates this as a factor contributing to their increased vulnerability to stress-related psychiatric disorders [103,104].

Repeated stress creates a state of opioid dependence

Although acute stress-induced opioid release is adaptive in curbing the excitatory effects of CRH, its persistence with either repeated or chronic stress can produce enduring modifications in neural circuits that result in opioid tolerance and dependence. This may be an underlying basis for the link between stress and substance abuse. For example, mice and rats exposed to repeated social stress exhibit mild opiate withdrawal signs when administered the opiate antagonist, naloxone, even though they have never been administered opiates [105]. This phenomenon is apparent at a cellular level and can be attributed to an imbalance between endogenous opioids and CRH in favor of opioids [106]. In contrast to the characteristic acute stress-induced activation of LC neurons, repeated social stress inhibits LC neuronal activity [106]. This is due both to a loss of the CRH-elicited excitation as a result of CRH1 internalization and to increased opioid release and MOR signaling. Naloxone administration up to 10 days after the last social stress exposure produces a robust activation of LC neurons resembling that which occurs in opiate-dependent animals and this is associated with mild signs of physical opiate withdrawal. This effect likely generalizes to other stressors because LC neurons were also unexpectedly inhibited in an animal model of PTSD that involves exposure to three different severe stressors [107]. Thus, repeated stress switches the predominant regulation of the LC from CRH-mediated activation to opioid-mediated inhibition (Figure 1). Although this switch may protect against the negative consequences of LC hyperactivity, the bias toward opioid regulation may increase vulnerability to opioid abuse in an effort to avoid negative effects of mild opioid withdrawal. Consistent with this, subjects with PTSD have a higher use of analgesics, show tolerance to opiate analgesia, and have a high comorbidity of opiate addiction [108–110]. These neuronal mechanisms at the level of the LC and perhaps in other brain regions may underlie the significant co-morbidity between PTSD and opiate addiction. This is an example of how a system designed to oppose stress can itself result in stress-related pathology.

Conclusions

Stress is implicated in diverse psychiatric and medical disorders. Stress-related pathology is generally thought to arise from a dysfunction in stress mediators as a consequence of either repeated or chronic stress. This review introduced the concept that pathological consequences of stress can also result from a dysfunction of systems that are engaged during stress but are designed to restrain the stress response. Although this review focused on opposing opioid/CRH interactions at the level of the LC, similar interactions can occur at other sites where opioids and CRH converge. For example, the dorsal raphe nucleus is a point of convergence between CRH and enkephalin, and evidence points to CRH1-MOR interactions in the serotonergic dorsal raphe nucleus as being somewhat analogous to the interactions in the LC [111]. Moreover, there are other endogenous neuromediators that have actions opposite to those of CRH or that have been proposed as protecting against the effects of stress. Individual differences in endogenous mechanisms that oppose the stress response can potentially determine the degree of vulnerability/resilience to stress-related pathology. Similarly, sex differences or age differences in stress-opposing systems can account for sex differences or developmental differences in stress vulnerability, respectively. Future studies designed to identify and characterize endogenous systems that oppose stress would advance our understanding of stress-related disorders and guide the development of therapeutics to treat these diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the National Institute of Drug Abuse (DA09082), the National Institute of Mental Health (MH040008), and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA 58077 LSDRP).

Abbreviations

- CRH

corticotropin-releasing hormone

- LC

locus coeruleus

- MOR

μ-opioid receptor

- NE

norepinephrine

- PTSD

post-traumatic stress disorder

The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found at: http://f1000.com/prime/reports/b/7/58

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no disclosures.

