Abstract

Objective

In the presurgical workup of MRI-negative (MRI−, or “nonlesional”) pharmacoresistant focal epilepsy (PFE) patients, discovering a previously undetected lesion can drastically change the evaluation and likely improve surgical outcome. Our study utilizes a voxel-based MRI post-processing technique, implemented in a morphometric analysis program (MAP), to facilitate detection of subtle abnormalities in a consecutive cohort of MRI− surgical candidates.

Methods

Included in this retrospective study was a consecutive cohort of 150 MRI-surgical patients. MAP was performed on T1-weighted MRI, with comparison to a scanner-specific normal database. Review and analysis of MAP were performed blinded to patients’ clinical information. The pertinence of MAP+ areas was confirmed by surgical outcome and pathology.

Results

MAP showed a 43% positive rate, sensitivity of 0.9 and specificity of 0.67. Overall, patients with MAP+ region completely resected had the best seizure outcomes, followed by the MAP− patients, and patients who had no/partial resection of the MAP+ region had the worst outcome (p<0.001). Subgroup analysis revealed that visually identified subtle findings are more likely correct if also MAP+. False-positive rate in 52 normal controls was 2%. Surgical pathology of the resected MAP+ areas contained mainly non-balloon-cell FCD. Multiple MAP+ regions were present in 7% of patients.

Conclusions

MAP can be a practical and valuable tool to: (1) guide the search for subtle MRI abnormalities, and (2) confirm visually identified questionable abnormalities in patients with PFE due to suspected FCD. A MAP+ region, when concordant with the patient’s electro-clinical presentation, should provide a legitimate target for surgical exploration.

Keywords: epilepsy, MRI, presurgical evaluation, image processing, MRI-negative epilepsy, voxel-based morphometric MRI post-processing, focal cortical dysplasia

Introduction

In the presurgical evaluation of pharmacoresistant focal epilepsies (PFE), the importance of accurately detecting and delineating an MRI lesion cannot be overstated. Discovering a previously undetected lesion can drastically change the presurgical planning and likely improve surgical outcome. The absence of a discrete lesion on MRI has consistently been shown as a predictor for surgical failure.1, 2 In contrast, MRI-positive (MRI+) surgical candidates have demonstrated seizure-free outcome more than two times higher than MRI-negative (MRI−) patients.3

Focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) is the most common underlying pathology in epilepsies with apparently normal MRI.4 Typical MRI findings of FCD include blurring of the gray-white matter junction, abnormally thickened cortex, decreased cortical T1 signal intensity, increased cortical T2/FLAIR signal intensity, and T2/FLAIR subcortical abnormality. FCD lesions are generally much more difficult to detect compared with other types of lesions, as they can be quite subtle with small sizes, appearing buried in the complex convexities of the neocortex. Given the practical constraints of time, MRI readers may miss those FCD lesions that are only discerned with increased scrutiny.5, 6 This is especially problematic when noninvasive clinical data, such as scalp EEG and semiology, fail to point to a clear sublobar/lobar epileptogenic area. Without guidance from other noninvasive investigations, MRI readers lack a testable anatomic hypothesis and may falsely conclude that a study is “MRI−”, even after focused re-review of the MRI. Under these circumstances, a whole-brain MRI post-processing technique that directs the reader’s attention to potentially dysplastic abnormalities could prove to be essential. In the current study, we utilized a voxel-based MRI morphometric analysis program (MAP), implemented based on algorithms of the freely available statistical parametric mapping (SPM) software. Modeling the characteristic MRI features of FCD,7 MAP guides the MRI reader’s attention to suspicious brain regions characterized by subtle blurring of the gray-white junction, abnormal cortical gyration, or abnormal cortical thickness. MAP has been employed to detect subtle cortical malformations with higher sensitivity. 6, 8-12

The idea of assisting FCD detection using advanced image post-processing strategies has been the topic of many previous studies, which were elegantly summarized in the review by Bernasconi et al.13 Examples of these advanced image post-processing techniques include variations of voxel-based morphometry to quantify gray and white matter concentration;14-20 generation of FCD-specific feature maps such as cortical thickness, gray-white gradient, and relative image intensity;8, 21-24 quantitative voxel-based intensity analysis of T2 relaxometry or T2 FLAIR images;25-28 curvilinear reformatting of volumetric MRI;29-31 and sulcal morphometric analysis to identify abnormally deep sulci.32

Two major limitations exist in the literature. Firstly, few studies systematically examined the effectiveness of MRI post-processing in large and well-defined cohort of MRI− PFE patients. Secondly, semiology and scalp-EEG monitoring results were often used to define the ictal onset zone and surmise the location of the “putative” epileptogenic focus.26, 33 This approach may be justifiable for more “straightforward” cases, but has significant limitations when applied to the more complex MRI− patients. The purpose of this study is to retrospectively review a single center’s experience with MAP in a well-defined, consecutive cohort of MRI− PFE patients. We hypothesize that complete resection of the MAP+ region positively associates with seizure-free outcome.

In the management of MRI− patients, previously unnoted MRI findings are often identified based on convergent multi-modal data that are gathered and put together in the course of non-invasive evaluation. The validity of such findings has not been systematically studied in the literature. A second aim of our study is to examine the role of MAP in patients with visually identified but questionable MRI changes. We hypothesize that subtle MRI changes - that are visually identified during focused re-review of the MRI guided by non-invasive data – are more likely to represent true positive results, when they are supported by a quantitative image post-processing measure (such as MAP).

Patients and Methods

Design and Rationale

This retrospective study was approved by the Cleveland Clinic institutional review board. MAP was not previously available, and therefore did not influence the preoperative hypothesis or surgical decision-making. Review and analysis of MAP were performed blinded to patients’ clinical information. In all patients, the strategy for intracranial EEG (ICEEG) implantation and surgical resection was discussed during a patient management conference (PMC) based on multi-modal data including MRI, video-EEG, PET, subtraction ictal SPECT coregistered to MRI (SISCOM), and Magnetic Source Imaging (MSI). All the MRI scans were acquired with adherence to a standard epilepsy protocol34; all the available sequences were reviewed, with special emphasis on T1-weighted, T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences.

Patient Selection

We identified patients by reviewing our surgical database over a 10-year period (2002-2011). Patients were included if they: (1) had a pre-operative 1.5 or 3-Tesla MRI with T1-weighted Magnetization Prepared Rapid Acquisition with Gradient Echo (MPRAGE) sequence; (2) had initial MRI read as negative before PMC discussion; (3) underwent a postoperative MRI; and (4) had more than 12 months of postsurgical follow-up. Patients were excluded if they: (1) were less than 5 years old, and (2) had poor MRI image quality. Since hippocampal sclerosis (HS) does not affect the post-processing or the interpretation, patients with HS were not excluded.

Patient Grouping

All patients were analyzed as an overall group, and were further divided into two subgroups based on a review of the clinical notes from PMC. During PMC, all preoperative MRI scans were re-reviewed in detail by dedicated neuroradiologists with expertise in epilepsy imaging, epileptologists and epilepsy neurosurgeons. At times, previously unnoted MRI findings were identified during PMC when multi-modal data were discussed and integrated in the context of each patient’s individual electroclinical presentation. Patients in our study were thus divided into two subgroups: (1) “Subtly Lesional” subgroup consisted of patients in whom previously unnoted findings were identified during expert re-review of MRI in presurgical PMC; and (2) “Strictly Nonlesional” subgroup when the MRI was still considered negative even after focused re-review in PMC.

MRI Post-processing

MAP was carried out using SPM toolbox (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK) in Matlab 2007a (MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts) following previously established methods.8, 9 MAP was performed on T1-weighted MPRAGE images. The majority of patients (97%) were scanned at our center, following a standard epilepsy protocol in adherence with literature.34 A small number of patients (3%) had studies from outside that were deemed appropriate by our neuroradiologists as the MRI contained all the necessary sequences. Due to the time span of the presurgical evaluation of the patients selected, 96 patients had 1.5T MRI (best available at the time), and 54 patients had 3T MRI. For those patients who underwent MRI acquisition using a 3T Siemens Trio scanner, we used a normal database constructed specifically for this scanner, comprising a database of 90 normal subjects (41 females, 49 males: mean age 42.0 years, range 22–80 years), whose MRIs were acquired on the same 3T Siemens Trio scanner from our institute, using the same MPRAGE sequence as the patients. For patients with 1.5T MRI or 3T MRI not acquired on Siemens Trio, we used a 1.5T and 3T average normal database of 150 subjects (70 females, 80 males: mean age at MRI 30.9 years, range 15–77 years), with MRIs acquired on five different MRI scanners, which was kindly provided along with the MAP program.9 The computed output consists of three volumetric statistical maps, called the junction, extension, and thickness maps. For each individual patient, the three maps highlight brain structures deviating from the average normal brain based on high z-scores, which may correlate with the presence of subtle features of FCD on the underlying MRI. The junction map is sensitive to blurring of the gray-white matter junction; the extension map is sensitive to abnormal gyration and extension of gray matter into white matter; and the thickness map is sensitive to abnormal cortical thickness.

