Abstract

Dopamine neurons located in the midbrain play a role in motivation that regulates approach behavior (approach motivation). In addition, activation and inactivation of dopamine neurons regulate mood and induce reward and aversion, respectively. Accumulating evidence suggests that such motivational role of dopamine neurons is not limited to those located in the ventral tegmental area, but also in the substantia nigra. The present paper reviews previous rodent work concerning dopamine’s role in approach motivation and the connectivity of dopamine neurons, and proposes two working models: One concerns the relationship between extracellular dopamine concentration and approach motivation. High, moderate and low concentrations of extracellular dopamine induce euphoric, seeking and aversive states, respectively. The other concerns circuit loops involving the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, thalamus, epithalamus, and midbrain through which dopaminergic activity alters approach motivation. These models should help to generate hypothesis-driven research and provide insights for understanding altered states associated with drugs of abuse and affective disorders.

Keywords: Depression, mania, euphoria, dorsal striatum, global pallidus, and mediodorsal thalamic nucleus

1. Introduction

Increased activity of brain dopamine (DA) induces euphoria and approach motivation, while decreased DA activity induces dysphoria and withdrawal-like conditions [1–4]. This view of DA’s functions has been derived, in part, from research on drugs of abuse, and thus DA is thought to play a key role in reward action of abused drugs [5–7]. In addition, DAergic dysfunction has been implicated in affective disorders [8–14].

The roles of DA activity in motivation and reward are generally attributed to the mesolimbic DA system, consisting of DA neurons localized in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) projecting to the ventral striatum (VStr) [1, 2] (But see [15]). However, recent optogenetic studies utilizing transgenic mice has produced strong evidence suggesting that reward is readily induced not only by stimulation of the mesolimbic DA system, but also the nigrostriatal DA system [16, 17], consisting of DA neurons localized in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) projecting to the dorsal striatum (DStr, also known as the neostriatum or caudate-putamen). These findings suggest an underappreciated role of the nigrostriatal DA system and thereby the basal ganglia (BG) in motivational functions. The view that the functional roles of VTA and SNc DA neurons are not dichotomous is consistent with a recent observation that essentially the same brain regions provide afferent inputs to DA neurons of both the VTA and SNc, although their input degrees from each region differ between them [18].

Human research has emphasized the role of the nigrostriatal DA system and the BG in movement regulation, whose dysfunction leads to disorders such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s. In addition, evidence is accumulating for the involvement of the nigrostriatal DA system and BG in motivation, whose dysfunction may lead to depressed mood, apathy and anhedonia [19, 20]. For example, post-stroke damage in the DStr, pallidum or BG-associated thalamo-cortical regions often result in depression and related symptoms [21–26]. Deep brain stimulation at the subthalamic nucleus of Parkinson’s patients can produce side effects including improved mood, hypomanic state or apathy [27–30]. Imaging studies revealed that depression is correlated with smaller volumes of the BG and related brain regions [31, 32]. Moreover, activation of the DStr is correlated with drug craving [33, 34], drug euphoria [35] and happiness [36, 37]. Importantly, electrical stimulation administered at the DStr can be pleasing and is self-administered in humans [38, 39].

We will discuss a model describing the relationship between DA concentration of the striatum and approach motivation, and then propose a model describing circuit loops involving both VTA-and SNc-striatal DA systems and associated BG-thalamo-cortical and BG-habenulo-mesencephalic structures involved in regulating motivation. We hope to provide insights for understanding neural mechanisms underlying drug euphoria, craving and affective disorders.

2. DAergic regulation of mood and approach motivation

2.1. Approach motivation, reward and reinforcement

Before discussing motivational state in relation to these structures, it is important to clearly define the terms: approach motivation, reward and reinforcement. Particularly, DA’s role in reward has been controversial. Disagreements may have arisen from differences in the focus of research (e.g., drugs vs. food), definition, or assumptions. The present paper does not make the following assumptions: One, DA only has a single effect on behavior; and two, reward is a homogeneous phenomenon. Therefore, DA can be involved in reward even if it does not alter food consumption or orofacial reaction to food.

The fundamental property that distinguishes animals from plants is that animals have the ability to approach life-sustaining things or events (i.e., rewards) and withdraw from life-threatening things or events. In the present paper, the term approach behavior is used to represent a broad set of responses, such as exploration and reward-reinforced instrumental responding. Likewise, withdrawal behavior includes responses such as freezing, escape, and their associated internal states. We assume that approach and withdrawal processes are mutually inhibitory. Furthermore, engaging in approach and withdrawal behaviors is accompanied by positive and negative mood states, respectively, and are positively and negatively reinforcing [3, 40].

We define reward, using behavioral terms, in two ways: First, rewards are external things or events that produce and reinforce approach behavior. In addition, reward is an induced internal state that produces and reinforces approach behavior [3, 4]. While positive reinforcement involves learning about the relationship between environment and behavior in the interest of procuring rewards [41], reward concerns not only reinforcement, but also the aroused, motivated state that drives approach behavior. Biologically important things or events trigger not only reinforcement, but also arousal that increases attention to and interaction with the environment [42–44]. Thus, reward refers to internal state reflecting both reinforcement and arousal concerning approach behavior.

2.2. Motivation and the VTA-VStr DA system: pharmacological studies

Evidence for the role of DA in reward and approach motivation is strongly supported by research on drugs of abuse [1, 2, 4–7]. Psychostimulant drugs such as cocaine block the DA uptake system, and other psychostimulants like amphetamines stimulate DA release and block the DA uptake system. Thus, administration of these drugs markedly increases extracellular DA concentrations in the striatum, especially the VStr [45]. These properties are critical for their rewarding effects, as systemic injections of DA receptor antagonists readily modulate self-administration. Low doses of DA receptor antagonists increase intravenous self-administration of cocaine or amphetamine, probably due to compensatory responding for drugs’ arousing effects discounted by the antagonists. On the other hand, high doses of DA receptor antagonists diminish such self-administration behavior [46, 47]. Selective reduction of DA transmission with intra-VStr injections of DA receptor antagonists or 6-OH-DA lesions of VStr DA terminals also reduces or diminishes self-administration of these drugs, depending on the dose [48–52]. Interestingly, intracranial self-administration studies further indicate that of psychostimulant drugs preferentially act on the medial, rather than the lateral, part of the VTA-VStr DA system with respect to reward [2, 53]. Psychostimulant drugs or DA receptor agonists are preferentially self-administered into the medial accumbens shell and medial olfactory tubercle over the core, lateral shell or lateral olfactory tubercle [54–59]. Consistently, systemic administration of psychostimulant drugs such as cocaine or amphetamine increases extracellular DA concentration in the medial VStr more than the lateral VStr [60, 61]. Because the medial and lateral VStr largely receive DA projections from the posteromedial and anterolateral parts of the VTA, respectively [2], these studies suggest that psychostimulant drugs preferentially activate the medial part of the VTA-VStr DA system for reward. In addition, increased VStr DA activity augments approach behavioral processes [1]. For example, microinjections of amphetamine into the VStr increase approach responding rewarded by conditioned stimuli [62] or unconditioned visual stimuli [63].

Conversely, decreased DA transmission, particularly in the VStr, induces aversion and disrupts approach behavior [1]. Anecdotal reports indicate that administration of neuroleptics, which block D2 receptors, produces aversion in psychiatric patients. Consistently, microinjections of the D1 receptor antagonist SCH 23390 into the VStr induce conditioned place aversion [64]. Similarly, high doses of the D2 receptor agonist quinpirole injected into the VTA, stimulate DA autoreceptors, decrease VTA-VStr DA activity, and induce aversion [65]. Moreover, low doses of quinpirole injected into the VTA block conditioned place preference induced by food even though they do not decrease food intake [65]. Furthermore, the DA receptor antagonist flupentixol injected into the VStr decreases approach responding rewarded by sucrose even though the same injection does not reduce sucrose intake [66]. Intra-VStr DA antagonists do not disrupt movement processes per se, but the integration of environmental stimuli for approach behavior [67, 68].

