Abstract

The renal vascular bed has a stereotypic architecture that is essential for the kidney’s role in excreting metabolic waste and regulating the volume and composition of body fluids. The kidney’s excretory functions are dependent on the delivery of the majority of renal blood flow to the glomerular capillaries, which filter plasma removing from it metabolic waste, as well as vast quantities of solutes and fluids. The renal tubules reabsorb from the glomerular filtrate solutes and fluids required for homeostasis, while the post-glomerular capillary beds return these essential substances back into the systemic circulation. Thus, the kidney’s regulatory functions are dependent on the close proximity or alignment of the post-glomerular capillary beds with the renal tubules. This review will focus on our current knowledge of the mechanisms controlling the embryonic development of the renal vasculature. An understanding of this process is critical for developing novel therapies to prevent vessel rarefaction and will be essential for engineering renal tissues suitable for restoring kidney function to the ever-increasing population of patients with end stage renal disease.

Keywords: kidney development, vascular patterning, angiogeneis, vasculogenesis

Introduction

The vascular bed of the kidney exhibits unique structural features that are essential for its function. Although the kidneys comprise less than 0.08% of body weight, they receive 20% of cardiac output. This magnitude of blood flow is not required for metabolic purposes. Rather, it reflects the kidney’s role in clearing the blood of metabolic waste, substances that are harmful or foreign, as well as fluids and ions that are in excess to body economy. Blood flows into the kidney via the renal artery, which enters the organ in a central fissure called the hilum. Although the renal artery is in close proximity to the medulla, less than 10% of arterial blood flow is delivered to this central region of the kidney. Instead, the major branches of the arterial tree conduct greater than 90% of renal blood flow directly to the glomerular capillary bed located in the peripheral, cortical region of the organ [1] (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Anatomy of the renal vascular bed.

Reconstructed scan of an entire mouse kidney corrosion cast by nano-CT A-C, [42]. Thresholding for large vessels (A) illustrates the stereotypic architecture of the renal artery and its major branches. As thresholding is adjusted to visualize smaller vessels, the cortical arterial tree up to the level of the intralobular arteries is detected (B). Finer thresholding allows for the visualization of the complex architecture of the cortical microvasculature (C). Corrosion cast of rat kidney imaged by scanning electronmicrogroscopy. The glomerului (g), peritubular capillaries (pt) and vasa recta (vr) are easily visualized. (E) A corrosion cast of an isolated glomerulus imaged by nano-CT illustrating the complexity of the capillary loops [42]. (F Representaion of a single nephron and its associated glomerulus (g), peritubular capillaries (pt) and vasa recta (vr).

Each of the approximately 1,000,000 glomeruli in the human kidney is composed of 6-8 capillary loops, and is embedded in the approximately 1,000,000 nephrons that comprise the human kidney (Figure 1 D-F). The glomerular endothelium is relatively permeable to fluids and low, but not high molecular weight solutes. The extended length of the glomerular capillary and its permeability properties, along with the location of the glomerular capillary between two high resistance arterioles, enables the glomeruli to produce a plasma ultrafiltrate that flows into urinary space at a rate of 125 ml/min. Notably, the tone of the two high resistance arterioles that flank the glomerulus plays a fundamental role in modulating this high rate of fluid flow out of the glomerular capillaries, which is approximately 50× greater than the rate of fluid flow out of any other systemic capillary beds.

After being filtered by the glomerulus, blood flows via the efferent arteriole into the peritubular capillaries. Blood entering the peritubular capillaries has a high oncotic pressure, due to the loss of fluids by glomerular filtration and retention of high molecular weight solutes. The relatively high oncotic pressure in the peritubular capillaries, exceeds the hydrostatic pressure across this capillary bed. Thus, the peritubulars are poised for the reabsorption of solutes and fluids lost by glomerular filtration, a function that is dependent on their close alignment with the cortical renal tubules (Figure 1 D and F). Specifically, the transporting epithelia of the renal tubules rebsorb from the glomerular filtrate, solutes and ions essential for homeostasis and then, the peritubular capillaries return these essential substances to the systemic circulation.

