Abstract

The health impact of the global African dust event (ADE) phenomenon in the Caribbean has been vaguely investigated. Heavy metals in ADE and Non-ADE extracts were evaluated for the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant capacity by cells using, deferoxamine mesylate (DF) and N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC). Results show that ADE particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) induces ROS and stimulates oxidative stress. Pre-treatment with DF reduces ROS in ADE and Non-ADE extracts and in lung cells demonstrating that heavy metals are of utmost importance. Glutathione-S-transferase and Heme Oxygenase 1 mRNA levels are induced with ADE PM and reduced by DF and NAC. ADE extracts induced Nrf2 activity and IL-8 mRNA levels significantly more than Non-ADE. NF-κB activity was not detected in any sample. Trace elements and organic constituents in ADE PM2.5 enrich the local environment load, inducing ROS formation and activating antioxidant-signaling pathways increasing pro-inflammatory mediator expressions in lung cells.

Keywords: African dust, metals, ROS, oxidative stress, Nrf2, particulate matter

1. Introduction

Mineral dust has been removed from the West Africa coast and transported into the Caribbean Basin for hundreds of thousands of years with significant changes in the past 40 years (Garrison et al., 2010; Trapp et al., 2010). Satellite Images show that the island of Puerto Rico (PR) is situated within the path of African dust storms. Approximately 8 million tons of African dust was estimated as reaching the Puerto Rican coast in July of 2000 (Colarco et al., 2003). The dust concentration at sea level was over 70 μg/m3 (Reid et al., 2003). This massive airborne dust concentration is comparable to high levels of contamination reported in big cities around the world, like China (75 μg/m3) (Cao et al., 2012) and Monterrey, Mexico (85.9 μg/m3) (Geo-Mexico, 2014). The continuous input of African dust into the Caribbean is a major factor of air quality in the region. In March of 2004 a strong dust storm was reported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Terra satellite leaving the west coast of Africa and headed towards the Caribbean (Jiménez et al., 2009). By March 16, 2004 the Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS) satellite reported the highest aerosol index in its scale, 4.5, over West Africa. By this date the aerosol index in PR was 2–2.5. The year 2004 was distinguished by the high frequency of natural phenomena over PR of which 89 % was attributed to African dust events (ADE) (Ortiz-Martínez et al., 2010; Puerto Rico Environmental Quality Board, 2005). As the dust is transported into the Caribbean, it deposits particulate matter (PM) that has been influenced by surface and photochemical processes and is mixed with other air masses that contain many types of aerosols including biomass burning products and anthropogenic components (Trapp et al., 2010).

PM also known as particle pollution contains: acids, organic chemicals, metals, and soil or dust particles. Three different types of ambient particles are defined by size: ultrafine (<0.10 μm), fine (0.10–2.5 μm) and coarse (2.5–10 μm). This study focuses on fine PM. Fine particulate matter or PM2.5 arises from fossil fuel combustion, road traffic, and other transports, agriculture, and manufacturing. This PM penetrates in the respiratory system deep into the alveoli where it delivers its constituents to biological fluids and blood. Airborne PM2.5 concentration has been found to increase substantially in PR with ADE (Gioda et al., 2007; Jiménez et al., 2009; Puerto Rico Environmental Quality Board, 2005, 2004). The United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have established PM2.5 standards (Air and Radiation, 2008; Esworthy, 2013; Particulate matter standards, 2014) in order to control global PM emissions, reduce global warming and protect human health. Although Natural phenomena such as dust storms cannot be controlled and hence regulated, however, weather alerts can play an important and critical role in protecting population health. Oxidative damage and inflammatory injury can be considered as common mechanisms by which PM-induce health adverse effect (Aust et al., 2002; Ekstrand et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013).

Metals associated with PM have the capacity to generate oxidative damage to tissues (lung) by inducing the formation of free radicals like reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Li et al., 2008). ROS can serve as both intra and inter cellular messenger, and participate in the activation of cell signaling cascades and gene expression (Forman and Torres, 2002; Hancock et al., 2001). Some of these emissaries include superoxide and hydrogen peroxide.

The antioxidant defense system includes enzymes and a number of non-enzymatic small molecules such as glutathione, ascorbic acid and α-tocopherol. The expression of many detoxification and antioxidant defense genes have been reported to be regulated by the nuclear erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) (Cho et al., 2006; Li et al., 2008; Valentina et al., 2010). However, Nrf2 has also been shown to regulate other genes that participate in: cellular redox homeostasis, cell growth, apoptosis, inflammatory response, and the ubiquitin-mediated degradation pathway (Zhang, 2006). The Nrf2 is regulated in human macrophages and bronchial epithelial cells during oxidative episodes, which are induced by PM (Li et al., 2004; Valentina et al., 2010).

Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB) is another transcription factor known to be induced by heavy metals and ROS, is normally sequestered in the cytoplasm as an inactive multiunit complex bound to an inhibitory protein (I-κB) (Tripathi and Aggarwal, 2006; Valko et al., 2005). PM can activate this complex by causing phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of I-κB and translocation of the active dimer into the nucleus, where it binds to the promoter region of genes including many cytokines that contain the NF-κB motif (Silbajoris et al., 2011). Significant releases of IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α were reported using human airway epithelial cells exposed to PM (Carter et al., 1997). IL-6 plays a key role in inflammation, is one of the most important mediators of fever and stimulates energy mobilization in muscle and fatty tissues (Wruck et al., 2011). IL-8 is a chemo-attractant that recruits neutrophils which stimulate further inflammatory responses (Ishii et al., 2005). IL-8 is known to be sensitive to alterations in redox potential and antioxidants (Zhang et al., 2005).

Asthma is a pulmonary illness of airway inflammation. Its prevalence rates in Puerto Ricans are one of the highest in the world, compared to other populations including Hispanics (Akinbami et al., 2011; Ortiz-Martínez et al., 2010; Pérez-Perdomo et al., 2003). Susceptible inhabitants in PR report exacerbation of their asthma condition during ADE. Data obtained from the Puerto Rico’s Health Insurance Administration reported an increase in asthma cases for children ≤5 yrs of age during the dust season considered in the present study. Many metals (Al, Cu, Fe, Pb and V) have been reported to increase in association to the advent of African dust storms (Gioda et al., 2007; Jiménez et al., 2009; Rodríguez-Cotto et al., 2013). In 2004 17% of PR PM2.5 was composed of metals (Puerto Rico Environmental Quality Board, 2005). The current study investigates the pro-oxidative and pro-inflammatory effects of ambient PM2.5 and its constituent metals during dust storms in PR, using human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) in order to obtain data that support a relationship between the natural phenomenon and the exacerbation of respiratory diseases. The hypothesis posed in this work is that metals in ADE PM2.5 generate ROS and stimulate antioxidant defenses and inflammatory responses through the activation of Nrf2 and NF-κB signaling pathways in human lung cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Samples preparation

PM2.5 air filter samples for March 2004 were provided by the PR Environmental Quality Board (PR-EQB) from station EQB 22 located in the municipality of Fajardo at the north eastern coast of PR (18°:23:00/65°:37:10). This station is not affected by industrial emissions but only by natural events (Puerto Rico Environmental Quality Board, 2003). The PR-EQB has designated station EQB 22 as a remote site to measure African dust minimizing the contribution of other local sources of particulate matter. The samples were classified according to the corresponding collection day, as ADE and Non-ADE utilizing satellite images in conjunction with ground field data of PM2.5 weights provided by PR-EQB (Rodríguez-Cotto et al., 2013). Two organic extracts were prepared using a Soxhlet extraction apparatus for 48 hr (Molinelli et al., 2006). The organic extracts were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma, Cat # D2650) to a concentration of 100 mg/ml. Extracts were stored at −20°C. These samples were previously analyzed for metal composition (Al, Fe, Cd, Cu, Pb and V), cytotoxicity and interleukins (IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, TNF-α and GM-CSF) concentration (Rodríguez-Cotto et al., 2013).

