Abstract

Background

There is controversy about whether to retain or excise the posterior cruciate ligament in rheumatoid knees because attenuation of the ligament is often present in this subgroup of patients. We reviewed more than 15 years of results of cruciate-retaining total knee replacements (TKRs) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Methods

We reviewed patients’ charts and radiographs to evaluate knee range of motion and flexion contractures, component loosening and osteolysis at the bone–cement interface. Our primary outcome was revision of a femoral or tibial component for any reason, and the secondary outcome was revision for any reason and periprosthetic fracture during the follow-up period.

Results

Our study included 112 patients (7 men, 105 women, 176 knees). Their mean age was 49.3 (range 33–64) years. Twenty-one patients died and 16 were lost to follow-up, leaving 75 patients (119 knees) with a minimum follow-up of 15 (mean 16.1) years for our analysis. Of these, 61 patients (101 knees) were available for clinical and radiological evaluation at the final follow-up assessment. At a mean of 12.2 (range 6–16) years, revision was necessary in 14 patients (19 knees), including 1 patient with an infection. Eleven patients (11 knees) had periprosthetic fractures at a mean of 11.4 (range 5–14) years after the index operation. The survival rate, with the end point being revision of the femoral or tibial component for any reason, was 98.7% at 10 years and 83.6% at 17 years. The survival rate of revision and periprosthetic fracture was 97.6% at 10 years and 76.9% at 17 years.

Conclusion

Special attention should be paid to component loosening or periprosthetic fracture after more than 10 years of follow-up in this subgroup of patients.

Abstract

Contexte

On ne s’entend pas sur la nécessité de conserver ou d’exciser le ligament croisé postérieur dans les genoux rhumatoïdes en raison de l’affaiblissement du ligament, souvent présent chez cette catégorie de patients. Nous avons passé en revue sur plus de 15 ans les résultats de prothèses totales du genou (PTG) avec préservation du ligament croisé chez des patients atteints de polyarthrite rhumatoïde.

Méthodes

Nous avons examiné les dossiers et les radiographies des patients pour évaluer l’amplitude de mouvement et les contractures en flexion des genoux, le descellement des composants et l’ostéolyse à l’interface os–ciment. Notre paramètre principal était la révision d’un composant fémoral ou tibial, peu importe la raison, et le paramètre secondaire était la révision, peu importe la raison, ainsi que les fractures périprothétiques durant la période de suivi.

Résultats

Notre étude a regroupé 112 patients (7 hommes, 105 femmes; 176 genoux). L’âge moyen était de 49,3 ans (entre 33 et 64 ans). Vingt-et-un patients sont décédés et 16 ont été perdus au suivi, ce qui laissait 75 patients (119 genoux) et un suivi minimum de 15 ans (moyenne 16,1 ans) pour notre analyse. Parmi ces patients, 61 (101 genoux) étaient disponibles pour évaluation clinique et radiologique à la dernière évaluation de suivi. Sur une moyenne de 12,2 ans (entre 6 et 16 ans), une révision a été nécessaire chez 14 patients (19 genoux), y compris 1 patient porteur d’une infection. Onze patients (11 genoux) ont présenté des fractures périprothétiques en moyenne 11,4 ans (entre 5 et 14 ans) après l’intervention initiale. Le taux de survie, avec pour paramètre principal la révision d’un composant fémoral ou tibial, qu’elle qu’en soit la raison, a été de 98,7 % à 10 ans et de 83,6 % à 17 ans. Le taux de survie des révisions et de fractures périprothétiques a été de 97,6 % à 10 ans et de 76,9 % à 17 ans.

Conclusion

Il faut porter une attention spéciale au descellement des composants ou à la fracture périprothétique après plus de 10 ans de suivi dans cette catégorie de patients.

Total knee replacement (TKR) has proven to be the most successful intervention that relieves pain and improves physical function in the treatment of knees affected by rheumatoid arthritis (RA).1–3 Performing TKR in patients with RA can be technically difficult owing to the poor quality of bone and surrounding soft tissues and to associated bone deformities.3,4 Long-term results of TKR for rheumatoid knees have been well documented, with a reported survival rate of the prosthesis between 81% and 97.7% at more than 10 years of follow-up.5–9 However, there is controversy about whether to retain or excise the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) in rheumatoid knees because attenuation of the ligament is often present in this subgroup of patients.10 The purpose of this retrospective study was to report our more than 15 years of clinical and radiological results of cruciate-retaining TKR using different fixation techniques in patients with RA.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed all consecutive primary cruciate-retaining TKRs in patients with RA performed by 1 of us (H.K.C.) at a single medical centre between October 1989 and August 1996. During this period, our practice was to preserve the PCL during the TKR procedure in all knees, unless they had intraoperative evidence of severe attenuation. October 2012 was the designated final follow-up date. The Institutional Review Board on Human Subjects Research and Ethics Committees of the Hanyang University Hospital (Seoul, South Korea) approved our study protocol, and all patients provided informed consent.

