Abstract

The clinical symptoms and cognitive and functional deficits of schizophrenia typically begin to gradually emerge during late adolescence and early adulthood. Recent findings suggest that disturbances of a specific subset of inhibitory neurons that contain the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin (PV), which may regulate the course of postnatal developmental experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in the cerebral cortex, including the prefrontal cortex (PFC), may be involved in the pathogenesis of the onset of this illness. Specifically, converging lines of evidence suggest that oxidative stress, extracellular matrix (ECM) deficit and impaired glutamatergic innervation may contribute to the functional impairment of PV neurons, which may then lead to aberrant developmental synaptic pruning of pyramidal cell circuits during adolescence in the PFC. In addition to promoting the functional integrity of PV neurons, maturation of ECM may also play an instrumental role in the termination of developmental PFC synaptic pruning; thus, ECM deficit can directly lead to excessive loss of synapses by prolonging the course of pruning. Together, these mechanisms may contribute to the onset of schizophrenia by compromising the integrity, stability, and fidelity of PFC connectional architecture that is necessary for reliable and predictable information processing. As such, further characterization of these mechanisms will have implications for the conceptualization of rational strategies for the diagnosis, early intervention, and prevention of this debilitating disorder.

Keywords: Cerebral cortex, Critical period, Dendritic spines, Extracellular matrix, GABA, Gamma band oscillation, Oxidative stress, Parvalbumin, Schizophrenia, Synaptic pruning

Schizophrenia is a complex, prevalent, and extremely debilitating brain disorder affecting approximately 1% of the population worldwide. It is defined by a constellation of positive (i.e., delusions and hallucinations) and negative (i.e., affective flattening, avolition, alogia, anergia, and anhedonia) symptoms. In addition, patients exhibit prominent cognitive deficits, such as disturbances in executive functions, working memory, and attention. Together, these symptoms and cognitive deficits render the individuals inflicted with the illness a life-long course of intellectual, vocational, interpersonal and social impairment. At present, antipsychotic medications provide some symptomatic relief in some but not all patients, but they do not appear to impact the course or the long-term outcome of the illness in any meaningful fashion (Woo et al. 2009). The current lack of truly effective treatment, in no small part, is because after decades of research the pathophysiological basis of schizophrenia remains poorly understood.

It has long been known that the onset of schizophrenia typically occurs during the period of late adolescence and early adulthood. In recent years, there has been growing emphasis in the field in identifying the clinical characteristics that immediately precede the onset of full-blown illness (McGorry 2005). The underlying concept is that timely intervention during this critical phase of the pathogenetic process could attenuate or perhaps even prevent the onset of overt symptoms and deficits. Although this line of research has evoked significant optimism and enormous excitement, reliable methods to faithfully predict who will ultimately develop symptoms and deficits do not yet exist. Perhaps more importantly, it is far from clear as to what preventative or early intervention strategies would be effective. The single most significant impediment is that the neurobiological mechanisms that mediate the onset of illness are at present virtually unknown.

The period of adolescence is a time of profound changes, when the highest-order cognitive functions, such as reasoning, abstract thinking, and planning, gradually achieve maturation (Goldman-Rakic 1987; Andersen 2003). This maturational process is thought to reflect the coming online of the executive brain system of the cerebral cortex, orchestrated in large part by the maturation of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) via extensive pruning of excitatory synapses, dendritic spines on pyramidal neurons on which these synapses form, and axon terminals of pyramidal neurons that are presynaptic to these synapses (Bourgeois et al. 1994; Goldman-Rakic et al. 1997; Huttenlocher 2002). This connectional pruning process is associated with the maturation of the capacity of PFC pyramidal neuronal networks to oscillate and synchronize, especially in the gamma (i.e., 30–80 Hz) frequency band (Uhlhaas et al. 2009, 2010). In addition, gamma band oscillation appears to be an electrophysiological correlate of working memory (Roux et al. 2012), a core PFC function that is required for the integrity of executive functioning (Tallon-Baudry and Bertrand 1999; Salinas and Sejnowski 2001; Howard et al. 2003; Cho et al. 2006). Interestingly, in patients with schizophrenia, working memory and executive functioning are compromised (Park and Holzman 1992; Glahn et al. 2003) and gamma band oscillation has repeatedly been shown to be impaired (Spencer et al. 2003; Cho et al. 2006; Uhlhaas and Singer 2010; Woo et al. 2010).

The fact that many of the symptoms and cognitive deficits of schizophrenia typically begin to emerge during late adolescence and early adulthood has long led to the hypothesis that disturbances of the synaptic pruning process that occurs in the PFC during this period may play a role in triggering the onset of illness (Feinberg 1982; Keshavan et al. 1994; McGlashan and Hoffman 2000), although the specific neurobiological mechanisms that underlie the presumed synaptic pruning disturbances have not been systematically formulated. This is in large part due to the fact that, for a long time, the biological determinants of this synaptic pruning process were completely unknown. However, recent studies in rodents have identified the maturation of intracortical inhibition subserved by the parvalbumin (PV)-containing inhibitory neurons and the formation of extracellular matrix (ECM) environment as two important mechanisms that regulate the time course of the critical period for developmental synaptic plasticity in the cerebral cortex (Hockfield et al. 1990; Hanover et al. 1999; Huang et al. 1999; Hensch 2005b; Sugiyama et al. 2009; Maeda et al. 2010). Interpretation of these findings in the context of our current understanding of neuronal type-specific regulation of gamma band oscillation (Soltesz 2005; Buzsaki 2006; Traub and Whittington 2010) and PFC circuit dysfunction in schizophrenia (Benes and Berretta 2001; Costa et al. 2004; Lewis et al. 2005; Gonzalez-Burgos et al. 2010; Lewis 2011) allows us to begin to develop specific, experimentally testable hypotheses of the neurobiology of developmental synaptic pruning in the human PFC and the possible pathophysiological mechanisms of schizophrenia onset. Specifically, it is postulated that the inhibitory neurons that contain PV may play a central role in regulating the time course of PFC synaptic pruning during late adolescence and early adulthood and that disturbances of PV neurons may lead to aberrant loss of synapses and thereby cortical circuitry instability, hence triggering the onset of schizophrenia (Woo et al. 2010). In this review, we discuss the possible pathophysiological mechanisms that may contribute to the dysfunction of PV neurons in schizophrenia, focusing on deficient glutamatergic innervation, oxidative stress and impaired formation of ECM structures called perineuronal nets (PNNs) (Behrens and Sejnowski 2009; Do et al. 2009; Bitanihirwe and Woo 2011; Berretta 2012).

1 Onset of Schizophrenia Occurs During Late Adolescence and Early Adulthood

Although there has long been evidence suggesting that prenatal or perinatal insults, such as infection, malnutrition, and hypoxia, may play a role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia (Lewis and Levitt 2002), the overt symptomatology of the illness do not typically become clinically apparent until late adolescence and early adulthood. To this end, disturbances of developmental events occurring during this period, such as synaptic pruning in the PFC, have been suggested to be a trigger of the onset of illness (Feinberg 1982; Keshavan et al. 1994; McGlashan and Hoffman 2000). In other words, although the pathogenetic trajectory of schizophrenia may begin as early as during the period of prenatal or perinatal brain development, events that take place a decade or so later during late adolescence and early adulthood may either unmask this aberrant developmental trajectory or, in a non-mutually exclusive fashion, directly trigger disease onset (Weinberger 1987). In this context, modulation of these periadolescent events has the potential of preventing or at the very least attenuating the full-blown onset of illness, regardless of when the pathogenetic trajectory actually begins to diverge from the path of normal brain development (Woo and Crowell 2005).