2.2 Oxidative Capacity of Extracts

The ROS formation by extracts was determined employing the dithiothreitol (DTT) assay (Balakrishna et al., 2009). The reduction of DTT was measured as it reacted with 5, 5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) and converted to 5-mercapto-2-nitrobenzoic, which in turns absorbs at 412 nm. The organic extracts were used at 25, 50, 75 and 100 μg/ml in 250 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.9). A 16 mM solution of DTT (7 μl) and 700 μl of the test sample, including a blank (250 mM Tris-HCl buffer only), were prepared and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. After the incubation, 14 μl of DTNB 16 mM were added and samples read in 96-well plate in triplicates at 412 nm using an Ultramark microplate reader (Bio-Rad).

2.3 Cell Culture and Exposure

Human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC®CRL-9609™). The cells were cultured according to ATCC protocols, maintained in keratinocyte basal medium (KBM-2, Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA cat # CC3103) and supplemented with KGM-2 SingleQuots; Lonza, cat # CC4152). BEAS-2B at passages 44–59 were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Before treatments, cells were seeded at a density of 5×104 cells/well (96-well plate), 1×106 cells/well (6-well plate) and incubated for 24 hr. Cells were exposed to PM2.5 extracts at a concentration of 50 μg/ml for 1–14 hr depending on the assay. The extract concentration of 50 μg/ml was selected from a previous cytotoxicity assay (Rodríguez-Cotto et al., 2013). This concentration was not toxic to the cells. To determine the relative contribution of trace metals two additional set of cells (n=3 dish) were also used to treat BEAS-2B with organic extracts and deferoxamine mesylate (DF, Sigma, cat # D9533), a metal chelator, at a final concentration of 50 μM and or N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), an antioxidant, at 0.5 mM. Extracts with 50 μM DF were sonicated in a water bath for 30 min prior to cell exposure. DF (50 μM) and NAC (0.5 mM) were evaluated for cell viability and resulted non-toxic to BEAS-2B. DMSO was used as a vehicle at a final concentration of 0.1%. Appropriate controls: medium, DMSO and media exposed to DF and NAC were run simultaneously with each experiment. Blank filter extracts were also tested.

2.4 In vitro ROS Formation by Particulate Matter

ROS formation was determined using the non-fluorescent dye 2′7 dichlorofluorescein diacetate 5 μM (DCFH-DA, Molecular Probe, Eugene, OR) as recommended by the manufacturer. The cells were incubated with 200 μl of the dye at 37°C for 1 hr. The dye was removed and the cells washed 2X by using phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and then treated with the organic extracts. Other cell sets were treated with the organic extracts pre-incubated with 50 μM DF. A positive control was prepared using H2O2 100 μM. Upon ROS formation DCFH was oxidized to its fluorescent form, 2′7 dichlorofluorescein (DCF). The rate of ROS formation was monitored for 3 hr by reading fluorescence (485ex/530em) every 15 min in a Spectra Max M3 fluorescence microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

2.5 Oxidative Stress Assessment

Cells were grown on six well plates and exposed for 4 hr to PM extracts. The antioxidant capacity of cell lysates was measured using the antioxidant assay kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Aqueous and lipid soluble antioxidants are not separated in this protocol, thus the combined antioxidant activity of lysate constituents were determined. A ferryl myoglobin radical is formed from metmyoglobin and hydrogen peroxide. The ferryl myoglobin radical can oxidize 2,2′-azino-di-[3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonate] (ABTS) to generate a radical cation, ABTS·+ (green) which is measured at 405 nm. Antioxidants suppress this reaction by donating electrons inhibiting the formation of the colored ABTS radical. The concentration of antioxidants in the test sample is inversely proportional to the ABTS radical formation. Trolox [6-Hydroxy-2, 5, 7, 8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid], a water-soluble vitamin E analog, serves as a positive control inhibiting the formation of the radical cation in a dose dependent manner. A standard curve was prepared using Trolox. Measurements were performed on an Ultramark microplate reader (Bio-Rad).

2.6 Nrf2 and NF-κB Assessment

Cells were exposed to PM2.5 extracts (50 μg/ml) with and without NAC (0.5 mM) or DF (50 μM) to evaluate the activation of the transcription factors Nrf2 (1 hr exposure) and NF-κB (4 hr exposure). These time points were selected based on previous literature were Nrf2 was detected at 1 hr (Li et al., 2004) in this cell line and Nf-kB at 4 hr (Silbajoris et al., 2011). These studies required a lot of cells in order to collect enough protein for Nrf2 and NF-kB activation, which also required a lot of extract. Therefore, it was critical to select the proper time points, which were obtained from previous literature on similar experiments. Protein was extracted using the Nuclear Extract Kit from Active Motif according to the manufacturer guidelines. The nuclear fraction was obtained using a hypotonic solution and a detergent followed by centrifugation. Proteins were quantified employing the Bradford assay. The Nrf2 and NF-κB activity was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, Active Motif) as follows. The nuclear extracts containing the activated transcription factors were added to specific oligonucleotide with a consensus-binding site for Nrf2 or NF-κB. The primary antibody and the anti immunoglobulin G couple to horseradish peroxidase (IgG HRP) conjugate were added in sequence at intervals of 1hr. Finally the reaction mixture was exposed to a developer (5 min), a stop solution (5 min) and the absorbance read at 450 nm. Diesel exhaust particles (DEP) at 25 μg/ml were used as a positive control for Nrf2 in BEAS-2B (Li et al., 2004).

2.7 Time Course for Antioxidant and Pro-inflammatory Genes

Total RNA from extract (50 μg/ml) exposed cells with and without NAC (0.5 mM) and DF (50 μM) at different time points (1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12 and 14 hr) were obtained by TRIZOL extraction (Invitrogen). The mRNAs from genes activated via Nrf2: HMOX1 (Hs00157965_m1) and GSTP1 (Hs00168310_m1) as well as NF-κB activated genes: IL-6 (Hs00985639_m1) and IL-8 (Hs00174103_m1) were quantified by Quantitative fluorescent amplification from cDNA using the TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Step One Real Time PCR System from Applied Biosystem). The β actin (Hs99999903_m1) housekeeping gene was used to validate and normalize the target genes. Cytokines positive release controls were prepared using lipopolysacharide (LPS) 10 μg/ml and H2O2 100 μM used as positive control for HMOX1 and GSTP1.

2.8 Statistical Analyses

To analyze differences between individual groups the unpaired Student’s t Test was employed. The criterion for statistical significance was set at p≤0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad InStat 3 software. Analyses were based on 3 independent experiments per cell response.

