Abstract

Mitochondrial respiratory chain (RC) diseases are highly morbid multi-systemic conditions for which few effective therapies exist. Given the essential role of sirtuin and PPAR signaling in mediating both mitochondrial physiology and the cellular response to metabolic stress in RC complex I (CI) disease, we postulated that drugs that alter these signaling pathways either directly (resveratrol for sirtuin, rosiglitazone for PPARγ, fenofibrate for PPARα), or indirectly by increasing NAD+ availability (nicotinic acid), might offer effective treatment strategies for primary RC disease. Integrated effects of targeting these cellular signaling pathways on animal lifespan and multi-dimensional in vivo parameters were studied in gas-1(fc21) relative to wild-type (N2 Bristol) worms. Specifically, animal lifespan, transcriptome profiles, mitochondrial oxidant burden, mitochondrial membrane potential, mitochondrial content, amino acid profiles, stable isotope-based intermediary metabolic flux, and total nematode NADH and NAD+ concentrations were compared. Shortened gas-1(fc21) mutant lifespan was rescued with either resveratrol or nicotinic acid, regardless of whether treatments were begun at the early larval stage or in young adulthood. Rosiglitazone administration beginning in young adult stage animals also rescued lifespan. All drug treatments reversed the most significant transcriptome alterations at the biochemical pathway level relative to untreated gas-1(fc21) animals. Interestingly, increased mitochondrial oxidant burden in gas-1(fc21) was reduced with nicotinic acid but exacerbated significantly by resveratrol and modestly by fenofibrate, with little change by rosiglitazone treatment. In contrast, the reduced mitochondrial membrane potential of mutant worms was further decreased by nicotinic acid but restored by either resveratrol, rosiglitazone, or fenofibrate. Using a novel HPLC assay, we discovered that gas-1(fc21) worms have significant deficiencies of NAD+ and NADH. Whereas resveratrol restored concentrations of both metabolites, nicotinic acid only restored NADH. Characteristic branched chain amino acid elevations in gas-1(fc21) animals were normalized completely by nicotinic acid and largely by resveratrol, but not by either rosiglitazone or fenofibrate. We developed a visualization system to enable objective integration of these multi-faceted physiologic endpoints, an approach that will likely be useful to apply in future drug treatment studies in human patients with mitochondrial disease. Overall, these data demonstrate that direct or indirect pharmacologic restoration of altered sirtuin and PPAR signaling can yield significant health and longevity benefits, although by divergent bioenergetic mechanism(s), in a nematode model of mitochondrial RC complex I disease. Thus, these animal model studies introduce important, integrated insights that may ultimately yield rational treatment strategies for human RC disease.

Keywords: Mitochondrial disease, nicotinic acid, resveratrol, rosiglitazone, fenofibrate, transcriptome

1. INTRODUCTION

Primary mitochondrial respiratory chain (RC) diseases comprise a heterogeneous group of genetic conditions that impair the ability to generate energy. They collectively affect at least 1 in 5,000 individuals across the lifespan, with a highly variable but often progressive array of multi-systemic symptoms (Parikh et al, 2013). The clinical features of mitochondrial RC complex I (CI) deficiency, which is the most commonly implicated biochemical site impaired in human RC disease, are broadly attributed to the central role of the RC in determining cellular NADH/NAD+ redox balance, integrating energy-generating chemiosmotic processes that include electron transport, proton flux, and ATP production, as well as modulating the balance of reactive oxygen species generation and scavenging (Haas et al, 2008). At least two critical signaling pathways interact to modulate both mitochondrial physiology and the cellular response to metabolic stress in mitochondrial disease, namely sirtuins and the peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) family of nuclear hormone receptors (Falk et al, 2011a; Hong et al, 2014; Houtkooper et al, 2012; Mouchiroud et al, 2013).

Sirtuins are a class of NAD+-dependent histone and protein deacetylases whose activity depends directly on the relative availability of NAD+ and NADH (Bitterman et al, 2002; Canto et al, 2009), metabolites whose concentrations are indirectly affected by major NAD+ consuming enzymes such as the PARP family of DNA-repair enzymes (Bai et al, 2011). PPAR family nuclear receptor activity, which transcriptionally governs lipid and glucose homeostasis (Schupp & Lazar, 2010), may also be affected by NAD+ availability and metabolic stresses, such as NAD+-dependent SIRT1 deacetylation of PPAR-γ (Ahmadian et al, 2013). Our prior work has demonstrated the direct relevance of these NAD+-dependent signaling pathways to the clinical manifestations of primary RC disease. Specifically, feeding B6.Pdss2kd/kd mutant mice, whose primary mitochondrial RC disease results from a coenzyme Q biosynthetic defect, with probucol pharmacologically activated their deficient PPAR pathway activity, improved global cellular metabolic sequelae of RC deficiency, and both prevented and rescued their otherwise lethal focal segmental glomerulosclerosis-like renal disease (Falk et al, 2011a).

Given the essential enzymatic role of mitochondrial CI to convert reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) to oxidized NAD+, an increased relative redox ratio in the cytosol of NADH to NAD+ has long been appreciated to underlie the lactic acidemia that commonly occurs in RC disease (Falk et al, 2008; Haas et al, 2008). However, disordered NAD+ metabolism has remained a relatively underappreciated pathogenic factor in the global disruption of the nutrient-sensing signaling network that occurs in CI dysfunction. We recently reported that human RC CI disease fibroblasts not only manifest an increased relative NADH:NAD+ ratio, as expected, but also have significant deficiency in the absolute cellular concentrations of both NADH and NAD+ (Zhang et al, 2013). Recognition of these secondary metabolite deficiencies in RC disease has important therapeutic implications, as we were able to show that treating the RC deficient patient cells for 24 hours with an NAD+ precursor, nicotinic acid, restored cellular NAD+ and NADH concentrations and improved total cellular mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation capacity. Targeting NAD+ deficiency in rodent models of mitochondrial myopathies has shown similar therapeutic promise (Cerutti et al, 2014; Khan et al, 2014). While this strategy may work in part by altering the disordered sirtuin and PPAR signaling that occurs in RC disease, complete mechanistic understanding remains elusive.

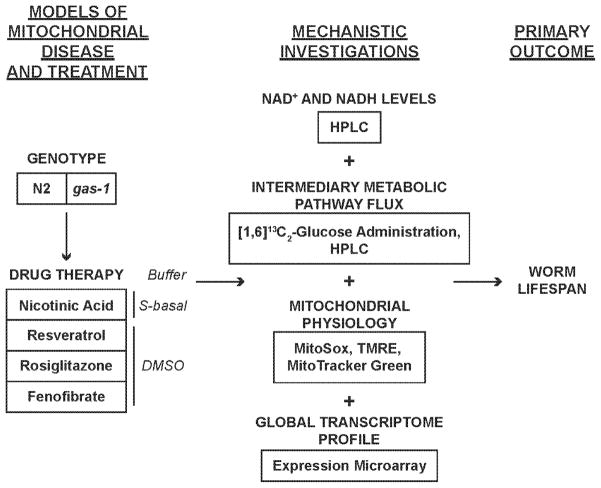

Here, we report on the in vivo effects on animal longevity and integrated metabolic consequences in a well-established Caenorhabditis elegans model of primary RC CI deficiency of pharmacologically targeting disordered sirtuin and PPAR signaling both directly, with specific transcriptional signaling modifiers, and indirectly, by increasing NAD+ metabolism via nicotinic acid supplementation. C. elegans offers a useful model system in which to efficiently characterize global sequelae of genetic-based primary mitochondrial dysfunction (Falk et al, 2008) as well as quantify multi-faceted effects and mechanisms of proposed therapeutic interventions. gas-1(fc21) is a well-characterized strain with genetic-based CI deficiency caused by a homozygous p.R290K missense mutation in the highly conserved CI subunit homologue, NDUFS2 (Kayser et al, 2001). We and others have previously shown that gas-1(fc21) is short-lived, has approximately one-third of normal mitochondrial respiratory capacity (Falk et al, 2009) with increased in vivo matrix oxidant burden and decreased in vivo mitochondrial mass and mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) (Dingley et al, 2010), as well as globally altered intermediary metabolism with significantly altered flux through key biochemical pathways (Falk et al, 2008) (Schrier Vergano et al, 2013). Based on our prior observations of altered nutrient-sensing signaling networks that occur in both human cell and mouse models of RC disease, we sought to exploit the short-lived gas-1(fc21) CI mutant worms to test the hypothesis that pharmacologic therapies that directly modulate NAD+-dependent sirtuin and PPAR signaling processes might ameliorate the diverse pathophysiologic consequences of primary RC dysfunction. Specifically, we evaluated the integrated effects of directly targeting sirtuins (with resveratrol), PPARγ (with rosiglitazone), and PPARα (with fenofibrate), as well as effects of indirectly targeting these pathways by altering NAD+ metabolism (with nicotinic acid). We evaluated effects of these therapies on animal lifespan and multi-dimensional in vivo parameters of gas-1(fc21) relative to wild-type (N2 Bristol) worms, including total nematode NADH and NAD+ concentrations, mitochondrial oxidant burden, mitochondrial membrane potential, mitochondrial content, amino acid profiles, stable isotope based intermediary metabolic flux, and global transcriptome alterations at the biochemical pathway level (Figure 1). These animal model studies thus enable improved understanding of candidate drug mechanisms and potential toxicities in the setting of primary RC deficiency, yielding insights that may ultimately facilitate rational treatment strategies for human RC disease.

Figure 1. Experimental overview of pharmacologic modulation of central sirtuin and PPAR signaling in complex I mutant worms.

