Abstract

A design space approach was applied to optimize the extraction process of Danhong injection. Dry matter yield and the yields of five active ingredients were selected as process critical quality attributes (CQAs). Extraction number, extraction time, and the mass ratio of water and material (W/M ratio) were selected as critical process parameters (CPPs). Quadratic models between CPPs and CQAs were developed with determination coefficients higher than 0.94. Active ingredient yields and dry matter yield increased as the extraction number increased. Monte-Carlo simulation with models established using a stepwise regression method was applied to calculate the probability-based design space. Step length showed little effect on the calculation results. Higher simulation number led to results with lower dispersion. Data generated in a Monte Carlo simulation following a normal distribution led to a design space with a smaller size. An optimized calculation condition was obtained with 10000 simulation times, 0.01 calculation step length, a significance level value of 0.35 for adding or removing terms in a stepwise regression, and a normal distribution for data generation. The design space with a probability higher than 0.95 to attain the CQA criteria was calculated and verified successfully. Normal operating ranges of 8.2-10 g/g of W/M ratio, 1.25-1.63 h of extraction time, and two extractions were recommended. The optimized calculation conditions can conveniently be used in design space development for other pharmaceutical processes.

Introduction

Danhong injection is a botanical injection used in the treatment of coronary heart disease, angina, myocardial infarction, and cerebral diseases [1]. The injection is made from Salviae miltiorrhizae Radix et Rhizoma (Danshen) and Carthami Flos (Honghua) using unit operations of extraction, concentration, ethanol precipitation, adsorption, etc. The water extraction process of mixed Danshen and Honghua affects both the drug efficacy and the drug safety of the Danhong injection. The optimization of the extraction process will contribute to an increase in the batch-to-batch consistency of the Danhong injection.

Quality by design concept has become an essential part of the modern approach to ensure pharmaceutical product quality [2, 3]. Design space development plays an important role in the implementation of the quality by design concept [4, 5]. To develop a reliable design space, process critical quality attributes (CQAs) and critical process parameters (CPPs) must be identified, and the mathematical models between CPPs and process CQAs must be built. Then, the design space can be calculated and verified. Model building is an important consideration in design space development. Both statistical models and mechanistic models can be used to calculate process design space [6, 7]. However, for the separation processes in the manufacture of botanical drugs, building mechanistic models is usually very difficult because of the complex composition and lack of fundamental physical and chemical data. Therefore, statistical models between CPPs and process CQAs are usually used. Typically, quadratic models containing linear terms, nonlinear terms, and interaction terms are applied. These quadratic models are simple and can be a good approximation of the true relationships. The models can be developed after the design of the experiments (DOE). The response surface DOE such as central composite design and Box-Behnken design are widely used to establish the quadratic models [6, 8–10]. To remove insignificant terms, stepwise regression is usually used in model building. The significance level values in stepwise regression should be selected carefully.

Recently, probability-based design space has come to the forefront because it can provide the assurance of design space to meet all process specifications. Rozet et al. reinterpreted the definition of design space, which was “a multivariate domain of input factors ensuring that critically chosen responses are included within predefined limits with an acceptable level of probability” [11]. Bayesian modeling, bootstrapping techniques, and Monte Carlo simulation are three methods to calculate the probability of meeting the specifications imposed on the CQAs [11]. Peterson et al. gave several examples using the Bayesian predictive method to calculate the probability-based design space [4, 12]. Our group developed design spaces for the ethanol precipitation process [13], the water precipitation process [14], and the extraction process [15] using a Monte Carlo simulation method. The Monte Carlo simulation method was also used successfully in the design space development for several analytical methods [16–19]. In the Monte Carlo simulation, random data following a given distribution will be generated. The data distribution type and simulation number are important factors that may affect the calculation results. However, these calculation parameters have not been published.

In this work, process CQAs and CPPs of the extraction process were selected. Quadratic models were built. Simulation number, calculation step length, data distribution type, and the significance level value of the stepwise regression were optimized in the Monte Carlo simulation. Different simulation results were calculated and compared. The probability-based design space was obtained using the optimized Monte Carlo simulation conditions. Then, the design space was verified. The characteristics of this calculation method are also discussed.

Experimental Section

2.1 Materials and Chemicals

Danshen was purchased from Nepstar Drugstore (Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China). Honghua was purchased from Daily Healthy Drugstore (Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China). No specific permission was required for the field studies described in this paper. The locations are neither privately owned nor protected by the Chinese government. No endangered or protected species were sampled.

Standard substances, including rosmarinic acid, Danshensu, and lithospermic acid, were purchased from Winherb Medical S&T Development Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Salvianolic acid B was purchased from Chengdu Biopurify Phytochemicals Ltd. (Chengdu, Sichuan, China). Hydroxysafflor yellow A was obtained from Aladdin Industrial Inc. (Shanghai, China). Deionized water was produced using an academic water purification system (Milli-Q, Milford, MA, USA). HPLC-grade formic acid was obtained from ROE SCIENTIFIC INC. (Newark, DE, USA). HPLC-grade acetonitrile was purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). HPLC-grade ammonium formate was obtained from Alfa Aesar China (Tianjin, China) Co., Ltd. All materials were used as received without any further purification.

2.2 Procedure

After 45 g of Danshen and 15 g of Honghua were placed in a round bottom flask, water was added. The flask then was heated using a heating jacket (TC-15, Haining Huaxing Instrument Co. Ltd, China). After reflux extraction for a period of time, the extract was collected by filtration. If the extraction number was more than 1, water was then added to the flask after filtration to extract mixed Danshen and Honghua again. The extracts were mixed before the measurement of active ingredient content and dry matter content.

2.3 Design of experiments

In this work, the three parameters of extraction time, extraction number, and the mass ratio of water and material (W/M ratio) were investigated. Table 1 shows the coded and uncoded values of the parameters. The run order is listed in Table 2. The ranges of the three parameters were set based on production experience. After the development of the design space, verification experiments were repeated three times with a reflux time of 1.6 h, W/M ratio of 8.3 g/g, and extraction number of 2.