A blinded reviewer (ZIW) used the z-score threshold of 4 to identify candidate MAP+ regions on the junction file. The reviewer also examined whether there was an accompanying region on the extension file (z > 6) and the thickness file (z > 4). The choice of z-score threshold was consistent with those reported in the literature.11, 12, 35 Candidate MAP+ regions were searched for in the entire brain. High-z-score areas caused by signal inhomogeneities due to technical reasons and nonspecific white matter lesions were not included. All candidate MAP+ regions were then addressed by a board-certified neuroradiologist (SEJ), who conducted a corresponding focused re-review of the pre-surgical clinical MRI (with T1-weighted MPRAGE, T2-weighted FLAIR and TSE sequences, imaging parameters detailed in our previous publication11). The neuroradiologist was also blinded to the patient’s clinical and surgical information. Examination of the MAP and MRI studies was based on visual inspection alone without using automated detection algorithms. If the neuroradiologist agreed that the conventional MRI showed subtle abnormalities at these sites, the patient was labeled as MAP+. To minimize subjectivity, SEJ applied a consistent 5 point scale to rate the abnormality in each patient: 1: nothing; 2: unlikely; 3: ambiguous; 4: possible; 5: most likely. Features suggesting non-significance were the presence and amount of image noise, such as poor signal (lower field, old head coil), excess motion and pulsation artifacts. Features favoring reality include typical MRI findings of FCD seen on more than one slice of more than one sequence, such as indistinction of gray-white junction, T2/FLAIR signal abnormality, T1 signal abnormality, abnormally thickened cortex, or subcortical T2/FLAIR abnormality extending along a migrational line. Other features of non significance included patterns that are generally not considered relevant to the pathophysiology of focal epileptogenesis, such as developmental venous anomaly, non-specific white matter change (particularly if the patient is older), delayed myelination, etc. Only abnormalities with ratings >= 3 were regarded as MAP+. All MAP+ patients were studied as an overall group, and subgroup analysis was performed separately for those with (ratings>3) or without (rating=3) evident abnormalities. The MAP− patients included those who had no regions exceeding the z-score threshold, and those who had candidate MAP+ regions reviewed but were rejected by the neuroradiologist (i.e., ratings <3). This methodology is consistent with our previous reports and the literature.6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 36 The patients’ scans were randomly mixed with control scans obtained from normal subjects (details in the next section). Neither the MAP reviewer nor the neuroradiologist was given prior information about whether the MRI was from a patient or control.

Normal Controls

To evaluate false positive rate, 52 normal controls were scanned. The control subjects were free of any neurological diseases, 48.1% female, with median age of 28 years (mean=29.9 years, range 23 to 66 years). Controls were reviewed with the same methodology as described in the previous section.

Surgical Pathology

Available microscopic slides from surgical resections were reviewed in all cases. FCD was classified according to the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification.37 Negative pathology was defined by a finding of gliosis, hamartia, or the absence of any identifiable microscopic/histological abnormalities. Positive pathology was defined by a finding of FCD, HS, or others (details in Results).

Statistical Analysis

The postoperative MRI of each patient was co-registered with the preoperative MRI using the SPM toolbox within Matlab, so that complete or incomplete resection of the MAP+ areas can be determined. Patients were divided into the following categories: MAP+ region fully resected, MAP+ region not resected, MAP+ region partially resected, and MAP−. The two subgroups of patients with MAP+ region not resected or partially resected are tabulated individually in Table 2, but were mostly combined for the purposes of statistical analysis given the small number in each subgroup. In the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup, completeness of resection of the visually identified finding was determined by whether the described finding (on PMC notes) was included in the resection cavity on the postoperative MRI. Surgical outcome at 12 months was classified into two groups: completely seizure-free (Engel’s class Ia) and not seizure-free (Engel’s class Ib – IV).38 We used chi-square test to assess the relationship of parameters and seizure outcomes; Fisher’s exact test was used when N<5. T tests and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare the association of age and epilepsy duration with outcomes. Cochran–Armitage test was used for trend analysis. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated, as well as their 95% confidence intervals. Z test was used for comparison of group percentages. The Cochran–Armitage trend test was one-sided, and all the other analyses were two-sided, at a significant level of 0.05. SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. A block diagram detailing our study workflow is shown in Figure 1.

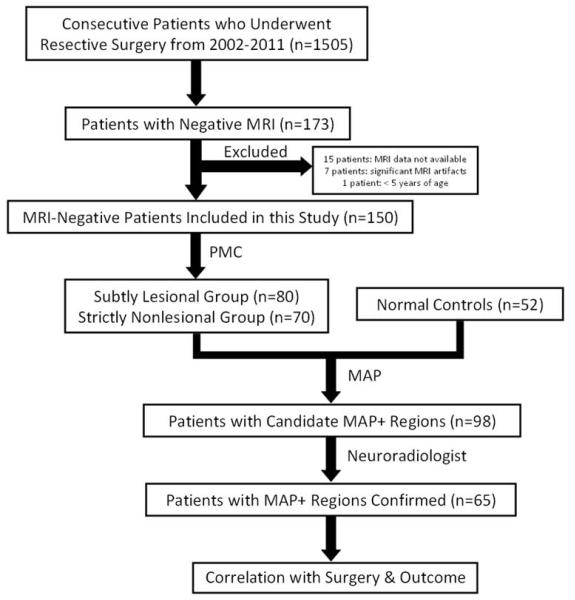

Figure 1.

Workflow of data collection and analysis. Patients were retrospectively screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The included patients were then divided into a “Subtly Lesional” subgroup and a “Strictly Nonlesional” subgroup based on the clinical notes from discussion at the patient management conference (PMC). Normal controls were randomly mixed with the patients. All the patients and controls underwent MAP processing. Candidate MAP+ regions were presented to a neuroradiologist who performed a focused re-review of the original MRI based on the MAP findings. Only when the neuroradiologist agreed that the original MRI showed subtle abnormalities at these sites, the patient was denoted as MAP+. The MAP+ regions were then compared with the location of surgical resection, and association with surgical pathology and seizure outcomes was calculated.

Results

Patient Demographics

A total of 1505 resective surgeries were performed from 2002 to 2011, from which 173 patients were MRI−. Excluding the 15 patients whose MRIs were not available, 7 patients whose MRIs had significant artifacts, and the one patient who was < 5 years of age, a total of 150 patients fulfilled selection criteria. Detailed demographics and clinical data are given in Table 1. A total of 109 patients had invasive monitoring: 77 patients underwent evaluation with subdural grid (with or without depth) electrodes placements and 32 patients had stereotactic-EEG electrode implantations (the latter became available at our center in 2009). Ninety-four patients (63%) were seizure-free at ≥12 months follow-up. Gender, handedness, age, age group (adult or pediatric), epilepsy duration, type of resection (temporal vs extratemporal), type of invasive evaluation were not significantly associated with seizure-free outcome. Moreover, there was no significant difference in seizure-free outcome between patients who were studied with intracranial electrodes versus those who were not (p=0.7).

Table 1.

Detailed demographics and clinical data of the 150 patients studied.

| Factor | Summary | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean = 28.5 (SD±14.8, range 7, 66) Median = 29 |

0.71a |

| Age Group | 0.82c | |

| Age>=18 | 114 (76%) | |

| Age<18 | 36 (24%) | |

| Epilepsy Duration | 12.5 (SD±12.5, range 1, 59) | 0.63b |

| Gender | 0.14c | |

| Female | 68 (45.3%) | |

| Male | 82 (54.7%) | |

| Handedness | 0.66c | |

| Right | 130 (87%) | |

| Left | 20 (13%) | |

| Resection Type | 0.82c | |

| Temporal | 92 (61.3%) | |

| Frontal | 36 (24%) | |

| Parietal | 8 (5.3%) | |

| Occipital | 2 (1.3%) | |

| Multi-lobar | 12 (8%) |

p-values:

=T test,

=Wilcoxon rank sum test,

=Pearson’s chi-square test.