The renal vasculature also includes a third capillary bed, termed the vasa recta, which is in close alignment with the medullary renal tubules. The vasa recta emanate from the post-glomerular capillary bed and deliver oxygen and nutrients to the medullary region of the kidney. In addition, they return ions and solutes reabsorbed by the medullary renal tubules to circulation. The vasa recta follow the contours of the medullary renal tubules, descending deep into the medullary zone of the kidney and then back up to the cortex. The looped architecture and permeability of the renal medullary tubules and closely aligned vasa recta generate a gradient of increasing osmolarity in the medullary region of the kidney which is essential for conserving water during times of fluid deprivation. Thus, the vasa recta are essential for concentrating the urine, as well as for perfusing the medulla and returning to systemic circulation ions and water reabsorbed by the medullary renal tubules. After all these steps, blood is collected into a venous system at the cortical-medullary junction of the kidney and flows out of the kidney via the renal vein. It is likely that the renal lypmphatics also play a role draining plasma fluids out of the kidney although they remain rather poorly characterized. Studies by Lee et al. demonstrate thatvessels expressing the lymphatic maker lyve-1 are embedded in cortical, periarterial loose connective tissue, while studes by Madsen demonstrate that the medulla lacks lymphatics altogehter [1,2].

This brief description of the mature renal vascular bed well illustrates several of the architectural challenges that must be met as the kidney is vascularized during embryogenesis. These challenges include:

Formation of an arterial tree that conducts blood directly to the glomerular capillaries

Formation of the glomerular capillaries and their specialized features required for filtration

The alignment of the peritubular capillaries with the cortical renal tubules to facilitate the return of solutes and fluids lost by glomerular filtration back into the systemic circulation.

The aligment of the vasa recta with the looped, medullary tubules to facilitate the the generation of the medullary osmotic gradient and for reabsorption of solutes and fluids.

1. Derivation of cell types comprising the renal vascular bed

Blood vessels are comprised of endothelial cells and associated vascular mural cells (VMCs), including pericytes and vascular smooth muscle. The endothelial cells form tubes that carry the blood, whereas the VMCs control vessel tone and provide the structural support necessary for accommodating blood flow. Both endothelia and VMC progenitors are present in the metanephric blastema, the mesenchymal cell population comprising the embryonic kidney rudiment at its inception. Genetic fate mapping experiments demonstrate that Foxd1+ cells present at the periphery of the metanephric blastema give rise to most, if not all, VMCs and interstitial fibroblasts (personal observation,Figure 2)[3]. Turfro and colleagues, in turn, first showed that Flk1+ mesenchymal cells present within the metanephric blastema can form primitive vascular networks in kidney rudiments cultured under low oxygen tension [4]. This capability of Flk1+ mesenchyme to give rise to a primitive vasculature was subsequently confirmed by several other groups using in vitro and in vivo explant assays [5-8].