Table 1. Coded and uncoded values of parameters for experimental design.

| Parameters | Coded values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1 | -0.333 | 0 | 1 | |

| Extraction time, X1 (h) | 0.5 | 1 | — | 2 |

| W/M ratio, X2 (g/g) | 6 | — | 8 | 10 |

| Extraction number, X3 | 1 | — | 2 | 3 |

Table 2. Experimental conditions and results.

| Run order | Parameters | Danshensu yield, Y1 (mg/g Danshen) | Hydroxysafflor yellow A yield, Y2 (mg/g Honghua) | Rosmarinic acid yield, Y3 (mg/g Danshen) | Lithospermic acid yield, Y4 (mg/g Danshen) | Salvianolic acid B yield, Y5 (mg/g Danshen) | Dry matter yield, Y6 (mg/g Material) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X2 | X3 | |||||||

| 1 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 2.114 | 5.822 | 1.610 | 2.229 | 39.76 | 492.3 |

| 2 | 0.5 | 10 | 2 | 1.209 | 5.240 | 2.017 | 2.025 | 40.43 | 466.7 |

| 3 | 0.5 | 8 | 3 | 1.387 | 5.135 | 2.206 | 2.267 | 45.67 | 485.8 |

| 4 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 2.340 | 7.707 | 2.172 | 2.630 | 43.60 | 537.3 |

| 5 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 1.934 | 5.786 | 1.980 | 2.247 | 38.38 | 479.9 |

| 6 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 1.089 | 5.016 | 1.565 | 1.601 | 29.44 | 355.8 |

| 7 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 1.674 | 3.605 | 1.418 | 1.628 | 25.56 | 340.1 |

| 8 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 0.601 | 2.588 | 0.979 | 0.932 | 18.76 | 233.3 |

| 9 | 0.5 | 8 | 1 | 0.596 | 2.990 | 1.431 | 1.235 | 28.13 | 318.3 |

| 10 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 3.983 | 5.719 | 2.060 | 2.714 | 39.61 | 586.0 |

| 11 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 3.380 | 4.458 | 2.057 | 2.488 | 35.75 | 491.7 |

| 12 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 1.715 | 6.755 | 2.035 | 2.183 | 37.97 | 437.6 |

| 13 | 0.5 | 6 | 2 | 0.926 | 3.071 | 1.858 | 1.679 | 36.21 | 386.0 |

| 14 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 1.834 | 6.565 | 2.077 | 2.304 | 39.62 | 485.2 |

| 15 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 3.151 | 3.614 | 1.821 | 2.091 | 30.58 | 458.3 |

2.4 Analytical methods

The components Danshensu, hydroxysafflor yellow A, rosmarinic acid, lithospermic acid, and salvianolic acid B were analyzed by HPLC according to the method reported previously [20]. The method is briefly described as follows. The HPLC system HP 1100 series (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) was equipped with the ChemStation software (Agilent Technologies). The separations were carried out on a ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 column (100 mm × 4.6 mm, 1.8 μm) with a formic acid-500 mmol·L-1 ammonium formate-water solution (0.5:10:90, v/v/v) as mobile phase A and acetonitrile-formic acid solution (100:0.5, v/v) as mobile phase B in a gradient mode at 30°C. The flow rate was 0.5 ml·min-1. The gradient program was as follows: 0–10 min, 2–9% B; 10–13 min, 9–10% B; 13–20 min, 10–17% B; 20–37 min, 17–20% B; 37–47 min, 20–25% B; 47–50 min, 25–80% B. The analytical wavelength was set at 280 nm from 0 min to 15.9 min and at 380 nm from 15.9 min to 17.9 min. The wavelength then was set at 280 nm from 17.9 min to 50 min. Dry matter content of the extracts was determined gravimetrically after hot air drying at 105°C for 3 hours.

2.5 Data processing

Eqs 1 and 2 were used to calculate the dry matter yield (DMY) and the active ingredient yield (ACY), respectively.

| (1) |

where DM is dry matter content, and M is the mass. Subscripts ext and mat refer to extract and material, respectively.

| (2) |

where AC is the active ingredient content and subscript i (i = 1, 2, …, 5) represents Danshensu, hydroxysafflor yellow A, rosmarinic acid, lithospermic acid, and salvianolic acid B, respectively.

The experimental data were analyzed using Design-Expert 8.0.6 software (State-Ease Inc., MN, USA) to obtain response surface models. The mathematical model is shown in Eq 3.

| (3) |

where a0 is a constant, a1, a2, …, a9 are regression coefficients, and Y is a CQA. All the variables were coded before modeling. Insignificant terms were removed using a stepwise regression. The significance levels to remove or add a term were both set to 0.35.

The design space was calculated using a Monte Carlo method with a self-written program of Matlab (R2011b, MathWorks, USA). In the calculations, the uncertainty of the measured data is considered. Random data for the active ingredient content and dry matter content in the supernatant are generated following a given distribution. The given distribution was assumed to be a normal distribution, a lognormal distribution, a square-root-normal distribution, or a reciprocal normal distribution. For the center point, the average value and the corresponding standard deviation value of each process CQA were considered the mean value and standard deviation value of the given distribution. For other experimental points, measured values were considered the mean values in the given distribution. Relative standard deviations (RSDs) of measured data were assumed to be the same as the RSD of the center point. For other experimental points, standard deviation values of the given distribution can then be calculated using the product of the RSD values and the measured values. After the generation of random data for all of the experimental conditions, each data set was applied to develop a model using a stepwise regression. All the models developed were used to predict process CQA values under a given set of conditions. The significance level values were set the same for the move-in and the move-out of model terms. The acceptable level of probability for the design space was set as 0.95. In the investigation of the Monte Carlo simulation conditions, the design space when the extraction number is 2 was calculated as a sample. Two criteria were calculated using coded values of CPPs, namely, average dimensionless size of the design space (ADSS) and the relative standard deviation of the dimensionless design space size (RSDDSS). Calculations were repeated 10 times to obtain the RSDDSS value.

Results and Discussion

3.1 CQA selection

According to the risk assessment results in our previous work [13], the extraction process significantly affects the active ingredient content, fingerprint similarity, and dry matter content of the Danhong injection. Phenolic acids from Danshen such as salvianolic acid B, lithospermic acid, Danshensu, and rosmarinic acid, and flavones from Honghua such as hydroxysafflor yellow A are considered active ingredients of the Danhong injection [21, 22]. These active ingredients can be extracted easily with hot water. However, some active ingredients such as salvianolic acid B or hydroxysafflor yellow A also easily degrade in the extraction process due to hydrolysis or other reactions [23–25]. Accordingly, the yields of active ingredients in the extraction process are prone to fluctuations. Therefore, in this work, the yields of Danshensu, hydroxysafflor yellow A, rosmarinic acid, lithospermic acid, and salvianolic acid B are considered process CQAs. Impurities of saccharides, tannins, pigments, and inorganic salts are extracted simultaneously with the active ingredients, which leads to an increase in dry matter yield. The similarity of fingerprints is affected by both the active ingredient content and the impurity content in injections. Therefore, dry matter yield is considered another process CQA in this work. According to industry experience and literature results [26, 27], the criteria for all of the CQAs were obtained and are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. The control limits for process CQAs.