The observation that severe reduction of DA activity not only disrupts approach behavior, but also induces aversion raises a question over whether reduction of brain DA activity merely reduces approach motivation or produces the opposite of approach motivation, namely withdrawal motivation. Reduced DA activity does not produce notable stress, anxiety or fear responses. Consistently, Fiorillo showed that the presentation of cues signaling aversive stimuli plus reward does not readily reduce DA neuron activity compared to the presentation of reward cues alone; thus, DA neurons activity does not seem to encode aversiveness [69]. The role of the DA system in mood regulation may be characterized by the tugging hypothesis, in which mood state is regulated by multiple systems tugging each other in the direction of either positive or negative states [4]. The activation of the DA system pulls mood state in a positive direction, while the activation of other systems pulls it in negative directions. Inhibition of the DA system results in the imbalance of mood homeostasis in a negative direction, thereby aversion.

2.3. Motivation and DA: optogenetic studies

Optogenetic studies confirmed the pharmacological findings that the VTA-VStr DA system is important in mood regulation. The rewarding effects of VTA DA neurons are shown with conditioned place-preference or self-stimulation procedures involving viral delivery of the opsin channelrhodopsin2 into the VTA of TH-Cre or DAT-Cre rodents [16, 70–73]. Moreover, stimulation of DA neurons at terminals in the nucleus accumbens is rewarding [74]. In addition, inhibition of VTA DA neurons with photostimulation involving halorhodopsin induces aversion as shown by place avoidance [16].

Previously, electrical stimulation studies have suggested that SNc DA neurons are involved in reward [15]. In particular, rats learn instrumental responding when rewarded with electrical stimulation in the vicinity of the SNc [75–77]. However, electrical stimulation activates neurons whose cell bodies are not necessarily located in the vicinity of the electrode tip through fibers of passage [78–80]; therefore, it is difficult to interpret the data. Optogenetic studies verified that excitatory photostimulation of SNc DA neurons is not only rewarding, but can be as rewarding as that of VTA DA neurons [16, 17]. While recent studies indicate that activation of sub-populations of VTA DA neurons are associated with aversive functions [81–83], they may not project to the striatum. In any case, the net effect of activating VTA or SNc DA neurons is rewarding. In addition, optogenetic inhibition of SNc DA neurons at the level of their cell bodies or DStr terminals induces aversion, effects comparable to that of VTA DA neurons [16]. Therefore, these new studies indicate that SNc DA neurons are involved in reward and aversion much like VTA-VStr DA neurons.

Motivational state altered by manipulations of SNc DA neurons is most likely mediated by the DStr, as the vast majority of SNc DA neurons projects to the DStr [84–86]. Moreover, as discussed above, inhibition of DA release in the DStr with an optogenetic procedure induces aversion [16], and stimulation of DStr neurons are rewarding [87–89]. It is unclear at this time whether there is a difference in affective processes within the DStr, as it is a large structure with major topographic differences in inputs and outputs. First of all, functional anatomical data suggest that the medial part of the DStr is more important than the lateral DStr in affective functions, because the medial, but not lateral, DStr receives inputs from the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, which are strongly implicated in affective functions [32, 90–92]. However, the lateral DStr may still be involved in affective processes, because electrical stimulation of the lateral DStr induces reward as shown by self-stimulation behavior [87, 88]. In summary, optogenetic studies have found that activation and inactivation of the SNc-DStr DA system induce reward and aversion, respectively. The DStr is most likely the primary structure that mediates rewarding effects of SNc DA-neuron stimulation, though it is unclear whether the whole DStr is involved in reward and aversion.

In passing, it should be noted that pharmacological research has consistently shown that psychostimulant drugs and other related drugs preferentially alter the activity of the medial VStr-VTA DA system for reward and motivation ([2]; see section 2.3). In light of recent optogenetic findings, it is important to investigate why such drugs alter the medial VTA-VStr DA system more effectively than the lateral VTA-VStr or SNc-DStr DA systems for motivational functions.

3. Extracellular DA concentration alters approach motivation

While phasic activity of DA neurons and thereby phasic DA release has been implicated in reinforcement learning [93–96], both phasic and tonic DA activity appear to be involved in motivational state. We will first review research on intravenous drug self-administration and then recent findings in optogenetic research.

3.1. Intravenous self-administration of psychostimulant drugs

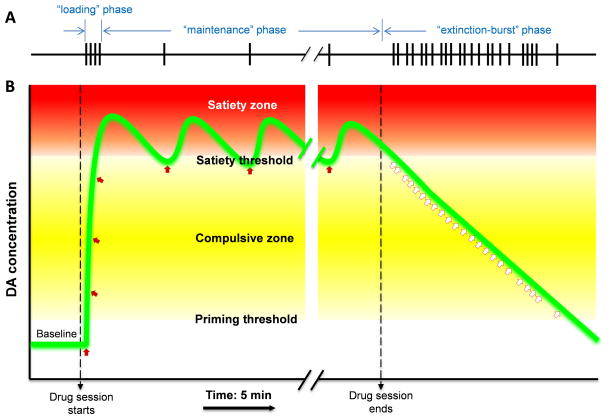

The unit dose of drugs such as cocaine and amphetamine will reliably predict the rate of self-administration behavior. High unit doses of such drugs produce low response rates, while low unit doses produce high response rates. That is, animals withhold responding until blood concentration of the drug falls below a certain concentration. Thus, intravenous self-administration rates for drugs are remarkably constant and depend on how fast drugs are eliminated from the system [97–99]. High unit doses do not appear to induce aversion or discomfort that stops self-administration, because animals acquire self-administration with high unit doses faster and more reliably than low unit doses [100]. Such observation gave rise to the concepts of “drug satiety” [46, 101] and “compulsive zone” [102]. Drug self-administration is suppressed when drug concentration in the system remains high, a phase referred to as the satiety zone (Fig. 1). Below the satiety threshold is the compulsive zone, where animals exhibit compulsive conditioned responding. The lower limit of the compulsive zone is the “priming threshold” below which drug concentration will not maintain conditioned responding, or reinstate extinguished responding.

Figure 1. Schematic models depicting the relationship between VStr DA concentration levels and drug self-administration behavior.

A. Event records depicting time points of lever-press events over the course of a self-administration session.

B. Extracellular DA concentration regulates conditioned responding for drug reward (e.g., cocaine). Well-trained animals exhibit an approach response as soon as a drug session starts, and make several responses relatively quickly at the beginning of the session, so-called “loading” phase, followed by slow, steady responding (the “maintenance” phase). When the drug session is suddenly terminated, animals exhibit conditioned responses relatively frequently for the next few minutes until DA concentration falls below the priming threshold. Filled red arrows indicate when conditioned approach responses are rewarded by intravenous drug injections, while empty arrows indicate when conditioned responses are not rewarded.

Response rates predicted by the drug concentration depend on drugs’ property to increase DA concentration. That is, drug concentration in the system modulates extracellular DA concentration, which in turn determines response rates. Microdialysis studies found that response rates for cocaine or amphetamine increase from almost zero to very high when extracellular DA concentration in the VStr falls below a certain level, i.e., the satiety threshold, whose concentrations are several-fold greater than baseline DA concentrations [101, 103]. As discussed above, moderate doses via systemic injections or, more selectively, intra-VStr injections of DA receptor antagonists shorten inter-reinforcement intervals for drug self-administration [46–49]. Importantly, perfusion of D1 and D2 DA receptor agonists into the VStr prolongs inter-reinforcement intervals for cocaine self-administration [104]. Since this effect was found with infusions into the core, but not the medial shell, there may be a sensitivity difference among VStr regions in controlling response rates. In summary, these data suggest that high extracellular concentration of VStr DA inhibits conditioned reward-seeking, while moderately high concentration energizes conditioned reward-seeking.