We evaluated the integrated effects of targeting signaling pathways either directly (resveratrol for sirtuin, rosiglitazone for PPARγ, fenofibrate for PPARα), or indirectly by increasing NAD+ availability (nicotinic acid) on animal lifespan and multi-dimensional in vivo parameters in gas-1(fc21) mitochondrial complex I mutants relative to wild-type (N2 Bristol) worms. Mutant worms were treated with these drugs either during development and/or for the first day of adult life, after which the net effects were assessed to determine if therapies rescued the short animal lifespan of complex I (gas-1(fc21)) mutant worms. Potential in vivo mechanisms of drug therapies were assessed at the levels of intermediary metabolism (total nematode NADH and NAD+ concentrations, amino acid profiles, and stable isotope-based flux through glycolysis, pyruvate metabolism, and the tricarboxylic acid cycle), mitochondrial physiology (fluorescence studies to quantify relative mitochondrial mass with MitoTracker Green, mitochondrial matrix oxidant burden with MitoSOX, and mitochondrial membrane potential with TMRE), as well as global transcriptome profiles at the level of genes and pathways.

2. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

2.1 C. elegans strain selection

A C. elegans strain, gas-1(fc21), was studied that harbors a homozygous missense mutations in nuclear-encoded RC CI subunit, NDUFS2 (Kayser et al, 2001). N2 Bristol was the wild-type control strain studied. gas-1(fc21) was obtained as a stable mutant from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC, www.wormbase.org).

2.2 Worm lifespan analyses after treatment in development and/or young adulthood

Animals were maintained in 20°C incubators. Synchronized nematode cultures were initiated by bleaching young adults to obtain eggs. Collected eggs were allowed to hatch overnight on 10 cm, unspread, Nematode Growth Media (NGM) plates, after which L1-arrested larvae were transferred to 10 cm NGM plates spread with OP50 E. coli. Drug treatment was applied as follows: Nicotinic Acid (NA) dissolved in water was added to plates to a final concentration on NGM plates of 1 mM. Resveratrol, rosiglitazone, and fenofibrate were each dissolved in 100% DMSO and added to plates to achieve a final concentration on NGM plates of 50 μM, 5 mM, and 14 μM, respectively, with final DMSO concentration on NGM plates of 0.5%. Upon reaching the first day of egg laying, synchronous young adults were moved to fresh 3.5 cm NGM plates seeded with OP50 bacteria and treated with NA (Lifespan experiment “Day 0”). The same volume of water or DMSO was added to control animal plates. For purposes of higher-throughput lifespan screening, in order to remove the offspring of the nematodes under study from reaching adulthood, fluorodeoxyuridine (FUDR) was added to OP50-spread NGM plates to a final concentration of 100 mg/ml. Approximately 60 nematodes were studied per experimental condition, divided on three 3.5 cm NGM plates. Mortality was confirmed by stimulating nematodes lightly with a platinum wire; if the nematode did not move after stimulations, it was scored as dead and removed from the plate. Worms that died of protruding/bursting vulva, bagging, or crawling off the agar were censored.

2.3 Sample Preparation for NAD+ and NADH by HPLC after treatment in young adulthood

C. elegans were grown in liquid culture with E. coli K12 Bacteria at 200 rpm in 20°C, according to standard protocols. Worms were collected and bleached to harvest eggs, which were hatched in S. Basal (3.4 g KH2PO4,4.4 g K2HPO4, 5.85 g NaCl, 1 L water, pH 7.0) without bacteria to arrest them at the L1 stage. The L1-arrested larvae were again grown in liquid culture, and upon reaching adulthood, treated for 24 hours with nicotinic acid, resveratrol, or appropriate buffer control. After treatment, synchronous worms were washed 5 times with S. Basal to clear bacteria and any larvae, collected into two aliquots of approximately 10,000 young adults each (as determined by dilution and counting) for NAD+ or NADH analysis, and spun for at least 2 minutes at 1150 x g to pellet the nematodes. Worms were then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

For determination of NAD+ concentration, nematodes were homogenized and the cell suspension was extracted with 4 volumes of argon-bubbled ice-cold 1.2 M perchloric acid (PCA) containing 20 mM EDTA and 0.15% of sodium metabisulfite. After vortexing, the suspension was placed on ice for 15 minutes and then centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was neutralized with 1 M potassium carbonate and centrifuged to remove insoluble material. The pellet from the PCA extraction was used for protein estimation. Samples were stored at −80°C and subjected to HPLC analysis.

For determination of NADH concentration, nematodes were homogenized, and the cell suspension was extracted with 4 volumes of argon-bubbled ice-cold acetonitrile/50 mM ammonium acetate (1:1 v/v) containing 50 mM NaOH. The suspension was briefly sonicated, placed on ice for 15 minutes, and then centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 10 minutes to remove insoluble material. The supernatant was transferred to a spin column (50K MWCO) and subsequently centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 90 minutes to remove macromolecules in the sample. The eluate was transferred to a new tube and immediately subjected to HPLC analysis.

HPLC Conditions

Separation of the oxidized and reduced dinucleotides was carried out on an Adsorbosphere XL ODS column (5 um, 4.6×250 mm) preceded by a guard column at 50°C. Flow rate was set at 0.4 mL/min. The mobile phase was initially 100% of mobile phase A (0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, containing 3.75% methanol). The methanol was linearly increased with mobile phase B (0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, containing 30% methanol) increasing to 50% over 15 minutes. The column was washed after each separation by increasing mobile phase B to 100% for 5 minutes. UV absorbance was monitored at 260 and 340 nm with Shimadzu SPD-M20A. Pertinent peak areas were integrated by the LabSolution software from Shimadzu, and quantified using standard curves. Details regarding validation of the experimental design and NADH thermal stability are provided in Supplementary File 1.

2.4 Relative quantitation of mitochondrial matrix superoxide burden, mitochondrial membrane potential, and mitochondria content by fluorescence microscopy after drug treatment during young adulthood

Oxidant burden (MitoSOX Red), membrane potential (tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester, TMRE), and mitochondrial content (MitoTracker Green FM, MTG) were performed at 20°C using in vivo terminal pharyngeal bulb relative fluorescence quantitation, as previously described (Dingley et al, 2010), (Dingley et al, 2012). Briefly, synchronous populations of young adults were moved to 10 cm NGM plates spread with OP50 E. coli, a desired drug treatment (where the final DMSO concentration on NGM plates for lipid-soluble drugs was 0.1% for resveratrol and fenofibrate, and 0.5% for rosiglitazone), and either 10 uM MitoSOX Red (matrix oxidant burden), 100 nM TMRE (mitochondrial membrane potential), or 10 uM MitoTracker Green FM (mitochondria content) for 24 hours. The next day, worms were transferred by washing in S. basal onto 10 cm plates spread with OP50 E. coli without dye for one hour to allow clearing of residual dye from the gut. Worms were then paralyzed in situ with 10 mg/ml levamisole. Photographs were taken in a darkened room at 160X magnification with a Cool Snap cf2 camera (Nikon, Melville, NY). A CY3 fluorescence cube set (MZFLIII, Leica, Bannockburn, IL) was used for MitoSOX and TMRE. A GFP2 filter set (Leica) was used for MitoTracker Green FM. Respective exposure times were 2 seconds, 320 ms, and 300 ms for each of MitoSOX, TMRE, and MitoTracker Green FM. The nematode terminal pharyngeal bulb was manually circled and mean intensity of the region was quantified using NIS Elements BR imaging software (Nikon, Melville, NY). A minimum of 3 independent experiments of approximately 60 animals per biological replicate were studied per strain and treatment.

2.5 Whole-worm free amino acid profiling after drug treatment during development and/or young adulthood

Whole worm free amino acid profiling was assessed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) in the Metabolomics Core Facility at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute, as previously described (Falk et al, 2008). In brief, populations of 2,000 early larval stage (L1) worms were grown on NGM plates. When worms reached young adult stage, they were treated for 24 hours with an NAD+/PPAR-modifying drug or control in identical buffer (1 mM nicotinic acid, 50 μM resveratrol, 5 mM rosiglitazone, 14 μM fenofibrate). The final DMSO concentration for lipid-soluble drugs on NGM plates was 0.4%. Whole worm population free amino acid quantitation was performed by direct injection of 50 μL of neutralized sample into HPLC (Varian) using pre-column derivatization with o-phthalaldehyde and fluorescent detection (Jones & Gilligan, 1983). Raw HPLC data was normalized to worm protein concentration and reported as nmol/mg protein. At least three biologic replicate analyses were performed per strain/treatment.

2.6 Whole worm isotopic enrichment in free amino and organic acids after treatment during young adulthood by isotope ratio MS

Intermediary metabolic flux analysis was adapted from previously published methods (Falk et al, 2011b). In brief, for experiments conducted entirely on plates, populations of 2,000 early larval stage (L1) worms were grown on NGM plates. For liquid culture experiments, populations of 2,000 early larval stage (L1) worms were grown on NGM plates, until they reached the first day of egg-laying, when they were transferred to liquid culture. 10 mMol of [1,6]13C2-glucose stable isotope was added to plates and/or liquid culture beginning at the L1-stage of development. When worms reached young adult stage, they were treated for 24 hours with an NAD+/PPAR-modifying drug or control in identical buffer (plates: 1 mM nicotinic acid, 50 μM resveratrol, 5 mM rosiglitazone, 14 μM fenofibrate; liquid culture: 1 mM nicotinic acid, 50 μM resveratrol, 1 mM rosiglitazone). Following 24 hours of incubation with a drug, worms were washed clear of bacteria with three volumes of 50 mL S. Basal. Worm number was estimated by counting (Dingley et al, 2010). All samples were obtained in at least biological triplicate experiments, as shown. Metabolic reactions were stopped by the addition of 20 nmol internal standard (e-aminocaproic acid, 16.7 μmol/L) and 4% perchloric acid (PCA) final concentration. Samples were ground using a plastic homogenizer and motorized drill until visual inspection confirmed worm disruption. Precipitated protein was removed, re-dissolved in 1 normal NaOH, and protein concentration was determined by DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad). Remaining neutralized samples after HPLC analysis were extracted using ion exchange resin (Bio-rad) in AG50 and AG1 columns, respectively, to measure the relative enrichment in amino acids and organic acids, by isotope ratio mass spectrometry (MS), as previously described (Falk et al, 2008). Isotope ratio MS analyses were performed in the Metabolomics Core Facility at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute. Stable isotopic enrichment was calculated in Excel (Microsoft) for each species according to the following formula: Atom Percent Excess, corrected (APE) = (Rsa-Rst)*100/[(Rsa-Rst)+100], where Rsa = ratio of the sample and Rst = ratio of the standard.