Association of parameters and seizure outcome was tested. Testing of resection type was performed as temporal resection vs. all others. SD=standard deviation.

Positive surgical pathology included FCD in 79 (53%), HS in 11 (7%) and others in 7 (5%, which included nodular heterotopia, dual osseous metaplasia, microglial cell proliferation, senile plaques, remote infarct, and nonspecific hippocampal neuronal loss). Fifty patients (33%) had negative surgical pathology. Three patients (2%) did not have tissue sent for pathological examination. The existence of positive surgical pathology was not associated with better seizure-free outcome (p=0.16).

There were 80 patients in the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup and 70 patients in the “Strictly Nonlesional” subgroup. Similar to the overall cohort, none of the aforementioned demographics/clinical factors was significantly associated with seizure-free outcome in each of these two subgroups.

MAP+ Rate

Overall, MAP was positive in 65 of the 150 patients (43%), including 11(7%) with multiple MAP+ regions. The positive rate of MAP was 45% (36 of 80) in the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup and 41% (29 of 70) in the “Strictly Nonlesional” subgroup, which is not significantly different (p=0.66). The positive rate of MAP was 38% (35/92) in the temporal group and 52% (30/58) in the extratemporal group. Although the extratemporal group had higher MAP+ rate than the temporal group, statistically it was not significant (p=0.1).

Correlation of MAP, Resection and Outcome

As shown in Table 2, in the overall group of 150 patients, 45(90%) of the 50 patients who had the MAP+ region completely removed became seizure-free; 10(67%) of the 15 patients who did not have the MAP+ region resected had recurring seizures. Resection of the MAP+ region was significantly associated with seizure-free outcome (p<0.001). Patients with full resection of the MAP+ region had significantly better seizure outcomes than those who had no resection (p<0.001) or partial resection (p=0.005) of the MAP+ region. Sensitivity of MAP was 0.9 (95% CI: 0.78, 0.97) and specificity was 0.67 (95% CI: 0.38, 0.88). Figures 2, 3, 4 and 5 showcase patients with MAP+ regions in different lobar areas. All patients shown in Figures 2 – 5 were seizure-free after complete removal of the MAP+ region, as indicated by the post-operative MRI.

Table 2.

Detailed data used for calculation of the association between MAP resection and outcome. The MAP+ not resected and partially resected subgroups were combined for statistical testing, but the numbers for each subgroup are included in parentheses.

| Groups | Total | Seizure-free (12 m) |

Not seizure-free (12 m) |

p-value | Odds Ratios (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N=150) | |||||

| MAP+ fully resected | 50 | 45 | 5 | <0.001 d | 18.0 (4.4, 74.2) |

| MAP+ not/partially resected | 15 (6/9) | 5 (1/4) | 10 (5/5) | reference | |

| MAP− | 85 | 44 | 41 | ||

| Subtly Lesional Subgroup (n=80) | |||||

| MAP+ fully resected | 31 | 29 | 2 | 0.001 d | 58.0 (4.2, 795.2) |

| MAP+ not/partially resected | 5 (1/4) | 1 (0/1) | 4 (1/3) | reference | |

| MAP− | 44 | 26 | 18 | ||

| Strictly Nonlesional Subgroup (n=70) | |||||

| MAP+ fully resected | 19 | 16 | 3 | 0.032 d | 8.0 (1.4, 46.8) |

| MAP+ not/partially resected | 10 (5/5) | 4 (1/3) | 6 (4/2) | reference | |

| MAP− | 41 | 18 | 23 |

= Fisher’s exact test.

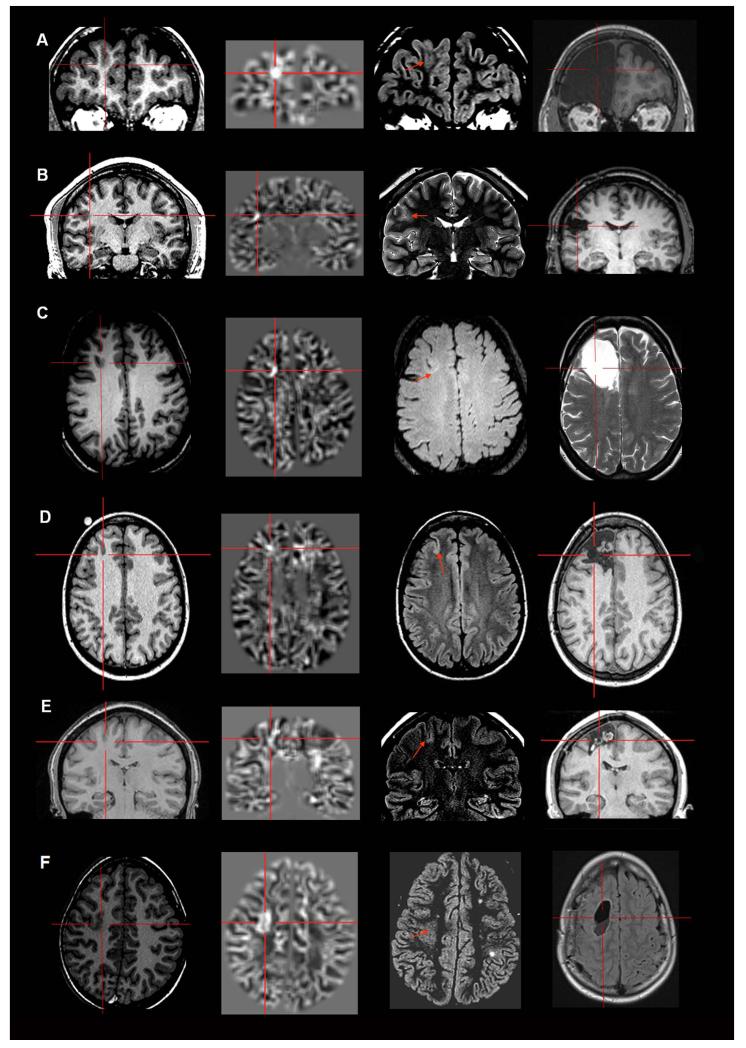

Figure 2.

Examples of six patients with MAP+ region in the frontal lobe. In Figures 2-5, the crosshairs pinpoint the location of MAP+ region. First column: T1-weighted MPRAGE images used during pre-surgical evaluation. Second column: gray-white matter junction z-score file, as the output of MAP processing of the T1-weighted image shown in column one. Third column: T2-weighted FLAIR or TSE images, chosen to best depict the MAP+ region. The arrow indicates there was accompanying T2-weighted changes in the MAP+ region, and absence of the arrow indicates that there was no corresponding T2 changes noted. Fourth column: post-surgical MRI indicating site and extent of resection. Panels A and B belong to the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup; C, D, E and F belong to the “Strictly Nonlesional” subgroup. All six cases demonstrate complete resection of the MAP+ region, and all patients remained seizure-free at 12 months. Pathology: A, C, E, F: FCD type I; B, D: FCD type II.