2 Synaptic Connectivities in the PFC are Deficient in Schizophrenia

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that the number and integrity of synaptic connectivities in the cerebral cortex are deficient in schizophrenia. For instance, it has been shown that the volume of the neuropil, but not the number of neurons, is decreased in the PFC in subjects with schizophrenia (Selemon and Goldman-Rakic 1999). Furthermore, expression of synaptic vesicle proteins in the cerebral cortex, such as synaptophysin (Eastwood et al. 1995; Glantz and Lewis 1997), synaptosomal-associated protein-5 (Honer et al. 2002; Halim et al. 2003), Rab3 (Davidsson et al. 1999), complexin (Sawada et al. 2002), and vesicle-associated membrane protein (Halim et al. 2003), has also been found to be decreased. Similarly, microarray studies have shown that, in the PFC, the expression of many genes that regulate synaptic structure and function are downregulated in subjects with schizophrenia (Mirnics et al. 2000; Hakak et al. 2001; Vawter et al. 2001; Pongrac et al. 2002; Lehrmann et al. 2003). Finally, there has been evidence suggesting that in the PFC connectivities within layer 3 may be preferentially compromised (Lewis 1995; Lewis and Anderson 1995; Lewis and Gonzalez-Burgos 2000; Woo et al. 2004). For example, the density of dendritic spines and branches on layer 3, but not layer 5 pyramidal cells appears to be reduced in subjects with schizophrenia (Garey et al. 1998; Glantz and Lewis 2000; Kalus et al. 2000). Consistent with these findings, the somal area of layer 3 pyramidal cells (Pierri et al. 2001) and the number of glutamatergic axon terminals in this layer, as visualized by vGluT1 (vesicular glutamate transporter 1) immunohistochemistry, have also been shown to be decreased in schizophrenia subjects (Bitanihirwe et al. 2009). Because layer 3 pyramidal neurons furnish corticocortical connections that link the PFC to other cortical regions and because such large-scale networks are critical for the integrity of cognitive and perceptive functioning, disturbances of information processing carried out by circuits subserved by these neurons may contribute to a wide range of symptoms and cognitive deficits of the illness.

3 PFC Neural Circuits are Refined by Synaptic Pruning During Late Adolescence and Early Adulthood

The primate cerebral cortex gradually achieves maturation during late adolescence and early adulthood (Goldman-Rakic et al. 1997; Lewis 1997). During this period, the densities of glutamatergic synapses and dendritic spines on pyramidal neurons in the PFC in both humans and monkeys are decreased by ~50 % (Anderson et al. 1995; Goldman-Rakic et al. 1997; Huttenlocher 2002). Furthermore, in the PFC in monkeys, neural circuits furnished by layer 3 pyramidal neurons undergo large-scale pruning of axonal arbors (Woo et al. 1997). Imaging studies have shown that gray matter volume of the human cerebral cortex, including the prefrontal, parietal, and temporal cortices, undergoes significant attrition through the period of late adolescence and early adulthood (Sowell et al. 2001; Gogtay et al. 2004; Shaw et al. 2008), which is commonly interpreted as a reflection of the underlying ultrastructural process of synaptic, dendritic spine, and axonal pruning.

4 Possible Mechanisms of Synaptic Pruning During Normal Postnatal PFC Development

4.1 Maturation of PV Neurons May Regulate PFC Synaptic Pruning

Findings of recent studies in rodents have led to the increasing appreciation that maturation of inhibitory neural circuits plays a crucial role in defining the onset and possibly also the duration of the critical period for developmental synaptic plasticity in the cerebral cortex (Kirkwood et al. 1995; Huang et al. 1999; Berardi et al. 2000; Hensch 2003; Jiang et al. 2005; Di Cristo 2007). For example, evoked γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) currents gradually increase postnatally, which temporally coincides with the critical period for synaptic plasticity (Berardi et al. 2000). Furthermore, by examining mutants for various GABA receptor subunits, it has been determined that the GABAA alpha 1 subunit, which is preferentially localized to synapses formed by basket cells, a subset of perisomatically targeting inhibitory neurons that express PV (Gao et al. 1993; Gao and Fritschy 1994; Klausberger et al. 2002), is essential for the induction of critical period (Fagiolini et al. 2004). The notion that PV cells play a key role in regulating critical period is also supported by the observation that dark rearing, which prolongs the duration of critical period and delays the functional maturation of the visual cortex, is associated with a significant downregulation of PV mRNA expression (Tropea et al. 2006). Interestingly, these effects of dark rearing can be rescued by overexpression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Gianfranceschi et al. 2003) and, in transgenic mice in which BDNF is overexpressed, the functional maturation of PV neurons is accelerated, which is accompanied by the precocious termination of critical period (Hanover et al. 1999; Huang et al. 1999). In the barrel cortex in mice, the maturation of PV neurons coincides with the time course of critical period, and the maturation of these neurons is arrested in BDNF (−/−) animals (Itami et al. 2007). Finally, it has been directly demonstrated that optimization of somatic inhibition provided by basket cells plays a key role in the onset of critical period (Katagiri et al. 2007). Taken together, these observations strongly suggest that inhibitory circuits mediated by PV neurons play a central role in regulating postnatal developmental synaptic plasticity in the cerebral cortex in rodents.

In monkeys, BDNF expression in the PFC increases during postnatal development and peaks during the periadolescent period (Huntley et al. 1992; Webster et al. 2002), when PV neurons gradually achieve functional maturation (Anderson et al. 1995). In addition, the expression of the GABAA receptor alpha 1 and 2 subunits, which are preferentially localized to synapses formed by PV-containing basket and chandelier neurons, respectively, undergoes significant changes during adolescence (Cruz et al. 2003; Hashimoto et al. 2009). Together these observations raise the possibility that similar inhibitory mechanisms that regulate the timing of the critical period for synaptic plasticity in the rodent cortex may also govern the maturation of the primate PFC through the period of adolescence until young adulthood. One aspect of the functional properties of PV neurons that is of particular interest is their preferential expression of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) class of glutamate receptors, because activation of these receptors plays an essential role in sustained neuronal activation during working memory (Wang 1999, 2001, 2002; Kinney et al 2006; Durstewitz and Gabriel 2007). Conversely, ablation of NMDA receptors on PV neurons impairs gamma band synchrony and working memory (Korotkova et al. 2010). Furthermore, in the rodent PFC, NMDA neurotransmission on PV neurons undergoes maturation during the periadolescent period (Wang and Gao 2009), which may provide a physiological foundation for the maturation of working memory. So far, the time course of the development of NMDA receptors on PV neurons in the primate PFC is unknown.

PV neurons are a principal recipient of dopaminergic inputs to the PFC (Sesack et al. 1998) and, in monkeys, they preferentially express the dopamine D1 receptor (Muly et al. 1998). Furthermore, dopaminergic innervation of the monkey PFC, as visualized by tyrosine hydroxylase histochemistry, undergoes a process of overproduction followed by pruning during adolescence (Rosenberg and Lewis 1995). The expression of the D1 receptor follows a very similar course of postnatal maturation (Lidow and Rakic 1992), although how the neuronal localization of D1 receptor is developmentally regulated is unknown. By virtue of the fact that D1 receptor plays a critical role in working memory by mediating sustained neuronal firing (Williams and Castner 2006), the maturation of D1 expression in PV cells may be one of the key players in the emergent ability of PFC circuitry to engage in gamma oscillatory synchrony during late postnatal development (Uhlhaas et al. 2009, 2010).

4.2 Developmental Formation of PNNs May Terminate PFC Synaptic Pruning

Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) are the main lectican component of ECM in the brain (Lander et al. 1998; Yamaguchi 2000; Matthews et al. 2002; Deepa et al. 2006; Hynes and Yamada 2012). CSPGs, together with other ECM components, including hyaluronic acid, link proteins, and the glycoprotein tenascin-R, form PNNs, which are mesh-like lattice structures that enwrap the cell bodies and dendrites of neurons, including PV neurons and many pyramidal neurons (Bruckner et al. 1993; Celio and Chiquet-Ehrismann 1993; Celio and Blumcke 1994; Dityatev and Schachner 2003; Carulli et al. 2006; Frischknecht and Seidenbecher 2008; Giamanco and Matthews 2012). PNNs are thought to serve as a buffer for cations in the ECM; as such, in the case of PV neurons, PNNs may facilitate their fast-spiking firing (Hartig et al. 1999) and hence indirectly promote the maturation of gamma band oscillation. Therefore, deficit of PNNs can lead to the dysfunction of PV neurons and thereby gamma band oscillation disturbances. In addition, because PNNs may also play an important role in maintaining the integrity of the connectional architecture of pyramidal cell network by regulating synaptic plasticity (Galtrey and Fawcett 2007; Dityatev et al. 2010; Wlodarczyk et al. 2011), PNN deficit can directly destabilize synaptic connectivities and thereby contribute to cortical circuitry dysfunction in schizophrenia (Berretta 2012; Pantazopoulos et al 2010; Mauney et al. 2013).