3. Results and Discussion

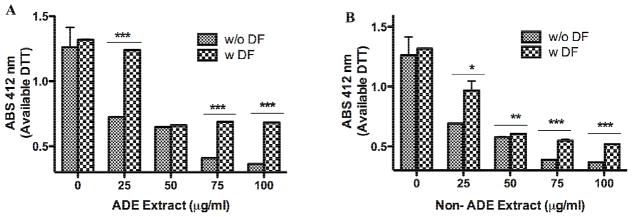

3.1 Oxidative Capacity of Extracts

The PM2.5 extracts concentration from both ADE and Non-ADE samples were directly correlated to oxidative capacity (OC) (Fig. 1A and 1B). ADE extract (25 μg/ml) pre-treated with DF reduces the OC back to its original level (Fig. 1A) indicating that heavy metals from dust storms are responsible for the observed effect. However, pre-incubation of DF in Non-ADE extract only reduced OC in half of the original value of the extract (Fig. 1B) which implies that beside metals there are other components that contribute to the oxidative potential at the site. ADE-DF treatments significantly reduced the OC at 75 and 100 μg/ml and Non-ADE at 50, 75 and 100 μg/ml. Both ADE and Non-ADE extracts pre-treated with DF at 50, 75 and 100 μg/ml did not reduce the total OC of the extract much further than that of 25 μg/ml. High concentrations (75–100 μg/ml) of both ADE and Non-ADE increased the OC of the extracts as much as 70%. The OC of ADE extract was mainly dependent on the PM2.5 metal constituents. Conversely, the Non-ADE OC was shared between metals and other organic constituents. PM2.5 African dust arrives to PR with organic pollutants, traces of metals (TMET) and microorganisms affecting the air quality and impacting human health in the region (Ortiz-Martínez et al., 2010; Rodríguez-Cotto et al., 2013). The samples used in this study were previously analyzed for metal composition and cytotoxicity (Rodríguez-Cotto et al., 2013). The ADE extract contained relative amounts of TMET and was ranked as follows: Cd < V <Pb< Al < Cu <Fe. The Non-ADE extract TMET ranked as follows: Cd< V <Pb< Cu < Al < Fe. The most abundant TMET in ADE extract were Cu, Pb and V and were higher than in Non-ADE. The ADE extract was more toxic to BEAS-2B than Non-ADE and this toxicity diminished with the use of the chelator agent (Rodríguez-Cotto et al., 2013). The reduction in the OC of extracts pre-treated with the metal chelator supports the working hypothesis that differences in metal composition and concentration are responsible for the extracts toxicity and oxidative potential. PM redox activity has been associated with metals and organic compounds, especially polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs) (Becker et al., 2005; Cho et al., 2005; Di Stefano et al., 2009; Gualtieri et al., 2009; Li et al., 2003; Ntziachristos et al., 2007). The data presented here indicates that the ADE and Non-ADE extract vary in its composition. Even though ADE extracts contain the background composition of metals and organic constituents of Non-ADE these storm events bring additional components. This alters the OC of the ADE extract masking the OC effects of NON-ADE by increasing the concentration of Non-ADE common components and adding new constituents by the storms. The general effect of ADE extract on OC seems to be greatly associated to heavy metals however, this methods only looks at absorbance measured as DTT and therefore, can not be interpreted as the total Oxidative Capacity of the extract.

Fig. 1. Extract Oxidative Capacity.

The consumption rate of dithiothreitol (DTT) is used to determine the oxidative potential. The extracts from African dust events (ADE) and non-African dust events (Non-ADE) were evaluated for oxidative capacity (OC) at increasing dose with and without deferoxamine (DF, 50 μM). The reducing agent was added followed by 5,5′-Dithiobis(2-nitro-benzoic acid) (DTNB), which produces a yellow color (absorbs at 412 nm) upon reacting with DTT. ABS stands for absorbance. Bars represent the mean available DTT ± SEM, ***p <0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 (n=3). This assay is an indirect measure of ROS in the extracts (Balakrishna et al., 2009).

3.2 In vitro ROS Formation by Particulate Matter

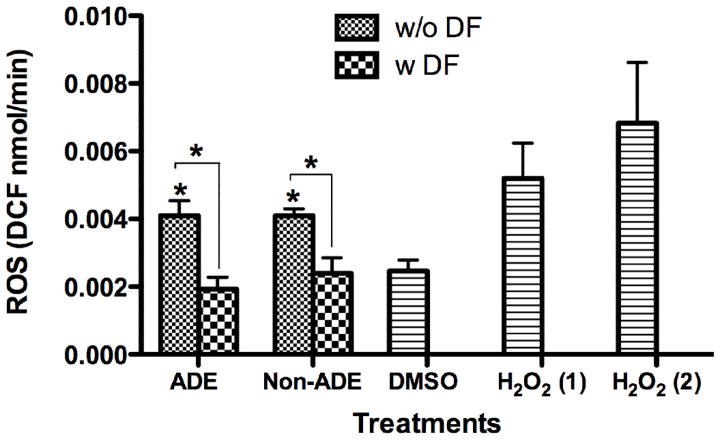

Cells exposed to extracts exhibit ROS formation which may be generated by free radicals present on particle surface or by the chemical interactions of specific PM constituents (Li et al., 2003; Squadrito et al., 2001). The formation of ROS by both, ADE and Non-ADE extracts in the exposed cells was very similar (Fig. 2) and decreased upon DF pre-incubation. The use of DF confirmed that trace elements play a significant role in ROS formation in vitro. Transition metal ions associated with PM can produce ROS or catalyze the formation of hydroxyl radical from hydrogen peroxide through Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions (Li et al., 2008). PACs, such as quinone and hydroquinones, can produce the superoxide ion that act as a catalyst for the Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions (Akhtar et al., 2010; Balakrishna et al., 2009). In vitro ROS can also be produced through PM-mediated activation of mitochondria or NADPH-oxidase enzymes in immune cells (Lee and Yang 2012; Schins and Hei 2007).

Fig. 2. Generation of Intracellular ROS (H2O2) in BEAS-2B.

Cells were pre-incubated for 1 hr with 5 μM 2′7 dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA). Extracts treatments (50 μg/ml from, ADE, and Non-ADE, PM2.5), DMSO (vehicle 0.1%) and deferoxamine (DF) 50 μM. H2O2, a positive control, were used at two concentrations: (1) at 100 and (2) at 250 μM. The rate of ROS formation was measured by fluorescence (485ex/530em). Each histogram bar represents the mean DCF nmol/min ± SEM, *p<0.05 (n=3).

3.3 Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Capacity of Cells

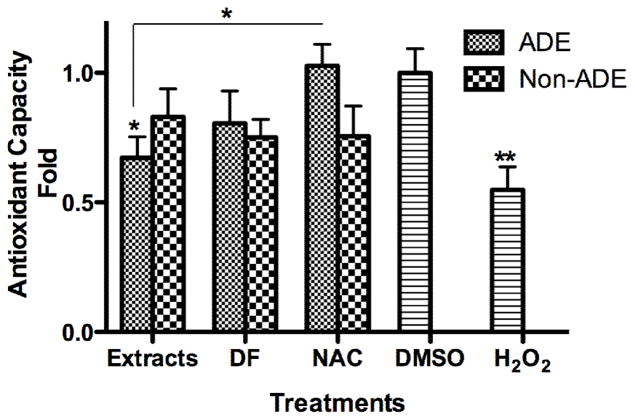

The formation of ROS and the cells ability to respond to it (the cell antioxidant capacity) could induce oxidative stress. BEAS-2B exposed to ADE extract exhibited a significant reduction in its total antioxidant capacity (TAC, Fig. 3). This TAC was completely overturned when cells were co-incubated with the ADE extract and the antioxidant NAC supporting our views. The TAC of cells exposed to ADE showed an increase (10 %) after extract pre-treatment with DF. This supports further our findings that other extract components in addition to heavy metals are responsible for decreasing the antioxidant capacity of the cells. NAC can act as a free radical scavenger via its sulfhydryl group and is able to restoreTAC reduced by metals and organic compounds. Although the Non-ADE extract generates ROS in vitro and its OC depend on metals and other organics (as discussed in the previous OC section), the TAC of exposed cells was not reduced by this extract. These findings support that there are differences in the composition and properties between the local PM with and without the presence of African dust. The role of oxidative stress mediating the biological responses of PM was explained using DEP as a model in a previous publication (Li et al., 2002; Xiao et al., 2003). The model implies that low levels of oxidative stress induce protective responses (through Nrf2 signaling) while; high levels yield inflammatory responses including apoptosis (Li et al., 2008; Li et al., 2003). Any flaw in the protective pathway promotes the susceptibility to particle-induced oxidant injury (e.g., the exacerbation of airway inflammation and asthma). Thus, due to inherent protective mechanisms, particle induced ROS does not necessarily lead to adverse biological response. Here we demonstrate that ADE extract generated oxidative stress in exposed cells and that both heavy metals and organic constituents of the extract play a significant role in ROS formation.

Fig. 3. The Antioxidant Capacity of BEAS-2B Exposed to Extracts.

