Summary

Background

Both sarcoidosis and its treatment may worsen health related quality of life (HRQoL). We performed a propensity analysis of sarcoidosis-specific HRQoL patient reported outcome measures (PRO) to disentangle the effects of sarcoidosis and corticosteroid therapy on HRQoL in sarcoidosis outpatients.

Methods

Consecutive outpatient sarcoidosis patients were administered modules from two sarcoidosis-specific HRQoL PROs: the Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire (SHQ) and the Sarcoidosis Assessment Tool (SAT). Patients were divided into those that received ≤500 mg of prednisone (PRED-LOW) versus >500 mg of prednisone (PRED-HIGH) over the previous year. SAT and SHQ scores were initially compared in the two corticosteroid groups. Then a multivariate analysis was performed using a propensity score analysis adjusted for race, age, gender and the severity of illness.

Results

In the unadjusted analysis, the PRED-HIGH group demonstrated the following worse HRQoL scores compared to the LOW-PRED group: SHQ Daily (p = 0.02), SAT satisfaction (p = 0.03), SAT daily activities (p = 0.03). In the propensity analysis, the following domains demonstrated worse HRQoL in the PRED-HIGH group than the PRED-LOW group: SAT fatigue (p < 0.0001), SAT daily activities (p = 0.03), SAT satisfaction (p = 0.03). All these differences exceeded the established minimum important difference for these SAT domains. The SHQ Physical score appeared to demonstrate a borderline improved HRQoL in the PRED-HIGH versus the PRED-LOW group (p = 0.05).). In a post-hoc exploratory analysis, the presence of cardiac sarcoidosis may have explained the quality of life differences between the two corticosteroid groups.

Conclusions

Our cohort of sarcoidosis clinic patients who received ≤500 mg of prednisone in the previous year had an improved HRQoL compared to patients receiving >500 mg on the basis of two sarcoidosis-specific PROs after adjusting for severity of illness. These data support the need to measure HRQoL in sarcoidosis trials, and suggest that the search should continue for effective alternative medications to corticosteroids.

Keywords: Sarcoidosis, Quality of life, Corticosteroids, Patient reported outcomes

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a disease with varying presentations, severity, and prognosis [1,2]. In a sizable percentage of sarcoidosis patients, the disease may cause minimal to no symptoms and no significant organ involvement [3,4]. Because the standard treatment of sarcoidosis is corticosteroids [5], the toxicities of these medications may more than offset their benefit in sarcoidosis patients with negligible to mild disease [5]. Therefore, the decision to use corticosteroids for the treatment of sarcoidosis must weigh the benefits of therapy against the potential complications of such treatment.

A previous study of sarcoidosis patients, those who were prescribed corticosteroids were found to have lower health related quality of life (HRQoL) scores than those not receiving corticosteroids [6]. However, it could be argued that patients receiving corticosteroids had more severe sarcoidosis, and that the cause of the poorer HRQoL may have been because of the disease itself rather than the use of corticosteroids. We conducted a trial examining patient reported outcome (PRO) HRQoL measures in patients who were receiving variable corticosteroid dosages. We attempted to adjust for the severity of sarcoidosis in this cohort by using propensity scores in an attempt to disentangle the effects of corticosteroids and sarcoidosis severity upon HRQoL.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Albany Medical College. We enrolled consecutive patients into this trial who met the following criteria: a) met diagnostic criteria for sarcoidosis [7]; b) were willing to sign the study consent form; c) were able to converse and read English; d) were greater than 18 years old; and e) had been diagnosed with sarcoidosis at least 1 year prior to enrollment. Subjects could be enrolled if they had pulmonary and/or extrapulmonary sarcoidosis. Subjects were excluded if they were receiving corticosteroids for a medical condition other than sarcoidosis or, if in the opinion of the investigator, they had an alternative medical condition that was severely impairing their HRQoL.

