Summary

Inflammation promotes regeneration of injured tissues through poorly understood mechanisms, some of which involve interleukin (IL)-6 family members whose expression is elevated in many diseases, including inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and colorectal cancer (CRC). We show that gp130, a co-receptor for IL-6 cytokines, triggers activation of YAP and Notch, transcriptional regulators that control tissue growth and regeneration, independently of the classic gp130 effector STAT3. Through YAP and Notch, intestinal gp130 signaling stimulates epithelial cell proliferation, causes aberrant differentiation and confers resistance to mucosal erosion. gp130 associates with the related tyrosine kinases Src and Yes, which are activated upon receptor engagement to phosphorylate YAP and induce its stabilization and nuclear translocation. This signaling module is strongly activated upon mucosal injury to promote healing and maintain barrier function.

Introduction

Inflammation is a complex biological response triggered upon tissue damage or microbial invasion. In addition to host defense, self-limiting inflammation triggers regeneration and repair1,2. By preventing further microbial translocation, healing promotes resolution of inflammation. Whereas host defense and immunity have been extensively studied, the mechanisms through which inflammation stimulates regenerative responses remain obscure. By-and-large, numerous pathways involved in tissue growth, patterning and differentiation are re-deployed during regeneration3, including the hedgehog (Hh)-Gli, Wnt-β-catenin, Notch and Hippo-YAP pathways3,4. Upon tissue injury, myeloid cells, including macrophages, produce inflammatory cytokines and growth factors5. But signaling mechanisms that link typical inflammatory cytokines to pivotal transcriptional regulators of tissue growth, repair and regeneration remain to be charted.

Regenerative responses are particularly important in the mammalian gastrointestinal (GI) tract, a tissue subject to frequent erosion and renewal. Unrepaired mucosal injury disrupts the epithelial barrier that prevents translocation of intestinal microbiota, resulting in acute inflammation6. Persistent failure to repair such damage can result in IBD, including ulcerative colitis (UC), which entails severe mucosal erosion, and Crohn’s disease (CD), in which aberrant growth can cause fistula formation6. Mucosal healing is a key treatment goal in IBD that predicts sustained remission and resection-free survival6. It is therefore important to understand how mucosal healing is regulated. After injury, intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) surrounding the lesion lose columnar polarity and rapidly initiate wound healing. “Epithelial restitution” starts within minutes after injury and is considered crucial for temporary sealing of the disrupted surface. Subsequent stem cell activation, proliferation and differentiation increase the cell pool available for healing. These processes are tightly regulated to prevent uncontrolled proliferation and tumorigenesis, and rely on coordinated and balanced function of IECs, secretory cells, intestinal stem cells and the immune system6.

IL-6 is a prototypical pro-inflammatory cytokine, whose family includes IL-11, IL-27, IL-31, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), oncostatin M, ciliary neurotrophic factor, and cardiotrophin-1, all of which influence cell proliferation, survival, migration, invasion, angiogenesis and inflammation7. Most family members activate the JAK-STAT3, SHP-2-Ras-ERK and PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 pathways via the common co-receptor gp1307,8. Amongst these pathways, STAT3 is the major and most extensively studied effector that links inflammation to cell proliferation, survival and cancer, being subject to feedback regulation by suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3)8,9. IL-6, soluble IL-6Rα, and IL-11 are highly elevated in IBD and GI cancers10,11. However, activating STAT3 mutations are rare12, and tumoral STAT3 is mainly activated by cytokines and/or decreased SOCS3 expression13. Nonetheless, gain-of-function mutations affecting gp130-STAT3 signaling were identified in benign human inflammatory hepatocellular adenomas (IHCA)12,14.

IL-6 promotes IEC proliferation and regeneration and IL-6-deficient mice, which do not exhibit developmental abnormalities, are highly sensitive to experimental colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium salt (DSS)13. Correspondingly, IL-6 blockade in humans can result in intestinal perforation15. In addition to STAT3 in IEC13, mucosal regeneration after DSS challenge requires concomitant activation of Yes-associated protein (YAP)16 and Notch17. YAP is a key transcriptional co-activator of tissue growth which is normally kept inactive in the cytoplasm through serine phosphorylation by the Hippo effector kinase LATS18. YAP is activated either upon inhibition of Hippo signaling or upon tyrosine phosphorylation by the Src family kinase (SFK) Yes19. Notch is activated by ligands, such as Jagged (Jag)-1, 2, Delta-like (DLL) 1, 3 and 4, which trigger Notch cleavage by γ-secretase, resulting in nuclear translocation of its intracellular domain (NICD) which associates with CBF1/RBPkJ to activate target gene transcription20. The mechanisms whereby mucosal injury activates YAP and Notch remain elusive.

We show that independently of STAT3, gp130 also activates YAP and then Notch through direct association with SFKs. This pathway is engaged upon mucosal injury in mice and is essential for inflammation-induced epithelial regeneration. It is also activated in human IBD.

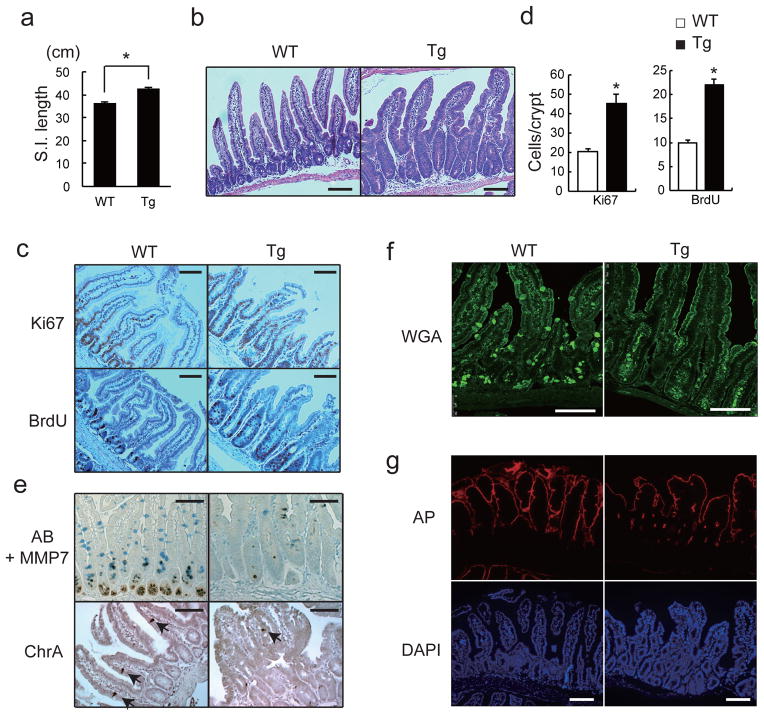

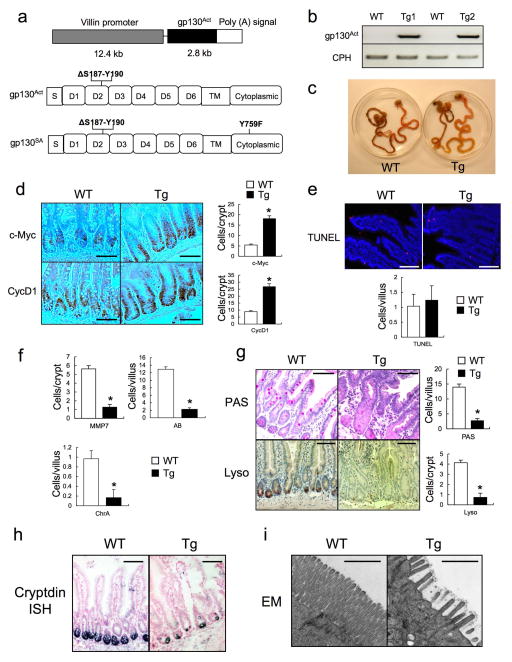

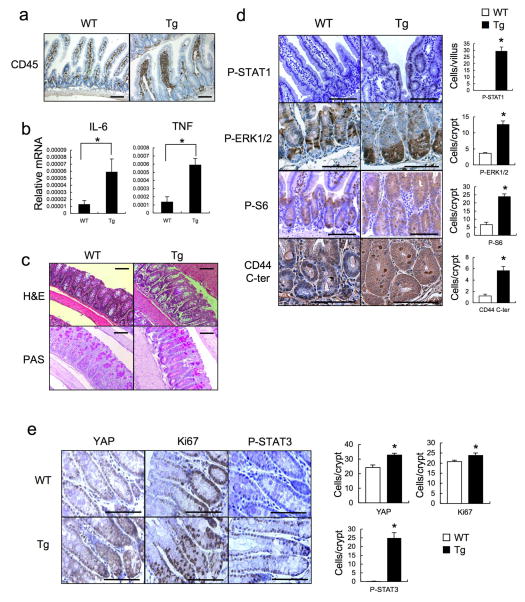

Persistent gp130 activation causes aberrant IEC proliferation and differentiation

We generated villin-gp130Act transgenic (Tg) mice that express activated gp130Act, an in-frame S187-Y190 deletion found in IHCA14, from the IEC-specific villin promoter (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). Hemizygous villin-gp130Act mice were born in Mendelian ratios, but their intestines were larger and longer than wild-type (WT) counterparts (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1c). The Tg intestinal mucosa was hyperproliferative with deeper crypts than WT (Fig. 1b–d; Extended Data Fig. 1d), without a difference in apoptosis (Extended Data Fig. 1e). The villus-crypt structure was disorganized due to increased cell proliferation, but secretory cells (goblet, Paneth and enteroendocrine cells) were dramatically decreased in the villin-gp130Act small intestine (Fig. 1e,f; Extended Data Fig. 1f–h). Ectopic alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining in Tg small intestinal crypts, suggested abortive differentiation of absorptive enterocytes (Fig. 1g). Indeed, electron microscopy revealed short, thick, and non-uniform microvilli, typical of undifferentiated brush border cells (Extended Data Fig. 1i). Lamina propria CD45+ immune cells were increased in the Tg intestine, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF, were up-regulated (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b). However, more modest differences in the colonic mucosa were found between WT and Tg mice (Extended Data Fig. 2c), probably because the villin promoter is more active in the small intestine21.