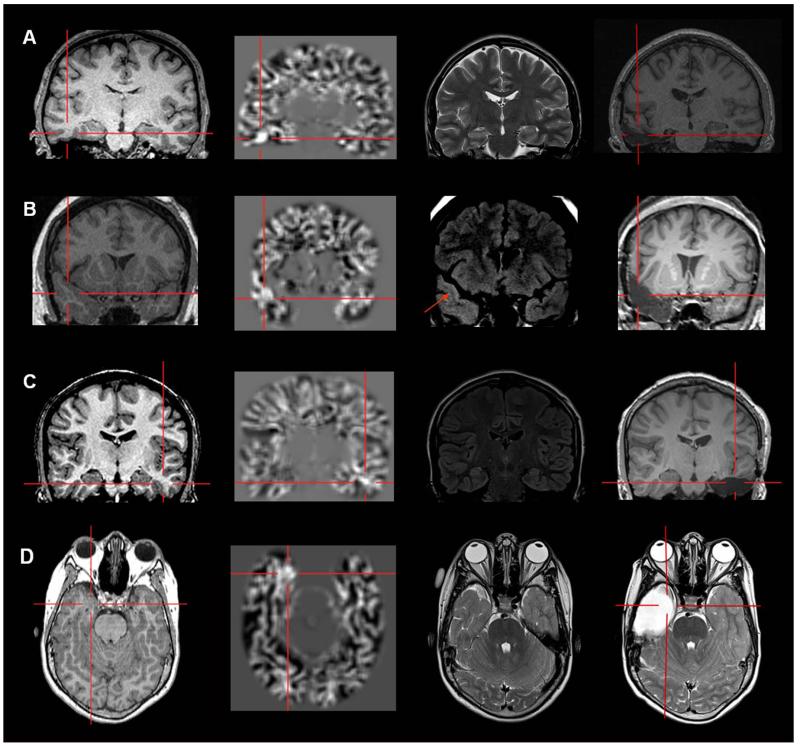

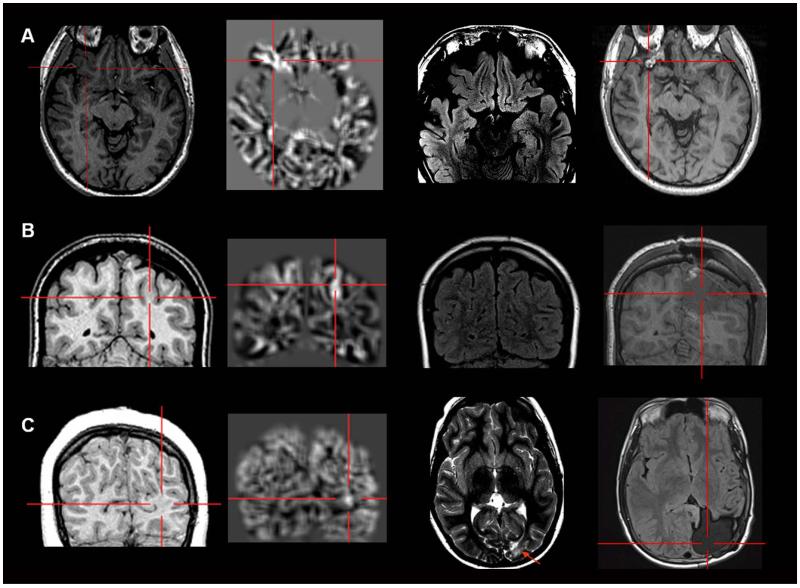

Figure 3.

Examples of four patients with MAP+ region in the temporal lobe. Panels A, B and C belong to the “Strictly Nonlesional” subgroup, and Panel D belongs to the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup. All three cases demonstrate complete resection of the MAP+ region, and all patients remained seizure-free at 12 months. Pathology: A, B, C: FCD type I; D: FCD type IIIa.

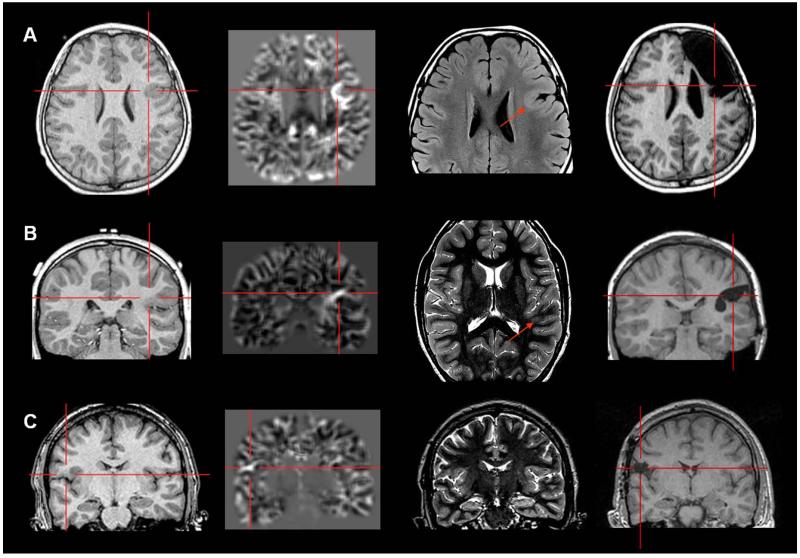

Figure 4.

Examples of three patients with MAP+ region in the operculum (A and C: frontal operculum; B: parietal operculum). Panel A belongs to the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup; B and C belong to the “Strictly Nonlesional” subgroup. All three cases demonstrate complete resection of the MAP+ region, and all patients remained seizure-free at 12 months. Pathology: A, B: FCD type I; C: FCD type II.

Figure 5.

Examples of patients with MAP+ region in the orbito-frontal region (A), parietal lobe (B) and occipital lobe (C). Panel A and B belong to the “Strictly Nonlesional” subgroup; panel C belong to the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup. All three cases demonstrate complete resection of the MAP+ region, and all patients remained seizure-free at 12 months. Pathology: A, C: FCD type I; B: FCD type I + nodular heterotopia. In Panel C, the MAP+ region is best shown on the coronal slices; the T2-weighted image and post-operative MRI were only available in axial slices, and therefore only axial slices are presented here.

The same trend holds true for both the “Subtly Lesional” and the “Strictly Nonlesional” subgroups. Sensitivity and specificity were 0.97 (95% CI: 0.83, 0.99) and 0.67 (95% CI: 0.22, 0.96) in the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup. Similarly, sensitivity and specificity were 0.8 (95% CI: 0.56, 0.94) and 0.67 (95% CI: 0.3, 0.93) in the “Strictly Nonlesional” subgroup. Detailed data for subgroup calculation can be found in Table 2.

We examined the seizure outcome trend in relationship to MAP status using the Cochran-Armitage test, based on the hypothesis that the probability of seizure-freedom would be highest in the MAP+ and fully resected subgroup, followed by the MAP− subgroup, and the lowest in the MAP+ but not/partially resected subgroup. This trend was significant in the overall group (p<0.001), and both the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup (p<0.001) and the “Strictly Nonlesional” subgroup (p=0.006).

In the 65 MAP+ patients, 23 were felt to have MRI changes that were evident on retrospective examination guided by MAP findings, whereas the majority (42) did not have evident MRI changes on retrospective review. Both subgroups show the same trend as the overall MAP+ group, i.e., the resection of MAP+ region is positively associated with a seizure-free outcome, irrespective of subgroup allocation. Details can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of MAP+ abnormalities that had evident or subtle MRI changes during retrospective qualitative review by the neuroradiologist. Abnormalities in each category were compared with resection and seizure outcome at 12 months.

| MAP+ Patients | Total | Seizure-free (12 m) |

Not seizure-free (12 m) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N=65) | ||||

| Subgroup with evident MRI changes (N=23) | ||||

| Resected | 16 | 14 | 2 | 0.01 d |

| Not resected | 7 | 2 | 5 | |

| Subgroup without evident MRI changes (N=42) | ||||

| Resected | 34 | 31 | 3 | 0.003 d |

| Not resected | 8 | 3 | 5 | |

p-values:

=Fisher’s Exact test.

All MAP+ regions were detected by visual analysis of the junction file. Fifteen patients exhibited associated changes on the MAP extension file in the same or adjacent region as the junction file; 9 patients had associated changes on the corresponding thickness file. Among the 96 patients who had 1.5T MRI, 41 (43%) were MAP+; in the 54 patients who had 3T MRI, 24 (44%) were MAP+. There was no significant difference in the MAP detection rate between the 2 MRI field strengths (p=0.83).

Correlation of MAP and Outcome

Regardless of whether the MAP+ region was resected or not, MAP+ patients tend to have better outcome than MAP− patients in the overall group (p=0.022), but these differences were not significant in either the “Subtly Lesional” or the “Strictly Nonlesional” subgroup. Details are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Detailed data used for the calculation of the association between MAP and outcome.

| Groups | Total | Seizure-free (12 m) |

Not seizure-free (12 m) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N=150) | ||||

| MAP+ | 65 | 50 | 15 | 0.022 c |

| MAP− | 85 | 44 | 41 |

p-values:

=Pearson’s chi-square test,

MAP and Pathology

Surgical specimens in the 50 patients who had the MAP+ regions fully resected exhibited FCD in 28 (56%, type II in 7, type I in 18, and type III in 3).37 Four patients had HS, one patient had remote infarct, and another had atrophy and microglia cell proliferation. Specimens were pathologically negative in 15 patients (gliosis, hamartia, or normal). No specimen was sent to pathology examination in one patient.