After signing an informed consent form, a study investigator questioned each subject concerning their corticosteroid use over the previous year. The investigator accessed to the subject's medical record to assist in this determination. Through this process, an estimate of the total dose of prednisone equivalent taken by the patient over the last year was made. All subjects were then asked to complete the following PROs: a) the Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire (SHQ) [8], b) the following Sarcoidosis Assessment Tool (SAT) modules [9,10]: daily activities, satisfaction, pain, fatigue, lung (if the subject had lung involvement by National Institutes of Health A Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis - ACCESS criteria [11]), skin (if the subject had skin involvement by ACCESS criteria [11]). All subjects also had the following clinical data recorded: age, sex, race, height, weight, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, date of onset of symptoms of sarcoidosis as estimated by a study investigator (MAJ), date of diagnosis of sarcoidosis as estimated by a study investigator (MAJ), the number of organs involved and specific organs involved by ACCESS criteria [11], the presence of absence of lupus pernio, the date and type of the most recent chest imaging study prior to study entry as well as the Scadding stage [12] on that imaging study, the date of the most recent spirometry testing prior to study entry as well as the forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) measured on that spirometry study, an inventory of all non-corticosteroid anti-sarcoidosis medications used in the previous 1 year.

Statistical analysis

The patients were divided into 2 groups in terms of corticosteroid use over the previous; those who received ≤500 mg of prednisone equivalent over the previous year (PRED-LOW group) and those who received >500 mg equivalent over the previous year (PRED-HIGH group). We first conducted a bivariate analyses to compare study sample characteristics between the PRED-LOW and PRED-HIGH groups. Next we compared SAT and SHQ scores (unadjusted) by the two groups. We then conducted multivariate analyses, that aimed to adjust for the differential distributions in the background covariates. As the data under consideration arose from an observational study design and to achieve a pseudo-randomization, propensity score (PS) analysis was used to reduce potential bias and address confounding when comparing PRED-HIGH versus PRED-LOW groups. PS analysis uses matched cases where the matched cases have similar background covariates. Matching was done on age, sex, race, number of organs involved (one organ versus more than one organ), the presence or absence of a stage IV chest radiograph, the presence or absence of lupus pernio, forced vital capacity (FVC) % predicted, and the need for additional anti-sarcoidosis drugs. Logistic regression was used to estimate the propensity scores. Computations were conducted using MatchIt package for R statistical software which is a freeware for statistical computation and graphics [13].

Results

Table 1 shows the demographics and clinical characteristics of the 114 subjects who were enrolled in this study. There were some differences between the study groups. Obviously, on the basis of the study design, the PRED-HIGH group had a higher mean total prednisone dose the PRED-LOW group. The PRED-HIGH group also had a significantly lower mean FVC (p = 0.005), significantly greater use of anti-sarcoidosis drugs other than corticosteroids (p < 0.001), and a tendency toward more organs being involved than the PRED-LOW group (p = 0.051). Finally, the PRED-HIGH group had a significantly higher percentage of African-Americans (p = 0.03) than the PRD-LOW group. Previous data have demonstrated that phenotypic expression of sarcoidosis is more severe in African Americans than Caucasians [14,15].

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and group differences.

| Clinical characteristic | Total cohort mean (SD) median (IQR) | Group <=500/yr prednisone (n = 62) PRED- LOW | Group > 500/yr prednisone (n = 52) PRED-HIGH | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prednisone | 1817.35 (2687.82) | 32.09 (102.67) | 3944.43 (2739.85) | <0.001 |

| Dose (mg in the previous year) | 230 (3311.25) | 0 (0) | 3491 (3168) | |

| Age | 51.82 (15.75) | 52.58 (11.08) | 50.9 (12.23) | 0.45 |

| 52 (11.59) | 53 (13.75) | 52 (18.75) | ||

| Sex (ratio of males) | 52.63% | 54.83% | 50% | 0.74 |

| Race (ratio of African Americans) | 19.29% | 11.29% | 28.85% | 0.03 |

| # organs involved | 2.44 (1.21) | 2 (1.19) | 2.44 (1.19) | 0.051 |

| 2 (2) | 2 (1) | 2 (2) | ||

| % lung involvement | 95.6% | 95.16% | 96.15 | 0.99 |

| Days since first symptom attributed to sarcoidosis | 2820.34 (2652.7) | 3018 (3000.28) | 2585.21 (2172.63) | 0.375 |