Figure 1. Persistent gp130 activation causes aberrant IEC proliferation and differentiation.

(a) Wild-type (WT) and villin-gp130Act (Tg) small intestine lengths at 3 months (n=5). Data represent averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. (b) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of paraffin-embedded small intestinal sections from WT and Tg mice. Shown are representative images. (c, e–g) Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of paraffin-embedded small intestinal sections from WT and Tg mice (n=6). Ki67 and BrdU incorporation (c), Alcian blue (AB)+MMP7 and chromogranin A (ChrA) (e), Wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) (f), and alkaline phosphatase (AP) and DAPI (g) stainings. (d) Ki67 and BrdU positive cells were counted in each crypt. Data are averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. Scale bars represent 100 μm (b, c, e–g).

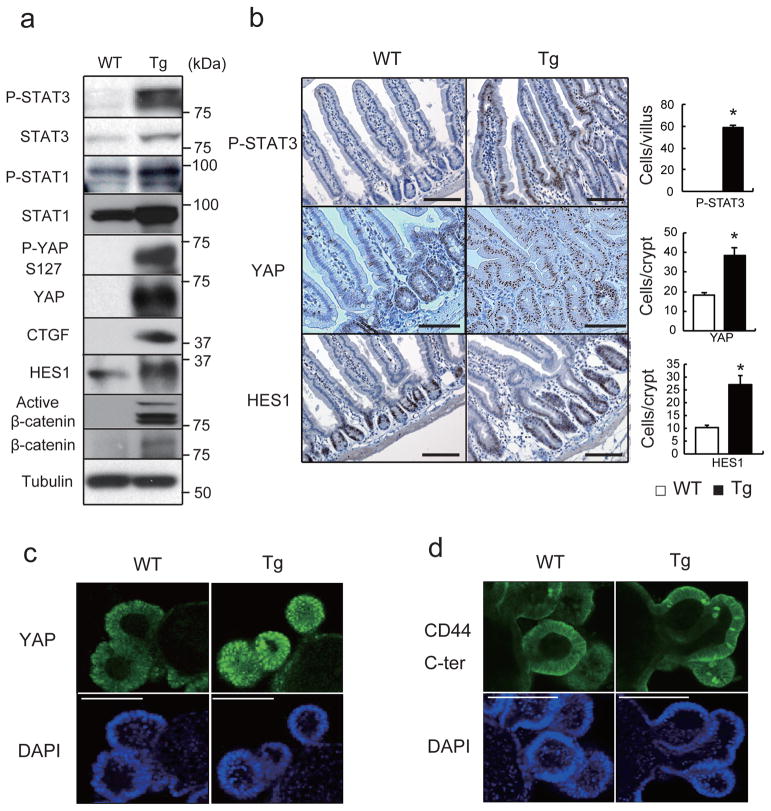

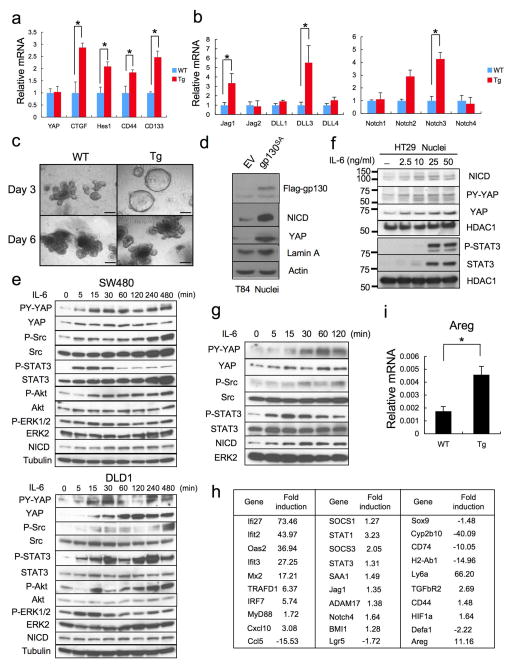

gp130 activates YAP and Notch signaling

The well-known gp130 effectors STAT3, STAT1 and ERK1/2 were activated in villin-gp130Act mice (Fig. 2a,b; Extended Data Fig. 2d,e). Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation, indicating mTORC1 activation, was also elevated in Tg small intestine (Extended Data Fig. 2d). An increase in undifferentiated, proliferating enterocytes and a decrease in secretory cell lineages are typical of mice with strongly activated YAP or Notch22–24, whereas Notch/γ-secretase inhibition converts proliferative IEC into goblet cells25. Indeed, YAP and its target gene, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), and the Notch target HES1 were strongly elevated in villin-gp130Act small intestine, along with higher amounts of activated β-catenin (Fig. 2a). YAP was mainly found in IEC nuclei in villi and crypts (Fig. 2b), as well as in colon (Extended Data Fig. 2e). Nuclear HES1 was also elevated in Tg small intestinal crypts (Fig. 2b) and strong nuclear YAP staining was observed in Tg intestinal organoids (Fig. 2c), a useful ex vivo system for studying IEC signaling26. YAP mRNA expression remained unchanged (Extended Data Fig. 3a), suggesting post-transcriptional regulation. CTGF and HES1, however, were up-regulated at the mRNA level along with mRNAs for intestinal stem cell markers, CD44 and CD133, and Notch ligands and receptors (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). Tg intestinal organoids at day 3 after passage formed more rounded structures, although no morphological difference was seen between them and WT organoids on day 6 (Extended Data Fig. 3c). Rounded organoids form upon β-catenin activation27, suggesting more active Wnt signaling in Tg organoids. YAP and Notch were also activated in human CRC cells expressing a gp130 superactive variant (gp130SA), which is refractory to feedback inhibition by SOCS3 due to an additional Y759F substitution (Extended Data Figs. 1a, 3d). CD44 cleavage, another γ-secretase mediated event28, was up-regulated in Tg small intestine and organoids (Fig. 2d; Extended Data Fig. 2d). IL-6 activated YAP and STAT3 in human CRC cells and mouse primary hepatocytes (Extended Data Figs. 3e–g).

Figure 2. gp130 activates YAP and Notch signaling.

(a) Lysates of WT and Tg jejuna were analyzed for expression and phosphorylation of the indicated proteins. (b) P-STAT3, YAP and HES1 stainings of paraffin-embedded small intestinal sections (n=6). Positive cells were enumerated in each villus or crypt. Data are averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. (c, d) WT and Tg small intestinal organoids stained with YAP (c) and CD44 C-terminal (d) antibodies were examined by immunofluorescent (IF) microscopy. Scale bars represent 100 μm (b–d) and all data are representative of at least 2-3 independent experiments.

Transcriptomic analysis confirmed the above results by showing strong enrichment for genes associated with innate immune response, response to viral infection and defense response in Tg crypts (Extended Data Fig. 3h). Similar observations were made in IHCA patients with gp130 activating mutations14. The growth factor amphiregulin (Areg), another YAP target29, was up-regulated in both villin-gp130Act intestinal crypts and organoids (Extended Data Fig. 3h,i).

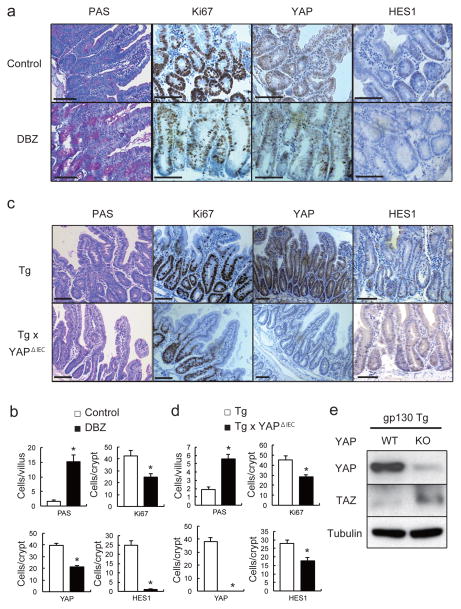

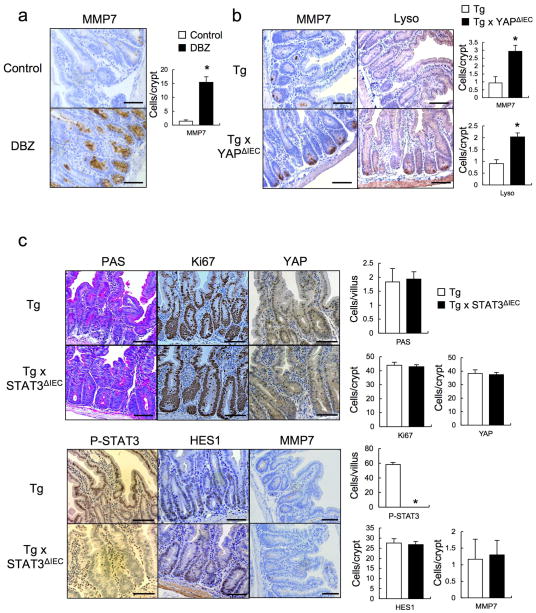

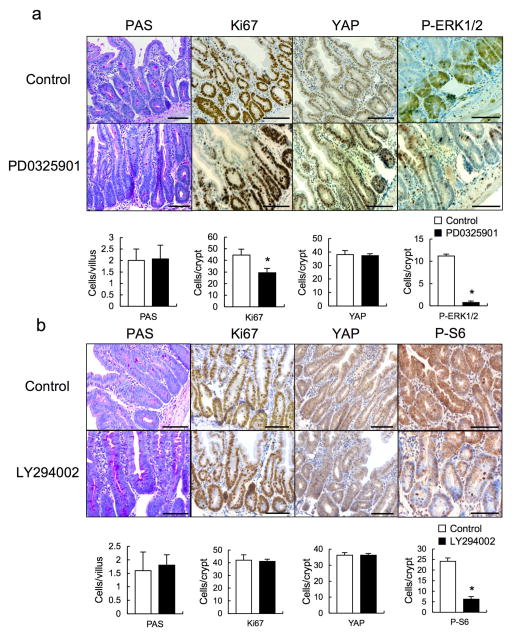

Notch or YAP inhibition partially restores tissue homeostasis

We examined if Notch or YAP inhibition restored epithelial homeostasis in Tg mice. To block Notch (and CD44) signaling we injected mice with a γ-secretase inhibitor, dibenzazepine (DBZ) and found it to restore secretory cell lineages, block HES1 expression and partially suppress hyperproliferation and YAP activation (Fig. 3a,b, Extended Data Fig. 4a). To delete YAP in IECs, we crossed Tg mice with villin-Cre x YapF/F (YapΔIEC) mice. YAP ablation largely restored secretory cell lineages and suppressed hyperproliferation and HES1 expression (Fig. 3c,d, Extended Data Fig. 4b). TAZ, a paralog, that partially compensates for YAP loss30, was up-regulated in YAP absence (Fig. 3e), possibly explaining the incomplete reversal of the Tg phenotype. We also investigated the contribution of other well-established gp130 effector pathways. We crossed Tg and villin-Cre x Stat3F/F (Stat3ΔIEC) mice. Surprisingly, STAT3 ablation did not affect the Tg phenotype (Extended Data Fig. 4c). MEK (PD0325901) or PI3K (LY294002) inhibitors also did not reverse the Tg phenotype, although they both inhibited their targets (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b).