Validity of the Visually Identified Subtle Findings

In the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup, 52(75%) of the 69 patients who had the visually identified subtle finding completely removed became seizure-free; whereas 7(64%) of the 11 patients who did not have the visually identified finding resected had recurring seizures. Resection of a subtle MRI abnormality that was visually identified in PMC was indeed associated with seizure-free outcome (p=0.014). However, in subgroup analysis, we found that this association was significant only in those patients who were MAP+ (p=0.01), but was no longer significant in the MAP− subgroup (p=0.36). Details are in Table 5.

Table 5.

Detailed data used for the subgroup analysis to evaluate the validity of the visually identified subtle findings during focused re-review at the patient management conference. The p-values shown were based on Fisher’s exact test between the fully resected group and the not/partially resected groups combined.

| “Subtly Lesional” Subgroup | Total | Seizure-free (12 m) |

Not seizure-free (12 m) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N=80) | ||||

| Visually identified subtle finding fully resected |

69 | 52 | 17 | 0.014 d |

| Visually identified subtle finding not/partially resected |

11 | 4 | 7 | |

| MAP+ Subgroup (n=39) | ||||

| Visually identified subtle finding fully resected |

33 | 29 | 4 | 0.01 d |

| Visually identified subtle finding not/partially resected |

6 | 2 | 4 | |

| MAP− Subgroup (n=41) | ||||

| Visually identified subtle finding fully resected |

36 | 23 | 13 | 0.36 d |

| Visually identified subtle finding not/partially resected |

5 | 2 | 3 |

=Fisher’s exact test.

Among the 80 patients in the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup, 59 patients were thought to have subtle neocortical (including temporal) abnormalities as discussed in PMC; MAP was positive in 34 (58%). In the 25 MAP− patients of the neocortical group, 8 patients had findings that could be visually identified only on T2-weighted sequences which were not processed by MAP; the remaining 17 patients (only 9 of whom became seizure-free) had visually identifiable findings on both T1- and T2-weighted sequences, which MAP was not able to confirm.

Twenty-one patients had hippocampal abnormalities identified in PMC (mostly atrophy, rarely signal hyperintensity); MAP was positive in 5 (30%). Two of the MAP+ patients in the hippocampal group were confirmed to have both HS and FCD in the ipsilateral temporal lobe (i.e., FCD type IIIa37). Details can be found in Table 6.

Table 6.

Detailed breakdown of patients in the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup in terms of whether MAP was positive or negative. The location of the visually noted subtle findings during focused re-review at the patient management conference was categorized in to three subgroups: neocortical (including temporal), unilateral hippocampal and bilateral hippocampal. FCD=focal cortical dysplasia. HS=hippocampal sclerosis.

| “Subtly Lesional” Subgroup (N=80) | Total | MAP+ | MAP− |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neocortical | 59 | 34 | 25 |

| Unilateral Hippocampal | 17 | 5 (1 HS, 2 FCD+HS) |

12 (3 HS, 4 FCD) |

| Bilateral Hippocampal | 4 | 0 | 4 (1 HS, 2 FCD) |

Multiple MAP+ Regions

A total of 11 patients had multiple MAP+ regions. Three were in the same lobe as the area of resection; 3 were in a different lobe on the ipsilateral side of the resection; and 5 were contralateral to the resection. In all of the 11 patients, only one of the two MAP+ regions was resected. All 6 patients (100%) with an ipsilateral unresected MAP+ region had recurring seizures; in contrast, only one (20%) of the 5 patients with an MAP+ region contralateral to the resection had recurring seizures. Despite the small numbers, there is a significant correlation (p=0.015, Fisher’s exact test) between adverse seizure outcome and side of the unresected MAP+ region, i.e., ipsilateral or contralateral to resection.

False Positive in Normal Controls

In the 52 normal controls, only one was judged to be MAP+, resulting in a false positive rate of 2% (1/52). The remaining 13 regions were judged to be normal (blood vessels in 2, normal myelination in 3, developmental venous anomaly in one, and 7 regions were labeled as non-significant normal variants).

Candidate MAP+ Areas Accepted and Rejected

In the overall cohort, 65% (98/150) had at least one candidate MAP+ area identified and reviewed; 27% (40/150) of patients had at least one candidate MAP+ area rejected. In 9 patients, such rejected regions got fully resected, and 8 patients became seizure free. Of the remaining 31 patients, such rejected regions were not resected or partially resected, and 15 patients became seizure free. This observation suggests that the rejected candidate MAP+ findings may sometimes be significant, although not statistically significant (p=0.054).

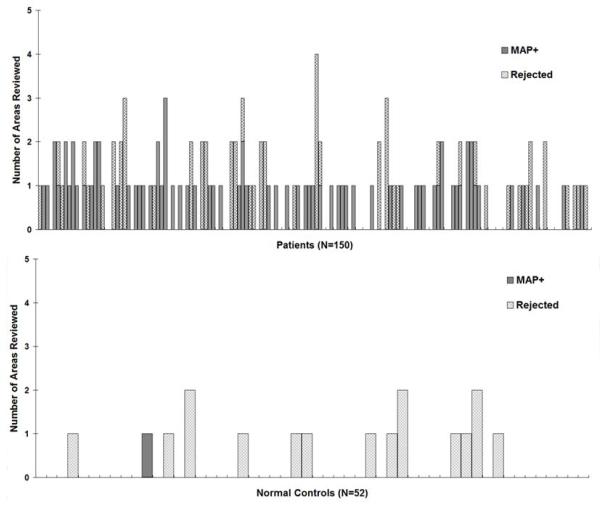

In the normal controls, 27% (14/52) had at least one candidate MAP+ area reviewed. This is a significantly lower percentage compared to the patient cohort (65%, p<0.0001). The candidate MAP+ areas were judged to be significant in only one single normal subject (2%), whereas the remaining 25% (13/52) were rejected. The percentage of areas rejected did not differ between patients (27%) and normal controls (p=0.8). Detailed information is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Detailed information on MAP reviewing, including the number of candidate MAP+ areas reviewed and the number of areas rejected by the neuroradiologist. In both panels, each bar represents one patient/subject. The height of the bars indicates the total number of candidate MAP+ areas reviewed in each patient/subject. Within each bar, the gridded pattern shows the areas reviewed but judged to be non-significant by the neuro-radiologist (and therefore rejected); the solid pattern shows the areas confirmed to be MAP+. For patients/subjects whose MAP did not have any regions with z>4 on the junction file, the height of the bar is set to 0.

Discussion

Our retrospective study of a large surgical series with long postoperative seizure follow up reveals the usefulness of MAP in identifying subtle and potentially epileptogenic lesions (FCD in particular). Our findings suggest that MAP can be used as a practical and valuable tool to optimize the yield of the noninvasive presurgical evaluation in “nonlesional” epilepsies. An interesting finding from this study is the fact that seizure outcomes did not differ between patients who did or did not undergo intracranial monitoring. This observation highlights the importance of in-depth localization using noninvasive tools to provide a more global view of epileptic abnormalities, given the invasive nature and inherently limited sampling of intracranial studies.

In line with previously published reports, our study demonstrates that MAP can be used to augment lesion detection. Huppertz et al. performed a retrospective evaluation of 25 patients with histologically confirmed FCD, in whom MAP detected the epileptogenic abnormality in 4 of the 8 MRI− patients in this series (50%).8 Wagner et al. performed a retrospective study in 91 patients with confirmed type II FCD. The combination of MAP and subsequent conventional visual analysis led to detection of subtle lesions in 11 of the 13 MRI− patients (85%).6 Our series is comprised exclusively of MRI− patients and shows that MAP+ areas were detectable in 65 of the 150 MRI− patients (43%). Differences in detection rates among studies may be explained by nonuniform inclusion criteria in regards to the exact definition of “MRI−”. In addition to MAP, various other MRI processing methods have also been reported to effectively assist lesion detection;14-28, 30, 32 the comparison between MAP and these techniques is beyond the scope of this study. An excellent summary comparing MAP with other MRI post-processing studies can be found elsewhere.6

What does a MAP+ region indicate?