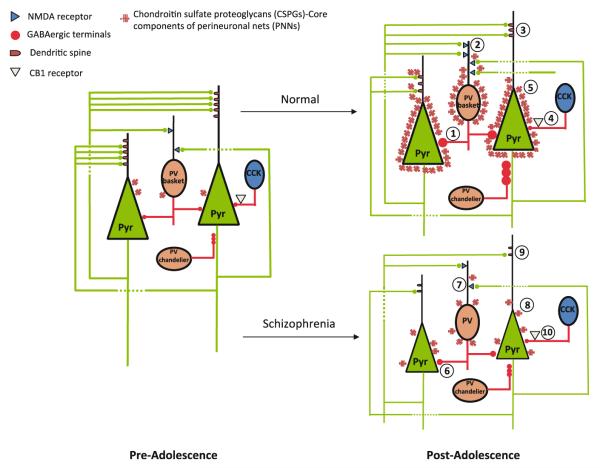

Studies in animals have revealed that PNNs in the cerebral cortex are developmentally regulated. For instance, in the visual cortex, the number of PNNs gradually increases during postnatal development, which temporally parallels the critical period of developmental synaptic plasticity (Galtrey and Fawcett 2007; Gundelfinger et al. 2010). In fact, it has been suggested that the maturation of PNNs may determine the closure of critical period (Pizzorusso et al. 2002; Hensch 2005b; Frischknecht and Gundelfinger 2012; Miyata et al. 2012), whereas dissolution of PNNs in the adult cortex by tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) reactivates the molecular machinery of synaptic plasticity (Mataga et al. 2002; Pizzorusso et al.2002; Hensch 2005a; Galtrey and Fawcett 2007). Interestingly, during postnatal development, tPA level first rises, and then declines, which signals critical period closure (Mataga et al. 2002, 2004; Hensch 2005a). Taken together, it appears that developmental increase in PNN formation, together with the reduction in tPA availability, stabilizes synaptic connectional architecture, possibly by anatomically constraining synaptic modification. Recently, we have found that the number of PNNs in the human PFC appears to undergo a prolonged course of increase, beginning during childhood through late adolescence and early adulthood (Fig. 1; Mauney et al. 2013), raising the possibility that PNNs are likely to also play an important role in regulating the closure of PFC synaptic pruning in humans.

Fig. 1.

Postnatal development of perineuronal nets (PNNs) in the human PFC. a Photomicrographs demonstrating the increase in PNNs in the PFC during postnatal development. b Linear regression analysis indicates statistically significant effect of age on PNN density in the entire PFC (R2 = 0.45, p = 0.0017) and in layer 3 (R2 = 0.49, p = 0.0008), suggesting that the density of PNNs in the PFC undergoes a prolonged course of progressive increase during postnatal development through adolescence and early adulthood. However, the nonlinear hyperbolic regression models appear to be a better fit of the data (R2 = 0.71 and 0.76 for the entire PFC and layer 3, respectively); these models suggest that PNN density increases during postnatal development with the most pronounced changes occurring around the peripubertal period. These findings were derived from postmortem human brains from 19 healthy control subjects obtained from the National Institute of Child and Human Development Brain and Tissue Bank at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, MD. Figure modified from Mauney et al. (2013)

5 PV Neurons are Functionally Disturbed in Schizophrenia

Multiple lines of evidence strongly suggest that inhibitory local circuit neurons in the cerebral cortex are functionally impaired in schizophrenia (Keverne 1999; Benes 2000; Lewis 2000; Benes and Berretta 2001; Costa et al. 2004). Subsets of these neurons regulate distinct aspects of information processing (Gabbott and Bacon 1996; Kawaguchi and Kubota 1997; Kawaguchi and Kondo 2002; Wang et al. 2004). For example, those that contain PV provide perisomatic (basket cells) and axo-axonic (chandelier cells) inhibition to pyramidal cells. In the PFC in schizophrenia, the expression of the mRNA for 67 kD isoform of the GABA synthesizing enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD)67 is undetectable in ~45 % of PV neurons (Hashimoto et al. 2003), suggesting that inhibition furnished by PV neurons is reduced, although it remains unknown whether this reduction reflects a primary disturbance of GAD67 expression or a secondary change due to decreased glutamatergic innervation, or both. Furthermore, the number of the axon terminals of chandelier cells, labeled with an antibody against the GABA transporter GAT-1, is decreased by as much as 40 % (Woo et al. 1998; Pierri et al. 1999). Also, the GABAA receptor alpha 2 subunit, which, as discussed above, is preferentially localized to synapses formed by chandelier cells, has been found to be upregulated (Volk et al. 2002). More recently, it has been shown that GAD67 protein in PV-containing basket cell terminals is decreased by ~50 % in schizophrenia (Curley and Lewis 2012) and, postsynaptic to these terminals, the expression of the GABAA receptor alpha 1 subunit in pyramidal neurons is downregulated (Glausier and Lewis 2011). Altogether, currently available evidence strongly suggests that PV neurons-mediated inhibition of pyramidal cell activity is compromised in schizophrenia, providing a possible neurobiological basis of gamma band synchrony disturbances.

6 Mechanisms That May Contribute to Aberrant PFC Synaptic Pruning and Schizophrenia Onset

Synaptic refinement is an activity-dependent process that is governed by the Hebbian principle of coincidence detection (Hebb 1949; Katz and Shatz 1996). In its simplest terms, Hebbian principle posits that when the pre- and post-synaptic elements of a synapse are coincidentally active (within a narrow time window in the order of tens of milliseconds as has been experimentally demonstrated in models of spike timing-dependent plasticity), the synapse is strengthened; otherwise, synaptic strength may remain unchanged or the synapse may be weakened or eliminated altogether. Interestingly, the duration of the time window that is required for activity-dependent strengthening of synapses via coincidence detection closely matches the time scale of gamma band oscillation (Engel et al. 1992; Konig et al. 1996; Magee and Johnston 1997; Bi and Poo 1998; Harris et al. 2003; Buzsaki and Draguhn 2004; Harris 2005), and some evidence actually points to a direct relationship (Wespatat et al. 2004). In other words, gamma band oscillation may provide a temporal structure within which activity-dependent synaptic refinement is made possible. Thus, functional disturbances of PV neurons may lead to the aberrant pruning of synapses by disturbing such a temporal structure that is normally supported by gamma band oscillation (Woo et al. 2010), which may be a mechanism that triggers schizophrenia onset (Feinberg 1982; Keshavan et al. 1994; McGlashan and Hoffman 2000).

6.1 Deficient Glutamatergic Inputs May Contribute to the Dysfunction of PV Neurons and Schizophrenia Onset

It has long been known that treatment with NMDA receptor antagonists, such as phencyclidine, produces a syndrome that is highly reminiscent of the clinical picture of schizophrenia (Javitt and Zukin 1991; Krystal et al. 1994; Newcomer and Krystal 2001), and these data led to the NMDA receptor hypofunction model of the disorder (Olney and Farber 1995; Olney et al. 1999). The paradoxical excitotoxic effects of NMDA antagonists are explained, at least in part, by the blockade of the NMDA receptors that are located on GABA neurons (Coyle 2004; Lisman et al. 2008), which have been shown to be some 10-fold more sensitive to NMDA receptor antagonists than the NMDA receptors on pyramidal neurons (Olney and Farber 1995; Grunze et al. 1996; Greene et al. 2000). Of interest, postmortem studies have indeed shown that the expression of the mRNA for the NMDA receptor NR2A subunit in GABA neurons appears to be decreased in subjects with schizophrenia (Woo et al. 2004, 2008).

In primary neuronal cultures, Kinney and colleagues have shown that NR2A expression in PV neurons is 5-fold greater than that in pyramidal cells (Kinney et al. 2006), although it is unclear if this holds true in humans (Bitanihirwe et al. 2009). Furthermore, NR2A, but not NR2B selective antagonist downregulates GAD67 and PV expression in PV neurons (Kinney et al. 2006). Similarly, NMDA antagonism in vivo reduces PV expression (Cochran et al. 2003; Keilhoff et al. 2004; Reynolds et al. 2004; Rujescu et al. 2006; Abdul-Monim et al. 2007; Braun et al. 2007) and the number of axo-axonic cartridges of chandelier cells (Morrow et al. 2007). Taken together, reduced glutamatergic inputs to PV neurons via NMDA receptors, especially those that contain the NR2A subunit, may mediate the functional deficits of PV neurons. In fact, we have found that the number of PV cells that express a detectable level of NR2A mRNA is reduced by as much as 50 % in subjects with schizophrenia (Bitanihirwe et al. 2009). Interestingly, NMDA receptor blockade has been shown to disrupt gamma band rhythms in the entorhinal cortex in animals and it is speculated that this disruption is mediated by the NMDA receptors on PV neurons (Cunningham et al. 2006). Altogether, the evidence available so far suggests that deficits of glutamatergic neurotransmission via NMDA receptors on PV neurons may be a key element in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Specifically, because the expression of GAD67 is known to be regulated by neuronal activity (Jones 1993; Huang 2009), decreased activation of PV neurons due to reduced excitatory inputs could, at least in part, explain the observation of decreased GAD67 mRNA expression in these neurons.