All patients received a standard medial parapatellar arthrotomy. The distal femur was first resected to achieve a target tibiofemoral alignment of 5°–7° valgus in the coronal plane. After performing the ligamentous balance, the proximal tibia was resected perpendicularly to the shaft of the tibia in the coronal plane and sloped 6°–8° posteriorly in the sagittal plane. The surgeon attempted to preserve the PCL. However, a graduated release was performed from the posterior aspect of the tibia using the periosteal elevator when the PCL tension was tight. Three different cruciate-retaining prostheses were used based on the surgeon’s preference: the Press Fit Condylar Knee System (PFC; Johnson & Johnson), the Miller-Galante knee (MG; Zimmer) and the Nexgen knee (Zimmer). Fixation of the prosthesis was done with or without cement or with a hybrid fixation technique (i.e., cemented on the tibial component and uncemented on the femoral side). Depending on the protocol at the time of operation, the fixation techniques were chosen primarily in accordance with the quality and congruity of the bone–prosthesis interface.

We collected clinical and radiological data from the patients’ charts and from radiographs that were obtained at specific points during the study period. For each patient, a clinical assessment, which involved physical examination and completion of the American Knee Society scoring system,11 was performed preoperatively and annually thereafter. We assessed knee range of motion and flexion contractures using a long-arm goniometer. We obtained standing anteroposterior radiographs, posteroanterior radiographs and long-leg standing radiographs. To evaluate component loosening and osteolysis at the bone–cement interface, we assessed the preoperative and final follow-up standing radiographs in accordance with the protocols of the Knee Society radiographic scoring system.12

Statistical analysis

We performed a Kaplan–Meier analysis13 to estimate survivorship: the first end point was the revision of a femoral or tibial component for any reason, and the second end point was revision for any reason and periprosthetic fracture during the follow-up period. A paired t test was used to compare the mean values of clinical scores. We considered results to be significant at p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 176 consecutive primary cruciate-retaining TKRs were performed in 112 patients (7 men and 105 women) during the study period. At the time of surgery, the mean age of patients was 49.3 (range 33–64) years. The patella was resurfaced in 167 (94.9%) knees, and for the fixation technique of the prosthesis, 45 (25.6%) replacements were performed with cement, 69 (39.2%) replacements were performed without cement and 62 (35.2%) replacements were fixed with the hybrid technique.

During the study period, 21 patients died and 16 were lost to follow-up, leaving 75 patients (119 knees) with a minimum of 15 years’ follow-up for inclusion in our analyses. The mean follow-up period of the 75 patients was 16.1 (range 15–21) years; however, 14 patients (18 knees) were available only for phone interview. Sixty-one patients (101 knees) were therefore clinically and radiologically available at the final follow-up assessment.

The mean range of motion of the 101 knees preoperatively and at final review was 101° (range 60°–140°) and 115° (range 90°– 40°), respectively. The mean flexion contracture was 27.0° (range 0°–60°) preoperatively and 1.8° (range 0°–40°) at final review. The mean preoperative Knee Society score and function scores were 38.0 (range 0–60) points and 8.0 (range 0–55) points, respectively. At the final review, the mean Knee Society scores and function scores improved to 86.0 (range 50–100) points and 81.6 (range 50–100) points, respectively (p < 0.001).