2.6 Preparation of worm total RNA for microarray and analysis of microarray data

Worms were grown and treated on NGM plates for transcriptome profiling studies, per drug treatment conditions described above. Total RNA was extracted from synchronous young adult worm populations for global nuclear genome expression (transcriptome) profiling using the Affymetrix GeneChip C elegans platform. Genome array hybridization was performed, and data analyzed, as previously described (Falk et al, 2008). In particular for these experiments, 4 replicates were performed for each drug treatment as compared to the appropriate solvent control that was prepared in parallel, both for samples in which treatment was begun at the L1 stage of development and in which treatment was begun in young adulthood and continued for in both conditions until 24 hours of adult life. The final DMSO concentration for lipid-soluble drugs on NGM plates was 0.4%. RNA quality was confirmed via Agilent bioanalyzer, where RIN >8 was required for downstream analysis. All Affymetrix probes were re-grouped into unique Entrez gene IDs using custom library file downloaded from BRAINARRAY database (http://brainarray.mbni.med.umich.edu). The raw data in.CEL files were normalized and summarized by RMA (Robust Multichip Averaging) method to generate a data matrix for statistical analysis. At most, one outlier replicate was excluded based on principal components analysis for each condition. Differential expression of genes between N2 and gas-1(fc21) worms, or between drug treated and untreated gas1(fc21) worms, was ranked by the Rank Product method (Breitling et al, 2004). The ranked gene list of each group comparison was imported into the gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) software tool (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea) to identify KEGG pathways showing concordant changes by drug treatment.

2.7 Statistical Analyses

For survival analyses, Cox proportional hazard modeling was used to pool the results of independent trials and Log-Rank test was performed to assess the effect of each drug on survival. For metabolite analysis, the significance of the difference in the mean analyte level between strain or treatment group was assessed by mixed-effect ANOVA (JMP version 10, SAS Institute, Cary NC), which takes into account potential batch effect due to samples being experimentally prepared (as relates to worm feeding through PCA extraction and subsequent sample separation into amino acid and organic acid fractions) and analyzed by HPLC and IR/MS machines on different days by including a batch random effect in the model. This model assumes the measures completed on the same day are more closely correlated compared to those completed on different days. For the HPLC analysis of NAD+ and NADH levels, we present the concentrations as normalized to the appropriate within-assay comparator, which was same-day untreated gas1(fc21). For this reason, we used a one-sample t-test with pooled error to assess whether the ratio of NAD+ or NADH in the treated vs untreated condition was significantly different from 1. A ratio of 1 between the treated and untreated conditions represents the null hypothesis of no change attributable to treatment.

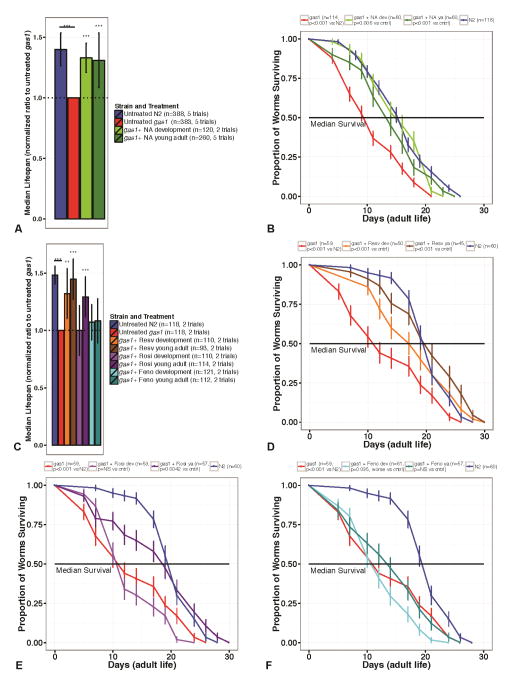

To generate the integrated effects map (Figure 7), the effects of strain (e.g., N2 vs gas-1(fc21)) or treatment (nicotinic acid, resveratrol, rosglitazone, and fenofibrate) of young adult worms were scaled within each of the measured parameters to enable all variables to be represented on the same map: lifespan (median days), mitochondrial content or number (as indicated by in vivo fluorescence measurements of MTG uptake), mitochondrial potential (as indicated by in vivo fluoresence measurements of TMRE uptake), NAD+/NADH (concentration relative to total protein), BCAA (amino acid concentration relative to total protein), mitochondrial oxidant burden (as indicated by in vivo fluorescence measurements of MitoSox Red), transcriptional effects (all represented by net enrichment score, NES). Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 and R 3.0.0.

Figure 7. Data integration heatmap to visually convey overall drug efficacy on animal lifespan and their major mechanisms of action on mitochondrial physiology, NAD+/NADH metabolism, branched chain amino acid metabolism, and oxidative stress.

Diverse data types were reduced to heatmaps that visually convey the multi-dimensional effects of each of the pharmacologic treatments studied. Each of the five rows represents one aspect of animal physiology: lifespan, mitochondrial physiology, NAD+/NADH metabolism, BCAA metabolism, or oxidative stress. The first two columns represent untreated wild-type and gas-1(fc21) mutant worms. The last four columns represent effects of 24 hour treatments of adult gas-1(fc21) mutant worms with each of the drugs shown (nicotinic acid, NA; resveratrol, Resv; rosiglitazone, Rosi; fenofibrate, Feno). Red and green indicate a relative increase or decrease, respectfully, for the measured parameter as compared across all 6 columns. The results across each assay (i.e., nematode median lifespan, mitochondrial physiologic parameters, NAD+ and NADH concentrations, etc.) were scaled across all trials such that the red represents the highest observed value, and the green represents the lowest observed value. In this way, relative differences between drug treatments become more readily apparent across assay and treatment condition. The top row, Row 1 shows overall lifespan effect, where N2 wild-type worms have a longer (red) lifespan relative to gas-1(fc21) worms (green). Nicotinic acid (NA), resveratrol (Resv), and rosiglitazone (Rosi) each tends to restore gas-1(fc21) lifespan towards that of wild-type (red). Rows 2–5 each conveys the overall effect on complementary aspects of a given physiologic parameter (top) and a corresponding transcriptional pathway (bottom). For example, in Row 2, the top left corner of each box indicates relative mitochondrial number (mass) in each condition, the top right corner of each box indicates relative mitochondrial potential, and the bottom box indicates the overall effect on the expression of genes related to oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Ala, alanine. Asp, aspartate. Glu, glutamate.

3. RESULTS and DISCUSSION

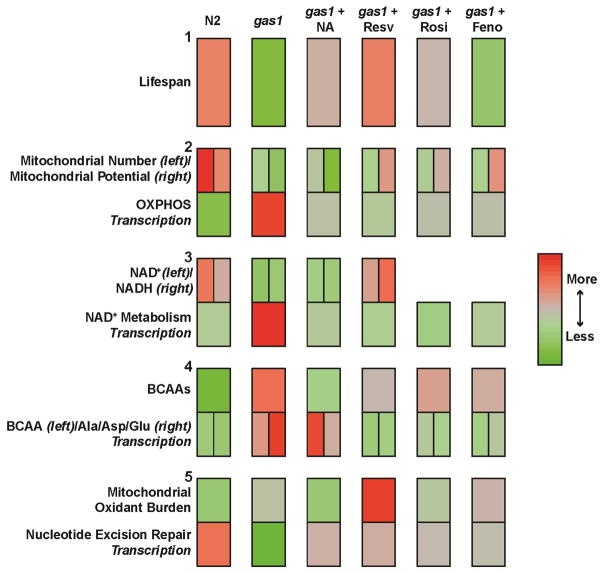

3.1. Treatment with nicotinic acid (NA) or resveratrol significantly improves animal longevity in gas-1(fc21) mutant worms regardless of stage when initiated, while rosiglitazone improves survival only when initiated at adult stage

gas-1(fc21) mutant worms are significantly short-lived relative to wild-type (N2 Bristol) animals (Figure 2a–f). Their nearly 60% reduction in median lifespan was significantly improved by 1 mM nicotinic acid (NA) whether begun in early development from the L1 stage and continued throughout adult life (Cox proportional hazards model, p=0.002) or initiated in young adulthood on day 1 of egg laying (p<0.001), as per the median lifespan data shown in Figures 2a and 2b, as well as the additional survival curve shown in Supplemental Figure 1a. There was no toxicity of NA administered during nematode development and timing of treatment initiation did not influence efficacy. NA treatment of wild-type worms did not change their survival (data not shown). Resveratrol (50 μM) improved survival to near indistinguishable from wild-type worms regardless of stage at which treatment was initiated, with treatment initiated in young adulthood (p<0.001) sufficient to produce this beneficial lifespan effect (Figures 2c, 2d, and Supplemental Figure 1b). In contrast, rosiglitazone (5 μM) exerted a stage-specific effect on survival in gas-1 mutant worms, where no lifespan benefit was seen when treatment was begun at the L1 developmental stage but treatment initiated in young adulthood significantly improved their median survival (p=0.002 versus untreated gas-1(fc21)) (Figures 2c, 2e, and Supplemental Figure 1c). Fenofibrate (14 μM) did not produce a survival benefit in gas-1(fc21) whether administered either from early development or first begun only in young adulthood (Figures 2c, 2f, and Supplemental Figure 1d), although substantial reduction of animal fat content was observed (data not shown).