6.2 Oxidative Stress May Contribute to the Dysfunction of PV Neurons and Schizophrenia Onset

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as the superoxide anion (·O2-), hydroxyl radical (·OH) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are generated as by-products of normal biochemical reactions (Halliwell 1984; Dawson and Dawson 1996). These oxygen radicals are normally kept in check by the endogenous antioxidant defense system. When the redox (reduction oxidation) balance between the generation of ROS and the functioning of the antioxidant defense is compromised, ROS can begin to accumulate and cause damage to macromolecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, and lipid membranes (Yao et al. 2001). This type of cellular injury, termed oxidative stress, is increasingly believed to play a central role in the pathophysiology of a wide range of neurologic and psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia (Lohr 1991; Mahadik and Scheffer 1996; Reddy and Yao 1996; Smythies 1997; Yao et al. 2001; Marchbanks et al. 2003; Prabakaran et al. 2004; Behrens and Sejnowski 2009; Do et al. 2009; Bitanihirwe and Woo 2011). Furthermore, oxidative stress can occur at any stage of the illness and in fact may precede disease onset (Mahadik et al. 1998; Behrens and Sejnowski 2009; Do et al. 2009). Oxidative injury can result from increased ROS production, insufficient antioxidant defense, or both. Recent evidence suggests that two enzymes that promote oxidative stress, i.e. neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and NADPH oxidase (Nox), and the endogenous antioxidant enzyme glutamate cysteine ligase (GCL) are involved in the pathophysiologic process by disturbing PV neuronal functions in a process that is mediated by the cytokine interleukin 6, IL-6 (Behrens et al. 2007, 2008; Gysin et al. 2007; Do et al. 2009).

6.2.1 Increased Oxidative Stress May Result from Increased nNOS Activity

Nitric oxide (NO) is a major precursor of free radicals. The formation of NO is catalyzed by NOS. NOS is linked to the NMDA receptor and is activated by Ca2+ influx. It exists in three isoforms: nNOS, which is found mainly in neurons, eNOS, which is found mainly in endothelial cells, and iNOS, which is found mainly in macrophages. In mammals, nNOS contributes to ~90 % of overall NO production (Cannon 1996). NO has a half-life of only a few seconds and is rapidly metabolized to nitrite and nitrate. Due to its unpaired electron (NO•), NO also acts as a free radical and conjugate with superoxide, forming a strong oxidant and nitrating agent called peroxynitrite (ONOO•) (Beckman and Koppenol 1996; Noack et al. 1999). Peroxynitrite reacts with a wide range of biological molecules, including endogenous antioxidants such as glutathione (GSH). Accumulation of peroxynitrite may result in lipid peroxidation, causing damage to proteins, amino acids, and nucleic acids (Keller et al. 1998).

Several lines of evidence point to a role of NO in schizophrenia. First, a higher plasma level of nitrite level has been found in schizophrenia patients (Zoroglu et al. 2002; Yanik et al. 2003). Second, an elevated level of NO has been found in postmortem brains from schizophrenia subjects (Yao et al. 2004). Third, the expression of nNOS mRNA appears to be upregulated in the PFC in subjects with schizophrenia (Baba et al. 2004). Fourth, the plasma level of NO has been observed to be elevated, whereas the activity of antioxidants appears to be decreased in patients with schizophrenia (Akyol et al. 2002). Finally, administration of NOS inhibitor has been shown to block the phencyclidine-induced schizophrenia-mimicking behavior and attenuate a potential schizophrenia physiological marker, prepulse inhibition deficit, in animals (Johansson et al. 1997; Klamer et al. 2001).

6.2.2 Increased Oxidative Stress May Result from Glutathione Deficiency

GSH is a critical antioxidant against oxidative stress. An increasing body of evidence suggests that deficits of GSH may play a role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia (Tosic et al. 2006; Gysin et al. 2007; Do et al. 2009). First, a significant decrease in the levels of GSH and its metabolite γ-glutamylglutamine (γ-Glu-Gln) has been observed in the cerebrospinal fluid from drug-naïve schizophrenia patients (Do et al. 2000). Furthermore, magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies have revealed reduced GSH level in the PFC in patients with schizophrenia (Trabesinger et al. 1999; Matsuzawa et al. 2008). Similar decrease has also been found in the striatum in postmortem brains from schizophrenia subjects (Yao et al. 2004). Second, when challenged by oxidative stress, the induced increase in the activity of GCL, a rate-limiting enzyme in GSH synthesis, in fibroblasts is significantly lower in patients with schizophrenia, indicating a deficit in the ability to react against oxidative stress (Tosic et al. 2006; Gysin et al. 2007). Protein and mRNA expression of the catalytic subunit of GCL, GCLC, also appear to be decreased under baseline conditions as well as under oxidative stress (Tosic et al. 2006; Gysin et al. 2007). Interestingly, a GAG trinucleotide repeat polymorphism in the GCLC gene has been associated with schizophrenia (Gysin et al. 2007). Similarly, association has also been established for the gene that encodes the modulatory subunit of GCL (GCLM); this gene is localized on chromosome 1p21, a region shown by linkage studies to be critical for schizophrenia (Pulver 2000; Arinami et al. 2005). Finally, GSH deficiency can lead to synaptic plasticity deficits and NMDA receptor hypofunction (Steullet et al. 2006). Of interest, these effects appear to be mediated by the NR2A subunit of the NMDA receptor (Kohr et al. 1994), raising the possibility that NR2A hypofunction on PV neurons may be a consequence of oxidative stress. In addition, it has recently been shown that GSH deficit during development leads to the functional disturbances of PV neurons and decreased formation of PNNs (Cabungcal et al. 2013). Taken together, these genetic and functional results provide strong support for the concept that dysregulation of GSH metabolism, in particular GSH synthesis, may play an important role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. In a recently completed clinical trial, it has been found that N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a precursor of GSH, appears to be effective in alleviating, albeit modestly so, some symptoms and normalizes another possible schizophrenia physiological biomarker, mismatch negativity, in chronic schizophrenia patients (Berk et al. 2008; Lavoie et al. 2008). Considering what has been discussed so far, NAC treatment could be drastically more effective during the early phase of schizophrenia, as in theory it can improve if not normalize PV neuronal functions and may thereby arrest or attenuate the pathological deterioration of cortical circuit function.

6.2.3 Summary

It has long been known that NMDA antagonists produce a clinical syndrome that mimics schizophrenia. These drugs have also been shown to profoundly reduce the expression of the mRNA for the GABA synthesizing enzyme GAD67 and PV in PV neurons (Cochran et al. 2002; Kinney et al. 2006; Morrow et al. 2007) and, interestingly, increase the generation of ROS (Ozyurt et al. 2007; Zuo et al. 2007). Together, these findings suggest that a pathophysiological cascade of schizophrenia may involve oxidative insult to PV neurons. In fact, during postnatal development of the PFC, oxidative stress resulting from decreased GSH in the context of increased dopamine activity appears to cause selective damage to PV neurons (Cabungcal et al. 2006). More recently, Behrens et al. have provided strong evidence suggesting that oxidative injury to PV neurons may be mediated by increased Nox, an enzyme that generates superoxide (Behrens et al. 2007), and the increase in Nox appears to be mediated by IL-6 (Behrens et al. 2008). Of interest, circulating levels of interleukins and other cytokines have in fact been shown to be elevated in patients with schizophrenia (Zhang et al. 2002; Garver et al. 2003; Schmitt et al. 2005; Fernandez-Egea et al. 2009). In addition, NMDA antagonists increase IL-6 expression, which, in turn, leads to the loss of PV neuronal phenotype (Behrens et al. 2008). Considering all of these data together, redox regulation imbalance (i.e. increased production of ROS and impaired antioxidant defense due to reduced GSH) appear to be a major contributor to the pathophysiology of PV neuronal dysfunction in schizophrenia. It is speculated that one of the reasons why PV neurons are particularly vulnerable to oxidative insult is because of the increased production of intracellular IL-6 that results from NMDA receptor hypofunction (Behrens et al. 2008).

