Abstract

The synthesis of libraries of conformationally-constrained peptide-like oligomers is an important goal in combinatorial chemistry. In this regard an attractive building block is the N-alkylated peptide, also known as peptide tertiary amide (PTA). PTAs are strongly biased conformationally due to allylic 1,3 strain interactions. We report here an improved synthesis of these species on solid supports through the use of reductive amination chemistry using amino acid-terminated, bead-displayed oligomers and diverse aldehydes. The utility of this chemistry is demonstrated by the synthesis of a library of 10,000 mixed peptoid-PTA oligomers.

Keywords: Peptoid, reductive amination, solid-phase synthesis, combinatorial chemistry, peptide

Introduction

One bead one compound (OBOC) libraries created via split and pool solid-phase synthesis1 are a rich source of protein ligands. An important goal in this field is to create diverse libraries of conformationally constrained molecules that would likely bind to proteins with higher affinity than molecules lacking such constraints, such as linear peptides or peptoids2. N-methyl peptides have long been known to be highly constrained molecules due to allylic 1,3 strain effects and often have better pharmacological properties than simple peptides.3 Therefore, we became interested in the creation of libraries of diverse N-alkylated peptides, also called peptide tertiary amides (PTAs). Some of these molecules can be accessed via Fukuyama-Mitsunobu reaction, though this process requires protection of most functional groups.4 We reported the synthesis of these molecules by extending a chain through acylation with a chiral 2-bromo acid followed by displacement of bromide with an amine (Fig. 1a).5 This chemistry mirrors the “sub-monomer” route developed by Zuckermann and co-workers for the synthesis of peptoids.6 Certain 2-bromocarboxylic acids can be synthesized from amino acids in high enantiomeric purity but this conversion requires harsh acidic conditions that limits its scope with respect to amino acid starting materials.7

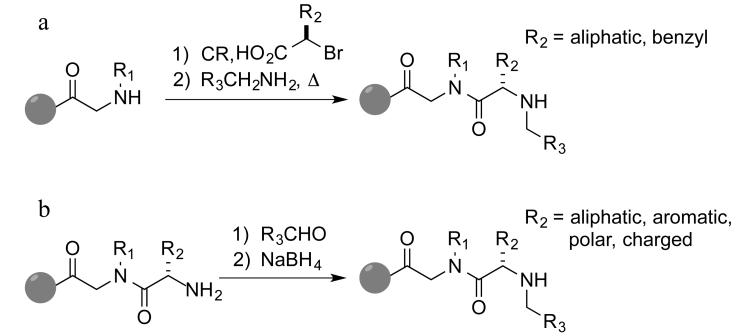

Figure 1.

Submonomer syntheses of peptoid and peptide tertiary amide (PTA) on the solid phase. (a) Haloacid submonomer route (b) Reductive amination route (this work) CR = coupling reagent.

An alternative to the use of chiral bromides and amines to create PTAs would be to build them from amino acids and aldehydes using reductive amination (Figure 1b). Appella and co-workers have employed reductive amination successfully on TentaGel beads in the synthesis of combinatorial libraries of N-acylated polyamines (NAPAs),8 suggesting that this route to PTAs might proceed efficiently enough to support the creation of high quality PTA-containing OBOC libraries. Indeed, we report here that this is the case. Diverse, enantiomerically pure PTA units are accessible through solid-phase reductive amination reactions using many different amino acids and aldehydes without the need for protecting groups.