| CQAs | Lower limit | Upper limit |

|---|---|---|

| Danshensu yield (mg/g Danshen) | 2.0 | 3.8 |

| Hydroxysafflor yellow A yield (mg/g Honghua) | 5.1 | 7.6 |

| Rosmarinic acid yield (mg/g Danshen) | 1.8 | 2.2 |

| Lithospermic acid yield (mg/g Danshen) | 2.1 | 2.6 |

| Salvianolic acid B yield (mg/g Danshen) | 36 | 45 |

| Dry matter yield (mg/g material) | 400 | 550 |

3.2 CPP selection

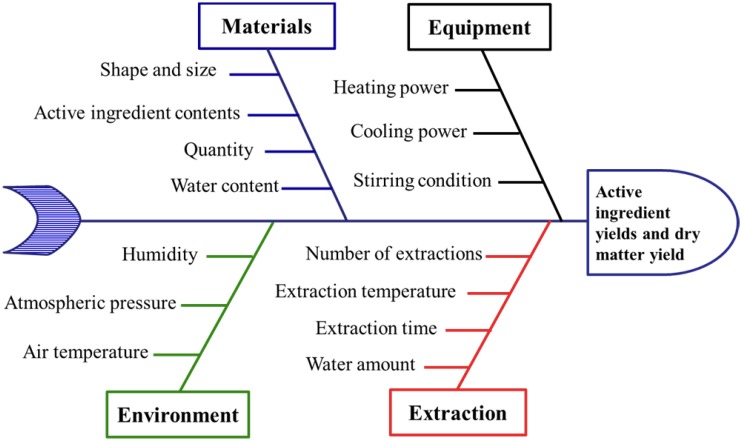

Ishikawa diagram analysis was performed to obtain an initial list of potential factors that affect the results of the extraction process, as shown in Fig 1. Four main causes are involved, including environment, material attributes, equipment, and extraction procedure.

Fig 1. Ishikawa diagram analysis for the extraction process.

Water is the recommended extractant because a higher ethanol content in the mixed ethanol-water solvent results in a lower safflower yellow yield [28]. Extraction time, extraction number, extraction temperature, and solvent amount had a significant impact on safflower yellow yield [28, 29]. Solvent amount, extraction time and extraction number were also considered to be important factors for the extraction of salvianolic acid B from Danshen [30]. Extraction temperature is determined mainly by the solvent composition for reflux extraction at atmospheric pressure. Therefore, the W/M ratio, extraction number, and extraction time are selected as CPPs of the extraction process of Danhong injection.

3.3 Effects of CPPs on CQAs

The experimental results of six CQAs in the extraction process are listed in Table 2. Salvianolic acid B yield was between 18.76 and 45.67 mg/g Danshen, which was much more than that of Danshensu, rosmarinic acid, or lithospermic acid. Rosmarinic acid yield and lithospermic acid yield were lower than 3 mg/g Danshen. Hydroxysafflor yellow A yield varied from 2.588 to 7.707 mg/g Honghua. Dry matter yield values varied from 233.3 to 586.0 mg/g material. Because dry matter yield values are much higher than the sum of the five active ingredient yields, most of the dry matter extracted appeared to be impurities.

In this work, second-order polynomial models were applied to describe the nonlinear effects of parameters. Models were simplified using stepwise regression. The estimated values of the regression coefficients are listed in Table 4. The determination coefficients (R2) are higher than 0.94 for all the models, which means that most variations can be explained by these models. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was applied to determine the impact of the W/M ratio, extraction number, and extraction time on all the CQAs. As shown in Table 4, the linear terms of the W/M ratio and extraction number are significant for all the CQAs. The linear term of extraction time is insignificant for the yields of rosmarinic acid and hydroxysafflor yellow A. For the yields of Danshensu, rosmarinic acid, lithospermic acid, and salvianolic acid B, the quadratic term of the extraction number is very significant because the p values are less than 0.01.

Table 4. Estimated parameter values, ANOVA results for variables and determined coefficients.

| CQAs | Recovery of active ingredients | Dry matter yield | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Danshensu | Hydroxysafflor yellow A | Rosmarinic acid | Lithospermic acid | Salvianolic acid B | ||||||||

| Terms | Estimate | p value | Estimate | p value | Estimate | p value | Estimate | p value | Estimate | p value | Estimate | p value |

| Constant | 2.166 | 6.569 | 2.024 | 2.329 | 38.030 | 474.39 | ||||||

| X1 | 1.012 | < 0.0001* | 0.214 | < 0.0001* | -2.330 | 0.0002* | 26.88 | 0.0052* | ||||

| X2 | 0.153 | 0.0048* | 0.855 | 0.0005* | 0.193 | 0.0004* | 0.227 | < 0.0001* | 2.989 | < 0.0001* | 32.98 | 0.0025* |

| X3 | 0.795 | < 0.0001* | 1.273 | < 0.0001* | 0.332 | < 0.0001* | 0.555 | < 0.0001* | 8.181 | < 0.0001* | 109.65 | < 0.0001* |

| X1X2 | -0.365 | 0.1115 | -13.31 | 0.1836 | ||||||||

| X1X3 | 0.373 | 0.0001* | -0.968 | 0.0736 | 17.50 | 0.0956 | ||||||

| X2X3 | -0.065 | 0.2792 | -0.067 | 0.0698 | -1.709 | 0.0086* | -19.38 | 0.0773 | ||||

| X1 2 | -1.797 | < 0.0001* | 0.059 | 0.3445 | -0.115 | 0.0187 | ||||||

| X2 2 | -0.676 | 0.0148 | -0.145 | 0.0225 | -0.143 | 0.0032* | -2.399 | 0.0018* | -22.12 | 0.0577 | ||

| X3 2 | -0.274 | 0.0015* | -0.409 | 0.0977 | -0.304 | 0.0003* | -0.253 | 0.0001* | -3.402 | 0.0002* | -40.24 | 0.0053* |

| R2 | 0.993 | 0.957 | 0.946 | 0.992 | 0.992 | 0.983 | ||||||

| R2 adj | 0.987 | 0.924 | 0.915 | 0.985 | 0.983 | 0.961 | ||||||

* p < 0.01.