References

- 1.Chrousos GP. Stress, chronic inflammation, and emotional and physical well-being: concurrent effects and chronic sequelae. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106(Suppl 5):275–91. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.110163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chrousos GP, Gold PW. The concepts of stress and stress system disorders. Overview of physical and behavioral homeostasis. JAMA. 1992;267:1244–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03480090092034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Kloet E Ron, Joëls M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:463–75. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goeders NE. The impact of stress on addiction. Eur neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13:435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McEwen BS. Stress, adaptation, and disease. Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;840:33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larauche M, Mulak A, Taché Y. Stress and visceral pain: from animal models to clinical therapies. Exp neurol. 2012;233:49–67. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chrousos GP. The role of stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome: neuro-endocrine and target tissue-related causes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(Suppl 2):S50–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McEwen BS, Stellar E. Stress and the individual. Mechanisms leading to disease. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2093–101. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1993.00410180039004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keller-Wood ME, Dallman MF. Corticosteroid inhibition of ACTH secretion. Endocr Rev. 1984;5:1–24. doi: 10.1210/edrv-5-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowers ME, Choi DC, Ressler KJ. Neuropeptide regulation of fear and anxiety: Implications of cholecystokinin, endogenous opioids, and neuropeptide Y. Physiol Behav. 2012;107:699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crowe MS, Nass SR, Gabella KM, Kinsey SG. The endocannabinoid system modulates stress, emotionality, and inflammation. Brain Behav Immun 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunduz-Cinar O, Hill MN, McEwen BS, Holmes A. Amygdala FAAH and anandamide: mediating protection and recovery from stress. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2013;34:637–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heilig M, Thorsell A. Brain neuropeptide Y (NPY) in stress and alcohol dependence. Rev Neurosci. 2002;13:85–94. doi: 10.1515/REVNEURO.2002.13.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillard CJ. Stress regulates endocannabinoid-CB1 receptor signaling. Semin Immunol. 2014;26:380–8. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kozicz T. On the role of urocortin 1 in the non-preganglionic Edinger-Westphal nucleus in stress adaptation. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2007;153:235–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reul Johannes MHM, Holsboer F. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors 1 and 2 in anxiety and depression. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2:23–33. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4892(01)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vale W, Spiess J, Rivier C, Rivier J. Characterization of a 41-residue ovine hypothalamic peptide that stimulates secretion of corticotropin and beta-endorphin. Science. 1981;213:1394–7. doi: 10.1126/science.6267699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bale TL, Vale WW. CRF and CRF receptors: role in stress responsivity and other behaviors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:525–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB. Physiology and pharmacology of corticotropin-releasing factor. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:425–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakanaka M, Shibasaki T, Lederis K. Corticotropin releasing factor-like immunoreactivity in the rat brain as revealed by a modified cobalt-glucose oxidase-diaminobenzidine method. J Comp Neurol. 1987;260:256–98. doi: 10.1002/cne.902600209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE, Rivier J, Vale WW. Organization of ovine corticotropin-releasing factor immunoreactive cells and fibers in the rat brain: an immunohistochemical study. Neuroendocrinology. 1983;36:165–86. doi: 10.1159/000123454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Britton DR, Koob GF, Rivier J, Vale W. Intraventricular corticotropin-releasing factor enhances behavioral effects of novelty. Life Sci. 1982;31:363–7. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90416-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown MR, Fisher LA. Corticotropin-releasing factor: effects on the autonomic nervous system and visceral systems. Fed Proc. 1985;44:243–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown MR, Fisher LA, Spiess J, Rivier C, Rivier J, Vale W. Corticotropin-releasing factor: actions on the sympathetic nervous system and metabolism. Endocrinology. 1982;111:928–31. doi: 10.1210/endo-111-3-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taché Y, Goto Y, Gunion MW, Vale W, River J, Brown M. Inhibition of gastric acid secretion in rats by intracerebral injection of corticotropin-releasing factor. Science. 1983;222:935–7. doi: 10.1126/science.6415815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taché Y, Gunion M. Corticotropin-releasing factor: central action to influence gastric secretion. Fed Proc. 1985;44:255–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cole BJ, Koob GF. Propranolol antagonizes the enhanced conditioned fear produced by corticotropin releasing factor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;247:902–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snyder K, Wang W, Han R, McFadden K, Valentino RJ. Corticotropin-releasing factor in the norepinephrine nucleus, locus coeruleus, facilitates behavioral flexibility. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:520–30. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heinrichs SC, Menzaghi F, Merlo Pich E, Britton KT, Koob GF. The role of CRF in behavioral aspects of stress. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1995;771:92–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koob GF, Heinrichs SC. A role for corticotropin releasing factor and urocortin in behavioral responses to stressors. Brain Res. 1999;848:141–52. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sutton RE, Koob GF, Le Moal M, Rivier J, Vale W. Corticotropin releasing factor produces behavioural activation in rats. Nature. 1982;297:331–3. doi: 10.1038/297331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swerdlow NR, Geyer MA, Vale WW, Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor potentiates acoustic startle in rats: blockade by chlordiazepoxide. Psychopharmacology. 1986;88:147–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00652231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Contarino A, Dellu F, Koob GF, Smith GW, Lee KF, Vale W, Gold LH. Reduced anxiety-like and cognitive performance in mice lacking the corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1. Brain Res. 1999;835:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)01158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenz HJ, Raedler A, Greten H, Vale WW, Rivier JE. Stress-induced gastrointestinal secretory and motor responses in rats are mediated by endogenous corticotropin-releasing factor. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:1510–7. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawahara H, Kawahara Y, Westerink BH. The role of afferents to the locus coeruleus in the handling stress-induced increase in the release of noradrenaline in the medial prefrontal cortex: a dual-probe microdialysis study in the rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;387:279–86. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(99)00793-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://f1000.com/prime/723770656