Figure 2. Lifespan effects of sirtuin- and PPAR-modifying drugs in gas-1. Median survival of (A) Nicotinic acid and (C), Resveratrol, Rosiglitazone, Fenofibrate.

Median survival is shown as a normalized ratio relative to untreated gas-1(fc21) mutant control, appropriately matched for water-based or lipophilic solvent (S-basal for nicotinic acid or DMSO for resveratrol, rosiglitazone and fenofibrate). Error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals for the median survival estimate. Cox proportional hazard modeling was used to pool the results of independent trials and Log-Rank test was performed to assess the effect of each drug on survival; ***, p<0.001. The number of worms (n) included and number of independent trials performed is detailed for each treatment condition. Worms were treated with drugs beginning either in early development or on the first day of young adult life with 1 mM nicotinic acid (NA) (A), or resveratrol 50 μM (Resv), rosiglitazone 5 mM (Rosi), and fenofibrate 14 μM (Feno) (C). Dotted line indicates relative value for untreated gas-1(fc21) mutant control. Nicotinic acid, whether initiated in development or in adulthood, restored median survival of gas-1(fc21) mutant worms towards wild-type. Lifespan curves for (B) Nicotinic acid and (D-F) Resveratrol, Rosiglitazone, Fenofibrate. Lifespan curves for representative replicate experiments of (B) nicotinic acid (NA), (D) resveratrol, (E) rosiglitazone, and (F) fenofibrate treatment in gas-1(fc21). Worms treatments were the same as described above. n, number of worms per condition. X-axis shows time in days of young adult life. Log-Rank test was performed to assess the effect of each drug on survival. The p-value for each specified comparison is shown. The solid black line denotes median survival. Results of replicate studies are reported in Supplementary Materials.

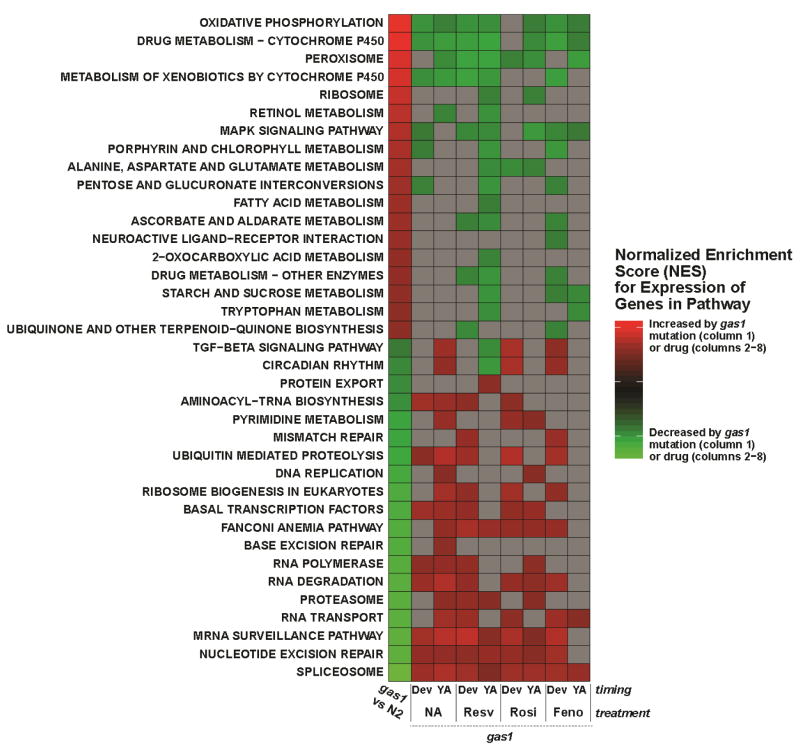

3.2 Sirtuin and PPAR modifying treatments reverse transcriptome alterations at the intermediary metabolic and cell signaling pathway level in CI deficient gas-1(fc21) worms

gas-1(fc21) adult worms have global transcriptome changes

As we have previously observed (Falk et al, 2008), global transcriptome changes occur in gas-1(fc21) relative to wild-type N2 Bristol adult worms (Figure 3). Many of the most up-regulated pathways likely reflect a coordinated attempt to reverse cellular energy deficiency that results from CI dysfunction, including pathways involved in oxidative phosphorylation itself, as well as fatty acid metabolism, 2-oxocarboxylic acid metabolism, alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism, and pentose and glucuronate interconversions. Interestingly, while the “ribosome” pathway was significantly up-regulated, the “ribosomal biogenesis in eukaryotes” pathway was strongly down-regulated. Further analysis of these pathway-level changes revealed that whereas differential expression of mitochondrial ribosomal protein genes drove the overall signal for ribosome pathway up-regulation, adding the balance of ribosome assembly co-factors into the analysis resulted in a net decrease in ribosomal pathway expression. Key pathways that convey signals and/or process products of metabolic stress (MAPK, peroxisome) were also increased in gas-1(fc21) mutants, while pathways necessary for coordinated control of the cell cycle and differentiation were down-regulated, including those affecting proteins (proteasome, protein export, ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis), RNA (RNA polymerase/degradation/repair, spliceosome, mRNA surveillance, amino-acyl tRNA biosynthesis) and DNA (DNA replication, base and nucleotide excision repair, homologous recombination) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Transcriptional changes in gas-1(fc21) mutant worms related to treatment with sirtuin or PPAR- modifying drugs throughout development and/or only in young adulthood.

The heatmap shows biological pathways that were significantly (p < 0.05) dysregulated in gas-1(fc21) worms and reversed by at least one drug treatment. Color scale corresponds to normalized enrichment score (NES), which conveys the relative enrichment of each pathway between the indicated group comparisons as normalized for the number of genes in each pathway. Red and green cells highlight increased and decreased expression, respectively, in mutant relative to wild-type animals (first column) or specific drug treated relative to untreated mutants (columns 2–9). Gray cells indicate pathways whose transcription were not statistically significantly altered by a given drug treatment. Treatments were begun either in development through the first 24 hours of life (Dev) or for 24 hours beginning in synchronous young adult worms (YA). NA, 1 mM nicotinic acid. Resv, 50 μM resveratrol. Rosi, 5 mM rosiglitazone. Feno, 14 μM fenofibrate.

Transcriptome effects of sirtuin and PPAR modulating therapies in gas-1(fc21) mutant worms

Treatment of gas-1(fc21) mutant worms beginning in either early larval development (“development”) or at the young adult stage (“young adult”) with each of these pharmacologic agents consistently and significantly reversed their hallmark up-regulation of the oxidative phosphorylation pathway (Falk et al, 2008), with one exception, as rosiglitazone only reversed the upregulation of the oxidative phosphorylation pathway of gas-1(fc21) worms when begun in adulthood. This discrepancy is consistent with rosiglitazone only conferring lifespan benefit when begun in adult stage gas-1(fc21) worms (Figures 2c and 2e). Interestingly, fenofibrate reversed up-regulation of the oxidative phosphorylation pathway without conferring lifespan benefit. This could relate to our observation that chronic fenofibrate treatment depleted animal fat stores in the gas-1(fc21) mutant animals, an effect that may potentially override any acute benefit of oxidative phosphorylation pathway expression normalization detected by studying 24 hour treatment effects on the transcriptome. Resveratrol administered from early development in gas-1(fc21) also consistently reversed many of the mutant animals’ characteristic intermediary metabolic pathway transcriptome responses, including its compensatory up-regulation of amino acid, fat, and other nutrient (starch, sucrose, pentose, glucuronate) metabolic pathways that presumably comprise an adaptive metabolic response to chronic CI dysfunction. In contrast, these effects were not observed with either NA or rosiglitazone. All treatments begun in young adulthood tended to reverse characteristic gene expression changes in nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism, although this result did not achieve statistical significance.

Most of the drugs tested either had no effect or reversed the pathway whose expression were down-regulated in gas-1(fc21) relative to wild-type (N2) animals (Figure 3, bottom half). In particular, all drug treatments restored gas-1(fc21) animals’ wild-type expression level of genes involved in DNA and RNA processing and repair, where the splicesome was the most downregulated pathway in gas-1(fc21) worms (Figure 3, column 1) and normalized by all treatment regimens tested. However, whereas nicotinic acid treatment from young adulthood significantly normalized expression in the TGF-β pathway and the circadian rhythm pathway (Figure 3, columns 1 and 3), as did rosiglitazone or fenofibrate when begun in early development (Figure 3, columns 6 and 8, respectively), no similar reversal occurred with resveratrol. Rather, treating gas-1(fc21) worms with resveratrol from young adulthood further exacerbated their downregulation of the TGF-β and circadian rhythm pathways (Figure 3, columns 1 and 5). TGF-β pathway activity may play a role in sensing local nutrient availability and signaling behavioral decisions that direct animals to either seek food or rest (Ben Arous et al, 2009), whereas the circadian rhythm pathway impacts overall energy balance by governing periods of activity and quiescence. Indeed, there is increasing evidence to suggest circadian rhythmicity occurs in C. elegans (Nelson et al, 2013), although the in depth response of this system to respiratory chain perturbation remains to be explored. Further, circadian variation in NAD+ availability has recently been suggested to modulate SIRT3-dependent acetylation patterns, which, in turn, effect mitochondrial metabolism and facilitate synchronization of diurnal rhythms to feeding and fasting patterns in mice (Peek et al, 2013). Thus, these data are suggestive that while both nicotinic acid and resveratrol activate sirtuins, only nicotinic acid also repletes NAD+ bioavailability, which appears necessary to normalize circadian rhythm signaling.