Results and Discussion

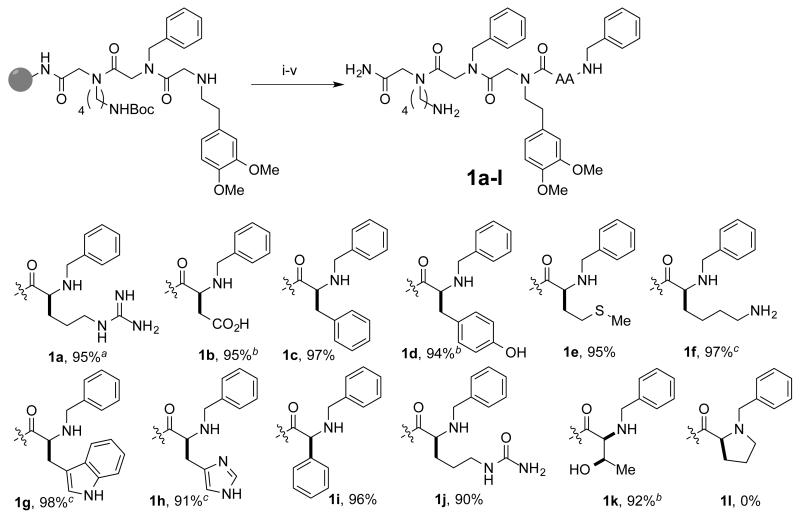

Twelve Fmoc-protected amino acids that are poor substrates for the synthesis of the corresponding chiral bromide5 were coupled onto a pre-synthesized linker on acid-cleavable polystyrene-RAM resin. After deprotection, each set of beads was incubated with benzaldehyde for an hour at room temperature, followed by reduction with sodium borohydride (Fig. 2). The compounds were then cleaved from the resin and analyzed by HPLC. Eleven of the molecules were monoalkylated efficiently to provide 1a-k in high purity. This group included phenylglycine (Phg) and a t-butyl sidechain-protected threonine substrate, showing that even molecules with bulky groups near the chiral center are good substrates. Tertiary amine products were not observed, showing that resin-bound secondary amines were not substrates under these conditions. Consistent with this observation, the reductive amination of proline to provide 1l failed. Only starting material was observed.

Figure 2.

Purities of the reductive amination products of amino acid-terminated oligomers with benzaldehyde and sodium borohydride. Purity was determined from the HPLCs of crude cleaved material. aPbf protected sidechain. bt-Butyl protected sidechain. cBoc-protected sidechain. (i) Fmoc-AA-OH, oxyma, DIC (4 eq. each) DMF, rt 40 m (ii) 20% piperidine DMF 10 m 2× (iii) 1M benzaldehyde DMF, rt 1 h (iv) xs NaBH4 DCM/MeOH, rt 30 m (v) 95/2.5/2.5 TFA/H2O/TIPS, rt 2.5 h.

To determine if any racemization occurs during this process, the four diasteromers of CH3CH2NH-Phg-Ala were synthesized on polystyrene-RAM resin using reductive amination with acetaldehyde and NaBH4 to add the ethyl group to the nitrogen of Phg. The pKa of the α proton of Phg is 14.99 and racemization of this residues is often encountered in peptide synthesis.10 The peptides were cleaved from the resin and analyzed by LC-MS without purification. The chromatograms (Fig. 3a) showed that the two trans and two cis stereoisomers separated well on the column, thus making it straightforward to observe the formation of the undesired diastereomer in all of the four chromatograms. There was no evidence of racemization.