| 1652.5 (3099) | 1656 (2656) | 1652 (2620) | ||

| Days since diagnosis of sarcoidosis | 2650.15 (2765.34) | 2900.84 (3200.52) | 2351.25 (2127.63) | 0.27 |

| 1411 (3104.51) | 1410 (3088) | 1426 (2620) | ||

| FVC (% predicted) | 80.86 (19.98) | 85.39 (18.75) | 75.54 (17.99) | 0.005 |

| 83 (23) | 88 (18) | 75 (21.25) | ||

| Stage IV chest radiograph | 14.9% | 19.2% | 11.2% | 0.37 |

| Additional anti-sarcoidosis drugs (% of cohort) | 27.1% | 9.6% | 51.9% | <0.001 |

FVC: forced vital capacity: First rows show means and standard deviations, second rows show median and inter-quartile range (where applicable).

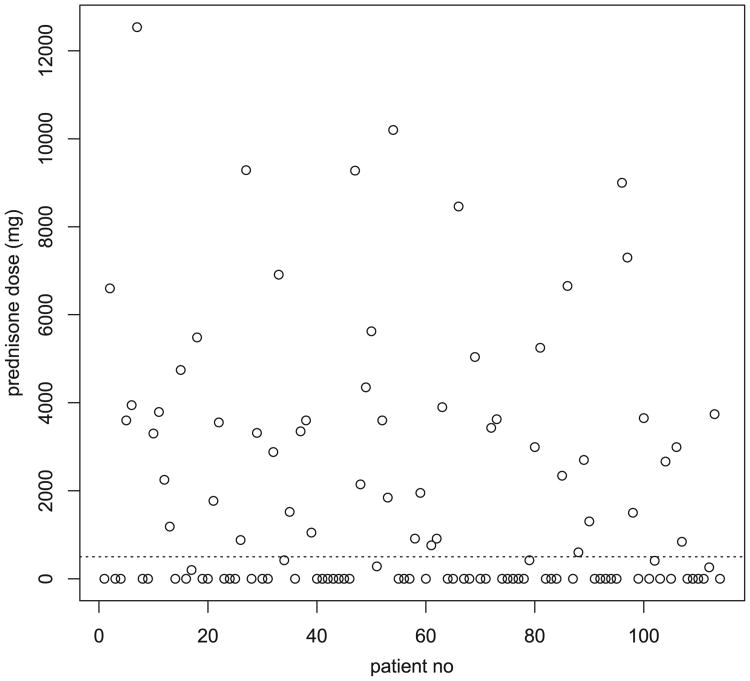

Fig. 1 shows the distribution of the estimated total prednisone equivalent over the previous year in the entire cohort (place a dashed line at dose = 500 mg). It is clear that there was a fairly distinct separation in the yearly prednisone dose of the LOW-PRED and HIGH-PRED groups.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the cumulative yearly prednisone equivalent dose (mg) in the previous year of the entire study cohort. The dashed line represents the cut-off (≤500 mg versus >500 mg) that was the cut-off between the PRED-LOW and PRED-HIGH groups.

Table 2 shows the comparison of the SAT and SHQ scores of the two groups. Means for the SHQ Daily score (p-value = 0.02), SAT Satisfaction score (p-value = 0.03), and SAT Daily Activities score (p-value = 0.03) were significantly different between the two groups, with worse HRQoL scores in the PRED-HIGH group compared to the PRED-LOW group. All other SAT and SHQ domains were not significantly different.

Table 2.