Transcriptome and metabolic effects of the DMSO solvent in gas-1(fc21) mutant worms

We assessed the transcriptome effects of buffer exposure to 0.4% DMSO (which is the buffer used to dissolve the lipophilic drugs in the present study) or standard S. basal water-soluble beginning in either the L1 larval stage or young adulthood (Supplementary Figure 1). Most notably, exposure to 0.4% DMSO, particularly from the L1 larval developmental stage, significantly reduced transcription of genes related to cuticle formation. The implications of this finding are that, in addition to drug-specific effects, results may be influenced by the effects of the DMSO solvent in potentially diminishing the integrity of the animal’s protective outer barrier. This highlights the importance of using a same-buffer control condition for both mutant and wild-type strains, as was performed throughout all present studies.

3.3 Drug treatment effects on in vivo mitochondrial physiology of gas-1(fc21) mutant worms

Effects on mitochondria-specific physiology were studied following 24 hour supplementation of gas-1(fc21) mutant young adult worms with sirtuin and PPAR modifying drugs by in vivo fluorescence quantitation of relative matrix oxidant burden with MitoSOX, mitochondrial membrane potential with tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE), and mitochondrial mass with MitoTracker Green FM (Dingley et al, 2010).

In vivo mitochondrial oxidant burden in gas-1(fc21) is normalized by NA but exacerbated by resveratrol and fenofibrate

The characteristic increased mitochondrial oxidant burden of gas-1(fc21) worms was modestly decreased toward wild-type by 24-hour treatment in young adults with NA (18%, p<0.0001) (Figure 4). However, matrix oxidant burden was substantially increased by treatment with either resveratrol (49%, p<0.0001) and to a lesser extent, fenofibrate (8%, p=0.01) (Figure 4). Rosiglitazone had no effect on matrix oxidant burden (Figure 4). Resveratrol has previously been shown to increase oxidative stress resistance in worms (Gruber et al, 2007), a finding which typically implies an effect on animal behavior or viability upon exposure to known oxidizing agents, and expected to correlate with upregulated oxidative scavenging systems and reduced overall oxidant burden. As “oxidant burden” is both highly dynamic, and compartmentalized, it is often a phenomenon assessed at the cellular or tissue level rather than within specific organelles such as mitochondria. Given the unexpected finding that resveratrol increases mitochondrial oxidant burden in gas-1(fc21) mutant worms, we propose several possible explanations. First, while we assessed mitochondrial matrix-specific oxidant burden 24 hours after treatment in gas-1(fc21) animals, it is possible an anti-oxidant effect of resveratrol treatment would become apparent later in its adult life. It is also possible the initial increase in mitochondrial matrix oxidant burden observed in the gas-1(fc21) mutants produces hormetic signals through stress resistance pathways that ultimately yield a net protective effect (Ludewig et al, 2013). Finally, since we observed resveratrol to also increase the mitochondrial membrane potential of gas-1(fc21) mutant worms, their increased mitochondrial oxidant burden might relate to the rapid increase in ADP-induced mitochondrial respiration, which has been shown in other studies to occur with resveratrol treatment (Price et al, 2012), prior to the complete and effective induction of the animals’ anti-oxidant defenses. In contrast to resveratrol, NA treatment did not increase either mitochondrial oxidant burden or mitochondrial membrane potential at the 24 hour of young adult life time point studied here. Taken together, these findings underscore the generally accepted concept that while higher oxidant levels may be associated with shortened lifespan, in many instances oxidative stress and longevity can be uncoupled (Van Raamsdonk and Hekimi, 2010).

Figure 4. In vivo fluorescence analysis of relative mitochondrial oxidant burden, membrane potential, and mitochondrial content in gas-1(fc21) mutants treated with sirtuin/PPAR modifying drugs.

Mitochondrial content, Mitochondrial membrane potential, and Mitochondrial oxidant burden were assessed by in vivo fluorescence terminal pharyngeal bulb (PB) relative fluorescence quantitation using MitoTracker Green FM (MTG), TMRE, or MitoSOX (SOX), respectfully. Each drug was compared to the appropriately treated control (i.e., gas-1(fc21) with either S-basal/water for nicotinic acid or low concentration DMSO for all other drugs). Within-experiment effect of strain and treatment were assessed by pooling standard errors and performing a one-sample t-test; p value conveys the significance of the difference between untreated N2 and untreated gas-1(fc21) (strain effect) or the difference between gas-1(fc21) plus drug and untreated gas-1(fc21) (treatment effect). For each parameter, each drug treatment assay was repeated in 3 to 6 independent trials, with ~60 worms per trial. Bars and error bars convey mean +/− SEM. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***; p < 0.001 versus concurrent gas-1(fc21) control. Dotted line highlights relative value for untreated gas-1(fc21) mutant control.

In vivo mitochondrial membrane potential in gas-1(fc21) is further decreased by NA but restored by resveratrol, rosiglitazone, and fenofibrate, without changing mitochondrial mass

The reduced mitochondrial membrane potential of gas-1(fc21) worms was significantly increased toward wild-type on the order of 40% – 50% by 24 hour treatment in young adults with either resveratrol, rosiglitazone, or fenofibrate (p<0.0001 for each) (Figure 4). NA appeared to mildly exacerbate the reduced relative membrane potential in gas-1(fc21) when assessed with TMRE quantitation (~10% decrease, p=0.002) (Figure 4), although this finding may be reflective of a potential experimental effect of the reduced pH caused by NA on the membrane-potential sensitive TMRE dye. Relative quantitation of MitoTracker Green FM fluorescence to assess mitochondrial content in young adult worms treated for 24 hours with each of the drugs revealed no significant differences (Figure 4), suggesting that the physiologic effects on mitochondrial oxidant burden (which reflects the product of oxidant generation and scavenging) and RC-dependent mitochondrial membrane potential precede any eventual alterations in mitochondrial mass that may potentially contribute to their effects on gas-1(fc21) longevity (Figure 2). Similarly, we have shown previously that NA treatment for 24 hours in human CI-deficient patient fibroblast cells that was sufficient to restore cellular oxidative phosphorylation capacity did not alter cellular mitochondrial content by that time, as was measured by cellular citrate synthase activity in both intact and digitonin-permeabilized cells (Zhang et al, 2013).

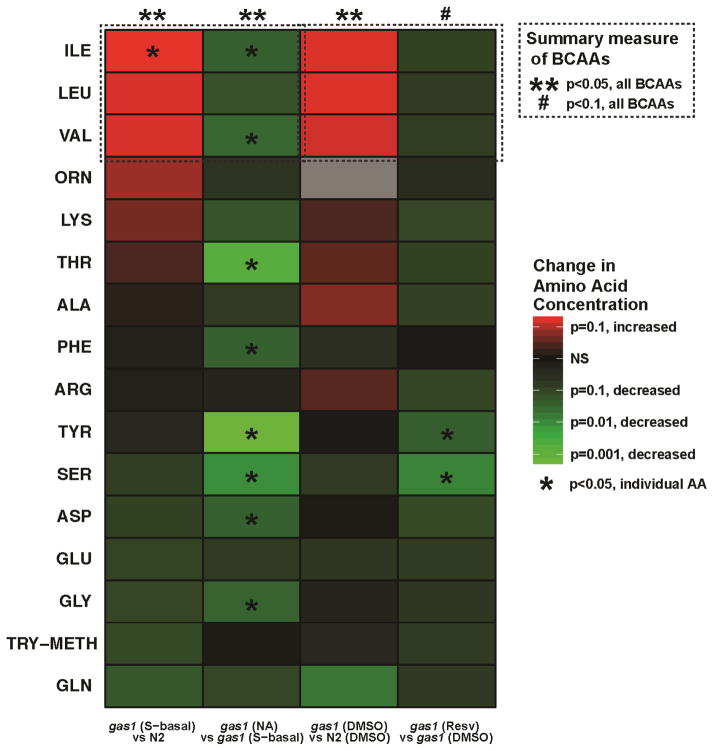

3.4 Free amino acid concentrations are altered by sirtuin and PPAR modifying therapies in gas-1(fc21) worms

Increased branched chain amino acid concentrations in gas-1(fc21) young adult mutants are reduced by NA

As we have previously shown (Falk et al, 2008; Schrier Vergano et al, 2013), we again observed that significantly increased whole worm concentrations of the branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs: leucine, isoleucine and valine) occur in gas-1(fc21) mutants relative to wild-type N2 worms (Figure 5). Collectively, BCAA levels are significantly reduced by NA (Figure 5). Specifically, when administered to young adult worms, NA significantly reduced isoleucine and valine concentrations in gas-1(fc21), with a marginal reduction in leucine concentration (p=0.06) (Figure 5, Supplementary Figure 2a). Levels of many other amino acids were also reduced by NA, including threonine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, serine, aspartate, and glycine. Overall, these data are suggestive that NA treatment increases available cellular NAD+ pools (see Figure 6a), as would be expected to normalize their oxidation of BCAAs and alanine to alpha-ketoacids, rather than drive the reverse enzymatic reactions that occur when NADH accumulation leads to their parent amino acid formation in primary RC disease (Falk et al, 2008). Resveratrol treatment resulted in a non-significant trend toward normalization of the gas-1(fc21) mutant animals’ hallmark constellation of increased BCAAs and alanine following 24-hour treatment in young adults (Figure 5). Statistical interpretation of these data is likely impacted by the high degree of variance between individual replicates, especially when worms were grown in DMSO buffer (Supplementary Figure 3 depicts individual results of three biological replicate experiments for the whole worm free amino acid measurements, along with corresponding enrichment measurements). While glutamate levels seem to decline further with resveratrol treatment in gas-1(fc21), ratios of BCAAs and alanine levels expressed relative to glutamate (Falk et al, 2008) remained unchanged when compared to that of untreated gas-1(fc21) (data not shown). No significant alterations in whole worm free amino acid concentrations in gas-1 mutant worms resulted from treatment with either fenofibrate or rosiglitazone (Supplementary Figure 3), although high data variance in these DMSO-soluble therapies may a potential contributing factor.