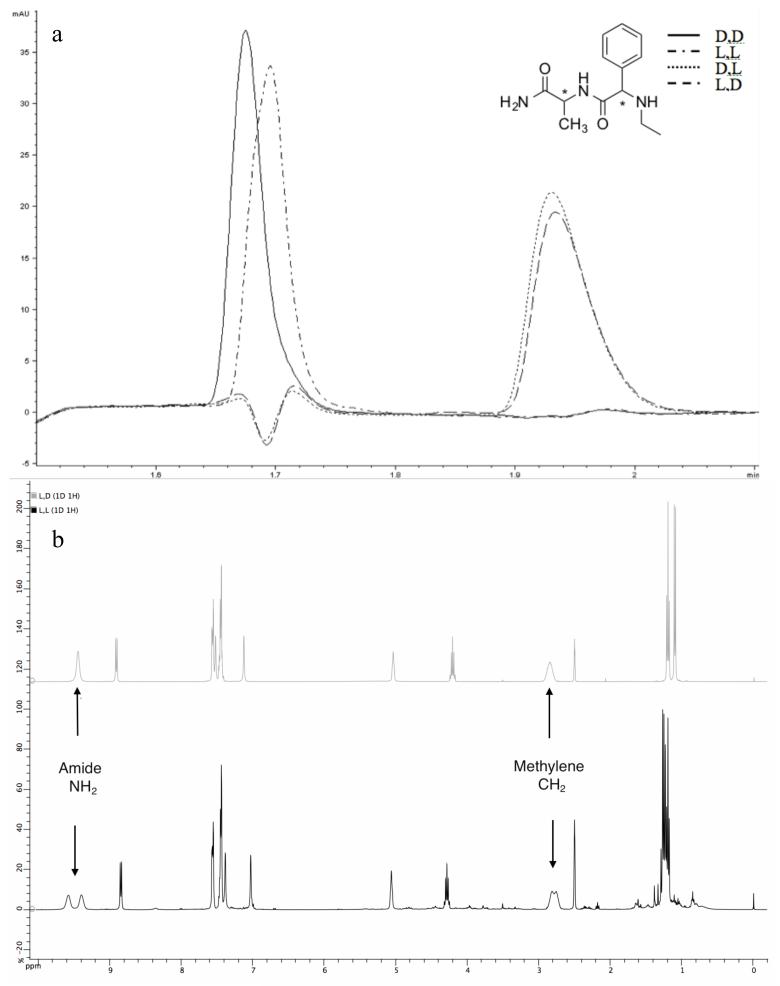

Figure 3.

No racemization is observed at the α-chiral center. a) LCMS overlay of four diastereomeric preparations of dipeptide Et-Phg-Ala-NH2 show cis (D,L and L,D) and trans (D,D and L,L) stereoisomers elute differentially. b) Crude NMR of two diastereomers (L,L in black, L,D in grey).

The crude 1H NMR spectra of the L,D and L,L products were also consistent with a stereochemically clean product. The spectrum of the L,L diastereomer preparation showed splitting of the C-terminal amide and N-ethyl methylene protons, suggesting a defined conformation, that were averaged in the L,D spectrum. Furthermore, there are multiple chemical shift differences that distinguish the diastereomers (Fig. 3b). Neither spectrum displayed detectable peaks indicative of formation of the undesired diastereomer through racemization of the Phg chiral center during reductive amination.