- 36.Heinrichs SC, Pich EM, Miczek KA, Britton KT, Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor antagonist reduces emotionality in socially defeated rats via direct neurotropic action. Brain Res. 1992;581:190–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90708-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korte SM, Korte-Bouws GA, Bohus B, Koob GF. Effect of corticotropin-releasing factor antagonist on behavioral and neuroendocrine responses during exposure to defensive burying paradigm in rats. Physiol Behav. 1994;56:115–20. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90268-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smagin GN, Harris RB, Ryan DH. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor antagonist infused into the locus coeruleus attenuates immobilization stress-induced defensive withdrawal in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1996;220:167–70. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(96)13254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tazi A, Dantzer R, Le Moal M, Rivier J, Vale W, Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor antagonist blocks stress-induced fighting in rats. Regul Pept. 1987;18:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(87)90048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martínez V, Rivier J, Wang L, Taché Y. Central injection of a new corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) antagonist, astressin, blocks CRF- and stress-related alterations of gastric and colonic motor function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:754–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buéno L, Gué M. Evidence for the involvement of corticotropin-releasing factor in the gastrointestinal disturbances induced by acoustic and cold stress in mice. Brain Res. 1988;441:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91376-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gutman DA, Owens MJ, Skelton KH, Thrivikraman KV, Nemeroff CB. The corticotropin-releasing factor1 receptor antagonist R121919 attenuates the behavioral and endocrine responses to stress. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:874–80. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.042788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://f1000.com/prime/719110569

- 43.Keck ME, Holsboer F, Müller MB. Mouse mutants for the study of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor function: development of novel treatment strategies for mood disorders. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1018:445–57. doi: 10.1196/annals.1296.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Müller MB, Uhr M, Holsboer F, Keck ME. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical system and mood disorders: highlights from mutant mice. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;79:1–12. doi: 10.1159/000076041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bremner JD, Licinio J, Darnell A, Krystal JH, Owens MJ, Southwick SM, Nemeroff CB, Charney DS. Elevated CSF corticotropin-releasing factor concentrations in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:624–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.5.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gold PW, Chrousos GP. Organization of the stress system and its dysregulation in melancholic and atypical depression: high vs low CRH/NE states. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:254–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://f1000.com/prime/720223486