It should be noted that the prolonged high DA concentration that accompanies the satiety zone (Fig. 1) may be unique to abused drugs. Once in the system, abused drugs remain in the system for several minutes to hours, altering the synaptic activity of their targets. Without the drugs’ property of remaining in the system, DA concentration would not be maintained at high levels for a prolonged period of time. For example, when hungry animals unexpectedly find food in a novel environment or cues signaling the availability of food, striatal DA concentration tonically increases to no more than 200% of baseline, as detected by microdialysis [105, 106]. Phasic increases triggered by food-related stimuli are thought to be greater, however it is hard to measure phasic increases in terms of percentage, because phasic DA is detected by voltammetry procedures, which typically do not specify absolute DA concentration, but relative change from a baseline. Similarly, sexual stimuli may not tonically increase DA concentrations much more than 200% [107, 108]. Thus, natural stimuli do not appear to produce and maintain the 1,000%-above-baseline DA concentrations like psychostimulant drugs readily do. In addition, phasic and tonic increases of DA concentration induced by food will dissipate over repeated sessions even if animals are hungry, given that the repeated sessions occur in a predictable manner, whereas drug-induced increases in DA concentration do not depend on the predictability and are replicated over repeated sessions [1]. These differences in DA activity between psychostimulant drugs and natural rewards may have contributed to disagreements regarding the role of DA in reward between investigators of drugs and natural rewards.

3.2. Optogenetic excitation of DA neurons, reward and self-stimulation

While the drug research presented so far suggests that tonic activity of DA transmission is necessary for reward, a recent optogenetic study suggests that phasic excitation of DA neurons is sufficient for reward. Tsai et al. [70] compared the effects of photostimulation consisting of 25 pulses delivered at 1 Hz, referred to as “tonic” stimulation, with those of 25-pulse stimulation at 50 Hz, referred to as “phasic” stimulation, and found that 50-Hz stimulation produces conditioned place-preference, whereas 1-Hz stimulation does not. Although it is not realistic to expect that DA neurons fire 25 times continuously at 50Hz in any natural setting, the take-home-message of the study is that phasic surge, without lasting elevation of DA concentration, is sufficient for inducing reward. However, it is misleading to conclude that phasic, but not tonic, activity of DA induces reward in light of psychostimulant drugs’ action as reviewed above. Rather than the notion of phasic vs. tonic activity, the key notion is extracellular DA concentration (Fig. 1). That is, the 25-pulse train delivered at 50 Hz elevates DA concentration to a level sufficient for reward, whereas the 25-pulse train at 1 Hz does not, due to the fast action of the DA uptake system [109, 110]. The 50-Hz, but not 1-Hz, train releases DA faster than the uptake system can eliminate it, resulting in a high extracellular DA concentration [111].

Figure 2A describes how DA concentration changes as a function of pulse number and pulse frequency with stimulation parameters used in recent optogenetic self-stimulation studies [16, 72]. A train of 4 light pulses (25 Hz with 10-ms pulse duration) applied at the VTA should increase and decrease VStr DA concentration in a sub-second order [71, 111] (Fig. 2A). These fast changes in DA concentration as a function of photostimulation seem to explain a large part of why mice self-administer excitatory photostimulation to DA neurons. Figure 2B depicts a model describing the relationship between DA concentration and reward-seeking behavior. This model is essentially the same as that for psychostimulant drugs blocking DA uptake system (Fig. 1) with the exception of timescale: Increased DA-concentration caused by pulse-stimulation of VTA DA-neurons decreases rapidly on a sub-second order because of highly competent uptake system in the absence of any DA-uptake blocker. If multiple stimulation pulses are delivered rapidly, they presumably increase DA concentration high enough to alter the motivational state of the responder and reinforce its responding. This model is consistent with fast, compulsive patterns of self-stimulation behavior with DA-neuron photostimulation [16, 72] (Fig. 2C), since photostimulation not only reinforces, but also energizes responding. It is also consistent with the following observations: rapid extinction with DA-neuron photostimulation (Fig. 2D) and poor maintenance of self-stimulation with an interval of one second or longer (Fig. 2E). This is because phasically released DA is removed rapidly from extracellular space and its concentration decreases to the level below the priming threshold, at which the motivational effect of photostimulation diminishes. Although a train of 8 or 16 pulses increases VStr DA concentration much more than a 4-pulse train (Fig. 2A), self-stimulation rates between the trains do not differ significantly with a continuous reinforcement procedure (Fig. 2E). However, when animals have to wait one second for the next reinforcement, the 16- or 8-pulse train sustains self-stimulation behavior better than the 4-pulse train, and the 16 pulses better than 8 pulses, presumably because the 16- and 8-pulse trains elicit a greater concentration of DA, prolonging the compulsive zone, thereby producing persistent conditioned responding [72]. It should be noted that these properties of DA concentration are short-lasting; other longer-lasting mechanisms (i.e., reinforcement) involving synaptic or morphological changes also participate in regulation of conditioned responding.

Figure 2. Extracellular DA concentration and approach responding rewarded by stimulation of VTA DA neurons.

A. Changes of VStr DA concentration after photostimulation of VTA DA neurons schematically shown based on previous work [111]. A train of 4 light pulses delivered at 25 Hz rapidly increases DA concentration (a). A train of 8 pulses increases DA concentration more so than 4 pulses (b). However, when an 8-pulse train is delivered at a slower rate of 12.5 Hz, DA concentration does not increase as high as that of the 8-pulse/25-Hz train (c). Extracellular DA is removed as it is released from the cell. Thus, DA concentration depends not only on the amount of neural firing, but also the firing rate.

B. Hypothetical VStr DA concentration levels during self-stimulation behavior rewarded by photostimulation (8-pulse/25-Hz train) of VTA DA neurons. A response on the lever triggers photostimulation of DA neurons, resulting in an increase of striatal DA concentration, reinforcement, and energization of responding. Compared to responding rewarded by IV cocaine administration (Fig. 1B), extracellular DA concentration increases rapidly due to photostimulation, and also decreases rapidly due to the absence of DA uptake blockers.

C. The cumulative responses rewarded with photostimulation (15-pulse/25-Hz train) of VTA DA neurons of a representative mouse. When the cumulative lever-press count reaches 250, the count is reset at 0, and the angle of the cumulative-lever-press line indicates the rate of lever-press. Slashes indicate the time point of photostimulation reinforcement.

D. Rapid decrease in lever-pressing during extinction. When a group of mice trained to self-stimulate with VTA photostimulation (15-pulse/25-Hz train) underwent an extinction phase for the first time, they decreased response rates quickly. The data are mean with s.e.m. *P < 0.0005, value significantly lower than that of block 1or 5.

E. Mean lever-press rates are shown as a function of inter-reinforcement interval and pulse number. Responding was rewarded with 2, 4, 8 or 16-pulse trains of photostimulation with the inter-reinforcement interval of 0, 1, 3 or 10 s. Regardless of pulse numbers, the inter-reinforcement interval of 3 or 10 s diminished self-stimulation, while the 0-s interval (i.e., continuous reinforcement) supported constant self-stimulation behavior. All 0-s interval values were significantly greater than respective 3- or 10-interval values (Ps < 0.001). *P < 0.001, significantly greater than its 3- and 10-s values, but not from its 0-s value; #P < 0.05, significantly greater than its 3-and 10-s values, but lower than its 0-s value; +, ^P < 0.001, not significantly different from its 3- and10-s values, but lower than its 0-s value.

Panels C–E are adopted from our published work [72].

This model can explain the sustained activity of midbrain DA neurons or striatal extracellular DA observed in behavioral experiments involving electrophysiology or voltammetry recordings. Fiorillo et at. [112] found that DA neurons display sustained activity between the presentation of cues predicting rewards and the delivery of rewards. This tonic anticipatory activity depends on the probability of reward delivery. Uncertain reward delivery may prompt a heightened motivational state attempting to increase the probability of gaining rewards. Similarly, Howe et al. [113] found ramping of striatal DA concentration as rats approached a reward on a runway. Our model explains that elevated DA concentration is needed to sustain conditioned responding toward reward; without it, behavior is no longer goal-directed.