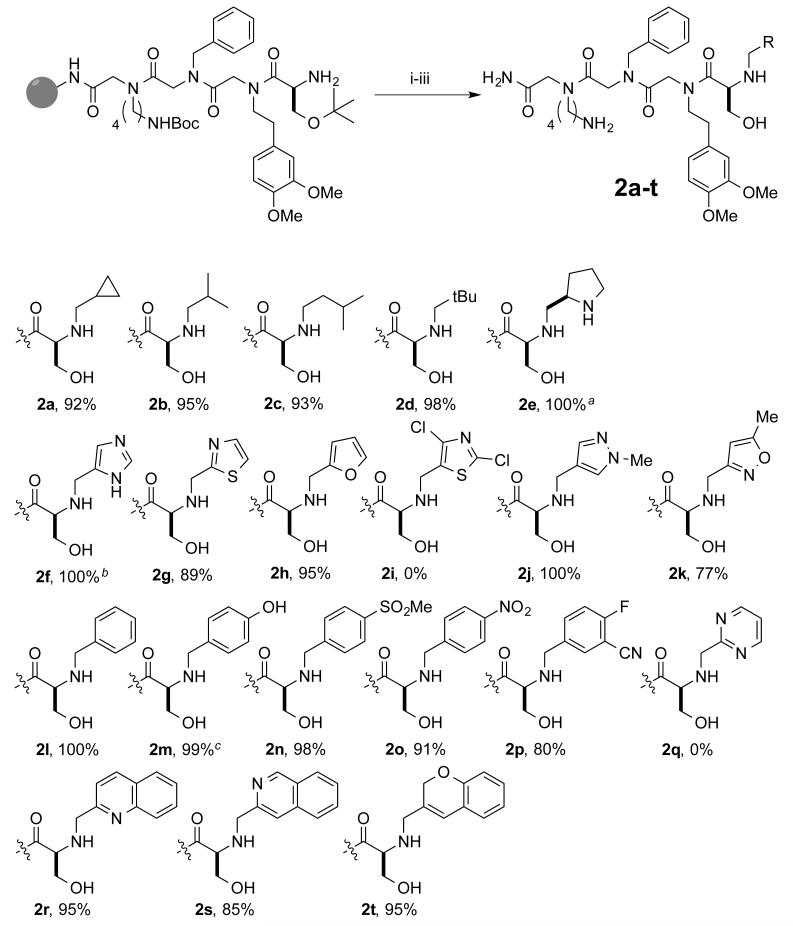

The scope of the reaction with respect to aldehyde substrate was surveyed by performing reductive amination on resin-bound molecules presenting a side chain-protected serine at the N-terminus (Figure 4). Aliphatic aldehydes provided products 2a-e nearly quantitatively, but results varied for aryl and heterocyclic aldehydes. The 1-Trityl-1H-imidazole, thiazole, and furan aldehydes gave products 2f-h in high purity, but the more hindered 2,4-dichloro-5-formylthiazole did not provide any of the desired product 2i. Conversely, methyl-substituted heterocyclic aldehydes provided 2j and 2k in high and modest purity, respectively. Various substituted benzaldehydes were successfully employed in the synthesis of 2l-p. 2-Pyrimidinecarboxaldehyde provided none of the desired product 2q; pyrrole and pyridine aldehydes reacted poorly as well (not shown). Given the lack of success with pyridine and pyrimidine, it was surprising that 2r-t were accessible from quinoline, isoqunioline, and chromene aldehydes. Taken together the data show that a diverse set of PTAs can be constructed via this chemistry, but that it is important to test the reactivity of any new aldehyde empirically.

Figure 4.

Aldehyde substrate scope for reductive amination of resin-bound primary amines. Purity determined by LCMS trace of crude cleaved material. aBoc protected sidechain. bTrt protected sidechain. ct-Butyl protected sidechain (i) 1M RCHO (10-15 eq.) DMF, rt 1 h (ii) xs NaBH4 DCM/MeOH, rt 30 m (iii) 95/2.5/2.5 TFA/H2O/TIPS, rt 2.5 h.

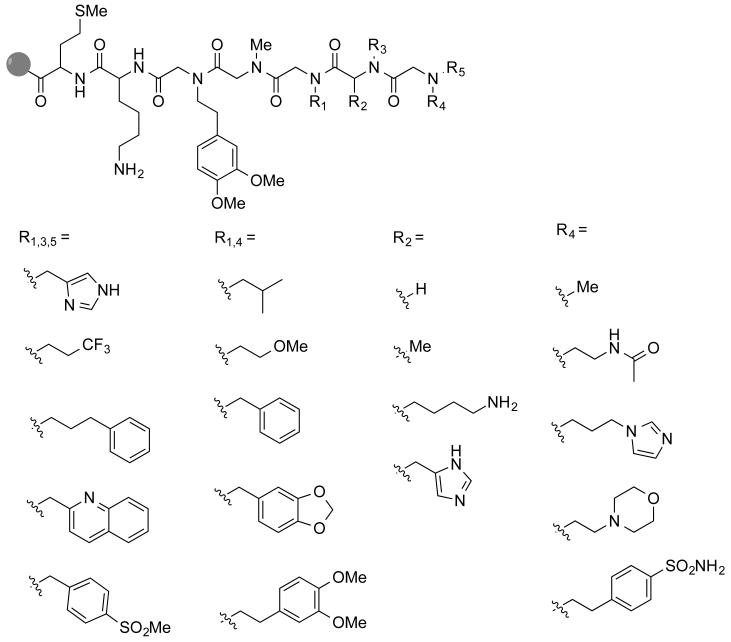

To test the utility of this reaction in the creation of large collections of PTA-containing molecules, the construction of the library shown in Fig. 5 was undertaken by solid-phase split and pool synthesis. Diversity at R3 derives from reductive amination, while nucleophilic displacement with primary amines provided diversity at R4. R1 diversity comes from both. The reductive amination on the N-terminus to provide R5 diversity was performed under acidic conditions as reported previously9,10, which allows for efficient reductive amination of secondary amines. Essentially, tertiary amines are generated via the in situ reductive amination at a lower pH (1% AcOH) and a milder reducing agent, sodium cyanoborohydride. Four amino acids used at the interior position provided side chain diversity for the central PTA element, two of which have polar side chains that were not accessible via the PTA haloacid submonomer method. The library was designed carefully, such that all fragments have unique masses, allowing unequivocal identification from the MS/MS spectra. The total diversity of this library is 10 × 4 × 5 × 10 × 5 = 10,000 compounds.

Figure 5.

Peptoid-PTA-peptoid(tertiary amine) library synthesized by combining haloacid submonomer synthesis with reductive amination.