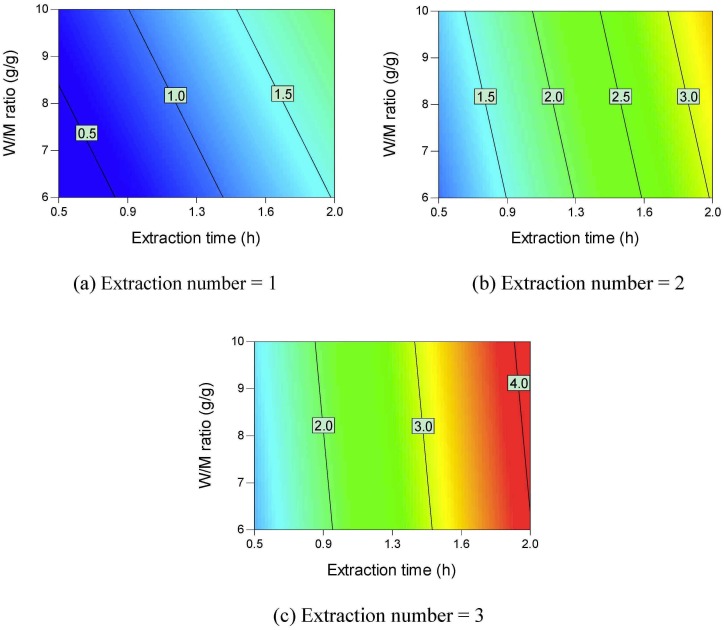

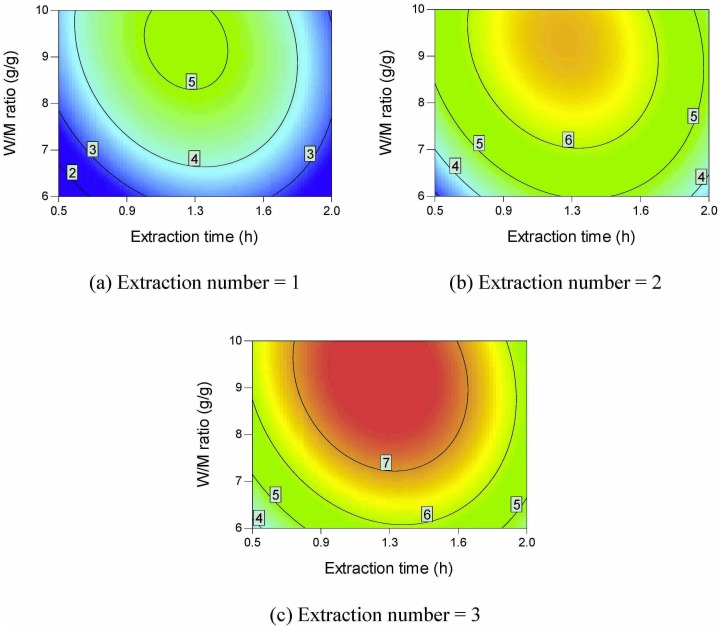

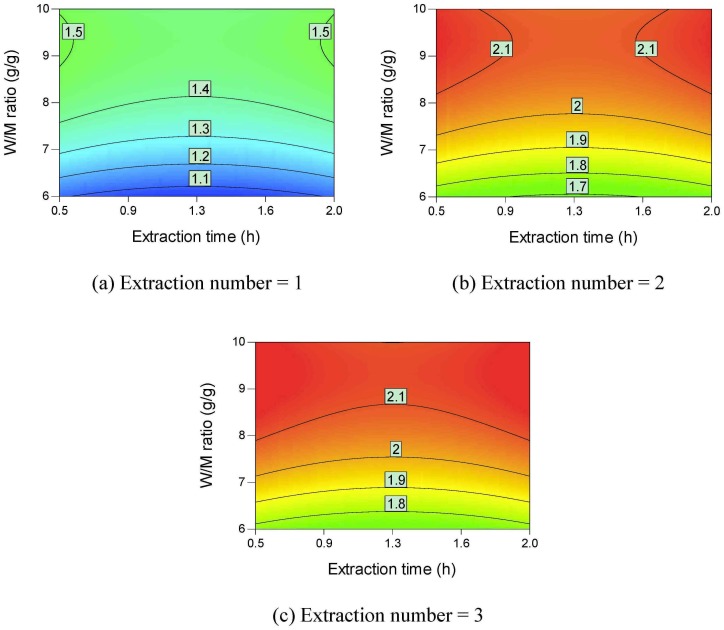

Contour plots of the active ingredient yields are shown in Figs 2–6. All the active ingredient yields increase as the extraction number increases. Danshensu yield, lithospermic acid yield, rosmarinic acid yield, and lithospermic acid yield also increase as the W/M ratio increases. Danshensu and lithospermic acid are two of the hydrolyzates of salvianolic acid B [24, 25]. Accordingly, their yields both increase as extraction time increases, as shown in Fig 2 and Fig 5. Salvianolic acid B will hydrolyze and form many compounds [24, 25]. Therefore, the increase in extraction time results in a lower salvianolic acid yield, as shown in Fig 6. Compared with the degradation rate of salvianolic acid B, the degradation rate of rosmarinic acid is much slower [31]. Hydroxysafflor yellow A is a hydrolyzate of anhydrosafflor yellow B [23]. Hydroxysafflor yellow A can also hydrolyze and form p-coumaric acid [23]. As shown in Fig 3, when extraction time increases, hydroxysafflor yellow A first increases, then decreases.

Fig 2. Contour plots of parameter interactions on Danshensu yield.

Fig 6. Contour plots of parameter interactions on Salvianolic acid B yield.

Fig 5. Contour plots of parameter interactions on lithospermic acid yield.

Fig 3. Contour plots of parameter interactions on hydroxysafflor yellow A yield.

Fig 4. Contour plots of parameter interactions on rosmarinic acid yield.

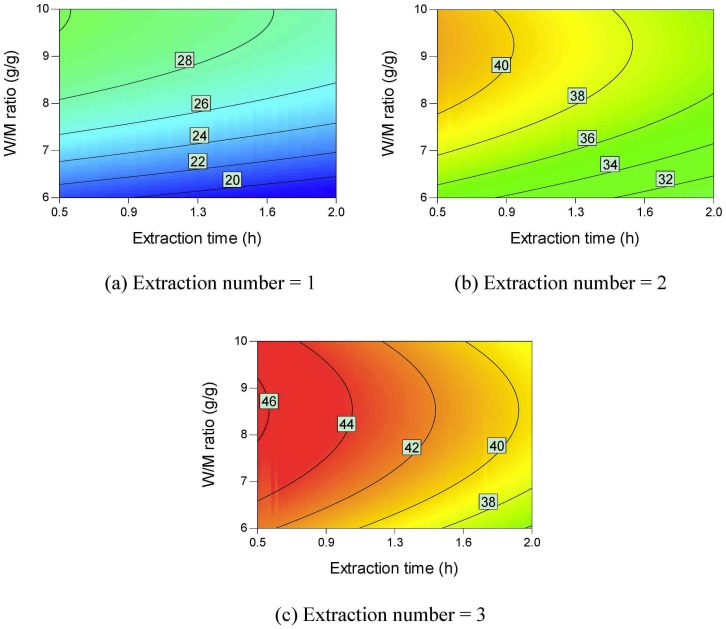

Fig 7 provides the contour plots of parameter interactions on dry matter yield. Dry matter yield increases as the extraction number, W/M ratio, and extraction time increase. Different types of saccharides such as sucrose, fructose, and glucose are found in Danshen [32]. These saccharides are easily soluble in water [33–35]. Phenolic acids usually exist in medicinal plants in their salt forms [36]. The phenolic acids can also be extracted using hot water. Accordingly, the dry matter yield can be higher than 500 mg/g material.

Fig 7. Contour plots of parameter interactions on dry matter yield.

3.4 Design space development

3.4.1 Simulation number and calculation step length

The results for different simulation numbers and calculation step lengths were calculated. The significance level value was 0.15 for both adding and removing a term. Random data were generated following a normal distribution. The results are shown in Table 5. The variations in calculation step length did not affect ADSS values and RSDDSS values. ADSS changes little as simulation number increases. An increase in simulation number led to a smaller RSDDSS, which means that more reliable simulation results can be obtained. When the simulation number was more than 10000, RSDDSS values were less than 0.5%. Therefore, the simulation number was set at 10000, and the calculation step length was set as 0.01 in the following calculations.