Cells were treated with African dust events (ADE) and non-African dust events (Non-ADE) PM2.5 extracts (50 μg/ml) with or without deferoxamine (DF, 50 μM) or the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC, 0.5 mM) at 4 hr. DMSO at 0.1%, was used as vehicle and H2O2 (100 μM) was used as positive control. Values were normalized against DMSO. Bars represent mean antioxidant capacity ± SEM when compared to DMSO, **p<0.01, *p < 0.05 (n=3).

3.4 Nrf2 and NF-κB Assessment

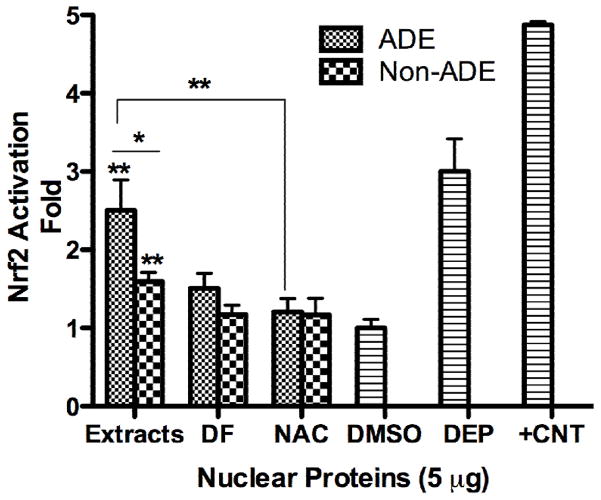

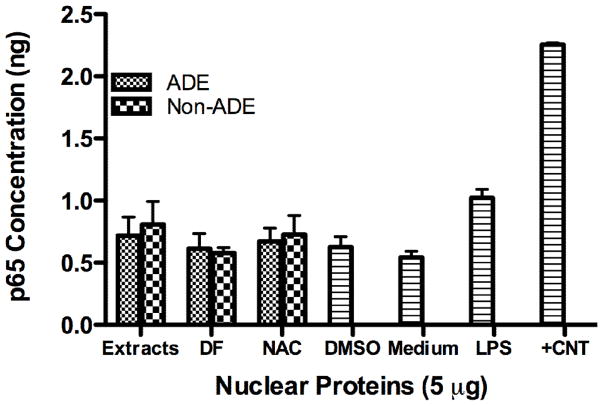

Nrf2 activation increased in cells treated with both ADE and Non-ADE organic extracts (Fig. 4) however, the magnitude of induction due to ADE was much greater than Non-ADE. Co-treatment with ADE extracts and NAC reduced this activation factor to its background level indicating the significance of ROS in Nrf2 activation. The use of DF resulted in a similar but not as marked reduction (since it was not statistically significant at the 95 % confidence level) as that produced by NAC. This is additional evidence that indicates the presence of other ADE components such as organics that are also responsible for the antioxidant response. Although Nrf2 activation is induced in Non-ADE treated cells, neither DF nor NAC reduces this response in a highly significant manner. This result suggests that Nrf2 maintains an antioxidant response basal level and may also be involved in the regulation of other functions such as detoxification or cellular redox homeostasis. Our results show that most of the Nrf2 activation in ADE and Non-ADE extracts is due to the presence of metals. Previous analysis of cells exposed to ADE and Non-ADE extracts revealed asignificant increase in pro-inflammatory mediators (IL-6 and IL-8) (Rodríguez-Cotto et al., 2013) however, no evidence was found for NF-kB activation by 4 hr (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Effect of PM2.5 Extracts on Nrf2 Activation.

Cells were exposed to treatments for 1 hr and the nuclear protein extracted and the ELISA technique performed. Cells were treated with African dust events (ADE) and non-African dust events (Non-ADE) PM2.5 extracts (50 μg/ml) with or without deferoxamine (DF, 50 μM) or the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC, 0.5 mM). DMSO at 0.1% was used as vehicle. Diesel exhaust particles (DEP, 25 μg/ml) and nuclear extracts from COS-7 Nrf2 transfected cells were used as positive controls (+CNT). The values were normalized with DMSO. Bars represent means ± SEM, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, n=3.

Fig. 5. Effect of PM2.5 Extracts on NF-κB Activation.

Cells were exposed to treatments for 4 hr, the nuclear protein extracted and the ELISA technique performed. Cells were treated with African dust events (ADE) and non-African dust events (Non-ADE) PM2.5 extracts (50 μg/ml) with or without deferoxamine (DF, 50 μM) or the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC, 0.5 mM). DMSO at 0.1% was used as vehicle. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 10 μg/ml) and nuclear extract from Jurkat cells stimulated with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol (TPA) and calcium ionophore were used as positive controls (+CNT), n=3. p65 is one of the subunits of NF-κB.

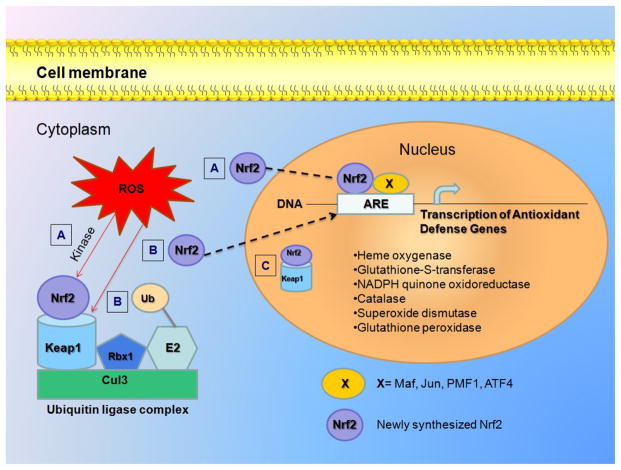

Nrf2 can be activated by several mechanisms. Induction of Nrf2 in human lung alveolar epithelial A549 cells by PM2.5 is achieved by activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway through the phosphorylation of the factor (Fig. 6 letter A) facilitating disassociation from Keap1 and nuclear translocation (Deng et al., 2013). A different mechanism (Fig. 6 letter B) is through redox changes that can inhibit the activity of Keap1-Cul3 ubiquitin ligase resulting in: (1) a decrease in Nrf2 ubiquitination, (2) enhance Nrf2 stability, (3) elevated Nrf2 levels by saturation of binding sites of Keap1, (4) translocation of free Nrf2 into the nucleus, (5) where Nrf2 can form dimers with others transcription factors of the Maf and the Jun families, polyamine modulated factor 1 (PMF1), or activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) and then bind to the antioxidant response element (ARE), (6) inducting the ARE-dependent gene transcription (Liby et al., 2005, MacLeod et al., 2009; Turpaev, 2013; Valentina et al., 2010; Zhang, 2006). Another mechanism has been shown for the activation of Nrf2 by heavy metals. It has been reported that heavy metals (As, Cr and Cd) facilitates direct Nrf2-Keap1 complex translocation into the nucleus (Fig. 6 letter C)(He et al, 2008). Since the inactivation of Nrf2 is reduced by the use of DF we suggest that this mechanism could predominate during PM exposure; however this needs to be verified and proved.

Fig. 6. Possible mechanisms for Nrf2 activation during PM exposure.

Nrf2 is mainly located in the cytoplasm through its interaction with the Kelch like ECH associated protein 1 (Keap1). Keap1 is linked with the scaffold protein Cul3, which constitutes the ubiquitin ligase E3 complex together with ubiquitin ligase Rbx1. Modification of Nrf2 by phosphorilation (A) or Keap1 by oxidation (B), changes the conformation and the structure of the multicomponent complex Nrf2–Keap1–Cul3–E2. The contact between Nrf2 and Keap1 is broken, inhibiting the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of Nrf2. The newly synthesized Nrf2 molecules escape the capture by Keap1, transfer to the nucleus, and activate the transcription of antioxidant protective genes. A third mechanism facilitates Nrf2-Keap1 complex translocation into the nucleus (C).