Figure 3. Notch or YAP inhibition partially restores tissue homeostasis.

(a, b) PAS, Ki67, YAP and HES1 stainings of paraffin-embedded small intestinal sections from control and DBZ (10 μmol/kg)-treated Tg mice (n=3/group). Positive cells were enumerated in each villus or crypt (b). Data are averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. (c, d) Paraffin-embedded small intestinal sections from villin-gp130Act and villin-gp130Act/YapΔIEC mice (n=4/group) were stained and quantified as above (d). Data are averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. (e) Lysates of villin-gp130Act and villin-gp130Act/YapΔIEC jejuna were analyzed for the indicated proteins. Scale bars represent 100 μm (a, c) and all data are representative of at least 2–3 independent experiments.

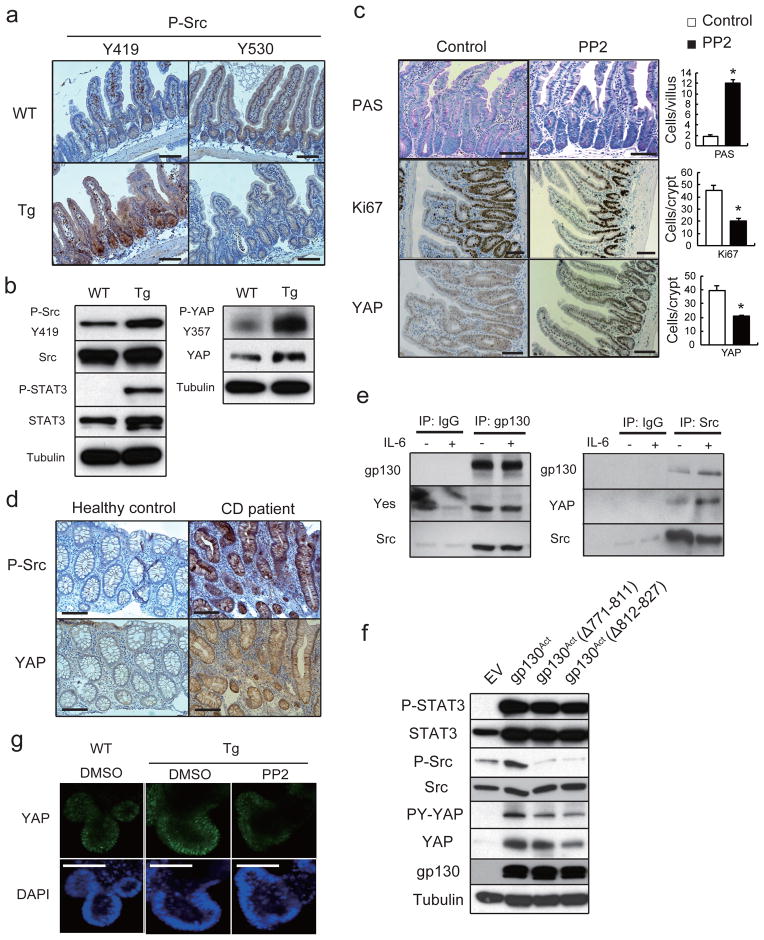

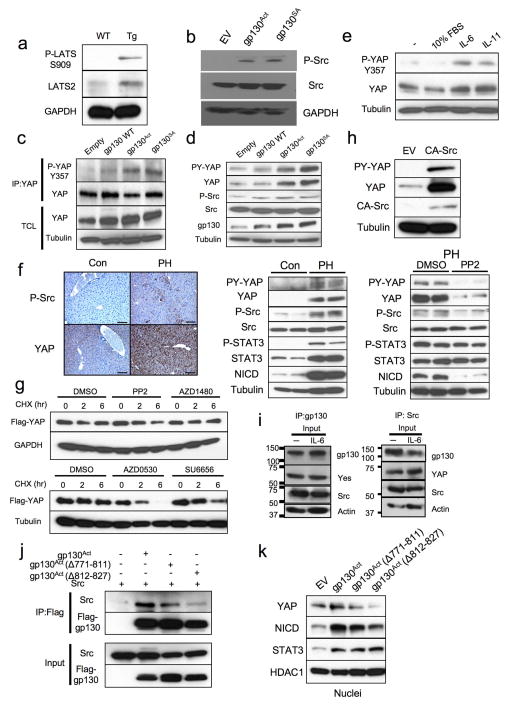

YAP up-regulation, also found in human IBD, requires gp130-mediated SFK activation

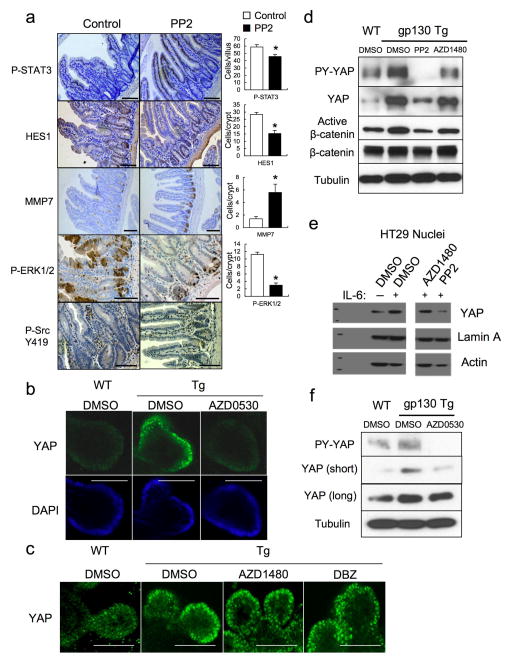

We did not detect a decrease in YAP or Hippo/LATS serine phosphorylation that could explain YAP activation in Tg IEC. On the contrary, both LATS and YAP S127 phosphorylation were elevated, suggesting enhanced Hippo activity (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 6a). Since Y357 phosphorylation by Yes also activates YAP19, we checked if SFKs were activated in the Tg small intestine. Human SFKs are positively regulated by Y419 phosphorylation and inhibited by Y530 phosphorylation31. Src/Yes Y419 was hyper-phosphorylated and Y530 was under-phosphorylated in villin-gp130Act IECs (Fig. 4a). SFK activation was also observed in villin-gp130Act intestinal organoids (Fig. 4b), human colon cancer cells overexpressing gp130Act or stimulated with IL-6, correlating with YAP Y357 phosphorylation (Extended Data Figs. 3e, 6b). YAP Y357 was also phosphorylated upon gp130Act expression in intestinal organoids or human colon cancer cells (Fig. 4b, Extended Data Fig. 6c,d), after IL-11 stimulation (Extended Data Fig. 6e), or in primary hepatocytes stimulated with IL-6 and mouse liver undergoing partial hepatectomy, which also exhibited Notch and SFK activation (Extended Data Fig. 3g, 6f). YAP and Notch activation in liver were inhibited by treatment with the Src inhibitor PP2, indicating SFK dependence (Extended Data Fig. 6f). Y357 phosphorylation increases YAP protein stability32. Indeed, Src, but not JAK, inhibition accelerated YAP degradation in cycloheximide-treated cells (Extended Data Fig. 6g). Src inhibition also decreased YAP in organoids (Extended Data Fig. 7d), whereas Src activation enhanced YAP expression (Extended Data Fig. 6h). Notably, elevated Src Y419 phosphorylation and YAP expression were detected in approximately 60% of colonic biopsies collected from CD patients (Fig. 4d; Extended Data Table 1). Both SFK phosphorylation and YAP up-regulation correlated with active disease.

Figure 4. SFK activate YAP downstream to gp130Act and are active in human IBD.

(a) IHC of activating (Y419) and inhibitory (Y530) Src phosphorylation in paraffin-embedded small intestinal sections from WT and Tg mice. (b) WT and Tg small intestinal organoids were lysed and analyzed for expression and phosphorylation of the indicated proteins. (c) Tg mice (n=4/group) were treated with PP2 (5 mg/kg) or vehicle once a day for 5 days. Small intestinal sections were stained as indicated. Positive cells were enumerated in each villus or crypt. Data are averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. (d) Normal (n=11) and CD (n=18) human colon biopsies were fixed, sectioned and stained as indicated. Src and YAP activation were found in 11/18 CD specimens in areas with active disease. (e) Co-immunoprecipitation (IP) of endogenous gp130, SFK and YAP in HT29 cells. Cells were collected with or without 2 hr IL-6 (10 ng/ml) stimulation. Lysates were IP’ed with gp130 (left) or Src (right) antibodies or corresponding IgG controls and probed with the indicated antibodies. (f) Total cell lysates of T84 colon cancer cells transfected with empty vector (EV), gp130Act, gp130Act(Δ771-811) or gp130Act(Δ812-827) expression vectors were prepared and subjected to IB analysis with the indicated antibodies. (g) WT and Tg small intestinal organoids were treated with DMSO and PP2 (10 μM) for 24 hrs, stained with YAP antibody and counter stained with DAPI. Scale bars represent 100 μm (a, c, d, g) and all data are representative of at least 2–3 independent experiments.