Table 5. Effects of simulation number and step length on ADSS and RSDDSS values.

| Simulation number | Calculation step length | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.008 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | ||||||

| ADSS | RSDDSS (%) | ADSS | RSDDSS (%) | ADSS | RSDDSS (%) | ADSS | RSDDSS (%) | ADSS | RSDDSS (%) | |

| 500 | 0.923 | 1.62 | 0.926 | 1.63 | 0.929 | 1.56 | 0.918 | 1.58 | 0.937 | 1.39 |

| 1000 | 0.928 | 1.12 | 0.928 | 1.13 | 0.933 | 1.10 | 0.923 | 1.08 | 0.942 | 0.980 |

| 5000 | 0.925 | 0.530 | 0.926 | 0.520 | 0.930 | 0.590 | 0.921 | 0.570 | 0.939 | 0.500 |

| 10000 | 0.924 | 0.440 | 0.925 | 0.460 | 0.928 | 0.560 | 0.920 | 0.450 | 0.936 | 0.430 |

| 20000 | 0.924 | 0.330 | 0.925 | 0.390 | 0.928 | 0.490 | 0.920 | 0.350 | 0.937 | 0.340 |

| 30000 | 0.924 | 0.230 | 0.924 | 0.290 | 0.927 | 0.410 | 0.921 | 0.190 | 0.937 | 0.260 |

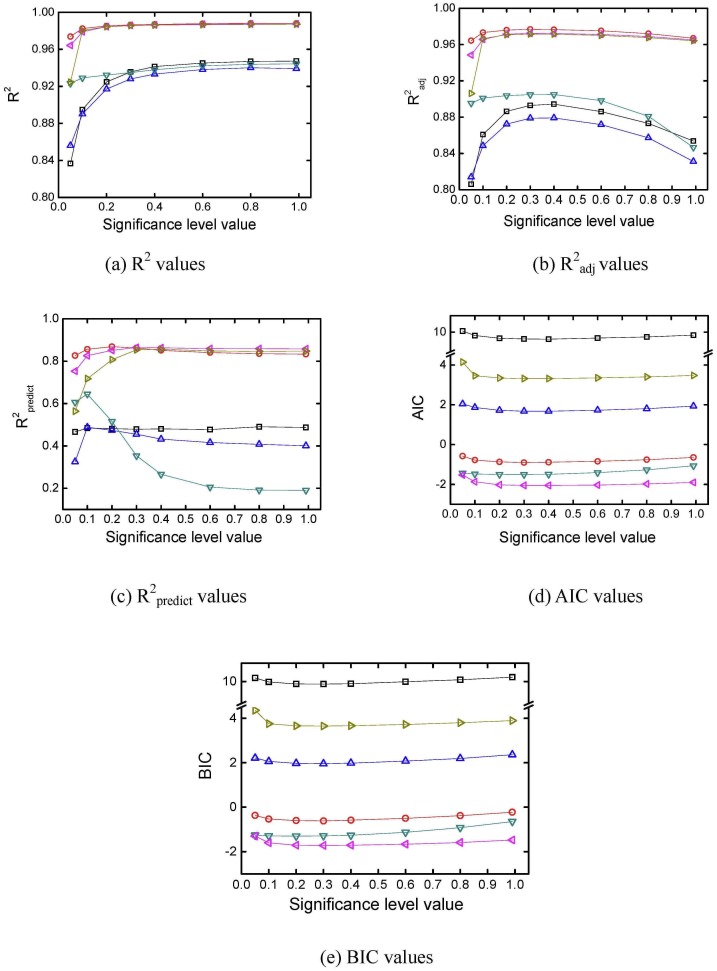

3.4.2 The significance level value in stepwise regression

Different model criteria of R2, the Akaike information criterion, the Bayesian information criterion, R2 predict, and R2 adj were used to evaluate the quadratic models after stepwise regression with different significance level values. The simulation was repeated 10000 times. The average results for R2, the Akaike information criterion, the Bayesian information criterion, R2 predict, and R2 adj were obtained and are plotted in Fig 8. In Fig 8a, average R2 values increase as the significance level value increases for all the models. In Fig 8b and 8c, the average model R2 adj and R2 predict values increase first but then decrease as the significance level value increases. Overfitting occurs when too many terms are included in the models. Average Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion values both decrease first and then increase slightly as the significance level value increases, as shown in Fig 8d and 8e. Higher R2 adj, higher R2 predict, lower Akaike information criterion, or lower Bayesian information criterion values are favored in the selection of models. Because the turning points of average R2 adj, Akaike information criterion, and Bayesian information criterion values were all between 0.3 and 0.4, the significance level in the stepwise regression for adding or removing terms was set as 0.35 in following calculations.

Fig 8. R2, R2 adj, R2 predict, AIC, and BIC values after stepwise regression.

(☐, dry matter yield; ◯, Danshensu yield; △, hydroxysafflor yellow A yield; ▽, rosmarinic acid yield; ⊲, lithospermic acid yield; ⊳, Salvianolic acid B yield).