Figure 5. Whole worm free amino acid concentration summary heatmap showing drug effects in young adult gas-1 worms grown on NGM plates following 24 hours of treatment with nicotinic acid or resveratrol.

gas-1(fc21) effects were compared to N2 raised in identical solvent. Treatment effects were compared to untreated gas-1(fc21) in identical solvent. Amino acid concentrations were normalized to overall protein concentration, and then compared to same-day controls. Random effects ANOVA was used to account for experimental batch effects. Red and green color conveys increased or decreased, respectfully in first compared to second strain listed in each column. Color intensity corresponds to effect significance (-log p-value). Gray boxes indicate insufficient data for statistical analysis. As branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) elevation are characteristically elevated in gas-1(fc21) mutants, treatment effects were also considered for BCAAs as a group, with significance as indicated in figure key. NS, not significant. For details of individual metabolites and assays, see Supplementary Figure 3.

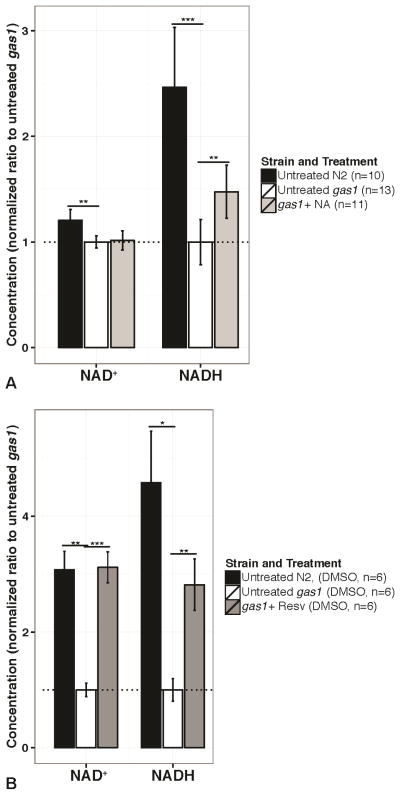

Figure 6. NAD+ and NADH concentrations are reduced in gas-1(fc21) worms and restored by pharmacologic modulation of sirtuin and/or PPAR signaling.

Bars convey mean and error bars represent +/− SEM, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by one-sample t-test for within-experiment effect of strain or treatment with pooled variance. Dotted line indicates relative value for untreated gas-1(fc21) mutants. (A) Nicotinic acid (NA) treatment (1 mM, 24 hours). NAD+ and NADH deficiency exists in gas-1(fc21) mutants as compared to wild-type worms. NAD+ is not restored by NA treatment, but NADH is restored. (B) Resveratrol treatment (50 μM, 24 hours). NAD+ and NADH deficiency may be exacerbated by the DMSO buffer (see Supplementary Figure 2). Resveratrol treatment restores NAD+ and NADH concentrations towards wild-type.

Serine and tyrosine concentrations in gas-1(fc21) young adult mutants are reduced by NA or resveratrol

Like NA, resveratrol treatment of adult gas-1(fc21) mutants also significantly decreased serine and tyrosine. With respect to serine, worms have an ortholog of the human serine pyruvate aminotransferase (SPT) (CELE_T14D7.1) that catalyzes the conversion of serine and pyruvate to 3-hydroxypyruvate and alanine. In rats, mitochondrial SPT is induced by glucagon, presumably to induce gluconeogenesis (Oda et al, 1982; Xue et al, 1999). Thus, altered serine metabolism may also contribute to the observed increase in alanine that is characteristic of RC impairment. Resveratrol treatment, by signaling through AKT and FOXO1, may effectively increase flux through gluconeogenesis (Park et al, 2010), thereby leading to a reduction in accumulated serine levels. With respect to tyrosine, worms also contain orthologous genes responsible for the metabolism of tyrosine, which may directly affect the activity of stress and longevity pathways including daf-2/insulin signaling and daf-16/FOXO (Ferguson et al, 2013), which we have previously implicated in the cellular response to RC impairment (Zhang et al, 2013).

Sirtuin and PPAR modifying therapies do not significantly improve characteristic intermediary flux alterations as assessed by stable isotope profiling in gas-1(fc21) worms

Neither glucose-derived amino acid flux (as shown in Supplementary Figure 3a) nor organic acid flux (data not shown) experiments appeared consistently altered by sirtuin or PPAR modifying therapies. This result may relate to the considerable heterogeneity that exists in intermediary metabolic flux through glycolysis, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, and the tricarboxylic acid cycle in gas-1(fc21) worms (Schrier Vergano et al, 2013). This variability may potentially be related to their relative fragility that is exacerbated by exposure to the DMSO solvent that may alter cuticle permeability, as discussed above.

Taken together, metabolomics profiling results suggest that NA and resveratrol may at least partially normalize the characteristic metabolic signature of gas-1(fc21) relative to wild-type worms, particularly with respect to elevated BCAA concentrations that may be caused by altered NAD+ metabolism.

3.5 NA or resveratrol treatments restore deficient NAD+ and/or NADH metabolite levels in gas-1(fc21) mutant worms

Absolute NAD+ and NADH deficiencies occur in gas-1(fc21) mutant worms

Our previous, and current, metabolomics analysis in gas-1(fc21) mutant worms suggested that failure of NAD+-dependent ketoacid oxidation occurs in primary RC mutants (Falk et al, 2008). This observation raised the possibility not only of altered cellular redox balance due to an increased NADH to NAD+ ratio, but also of absolute deficiencies of cellular NADH and NAD+ concentrations. To determine whether restoration of redox metabolite concentrations and/or their balance might underlie the beneficial survival effects of NA and resveratrol supplementation in gas-1(fc21) animals (Figure 2) we developed a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method to quantify concentrations of NADH and NAD+ in gas-1(fc21) and wild-type synchronized young adult worm populations at baseline and following 24 hours of drug treatment. Relative to wild-type worms, gas-1(fc21) mutant worms had significant deficiencies in total concentrations of both NADH (p=0.0003, one-sample t-test) and NAD+ (p=0.002, one-sample t-test) when animals were tested using a standard water-based balanced salt solution, S. basal (Figure 6a). An expected direct cellular consequence of complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) inhibition is relative accumulation of NADH. However, the net effect on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide metabolism of long-standing complex I deficiency in gas-1(fc21) mutant worms seems to be global decreases of both NAD+ and NADH concentrations. NADH deficiency could result from failure to generate these essential reducing equivalents, perhaps as a compensatory response in attempt to decrease ongoing reactive species generation. Support for this possibility is suggested by the markedly increased lactate formation that could reflect reduced TCA cycle flux in gas-1(fc21) mutants, as our stable isotope experiments have previously suggested (Schrier Vergano et al, 2013). Indeed, high pyruvate concentrations or decreased pH can shift the lactate dehydrogenase reaction equilibrium towards lactate production. Interestingly, when worm samples were prepared in a low-concentration (0.1%) DMSO-based buffer necessary to dissolve lipophilic drugs, more pronounced deficiencies of both NAD+ and NADH deficiency were noted in gas-1(fc21) worms (p=0.001 and p=0.01, respectively, by one-sample t-tests) (Figure 6b, Supplementary Figure 2), perhaps suggestive of an already compromised cuticle integrity existing in the mutant animals that becomes further exacerbated by DMSO. Indeed, no similar buffer effect of DMSO relative to S. basal was observed on NAD+ and NADH concentrations in wild-type (N2 Bristol) worms (Supplementary Figure 2).

Treatment with NA or resveratrol raises NAD+ and NADH concentrations in gas-1(fc21) worms

Interestingly, NA restored only NADH concentration in gas-1(fc21) worms (Figure 6a, p=0.001, by one-sample t-test), which may suggest that the NAD+ formed from NA supplementation is either consumed and/or reduced to NADH. In contrast, resveratrol treatment (Figure 6b) significantly increased concentrations of both NAD+ (p=0.009, by one-sample t-test) and NADH in gas-1(fc21) worms (p=0.01, by one-sample t-test). Taken together, these data suggest that total nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide levels in CI deficient animals were sufficiently repleted by NA treatment, and effectively restored by resveratrol treatment perhaps by downstream effects that reduce NAD+ consumption, to effectively bypass cellular reliance on CI-generated NAD+. At low doses, resveratrol may stimulate NADH dehydrogenases, and thus increase NAD+ levels that, in turn, promote anaplerosis (Desquiret-Dumas et al, 2013). Alternatively and/or in addition, the relative benefit of resveratrol as compared to NA on NAD+ levels may be related to the more pronounced NAD+ depletion that occurs in DMSO solvent(Supplementary Figure 2a), a finding that may relate to DMSO-induced oxidative stress (Frankowski et al, 2013). Given the known role of some of the mammalian NAD+-dependent sirtuin pathway members in mammalian mitochondrial biogenesis, we postulated that it is also plausible that sufficiently increased mitochondrial (and RC CI) content occurred in the gas-1(fc21) mutant animals with NA or resveratrol treatment to restore total nematode redox balance despite their inherent CI enzyme deficiency within each mitochondrion. However, relative quantitation of nematode pharyngeal bulb MitoTracker Green fluorescence in gas-1(fc21) adult worms treated with either drug therapy (Figure 4) showed no change in mitochondrial mass by the same 24-hour time point at which NAD+ and/or NADH metabolite concentrations were shown to be significantly increased (Figure 6). Further, while known sirtuin family members include seven in mammals and four in C. elegans (Viswanathan & Tissenbaum, 2013), C. elegans has no known PGC1α homolog by which sirtuins may promote mitochondrial biogenesis (Austin & St-Pierre, 2012). Thus, either mitochondrial mass is unchanged during these treatments in C. elegans or, if changed, occurs after longer duration treatment then the 24 hour duration studied here. Regardless, both of these drug treatments appear to sufficiently increase total NADH oxidation capacity sufficient to maintain cellular homeostasis.