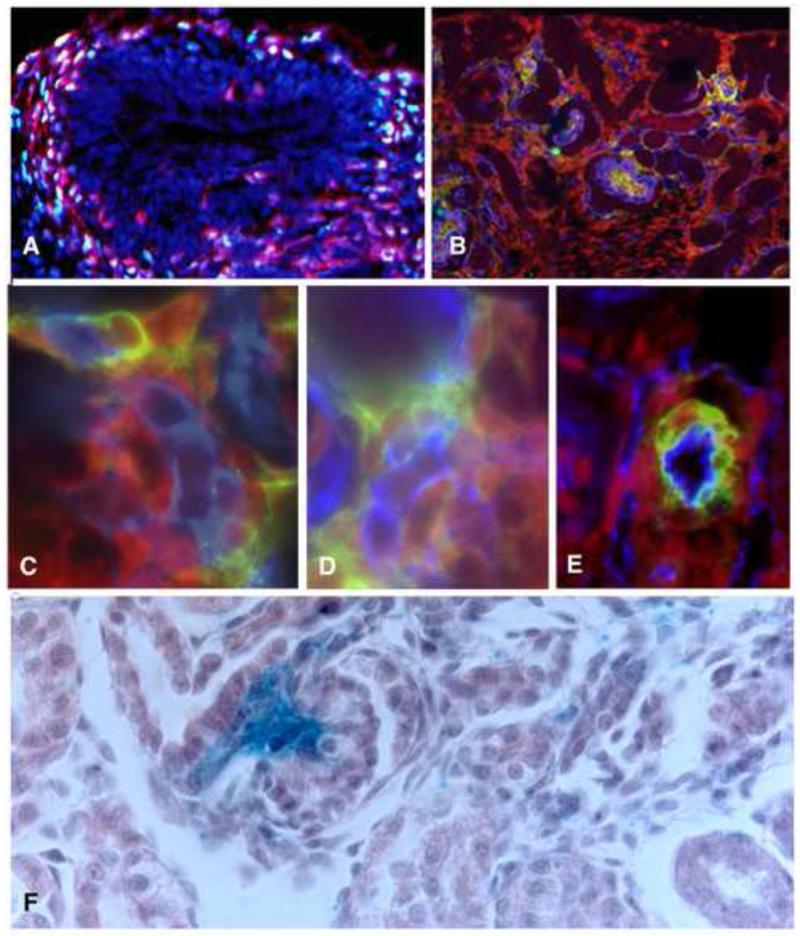

Figure 2. The Foxd1 lineage gives rise to vascular mural cells.

A) Immunoflorescent image of an E11.5 mouse kidney rudiment expressing YFP in the Foxd1 lineage (red) co-stained with antibodies specific for Foxd1 (green). Most if not all YFP+ cells express Foxd1 at this early stage of renal development. B) Immunoflorescent image of E15.5 mouse kidney expressing YFP in Foxd1 derived cells, co-stained for the endothelial marker VE-Cadherin (blue) and the mural cell marker (green), Platelet derived growth factor Receptor –β PDGFR– βC-E Cells derived from the Foxd1 lineage (red) closely associated with nascent blood vessels (blue) express mural cell markes including PDGFR-β (C), NG2 (D) and SMA (E). In the mature kidney, Foxd1 derived cells labeled with blue, b-gal reaction product are present in the glomerulus (g) with a distrubution consistent with mesganigal cells(m) and around renal vessels (v).

However, to date, it is not known if Flk1+ cells present in the newly formed embryonic kidney rudiment give rise to all the endothelia of the renal vascular bed. It is possible that the renal vascular bed is composed of endothelia derived from Flk1+ progenitors present in the early kidney rudiment, as well as endothelia derived from pre-formed vessels that grow into the developing kidney. Data supporting the latter hypothesis was first published by Sariola in the 1980s, who demonstrated that embryonic kidney rudiments cultured on the chick chorioallantoic membrane were vascularized by host, avian endothelia[9]. Abrahamson and colleagues confirmed and extended these results[6]. In an elegant series of grafting experiments, they showed that embryonic kidney rudiments grafted on to the neonatal mouse kidney cortex, were invaded and vascularized by host endothelia. Importantly, the ability of endothelia from extra-renal vessels to contribute to the renal vascular bed is dependent on the differentiated stage of the host. Specifically, host tissues with vessels actively undergoing angiogenesis are competent to contribute to the renal vascular bed, whereas fully differentiated host tissues are not [6].

As indicated by the elegant experiments performed by Sariola, Abrahamson and others, the exact lineage of the renal endothelia may not be of significance. Specifically, the embryonic kidney rudiment possesses the appropriate cues to recruit endothelia into its vascular bed. However, it is important to note here that although embryonic renal tissues can be vascularized by endothelia derived from host tissues, it is unclear if endothelia recruited from extra-renal vessels can develop the differentiated characteristics of specialized renal vessels such as the glomerular capillaries. Importantly, work performed in other embryonic systems has demonstrated that the lineage of endothelial cells within an organ does not determine the terminally differentiated characteristics of that endothelium [10]. For example, when embryonic vessels isolated from the developing quail gut are transplanted to the developing avian brain, the transplanted vessels, which normally possess a permeable endothelial layer that facilitates nutrient uptake, form a sealed monolayer characteristic of the blood brain barrier [11]. Thus, local environmental cues, not the lineage of the endothelial layer, may control the terminally differentiated phenotype of blood vessels within each segment of the renal vascular bed.