The preoperative alignment of 101 knees was a mean valgus of 7.0° (range 6° varus to 19° valgus). At final review, the alignment was a mean valgus of 6.2° (range 2.4° varus to 14.8° valgus). At final review, the radiographs of 21 (20.7%) knees showed radiolucent lines at the cement–bone interface. Seven knees scored between 5 and 9 points, and no TKR showed radiolucency suggestive of impending failure.12

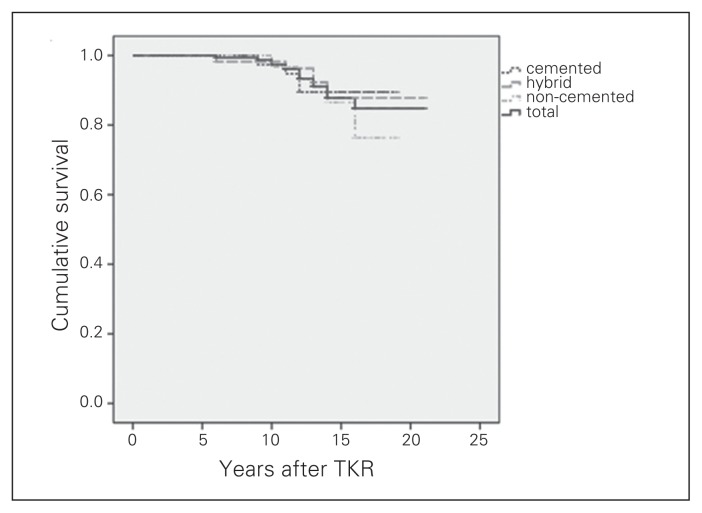

Revision was necessary in 19 (15.9%) knees (including 1 patient with infection) at a mean of 12.2 (range 6–16) years after surgery. Five knees underwent revision for polyethylene exchange owing to polyethylene wear or breakage. Fourteen knees had a revision of the implant: 1 because of infection and 13 because of mechanical pain associated with loosening or osteolysis of the femoral or tibial components. There was no revision because of clinically proven posterior instability or patellofemoral joint problems. After the index operation, periprosthetic fracture occurred in 11 women (11 knees) at a mean of 11.4 (range 5–14) years. All periprosthetic fractures occurred on the femoral side. Periprosthetic fractures occurred more than 9 years after the index surgery except in 1 patient in whom the fracture occurred after 5 years. For the treatment of periprosthetic fractures, 9 knees underwent open reduction and plate fixation, and the remaining 2 knees underwent conservative treatment by plaster long leg cast application. The survival rate (with the end point being revision of femoral or tibial component for any reason, including polyethylene exchange) was 98.7% at 10 years and 83.6% at 17 years (Table 1). The survival rate of revision and periprosthetic fracture (with the end point being revision for any reason and all periprosthetic fractures) was 97.6% at 10 years and 76.9% at 17 years (Table 2). The worst-case survival (with the end point being revision of the femoral or tibial component for any reason, presuming all patients lost to follow-up were “failures”) was 84.7% at 10 years and 61.4% at 16 years. There was a trend for better survival with cemented fixation, followed by hybrid fixation and uncemented fixation; however, the difference was not significant (p = 0.18; Figs. 1 and 2)

Table 1.

Outcomes of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who had total knee replacement (end point of revision of a component for any reason), by annual follow-up

| Follow-up, yr | No. of patients | No. of revisions | No. lost to follow-up | No. deaths | No. at risk | Success rate (%) | Survival rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | 176 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 176.0 | 100 | 100 |

| 1–2 | 176 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 175.5 | 100 | 100 |

| 2–3 | 175 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 172.5 | 100 | 100 |

| 3–4 | 170 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 168.0 | 100 | 100 |

| 4–5 | 166 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 165.0 | 100 | 100 |

| 5–6 | 164 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 162.5 | 100 | 100 |

| 6–7 | 161 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 159.5 | 99.4 | 99.4 |

| 7–8 | 158 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 157.0 | 100 | 99.4 |

| 8–9 | 156 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 154.0 | 100 | 99.4 |

| 9–10 | 152 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 151.0 | 99.3 | 98.7 |

| 10–11 | 150 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 148.5 | 98.7 | 97.4 |

| 11–12 | 147 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 143.0 | 98.6 | 96.0 |

| 12–13 | 139 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 132.0 | 97.1 | 93.2 |

| 13–14 | 125 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 118.0 | 97.6 | 90.8 |

| 14–15 | 111 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 106.0 | 96.4 | 87.5 |

| 15–16 | 101 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 79.5 | 100 | 87.5 |

| 16–17 | 58 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 44.5 | 96.6 | 83.6 |

| 17–18 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26.5 | 100 | 83.6 |

| 18–19 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 16.0 | 100 | 83.6 |

| 19–20 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.0 | 100 | 83.6 |

| 20–21 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.0 | 100 | 83.6 |

| 21–22 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 | 100 | 83.6 |

Table 2.