1. A MAP+ finding could transform a case from MRI− to MRI+

The “Strictly Nonlesional” subgroup had a 41% MAP positive rate, i.e., focused re-review of the MRI guided by MAP results turned 41% of these cases from MRI− to MRI+. Some of these lesions were evident when reviewed retrospectively, but escaped detection despite careful review of the same MRI during presurgical evaluation, as they often involved areas of the brain distant to the putative region of interest. Some of these lesions were not as evident, even when reviewed retrospectively, and had subtle signal changes on one single sequence or very few imaging slices; some of them were obscured due to concomitant artifacts. Our subgroup analyses suggest that MAP performs equally in picking up abnormalities with or without evident MRI changes. The 41% overall pickup rate of MAP in our cohort suggests a substantial diagnostic benefit, considering the fact that MAP is only a post-processing method that can be applied to standard MRIs without incurring any additional cost or risk to patients. Indeed, the strategy of performing a focused re-review guided by another noninvasive measure (structural or electrophysiological) has been utilized in the literature and in clinical practice. In a previous study of 40 patients with neocortical epilepsy, positive MSI findings triggered re-review of 29 cases, and in 7 the MEG-guided review led to previously unidentified lesions.39 We had reported a cohort of 25 MRI− patients in whom MAP and MSI conjunctively identified dysplastic abnormalities in 7; those with complete resection of these abnormalities had a significantly higher chance of achieving seizure freedom than those without.11 In addition to magnetic source imaging, EEG source imaging has also been reported to help localize the epileptic focus in MRI− epilepsies.40 Chassoux et al. examined the value of FDG-PET in 23 patients with histologically proven FCD and negative MRI. Both visual and SPM analysis of PET aided detection of FCD which corresponded with invasive EEG and surgical outcome.41 Despite different patient populations, these published studies, along with our current study, suggest that correlation between multiple imaging and neurophysiology methods can be used to further the analysis of available MRI data in patients with strictly normal or near-normal MRI findings.

2. MAP+ patients may have more localized epilepsies

We did not find a significant association between demographics/clinical factors and seizure-free outcome, similar to the nonlesional cohort described in our previous study4 and in line with literature.3, 42, 43 However, in this same cohort, MAP+ patients tend to have better outcome than MAP− patients. This finding raises the possibility that the presence of MAP+ results may be an independent predictor of seizure-free outcome in similar cohorts of MRI− patients. Furthermore, taking into account the fact that MAP did not guide surgical resections in this retrospective study, our results may suggest that “nonlesional” epilepsies are not all the same: MAP+ patients may harbor a more localized epileptogenic zone which could in turn lead to more localizing/concordant results from other noninvasive testing.11, 44, 45 Hence these patients are more likely to become seizure-free following tailored resection of the subtle lesion. Therefore the use of post-processing methods such as MAP may allow us to separate, to some degree, nonlesional patients with a more restricted epileptogenic process from those with a more diffuse process.

3. MAP+ regions should be surgically explored

Complete resection of the MAP+ region correlated positively with seizure-free outcome, indicating that in the appropriate clinical setting, MAP+ areas likely point to potentially epileptogenic lesions and should serve as a legitimate target for further exploration. Sensitivity in the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup is higher as compared to the “Strictly Nonlesional” subgroup, which is not unexpected, given that patients in the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup had visually identifiable MRI abnormalities, and were therefore expected to have more MAP+ findings. We should note that for both subgroups MAP performs equally in terms of specificity. Overall, the finding of MAP+ results may allow for a more focused invasive investigation that could in turn yield a more favorable surgical outcome.

Our data shows that the likelihood of achieving seizure freedom was greatest for those patients with MAP+ regions completely resected (45/50, 90% seizure-free), followed by MAP− patients (44/85, 52% seizure-free). Patients whose MAP+ regions were not/partially resected had the least likelihood to achieve seizure freedom (5/15, 33% seizure-free). These results further support that MAP-identified abnormalities in this patient population may indeed harbor the elusive epileptogenic lesion. This knowledge represents a potentially important additional piece of information to discuss with patients and their families prior to surgery.

Are we over-reading the MRI?

In everyday clinical practice, it is not uncommon that previously unnoted findings are identified when multi-modal data are put together for discussion. This occurred in 80 (53%) of the 150 patients included in our study, i.e. the “Subtly Lesional” subgroup. While many of these findings may indeed point to previously overlooked epileptogenic lesion, others may reflect our “over-reading” of MRI studies, and lead to potentially biased surgical discussion and electrode implantation. Indeed, we found that not all these visually identified findings were significant. Our subgroup analysis suggests that visually identified subtle MRI findings were more likely relevant if they were also MAP+. Therefore MAP may be used not only as a “search tool” for subtle lesions, but also as a “confirmation tool” for questionable abnormalities, to increases or decreases our level of confidence given its quantitative and less subjective nature. It is also conceivable that in addition to MAP, other quantitative post-processing methods could also be used to serve this purpose.

Would targeting the MAP+ regions have resulted in implanting additional electrodes?

We examined the 10 patients who had no/partial resection of the MAP+ regions, and had recurring seizures. Eight out of the 10 patients had ICEEG and in 6 patients the MAP+ regions were not targeted. Therefore, we may postulate, based on the results of this study, that the MAP findings could have made a difference in the design of the implantation scheme, and could have potentially improved the seizure outcomes. We are studying these 10 patients in detail as a parallel study. Proven to be relevant, the unresected MAP+ regions will be taken into account as potential targets of exploration, should another surgical intervention is contemplated.

Faced with multiple abnormalities, which one is significant?

A small percentage (7%) of the patients included in this study had multiple MAP+ regions. This finding is consistent with our previous study11 and literature.21, 26, 46 In the absence of direct electro-clinical correlates, it is difficult to infer on the current or potential epileptic nature of multiple MAP+ regions. Despite the small numbers, our finding may suggest that a second MAP+ region that is located on the side contralateral to the hemisphere implicated by the rest of the noninvasive evidence, is perhaps less likely to be epileptic, as compared to a second MAP+ area within the hemisphere that is implicated by other noninvasive data. This further highlights the importance of interpreting the MAP results with electro-clinical correlation in the management of these patients.

Limitations of MAP

There were 5 patients whose MAP+ regions were fully resected but had recurring seizures. At face value, these areas may be considered as false positives; however, surgical specimen of all 5 patients contained Type I FCD, which is known to be less focal than other FCD subtypes, and associates with less favorable surgical outcome.7, 47, 48 In these patients, MAP may not be able to accurately delineate the full extent and boundaries of the underlying lesion, therefore a tailored resection (limited to the MAP+ region) may not be sufficient in removing the entire epileptic focus. These findings point to a limitation of the MAP method in the detection of some FCD type I lesions.

Additionally, one needs to note that the MAP methodology applied in our study is driven towards neocortical foci but not structural changes within the hippocampi. Given that our study involved a consecutive cohort, we elected to not exclude those MRI− patients who were found to have exclusively hippocampal epilepsy, understanding that for this subgroup it would not be fair to expect MAP to yield positive results in all. Nevertheless, our findings do suggest that MAP might have additional value in identifying FCD coexisting with HS. Note that in our subgroup of patients with hippocampal foci, pathology results did not consistently reveal hippocampal sclerosis (only 7 of 21 patients had HS), which is expected in the face of subtle, mainly atrophic MRI changes.

Future Directions to Enhance Performance of MAP

1. Use of Higher MRI Field Strengths

It is conceivable that the increased contrast-to-noise ratio and spatial resolution of higher-field MRI could increase the detection rate of FCD lesions,49 and thereby improve results of post-processing. Wagner et al. reported that diagnostic yield of MAP was significantly better at 3T as compared to 1.5T, in a cohort of patients with type II FCD.6 This finding was not reproduced in our study. In our MRI− cohort (with mostly type I FCD), the MAP+ rate did not differ significantly between 1.5T and 3T. Differences in patient population in the two studies may account for the discordant observation. Further investigations are needed to assess whether higher-field (3T or 7T) MRI can improve the diagnostic yield of MRI post-processing in epilepsy patients.