3.6 Integrating multi-dimensional experimental analyses to quantify overall efficacy of drug treatments in a nematode mitochondrial disease model

To reduce the complexity of interpreting the relative positive and negative effects of each drug treatment on the overall health of gas-1(fc21) mutant worms, results from each assay were scored and reduced into a 5-dimensional visual scale, as shown in Figure 7. Relative to wild-type, gas-1(fc21) mutant worms have reductions in lifespan (Row 1). In regard to mitochondrial content and RC function, gas-1(fc21) worms have reduced mitochondrial number and mitochondrial membrane potential, with increased OXPHOS pathway expression (Row 2), presumably in attempted compensation for their impaired mitochondrial function. In gas-1(fc21) animals treated with any of the sirtuin/PPAR modulating drugs, their compensatory increase in OXPHOS transcription is less. Although none of these treatments restore mitochondrial number by 24 hours, a modest benefit at the level of mitochondrial membrane potential that depends on RC function is observed when animals are treated with resveratrol, rosiglitazone, or fenofibrate. NA treatment is not sufficient to acutely restore mitochondrial membrane potential, as this may require signaling input from other pathways (see Figure 8). NAD+ and NADH availability (Row 3) are most effectively restored by Resveratrol treatment, an effect likely mediated at the level of increased OXPHOS capacity and energy availability. Resveratrol also near completely restored BCAA concentrations in gas-1(fc21) mutants to that of wild-type animals (Row 4), with concordant normalization of BCAA metabolic pathway transcriptional profiles as well. In contrast, while NA more effectively restores BCAA concentrations likely by directly impacting flux through the NAD+ dependent BCAA degradation pathway, this is not likely via a transcriptional response as BCAA metabolism pathway expression in response to NAD+ treatment is not highly distinguishable from that of untreated gas-1(fc31). Pathways necessary to maintain DNA integrity (nucleotide excision repair) are substantially down-regulated in gas-1(fc21) mutants despite their having an increased oxidant burden that likely leads to accumulation of oxidative damage, where all sirtuin/PPAR modifying treatments restore this capacity. An improvement in overall RC activity with resveratrol treatment may also be supported by its inducing increased oxidant production with resultant increase in overall mitochondrial oxidant burden (Row 5); although it is possible this finding is reflective of reduced oxidant scavenging capacity, that conclusion seems counterintuitive given resveratrol’s purported anti-oxidant effects (Yun et al, 2014) In summary, this approach demonstrates how results of multidimensional experimental analyses can be integrated to quantify overall drug treatment efficacy in the setting of mitochondrial disease.

Figure 8. Overall model integrating major cellular and biochemical effects of mitochondrial complex I dysfunction and targeted PPAR/sirtuin signaling therapies.

The effect of the gas-1(fc21) mutation on complex I function is indicated by the red ‘X’. Arrows convey the direction of signaling or metabolic pathways under physiologic conditions (black), with complex I dysfunction (red), nicotinic acid treatment (green), resveratrol treatment (orange), rosiglitazone treatment (purple) or fenofibrate treatment (light blue). ψmt = mitochondrial membrane potential; FADH2 = flavin adenine dinucleotide, reduced; TCA = tricarboxylic acid cycle; NADH/NAD+ = nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced/oxidized); e− = electron; O2 = oxygen; ROS = reactive oxygen species; FAO = fatty acid oxidation; NA = nicotinic acid; Resv = resveratrol; Rosi = rosiglitazone; Feno = fenofibrate; NRF = nuclear factor related factor. Question marks convey potential mechanisms that were not directly tested in the current study, including alternate binding partners for rosiglitazone and fenofibrate, and the possible dose-dependent effects of resveratrol on AMPK activity.

3.7 Biological relevance

We demonstrate that CI deficient gas-1(fc21) worms have total cellular NADH and NAD+ deficiencies, which can be effectively therapeutically targeted either directly via NA supplementation, or indirectly via sirtuin activation with resveratrol, to significantly extend animal lifespan in the setting of primary RC deficiency. Both NA and resveratrol therapies also largely normalize the most characteristic transcriptome and amino acid alterations in gas-1(fc21) mutant worms. However, both drug treatments likely exert other pleiotropic downstream effects on additional important dimensions of cellular metabolism, as was demonstrated here by their divergent acute effects on two mitochondria-specific physiologic parameters, namely oxidant burden and membrane potential. Direct PPAR agonists, rosiglitazone and fenofibrate, produced little to modest lifespan and/or physiologic benefits in the genetic-based gas-1(fc21) RC CI mutant worms, with more variability seen with rosiglitazone depending on the stage at which treatment was begun and typically less pronounced effect than seen with either NA or resveratrol treatment. We observed these effects consistently in replicate experiments despite the evident fragility and variability of the mutant nematodes in their response to stress. Indeed, the DMSO buffer necessary for resveratrol, rosiglitazone, and fenofibrate treatments itself may have some detrimental effects on the mitochondrial oxidant burden (Wu et al, 2013), transcriptome, and lifespan studies of C. elegans (Frankowski et al, 2013), highlighting the importance of including buffer-matched control groups as was consistently performed throughout this study. Interestingly, our transcriptome analyses suggest that this may be mediated by the effect of DMSO on worm cuticle integrity regardless of strain (see Supplementary File 2), and be an exacerbating factor in the NAD+ metabolite alterations of the inherently fragile gas-1(fc21) mutant worms (Figure 6b).

All of the drugs studied here, with the exception of resveratrol, are currently in clinical use for treatment of diabetes mellitus and/or dyslipidemia, with acceptable safety profiles. That these sirtuin and PPAR signaling pathway modifying drugs also exert effects in C. elegans demonstrates the marked extent of the shared transcriptional and post-translational modulation of insulin signaling and the closely related nutrient sensing signaling network with humans (Zhang et al, 2013). Specifically, in silico analysis demonstrates the high conservation in C. elegans of the insulin signaling pathway (56% to 94% protein similarity by length determined by BLAST at www.wormbase.org and NCBI Homologene) from insulin through FOXO1 forkhead transcription factor signaling, as well as multiple transcription factors and interacting signaling pathways (45% to 97% protein similarity) that directly modulate its function (DiMauro & Hirano, 2005; Dowell et al, 2003; Inoue et al, 2005; Mukhopadhyay et al, 2006; Murphy et al, 2003; Neumann-Haefelin et al, 2008; Tullet et al, 2008; Wang & Tissenbaum, 2006; Zhang et al, 2008). Indeed, sir2.1 (Wood et al, 2004) and daf-16 show 94.2% and 59.3% similarity to human SIRT1 and FOXO1, respectively. A reciprocal antagonist interaction of PPAR and insulin signaling is rooted in the initial identification by yeast two-hybrid screen of FOXO1 as a PPAR-interacting protein (Dowell et al, 2003; Knutti et al, 2000). Although no definitive PPAR homolog in C. elegans is known, it has a large number of nuclear hormone receptor (‘nhr’) genes with at least modest homology to PPARγ. Specifically, one study suggested that the effect of fibrates depended on intact nuclear hormone receptor (nhr-49) (Brandstadt et al, 2013). Further, our treatment of nematodes with fenofibrate resulted in dramatic decrease in worm fat content, a phenomenon predicted to result from its PPAR agonist activity. In addition, some non-PPAR targets of the thiazolidenediones may exist. For example, proteomics studies have shown that the glitazone core of rosiglitazone has affinity for numerous mitochondrial dehydrogenases (including Acyl-coA dehydrogenase, malate dehydrogenase, lactate dehydrogenase, glycealdehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase) and a cytosolic dehydrogenase (malate dehydrogenase) (Hoffmann et al, 2012). One or more of these interactions may well underlie some of the observed effects in gas-1(fc21) nematodes upon fenofibrate treatment.

Overall, our data demonstrate that altered metabolic regulation through key components of the integrated nutrient sensing signaling network are critical to mediate longevity and physiologic effects caused by primary mitochondrial RC dysfunction in gas-1(fc21) worms (see Figure 8, Overall Model). Specifically, they highlight that the global cellular response to respiratory chain dysfunction is mediated by key intersecting signaling pathways involving sirtuins, PPAR, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and forkhead (FOXO1) transcription factor signaling (Greer et al, 2009; Price et al, 2012). As depicted in Figure 8, impaired complex I function in gas-1(fc21) mutant worms reduces formation of NAD+ from NADH, and leads to less flux through the electron transport system (ETS). Decreased ETS flux results in reduced mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψmt), red arrows. In the setting of decreased complex I function, electron(s) that do not participate in electron transfer contribute to ROS generation, increasing ROS burden as shown. Increased ROS burden has a number of known consequences that increases NAD+ consumption, including, for example, increased PARP response to nuclear DNA damage (Bai et al, 2011). NAD+ salvage is also an ATP-requiring process that is also may be impaired in the setting of energy deficiency caused by complex I impairment (not shown). Increased NAD+ consumption and decreased NAD+ salvage leads to decreases in both NADH and NAD+ as shown throughout Figure 8, though our HPLC quantitation studies suggest that NAD+ is disproportionately affected in the setting of complex I dysfunction. Altered redox balance also affects the metabolism of branched chain amino acids, BCAAs as shown. As we have previously reported (Falk et al, 2008), the α-ketoacid (αKIC) is less readily oxidized in the setting of relative NADH accumulation, which leads to ineffective BCAA degradation by branched-chain amino transferases. Regeneration of α-ketoglutarate (αKG) from glutamate should be favored in the setting of redox imbalance, but this is not sufficient to restore flux through the BCAA degradative pathway, and the net effect is accumulation of the parent BCAA.