- 47.Taché Y, Mönnikes H, Bonaz B, Rivier J. Role of CRF in stress-related alterations of gastric and colonic motor function. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1993;697:233–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb49936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldstein A, Tachibana S, Lowney LI, Hunkapiller M, Hood L. Dynorphin-(1-13), an extraordinarily potent opioid peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:6666–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hughes J, Smith TW, Kosterlitz HW, Fothergill LA, Morgan BA, Morris HR. Identification of two related pentapeptides from the brain with potent opiate agonist activity. Nature. 1975;258:577–80. doi: 10.1038/258577a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ling N, Burgus R, Guillemin R. Isolation, primary structure, and synthesis of alpha-endorphin and gamma-endorphin, two peptides of hypothalamic-hypophysial origin with morphinomimetic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3942–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bradbury AF, Smyth DG, Snell CR. Biosynthetic origin and receptor conformation of methionine enkephalin. Nature. 1976;260:165–6. doi: 10.1038/260165a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meunier JC, Mollereau C, Toll L, Suaudeau C, Moisand C, Alvinerie P, Butour JL, Guillemot JC, Ferrara P, Monsarrat B. Isolation and structure of the endogenous agonist of opioid receptor-like ORL1 receptor. Nature. 1995;377:532–5. doi: 10.1038/377532a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pert CB, Snyder SH. Opiate receptor: demonstration in nervous tissue. Science. 1973;179:1011–4. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4077.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Comb M, Seeburg PH, Adelman J, Eiden L, Herbert E. Primary structure of the human Met- and Leu-enkephalin precursor and its mRNA. Nature. 1982;295:663–6. doi: 10.1038/295663a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kakidani H, Furutani Y, Takahashi H, Noda M, Morimoto Y, Hirose T, Asai M, Inayama S, Nakanishi S, Numa S. Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNA for porcine beta-neo-endorphin/dynorphin precursor. Nature. 1982;298:245–9. doi: 10.1038/298245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakanishi S, Inoue A, Kita T, Nakamura M, Chang AC, Cohen SN, Numa S. Nucleotide sequence of cloned cDNA for bovine corticotropin-beta-lipotropin precursor. Nature. 1979;278:423–7. doi: 10.1038/278423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ol'shanskiĭ VM, Orlov AA, Protasov VR. Assessment of the potentialities of the electrocommunication system of fishes. Izv Akad Nauk SSSR Biol. 1978;1:110–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nothacker HP, Reinscheid RK, Mansour A, Henningsen RA, Ardati A, Monsma FJ, Watson SJ, Civelli O. Primary structure and tissue distribution of the orphanin FQ precursor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8677–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pan YX, Xu J, Pasternak GW. Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding a mouse brain orphanin FQ/nociceptin precursor. Biochwm J. 1996;315:11–3. doi: 10.1042/bj3150011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mogil JS, Pasternak GW. The molecular and behavioral pharmacology of the orphanin FQ/nociceptin peptide and receptor family. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:381–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pasternak GW. Multiple opiate receptors: déjà vu all over again. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(Suppl 1):312–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zubieta JK, Smith YR, Bueller JA, Xu Y, Kilbourn MR, Jewett DM, Meyer CR, Koeppe RA, Stohler CS. Regional mu opioid receptor regulation of sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Science. 2001;293:311–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1060952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ribeiro SC, Kennedy SE, Smith YR, Stohler CS, Zubieta J. Interface of physical and emotional stress regulation through the endogenous opioid system and mu-opioid receptors. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:1264–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://f1000.com/prime/1047297

- 64.Akil H, Watson SJ, Young E, Lewis ME, Khachaturian H, Walker JM. Endogenous opioids: biology and function. Amm Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:223–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.07.030184.001255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sora I, Takahashi N, Funada M, Ujike H, Revay RS, Donovan DM, Miner LL, Uhl GR. Opiate receptor knockout mice define mu receptor roles in endogenous nociceptive responses and morphine-induced analgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1544–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Drolet G, Dumont EC, Gosselin I, Kinkead R, Laforest S, Trottier JF. Role of endogenous opioid system in the regulation of the stress response. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2001;25:729–41. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(01)00161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chavkin C. Dynorphin--still an extraordinarily potent opioid peptide. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;83:729–36. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.083337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://f1000.com/prime/725016210