In addition, this model incorporates the effects of reduced striatal DA transmission. As noted above, aversion, anhedonia and hypoactivity can be induced by intra-VTA injections of the D2 receptor agonist quinpirole that reduces tonic activity of VTA DA neurons [65], or optogenetic inhibition of VTA or SNc DA neurons [16].

In summary, this model describes the relationship between extracellular striatal DA concentration and the regulation of approach motivation, including reward and aversion. Although we have described the model (Fig. 2B) as explicitly as possible, the obvious next step would be to incorporate these findings into computational models (e.g., [114, 115]).

4. Circuit loops mediating motivational state altered by DA

While neural spiking occurs in the order of milliseconds, motivation is regulated in the order of seconds or longer in healthy individuals and lacks adaptive changes in individuals with affective disorders or state altered by drug administration. The brain must have ways to maintain approach state, which depends on the orchestrated activity of many brain regions, to coherently influence ongoing sensation, perception, decision-making and actions. One such mechanism may be circuit-loop organizations, which help to coordinate the activity of many brain regions. Motivational state altered by DA or the lack of DA may influence large-scale loops involving a number of structures ranging from the lower brainstem to the cortex. Indeed, the VTA-VStr and SNc-DStr DA systems appear to be components of large-scale circuit loops involving the BG, midbrain, thalamic and cortical structures. These loop organizations have been discussed for motor processes and movement disorders [116, 117] as well as motivation and reinforcement [117–120]. The aim of this section is to review the structural connectivity of the BG and associated structures, and to discuss them with respect to DA activity and mood state. We will focus on the medial half of the BG and associated structures, because it is unclear at this time whether the lateral BG, which is most strongly associated with sensory-motor functions, participates in motivation. The proposed model is tentative and meant to be constantly updated with new research.

4.1. Common structural organization between the nucleus accumbens and olfactory tubercle

Let us start with the nucleus accumbens and olfactory tubercle, and discuss the role of the VP in mediating their motivational functions. The nucleus accumbens has been studied extensively as a key target of DA for reward and motivation [1]. However, its downstream circuits are not clearly understood for motivation and reward/aversion. Accumbens neurons project to many structures in the forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain, including the VP, sublenticular extended amygdala, entopeduncular nucleus (EP), lateral preoptic area, lateral hypothalamic area, VTA, SNc, substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr), retrorubal area, pedunculopontine tegmental area, periaqueductal gray and parabrachical area [121–123]. Because of this diverse connectivity, it has been difficult to establish which downstream structures underlie the motivational functions of accumbens DA signals [124]. Importantly, intracranial self-administration studies have found that psychostimulant drugs are self-administered into not only the nucleus accumbens, but also the olfactory tubercle [2, 56, 57]. Moreover, increased DA transmission in the olfactory tubercle augments approach behavior [63]. The olfactory tubercle contains medium-size spiny projection neurons (MSNs) [125], a defining characteristic of the striatum, receives inputs from the VTA, limbic cortices and limbic thalamus, and sends its outputs to the VP [126–129], just like the nucleus accumbens. A key feature of the striatal olfactory tubercle is its exclusive projections to the VP and no other region [129]. Therefore, all the motivational functions of the striatal olfactory tubercle must be mediated through the VP, and therefore, the VP is most likely the key structure that mediates motivational functions of the nucleus accumbens.

4.2. Connectivity and functional organization of the BG and associated structures

The BG historically included the DStr, globus pallidus (GP or also known as external or lateral GP), EP (or also known as internal or medial GP), subthalamic nucleus (STh) and SNr (Fig. 3A). Exact components of the BG differ depending on the investigator and his or her functional focus [116, 117, 130–133]. The present paper defines the BG as the aforementioned structures plus the VStr and VP, because of common connectivity patterns between the VStr and the DStr [126, 127, 134, 135]. That is, like the DStr, the VStr receives cortical inputs and has GABAergic MSNs projecting to a pallidal structure [136], which, in turn, projects to the thalamus and epithalamus [137] (Fig. 3). The difference is that the VStr largely projects to the VP, while the DStr projects to VP’s lateral counterparts, GP/EP/SNr [138], which integrate and relay signals from the DStr to thalamic and epithalamic structures.

Figure 3. Connectivity of the basal ganglia (BG), and functional and topographic organizations.

A. Connectivity of the BG. Abbreviations: ACh, achetylcholine; CM, central medial thalamic nucleus; DStr, dorsal striatum; EP, entopeduncular nucleus; GP, globus pallidus; Glu, glutamate; LHb, lateral habenular nucleus; MD, mediodorsal thalamic nucleus; PV, paraventricular thalamic nulceus; PF, parafascicular thalamic nucleus; RMTg, rostromedial tegmental nucleus; SNc, substantia nigra pars compacta; SNr, substantia nigra pars reticulata; STh, subthalamic nucleus; VA, ventral anterior thalamic nucleus; VL, ventrolateral thalamic nucleus; VM, ventromedial thalamic nucleus; VP, ventral pallidum; VStr, ventral striatum; VTA, ventral tegmental area

B. Schematic drawing of topographic organization of the connectivity. Each region is topographically organized, and topography is maintained throughout the BG-thalamocortical regions.

C. General or natural functions of the BG and related structures. Animals produce voluntary behavior to interact with their immediate environment for approaching rewards and avoiding threats. Such adaptive behavior is thought to be controlled by the parallel circuits of the BG-thalamocortical circuit loops. Medial, central and lateral components of the circuit loops are involved in affective (a), cognitive (b) and sensori-motor (c) processes, respectively. For example, when energy homeostasis begins to be compromised, environmental stimuli invite animals to produce exploratory behavior (a), and any distal stimuli that may be a potential energy source triggers more focused approach behavior (b). Meanwhile, as animals move about the environment, approach movements are coordinated by moment-to-moment inputs of sensory information reflecting environmental dynamics (c).

Over 90% of VStr or DStr neurons are MSNs, which can be largely classified into two types: MSNs that express D1 receptors and contain substance-P and dynorphin, and those express D2 receptors and contain enkephalin. For the DStr, D1-MSNs project to the GP, EP and SNr, while D2-MSNs exclusively project to the GP [139–142]. D2-MSNs projecting to the GP are referred to as “indirect” pathway neurons because the GP projects to other BG structures (i.e., the STh, EP and SNr), rather than out of the BG. However, there is a caveat for this well-established notion of D2-MSN projection as indirect pathway: It only applies to projections targeting at the anterior GP. Because the posterior GP projects out of the BG to various brainstem regions [143], D2-MSNs projecting to the posterior GP are not considered part of the indirect pathway. D1-MSNs projecting to the EP/SNr are known as direct pathway neurons, because EP and SNr neurons send signals out of the BG, to regions such as thalamic nuclei [144–156].

Unlike DStr MSNs, VStr D1- and D2-MSNs do not appear to have segregated patterns of projection, but both project to the same structure, the VP [135]. If VStr MSNs are organized like DStr MSNs, and their organizations are parallel, the VStr’s target VP may be thought of as the undifferentiated medial extension of the GP and EP, and VTA GABA neurons as the un-compartmentalized medial counterpart of SNr GABA neurons. If this view is correct, VP neurons receiving inputs from D1-MSNs should project to thalamic nuclei; and VP neurons receiving D2-MSN afferents should project to the STh and VTA GABAergic neurons. This is a question that remains to be examined.