2. Adopt a Multi-contrast Framework

The T1-weighted volumetric MRI was used as input to MAP in this study, because it was readily and always available as part of our routine epilepsy MRI protocol. T2-weighted images by themselves can be extremely important to delineate the epileptogenic lesion,50, 51 and MAP can also be performed on T2-weighted images.10 In our study, those subtle FCD lesions, that only (or mainly) exhibit T2 signal changes, were perhaps undetected with the current technique but could be identified with the processing of T2 images. As subtle FCD lesions may only differ slightly from normal cortex,52 a multi-variate framework may be necessary to assess the combined sensitivity of various contrasts.13

3. Develop Advanced Automated Thresholding

MAP is not a magic bullet, wherein an arbitrary z-score equates with a “lesion”. In our study, the percentage of candidate MAP+ areas that were rejected by the neuroradiologist was similar between patients and normal controls. These areas may represent normal variants that exist in both epileptic and healthy brains. The similarity of rejection rates in the two groups suggests that the human component of MAP (albeit subjective) still constitutes an important part of the methodology. Not expectedly, human judgment can sometimes lead to rejecting significant findings, as suggested by those seizure-free patients who happened to have surgery including the rejected areas. Overall, there is a need for an advanced, automated statistical thresholding method that would optimize the sensitivity, specificity and consistency of MAP results.24

4. Interpret in the Context of Electro-clinical Presentation

We adopted a blinded methodology, wherein no clinical information was provided to the MAP reviewers, which does not reflect standard practice in the process of multidisciplinary presurgical evaluation. Sensitivity may increase when clinical information is provided and/or variable thresholds are used.53 Increased sensitivity, however, may be associated with an increase in false-positive results. A balance between sensitivity and specificity may be achieved on a case-by-case basis. When there is an a priori hypothesis based on clinical and EEG data to confine the analysis to a certain brain region, one may opt for maximal sensitivity; whereas when EEG or other functional imaging data do not point to a particular region of interest, it is essential to opt for maximal specificity and decrease false positives. In fact, we would like to emphasize that MAP findings should always be interpreted in the context of the patient’s anatomo-electro-clinical presentation, as MAP method is purely an analysis of structural images and is not a direct measure of epileptogenicity.11

Limitations

Our study is inherently limited by its retrospective nature. Those patients who underwent surgery may have more localizable epilepsy to begin with. Therefore the patients in our study may not adequately represent the overall presurgical MRI− epilepsy population. Additionally, patients from this study were selected from a long time span of 10 years. Patients who were more recently evaluated may have undergone a more rigorous presurgical evaluation (e.g., SISCOM became available at our center in 2006, MSI in 2008, and stereotactic-EEG in 2009), as compared to the earlier patients, causing potential heterogeneity in the cohort.

Patients that are initially labeled as MRI− at other centers may differ from those at our center. Likewise the conversion of an MRI− study to a “Subtly Lesional” one will also depend on the neuroimaging experience of the team. Similarly, the conversion of a candidate MAP+ region to a MAP+ result also depends on the neuroradiologist. These limitations of subjective analysis should be taken into account when generalizing findings from this study across different centers.

Twenty-four patients were out of the ranges of the normal control databases. Fourteen patients were between 7 and 9 years of age; 10 patients were between 10 and 14 years of age. Although MAP+ regions were still uncovered in 18 of these 24 patients, younger brains display significant structural differences (especially in cortical thickness) as compared to mature brains. Acquisition of younger normal controls to construct additional age-specific normal databases is an important next step.

Another limitation of our study is the potential for subtotal sampling of some pathological specimens, which could lead to erroneously underestimating or failing to detect an underlying epileptic pathology. Therefore one cannot exclude that resected MAP+ regions with negative surgical pathology still harbor subtle, solitary FCD lesions in some patients.

Lastly, it should be noted that surgical resection is based on a number of factors that cannot be standardized, and that the seizure onset zone cannot always be resected in its entirety for practical reasons, such as surgical risks or overlap with eloquent cortex.54 Therefore, presurgical imaging localization may not necessarily be incorrect in some patients who continue to have seizures after an incomplete resection.

Conclusions

We present the largest-to-date cohort of MRI− pharmacoresistant epilepsy patients evaluated with MRI post-processing using MAP. Our study shows the diagnostic benefit of MAP in identifying subtle and potentially epileptogenic lesions in MRI− patients. The most common pathological correlate of MAP+ findings is focal cortical dysplasia (commonly non-balloon-cell FCD). Complete resection of MAP+ region correlated positively with seizure-free outcome. As a low-cost and noninvasive approach, MAP shows promise not only as a search tool for subtle abnormalities, but also as a confirmation tool for visually identified but questionable abnormalities. In general, patients with “nonlesional” epilepsies are not considered favorable surgical candidates and may be denied potentially curative epilepsy surgery. Our findings suggest that MAP can serve as a practical and valuable tool to identify some of the more favorable surgical candidates, thereby improve seizure outcomes in “nonlesional” epilepsies.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Epilepsy Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship Grant (Z.I.W.), NIH NINDS grant R01-NS074980 (Z.I.W.), JoshProvides Epilepsy Assistance Foundation (Z.I.W.), UCB (A.V.A.), Pfizer (A.V.A.), the American Epilepsy Society (A.V.A.), Citizens United for Research in Epilepsy (S.E.J., J.A.G.-M.), and the US Department of Defense (I.M.N.). The authors would like to acknowledge Lu Wang and James Bena at Cleveland Clinic Quantitative Health Sciences for statistical assistance. The authors would also like to acknowledge Dr H.-J. Huppertz for his gracious support. This paper is dedicated to father of Dr. Z.Irene Wang, Mr. Gang Wang, who recently passed away after a five-year battle with lung cancer.

Abbreviations

- FLAIR

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- FCD

focal cortical dysplasia

- MAP

morphometric analysis program

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PFE

pharmacoresistant focal epilepsy

- ICEEG

intracranial EEG

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest

A.V.A.: editorial board, Epileptic Disorders. I.M.N.: speaker’s bureau, UCB.