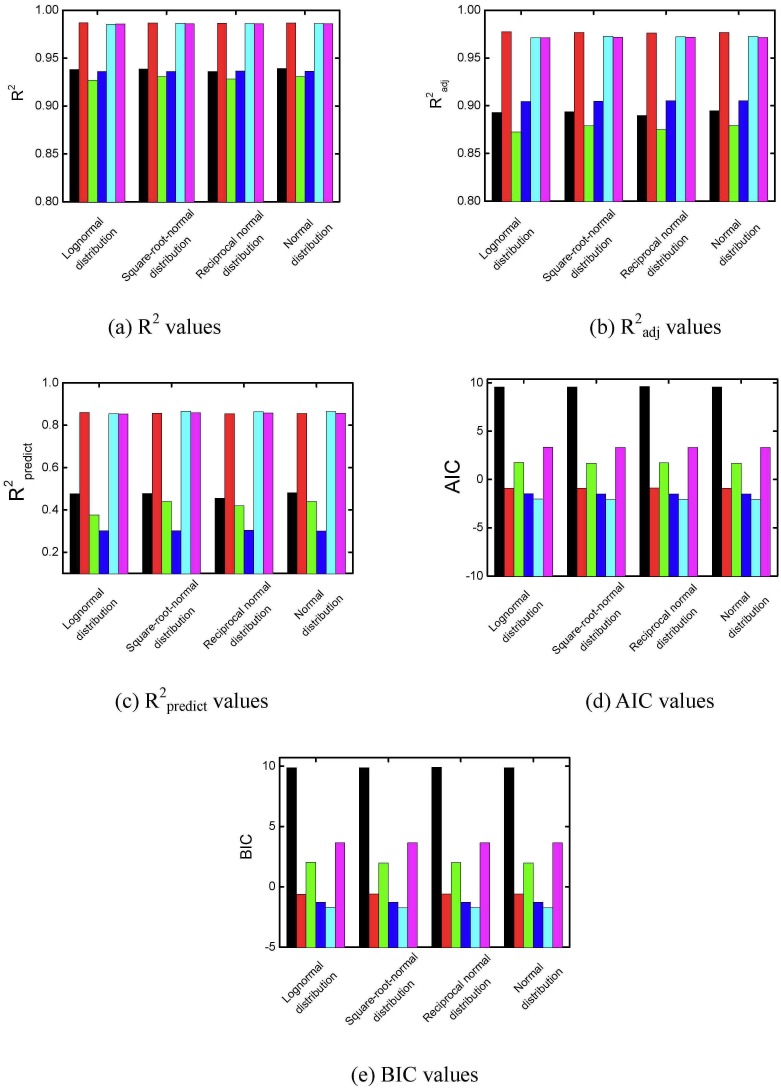

3.4.3 Data distribution type

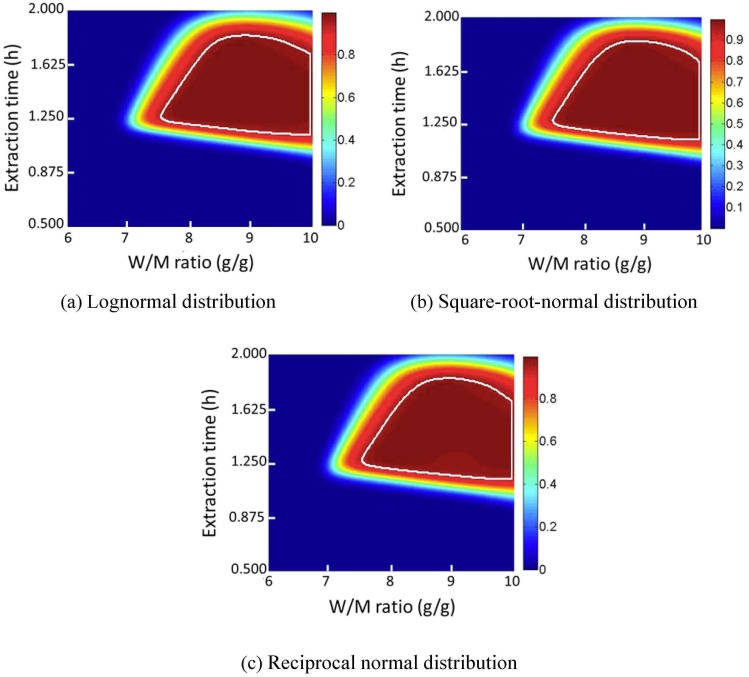

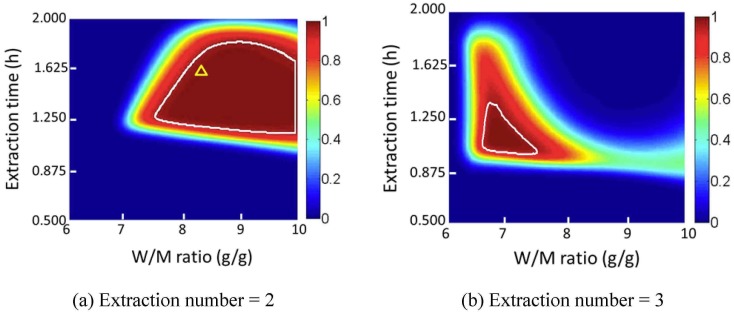

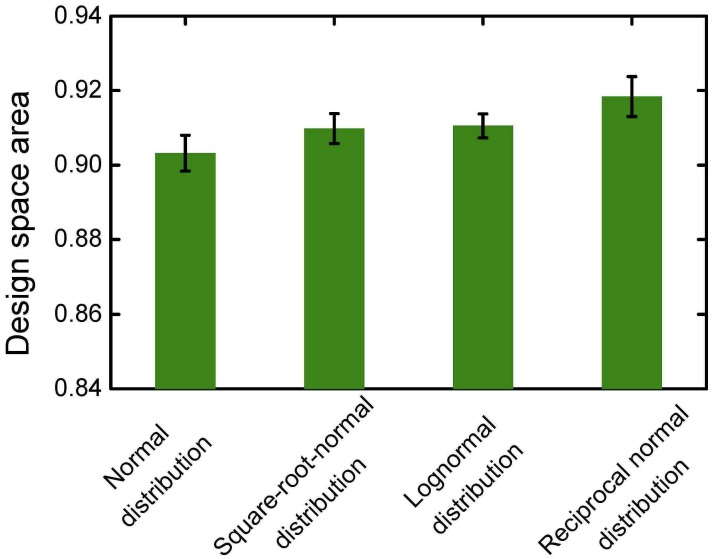

The effects of four different data distribution types on the regression results were investigated, including normal distribution, lognormal distribution, square-root-normal distribution, and reciprocal normal distribution. Average values of R2, R2 adj, R2 predict, the Akaike information criterion and the Bayesian information criterion are compared as evaluation indices. These results are plotted in Fig 9. Different distributions of data also show small effects on the average R2, R2 adj, R2 predict, Bayesian information criterion, and Akaike information criterion values. Design space location and design space area when the extraction number is 2 were also compared as indices. These results are plotted in Figs 10–12. In Figs 10 and 12a, different data distribution types show little influence on the shape and position of the design space. In Fig 11, the smallest design space was obtained when the data distribution was normal. Therefore, normal distribution is favored in design space calculation.

Fig 9. Average values of R2, R2 adj, R2 predict, AIC, and BIC after stepwise regression.

(Black bar, dry matter yield; Red bar, Danshensu yield, Green bar, hydroxysafflor yellow A yield; Blue bar, rosmarinic acid yield; Cyan bar, lithospermic acid yield; Magenta bar, Salvianolic acid B yield).

Fig 10. The position and shape of calculated design space with different data distribution types.

(Color bar refers to the probability to attain CQA criteria; the region within the white line is the design space).

Fig 12. Design space and the verification experiment.

(Color bar refers to the probability to attain CQA criteria; △, verification experiment; the region within the white line is the design space).

Fig 11. Dimensionless design space area after stepwise regression.

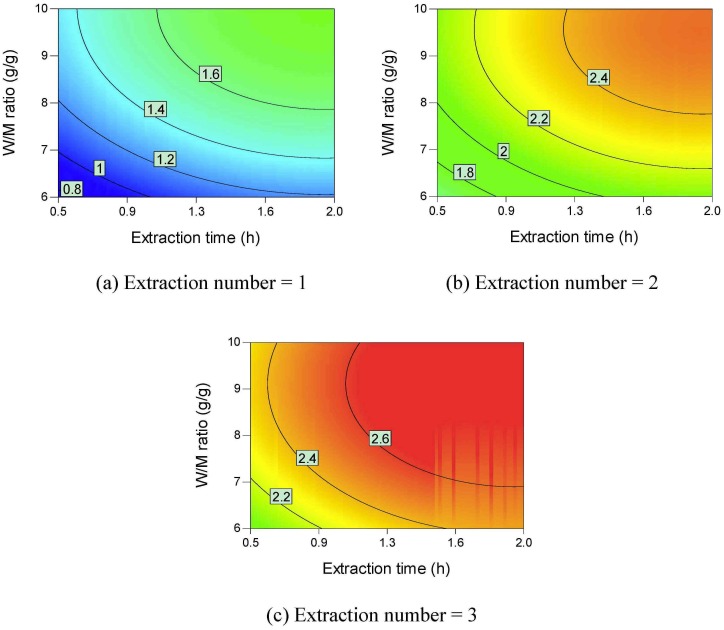

3.4.4 Design space and verification

The optimized Monte Carlo simulation conditions were obtained as follows: the simulation number was 10000; the calculation step length was 0.01; the data were generated following a normal distribution; the significance level used in the stepwise regression was 0.35. The design space can be obtained when the extraction number is 2 or 3, as shown in Fig 12.