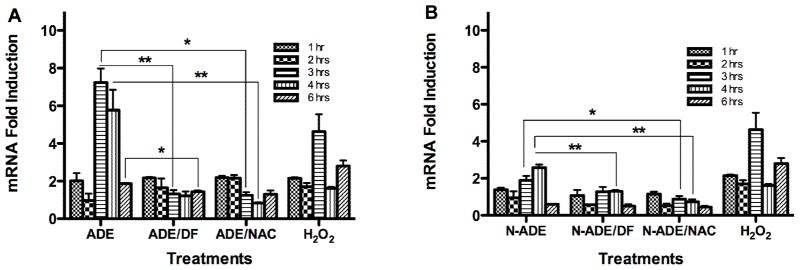

3.5 Time Course of Antioxidant and Pro-inflammatory Gene Expression

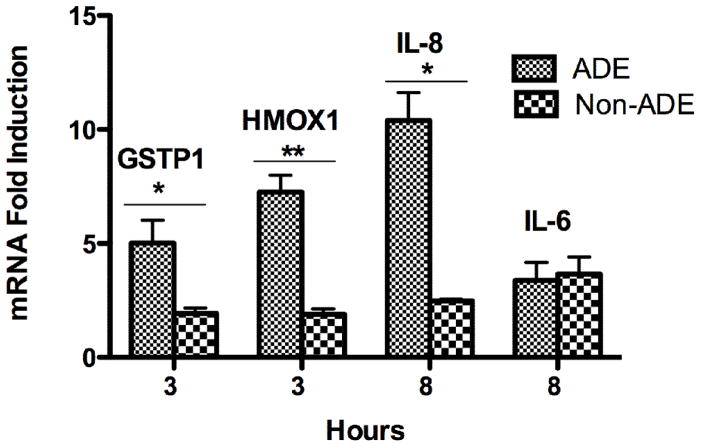

To verify signaling through Nrf2 the induction of HMOX1 (Fig. 7) and GSTP1 (Fig. 8) mRNAs were measured. Since an increase in IL-8 and IL-6 were observed in a previous study (Rodríguez-Cotto et al., 2013) the mRNAs for these cytokines were also measured (Fig. 9, and Fig. 10).

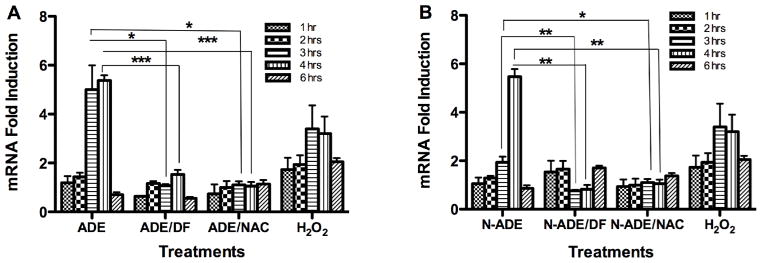

Fig. 7. Effect of PM2.5 Extracts on HMOX1 mRNA.

Quantitative fluorescent amplification for: A. African dust events (ADE) and B. non-African dust events (N-ADE) were performed using the TaqMan gene expression Assay. Extract treatments were performed at 50 μg/ml. H2O2 (100 μM) was used as positive control. DMSO (vehicle 0.1%), N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC, 0.5 mM), deferoxamine (DF, 50 μM) and a blank filter were also used as controls. All showed similar responses as cell media. Bars represent means ± SEM, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, n=3–4.

Fig. 8. Effect of PM2.5 Extracts on GSTP1 mRNA.

Quantitative fluorescent amplification for: A. African dust events (ADE) and B. non-African dust events (N-ADE) were performed using the TaqMan gene expression Assay. Extract treatments were performed at 50 μg/ml. H2O2 (100 μM) was used as positive control. DMSO (vehicle 0.1%), N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC, 0.5 mM), deferoxamine (DF, 50 μM) and a blank filter were also used as controls. All showed similar responses as cell media. Bars represent means ± SEM, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, n=3–4.

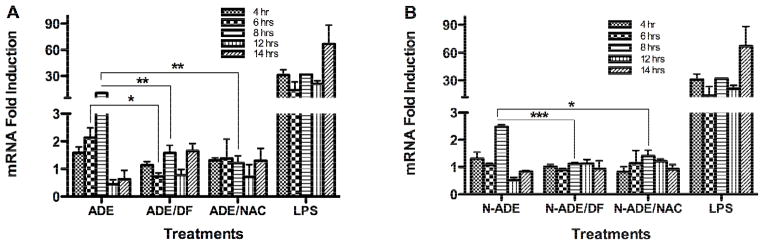

Fig. 9. Effect of PM2.5 Extracts on IL-8 mRNA.

Quantitative fluorescent amplification for: A. African dust events (ADE) and B. non-African dust events (N-ADE) were performed using the TaqMan gene expression Assay. Extract treatments were used at 50 μg/ml. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 10 μg/ml) was employed as a positive control. DMSO (vehicle 0.1%), N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC, 0.5 mM), deferoxamine (DF, 50 μM) and a blank filter were also used as controls. All showed similar responses as cell media. Bars represent means ± SEM, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, n=3–4.

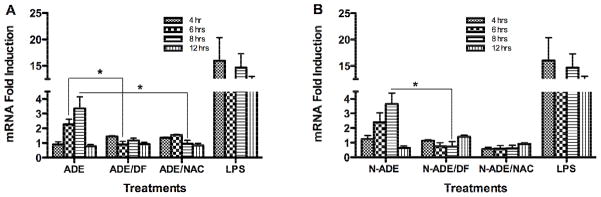

Fig. 10. Effect of PM2.5 Extracts on IL-6 mRNA.

Quantitative fluorescent amplification for: A. African dust events (ADE) and B. non-African dust events (N-ADE) were performed using the TaqMan gene expression Assay. Extract treatments were used at 50 μg/ml. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 10 μg/ml) was employed as positive controls. DMSO (vehicle 0.1%), N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC, 0.5 mM), deferoxamine (DF, 50 μM) and a blank filter were also used as controls. All showed similar responses as cell media. Bars represent means ± SEM, *p < 0.05, n=3–4.

3.5.1 HMOX1 and GSTP1

The synthesis of HMOX1 mRNA (codifying for HO-1 protein that forms part of the cells antioxidant defenses) preceded the inflammatory responses and began at 1 hr after cells exposure. BEAS-2B exposed to PM2.5 ADE extract exhibited mRNA of HMOX1 and GSTP1 which peaked at 3 and 4 hr after the treatment (Fig. 7A and Fig. 8A). At 3 hr the synthesis was reduced with either the chelator agent (DF) or the antioxidant NAC for both genes, indicating that metals and ROS are involved in this response. At 4 hr the synthesis of HMOX1 mRNA was still high and its expression was due to ROS, since it decreases with NAC treatment. GSTP1 synthesis was also high and decreased with NAC and DF. At 6 hr the effect of the response retreated to its background levels for both genes. Non-ADE extract also increased HMOX1mRNA (Fig. 7B) and GSTP1 (Fig. 8B) at 3 and 4 hr after treatment. At 3 hr the induction was significantly reduced with NAC (HMOX) and at 4 hr with both DF and NAC (HMOX and GSTP1). The GSTP1induction at 3 hr decreased with DF and NAC. It is important to notice that ADE extract induces HMOX1 at 3 hr while Non-ADE peaks at 4 hr. This suggests that ADE contains constituents not found in Non-ADE that speed up the response of this gene. At 6 hr a reduction in the synthesis was also observed. These findings for both HMOX1 and GSTP1 support the hypothesis that ADE extracts contain constituents that accelerate the response of phase 2 genes while Non-ADE retards such response.

3.5.2 IL-8

The synthesis of IL-8 mRNA was detected at 4 hr and forms part of the inflammatory responses that may follow antioxidant defenses (Li et al., 2008; Li et al., 2004). We found that ADE extract exposure induced the synthesis of IL-8 mRNA at 6 hr (2 fold) and 8 hr (10 fold). The IL-8 mRNA concentration was reduced at both 6 and 8 hr in the presence of DF and NAC (Fig. 9A), again adding on to the list of results that evidence the importance of both metals and ROS generation due to PM extract exposure. Non-ADE extracts did not induce IL-8 as strongly as ADE extract did (Fig. 9B), indicating that ADE extract contain specific constituents that promotes pro-inflammatory responses through ROS mechanisms. These results correlate very well with the results obtained for protein released by lung cells (Rodríguez-Cotto et al., 2013).