Outcomes of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who had total knee replacement (end point of revision and periprosthetic fracture), by annual follow-up

| Follow-up, yr | No. of patients | No. of revisions | No. lost to follow-up | No. deaths | No. at risk | Success rate (%) | Survival rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | 176 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 176.0 | 100 | 100 |

| 1–2 | 176 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 175.5 | 100 | 100 |

| 2–3 | 175 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 172.5 | 100 | 100 |

| 3–4 | 170 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 168.0 | 100 | 100 |

| 4–5 | 166 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 165.0 | 100 | 100 |

| 5–6 | 164 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 162.5 | 99.4 | 99.4 |

| 6–7 | 161 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 159.5 | 99.4 | 98.8 |

| 7–8 | 158 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 157.0 | 100 | 98.8 |

| 8–9 | 156 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 154.0 | 100 | 98.8 |

| 9–10 | 152 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 151.0 | 98.7 | 97.5 |

| 10–11 | 150 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 148.5 | 98.7 | 96.2 |

| 11–12 | 147 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 143.0 | 98.0 | 94.2 |

| 12–13 | 139 | 10 | 0 | 4 | 132.0 | 92.8 | 87.3 |

| 13–14 | 125 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 118.0 | 97.6 | 85.1 |

| 14–15 | 111 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 106.0 | 94.6 | 80.4 |

| 15–16 | 101 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 79.5 | 100 | 80.4 |

| 16–17 | 58 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 44.5 | 96.6 | 76.9 |

| 17–18 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26.5 | 100 | 76.9 |

| 18–19 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 16.0 | 100 | 76.9 |

| 19–20 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.0 | 100 | 76.9 |

| 20–21 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.0 | 100 | 76.9 |

| 21–22 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 | 100 | 76.9 |

Fig. 1.

Survival curve with the end point being revision of a femoral or tibial component for any reason. TKR = total knee replacement.

Fig. 2.

Survival curve with the end point being revision and periprosthetic fracture. TKR = total knee replacement.

Discussion

The long-term results of TKR for RA are well documented, and most studies report excellent long-term survivorship of TKR in patients with RA (81%–97.7% with revision surgery as the end point).5–9 There is controversy about whether to retain or to substitute the PCL during the TKR procedure. Compared with posterior stabilized designs, the well-known advantages of cruciate-retaining TKR include the preservation of an important stabilizing structure, more consistent reconstruction of the joint line, improved stair climbing ability and greater conservation of the bone.14–17 Furthermore, the PCL assists with femoral rollback to achieve greater knee flexion.14,15 However, in 1997 Laskin and O’Flynn,10 in a series of 98 knees in patients with RA, reported that 50% of patients had posterior instability after TKR using cruciate-retaining designs, which significantly increased the revision rate. Based on these reports, many surgeons have expressed concern about preserving the PCL in patients with RA because of the perceived attenuation of the ligament in this subgroup of patients. On the other hand, Scott and colleagues18 reported that 95% of patients with RA undergoing TKR had an intact PCL and argued that the PCL should be preserved during the procedure to maximize femoral rollback. Furthermore, Archibeck and colleagues19 reported that cruciate-retaining TKR yielded satisfactory clinical and radiological results in patients with RA at a mean follow-up of 10.5 years. In 2011, Miller and colleagues7 evaluated the long-term results of 20 years of follow-up after performing cruciate-retaining TKR in patients with RA. The rate of implant survival at 20 years was 69% with revision for any reason and was 81% with prostheses revision as an end point. They argued that PCL insufficiency with instability is rarely the cause of failure.