2. Formation of the arterial tree

The structure of the arterial tree is critical for directing greater than 90% of renal blood flow directly to the glomeruli for filtration. However, the mechanisms that pattern the renal arterial tree during embryonic development remain poorly understood. Microdissection analyses of embryonic and neonatal kidneys demonstrate that a very rudimentary vascular network is present in the developing kidney by E14.5, and that this vascular bed becomes progressively more complex throughout embryonic development and in the first weeks of post-natal life [12]. It is likely that these vessels revealed by microdissection represent the blood conducting arterial tree, but molecular marker analyses have not yet confirmed this hypothesis. To this end, we have analyzed the pattern of arterial vessels in the intact metanephric rudiment at several different developmental stages via micro-angiography and high resolution imaging in 3D (Figure 3). To label the embryonic arterial tree a fluorescent lectin (TL lectin) that binds to the endothelium, was injected into the embryonic circulation by cardiac puncture. TL lectin labeled vessels express the arterial marker Dll4 indicating that they are indeed, the beginnings of the renal arterial tree [13, 14] (data not shown). Results of our analyses demonstrate that the aorta gives rise to several arterial branches that penetrate the E12.5 embryonic kidney rudiment (Figure 3A, whole mount; B, high magnification). At E13.5, this stochastic network of vessels is remodeled into a single renal artery with 3-4 major lateral branches (Figure 3C). As can be seen in Figure 3 D, by E17.5 the arterial tree extends through the medullary zone of the kidney with very little branching, suggesting that the vessels may extend through this region via interstitial growth. In contrast, extensive arterial branching is evident in the cortex where the terminal branches of the arterial tree, the afferent arterioles, bring blood to the glomeruli. The signaling factors that mediate cortical arterial branching during embryonic development remain unknown, although several studies indicate that post-natal branching of the renal vascular tree is mediated by the renin -angiotensin system [15]. Finally, it is likely that the pattern of arterial branching in the developing kidney is dictated by local cues present in the cortical and medullary regions of the kidney. For example, the cortical regions of the kidney are populated by differentiating podocytes, the specialized epithelial cells that enwrap the glomerular capillary. These cells secrete abundant levels of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), which promotes vessel branching, as well as endothelial proliferation and survival [16, 17]. Thus, signaling between differentiating renal epithelia and the nascent arterial tree is likely to control arterial branching in the cortex.

Figure 3. Development of the renal arterial tree.

To determine the structure of the renal vasculature in the developing kidney, fluorescent-labeled lectin was injected into the embryonic circulation at various stages. Lectin binds to vascular endothelia, thus serving to mark the conducting blood vessels. At E12.5 lateral branches coming off the central aorta can be seen invading the developing embryonic kidney rudiment arrows (A, whole mount; B, high magnification). By E13.5 the renal vasculature consists of a central artery (c) that gives rise to 3-4 major lateral braches (l) (C). Analyses at E17.5 revealed the stereotypic architecture that is characteristic of the renal arterial tree (D), with a paucity of blood vessel branching in the central medullary region of the kidney, and more extensive branching in the outer cortical region of the kidney.