Drug effects in this overall model of mitochondrial complex I deficiency are also depicted in Figure 8. Nicotinic acid, a synthetic precursor to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, restores NADH/NAD+, and thereby reduces ROS burden and restores BCAA catabolic capacity, as well as likely PARP activity and NAD+ salvage. Increased NAD+ availability may also increase sirtuin activity. Resveratrol seems to additionally restore OXPHOS capacity and flux through the electron transport system, resulting in a net increase in ROS burden, along with improved NADH/NAD+ levels, perhaps also by virtue of better energy availability for NAD+ salvage (Bai et al, 2011). Activation of global FOXO1-mediated stress responses may also play a role (Yun et al, 2014). Alternatively, resveratrol may act on sirtuins and PGC1α indirectly via AMPK activation (Figure 8) (Price et al, 2012), although it is possible this is a dose-dependent effect of resveratrol and was not explicitly evaluated here. PPAR modulation with rosiglitazone and fenofibrate may additionally restore energy availability by mobilizing fatty acids for oxidation, generating FADH2 that can be used by respiratory chain complex II (distal to the defective complex I) and/or acetyl CoA for TCA cycle anapleurosis. In addition, as noted previously, rosiglitazone and fenofibrate bind to multiple mitochondrial and cytoplasmic dehydrogenases (Figure 8) (Hoffmann et al, 2012), which could thereby alter redox balance, although we did not observe the same magnitude of redox-related decrease in BCAA levels with rosiglitazone and fenofibrate as were seen with NA

Taken together, our findings suggest that NAD+ availability and related signaling effects make a significant contribution to the short lifespan of CI deficient gas-1(fc21) animals. Identification of an absolute cellular deficiency of these essential metabolites in gas-1(fc21) mutants also has translational relevance, as we have recently demonstrated the same phenomena occurs at the cellular level in a human fibroblast line derived from a Leigh disease patient whose primary mitochondrial CI disease results from an m.11778A>G mutation in the ND4 subunit of CI (Zhang et al, 2013). Recognition of total NADH and NAD+ deficiency occurring in different models of primary RC disease is significant because while cellular NAD+ pools are highly compartmentalized (nuclear, cytoplasmic, mitochondrial), NAD+ transporters allow communication between cellular compartments (Todisco et al, 2006) such that mitochondrial CI is clearly a major contributor to overall cellular NAD+ metabolite balance. Similar to our observations in C. elegans CI deficient worms, treating CI deficient patient cells with NA, as a direct NAD+ precursor, rescued their total cellular NADH deficiency and restored their NADH/NAD+ redox balance (Zhang et al, 2013). Furthermore, recent investigations have shown benefits of targeted NAD+-repletion and NAD+-sparing strategies in a mouse model of cytochrome c oxidase deficiency (Cerutti et al, 2014), and nicotinamide riboside has also been used successfully to improve health in a rodent model of mitochondrial myopathy (Khan et al, 2014).

We also show here that resveratrol, a known SIRT1 activator, can restore both NAD+ and NADH metabolite concentrations in CI deficient worms. Similarly, resveratrol supplementation in the presence of intact Sirt1 has been previously found to increase skeletal muscle NAD+ levels in mice (Price et al, 2012). As resveratrol is not a direct precursor for NAD+, its effects could reflect NAD+ salvage rather than increased de novo biosynthesis (Houtkooper et al, 2010; Pittelli et al, 2010) (Figure 8). While NA or resveratrol treatment may thus directly or indirectly restore compromised redox balance in gas-1(fc21) mutants (Falk et al, 2008), neither treatment appeared to restore their low glutamate concentrations; this may potentially reflect concurrent changes in the RC mutant worm tricarboxylic acid cycle flux related to their increased glyoxylate shunt activity and ability to reduce fumarate (Rea et al, 2007). However, repletion of these essential NAD+ metabolite levels was associated with broader biochemical benefit, including normalization of secondary BCAA elevations and reduction of serine and tyrosine levels in the CI deficient gas-1(fc21) worms. Overall, we show that ready interpretation of multi-dimensional experimental analyses can be facilitated by reducing each experimental series to a visual scale that depicts the relative positive and negative effects of each drug on key endpoints, and thereby, the overall health of gas-1(fc21) mutant worms (Figure 7).

Despite some mechanistic differences in their treatment effects, NA and resveratrol supplementation may ultimately have convergent effects on central survival signals that mediate cellular response to primary RC dysfunction (Zhang et al, 2013). Increased NAD+ availability may lead to Sirt1-mediated activation of pro-survival targets like PGC1α (in mammalian cells) and FOXO (in both mammalian cells and worms) (Figure 8). Alternatively these same downstream effects may be directly induced by resveratrol in an NAD+-independent fashion (Hubbard et al, 2013), such as by AMPK activation (Um et al, 2010), inhibition of cAMP phosphodiesterases (Park et al, 2012), or SIRT1-mediated attenuation of pro-apoptotic PARP signaling that is increased in the setting of high oxidative stress (Chung et al, 2010).

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Nicotinic acid and resveratrol rescue short lifespan of gas1(fc21) C. elegans worms

Sirtuin and PPAR modifiers reverse transcriptome hallmarks of complex I deficiency

Resveratrol restores deficient NAD+ and NADH and improves mito membrane potential

Nicotinic acid normalizes deficient NADH and elevated branched chain amino acids

Available drugs for other disorders hold promise for treating mitochondrial disease

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Shana McCormack, Email: mccormacks1@email.chop.edu.

Erzsebet Polyak, Email: polyake@email.chop.edu.

Julian Ostrovsky, Email: ostrovskyj@email.chop.edu.

Stephen D. Dingley, Email: Stephen.Dingley@gmail.com.

Meera Rao, Email: meerao@gmail.com.

Young Joon Kwon, Email: kwonfred@gmail.com.

Rui Xiao, Email: rxiao@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Zhe Zhang, Email: zhangz@email.chop.edu.

Eiko Nakamaru-Ogiso, Email: eikoo@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Marni J. Falk, Email: falkm@email.chop.edu.

References

- Ahmadian M, Suh JM, Hah N, Liddle C, Atkins AR, Downes M, Evans RM. PPARgamma signaling and metabolism: the good, the bad and the future. Nature medicine. 2013;19:557–566. doi: 10.1038/nm.3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin S, St-Pierre J. PGC1alpha and mitochondrial metabolism--emerging concepts and relevance in ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. Journal of cell science. 2012;125:4963–4971. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai P, Canto C, Oudart H, Brunyanszki A, Cen Y, Thomas C, Yamamoto H, Huber A, Kiss B, Houtkooper RH, Schoonjans K, Schreiber V, Sauve AA, Menissier-de Murcia J, Auwerx J. PARP-1 inhibition increases mitochondrial metabolism through SIRT1 activation. Cell metabolism. 2011;13:461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Arous J, Laffont S, Chatenay D. Molecular and sensory basis of a food related two-state behavior in C. elegans. PloS one. 2009;4:e7584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitterman KJ, Anderson RM, Cohen HY, Latorre-Esteves M, Sinclair DA. Inhibition of silencing and accelerated aging by nicotinamide, a putative negative regulator of yeast sir2 and human SIRT1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:45099–45107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandstadt S, Schmeisser K, Zarse K, Ristow M. Lipid-lowering fibrates extend C. elegans lifespan in a NHR-49/PPARalpha-dependent manner. Aging. 2013;5:270–275. doi: 10.18632/aging.100548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitling R, Armengaud P, Amtmann A, Herzyk P. Rank products: a simple, yet powerful, new method to detect differentially regulated genes in replicated microarray experiments. FEBS letters. 2004;573:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canto C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, Milne JC, Elliott PJ, Puigserver P, Auwerx J. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458:1056–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti R, Pirinen E, Lamperti C, Marchet S, Sauve AA, Li W, Leoni V, Schon EA, Dantzer F, Auwerx J, Viscomi C, Zeviani M. NAD(+)-Dependent Activation of Sirt1 Corrects the Phenotype in a Mouse Model of Mitochondrial Disease. Cell metabolism. 2014;19:1042–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S, Yao H, Caito S, Hwang JW, Arunachalam G, Rahman I. Regulation of SIRT1 in cellular functions: role of polyphenols. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2010;501:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desquiret-Dumas V, Gueguen N, Leman G, Baron S, Nivet-Antoine V, Chupin S, Chevrollier A, Vessieres E, Ayer A, Ferre M, Bonneau D, Henrion D, Reynier P, Procaccio V. Resveratrol induces a mitochondrial complex I-dependent increase in NADH oxidation responsible for sirtuin activation in liver cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:36662–36675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.466490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMauro S, Hirano M. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathies: an update. Neuromuscul Disord. 2005;15:276–286. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingley S, Chapman KA, Falk MJ. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of mitochondrial content, membrane potential, and matrix oxidant burden in human lymphoblastoid cell lines. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;837:231–239. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-504-6_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingley S, Polyak E, Lightfoot R, Ostrovsky J, Rao M, Greco T, Ischiropoulos H, Falk MJ. Mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction variably increases oxidant stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mitochondrion. 2010;10:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell P, Otto TC, Adi S, Lane MD. Convergence of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and Foxo1 signaling pathways. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:45485–45491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]