6.3 Disinhibition May Lead to Excitotoxic Insult to Pyramidal Neurons, Dendritic Deficit, and Schizophrenia Onset

As a result of the functional deficits of PV neurons, pyramidal cells that are postsynaptic to these neurons may become hyperactive (Olney and Farber 1995; Kinney et al. 2006; Homayoun and Moghaddam 2007). Although it is generally thought that large-scale pyramidal cell death in the cerebral cortex does not occur in schizophrenia, “non-lethal” apoptosis can lead to neuronal injury in the form of dendritic atrophy (Glantz et al. 2006). For example, chronic glutamate excess has been shown to lead to a ~20 % decrease in primary dendritic length without causing cell death (Esquenazi et al. 2002). Therefore, even though the discussion so far has focused on the fact that dysfunction of PV neurons may lead to aberrant synaptic pruning and hence schizophrenia onset, excitotoxic injury to pyramidal neurons may also occur and such injury can directly contribute to the loss of dendritic spines and synaptic connectivities.

6.4 Reduced PNNs May Contribute to the Dysfunction of PV and Pyramidal Neurons and Schizophrenia Onset

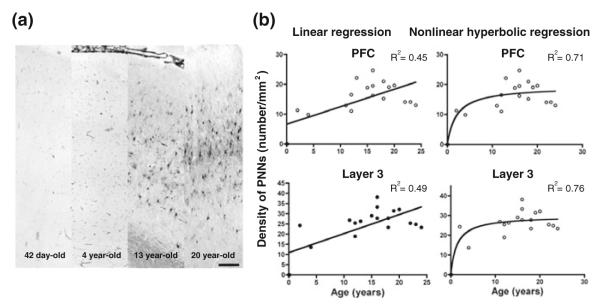

One of the exciting recent findings is that the density of PNNs in limbic brain structures, such as the amygdala and the entorhinal cortex, appears to be decreased by as much as 10-fold in subjects with schizophrenia, but it was unchanged in the subjects with bipolar disorder (Pantazopoulos et al. 2010). In addition, we have recently found that PNN deficit also occurs in the PFC in schizophrenia (Fig. 2; Mauney et al. 2013). If PNNs regulate developmental synaptic pruning in the human PFC, as discussed above, deficient PNN formation surrounding PV and pyramidal neurons would be expected to compromise the experience-dependent consolidation of synaptic connectivities and disturbing the termination of synaptic pruning, respectively. In fact, in a recently completed study, by combining laser capture microdissection with gene expression profiling (Pietersen et al. 2009, 2011), we found that within pyramidal neurons a number of genes encoding CSPGs were downregulated in schizophrenia (Table 1; Pietersen et al. in preparation). In addition, we found changes in genes that encode matrix metallopeptidases (MMPs), which are enzymes that regulate the breakdown and remodeling of ECM by the proteolysis of several ECM components, including the CSPGs (Rauch 2004). Together these data suggest that the decrease in ECM structural components, such as CSPGs, in addition to the alterations in the enzymes that regulate their proteolysis, contribute to the altered integrity of PNNs surrounding pyramidal neurons (Mauney et al. 2013; Pantazopoulos et al. 2010).

Fig. 2.

Densities of perineuronal nets (PNNs) in the PFC in subjects with schizophrenia. a Representative photomicrographs showing the distribution of PNNs in the PFC in schizophrenia (right) and normal control (left) subjects. Scale bar = 100 μm. b Photomicrograph showing a WFA-labeled PNN. Scale bar = 20 μm. c WFA-labeled PNNs are significantly decreased in layers 3 (70 %) and 5 (76 %) in subjects with schizophrenia (SZ; N = 16). Bar graphs represent the mean and upper 95 % confidence interval by cortical layer. Layer 1 is not shown because no PNNs were found in that layer. There are no significant differences in PNN densities between subjects with bipolar disorder (N = 15) and normal control (N = 16) subjects. p value, F ratio: *(0.016, 6.49); **(0.028, 5.36); ***(0.042, 4.51). These findings were derived from postmortem human brains obtained from the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center in Belmont, MA. Figure modified from Mauney et al. 2013

Table 1.

Differentially expressed genes associated with extracellular matrix in pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia

| Gene title | Gene symbol |

p value | Fold- change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggrecan | ACAN | 0.03 | −1.26 |

| ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 1 | ADAMTS1 | 0.03 | 2.56 |

| ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 6 | ADAMTS6 | 0.05 | 1.15 |

| Hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1 | HAPLN1 | 0.05 | −1.14 |

| Leucine proline-enriched proteoglycan (leprecan) 1 | LEPRE1 | 0.04 | −1.21 |

| Lumican | LUM | 0.03 | −1.12 |

| Matrix metallopeptidase 16 (membrane-inserted) | MMP16 | 0.02 | −1.17 |

| Matrix metallopeptidase 25 | MMP25 | 0.02 | −1.14 |

| Matrix metallopeptidase 24 (membrane-inserted) | MMP24 | 0.01 | 1.22 |

| Sperm adhesion molecule 1 (PH-20 hyaluronidase, zona pellucida binding) |

SPAM1 | 0.04 | 1.15 |

| Sparc/osteonectin, cwcv, and kazal-like domains proteoglycan (testican) 3 |

SPOCK3 | 0.01 | 1.11 |

| Spondin 1, extracellular matrix protein | SPON1 | 0.02 | 2.14 |

| Versican | VCAN | 0.04 | −1.13 |

As a result of PNN deficit, the synaptic architecture of the PFC may remain in an excessively plastic, permanently juvenile state where synapses and thus functional cortical circuits fail to be stabilized, which may contribute to the onset of schizophrenia and the persistent symptomatic and cognitive deficits that characterize the course of this chronic illness. This scenario may, at least in part, explain the previous postmortem findings of decreased dendritic spines and neuropil in subjects with schizophrenia (Garey et al. 1998; Costa et al. 2001; Glantz and Lewis 1997, 2000; Selemon and Goldman-Rakic 1999). Of interest, consistent with this hypothesis, using a novel free-water imaging technique, it has recently been shown that the extracellular space in the cerebral cortex, of which ECM and PNNs are major components, was significantly decreased in first-episode schizophrenia patients (Pasternak et al. 2012).

Given the presumed critical role of PNNs in the normal functioning of PV and pyramidal neurons, the maturation of cortical circuits involving these neurons, and the maintenance of cortical circuitry stability, one can speculate that effective therapeutic and preventive strategies may involve restoring the structural and developmental integrity of PNNs. These new findings may also inform the development of novel diagnostic techniques for schizophrenia, using PNNs as a biomarker. For instance, ligands that recognize specific molecular domains that make up PNNs can be developed to detect and quantify these structures in the living human brain, much like imaging amyloid protein in Alzheimer’s disease. In summary, the observation of PNN deficit in the PFC in schizophrenia suggests that detailed characterization of the molecular and pathogenetic basis of this deficit has the potential of leading to breakthroughs in the diagnosis, treatment, early intervention, and prevention of this devastating illness.

7 Conclusion

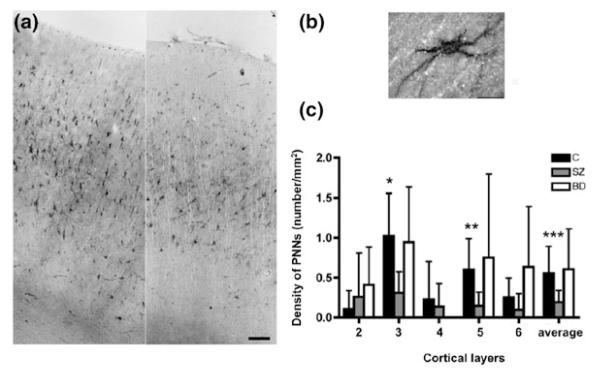

Converging lines of findings suggest that PV neurons play a central role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. In this context, recent discovery of the involvement of PV neurons in regulating the postnatal developmental synaptic plasticity in the cerebral cortex suggests that dysfunction of these neurons during the period of late adolescence and early adulthood may lead to aberrant synaptic pruning in the PFC and possibly other cortical regions as well, thereby contributing to the onset of schizophrenia (Fig. 3). The possible culprits that may underlie the dysfunction of PV neurons include deficient glutamatergic innervation, oxidative stress, and ECM dysregulation. In addition, ECM deficit in the form of decreased PNN formation can directly compromise the integrity of developmental synaptic plasticity, triggering schizophrenia onset. Hence, effective early intervention and prevention strategies for schizophrenia may involve normalizing or mitigating the functional disturbances of PV neurons and PNN deficits by modulating oxidative stress events and restoring the integrity of ECM and afferent glutamatergic disturbances in the cerebral cortex.