Importantly, gp130 interacted with endogenous Src and Yes and both gp130 and YAP co-immunoprecipitated with Src (Fig. 4e, Extended Data Fig. 6i). Deletion of gp130 AA 812-827, which contain a phosphotyrosine motif, reduced binding to Src and attenuated activation of Src, YAP and Notch, but not STAT3 (Fig. 4f, Extended Data Fig. 6j,k). These data suggest that gp130 activates YAP through its interaction with SFK, independently of STAT3. Treatment of villin-gp130Act mice with PP2 restored secretory cell lineages and inhibited IEC hyperproliferation, Src Y419 phosphorylation, HES1 expression, as well as ERK and YAP activation with only a modest effect on STAT3 (Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 7a). PP2 and another SFK inhibitor (AZD0530), but not a JAK inhibitor (AZD1480) or DBZ, suppressed nuclear YAP in villin-gp130Act intestinal organoids (Fig. 4g, Extended Data Fig. 7b,c). Consistent with a recent report that YAP potentiates β-catenin activation33, Tg organoids contained more activated β-catenin and Src inhibition reversed this effect (Extended Data Fig. 7d). Src, but not JAK inhibitors, blocked IL-6- or gp130Act-induced YAP activation and stabilization in human CRC cells and mouse small intestinal organoids (Extended Data Fig. 7d–f).

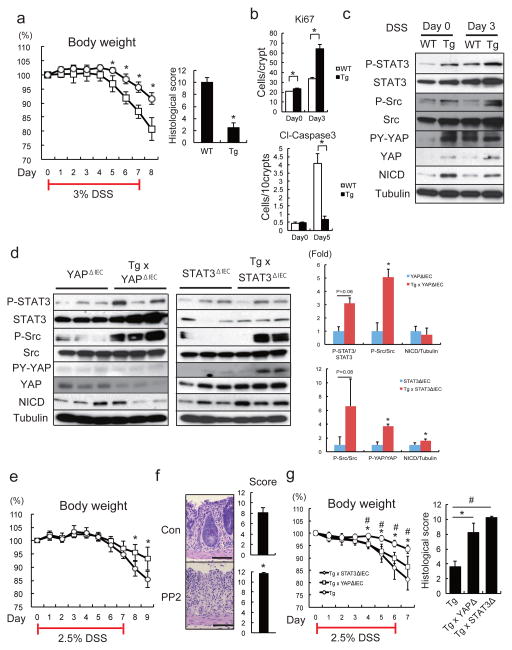

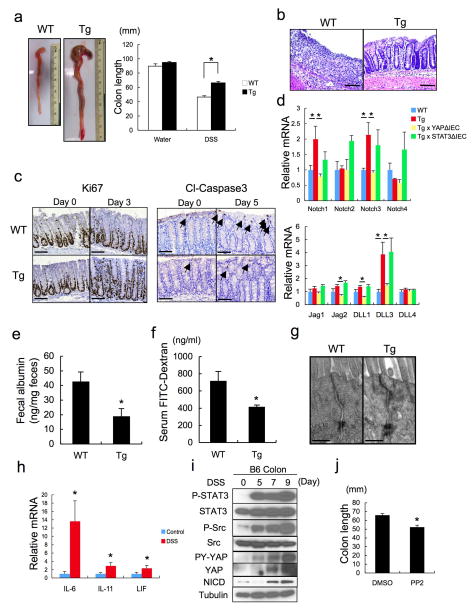

gp130-SFK-YAP signaling is activated upon mucosal erosion to promote regeneration

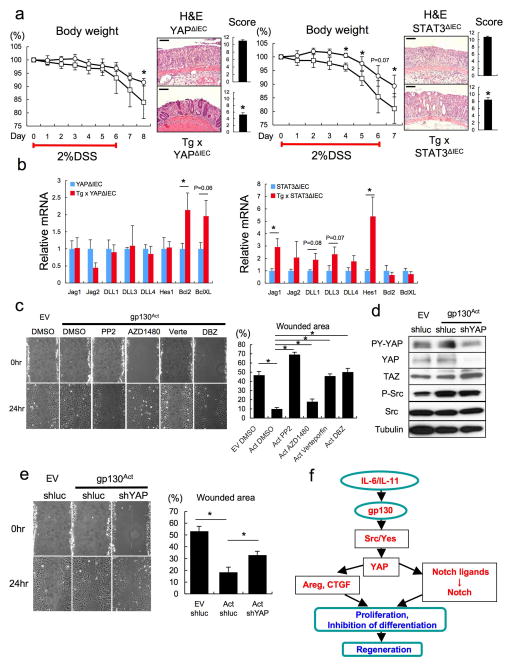

To examine gp130-SFK-YAP signaling during intestinal regeneration, we induced mucosal erosion with DSS. Tg mice exhibited less severe colitis and weight loss than WT mice, as well as reduced colon shortening and improved crypt architecture (Fig. 5a, Extended Data Fig. 8a,b), which are the opposite phenotypes of IEC-specific STAT3 or YAP deficiencies13,16. The colonic epithelium of Tg mice showed more proliferation and less apoptosis during DSS colitis (Fig. 5b, Extended Data Fig. 8c), as well as elevated STAT3, SFK and YAP phosphorylation and Notch activation (Fig. 5c). Notch receptors and ligands were elevated in Tg colons and their expression decreased upon YAP, but not STAT3, ablation (Extended Data Fig. 8d). Tg mice also showed an improved gut barrier function, despite no obvious differences in IEC tight junctions relative to WT mice (Extended Data Fig. 8e–g). DSS treatment induced IL-6 family cytokines in the colon and led to strong SFK-YAP and STAT3 activation (Extended Data Fig. 8h,i). Inhibition of SFK signaling with PP2 during DSS challenge suppressed intestinal regeneration (Fig. 5e,f; Extended Data Fig. 8j). IEC-specific YAP or STAT3 ablation in Tg mice increased DSS-induced weight loss and tissue damage (Fig. 5g). By contrast, gp130Act conferred DSS resistance on YapΔIEC and Stat3ΔIEC mice, although not as strongly as its effect in WT mice (Extended Data Fig. 9a). Thus, both YAP and STAT3 contribute to mucosal regeneration. However, YAP was not required for STAT3 activation and STAT3 was not needed for YAP and Notch activation and neither YAP nor STAT3 affected SFK activation (Fig. 5d). YAP, but not STAT3, was required for induction of Notch ligands and receptors, although STAT3 was essential for Bcl2 and Bcl-XL induction (Extended Data Fig. 9b).

Figure 5. gp130-SFK-YAP signaling is activated upon mucosal erosion to promote regeneration.

(a) Body weight curves and day 10 histological scores of DSS-treated WT (□) and Tg (○) mice (n=4/group). Results are averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. (b) Ki67 (upper panels) and cleaved-caspase3 (lower panels) stainings of colon sections from WT and Tg mice at day 0 and 3 (Ki67) or 5 (cleaved-caspase3) after 3.0% DSS treatment. Positive cells were enumerated in representative microscopic fields (magnification 200 × for Ki67 and 100 × for cleaved-caspase3) (n=6) per time point. Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. (c) WT and Tg mice were treated as above. Colonic lysates were prepared when indicated and IB analyzed for indicated proteins. (d) Lysates of YapΔIEC and villin-gp130Act/YapΔIEC, or Stat3ΔIEC and villin-gp130Act/Stat3ΔIEC colons were prepared, and IB analyzed with the indicated antibodies. Data were quantified using ImageJ software and are depicted on right as averages ± SEM (n=3/group). *P < 0.05. (e) Body weight curves of DSS-treated control (□) and PP2-injected (5 mg/kg) (○) C57BL/6 mice (n=6/group). Results are averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. (f) Mucosal histology of above mice was scored at day 10 of DSS challenge by H&E staining. Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (g) Body weight curves and day 9 histological scores of villin-gp130Act (○), villin-gp130Act/YapΔIEC (□) and villin-gp130Act/Stat3ΔIEC (◇) mice treated with 2.5% DSS (n=5/group). Results are averages ± SD (body weight curves) or averages ± SEM (histological scores). *P < 0.05: villin-gp130Act vs villin-gp130Act/YapΔIEC mice. #P < 0.05: villin-gp130Act vs villin-gp130Act/Stat3ΔIEC mice.

We examined if gp130 signaling controls “wound healing” in the absence of inflammation. Expression of gp130Act in rat IEC6 cells enhanced “wound” closure after monolayer scratching (Extended Data Fig. 9c). This effect was attenuated by Src, YAP and Notch inhibitors but hardly influenced by a JAK inhibitor. Silencing of YAP also attenuated “wound” closure, although it did not inhibit Src activation (Extended Data Fig. 9d,e). Altogether these data support the signaling scheme outlined in Extended Data Fig. 9f and indicate that once gp130 is activated it can contribute to healing, regeneration and termination of inflammation via the SFK-YAP-Notch cascade in addition to its well-established effect on STAT3, even without ongoing inflammation.

Discussion

IL-6, produced by lamina propria myeloid cells that encounter translocating microbiota or their products, is a potent activator of the newly charted gp130-SFK-YAP-Notch pathway. Receptor binding by IL-6 and related cytokines engages gp130, which in addition to its well established effectors, the SHP-2-ERK, PI3K-Akt-mTORC1 and JAK-STAT3 modules, interacts with and activates Src and Yes. These SFKs bind YAP through their conserved SH3 domain, which recognizes a proline-rich binding motif (SH3bm) located between the YAP WW motif and transcriptional activation domain34, and activate YAP through Y357 phosphorylation19; thereby stabilizing the protein and increasing its nuclear concentration. It would be of interest to examine the effect of SH3bm inactivation on intestinal regeneration, as long as such mutations do not interfere with other aspects of YAP regulation. Another, but less direct, link between gp130 and YAP may be provided by SHP-2, whose subcellular distribution is controlled through interaction with YAP and TAZ35.