3. Glomerulus Formation

Formation of the glomerulus occurs in several stages and is dependent on signaling between the different cell types associated with the glomerular capillary[18]. These cells include specialized pericytes called mesangial cells, and podocytes, the specialized epithelial cells that enwrap the glomerular capillary [1]. To discuss glomerular formation, it is necessary to first provide a brief description of the stages of renal epithelial morphogenesis that form the nephron, the functional unit of the kidney. This process can be sub-divided into discreet stages including condensation of the mesenchymal nephron progenitors into pre-tubular aggregates, formation of a cyst like epithelial structure called the renal vesicle, and then conversion of the renal vesicle into an S-shaped body (Figure 4) [19]. At the S-shaped body stage, the previously homogeneous population of nephron epithelial progenitors begins to diversify into the mature, segmented nephron. Specifically, discreet regions of the S-shaped body begin to express molecular markers denoting the glomerular podocytes, the proximal tubule, and the distal tubular nephron segments. Notably, glomerular formation initiates at the S-shaped body stage when endothelial progenitors appear within a cleft-like structure adjacent to the maturing podocytes. Next, these endothelia form a single capillary loop, which subsequently matures into the 6-8 capillary loops comprising the mature glomerular capillary tuft.

Figure 4. Endothelia are detected in the developing nephron at the S-shaped body stage.

Nephrogenesis can be sub-divided into at least 3 stages including the condensation of mesenchymal nephron progenitors into pretubular aggregates, the conversion of the pretubular aggregate into an the renal epithelial vesicle, and finally the generation of diverse nephron cells types from the homogeneous epithelial progenitors present in the renal vesicle. Endothelial progenitors (red) first appear within a crevice of the S-shaped body.

A number of signaling factors mediating glomerulogenesis have been identified by ablating genes mediating blood vessel formation in other organ systems [20]. In addition, it is clear that hypoxia, triggers the expression of angiogenic factors in the kidney, as it does in other organs [4, 20]. Although the signaling pathways that initiate the invasion of endothelial cells into the S-shaped body crevice remain elusive, it is likely that VEGF plays a role in this process [4]. Targeted podocyte ablation of VEGF greatly reduces the number of endothelia comprising the nascent glomerulus consistent with the well established role of VEGF in supporting endothelial migration, proliferation and survival [21]. In contrast, podocyte deletion of another factor known to control vascular patterning, Semaphorin 3a, results in glomerular capillary hyperplasia [22]. This glomerular phenotype is likely due to the well established role of Semaphorin 3a in repelling endothelia [17, 23]. Conversely, podocyte over expression of Sema 3a leads to apoptosis of glomerular endothelia resulting in a decreased number of endothelia in the glomerulus [22]. Collectively, these data highlight the role podocytes play in controlling glomerulogenesis and indicate that formation of the glomerular capillary is dependent on pro- and anti-angiogenic signaling pathways that are common to other blood vessels.

The vast majority of genes that have been shown to be essential for glomerulogenesis mediate the maturation of the glomerulus from the capillary loop stage vessel into a mature, looped capillary tuft. Ablation of this set of genes results in the formation of glomerular capillaries that exhibit dilated capillary loops or a single capillary loop that resembles an aneurysm. For example, targeted deletion of either Platelet derived growth factor B (PDGF B), a factor secreted by endothelia that facilitates vessel maturation, or PDGF-Receptor β, which is expressed by mesangial cells, results in a gross deficit of mesangial cells and aneurysm-like glomerular capillaries [24-27]. Thus, endothelia play a role in mesangial cell expansion and mesangial cells, in turn, are essential for glomerular tuft maturation. Similarly, ablation of RBPJ, the main transcriptional transducer for Notch signaling, results in an absence of mesangial cells and aneurysm-like glomerular capillaries [28, 29]. Moreover, both mesangial cells and podocytes express CXCL12, a high affinity ligand for CXCR4, which is expressed by endothelial cells. Targeted deletion of either the CXCR4 receptor or the CXCL12 ligand results in ballooned, single loop glomerular capillaries [30]. Finally, Jeansen et al. demonstrate that targeted deletion of Angiopoietin-1, a secreted factor that activates endothelial Tie-2 receptors to facilitate vessel maturation, results in dilated glomerular capillary loops [31]. Interestingly, the glomeruli in angiopoetin-1 null kidneys possess the full complement of mesangial cells. However, the glomerular basement membrane that is normally secreted by podocytes and glomerular endothelia is abnormal. In summary, these studies elucidating the mechanisms underlying glomerular formation highlight the crucial role that signaling between the nascent glomerular endothelia, podocytes and mesangial cells play in this process.