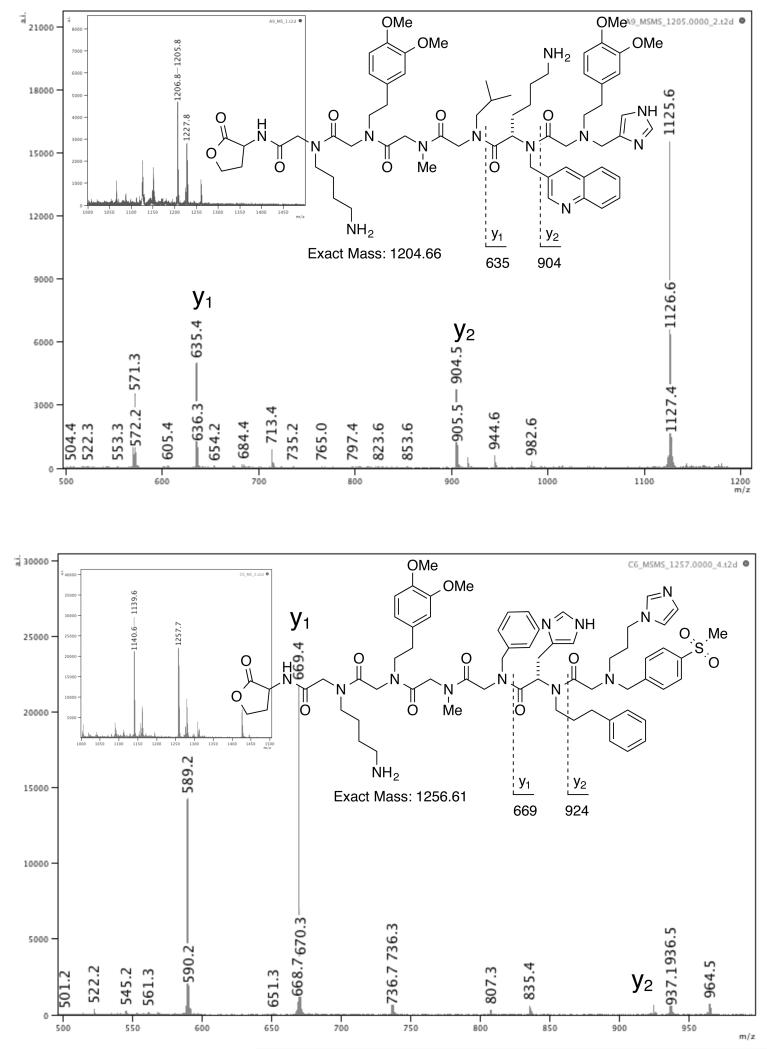

After synthesis and deprotection, sixty beads were selected and compounds were released from the resin with cyanogen bromide, which cleaves selectively at Met, in individual wells of a 96-well plate. The cleaved material from single beads was analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. The parental M+H ion detected from the initial experiment was then was subjected to tandem MS/MS to generate sequence-specific fragments for sequencing. The MS/MS of two representative compounds with their inlaid MS spectra are shown (Figure 6).11 From the sixty crude samples, fifty-eight gave M+H peaks in the mass range of the library members, and fifty-three of these were sequenced unequivocally from the MS/MS of the parental ion. The ability to unambiguously assign structures to 91% of the observed parent ions reflects the effectiveness of the methods established in this work, and proves its suitability for use in the synthesis of high quality OBOC combinatorial libraries.

Figure 6.

Sequencing of library compounds from MS/MS data obtained from crude material from single beads. MS experiment for identification of parental M+H ion is inlaid in the top left corner of each spectrum.

In summary, the reductive amination method has been optimized for selective monoalkylation of primary amine substrates on the solid phase, providing PTA units that were inaccessible using our previously reported method. The reaction is general for all primary amine substrates tested, does not lead to racemization of adjacent chiral centers, and utilizes a variety of aliphatic, aromatic, and heterocyclic aldehyde reagents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (1 DP3 DK0944309).

Footnotes

Associated Content

Supporting Information. Detailed experimental protocols and data on compound characterization are provided. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at (placeholder).