By binding transcription factors, such as TEAD18, YAP controls genes that stimulate cell proliferation and tissue growth and inhibit terminal differentiation22. Such genes include growth factors such as CTGF and Areg29 and Jagged-1, a Notch ligand36, whose expression is up-regulated in the villin-gp130Act intestinal epithelium, along with Notch 1/3 and DLL 3. This results in Notch activation, which can further sustain YAP activity37. Although YAP and Notch are required for mucosal regeneration16,17, the mechanisms responsible for their activation upon injury and inflammation were heretofore unknown. In fact, until recently, activation of YAP, was believed to solely depend on inhibition of Hippo signaling that retains YAP in the cytoplasm18. Only recently, G protein coupled receptors were found to activate YAP through a partially understood Hippo-independent mechanism38, and in cancer cells Yes was demonstrated to activate YAP via tyrosine phosphorylation19. However, the physiological role of YAP tyrosine phosphorylation in normal tissues remained unknown. We now show that SFK-induced YAP activation, rather than Hippo inhibition, is critical for regeneration of the injured intestinal mucosa. The same pathway is activated after partial hepatectomy and may contribute to liver regeneration. YAP Y357 phosphorylation may also be regulated by the tumor suppressor RASSF1A, but its effect may be indirect as Rassf1a−/− mice exhibit elevated IL-6 production after DSS-induced injury39.

The IL-6 family member LIF stimulates self-renewal of cultured embryonic stem (ES) cells through a gp130-Yes-YAP module40, but the in vivo relevance of this finding was not established. Another gp130 effector, STAT3, was also suggested to maintain ES cell pluripotency41. Thus, it is plausible that gp130-activating cytokines are general regulators of tissue homeostasis and regeneration. Expression of IL-6 family members is elevated in a number of chronic inflammatory diseases and GI cancers42 and our results demonstrate frequent SFK and YAP activation in CD. Although previous efforts in targeting the pro-tumorigenic activity of IL-6 related cytokines had focused on the JAK-STAT3 module43, it should be noted that Yes and Src are often activated in CRC, even though the cause of their activation was not identified31,44. Furthermore, Src controls intestinal regeneration in both mice and flies44. We suggest that SFK activation during IBD regeneration and CRC is caused by IL-6 family members. Nonetheless, villin-gp130Act mice do not develop malignant tumors before 12 months of age, indicating that chronic YAP, Notch and STAT3 activation are insufficient for oncogenic transformation.

Persistent YAP and Notch activation results in skewed differentiation of intestinal stem cells, entailing expansion of immature enterocytes and under-representation of secretory cell types. The paucity of Paneth and goblet cells in villin-gp130Act mice resembles their deficiency in IBD, which may reflect chronic elevation of IL-6 or IL-11 and persistent Src and YAP activation. Nonetheless, despite the deficiency in defensin-producing Paneth cells and mucin-producing goblet cells, villin-gp130Act mice display an improved gut barrier function, underscoring the importance of epithelial regeneration in preventing excessive microbial translocation. Thus, future therapeutic efforts in IBD should aim at normalizing IL-6 cytokine expression, rather than complete blockade, thereby restoring immune and epithelial homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Mice

gp130Act cDNA14 was amplified by PCR and subcloned into a plasmid containing the 12.4-kb Villin promoter (A gift from Dr. D.L. Gumucio, University of Michigan)21. The 15.7-kb expression cassette was excised by PmeI digestion, purified, and injected into fertilized C57BL/6 oocytes to obtain founder mice, two of which transmitted the gp130Act transgene. C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. Villin-Cre mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Stat3F/F and YapF/F mice have been described45,46. All mice were on the C57BL/6 background and were maintained in filter-topped cages on autoclaved food and water at UCSD according to NIH guidelines. Beddings were interchanged between the different strains to minimize microbiome alterations. All experiments were performed in accordance with UCSD and NIH guidelines and regulations.

Human colon samples

Human tissue specimens were retrospectively obtained from routine colonoscopic biopsies fixed in buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin using standard methods. Corresponding clinical data was recorded from medical records and de-identified. The study was approved by the institutional review board and research and development committee of the VA San Diego Healthcare System. Subjects had either established Crohn’s disease based on clinical, endoscopic, and histopathologic criteria, or were normal based on the absence of systemic clinical disease, a normal colonoscopic exam, and normal histopathology.

Reagents and plasmids

Recombinant Noggin, IL-6 and IL-11 were purchased from Peprotech, recombinant EGF and Wheat germ agglutinin conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 were from Life Technologies, DBZ (γ-secretase inhibitor) from Axon Medchem, PP2 (Src inhibitor), SU 6656 (Src inhibitor) and LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor) from Sigma, PD0325901 (MEK inhibitor) from Stemgent, and AZD0530 (Src inhibitor) and verteporfin (YAP inhibitor) from Selleck Chemicals. AZD1480 (JAK inhibitor) was kindly provided by Dr. D. Huszar (AstraZeneca). 293T-HA-RspoI-Fc cells were kindly provided by Dr. C. Kuo (Stanford University)47. To generate gp130 expression vectors, WT gp130, gp130Act, and gp130SA were amplified by PCR and subcloned into lentiviral expression vectors. gp130Act deletion mutants were constructed by a PCR-based approach using PrimeSTAR Max (TaKaRa Bio). pcDNA FLAG-YAP 32 was obtained from Addgene (Plasmid 18881). For shRNA transduction, pLKO.1-puro lentiviral vectors (Sigma-Aldrich) targeting YAP (TRCN0000238432) or luciferase (control) were used.

Cell culture

HEK293T, HT29, HCA7, SW480, DLD1, HCT116 and IEC6 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, and streptomycin. T84 cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin, and streptomycin.

Cytokine treatment

Following overnight starvation with serum-free medium, colon cancer cells were treated with recombinant human IL-6 or IL-11 for the indicated time. For those treated with inhibitors, PP2 or AZD1480, cells were pre-treated for 1–2 hr with the inhibitor prior to the cytokine treatment.

Transient transfection

HEK293T cells were transfected with CA-Src expression vector48, or co-transfected with the indicated plasmids, gp130 expression vector together with c-Src expression vector48 by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, USA) as described by the manufacturer. Forty-eight hr later, total protein lysates were harvested from the transfected cells and subjected to immununoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis.

Etopic expression of gp130 variants in colon cancer cells

Cultured cells were infected with empty viruses (EV), or lentiviruses bearing FLAG-tagged wild-type (WT), active (gp130Act) or superactive gp130 (gp130SA). Stably infected cells were enriched by G418 selection for 2–3 weeks. Ectopic gp130 expression was confirmed by immunoblot analysis using anti-FLAG and anti-gp130 antisera.

Nuclear and cytosol fractionation

Nuclear and cytosol fractions were prepared as previously described49. Briefly, the indicated cells were washed with PBS and then harvested in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH6.8, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.05% NP40, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 50 mM NaF and 1 nM okadaic acid) containing protease inhibitors. Following lysate centrifugation at 20,800 x g for 15 min at 4°C, the supernatant was collected for cytosolic fraction. The pellet was washed with buffers I and II (I: 10 mM HEPES, pH6.8, 25 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 300 mM sucrose, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 50 mM NaF; II: 1 M sucrose, 1 mM NaVO4, and 50 mM NaF) followed by centrifugation at 2,700 x g for 5 min at 4°C. The resulting pellet was extracted with an extraction buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH7.9, 300 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 mM NaF and 1 nM okdadaic acid) on ice for 30 min. After centrifugation at 20,800 x g for 15 min at 4°C, the supernatant was saved as nuclear extract for subsequent studies.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis

Equal amounts of total protein from each sample were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Protein blots were hybridized with the indicated primary antibody of interest and then with secondary antibody, followed by detection with Immobilon Western system (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA). For immunoprecipitation, the cells were lysed in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, PhosSTOP Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche Applied Sciences), and cOmplete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche Applied Sciences). The lysates were cleared by centrifugation at top speed for 15 min. Immunecomplexes were collected with the antibody of interest and protein G/A agarose beads, followed by immunoblotting as described. Immunoblotting was performed with antibodies to phospho-YAP Y357 (Abcam or Sigma), c-Yes, β-catenin (BD), phospho-Src, Src, phospho-STAT3, phospho-ERK1/2, phospho-Akt S473, phospho-YAP S127, YAP, TAZ, NICD, active-β-catenin, phospho-LATS, LATS2 (Cell Signaling), phospho-STAT1 (Upstate), HES1, STAT3, STAT1, ERK2, Akt, Lamin A, HDAC1, GAPDH (Santa Cruz), tubulin, actin, FLAG (Sigma) and CTGF (GeneTex).

Real-Time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) or an RNeasy Plus Kit (QIAGEN). RNA was reverse transcribed using an iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) or SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Life Technologies). Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR green (Bio-Rad) on a Bio-Rad CFX96 machine. The comparative threshold cycle method and an internal control (18S rRNA, β-Actin or GAPDH) were used to normalize the expression of the target genes.

In vivo treatment with inhibitors

Mice were treated with DBZ (10 μmol/kg), PP2 (5 mg/kg), PD0325901 (25 mg/kg), LY294002 (100 mg/kg) and vehicle for 5 days except DSS-induced colitis as previously described25,50–52. The mice were killed after the treatment and the intestines were collected for further analysis. For DSS-induced colitis, mice were treated with PP2 (5 mg/kg) or vehicle every day from day −2 to day 10. Mice were treated with PP2 (5 mg/kg) or vehicle every day from day −1 to day 2 in a model of partial hepatectomy.

In vitro scratch/wound healing assay

IEC6 cells transfected with empty vector (EV) or gp130Act expression vector were plated to confluence and starved overnight, and then scratched to cause a wound in the monolayer. Cells were treated with DMSO, PP2 (10 μM), AZD1480 (1 μM), verteporfin (1 μg/ml) or DBZ (10 μM) for 24 hours. Images from 5 independent fields were taken at 0- and 24-hour time points with a Carl Zeiss inverted microscope at a magnification of ×10. The percentage of wound closure was quantified with Image J software.

DSS-induced colitis

Mice received water with 2.0–3.0% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS; MP Biomedicals, molecular weight 36,000–50,000 kDa, or Affymetrix, molecular weight 40,000–50,000 kDa) for 6–7 days. After this, mice were maintained on regular water and were killed on day 8–10. One half of the distal colon was taken as a tissue sample and snap frozen for subsequent RNA and protein analysis. The other half was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde or 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hr for subsequent paraffin embedding and histological analysis. The clinical course of disease was followed daily by measurement of body weight. Colonic histology scores were determined by an observer blinded to genotype as previously described53.