4. The post-glomerular circulation

A distinguishing feature of both the peritubular capillaries and vasa recta, is their alignment with the renal tubules. The alignment of the post-glomerular capillary beds with the renal tubules is most likely regulated by the vast array of angiogenic factors secreted by the renal tubules. For example, the developing renal tubules express VEGF, and VEGF levels in the mature kidney correlate with the expansion or regression of peritubular capillaries [32]. In addition, Madsen and colleagues show that the mechanisms controlling angiotensin II-dependent vasa recta formation during post-natal development is mediated by increased VEGF secretion from the renal tubules [33]. Similarly, the renal tubules express abundant levels of TGF-β, which is essential for the maturation of endothelial progenitors into patent vessels [34]. Signaling between CXCR4 expressing endothelia and CXC12 expressing vascular mural cell progenitors is essential for regulating both the diameter and distribution of the peritubular capillaries within the renal cortex[30]. Angiopoeitin-2 is another angiogenic factor that modulates peritubular capillary architecture. Ang2, antagonizes Ang1-dependent Tie2 signaling by endothelia, which in turn, promotes vascular mural cell differentiation [35]. A possible role for vascular mural cells in patterning the renal vasculature is also suggested by studies analyzing the renal phenotype of mice with mutations in the Foxd1-vascular mural lineage. Targeted deletion of Foxd1, a forkhead transcription factor, results in abnormal vascularization of the renal capsule [36]. Genetic ablation of the Foxd1 lineage itself, results in a dense mat of cortical capillaries, rather than the repeating, hexagonal pattern of peritubular capillaries surrounding developing nephrons [37]. However, it is unclear if these abnormal vascular phenotypes are due directly to perturbations in the Foxd1 lineage. For example, Foxd1-ablation and the ablation of all Foxd1 progenitors leads to gross defects in nephron patterning. Thus, these epithelial patterning abnormalities may alter the expression pattern of epithelial-derived angiogenic factors, which in turn are essential for renal vascular patterning.

5. Conclusion and future perspectives

Renal vascular development, like renal epithelial development, is dependent on signaling between the diverse progenitor populations present in the metanephric blastema. Although progress has been made in identifying some of the signaling pathways mediating these interactions, many important questions concerning renal vascular patterning remain. Some of the central questions include: 1) How is the connection between the glomerulus and the renal arterial tree established? One possibility is that the glomerulus forms as an outgrowth from a distal tip of the arterial tree. Alternatively, the glomerulus may develop de novo within the nephron and subsequently hook up with the branching arterial tree; 2) What are the roles of renal epithelia and mural cells in vascular patterning? For example, the renal epithelia may pattern the vasculature via the secretion of angiogenic factors. In contrast, the Foxd1-derived vascular mural cells may modulate patterning by stabilizing nascent vessels making them refractory to epithelial derived angiogenic factors; 3) What are the signaling factors that initiate aortic branching into the developing kidney and what factors mediate the remodeling of these branches into a single renal artery? Based on the literature describing vascular remodeling in the retina, it is likely that vessel pruning eliminates many of the aortic branches that first grow into the kidney, but this has not been directly shown. Moreover, substantial data in other systems indicate that hemodynamic factors play a role in this process [38, 39]; 4) Does increased O2 tension due to perfusion of nascent vessels promote or limit nephrogenesis? For example, in the developing pancreas, increased O2 tension resulting from vessel perfusion leads to β cell differentiation, and a recent elegant study by Sims-Lucan suggests nephrogenesis is also promoted by elevated 02 tension[40, 41]; 5) Finally, can endothelia derived from extra-renal vessels differentiate into the specialized endothelia of the glomerulus? Although data from other developing systems suggest that local environmental factors dictate the final differentiated properties of the endothelia, a definitive answer to this question is central for future translational applications.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Alda Tufro for critically reading this masuscript. This work was supported by NIH DK45218 awarded to DH.