3.5.3 IL-6

A time course experiment (4 to 12 hr) similar to that performed on the IL-8 was also done for IL-6 mRNA. ADE and Non-ADE extracts were found to significantly increase the IL-6 mRNA levels at 6 and 8 hr and peaked at 8 hr (Fig. 10). At 6 hr the fold induction was 2 and at 8 hr it was 3.4 at which the mRNA synthesis was reduced by the use of DF (Non-ADE) and NAC (ADE). Again this is consistent with the metals dependent response by the extracts and their capacity to contribute to the generation of ROS. It is interesting to point out that the IL-6 mRNA induction was similar for both extracts (Fig. 11). These results correlate with the protein data, which were measured at 24 hr (Rodríguez-Cotto et al., 2013). The magnitude of ADE mRNA induction (HMOX1, GSTP1 and IL-8) is greater than Non-ADE (Fig. 11). The use of DF or NAC significantly reduced GSTP1, HMOX1, IL-6, and IL-8 mRNA expression indicating the importance and relevance of trace element on these biomarkers. Upon evaluating the expression of all these biomarkers the gene time sequence of induction was proposed as follows: HMOX1 and GSTP1 within 3 hr while IL-6 and IL-8 followed at 8 hr (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. Summary of mRNAs Induction by African Dust Events and Non-African Dust Events Extracts.

The mRNAs induction were selected from figures 7–10 and plotted against their peak hour to illustrate the greatest effect of African dust events (ADE) over non-African dust events (Non-ADE). Bars represent means ± **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, n=3–4.

The chronology of gene expression events indicates that ADE extract induces the generation of ROS in vitro which activates Nrf2 factor within the first hr followed by HMOX and GSTP1at 3hrs. HO-1 has been identified as a biomarker for oxidative stress in BEAS-2B (Li et al., 2004) and GST has a principal role in the management of ROS. The used of DF and NAC revealed that metals are in part responsible for this response but that other organic compounds also play important roles. The results indicate a NF-kB independent mechanism for IL-6 and IL-8 mRNA synthesis since NF-kB activation was not detected in our experiments. Nevertheless, numerous studies reports that PM induced cytokines through this factor (Andreau et al., 2012; Dagher et al., 2007; Li et al., 2013; Maciejczyk et al., 2010; Valko et al., 2005). IL-8 and IL-6 expression can also be regulated by transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms under the control of multiple signaling pathways. A different mechanism involves the transactivation of NF-κB in the absence of IκB degradation and nuclear translocation of the factor. The IκBα-independent pathways can involve post-translational modifications of NF-κB subunits, including site-specific phosphorylation of p65 as the induction of IL-8 reported in BEAS-2B cells exposed to metals such as the divalent zinc (Kim et al., 2005; Silbajoris et al., 2011). The IL-8 gene promoter region contains multiple 5′ regulatory elements, including binding sites for NF-κB, activator protein (AP) AP-1, AP-2, AP-3, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (C/EBP β) and interferon regulatory factor 1 (Tal et al., 2010). It has also been reported that BEAS-2B exposed for 4 hr to DEP induced IL-8 expression independently of NF-κB through a mechanism that requires AP-1 activity (Tal et al., 2010), which could also explain the lack of NF-kB activation. Nrf2 could modulate IL-8 expression directly or indirectly. This interleukin is known to be sensitive to changes in redox potential containing an ARE-like element in its promoter region (Zhang et al., 2005). The molecular basis of Nrf2- mediated IL-8 production has been reported to be mainly through enhanced mRNA stability (Silbajoris et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2005).

PM2.5ADE extract induced mRNA levels of IL-6 yet no evidence of NF-kB activation at 4 hr was detected. It has been shown that the promoter-region of the IL-6 gene contains a series of regulatory elements, C/EBP, cAMP response element (CRE), TPA (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate), AP-1, as well as Nrf2 (Wruck et al., 2013). Any of these mechanisms could have been activated by which IL-6 induction could be explained however, the testing of these alternate mechanisms other than Nrf2 were beyond the scope of this research. The response observed here is supportive of the idea that both IL-8 and Nrf2 protect pulmonary epithelial cells against oxidative stress (Waxman and Kolliputi 2009; Wruck et al., 2013).

4. Summary and Conclusions

The global phenomenon of continental sediment transport across the Atlantic Ocean by means of African dust storms has impacted the island of PR and the Caribbean for ages. The impact of this global event on ecosystems and human health in different countries are still under investigation and are under the influence of local environments. This study shows that ADE (storm material) and Non-ADE samples (local sources in Puerto Rico representing background air) both contain constituents such as trace elements and organics (due to extraction methods) that generate ROS inducing oxidative stress which triggers the signaling cascade for the activation of Nrf2. Some of these contaminants (such as metals) are the same found in PR and with the advent of a storm increases its local concentration and incorporates additional constituents from the storm. Since the extracts are a result of an organic extraction they contain organics (not directly measured nor identified in this study) that may be responsible for the difference observed between Non-ADE and ADE regarding OC, TAC and the activation of Nrf2. Our approach was to study the effects of metals in the storm by selectively applying the use of a metal chelator. The results obtained employing this strategy showed that metals are not entirely responsible for the oxidation responses. Differences in the OC, TAC, the activation of Nrf2 and the magnitude of the mRNAs synthesis (HMOX1, GSTP1, IL-8) as well as pro-inflammatory genes (IL-6 and IL-8) and proteins all support that there must be differences in the composition and properties between ADE and Non-ADE local PM. In addition, we discovered that the mechanism for IL-8 and IL-6 genes expression is independent of NF-kB activation.

These findings are important in understanding lung defenses against oxidative stress mediated by particulate pollutants and may help characterize population susceptibility (exacerbation of asthma and/or cardiovascular diseases). In the early phase of inflammation, oxidative stress does not directly cause cell damage and can induce defense mechanisms including the induction of antioxidant genes (Lodovici and Bigagli 2011). A detailed analysis of ADE constituents and its effects on the regulatory mechanisms of Nrf2 and cytokines can help designed medical therapies in susceptible population.

Highlights.

The oxidative capacity of African dust extract depended on its metal composition.

ADE and Non-ADE extracts both generate ROS and induce GSTP1, HMOX1, and IL-8 mRNAs.

African dust extract induced oxidative stress in exposed cells.

Inflammatory response mRNAs were induced although NF-kB was not detected.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (8G12-MD007600), National Center for Research Resources (2G12RR003051) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R25GM061838) of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- ADE

African dust events

- Non-ADE

non African dust events

- BEAS-2B

human bronchial epithelial cells

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- DF

deferoxaminemesylate

- NAC

N-acetyl-L-cysteine

- GSTP1

Glutathione-S-transferase

- HMXO1

hemeoxygenase 1 mRNA

- Nrf2

erythroid 2-related factor 2

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-kappa B

- IL

interleukin

- PM

particulate matter

- PR

Puerto Rico

- NASA

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

- TOMS

Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer

- USEPA

United States Environmental Protection Agency

- WHO

World Health Organization

- DEP

diesel exhaust particles

- LPS

lipopolysacharide

- OC

oxidative capacity

- TMET

traces of metals

- TAC

total antioxidant capacity

- PR-EQB

PR Environmental Quality Board

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- DCF

2′7 dichlorofluorescein

- PAC

polycyclic aromatic compound

- I-κB

NF-κB inhibitory protein

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Rosa I. Rodríguez-Cotto, Email: rosa.rodriguez5@upr.edu.

Mario G. Ortiz-Martínez, Email: mariojlopr@yahoo.es.