Histological analysis

Mouse intestine samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde or 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hr and paraffin embedded. 5 μm thick serial sections were used for H&E or other staining. Antibodies used were against: CD44 C-terminal, Chromogranin A (Abcam), BrdU, CD45 (eBioscience), phospho-Src, phospho-STAT3, phospho-STAT1, YAP, HES1, MMP7, phospho-ERK1/2, phospho-S6, CyclinD1 (Cell Signaling), Lysozyme (Santa Cruz), Ki67 and c-Myc (GeneTex). Measurements for each quantitative outcome were collected from 30–50 crypts or villi analyzed from 3–6 independent fields of small intestine or colon of several independent mice (n=2–6).

Electron microscopic analysis

Tissue samples from small intestines were fixed in modified Karnovsky’s fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.15 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4) for 24 hr at 4°C, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.15 M cacodylate buffer for 1 hr and stained en bloc in 2% uranyl acetate for 1 hr. Samples were dehydrated in ethanol, embedded in Durcupan epoxy resin (Sigma-Aldrich), sectioned at 50 to 60 nm on a Leica UCT ultramicrotome, and picked up on Formvar and carbon-coated copper grids. Sections were stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 5 minutes and Sato’s lead stain for 1 minute. Grids were viewed using a JEOL 1200EX II (JEOL, Peabody, MA) transmission electron microscope and photographed using a Gatan digital camera (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA).

Intestinal organoid culture and staining

Small intestinal crypts were isolated from WT and villin-gp130Act small intestines and were cultured and stained as previously described54,55.

Intestinal permeability in vivo

Intestinal permeability and gut barrier function were measured using the FITC-labeled dextran method as previously described 56 and by measuring fecal albumin. Fecal albumin measurements were performed with dried fecal pellets using the Mouse Albumin ELISA Quantitation Set obtained from Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, TX, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

In situ hybridization

Intestinal paraffin sections were hybridized to anti-Cryptdin-1 probe as previously described 57.

Isolation of primary mouse hepatocytes and 2/3 partial hepatectomy

Primary mouse hepatocytes were isolated and cultured as described58. 2/3rd partial hepatectomy was performed as previously described 59.

Microarray analysis

Small intestinal crypts were isolated from WT and villin-gp130Act small intestines as previously described 54. Total RNA was isolated from the isolated crypts using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and used for microarray analysis with the Illumina MouseWG-6 v2 Expression BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego). Microarray processing, data normalization and analysis were done as previously described60.

Accession codes

Microarray data reported here have been deposited in the ArrayExpress database (accession E-MEXP-E-MTAB-2400).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD or the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was conducted using Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test for multiple comparisons. Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison of categorical variables between CD patients and healthy controls. Statistical significance was defined as a P value of <0.05.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. gp130Act expression and intestinal phenotype.

(a) Schematic diagram of the villin-gp130Act transgenic (Tg) construct and the gp130Act and gp130SA variants. (b) Expression of gp130Act in the villin-gp130Act jejunum was confirmed by RT-PCR with specific primers for human gp130. Cyclophilin (CPH) was used as an internal control. (c) Representative images of WT and villin-gp130Act intestines. c-Myc and CyclinD1 (d) and TUNEL (red: TUNEL; blue: DAPI) (e) staining of paraffin-embedded sections of WT and villin-gp130Act small intestines from 3-month old mice. Positive cells were enumerated in each villus or crypt (n=6). Data represent averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. (f) MMP7, AB and ChrA positive cells in WT and villin-gp130Act small intestines were enumerated in each villus or crypt (n=6). Data represent averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. (g) Paraffin embedded sections of WT and villin-gp130Act small intestines were analyzed by PAS and lysozyme staining. Positive cells were enumerated in each villus or crypt (n=6). Data represent averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. (h) Cryptdin mRNA in WT and villin-gp130Act jejunum was detected by in situ hybridization. (i) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of the apical surface of WT and Tg small intestines. Scale bars represent 100 μm (d, e, g, h) and 1 μm (i) and all data are representative of at least 2–3 independent experiments.

Extended Data Figure 2. Aberrant intestinal differentiation and activation of gp130 effectors in gp130Act mice.

(a) Paraffin embedded sections of WT and villin-gp130Act small intestines were analyzed by CD45 staining. (b) Lysates of WT and villin-gp130Act jejuna were prepared, and expression of IL-6 and TNF mRNAs was analyzed by qRT-PCR (n=3). Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. (c) H&E and PAS staining of paraffin-embedded sections of WT and villin-gp130Act large intestines. (d) P-STAT1, P-ERK1/2, P-S6, and CD44 C-terminal stainings of paraffin-embedded sections of WT and villin-gp130Act small intestines. Positive cells were enumerated in each villus or crypt (n=4). Data represent averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. (e) YAP, Ki67, and P-STAT3 stainings of paraffin-embedded sections of WT and villin-gp130Act large intestines. Positive cells were enumerated in each crypt (n=4). Data represent averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. Scale bars represent 100 μm (a, c–e) and all data are representative of at least 2–3 independent experiments.

Extended Data Figure 3. IL-6 and gp130 induce Notch and YAP activation in intestinal organoids and cancer cells, and gene expression analysis of intestinal crypts.

(a,b) WT and villin-gp130Act organoids were cultured, their RNA extracted, and expression of the indicated mRNA species was measured by qRT-PCR (n=3). Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. (c) Appearance of WT and villin-gp130Act small intestinal organoids cultured in standard EGF/Noggin/R-spondin 1 medium. (d) Nuclei of T84 colon cancer cells transfected with either empty vector (EV) or a vector encoding superactive gp130 (gp130SA) were lysed and subjected to IB analysis with the indicated antibodies. Lamin A, a nuclear marker. Actin, a loading control. (e) Lysates of serum-starved SW480 (upper) or DLD1 (lower) colon cancer cells treated for 0–480 min with IL-6 at 50 ng/ml were subjected to immunoblot analysis using the indicated antibodies. (f) Nuclei of serum-starved HT29 colon cancer cells treated for 24 hrs with IL-6 at 0–50 ng/ml were lysed and subjected to IB analysis with the indicated antibodies. HDAC, a nuclear marker and loading control. (g) Lysates of primary mouse hepatocytes treated for 0–120 min with IL-6 at 50 ng/ml were subjected to immunoblot analysis using the indicated antibodies. (h) Microarray analysis was performed using the Illumina MouseWG-6 v2 Expression BeadChip on RNA extracted from WT and villin-gp130Act small intestinal crypts (n=3/group). Data were normalized and analyzed as described and expression of the indicated genes is shown as fold-induction compared to WT crypts. (i) RNA was extracted from of WT and villin-gp130Act small intestinal organoids, and Areg mRNA expression was measured by qRT-PCR (n=3). Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. Scale bars represent 100 μm (c) and all data are representative of at least 2–3 independent experiments.

Extended Data Figure 4. Aberrant intestinal differentiation in gp130Act mice depends on Notch and YAP but not on STAT3.

(a) MMP7 staining of paraffin-embedded sections of control and DBZ-treated (10 μmol/kg) villin-gp130Act small intestines. Positive cells were enumerated in each crypt (n=3). Data represent averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. (b) MMP7 and lysozyme staining of paraffin-embedded sections of villin-gp130Act and villin-gp130Act/YapΔIEC small intestines. Positive cells were enumerated in each crypt (n=4). Data represent averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. (c) PAS, Ki67, YAP, P-STAT3, HES1 and MMP7 staining of paraffin-embedded sections of villin-gp130Act and villin-gp130Act/Stat3ΔIEC small intestines. Positive cells were enumerated in each villus or crypt (n=4). Data represent averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. Scale bars represent 100 μm (a–c) and all data are representative of at least 2–3 independent experiments.

Extended Data Figure 5. MEK and PI3K inhibitors have no effect on aberrant intestinal homeostasis in gp130Act mice.

(a) PAS, Ki67, YAP, and P-ERK1/2 staining of paraffin-embedded sections of control and PD0325901-treated (25 mg/kg) villin-gp130Act small intestines. Positive cells were enumerated in each villus or crypt (n=3). Data represent averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. (b) PAS, Ki67, YAP and P-S6 staining of paraffin-embedded sections of control and LY294002-treated (100 mg/kg) villin-gp130Act small intestines. Positive cells were enumerated in each villus or crypt (n=3). Data represent averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. Scale bars represent 100 μm (a, b).

Extended Data Figure 6. gp130 activates YAP via a Hippo-independent but tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent mechanism, and gp130 interacts with Src and Yes.