As alluded to above, VP, EP and SNr neurons project to thalamic nuclei. Their targets include the paraventricular (PV), parafascicular (PF), central medial (CM), the mediodorsal (MD), ventromedial (VM), ventroanterior (VA) and ventrolateral (VL) nuclei [136, 144, 147, 150, 153, 154, 156–159]. Glutamatergic neurons of all of these regions project to cortical regions [160–163], which in turn, project to the striatum, while glutamatergic neurons of the PV, PF and CM additionally project to the striatum [164–166].

In addition to thalamo-cortical routes, the BG also send signals to the lateral habenular nucleus (LHb), whose glutamatergic neurons receive robust inputs from the EP and a lesser extent from the VP [150–153]. While the VP appears to send inhibitory projections to the LHb, the EP sends both excitatory and inhibitory projections to the LHb [167–170]. The LHb, in turn, projects to the midbrain. While the medial part of the LHb sends excitatory projections to VTA GABAergic neurons, which can inhibit VTA DA neurons, the lateral LHb sends excitatory projections to the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg) [171, 172], which contains GABAergic neurons that send inhibitory signals onto VTA and SNc DA neurons [171, 173].

4.3. Functionally parallel and integrative organization of the BG-thalamo-cortical structures

DA neurons of the VTA and SNc massively project, in a topographic manner, to the entire striatum – i.e., the VStr and DStr [2, 84–86, 144], which also receives topographically-organized inputs from the entire cerebral cortex (Fig. 3B) [174–177]. Importantly, the cortico-striatal topography is maintained throughout the BG and thalamic structures; that is, the cortico-BG-thalamo-cortical structures consist of parallel circuits [117, 130, 131, 178, 179]. In addition, cortico-BG-thalamo-cortical parallel circuits are not completely closed, but organized in such a way that circuits split and send information to immediately adjacent parallel-circuits [180]. Although this point is not critically relevant to the model we discuss below, it is important to keep in mind that parallel circuits are not absolute. Circuit-splits appear to occur in striatal neurons projecting to the VTA, SNc and SNr [122, 123, 178, 181, 182]. VStr neurons project to not only the VP, but also the GP and EP [122, 123]. VP neurons project to not only the VTA and thalamic structures, but also the STh and SNr [137, 183]. Thus, information tends to diverge onto immediately lateral, rather than medial, structures.

The cortico-BG-thalamo-cortical circuitry is popularly divided into three functional units: the medial, central and lateral circuits labeled as limbic (or motivational; Fig. 3Ca), associative (or cognitive; Fig. 3Cb) and motor (Fig. 3Cc) functions, respectively [184–186]. Of the cortical regions, the medial (or visceromotor) network of the prefrontal cortex [187, 188] has been implicated strongly in motivational processes as in affective disorders [32, 92]. The medial network largely consists of the prelimbic, infralimbic, dorsal peduncular and medial orbital regions, which are strongly connected with each other and with the medial MD and with the basolateral amygdala. The present paper focuses on the BG linked with the medial network of the prefrontal cortex, circuit loops particularly important in mediating motivation. The medial network not only projects to the VStr, but also to the medial part of the DStr, which also receives inputs from the amygdala [189–201].

It should be noted that the popular functional divisions are useful as a rule-of-thumb description. However, this functional organization implicitly suggests that each of the functional domains is independent from others. The new data that we discussed in section 2.4 suggest that much wider areas of meso-striatal DA systems are involved in reward/aversion processes than previously thought. Therefore, we should not exclude the possibility that brain structures known to be involved in cognitive or motor processes can play a role in motivational processes as well. Having that said, it is unclear to what extent these circuits are involved in motivational processes. Therefore, we emphasize the structures connected with the medial prefrontal network as of primary importance for motivation.

4.4. Consequences of altered DA concentration on D1- and D2-MSNs and the BG

DA is not a driver, but a modulator. That is, DA does not decisively alter the neural activity of MSNs in one way or another [202]. Discussed below is a working model that characterizes the role of DA in MSN activity at the population level – rather than the level of individual MSNs – for regulating motivational state. We first present our hypothesis concerning how DA concentration alters the activity of D1- and D2-MSNs and thalamic neurons for motivation. This hypothesis forms the foundation for our discussion on circuit loops.

Increases in striatal DA concentration result in a net increase in the firing of D1-MSNs and a net decrease in the firing of D2-MSNs; consequently, increased striatal DA inhibits projection neurons of the VP/EP/SNr. Conversely, decreased DA concentration results in a net decrease in the firing of D1-MSNs, and in a net increase in the firing of D2-MSNs, thereby increasing the activity of the VP/EP/SNr. (Detailed steps are explained in the next section 4.5.)

This hypothesis is based on two key sets of observations. First, injections of cocaine, which increase extracellular concentration of striatal DA, preferentially activate D1-MSNs over D2-MSNs, while injections of DA receptor antagonists selectively activate D2-MSNs as indicated by c-fos and other early gene signals [203]. Consistently, monkeys treated with MPTP, which damages DA neurons, display abnormally hypoactive external GP neurons and hyperactive internal GP (i.e., EP) neurons [204]. This observation supports the notion that a decrease in striatal DA concentration increases the activity of D2-MSNs, which project to the external GP, thereby inhibiting them; decreased DA activity decreases firing of D1-MSNs, which project to the EP, thereby disinhibiting them.

In addition, optogenetic excitation of D1-MSNs in the striatum has been shown to be rewarding, whereas optogenetic excitation of D2-MSNs is aversive [89]. Recent findings using optogenetic or chemogenetic procedures support the view that increased and decreased activity of D1-MSNs leads to increased and decreased conditioned approach behavior, respectively, whereas increased and decreased activity of D2-MSNs leads to opposite consequences, namely decreased and increased conditioned approach behavior, respectively. Consistently, hyperexcitation of D1-MSNs makes mice more sensitive to cocaine reward, whereas hyperexcitation of D2-MSNs make mice less sensitive to cocaine reward [205]. Similarly, activation of VStr D2-MSNs suppresses both cocaine-taking and -seeking behavior, while inhibition of D2-MSNs increases cocaine-seeking behavior [206]. Moreover, selective elimination of D2-MSNs enhances the conditioned place preference effects of amphetamine [207]. Consistently, selective inhibition of D1-MSNs disrupts the locomotor sensitization effect of repeated injections of amphetamine, whereas selective inhibition of D2-MSNs potentiates locomotor sensitization [208].

4.5. Circuit loops

BG circuit loops may stabilize neural activity to maintain an approach motivational state. Discussed below are three complementary and interrelated circuit pathways that may play important roles in maintaining the motivational state regulated by DA signals (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Approach-motivation circuit-loops. The connectivity diagram of Figure 3A is slightly simplified for clearer presentation of information flow shown in three circuits: (a) BG-thalamo-cortical loop: Limbic striatum → VP/EP/SNr → MD/VM → limbic cortex → limbic striatum. (b) BG-thalamic loop: Limbic striatum → VP/EP/SNr → PV/PF → limbic striatum. (c) BG-habenulo-mesencephalic loop: Limbic striatum → EP → LHb → RMTg/VTA → VTA/SNc → limbic striatum. See the legend of Figure 3A for abbreviations. Note that the GP and STh are involved in motivational processes and send signals to the EP and SNr. While they are not shown here, to keep presentation simple, their roles are explained in text.

Figure 5 details the inter-regional sequence of events for each circuit pathway participating in motivational state. Excited D1-MSNs inhibit neurons in the VP, EP, and SNr [209–213], while inhibited D2-MSNs disinhibit VP/GP GABAergic neurons projecting to the STh, resulting in reduced excitatory transmission from STh neurons projecting to the VP/EP/SNr [214, 215] (Fig. 5A). Thus, the net effect of increased striatal DA activity is to inactivate VP/EP/SNr neurons projecting to thalamic structures (Fig. 4). These differential actions of DA on D1- and D2-MSNs and thereby between direct and indirect pathways are consistent with the finding that simultaneous stimulation of D1 and D2 receptors in the VStr is more rewarding than one or the other alone [55]. Moreover, the rewarding effects of DAergic drug administration or stimulation of VTA DA neurons and conditioned approach behavior are attenuated by the blockade of either D1 or D2 receptors [55, 56, 58, 67, 68, 74]. In contrast, decreased DA concentration in the limbic striatum should result in opposite consequences, leading to the activation of VP/EP/SNr projection neurons (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Inter-regional sequence of events between midbrain DA neurons and VP/EP/SNr neurons.