References

- [1].Madsen C, Nielsen S, Tisher C. The Anatomy of the Kidney. In: Rector Ba., editor. The Kidney. 8th ed. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lee HW, Qin YX, Kim YM, Park EY, Hwang JS, Huo GH, et al. Expression of lymphatic endothelium-specific hyaluronan receptor LYVE-1 in the developing mouse kidney. Cell Tissue Res. 343:429–44. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Humphreys BD, Lin SL, Kobayashi A, Hudson TE, Nowlin BT, Bonventre JV, et al. Fate tracing reveals the pericyte and not epithelial origin of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 176:85–97. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tufro-McReddie A, Norwood VF, Aylor KW, Botkin SJ, Carey RM, Gomez RA. Oxygen regulates vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated vasculogenesis and tubulogenesis. Dev Biol. 1997;183:139–49. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Woolf AS, Loughna S. Origin of glomerular capillaries: is the verdict in? Exp Nephrol. 1998;6:17–21. doi: 10.1159/000020500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Abrahamson DR, Robert B, Hyink DP, St John PL, Daniel TO. Origins and formation of microvasculature in the developing kidney. Kidney Int Suppl. 1998;67:S7–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.06702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hyink DP, Abrahamson DR. Origin of the glomerular vasculature in the developing kidney. Semin Nephrol. 1995;15:300–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hyink DP, Tucker DC, St John PL, Leardkamolkarn V, Accavitti MA, Abrass CK, et al. Endogenous origin of glomerular endothelial and mesangial cells in grafts of embryonic kidneys. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:F886–99. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.270.5.F886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sariola H, Ekblom P, Lehtonen E, Saxen L. Differentiation and vascularization of the metanephric kidney grafted on the chorioallantoic membrane. Dev Biol. 1983;96:427–35. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Risau W, Hallmann R, Albrecht U, Henke-Fahle S. Brain induces the expression of an early cell surface marker for blood-brain barrier-specific endothelium. EMBO J. 1986;5:3179–83. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04627.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wiley Sa. Developing nervous tissue induces formation of blood-brain barrier characteristics in invading endothelial cells: A study using quail-chick transplantation chimeras. Dev Biol. 1981;84:183–92. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90382-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sequeira Lopez ML, Gomez RA. Development of the renal arterioles. J Am Soc Nephrol. 22:2156–65. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011080818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhang G, Zhou J, Fan Q, Zheng Z, Zhang F, Liu X, et al. Arterial-venous endothelial cell fate is related to vascular endothelial growth factor and Notch status during human bone mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2957–64. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wythe JD, Dang LT, Devine WP, Boudreau E, Artap ST, He D, et al. ETS factors regulate Vegf-dependent arterial specification. Dev Cell. 26:45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tufro-McReddie A, Romano LM, Harris JM, Ferder L, Gomez RA. Angiotensin II regulates nephrogenesis and renal vascular development. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:F110–5. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.269.1.F110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Robert B, Zhao X, Abrahamson DR. Coexpression of neuropilin-1, Flk1, and VEGF(164) in developing and mature mouse kidney glomeruli. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;279:F275–82. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.2.F275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Eichmann A, Makinen T, Alitalo K. Neural guidance molecules regulate vascular remodeling and vessel navigation. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1013–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.1305405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Quaggin SE, Kreidberg JA. Development of the renal glomerulus: good neighbors and good fences. Development. 2008;135:609–20. doi: 10.1242/dev.001081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Saxen L. Organogenesis of the Kidney. Cambridge University Press; London: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6:389–95. doi: 10.1038/74651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Eremina V, Sood M, Haigh J, Nagy A, Lajoie G, Ferrara N, et al. Glomerular-specific alterations of VEGF-A expression lead to distinct congenital and acquired renal diseases. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:707–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI17423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Reidy KJ, Villegas G, Teichman J, Veron D, Shen W, Jimenez J, et al. Semaphorin3a regulates endothelial cell number and podocyte differentiation during glomerular development. Development. 