Unadjusted comparison of mean scores between prednisone does groups (<500 mg/year versus >500 mg/year)*.

| PRO module | >500 mg prednisone/year | <=500 mg prednisone/year | Minimum important difference** | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHQ total [+] | 4.14 (0.33) | 4.18 (0.37) | N/A | 0.61 |

| SHQ physical [+] | 4.14 (0.70) | 4.01 (0.70) | N/A | 0.11 |

| SHQ daily [+] | 4.42 (0.46) | 4.73 (0.41) | N/A | 0.02 |

| SHQ emotional [+] | 3.87 (0.48) | 3.79 (0.51) | N/A | 0.41 |

| SAT pain [–] | 54.5 (10.0) | 51.76 (10.3) | 3.2 | 0.15 |

| SAT fatigue [–] | 55.5 (11.4) | 52.4 (10.5) | 3.1 | 0.13 |

| SAT satisfaction [+] | 46.5 (10.7) | 50.9 (11.4) | 3.0 | 0.03 |

| SAT daily activities [+] | 42.1 (7.5) | 45.6 (9.8) | 3.0 | 0.03 |

| SAT lung [–] | 45.73 (9.1) | 43.0 (9.6) | 2.7 | 0.13 |

SHQ: Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire; SAT: sarcoidosis assessment tool;

: standard deviations given in the parentheses;

previously established (REF# 16);

[+]: higher score indicates better quality of life; [–]: lower score indicates better quality of life; N/A: not applicable as minimum important difference has not been determined for the Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire.

In Table 3 are shown the results of the propensity score analysis performed to eliminate the possibility that differences seen above between the PRED-LOW and PRED-HIGH groups were due to differences in characteristics associated with sarcoidosis severity. These characteristics were listed in the methods section. After the propensity adjustment, the following SAT and SHQ domains demonstrated worse HRQoL in the PRED-HIGH group than the PRED-LOW group: SAT Fatigue score (p < 0.0001), SAT Daily Activities score (p = 0.03), and SAT Satisfaction score (p = 0.03). The SHQ Physical score appeared to demonstrate a borderline improved HRQoL in the PRED-HIGH versus the PRED-LOW group (p = 0.05). All other SAT and SHQ domains were not significantly different after this propensity adjustment. Table 3 also shows the established minimally importance difference (MID) estimates for the SAT modules that were used in this study [16]. In all instances where the SAT domains showed statistically significant worse scores in the PRED-HIGH group than the PRED-LOW group, these differences exceeded the domain's MID, suggesting that these differences were not only statistically significant but also clinically significant. No determination of the MID for each SHQ module has presently been performed.

Table 3.

Mean scores after propensity score matching by the two corticosteroid dose groups*.

| PRO module | >500 mg prednisone/year | <=500 mg prednisone/year | Minimum important difference** | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHQ total [+] | 4.18 (0.37) | 4.17 (0.33) | N/A | 0.88 |

| SHQ physical [+] | 4.73 (0.70) | 4.46 (0.69) | N/A | 0.05 |

| SHQ daily [+] | 4.01 (0.41) | 4.17 (0.48) | N/A | 0.08 |

| SHQ emotional [+] | 3.79 (0.51) | 3.81 (0.45) | N/A | 0.35 |

| SAT pain [–] | 54.5 (10.0) | 51.8 (10.1) | 3.2 | 0.18 |

| SAT fatigue [–] | 54.8 (114) | 48.9 (10.6) | 3.1 | <0.0001 |

| SAT satisfaction [+] | 46.5 (10.7) | 51.5 (11.8) | 3.0 | 0.03 |

| SAT daily activities [+] | 42.1 (7.5) | 45.8 (9.5) | 3.0 | 0.03 |

| SAT lung [–] | 45.7 (9.1) | 42.7 (9.5) | 2.7 | 0.12 |

SHQ: Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire; SAT: sarcoidosis assessment tool;

: standard deviations given in the parentheses;

previously established (REF# 16);

[+]: higher score indicates better quality of life; [–]: lower score indicates better quality of life; N/A: not applicable as minimum important difference has not been determined for the Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire.

After these analyses were completed, we noticed that specific organ involvement in the PRED-HIGH and PRED-LOW groups were similar except for cardiac sarcoidosis (percent with cardiac sarcoidosis: PRED-LOW 1/62 = 1.6%; PRED-HIGH: 11/52 = 21.1%, p value = 0.002). When we added the presence or absence of cardiac sarcoidosis to our propensity analysis, the differences in the quality of life measures disappeared.