Considering the consumption of solvent and time, an extraction number of 2 is recommended. The recommended normal operation range is 8.2–10 g/g of W/M ratio and 1.25–1.63 h of extraction time, with a minimum probability of 0.97 of attaining CQA criteria. Design space was then verified in a larger scale extraction with 360 g of Danshen and 120 g of Honghua used with an extraction number of 2, an extraction time of 1.6 h, and a W/M ratio of 8.3 g/g. The probability of attaining CQA criteria is 0.99 under these conditions, as shown in Fig 12a. The results are listed in Table 6. Most of the experimental results agree well with the prediction results. All the results of the verification experiments are within the limits of the CQAs.

Table 6. Comparison of the predicted values and experimental values.

| CQA | Predicted results | Experimental results | Within CQA limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Danshensu yield (mg/g Danshen) | 2.666 | 3.039 ± 0.031 | Yes |

| Hydroxysafflor yellow A yield (mg/g Honghua) | 6.061 | 5.981 ± 0.075 | Yes |

| Rosmarinic acid (mg/g Danshen) | 2.087 | 1.850 ± 0.109 | Yes |

| Lithospermic acid (mg/g Danshen) | 2.438 | 2.298 ± 0.040 | Yes |

| Salvianolic acid B (mg/g Danshen) | 37.40 | 36.78 ± 0.51 | Yes |

| Dry matter yield (mg/g material) | 480.3 | 474.8 ± 3.3 | Yes |

3.4.5 Discussion of the present calculation method

Compared with the Bayesian method or the bootstrap method, the uncertainty of the measured data is simulated in the present method. This method is easy to understand from the perspective of classical statistics. This method is also promising in design space development for other pharmaceutical processes. However, there are several possible drawbacks. First, new data were generated from a given distribution. The assumptions to obtain the mean value and standard deviation of the given distribution facilitate calculation. However, the generated data are just a rough approximation of the actual situation and will result in some deviations in probability prediction. Second, only the RSD value of the center point is used in calculations when the other experimental conditions are not repeated. If the RSD value of the center point is not occasionally determined correctly, the calculated design space may be affected dramatically. Third, many new data sets are generated in this method. For each data set, a new equation is developed for prediction. Therefore, a large amount of computation is required. An Intel Xeon CPU (E7-4820, 2.00 GHz) was used to calculate the design space, requiring 239 min to complete the calculation at the optimized conditions. A total of 498,000 K of memory was occupied. To obtain more reliable predicted probability, multiple repetitions of the experiments for each condition are suggested to obtain more reliable mean values and standard deviations.

Conclusions

The probability-based design space for the extraction process of the Danhong injection was developed in this work using a Monte Carlo simulation with models built using stepwise regression. The dry matter yield and the yields of Danshensu, rosmarinic acid, lithospermic acid, hydroxysafflor yellow A, and salvianolic acid B were selected as process CQAs. Extraction time, W/M ratio, and extraction number were selected as CPPs. The effects of the CPPs were investigated using a three-level experimental design. After stepwise regression, the R2 values of all the models are higher than 0.94. Hydroxysafflor yellow A yield increases first and then decreases as the extraction time increases. Salvianolic acid B yield decreases as extraction time increases. More active ingredients can be extracted when the extraction number increases. The increase in extraction time, extraction number, and W/M ratio all result in higher dry matter yield. The influence of the calculation step length on calculation results was small. A higher simulation number led to lower dispersion results. The smallest design space was obtained on the assumption of a normal distribution. The optimized Monte Carlo simulation conditions were obtained: normal distribution for concentration data, 10000 times for the simulation, 0.01 for the calculation step length, significance level of 0.35 for adding and removing terms in the model development. The design space for the Danhong extraction process was calculated using these conditions with a probability higher than 0.95 of attaining CQA criteria. Normal operation ranges of 8.2–10 g/g of W/M ratio, 1.25–1.63 h of extraction time, and two extractions were also calculated. Verification experiments were carried out on a larger scale. All the results are within the CQA limits, which means that the calculated design space is accurate. Determination of all the RSD values of results under different conditions is encouraged. With these RSD values used in Monte Carlo simulation, more reliable probability is expected. The use of the present method with optimized conditions to develop design space for other pharmaceutical processes appears to be promising.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81273992) and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (LQ12H29004). Haibin Qu received the first fund. The website is http://www.nsfc.gov.cn/. Xingchu Gong received the second fund. The website is http://www.zjnsf.gov.cn/. Funds were used to buy materials, chemicals, and pay labor costs. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. He Y, Wan HT, Du YG, Bie XD, Zhao T, Fu W, et al. Protective effect of Danhong injection on cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;144(2):387–94. 10.1016/j.jep.2012.09.025 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yu LX. Pharmaceutical quality by design: Product and process development, understanding, and control. Pharm Res-Dordr. 2008;25(4):781–91. 10.1007/s11095-007-9511-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Korakianiti E, Rekkas D. Statistical Thinking and Knowledge Management for Quality-Driven Design and Manufacturing in Pharmaceuticals. Pharm Res-Dordr. 2011;28(7):1465–79. 10.1007/s11095-010-0315-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peterson JJ, Lief K. The ICH Q8 Definition of Design Space: A Comparison of the Overlapping Means and the Bayesian Predictive Approaches. Stat Biopharm Res. 2010;2(2):249–59. 10.1198/sbr.2009.08065 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Conferenceon Harmonization (ICH). Pharmaceutical development. Q8(R2) 2009/4/. Available from: http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Quality/Q8_R1/Step4/Q8_R2_Guideline.pdf.