2009;136:3979–89. doi: 10.1242/dev.037267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gelfand MV, Hong S, Gu C. Guidance from above: common cues direct distinct signaling outcomes in vascular and neural patterning. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Leveen P, Pekny M, Gebre-Medhin S, Swolin B, Larsson E, Betsholtz C. Mice deficient for PDGF B show renal, cardiovascular, and hematological abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1875–87. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lindahl P, Hellstrom M, Kalen M, Karlsson L, Pekny M, Pekna M, et al. Paracrine PDGFB/PDGF-Rbeta signaling controls mesangial cell development in kidney glomeruli. Development. 1998;125:3313–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.17.3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lindahl P, Johansson BR, Leveen P, Betsholtz C. Pericyte loss and microaneurysm formation in PDGF-B-deficient mice. Science. 1997;277:242–5. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Betsholtz C. Biology of platelet-derived growth factors in development. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2003;69:272–85. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.10030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Boyle SC, Liu Z, Kopan R. Notch signaling is required for the formation of mesangial cells from a stromal mesenchyme precursor during kidney development. Development. 141:346–54. doi: 10.1242/dev.100271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lin EE, Sequeira-Lopez ML, Gomez RA. RBP-J in FOXD1+ renal stromal progenitors is crucial for the proper development and assembly of the kidney vasculature and glomerular mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 306:F249–58. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00313.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Takabatake Y, Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Matsusaka T, Kurihara H, Koni PA, et al. The CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 axis is essential for the development of renal vasculature. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1714–23. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jeansson M, Gawlik A, Anderson G, Li C, Kerjaschki D, Henkelman M, et al. Angiopoietin-1 is essential in mouse vasculature during development and in response to injury. J Clin Invest. 121:2278–89. doi: 10.1172/JCI46322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Woolf AS. Do kidney tubules serve an angiogenic soup? Kidney Int. 2004;66:862–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Madsen K, Marcussen N, Pedersen M, Kjaersgaard G, Facemire C, Coffman TM, et al. Angiotensin II promotes development of the renal microcirculation through AT1 receptors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 21:448–59. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009010045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bridgewater D, Di Giovanni V, Cain JE, Cox B, Jakobson M, Sainio K, et al. beta-catenin causes renal dysplasia via upregulation of Tgfbeta2 and Dkk1. J Am Soc Nephrol. 22:718–31. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Pitera JE, Woolf AS, Gale NW, Yancopoulos GD, Yuan HT. Dysmorphogenesis of kidney cortical peritubular capillaries in angiopoietin-2-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1895–906. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63242-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Levinson RS, Batourina E, Choi C, Vorontchikhina M, Kitajewski J, Mendelsohn CL. Foxd1-dependent signals control cellularity in the renal capsule, a structure required for normal renal development. Development. 2005;132:529–39. doi: 10.1242/dev.01604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hum S, Rymer C, Schaefer C, Bushnell D, Sims-Lucas S. Ablation of the renal stroma defines its critical role in nephron progenitor and vasculature patterning. PLoS One. 9:e88400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Stahl A, Connor KM, Sapieha P, Chen J, Dennison RJ, Krah NM, et al. The mouse retina as an angiogenesis model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 51:2813–26. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].le Noble F, Fleury V, Pries A, Corvol P, Eichmann A, Reneman RS. Control of arterial branching morphogenesis in embryogenesis: go with the flow. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:619–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Shah SR, Esni F, Jakub A, Paredes J, Lath N, Malek M, et al. Embryonic mouse blood flow and oxygen correlate with early pancreatic differentiation. Dev Biol. 349:342–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Rymer C, Paredes J, Halt K, Schaefer C, Wiersch J, Zhang G, et al. Renal blood flow and oxygenation drive nephron progenitor differentiation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00208.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wagner R, Van Loo D, Hossler F, Czymmek K, Pauwels E, Van Hoorebeke L. High-resolution imaging of kidney vascular corrosion casts with Nano-CT. Microsc Microanal. 17:215–9. doi: 10.1017/S1431927610094201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]