- 68.Girardot MN, Holloway FA. Intermittent cold water stress-analgesia in rats: cross-tolerance to morphine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1984;20:631–3. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(84)90315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lewis JW, Cannon JT, Liebeskind JC. Opioid and nonopioid mechanisms of stress analgesia. Science. 1980;208:623–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7367889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miczek KA, Thompson ML, Shuster L. Opioid-like analgesia in defeated mice. Science. 1982;215:1520–2. doi: 10.1126/science.7199758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rodgers RJ, Randall JI. Social conflict analgesia: studies on naloxone antagonism and morphine cross-tolerance in male DBA/2 mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1985;23:883–7. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pitman RK, van der Kolk BA, Orr SP, Greenberg MS. Naloxone-reversible analgesic response to combat-related stimuli in posttraumatic stress disorder. A pilot study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:541–4. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180041007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van der Kolk BA, Greenberg MS, Orr SP, Pitman RK. Endogenous opioids, stress induced analgesia, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1989;25:417–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ceccatelli S, Orazzo C. Effect of different types of stressors on peptide messenger ribonucleic acids in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Acta endocrinol (Copenh) 1993;128:485–92. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1280485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dumont EC, Kinkead R, Trottier JF, Gosselin I, Drolet G. Effect of chronic psychogenic stress exposure on enkephalin neuronal activity and expression in the rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2200–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://f1000.com/prime/719062473

- 76.Mansi JA, Laforest S, Drolet G. Effect of stress exposure on the activation pattern of enkephalin-containing perikarya in the rat ventral medulla. J Neurochem. 2000;74:2568–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://f1000.com/prime/719062722

- 77.Lightman SL, Young WS. Changes in hypothalamic preproenkephalin A mRNA following stress and opiate withdrawal. Nature. 1987;328:643–5. doi: 10.1038/328643a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rossier J, French ED, Rivier C, Ling N, Guillemin R, Bloom FE. Foot-shock induced stress increases beta-endorphin levels in blood but not brain. Nature. 1977;270:618–20. doi: 10.1038/270618a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sakanaka M, Magari S, Shibasaki T, Inoue N. Co-localization of corticotropin-releasing factor- and enkephalin-like immunoreactivities in nerve cells of the rat hypothalamus and adjacent areas. Brain Res. 1989;487:357–62. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90840-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tjoumakaris SI, Rudoy C, Peoples J, Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele E J. Cellular interactions between axon terminals containing endogenous opioid peptides or corticotropin-releasing factor in the rat locus coeruleus and surrounding dorsal pontine tegmentum. J Comp Neurol. 2003;466:445–56. doi: 10.1002/cne.10893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xu G, van Bockstaele E, Reyes B, Bethea T, Valentino RJ. Chronic morphine sensitizes the brain norepinephrine system to corticotropin-releasing factor and stress. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8193–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1657-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Valentino RJ, van Bockstaele E. Opposing regulation of the locus coeruleus by corticotropin-releasing factor and opioids. Potential for reciprocal interactions between stress and opioid sensitivity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:331–42. doi: 10.1007/s002130000673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lorusso D, Misciagna G, Mangini V, Messa C, Cavallini A, Caruso ML, Giorgio P, Guerra V. Duodenogastric reflux of bile acids, gastrin and parietal cells, and gastric acid secretion before and 6 months after cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 1990;159:575–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(06)80069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Swanson LW. The locus coeruleus: a cytoarchitectonic, Golgi and immunohistochemical study in the albino rat. Brain Res. 1976;110:39–56. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Swanson LW, Hartman BK. The central adrenergic system. An immunofluorescence study of the location of cell bodies and their efferent connections in the rat utilizing dopamine-beta-hydroxylase as a marker. J Comp Neurol. 1975;163:467–505. doi: 10.1002/cne.901630406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Aston-Jones G, Shipley MT, Grzanna R. The locus coeruleus, A5 and A7 noradrenergic cell groups in The Rat Brain. In: Paxinos G, editor. Academic Press; 1995. pp. 183–213. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats exhibit pronounced responses to non-noxious environmental stimuli. J Neurosci. 1981;1:887–900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00887.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Activity of norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats anticipates fluctuations in the sleep-waking cycle. The J Neurosci. 1981;1:876–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00876.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Foote SL, Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Impulse activity of locus coeruleus neurons in awake rats and monkeys is a function of sensory stimulation and arousal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:3033–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:403–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rajkowski J, Kubiak P, Aston-Jones G. Locus coeruleus activity in monkey: phasic and tonic changes are associated with altered vigilance. Brain Res Bull. 1994;35:607–16. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Valentino RJ, Foote SL. Corticotropin-releasing factor disrupts sensory responses of brain noradrenergic neurons. Neuroendocrinology. 1987;45:28–36. doi: 10.1159/000124700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Valentino RJ, Foote SL. Corticotropin-releasing hormone increases tonic but not sensory-evoked activity of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons in unanesthetized rats. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1016–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-03-01016.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Valentino RJ, Wehby RG. Morphine effects on locus ceruleus neurons are dependent on the state of arousal and availability of external stimuli: studies in anesthetized and unanesthetized rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;244:1178–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Curtis AL, Bello NT, Valentino RJ. Evidence for functional release of endogenous opioids in the locus ceruleus during stress termination. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Curtis AL, Drolet G, Valentino RJ. Hemodynamic stress activates locus coeruleus neurons of unanesthetized rats. Brain Res Bull. 1993;31:737–44. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90150-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Curtis AL, Leiser SC, Snyder K, Valentino RJ. Predator stress engages corticotropin-releasing factor and opioid systems to alter the operating mode of locus coeruleus norepinephrine neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1737–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Valentino RJ, Wehby RG. Corticotropin-releasing factor: evidence for a neurotransmitter role in the locus ceruleus during hemodynamic stress. Neuroendocrinology. 1988;48:674–7. doi: 10.1159/000125081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mague SD, Blendy JA. OPRM1 SNP (A118G): involvement in disease development, treatment response, and animal models. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:172–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://f1000.com/prime/721341717