References

- Air and Radiation. US Environmental Protection Agency; 2008. Retrieved on April 6, 2014. http://www.epa.gov/air/criteria.html. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar U, McWhinney R, Rastogi N, Abbatt J, Evans J, Scott J. Cytotoxic and proinflammatory effects of ambient and source-related particulate matter (PM) in relation to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cytokine adsorption by particles. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22(S2):37–47. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.518377. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/08958378.2010.518377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinbami OJ, Moorman JE, Xiang LX. Asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality: United States, 2005–2009. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. http://198.246.124.22/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr032.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Andreau K, Leroux M, Bouharrour A. Health and cellular impacts of air pollutants: From cytoprotection to cytotoxicity. Biochem Res Int. 2012:18. doi: 10.1155/2012/493894. ID 493894. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/493894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Aust AE, Ball JC, Hu AA, Lighty JS, Smith KR, Straccia AM, Veranth JM, Young WC. Particle characteristics responsible for effects on human lung epithelial cells. Research Report (Health Effects Institute) 2002;110:1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishna S, Lomnicki S, McAvey K, Cole R, Dellinger B, Cormier S. Environmentally persistent free radicals amplify ultrafine particle mediated cellular oxidative stress and cytotoxicity. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2009;6(1) doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-6-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1743-8977-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker S, Mundandhara S, Devlin R, Madden M. Regulation of cytokine production in human alveolar macrophages and airway epithelial cells in response to ambient air pollution particles: further mechanistic studies. Toxicol Appl Pharm. 2005;207:269–75. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.01.023. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2005.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Xu H, Xu Q, Chen B, Kan H. Fine particulate matter constituents and cardiopulmonary mortality in a heavily polluted chinese city. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(3) doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103671. http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1103671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter J, Ghio A, Samet J, Devlin R. Cytokine production by human airway epithelial cells after exposure to an air pollution particle is metal dependent. Toxicol Appl Pharm. 1997;146:180–188. doi: 10.1006/taap.1997.8254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/taap.1997.8254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho AK, Sioutas C, Kumagai MAHY, Schmitz DA, Singh M, Eiguren-Fernandez A, Froines RJ. Redox activity of airborne particulate matter at different sites in the Los Angeles Basin. Environ Res. 2005;99:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2005.01.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Reddy S, Kleeberger S. Nrf2 defends the lung from oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8(1–2):76–87. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colarco PR, Toon OB, Reid J, Livingston JM, Russell PB, Redemann J, Schmid B, Maring H, Savoie D, Welton J, Campbell JR, Holben B, Levy R. Saharan dust transport to the Caribbean during PRIDE: 2. Transport, vertical profiles, and deposition in simulations of in situ and remote sensing observations. J Geophys Res. 2003;108(D19):Art. No. 8590. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002658 http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002659. [Google Scholar]

- Dagher Z, Garçon G, Billet S, Verdin A, Ledoux F, Courcot D, Shirali P. Role of nuclear factor-kappa B activation in the adverse effects induced by air pollution particulate matter (PM2. 5) in human epithelial lung cells (L132) in culture. J Appl Toxicol. 2007;27(3):284–290. doi: 10.1002/jat.1211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jat.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Rui W, Zhang F, Ding W. PM2.5 induces Nrf2-mediated defense mechanisms against oxidative stress by activating PIK3/AKT signaling, pathway in human lung alveolar epithelial A549 cells. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2013;29:143–157. doi: 10.1007/s10565-013-9242-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10565-013-9242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano E, Eiguren-Fernandez A, Delfino J, Sioutas C, Froines J, Cho AK. A determination of metal-based hydroxyl radical generating capacity of ambient and diesel exhaust particles. Inhal Toxicol. 2009;21:731–738. doi: 10.1080/08958370802491433. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08958370802491433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand-Hammarström B, Magnusson R, Österlund C, Andersson B, Bucht A, Wingfors H. Oxidative stress and cytokine expression in respiratory epithelial cells exposed to well-characterized aerosols from Kabul, Afghanistan. Toxicol In Vitro. 2013;27(2):825–833. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2012.12.022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tiv.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esworthy R. Air quality: EPA’s 2013 changes to the particulate matter (PM) standard, Congressional Research Service; 7–5700. 2013 Retrieved on April 6, 2014 http://archive.nationalaglawcenter.org/assets/crs/R42934.pdf.

- Forman H, Torres M. Reactive Oxygen Species and Cell Signaling, Respiratory Burst in Macrophage Signaling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:s4–s8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2206007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.2206007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison V, Lamothe P, Morman S, Plumlee G. Trace-metal concentrations in African dust: Effects of long-distance transportand implications for human health. 19th World Congress of Soil Science, Soil Solutions for a Changing World; 1–6 August; 2010. http://www.ldd.go.th/swcst/Report/soil/.%5Csymposium/pdf/D4.2.pdf#page=35. [Google Scholar]

- Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico, 2013. Mexico’s urban air pollution remains the worst in Latin America. Retrieved on May, 2014. http://geo-mexico.com/?p=9587.