4.6. BG-thalamo-cortical circuit loops

Certain thalamic regions are strongly linked with the prefrontal cortex, amygdala and VStr, and therefore have been referred to as the limbic thalamus and implicated in affective processes [216, 217]. They include the PV, PF, CM, MD and VM. While VP and EP neurons can be GABAergic, glutamatergic or cholinergic neurons [149, 150, 167, 218–223], VP/EP/SNr neurons that project to the limbic thalamus [136, 144, 145, 147, 149, 157, 158, 224] are strictly GABAergic, because electrical stimulation of the VP/EP/SNr results in monosynaptic inhibition of thalamic neurons [225–229] (Fig. 4(a),(b)). These neurons are tonically active; therefore, inhibition of VP/EP/SNr neurons disinhibits limbic thalamic neurons projecting to the striatum and to the cortex, leading back to the activation of striatal neurons (Fig. 6A,B). We hypothesize that activation of limbic thalamic neurons does not result in equal excitatory activity between D1-and D2-MSNs, but a greater firing increase in D1-MSNs than D2-MSNs, because stimulation of the thalamic regions induces reward in rats [230, 231] and humans [38, 39] as shown by self-stimulation behavior. Unfortunately, behavioral data concerning motivational roles of the limbic thalamus are limited, though new data appear promising [232–234].

Figure 6.

Inter-regional sequence of events starting from VP/EP/SNr neurons through thalamo-cortical (A) or thalamo-striatal (B) routes or from EP neurons through habenulo-mesencephalic route (C). We postulated that activation of limbic thalamic neurons activates D2-MSNs shown in dotted-square less than D1-MSNs (A, B).

Thalamo-cortical pathways and meso-striatal DA systems appear to affect each other. For example, novel environments, which demand increased thalamo-cortical processing [235, 236] to process potential dangers and opportunities, increase c-Fos expression in VStr and DStr neurons, and do so significantly more with injections of psychomotor stimulant drugs [236]. Consistently, the rewarding and locomotor activity effects of psychostimulant drugs are significantly augmented in a novel environment compared to a home environment [237–240].

4.7. BG-LHb-midbrain circuit loops

An intravenous injection of cocaine, which increases striatal DA concentration, decreases the activity of LHb neurons for a few minutes, effects that are correlated with reward as shown by conditioned place preference [241, 242]. After this period, LHb neurons no longer display suppressed activity, and some neurons display rebound activation for a few minutes, an effect that is correlated with aversion [241, 242]. These motivational effects of intravenous injections of cocaine can be understood within the context of the BG-LHb-midbrain circuit loops.

The LHb receives glutamatergic and GABAergic inputs from the EP and GABAergic inputs from the VP [167–170]. It is not known whether VP GABAergic neurons participate in LHb activity after altered concentration of striatal DA. If they do, they must receive afferents from D2-MSNs, which are generally inhibited by increased striatal DA concentration, so that VP GABAergic neurons are disinhibited for inhibition of LHb neurons. However, there are no data to support this view. A recent study found that EP projections to the LHb contain both glutamate and GABA; therefore, VP projections to the LHb may also be glutamatergic and GABAergic. Empirical investigation is needed to elucidate these questions.

A clearer understanding is emerging regarding how EP neurons alter the activity of LHb and DA neurons (Fig. 6C). The rodent EP is organized in such a way that while the posterior part contains GABAergic neurons projecting to the thalamus, the anterior part contains glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons projecting to the LHb [151–154, 167, 222]. A half of the neurons contain both glutamate and GABA, while 10% contain GABA only, and 40% contain glutamate only [170]. The net effect of activating EP-LHb neurons is excitation, increased LHb glutamate transmission, and in turn, decreased VStr DA concentration and thereby aversion [167, 243]; consistently, the blockade of glutamatergic inputs to the LHb increases VStr DA concentration [243].

LHb neurons appear to di-synaptically inhibit VTA/SNc DA neurons: LHb neurons send excitatory projections to GABAergic neurons localized in the VTA and the RMTg; these GABA neurons, in turn, inhibit VTA/SNc DA neurons [244–246]. Such understanding aroused from the remarkable observation of Matsumoto and Hikosaka, who found an intimate relationship between LHb and DA neurons with respect to reward and reward omission [245]. Whereas DA neurons become more active upon the presentation of unexpected rewards or reward-predicting cues, and become less active upon the absence of expected rewards (omission) or omission-predicting cues [247], LHb neurons display inverse properties. LHb neurons become inhibited upon the presentation of unexpected rewards or reward-predicting cues, and become excited upon the omission or omission-predicting cues [245].

However, it is unclear how exactly GABAergic neurons control DA neurons. VTA GABA neurons display activation pattern that is quite distinct from that of DA neurons during appetitive tasks: While DA neurons largely respond discretely to reward-related stimuli, VTA GABA neurons display ramping activity upon reward-predicting cues and peak at the delivery of reward [248]. As discussed above in section 3.2, prolonged anticipatory activity of DA is observed under certain condition [112, 113]. One possibility is that non-LHb sources provide excitatory inputs to both DA and GABA neurons during reward anticipation, and because of the inhibitory action of GABA neurons over DA neurons, DA neurons do not readily display prolonged anticipatory activity. Non-LHb sources such as the pedunculopontine tegmental region may be responsible for the phasic activity of DA neurons [249, 250].

In contrast, RMTg GABA neurons do not display an activity pattern similar to VTA GABA neurons. RMTg GABA neurons, like LHb neurons, tend to become inactive upon reward-predicting stimuli [173]. The inhibitory action of GABAergic neurons over the VTA or RMTg neurons is consistent with behavioral findings that activation of VTA or RMTg GABA neurons is aversive [242, 251], and their inactivation with local injections of mu-opioid-receptor agonists is rewarding [252, 253]. Although more precise understanding of circuitry is in order, this model explains how increased DA transmission in the DStr results in activation of EP-LHb neurons, which in turn, inactivate VTA and RMTg GABA neurons, thereby disinhibiting DA neurons and providing positive feedback.

5. Concluding remarks

Recent research has indicated that more extensive areas are involved in regulating DA-modulated motivational state than previously thought. We proposed a model that explains how increased and decreased concentrations of striatal DA induce reward and aversion, respectively, and regulate approach behavior. We also proposed a model that elucidates circuit loops affected by increased and decreased concentrations of striatal DA for regulation of motivation and mood. These models would help to stimulate research to better understand the roles of DA in motivational functions, drug abuse and affective disorders.

Highlights.

Substantia nigra dopamine neurons projecting to the striatum regulate mood.

Increased activity induces reward; decreased activity induces aversion.

Nigrostriatal dopamine neurons may also regulate approach motivation.

Mood and approach motivation may be altered by the thalamo-cortical circuit loop.

Mood and approach motivation may also be altered by the habenulo-mesencephalic loop.