(a) Lysates of WT and villin-gp130Act jejuna, which are the same as the ones in Fig. 2a, were analyzed for expression and phosphorylation of the indicated proteins. (b) Lysates of HT29 colon cancer cells transfected with either empty vector (EV), active gp130 (gp130Act), or superactive gp130 (gp130SA) were subjected to IB analysis with P-Src (Y419), total Src and GAPDH antibodies. GAPDH, a loading control. (c) Lysates of HCA7 colon cancer cells infected with EV, WT gp130, gp130Act, or gp130SA lentiviruses were immunoprecipitated with anti-YAP antibody and blotted with the indicated antibodies. (d) Lysates of HT29 colon cancer cells infected with EV, WT gp130, gp130Act, or gp130SA lentiviruses were IB analyzed for expression and phosphorylation of the indicated proteins. (e) Serum-starved HCT116 cells were stimulated with 10% FBS, IL-6 (100 ng/ml), or IL-11 (100 ng/ml) for 30 min. Total cell lysates were analyzed for expression and phosphorylation of the indicated proteins. (f) Left panel: P-Src and YAP staining of livers from untreated wild-type mice (control) and wild-type mice 48 hrs after partial hepatectomy (PH). Scale bars represent 100 μm. Middle panel: Lysates of livers from control mice and mice 48 hrs after PH were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. Right panel: Lysates of livers from vehicle (DMSO)-treated and PP2-treated mice 48 hrs after PH were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies (g) upper: HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing FLAG-YAP. Twenty-four hrs after transfection, the cells were pre-treated for 1 hr with 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control), PP2 (10 μM) or AZD1480 (1 μM) and then were treated with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide for different time points. Total cell lysates were subjected to IB analysis with the indicated antibodies. lower: HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-YAP as above. Twenty-four hrs after transfection, the cells were pre-treated for 1 hr with 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control), AZD0530 (10 μM) or SU6656 (10 μM) and then were treated with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide for different time points. Total cell lysates were analyzed as above. (h) HEK293T cells were transfected with either empty or constitutively active (CA) Src expression vectors. After 48 hrs, the cells were lysed and expression of the indicated proteins determined by IB analysis. (i) HT29 cells were collected with or without 10 ng/ml IL-6 stimulation for 2 hrs. Lysates were analyzed by IB with the indicated antibodies. These are the loading controls for the data shown in Fig. 4e. (j) HEK293T cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding Src and FLAG-tagged gp130Act, FLAG-tagged gp130Act (Δ771-811), FLAG-tagged gp130Act (Δ812-827) or empty vector. Cells were collected 48 hrs later. Cell lysates were IP’ed with FLAG antibody and analyzed by IB with the indicated antibodies. (k) Nuclei of T84 colon cancer cells transfected with empty vector (EV), gp130Act, gp130Act (Δ771-811) or gp130Act (Δ812-827) expression vectors were prepared and subjected to IB analysis with the indicated antibodies. HDAC1, a nuclear marker and loading control. All data are representative of at least 2–3 independent experiments.

Extended Data Figure 7. SFK activity is required for YAP activation.

(a) Tg mice (n=4/group) were treated with PP2 (5 mg/kg) or vehicle once a day for 5 days. Small intestines were isolated, sectioned and stained as indicated. Positive cells were enumerated in each villus or crypt. Data represent averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. (b,c) WT and villin-gp130Act small intestinal organoids were treated with DMSO, AZD0530 (10 μM) (b), AZD1480 (1 μM) or DBZ (10 μM) (c) for 24 hrs, stained with YAP antibody and counter stained with DAPI and photographed under a fluorescent microscope. (d) WT and villin-gp130Act small intestinal organoids were treated with DMSO, PP2 (10 μM) and AZD1480 (1 μM) for 24 hrs. Total cell lysates were subjected to IB analysis with the indicated antibodies. (e) Serum-starved HT29 cells were pre-treated for 1 hr with 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control), AZD1480 (10 μM) or PP2 (20 μM) prior to IL-6 (10 ng/ml) stimulation for 24 hrs. Nuclear extracts of HT29 cells treated without or with IL-6 in the absence or presence of AZD1480 or PP2 were subjected to IB analysis with the indicated antibodies. Lamin A, a nuclear marker; Actin, a loading control. (f) WT and villin-gp130Act small intestinal organoids were treated with DMSO and AZD0530 (10 μM) for 24 hrs. Total cell lysates were subjected to IB analysis with the indicated antibodies. Scale bars represent 100 μm (a–c). All data are representative of at least 2–3 independent experiments.

Extended Data Figure 8. gp130Act confers DSS resistance, induces Notch receptors and ligands and improves barrier function.

(a) left: Representative images of WT and villin-gp130Act large intestines taken 10 days after 3.0% DSS treatment. right: Colon length of WT and villin-gp130Act mice before and after DSS treatment (before: n=5/group, after: n=4/group). Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. (b) Representative images of H&E stained paraffin-embedded colon sections prepared 10 days after DSS challenge of WT and Tg mice as described in Fig. 5a. Magnification bars: 100 μm. (c) Ki67 (left panels) and cleaved-caspase3 (right panels) stainings were performed on paraffin-embedded colon sections from WT and Tg mice at day 0 and 3 (Ki67) or 5 (cleaved-caspase3) after 3.0% DSS treatment. (d) Lysates of WT, villin-gp130Act, villin-gp130Act/YapΔIEC and villin-gp130Act/Stat3ΔIEC colons were prepared, RNA was extracted and expression of the indicated mRNA species was analyzed by qRT-PCR (n=3/group). Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (e, f) Gut barrier function in WT and villin-gp130Act mice was examined by measurements of fecal albumin (WT: n=6, Tg: n=7) (e) and FITC-Dextran translocation to blood 4 hrs after oral gavage (WT: n=5, Tg: n=4) (f). Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. (g) TEM images of intestinal mucosa epithelial cell-cell junctions in WT and villin-gp130Act small intestines. (h) C57BL/6 mice were given regular water or 2.5% DSS for 7 days. Colonic RNA was extracted on day 10, and expression of the indicated genes was analyzed by qRT-PCR (n=4). Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. (i) WT mice were given 2.5% DSS. Colonic lysates were prepared when indicated and IB analyzed for protein expression and phosphorylation. (j) Colon length of control and PP2-injected C57BL/6 mice after DSS treatment (n=6/group). Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. Scale bars represent 100 μm (b, c) and 500 nm (g).

Extended Data Figure 9. Enhanced mucosal regeneration in gp130Act mice depends on YAP and STAT3 but the two effectors control different genes, and YAP is required for in vitro scratch closure.

(a) Left: Body weight curves of DSS-treated YapΔIEC (□, n=6) and villin-gp130Act/YapΔIEC (○, n=4) mice. Results are averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. Colon mucosal histology of YapΔIEC (□, n=6) and villin-gp130Act/YapΔIEC (○, n=4) mice was examined by H&E staining and scored 9 days after 2.0% DSS challenge by an observer blinded to the mouse genotype. Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. Right: Body weight curves of DSS-treated Stat3ΔIEC (□) and villin-gp130Act/Stat3ΔIEC (○) mice (n=4/group). Results are averages ± SD. *P < 0.05. Mucosal histology of Stat3ΔIEC and villin-gp130Act/Stat3ΔIEC mice (n=4/group) was examined and scored 8 days after 2.0% DSS challenge as above. Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. (b) RNA was extracted from YapΔIEC and villin-gp130Act/YapΔIEC (n=3/group) or Stat3ΔIEC and villin-gp130Act/Stat3ΔIEC (n=4/group) colons, and expression of the indicated mRNA species was measured by qRT-PCR. Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. (c) IEC6 rat intestinal epithelial cells transfected with either empty (EV) or gp130Act expression vector were grown to confluence and starved overnight, and the monolayers were wounded by scratching and treated with DMSO, PP2 (10 μM), AZD1480 (1 μM), verteporfin (1 μg/ml) or DBZ (10 μM). The percent wounded area was calculated by measuring wound closure over time (0 and 24 hours). Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. (n=5). (d) Total cell lysates of IEC6 cells transfected with empty vector (EV) + shluc (control), gp130Act + shluc or gp130Act + shYAP were prepared, and subjected to IB analysis with the indicated antibodies. (e) IEC6 cells transfected with empty vector (EV) + shluc (control), gp130Act + shluc or gp130Act + shYAP were grown to confluence and starved overnight, and the monolayers were wounded by scratching. The percent wounded area was calculated by measuring wound closure over time (0 and 24 hours) (n=5). Results are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05. (f) Schematic representation of the gp130-SFK-YAP-Notch pathway and its function in the injured intestinal epithelium. Scale bars represent 100 μm (a).

Extended Data Table 1.

Elevated P-Src and YAP expression in colonic biopsies from CD patients

Shown are the results from P-Src and YAP IHC analyses, some of whose images are shown in Fig. 4d. Patient characteristics are included.

| Healthy Control | CD patient | |

|---|---|---|

| DN or SP | 11 | 7 |

| DP | 0 | 11 |

| P<0.05 |

| Characteristics of Controls and Patients with Crohn’s Disease | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Crohn’s disease N = 18 |

Controls N = 11 |

|

|

| ||

| Age (years +/− S.D.) | 53.0 +/− 12.2 | 39.6 +/− 13.2 |

|

| ||

| Disease duration (years +/− S.D.) | 14.7 +/− 13.1 | NA |

|

| ||

| Disease phenotype | ||

| Ileocolonic disease | 72% | NA |

| Colonic disease | 28% | |

|

| ||

| TNF antagonist use | 17% | 0% |

|

| ||

| Immune modulator use(azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine) | 17% | 0% |

|

| ||

| 5-Aminosalicylate use | 56% | 0% |

|

| ||

| Steroid use | 5% | 0% |

|

| ||

| Histopathology | ||

| Active chronic colitis | 78% | 0% |

| Inactive chronic colitis | 22% | 0% |

DN or SP: Double negative (DN) staining for P-Src and YAP or single positive (SP) staining of either P-Src or YAP.

DP: Double positive (DP) staining for both P-Src and YAP.

N = number of patients, S.D. = standard deviation, Na = not applicable

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. D. Pan (Johns Hopkins University) and S. Akira (Osaka University) for YapF/F and Stat3F/F mice, respectively. We also thank Drs. D.L. Gumucio (University of Michigan) for a plasmid containing the 12.4-kb Villin promoter, T. Sato (Keio University), H. Clevers (Hubrecht Institute) and Y. Hippo (National Cancer Center Research Institute) for protocols describing intestinal organoid culture, C. Kuo (Stanford University) for R-spondin1-producing cells, D. Huszar (AstraZeneca) for AZD1480, F. Schaper (Otto-von-Guericke-University Magdeburg) for plasmids, L. Eckmann (University of California, San Diego) for advice, A. Umemura, H. Nakagawa, H. Ogata, EJ. Park, GY. Yu, J. Font-Burgada, D. Dhar and J. Kim for providing liver samples, J. Zhao (UCSD Transgenic Mouse and Gene Targeting Core), T. Meerloo and Y. Jones (UCSD Electron Microscopy Facility) L. Gapuz, R. Ly and N. Varki (UCSD Histology Core), D. Aki, N. Hiramatsu, T. Moroishi, Y. Endo, H. Nishinakamura, A. Chang and T. Lee for technical advice and assistance, and Cell Signaling, Santa Cruz Biotechnology and GeneTex for antibodies. This work was supported by Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad and Research Fellowship for Young Scientists from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and a Uehara Memorial Foundation Fellowship, the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research, and the Kanae Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Science to K.T.; a traveling grant NSC-101-2918-I-006-005 and a research grant NSC-103-2320-B-006-032 by National Science Council of Taiwan to L.W.; NIH R00DK088589, FCCC-Temple University Nodal grant, AACR-Landon Innovator Award in Tumor Microenvironment, and the Pew Scholar in Biomedical Sciences Program for S.I.G; CCFA fellowships to P.R.J.; Croucher Foundation and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation to K.W.; by the NIH and the UCSD Digestive Disease Research Center Grant to J.T.C. and W.J.S.; by the Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs to S.B.H.; by the NIH to K.L.G.; and by the NIH and AACR to M.K., who is an American Cancer Society Research Professor and holds the Ben and Wanda Hildyard Chair for Mitochondrial and Metabolic Diseases. We dedicate this work to the memory of our colleague Marty Kagnoff, who introduced some of us to the intricacies of IBD and mucosal immunology.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

K.T. and M.K. conceived the project. K.T., L.W., S.I.G., P.R.J., I.L., F.Y., K.W., G.H. performed the experiments. K.T., L.W., P.R.J, G.H. and M.K. analyzed data. J.Z.-R. provided gp130 mutants, S.B.H., J.T.C., B.S.B. and W.J.S. provided human specimens, S.I.G., E.R., Y.M., A.Y., J.Z.-R. and K.L.G. provided conceptual advice. K.T., L.W. and M.K. wrote the manuscript, with all authors contributing to the writing and providing advice.