Notes: the authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.(a) Lam KS, Salmon SE, Hersh EM, Hruby VJ, Kazmierski WM, Knapp RJ. A new type of synthetic peptide library for identifying ligand-binding activity. Nature. 1991;354:82–84. doi: 10.1038/354082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Houghten RA, Pinilla C, Blondelle SE, Appel JR, Dooley CT, Cuervo JH. Generation and use of synthetic peptide combinatorial libraries for basic research and drug discovery. Nature. 1991;354:84–86. doi: 10.1038/354084a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Figliozzi GM, Goldsmith R, Ng SC, Banville SC, Zuckermann RN. Synthesis of N-substituted glycine peptoid libraries. Methods Enzymol. 1996;267:437–447. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)67027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Alluri PG, Reddy MM, Bachhawat-Sikder K, Olivos HJ, Kodadek T. Isolation of protein ligands from large peptoid libraries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:13995–14004. doi: 10.1021/ja036417x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Doedens L, Opperer F, Cai M, Beck JG, Dedek M, Palmer E, Hruby VJ, Kessler H. Multiple N-methylation of MT-II backbone amide bonds leads to melanocortin receptor subtype hMC1R selectivity: pharmacological and conformational studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8115–8128. doi: 10.1021/ja101428m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ovadia O, Greenberg S, Chatterjee J, Laufer B, Opperer F, Kessler H, Gilon C, Hoffman A. The effect of multiple N-methylation on intestinal permeability of cyclic hexapeptides. Mol Pharm. 2011;8:479–487. doi: 10.1021/mp1003306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kessler H, Chatterjee J, Doedens L, Operrer F, Biron E, Hoyer D, Schmid H, Gilon C, Hruby VJ, Mierkes DF. New perspective in peptide chemistry by N-alkylation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2009;611:229–231. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73657-0_106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rezai T, Yu B, Millhauser GL, Jacobson MP, Lokey RS. Testing the conformational hypothesis of passive membrane permeability using synthetic cyclic peptide diastereomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2510–2511. doi: 10.1021/ja0563455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang S, Prabpai S, Kongsaeree P, Arvidsson PI. Poly-N-methylated alpha-peptides: synthesis and X-ray structure determination of beta-strand forming foldamers. Chem. Commun. 2006;(5):497–499. doi: 10.1039/b513277k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demmer O, Dijkgraaf I, Schottelius M, Wester HJ, Kessler H. Introduction of functional groups into peptides via N-alkylation. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2015–2018. doi: 10.1021/ol800654n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao Y, Kodadek T. Synthesis and screening of stereochemically diverse combinatorial libraries of peptide tertiary amides. Chem. & Biol. 2013;20:360–369. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuckermann RN, Kerr JM, Kent SBH, Moos WH. Efficient method for the preparation of peptoids (oligo(N-substituted glycines)) by sub-monomer solid-phase synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:10646–10647. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Izumiya N, Nagamatsu A. Walden invesrion of amino acids. VI. The synthesis of D-Surinamine (N-methyl-D-tyrosine) Bull. Chem. Soc. Japan. 1952;25:265–267. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tanasova M, TYang Q, Olmsted CC, Vasileiou C, Li X, Anyika M, Borhan B. An unusual conformation of alpha-haloamides due to cooperative binding with zincated porphyrins. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009;(25):4242–4253. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Hayashi R, Wang D, Hara T, Iera JA, Durell SR, Appella DH. N-acylpolyamine inhibitors of HDM2 and HDMX binding to p53. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:7884–7893. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Iera JA, Jenkins LM, Kajiyama H, Kopp JB, Appella DH. Solid-phase synthesis and screening of N-acylated polyamine (NAPA) combinatorial libraries for protein binding. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:6500–6503. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stroud ED, Fife DJ, Smith GG. A method for the determination of the pKa of the alpha hydrogen in amino acids using racemization and exchange studies. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:5368–5369. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elsawy MA, Hewage C, Walker B. Racemisation of N-Fmoc phenylglycine under mild microwave-SPPS and conventional stepwise SPPS conditions: attempts to develop strategies for overcoming this. J. Pept. Sci. 2012;18:302–11. doi: 10.1002/psc.2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaisar T, Urban J. Gas phase fragmentation of protonated mono-N-methylated peptides. Analogy with solution phase acid-catalyzed hydrolysis. J. Mass Spectrom. 1998;33:505–524. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.