Discussion

In this study of patients cared for in a sarcoidosis clinic, we demonstrated that even when adjusting for the severity of illness using a propensity adjustment, the use of greater than 500 mg of prednisone during the previous year was associated with worse HRQoL measures than the use of lower doses of corticosteroids. Previous studies have demonstrated that corticosteroid use was associated with worse HRQoL in sarcoidosis patients [6]. However, it is likely that sarcoidosis patients requiring higher doses of corticosteroids have more severe disease, and the severity of the disease rather than corticosteroid use might have explained these findings. To distinguish whether corticosteroids or disease severity was responsible for worse HRQoL in such patients, we performed a propensity analysis to adjust for disease severity. Our results suggest that the severity of sarcoidosis cannot adequately explain our results, and suggest that the corticosteroids may be responsible for a large proportion of the HRQoL impairment in our cohort. The PRED-HIGH group had a statistically greater percentage of African Americans, lower FVC, a greater percentage of additional anti-sarcoidosis medication use and a trend toward more organ involvement than the PRED-LOW group. However, all of these were adjusted for in the propensity analysis and, therefore, could not explain the worse HRQoL results that were observed in the PRED-HIGH group.

This study has important implications concerning the approach to the treatment of sarcoidosis. Corticosteroids are deemed the drug of choice for the treatment of sarcoidosis [5,17,18], mostly on the basis of their efficacy [19] and speed of action [20]. It is assumed that if the disease can be controlled, HRQoL will be improved. However, a large proportion of sarcoidosis patients have chronic disease that requires continuous anti-sarcoidosis therapy to be controlled [4]. Many of the toxicities of corticosteroids are cumulative side effects that relate to chronic use, such as weight gain, osteoporosis, cataracts, skin fragility. Our data suggests that outcome assessment of sarcoidosis should not only take into account objective measures of disease improvement such as spirometry, eye examinations, and skin lesions but also the potential detrimental effects of corticosteroids. These data suggest that alternative therapies to corticosteroids may have an important role in the management of sarcoidosis, possibly including the initial management, if they have a superior side effect profile.

This study has several potential limitations that may impact the significance of our findings. First, the decision to assess corticosteroid use by two dichotomous variables (those receiving ≤500 mg of prednisone equivalent versus >500 mg in the previous year) was arbitrary. This was an a priori decision that we made with a great deal of thought and consultation. We considered using the estimated to lifetime dose, dose at the time of study entry, or average daily dose over a specified time period other than one year. We believed that our decision to perform our analysis on these two groups was rational, because of the aforementioned statement that most corticosteroid toxicity results from cumulative use. We believed that using corticosteroid dose information more than one year old might make the estimate more inaccurate. In addition, many corticosteroid side effects are reversible after discontinuation [19,21]. Therefore, corticosteroid use more than one year previous assessment may have limited impact on HRQoL. We further believed that a total prednisone equivalent dose of >500 in the previous year would be a good threshold for the development of relevant corticosteroid side effects. Finally, Fig. 1 suggests that there is a robust separation in the yearly prednisone dose between our two selected groups.

Second, although the SHQ has been validated as a sarcoidosis-specific HRQoL PRO, a clear minimum important difference (MID) has not been established for this instrument. Therefore, we cannot ascertain the clinical importance of reduction in HRQoL in the higher dose corticosteroid group in terms of the SHQ findings. In addition, SHQ Physical score demonstrated a borderline improved HRQoL in the PRED-HIGH versus the PRED-LOW group. Not only is the significance of this finding tempered by the absence of a MID for the SHQ, but the Physical domain of the SHQ was found to be higher in those receiving corticosteroids than in those who did not in the original validation of this instrument [8].

Finally, it could be argued that our propensity adjustments were incomplete in that there may have been additional covariates that affect disease severity that we did not analyze. We believe that the covariates that we selected were clinically reasonable and did adequately adjust these data to disclose differences between the two groups. However, in a post-hoc analysis, the presence of cardiac sarcoidosis did explain the difference in quality of life measures between the two corticosteroid groups. Such a post-hoc analysis needs to be interpreted with caution as it was exploratory. If this finding is indeed real, it is possible that the presence or absence of cardiac sarcoidosis supersedes the corticosteroid group in impacting on the patient's health related quality of life.