References

- 1.Ben-Neriah Y, Karin M. Inflammation meets cancer, with NF-kappaB as the matchmaker. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:715–723. doi: 10.1038/ni.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:428–435. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baddour JA, Sousounis K, Tsonis PA. Organ repair and regeneration: an overview. Birth defects research. Part C, Embryo today : reviews. 2012;96:1–29. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson R, Halder G. The two faces of Hippo: targeting the Hippo pathway for regenerative medicine and cancer treatment. Nature reviews. Drug discovery. 2014;13:63–79. doi: 10.1038/nrd4161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neurath MF. New targets for mucosal healing and therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Mucosal immunology. 2014;7:6–19. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garbers C, et al. Plasticity and cross-talk of interleukin 6-type cytokines. Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2012;23:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kishimoto T. IL-6: from its discovery to clinical applications. International immunology. 2010;22:347–352. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshimura A, Naka T, Kubo M. SOCS proteins, cytokine signalling and immune regulation. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2007;7:454–465. doi: 10.1038/nri2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Putoczki T, Ernst M. More than a sidekick: the IL-6 family cytokine IL-11 links inflammation to cancer. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2010;88:1109–1117. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0410226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose-John S, Mitsuyama K, Matsumoto S, Thaiss WM, Scheller J. Interleukin-6 trans-signaling and colonic cancer associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:2095–2103. doi: 10.2174/138161209788489140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilati C, et al. Somatic mutations activating STAT3 in human inflammatory hepatocellular adenomas. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:1359–1366. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grivennikov S, et al. IL-6 and Stat3 are required for survival of intestinal epithelial cells and development of colitis-associated cancer. Cancer cell. 2009;15:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rebouissou S, et al. Frequent in-frame somatic deletions activate gp130 in inflammatory hepatocellular tumours. Nature. 2009;457:200–204. doi: 10.1038/nature07475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. Therapeutic targeting of the interleukin-6 receptor. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2012;52:199–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai J, et al. The Hippo signaling pathway restricts the oncogenic potential of an intestinal regeneration program. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2383–2388. doi: 10.1101/gad.1978810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okamoto R, et al. Requirement of Notch activation during regeneration of the intestinal epithelia. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2009;296:G23–35. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90225.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu FX, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway: regulators and regulations. Genes & development. 2013;27:355–371. doi: 10.1101/gad.210773.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenbluh J, et al. beta-Catenin-driven cancers require a YAP1 transcriptional complex for survival and tumorigenesis. Cell. 2012;151:1457–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bray SJ. Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2006;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nrm2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madison BB, et al. Cis elements of the villin gene control expression in restricted domains of the vertical (crypt) and horizontal (duodenum, cecum) axes of the intestine. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:33275–33283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Camargo FD, et al. YAP1 increases organ size and expands undifferentiated progenitor cells. Current biology : CB. 2007;17:2054–2060. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou D, et al. Mst1 and Mst2 protein kinases restrain intestinal stem cell proliferation and colonic tumorigenesis by inhibition of Yes-associated protein (Yap) overabundance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:E1312–1320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110428108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fre S, et al. Notch signals control the fate of immature progenitor cells in the intestine. Nature. 2005;435:964–968. doi: 10.1038/nature03589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Es JH, et al. Notch/gamma-secretase inhibition turns proliferative cells in intestinal crypts and adenomas into goblet cells. Nature. 2005;435:959–963. doi: 10.1038/nature03659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato T, Clevers H. Growing self-organizing mini-guts from a single intestinal stem cell: mechanism and applications. Science. 2013;340:1190–1194. doi: 10.1126/science.1234852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sato T, et al. Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature. 2011;469:415–418. doi: 10.1038/nature09637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murakami D, et al. Presenilin-dependent gamma-secretase activity mediates the intramembranous cleavage of CD44. Oncogene. 2003;22:1511–1516. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, et al. YAP-dependent induction of amphiregulin identifies a non-cell-autonomous component of the Hippo pathway. Nature cell biology. 2009;11:1444–1450. doi: 10.1038/ncb1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishioka N, et al. The Hippo signaling pathway components Lats and Yap pattern Tead4 activity to distinguish mouse trophectoderm from inner cell mass. Developmental cell. 2009;16:398–410. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J, Elfiky A, Han M, Chen C, Saif MW. The Role of Src in Colon Cancer and Its Therapeutic Implications. Clinical colorectal cancer. 2014;13:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levy D, Adamovich Y, Reuven N, Shaul Y. Yap1 phosphorylation by c-Abl is a critical step in selective activation of proapoptotic genes in response to DNA damage. Molecular cell. 2008;29:350–361. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azzolin L, et al. YAP/TAZ Incorporation in the beta-Catenin Destruction Complex Orchestrates the Wnt Response. Cell. 2014;158:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sudol M. Yes-associated protein (YAP65) is a proline-rich phosphoprotein that binds to the SH3 domain of the Yes proto-oncogene product. Oncogene. 1994;9:2145–2152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsutsumi R, et al. YAP and TAZ, Hippo signaling targets, act as a rheostat for nuclear SHP2 function. Developmental cell. 2013;26:658–665. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tschaharganeh DF, et al. Yes-associated protein up-regulates Jagged-1 and activates the Notch pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1530–1542 e1512. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y, Hibbs MA, Gard AL, Shylo NA, Yun K. Genome-wide analysis of N1ICD/RBPJ targets in vivo reveals direct transcriptional regulation of Wnt, SHH, and hippo pathway effectors by Notch1. Stem cells. 2012;30:741–752. doi: 10.1002/stem.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu FX, et al. Regulation of the Hippo-YAP pathway by G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell. 2012;150:780–791. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gordon M, et al. The tumor suppressor gene, RASSF1A, is essential for protection against inflammation -induced injury. PloS one. 2013;8:e75483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tamm C, Bower N, Anneren C. Regulation of mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal by a Yes-YAP-TEAD2 signaling pathway downstream of LIF. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:1136–1144. doi: 10.1242/jcs.075796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raz R, Lee CK, Cannizzaro LA, d’Eustachio P, Levy DE. Essential role of STAT3 for embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:2846–2851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taniguchi K, Karin M. IL-6 and related cytokines as the critical lynchpins between inflammation and cancer. Seminars in immunology. 2014;26:54–74. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hedvat M, et al. The JAK2 inhibitor AZD1480 potently blocks Stat3 signaling and oncogenesis in solid tumors. Cancer cell. 2009;16:487–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cordero JB, et al. c-Src drives intestinal regeneration and transformation. The EMBO journal. 2014;33:1474–1491. doi: 10.1002/embj.201387454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takeda K, et al. Enhanced Th1 activity and development of chronic enterocolitis in mice devoid of Stat3 in macrophages and neutrophils. Immunity. 1999;10:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang N, et al. The Merlin/NF2 tumor suppressor functions through the YAP oncoprotein to regulate tissue homeostasis in mammals. Developmental cell. 2010;19:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ootani A, et al. Sustained in vitro intestinal epithelial culture within a Wnt-dependent stem cell niche. Nature medicine. 2009;15:701–706. doi: 10.1038/nm.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holzer RG, et al. Saturated fatty acids induce c-Src clustering within membrane subdomains, leading to JNK activation. Cell. 2011;147:173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu HT, et al. Tie2-R849W mutant in venous malformations chronically activates a functional STAT1 to modulate gene expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2325–2333. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nam JS, Ino Y, Sakamoto M, Hirohashi S. Src family kinase inhibitor PP2 restores the E-cadherin/catenin cell adhesion system in human cancer cells and reduces cancer metastasis. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2002;8:2430–2436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee SH, et al. ERK activation drives intestinal tumorigenesis in Apc(min/+) mice. Nature medicine. 2010;16:665–670. doi: 10.1038/nm.2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu L, Zaloudek C, Mills GB, Gray J, Jaffe RB. In vivo and in vitro ovarian carcinoma growth inhibition by a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor (LY294002) Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2000;6:880–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Katakura K, et al. Toll-like receptor 9-induced type I IFN protects mice from experimental colitis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:695–702. doi: 10.1172/JCI22996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sato T, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sato T, et al. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1762–1772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guma M, et al. Constitutive intestinal NF-kappaB does not trigger destructive inflammation unless accompanied by MAPK activation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:1889–1900. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barker N, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Umemura A, et al. Liver damage, inflammation, and enhanced tumorigenesis after persistent mTORC1 inhibition. Cell metabolism. 2014;20:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mitchell C, Willenbring H. A reproducible and well-tolerated method for 2/3 partial hepatectomy in mice. Nature protocols. 2008;3:1167–1170. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kozak I, et al. A degenerative retinal process in HIV-associated non-infectious retinopathy. PloS one. 2013;8:e74712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]