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagram summarizing the postulated mechanisms of the normal maturation of PFC circuitry and its dysmaturation in schizophrenia. During normal postnatal development, progressive increase in inhibitory inputs to pyramidal (Pyr) neurons furnished by PV neurons enables pyramidal neuronal circuits to oscillate in gamma band frequency (1). Developmental increase in NMDA neurotransmission on PV neurons may also contribute to their functional maturation (2). However, it is unknown if this increase occurs on both PV-containing basket neurons and PV-containing chandelier neurons, or it is neuronal type-selective (glutamatergic inputs to PV-containing chandelier neurons are not shown in this diagram for the purpose of clarity). Gamma band oscillation provides a necessary temporal structure for spike timing-dependent synaptic plasticity, hence facilitating experience-dependent synaptic and dendritic spine pruning (3). Basket neurons that contain the neuropeptide cholecystokinin (CCK) express the cannabinoid receptor CB1R on their axon terminals, providing a mechanism through which maturation of pyramidal neuronal circuitry can be modulated by the cannabinoid system (4). Finally, as PNNs that enwrap pyramidal and PV neurons begin to form during the periadolescent period, synaptic and dendritic spine pruning is terminated (5). In schizophrenia, inhibitory inputs from PV neurons to pyramidal neurons (6) and NMDA neurotransmission on PV neurons (7) are deficient, which may lead to gamma band oscillation impairment. Gamma band impairment, together with deficient developmental PNN formation (8), which may in part be a consequence of the functional deficits of pyramidal and PV neurons as PNN formation is influenced by neuronal activity, may ultimately lead to aberrant pruning of spines and synapses (9), network instability, information processing disturbances, and ultimately the onset of schizophrenia. Cannabis use during this developmental period may compromise the modulation of pyramidal network activity via the CB1R on CCK neurons, indirectly affecting synaptic pruning and hence contributing to the onset of schizophrenia (10)

Other mechanisms that have not been discussed in this chapter may also contribute to the pathogenesis of schizophrenia onset by disturbing the functional maturation of PV neurons and/or the developmental PFC synaptic pruning process. Stress, for instance, can directly compromise dendritic spine integrity and hence pyramidal cell circuit stability and fidelity (Arnsten and Shansky 2004; Holtzman et al. 2013). In addition, cannabis use has been associated with the onset of schizophrenia (Semple et al. 2005; Cohen et al. 2008; Bossong and Niesink 2010; Volk and Lewis 2010). Because the cannabinoid CB1 receptor is localized to the axons of the subset of perisomatically targeting basket cells that contain the neuropeptide cholecystokinin or CCK (Freund 2003; Soltesz 2005) (Fig. 3); through this circuit property the cannabinoid system can regulate the release of GABA from CCK neurons and hence modulate gamma band activity (Beinfeld and Connolly 2001; Hajos et al. 2008). As such, cannabis use may play a role in triggering the onset of schizophrenia via its effect on gamma band synchrony.

Finally, it is rather striking that many of the potential pathophysiological events described in this chapter appear to be interrelated, although the casual relationships between these events are at present unclear. Toward this end, biologically realistic computational modeling may turn out to be a very powerful approach to understand how these rather complex events, either individually or through various combinatorial permutations, may contribute to the pathophysiological process that triggers schizophrenia onset, using functional endophenotypes such as working memory or gamma band oscillation deficits as outcome measures (Siekmeier and Hoffman 2002; Vierling-Claassen et al. 2008; Siekmeier and Woo 2012). Taken together, recent advances in the neurobiology of adolescent cortical development and the increasing understanding of the pathophysiology of cortical circuit dysfunction in schizophrenia have converged onto a set of novel, specific and testable hypotheses of the possible mechanisms that may lead to the onset of this devastating illness.

Acknowledgments

The author’s laboratory is supported by grants MH076060, MH082235, and MH080272 (Boston CIDAR, Vulnerability to Progression in Schizophrenia) from the National Institutes of Health. We also thank the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center and the National Institute of Child and Human Development Brain and Tissue Bank for providing human brain specimens.