- 100.Kepler KL, Standifer KM, Paul D, Kest B, Pasternak GW, Bodnar RJ. Gender effects and central opioid analgesia. Pain. 1991;45:87–94. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90168-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ji Y, Murphy AZ, Traub RJ. Sex differences in morphine-induced analgesia of visceral pain are supraspinally and peripherally mediated. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R307–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00824.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wang X, Traub RJ, Murphy AZ. Persistent pain model reveals sex difference in morphine potency. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R300–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00022.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Breslau N. Gender differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Gend Specif Med. 2002;5:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Swartz M, Blazer DG. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey. II: Cohort effects. J Affect Disord. 1994;30:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Miczek KA, Thompson ML, Shuster L. Analgesia following defeat in an aggressive encounter: development of tolerance and changes in opioid receptors. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1986;467:14–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb14615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chaijale NN, Curtis AL, Wood SK, Zhang X, Bhatnagar S, Reyes BA, Van Bockstaele Elisabeth J, Valentino RJ. Social stress engages opioid regulation of locus coeruleus norepinephrine neurons and induces a state of cellular and physical opiate dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1833–43. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.George SA, Knox D, Curtis AL, Aldridge JW, Valentino RJ, Liberzon I. Altered locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function following single prolonged stress. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;37:901–9. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schwartz AC, Bradley R, Penza KM, Sexton M, Jay D, Haggard PJ, Garlow SJ, Ressler KJ. Pain medication use among patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:136–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://f1000.com/prime/720827727

- 109.Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1184–90. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://f1000.com/prime/720689732

- 110.Fareed A, Eilender P, Haber M, Bremner J, Whitfield N, Drexler K. Comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and opiate addiction: a literature review. J Addict Dis. 2013;32:168–79. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2013.795467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://f1000.com/prime/725433180

- 111.Staub DR, Lunden JW, Cathel AM, Dolben EL, Kirby LG. Morphine history sensitizes postsynaptic GABA receptors on dorsal raphe serotonin neurons in a stress-induced relapse model in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:859–70. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; http://f1000.com/prime/722348413