In the present study, we found that the rate of implant survival at 10 years and 17 years after surgery was 98.7% and 83.6%, respectively, with the revision of the femoral or tibial component, including polyethylene exchange, for any reason being the end point. The rate of implant survival with revision for any reason and periprosthetic fracture as an end point was 97.6% at 10 years and 76.9% at 17 years. Our survival rates seem to be comparable to the long-term results reported by Miller and colleagues;7 however, the most common cause of revision in our series was mechanical pain associated with loosening or osteolysis of the femoral or the tibial components. There was no revision resulting from clinically proven patellofemoral joint problems or late posterior instability. Interestingly, there were several periprosthetic fractures in our study, and most occurred more than 9 years after the index surgery (mean 11.4 yr). We presume that these fractures were caused by poor bone strength and quality, which were induced by chronic steroid use and the inflammatory process of the rheumatic disease.1,4 In addition, patients with RA usually undergo joint replacement surgery at a younger age than patients with osteoarthritis.3,20 Therefore, women with RA are more likely to reach menopause after joint replacement, and this may be a reason for the sudden increased incidence of periprosthetic fracture within 10 years of TKR.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Because it was such a long-term follow-up study, a proportion of the patients died or were lost to follow-up. However, mortality after TKR is reportedly high in patients with RA, therefore many patients who were lost to follow-up may also have died.21 In addition, 3 types of prostheses were used with no uniformity, and different fixation techniques (e.g., cemented, uncemented, hybrid) were adopted in accordance with the surgeon’s preference. We did not apply a precise measuring tool to evaluate posterior instability and patellofemoral joint problems.

Conclusion

Our study provides encouraging results regarding long-term survival of cruciate-retaining TKR in patients with RA. Surgeons should be aware that patients with RA are likely to be at risk of periprosthetic fracture, which occurs at a mean of 11.4 years after the index operation.

Footnotes

The work was presented in part during the 2014 AAOS annual meeting, Mar. 11–15, 2014, New Orleans, La.

Competing interests: None declared.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. Y.M. Kee and C.H. Choi acquired and analyzed the data, which J.K. Lee also analyzed. J.K. Lee and C.H. Choi wrote the article, which all authors approved for publication.

References

- 1.Chmell MJ, Scott RD. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. An overview. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;(366):54–60. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199909000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Da Silva E, Doran MF, Crowson CS, et al. Declining use of orthopedic surgery in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? Results of a long-term, population-based assessment. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:216–20. doi: 10.1002/art.10998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JK, Choi CH. Total knee arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2012;24:1–6. doi: 10.5792/ksrr.2012.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirwan JR. The effect of glucocorticoids on joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. The Arthritis and Rheumatism Council Low-Dose Glucocorticoid Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:142–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507203330302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ranawat CS, Padgett DE, Ohashi Y. Total knee arthroplasty for patients younger than 55 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(248):27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalury DF, Ewald FC, Christie MJ, et al. Total knee arthroplasty in a group of patients less than 45 years of age. 1995;10:598–602. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(05)80202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller MD, Brown NM, Della Valle CJ, et al. Posterior cruciate ligament-retaining total knee arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a concise follow-up of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(1–6):e130. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abram SGF, Nicol F, Hullin MG, et al. The long-term outcome of uncemented low contact stress total knee replacement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Results at a mean of 22 years. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B:1497–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B11.32257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scuderi GR, Insall JN, Windsor RE, et al. Survivorship of cemented knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71:798–803. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B5.2584250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laskin RS, O’Flynn HM. The Insall Award. Total knee replacement with posterior cruciate ligament retention in rheumatoid arthritis. Problems and complications. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;(345):24–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, et al. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(248):13–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ewald FC. The Knee Society total knee arthroplasty roentgenographic evaluation and scoring system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(248):9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplan EL, Meier R. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observation. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshiya S, Matsui N, Komistek RD, et al. In vivo kinematic comparison of posterior cruciate-retaining and posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasties under passive and weight-bearing conditions. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:777–83. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fantozzi S, Catani F, Ensini A, et al. Femoral rollback of cruciate-retaining and posterior-stabilized total knee replacements: in vivo fluoroscopic analysis during activities of daily living. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:2222–9. doi: 10.1002/jor.20306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanzer M, Smith K, Burnett S. Posterior-stabilized versus cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty: balancing the gap. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:813–9. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.34814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Misra AN, Hussain MR, Fiddian NJ, et al. The role of the posterior cruciate ligament in total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:389–92. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b3.13182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott RD, Sarokhan AJ, Dalziel R. Total hip and total knee arthroplasty in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;(182):90–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Archibeck MJ, Berger RA, Barden RM, et al. Posterior cruciate ligament-retaining total knee arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:1231–6. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200108000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung HK, Choi CH, Kim JH, et al. Total knee replacement arthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis patients younger than 45 years. J Korean Orthop Assoc. 1999;34:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Böhm P, Holy T, Pietsch-Breitfeld B, et al. Mortality after total knee arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120:75–8. doi: 10.1007/pl00021220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]