- 6. Zhang L, Yan BJ, Gong XC, Yu LX, Qu HB. Application of Quality by Design to the Process Development of Botanical Drug Products: A Case Study. Aaps Pharmscitech. 2013;14(1):277–86. 10.1208/s12249-012-9919-8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gétaz D, Butté A, Morbidelli M. Model-based design space determination of peptide chromatographic purification processes. J Chromatogr A. 2013;1284:80–7. 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.01.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu XM, Costa AP, Khan MA, Burgess DJ. Application of quality by design to formulation and processing of protein liposomes. Int J Pharmaceut. 2012;434(1–2):349–59. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.06.002 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nistor I, Lebrun P, Ceccato A, Lecomte F, Slama I, Oprean R, et al. Implementation of a design space approach for enantiomeric separations in polar organic solvent chromatography. J Pharmaceut Biomed. 2013;74:273–83. 10.1016/j.jpba.2012.10.015 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ingvarsson PT, Yang MS, Mulvad H, Nielsen HM, Rantanen J, Foged C. Engineering of an Inhalable DDA/TDB Liposomal Adjuvant: A Quality-by-Design Approach Towards Optimization of the Spray Drying Process. Pharm Res-Dordr. 2013;30(11):2772–84. 10.1007/s11095-013-1096-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rozet E, Lebrun P, Debrus B, Boulanger B, Hubert P. Design Spaces for analytical methods. Trac-Trend Anal Chem. 2013;42:157–67. 10.1016/j.trac.2012.09.007 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peterson JJ. A Bayesian approach to the ICH Q8 definition of design space. J Biopharm Stat. 2008;18(5):959–75. 10.1080/10543400802278197 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gong XC, Li Y, Guo ZT, Qu HB. Control the effects caused by noise parameter fluctuations to improve pharmaceutical process robustness: A case study of design space development for an ethanol precipitation process. Sep Purif Technol. 2014;132:126–37. . [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gong XC, Chen HL, Chen T, Qu HB. Unit Operation Optimization for the Manufacturing of Botanical Injections Using a Design Space Approach: A Case Study of Water Precipitation. Plos One. 2014;9(8). . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gong XC, Zhang Y, Pan JY, Qu HB. Optimization of the Ethanol Recycling Reflux Extraction Process for Saponins Using a Design Space Approach. Plos One. 2014;9(12). . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mbinze JK, Lebrun P, Debrus B, Dispas A, Kalenda N, Mbay JMT, et al. Application of an innovative design space optimization strategy to the development of liquid chromatographic methods to combat potentially counterfeit nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1263:113–24. 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.09.038 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Debrus B, Lebrun P, Ceccato A, Caliaro G, Rozet E, Nistor I, et al. Application of new methodologies based on design of experiments, independent component analysis and design space for robust optimization in liquid chromatography. Anal Chim Acta. 2011;691(1–2):33–42. 10.1016/j.aca.2011.02.035 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nistor I, Cao M, Debrus B, Lebrun P, Lecomte F, Rozet E, et al. Application of a new optimization strategy for the separation of tertiary alkaloids extracted from Strychnos usambarensis leaves. J Pharmaceut Biomed. 2011;56(1):30–7. 10.1016/j.jpba.2011.04.027 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Debrus B, Lebrun P, Kindenge JM, Lecomte F, Ceccato A, Caliaro G, et al. Innovative high-performance liquid chromatography method development for the screening of 19 antimalarial drugs based on a generic approach, using design of experiments, independent component analysis and design space. J Chromatogr A. 2011;1218(31):5205–15. 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.05.102 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li Y, Guo Z, Gong X, Qu H. Simultaneous determination of danshensu, hydroxysafflor yellow A, rosmarinic acid, lithospermic acid, salvianolic acid B in water extract of mixed Salviae Miltiorrhizae Radix et Rhizoma and Carthami Flos by HPLC. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2013;38(11):1653–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu HT, Wang YF, Olaleye O, Zhu Y, Gao XM, Kang LY, et al. Characterization of in vivo antioxidant constituents and dual-standard quality assessment of Danhong injection. Biomed Chromatogr. 2013;27(5):655–63. 10.1002/Bmc.2842 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xu ZH, Li JS, Zhou JX. Process Development for Robust Removal of Aggregates Using Cation Exchange Chromatography in Monoclonal Antibody Purification with Implementation of Quality by Design. Prep Biochem Biotech. 2012;42(2):183–202. 10.1080/10826068.2012.654572 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fan L, Pu R, Zhao HY, Liu X, Ma C, Wang BR, et al. Stability and degradation of hydroxysafflor yellow A and anhydrosafflor yellow B in the Safflower injection studied by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn . Journal of Chinese Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2011;20:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guo YX, Zhang DJ, Wang H, Xiu ZL, Wang LX, Xiao HB. Hydrolytic kinetics of lithospermic acid B extracted from roots of Salvia miltiorrhiza. J Pharmaceut Biomed. 2007;43(2):435–9. 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.07.046 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pan JY, Gong XC, Qu HB. Quantitative H-1 NMR method for hydrolytic kinetic investigation of salvianolic acid B. J Pharmaceut Biomed. 2013;85:28–32. 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.06.020 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yan B, Liu S, Guo Z, Huang S, Qu H. [Application of ultraviolet spectroscopy for rapid analysis in extraction process of danhong injection]. Zhongguo Zhong yao za zhi = Zhongguo zhongyao zazhi = China journal of Chinese materia medica. 2013;38(11):1676–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu S, Li W, Qu H, Zhao B, Zhao T. [On-line monitoring of extraction process of danhong injection based on near-infrared spectroscopy]. Zhongguo Zhong yao za zhi = Zhongguo zhongyao zazhi = China journal of Chinese materia medica. 2013;38(11):1657–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chu Y, Song H-t, Chen D-w, Li D, Luo Y-f. Extracting process for safflower yellow in Carthamus tinctorius. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs. 2006;37(8):1161–4. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gu J, An L-y, Liu J-k, Chen X-z. The Optimal Technology for Extraction of Safflower Yellow by Water. Guangdong Weiliang Yuansu Kexue. 2005;12(11):61–3. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Du Z-l, Cheng Z-t. Optimization of the Extraction Technology of Salvianolic Acid B from Salvia miltiorrhiza by Orthogonal Experiment. China Pharmacy. 2010;21(31):2911–2. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ren X, Cui M, Pu W, Ma S, Qi A. Degradation Kinetics Analysis of Main Ingredients in Salvianolate Lyophilized Injection. Chinese Journal of Experimental Traditional Medical Formulae. 2013;19(14):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li HL, Song FR, Zheng Z, Liu ZQ, Liu SY. Characterization of saccharides and phenolic acids in the Chinese herb Tanshen by ESI-FT-ICR-MS and HPLC. J Mass Spectrom. 2008;43(11):1545–52. 10.1002/Jms.1441 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bouchard A, Hofland GW, Witkamp GJ. Properties of sugar, polyol, and polysaccharide water-ethanol solutions. J Chem Eng Data. 2007;52(5):1838–42. 10.1021/Je700190m . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gong XC, Wang SS, Qu HB. Solid-Liquid Equilibria of D-Glucose, D-Fructose and Sucrose in the Mixture of Ethanol and Water from 273.2 K to 293.2 K. Chinese J Chem Eng. 2011;19(2):217–22. . [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tsavas P, Voutsas E, Magoulas K, Tassios D. Phase equilibrium calculations in aqueous and nonaqueous mixtures of sugars and sugar derivatives with a group-contribution model. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2004;43(26):8391–9. 10.1021/Ie049353n . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gong XC, Wang SS, Qu HB. Comparison of Two Separation Technologies Applied in the Manufacture of Botanical Injections: Second Ethanol Precipitation and Solvent Extraction. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2011;50(12):7542–8. . [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.