Acknowledgments

The Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health supported the authors to write the present paper. The authors would like to thank Dong Wang and Aleksandr Talishinsky for discussion concerning the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ikemoto S, Panksepp J. The role of nucleus accumbens dopamine in motivated behavior: A unifying interpretation with special reference to reward-seeking. Brain Research Reviews. 1999;31:6–41. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ikemoto S. Dopamine reward circuitry: Two projection systems from the ventral midbrain to the nucleus accumbens-olfactory tubercle complex. Brain Research Reviews. 2007;56:27–78. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikemoto S. Brain reward circuitry beyond the mesolimbic dopamine system: A neurobiological theory. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;35:129–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ikemoto S, Bonci A. Neurocircuitry of drug reward. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76(Pt B):329–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wise RA. Catecholamine theories of reward: A critical review. Brain Research. 1978;152:215–47. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90253-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wise RA, Bozarth MA. A Psychomotor Stimulant Theory of Addiction. Psychological review. 1987;94:469–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koob GF. Drugs of abuse: Anatomy, pharmacology and function of reward pathways. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1992;13:177–84. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90060-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willner P. Dopamine and depression: A review of recent evidence. I. Empirical studies. Brain Research Reviews. 1983;6:211–24. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(83)90005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swerdlow NR, Koob GF. Dopamine, schizophrenia, mania, and depression: Toward a unified hypothesis of cortico-striatopallido-thalamic function. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1987;10:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA., Jr The Mesolimbic Dopamine Reward Circuit in Depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59:1151–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tye KM, Mirzabekov JJ, Warden MR, Ferenczi EA, Tsai HC, Finkelstein J, et al. Dopamine neurons modulate neural encoding and expression of depression-related behaviour. Nature. 2013;493:537–41. doi: 10.1038/nature11740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russo SJ, Nestler EJ. The brain reward circuitry in mood disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14:609–25. doi: 10.1038/nrn3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lammel S, Tye KM, Warden MR. Progress in understanding mood disorders: optogenetic dissection of neural circuits. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2014;13:38–51. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaudhury D, Walsh JJ, Friedman AK, Juarez B, Ku SM, Koo JW, et al. Rapid regulation of depression-related behaviours by control of midbrain dopamine neurons. Nature. 2013;493:532–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wise RA. Roles for nigrostriatal—not just mesocorticolimbic—dopamine in reward and addiction. Trends in Neurosciences. 2009;32:517–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ilango A, Kesner AJ, Keller KL, Stuber GD, Bonci A, Ikemoto S. Similar roles of substantia nigra and ventral tegmental dopamine neurons in reward and aversion. J Neurosci. 2014;34:817–22. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1703-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossi MA, Sukharnikova T, Hayrapetyan VY, Yang L, Yin HH. Operant Self-Stimulation of Dopamine Neurons in the Substantia Nigra. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watabe-Uchida M, Zhu L, Ogawa SK, Vamanrao A, Uchida N. Whole-brain mapping of direct inputs to midbrain dopamine neurons. Neuron. 2012;74:858–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings JL. Frontal-subcortical circuits and human behavior. Archives of Neurology. 1993;50:873–80. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540080076020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheline YI. Neuroimaging studies of mood disorder effects on the brain. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:338–52. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beblo T, Wallesch CW, Herrmann M. The crucial role of frontostriatal circuits for depressive disorders in the postacute stage after stroke. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology and Behavioral Neurology. 1999;12:236–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vataja R, Pohjasvaara T, Leppävuori A, Mäntylä R, Aronen HJ, Salonen O, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging correlates of depression after ischemic stroke. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:925–31. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vataja R, Leppävuori A, Pohjasvaara T, Mäntylä R, Aronen HJ, Salonen O, et al. Poststroke Depression and Lesion Location Revisited. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2004;16:156–62. doi: 10.1176/jnp.16.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jorge RE, Starkstein SE, Robinson RG. Apathy following stroke. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;55:350–4. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adam R, Leff A, Sinha N, Turner C, Bays P, Draganski B, et al. Dopamine reverses reward insensitivity in apathy following globus pallidus lesions. Cortex. 2013;49:1292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhatia KP, Marsden CD. The behavioural and motor consequences of focal lesions of the basal ganglia in man. Brain. 1994;117:859–76. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.4.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider F, Habel U, Volkmann J, Regel S, Kornischka J, Sturm V, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus enhances emotional processing in Parkinson disease. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:296–302. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mallet L, Schüpbach M, N’Diaye K, Remy P, Bardinet E, Czernecki V, et al. Stimulation of subterritories of the subthalamic nucleus reveals its role in the integration of the emotional and motor aspects of behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:10661–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610849104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Jeune F, Drapier D, Bourguignon A, Péron J, Mesbah H, Drapier S, et al. Subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson disease induces apathy: A PET study. Neurology. 2009;73:1746–51. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c34b34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Péron J, Frühholz S, Vérin M, Grandjean D. Subthalamic nucleus: A key structure for emotional component synchronization in humans. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2013;37:358–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kempton MJ, Salvador Z, Munafò MR, Geddes JR, Simmons A, Frangou S, et al. Structural neuroimaging studies in major depressive disorder: Meta-analysis and comparison with bipolar disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:675–90. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drevets WC, Price JL, Furey ML. Brain structural and functional abnormalities in mood disorders: Implications for neurocircuitry models of depression. Brain Structure and Function. 2008;213:93–118. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Childress AR, et al. Cocaine cues and dopamine in dorsal striatum: Mechanism of craving in cocaine addiction. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:6583–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1544-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong DF, Kuwabara H, Schretlen DJ, Bonson KR, Zhou Y, Nandi A, et al. Increased occupancy of dopamine receptors in human striatum during cue-elicited cocaine craving. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2716–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fischman MW, Foltint RW, Fowler JS, Abumrad NN, et al. Relationship between subjective effects of cocaine and dopamine transporter occupancy. Nature. 1997;386:827–30. doi: 10.1038/386827a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitterschiffthaler MT, Fu CHY, Dalton JA, Andrew CM, Williams SCR. A functional MRI study of happy and sad affective states induced by classical music. Human Brain Mapping. 2007;28:1150–62. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mühlberger A, Wieser MJ, Gerdes AB, Frey MCM, Weyers P, Pauli P. Stop looking angry and smile, please: Start and stop of the very same facial expression differentially activate threat-and reward-related brain networks. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2011;6:321–9. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bishop MP, Thomas Elder S, Heath RG. Intracranial self-stimulation in man. Science. 1963;140:394–6. doi: 10.1126/science.140.3565.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heath RG. Electrical self-stimulation of the brain in man. The American journal of psychiatry. 1963;120:571. doi: 10.1176/ajp.120.6.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glickman SE, Schiff BB. A BIOLOGICAL THEORY OF REINFORCEMENT. Psychological review. 1967;74:81–109. doi: 10.1037/h0024290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landauer TK. Reinforcement as consolidation. Psychological review. 1969;76:82–96. doi: 10.1037/h0026746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hebb DO. Drives and the C.N.S. (conceptual nervous system) Psychological review. 1955;62:243–54. doi: 10.1037/h0041823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gallistel CR. Motivating effects in self-stimulation. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1966;62:95–101. doi: 10.1037/h0023472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gallistel CR. The incentive of brain-stimulation reward. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1969;69:713–21. doi: 10.1037/h0028232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85:5274–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yokel RA, Wise RA. Increased lever pressing for amphetamine after pimozide in rats: Implications for a dopamine theory of reward. Science. 1975;187:547–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1114313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ettenberg A, Pettit HO, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Heroin and cocaine intravenous self-administration in rats: Mediation by separate neural systems. Psychopharmacology. 1982;78:204–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00428151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGregor A, Roberts DCS. Dopaminergic antagonism within the nucleus accumbens or the amygdala produces differential effects on intravenous cocaine self-administration under fixed and progressive ratio schedules of reinforcement. Brain Research. 1993;624:245–52. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90084-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maldonado R, Robledo P, Chover AJ, Caine SB, Koob GF. D1 dopamine receptors in the nucleus accumbens modulate cocaine self-administration in the rat. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 1993;45:239–42. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lyness WH, Friedle NM, Moore KE. Destruction of dopaminergic nerve terminals in nucleus accumbens: Effect on d-amphetamine self-administration. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1979;11:553–6. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(79)90040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roberts DCS, Koob GF, Klonoff P, Fibiger HC. Extinction and recovery of cocaine self-administration following 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the nucleus accumbens. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 1980;12:781–7. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(80)90166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roberts DCS, Corcoran ME, Fibiger HC. On the role of ascending catecholaminergic systems in intravenous self administration of cocaine. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1977;6:615–20. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(77)90084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ikemoto S, Wise RA. Mapping of chemical trigger zones for reward. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carlezon WA, Jr, Devine DP, Wise RA. Habit-forming actions of nomifensine in nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology. 1995;122:194–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02246095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ikemoto S, Glazier BS, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Role of dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in the nucleus accumbens in mediating reward. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:8580–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08580.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ikemoto S. Involvement of the Olfactory Tubercle in Cocaine Reward: Intracranial Self-Administration Studies. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:9305–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09305.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ikemoto S, Qin M, Liu ZH. The functional divide for primary reinforcement of D-amphetamine lies between the medial and lateral ventral striatum: Is the division of the accumbens core, shell, and olfactory tubercle valid? Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:5061–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0892-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shin R, Qin M, Liu ZH, Ikemoto S. Intracranial self-administration of MDMA into the ventral striatum of the rat: Differential roles of the nucleus accumbens shell, core, and olfactory tubercle. Psychopharmacology. 2008;198:261–70. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1131-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodd-Henricks ZA, McKinzie DL, Li TK, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Cocaine is self-administered into the shell but not the core of the nucleus accumbens of Wistar rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2002;303:1216–26. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.038950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Di Chiara G, Bassareo V, Fenu S, De Luca MA, Spina L, Cadoni C, et al. Dopamine and drug addiction: The nucleus accumbens shell connection. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:227–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pontieri FE, Tanda G, Di Chiara G. Intravenous cocaine, morphine, and amphetamine preferentially increase extracellular dopamine in the “shell” as compared with the “core” of the rat nucleus accumbens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:12304–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taylor JR, Robbins TW. Enhanced behavioural control by conditioned reinforcers following microinjections of d-amphetamine into the nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology. 1984;84:405–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00555222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shin R, Cao J, Webb SM, Ikemoto S. Amphetamine administration into the ventral striatum facilitates behavioral interaction with unconditioned visual signals in rats. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shippenberg TS, Bals-Kubik R, Huber A, Herz A. Neuroanatomical substrates mediating the aversive effects of D-1 dopamine receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology. 1991;103:209–14. doi: 10.1007/BF02244205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu ZH, Shin R, Ikemoto S. Dual role of medial A10 dopamine neurons in affective encoding. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:3010–20. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ikemoto S, Panksepp J. Dissociations between appetitive and consummatory responses by pharmacological manipulations of reward-relevant brain regions. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1996;110:331–45. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nicola SM. The flexible approach hypothesis: Unification of effort and cue-responding hypotheses for the role of nucleus accumbens dopamine in the activation of reward-seeking behavior. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:16585–600. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3958-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.du Hoffmann J, Nicola SM. Dopamine Invigorates Reward Seeking by Promoting Cue-Evoked Excitation in the Nucleus Accumbens. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34:14349–64. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3492-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fiorillo CD. Two Dimensions of Value: Dopamine Neurons Represent Reward But Not Aversiveness. Science. 2013;341:546–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1238699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tsai HC, Zhang F, Adamantidis A, Stuber GD, Bond A, De Lecea L, et al. Phasic firing in dopaminergic neurons is sufficient for behavioral conditioning. Science. 2009;324:1080–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1168878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Witten I, Steinberg E, Lee S, Davidson T, Zalocusky K, Brodsky M, et al. Recombinase-driver rat lines: Tools, techniques, and optogenetic application to dopamine-mediated reinforcement. Neuron. 2011;72:721–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ilango A, Kesner AJ, Broker CJ, Wang DV, Ikemoto S. Phasic excitation of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons potentiates the initiation of conditioned approach behavior: Parametric and reinforcement-schedule analyses. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2014;8:155. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim T-i, McCall JG, Jung YH, Huang X, Siuda ER, Li Y, et al. Injectable, Cellular-Scale Optoelectronics with Applications for Wireless Optogenetics. Science. 2013;340:211–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1232437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Steinberg EE, Boivin JR, Saunders BT, Witten IB, Deisseroth K, Janak PH. Positive reinforcement mediated by midbrain dopamine neurons requires D1 and D2 receptor activation in the nucleus accumbens. PLoS ONE. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Corbett D, Wise RA. Intracranial self-stimulation in relation to the ascending dopaminergic systems of the midbrain: A moveable electrode mapping study. Brain Research. 1980;185:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90666-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Routtenberg A, Malsbury C. Brainstem pathways of reward. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1969;68:22–30. doi: 10.1037/h0027655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ritter S, Stein L. Self-stimulation in the mesencephalic trajectory of the ventral noradrenergic bundle. Brain Research. 1974;81:145–57. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90484-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ranck JB., Jr Which elements are excited in electrical stimulation of mammalian central nervous system: a review. Brain Research. 1975;98:417–40. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nowak LG, Bullier J. Axons, but not cell bodies, are activated by electrical stimulation in cortical gray matter. I. Evidence from chronaxie measurements. Experimental Brain Research. 1998;118:477–88. doi: 10.1007/s002210050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Histed MH, Bonin V, Reid RC. Direct Activation of Sparse, Distributed Populations of Cortical Neurons by Electrical Microstimulation. Neuron. 2009;63:508–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lammel S, Lim BK, Ran C, Huang KW, Betley MJ, Tye KM, et al. Input-specific control of reward and aversion in the ventral tegmental area. Nature. 2012;491:212–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brischoux F, Chakraborty S, Brierley DI, Ungless MA. Phasic excitation of dopamine neurons in ventral VTA by noxious stimuli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:4894–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811507106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Two types of dopamine neuron distinctly convey positive and negative motivational signals. Nature. 2009;459:837–41. doi: 10.1038/nature08028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ungerstedt U. Stereotaxic mapping of the monoamine pathways in the rat brain. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, Supplement. 1971;367:1–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201x.1971.tb10998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fallon JH, Moore RY. Catecholamine innervation of the basal forebrain. IV. Topography of the dopamine projection to the basal forebrain and neostriatum. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1978;180:545–72. doi: 10.1002/cne.901800310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gerfen CR, Herkenham M, Thibault J. The neostriatal mosaic: II. Patch- and matrix-directed mesostriatal dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic systems. Journal of Neuroscience. 1987;7:3915–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-12-03915.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Phillips AG, Carter DA, Fibiger HC. Dopaminergic substrates of intracranial self-stimulation in the caudate-putamen. Brain Research. 1976;104:221–32. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90615-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.White NM, Hiroi N. Preferential localization of self-stimulation sites in striosomes/patches in the rat striatum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:6486–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kravitz AV, Tye LD, Kreitzer AC. Distinct roles for direct and indirect pathway striatal neurons in reinforcement. Nature Neuroscience. 2012;15:816–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2000:155–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Devinsky O, Morrell MJ, Vogt BA. Contributions of anterior cingulate cortex to behaviour. Brain. 1995;118:279–306. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.1.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Price JL, Drevets WC. Neural circuits underlying the pathophysiology of mood disorders. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2012;16:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Montague PR, Dayan P, Sejnowski TJ. A framework for mesencephalic dopamine systems based on predictive Hebbian learning. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:1936–47. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01936.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science. 1997;275:1593–9. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Glimcher PW. Understanding dopamine and reinforcement learning: The dopamine reward prediction error hypothesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:15647–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014269108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Steinberg EE, Keiflin R, Boivin JR, Witten IB, Deisseroth K, Janak PH. A causal link between prediction errors, dopamine neurons and learning. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:966–73. doi: 10.1038/nn.3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pickens R, Thompson T. Cocaine-reinforced behavior in rats: effects of reinforcement magnitude and fixed-ratio size. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1968;161:122–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yokel RA, Pickens R. Drug level of d and l amphetamine during intravenous self administration. PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGIA. 1974;34:255–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00421966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]