References

- 1.Bien CG. Characteristics and surgical outcomes of patients with refractory magnetic resonance imaging-negative epilepsies. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1491–9. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeha LE. Surgical outcome and prognostic factors of frontal lobe epilepsy surgery. Brain. 2007;130:574–84. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tellez-Zenteno JF, Hernandez Ronquillo L, Moien-Afshari F, Wiebe S. Surgical outcomes in lesional and non-lesional epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsy Res. 2010 May;89(2-3):310–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang ZI, Alexopoulos AV, Jones SE, Jaisani Z, Najm IM, Prayson RA. The pathology of magnetic-resonance-imaging-negative epilepsy. Mod Pathol. 2013 Aug;26(8):1051–8. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hauptman JS, Mathern GW. Surgical treatment of epilepsy associated with cortical dysplasia: 2012 update. Epilepsia. 2012 Sep;53(Suppl 4):98–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner J, Weber B, Urbach H, Elger C, Huppertz H. Morphometric MRI analysis improves detection of focal cortical dysplasia type II. Brain. 2011;134(10):2844–54. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krsek P, Maton B, Korman B, et al. Different features of histopathological subtypes of pediatric focal cortical dysplasia. Ann Neurol. 2008 Jun;63(6):758–69. doi: 10.1002/ana.21398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huppertz HJ, Grimm C, Fauser S, et al. Enhanced visualization of blurred gray-white matter junctions in focal cortical dysplasia by voxel-based 3D MRI analysis. Epilepsy Res. 2005 Oct-Nov;67(1-2):35–50. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huppertz HJ, Wellmer J, Staack AM, Altenmuller DM, Urbach H, Kroll J. Voxel-based 3D MRI analysis helps to detect subtle forms of subcortical band heterotopia. Epilepsia. 2008 May;49(5):772–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.House PM, Lanz M, Holst B, Martens T, Stodieck S, Huppertz HJ. Comparison of morphometric analysis based on T1- and T2-weighted MRI data for visualization of focal cortical dysplasia. Epilepsy Res. 2013 Oct;106(3):403–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang ZI, Alexopoulos AV, Jones SE, et al. Linking MRI postprocessing with magnetic source imaging in MRI-negative epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2014 May;75(5):759–70. doi: 10.1002/ana.24169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang ZI, Ristic AJ, Wong CH, et al. Neuroimaging characteristics of MRI-negative orbitofrontal epilepsy with focus on voxel-based morphometric MRI postprocessing. Epilepsia. 2013 Dec;54(12):2195–203. doi: 10.1111/epi.12390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernasconi A, Bernasconi N, Bernhardt BC, Schrader D. Advances in MRI for ‘cryptogenic’ epilepsies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011 Feb;7(2):99–108. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sisodiya SM, Free SL, Stevens JM, Fish DR, Shorvon SD. Widespread cerebral structural changes in patients with cortical dysgenesis and epilepsy. Brain. 1995 Aug;118(Pt 4):1039–50. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.4.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonilha L, Montenegro MA, Rorden C, et al. Voxel-based morphometry reveals excess gray matter concentration in patients with focal cortical dysplasia. Epilepsia. 2006 May;47(5):908–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruggemann JM, Wilke M, Som SS, Bye AM, Bleasel A, Lawson JA. Voxel-based morphometry in the detection of dysplasia and neoplasia in childhood epilepsy: combined grey/white matter analysis augments detection. Epilepsy Res. 2007 Dec;77(2-3):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merschhemke M, Mitchell TN, Free SL, et al. Quantitative MRI detects abnormalities in relatives of patients with epilepsy and malformations of cortical development. Neuroimage. 2003 Mar;18(3):642–9. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woermann FG, Free SL, Koepp MJ, Ashburner J, Duncan JS. Voxel-by-voxel comparison of automatically segmented cerebral gray matter--A rater-independent comparison of structural MRI in patients with epilepsy. Neuroimage. 1999 Oct;10(4):373–84. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sisodiya SM, Free SL, Fish DR, Shorvon SD. Increasing the yield from volumetric MRI in patients with epilepsy. Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;13(8):1147–52. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(95)02025-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colliot O, Bernasconi N, Khalili N, Antel SB, Naessens V, Bernasconi A. Individual voxel-based analysis of gray matter in focal cortical dysplasia. Neuroimage. 2006 Jan 1;29(1):162–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antel SB. Automated detection of focal cortical dysplasia lesions using computational models of their MRI characteristics and texture analysis. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1748–59. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antel SB, Bernasconi A, Bernasconi N, et al. Computational models of MRI characteristics of focal cortical dysplasia improve lesion detection. Neuroimage. 2002 Dec;17(4):1755–60. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernasconi A, Antel SB, Collins DL, et al. Texture analysis and morphological processing of magnetic resonance imaging assist detection of focal cortical dysplasia in extra-temporal partial epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2001 Jun;49(6):770–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong SJ, Kim H, Schrader D, Bernasconi N, Bernhardt BC, Bernasconi A. Automated detection of cortical dysplasia type II in MRI-negative epilepsy. Neurology. 2014 Jul 1;83(1):48–55. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rugg-Gunn FJ, Boulby PA, Symms MR, Barker GJ, Duncan JS. Whole-brain T2 mapping demonstrates occult abnormalities in focal epilepsy. Neurology. 2005 Jan 25;64(2):318–25. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149642.93493.F4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salmenpera TM, Symms MR, Rugg-Gunn FJ, et al. Evaluation of quantitative magnetic resonance imaging contrasts in MRI-negative refractory focal epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007 Feb;48(2):229–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Focke NK, Symms MR, Burdett JL, Duncan JS. Voxel-based analysis of whole brain FLAIR at 3T detects focal cortical dysplasia. Epilepsia. 2008 May;49(5):786–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riney CJ, Chong WK, Clark CA, Cross JH. Voxel based morphometry of FLAIR MRI in children with intractable focal epilepsy: implications for surgical intervention. Eur J Radiol. 2012 Jun;81(6):1299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bastos AC. Curvilinear reconstruction of 3D magnetic resonance imaging in patients with partial epilepsy: a pilot study. Magn Res Imaging. 1995;13:1107–12. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(95)02019-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bastos AC. Diagnosis of subtle focal dysplastic lesions: curvilinear reformatting from three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:88–94. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199907)46:1<88::aid-ana13>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huppertz HJ, Kassubek J, Altenmuller DM, Breyer T, Fauser S. Automatic curvilinear reformatting of three-dimensional MRI data of the cerebral cortex. Neuroimage. 2008;39:80–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Besson P, Andermann F, Dubeau F, Bernasconi A. Small focal cortical dysplasia lesions are located at the bottom of a deep sulcus. Brain. 2008;131:3246–55. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doelken MT, Mennecke A, Huppertz HJ, et al. Multimodality approach in cryptogenic epilepsy with focus on morphometric 3T MRI. J Neuroradiol. 2012 May;39(2):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson GD, Badawy RA. Selecting patients for epilepsy surgery: identifying a structural lesion. Epilepsy Behav. 2011 Feb;20(2):182–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wellmer J, Parpaley Y, von Lehe M, Huppertz HJ. Integrating magnetic resonance imaging postprocessing results into neuronavigation for electrode implantation and resection of subtle focal cortical dysplasia in previously cryptogenic epilepsy. Neurosurgery. 2010 Jan;66(1):187–94. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000359329.92781.B7. discussion 94-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang ZI, Jones SE, Ristic AJ, et al. Voxel-based morphometric MRI post-processing in MRI-negative focal cortical dysplasia followed by simultaneously recorded MEG and stereo-EEG. Epilepsy Res. 2012 Jun;100(1-2):188–93. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blümcke I, Thom M, Aronica E, et al. The clinicopathologic spectrum of focal cortical dysplasias: a consensus classification proposed by an ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Diagnostic Methods Commission. Epilepsia. 2011 Jan;52(1):158–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engel JJ, Van Ness NP, Rasmussen TB, Ojemann LM. Outcome with respect to epileptic seizures. In: Engel JJ, editor. Surgical treatment of the epilepsies. 2nd ed. Raven Press; New York, NY, USA: 1993. pp. 609–21. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Funke ME, Moore K, Orrison WW, Jr., Lewine JD. The role of magnetoencephalography in “nonlesional” epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2011 Jul;52(Suppl 4):10–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brodbeck V, Spinelli L, Lascano AM, et al. Electrical source imaging for presurgical focus localization in epilepsy patients with normal MRI. Epilepsia. 2010 Apr;51(4):583–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chassoux F, Rodrigo S, Semah F, et al. FDG-PET improves surgical outcome in negative MRI Taylor-type focal cortical dysplasias. Neurology. 2010 Dec 14;75(24):2168–75. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820203a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.See SJ, Jehi LE, Vadera S, Bulacio J, Najm I, Bingaman W. Surgical outcomes in patients with extratemporal epilepsy and subtle or normal magnetic resonance imaging findings. Neurosurgery. 2013 Jul;73(1):68–77. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000429839.76460.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ansari SF, Tubbs RS, Terry CL, Cohen-Gadol AA. Surgery for extratemporal nonlesional epilepsy in adults: an outcome meta-analysis. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010 Aug;152(8):1299–305. doi: 10.1007/s00701-010-0697-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schneider F, Wang ZI, Alexopoulos AV, et al. Magnetic source imaging and ictal SPECT in MRI-negative neocortical epilepsies: Additional value and comparison with intracranial EEG. Epilepsia. 2013 Oct 25;54(2):359–69. doi: 10.1111/epi.12004. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider F, Alexopoulos AV, Wang Z, et al. Magnetic source imaging in non-lesional neocortical epilepsy: additional value and comparison with ICEEG. Epilepsy Behav. 2012 Jun;24(2):234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fauser S, Sisodiya SM, Martinian L, et al. Multi-focal occurrence of cortical dysplasia in epilepsy patients. Brain. 2009 Aug;132(Pt 8):2079–90. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krsek P, Pieper T, Karlmeier A, et al. Different presurgical characteristics and seizure outcomes in children with focal cortical dysplasia type I or II. Epilepsia. 2009 Jan;50(1):125–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Widdess-Walsh P, Diehl B, Najm I. Neuroimaging of focal cortical dysplasia. J Neuroimaging. 2006;16(3):185–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2006.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knake S, Triantafyllou C, Wald LL, et al. 3T phased array MRI improves the presurgical evaluation in focal epilepsies: a prospective study. Neurology. 2005 Oct 11;65(7):1026–31. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000179355.04481.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Urbach H. Focal cortical dysplasia of Taylor’s balloon cell type: a clinicopathological entity with characteristic neuroimaging and histopathological features, and favorable postsurgical outcome. Epilepsia. 2002;43:33–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.38201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marusic P, Najm IM, Ying Z, et al. Focal cortical dysplasias in eloquent cortex: functional characteristics and correlation with MRI and histopathologic changes. Epilepsia. 2002 Jan;43(1):27–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Colliot O, Antel SB, Naessens VB, Bernasconi N, Bernasconi A. In vivo profiling of focal cortical dysplasia on high-resolution MRI with computational models. Epilepsia. 2006;47:134–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Newey CR, Wong C, Wang ZI, Chen X, Wu G, Alexopoulos AV. Optimizing SPECT SISCOM analysis to localize seizure-onset zone by using varying z scores. Epilepsia. 2013 May;54(5):793–800. doi: 10.1111/epi.12139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gaillard WD, Cross JH, Duncan JS, Stefan H, Theodore WH. Epilepsy imaging study guideline criteria: commentary on diagnostic testing study guidelines and practice parameters. Epilepsia. 2011 Sep;52(9):1750–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]