References

- Abdul-Monim Z, Neill JC, Reynolds GP. Sub-chronic psychotomimetic phencyclidine induces deficits in reversal learning and alterations in parvalbumin-immunoreactive expression in the rat. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21:198–205. doi: 10.1177/0269881107067097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akyol O, Herken H, Uz E, et al. The indices of endogenous oxidative and antioxidative processes in plasma from schizophrenic patients. The possible role of oxidant/antioxidant imbalance. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:995–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(02)00220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL. Tragectories of brain development: point of vulnerability or window of opportunity? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:3–18. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SA, Classey JD, Conde F, Lund JS, Lewis DA. Synchronous development of pyramidal neuron dendritic spines and parvalbumin-immunoreactive chandelier neuron axon terminals in layer III of monkey prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 1995;67:7–22. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00051-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arinami T, Ohtsuki T, Ishiguro H, et al. Genomewide high-density SNP linkage analysis of 236 Japanese families supports the existence of schizophrenia susceptibility loci on chromosomes 1p, 14q, and 20p. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:937–944. doi: 10.1086/498122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Shansky RM. Adolescence: vulnerable period for stress-induced prefrontal cortical function? Introduction to part IV. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:143–147. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba H, Suzuki T, Arai H, Emson PC. Expression of nNOS and soluble guanylate cyclase in schizophrenic brain. Neuroreport. 2004;15:677–680. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200403220-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman JS, Koppenol WH. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: the good, the bad, and ugly. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C1424–C1437. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens MM, Sejnowski TJ. Does schizophrenia arise from oxidative dysregulation of parvalbumin-interneurons in the developing cortex? Neuropharmacology. 2009;57:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens MM, Ali SS, Dao DN, Lucero J, Shekhtman G, Quick KL, Dugan LL. Ketamine-induced loss of phenotype of fast-spiking interneurons is mediated by NADPH-oxidase. Science. 2007;318:1645–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1148045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens MM, Ali SS, Dugan LL. Interleukin-6 mediates the increase in NADPH-oxidase in the ketamine model of schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13957–13966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4457-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beinfeld MC, Connolly K. Activation of CB1 cannabinoid receptors in rat hippocampal slices inhibits potassium-evoked cholecystokinin release, a possible mechanism contributing to the spatial memory defects produced by cannabinoids. Neurosci Lett. 2001;301:69–71. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01591-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes FM. Emerging principles of altered neural circuitry in schizophrenia. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;31:251–269. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes FM, Berretta S. GABAergic interneurons: implications for understanding schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:1–27. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardi N, Pizzorusso T, Maffei L. Critical periods during sensory development. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:138–145. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)00047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Copolov D, Dean O, et al. N-acetyl cysteine as a glutathione precursor for schizophrenia—a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berretta S. Extracellular matrix abnormalities in schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1584–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi GQ, Poo MM. Synaptic modifications in cultured hippocampal neurons: dependence on spike timing, synaptic strength, and postsynaptic cell type. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10464–10472. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10464.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitanihirwe BK, Woo T-UW. Oxidative stress in schizophrenia: an integrated approach. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:878–893. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitanihirwe BK, Lim MP, Kelley JF, Kaneko T, Woo T-UW. Glutamatergic deficits and parvalbumin-containing inhibitory neurons in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossong MG, Niesink RJ. Adolescent brain maturation, the endogenous cannabinoid system and the neurobiology of cannabis-induced schizophrenia. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;92:370–385. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois JP, Goldman-Rakic PS, Rakic P. Synaptogenesis in the prefrontal cortex of rhesus monkeys. Cereb Cortex. 1994;4:78–96. doi: 10.1093/cercor/4.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun I, Genius J, Grunze H, Bender A, Moller HJ, Rujescu D. Alterations of hippocampal and prefrontal GABAergic interneurons in an animal model of psychosis induced by NMDA receptor antagonism. Schizophr Res. 2007;97:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner G, Brauer K, Hartig W, et al. Perineuronal nets provide a polyanionic, glia-associated form of microenvironment around certain neurons in many parts of the rat brain. Glia. 1993;8:183–200. doi: 10.1002/glia.440080306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G. Rhythms of the brain. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G, Draguhn A. Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks. Science. 2004;304:1926–1929. doi: 10.1126/science.1099745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabungcal JH, Nicolas D, Kraftsik R, Cuenod M, Do KQ, Hornung JP. Glutathione deficit during development induces anomalies in the rat anterior cingulate GABAergic neurons: relevance to schizophrenia. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22:624–637. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabungcal JH, Steullet P, Kraftsik R, Cuenod M, Do KQ. Early-life insults impair parvalbumin interneurons via oxidative stress: reversal by N-acetylcysteine. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD. Abnormalities of brain structure and function in schizophrenia: implications for aetiology and pathophysiology. Ann Med. 1996;28:533–539. doi: 10.3109/07853899608999117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carulli D, Rhodes KE, Brown DJ, et al. Composition of perineuronal nets in the adult rat cerebellum and the cellular origin of their components. J Comp Neurol. 2006;494:559–577. doi: 10.1002/cne.20822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio MR, Blumcke I. Perineuronal nets—a specialized form of extracellular matrix in the adult nervous system. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1994;19:128–145. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio MR, Chiquet-Ehrismann R. ‘Perineuronal nets’ around cortical interneurons expressing parvalbumin are rich in tenascin. Neurosci Lett. 1993;162:137–140. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90579-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho RY, Konecky RO, Carter CS. Impairments in frontal cortical gamma synchrony and cognitive control in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19878–19883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609440103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SM, Fujimura M, Morris BJ, Pratt JA. Acute and delayed effects of phencyclidine upon mRNA levels of markers of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurotransmitter function in the rat brain. Synapse. 2002;46:206–214. doi: 10.1002/syn.10126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SM, Kennedy M, McKerchar CE, Steward LJ, Pratt JA, Morris BJ. Induction of metabolic hypofunction and neurochemical deficits after chronic intermittent exposure to phencyclidine: differential modulation by antipsychotic drugs. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:265–275. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Solowij N, Carr V. Cannabis, cannabinoids and schizophrenia: integration of the evidence. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42:357–368. doi: 10.1080/00048670801961156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa E, Davis J, Grayson DR, Guidotti A, Pappas GD, Pesold C. Dendritic spine hypoplasticity and downregulation of reelin and GABAergic tone in schizophrenia vulnerability. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:723–742. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa E, Davis JM, Dong E, Grayson DR, Guidotti A, Tremolizzo L, Veldic M. A GABAergic cortical deficit dominates schizophrenia pathophysiology. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2004;16:1–23. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v16.i12.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT. The GABA-glutamate connection in schizophrenia: which is the proximate cause? Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1507–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz DA, Eggan SM, Lewis DA. Postnatal development of pre- and postsynaptic GABA markers at chandelier cell connections with pyramidal neurons in monkey prefrontal cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:385–400. doi: 10.1002/cne.10833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham MO, Hunt J, Middleton S, et al. Region-specific reduction in entorhinal gamma oscillations and parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons in animal models of psychiatric illness. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2767–2776. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5054-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley AA, Lewis DA. Cortical basket cell dysfunction in schizophrenia. J Physiol. 2012;590:715–724. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.224659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson P, Gottfries J, Bogdanovic N, Ekman R, Karlsson I, Gottfries CG, Blennow K. The synaptic-vesicle-specific proteins rab3a and synaptophysin are reduced in thalamus and related cortical brain regions in schizophrenic brains. Schizophr Res. 1999;40:23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Free radicals and neuronal cell death. Cell Death Differ. 1996;3:71–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deepa SS, Carulli D, Galtrey C, et al. Composition of perineuronal net extracellular matrix in rat brain: a different disaccharide composition for the net-associated proteoglycans. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17789–17800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cristo G. Development of cortical GABAergic circuits and its implications for neurodevelopmental disorders. Clin Genet. 2007;72:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dityatev A, Schachner M. Extracellular matrix molecules and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:456–468. doi: 10.1038/nrn1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dityatev A, Schachner M, Sonderegger P. The dual role of the extracellular matrix in synaptic plasticity and homeostasis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:735–746. doi: 10.1038/nrn2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do KQ, Trabesinger AH, Kirsten-Kruger M, et al. Schizophrenia: glutathione deficit in cerebrospinal fluid and prefrontal cortex in vivo. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3721–3728. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do KQ, Cabungcal JH, Frank A, Steullet P, Cuenod M. Redox dysregulation, neurodevelopment, and schizophrenia. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durstewitz D, Gabriel T. Dynamical basis of irregular spiking in NMDA-driven prefrontal cortex neurons. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:894–908. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhk044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood SL, Burnet PW, Harrison PJ. Altered synaptophysin expression as a marker of synaptic pathology in schizophrenia. Neuroscience. 1995;66:309–319. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00586-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel AK, Konig P, Kreiter AK, Schillen TB, Singer W. Temporal coding in the visual cortex: new vistas on integration in the nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:218–226. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90039-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esquenazi S, Monnerie H, Kaplan P, Le Roux P. BMP-7 and excess glutamate: opposing effects on dendrite growth from cerebral cortical neurons in vitro. Exp Neurol. 2002;176:41–54. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagiolini M, Fritschy JM, Low K, Mohler H, Rudolph U, Hensch TK. Specific GABAA circuits for visual cortical plasticity. Science. 2004;303:1681–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.1091032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg I. Schizophrenia: caused by a fault in programmed synaptic elimination during adolescence? J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:319–334. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Egea E, Bernardo M, Donner T, et al. Metabolic profile of antipsychotic-naive individuals with non-affective psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:434–438. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.052605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF. Interneuron Diversity series: Rhythm and mood in perisomatic inhibition. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:489–495. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischknecht R, Gundelfinger ED. The brain’s extracellular matrix and its role in synaptic plasticity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;970:153–171. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0932-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischknecht R, Seidenbecher CI. The crosstalk of hyaluronan-based extracellular matrix and synapses. Neuron Glia Biol. 2008;4:249–257. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X09990226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbott PL, Bacon SJ. Local circuit neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex (areas 24a, b, c, 25 and 32) in the monkey: I. Cell morphology and morphometrics. J Comp Neurol. 1996;364:567–608. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960122)364:4<567::AID-CNE1>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtrey CM, Fawcett JW. The role of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in regeneration and plasticity in the central nervous system. Brain Res Rev. 2007;54:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, Fritschy JM. Selective allocation of GABAA receptors containing the alpha 1 subunit to neurochemically distinct subpopulations of rat hippocampal interneurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:837–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, Fritschy JM, Benke D, Mohler H. Neuron-specific expression of GABAA-receptor subtypes: differential association of the alpha 1- and alpha 3-subunits with serotonergic and GABAergic neurons. Neuroscience. 1993;54:881–892. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90582-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey LJ, Ong WY, Patel TS, et al. Reduced dendritic spine density on cerebral cortical pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:446–453. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.4.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garver DL, Tamas RL, Holcomb JA. Elevated interleukin-6 in the cerebrospinal fluid of a previously delineated schizophrenia subtype. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1515–1520. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giamanco KA, Matthews RT. Deconstructing the perineuronal net: cellular contributions and molecular composition of the neuronal extracellular matrix. Neuroscience. 2012;218:367–384. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianfranceschi L, Siciliano R, Walls J, et al. Visual cortex is rescued from the effects of dark rearing by overexpression of BDNF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12486–12491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934836100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glahn DC, Therman S, Manninen M, Huttunen M, Kaprio J, Lonnqvist J, Cannon TD. Spatial working memory as an endophenotype for schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:624–626. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz LA, Lewis DA. Reduction of synaptophysin immunoreactivity in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Regional and diagnostic specificity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:660–669. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830190088009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz LA, Lewis DA. Decreased dendritic spine density on prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:65–73. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz LA, Gilmore JH, Lieberman JA, Jarskog LF. Apoptotic mechanisms and the synaptic pathology of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;81:47–63. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glausier JR, Lewis DA. Selective pyramidal cell reduction of GABA(A) receptor alpha1 subunit messenger RNA expression in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:2103–2110. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk L, et al. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8174–8179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402680101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS. Development of cortical circuitry and cognitive function. Child Dev. 1987;58:601–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS, Bourgeois J-P, Rakic P. Synaptic substrate of cognitive development: life-span analysis of synaptogenesis in the prefrontal cortex of the nonhuman primate. In: Krasnegor NA, Lyon GR, Goldman-Rakic PS, editors. Development of the prefrontal cortex. Paul H. Brookes Publishing; Baltimore: 1997. pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Burgos G, Hashimoto T, Lewis DA. Alterations of cortical GABA neurons and network oscillations in schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:335–344. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene R, Bergeron R, McCarley R, Coyle JT, Grunze H. Short-term and long-term effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor hypofunction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1180–1181. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.12.1180. author reply 1182–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunze HC, Rainnie DG, Hasselmo ME, Barkai E, Hearn EF, McCarley RW, Greene RW. NMDA-dependent modulation of CA1 local circuit inhibition. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2034–2043. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-02034.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundelfinger ED, Frischknecht R, Choquet D, Heine M. Converting juvenile into adult plasticity: a role for the brain’s extracellular matrix. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:2156–2165. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gysin R, Kraftsik R, Sandell J, et al. Impaired glutathione synthesis in schizophrenia: convergent genetic and functional evidence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16621–16626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706778104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajos M, Hoffmann WE, Kocsis B. Activation of cannabinoid-1 receptors disrupts sensory gating and neuronal oscillation: relevance to schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:1075–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakak Y, Walker JR, Li C, et al. Genome-wide expression analysis reveals dysregulation of myelination-related genes in chronic schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4746–4751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081071198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halim ND, Weickert CS, McClintock BW, Hyde TM, Weinberger DR, Kleinman JE, Lipska BK. Presynaptic proteins in the prefrontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia and rats with abnormal prefrontal development. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:797–810. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Oxygen radicals: a commonsense look at their nature and medical importance. Med Biol. 1984;62:71–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanover JL, Huang ZJ, Tonegawa S, Stryker MP. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor overexpression induces precocious critical period in mouse visual cortex. J Neurosci. 1999;19:RC40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-j0003.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KD. Neural signatures of cell assembly organization. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:399–407. doi: 10.1038/nrn1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KD, Csicsvari J, Hirase H, Dragoi G, Buzsaki G. Organization of cell assemblies in the hippocampus. Nature. 2003;424:552–556. doi: 10.1038/nature01834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig W, Derouiche A, Welt K, et al. Cortical neurons immunoreactive for the potassium channel Kv3.1b subunit are predominantly surrounded by perineuronal nets presumed as a buffering system for cations. Brain Res. 1999;842:15–29. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01784-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Volk DW, Eggan SM, et al. Gene expression deficits in a subclass of GABA neurons in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6315–6326. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06315.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Nguyen QL, Rotaru D, et al. Protracted developmental trajectories of GABA(A) receptor alpha1 and alpha2 subunit expression in primate prefrontal cortex. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:1015–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebb DO. The organization of behavior. Wiley; New York: 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK. Controlling the critical period. Neurosci Res. 2003;47:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(03)00164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK. Critical period mechanisms in developing visual cortex. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2005a;69:215–237. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(05)69008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK. Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005b;6:877–888. doi: 10.1038/nrn1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockfield S, Kalb RG, Zaremba S, Fryer H. Expression of neural proteoglycans correlates with the acquisition of mature neuronal properties in the mammalian brain. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1990;55:505–514. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1990.055.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman CW, Trotman HD, Goulding SM, et al. Stress and neurodevelopmental processes in the emergence of psychosis. Neuroscience. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.12.017. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homayoun H, Moghaddam B. NMDA receptor hypofunction produces opposite effects on prefrontal cortex interneurons and pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11496–11500. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2213-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honer WG, Falkai P, Bayer TA, et al. Abnormalities of SNARE mechanism proteins in anterior frontal cortex in severe mental illness. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:349–356. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard MW, Rizzuto DS, Caplan JB, et al. Gamma oscillations correlate with working memory load in humans. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:1369–1374. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZJ. Activity-dependent development of inhibitory synapses and innervation pattern: role of GABA signalling and beyond. J Physiol. 2009;587:1881–1888. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.168211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZJ, Kirkwood A, Pizzorusso T, et al. BDNF regulates the maturation of inhibition and the critical period of plasticity in mouse visual cortex. Cell. 1999;98:739–755. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley GW, Benson DL, Jones EG, Isackson PJ. Developmental expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor mRNA by neurons of fetal and adult monkey prefrontal cortex. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1992;70:53–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(92)90103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher PR. Neural plasticity. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO, Yamada KM. Extracellular matrix biology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Itami C, Kimura F, Nakamura S. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates the maturation of layer 4 fast-spiking cells after the second postnatal week in the developing barrel cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2241–2252. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3345-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Zukin SR. Recent advances in the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1301–1308. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B, Huang ZJ, Morales B, Kirkwood A. Maturation of GABAergic transmission and the timing of plasticity in visual cortex. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;50:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson C, Jackson DM, Svensson L. Nitric oxide synthase inhibition blocks phencyclidine-induced behavioural effects on prepulse inhibition and locomotor activity in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 1997;131:167–173. doi: 10.1007/s002130050280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG. GABAergic neurons and their role in cortical plasticity in primates. Cereb Cortex. 1993;3:361–372. doi: 10.1093/cercor/3.5.361-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalus P, Muller TJ, Zuschratter W, Senitz D. The dendritic architecture of prefrontal pyramidal neurons in schizophrenic patients. Neuroreport. 2000;11:3621–3625. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200011090-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri H, Fagiolini M, Hensch TK. Optimization of somatic inhibition at critical period onset in mouse visual cortex. Neuron. 2007;53:805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LC, Shatz CJ. Synaptic activity and the construction of cortical circuits. Science. 1996;274:1133–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Kondo S. Parvalbumin, somatostatin and cholecystokinin as chemical markers for specific GABAergic interneuron types in the rat frontal cortex. J Neurocytol. 2002;31:277–287. doi: 10.1023/a:1024126110356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Kubota Y. GABAergic cell subtypes and their synaptic connections in rat frontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 1997;7:476–486. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.6.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilhoff G, Becker A, Grecksch G, Wolf G, Bernstein HG. Repeated application of ketamine to rats induces changes in the hippocampal expression of parvalbumin, neuronal nitric oxide synthase and cFOS similar to those found in human schizophrenia. Neuroscience. 2004;126:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller JN, Kindy MS, Holtsberg FW, et al. Mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase prevents neural apoptosis and reduces ischemic brain injury: suppression of peroxynitrite production, lipid peroxidation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurosci. 1998;18:687–697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00687.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Anderson S, Pettegrew JW. Is schizophrenia due to excessive synaptic pruning in the prefrontal cortex? The Feinberg hypothesis revisited. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28:239–265. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keverne EB. GABA-ergic neurons and the neurobiology of schizophrenia and other psychoses. Brain Res Bull. 1999;48:467–473. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney JW, Davis CN, Tabarean I, Conti B, Bartfai T, Behrens MM. A specific role for NR2A-containing NMDA receptors in the maintenance of parvalbumin and GAD67 immunoreactivity in cultured interneurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1604–1615. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4722-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood A, Lee HK, Bear MF. Co-regulation of long-term potentiation and experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in visual cortex by age and experience. Nature. 1995;375:328–331. doi: 10.1038/375328a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klamer D, Engel JA, Svensson L. The nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, L-NAME, block phencyclidine-induced disruption of prepulse inhibition in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2001;156:182–186. doi: 10.1007/s002130100783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T, Roberts JD, Somogyi P. Cell type- and input-specific differences in the number and subtypes of synaptic GABA(A) receptors in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2513–2521. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02513.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohr G, Eckardt S, Luddens H, Monyer H, Seeburg PH. NMDA receptor channels: subunit-specific potentiation by reducing agents. Neuron. 1994;12:1031–1040. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]