- Gioda A, Pérez U, Rosa Z, Jiménez-Vélez B. Particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5) from different areas of Puerto Rico. Fresenius Environ Bull. 2007;16(8) http://cetr.rcm.upr.edu/Docs/FEB_2007.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri M, Mantecca P, Corvaja V, Longhin E, Perrone MG, Bolzacchini E, Camatini M. Winter fine particulate matter from Milan induces morphological and functional alterations in human pulmonary epithelial cells (A549. Toxicol Lett. 2009;188:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.03.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock T, Desikan R, Neill S. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Cell Signaling Pathways Biochemical and Biomedical Aspects of Oxidative Modification. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29(2):345–350. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290345. http://dx.doi.org/10.1042/BST0290345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Chen MG, Ma Q. Activation of Nrf2 in Defense against Cadmium-Induced Oxidative Stress. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21(7):1375–1383. doi: 10.1021/tx800019a. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/tx800019a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii H, Hayashi S, Hogg J, Fujii T, Goto Y, Sakamoto N, Mukae H, Vincent R, Van Eeden SF. Alveolar macrophage-epithelial cell interaction following exposure to atmospheric particles induces the release of mediators involved in monocyte mobilization and recruitmet. Respir Res. 2005;6(87) doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-87. http://respiratory-research.com/content/6/1/87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Vélez B, Detrés Y, Armstrong R, Gioda A. Characterization of African dust (PM2.5) across the Atlantic Ocean during AEROSE 2004. Atmos Environ. 2009;43:2659–2664. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.01.045. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y-M, Reed W, Wu W, Bromberg P, Graves L, Samet J. Zn2-induced IL-8 expression involves AP-1, JNK, and ERK activities in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;290:L1028–L1035. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00479.2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00479.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Yang C. Role of NADPH oxidase/ROS in pro-inflammatory mediators-induced air way and pulmonary diseases. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84:581–590. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.05.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Hao M, Phalen R, Hinds W, Nel A. Particulate air pollutants and asthma: A paradigm for the role of oxidative stress in PM-induced adverse health effects. Clin Immunol. 2003;109:250–265. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2003.08.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Jawed A, Venkatesan IM, Fernández AE, Schmitz D, Di Stefano E, Slaughter N, Killeen E, Wang X, Huang A, Wang M, Miguel AH, Cho A, Sioutas C, Nel AE. Nrf2 is a key transcription factor that regulates antioxidant defense in macrophages and epithelial cells: protecting against the pro-inflammatory and oxidizing effects of diesel exhaust chemicals. J Immunol. 2004;173:3467–3481. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3467. http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Kim S, Wang M, Froines J, Sioutas C, Nel A. Use of a stratified oxidative stress model to study the biological effects of ambient concentrated and diesel exhaust particulate matter. Inhal Toxicol. 2002;14:459–486. doi: 10.1080/089583701753678571. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/089583701753678571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Xia T, Nel A. The role of oxidative stress in ambient particulate matter-induced lung diseases and its implications in the toxicity of engineered nanoparticles. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1689–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.028. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YJ, Shimizu T, Hirata Y, Inagaki H, Takizawa H, Azuma A, Omura S. EM, EM703 inhibit NF-kB activation induced by oxidative stress from diesel exhaust particle in human bronchial epithelial cells: importance in IL-8 transcription. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2013;26(3):318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2012.12.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pupt.2012.12.010 http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/jpet.113.207415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liby K, Hock T, Yore MM, Suh N, Place AE, Risingsong R, Williams CR, Royce DB, Honda T, Honda Y, Gribble GW, Hill-Kapturczak N, Agarwal, Sporn MB. The synthetic triterpenoids, CDDO and CDDO-imidazolide, are potent inducers of heme oxygenase-1 and Nrf2/ARE signaling. Cancer Res. 2005;65(11):4789–4798. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4539. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodovici M, Bigagli E. Review article: Oxidative stress and air pollution exposure. J Toxicol. 2011:Article ID 487074, 9, 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2011/487074. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2011/487074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Maciejczyk P, Zhong M, Lippmann M, Chen LC. Oxidant generation capacity of source-apportioned PM2.5. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22(S2):29–36. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.509368. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/08958378.2010.509368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod AK, McMahon M, Plummer SM, Higgins LG, Penning TM, Igarashi K, Hayes JD. Characterization of the cancer chemopreventive NRF2-dependent gene battery in human keratinocytes: demonstration that the KEAP1–NRF2 pathway, and not the BACH1–NRF2 pathway, controls cytoprotection against electrophiles as well as redox-cycling compounds. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(9):1571–1580. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp176. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgp176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinelli AR, Santacana GE, Madden MC, Jiménez BD. Toxicity and metal content of organic solvent extracts from airborne particulate matter in Puerto Rico. Environmental Research. 2006;102:314–325. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2006.04.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntziachristos L, Froines JR, Cho A, Sioutas C. Relationship between redox activity and chemical speciation of size-fractionated particulate matter. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2007;4(5) doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Martínez M, Rivera-Ramírez E, Méndez-Torres L, Jiménez-Vélez B. Role of chemical and biological constituents of PM10 from Saharan dust in the exacerbation of asthma in Puerto Rico. In: Theophanides M, Theophanides T, editors. Athens Institute for Educations & Research, Biodiversity Science for Humanity. 2010. pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Particulate matter (PM) standards table of historical PM NAAQS history of the National Ambient Air Quality Standards for particulate matter during the period 1971–2012. US Environmental Protection Agency; Retrieved on April 6, 2014 http://www.epa.gov/ttn/naaqs/standards/pm/s_pm_history.html#2. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Perdomo R, Pérez-Cardona C, Disdier-Flores O, Cintrón Y. Prevalence and correlates of asthma in the Puerto Rican population: behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2000. J Asthma. 2003;40(5):465–474. doi: 10.1081/jas-120018713. http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.1081/JAS-120018713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puerto Rico Environmental Quality Board. Oficina de Planificación y Evaluación. Informe sobre el estado y condición del ambiente en Puerto Rico 2002: Trasfondo histórico y situación actual. Oficina de Planificación y Evaluación. 2003 Retrieved on May, 2014. http://www.jca.pr.gov/

- Puerto Rico Environmental Quality Board, Oficina de Planificación y Evaluación. Informe sobre el estado y condición del ambiente en PR 2003 (Borrador): Aire. 2004 Retrieved on May, 2014. http://www.jca.pr.gov/

- Puerto Rico Environmental Quality Board. Oficina de Planificación y Evaluación. Informe sobre el estado y condición del ambiente en PR 2004: Capitulo 4 Recurso de Aire. 2005 Retrieved on May, 2014. http://www.jca.pr.gov/

- Reid EA, Reid JS, Meier MM, Dunlap MR, Cliff SS, Broumas A, Perry; K, Maring H. Characterization of African dust transported to Puerto Rico by individual and size segregated bulk analysis. J Geophys Res. 2003;108(D19):8591. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Cotto R, Ortiz-Martínez M, Rivera Rámirez E, Méndez L, Dávila JC, Jiménez-Vélez BD. African dust storms reaching Puerto Rican coast stimulate the secretion of IL-6 and IL-8 and cause cytotoxicity to human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) Health, Special Issue: PM2.5 Effects on Health. 2013;5(10B):14–28. doi: 10.4236/health.2013.510A2003. http://file.scirp.org/Html/3-8202441_38729.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schins R, Hei T. In: Genotoxic effects of particles. 1. Donaldson K, Borm P, Toxicology P, editors. New York: CRC Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Silbajoris R, Alvaro R, Osornio-Vargas AR, Simmons SO, Reed W, Bromberg PA, Dailey LA, Samet JM. Ambient particulate matter induces interleukin 8 expression through an alternative NF-κB (Nuclear Factor-Kappa B) mechanism in human airway epithelial cells. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(10):1379–1383. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103594. http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1103594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbajoris R, Huang J, Cheng W, Dailey L, Tal T, Jaspers I. Nanodiamond particles induce IL 8 expression through a transcript stabilization mechanism in human airway epithelial cells. Nanotoxicology. 2009;3(2):152–160. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17435390902725948. [Google Scholar]

- Squadrito G, Cueto R, Dellinger B, Pryor W. Quinoid redox cycling as a mechanism for sustained free radical generation by inhaled airborne particulate matter. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:1132–1138. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00703-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal TL, Simmons SO, Silbajoris R, Dailey L, Cho S, Ramabhadran R, Linak W, Reed W, Bromberg PA, Samet JM. Differential transcriptional regulation of IL-8 expression by human airway epithelial cells exposed to diesel exhaust particles. Toxicol Appl Pharm. 2010;243:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.11.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp J, Millero F, Prospero J. Temporal variability of the elemental composition of African dust measured in trade wind aerosols at Barbados and Miami. Mar Chem. 2010;120(1–4):71–82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2008.10.004. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi P, Aggarwal A. NF-kB transcription factor: a key player in the generation of immune response. Curr Sci. 2006;90:519–31. http://www.currentscience.ac.in/Downloads/article_id_090_04_0519_0531_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Turpaev K. Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway: Mechanisms of regulation and role in protection of cells against toxicity caused by xenobiotics and electrophiles. Biochem. MSK. 2013;78(2):147–166. doi: 10.1134/S0006297913020016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1134/S0006297913020016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentina R, Valverde M, Rojas E. Effects of atmospheric pollutants on the Nrf2 survival pathway. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2010;17:369–382. doi: 10.1007/s11356-009-0140-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11356-009-0140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M, Morris H, Cronin M. Metals, toxicity and oxidative stress. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:1161–1208. doi: 10.2174/0929867053764635. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/0929867053764635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Jiang R, Zhao Z, Song W. Effects of ozone and the particulate matter (PM2.5) on rat system inflammation and cardiac function. Toxicol Lett. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.11.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Waxman A, Kolliputi N. IL-6 Protects against Hyperoxia-Induced Mitochondrial Damage via Bcl-2–Induced Bak Interactions with Mitofusions. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:385–396. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0302OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wruck CJ, Konrad S, Pavic G, Götz ME, Tohidnezhad M, Brandenburg L-O, Varoga D, Eickelberg O, Herdegen T, Trautwein C, Cha K, Kan YW, Pufe T. Nrf2 induces interleukin-6 (IL-6) expression via an antioxidant response element within the IL-6 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:4493–4499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.162008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M110.162008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G, Wang M, Li N, Loo JA, Nel A. Use of proteomics to demonstrate a hierarchical oxidative stress response to diesel exhaust particle chemicals in a macrophage cell line. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50781–50790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306423200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M306423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. Mechanistic studies of the NRF2-KEAP1. Drug Metab Rev. 2006;38:769–789. doi: 10.1080/03602530600971974. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03602530600971974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Chen X, Song H, Chen H-Z, Rovin B. Activation of the Nrf2/antioxidant response pathway increases IL-8 expression. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:3258–3267. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/eji.200526116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]