In conclusion, we found that our cohort of sarcoidosis clinic patients who received ≤500 mg of prednisone equivalent in the previous year had an improved HRQoL compared to patients receiving >500 mg in the previous year of the basis domains of two sarcoidosis-specific PROs. This study highlights the need to measure HRQoL in sarcoidosis intervention trials and suggests that the search should continue for effective alternative medications to corticosteroids.

Footnotes

Contribution of authors: MAJ is the guarantor of the paper, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article. All authors were involved in the study design. HC, AL, and KL performed the data collection and data entry. RY performed the statistical analyses. All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript, and no additional individuals were involved.

Conflict of interest statement: MAJ has the following potential conflicts of interest: consultant for Celgene, Questcor, Novartis. However, MAJ does not believe that these potential conflicts of interest have any bearing on this particular publication. HC, AL, KL and RY have no conflicts of interest to declare. The authors do not believe that they will receive any financial gain by the publication of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16:149–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Judson MA. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and approach to treatment. Am J Med Sci. 2008;335:26–33. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31815d8276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baughman RP, Judson MA, Teirstein A, et al. Presenting characteristics as predictors of duration of treatment in sarcoidosis. Qjm. 2006;99:307–15. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baughman RP, Nagai S, Balter M, et al. Defining the clinical outcome status (COS) in sarcoidosis: results of WASOG task force. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2011;28:56–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beegle SH, Barba K, Gobunsuy R, et al. Current and emerging pharmacological treatments for sarcoidosis: a review. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2013;7:325–38. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S31064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox CE, Donohue JF, Brown CD, et al. Health-related quality of life of persons with sarcoidosis. Chest. 2004;125:997–1004. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.3.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Judson MA. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:415–27. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox CE, Donohue JF, Brown CD, et al. The Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire: a new measure of health-related quality of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:323–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200211-1343OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Victorson DE, Cella D, Grund H, et al. A conceptual model of health-related quality of life in sarcoidosis. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1301–13. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0438-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Victorson DE, Choi S, Judson MA, et al. Development and testing of item response theory-based item banks and short forms for eye, skin and lung problems in sarcoidosis. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1301–13. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Judson MA, Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, et al. Defining organ involvement in sarcoidosis: the ACCESS proposed instrument. ACCESS Research Group. A Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16:75–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scadding JG. Prognosis of intrathoracic sarcoidosis in England. A review of 136 cases after five years' observation. Br Med J. 1961;2:1165–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5261.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho DE, Imai K, King G, et al. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J Stat Softw. 2011;42:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westney GE, Judson MA. Racial and ethnic disparities in sarcoidosis: from genetics to socioeconomics. Clin Chest Med. 2006;27:453–62. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Judson MA, Boan AD, Lackland DT. The clinical course of sarcoidosis: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment in a large white and black cohort in the United States. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2012;29:119–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Judson MA, Mack M, Beaumont JL, et al. Validation and important differences for the sarcoidosis assessment tool: a new patient reported outcome measure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1785OC. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Judson MA. An approach to the treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis with corticosteroids: the six phases of treatment. Chest. 1999;115:1158–65. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.4.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baughman RP, Nunes H, Sweiss NJ, et al. Established and experimental medical therapy of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:1424–38. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00060612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson GJ, Prescott RJ, Muers MF, et al. British Thoracic Society Sarcoidosis study: effects of long term corticosteroid treatment. Thorax. 1996;51:238–47. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.3.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKinzie BP, Bullington WM, Mazur JE, et al. Efficacy of short-course, low-dose corticosteroid therapy for acute pulmonary sarcoidosis exacerbations. Am J Med Sci. 2010;339:1–4. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181b97635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johns CJ, Michele TM. The clinical management of sarcoidosis. A 50-year experience at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Med Baltim. 1999;78:65–111. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]